Cracks In The Housing Market Are Starting To Show

Sticker shock is just one of numerous signs that a slowdown may already be happening. Cracks In The Housing Market Are Starting To Show

Single-family housing in the U.S. has been exuberant, but it’s vulnerable and the bubble is starting to leak.

Related:

How To Prepare For The Expected And Unexpected Costs of Homeownership

Definitive Resource Covering The Homeowner’s Insurance Market

Emergency Rental Assistance Program

Home Flippers Pulled Out of U.S. Housing Market As Prices Surged

Housing Insecurity Is Now A Concern In Addition To Food Insecurity

Smart Wall Street Money Builds Homes Only To Rent Them Out (#GotBitcoin)

No Grave Dancing For Sam Zell Now. He’s Paying Up For Hot Properties

Investors Are Buying More of The U.S. Housing Market Than Ever Before (#GotBitcoin)

Biden Lays Out His Blueprint For Fair Housing

Housing Boom Brings A Shortage Of Land To Build New Homes

Wave of Hispanic Buyers Boosts U.S. Housing Market (#GotBitcoin?)

Phoenix Provides Us A Glimpse Into Future Of Housing (#GotBitcoin?)

OK, Computer: How Much Is My House Worth? (#GotBitcoin?)

Sell Your Home With A Realtor Or An Algorithm? (#GotBitcoin?)

Robust demand has come first and foremost from the massive monetary and fiscal stimulus that has pumped trillions of dollars directly into the pockets of consumers. Americans have used this money along with cheap and readily-available mortgages to finance houses in suburban and rural locations as they fled cramped and expensive big-city apartments, and also to avoid long commutes.

Millennials are helping to drive demand since many are in their 30s, prime ages for first-time homebuyers. On top of that, publicly-traded real estate investment trusts, big investment firms and pension funds are buying houses to rent out. In March, homes up for resale market spent a record-low 18 days on the market on average, according to the National Association of Realtors.

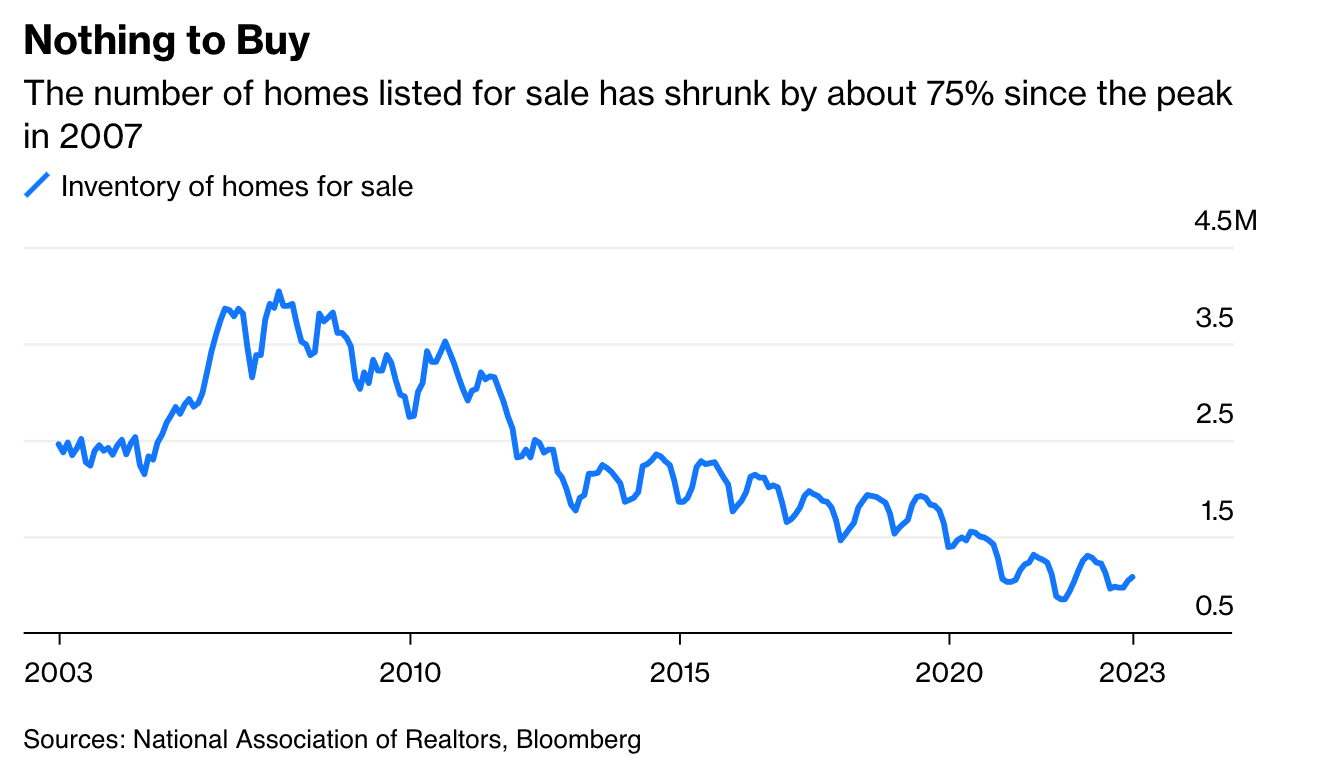

Although demand for single-family houses has surged, supply has not kept up. The market is 3.8 million units short of what is needed to meet demand, according to Freddie Mac, an increase of 50% since 2018. After the collapse of housing with the demise of subprime mortgages in 2008, the builders that survived have become more disciplined.

Also, new construction has been restrained by temporary shortages of materials and surging prices of key building materials such as lumber.

The supply of existing houses for sale has been curtailed as more homeowners decide to stay put. Many aren’t sure where they’d live next in these uncertain times. Also, the availability of cash-out refinancing opportunities has encouraged homeowners to hold on to their abodes instead of moving.

Freddie Mac reports that in the first quarter, $49.6 billion in home equity was cashed out, up 80% from a year earlier and the most since 2007. Another limit on the supply of existing houses for sale has been the pandemic-induced moratorium on foreclosures.

This has spawned feeding frenzies for available homes as eager buyers, some with all-cash offers, engage in bidding wars. Prices of existing home soared 16.2% in the first quarter from a year earlier, and in March, 39% of houses under contract sold for more than their list price, up from 24% a year earlier.

The bonanza conjures up memories of the mid-2000s when the subprime mortgage bubble pushed up prices to levels that were followed by a 35% plunge. Speculation is certainly part of today’s activity, but unlike then, lenders require high credit scores and sizable downpayments.

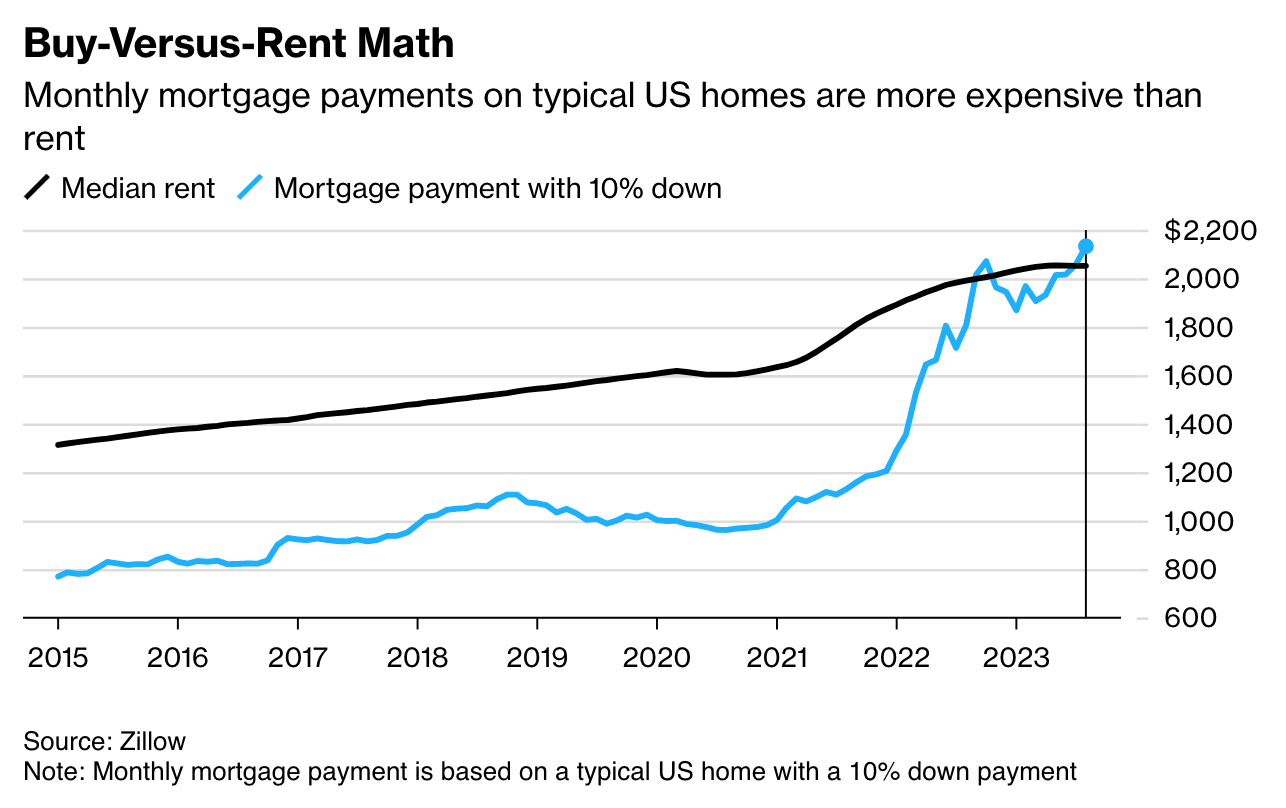

Still, housing is a highly leveraged asset, so a rise in financing costs can be lethal. But I don’t foresee a big leap in U.S. Treasury yields and, therefore, 30-year fixed mortgage rates even though supply-chain disruptions and inefficiencies in restarting the economy are causing a temporary spurt in inflation.

Even so, the gap between 10-year Treasury yields and 30-year fixed-rate mortgages is so narrow that home-loan rates could rise a full percentage point or more and still be within the historic range.

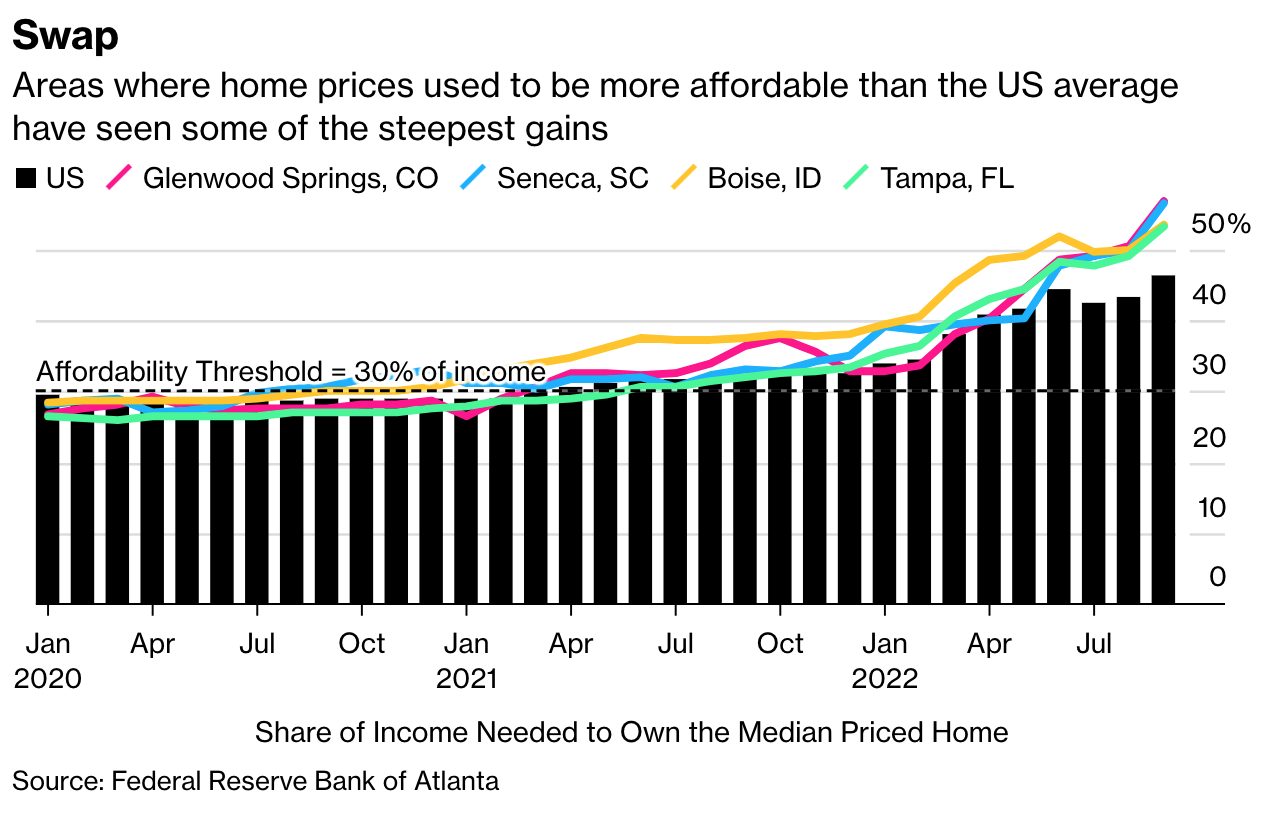

Even without a rise in financing costs, affordability is becoming an issue. In December, before the big run-up in prices, the median price for single-family houses and condos was less affordable than historic averages in 55% of U.S. counties, up from 43% a year earlier and 33% three years earlier, according to ATTOM Data Solutions.

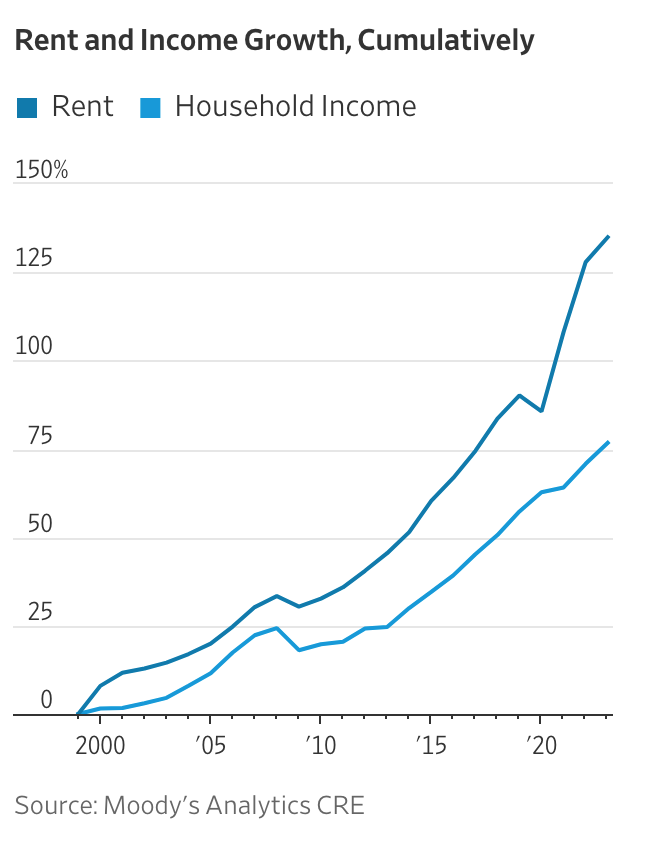

And unless households get further rounds of federal stimulus money, that earlier source of funding for housing will no longer be present. With some 7 million fewer Americans employed now than before the pandemic, household income growth in future quarters probably won’t be sufficient to replace stimulus checks. Plus, much of the excess homeowner equity that can be withdrawn may already be gone.

As the pandemic eases, many Americans will probably continue to prefer single-family houses away from major cities, but some will return, reducing the demand for suburban houses. Meanwhile, high prices will spur supply in the form of new construction.

Furthermore, demand for single-family houses may continue to be curtailed by “doubling up.” Pew Research Center found that 52% of Americans ages 18 to 29 were living with at least one of their parents last year, up from 47% in 2019.

Numerous signs of a slowdown are already apparent. The number of months to exhaust the supply of existing homes on the market at current sales rates rose in each of the first four months of 2021.

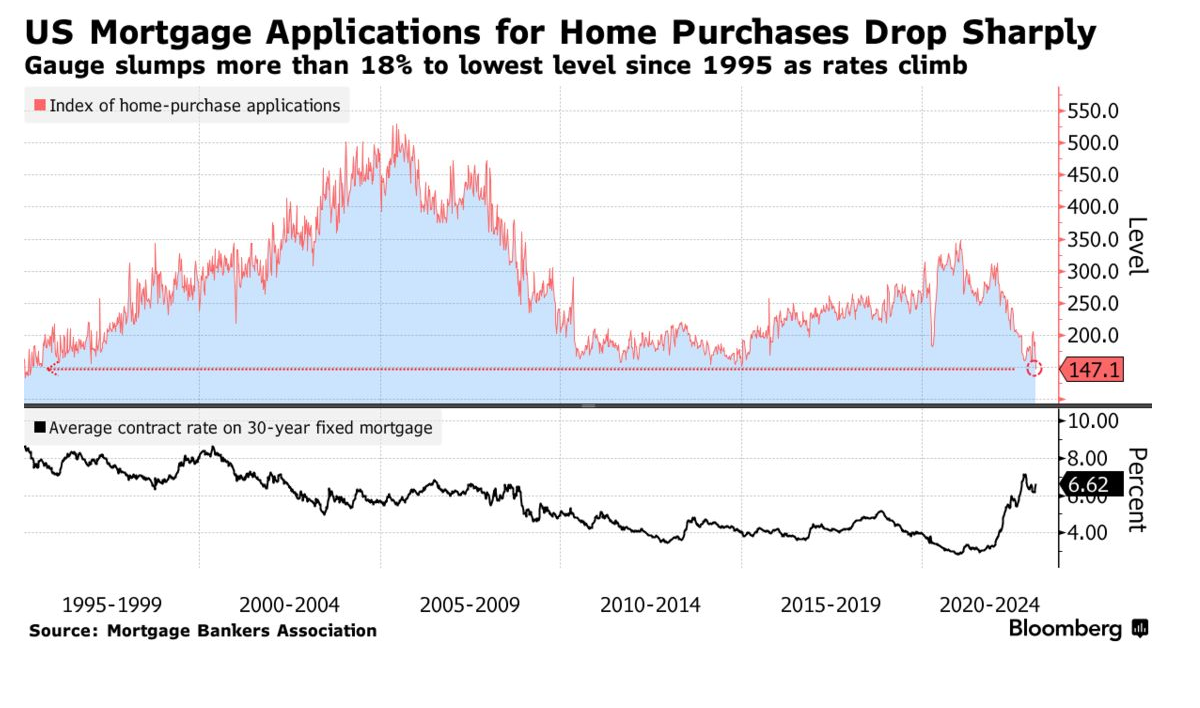

Lenders’ willingness to issue mortgages is at its lowest level since 2014, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association, and those with less than pristine credit scores and without sizeable downpayments are finding it harder to obtain financing. In 2020, 70% of new mortgages were issued to borrowers with credit scores of at least 760, up from 61% in 2019, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Building permits, a harbinger of future housing starts, are nowhere near where they need to be to slake demand. A Conference Board survey finds that plans to purchase houses over the next six months fell from 7.1% in April to 4.3% in May, the biggest drop since monthly numbers began in 1977. Mortgage applications for new purchases are down 18% year-to-date, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association.

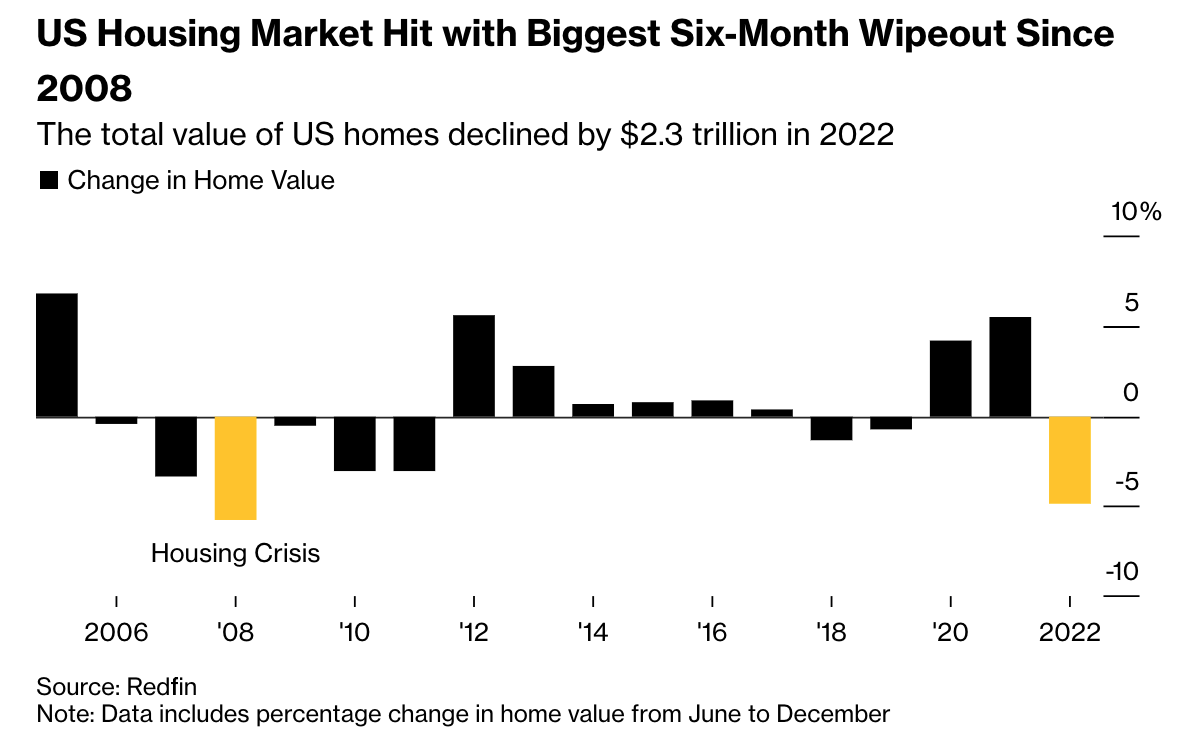

History suggests that when bubbles begin to leak, small tears usually enlarge as more and more weakness in their fabric is revealed, ultimately leading to collapse. The current enthusiasm for single-family housing has reached such extremes that a deflation of the bubble seems likely—and may be commencing.

The Housing Market’s Fever Shows More Signs of Breaking

It turns out there is a limit to how high prices can go.

Housing Fever: The Breakening

In “The Sun Also Rises,” Mike Campbell famously says he went bankrupt “Two ways: Gradually, then suddenly.” The housing market’s mania might end similarly.

We’re getting evidence of the “gradually” part, anyway. Last month Conor Sen pointed out homebuilders were responding to exorbitant lumber costs by just dropping their toolbelts and grabbing a sandwich. This isn’t what you do if you think you’re about to sell a lot of houses at high prices. Now Gary Shilling has found a few more hints of a slowdown, from the rising number of homes on the market to a drop in permits for new construction to consumers balking at ludicrous prices.

Gary also notes the pandemic trends driving the market recently — stimulus money, plunging interest rates, New York City being dead forever — are stalling or reversing. There may soon be a better time for you to buy that sprawling New Jersey estate.

Updated: 6-20-2021

For Many Home Buyers, A 5% Down Payment Isn’t Enough

Half of mortgage borrowers put down at least 20% in April. That is locking many people out of homeownership.

Would-be home buyers without big piles of cash are getting left on the sidelines.

In the turbocharged housing market, prices are surging and homes on the market are routinely selling for far more than the listing price. Those who can’t afford big down payments are often the ones losing out.

Half of existing-home buyers in April who used mortgages put at least 20% down, according to a National Association of Realtors survey. In 10 years of record-keeping, that percentage has hit or exceeded 50% three times, and all have been since last fall. A quarter of existing-home buyers in April paid cash, the highest level since 2017, NAR said.

Oscar Reyes Santana has been house hunting with his parents and siblings for more than a year in California’s San Fernando Valley. They are all first-time buyers and budgeted for a 5% down payment.

The family bid on at least five homes, each time offering at least $30,000 above the asking price, but they lost out every time, said Mr. Reyes Santana, who is 23.

“It’s been really tough to try to beat everyone else,” he said.

They have all but given up the search for now, and are focused on saving up for a bigger down payment.

Home prices are surging. The median existing-home price rose 19% from a year earlier to $341,600 in April, a record high, according to NAR. That is largely because there aren’t enough homes on the market to meet demand.

In such a housing market, sellers can often choose among multiple offers. Cash buyers have an advantage because they don’t need to secure mortgages, which can make the transaction go faster. Sellers sometimes worry that offers with smaller down payments are likelier to fall through during the loan-closing process, agents say.

Many borrowers who can afford only small upfront costs get loans insured by the Federal Housing Administration or the Department of Veterans Affairs. In an April NAR survey of real-estate agents, 27% said sellers were unlikely to accept an offer with an FHA or VA loan, and another 6% said sellers would refuse such an offer. These loans are less attractive to sellers because they have stricter closing conditions, real-estate agents say.

While mortgage originations of all types rose last year as home buying surged, FHA and VA loans lost market share to conventional loans. FHA loans, which often go to first-time buyers, accounted for 10% of home purchases in the first quarter of 2021, the second-lowest level since 2008, according to Attom Data Solutions.

“It’s very hard to get my FHA offers accepted,” said Olivia Chavez Serrano, a real-estate agent in Los Angeles.

Bigger down payments can cushion the housing market in a downturn. In the 2007-09 recession, home buyers who had made tiny down payments were quickly underwater as soon as home prices started to fall.

A lump sum of 20% or more can be hard to come up with as home prices skyrocket, especially without help from family members. “I’d say at least 50% of my first-time home buyers are getting gifts right now,” said Chris Borg, a mortgage broker at Vantage Mortgage Group Inc.

Low-down-payment loans and down-payment assistance programs are touted by affordable-housing advocates as crucial tools for increasing the homeownership rate, particularly for minority buyers. In 2019, a higher proportion of FHA and VA borrowers were Black or Hispanic compared with conventional-loan borrowers, according to the Urban Institute. Some congressional Democrats have proposed new down-payment assistance initiatives to help first-time buyers.

Surging home prices are also complicating appraisals, which means some buyers are being forced to shell out more cash than they had expected.

Appraisals are based partly on recent sale prices for comparable homes in the area. When housing prices rise quickly, appraisal values don’t always keep up. Mortgage lenders will typically lend only enough to cover the appraised value of a home, so when an appraisal comes in low, the buyer has to make up the difference or let the deal fall through.

For example, a buyer who plans to put 20% down on a $500,000 purchase expects to pay $100,000. But if the home is appraised at $450,000, the cash payment goes up to $140,000—the sum of the $50,000 shortfall plus a $90,000 down payment.

Many buyers are still getting offers accepted without putting 20% down. First-time home buyers who used mortgages paid 9.1% down on average year-to-date through mid-May, though that is up from 8.4% for all of 2020, according to CoreLogic. Repeat buyers paid 16.6% down on average.

Briana Stansbury, who works at a community college in Portland, Ore., recently made an offer on a two-bedroom house. She used a 5%-down loan program that Freddie Mac offers for first-time buyers, and she agreed to go through with the purchase even if the appraisal came in as much as $10,000 below her purchase price of $371,500.

That put Ms. Stansbury at risk of having to come up with extra cash in a hurry, but she had lost out on bids for other houses and thought it would give her a leg up.

Ms. Stansbury lost sleep while she waited for the appraisal. But it came back above the sale price, and she closed on the house in May.

Danyell Allen of Cedar Park, Texas, felt ready to buy a house this year. She had saved up for a 5% down payment. Her children wanted to paint their walls and adopt a pet, which they can’t do in their rental house.

But after losing out on more than 10 offers, she called off the search. “The lowest I heard I was beat out on any home was $30,000 over asking price,” she said. “That’s not something I can do.”

Updated: 6-29-2021

U.S. Home-Price Growth Rose To Record In April

S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller national index of average home prices up 14.6%.

U.S. home prices surged at their fastest pace ever in April as buyers competing for a limited number of homes on the market pushed the booming housing market to new records.

The S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller National Home Price Index, which measures average home prices in major metropolitan areas across the nation, rose 14.6% in the year that ended in April, up from an 13.3% annual rate the prior month. April marked the highest annual rate of price growth since the index began in 1987.

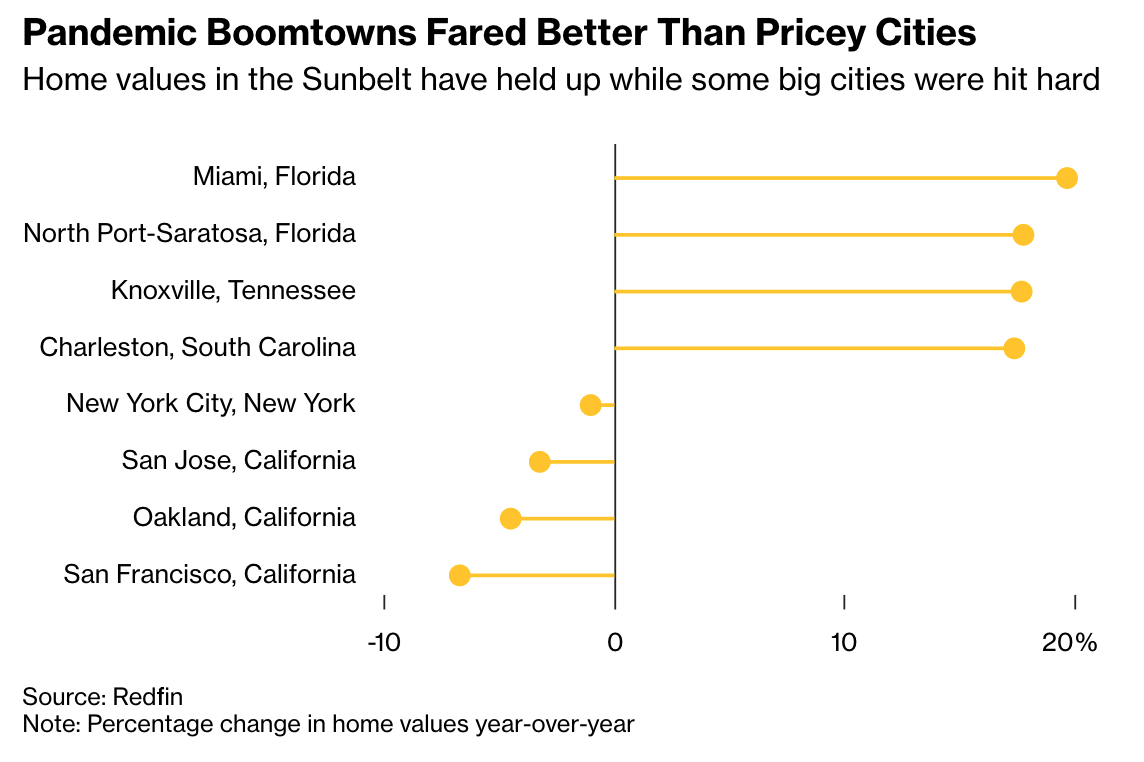

Home prices have surged this year due to low mortgage-interest rates, which have spurred strong demand, and a continued shortage of homes for sale. Many homes are getting multiple offers and selling above asking price. The home-price surge is widespread around the U.S., affecting buyers and sellers in big cities, suburbs and small towns.

The median existing-home sales price in May rose almost 24% from a year earlier, topping $350,000 for the first time, the National Association of Realtors said earlier this month.

Home sales have started to decline in recent months, because there aren’t enough houses on the market for all the buyers looking to buy. Rising prices have also deterred buyers, and many builders are capping sales to manage their costs and production pace. Some economists expect the pace of home-price growth to slow as well by the end of the year.

But real-estate agents say in many areas, the market is so frenzied that a slight slowdown in activity wouldn’t make a big difference.

“It’s been crazy within the last year,” said Scott Chase, chief operating officer at Intero Real Estate Services, who is based in Los Altos, Calif. “My thinking is, is this going to slow down with people being vaccinated and wanting to go on vacation? [But] it is still incredibly active.”

While the national pace of price gains is now faster than during the housing boom in the early 2000s, this market is less prone to a downturn, economists say. Ultralow mortgage interest rates mean that the typical home buyer’s monthly payment hasn’t risen as rapidly as the typical house price. Lending standards are also stricter.

But fast-rising home prices and the limited inventory are making homeownership less attainable for first-time buyers or those with limited budgets.

“Affordability is worsening,” said Mark Fleming, chief economist at First American Financial Corp. “That’s what will eventually cause house prices to not continue to accelerate and then eventually begin to slow down.”

Some workers may also decide to hold off on moving until they know their companies’ plans for returning to the office. The rise in remote work during the pandemic spurred many households to move farther from their offices.

“Folks that were looking to buy a home, thinking that they were going to work remotely, are now increasingly putting those decisions on hold,” said Mark Vitner, senior economist with Wells Fargo & Co. “I would expect that home prices are going to moderate all over the country later this year and in 2022.”

The Case-Shiller 10-city index gained 14.4% over the year ended in April, compared with a 12.9% increase in March. The 20-city index rose 14.9%, after an annual gain of 13.4% in March. Price growth accelerated in all of the 20 cities.

Economists surveyed by The Wall Street Journal expected the 20-city index to gain 14.5%.

Phoenix had the fastest year-over-year home-price growth in the country for the 23rd straight month, at 22.3%, followed by San Diego at 21.6%. Charlotte, N.C., Cleveland, Dallas, Denver and Seattle all recorded record-high annual price gains.

Andy Rodrigues and Karibel Montero started looking for a house in the Seattle area last fall, because they were renting a one-bedroom apartment and wanted more space.

“People were going crazy with the offers they were making,” Mr. Rodrigues said. “At some point, we actually decided to stop house hunting and just go and rent because we found it was really difficult.”

The couple eventually bought a three-bedroom home in April in Lynnwood, Wash., farther from Seattle than they had originally looked.

A separate measure of home-price growth by the Federal Housing Finance Agency also released Tuesday found a 15.7% increase in home prices in April from a year earlier, a record in data going back to 1991.

Updated: 7-4-2021

For Millennials, A Starter Home Is Hard To Find

Shortage of small, single-family homes leaves some first-time buyers frustrated and out of luck in a hot housing market.

The shortage of available starter homes feels like yet another hurdle blocking some millennials’ path to traditional money milestones.

“It just feels like every little thing keeps getting put on hold,” said Samantha Berrafato, a 27-year-old house hunter searching for her first home in the Chicago area. “I’ve been putting having kids on hold, and I had put having a wedding on hold because we just couldn’t afford it. Now it’s like [that with] the house buying.”

The first rung on the homeownership ladder has long been an affordable “starter home.” These houses, with their smaller footprints and selling prices, allowed young homeowners to build wealth and upsize as they started their families.

But a number of factors are complicating this decadeslong trend.

Supply of “entry-level housing”—which Freddie Mac defines as homes under 1,400 square feet—is at a five-decade low.

Surging prices and stiff competition mean there aren’t enough smaller, more affordable starter homes to go around in many regions. The pandemic and subsequent recession, along with the student debt crisis and delayed family formation, contributed to frustration and despair among younger house hunters.

“There just aren’t enough of these homes to fulfill the demand,” said Ed Pinto, director of the AEI Housing Center at the American Enterprise Institute. “It’s creating this ‘Great American Land Rush,’ as I call it. People are moving around and there’s tremendous demand, but the inventory is down.”

Three months ago, Ms. Berrafato and her fiancé began looking to buy their first home with a budget of around $300,000. They secured a 3.25% rate on a 30-year mortgage and with a 5% down payment.

They widened their search to include fixer-uppers and foreclosures further out in the suburbs. In June, their offer for a 1,200-square-foot home was accepted.

As of 2020, the median age of a first-time home buyer was 33 years old, up from 30 years old a decade ago, according to the National Association of Realtors.

Delaying homeownership has far-reaching consequences for buyers’ financial lives. Those who became homeowners between the ages of 25 and 34 accumulated $150,000 in median housing wealth by their early 60s, according to an analysis from the Urban Institute. Those who waited until between the ages of 35 and 44 to buy netted $72,000 less in median housing wealth.

“This is a big deal,” said Sam Khater, chief economist and head of Freddie Mac’s Economic and Housing Research division. “We need to think about how we talk about affordable housing, because for most people, when they hear affordable housing, there’s an instant negative reaction. They think ‘low-income,’ right? The issue now is these fissures have not just invaded the middle class. It’s now going up into the upper-middle-income strata.”

Lately, data from the National Association of Home Builders shows new construction is again giving priority to higher square footage for single-family homes, a trend likely spurred by the widespread shift to working from home and house hunters’ need for more space.

“It’s been the hardest kind of home to build over the last five, six or seven years,” Robert Dietz, chief economist at the National Association of Home Builders, said of starter homes.

In addition to competing with other buyers, house hunters are sometimes competing with investors, hedge funds and other huge firms, according to previous reporting from The Wall Street Journal.

As the summer selling season winds down, some house hunters feel they may soon have to find a rental that can bridge the gap or simply save their energy so they can resume looking when prices cool off.

Matthew Libassi, a 35-year-old public relations professional, is looking to buy with his husband on Long Island. He recently sold his apartment and moved in with family to save money. In his search for a home around $500,000, he has been disappointed in the lack of affordable small homes for a young couple.

“We don’t have a crazy list of demands,” he said. “But the stuff that we’re seeing is just major overhauls and with putting all the money that we have in, it’s just not doable.”

Mr. Pinto of the AEI Housing Center predicts the wait could be longer for many buyers. He expects more people to continue moving outside of metro areas in search of more space and greater affordability as employers expand their work-from-home policies post-pandemic.

“We think this is going to continue for some time, for years,” Mr. Pinto said. “Bottom line is, if you’re in an area like Phoenix or Raleigh or Austin, the people who are the current residents who would normally want to get on the first rung of that ladder—they’re going to have a much harder time.”

When the hunt finally comes to a close, relief isn’t always immediate. Though Ms. Berrafato got her starter home, there remain many costs to consider, including moving expenses and getting out of their rental lease early.

“We are so relieved and excited, but now comes new stresses,” she said.

Updated: 7-9-2021

Homebuilder Rally Turns To Rout On Signs Of Fading Housing Boom

The outlook for U.S. homebuilder stocks is darkening as investors see slowing home sales and skyrocketing prices as a sign the housing boom may fade.

An S&P index of 16 builders had surged nearly 250% between March 2020 and early May as the housing market proved one of the rare bright spots in an economy paralyzed by the pandemic. But the index has slumped about 12% since then, with industry bellwethers DR Horton Inc. and PulteGroup Inc. among the 11 companies that saw double-digit declines.

The retreat came as multiple metrics showed that the real estate market is cooling off. New home sales and housing starts undershot median economist estimates for April and May, while mortgage applications fell to their lowest in more than a year.

With home price surging at the fastest rate in more than three decades, more than half of consumers surveyed by the University of Michigan said in May that it was a bad time to buy a house, the highest share since 1982.

These disappointing housing data prompted analysts to slash ratings and forecasts. DR Horton and TRI Pointe Homes Inc. were downgraded by RBC Thursday on concerns that order growth will slow as backlogs pile up. PulteGroup was cut to neutral last week by Goldman Sachs Group Inc., which cited a lack of upside to the company’s valuation.

“To the extent the data continues to weaken, I think there would be further risk to the stocks,” RBC analyst Mike Dahl said in an interview. The housing market is reaching pricing levels “that in the past have corresponded with a slower demand environment.”

For now, homebuilders are still able to command high prices due to low inventories and rock-bottom mortgage rates. The prices of about 72% of base floor plans were raised in June, according to RBC data, well above 47% last year. Companies including Lennar Corp. are even experimenting with auctions in some areas where demand is outstripping supply.

But BTIG analyst Carl Reichardt said he is telling homebuilders not to be overaggressive. He is “nervous” that builders may end up in a negative feedback loop where builders have to cut prices to retain buyers that are discouraged by ferocious bidding wars.

“We have to make sure the builders don’t kill the goose that lays the golden egg,” Reichardt said in an interview.

Bull-Bear Tussle

Evercore ISI’s Stephen Kim, who labeled himself at the “extreme bullish end” of his peers, disagrees that decelerating home sales indicate a slowdown in demand. Instead, he argued that builders are holding back inventories deliberately even though new homes are needed. The gap between supply and demand is still wide, he said.

Kim expects sales to accelerate by September and sees the recent share-price drops as a buying opportunity. Following the latest round of selling in homebuilder shares, “there isn’t any name that I would say is not worth owning,” he said.

In the long run, the economic recovery, low mortgage rates and millennial buyers may benefit builders, though Reichardt said stock trading is likely to be “choppy” before homebuilders work through their backlogs and fix supply-chain issues.

“Concerns are going to stay with us for a little while,” Reichardt said. “You’re going to have this tussle between long-term bull and short-term bear through the summer and into the fall, which means stocks will be relatively range-bound.”

These Tenants Want Rent Relief. But They Also Want Lasting Change

Renter assistance and affordable housing funds are starting to come through in some parts of the U.S. But some tenants organizations see this as the moment to ask for more.

With the end of a federal moratorium on evictions fast-approaching, some renters are looking beyond immediate relief funds for what they see as more lasting solutions to the U.S. affordable housing crisis.

In California, that means pushing back on the dominance of big landlords; in Missouri, it’s pushing to keep developers and bankers out of the affordable housing decision-making process.

Both examples are an evolution of activists’ movement to cancel the rent at the start of the pandemic in the U.S. last year. With the eviction moratorium expiring at the end of July, state and local governments are racing against the clock to distribute billions of dollars in federal relief funds.

Tenants associations made up of residents in the San Francisco Bay Area and Los Angeles are resisting applying for government rent relief. Instead, they’re asking their buildings’ large property managers — Mosser Living and Veritas Investment — to forgive their rent entirely.

Though some of the members of the tenants associations are thousands of dollars in debt, their fight is about more than just their own rent payments. Their goal is to demand these landlords cover the cost of Covid financial losses, and to make sure public rent relief dollars flow to tenants with landlords who they perceive as unable to forgive rent entirely.

“We’re not just negotiating for ourselves but for the whole city,” says Eric Brooks, who’s been a tenant in a San Francisco property operated by Veritas for 27 years.

California Governor Gavin Newsom has said that the state’s $5.2 billion rental assistance program will cover every eligible renter in need. But some housing advocates say that there could still be thousands who fall through the cracks, particularly in some cities like San Francisco.

Whether or not that will prove to be enough funding, the activists say they are making an ideological argument, not just a practical one: In bailing out tenants, they say, the government shouldn’t also bail out the city’s largest landlords.

The San Francisco Board of Supervisors laid out a similar case in April, when it passed a resolution that urged corporate landlords to step back and let smaller landlords have first dibs on the city’s rent relief funds.

A San Francisco–based company, Veritas oversees some $3.5 billion in assets, including more than 7,000 apartment units, making it one of the largest apartment managers in California. As it contended with Covid layoffs, Veritas went home with $3.6 million in federal Paycheck Protection Program loans while expanding its rental housing portfolio. The company also issued its own moratorium on evictions across its properties.

Veritas has maintained that all of its eligible tenants should apply for government relief. “Veritas residents who are eligible for public funds are just as deserving as other residents throughout the city who are applying for financial relief from hardship caused by the pandemic,” said Jeff Jerden, COO of Veritas Investments, in a statement. “If all state and city funds are expended, we have committed publicly to work with all residents that have remaining past due balances and would have qualified for rental relief under the state’s definition of need to ensure they can stay in their homes.”

A spokesperson from Mosser Living declined to comment.

In addition to state and federal funds, there is additional money newly earmarked for for San Francisco rent relief via a recent ballot initiative, Prop 1.

That funding is sourced from taxes on the city’s most expensive property transfers, which is why the tenants associations say they will reject that, too.

“Our goal would be to prevent those funds from simply circling back to the entities who were taxed in the first place, like Veritas,” said Brad Hirn, the lead organizer of the Housing Rights Committee of San Francisco, who has been working with tenants associations at Mosser and Veritas. “[T]he Prop I funds should benefit small landlords and their tenants.”

Tom Bannon, the CEO of the California Apartment Association, which represents apartment landlords, doesn’t see any grounds for making that distinction, and stresses that only a fraction of California’s multi-billion-dollar fund has been depleted so far.

“If a landlord, large or small, has not been paid rent because their tenants have been impacted financially by Covid, then no matter who you are, you should get the rental assistance, that’s why the dollars are there,” he said.

Kansas City: A Pitch For Tenant-Led Development

In Kansas City, Missouri, a progressive tenants association is pushing for a structural overhaul to a new affordable housing program that would given decision-making authority to tenants instead of banks or investors.

The group, KC Tenants, is pitching a plan for a People’s Housing Trust Fund, essentially a tenant take-over of a nascent city program to fund building and preserving housing for the most vulnerable families. The city’s housing trust fund was established in 2018 but only funded in May, when it was seeded with $12.5 million from the federal American Rescue Plan.

Housing Trust Funds Are Not Novel: The federal government and 47 states, including Missouri, have housing trust funds, which subsidize housing for extremely low income families.

The Missouri Housing Development Commission, which administers the state’s housing trust fund, comprises four elected leaders (including the governor) and six appointed commissioners, all of whom are currently bankers or investors.

Although an advisory committee for the Missouri Housing Trust Fund includes many nonprofit leaders and community advocates, activists with KC Tenants want to see more grassroots representation.

They are calling for a board of renters installed at the helm of the newly funded municipal housing trust fund. They also want the program to be funded by a combination of funds diverted from law enforcement and tax and fee revenue from real estate transactions.

These changes would facilitate other goals for the group: defunding police and taxing gentrification. According to the activists, a People’s Housing Trust Fund would build affordable housing while also drawing resources away from the entities that make marginalized communities more vulnerable.

“We want to make sure that there aren’t developers at the lead or others interested in making profits off people,” says Erin Bradley, a leader with KC Tenants.

All Landlords or Small Landlords?

That anti-corporate sentiment is common among tenant associations and their allies. In California, tenants fighting to stay in their buildings also fear that if the larger property managers are able to weather the storm better than smaller landlords, they’ll gobble up distressed properties and monopolize the city’s rental homes.

Progressive lawmakers often take care to distinguish the need for rent relief for small landlords versus for all landlords. Compared to larger landlords, small landlords are more likely to be people of color, have lower incomes themselves, and be retirees who rely on rental income.

“They’re going to become massive giants in San Francisco,” said Maria Torech, through a Spanish translator, referring to Veritas, her landlord. Since losing her income last March, she’s racked up $30,000 in rent debt.

Another tenant, Mario Perez, said he applied for rent relief to cover unpaid rent accrued when he lost his job at a restaurant.

But based on conversations with the Mosser Tenants Association, he’s ready to withdraw his application, he said through a Spanish translator.

Another consideration for tenants who may lack official documentation is the fear that interacting with a government official, rather than a known private entity, could make them vulnerable to deportation.

Neither tenants association would say publicly how many members they had. The Veritas Tenants Association has been organizing since 2017, with members in “close to 130 buildings in San Francisco, the sole Veritas building in Alameda, several buildings in Oakland, and going on 10 in L.A.,” said Hirn.

Among the dozen tenants CityLab spoke to, three said they’re up to date on payments and aren’t at an immediate risk of eviction. They consider themselves part of the broader push for what they see as a more just and efficient distribution of funds.

The California Apartment Association’s Bannon stresses that large or small, landlords have mortgages and insurance and staff to pay. “How can you ask a landlord to just forgive rent? That doesn’t make any sense.”

Updated: 7-22-2021

The Shortage of Starter Homes Extends Beyond Major Cities

Supply of entry-level housing in U.S. is near a five-decade low, according to research by Freddie Mac.

For first-time buyers looking for starter homes in this year’s hot housing market, a decadeslong trend could further delay this long-awaited money milestone.

The supply of entry-level housing, which Freddie Mac defines as homes up to 1,400 square feet, is near a five-decade low, and data on new construction from the National Association of Home Builders shows that single-family homes are significantly bigger than they were years ago.

Homeowners from previous generations had access to smaller homes at the start of their financial lives. In the late 1970s, an average of 418,000 new units of entry-level housing were built each year, according to data from Freddie Mac. By the 2010s, that number had fallen to 55,000 new units a year. For 2020, an estimated 65,000 new entry-level homes were completed.

“You can really draw a straight line from the 1940s down to the most recent years, which is really striking and also very concerning,” said Sam Khater, chief economist and head of Freddie Mac’s Economic and Housing Research division.

A pre-markets primer packed with news, trends and ideas. Plus, up-to-the-minute market data.

Mr. Khater said he initially expected to see this drop most acutely in historically expensive metropolitan areas such as New York and San Francisco. But looking across the country, he saw that house hunters in many different areas were facing the same problem.

“What was really striking to me was the consistency in the decline in the share of entry-level homes, irrespective of geography,” Mr. Khater said. “The thing that struck me the most was that really, it’s all endemic. It’s all over the U.S. It doesn’t matter where.”

This phenomenon is affecting real estate in 10 of the largest states, according to an analysis from Freddie Mac. In Florida, for example, the share of homes with living area up to 1,400 square feet was 58% of new housing supply in 1985. Thirty years later, the share plummeted to 12%.

Homeownership leads to greater wealth for those who buy earlier. An analysis from the Urban Institute estimates that those who became homeowners between the ages of 25 and 34 accumulated $150,000 in median housing wealth by their early 60s. Meanwhile, those who waited until between the ages of 35 and 44 to buy netted $72,000 less in median housing wealth.

When Kevin Crowder, a 52-year-old homeowner and economic-development consultant, bought his first starter home in 2003, he found a 1,000-square-foot apartment in the Miami area. In 2006, he bought what he said is his largest home ever: a two-bedroom house at 1,250 square feet.

“It’s insane what you see in the single-family market here with the pricing,” he said. “I would disagree that larger is needed. I think smaller is needed.”

Eager buyers have sparked bidding wars in many places, as remote work allows them to expand their house hunts. Further challenges—the crush of the student-loan crisis and ongoing wage stagnation—make it difficult for some to save a competitive down payment.

“We’ve got a record number of entry-level, demand buyers: the millennials coming into the market,” Mr. Khater said. “And yet we’ve had a seven- or eight-year decline in entry-level homes, and that’s not going to change.”

U.S. Median Home Price Hit New High In June

Median price rose to $363,300 as sales increased 1.4% on strong demand.

Continued strong demand pushed the median U.S. home price to a record high in June, though the national house-buying frenzy cooled slightly as supply ticked higher.

Existing-home sales rose 1.4% in June from the prior month to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 5.86 million, the National Association of Realtors said Thursday. June sales rose 22.9% from a year earlier.

The median existing-home price rose to $363,300, in June, up 23.4% from a year earlier, setting a record high, NAR said, extending steady price increases amid limited inventory.

Separate figures on the labor market showed that the number of people receiving jobless benefits fell to the lowest level since early in the pandemic as states withdrew from participation in federal pandemic relief. First-time applications, meanwhile, rose as supply constraints persisted in the auto industry.

The housing-market boom is easing slightly, as rising prices are prompting more homeowners to list their houses for sale. Homes sold in June received four offers on average, down from five offers the previous month, said Lawrence Yun, NAR’s chief economist.

But the number of homes for sale remains far lower than normal, and robust demand due to ultralow mortgage-interest rates is expected to continue pushing home prices higher.

As more homes come on the market, they are quickly snapped up by buyers, said Robert Frick, corporate economist at Navy Federal Credit Union.

“Demand is trumping everything,” he said. “Higher inventory isn’t going to take the brakes off price increases.”

Many homes are selling above listing price and receiving multiple offers. The typical home sold in June was on the market for 17 days, holding at a record low, NAR said.

Dana Laboy and John Niehaus of Columbus, Ohio, started shopping in February for a house costing $400,000 or less, but they raised their budget after losing out on multiple offers, Ms. Laboy said.

“When we were losing out on houses left and right every weekend for eight weekends in a row, it was very demoralizing,” Ms. Laboy said. “I did not think that we would offer up to $40,000 over and still not get it, like we did in some cases.”

The couple’s rental lease ended in March and they moved in with Mr. Niehaus’s parents while they continued house hunting. They bought a three-bedroom house in June for $447,200.

There were 1.25 million homes for sale at the end of June, up 3.3% from May and down 18.8% from June 2020. At the current sales pace, there was a 2.6-month supply of homes on the market at the end of June.

Market watchers expect the housing frenzy to continue to cool in the coming months, as the number of homes for sale increases and high prices force some buyers out of the market.

“I don’t believe you’ll see the kinds of [price] increases you’ve seen in the last 12 months,” said Sheryl Palmer, chief executive of home builder Taylor Morrison Home Corp. “That’s not sustainable.”

First-time buyers or those who can only afford small down payments are struggling the most to compete. More than half of existing-home buyers in June who used mortgages to buy a property put at least 20% down, according to a NAR survey. Buyers are also making their offers stand out in this competitive market by agreeing to buy houses without contract terms that typically protect buyers, such as inspection requirements.

Alex Wolf and Maggie Jasper bought a two-story home in the Denver suburbs in June after a few months of hunting. Mr. Wolf and Ms. Jasper didn’t waive the home-inspection requirement in their offers, which made it harder to compete.

“I’m not willing to take on quite that much risk,” Mr. Wolf said. “We had a lot of things working against us, so we got really lucky.”

Existing-home sales rose the most month-over-month in the Midwest, up 3.1%, and in the Northeast, up 2.8%.

Sales were especially strong at the high end of the market. Sales of homes that were priced at more than $1 million more than doubled in June compared with a year earlier, according to NAR.

Building activity has increased due to the strong demand, but home builders are limited by labor availability, land supply and material costs. A measure of U.S. home-builder confidence declined in July, the National Association of Home Builders said this week.

Housing starts, a measure of U.S. home-building, rose 6.3% in June from May, the Commerce Department said earlier this week. Residential permits, which can be a bellwether for future home construction, fell 5.1%.

News Corp, owner of The Wall Street Journal, also operates Realtor.com under license from the National Association of Realtors.

Updated:7-26-2021

New Aid Coming For Mortgage Borrowers At Risk Of Foreclosure

Biden administration aims to reduce monthly payments by up to 25% for those with federally backed mortgages who are at the end of forbearance.

Borrowers who fell behind on their mortgages during the Covid-19 pandemic and continue to face economic hardship will get help from a Biden administration program announced on Friday, a bid to prevent a sharp rise in foreclosures over the coming months.

The program would allow borrowers with loans backed by the Federal Housing Administration and other federal agencies to extend the length of their mortgages, locking in lower monthly principal and interest payments. About 75% of new home loans are backed by the federal government, according to the Urban Institute.

Friday’s changes are aimed at homeowners who took advantage of so-called forbearance programs that allowed them to skip monthly payments for up to 18 months, but who can’t resume making those normal payments as that relief begins to expire.

Adding new modification options for struggling homeowners is “an important additional step to give people the opportunity to stay in their homes after they had a hardship during the pandemic,” said Bob Broeksmit, president and chief executive of the Mortgage Bankers Association.

About 1.55 million homeowners are seriously delinquent—meaning they haven’t made mortgage payments in at least 90 days, according to the mortgage-data firm Black Knight Inc. These borrowers, the bulk of whom have forbearance plans, may be most at risk of foreclosure in the coming months. They represent about 2.9% of the 53 million active mortgages, down from a high of about 4.4% in August and September 2020.

Borrowers who entered into forbearance plans early in the pandemic will begin to exit those plans in September and October, when Black Knight forecasts that about a million borrowers will still be seriously delinquent. Meanwhile, a national foreclosure ban is set to expire July 31.

Friday’s changes are the latest move by the Biden administration to prevent a repeat of the wave of foreclosures that followed the 2008-09 financial crisis. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau last month completed rules that restrict mortgage lenders from foreclosing on a property this year without first contacting homeowners to see if they qualify for a lower interest rate or some other loan change that makes it easier to repay.

The changes aim to reduce monthly payments by up to about 25%, an administration official said, adding they are designed to align with modification options already offered by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the government-controlled mortgage companies.

“If a reduction in monthly costs helps keep that borrower in their home until they are back on their feet, then it is a win for the borrower, policy makers, and Uncle Sam, as he owns the credit risk,” said Isaac Boltansky, director of policy research at Compass Point Research & Trading, which serves large institutional investors.

Many of the borrowers who are still postponing payments have FHA loans and typically have lower incomes and make smaller down payments than people with other government-backed loans, such as those guaranteed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Job losses during the pandemic have disproportionately affected low-wage workers, including employees of restaurants, hotels and shopping malls devastated by the stay-at-home economy.

The mortgage assistance is a small part of the multitrillion-dollar federal effort to help people and businesses withstand the economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, which included supplemental jobless benefits, grants to airlines, forgivable loans to small businesses and direct payments to households. Supporters say the mortgage relief is unlikely to encourage irresponsible borrowing.

“People don’t enter into mortgage borrowing with the notion that they can’t afford the payment,” Mr. Broeksmit said.

A separate, $47 billion federal program is aimed at helping tenants who can’t pay rent because of the Covid-19 crisis. State and local governments are struggling to distribute the money, however, leaving many people at risk of being thrown out of their homes when an eviction moratorium expires on July 31.

Research since the 2008-09 financial crisis has found that deferring mortgage payments, reducing interest rates or extending the term of mortgages—and thus reducing the monthly payments—are effective ways to aid homeowners short on cash.

Updated: 8-11-2021

Covid-19 Rent-Relief Program Marred by Delays, Confusion, Burdensome Paperwork

Treasury counts on more than 450 state and local governments and agencies to distribute nearly $47 billion in aid.

More than seven months after it was launched, the biggest rental assistance program in U.S. history has delivered just a fraction of the promised aid to tenants and landlords struggling with the impact of the Covid-19 crisis.

Since last December, Congress has appropriated a total of $46.6 billion to help tenants who were behind on their rent. As of June 30, just $3 billion had been distributed, though a senior official said the Biden administration hoped at least another $2 billion had been distributed in July.

While the program is overseen by the Treasury, it relies on a patchwork of more than 450 state, county and municipal governments and charitable organizations to distribute aid. The result: months of delays as local governments built new programs from scratch, hired staff and crafted rules for how the money should be distributed, then struggled to process a deluge of applications.

Often, tenants and landlords didn’t know money was available, and many of those who did apply had to contend with cumbersome applications and requests for documentation.

“It’s a recipe for chaos,” said David Dworkin, president and chief executive officer of the National Housing Conference, a Washington, D.C., affordable housing advocacy group. “And that’s what we’ve got.”

The program offers a contrast to other federal aid programs. For example, the Internal Revenue Service started sending $1,400 stimulus payments to American households on March 12, the day after President Biden signed Covid-19 relief legislation. A week later, the IRS said it had made 90 million direct payments totaling $242 billion—more than half the total amount authorized.

Data released by the Treasury Department shows that rental aid has begun to move faster, with more money distributed in June than in the previous three months combined. The Treasury is expected to release data for July around the middle of this month, according to administration officials.

The genesis of the program dates to the early months of the pandemic. In May 2020, Democrats in Congress proposed $100 billion in aid for the growing number of tenants who were out of work as a result of the pandemic and unable to pay rent—an amount that was later cut by more than half.

Democrats wanted the Department of Housing and Urban Development to oversee the program because it had experience distributing housing funds through an existing network of local partners. Republicans felt the Treasury would deliver the money faster, said Diane Yentel, president and CEO of the National Low Income Housing Coalition. Either way, grants would be disbursed on the state and local level.

Then-President Donald Trump signed the bill appropriating the first $25 billion in December. In March, Congress appropriated another $21.6 billion.

The program’s rollout was slow from the start. The New York state Legislature, for example, didn’t create a program to distribute the $2.7 billion allocated to the state until April, and the state didn’t open applications until June.

Tight screening requirements added to delays, housing advocates and attorneys said. Some local officials also said the initial guidelines from the Treasury during the final days of the Trump administration were unclear or confusing.

Tenants had to provide extensive paperwork to demonstrate need. That included apartment leases, documents to show job loss or loss of income, income levels for the previous year and proof of other benefits they might receive from the government. Many tenants were unable to comply because they didn’t have formal leases or earned cash wages.

Some programs reported being overwhelmed with applications or lacked the staff and resources to process them efficiently. Texas, for example, started with about 100 staff but eventually increased the number to more than 1,500, including contractors. Dozens of other programs have also turned to contractors for help.

Many tenants said they didn’t know they were eligible for aid or filled out forms incorrectly. In Texas, which has distributed more aid than many other programs, contractors began a mass text-messaging campaign this spring to reach people who may have mistakenly disqualified themselves when filling out applications.

Some landlords didn’t want to participate in the program, according to tenants, attorneys and local officials. Some landlords were unwilling to agree to temporarily not pursue future evictions against a tenant as a condition of receiving assistance. In Jefferson Parish, La., for example, landlords negotiated a proposed 90-day eviction ban down to 45 days.

Other landlords didn’t want to share required tax information. Many tenants, meanwhile, failed to complete forms or lacked access to computers and internet connections needed to complete applications.

The Treasury Department, under Mr. Biden, released new guidance in late February and again in the spring, among other things, to encourage local programs to pay money directly to tenants in certain cases, instead of just to landlords.

The guidance also encouraged programs to cut down on documentation required of tenants and landlords both. The new guidance allowed tenants to self-attest their need or allowed programs to use proxies in place of proof of earnings, such as the median income in areas where applicants lived.

Many programs ignored the guidance, research from the National Low Income Housing Coalition shows. As of August, only 1 in 4 were handing money directly to tenants. Just over half now allow some form of self-attestation from tenants instead of documents alone.

Many local governments were concerned that loosening the rules would expose them to fraud or charges they had squandered federal money.

Liz Bourgeois, a Treasury spokeswoman, said the department’s new guidance is helping boost the flow of money to renters and landlords. Tools to reduce paperwork, such as self-attestation, are “a common practice across federal and state programs and consistent with responsible management,” she said.

For now, tenants are protected by a national eviction moratorium, which has been extended five times and is now set to expire on Oct. 3.

Landlord groups are contesting the moratorium in federal court, saying the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention exceeded its authority when it first imposed it last September under Mr. Trump. Some states, including New York and California, have imposed their own moratoriums.

Meanwhile, many tenants are falling further behind on rent, and many landlords are being squeezed because they must continue to pay taxes, maintenance costs and other expenses.

“I think we need to rethink our model that we’ve put together here, because I don’t think the model is working as effectively as it could,” said Bob Pinnegar, president and CEO of the National Apartment Association, a landlord trade group.

Updated: 8-19-2021

Landlords From Florida To California Are Jacking Up Rents At Record Speeds

Soaring prices. Competition. Desperation. The dramatic conditions for U.S. homebuyers during the past year are now spilling into the market for rentals.

Landlords from Tampa, Florida, to Memphis, Tennessee, and Riverside, California, are jacking up rents at record speeds. For each listing, multiple people apply. Some renters are forced to check into hotels while they hunt after losing out too many times.

“Any desirable rental is going within hours, just like the desirable sales,” said Shannon Dopkins, a Realtor in Tampa. “One woman passed on a place that was beat up with water damage. Somebody else decided to rent it.”

After weakening early in the pandemic as the economy faltered and young people rode out lockdowns with family, the rental market is now seeing record demand. The number of occupied U.S. rental-apartment units jumped by about half a million in the second quarter, the biggest annual increase in data going back to 1993, according to industry consultant RealPage Inc. Occupancy last month hit a new high of 96.9%.

Rents on newly signed leases surged 17% in July when compared to what the prior tenant paid, reaching the highest level on record, according to RealPage.

High Cost Of Renting

Costs For New Leases Skyrocket As Apartment Hunting Gets Competitive

The gains reflect competition for a resource that’s getting ever-more difficult to obtain: somewhere to live. With prices soaring in the for-sale market, and bidding wars proliferating, would-be buyers on the losing end are being forced back into rentals.

At the same time, young Americans looking for their first apartment are competing with others who delayed plans because of Covid-19. Remote workers — and their high paychecks — are on the move to lower-cost areas. And small single-family home and condo landlords, tempted by high prices, are cashing out, leaving their tenants desperate for another place.

“The entire housing market is on fire, across the board from homeownership to rental, from high-end to low-end, from coast to coast,” said Mark Zandi, chief economist for Moody’s Analytics. “It’s a basic need but it’s increasingly out of reach.”

Eviction bans also are playing a role in keeping the market tight, because about 6% of tenants are normally forced to vacate each year. Zandi estimates the country’s shortage of affordable rentals is the worst since at least the post-World War II period.

Developers are adding new supply. But in the short run, the squeeze will have economic consequences because workers can’t easily move for jobs and will have less to spend on things other than housing. Soaring rental costs also are a contributor to the Federal Reserve’s inflation expectations.

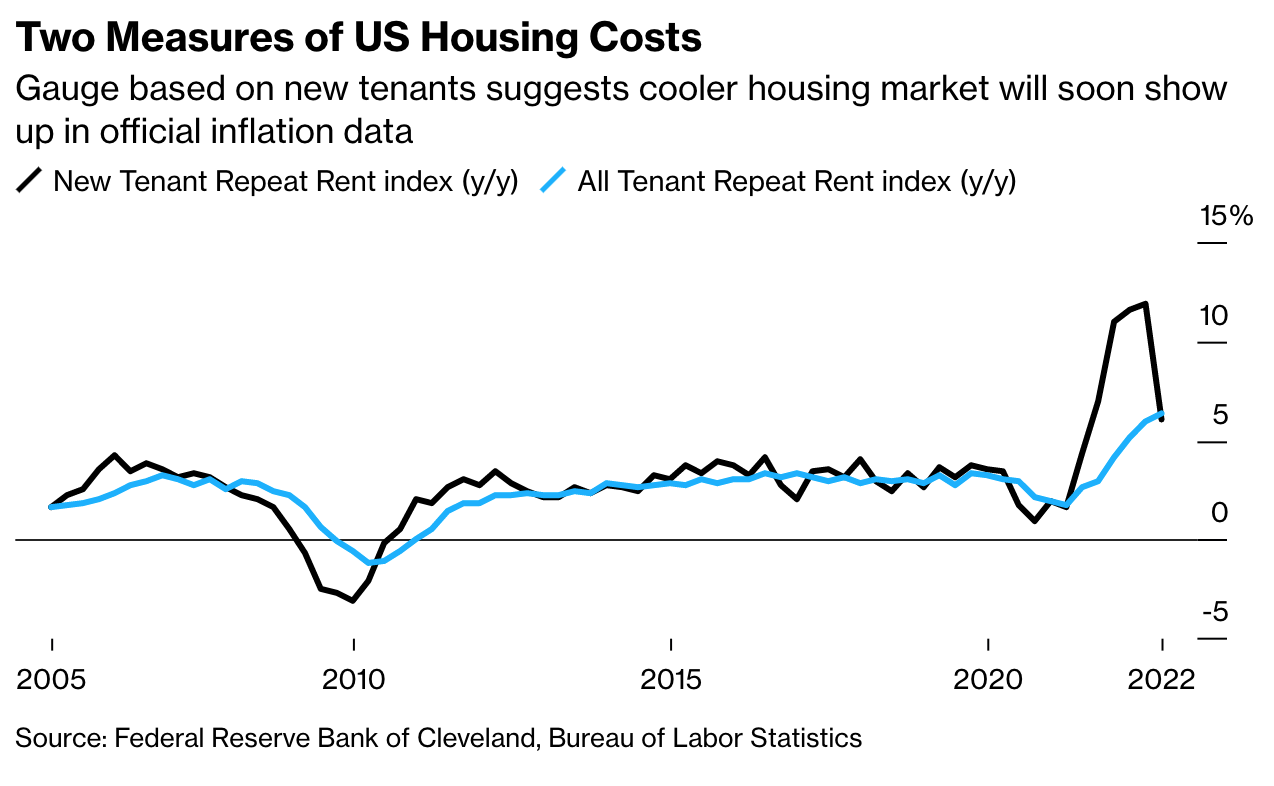

They may not yet be accurately reflected in some measures. Owners’ equivalent rent of residences, which makes up almost a quarter of the consumer price index, rose 2.4% in July from a year earlier. That figure “lags the reality” because it’s based on a survey of homeowner expectations about what their home would rent for, Zandi said.

Nowhere To Go

Rents are rising most for those who sign new leases. But even people renewing them are getting sticker shock. Carmen Santiago, a dental assistant who was paying $1,479 a month for a two-bedroom apartment in Tampa, gave notice to her landlord in March after the rent jumped by $300.

The mother of two then racked up more than $1,000 on non-refundable application fees that she handed to about 10 landlords, sometimes getting in line without even seeing the properties first. A couple days before her lease expired in June, Santiago took a last-ditch drive. She visited five apartment complexes, all filled. The sixth, a vast complex with 22 buildings, had one unit available.

The two-bedroom cost more than $1,900 a month, including a mandatory cable bill — more than Santiago would have paid if she renewed her old lease. She could hardly afford it but took it before it was gone.

“I didn’t know how hard it was to find something,” Santiago said. “Looking back, maybe I should have stayed.”

Dopkins, the Tampa rental agent, said she recently represented a woman who had to shelve her plans to move there for her job. After exhausting her relocation package on rental-application fees, the client is now planning to commute two-and-a-half hours from her home in Ormond Beach, Florida, and maybe stay in an Airbnb or hotel room in Tampa once or twice a week.

The soaring demand is most pronounced in Sun Belt cities that have seen an influx of arrivals from the pandemic. The Phoenix area had the country’s biggest increases in rents for single-family houses in June, with an almost 17% surge from a year earlier, according to data released this week from Corelogic. It was followed by Las Vegas, with a 12.9% gain; Tucson, Arizona, at 12.5%; and Miami, up 12.4%.

It’s a reversal from the pre-pandemic norm of tight housing in denser, pricier cities — places such as New York, Boston and San Francisco, which saw office workers flee during lockdowns. Those areas still have an overhang of inventory of high-end apartments aimed at white-collar professionals. Still, demand is picking up.

Higher Incomes

Renters now crowding the market have higher salaries, in part, because many of them, in normal times, would be buying homes instead. Migration away from the pricey locations also is driving up housing costs for locals, especially those in more affordable cities and in far-flung suburbs.

The average income for new lease signers in July hit a record of $69,252, according to RealPage, which captured data for professionally managed buildings. Year-to-date, their incomes shot up 7.5%.

“It’s always been hard to find a home if you have limited income,” said Jay Parsons, deputy chief economist for RealPage. “What’s crazy now is you can have a relatively high income and still have a hard time.”

Nicolle Crim, vice president of Watson Property Management’s Central Florida division, says she wished she had more to offer. But the for-sale market is so strong that owners are selling for big profits. As a result, Watson now manages about 4,000 single-family home rentals for individual owners, down by a third since the pandemic began, she said.

Even relatively sleepy areas such as Springfield, Illinois, three hours from Chicago, are experiencing shortages.

Landlord Seth Morrison said his only apartment listing attracted a couple dozen calls before he took it down.

“We have 270 units and we don’t have any open,” Morrison said. “In a city like Springfield, in a state like Illinois, to have this sort of demand is just crazy.”

Updated: 8-20-2021

Rising Rents Pose Risks To The Fed’s Inflation Outlook

Housing costs play an important role in inflation, which means that higher rents could put pressure on the Fed to raise interest rates.

The biggest wildcard for U.S. inflation over the next year doesn’t come from used cars or airline fares. Instead, it is housing.

Officials at the Federal Reserve and the White House have highlighted what many forecasters expect will be the temporary nature of elevated price readings stemming from the reopening of the economy following pandemic-related restrictions.

But the degree to which 12-month inflation readings fall back to the central bank’s 2% goal could rest on the behavior of rents and home prices. In recent months, housing-cost trends point to more persistent, rather than transitory, upward price pressures in the coming years.

Core inflation, which excludes volatile food and energy costs, rose 3.5% in June from a year earlier, according to the Fed’s preferred gauge, the personal-consumption expenditures price index. That was the highest rate of growth in 30 years. Rising prices over the April-to-June quarter largely reflected disrupted supply chains, temporary shortages and a rebound in travel—trends that came ahead of the latest virus surge caused by the Delta variant of the Covid-19 virus.

Economists at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. estimate that travel and other supply-constrained categories have added 1.2 percentage points to core inflation this year, and they forecast those contributions should wane to around 0.6 percentage point by the end of the year.

Contributions from rising rents and home prices could partially offset anticipated declines. In a June report, economists at Fannie Mae said they expected the rate of shelter inflation to pick up from around 2% in May to 4.5% over the coming years—and higher still, if house-price growth doesn’t cool off soon.

They forecast that by the end of 2022, housing could contribute 1 percentage point to core PCE inflation, the strongest contribution since 1990, and they forecast core inflation slowing to just 3% by then.

Housing inflation is important because it accounts for a hefty share of overall inflation—around 18% of core PCE inflation, and around one-third of a separate inflation gauge, the Labor Department’s consumer-price index.

Fed officials have held interest rates near zero since March 2020, at the beginning of the pandemic, and they are purchasing $120 billion per month in Treasury and mortgage-backed securities to provide additional stimulus. Just how fast and how far inflation falls back towards the Fed’s target one year from now could weigh heavily on how long to leave interest rates at zero.

Growth in rents slowed sharply during the pandemic as people stayed put or doubled up with family. Residential rents rose 1.9% over the 12 months through June, about half of the rate of growth seen in February 2020.

Before the pandemic hit, “we were treading water,” said Ric Campo, chief executive of Camden Property Trust, which owns and manages 60,000 apartment homes across 15 U.S. markets. Landlords lost any pricing power during the pandemic, as vacancy rates jumped.

But that began to change earlier this year as demand for new leases soared. “In March, it was like a light switch went off,” said Mr. Campo. “We have significant pricing power that we did not have a few months ago.”

Invitation Homes Inc., the largest single-family landlord in the U.S., raised rents by 8% in the second quarter, including 14% on leases signed by new tenants. Invitation reported occupancy of more than 98%, an extremely tight market.

Home prices, on the other hand, never missed a beat. They surged during the pandemic, boosted by a combination of low mortgage rates, pandemic-driven changes in home preferences, favorable demographics and low inventories of for-sale homes. Prices rose 16.6% in May from one year earlier, according to the S&P/Case-Shiller U.S. national home price index, up from around 4% in the year before the pandemic.

Government agencies don’t take soaring home prices directly into account when calculating inflation because they consider home purchases to be a long-lasting investment rather than consumption goods. Instead, they calculate the imputed rent, called owners’ equivalent rent, of what homeowners would have to pay each month to rent their own house.

Owners’ equivalent rents, which rose around 3.3% before the pandemic hit, cooled earlier this year, rising just 2% in the 12 months ended April.

Those measures tend to lag movements in home prices because leases are set for a year. The upshot is that leases signed one year ago, when landlords weren’t expecting to have much pricing power, are now coming up for renewal. As landlords pass along higher rents, annual inflation measures should soon start to pick those up.

“As the labor market improves and we have higher income and more household formation, that’s a lot of potential strength in rental inflation and in shelter inflation more broadly,” said James Sweeney, chief economist for Credit Suisse.

Even if recent eye-popping rates of rental increases can’t be sustained, housing analysts and executives see continued strong growth. Property tax increases from rising home values, for example, could be passed onto renters. Higher home prices could prevent more would-be buyers from becoming owners, which may keep pressure on rents.

Some of the housing market’s challenges reflect anemic new-home building that followed the 2008 bust. “We destroyed three-quarters of the supply chain, and a lot of resources left the business at the same time millennials were starting to emerge,” said Doug Duncan, chief economist at Fannie Mae. The result has been a shortage of houses and apartments in the places where many people want to live.

The pandemic, meanwhile, fueled new demand for housing. A recent study by Fed economists found that new for-sale listings would have had to expand by 20% to keep price growth at pre-pandemic levels.

A majority of economists surveyed by The Wall Street Journal in July projected inflation would decline to at least 2.2% by the end of 2022. If the conventional wisdom among professional forecasters about inflation proves wrong, housing would be a big reason why.

Updated: 8-25-2021

Only A Fraction Of Covid-19 Rental Assistance Has Been Distributed

Just $4.7 billion of almost $47 billion appropriated by Congress had reached tenants and landlords through July.

The U.S. program to help tenants and landlords struggling with the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic is still moving at a slow pace and has delivered a fraction of the promised aid, data released by the Treasury Department on Wednesday show.

Since December, Congress has appropriated a total of $46.6 billion to help tenants who were behind on their rent. As of July 31, just $4.7 billion had been distributed to landlords and tenants, the Treasury said.

Wednesday’s data show that rental aid has begun to move faster in some states, though July’s $1.7 billion reflected only a modest overall increase from the $1.5 billion distributed in June.

While the program is overseen by the Treasury, it relies on a patchwork of more than 450 state, county and municipal governments and charitable organizations to distribute aid. The result: months of delays as local governments built new programs from scratch, hired staff and crafted rules for how the money should be distributed, then struggled to process a deluge of applications.

Administration officials acknowledge the program has moved too slowly relative to the need. Still, they say it has provided nearly one million payments to households, including about 341,000 in July alone—an indication that it has provided meaningful relief to struggling tenants.

While 70 jurisdictions had distributed more than half of their initial allotment of rental assistance by the end of July, “too many grantees have yet to demonstrate sufficient progress in getting assistance to struggling tenants and landlords,” the Treasury said in a blog post accompanying the release of Wednesday’s data. Hundreds of thousands of aid applications are in the pipeline beyond those that have already been paid, Treasury said, citing public dashboards.

To allow for more time to distribute the money, the Biden administration this month extended a federal eviction moratorium until at least Oct. 3. It had expired at the end of July and had previously been extended several times.

The moratorium has protected millions of tenants but created financial hardships for some landlords unable to collect rental income they rely upon for their own livelihoods. Several states, including California and New York, have imposed their own eviction bans.

In June, the Supreme Court, on a 5-4 vote, declined to lift the national eviction moratorium, but Justice Brett Kavanaugh suggested the court wouldn’t look favorably on another ban if it weren’t approved by Congress.

A federal judge on Aug. 13 allowed the revived moratorium to remain in place, saying she didn’t have authority to block it despite misgivings about its legality. A group of property managers and real-estate agents who lodged legal objections to the new ban the day after it was imposed asked the Supreme Court last week to block the latest moratorium. A decision is expected in the coming days.

Tenant advocates and others involved in distributing the aid say demand for affordable housing has been elevated for years and intensified during the pandemic.

Joshua Pedersen, senior director of United Way Worldwide’s 211 hotline telephone service, said it connected about 6.1 million callers to housing and utility resources in 2020, up 20% from 5.1 million the year before. He said demand tends to surge whenever there is a change in the status of the eviction moratorium.

Biden administration officials have prodded states and localities to move faster to distribute rental assistance, issuing guidance intended to reduce documentation for tenants and landlords and expedite approvals. On Wednesday, the Treasury released additional guidance meant to further reduce processing delays.

The administration has also highlighted jurisdictions that have succeeded in distributing more aid than many other programs.

Treasury officials last week pointed to steps taken by Prince George’s County, Md., to distribute the bulk of its $27 million. The county is beginning to distribute assistance directly to tenants in cases where landlords aren’t willing to participate in the application process. All eviction notices also now include information about applying to the rental-assistance program.

But other programs are lagging, including some large ones. The program run by the Florida state government was awarded about $1.6 billion in aid, but distributed less than $20 million through the end of July, according to the Treasury.

However, several local programs in that state, such as the one run by Miami-Dade County, distributed much larger shares of their funding, Treasury figures show. A spokeswoman for the Florida program said it had distributed more than $31 million as of Aug. 24. The spokeswoman said more than 25% of tenant applications still lack sufficient information to be approved.

The state of New York said this week it had distributed more than $200 million of its more than $2 billion in available assistance and still has a backlog of more than 100,000 applications.

Emmanuel Yusuf, 77 years old, is a retired photo technician in Bronx, N.Y. He is eight months behind on rent and mostly lives on Social Security assistance, he said. Before the pandemic, he made extra money taking tourist photos in Times Square.

Mr. Yusuf said he applied for rental assistance more than six weeks ago, but has yet to be approved. “When we have funding and somebody is just sitting on it, it blows my mind,” he said.

The New York program requires both tenants and landlords to submit separate applications. Verifying both ends has been an often complicated and time consuming task, a spokesman for the program said.

The program has provisionally approved 46,000 tenants for aid, but it could be weeks before those tenants’ applications are matched with documents sent by their landlords and money is paid out. The state added 350 more staff members to handle the load.

“We will continue to make extraordinary efforts to ensure New York’s program provides more timely assistance,” said Michael Hein, commissioner of the state office that is running New York’s rental-aid program.

Updated: 9-11-2021

Real Estate ‘Love Letters’ Spark Concern Over Racial Bias

Home buyers’ personal notes to sellers offer an emotional appeal in a competitive market—but could cause sellers to run afoul of fair housing rules.

When Christina and Alexander Vaughan looked to buy a home this spring, the first open house they attended drew more than 20 families. The couple ultimately bid on three homes, losing on each one.

On their fourth offer, for a four-bedroom house in Fishers, Ind., they wrote the sellers a personal letter. They were first-time buyers, the letter said, and it noted that Mr. Vaughan and one of the sellers both attended Purdue University. Their offer was accepted over higher competing bids.

“Because that was their first home, they wanted to give it to somebody else” who would be a first-time homeowner, Mr. Vaughan said of the rationale the owners gave.

Prospective buyers for years have penned these personalized notes—affectionately known as “love letters”—to introduce themselves to a home seller and make an emotional appeal. The letters can provide the buyer a competitive edge, and rarely has the U.S. housing market been more competitive than it is today.

But in recent months, love letters have come under greater scrutiny for possibly enabling discrimination. Some worry that a seller could violate the federal Fair Housing Act by choosing a buyer based on a protected class, such as race, religion or nationality. The law includes seven protected classes, and some states and localities have additional protected categories.

The National Association of Realtors put out guidance in October recommending that its members not draft, read or deliver love letters written or received by clients. Some state Realtor associations have also put out similar guidance, including in California, Arizona and Ohio.

Typically, home sellers who receive multiple offers choose a buyer based on offer price and contract terms. Love letters can give the sellers additional information about a potential buyer’s identity, including race or whether a buyer has children. The risk for a seller is that they could exercise explicit or implicit bias by choosing a buyer based on this information, violating fair housing rules.

In June, Oregon became the first state to pass a law requiring sellers’ agents to reject love letters and photographs provided by buyers.

“It’s a discriminatory practice that needs to be addressed,” said Oregon state Rep. Mark Meek, who proposed the law and works as a real-estate agent. “A lot of sellers make decisions off of these letters, but is it right?”

The reassessment of love letters is part of a broader effort within the real-estate industry to combat a history of discrimination and increase homeownership rates for nonwhite households. White households in the U.S. had a homeownership rate of 74.2% in the second quarter, compared with 47.5% for Hispanic households and 44.6% for Black households, according to the Census Bureau.

NAR’s president apologized in November for the organization’s past policies that contributed to residential segregation, such as allowing members to be excluded based on race. The Department of Housing and Urban Development has also made fair housing a priority under the Biden administration. HUD and the Federal Housing Finance Agency formed an agreement last month to share resources related to enforcing fair housing rules.

Bryan Greene, vice president of policy advocacy for NAR, said he isn’t aware of any lawsuits against home sellers or complaints filed with HUD alleging discrimination based on a love letter.

“It would be very difficult for any consumer to prove they were denied housing because someone else sent the seller a love letter,” he said. “It’s certainly possible, but it’s not necessarily something that the law can get to.”