New York, California, New Jersey, And Alabama Move To Ban ‘Forever Chemicals’ In Firefighting Foam

New York Moves To Ban ‘Forever Chemicals’ In Firefighting Foam. New York, California, New Jersey, And Alabama Move To Ban ‘Forever Chemicals’ In Firefighting Foam

Related:

The Mystery Of The Wasting House-Cats

America Is Wrapped In Miles of Toxic Lead Cables

Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo (D) Dec. 23 gave his conditional approval to the legislation (A.445/S.439), which phases out the use of fluorinated aqueous film-forming foam for fire suppression and prevention. The foam contains per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, PFAS, known as “forever chemicals” for their persistence in the environment.

In a memorandum filed with his approval, Cuomo said that legislators had agreed to amendments to give the state discretion to allow exceptions to the ban for uses where no effective alternative firefighting agent is available.

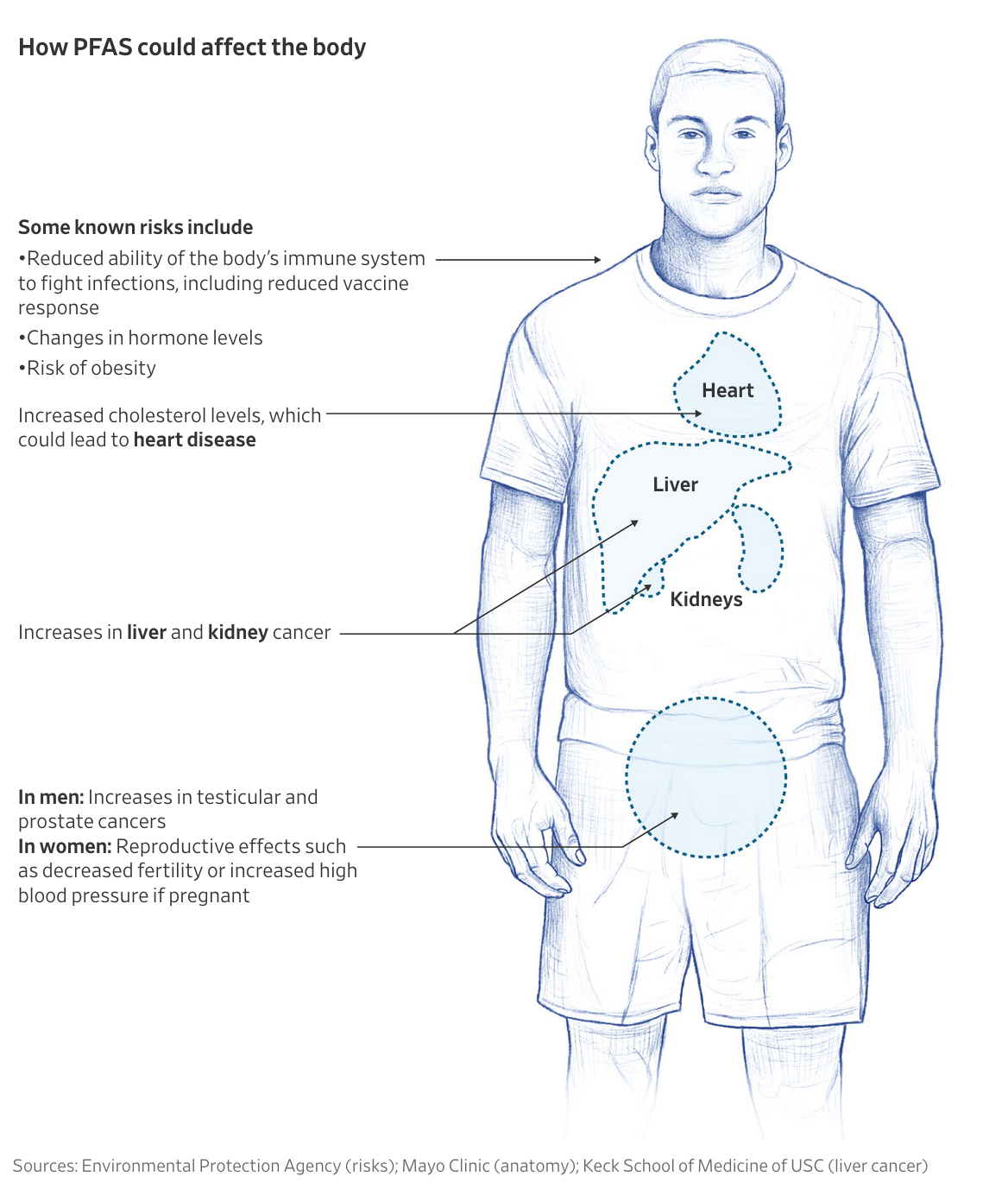

Exposure to PFAS is linked to certain cancers, hormone disruptions, and other medical conditions, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Seepage of the foam into groundwater near military and civilian airfields in New York has been tied to findings of high blood levels of the chemicals in people, bill sponsors said.

“Phasing out PFAS chemicals in firefighting foam will eliminate a major source of water pollution in New York State, resulting in cleaner and healthier drinking water for all residents,” Rob Hayes, clean water associate for Environmental Advocates of New York, said in a statement welcoming Cuomo’s approval.

The broad ban will take effect in two years, with a ban on their use in training exercises kicking in immediately.

Washington, in 2018, became the first state to ban PFAS in firefighting foams, and New Hampshire passed a broad ban in September. Arizona, Colorado, Kentucky, Minnesota, and Virginia passed bans on training use of the foams earlier this year, and Georgia enacted a ban limited to “testing purposes,” according to the advocacy group Safer States.

Updated: 1-13-2020

Forever Litigated ‘Forever Chemicals’: A Guide to PFAS in Courts

Court dockets are ballooning with litigation over PFAS, a vexing family of chemicals used in many consumer and industrial products.

Some types of the man-made per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances are called “forever chemicals,” a shorthand for their ability to build up and stick around indefinitely in people and the environment.

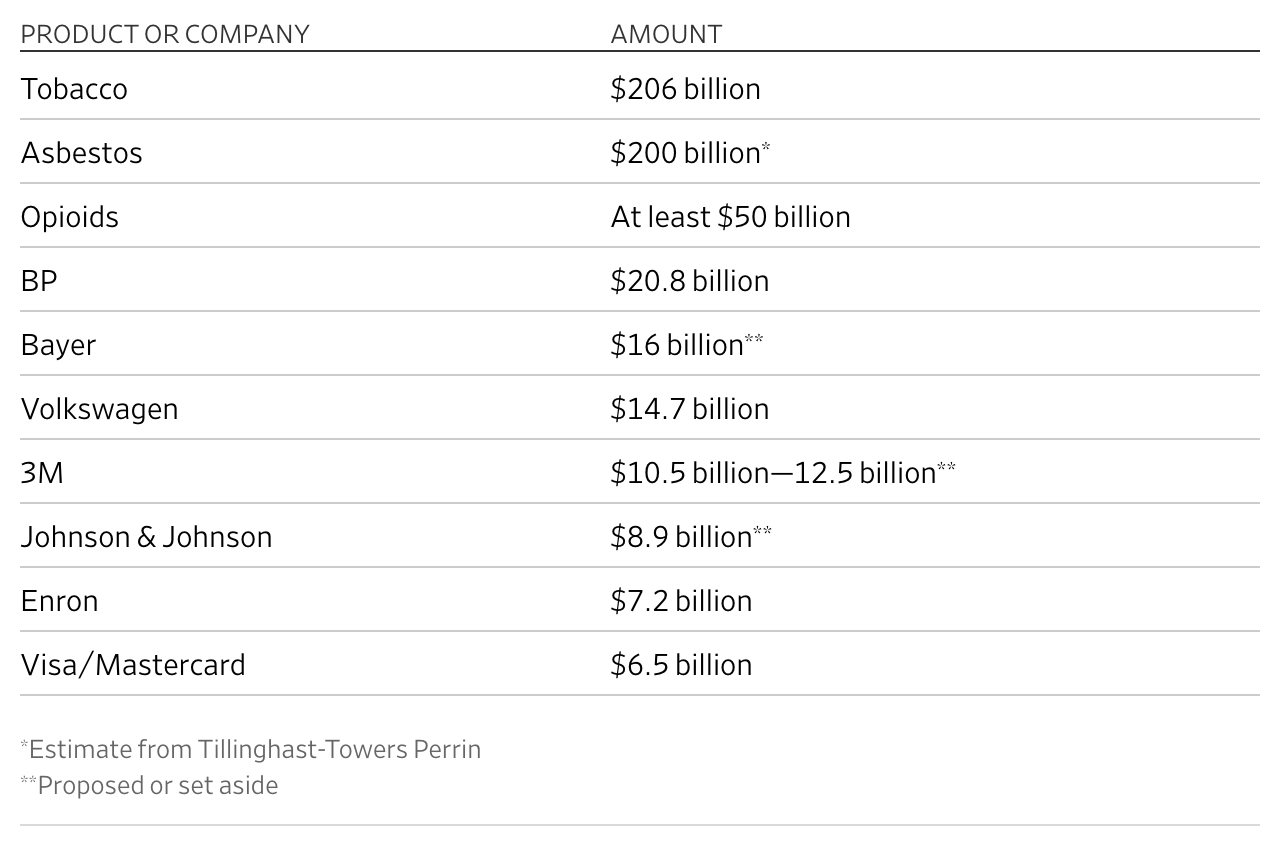

Health risks of some types of PFAS have become clearer in recent years, prompting a rush to the courtroom by people exposed to the chemicals, utilities dealing with contamination, and shareholders facing the financial risks. Lawyers have compared the legal onslaught to litigation over asbestos, tobacco, and lead paint.

Here’s a rundown of key cases.

Multidistrict Litigation

Hundreds of high-stakes PFAS cases are bundled together in multidistrict litigation in Ohio and South Carolina. MDLs are federal court proceedings that roll numerous individual cases into a single docket, allowing a presiding judge to efficiently handle pre-trial motions and other procedural issues.

A judge in South Carolina is handling hundreds of lawsuits against 3M Co., E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co., and other manufacturers over PFAS present in firefighting foam used across the country. The fast-growing docket is in its early stages.

A judge in Ohio, meanwhile, is fielding dozens of lawsuits involving PFAS water contamination near a manufacturing site on the Ohio River. Taft Stettinius & Hollister LLP attorney Rob Bilott, who brought PFAS concerns to light in a related case 20 years ago, is involved in the Ohio MDL.

Class Actions Over Contamination

Other PFAS cases are proceeding as proposed class actions, in which a set of named plaintiffs aim to represent a broader group of people who have experienced the same alleged harms. A judge must approve the class status.

Residents of communities in Vermont, Michigan, North Carolina, and New York have filed class actions targeting companies with local manufacturing sites that made PFAS chemicals or used them in their operations, including 3M, DuPont, Saint-Gobain Performance Plastics Corp., and shoemaker Wolverine World Wide Inc.

In another proposed class action, former Ohio firefighter Kevin Hardwick is pushing the court the recognize a nationwide class of plaintiffs exposed to PFAS and order major manufacturers to fund a scientific panel to study health impacts.

Class Actions Over Securities

Shareholders have filed several cases accusing chemical companies of misleading investors on the extent of PFAS liabilities. The litigants say company executives knew about the financial risks for decades, but only recently disclosed them.

The cases, which allege violations of securities laws, target 3M and DuPont spinoff The Chemours Co.

Corporate Lawsuits

Businesses are also battling one another over PFAS. The most high-profile fight is between DuPont and Chemours. DuPont spun off its performance chemicals business into Chemours in 2015. The young company says DuPont left it holding the bag for PFAS liability.

Other corporate legal skirmishes are playing out between Valero Energy Corp. and chemical manufacturers for alleged PFAS contamination at refineries in Oklahoma and California.

State Actions

Many states have been busy taking legal action to address PFAS.

New York, New Hampshire, Vermont, New Jersey, and Ohio have all filed lawsuits over the past two years targeting chemical companies. Some of the cases address alleged contamination linked to firefighting foam and have been folded into the multidistrict litigation in South Carolina.

New Mexico, meanwhile, is going after the federal government over fouled water at two Air Force bases in the state.

Military Cases

Other cases also center on military operations. Pennsylvania residents are suing the Navy over PFAS in groundwater near two naval sites, and the Air Force is facing litigation over contamination claims from a water utility in Colorado and a farmer in New Mexico.

Other lawsuits against chemical manufacturers involve military sites, and similar litigation is expected to pile up.

Utilities Cases

Water utilities that have found PFAS in their supplies have lined up in court to get 3M, DuPont, and other companies to take responsibility.

Lawsuits are pending from utilities in New York, California, New Jersey, and Alabama.

In New Hampshire, meanwhile, the Plymouth Village Water & Sewer District has teamed up with 3M to sue the state over stricter limits on PFAS in drinking water.

Updated: 10-18-2021

Biden Administration Seeks To Accelerate Cleanup Of Toxic ‘Forever Chemicals’

Concerns mount over health toll of substances used to make everything from cellphones to medical devices.

The Biden administration said it is moving forward on regulations to limit the spread of several toxic chemicals that public-health advocates say are harmful to humans and should become the target of a widespread cleanup effort.

White House officials said Monday that they are working on a proposal to designate some chemicals classified as perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, as hazardous substances under 1980 federal law, a status that could make manufacturers and other distributors of the chemicals liable for cleaning up contaminated sites. PFAS are commonly called “forever chemicals” because they take so long to break down.

The planned hazardous designation for some PFAS chemicals was outlined in a series of proposals that the Biden administration says it is taking to accelerate the cleanup of the toxic chemicals, monitor the country’s drinking water supply and help contaminated communities under a three-year road map.

The toxic family of chemicals has made its way into drinking water and the food supply through a range of sources, including industrial operations, food packaging and firefighting foam. Some chemical manufacturers have agreed to stop using some PFAS chemicals in fast-food wrappers and other packaging.

Public-health groups and environmentalists said they are alarmed by the chemicals for the serious health problems they can cause and their resistance to biodegrading in the environment. The chemicals have been linked to several types of cancer and health problems such as high cholesterol.

The efforts “will help prevent PFAS from being released into the air, drinking systems and food supply, and the actions will expand cleanup efforts to remediate the impacts of these harmful pollutants,” the White House said.

Specifically, EPA officials have restarted the process of designating two most-researched types of PFAS, PFOA and PFOS, as hazardous, which could jump-start the process. They didn’t say when that designation would become final.

EPA officials said they would also propose new regulations next year that would require manufacturers to disclose more information about releases of PFAS chemicals that are allowed in commercial use.

Previous efforts to designate the chemicals as hazardous were met with resistance from the American Chemistry Council, a Washington-based trade association that represents the industry.

In July, after lawmakers in the House of Representatives voted to force EPA officials to make that designation in a bipartisan bill, American Chemistry Council leaders released a statement warning that the designation could limit access to critical products for consumers and businesses, potentially jeopardizing other Biden administration priorities such as greenhouse-gas reduction and semiconductor supply-chain stability. It repeated that concern on Monday.

“According to EPA, approximately 600 PFAS substances are manufactured or in use today, each with its own unique properties and uses, from cellphones to solar panels, for which alternatives are not always available,” the group said in response to the Biden administration’s three-year strategy.

EPA Administrator Michael Regan led a cleanup of widespread PFAS contamination into the Cape Fear River in his home state of North Carolina. Shortly after taking his post, he formed a group to make recommendations on ways to handle the toxic chemicals.

“When EPA becomes aware of a situation where PFAS poses a serious threat to the health of a community, we will not hesitate to take swift action, strong enforcement to address the threat and hold polluters accountable,” he said at a press conference on Monday.

The Biden administration has tasked other agencies with roles in investigating and limiting the spread of the chemicals, including the Department of Health and Human Services, the Department of Homeland Security, the U.S. Agriculture Department, the Food and Drug Administration and the Defense Department.

White House officials met with federal agency leaders on Monday to discuss policy issues on the chemicals under a new committee led by White House Council on Environmental Quality Chairwoman Brenda Mallory.

The Biden administration plans to use existing powers to make regulations and take enforcement approaches to address the chemicals’ contamination.

White House officials are also pressuring Congress to pass legislation to address the chemical contamination, including a $10 billion grant program in the infrastructure bill. Another proposal sets aside money for drinking-water monitoring.

Updated: 6-9-2022

3M’s ‘Forever Chemicals’ Crisis Has Come To Europe

The fight over a tunnel project in Antwerp has revealed extraordinary levels of toxins in the water, soil, and people near the company’s factory. This time there could be criminal charges.

The soil around Wendy D’Hollander’s Belgian farmhouse is so saturated with the chemical PFOS, produced in Antwerp by 3M Co., that she’s in what’s called the red zone.

Belgian officials have ordered 3M to draw up a plan by July 1 to scrape off as much as 5 feet of soil on D’Hollander’s 2.5 acres. More than 4,500 other families face a similar fate, with varying depths of soil to be carted away to a still undetermined location.

D’Hollander knew something was wrong a decade ago. She was working toward a Ph.D. in biology and living with her parents and daughter in the farmhouse. The setting, in the suburb of Zwijndrecht, is bucolic and lovely, save for the 3M plant across a highway.

During her research, she discovered that eggs from birds close to the plant had some of the highest concentrations ever reported of PFOS, an ingredient in fabric coatings and firefighting foams.

Then she tested herself. PFOS—perfluorooctanesulfonic acid—is referred to as a forever chemical, because it accumulates in soil, rivers, and drinking water and is almost impossible to get rid of. She had about 300 micrograms of it per liter in her blood, more than 60 times the level recommended as safe today by the European Union.

At the time, she was pregnant with her second child. She immediately tried to limit her exposure by avoiding locally produced eggs—she thought that might be the key contamination route, because the chemical binds to proteins. In 2012 she wrote to the mayor of Zwijndrecht, warning him that local eggs posed a serious problem. She never got a response.

Life steamed ahead. D’Hollander is now 40 and has three children. Her family has lived on that plot of land since the late 1800s, so she never seriously contemplated moving. Knowledge of the health risks associated with forever chemicals was still evolving, and she didn’t know the extent of the contamination. “I thought it was just those eggs really near the factory,” she says.

Last year she found out her 65-year-old mother had 1,100 micrograms of PFOS per liter of blood—a concentration more typically found in industrial wastewater. Her 68-year-old father had about 800. Her 19-year-old daughter tested at 300.

D’Hollander’s own level had come down to about 100, which she attributes to not eating eggs and to breastfeeding, a theory backed up by studies showing mothers pass on high amounts of the chemical through their milk.

She and her mother both have malfunctioning thyroids, a condition now associated with PFOS, and doctors have told them that at some point the drugs they take for the condition will stop working. Other health problems associated with high PFOS levels include high cholesterol, diabetes, hormone and immune disorders, and even diminished vaccine efficacy.

“I feel a bit guilty now that I didn’t put more pressure on authorities to do something 10 years ago,” says D’Hollander. Now she waits for 3M to begin undoing the damage—not to her family, because that’s done, but to the land.

“I’m not sure how they will deal with some of our trees which are more than 100 years old,” she says. “And I’m not sure how they will compensate us if we are living in a mud pit.”

3M is at the center of a major political scandal in Belgium, where the company produced PFOS from 1976 to 2002. PFOS is one of thousands of types of PFAS—perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances. All the PFAS chemicals produced by 3M and other companies are considered forever chemicals.

It’s possible the contamination wouldn’t have come to light if the government hadn’t pushed ahead with a €4.5 billion ($4.8 billion) project to build a network of roads, tunnels, and parks to finish a ring road around Antwerp.

To complete the construction, the state-owned highway company, Lantis, needs to dig up almost 14 million cubic meters (494.4 million cubic feet) of soil, roughly enough to fill the Great Pyramid of Giza five times over.

The project, known locally as the Oosterweel, is an attempt to unclog the snarl of trucks around the Port of Antwerp in one of the most densely populated corners of Europe. It’s been 20 years in the making, dogged all along the way by opposition.

The most challenging part: a tunnel that will run under the Scheldt River and pop out close to 3M on the left bank. This section of Antwerp is home to Europe’s largest cluster of chemical factories. If there were ever a place not to dig a tunnel, it would be here.

The contamination was exposed last year in the battle over what to do with all that dirt. The result has been a criminal probe into the company, a parliamentary commission that’s hauled ministers in for questioning, and a public outcry over the potential health risks to tens of thousands of local residents.

At the end of October, the government of the Flanders region ordered 3M to shut down production of almost all PFAS chemicals—the first time the company had been forced by a government to stop making PFAS.

Last year details of a secret deal came out. In 2018, 3M struck a confidential agreement allowing the most toxic soil from the Oosterweel project to be dumped on its site, with a plan to create a toxic dirt wall of mind-boggling proportions: almost a mile long, 21 feet high, and at least 82 feet wide.

“The whole thing is crazy,” says Thomas Goorden, an activist who played a key role in revealing 3M’s contamination. “Essentially the government decided to suppress the whole PFOS story here in order to build a tunnel.”

With Goorden’s help, citizens groups and nongovernmental organizations mounted legal challenges that have halted the construction of the tunnel and the toxic wall of dirt, at least for now.

The company has denied that PFOS and other PFAS chemicals cause harm to human health at the levels detected in the environment, arguing that studies have produced conflicting results. Nevertheless, 3M’s costs are spiraling.

In March it announced it would spend an additional €150 million to clean up soil in the red zone where D’Hollander lives and a surrounding area known as the orange zone, bringing the total amount for PFAS remediation measures in Belgium to €275 million, including a new water treatment system.

Rebecca Teeters, 3M’s senior vice president for PFAS stewardship, says the costs are likely to grow. “We’re going to take it back to the state that it was before we had to come in,” she says.

“The criminal case makes this more serious for 3M than what’s happened in the US”

3M has been having a PFAS reckoning. It paid $850 million in 2018 to settle, without admitting wrongdoing, a case in its home state of Minnesota over forever chemicals, and it’s contending with a cascade of lawsuits elsewhere.

What’s happening in Belgium may be the most significant threat, because the company is facing criminal charges of illegally dumping waste. It could end up paying more than $1 billion for compensation and cleanup, says Isabelle Larmuseau, a prominent environmental lawyer based in Ghent, Belgium, who’s not representing anyone in the legal cases under way.

“The criminal case makes this more serious for 3M than what’s happened in the US,” she says. “If convicted, 3M will not only have to face sky-high costs of compensating people and cleaning up the contamination, but prison sentences can be handed out.”

Through a spokesman, 3M denied any criminal behavior. “3M acted responsibly in connection with products containing PFAS and will continue to vigorously defend its record,” the spokesman said.

3M released PFOS into the air in Belgium for at least 20 years. For even longer, it allowed contaminated groundwater to seep into the Scheldt, a 350-kilometer (217-mile) river that starts in France and runs through Belgium and the Netherlands into the North Sea.

Documents disclosed in lawsuits in the US showed that 3M knew for decades about the dangers of exposure to PFAS chemicals but didn’t inform the public. During the 1970s and ’80s, it conducted studies on its US workers that showed PFAS building up in the bloodstream.

In 1977 the company determined PFOS was “more toxic than anticipated” in a study of rats and monkeys; in 1978 a monkey study had to be stopped after all the animals died within the first few days because the PFOS doses were too high.

In 1980, minutes from an internal 3M meeting said workers at the factory in Antwerp were told the chemicals had been found in human blood, but the company decided not to tell the Belgian government.

In 2000 the company announced it would voluntarily phase out PFOS and another forever chemical, PFOA, globally in what it called a “precautionary measure.” But it maintained that the chemicals were safe and worked on developing new-generation PFAS chemicals that could be used for the same products, including Scotchgard, one of its preeminent brands.

A year later, 3M studied the groundwater of its Antwerp factory and found PFOS levels that were off the charts. One sample showed 257,000 micrograms per liter, according to a 3M-commissioned study submitted to the Flemish waste management agency. For context, Minnesota’s current safe limit is 0.015 micrograms per liter.

“I was looking at the numbers and thinking to myself, ‘Did they misplace a decimal point?’”

Goorden, the activist, saw the 3M study in January 2021. “I was looking at the numbers and thinking to myself, ‘Did they misplace a decimal point? There’s a thousand times too much here,’ ” he recalls. “We’re talking about incredible concentrations, thousands of times over the norms.”

After 3M stopped producing PFOS in Belgium in 2002, it replaced the chemical with equivalents it said were safer. (Many scientists disagree.) 3M continued to study the extent of the contamination. In 2006 the company hired a consulting firm called Arcadis NV, which found PFOS levels in the groundwater of as much as 82,800 micrograms per liter.

A 655-page report by Arcadis, seen by Bloomberg Businessweek, stated that the contamination had spread via groundwater and possibly by air to a neighboring nature reserve and a nearby creek. In 2008, Arcadis drew up a groundwater remediation plan, but the waste management agency decided no soil sanitation was needed. By 2015 the agency said no additional remediation was required.

That would turn out to be a terrible mistake. In 2016, Lantis, the company in charge of the ring road project, tested the soil. In one area near 3M’s factory, it measured 1,232 micrograms of PFOS per kilogram of dry soil.

Flanders has never had laws on its books limiting PFAS, but officials knew that one of the norms being used in the neighboring Netherlands was 8 micrograms per kilo of dry soil, according to minutes from a 2016 meeting on the project.

Neither 3M nor Lantis warned the public about the pollution in the area, even as citizens groups battled over how to complete Antwerp’s ring road. Environmentalists rejected a proposed viaduct connection to the tunnel because, they said, it would lead to deforestation.

The government reached an agreement with the activists in 2017 that still included the tunnel plan. Officials didn’t mention anything about digging up heavily contaminated soil.

After more than a decade of fighting, Flemish officials were eager to go ahead with the Oosterweel. They needed 3M’s help. In November 2018, Lantis and 3M signed their secret pact allowing the most dangerous of the toxic dirt (with 70 to 1,000 micrograms of PFOS per kilo) to be dumped on 3M’s site.

Lantis argued Flemish regulations allowed it to move the soil without treating it as toxic waste as long as it served a function, in this case a security wall. Lantis estimated it would cost €63 million to move all that soil. 3M’s cost would be €75,000.

“We were astonished,” Hannes Anaf, chairman of the parliamentary committee investigating the PFOS scandal, says of the 2018 agreement. “If you look at what it’s going to cost to resolve the pollution in the broad surroundings of the company, we’re talking billions.”

Environmental groups and residents won a legal challenge late last year that effectively canceled the approvals for transporting the contaminated soil to 3M’s site. Some had already been moved, however, and in March, Lantis came up with a strategy to cover that soil with gravel to prevent PFAS from being, it said, “carried along by the wind.”

Soil showing more than 47 micrograms of PFOS per kilo would be kept within the zone where it was excavated and covered with a layer of foil and clay.

The parliamentary committee investigating the scandal issued its report at the end of March and concluded that 3M is to blame for the historical PFAS contamination in the area. It accused the company of not communicating openly about the pollution, but it didn’t hold anyone in government accountable, despite ministers approving the project.

Environmental activists made a final move to halt construction of the Oosterweel, saying the work would make the contamination worse and allow 3M to escape its obligation to clean up the area.

In April they won again at the Council of State, Belgium’s top court, which suspended all movement of soil, saying that anything with more than 3 micrograms of PFOS per kilo still posed an unacceptable environmental risk.

What happens now is anyone’s guess. “It’s not the end of the tunnel,” says Annik Dirkx, a Lantis spokesperson. “We are looking at a solution.” Goorden disagrees: “They believe it can indeed still be built, but nobody has told us how they think they can do it legally.”

Teeters, the 3M executive, says she wasn’t involved in the 2018 deal and declined to comment on why it was kept secret. 3M’s focus now, she says, is dealing with the contaminated soil and sharing as much information as possible. “We’re really trying to change that perception of 3M that we’re withholding,” she says. “Our goal is to find a path forward.”

Discovery of the contamination can be traced to a retired pottery designer named Frank Van Houtte, who liked to walk in the nature reserve near his home south of Antwerp.

In 2017 he got wind of an elaborate plan by Antwerp province to chop down almost all the trees in the 135-acre reserve and cover much of the area with about 4 million cubic meters of soil from the Oosterweel. That would have created a mountain of soil nearly a hundred feet high.

This plan, too, involved foil, with the goal of containing what Lantis said was preexisting pollution in the reserve. “They explained it as if the whole thing would be packed like a piece of chocolate, that it would be safer because nothing can get in or out,” Van Houtte says.

Soil Dump

The Province of Antwerp planned to move roughly 4 million cubic meters of soil from the tunnel-highway project to a nature reserve far south.

He recounts how authorities promised the plan would protect the ecosystem. “They said they would catch the salamanders in the pond and the bats from the trees to send them somewhere else before they cut the trees down,” he says. “But you cannot catch them all! It’s impossible!”

Van Houtte started asking for details on the soil Lantis was going to dump on the nature reserve. In 2020 he got reports from the Flemish waste agency showing about 40 contaminated areas where the Oosterweel would be built.

Needing help to go through the documents, he gave them to Goorden. The activist combed through them and wrote up a report that he handed to Antwerp’s daily De Standaard, which ran a story in April 2021 revealing the PFOS contamination around 3M.

Goorden also advised the municipality of Zwijndrecht to test the soil independently of the Flemish government. In June 2021 the city announced the results, showing that PFOS contamination within half a kilometer of the factory exceeded standards by as much as 26 times.

“That’s when we knew we had a major problem,” says Steven Vervaet, a local alderman. The municipality then filed a criminal complaint against 3M. He recalls asking company executives in January 2020 if it was risky to use groundwater for agriculture. “They actually told me there is no human risk and certainly not with concentrations found in the area,” he recalls.

“I wondered how I could ever sell this product again now that Zwijndrecht has become PFOS land, like it’s Chernobyl”

Alongside health anxieties, farmers in the area have lost business. Koen Doggen grows organic vegetables that he sells to consumers through a subscription service. He says tests last summer showed his soil had more than twice the level of PFOS at which the government says sanitization is required. “I considered quitting,” he says.

“I didn’t know if I wanted to work on contaminated soil. I breathe it in daily in the summer and wash it off my skin every evening. I wondered how I could ever sell this product again now that Zwijndrecht has become PFOS land, like it’s Chernobyl.”

Surprisingly, his vegetables had no detectable PFOS, though they had traces of other PFAS. Many customers stuck by him. Still, organic farming on chemically tainted soil is a hard sell, especially given that more information about the contamination has come out since the end of Doggen’s growing season last fall.

3M has earmarked €5 million to compensate farmers financially damaged by the contamination. In a deal the government negotiated for farmers, the company paid Doggen in May for losses in 2021 and an expected downturn in revenue this year. He declined to disclose how much he received.

Lantis now says the soil that will go to the nature reserve south of Antwerp will come only from the right bank of the Scheldt and will not be contaminated with more than 3 micrograms of PFOS per kilo. “The pollution is most of the time limited to the upper layers,” says Lantis’s Dirkx. “There is absolutely no problem with deeper layers.” Van Houtte and many others remain unconvinced.

Flemish inspectors started cracking down last summer. At the end of August the government ordered 3M to stop discharging new types of PFAS, namely PFBSA and two related substances used to make fabrics stain- and water-resistant, into the Scheldt via wastewater.

High concentrations of PFBSA had made it into fish in the estuary of the western side of the Scheldt leading into the North Sea, according to a study paid for by residents of Zwijndrecht late last year. Flounder in the estuary had 24 micrograms of PFOS, seven times above safe limits for people who eat fish once a week.

The negative reports kept coming. A study by two state agencies found the air around 3M was polluted with PFOS, saying it wasn’t clear if construction dust or 3M was the culprit. At the end of October the government ordered 3M to shut down production of almost all PFAS chemicals.

“In 30-plus years of practicing environmental law, I’ve never seen that happen,” says Esther Berezofsky, a lawyer at the US firm Motley Rice who’s advising the Flemish government in its proceedings against 3M.

The company fought the order and lost. Last autumn, 3M’s chief medical officer, Oyebode Taiwo, flew to Antwerp from the US to defend the company in Parliament. He argued that blood tests showing high PFOS levels weren’t proof the chemical caused the health problems that individuals were experiencing.

“It could be due to reverse causation, meaning that it’s not the exposure that is causing the health outcome, but it is the health outcome that is causing the exposure to build up,” he said.

In other words, he argued certain people with specific health conditions are more prone to build up PFAS chemicals in their blood. Scientifically, the idea is dubious. Legally, it’s absurd, says Berezofsky. She points to the “eggshell skull” rule accepted in US law.

“If I walk down the street and I hit somebody over the head, a normal person with a normal skull may just feel a bump. Somebody who has a skull made of an eggshell might die,” she says. “I’m still responsible. The fact that they have an eggshell skull does not relieve me of the liability of what I did.”

Recently the government has started testing as many as 40,000 people living within a 5-kilometer radius of the factory in what could be one of the world’s biggest human studies of forever chemicals.

Residents of central Antwerp just across the river won’t be included even though some live within five kilometers, but a local citizens group crowdfunded to do its own tests on an additional 30 people, including some in central Antwerp. In May it found half that group had PFAS levels in their blood above the European safety levels.

3M says it expects to restart PFAS production in Belgium later this summer. “Will it ever be to the extent and scale as it was over a year ago? Likely not,” Teeters says. After this story came out, 3M issued a statement saying it had “received approval to begin the process toward restarting its manufacturing operations.”

A spokesperson for the Flemish Environment Ministry said it was only a partial restart of a “couple of their processes” but the majority remains closed. Karl Vrancken, the Flemish PFAS commissioner who has been coordinating among agencies to respond to the contamination, says Belgium remains committed to supporting a proposal by a handful of European countries for an EU ban on all PFAS chemicals.

Updated: 8-26-2022

EPA Proposes To Designate Two ‘Forever Chemicals’ As Hazardous, Aiming To Bolster Clean Up

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is proposing to designate two types of “forever chemicals” as hazardous substances, aiming to expand both cleanup and accountability for this pollution.

“Forever chemicals,” also called PFAS, have been linked to illnesses including kidney and testicular cancer and thyroid disease.

They’re also notorious for lingering for decades in the environment and human body instead of breaking down over time.

PFAS contamination has become widespread across the U.S. as it has been discharged over the years by both industrial facilities and military bases, the latter of which used it in firefighting foam.

The compounds can be found in a number of household products including nonstick pans, cosmetics and waterproof apparel.

The new proposal from the Biden administration seeks to help impacted communities clean up this waste. If it’s finalized, declaring these substances as “hazardous” under the Superfund law is expected to both speed up the cleanup process and hold polluters responsible.

Melanie Benesh, Vice President for Government Affairs at the Environmental Working Group, said that the proposal would “jumpstart the cleanup process at a lot of contaminated sites and help the EPA hold polluters accountable for the mess that they have been making over decades.”

The hazardous substance designation would allow the EPA to put either the military or private company that contaminated a given area with these substances on the hook to clean it up, and, if they refuse to do so, would give the EPA the power to recoup the costs.

“Both private parties and [the] Department of Defense will really be incentivized to move out on cleanup when they’re responsible for this now that this designation is going to take place,” said Betsy Southerland, former director of the Office of Science and Technology in the EPA’s Office of Water.

“The whole idea behind a hazardous substance is that it can pose imminent and substantial endangerment so you really have to move out on it. And if you don’t, if you refuse to, EPA can do it and then sock you with a really big clean up bill,” she added.

The designation would also require the reporting of releases of the substances, which is expected to give communities information on where these chemicals are being discharged.

While there are thousands of types of PFAS — an acronym that refers to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances — the EPA’s proposal only addresses the two most notorious types, called PFOA and PFOS.

Recently, the agency said that these two substances are dangerous to drink, even in miniscule amounts.

A chemical industry trade group pushed back on the EPA’s latest proposal, arguing that it would impose significant costs on businesses.

“The lack of uniform cleanup standards creates substantial uncertainty….affecting federal, state and municipal governments, and other parties such as local fire departments, water utilities, small businesses, airports and farmers,” the American Chemistry Council said in a statement to The Hill.

“A proposed [hazardous substance] designation would impose tremendous costs on these parties without defined cleanup standards, making it impossible for these entities to prepare for the impact of this rule,” the organization said.

The American Chemistry Council also said that the Biden administration’s recent finding that PFOA and PFOS are unsafe at “near-zero” levels further complicates the issue.

It said that taken together, these actions could “lead to an expectation that all contamination be cleaned up to non-detectable levels of the substances.”

The Trump administration previously considered designating these two types of PFAS as hazardous, but did not actually propose a rule to do so.

Meanwhile, the Biden administration is also expected to set enforceable drinking water limits for the substances, but has not proposed these limits yet.

Updated: 9-2-2022

Eradicating The ‘Forever’ From ‘Forever Chemicals’

A promising new development may accelerate efforts to break down damaging molecules that linger for many years in soil, water and our bodies.

You might not have heard of “forever chemicals,” but you’ve certainly been exposed to them. This large family of molecules can be found in everything from the wrapper on your take-out burger to the stain-resistant fabric on your couch.

You might unwittingly encounter them when you floss your teeth, apply your mascara, or fry an egg in your nonstick pan.

Known to scientists as PFAS (shorthand for perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances), these pervasive chemicals can linger for many years in soil and water — and in our bodies, where they have been linked to a range of diseases.

They’ve been found in the drinking water in many parts of the US, particularly areas near chemical plants that currently or previously made them. So much of this stuff is out there that researchers recently detected unsafe levels in rainwater.

Now, there might be a way to strike the “forever” from those chemicals. Scientists at Northwestern University have come up with a simple and cheap method of breaking down some of these molecules into benign parts.

That feat, and, more realistically, others it might inspire, has the potential to play a critical role in the massive and costly effort to eradicate these chemicals from the environment.

The discovery is far from an immediate solution to the world’s PFAS problem. But it arrives at a time when the US is starting to put real money into efforts to pull these contaminants out of the water supply, which would create a lot of PFAS waste with nowhere good to go.

Forever chemicals exist to add durability during manufacturing and enable consumer-friendly features like water- and grease-resistance.

The problem is that the carbon-fluorine bonds that endow these qualities also make these chemicals annoyingly stable. Getting rid of them is a massive and expensive headache.

One community in North Carolina spent some $50 million to upgrade its water treatment plant to filter out PFAS each year and is on the hook for several million more dollars to change the filter and get rid of the chemicals it captured.

Northwestern professor William Dichtel is one of many scientists working on methods to pull these chemicals out of water. But a question has always lingered, he said. “What do you do with the PFAS after you’ve removed them from contaminated water?”

Prying apart those carbon-fluorine bonds currently requires brute force — think energy-intensive measures like incineration at extreme temperatures. And even that doesn’t always break everything down.

The team from Northwestern team struck upon a simple alternative. Certain types of PFAS (ones featuring carboxylic acids) can be dissolved in mild conditions using just water, a widely used solvent called DMSO, and sodium hydroxide. What’s left in the end is benign.

The lab also partnered with scientists at other universities to do a deep dive into how these chemicals fall apart. Those details may not seem as exciting as an easy recipe for PFAS destruction but are just as important in that they help inform future research.

Such efforts will be needed. The Northwestern team’s findings have not been proven on an industrial scale. DMSO, for example, is not typically used at an industrial scale. The reaction also only works on some kinds of PFAS, so other approaches need to be explored.

Progress in addressing those questions is urgently needed. A lot of forever chemicals could soon be pulled out of our water.

The Biden administration’s infrastructure bill included $1 billion to address PFAS contamination as part of an overall $5 billion commitment, with a particular focus on aiding remediation efforts in small or disadvantaged communities.

As part of the plan, the Environmental Protection Agency proposed lowering the acceptable level in drinking water to practically zero for two older chemicals (PFOA and PFOS), and issued a health advisory for two others.

Last week, the agency proposed adding PFOA and PFOS to its list of hazardous substances, a move that could put some of the clean-up cost back on the chemical companies.

Companies keep churning out forever chemicals, and consumers keep buying products made more convenient because of them.

Unfortunately, that cycle doesn’t seem to be changing any time soon. And although the Northwestern team’s discovery won’t fix the world’s PFAS problems anytime soon, it could help with the clean-up and inspire other inventions that bring safer drinking water closer to reality.

Updated: 12-20-2022

3M To Stop Making, Discontinue Use of ‘Forever Chemicals’

Company says it has already reduced its use of PFAS, which accumulate and take a long time to break down.

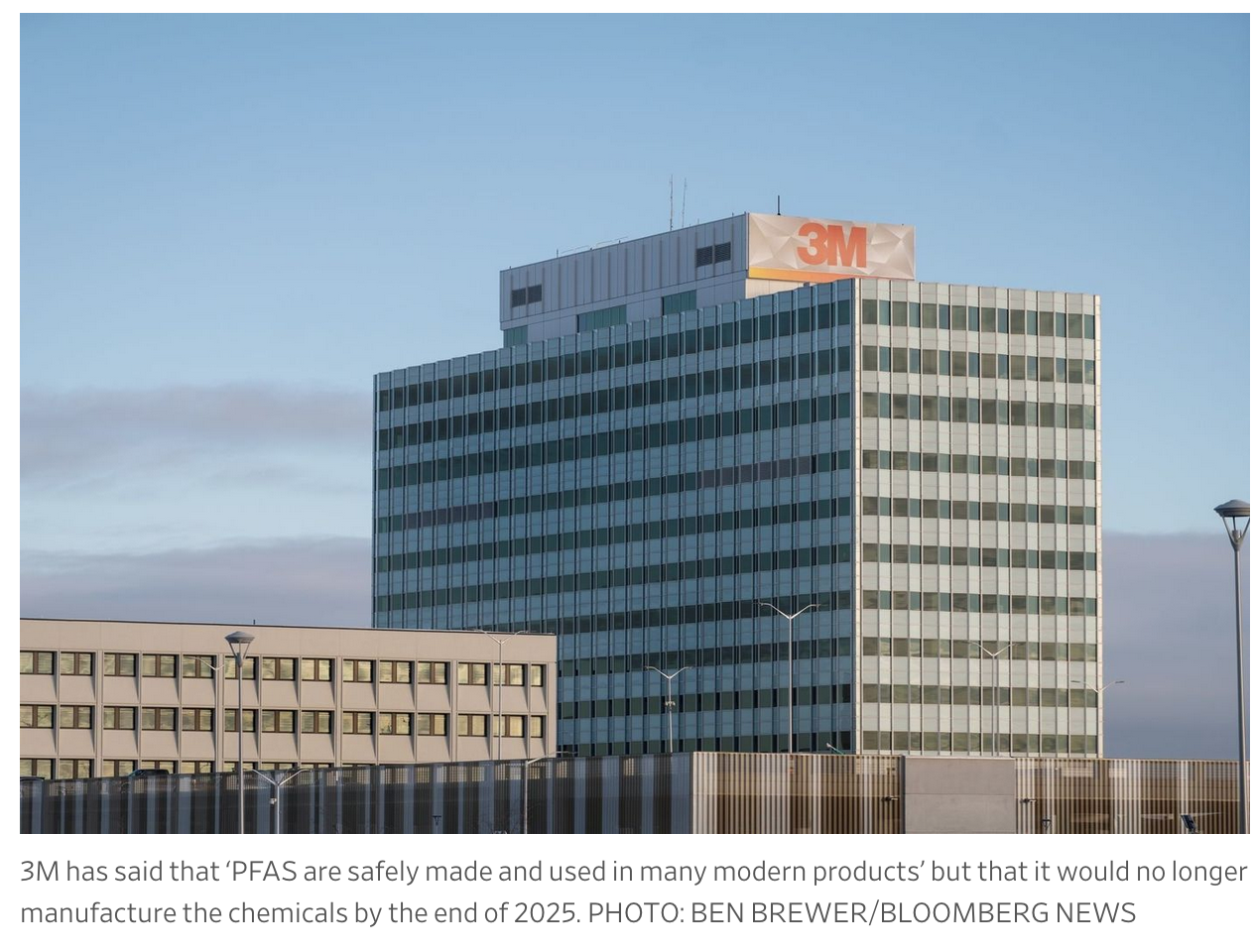

3M Co. said it would stop making so-called forever chemicals and cease using them by the end of 2025, as criticism and litigation grow over the chemicals’ alleged health and environmental impact.

3M Chief Executive Mike Roman said that the decision was influenced by increasing regulation of the chemicals known as PFAS, and a growing market for substitute options.

“Customers are taking note of PFAS regulations. They’re looking for alternatives,” Mr. Roman said in an interview. “We’re finding other solutions that have the same properties,” he said.

The company’s move involves chemicals used to make nonstick cookware, food packaging and other consumer and industrial products. 3M estimated its current annual sales of the chemicals total about $1.3 billion.

Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, are commonly called “forever chemicals” because they take a long time to break down in the environment.

Such chemicals include highly durable compounds long prized by manufacturers for their resistance to heat, and their ability to repel water, grease and stains.

In recent decades, research has linked exposure to some forms of the chemicals with health problems including kidney and testicular cancers, thyroid disease and high cholesterol, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

The synthetic compounds have also been found in drinking water, including some municipal systems and private wells, as well as in rainwater around the world.

Regulators and environmental groups have taken aim at the chemicals, and thousands of lawsuits alleging contamination and illness have been filed in recent years targeting 3M and other manufacturers.

3M stopped producing some types of PFAS chemicals in the early 2000s but has continued to make other types, which the company has said can be safely produced and used.

3M said Tuesday it would stop making all fluoropolymers, fluorinated fluids and PFAS-based additive products by the end of 2025.

The company also said it would stop using PFAS across its products by the end of 2025, saying that it has already reduced its use of the substances over the past three years.

3M’s shares closed about 1.1% lower Tuesday, while major U.S. stock indexes increased slightly. The company’s stock has fallen about 32% so far this year, compared with a 20% decline in the S&P 500 stock index.

The EPA has said there are roughly 600 PFAS chemicals in commercial use today. The American Chemistry Council, which represents chemical makers, said Tuesday that PFAS are integral to thousands of products in technologies including semiconductors, batteries for electric vehicles and 5G technology.

The group said its members are dedicated to the responsible production, use, management and disposal of PFAS chemistries, and that it would continue to work with the EPA toward policies that protect human health and allow the chemicals to continue to be used.

3M’s exit from PFAS was seen as a victory by environmental groups that for years have raised alarms over the chemicals.

Scott Faber, senior vice president of government affairs at the Environmental Working Group, said he didn’t think 3M will ever be held fully accountable for producing the chemicals.

“But by exiting the market they have sent a powerful signal to the other polluters that it’s simply unaffordable to poison all of us,” Mr. Faber said.

3M’s net sales of PFAS chemicals represent about 4% of the company’s total annual sales, according to research by RBC Capital Markets.

“This is a step in the right direction for 3M given all the regulatory scrutiny of PFAS chemicals,” RBC analysts wrote in a note to investors Tuesday.

Over the course of exiting the business of manufacturing the chemicals, 3M said it expects to incur pretax charges of about $1.3 billion to $2.3 billion, including a $700 million to $1 billion charge in the current quarter.

The St. Paul, Minn.-based manufacturer said it intends to fulfill current contractual obligations during the transition period.

The EPA in August proposed designating two forms of PFAS chemicals as hazardous substances under the federal superfund law.

The American Chemistry Council and companies such as 3M opposed the move, saying that it wasn’t based on the best available science and that it wouldn’t speed up remediation of contaminated sites.

Industry analysts said plant cleanup costs are likely to increase as the EPA uses broad discretion to impose cleanup terms under the Superfund designation.

They said the hazardous substance designation also likely would hinder sales growth for the PFAS chemicals that 3M continues to produce, as customers look for alternatives.

3M pioneered the development of PFAS chemicals in the late 1940s, building on atomic research that used fluorine gas. By bonding fluorine with carbon, 3M found it could create durable compounds that could be adapted for use in consumer and industrial products.

3M’s plants where PFAS chemicals are produced have come under increasing regulatory focus for soil and water contamination.

3M has committed billions of dollars to clean up plant sites in recent years, including an $850 million settlement with the state of Minnesota related to a plant in Cottage Grove, Minn.

The company also agreed earlier this year to provide about $600 million to remediate contamination connected to a plant in Belgium where PFAS chemicals have been produced.

3M also produces PFAS chemicals at plants in Alabama, Illinois and Germany.

3M phased out production of two PFAS chemicals, known as PFOA and PFOS, in the early 2000s. Those two forms of PFAS chemicals have been at the center of thousands of lawsuits targeting 3M and other manufacturers.

Updated: 12-21-2022

3M, DuPont, Other Makers Expected To Face New Drinking Water Rules On ‘Forever Chemicals’

Many lawsuits involve the effects of firefighting foam that contained the chemicals.

New federal drinking water standards could ratchet up legal pressure on 3M Co., DuPont and other companies that manufactured or used so-called forever chemicals.

The Environmental Protection Agency has been stepping up scrutiny of chemicals known as perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS.

The agency has said it is planning to propose the first federal drinking water limits on them in the coming months, a move some legal experts say could prompt additional lawsuits against PFAS manufacturers.

Research has linked exposure to some forms of the chemicals with health problems including kidney and testicular cancers, thyroid disease and high cholesterol, according to the EPA. Drinking water containing the chemicals is one way people can potentially be exposed to them, the agency has said.

The federal government has been tightening regulation of the chemicals, and thousands of lawsuits alleging contamination and illness have been filed over the years against 3M, DuPont and other companies that used the chemicals, including paper mills and textile manufacturers.

On Tuesday, 3M said it would stop making PFAS and work to discontinue their use in the company’s products by the end of 2025. 3M Chief Executive Mike Roman said in an interview Tuesday that the decision to eliminate the chemicals was influenced by increasing regulation and a growing market for alternatives.

Most PFAS-related litigation has focused on two chemicals known as PFOA and PFOS that were widely used for decades in products from nonstick cookware to waterproof clothing to firefighting foam.

3M stopped making the two chemicals in the early 2000s, while DuPont and other companies phased them out by 2015 under a voluntary EPA program.

Lawsuits involving firefighting foam that contained those two PFAS chemicals represent a big chunk of the current estimated legal liability for 3M, DuPont and other companies that sold the foam.

According to plaintiffs’ lawyers, the chemicals contaminated drinking water supplies near military sites, airports and training facilities where the foam was used for years.

3M said the firefighting foam helped save service members and civilian lives, and that it produced the foam to the military’s specifications, qualifying the company for legal protection from liability as a government contractor.

DuPont said in a written statement: “We believe these complaints are without merit, and we look forward to vigorously defending our record of safety, health and environmental stewardship.”

The number of lawsuits involving firefighting foam has grown to more than 3,000 from around 75 in 2018. More than 200 public water systems, 14 states and cities such as Philadelphia, Baltimore and San Diego have sued the companies over alleged contamination.

The cases are grouped together in federal district court in South Carolina and include claims by firefighters who alleged that repeated exposure to PFAS caused cancer and other illnesses.

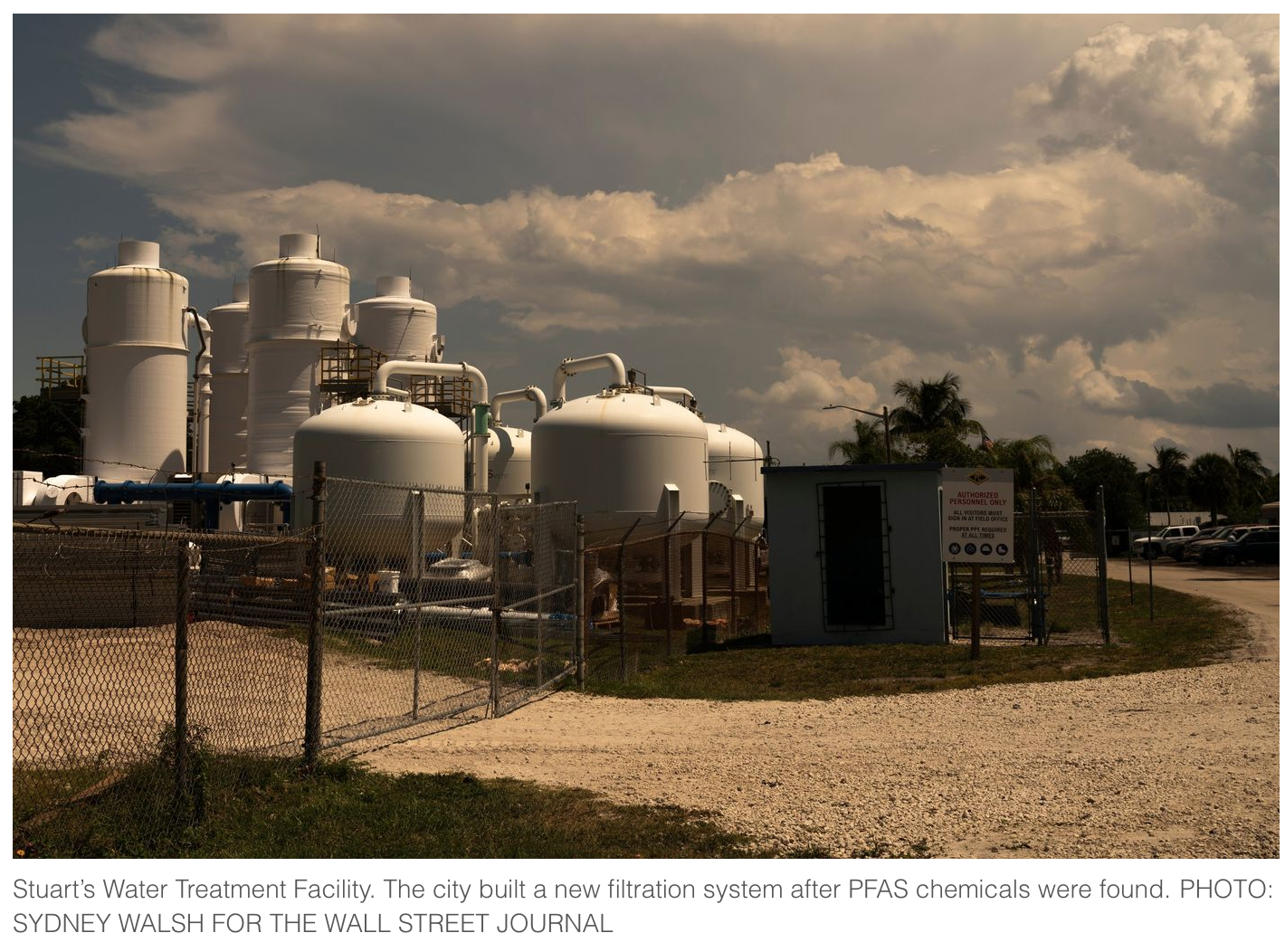

The EPA’s planned drinking water standards, if completed, could require thousands of public water systems found containing the chemicals to install additional filtration systems to comply with the new limits, according to an analysis by the American Water Works Association.

That is likely to expand the number of lawsuits against the manufacturers, said some legal experts.

“If you’ve been drinking levels of PFAS that are above the standard, that’s an obvious catalyst for litigation,” said Gianna Kinsman, a vice president for Capstone LLC, a Washington-based firm that advises investors and companies on regulatory issues. The company said it isn’t advising any PFAS manufacturers.

Delaware-based DuPont declined to comment on the possible effects of the EPA water regulation on PFAS litigation.

3M said that a very low threshold for contamination in water would place a heavy burden on communities and companies.

“We have and continue to support federal regulations of PFAS based on the best available science,” a spokesman for 3M said.

The first bellwether trial in the firefighting-foam litigation, over a claim brought by the city of Stuart, Fla., against 3M, DuPont and other makers of firefighting foam, is scheduled to begin in June.

Stuart, a city of roughly 20,000 on the Atlantic Coast, alleges that its municipal wells were contaminated with PFAS during fire-training exercises that took place over many years.

The lawsuits claim manufacturers knew that PFAS were harmful and accumulating in people and the environment, but didn’t alert the EPA for years.

The companies are contesting the claims. 3M said it has agreed to remediate PFOA and PFOS, two forms of PFAS that the company has discontinued, at certain locations where 3M manufactured or disposed of these materials.

The American Chemistry Council, a trade group representing chemical makers, has said it supports a drinking water standard for PFAS based on the best available science, but said the chemicals have diverse properties and shouldn’t be regulated as a class.

The chemicals in use today are essential in products such as cellphones and semiconductors, the group said, and are thoroughly reviewed by regulators.

The group has disputed some of the EPA’s conclusions about the health effects of PFOA and PFOS, including a link between PFOA and kidney cancer.

3M’s liability from PFAS litigation could reach nearly $30 billion by the end of the decade, according to Capstone. The group estimates that more than half of that could be paid to cover claims over firefighting foam.

DuPont has an agreement to share PFAS liability costs with Chemours Co. and Corteva Inc., two companies spun off from DuPont’s predecessor businesses during the past decade. The agreement is set to last until 2040 or up to $4 billion.

Chemours, which now operates DuPont’s legacy chemicals business, declined to comment, citing pending litigation.

The combined liability for DuPont, Chemours and Corteva is estimated at $14 billion, according to Capstone’s calculations.

The chemicals can be removed from drinking water with filtration systems, but lawyers for the plaintiffs said those systems will be expensive, and on a national basis are likely to surpass damages awarded in the litigation.

Matt Pawa, a lawyer representing Vermont, one of the states suing over firefighting foam, said: “The public is going to have to bear the cost of this.”

Updated: 12-23-2022

The Toxic Legacy of 3M’s ‘Forever Chemicals’

The fight over a tunnel project in Belgium has revealed extraordinary levels of toxins in the water, soil and people near the US company’s factory.

The fight over a tunnel project in Antwerp, Belgium has revealed extraordinary levels of toxins in the water, soil and people near 3M’s factory.

While the company said this week that it will cease using or making so-called forever chemicals a few years from now, for people living near the plant, the damage has already been done. And for regulators in Europe, the battle may be just beginning.

In this episode of Bloomberg Storylines, we meet Wendy D’Hollander, who lives across the highway from the Antwerp plant. She said her entire family has high levels of 3M chemicals in their bloodstreams, and that the American company has yet to begin a promised cleanup near their home.

Updated: 1-3-2023

3M Tries To Contain Legal Battles Over ‘Forever Chemicals,’ Earplugs

Manufacturer aims to blunt impact of liability claims with settlement deals and legal maneuvers.

3M Co.’s decision to quit making “forever chemicals” represents a tactical retreat aimed at containing its potential liability over its products in legal fights expected to last for years, analysts say.

3M is defending itself against allegations that chemicals and products it has made for decades have contaminated drinking water and pose health risks.

Legal and industry analysts expect 3M to be engaged for years in remediating alleged soil and water contamination from forever chemicals, which have been used in industrial and consumer products including nonstick cookware, carpeting and firefighting foam.

The Minnesota-based company also is a defendant in liability lawsuits for earplugs manufactured for the military. Claims filed by about 230,000 veterans—a record number of claims in a single federal court case—allege that the earplugs failed to protect them from service-related hearing loss.

3M is contesting the claims. In coming trials over the chemicals’ use in fire-suppression foam, the company is expected to argue that the foam was produced to U.S. military specifications, providing 3M legal protection as a government contractor.

3M has said the earplugs are safe and effective when soldiers get the proper training on how to use them.

Some analysts project the company’s liability costs will reach tens of billions of dollars. 3M lawyers and executives have said they expect the ultimate costs will be much less, forecasting last summer that the earplug cases alone could be settled for $1 billion.

3M CEO Mike Roman has been trying to boost profits from 3M’s slow-growing portfolio of businesses by selling weak performers.

Mr. Roman, who took over leadership of the 120-year-old company in 2018, also is planning to spin off the company’s healthcare business by the end of 2023, giving 3M investors shares in a separate company with some of 3M’s best-performing product lines.

Analysts said investors’ anxiety about the litigation is reflected in 3M’s stock price, which has fallen 32.5% since the beginning of 2022, compared with a 20% decline in the S&P 500 index. The company’s challenges can weigh on the broader equities market because 3M’s stock is a component of the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

3M is expected to use a series of legal moves to lessen its exposure to liability mixed with negotiated settlements with plaintiffs that, over time, could reduce or spread out its liability costs to manageable amounts, legal analysts said.

“3M will continue to remediate the chemicals and address litigation by defending ourselves in court or through negotiated resolutions,” a company spokesman said.

Analysts said 3M would try to minimize the impact of the litigation costs on the large shareholder dividends that the company is known for on Wall Street.

3M’s efforts to shield itself from liability in the earplugs litigation have hit setbacks. In July, Aearo Technologies LLC, the military-earplug developer that 3M acquired in 2008, filed for bankruptcy protection, citing the litigation.

Aearo’s move attempted to shift earplug-related injury claims against Aearo and 3M to bankruptcy court, where Aearo would attempt to broker a settlement deal that 3M has pledged to pay.

In August, a federal bankruptcy judge in Indianapolis refused to extend to 3M the same bankruptcy-court protection that Aearo received against the pending earplug-injury lawsuits.

The ruling effectively allowed the complaints in federal district court in Florida to continue against 3M without Aearo. Aearo, which is appealing the decision, continues to pursue a settlement deal with the claimants.

Since Aearo’s bankruptcy filing, 3M lawyers in the Florida federal court litigation argued that liability for the alleged injuries from the earplugs should be split between Aearo and 3M.

The judge presiding over the Florida cases rebuked 3M’s arguments in a Dec. 22 ruling, saying 3M assumed responsibility for the product after acquiring Aearo and had previously made no attempt to separate liability. The judge ruled that proceedings in the cases be put on hold, pending an expected appeal of her decision

Liability claims related to chemicals called perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, are still growing for 3M. Commonly called “forever chemicals” because they take a long time to break down in the environment, the chemicals have highly durable compounds that can resist heat and repel water, grease and stains.

Research has linked exposure to some forms of the chemicals with health problems ranging from kidney and testicular cancers to thyroid disease, the Environmental Protection Agency has said.

Some analysts have predicted that eradicating PFAS chemicals could rival the efforts waged a generation ago to rid buildings and construction materials of asbestos.

Some cautioned that any health impacts from using products with PFAS aren’t as conclusive as with asbestos, which is widely understood to cause a specific type of cancer after prolonged exposure.

“Forever chemicals last a long time, but they’re chemically inert,” said Mark Gulley, who heads a chemical industry consulting firm. “Scientists have to be able to define why they’re a problem.”

About 20 years ago, 3M quit making two varieties of PFAS chemicals that are often linked to health concerns.

Before 3M discontinued production of the two chemicals, it sold them to other companies for use in their products, potentially exposing 3M to litigation and cleanup expenses incurred by other companies, analysts have said.

While the company continued to make other varieties of PFAS chemicals that 3M has said are safe, the company said Dec. 20 that it would wind down its production of those chemicals by the end of 2025, citing increasing regulation and customers’ interest in alternatives.

Ceasing production of the chemicals will limit 3M’s exposure to liability to the chemicals that already exist, analysts said. Profit margins on the chemicals have been declining for 3M as regulations have tightened, UBS Securities wrote in a note to investors.

3M estimated its current annual sales of PFAS chemicals at about $1.3 billion, or about 4% of total sales, according to analyst estimates. Nigel Coe, an analyst for Wolfe Research, said exiting the business would be relatively immaterial for 3M, but is a “reminder of long-tail PFAS remediation and compensation risks.”

Updated: 2-14-2023

‘Forever Chemicals’ Maker Defends Their Use, Says It Will Keep Producing Them

CEO of Chemours says varieties of PFAS chemicals can be made responsibly.

Chemical maker Chemours Co. said it would continue producing so-called forever chemicals, saying that the controversial substances can be made safely and are critical for semiconductors and electric vehicles.

Chemours, one of the largest U.S. makers of fluorine-carbon polymers, said that it is expanding production of some varieties of the chemicals and defending their use. Sales for its fluoropolymer business unit were $1.6 billion in 2022, 16% higher than the prior year, the company reported last week.

“Fluorine chemicals have a place in modern society,” Chemours Chief Executive Mark Newman said in an interview. “You can’t have semiconductors without them.”

Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, commonly called PFAS, are long-lasting and resistant to heat, corrosion and moisture. For decades manufacturers have used them to make products such as upholstery coatings, firefighting foam and nonstick pots and pans.

Research has linked exposure to high levels of some types of PFAS with health problems including kidney and testicular cancers, thyroid disease and high cholesterol, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Called forever chemicals because of their long-lasting properties, some forms of PFAS have been found in drinking water, prompting a wave of liability lawsuits against manufacturers, including Chemours and 3M Co. The companies are contesting the lawsuits.

Increasing regulation of PFAS led 3M in December to say it would cease production of all PFAS and eliminate the use of them in other 3M products by the end of 2025.

The EPA has said the risks from PFAS are difficult to determine because people can be exposed to the chemicals in a variety of ways. Exposure can occur from drinking water or breathing air contaminated with PFAS, the agency has said, or from consumer products that contain the chemicals, including cosmetics and food packaging.

Companies about 20 years ago stopped making two PFAS chemicals, known as PFOA and PFOS, which were widely used and had drawn scrutiny over their potential health effects. The chemical industry has disputed some of the EPA’s health findings.

Chemours said there are currently no viable alternatives for many fluoropolymers. The company said PFAS compounds don’t pose a significant risk to human health or the environment when used for their intended purpose.

The company said its fluoropolymers were developed in compliance with regulations and standards in the U.S. and other countries where they are sold. Chemours said it is committed to eliminating at least 99% of PFAS air and water emissions from its manufacturing process by 2030.

Delaware-based Chemours, which was spun out from DuPont Inc. nearly eight years ago, has estimated that fluorine-based chemicals represented around one-fifth of the company’s total sales in 2022.

nnual profit for the company’s fluoropolymer business on an adjusted basis rose by 29% to $367 million in 2022, the company said.

3M’s net sales of PFAS chemicals were about $1.3 billion last year, or about 4% of the company’s total annual sales.

Chemours’s Mr. Newman told analysts last week on a conference call that fluoropolymers can be made responsibly and said they are essential for expanding U.S.-based manufacturing, particularly for semiconductors.

New plants for making semiconductors are being built in the U.S. to shorten supply chains and reduce domestic manufacturers’ reliance on foreign suppliers for chips.

The company said there are more than 4,700 PFAS compounds, though less than 10% of them are in commercial use.

Last week, the European Union’s chemical-regulatory arm started considering restrictions on the use of PFAS compounds to lower humans’ exposure to them and lessen the potential health effects.

Mr. Newman said the company and its customers in Europe intend to vigorously oppose attempts to impose an outright ban, or what he said could be overly broad restrictions on fluoropolymers.

The company said it is investing in reducing emissions from the production of PFAS compounds at its plant in the Netherlands.

“You can expect that we will be very involved and very vocal with our customers,” Mr. Newman said last week. “This is a chemistry that Europe should embrace, and should embrace participants like ourselves who can make this chemistry responsibly.”

Chemours’ PFAS compounds, including corrosion-resistant, nonstick Teflon, are used in industrial processes and in consumer products.

Chemours said it is the only domestic producer of PFA, a fluoropolymer that is used in very thin film for filtering small particles from fluids during the production of semiconductor chips.

Semiconductors are manufactured in special clean-factory environments, and even tiny particles that infiltrate the production process can contaminate chips used in electronic devices, Chemours said.

PFA also is used in the pipe, tubes, valves, pumps and tank linings of semiconductor production equipment, the company said.

Chemours said Teflon is used in a solvent-free process for manufacturing the battery electrodes for battery-electric vehicles. That reduces the production costs for electrodes and improves the performance of batteries in vehicles, the company said.

A fluoropolymer membrane that Chemours markets as Nafion is used in hydrogen fuel cells for hydrogen electric-powered vehicles and in green-hydrogen electrolyzers that separate hydrogen from oxygen in water.

Chemours in January said it would spend $200 million to expand production of Nafion at a plant in France for the hydrogen and electric-vehicle markets in Europe.

“We continue to make significant investments,” Mr. Newman said.

Updated: 3-14-2023

What To Know About ‘Forever Chemicals’ And Your Health

PFAS exposure has been linked to high cholesterol and an increased risk of kidney cancer.

In the eight decades since they were created, so-called forever chemicals have reached remote corners of the Arctic and been detected in the open ocean and the tissue of animal species as diverse as polar bears and pilot whales.

Also known as PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, they can stay in the environment for years without breaking down.

Nearly everyone in the U.S. is believed to have some level of PFAS in their blood, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Manufacturers have faced thousands of lawsuits that claim that products containing the chemicals were harmful and contaminated the environment. The chemicals maker 3M Co., which made PFAS-containing firefighting foam, said in December that it would stop making and using PFAS by 2025.

Recently, a lawsuit against Thinx, a maker of period underwear, claimed that the absorbent products had PFAS in them. Thinx agreed to a settlement last year, but has said that PFAS weren’t part of its product design.

In March, the Environmental Protection Agency proposed the first federal limits on PFAS in public drinking water, which would require water utilities to filter out certain PFAS that have contaminated water supplies.

Scientists Are Still Studying The Effects Of Human Exposure To PFAS. Here’s What To Know:

What Are Forever Chemicals?

These are a class of thousands of compounds that have been used in consumer products and industrial manufacturing since the 1940s, often as slippery coatings to repel water or stains.

They are found in a range of products, including carpets and cosmetics, according to the EPA.

They are in coatings for food wrappers, in dental floss, and are used in some electronics manufacturing. PFAS are also in firefighting foams used at airports and military bases.

“It is really one of the broadest categories of chemical ever used, so that does make it very exceptional,” said Phil Brown, an environmental sociologist at Northeastern University in Boston who has studied the chemicals.

How Do PFAS Chemicals Enter The Body?

People can ingest PFAS through food or water, or encounter them in consumer products. More than 2,800 locations in the U.S. have found PFAS in their drinking water, according to the Environmental Working Group, a nonprofit that tracks the chemicals. Some of those are near military bases that used PFAS-containing foams in exercises for years.

“If people are in a place that has high contamination, then water is going to be important,” Dr. Brown said. “But for the average person who doesn’t have high levels of contamination, food is very often considered to be the most primary route.”

PFAS might pass to food from packaging, or produce and dairy could have PFAS from PFAS-tainted sludge used as a fertilizer, Dr. Brown said. People who hunt or fish might consume meat with high levels of PFAS.

After detecting perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) in rainbow smelt in some lakes, Michigan in January recommended avoiding the fish altogether, or limiting consumption of fish caught in those places.

It is among a handful of states that have issued such warnings after testing game and fish for PFAS compounds.

Some occupations have a higher risk for PFAS exposure because of the tools they work with, according to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, a public-health agency within the CDC that evaluates potentially toxic chemicals.

These include firefighting, painting, laying carpets and even long-term work with ski wax.

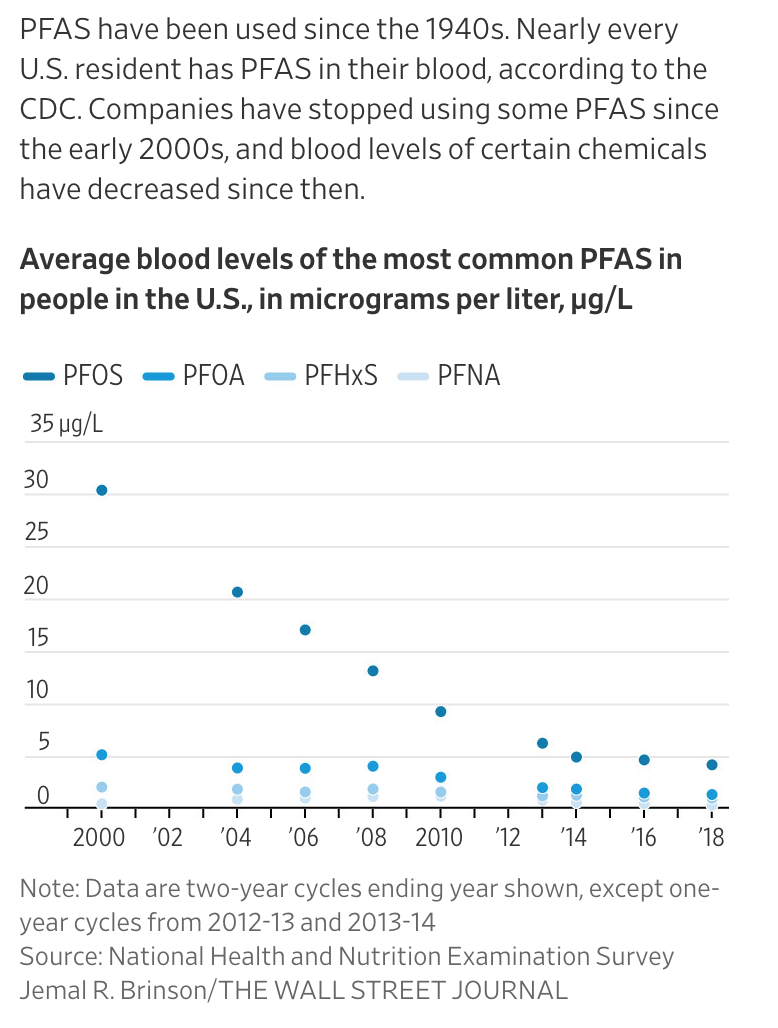

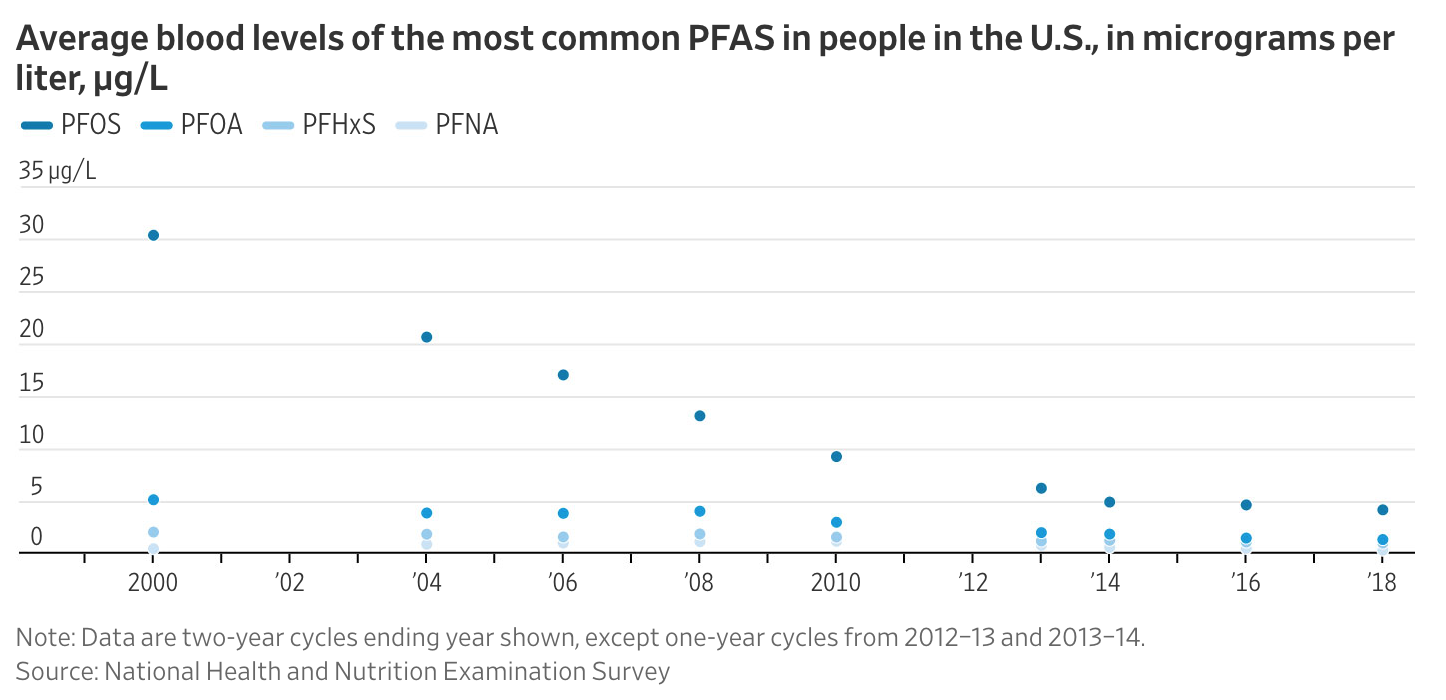

Companies have stopped using some PFAS since the early 2000s, and average blood levels for certain PFAS in U.S. residents have decreased since then, according to the CDC. Dr. Brown said companies have turned to other replacement chemicals that aren’t captured in this testing.

Evidence so far suggests that ingested PFAS is absorbed from the intestine, and can travel to the liver, pass into bile and get stored in the gallbladder, according to Jamie DeWitt, an environmental toxicologist at East Carolina University.

When bile enters the small intestine during digestion, the PFAS gets reabsorbed into the bloodstream and recirculated. Also, rather than exit through urine, PFAS can get reabsorbed into the blood from the kidneys.

This is one hypothesis for why many PFAS compounds stay in the body for years, she said. Another is that they stick to proteins in the blood.

What Are The EPA’s Proposed Regulations?

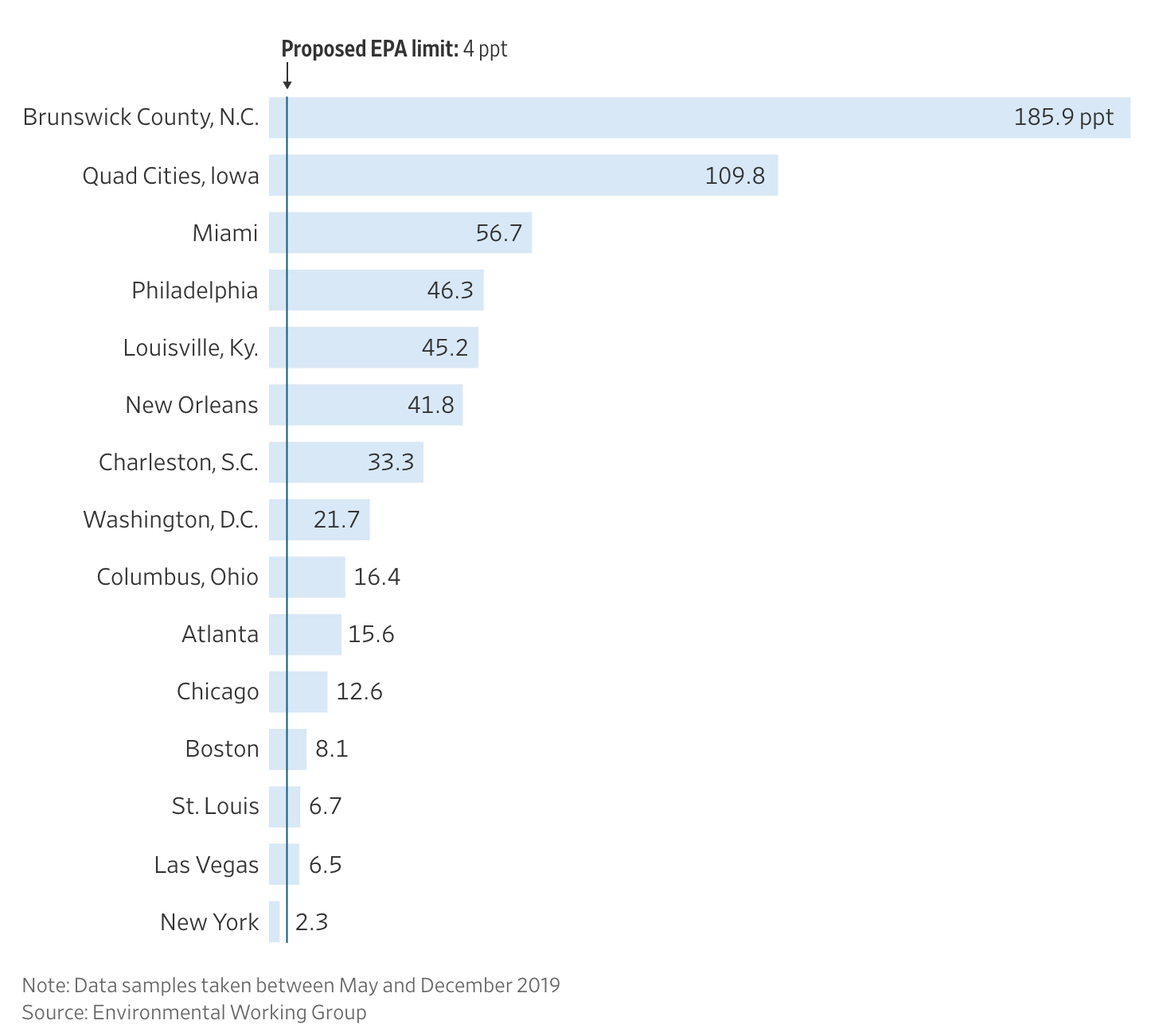

The EPA is proposing limiting two chemicals of PFAS found in drinking water—PFOA and PFOS. The agency would set a limit for PFOA and PFOS of 4 parts per trillion each in public drinking-water systems.

If fully implemented, the rule will prevent thousands of deaths and reduce tens of thousands of serious PFAS-attributable illnesses, according to the EPA.

The agency also said it would regulate four other PFAS chemicals by requiring treatment if the combined level reaches a certain concentration.

Are PFAS Chemicals Harmful?

The U.S. lacks comprehensive national testing of PFAS in blood, which makes it difficult to know who is most exposed, according to Jane Hoppin, an environmental epidemiologist at North Carolina State University.

The CDC’s blood-monitoring effort wouldn’t capture contamination hot spots where people are more highly exposed to PFAS, she said. That is one reason PFAS health harms are challenging to assess. “The fact that there are multiple chemicals adds to the complexity,” she said, with some PFAS better understood than others.

Scientists have found links between PFAS and a handful of health problems, including high cholesterol, a decreased immune response to vaccines in adults and children, and an increased risk of kidney cancer, according to a 2022 report published by the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine that surveyed the scientific evidence on the chemicals.

There isn’t enough research to link any health impacts to specific levels of exposure, according to Dr. Hoppin.

Many studies have examined PFAS and occurrence of ulcerative colitis, thyroid disease, and breast and testicular cancer, suggesting a link between the chemicals and an increased risk of each disease, the National Academies report said.

Some studies have examined if PFAS play a role in diabetes and obesity, and disrupt fertility in men and women, but there isn’t enough evidence to make a link, according to the report.

Lab studies in animals have supported some findings. According to the CDC, PFAS have been linked with liver damage, immune disruption, death and delayed development in newborn animals.

“We know they produce a variety of health outcomes in people and in rodents,” Dr. DeWitt said. “And we have enough evidence now to indicate that they alter bodies to increase risk of diseases.”

Are These Chemicals Harmful To Children And Pregnant Women?

PFAS exposure is linked to an increased risk of high blood pressure during pregnancy, according to the National Academies report. PFAS blood levels in mothers are also linked with low birthweight, the report said.

Fetuses and infants are generally more vulnerable to harmful chemicals than adults are, because their brain and critical organs are rapidly developing, according to Laurel Schaider, an environmental health expert at the Silent Spring Institute in Newton, Mass.

PFAS can pass through the placenta of a pregnant woman to the growing fetus, and PFAS can be transmitted to infants through breast milk, according to the report.

Can You Test For PFAS In Blood?

There are established tests for PFAS in blood, but they aren’t routinely offered in the U.S., according to the CDC. Most people who have had their blood tested have been part of health studies run by the CDC or university scientists.

PFAS blood readings don’t indicate whether a person has a particular disease, Dr. Schaider said. But the information can be a valuable benchmark. “If someone is able to have a follow-up blood test, in a few years, they can evaluate whether their levels are going down,” Dr. Schaider said.

In a continuing nationwide study, the CDC and independent research groups are investigating how exposure through drinking water is linked to, for example, thyroid or liver disease, or high cholesterol.

Those studies are testing the blood of volunteer participants in eight regions where PFAS has been found in drinking-water systems.

Updated: 3-15-2023

How ‘Forever Chemicals’ Are All Around Us, From Winter Coats To Fast-Food Wrappers

The EPA is proposing limits in drinking water on some PFAS, which are found in the blood of nearly everyone in the U.S.

The Environmental Protection Agency is proposing the first federal limits for six PFAS chemicals in drinking water.

The chemicals have been used in industry and consumer products worldwide for more than 70 years because of their ability to resist water, grease and stains and to put out fires.

PFAS, also dubbed forever chemicals, have been found in firefighting foam, drinking water, fast-food containers, dental floss, landfills, hazardous waste sites, manufacturing or chemical-production facilities, fish caught from contaminated water and dairy products from livestock exposed to the chemicals.

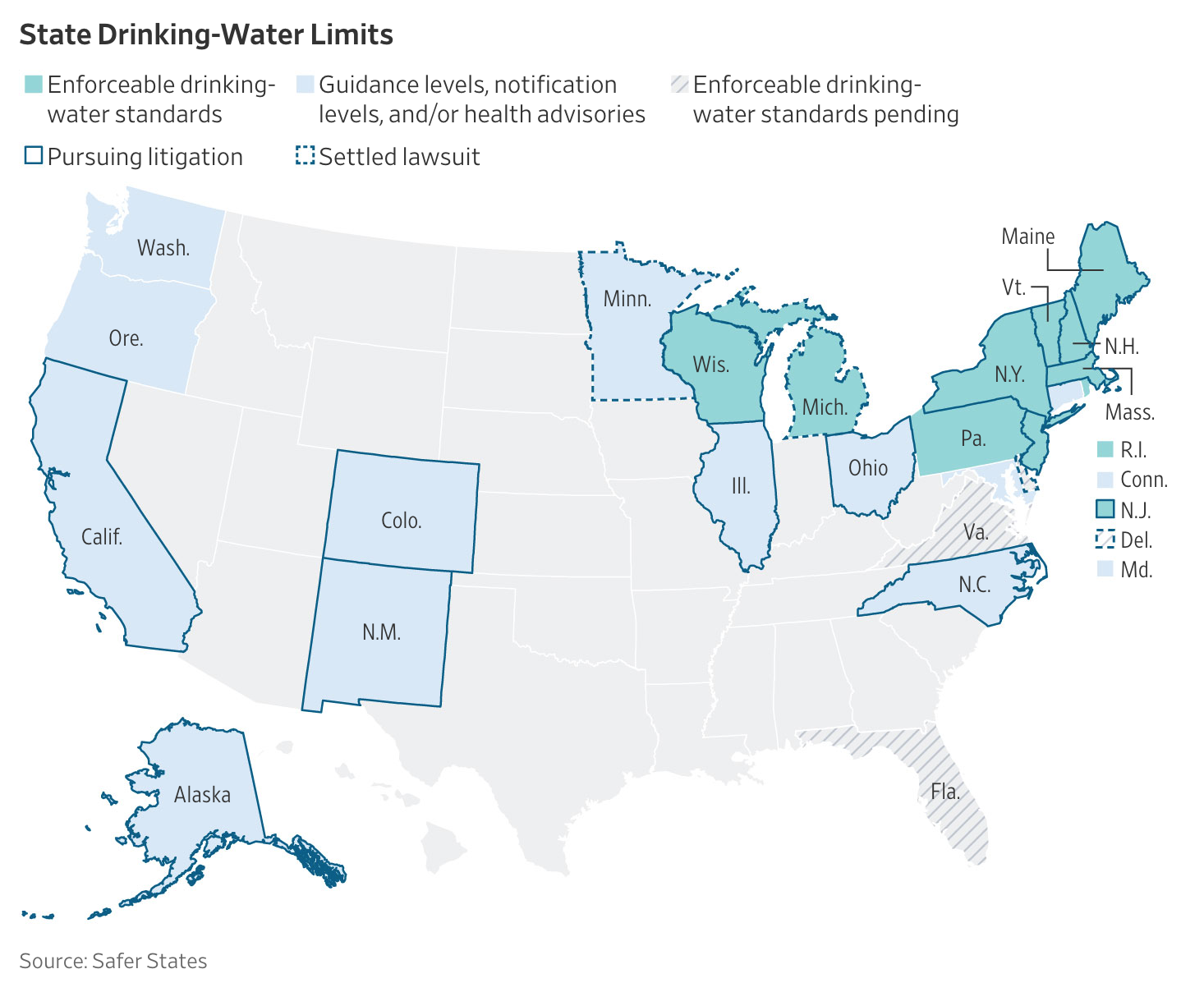

More states have adopted enforceable standards, guidance levels, notification levels, and/or health advisories or are on track to adopt standards to regulate PFAS in drinking water.

Some of those states are involved in litigation against PFAS manufacturers, alleging the makers are liable for the cost of cleaning up contaminated water supplies and other natural resources, a charge the companies deny.

Nearly everyone in the U.S. has PFAS in their blood, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Companies have stopped using some PFAS since the early 2000s, and the levels of certain chemicals in blood have decreased since then.

A 2020 study by the Environmental Working Group found elevated levels of 30 PFAS chemicals in tap water in 31 states and the District of Columbia.

The EPA on Tuesday proposed new rules that would set maximum allowable levels for two compounds in drinking water at 4 ppt—or parts per trillion—each. The EPA also said it would regulate four other PFAS chemicals in drinking water.

Research suggests that exposure to high levels of PFAS may lead to a higher risk of kidney and testicular cancer and other health problems, such as high cholesterol and decreased vaccine response in children, according to the CDC.