Ultimate Resource Covering The Private Equity And Credit Industry

Private-Equity Giants Settle For Bite-Size Deals. Ultimate Resource Covering The Private Equity And Credit Industry

Related:

The Middle East Becomes The World’s ATM

Saudi Arabia Is Dangling Billions For Research On Aging. Scientists Are Lining Up To Take It

Flight To Money Funds Is Adding To The Strains On Banks

Updated: 6-27-2023

With debt no longer cheap and abundant, Blackstone, KKR and other buyout firms look to smaller deals to build up companies they already own.

Megadeals are out. Little deals are in.

Blackstone and other buyout giants are using their record war chests to snap up smaller companies in deals that typically are easier to accomplish in an era of soaring borrowing costs and economic uncertainty.

Volatile markets and a cloudy economic outlook have made it harder for buyers and sellers to agree on the worth of a business.

More expensive debt and a dearth of bank financing is also making large buyouts more challenging, bankers and private-equity deal makers say.

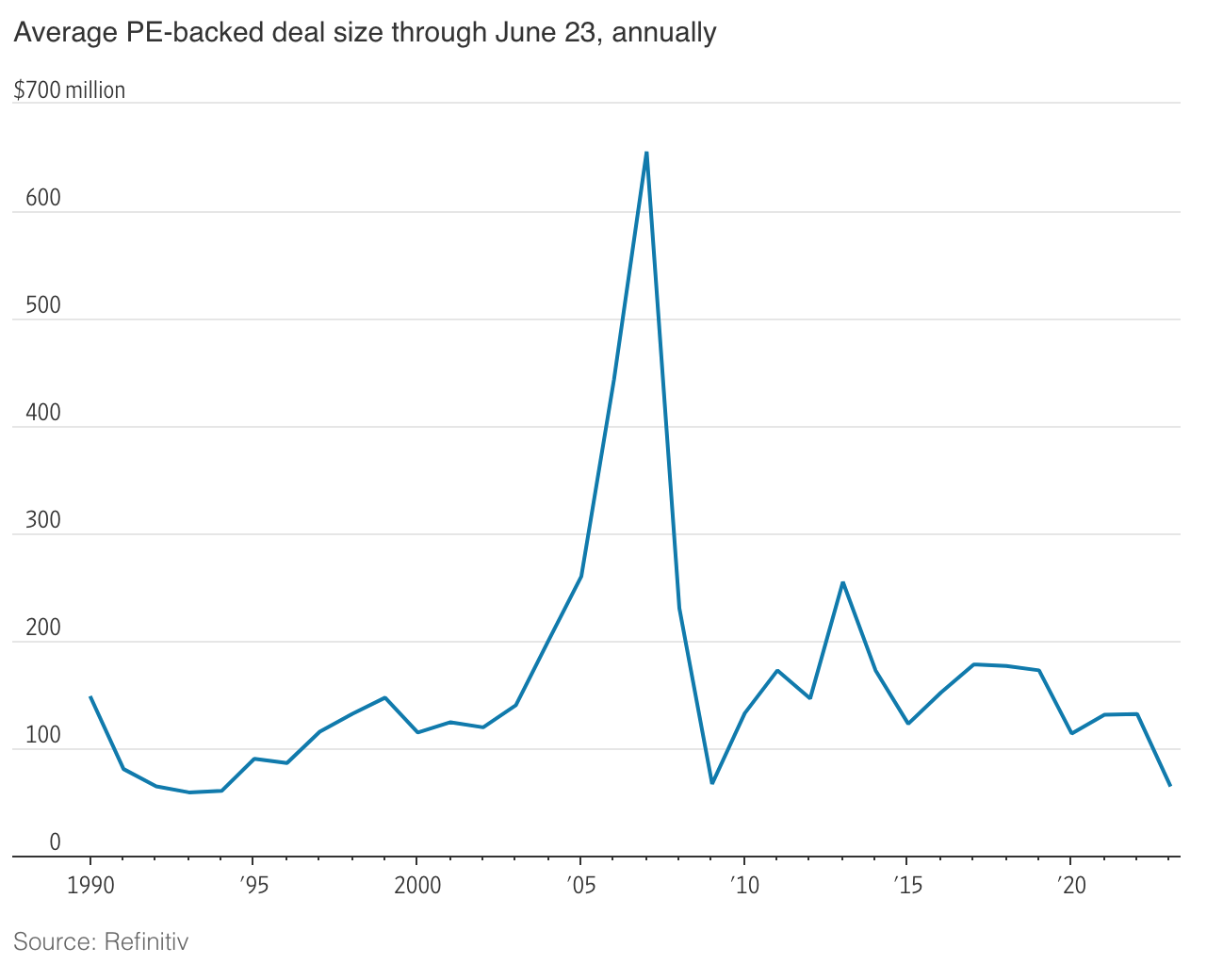

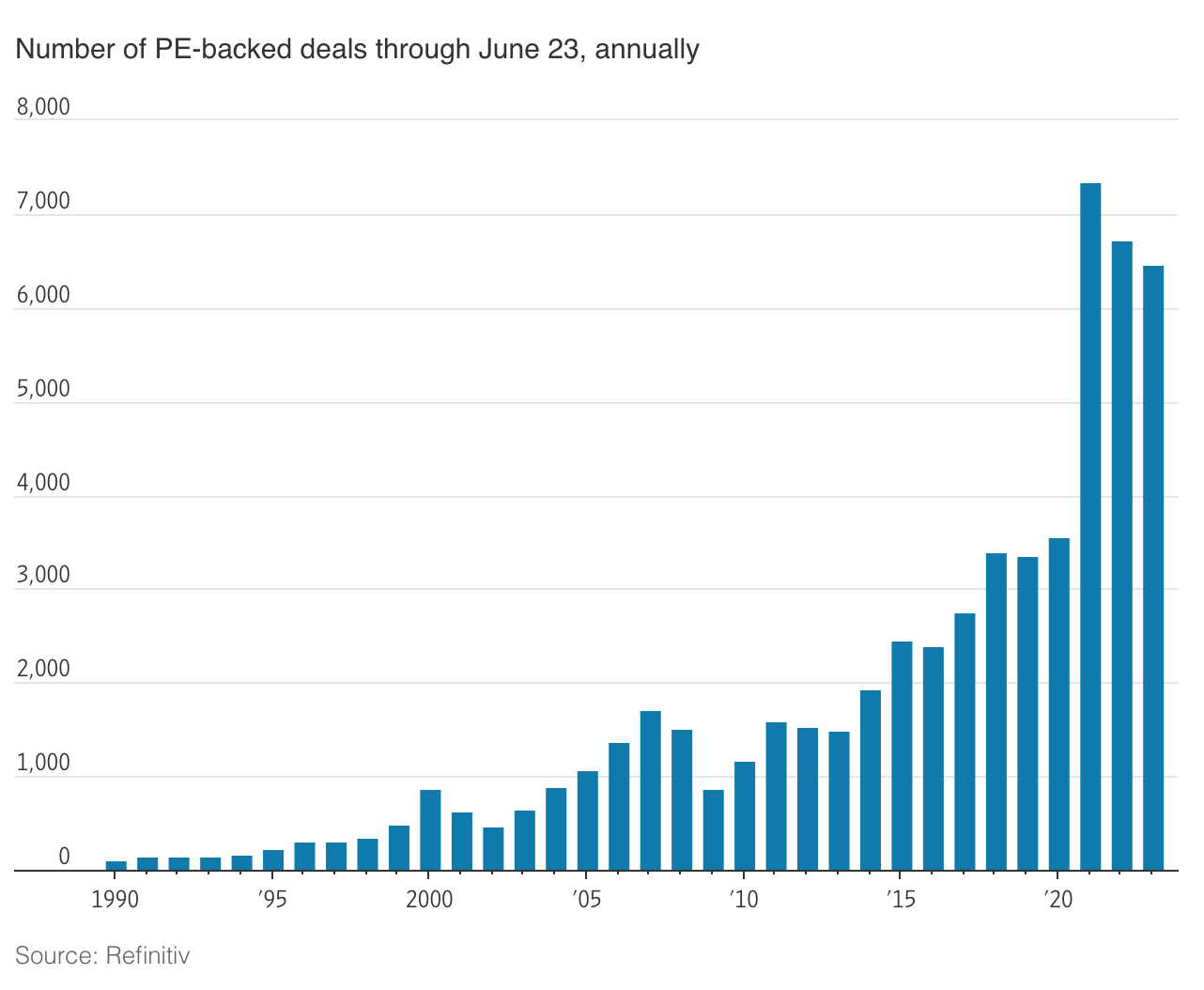

So far this year, PE-backed deals have an average value of $65.9 million, the smallest for the comparable period since the global financial crisis, according to Refinitiv, a data provider.

Smaller takeovers and add-on deals are en vogue, industry participants say, because they often require no debt and allow firms to keep investing despite the tougher backdrop.

An add-on deal is one where a PE firm or other buyer acquires a business and integrates it into a company already in its portfolio.

As of Friday, the overall value of private-equity-backed deals is down over 50% in 2023 versus the prior period, at a three-year low of about $256.7 billion, according to Refinitiv.

But the number of transactions has fallen 4% to 6,458. That is the third-highest year-to-date tally in data going back more than 30 years, showing the resurgence of smaller deals.

For Blackstone, which is known for larger deals such as its $4.6 billion purchase of events-software company Cvent Holding, the shift means buying smaller companies that it can combine with those that it already owns, said Eli Nagler, a deal maker in the firm’s buyout group.

The combined company can eliminate overlapping operations and boost revenue to achieve a higher valuation in a future sale or initial public offering.

Blackstone can take advantage of portfolio companies that have existing debt facilities locked in at lower rates than are currently available.

By drawing down those facilities to finance a deal, Blackstone and the portfolio company can cut acquisition costs, Nagler said.

Companies backed by Blackstone that have recently struck add-on deals include K-12 education-technology provider Renaissance, advertising automation specialist Simpli.fi, and environmental, social and governance software provider Sphera. Values weren’t available.

Ares Management, which finances deals for PE firms, has also seen this trend play out. “For financing commitments out of our U.S. direct-lending business, we saw a smaller average transaction size in the first quarter of 2023 versus the same period in 2022,” said Kipp deVeer, the head of Ares’s credit group.

Updated: 12-18-2019

Apollo And Blackstone Are Stealing Wall Street’s Loans Business

* Growth Of Private Credit Comes At Expense Of Leveraged Lending

* Apollo Sees $200 Billion Of Debt Going Private Over Five Years

On the surface it was a classic leveraged takeover — $1.8 billion of debt to fund the acquisition of Gannett Co. And just like hundreds before it, front and center was Apollo Global Management. Except this time, the private equity giant wasn’t the borrower. It was the lender.

The deal is part of a major shift occurring in global finance. Direct lenders, including more and more hedge funds and buyout firms, are preparing to dish out billions of dollars at a time to lure borrowers away from the $1.2 trillion leveraged loan market.

It’s the latest push by alternative asset managers into what was once the exclusive territory of the world’s biggest investment banks.

And while Wall Street voluntarily ceded much of its business lending to medium-sized companies in the aftermath of the financial crisis, this time the iron grip it has on arranging the industry’s bigger loans is being pried open, jeopardizing some of its juiciest fees.

“Direct lenders have raised significant capital to allow them to commit to larger deals,” said Randy Schwimmer, head of origination and capital markets at Churchill Asset Management. “It’s an arms race.”

It’s a striking reversal of fortune for syndicated-lending desks that spent the last 10 years luring business away from the high-yield bond market, the original source of buyout financing for big, risky companies.

Even as recently as the beginning of the year, deals in excess of $1 billion were largely seen as the private domain of bulge-bracket banks, which arrange and sell them to institutional investors.

Not Anymore.

Apollo said last month that it’s looking to do deals in the $2 billion range. Rival Blackstone Group Inc. is actively pitching a trio of billion-dollar financings that it intends to hold entirely itself, according to a person with knowledge of the matter.

(The firm declined to comment.) And private-credit standouts including Owl Rock Capital and HPS Investment Partners are also setting their sights on bigger loans.

The August financing of New Media Investment Group Inc.’s acquisition of Gannett came on the heels of a $1.25 billion direct loan

by Goldman Sachs Group Inc.’s private-investment arm — one of the few of its kind under a Wall Street bank — and HPS to fund Ion Investment Group’s purchase of financial data provider Acuris.

And in October, a group of about 10 lenders including Owl Rock banded together to provide a $1.6 billion loan to refinance the debt of insurance brokerage Risk Strategies.

“There are bigger pools of capital” now, said Craig Packer, co-founder of Owl Rock, which controls more than $14 billion. “Our holdings of individual loans are therefore larger than was previously available from smaller lenders.”

Fading Fees

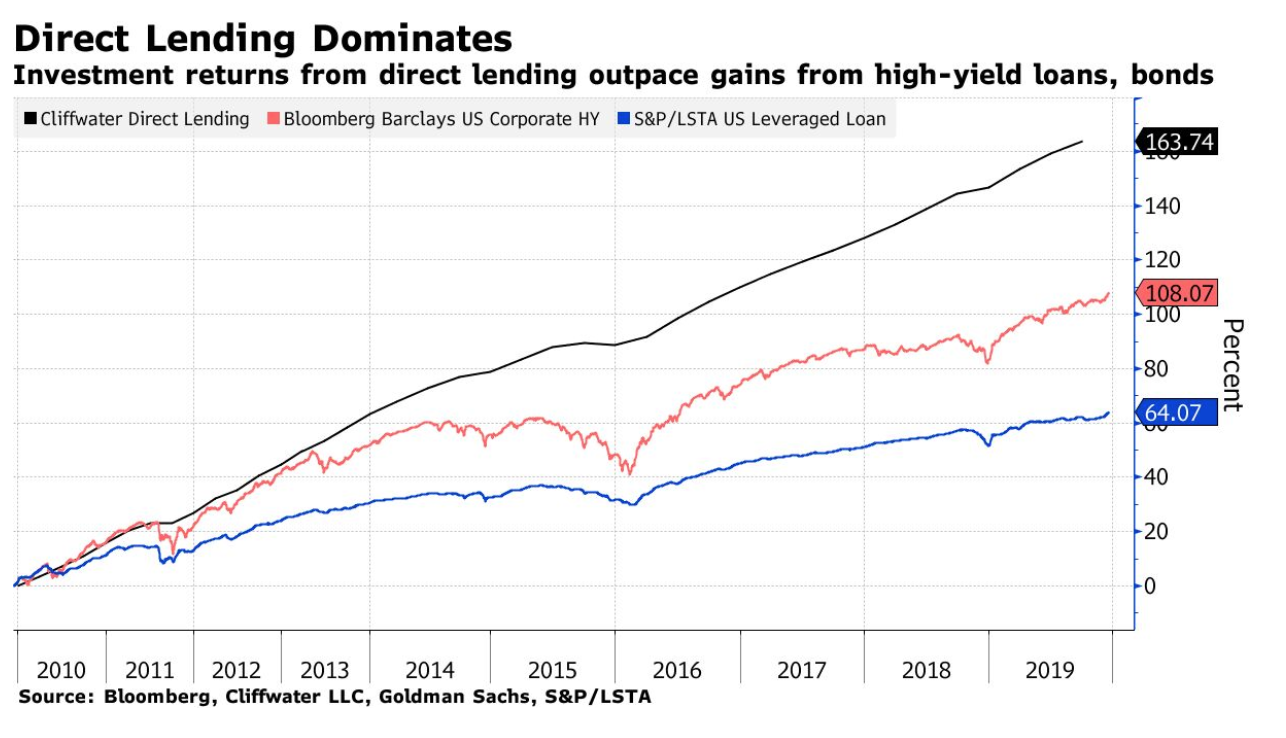

Investors have plowed hundreds of billions of dollars into private debt funds in recent years, lured by premiums that are more than five percentage points higher than competing public debt, according to a Goldman Sachs analysis.

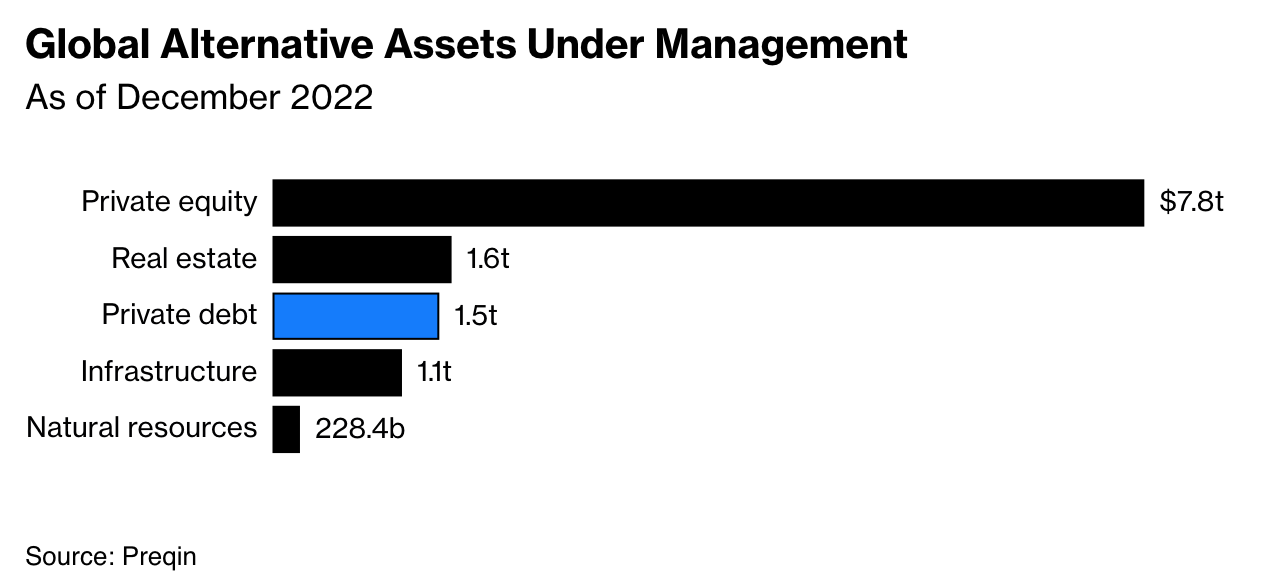

Assets under management now exceed $800 billion, based on the most recent data available from London-based research firm Preqin, including over $250 billion of dry power.

In contrast, leveraged loan growth has begun to stall, with the size of the U.S. market now hovering around $1.2 trillion, up less than 4% from a year earlier.

Partly as a result of direct lenders increasingly allowing borrowers to bypass the syndication process, compensation for arranging leveraged loans has plunged.

Fees are down 29% this year through November, to about $8.5 billion, versus the same period last year, according to Freeman Consulting Services estimates.

The biggest players in the industry say the shift is just getting started.

Apollo predicts as much as 10% of the more than $2.5 trillion high-yield loan and bond market will go private over the next five years, John Zito, co-head of global corporate credit, said at the company’s Nov. 7 Investor Day.

The alternative asset manager sees the privatization of global credit mirroring a similar trend that’s swept equity markets in recent years.

In fact, many say the continued expansion of private equity will only help fuel the growth of direct lending.

“As private equity capacity increases, more deals and larger deals are being done in the private space,” Benoit Durteste, chief executive officer of Intermediate Capital Group, said in a report by the Alternative Credit Council last month.

“This is why we are seeing larger and larger deals in private debt and the limits keep on being pushed.”

Growing execution risk in the leveraged loan market is also prompting buyout firms to increasingly turn to private sources of financing, according to market participants.

Loan buyers have been drawing a line and either bypassing or demanding significant concessions to lend to companies that may struggle in an economic downturn.

On the flip side, private debt transactions can often be arranged in a fraction of the time it takes for a public-market deal, while limited scope for pricing adjustments provides sponsors with greater cost certainty.

Yet efforts to win deals away from investment banks, along with growing competition among direct lenders looking to deploy more than a quarter-trillion dollars of pent up cash, have some worried about weakening lending standards in the industry.

The club loan to Risk Strategies boosted the company’s leverage multiple to seven times a key measure of earnings, as much — if not more — than the issuer would have been able to get away with in the leveraged loan market, according to people with knowledge of the matter.

While the financing includes a maintenance covenant, its terms are loose enough that the company would likely already be struggling to meet interest obligations before the safeguard is triggered, said the people, who asked not to be identified because they aren’t authorized to speak publicly.

“We are worried about how much debt has gone there versus going to the public market, and what that means in a downturn because there’s no liquidity” in private credit, said Elaine Stokes, a portfolio manager at Loomis Sayles & Co. in Boston.

“That could seep into the public markets, if you end up having people becoming forced sellers.”

For others, the growth of direct lending is simply part of the natural evolution of credit markets.

“It’s part of a broader harmonization,” said Jeffrey Ross, chair of Debevoise & Plimpton’s finance group. “The broadly-syndicated loan market for the past 10 years has evolved to look and trade like high-yield bonds. There’s been a similar convergence between the middle-market and bulge-bracket lenders.”

Updated: 6-29-2023

Banks Have To Go Small For Best Returns In $1.5 Trillion Private Credit Industry

* Houlihan Data Shows Loans To Smaller Companies Outperform

* Some Larger Funds Prefer Bigger Deals, Hoping For Resilience

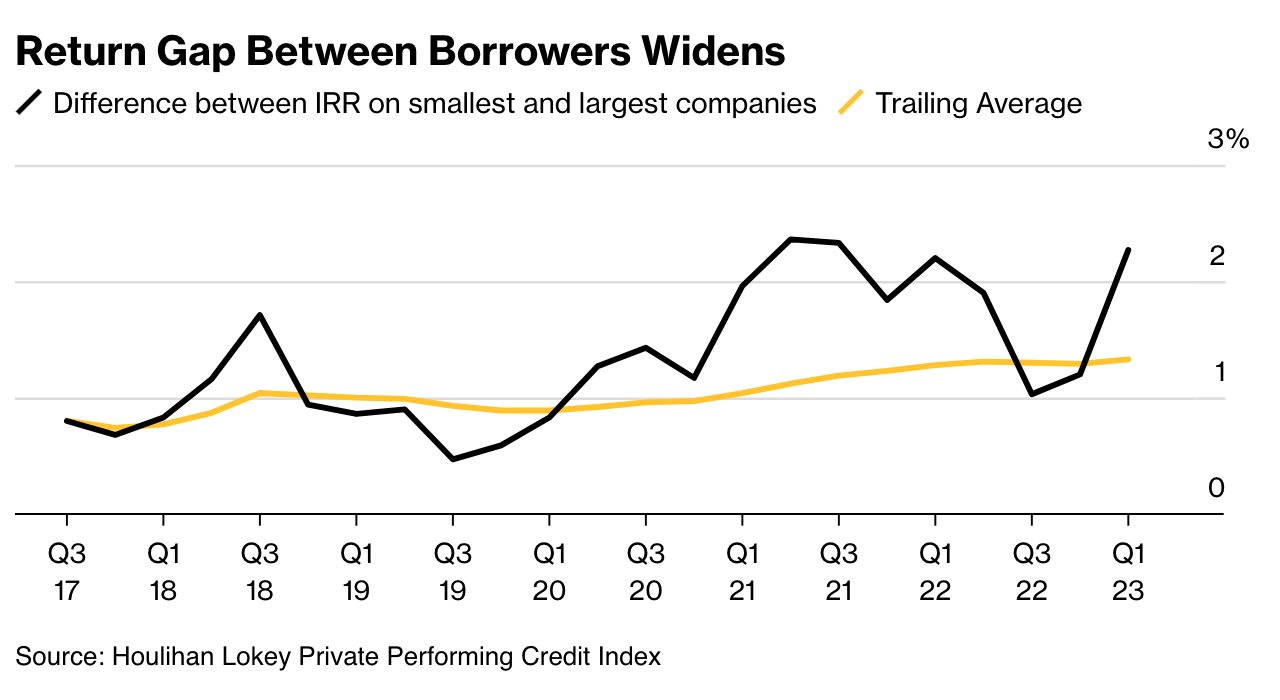

Lenders in the $1.5 trillion private credit industry generate higher returns on loans to smaller companies than on those to bigger businesses, according to data from Houlihan Lokey Inc., pointing to a trade-off faced by managers pursuing larger deals.

The smallest borrowers, as measured by earnings, consistently pay the highest returns, the investment bank found. The firm, which divided companies into quartiles, found that the biggest ones, with Ebitda greater than $50 million, pay the least in data going back to 2017.

The market for the largest direct lending deals has attracted players such as Apollo Global Management and HPS Investment Partners in the last decade.

But funds that invest in mega deals could be sacrificing higher returns, the Houlihan Lokey data shows.

“We have clients asking if they should buy big deals, but our data tells us that large borrowers pay the least,” said David Wagner, a senior adviser at Houlihan Lokey responsible for the firm’s private credit research.

Large direct lenders often tout the resilience of their assets over loans to smaller companies. They typically point to greater product and geographic diversification, as well as improved liquidity and access to debt financing.

Nevertheless, competition is still comparatively thin because few fund managers have the capacity to underwrite mega deals.

Such transactions also give managers the chance to deploy large sums, given the record amount of capital raised in recent years.

Houlihan Lokey’s Private Performing Credit Index shows the dispersion between returns is growing in favor of the smaller bracket. Wagner suggests that small businesses may require more analysis, thus warranting the higher returns.

So, fund managers could face a simple decision between higher returns and more time spent doing due diligence, or the reverse on large-cap deals.

Two dynamics make this decision more difficult. If returns continue to improve on loans to smaller companies, more players may be attracted to that size bracket and the dynamics may shift. Indeed, that process may have begun for some mid-market companies.

Rafael Calvo, chief investment officer of MV Credit, said he had recently seen a mid-market business with pricing similar to a large-cap deal. “We would always need a premium to invest in a mid-cap business,” he said.

The equation changes again if deals from either size bracket suffer disproportionately in a recession. Private credit hasn’t yet endured a prolonged recession and market participants are watching portfolios closely.

While bigger companies will tout their ability to withstand economic shocks better, lender protections have eroded in recent years in many large loans.

In a recent example, EQT AB took Dechra Pharmaceuticals Plc private with the support of a $1.6 billion direct loan deal that lacked any type of maintenance covenant, a contractual protection that allows lenders to monitor the health of businesses on a regular basis.

This trend has gone so far that some mid-market fund managers say smaller businesses are now safer to invest in.

“It’s one of the clear advantages of being a core mid-market player,” Mark Wilton, a managing director at Barings, said on a webinar Tuesday. “We’ve always had robust documentation.”

Deals

* Apollo Global Management led a $225 million private credit debt financing to direct-to-consumer marketer Golden Hippo.

* Tikehau Capital provided a €50 million loan to Milan-based marketing technology company Jakala for the acquisition of Danish firm FFW.

* PacWest Bancorp sold a $3.5 billion asset-backed loan portfolio to Ares Management Corp.

* A group led by Apollo is providing as much as $2 billion to Wolfspeed Inc. to support the semiconductor maker’s expansion in the US.

* Banks and private credit funds are working on debt financings of as much as £1 billion for the potential acquisition of Pharmanovia.

* IQ-EQ is talking to direct lending funds about raising more than €1 billion to refinance its leveraged loans.

Fundraising

* Medalist Partners raised about $600 million to invest in asset-based private credit.

* New Mexico’s sovereign wealth fund approved a bevy of commitments to strategies run by Blackstone Inc., HPS Investment Partners, and Atalaya Capital Management.

* British Columbia Investment Management Corp. deployed almost C$5 billion in private credit investments in the past fiscal year>

* ASK Group plans to raise as much as 10 billion rupees for its debut private credit fund.

* Oaktree Capital Management has raised more than $2.3 billion for its first private credit fund dedicated to life sciences companies.

* Whitehorse Liquidity Partners is seeking to raise $6 billion for a new fund that would help provide liquidity to private equity firms.

Updated: 7-6-2023

More Ways For Investors To Crack The World Of Private Equity

A decade ago, it was almost impossible for private investors to play with the professionals. On this episode of Merryn Talks Money, see how that’s changing.

A decade ago, it was almost impossible for private investors to buy into private equity with the professionals. Most PE funds require huge minimum investments and long-term commitments.

Good managers also don’t come cheap. Now, however, there are more ways for private investors to get into the unlisted sector.

There are funds and trusts that buy individual private companies alongside listed ones, but there are also a few dedicated listed PE trusts.

One of them is Pantheon International. In this week’s Merryn Talks Money, Helen Steers, a partner in Pantheon’s European Investment Team and co-manager of its listed global PE investment trust, Pantheon International Plc, joins host Merryn Somerset Webb to discuss the merits of the sector.

While the sector has a long-term record of outperformance, much of that has come in the unusual low-interest rate environment of the last decade.

Can that continue even as rates normalize? Or are tougher times here to stay for the industry? Steers addresses the questions about discounts, valuations and costs swirling around the sector.

Updated: 7-12-2023

Why Private Equity Is Chasing Plumbers and Lumber Yards

* Founder-Owned Firms Make Up Highest Share Of PE Deals In Years

* Atlanta Plumber Says Daily Investor Pitches Are ‘A Nuisance’

Local plumbers and lumber-yard owners across the US are feeling a bit like tech entrepreneurs of late — juggling multiple offers from private equity-backed firms that increasingly are targeting mom-and-pop businesses.

Wall Street has been buying into fragmented Main Street industries for years, with dental and veterinary practices among the favorite targets.

It’s known as the roll-up strategy – and it’s catching a tailwind right now, and expanding rapidly in household services and building materials.

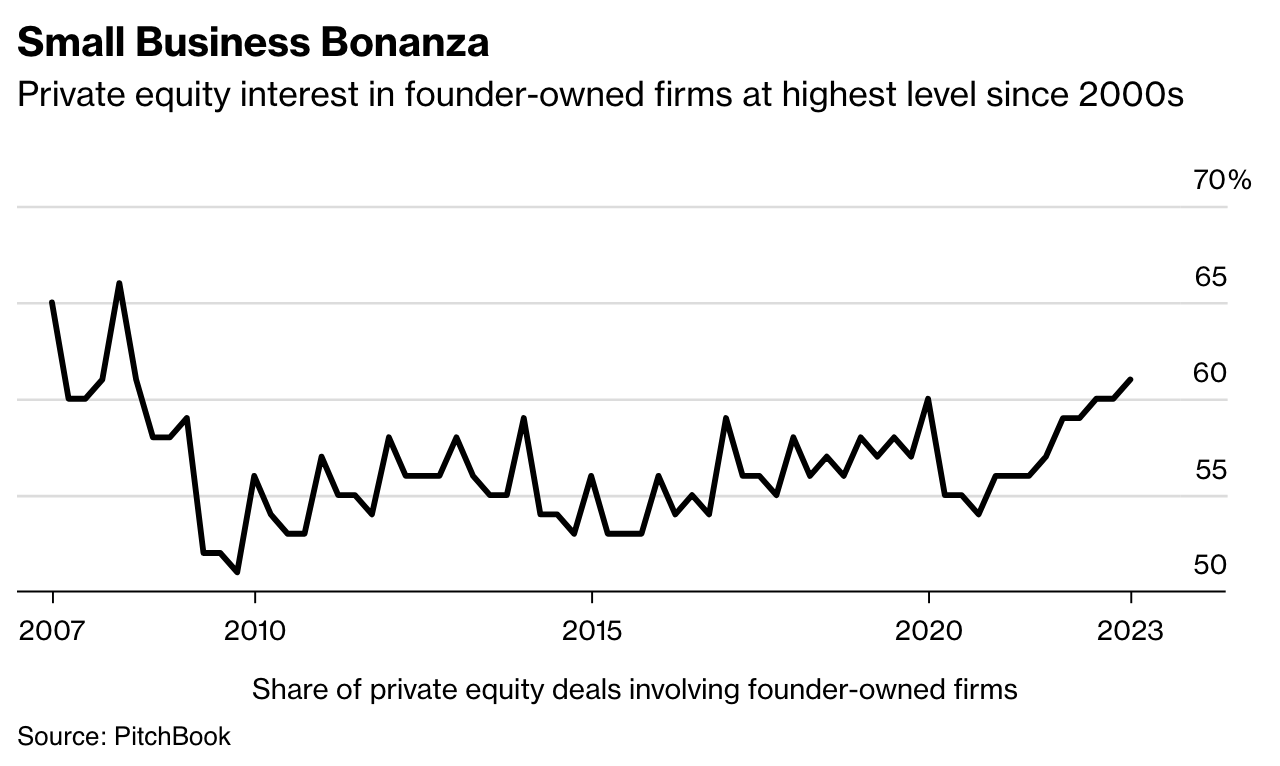

Small firms account for the biggest share of acquisitions by PE funds and their portfolio companies since the late 2000s, according to data from industry analyst PitchBook.

They made up more than 61% of all private equity deals in the first quarter of 2023, compared with an average in the mid-50s over the past decade or so.

“If you acquire enough, you get economies of scale,” says Tim Clarke, PitchBook’s lead private equity analyst. “You just keep rolling rolling, rolling and before you know it you’ve got 10-20% of the market.”

‘They’re A Nuisance’

One reason that approach is popular now, according to Clarke, is that higher interest rates have pushed valuations down across the board.

Owners who might otherwise have considered a sale — whether they’re publicly traded companies, or private equity — are holding onto companies in their portfolios instead.

As a result, would-be buyers are turning toward smaller privately-owned firms, which also tend to be cheaper relative to their earnings.

What’s more, private equity’s enthusiasm for small firms is spreading into industries like plumbing and other trades — which have shown they’re recession-proof, even in the Covid slump, and have room for consolidation because markets are typically divided up among many businesses.

All of this Wall Street interest is a blessing for some Main Street owners looking to cash out. They don’t all see it that way, though.

In the Atlanta area, Jay Cunningham says he gets several pitches a week from PE-backed firms wanting to buy his Superior Plumbing — one of the few sizeable local firms that hasn’t already been snapped up by investors — or from investment bankers wanting to bring Superior to market. He’s not interested.

“I probably think they’re a nuisance as a whole,” Cunningham says.

In terms of dollar value, PE acquisitions of publicly traded companies or those bought from other private equity firms still make up the biggest chunk of deals.

Even by that measure, though, purchases of founder-owned businesses — which in most cases are valued at under $100 million apiece — are on the rise.

They accounted for more than 43% of deal value in the first quarter of 2023, well above the typical levels in recent years, according to PitchBook.

‘Lot of Players’

Especially prized are firms with steady revenue, subscription models and electronic billing, says John Wagner, a New Mexico-based investment banker who helps small and midsize companies find buyers.

Better yet, he says, is a locally owned firm with strong revenue but high expenses — an opportunity to cut costs, increase efficiency and quickly boost the firm’s value.

In the Denver area, Steve Swinney is constantly hunting for lumber yards, steel fabricators, drywall distributors and kitchen-interior companies.

His Kodiak Building Partners started out buying one steel fabrication firm 12 years ago, in the wake of the Great Recession.

It’s made about 40 acquisitions since then, and welded them all into a building-materials firm with sales of around $3 billion.

As it looks for more mom-and-pop firms to buy, Kodiak — which is majority owned by New York-based PE firm Court Square Capital Management — faces plenty of competition.

“There’s definitely a lot of other players out there,” Swinney says. “I wish we were alone.”

John Loud gets as many as 30 solicitations a month for his Kennesaw, Georgia-based alarm installation firm, Loud Security Systems, which has about 60 employees and more than $7 million in annual revenue.

“It’s a non-stop barrage,” Loud says, and it’s been going on for years. He used to joke with employees: “If you want job security, save me from these calls and these emails.”

Open To Offers

Nowadays, though, Loud is entertaining offers. His two kids aren’t interested in running the family business, and at 56 he feels closer to the end of his career than the start.

He expects to continue with the firm after any sale, and keep 30% equity in the company, but figures his proceeds will be enough that if things don’t work out, “I’ll never have to go create a new business, never have to go to work.”

His longtime friend Cunningham, the Atlanta-area plumber, is comfortable for now holding onto Superior Plumbing, which has about 60 employees and $10 million to $15 million in annual revenue.

A couple years ago, the 61-year-old Cunningham says, he sent a rudimentary financial brief to an investment firm and the would-buyer shot back an offer for more than $60 million. But unlike many peers, his children are interested in taking over the firm at some point.

“Right now I have five kids in my business. That’s a combined north of 60 years of time,” Cunningham says. “If I sold for $60 million, it wouldn’t enrich my life at all.”

Updated: 7-17-2023

You Rang? The Super-Rich Will Privatize Us All

A huge range of talent — from chefs to nannies to accountants — are being hired by the wealthy and managed by their family offices.

The vanishings keep on happening. Chefs who have run wonderful restaurants fold their operations and disappear from the world of haute public dining rooms.

It’s happened in New York and in London in my experience. I’m sure you’ve noticed it too wherever you are a regular — or were, until the chef up and left.

You then hear rumors. So-and-so has been snagged by a billionaire. You see an occasional post on social media clueing you in to said chef’s new lifestyle: no more endless nights bent over bookkeeping, no more customers who think orange wine is made with citrus, no more no-shows, no Yelp.

I’d once in a while get a glimpse into these new lives: a surreptitious Instagram post from a private party in some inaccessible Manhattan tower; an off-the-record walk through the enormous kitchen of a private townhouse; or just a note about how wonderful it is to be picking herbs in a lovely estate you knew the cook could never afford.

This is an option nowadays not not just for chefs burned out by the daily grind of restaurants, but accountants, investment advisers, personal shoppers, nurses, veterinarians and security guards.

It’s not a bad life. These are experts whose services have become exclusive to the super-rich who can afford to wall away them away from the rest of the world1.

While non-disclosure agreements keep the specifics of these positions confidential, there are semi-exclusive hires that give a sense of why they can be attractive. I’ve known Liam Nichols for a few years now.

He’d worked at Momofuku Ko in New York City and Tom Kerridge’s restaurant at the Corinthia Hotel in London — excellent pedigrees. He was also a warm and wonderful presence wherever he cooked. Then, one day, like the unnamed chefs above, he vanished.

For months, the photographs he posted on social media were excruciating. There he was on a beach in the Caribbean, or kitesurfing on the bluest waters, soaking up the sun by a sailboat, sporting a smile so broad it was practically solar itself.

Had he come into money? In a way, he had: Liam had been hired to cook for the billionaire Richard Branson, founder of the Virgin Group, on 74-acre Necker Island, which he owns in its entirety, in the British Virgin Islands.

Sometimes, Liam would prepare meals for Branson’s visiting neighbor, Larry Page, the co-founder of Google, and owner of Eustatia, the island next door — as well as for other rich guests at the Necker resort (where the cost is upwards of $3,700 per night per room).

Giving up on a public-facing existence is becoming more of an option nowadays. The market for privatized services is growing because there are a lot more deep-pockets everywhere. Forbes says that millionaires control about a quarter of the world’s $431 trillion total wealth.

That’s roughly $105 trillion, more than the combined GNP of the US, China, Japan, Germany and India. The total population of those countries: about 3.3 billion people.

The number of millionaires in the world: 62.5 million, according to a 2022 Credit Suisse report. That statistic is expected to grow 40% by 2027. The richest 25 families in the world alone control more than $1.5 trillion.

For people used to — and tired of — working against layers of bureaucracy toward some merciless corporate bottom line, it is liberating to have only one real task: to make a wealthy owner (and his or her family and friends) happy.

Still, to borrow from F. Scott Fitzgerald, the rich are different not just from you and me but from each other. There are mere millionaires and then there are “ultra-high net worth individuals” — people so wealthy their families can operate as virtual fiefdoms.

To qualify for the lower end of the category, you need a net worth of $30 million. Even that may not be elite enough to manage your wealth through a family office — a dowdy term that belies the assets involved.

To be able to staff the operation, the usual estimate is a net worth of $50 million.

There are now about 8,000 single-family offices in the world. Most are in the US and Canada, where many of the richest people in the world reside.

Even as 85% of the world’s humans live on $30 a day, the rich proliferate everywhere — as do their family offices. Singapore had 50 family offices in 2018 but 1,100 now (and that may be an underestimate, according to my colleague Andy Mukherjee).

The city-state and the United Arab Emirates are magnets for the burgeoning market of regional plutocrats looking to sweep up financial expertise to manage their private wealth.

Apollo Global Management Inc. has joined the scrum of financial giants (including Blackstone Inc. and KKR & Co.) offering expertise to the world’s UHNWIs and their family offices.

That kind of wealth management doesn’t just mean making more money but spending it — from investing in philanthropic and environmental causes, to mitigating the scale of a clan’s conspicuous consumption, to paying the salaries of service providers — OK, servants.

In a related phenomenon, pop stars who would never have thought of performing at bar mitzvahs, weddings and birthday parties are now doing so-called “privates” because of the many customers able to afford their once forbiddingly exorbitant prices.2

Members of the new servant class can benefit tremendously from bidding by the rich for the best in class. For example, chefs who have run critically acclaimed restaurants can pick and choose the private homes they’d rather work in.

So can nannies — and chauffeurs and butlers, veterinarians and nurses, tailors and number crunchers. The advantages can be enormous.

Those considerations can be trumped by one thing: the unhappiness of your super-rich masters. The only way to shield yourself from the ire of your employer is a well-written contract.

You can’t depend on the regulations that protect most workers in a corporation. And forget about labor union guarantees.

Happiness is a fleeting thing — and it is especially fickle among people who believe they personally control everything via money spigots.

You don’t have to work for them to know this. I used to hang with some very rich friends, and one day I jokingly disagreed with them.

Or I think that was my transgression. I can’t really tell. All I know is that the annual invitation to their villas by the sea no longer comes in the mail. Sigh.

Liam didn’t make his billionaire employer unhappy. But preparing shepherd’s pie (Branson’s favorite dish) wasn’t going to get him into any culinary hall of fame.

Liam left the world of the super-rich after six months and returned to his roots in Norfolk, where he opened a small five-table restaurant called Store in Stoke Mill. He works very hard at all the things that make restaurants difficult. But he is happy. He just won a Michelin star.

Updated: 8-2-2023

Private Equity, Hedge Funds Brace For Coming SEC Overhaul

Regulators could adopt new rules for firms such as Blackstone and Millennium as soon as this month.

WASHINGTON—Private-equity and hedge funds are bracing for what could be the biggest regulatory challenge in years to their business of managing money for deep-pocketed investors.

The Securities and Exchange Commission is preparing to adopt a rule package as soon as this month aiming to bring greater transparency and competition to the multitrillion- dollar private-funds industry, people familiar with the matter said.

SEC Chair Gary Gensler has said he hopes to bring down fees and expenses that cost hundreds of billions of dollars a year.

Since the agency first proposed new rules for the industry last year, representatives of private equity, hedge funds and venture capital have met frequently with SEC officials to try to dissuade them, SEC meeting logs show.

They have lobbied lawmakers to push back against the SEC’s plans and formed a group to fight the final rules, which could differ from the proposal.

“This is probably the single largest and most impactful of all the things that the SEC is doing,” said Drew Maloney, president of the American Investment Council, which represents private-equity firms such as Blackstone, Apollo Global Management and Carlyle.

Private funds are generally available only to wealthy individuals and institutional investors such as pensions and university endowments, which hope for returns larger than what they can get from traditional stocks and bonds.

The SEC has long considered such investors sophisticated enough to fend for themselves with minimal regulatory oversight.

In recent decades, the SEC and Congress have repeatedly loosened regulatory and disclosure requirements for private funds and companies.

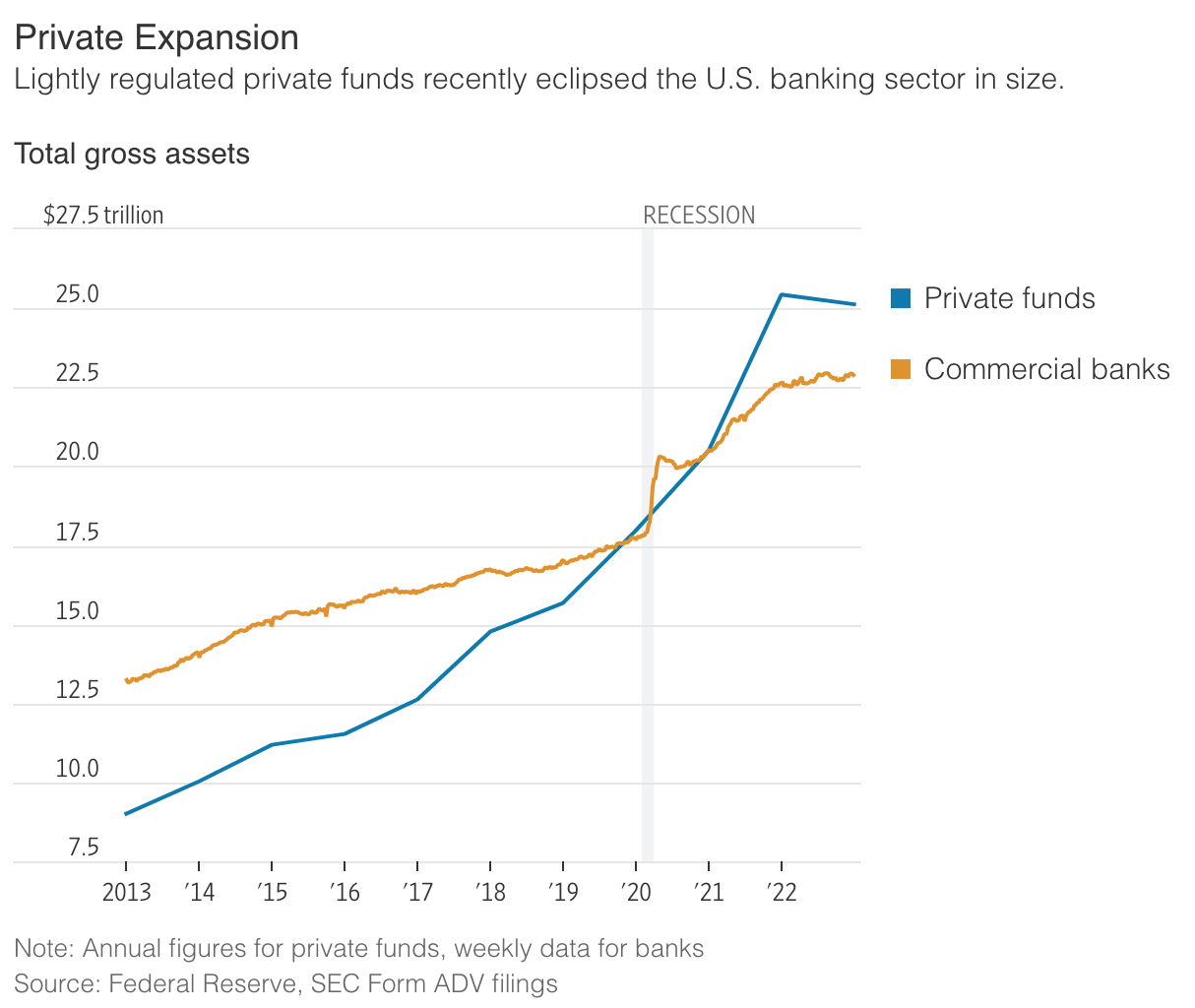

This move—combined with tougher rules for banks and years of low interest rates—ushered in a boom in private fundraising that surpassed the public market in the years before the pandemic.

Gensler said in a recent speech that private funds’ gross assets recently surpassed those of the commercial banking sector at more than $25 trillion. That is up from $9 trillion in 2012, according to SEC data.

Some policy makers have grown alarmed at the burgeoning size of the lightly regulated sector. They worry that private funds could pose risks to financial stability and to pension beneficiaries such as teachers and firefighters. Other concerns are that they might charge unfair fees or overvalue their holdings.

“Investors need increased transparency, more informative and useful data, and prohibitions on abusive and conflicted practices,” Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D., Mass.) and seven other Democratic senators wrote in a May 15 letter urging Gensler to complete the rules.

The SEC’s proposed overhaul would require private funds to provide investors with quarterly statements and annual audits, increase their liability for mismanagement or negligence, and prohibit them from giving some investors more-favorable terms than others.

In the 18 months since the SEC floated those ideas, private funds and their trade associations have fought to stymie the agency’s plans.

They argued that the SEC rule would hurt minority and women-owned funds, which currently manage a tiny percentage of overall assets.

After being lobbied by the American Investment Council on this concern last year, an industry official said, the House Appropriations Committee passed language encouraging the SEC to redo its economic analysis for the new rules.

Shortly after the proposal was unveiled, a group of hedge funds including Millennium Management and HBK Capital Management formed a nonprofit in Texas called the National Association of Private Fund Managers, said Bryan Corbett of the trade group Managed Funds Association.

The former group has no website and listed no individual’s name or contact information in a comment letter it filed to the SEC calling the private-funds rule “arbitrary and capricious.”

The group’s location in Texas would place it under the jurisdiction of a federal appeals court whose predominantly Republican-appointed judges have shown a penchant for reining in regulatory authority.

Millennium and HBK didn’t respond to requests for comment.

SEC officials have acknowledged that the industry is gearing up for a court battle.

“There’s a whiff of litigation in the air,” William Birdthistle, who heads the SEC division writing the private-funds rule, said at a May conference hosted by the Managed Funds Association, which represents hedge funds. Corbett said at the event that the MFA was preparing for a potential lawsuit.

The MFA has been vetting lawyers, looking for allies and developing legal strategies against the rules in case the SEC’s final version is similar to the proposal, Corbett said in an interview.

“The negative impact on the industry is significant,” Corbett said. “The word ‘existential’ I don’t think overstates it.”

The SEC rules would come in the midst of headwinds for some asset managers. Private-equity and venture-capital funds, which tend to invest in illiquid companies and are slow to mark down their valuations, are only beginning to show the effects of last year’s downturn in financial markets.

Benchmark private-equity returns turned negative for the year ended March 31 for the first time since the 2008-09 financial crisis, according to a Burgiss Group index that excludes venture capital.

Venture funds posted their longest streak of negative quarterly returns in more than a decade, according to PitchBook Data.

Private-fund managers are particularly anxious about the SEC proposal to prohibit them from limiting their liability for negligence, which would make it easier for a fund’s investors to sue managers over making bad investments.

Industry groups said that would drive up the cost of insuring against such litigation, crimping their returns to investors.

They are also worried about the SEC proposal to ban private funds from giving preferential terms to certain investors through what are known as side letters.

That would eliminate a marketing tool used by new funds to draw in big-name investors by offering them lower costs.

Updated: 8-3-2023

Private Credit Funds Move From Mergers To Timeshares And Car Loans

As banks pull back, the investment funds—cousins of private equity—make a move on Main Street debt.

Since the fall of Silicon Valley Bank in March, banks across the US have been maneuvering to shore up their capital while deposits shrink and investors eye their balance sheets.

The easiest way to do that has been to pull back on financing for small and midsize businesses as well as consumer credit companies such as buy now, pay later and auto lenders.

That’s provided a huge opening for the new rising power on Wall Street: private credit funds.

These funds, which are similar to private equity firms but focused on lending to instead of buying companies, manage about $1.5 trillion.

Some are run by private equity giants such as Blackstone Inc. and KKR & Co., others by specialty finance shops such as Castlelake and Atalaya Capital Management. Private credit is already an important source of funding for corporate buyouts.

Now the weakness of banks means there are deals to be had on investments in more Main Street forms of debt, such as asset-based loans, which can be tied to anything from auto financing to mortgages.

“The stone has been thrown into the pond, we are watching the ripples as they come our way, and we are trying not to show the smile on our face,” says Joel Holsinger, co-head of alternative credit at Ares Management, referring to the opportunities in asset-based lending.

For years, regional banks were among the biggest buyers of consumer loans. They were also a cornerstone of stability for smaller companies hoping to grow. But all that is now over.

At US banks below the top 25, deposits shrank by nearly $133 billion from the end of December to mid-July, on a seasonally adjusted basis, according to data from the Federal Reserve.

To retain capital, banks have begun selling many of the loans on their books. California-based PacWest Bancorp—which agreed in July to be acquired by Banc of California Inc. after being shaken by a drop in deposits—in June sold a $3.5 billion debt portfolio to Ares. It included consumer loans, mortgages and receivables on timeshares.

It isn’t only regional banks getting loan-shy, especially as the Fed discusses new rules requiring big banks to manage their balance sheets more conservatively.

“Large US banks are also retrenching from consumer credit to just stick to their core clients, and this will accelerate if proposed additional capital buffers are implemented,” says Aneek Mamik, head of financial services at private lender Värde Partners.

Värde has purchased about $1 billion in consumer personal loans made by Marcus, an online banking arm of Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Bloomberg News has previously reported.

Private credit has been making inroads with financial-technology companies, becoming more embedded in the consumer economy. KKR bought as much as €40 billion ($44 billion) of buy now, pay later loan receivables from PayPal Holdings Inc.

Atlas SP Partners, the credit unit Apollo Global Management Inc. bought from Credit Suisse Group AG, was part of a deal to buy a pool of consumer loans from a US credit union.

Castlelake also agreed to purchase up to $4 billion of installment loans from online lender Upstart Holdings Inc.

Private credit funds’ willingness to offer borrowers more flexible terms than banks—not to mention their stockpiles of capital—have also gotten the attention of small- and midsize companies shopping for lines of credit or loans backed by their assets.

“It’s a completely unfair fight,” says Randy Schwimmer, senior managing director and co-head of senior lending at Churchill Asset Management, which specializes in midsize companies.

Construction company Orion Group Holdings Inc. had a $42.5 million revolving loan with Regions Bank and other lenders. It’s been replaced by a $103 million financing deal with private credit shop White Oak Global Advisors, according to White Oak partner and President Darius Mozaffarian.

When the independent filmmaker New Regency needed additional capital for new projects, it turned to private lender Carlyle Group Inc. as banks pulled back, says Ben Fund, managing director at Carlyle.

Configure Partners, a firm that helps corporate borrowers obtain financing, has already seen the shift. A year ago regional banks represented about a quarter of lenders in any given deal.

Now they’re only about 15% of the total, with private credit filling the gap, says managing director Joseph Weissglass.

Conditions that benefit private lenders are worrying for the economy more broadly. Even before Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse, rising rates were making capital more scarce and putting pressure on already-struggling companies.

“Lack of available credit is a concern—it would be bad for the consumer as well as small businesses,” says Dan Pietrzak, global head of private credit at KKR.

But private credit is unlikely to rescue everyone. Used-car dealer and subprime finance company American Car Center, which was backed by York Capital Management, reached out to private lenders at the end of 2022 when it was struggling to find traditional financing, according to a person with knowledge of the matter.

It ultimately went bankrupt in March. A representative for York Capital declined to comment.

Other consumer finance companies may follow the same trajectory. When unable to obtain debt from banks or private lenders, they’ll end up closing their doors. That could leave consumers with fewer options to access credit for purchases from cars to houses.

It’s already started to happen: A Federal Reserve survey in July showed that Americans are increasingly likely to get turned down when they apply for credit.

“Ultimately, the prospect of less competition—and the need to make profitable loans—means consumer rates will inevitably rise,” says LibreMax Capital Chief Investment Officer Greg Lippmann.

The expansion of private credit into more parts of the economy also raises questions about transparency. The managers of the funds aren’t as closely watched by regulators as banks and there is less visibility on the performance of their investments compared with public markets. But increasingly for some borrowers, private credit is the only show in town.

Updated: 8-7-2023

Private Credit’s $10 Billion Win Is Bad News For Wall Street

* Some $10 Billion Of Leveraged Loans Have Been Refinanced

* Direct Lenders Look For More Business Amid Light LBO Volume

Private credit is muscling in on another market traditionally dominated by banks: debt refinancing.

Companies with leveraged loans and junk bonds coming due soon are increasingly turning to private credit lenders to refinance their obligations, with around $10 billion of the loans having been replaced in recent weeks.

Thoma Bravo-owned Hyland Software Inc. is turning to a group led by Golub Capital to refinance about $3.2 billion of maturing debt.

That deal came after a record-breaking $5.3 billion refinancing package for Finastra Group Holdings Ltd., a financial software firm backed by Vista Equity Partners.

A group of private credit lenders stepped in after the company saw its ratings cut and faced a potentially painful negotiation with existing creditors that had organized and hired a financial adviser and legal counsel.

For years, private credit lenders have been providing financing for leveraged buyouts, funding deals that would have otherwise relied on the syndicated loan or junk bond markets.

That’s translated to Wall Street banks missing out on lucrative underwriting fees, cutting into an important stream of revenue for the firms.

But leveraged buyout volume has been relatively light this year. With fewer deals to fund, private lenders are looking for other ways to deploy their dry powder, which amounts to $443 billion globally as of September, according to estimates from research firm Preqin. Refinancing looks like an attractive opportunity to the firms.

“It’s private credit coming out of the shadows,” said Ranesh Ramanathan, co-leader of Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld LLP’s special situations and private credit practice. “Private credit is now part of the recognized pool of capital you’d look to.”

For companies, refinancing with private credit lenders will often cost more in terms of interest paid. But going the direct lending route offers financing that is highly likely to close, at a time when leveraged finance markets can be all but shut for weeks.

And while banks will look to sell leveraged loans or junk bonds to dozens of investors, potentially leading to protracted conversations among many parties on pricing and other terms, private credit deals typically involve just a few lenders.

Medical device manufacturer Tecomet, backed by Charlesbank Capital Partners, recently refinanced

more than $1 billion of broadly-syndicated debt with the help of private credit lenders.

Many leveraged loan borrowers refinanced debt in late 2020 and 2021 when rates were low and credit markets were strong, but there are still companies with upcoming debt maturities.

About 2% of the roughly $1.4 trillion US leveraged loan market matures in 2024, and another 10.3% matures in 2025, according to data from Barclays Plc. Companies typically refinance debt at least one year in advance, meaning borrowers are looking closely at how to deal with loans maturing in 2025.

Competition from private credit could weigh on the growth of the leveraged loan market, according to Barclays strategists.

“With alternative financing sources such as private credit and secured bonds continuing to take share from loan primary markets,” there could be “further headwinds for growth of the loan index, which has already fallen by $38 billion from its peak of $1.436 trillion in September 2022,” wrote Barclays strategists in June.

Deals:

* A group of private lenders including Blue Owl Capital Inc. and Blackstone Inc. is providing $2.7 billion of debt to help fund BradyIFS’s acquisition of competitor Envoy Solutions.

* Vietnamese financial firm F88 Investment JSC has secured a $50 million private loan to help expand its presence in the country’s non-banking sector.’

* Blackstone’s credit unit is supporting Permira Holdings’ takeover of biopharmaceutical services firm Ergomed Plc with a £285 million debt package.

* A trio of private lenders including Blackstone agreed to provide a £180 million loan to help finance GTCR’s acquisition of compliance and supply chain management software platform Once For All.

Fundraising:

* Blackstone’s nearly $50 billion private credit fund for affluent individuals attracted the most capital in more than a year, as the asset class sees a rebound in fundraising.

* Asset manager Phoenix Holdings announced a partnership to invest as much as $2 billion with Apollo Global Management Inc. in Israel.

* Former Goldman Partners Join Private-Credit Rush In New Venture.

* New York-Based Duo To Focus On Direct Lending In US And Europe

* 5C Joins Wave Of Firms Betting On Fast-Growing Market

Former Goldman Sachs Group Inc. partners Tom Connolly and Mike Koester are betting on one of the hottest corners on Wall Street for their next act.

The New York-based duo have co-founded a new firm, 5C Investment Partners, that aims to capture a slice of the burgeoning private credit market, where alternative asset managers are increasingly displacing banks by providing multi-billion financings to companies.

“Direct lending is playing a very important role during a market dislocation that is persistent,” Koester said in an interview Thursday, referring to regulation that has curbed bank lending since 2008. “There are credit-worthy companies that need financing.”

Many Wall Street veterans have sought to capitalize on a yearslong shift that’s seen more capital flow into the hands of private credit managers.

Josh Harris’s 26North Partners and Dan Loeb’s Third Point have both made high-profile hires in recent weeks to push into direct lending.

Connolly and Koester are not new to the trade. At Goldman, they helped the bank develop its direct lending business and raised a $10 billion credit fund after Bear Stearns had collapsed.

“They have a very strong record, and it’s not a surprise they’re trying to repeat the success of their collaboration,” said Bjarne Graven Larsen, founder and CEO of Qblue Balanced, a Copenhagen-based asset manager, who recalls committing more than $4 billion to that Goldman fund during his tenure as chief investment officer at Danish pension fund ATP Group.

“It was well-timed and well-structured, and some of the first investments were credits out of the Lehman bankruptcy at roughly 30 cents on the dollar which led to great returns that I’d never seen before from a loan fund.”

Old Mantra

5C, which describes itself as a credit-centric alternative investment firm, will be initially focused on the US, with scope to expand in Europe. Connolly, who estimates an addressable market of $3 trillion in coming years, believes there’s room for independent platforms despite increased competition among direct lenders.

The firm’s name is a nod to the “five Cs of credit” a lending framework Connolly and Koester learned as young credit traders at Bankers Trust in the 1990s. The five Cs — capacity, capital, collateral, conditions and character — were emblazoned on mugs the firm’s chief credit officer handed out.

“We are fundamental investors in everything that we’re doing, and these are five incredibly important tenets for investing, underwriting and lending,” said Koester, citing character — or the reputation and behavior of borrowers — as the top principle.

Connolly, who made partner at Goldman in 2004 and held roles including global co-head of private credit, left

the firm last year. Koester, who became partner in 2008 and held roles including co-president of alternatives of Goldman Sachs Asset Management, left in April.

“I am looking forward to Mike and Tom being important clients of Goldman Sachs in their new venture and believe this is the powerful Goldman Sachs ecosystem in action,” Alison Mass, Goldman’s chairman of investment banking and leader of its alumni engagement effort, said in an emailed statement.

Updated: 8-8-2023

Private Equity Giant David Rubenstein Makes The Case For Bitcoin

Asset management leader BlackRock’s interest in a spot bitcoin ETF is among the signals that the cryptocurrency isn’t going anywhere, said the Carlyle Group co-founder.

Billionaire private equity titan David Rubenstein believes Bitcoin (BTC) is here to stay thanks to growing institutional interest as evidenced by BlackRock’s application for a spot bitcoin ETF, as well as general global demand for a form of money that can’t be controlled by governments.

“A lot of people around the world want to be able to trade in a currency that their government can’t know what they have and they want to be able to move it around rightly or wrongly and so I don’t think bitcoin is going away,” he said during an appearance on Bloomberg TV Tuesday.

The co-founder and co-chairman of private equity giant Carlyle Group, Rubenstein admitted his regrets for not having bought bitcoin when it was at $100.

He said that people who once mocked the crypto and the sector in general might be forced to take another look given recent interest from traditional finance giants like BlackRock.

“What’s happened is people made fun of bitcoin and other crypto currencies but now the establishment, Larry Fink at BlackRock, is now saying they’re going to have an ETF if approved by the government in bitcoin so you’re saying wait a second, the mighty BlackRock is willing to have an ETF in bitcoin, maybe bitcoin is going to be around for a while,” he said.

Rubenstein has previously disclosed that he is personally invested in companies that facilitate crypto trading, although not owning any cryptocurrencies directly.

Speaking about recent enforcement actions from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), led by Chair Gary Gensler, Rubenstein said that Ripple’s win in a recent case proves that the agency has not yet convinced the courts that cryptocurrencies are “bad.”

Blackstone Says Private Credit Is Coming For Asset-Based Debt

* Rob Camacho Expects Lenders’ Capabilities In The Space To Grow

* Sees A ‘Symbiotic Relationship’ Between Banks, Private Credit

Private credit lenders are just getting started in the world of consumer and asset based finance, according to Rob Camacho, Blackstone Inc.’s co-head of asset based finance within the firm’s Structured Finance Group.

“Today, we are a very small portion of the whole asset based finance market,” he said in an interview. “There’s a lot of room to run.”

Camacho spoke over a series of interviews that ended on Sept. 6. Here are some highlights of the conversation, which have been condensed and edited for clarity.

Asset based finance has become the hot new thing across credit markets. Why is that?

That’s certainly true and has to do with the current environment. A couple of years after the start of my career in 2004, the Federal Reserve brought rates over 5%, so investors were getting real yield in fixed-income.

But that was short-lived. We then went through more than a decade of near-zero interest rates.

This is the first time we are seeing higher real yields. All of a sudden, you can get high returns for investment-grade paper. That hasn’t happened in almost two decades.

Second, some buyers such as insurance companies tend to prefer longer duration to match their liabilities. That dynamic has also made asset based finance much more important for firms such as ourselves, who manage money for insurers.

The regional bank asset sales have also played a role in this. What do you see coming in the next few months?

A lot of what we’re doing is partnering with regional banks. They have internal loan origination capabilities through relationships with local platforms that make auto loans, home improvement loans and any other product that is important to their deposit base.

We can buy those loans, but we can also partner with them to augment their business, meaning they originate the same or more, but don’t keep all of it on their balance sheet.

Many banks are calling us to partner with them to continue serving local consumers. This generates fee income for the bank, and provides our clients high quality loans.

As the cost of private capital is higher and there’s just less of it around, will consumers end up struggling?

Something that deserves acknowledgment is how smooth this volatility has been for consumers. In 1994, when interest rates spiked, there was a lack of credit that made the Fed cut rates by July of ’95.

This year, we’ve had both bank failures and rapid interest rate increases.

And now we are seeing a symbiotic relationship between banks and private credit, where lending gaps are being filled instantaneously.

From my perspective, it’s been remarkable that we haven’t had a larger contraction of credit at the consumer level. That’s probably one of the things encouraging a lot of people to change their calls to a soft landing – if credit was unavailable and with the consumer being two-thirds of the economy, we might have a different outcome.

The volatility of the asset backed securities markets this year and last year also contributed to more companies turning to private lenders. But is the trend here to stay?

The public ABS market is a great option for originators to distribute risk and raise capital. But we are talking with companies and banks who use ABS about how to diversify their funding models.

We’ve bought loans from these firms, be it consumer or other types of loans, when the securitization markets were active.

The volatility in the ABS market last year reinforced what we’ve supported for a long time: The importance of having a diversity of funding sources such as securitization, forward flow and balance sheet.

Partnering with private credit managers that can provide capital from longer-dated insurance liabilities is a great way to achieve this, where there isn’t the dynamic of demand deposits that can disappear overnight.

We believe that every originator should be thinking this way.

Private credit took on corporate markets first and is now handling multi-billion dollar financings, competing with banks for those transactions. Will we see something similar in asset backed financings?

I am biased, of course, but just as an anecdote: We’ve done several transactions over the past year close to a billion dollars, and one that brought our commitment over that mark. So, the capabilities of private debt within asset based finance are just going to expand.

Large-scale players who need asset based debt will prefer to work with a single manager able to commit to those transactions. It will become more appealing over time to borrowers and investors, especially if the current yield environment persists.

Today, we are a very small portion of the whole asset based finance market. There’s a lot of room to run.

Right now, most of the companies that borrow this type of debt are small- or mid-sized firms with barely any corporate debt, right?

You’re hitting the nail on the head. A loan originator’s largest liability is their ability to sell loans and continue their business. Therefore, originators tend to have very conservative capital structures.

We’re partnering with them over time and it’s important they can service their customers. That’s really what we care about. Our customers are insurance companies and pension funds.

Their customers are the consumers, and we need those consumers to have a good experience.

But to be clear, it’s not just consumer loans — it’s everything. We have aircraft loans, fund finance and renewables like commercial and industrial solar.

We have quite a large business of financing critical infrastructure such as cell towers as well as intellectual property.

We’re financing all those things, and we really have just scratched the surface. As interest rates continue to remain where they are, more and more companies are going to be more efficient with their balance sheet, so many more assets are going to become financeable.

Do you think we will see bigger originators, even ones that tap the investment-grade corporate bond markets, look for this type of financing from private lenders?

A lot of folks that utilize asset based finance are companies that don’t have access to the broadly syndicated corporate bond market. However, I think you will see investment-grade companies tapping the asset based debt market.

We certainly would love to engage in conversations with corporates and seek out places where we can provide flexibility. The corporate bond market is very standardized and that’s what makes it great and low cost.

Still, there are companies that obviously have very specific assets on their balance sheet or a specific need where a financing solution can be customized. We can offer that.

I think we are going to see some companies be quite strategic around financing and start to say, ‘Instead of issuing this huge corporate bond and risk our credit rating, why don’t we call private lenders and get customized solutions for these assets?’

Updated: 8-14-2023

Private Equity Firms Are Slow To Sell Holdings Amid Higher Rates

The market is reeling from a long series of crises including Covid, war, inflation and bank failures.

Here’s a normal thing that happens. You buy a house, renovate it, throw a housewarming party, and you stay there. For a long time. Pretty typical, right?

Well, yes. But what if the people who lent you money to buy the house don’t get repaid until you sell? If you hang on to the property, they’re stuck.

That, in a sense, is the situation in which the private equity industry finds itself. The firms are holding on to the businesses they acquire for increasingly long periods, and their investors are waiting for their payoff.

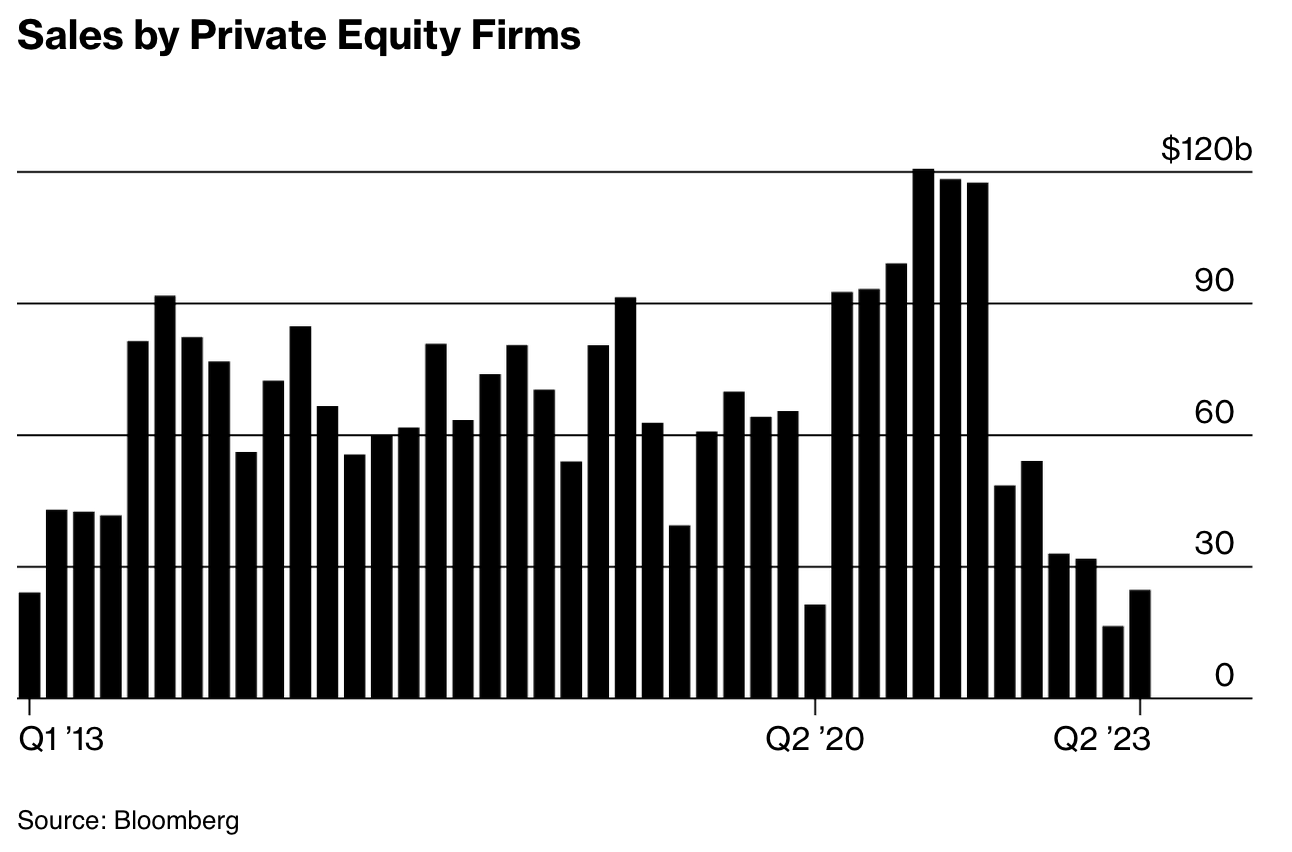

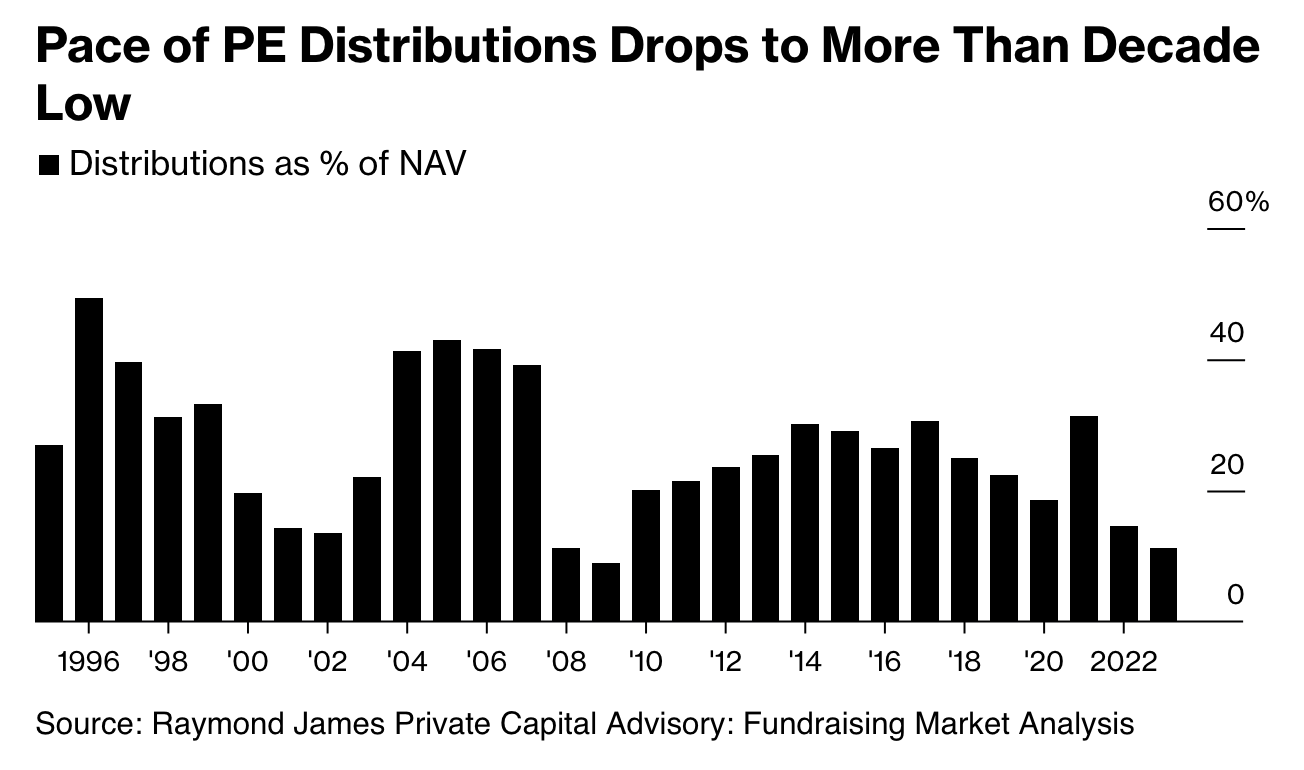

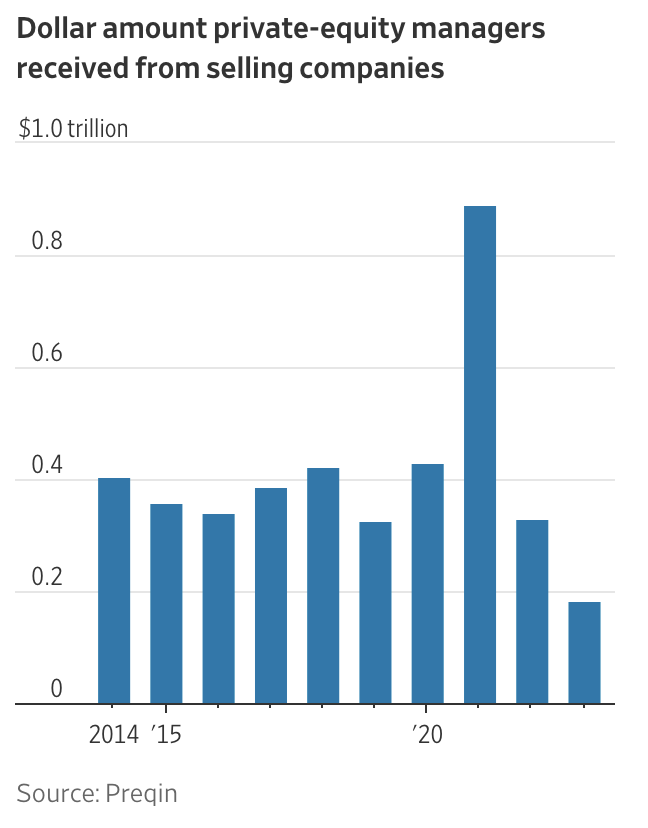

Private equity “exits”—via sales or initial public offerings—have fallen to their lowest level in a decade, excluding the pandemic-hit second quarter of 2020, when the global economy stalled.

“This slowdown came on the heels of such a hot year in 2021,” says Emily Anderson, managing director of sponsor coverage at the investment bank Union Square Advisors LLC.

“We had Covid, lots going on in the political environment, interest rates, the Silicon Valley Bank crisis, the war in Ukraine—that’s a lot of hits for one market to handle in a short time horizon.”

To be clear: Private equity firms do want to sell. But only for the right price. And caution is rampant among buyers—including the firms themselves. Every year a fair portion of companies sold by PE firms are bought by other PE firms.

Today those firms are sitting on a record pile of unspent capital: about $1.5 trillion, according to Preqin Ltd., the investment data company.

Since most deals are at least partly debt-funded and interest rates are high, private equity barons are less eager to open their checkbooks.

Amid all of this, those who’ve staked money in private equity want to see some of that money returned. That’s prompted PE firms to rifle through their portfolios to find non-plum assets to sell, even though, all things being equal, they’d probably rather wait and get a higher price further down the line.

A few are eyeing IPOs, even as the market remains tepid. SoftBank Group Corp. is targeting a prospective $60 billion September listing for its semiconductor unit Arm Ltd.; L Catterton wants to take Birkenstock to market at an $8 billion valuation at around the same time. They’ll be big tests to see if things might just start to loosen up.

Updated: 8-16-2023

Brookfield Chases Rivals For Private Equity’s New Money-Spinner

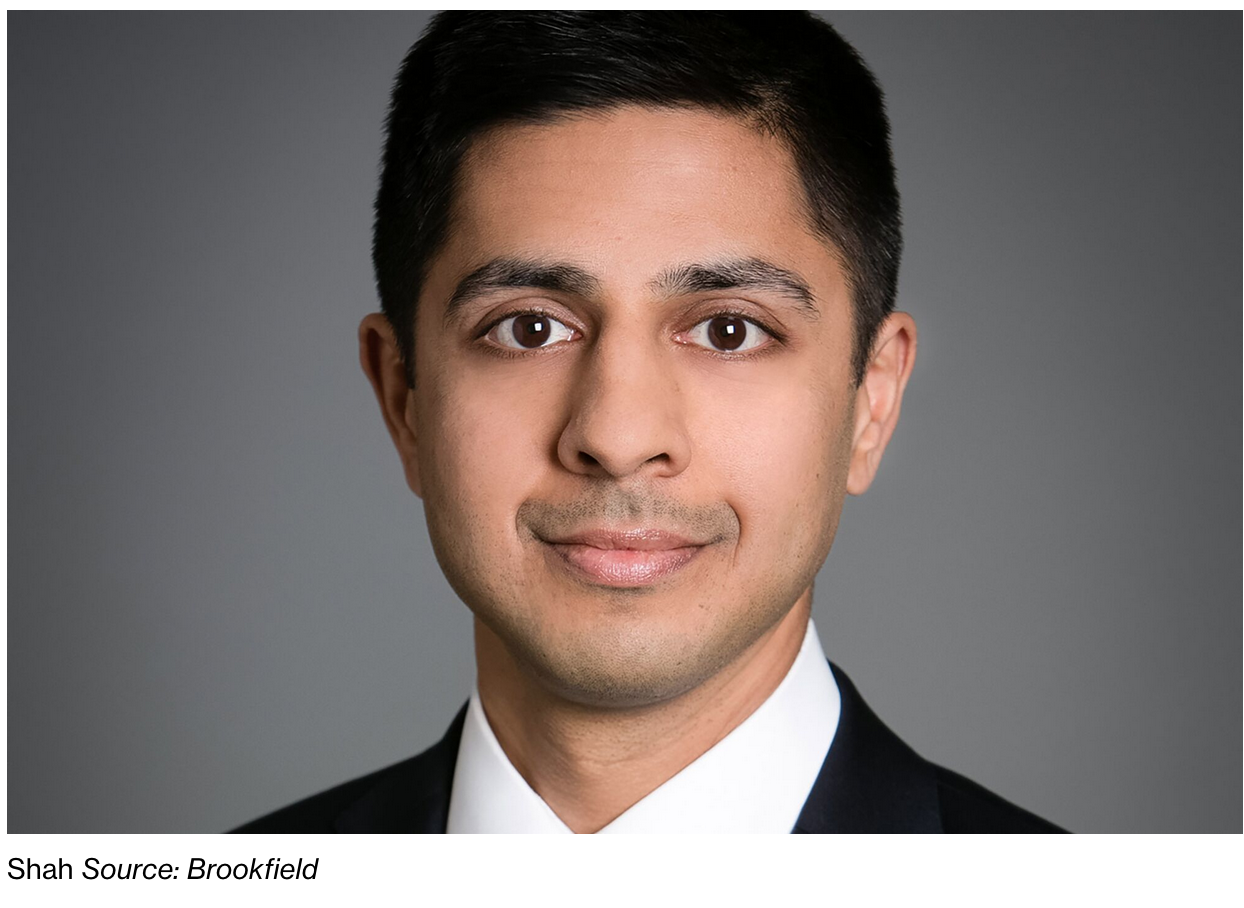

Sachin Shah is leading the giant Canadian investment firm into a business that’s earned rich rewards for its private equity peers.

Sachin Shah, a senior executive at Canadian investment giant Brookfield, could not contain his frustration.

Shah was in the company’s Toronto headquarters listening to a presentation by a group of employees who’d flown in from Brazil.

The numbers were good, but Shah was annoyed by the team members’ style and even accused them of lying, according to a person familiar with the event who asked not to be named discussing internal matters.

The next morning, at the Shangri-La hotel where the company was having an off-site meeting, Shah fired the team’s head and sent him back home.

The abrupt dismissal in 2019 rattled people within the company, but it cemented Shah’s reputation as a hard charger. Today, he’s bringing his forceful style to bear on a different assignment—helping Brookfield muscle into a new business: insurance.

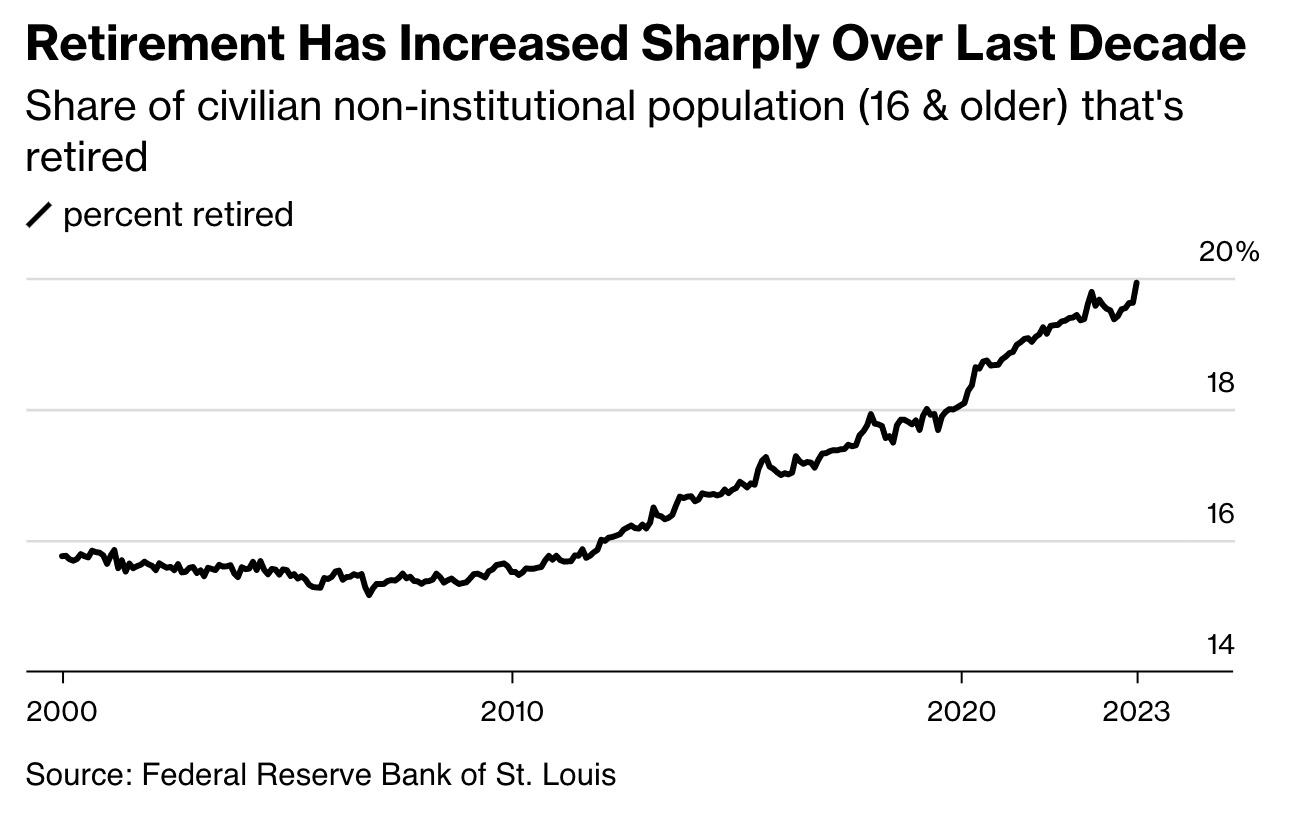

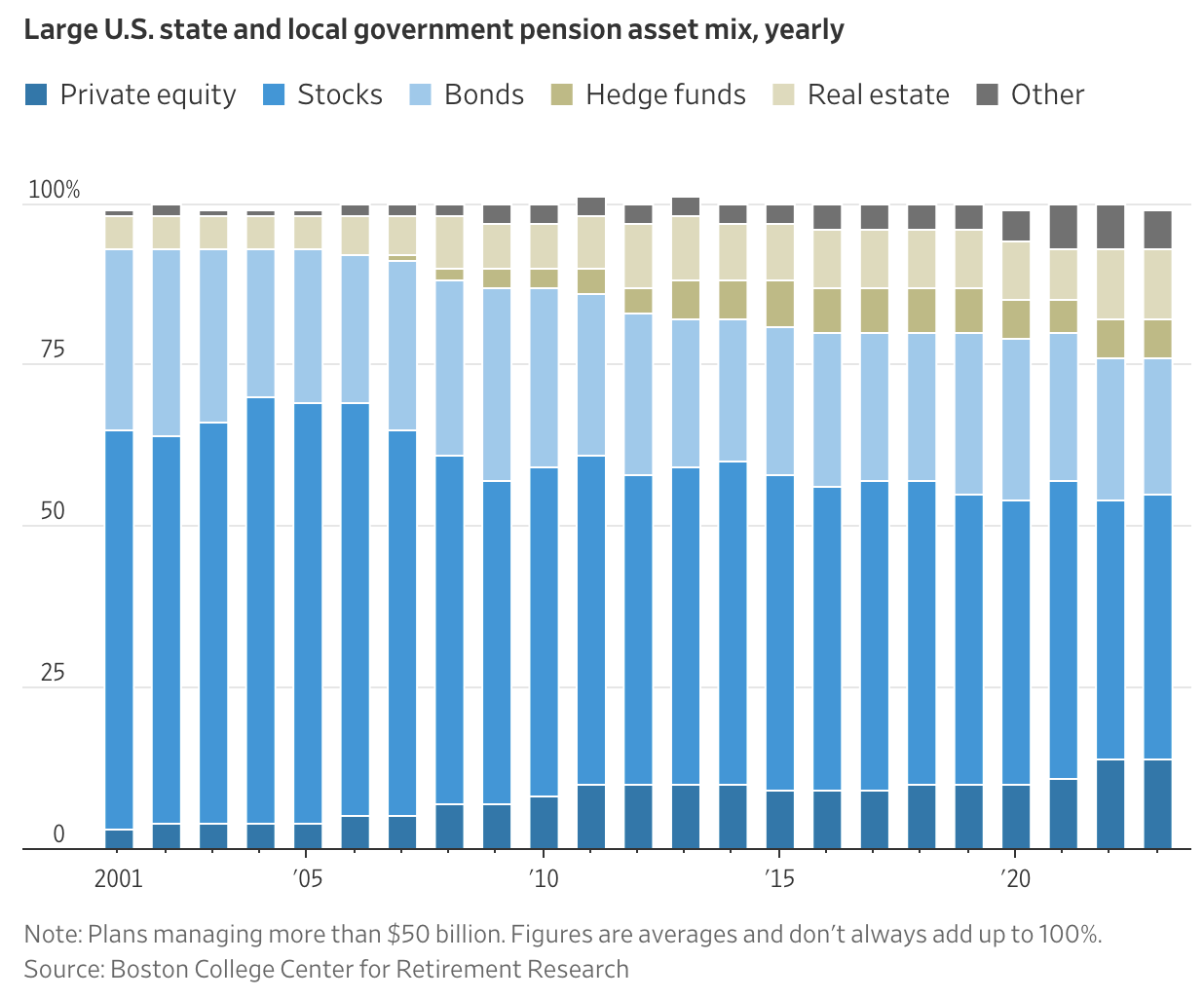

It’s a market that Brookfield’s private equity peers have been playing in for years. The idea is that insurance companies generate billions of dollars in premiums that need to be invested to ensure there’s enough money to pay future claims.

Those premiums provide a rich source of so-called perpetual capital at a time when raising money from traditional clients such as pension funds and endowments is getting tougher.

And the private equity firms earn fees—1% to 2% in Brookfield’s case—for managing that money. As of the end of June, Brookfield was earning fees on $110 billion of money from its own affiliates, including the insurance unit, accounting for about a quarter of the company’s fee-bearing assets.

Those fees will help Brookfield expand its investments, which range from 4G cell towers in India, to hydro plants in Colombia, to the glittering Manhattan West development in New York.

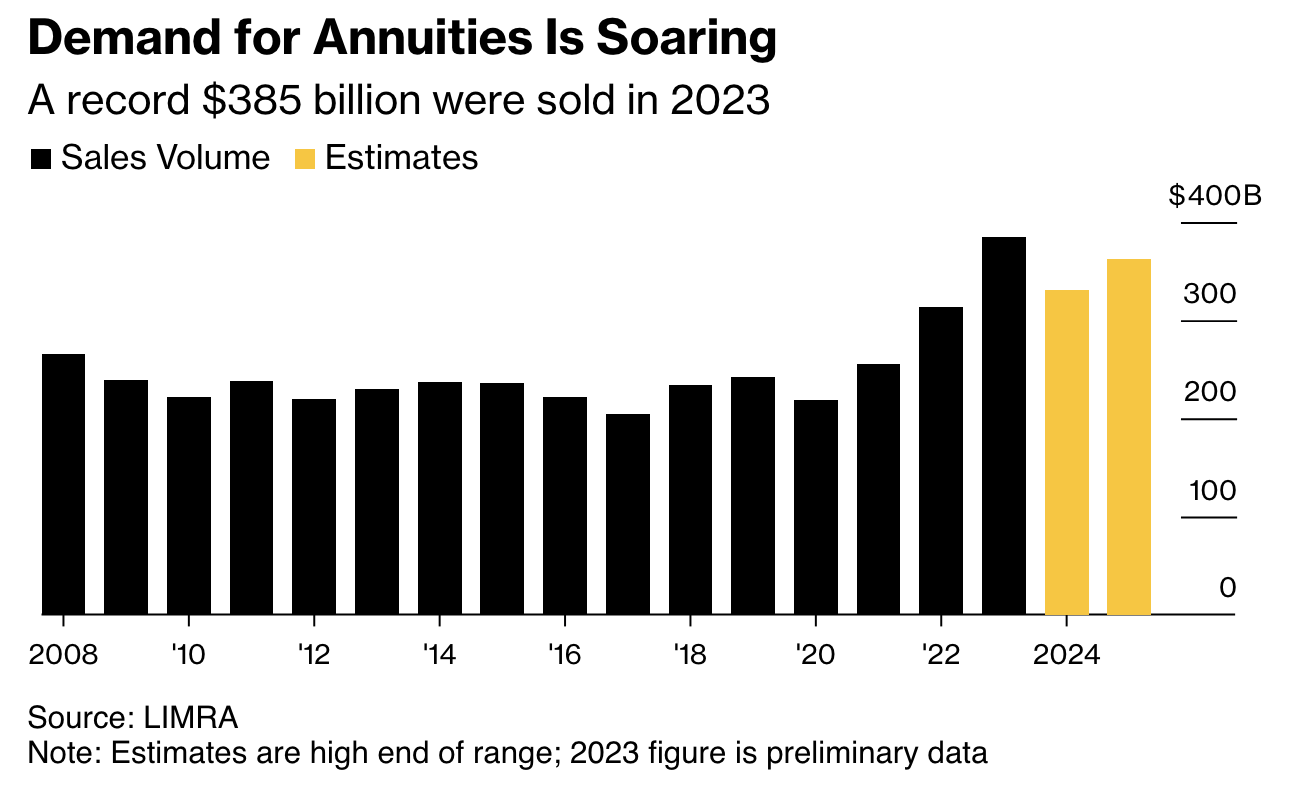

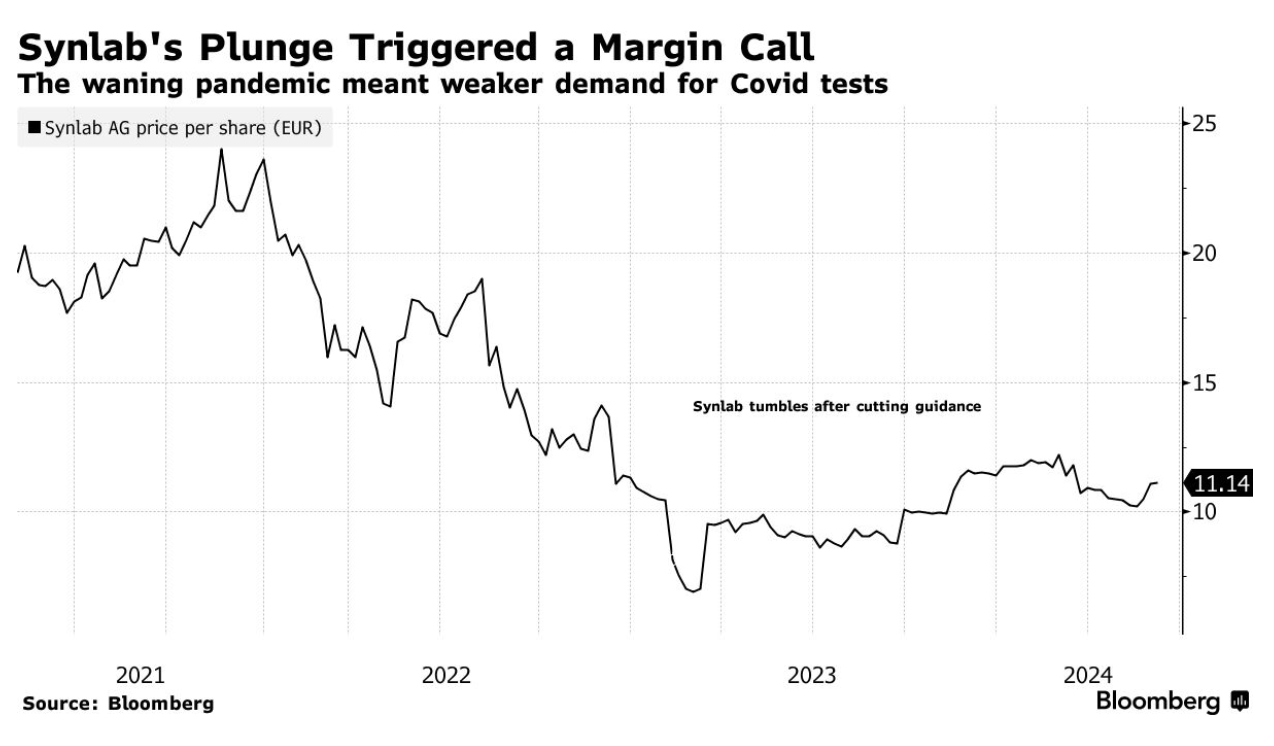

Apollo Global Management Inc. was the first big private equity firm to dive into insurance when it co-founded annuity provider Athene in 2009. Blackstone Inc. and others soon followed. Apollo is now reaping the rewards of its bet on Athene, which it bought outright in a deal that closed last year.

The business accounts for the majority of Apollo’s earnings and propelled the firm to a record $1 billion profit in the second quarter.

Now, Brookfield Asset Management—which oversees about $850 billion, making it the world’s second-largest alternative investment manager—is trying to catch up.

Since launching Brookfield Reinsurance Ltd. three years ago, Shah, the chief executive officer, has directed a buying spree that will lift the company’s insurance assets to $100 billion.

“We all feel like the prospects for this business are really strong,” Shah says during an interview in Toronto. “The growth outlook is better than it’s ever been.”

The most recent deal, for American Equity Life Holding Co., bore the hallmarks of his aggressive style. Brookfield holds a stake of about 20% in the Des Moines-based company, and Shah had a seat on the board.

But the insurer signed a multibillion-dollar deal with New York-based private investment firm 26North Partners—run by Apollo co-founder Josh Harris—despite Brookfield’s objections.

Shah was worried about the risks of the investment. It didn’t help that Mark Weinberg, a 16-year Brookfield veteran, had just been hired by 26North.

Shah resigned his seat on the American Equity board and engineered Brookfield’s takeover of the entire company for about $4.3 billion, a deal that’s expected to close next year.

Sitting in a conference room on the first floor of Brookfield’s nondescript office, Shah, 46, hardly comes across as a shark. He’s serious, soft-spoken, unfailingly polite. Indeed, Brookfield overall tends to give off a conservative air. Men are expected to wear suits and ties.

Beards are frowned upon, as are Wall Street-style extravagances. Executives in Toronto, New York and London typically use public transportation and fly economy class.

Old-school face time is a must. Even during most of the pandemic, Brookfield maintained a strict work-from-the-office policy.

On the surface, Shah fits the mold. An accountant by training, he’s spent 21 years at Brookfield, working his way up from corporate finance to head of the renewables business and chief investment officer of the firm. Yet inside Brookfield Place, Shah stands out in several ways, including a big one: money.

In 2022 his pay package totaled $8.3 million. That exceeded the compensation of Brookfield’s chief executive officer, Bruce Flatt, who got $7.8 million. Shah declined to elaborate on his management style during an interview, and the company declined to comment.

Another Shah deal shows the synergies between insurers and PE firms. In a $5.1 billion transaction completed in 2022, Brookfield acquired American National Insurance Co., a 118-year-old insurer based in Galveston, Texas, that does business in all 50 states and Puerto Rico.

Brookfield promptly began steering American National cash into credit, including real estate and infrastructure debt —investments Shah and his team think are a good match for insurance because they represent long-term bets.

The Reward So Far: $685 million, in the form of dividends that American National has sent upstream to Brookfield. The US insurer paid $155 million in dividends the year before the acquisition.

As part of Brookfield, both American National and American Equity will direct more money into alternative assets such as private debt funds.

Brookfield Asset Management’s president, Connor Teskey, recently told analysts that the company plans to allocate about 40% of its insurance assets to its private funds over the next few years, up from 6% today.

Critics have begun to worry that everyday policyholders might get hurt if insurance money is tied up in investments that can be difficult to sell or take years to pay off.

American National, with more than 5 million policyholders, has transferred $10 billion of insurance business through reinsurance with a Brookfield affiliate in Bermuda.

Such a maneuver, which has been employed by other private-equity-backed insurers, has enabled American National to offload some of its liabilities to an entity outside the reach of US regulators.

That means US policyholders are now counting on a company that’s not regulated in the country to make good on the promises in their policies. It also reduces American National’s liabilities, which in turn reduces the capital it’s required to have on hand to meet those obligations.

“I must admit that I am disappointed that Brookfield not only chose to significantly increase American National’s risk profile, but they also seemed in quite a hurry to do it,” says Tom Gober, a forensic accountant who’s briefed the US Department of Labor and the Senate Banking Committee on private equity’s involvement with insurers.

Michael McRaith, Brookfield Insurance Solutions’ vice chair, says that delivering value to policyholders and clients in Iowa, Texas and Bermuda, where its insurance companies and affiliates are domiciled, is a high priority.

“All three of those jurisdictions are held in high regard by regulators around the world.”

Shah has no qualms about insurance becoming an increasingly important component of Brookfield’s business. “Just go back five years, Brookfield was known for infrastructure, real estate, private equity, renewables,” he says. “There’s a whole new business that was created within a few years, and now it has scale.”

Updated: 8-17-2023

Private Credit Loans Are Growing Bigger And Breaking Records

* Finastra $5.3 Billion Loan Deal Is Biggest Ever In Asset Class’

* Private Credit Funds Raising Large Cash Pools For Jumbo Deals

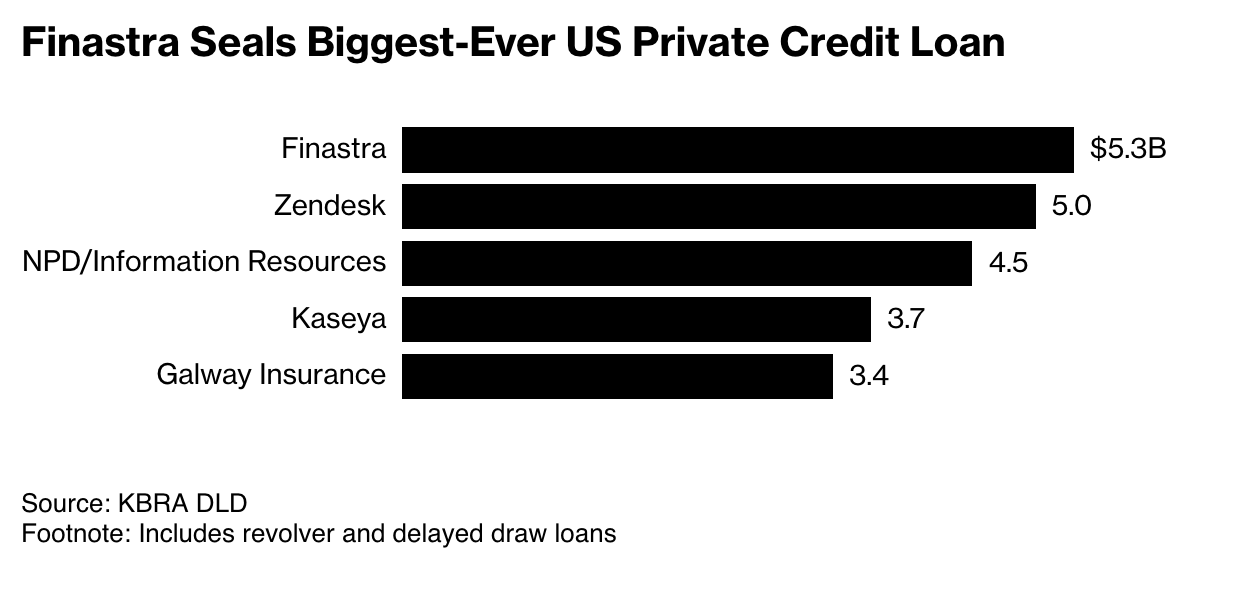

The $1.5 trillion private credit market just set a fresh record for the largest loan in its history. With growing firepower, direct lenders are poised to take ever more deals away from banks and from the junk bond and leveraged loan markets.

Private lenders including Oak Hill Advisors LP, Blue Owl Capital Inc. and HPS Investment Partners LLC are providing a $5.3 billion loan package to Finastra Group Holdings Ltd., a fintech firm owned by Vista Equity Partners.

Comprising a $4.8 billion unitranche, a blend of senior and subordinated debt, and a $500 million revolver facility, the financing is the biggest private credit loan ever in the US, according to data by KBRA DLD.

It’s been a dramatic rise. Even as recently as four years ago, a $1 billion private loan was a rare event and anything above $2 billion was simple aspiration. And back then, few borrowers

who could tap the junk debt markets would opt instead for a private loan.

But with banks still reluctant to commit capital to risky loans, borrowers have been flocking to direct lenders.

Now Finastra has exceeded the record set by Zendesk Inc.

a year ago with its $5 billion bundle of private debt. And private lenders and Wall Street banks are engaged in a furious battle to win over financing deals.

The fresh record underscores the growing heft of the private credit market, which saw fundraising rebound last quarter, crops of new entrants and aspirations to score ever larger piles of cash.

Now Finastra has exceeded the record set by Zendesk Inc.

a year ago with its $5 billion bundle of private debt. And private lenders and Wall Street banks are engaged in a furious battle to win over financing deals.

The fresh record underscores the growing heft of the private credit market, which saw fundraising rebound last quarter, crops of new entrants and aspirations to score ever larger piles of cash.

What sets Finastra apart from many of the recent jumbo deals is the use of proceeds. The loan for Zendesk, an unused $5.5 billion package for Cotiviti Inc. and $3.4 billion for Galway Insurance

all served to finance buyouts. But Finastra’s loan refinances existing debt that the company raised in the US and European leveraged loan market.

That’s a reflection of the collapse in mergers and acquisitions, and especially leveraged buyouts, triggered in part by the surge in interest rates over the past year.

“For non-levered buyout sponsor backed deals, we have been working on different short-term refinancing opportunities that offer a single solution that is easy and at scale,” said Mike Patterson, a governing partner at HPS. “This can allow a company to delay selling itself for when the M&A market has normalized and valuation expectations are better aligned.”

Deals:

* Blue Owl and Oak Hill are providing a record $4.8 billion fully funded direct loan as part of Vista’s refinancing of fintech firm Finastra’s debt.

* Apollo is poised to sign more than $4 billion in so-called NAV loans to private equity firms looking to raise cash in a challenging high-cost environment.

* Qualitas Ltd. has obtained an additional A$750 million ($483 million) to be incrementally invested in Australian commercial real estate via private credit.

* TPG has lined up a group of private credit funds led by Ares to help finance its acquisition of Australian funeral home operator InvoCare Ltd., with a A$800 million ($521 million) of debt.

* Sixth Street acted as agent in a financing to Carlyle’s portfolio company HireVue with $310 million

facility.

Fundraising:

* Oaktree is looking to raise more than $18 billion in what would be the largest-ever private credit fund.

* Blackstone Inc. raised $7.1 billion for a fund to finance solar companies, electric car parts makers and technology to cut carbon emissions.

* Guggenheim Investments is seeking to raise at least $1.5 billion for its newest private credit fund.

* KKR is continuing its push into asset-based financing with the launch of KKR Asset-Based Income Fund, in which it has raised at least $425 million.

Updated: 8-20-2023

Zhongzhi’s Crisis Exposes The Perils Of Private Credit

Asset quality is deteriorating, but the bigger issue is the failure to ring-fence some products.

Zhongzhi Enterprise Group Co., one of China’s largest private wealth managers, is sending shockwaves through the country’s financial system.

Its affiliates have missed payments on dozens of products. Rare public protests erupted in Beijing as investors lost patience.

Stock traders sold off shares fearing that listed companies had invested spare cash into its funds. The conglomerate, which manages about 1 trillion yuan ($137 billion), plans to restructure debt after an internal audit.

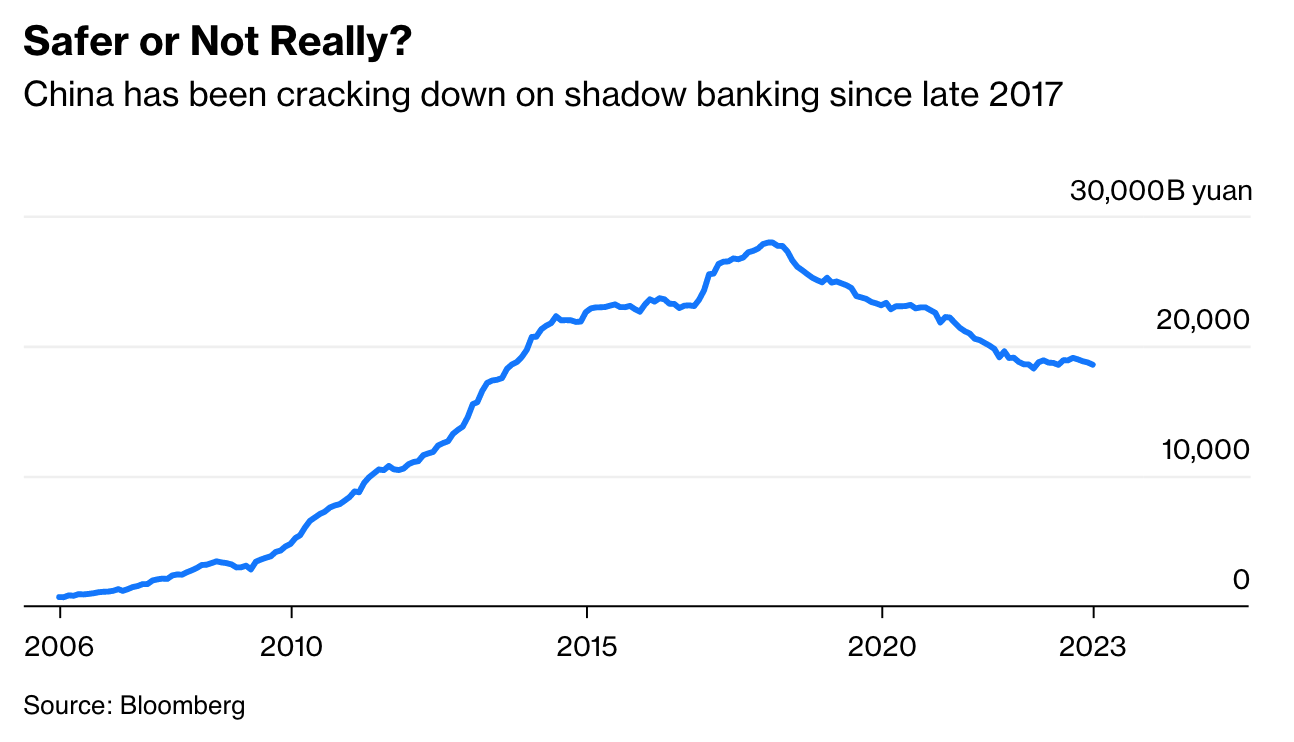

China has been cracking down on shadow banking since late 2017. So people naturally ask why this is happening now, and if we might expect more blowups in the near future.

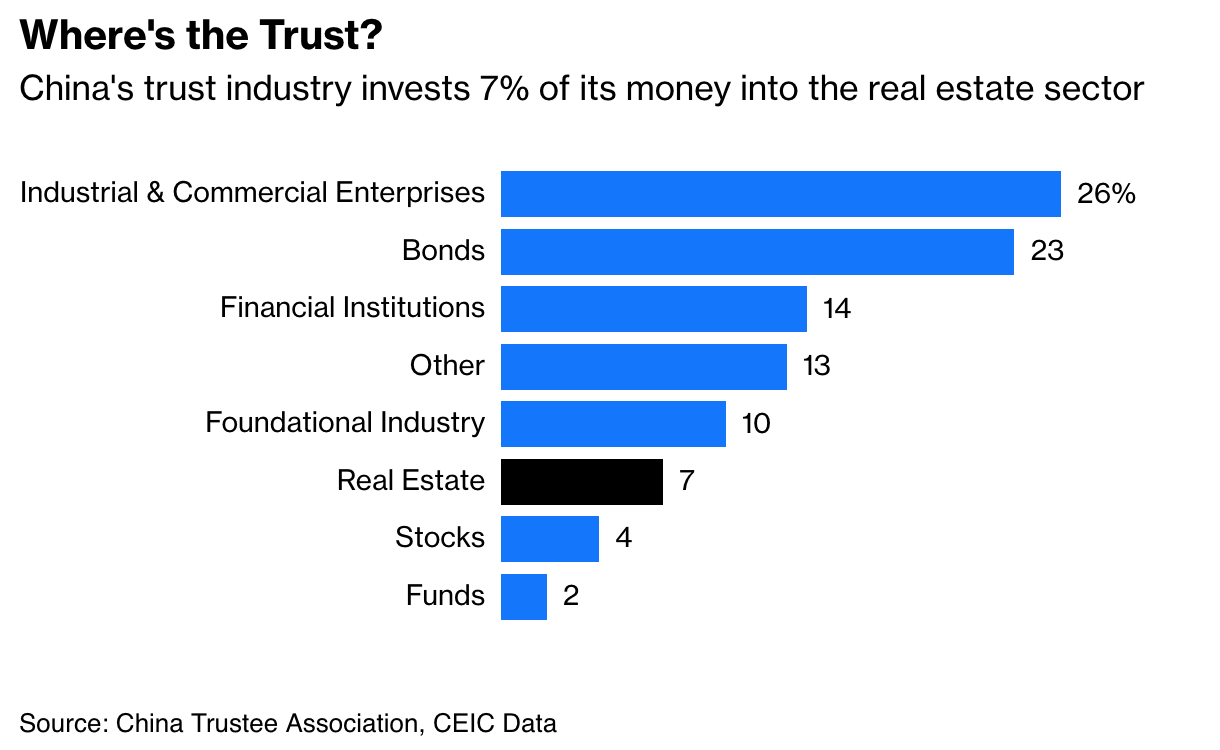

An economic downturn, along with the real estate slump, certainly contributed to Zhongzhi’s woes. Zhongrong International Trust Co., an affiliate with 629 billion yuan under management as of 2022, has more than 10% of its investments in the property sector.

As developers’ financial distress deepens and asset disposals slow to a trickle, a trust product can hit its due date before the residential projects it had funded are completed or sold.

But a deterioration of asset quality is only part of the story. The bigger culprit is the opaque nature of private credit, whereby a non-bank institution lends directly to the real economy.

Often, these products, sold to high-net-worth individuals or company treasuries, are similar to bank loans, but without bankers’ due diligence or standardized covenants.

A lack of ring-fencing appears to be a key cause of Zhongrong’s default. For instance, the 30 million yuan trust product Nacity Property Services had bought was supposed to be similar to a money-market fund, with an expected 5.8% return.

But it turned out to be a so-called “cash pool.” Nacity’s money was put into a common pool, which the trust could use to repay older, existing investors.

By the end of 2021, Zhongzhi’s cash pools, not including that of its trust affiliate Zhongrong, had reached 300 billion yuan.

They were backed by about 150 billion yuan worth of underlying assets, reported financial media outlet Caixin. No surprise then that, when new fundraising dried up, Nacity’s money was not returned at maturity.

The government, of course, frowns upon this practice. A polite description is excessive leverage, while a more crude one is a Ponzi scheme. However, because of their complex nature, regulations covering cash pool products have only been loosely enforced, according to CreditSights.

Officials don’t get to see the lending documents — they are, by definition, private. They don’t have the resources to sift through and understand the tailor-made borrowing terms either.

Caixin cited other eyebrow-raising practices. For instance, a Zhongzhi subsidiary had raised $1 billion against a certain project.

Another subsidiary consolidates the balance sheet of the first one and also borrows $1 billion from the same project.

In other words, an asset is pledged away many times. As an outside investor, how do you conduct this level of detailed due diligence?

Zhongzhi has hired KPMG LLP to conduct an audit of its balance sheet to find out if it has enough assets it can sell to repay investors. Chances are, it’s already reached negative equity.

Most private-credit products are only available to wealthy individuals or corporate treasuries. Zhongzhi’s wealth management offerings had a minimum investment of 3 million yuan, while that of a trust was normally above 300,000 yuan.

However, just because these investors were richer, they were not necessarily savvier. Many simply got lured by the 7% to 9% yield. That’s attractive considering China’s 10-year government bond pays only 2.6%.

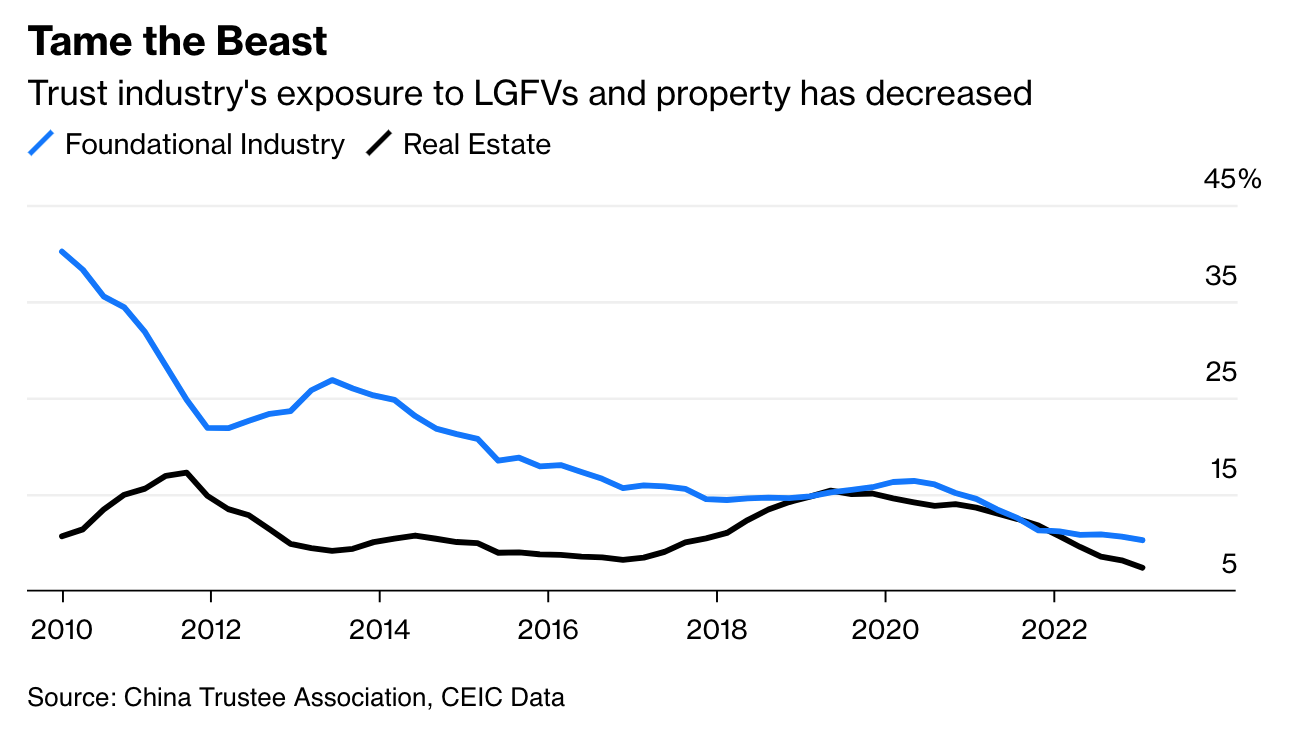

To be sure, after harsh regulatory crackdowns, China’s shadow-banking world has become smaller and safer. The trust industry’s exposure, for instance, to local government financing vehicles and real estate — the two areas where there’s a lot of leverage and financial distress — has diminished.

But as we’ve seen with Zhongzhi, there are still plenty of hidden perils. Private credit is, by nature, opaque, prone to loose lending standards, and difficult to regulate.

Updated: 8-23-2023

SEC Takes On Private Equity, Hedge Funds

Commission votes 3-2 to approve sweeping new rules aimed at increasing transparency, driving down fees.

WASHINGTON—Wall Street’s main regulator approved sweeping new rules aimed at overhauling the way private-equity and hedge funds deal with their investors, in the biggest regulatory challenge in more than a decade to firms such as Blackstone, Apollo Global Management and Citadel.