How Bitcoin Can Help In Paying Universal Basic Income (#GotBitcoin)

The utopian idea of universal basic income — which has been with humanity for at least half a millenia — can become real with digital currency. How Bitcoin Can Help In Paying Universal Basic Income (#GotBitcoin)

Due to the crisis caused by COVID-19, millions of people have lost all or part of their income. To support them, governments have been giving out money to victims. Is it possible to make this practice permanent? And if so, why will we need state digital currencies?

Related:

Families Face Massive Food Insecurity Levels

Ever-Growing Needs Strain U.S. Food Bank Operations

Dollar Stores Feed More Americans Than Whole Foods

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced the United States, Canada, Japan, Russia and many other countries to print large budget reserves and to start helping people with direct cash payments. Such measures have, again, led the world to talk about the idea of an unconditional or universal basic income, otherwise known as UBI, an idea that Thomas Moore put forward in his novel Utopia in 1516. Its essence is that every citizen has the right to regularly receive a certain amount from the government without fulfilling any conditions and can spend this money at their discretion.

The introduction of UBI experiments began long before the coronavirus pandemic. One example is in Alaska, where a similar system, dubbed the “Permanent Fund Dividend,” has been operating since 1982. Once a year, every resident of the state receives a certain part of the profit from the local oil industry. In 2019, it was $1,606 dollars, and in the most “profitable” year of 2015, it was $2,072. Another example is in Namibia where about 1,000 residents of two villages received 100 Namibian dollars each month during 2008 to 2009. Also in Finland, a UBI system was tested from 2016 to 2017 in which 2,000 nonworking citizens received 560 euros each month.

Today, 71% of Europeans support the idea of UBI. Pope Francis has encouraged such payments. Andrew Yang, a former 2020 U.S. presidential candidate, made UBI the focus of his campaign and created the Humanity Forward fund. Recently, the organization received $5 million from Twitter founder Jack Dorsey to give out money in the form of 20,000 microgrants of $250 each.

However, many point to the imperfections of the UBI system and believe that in the world of traditional finance, it can bring more problems than benefits. That said, things might be different if you look at the situation from a different perspective. The development of crypto technologies opens up new opportunities for introducing UBI, changing relations between the state and society and creating a more just world.

What Is Wrong With The Idea Of UBI?

One of the main arguments from opponents of UBI is that if the state distributes money to all citizens, people will work less, which will negatively affect the economy. It may also lead to an increase in the consumption of alcohol and other harmful substances, especially among the poorest segments of the population. However, experiments that have been performed refute these stereotypes.

Researchers found that in Namibia, UBI recipients began to eat better, their children were more likely to attend schools and crime rates decreased. In developed countries — for example, Finland — UBI recipients are more satisfied with their lives, more positively perceive their economic situations and, at the same time, do not try to avoid employment. Moreover, the reduction of anxiety about making money for food leads to the development of creative skills, which helps to find new areas of activity.

To realize a fair distribution of funds in the world of traditional finance, we need a simple system of interaction between all participants, which must take into account many factors — from inflation and possible corruption to the characteristics of migration flows. As a result, for a country with a population of 300 million people located in five different time zones, the cost of paying a UBI in the amount of $1,000 would be from $10 to $130 for each $1,000 paid.

Today, however, there is a technical solution that can help the state build an effective payment system for UBI with minimal costs.

How Bitcoin’s Blockchain Will Help

Using Bitcoin’s Blockchain and it’s accompanying transparancy, the distribution of UBI occurs inside a peer-to-peer information system, the participants of which will be:

The State: It carries out issuance, (using smart contracts) direct transfer of UBI payments to electronic wallets of citizens, control of cash flows within the system, and blocking of suspicious transactions, including the purchase of certain goods and services.

Citizens: They Spend The Money Received.

Organizations: UBI payments are accepted for payment from citizens, then they use the accumulated to pay taxes and/or convert to other currencies, which they then use for any traditional payments.

The blockchain will allow for the instant and reliable exchange of data necessary for calculating the value of a UBI payment, as well as to control its timely payment to each person. In order to avoid fraud and attempts to obtain a payment several times decentralized identification along with smart contracts will be utilized.

Thanks to the absolute transparency and automation of processes due to smart contracts, the technologies behind Bitcoin’s Blockchain can solve the main problems that today interfere with the technical implementation of the database technology.

Here Are Some Examples:

1. Inflation. When calculating the value of UBI payments, it is important to constantly monitor the change in the purchasing power of money, taking into account the actual consumer basket. Today, data for calculating the consumer price index is manually collected; that is, workers go shopping and write out prices. It is slow and expensive.

Solution: Using Bitcoin’s Blockchain will make the collection of information almost instantaneous, increase the objectivity of the data and eliminate errors in the calculations. Blockchain also allows you to change the position of goods and services for monitoring based on actual consumption by the population.

2. Different Living Standards. The same goods and services may have different prices and different densities in the consumer basket. When using “ordinary” fiat money for UBI payments, the issue will be resolved using simple averaging, which can lead to significant distortions of the overall picture. This problem is especially typical for nations with a large territory and a significant difference between urbanized and agricultural/fishing areas.

Solution: UBI, issued in bitcoin, allows not only to take into account changes in the cost of goods but also to create a “basket of subcurrencies.” The cost of goods in each region can be considered separately and then reduced to a common denominator through conversion rather than averaging. As a result, people will be able to buy an identical amount of goods and services, regardless of the real standard of living in a particular region.

3. Corruption. In regions with a weak law enforcement system, the payment of UBI in traditional currency can lead to an increase in corruption.

Solution: All transactions will be recorded on the blockchain, and it will be possible to track the entire path of the transaction from the moment of issue. Such transparency of payments leaves no room for corruption.

4. Immigration. With the current level of globalization, people often move to countries with more developed economies. If UBI is paid to all citizens, even those who do not reside in the territory of the donor state, this provokes even greater inequality: Those who leave are twice winners. On the other hand, if UBI is not paid to visitors who are legally working in the territory of the donor state, the welfare gap between them and the citizens of the country widens. In both cases, UBI can provoke an increase in social tension and affect migration flows.

Solution: Bitcoin’s Blockchain makes it possible to make UBI payments selectively — taking into account the main geolocation of the tax resident. For example, only to those who contribute to the creation of value added in the territory of the state or who have other legal grounds for receiving funds. For example, in the case of minors, pensioners, etc.

5. Costs. Within the framework of the traditional financial system, administering direct, regular, simultaneous settlements with millions of people is difficult and expensive. This requires the payment of many staff and the cost of operating an information technology banking infrastructure. It is also necessary to take into account additional costs during IT development and operation of systems: They must have an excess supply of productivity, which is necessary at peak load times.

Solution: Bitcoin’s Blockchain technology automates all processes related to accounting, routing, cash charging, etc. The total transaction cost — from the issuer to the electronic wallet — in the case of the state blockchain, becomes much cheaper than in the traditional fiat payment infrastructure. Custom wallets can be created through public application program interfaces, which will make them free for both the state and the public. In this case, the state will retain only the certification function of this software.

6. Relevance of Statistics. Today, businesses are forced to prepare many reports for various departments, which then turn into summary data for industries, regions and the country as a whole. Such a process requires a lot of labor, time and money, but its effectiveness is extremely low, as the final statistics are sent to the treasury a few months later when they could be, already irrelevant or at least outdated.

Solution: With Bitcoin’s Blockchain, statistics will become instant, accurate and reliable. When a person pays with UBI funds from a Bitcoin wallet, the information reflected in the cash receipt is sent to the state settlement centers in real time.

Accurate data on the dynamics of sales in the assortment context will make it possible to form informed plans for the production of goods and a price policy, and to make timely adjustments in the field of remuneration and social security.

Final Thoughts

States can become an effective tool for the economic interaction of the state and citizens on the basis of other, more equitable relations. Three years ago, in a speech to Harvard graduates, Mark Zuckerberg called for the use of UBI to give people the opportunity to try new things, make mistakes and look for their callings. And today, when there are so many restrictions in the world, we have technologies that can give each person more freedom and security. This must be used, making UBI an ideal tool to empower the individual and help create a better world.

Updated: 9-29-2020

Cities Experiment With Remedy For Poverty: Cash, No Strings Attached

Guaranteed income comes without work requirements; some worry about work disincentive, high cost.

Last year, Stockton, Calif., embarked on a civic experiment. For 18 months the city would send $500 a month to 125 randomly selected households in low-income neighborhoods. Researchers would compare the effect on participants’ health and economic situation to that of residents who didn’t get payments.

The $3.8 million experiment is the brainchild of Stockton’s 30-year-old mayor, Michael Tubbs, made possible by the Economic Security Project—a group co-founded by Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes that funds guaranteed-income projects—and other donors.

Stockton is at the forefront of a rethinking of the American safety net among some academics and public officials, particularly as the coronavirus pandemic has revealed the financial fragility of many households. They say the best way to combat poverty is to give cash to poor households, trusting them to make their own best decisions.

The idea is related to universal basic income, popularized by former Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang. Whereas UBI involves regular payments to everyone regardless of income, Stockton’s experiment targets poor neighborhoods.

If implemented nationwide, guaranteed income along the Stockton model would represent a significant expansion of the safety net and one that isn’t conditional on working or looking for work. Food stamps, welfare, Medicaid, the earned-income tax credit and unemployment compensation all include some form of work requirement.

Stockton’s payments have helped people affected by the recession cover their bills, said Mr. Tubbs. More than half of the funds have been spent on food and utilities, according to preliminary findings. One recipient, 64-year-old Magdalena Taitano said she used the money to pay for medicine and the electric bill and to buy a car after her old one was totaled in a crash.

“What we found is that you can trust people to make good decisions,” Mr. Tubbs said.

The program was originally set to end in July but new donations extended it until January.

Critics point to several potential drawbacks.

First, if only people below a certain income receive the transfers, and aren’t required to work, they may hesitate to take a job, or a higher-paying one, since they would then forgo the payment. The result could be less work and less economic dynamism.

“Giving money to people, no strings attached, changes behavior,” said Douglas Besharov, a professor of public policy at the University of Maryland. “We create incentives we don’t like or want.”

Studies of universal cash transfers in Alaska and among the Eastern Band of Cherokees in North Carolina found no negative effect on work. A study of lottery prizes—which are analogous to unconditional cash transfers—found that winners of relatively small amounts didn’t change how much they worked but winners of larger amounts did.

That disincentive could be mitigated by phasing out payments more slowly as other income rises, said Jesse Rothstein, an economist at the University of California, Berkeley.

“There’s not really a way to design that phaseout without creating some disincentive of people to work,” he said. “If it’s well-designed, you wouldn’t get a big effect.”

Second, a national guaranteed income would carry a steep price tag. Giving $10,000 a year to individuals earning less than $20,000 or married households earning less than $40,000 with a long phaseout period would cost roughly $1.2 trillion, or nearly 5.9% of annual economic output, according to University of Maryland economist Melissa Kearney and Magne Mogstad, an economist at the University of Chicago.

That is more than the federal government spent on Social Security in 2019. It would have to be funded either through an increase in the budget deficit, when the national debt is already headed over 100% of gross domestic product; much higher taxes; or sharp cuts to spending.

“Given how expensive it would be and given the political realities, it’s unlikely we would just be doing this on top of [existing] government safety-net programs,” said Ms. Kearney. “Then the question is, OK, which safety-net programs would you replace?”

It is hard to imagine Congress enacting guaranteed income anytime soon. But its approval of one-time payments of up to $1,200 for most Americans in March for coronavirus relief suggests openness to unconditional assistance, at least in some circumstances.

This Covid[-19] economy has just yanked the rug out from our communities across the country in a way we’ve never experienced before

— Saint Paul, Minn., Mayor Melvin Carter

“There hasn’t been a lot of hand-wringing about whether people might use the $1,200 checks to buy cigarettes or something like that,” said Ed Dolan, an economist at the Niskanen Center.

It is unclear whether Stockton’s initiative has affected people’s willingness to work. But since it is intended to be temporary, it might change behavior less than a permanent program.

Inspired by Stockton’s experiment, roughly two dozen mayors from cities as large as Los Angeles and as small as Holyoke, Mass., have signed on to a newly formed coalition advocating for a nationwide guaranteed income.

“This Covid[-19] economy has just yanked the rug out from our communities across the country in a way we’ve never experienced before,” said Melvin Carter, mayor of Saint Paul, Minn., and a member of the group.

Mr. Carter said his city is working with donors to set up its own experiment similar to the one in Stockton.

Other initiatives have sprung up in recent years. Santa Clara County in California gives $1,000 a month for a year to young people leaving foster care. Hudson, N.Y., is launching a pilot program—partly funded by a nonprofit founded by Mr. Yang—to give $500 a month to randomly selected residents for five years.

For now, most of the experiments are relatively small, temporary and reliant on philanthropy. But “each of these experiments gives you a few more data points,” Mr. Dolan said.

Updated: 11-22-2020

Rising Star Mayor Who Championed Guaranteed Income Loses Hometown Race

Michael Tubbs pushed an ambitious agenda for Stockton, California. Four years later, a blog campaign against him fanned criticism of his national profile.

Stockton Mayor Michael Tubbs came into elected office on a high in 2016, winning 70% of the vote. Since becoming mayor, he put himself and his economically distressed hometown on the national map through his advocacy for progressive programs, including one of the first guaranteed income experiments in the U.S.

The subject of documentaries and Daily Show appearances, particularly as cash assistance programs gained momentum during Covid, Tubbs had been a rising political star.

But this November, Tubbs’ star fell in Stockton: The 30-year-old mayor conceded the race to his Republican challenger, Kevin Lincoln, who was leading by 12 percentage points (though the tally isn’t final yet).

What changed? Some residents resented his national profile, viewing him as more committed to his own reputation than to giving attention to the city. Others objected to his progressive policies, choosing instead the candidate who was supported by the local police union and ran on a campaign to reduce homelessness and make government more efficient.

But Tubbs and his supporters also point to another factor that has become an increasingly common suspect in national and local races alike: A targeted misinformation campaign, in this case led by a local blog called the 209 Times.

The blog has published damaging and often misleading or false articles about the mayor, including misstating the impact of a scholarship program he spearheaded and inflating the amount of funding the city had received to address homelessness.

“I think when you spend four years unchecked with no real counter, just blatantly making things up every single day, there’s an impact,” said Tubbs of 209 Times’ influence. “I wish I had a crystal ball to foresee that, but I was too busy doing the work.”

Motecuzoma Patrick Sanchez, one of the founders and a writer for the blog, rejects the idea that any of his stories were fabricated. But he gladly takes responsibility for eroding the community’s trust in Tubbs.

He dubbed the unofficial anti-Tubbs campaign “Operation Icarus,” after the Greek myth about the boy who flew too close to the sun. “The more he buys into his own sense of political celebrity, the more he’s neglecting the fundamentals of why he was elected,” said Sanchez. “All we have to do is show the community what he’s doing and what he is not doing.” (Sanchez ran for mayor in the primary but lost to Lincoln.)

Since its launch in 2017, the 209 Times has amassed nearly 100,000 followers on Facebook and 119,000 followers on Instagram. Its website gets about 100,000 hits a month. In a city of 300,000, that’s a substantial reach. The Los Angeles Times reported that the blog’s influence grew in Stockton in the vacuum left by the city’s local paper, The Record, which has been depleted by layoffs and budget cuts.

“A lot of people are susceptible to this information without a strong local newspaper,” said Daniel Lopez, a spokesperson for Tubbs. “In replacement of that, people have been getting their news online through comments, through shares.” And what sticks, he says, are the negative stories that drum up controversy.

Not all of voters’ misgivings about the mayor were fanned by the site’s biases. While Tubbs made it his goal to reach out to “people that feel they’re disenfranchised by the system,” some residents of the city’s wealthier North side feel that they’re being ignored, said Kurt Rivera, a News reporter for ABC10 Sacramento who grew up in the city and moved back as an adult to cover it.

Eviction protections passed unanimously through city council relieved renters but alienated landlords. An unfounded fear that affordable housing would replace a golf course on the North side of town inspired homeowners to band against Tubbs. And advocacy for some criminal justice reforms have splintered the electorate.

Nationally, Tubbs has drawn a much warmer shade of attention. He grew up in Stockton, and, after graduating from Stanford University and spending a stint interning at the White House, returned in 2012 to run successfully for city council. Winning the mayoral seat in 2016 at 26 years old was a historic victory, making Tubbs the city’s youngest and first Black mayor.

Once in office in January 2017, Tubbs formed the Reinvent Stockton Foundation and launched a series of progressive programs, most famously the first major guaranteed income pilot in the U.S. Funded by private donations, the Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration has provided $500 a month to 125 residents for nearly two years.

It’s set to end in January, but Tubbs has been leading a national effort to bring similar experiments to other cities — and next year, places like Pittsburgh, Compton and San Francisco plan to start their own pilots.

The Reinvent Stocktown Foundation also runs the Stockton Scholars program, which gives scholarships to college-bound high schoolers. The program received a boost with a $20 million donation from Snapchat founder Evan Spiegel’s philanthropic fund.

In all, between private donors and government grants, Tubbs has brought in more than $100 million to the city over his four-year term.

Tubbs’ story and accomplishments inspired an HBO documentary, “Stockton On My Mind”; as part of its promotion this summer he appeared on national television shows and did interviews with celebrities like Killer Mike. He endorsed Michael Bloomberg’s 2020 bid to become the Democratic candidate for President, and appeared at campaign events on the former New York mayor’s behalf.

(In 2018, Tubbs also graduated from a Harvard mayoral training program sponsored by Michael Bloomberg, founder and majority owner of Bloomberg LP, the parent of Bloomberg CityLab. The next year, Bloomberg’s philanthropic foundation donated $500,000 to a Stockton education reform group.)

All those national commitments may have distracted Tubbs from the issues on the ground, critics say — an attack that’s similarly been lobbed at other charismatic mayors with higher ambitions, like Cory Booker, Pete Buttigieg and Eric Garcetti.

“When people see him in San Francisco or in Washington or in New York they feel that he’s neglecting his own people here,” said ABC10’s Rivera.

“This guy thinks he’s a big shot nationally,” said Sanchez. “While he’s out on TV talking about macroeconomics, the community is struggling with rampant violent crime, with a homeless crisis that has increased 200%.”

Experts note that because of Stockton’s governance structure, the city manager rather than its mayor actually controls a lot of its operations and policymaking. The role of the mayor is as an ambassador, a fundraiser and a go-between with other government entities and representatives.

Still, there are problems that continue to plague Stockton and have only been made worse by the pandemic. Homicides dropped 40% in 2018, but as of October, the rate was up 40% from last year, mirroring the trajectory of many cities affected by the economic distress of the pandemic. Total rates for violent and property crimes, meanwhile, have dropped nearly 20% this year.

The city had been recovering from the unemployment spike it experienced after the 2008 recession, but the coronavirus has left 11.4% of the population jobless. Stockton’s rate of homelessness has tripled between 2017 and 2019, and its poverty rate is about 20%.

As to the impact of global and national media appearances, Lopez and other supporters say they served to elevate Stockton as much as Tubbs.

For years, the city was known as the largest to declare municipal bankruptcy in the U.S., or the one with the most foreclosures, or simply the most “miserable.” With Tubbs in charge, Stockton’s star rose, too: No longer neglected, it had become a small city to watch.

Funders with deep pockets may be less wary to take a chance on Stockton, Tubbs told Bloomberg Businessweek. Steadying the city’s financial health was also a priority: Stockton will end the year with a $13.1 million budget surplus.

For the community groups Tubbs worked with — like the 125 SEED participants who received monthly cash payments, and the students who got the first round of college scholarships — his rising profile was a reflection of the life-changing effect his tenure had.

“I personally am astounded, for lack of a better word. I am perplexed, it doesn’t make sense to me,” said Janae Aptaker, the director of the Stockton Scholars Program & Strategy, of Tubbs’ loss. “As somebody who works at the foundation I understand the depth of the work that we’re doing. It’s driven by the needs of the community and some of our most needy folks in the community. It is kind of heartbreaking.”

“It’s a sad commentary on information, misinformation, education and the need for an informed citizenry.”

Coverage by the 209 Times of the Stockton Scholars program is one example of how the blog has misrepresented Tubbs’ record.

The blog claimed that the initiative has only given out $44,000 in scholarships to kids, using as its proof a 990 form from 2018, when the program was in its pre-launch phase and only giving out mini-grants.

As of this year, the foundation has spent $750,000 on scholarships of up to $1,000, for 879 students who are eligible to keep receiving grants for four years, according to the foundation. Another 1,420 students are eligible this year, and the foundation plans to support a total of at least 10 graduating classes.

But the articles have led school administrators and counselors to doubt the program, said Aptaker; she’s heard of students who were “unsure if they should apply because they’re not sure it’s real.”

Stories like this spread fast. “It also begs the question: What was so scary, what was so threatening, what was so bad about giving kids scholarships? Or putting the city in a healthy fiscal position?” said Tubbs. “It’s a sad commentary on information, misinformation, education and the need for an informed citizenry that’s given accurate information to make choices.”

Another misleading narrative pushed by the 209 Times is that the city of Stockton had been given $60 million to address homelessness in the city, without results to match. The city has only been given $6.5 million to address homelessness, according to the mayor’s office. (Sanchez says the $60 million figure was cumulative and included money allocated at the county level.)

“The idea that Stockton alone would receive $60 million is outrageous,” Lopez wrote in a statement. “But nevertheless, 209 Times readers, influenced by their fake news, regularly ask where the money went.”

Most recently, articles alleged Tubbs was in on a plan to build a new shelter for unhoused people from within the county and across the state at the San Joaquin County Fairgrounds. Putting emergency services at the fairgrounds had been discussed as part of a homeless task force brainstorming session.

But, Tubbs, City Manager Harry Black, and representatives from multiple state agencies said there was no “secret plan” to create such a regional homeless shelter. The Record ran a story saying as much, but it was too late, Lopez said. Readers believed it.

Sanchez also used the 209 Times to take issue with things like Tubbs spending city money to refurbish City Hall and buy a high-tech video camera, and his use of his own foundation to raise funds for the city. The blog fanned criticism of the city’s Advance Peace program, in which violent offenders are given mentorship and stipends to address poverty as a root cause of crime, saying it disrespected the families of victims.

The controversy over turning a golf course into housing — which ended in Tubbs saving the green and city resources by leasing it out to a private developer — and a debate over whether to cut district funding for school police were particular flashpoints, said Lange Luntao, the executive director of the Reinvent Stockton Foundation.

“Those two issues in my mind really exposed the fact that places like Stockton, while they are in the state of California, are still deeply conservative places,” said Luntao, who has also been unseated from his position on the school board. They were also “proxies for racism,” he said.

Tubbs says he’s experienced “racialized” undertones from his opposition since his city council days, as he spoke his mind and refused to be “docile” as a young Black man. “We actually did things, we actually moved things, we actually changed things,” he said. “And there’s a price that comes with that.”

Tubbs’ opponent is also a candidate of color, a Black and Latino man ten years Tubbs’ senior who, like Tubbs, grew up in Stockton. It is primarily his politics and his age that provide a contrast. Although the race is technically nonpartisan, Lincoln is a Republican who ran on a platform of addressing homelessness, increasing public safety and expanding civic engagement.

The pastor, former businessman and ex-Marine has said he does not support sanctuary city policies, has the endorsement of the police and firefighters’ unions, and in May, advocated for Stockton businesses to open up from Covid lockdowns, saying the state had “crushed the curve.”

“I believe that Mayor Tubbs came in with a huge mandate that I feel he may have squandered,” said Lincoln. Tubbs raised $662,842 for his campaign, much of it from outside the city. But Lincoln ran a successful local media blitz, raising a little over $299,000 and papering the city with flyers.

The foundation Tubbs started, Reinvent Stockton, is privately funded and run, and will live on no matter the mayor. But while Lincoln says that he hopes to continue to support some programs launched under Tubbs, like the Stockton Scholars fund, others will “have to die on the vine.”

Lincoln is not affiliated with the 209 Times, and was actually an early target of the site during Sanchez’s short-lived mayoral run. When the blog invited Lincoln to participate in a debate in January, he released a Youtube video explaining his decision not to attend. “I do not condone any person or media outlet using tactics that divide,” he said at the time, although he’s tempered his criticism in interviews after the primary.

Sanchez is quick to say he is not a “traditional” journalist but rather a “guerilla” one. “We have to do a lot of translating, we connect the dots,” he said. “I designed something that’s brought things like politics and other issues to the masses in a community that was rife with apathy.”

Stockton ranks 99th of the largest 100 cities for college attainment, with only around 18% of residents age 25 and up attaining a bachelor’s degree or higher.

“In general, We’ve seen that when a social media outfit like this gets set up in a civically under-educated community, it can lead to confusion and doubt,” said Reinvent Stockton’s Luntao.

As Stockton’s new leader, Lincoln may soon find himself the subject of the local kingslayer’s scrutiny.

“If he starts getting out of line, we’re willing to hold him accountable the same way,” said Sanchez.

Updated: 1-4-2021

2021 Will Be The Year Of Guaranteed Income Experiments

At least 11 U.S. cities are piloting UBI programs to give some of their residents direct cash payments, no strings attached.

Giving people direct, recurring cash payments, no questions asked, is a simple idea — and an old one. Different formulations of a guaranteed income have been promoted by civil rights leaders, conservative thinkers, labor experts, Silicon Valley types, U.S. presidential candidates and even the Pope. Now, it’s U.S. cities that are putting the concept in action.

Fueled by a growing group of city leaders, philanthropists and nonprofit organizations, 2021 will see an explosion of guaranteed income pilot programs in U.S. cities. At least 11 direct-cash experiments will be in effect this year, from Pittsburgh to Compton.

Another 20 mayors have said they may launch such pilots in the future, with several cities taking initial legislative steps to implement them.

“We are at a moment right now where city leaders, residents policymakers, and activists are all looking for big ideas to begin to chip away at some glaring structural problems in our systems and institutions,” said Brooks Rainwater, senior executive and director of the National League of Cities’ Center for City Solutions.

“This new wave of pilots is different because of the groundswell of support for guaranteed income we are seeing in cities across America.”

These programs are often called UBI, for Universal Basic Income, but with each distributing monthly payments to just some households, they aren’t yet truly universal, and there’s disagreement over whether they should be. Instead, they’re “unconditional,” a contrast to many existing government programs that tie benefits to work requirements, or set parameters on how recipients can use the money. Still, the idea isn’t to replace the existing safety net, but build upon it.

The current wave of city programs was catalyzed in the U.S. with a two-year pilot in Stockton, California, that began in February 2019. Originally slated to sunset in the summer of 2020, philanthropic support allowed the program to continue for six more months during the Covid-19 pandemic.

After gaining a national profile for helping to initiate the program, former Stockton Mayor Michael Tubbs was voted out of office this November — but not before launching a coalition of local leaders called Mayors for a Guaranteed Income, which he will continue to lead in 2021.

“We need a social safety net that goes beyond conditional benefits tied to employment, works for everyone and begins to address the call for racial and economic justice through a guaranteed income,” Tubbs said in a statement.

In the short term, the goal of the nearly 30 mayors in the coalition is to run guaranteed income experiments. The ultimate aim of the mayors coalition is to pass a federal guaranteed income program.

Every city that joins is eligible for $500,000 in pilot funding; they’ve partnered with the University of Pennsylvania School of Social Policy & Practice to produce research reports, and will share best practices throughout.

The effort has gained high-profile philanthropic supporters, including Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey, who donated $3 million to the group in July and another $15 million in December.

The results will be supplemented by other experiments in global cities, past and present. The largest such program is in Maricá, Brazil, where tens of thousands of residents below the poverty line are currently receiving monthly payments.

Although the U.S. programs announced thus far can serve only hundreds of residents per city, advocates say their immediacy, simplicity and emphasis on radical trust are an antidote to the biases and bureaucracies that hinder other welfare programs.

“Cash is the currency of urgency,” said Mayor Shawyn Patterson-Howard of Mount Vernon, New York, at a conference convened by the National League of Cities in November. “People need money right now.”

Recent stimulus payments from the federal government have helped some Americans see the benefit of direct disbursements and may have chipped away at public resistance: A poll commissioned by the Economic Security Project found that 76% of respondents supported “regular payments that continue until the economic crisis is over,” and a Gallup poll found widespread support for additional stimulus.

Proponents hope these local efforts will normalize and popularize guaranteed income in the U.S. for potential future federal action.

As we enter a second year of a pandemic that’s left more than 10 million Americans unemployed and 26 million hungry, most of these programs are geared at low-income residents. But they also expand ideas about what a guaranteed income might look like, with some tailored to more specific groups such as families with children or Black mothers, and more specific goals such as maternal health and racial justice.

Tackling Poverty

In December, Compton in Los Angeles County launched what could become the largest guaranteed income pilot in the U.S.

The majority-Latino city with a poverty rate double the national average is run by Mayor Aja Brown, who was elected in 2012 as the youngest mayor in the city’s history — a distinction she shares with former Stockton Mayor Tubbs.

Called the Compton Pledge, Brown’s guaranteed income project has already started disbursing payments to 30 low-income families. Rolling enrollment will continue through March until nearly 800 families are participating.

Households will get up to $1,000 a month for two years, with payments calculated based on the family’s size. Recipients are randomly selected from a pool of the city’s low-income residents, and the project emphasizes that formerly incarcerated and undocumented people are eligible, even as they slip through the cracks of traditional welfare programs.

The coalition of partners supporting the project is made up of “strong women of color who are not seeing this particular policy as an emergency measure in the wake of Covid-19, but also as the beginning of how we can reimagine community investment, where government invests its money, and who we consider essential,” said Nika Soon-Shiong, the co-director of the Compton Pledge and the executive director of the Fund for Guaranteed Income.

Along with studying how people access the money and then how they spend it, the program has designed a basic income web portal for communications and payments, which other cities could use for future projects.

Compton’s program, like Stockton’s, is geared broadly at residents with lower incomes. Another program in Hudson, New York, will follow a similar model, with $500 monthly payments to 25 low-income residents for an even longer duration: five years.

But many of the other new programs are geared at even more specific populations.

Pursing Racial Justice

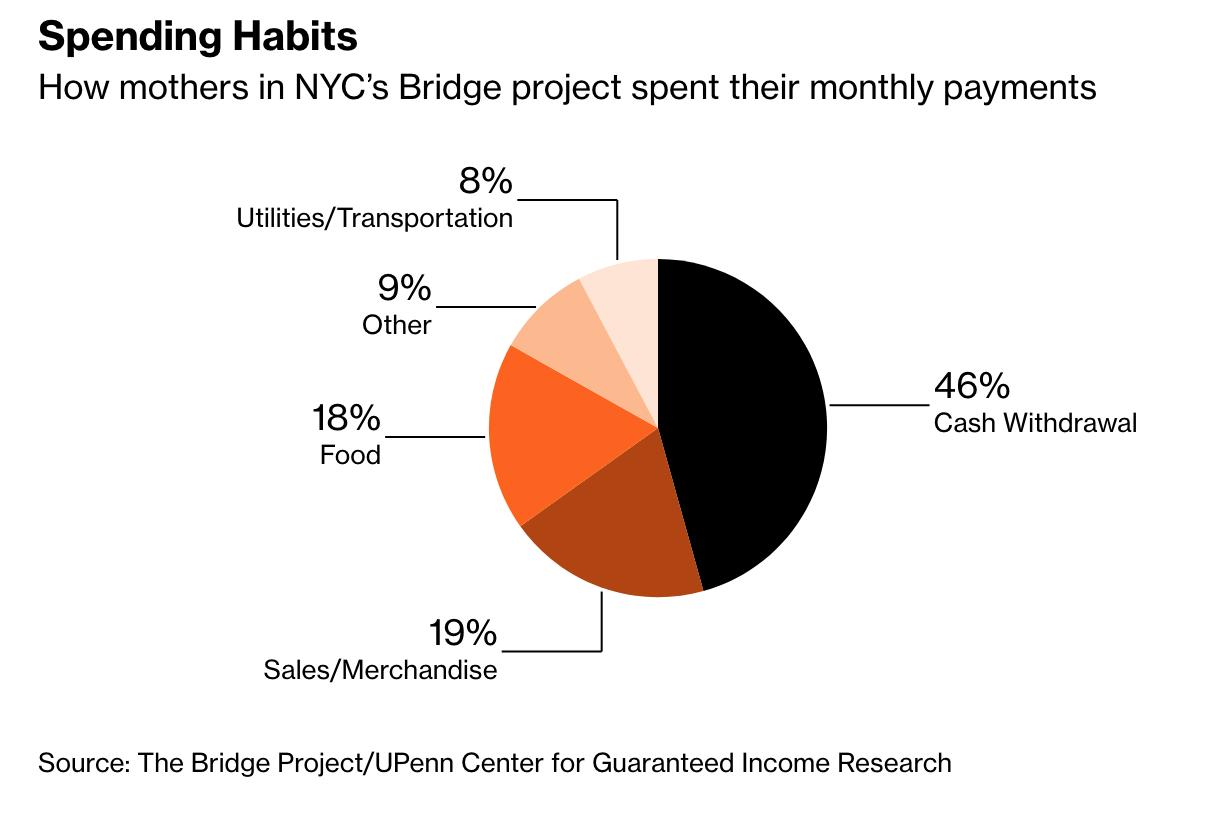

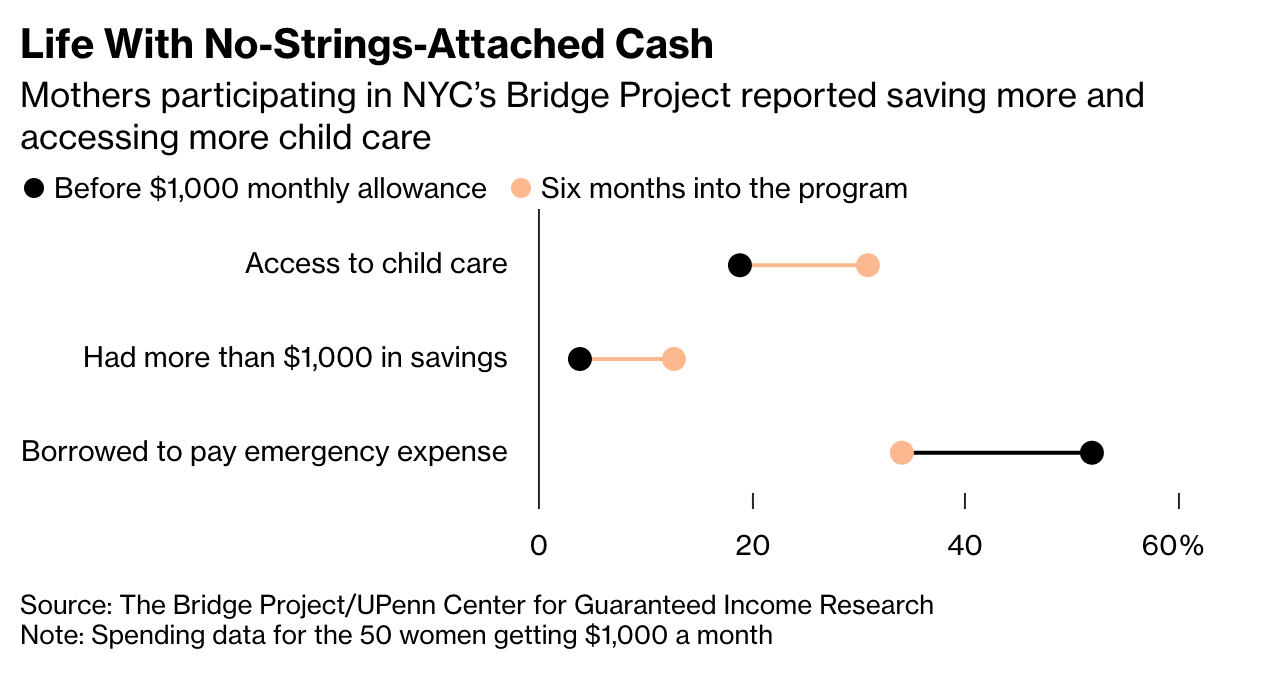

“If we offer our families a little bit of breathing room, will they be able to dream about something a little bigger?” That’s the question posed by the Magnolia Mothers Trust, a program launched in Jackson, Mississippi, to provide Black low-income mothers with $1,000 a month.

After a year-long pilot starting in December 2018 with 20 women, some takeaways emerged: Three-quarters of the participants were able to give their families three meals a day, and collectively, they paid off $10,000 in debt.

The women said they worried less, and were more hopeful about their futures. In 2020, the program started its second round, expanding to include at least 110 different mothers in Jackson.

Jackson is one of a number of cities narrowing its guaranteed income program to focus on racial justice, using the funds to address structural inequities. San Francisco’s mayor, London Breed, partnered with local birth equity initiative Expecting Justice to launch a targeted basic income program geared at the earliest phases of motherhood:

“The Abundant Birth Project” will support 150 Black and Pacific Islanders with $1,000 a month throughout their pregnancies and six months after, in an effort to reduce the disproportionate toll of maternal and infant mortality among those communities of color.

Unlike other programs for pregnant women that focus on providing particular services like transportation or medical care, this one empowers women to spend it on whatever comes up each month. Eventually, the hope is to supplement San Francisco mothers’ income for two years postpartum.

“Structural racism, which has left Black and Pacific Islander communities particularly exposed to Covid-19, also threatens the lives of Black and PI mothers and babies,” said Zea Malawa, who works on maternal and adolescent health at San Francisco’s Department of Public Health, in a statement.

“Providing direct, unconditional cash aid is a restorative step that not only demonstrates trust in women to make the right choices for themselves and their families, but could also decrease the underlying stress of financial insecurity that may be contributing to the high rates of premature birth in these communities.”

In Columbia, South Carolina, a pilot will focus instead on Black fathers to “address the fracturing of families.” The program, called the Columbia Life Improvement Monetary Boost, or CLIMB, will provide $500 a month for two years to 100 men chosen at random in partnership with the Midlands Fatherhood Coalition, an organization that works with South Carolina dads.

“Cash is the currency of urgency. People need money right now.”

Pittsburgh’s program has a more complex design, tailored to research on its own city: In 2019, a race and gender equity study revealed that Pittsburgh has some of the highest rates of poverty, unemployment and adverse health outcomes for Black women among U.S. cities.

Based on those findings, and the threat of the Covid-19 pandemic, the mayor’s Gender Equity Commission made several recommendations, among them building out a universal basic income pilot program.

Mayor Bill Peduto took heed, first announcing that he was joining the Mayors for Guaranteed Income group, and then unveiling a pilot program, the Assured Cash Experiment of Pittsburgh, slated to begin in 2021.

Some 200 families that earn less than 50% of the city’s area median income will receive a monthly $500 stipend over two years.

Half of the spots will be reserved for Black women-led households. So far the program is propped up by philanthropic and corporate dollars, but Peduto’s office is reviewing the law to see if the city can match funds for it as well, in hopes of scaling it up.

“From the beginning we thought that the city should have skin in the game, as a show of good faith to show that we’re a part of this program and believe in it. It needs to be piloted to be able to show people what the benefits can be, and then we have to be able to utilize the data in order to create benchmarks,” said Peduto.

“There are a multitude of indicators that we can look at but you’re never going to be able to prove it or see it if you can’t test it.”

Addressing Family Needs

Several other programs are focusing on families with kids. Mayor Melvin Carter launched the “People’s Prosperity Pilot” in St. Paul, Minnesota, to reach 150 families chosen randomly from those who signed up for another city initiative, which gives every newborn a college savings account seeded with $50. These families will get $500 a month for 18 months.

Carter says he’s seen the limitations of existing aid for families firsthand: As a child, his daughter had allergies to milk and peanuts, but because of the strict rules around how Women, Infants and Children benefits can be spent, his family wasn’t able to use the funds to purchase unique essentials like soy milk or almond butter. Already, more than 100 participants have signed up, Carter said.

Richmond, Virginia’s “Richmond Resilience Initiative,” launched by Mayor Levar Stoney this year, had an initial goal of reaching 18 low-income working families with kids who don’t qualify for other forms of government benefits; after Dorsey’s donation, the program has been expanded to reach 55.

Oakland hasn’t yet released details about its planned cash transfer program, but Mayor Libby Schaaf has said it, too, will target families with children upon its launch next year. And as Providence, Rhode Island, Mayor Jorge Elorza plans his city’s pilot, he says he’s been reflecting on the way money struggles “tear families apart.”

Paying For It

Particularly at a time of dire financial challenges for cities, most programs are benefiting from at least some private funding: Stockton’s pilot was entirely philanthropy-funded, though that didn’t insulate it from critiques by skeptical constituents, Tubbs said.

The Compton Pledge is a partnership between the city, the Fund for Guaranteed Income and the Jain Family Institute, and is funded entirely from private donations.

Other mayors have bolstered philanthropic investment with public dollars. Richmond partnered with the local Robins Foundation. Patterson-Howard says that since Mount Vernon’s project would double as a housing stability program, she’s looking to use federal Department of Housing and Urban Development funds and money from the CARES Act Covid relief legislation passed by Congress.

While the pilot is still in design mode, she hopes to target 75 to 100 families, and has already begun talks with the county, faith-based organizations, Black and brown sororities and fraternities and local businesses. For corporations that pledged to support the Black community in 2020, Patterson-Howard says this is a “sexy” opportunity to put those words into action.

Carter started St. Paul’s program with CARES Act dollars, combined with private fundraising. “One individual called me and asked how he could give $90,000 anonymously and when the check came, it was for twice that amount,” said Carter. Business leaders see the value in this kind of project, he said: “They need a stable workforce, who can feed their children and participate in their economy, as well.”

Not everyone is so gung ho. Critics of basic income come from the right and the left, the wealthy and the poor. Some argue that the money will be spent on drugs — in Stockton, on average, most of the $500 researchers tracked was spent on food and essentials each month — or that it will deter people from looking for work, an outcome deflated by a Finland experiment but hard to definitively disprove.

Others are turned off by the original idea of universal basic income that rich people could be included, or frustrated that they were not one of the randomly selected recipients in more targeted experiments.

The narrower scope of the new wave of pilots also has its own drawbacks: By tailoring eligibility to families with children or other specific groups of people, the pilots replicate some of the constraints of the national welfare system.

Means-tested benefits already miss out on a lot of people, either intentionally or accidentally. On the flip side, some people who do get federal benefits like disability or housing may fear that signing up for guaranteed income would make them ineligible.

Dispelling these doubts and building a case for why cash works has been a persistent focus for the mayors who are leading these projects. To many city leaders, the most enduring effect of these experiments may be to erase notions of “deservedness” from the welfare conversation entirely.

“We don’t tell banks how to use their money when we bail them out, we don’t tell companies how to use their money when we bail them out,” said Patterson-Howard. Essential workers deserve to spend their money on their own terms, too, she said.

“This space is full of racist tropes about what ‘those people’ will do if you give them money,” added Carter. “None of them are based in fact, statistics or real data. We have the opportunity to disprove some of those.”

Updated: 1-17-2021

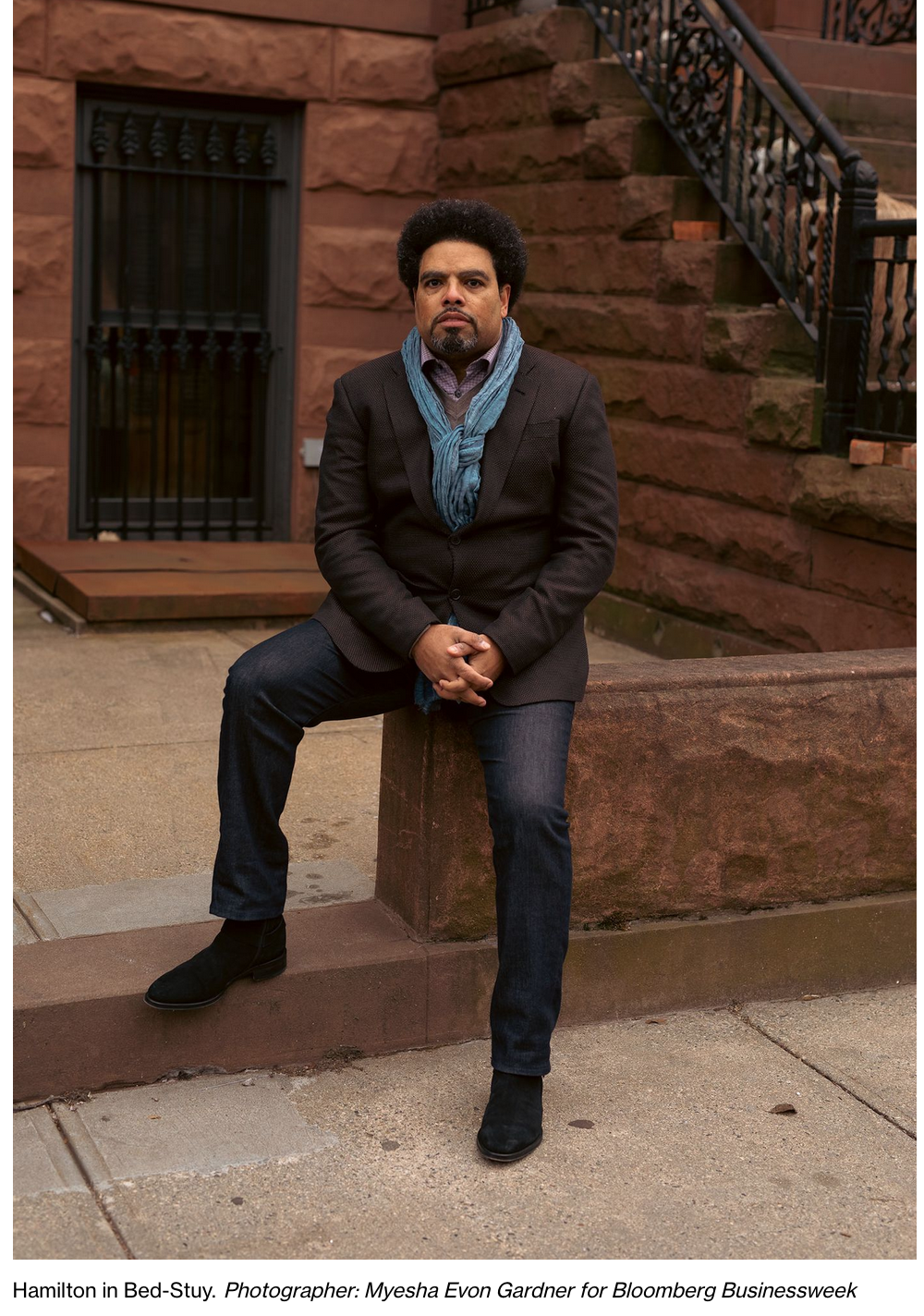

Can A ‘Guaranteed Income’ For Black Entrepreneurs Narrow The Wealth Gap?

To tackle barriers to capital for Black businesses, an Oakland project is trying a new strategy: Monthly cash payments, no strings attached.

As dozens of cities roll out or contemplate “guaranteed income” pilot projects to give residents money with no strings attached, a program in Oakland, California, is testing a similar model to help small businesses.

Runway, which calls itself a “financial innovation firm,” originally helped Black women entrepreneurs mainly through small loans. But in 2020, Runway began gifting its business-owner clients — which it calls its “family” — with a monthly $1,000 stipend, no strings attached.

The Rapid Emergency Fund project is a pilot, which Runway is billing as a “universal basic income” experiment for Black business owners, to see if this kind of supplemental income could be curative for the racial wealth gap. It started in March when all non-essential businesses were ordered to close to stop the spread of Covid-19.

The experiment is the brainchild of Jessica Norwood who before co-founding Runway, studied the problem of why Black businesses fail as a research fellow for several organizations including the Nathan Cummings Foundation and the Center for Economic Democracy.

She arrived at the often-cited reason that financial institutions don’t finance and capitalize Black entrepreneurs like they do white ones. But digging deeper, she found that many African Americans also don’t have a family-and-friends network to rely on for backup even if they do get financing.

A 2016 Bank of America study found that more than a third of business owners received a financial gift from friends and family to help launch their companies. Because of the racial wealth gap — the median net worth of white families is an estimated $171,000 compared to the $17,150 median net worth of Black families — there’s just not a lot of disposable money laying around among Black parents, aunties and loved ones for them to help out kindred Black entrepreneurs when they need it. So Runway became the family Black entrepreneurs needed.

The firm launched in 2018, by providing low-interest loans of between $2,500 to $20,000 to a small group of Black entrepreneurs in Oakland, as part of its Runway Friends & Family Loan Program. To qualify, the awardees didn’t need an unblemished credit score or tall history of triumphant businesses.

They only needed to be “capital ready” — meaning having a strong business plan and having completed a local business training program. The current crop of loanees were nominated through Runway’s technical support partner, the Uptima Entrepreneur Cooperative. Once awarded the loan, its clients were only responsible for making interest payments of 4% for the first two years.

In the spring of 2020, Runway’s rapid emergency fund began giving these loan recipients direct cash infusions of $2,000 upfront, and then a $1,000 monthly stipend through October to keep them afloat, also providing them with free business and marketing consultancy services.

After the first year of the experiment, some results are already clear: Not one of the 30 businesses in the Runway consortium had to close up shop due the pandemic shutdowns. Considering the dry run a success, Runway began a second round of guaranteed income funding to its clients in November.

Candace Cox, who runs the Oakland-based artisanal jewelry and home decor store called Candid Art, thought it might be time to hang it up when cities and states first started ordering businesses to close last year. She had run out of fabric so she couldn’t even make face masks. The emergency stipend allowed her to purchase the bulk fabric she needed to change her fate.

“I was already in my head like, ‘I have to find a job or do DoorDash,’ but with the [Runway funding] I was able to pivot quickly,” said Cox.

The funding has been especially helpful given that many Black businesses were reportedly left out of the federal pandemic relief funding from earlier this year. There is incomplete data on the demographics of loan recipients from the Paycheck Protection Program, because the Small Business Administration did not require race data on its loan applications, according to the Center for Public Integrity.

However, of the 10% of loans where race was reported, 78% went to white business owners compared with 3% for Black owners, according to the report. Far more PPP loans went to businesses in majority-white congressional districts in the first round of funding compared with loans made to businesses in majority-nonwhite districts — though there was more parity by the second round of funding.

Runway sees its loan and guaranteed income work as part of a mission to build “emergent financial practices and infrastructure that close the racial wealth gap for good.”

While Norwood describes the cash payments as a sort of “universal basic income,” it differs from other such projects because the money is coming from a private organization and donors, not the government.

To fund their own project, Norwood and her fellow co-founders — all women of color — approached investors and donors who’ve been inquiring in the past few years about what they could do to help with anti-racist work and addressing the racial wealth gap problem. Several banks and financial institutions, including Berkshire Bank and the Self Help Federal Credit Union in Oakland, have also signed on as investors in Runway.

“This is a unique model where we try to put the entrepreneurs first and they all in fact see themselves as a cohort, helping to grow each others’ businesses,” said Norwood. “They know underneath all of this is a common set of values and that is what keeps them working as a community.”

Runway is currently developing a new cohort of Black businesses to finance in Boston. Norwood said she’s also fielding demand from many other cities, but cautioned that they weren’t looking to do a rapid expansion, mindful of the “violence of rapid capitalism” that she says has actually destroyed many Black communities.

“The history of capitalism has been predatory and violent for Black people, so we want to make sure that doesn’t happen with us,” said Norwood. “Capital needs to move, but it has to be the right kind of capital with the right kind of money. It can’t be episodic and it has to be deeply, deeply generous.”

Updated: 2-17-2021

Universal Basic Income Could Be Coming For Kids

Tax-credit proposals would send almost every parent $250 or more a month.

Entrepreneurs, intellectuals and presidential candidates have in recent years touted “universal basic income,” a cash stipend to everyone with no strings attached, as the answer to poverty, automation and the drudgery of work. It has never gotten off the ground in the U.S.

Instead, something similar in spirit but cheaper and more practical may be in sight. Both President Biden and Sen. Mitt Romney (R., Utah) have proposed significantly expanding the child tax credit and dropping many of its restrictions, in effect turning it into a near-universal basic income for children.

The main aim of their proposals is to reduce child poverty, which is higher in the U.S. than in most advanced countries. Both would slash the number of children in poverty by around 3 million, or a third, according to the Niskanen Center, a center-right think tank.

In the process, it may also become the only major benefit in the U.S. that achieves near universality—testing traditional American notions of the safety net. “It would be a huge change in how we think about delivering benefits,” said Elaine Maag, principal research associate at the Urban Institute.

Federal benefits usually require the recipient to meet some criterion of need: poor (for food stamps, welfare and Medicaid), unemployed (for unemployment insurance), working or looking for work (the earned-income tax credit and some programs with work requirements), or disabled (Social Security Disability Insurance). Only Social Security and Medicare approach universality: Almost all elderly are eligible.

While some 90% of households with children qualify for the current child tax credit, many don’t get the full $2,000 because they don’t owe enough tax. At most, they can receive back $1,400 more (the refundable portion) than they owe.

Mr. Biden’s plan, as detailed in legislative language unveiled by House Democrats last week, would boost the credit to $3,600 for a child under 6 and $3,000 for a child aged 6 to 17 and make it fully refundable, meaning even a parent with no income would receive the full amount.

The boost would start to phase out for individuals earning $75,000 a year and couples earning $150,000. The remainder would phase out starting at incomes of $200,000 a year for individuals and $400,000 for married couples, as it does under current law.

Mr. Romney would raise the credit for children under 6 even more, to $4,200. He would match Mr. Biden’s $3,000 for older children and start phasing out the full amount at $200,000 a year for individuals and $400,000 for couples. He would also replace the current earned-income tax credit, which is more generous for people with children, to a standard amount per family.

The upshot is that under Mr. Biden’s plan, families with two children would typically receive $6,000 to $7,200. Under Mr. Romney’s plan—$6,000 to $8,400. That’s less than the $12,000 per adult in universal basic income proposed by Andrew Yang, former Democratic candidate for president and now candidate for mayor of New York City.

But it’s a lot of money to a lot of parents, regardless of whether they work and (almost) regardless of how much they earn.

Almost as important is how the plans are administered: Both Mr. Biden’s and Mr. Romney’s proposals would pay the credit each month, instead of once a year when the recipient files his or her taxes. Mr. Romney goes further by entrusting the job to the Social Security Administration, which already sends monthly checks to Social Security beneficiaries. Mr. Biden would leave it to the Internal Revenue Service.

Ms. Maag said the IRS is better positioned to administer the plan right away; it already delivers some kind of benefit to 95% of families with children and has shown it can quickly send out checks as it did with last year’s pandemic-relief legislation.

But Melissa Kearney, an economist at the University of Maryland, thinks calling the benefit an allowance and administering it through Social Security would underline that this isn’t just another provision of the tax code. While academics consider a tax credit and an allowance “mathematically equivalent, in practice, they are not,” she said.

Just as Social Security represents a commitment to end elderly poverty, a child allowance would do the same for child poverty, she said. “We should set our priorities as a nation and then commit to spending on them.”

Universal basic income for kids costs a lot less than UBI for everyone. Ms. Kearney has estimated UBI for adults, depending on the design, would cost $1 trillion to $2.5 trillion a year.

By contrast, Mr. Romney’s plan would add $66 billion to current costs, which he would finance by ending several tax provisions and federal welfare block grants. Mr. Biden’s would cost $105 billion. He has yet to identify a permanent funding source.

UBI could discourage a lot of able-bodied adults from working, although experimental evidence is inconclusive. By contrast, the National Academy of Sciences estimates a $3,000 annual child allowance would reduce employment by only about 100,000 workers (compare that to the 1.4 million jobs a $15-an-hour federal minimum wage would cost, according to the Congressional Budget Office).

Moreover, those who work less are probably spending more time raising their children, a trade-off most Americans can relate to.

UBI for kids is also easier to sell politically. Many liberals like that most of UBI for kids goes to those on lower incomes without robbing other parts of the safety net. Some conservatives like that it’s pro-family. The two may be enough to make it happen.

Updated: 3-7-2021

Can A Guaranteed Income Help End Poverty?

A Q&A with former Stockton, California mayor Michael Tubbs on why giving Americans cash is an idea whose time has come.

Romesh Ratnesar: As the mayor of Stockton, California, you became a prominent advocate of guaranteed income — the idea that the best way to expand economic opportunity is to give people money, no strings attached, and allow them to spend it as they see fit.

Last week, a study of the guaranteed income program you launched, the Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration (SEED), found that among the 125 people who received the $500 monthly direct payments, the rate of full-time employment increased by 12 percentage points in one year. Receiving this stipend appeared to encourage work, rather than the opposite. Did that surprise you?

Michael D. Tubbs, founder, Mayors for a Guaranteed Income: Based on my own lived experience with poverty, I know that the issue is not that people don’t want to work, or that people are going to work less. So many people are trapped in dead-end jobs, which is compounded by poverty and economic scarcity.

People can’t afford to take a day off to interview for a better job, or pay for an outfit for the interview, or to fix their car so they have reliable transportation to get to the interview. So these findings weren’t a surprise at all.

And I hope they put to bed the notion that if we provide people with an economic floor, then they will forget to be industrious, forget to contribute or forget to be productive. In fact, the counter is true. We lose so much productivity and so much potential in this country because of economic scarcity.

RR: We now have the results of the first year of the SEED program, which preceded the pandemic. How has this crisis changed the conversation about guaranteed income and the need to rethink the social safety net?

MT: It’s highlighted the fact that a guaranteed income is not just part of pandemic response, it’s also part of pandemic preparedness. We live in a time of pandemics; it’s a question not of if but when. Covid-19 has been the most drastic example, but we’ve also had the energy crisis in Texas, we’ve had wildfires, hurricanes, all of which cause massive economic disruption.

The guaranteed income findings show that even before Covid, the $500 people received helped them build up a degree of economic resilience. When the pandemic happened, those that had guaranteed income were able to weather the shocks better than those who didn’t have it. And we see that reflected in the conversation right now in the halls of Congress, the need to provide cash relief to the American people.

We’ve had bipartisan support for sending out one-time money to the American people three times already. It’s sad that it takes a pandemic to get that level of empathy — particularly because so many folks were living in an economic pandemic before Covid-19.

RR: As you mentioned, there’s growing openness among leaders of both parties to provide more Americans some form of guaranteed income – whether through the stimulus checks or an expanded child tax credit, like the one proposed by Senator Mitt Romney, which would last beyond the duration of this crisis. What should Congress learn from the Stockton example?

MT: They should learn that you can trust the American people. You can trust that investing directly in the American people will yield dividends. You can trust that the American people are deserving of the dignity that comes with economic security. The best way to build back better is to give people the tools and resources to do so.

As for the specific proposals, I think the child tax credit is a step in the right direction, in terms of understanding the work of caregivers and the work of parenting — as someone with a 17-month-old, I can tell you, parenting is the hardest job I’ve ever had, and that includes being mayor.

But I think that people who don’t have children also deserve some form of recurring monthly checks. One reason we need a guaranteed income is because there are a lot of Americans who are choosing not to have children because of their economic situation, because they can’t pay for it, because they’re trapped in dead-end jobs, or because there’s so much student-loan debt.

RR: One of the criticisms of guaranteed income schemes is that we don’t have enough evidence that they work, because the sample size has been too small. The SEED program in Stockton only involved 125 people. Can we really generalize based on such a limited data set?

MT: This isn’t about the data; it’s really a question of political will. If data alone drove decision-making, we wouldn’t have the governor of Texas telling people not to wear masks. We’d have smarter policies on the climate; we’d have smarter gun policies.

All the data in the world is not enough to push political will on some issues. But the data is important. We designed a study with a sample size that is large enough to generalize — that was the point of the pilot. And to answer people who say this just happened in Stockton with 125 people, there are a bunch of pilots now happening all over the country.

Compton is doing guaranteed income for 800 residents. St. Paul is doing guaranteed income for 125 residents. Yolo County, California, is doing a basic income demonstration. So is Gary, Indiana. So there will be enough data. There’s also international data going back decades that speak to the same fundamental truths about the efficacy of a guaranteed income.

RR: How should the government pay for these programs?

MT: We gave $2 trillion dollars in tax cuts four years ago. If you reverse those tax cuts, that’s enough to pay for a guaranteed income for every household making $100,000 or less for a year. So that’s one way. We can legalize cannabis and use that tax revenue.

We can create a data tax or data dividend and allow everyone to own some of the wealth they generate through their online actions. We could defund the Space Force and other unseemly bloated military expenditures and use that to fund a guaranteed income. The issue is not whether we can afford to pay for it. The question is whether there’s a will to pay for it.

RR: You were elected mayor in 2016 at the age of 26, becoming the youngest big-city mayor in the country. You then launched this highly ambitious project to give people a guaranteed income, which hardly had a massive constituency behind it. Why did you decide to do that?

MT: For me, leadership is about the verb versus the noun, meaning leaders have to do something. And for me, having lived experiences with poverty and knowing so many people who are economically insecure, I felt a mandate to do something that was different. It would make no difference who was mayor if we weren’t solving the tough challenges and even being provocative about how we did so. It was also driven by my faith.

I’m a self-described church boy who grew up hearing that the righteous care about justice for the poor and that we’re judged, at least in my faith tradition, by how we treat the least of these. Being mayor was great, but I didn’t become mayor to be mayor. I became mayor to do things. I wanted to change lives, to change policies, change the conversation. I’m also a data person. I like to know what works, and I like to do it. And now we know, guaranteed income works. So let’s do it.

RR: You lost re-election last November. A lot of factors affected that outcome, but is there anything you would have done differently in terms of how you talked about the guaranteed income program and sold it to the citizens of Stockton? Could you have done more to convince people this was something they should support?

MT: I think the context in which we did this guaranteed income experiment bears mentioning. We were the first mayor-led guaranteed income demonstration in the history of this country. There was no template. It was new, and there wasn’t a pandemic to point to. Activation energy is always more difficult. Plus, disinformation is real. There’s a reason why we have an economy that works for the few and not the many.

There’s a reason why, 300 years after Thomas Paine and 60-plus years after Dr. King, who both called for a guaranteed income, that we’re just now having that conversation very seriously in this country. It’s not because Michael Tubbs can’t message. It’s because we’re going against a status quo that has a lot of interest in keeping things as they are.

And I was the first Black mayor of the city. It doesn’t mean that there weren’t other Black people in the 200 years of Stockton’s history that could have been mayor — it means there’s also some institutional bias and racism at work.

RR: Since leaving office, you’ve been focused on trying to build a national network, Mayors for a Guaranteed Income. What role can cities and mayors play in moving the needle on this issue?

MT: Mayors are the moral authorities and the real leaders in our democracy. They’re at ground zero for every major challenge. They have an understanding of what their constituents need. And mayors aren’t ideological. We’re very pragmatic. We’re very much about what works and how come we’re not doing it already. I formed Mayors for a Guaranteed Income because I knew that it would take some time to get the federal government to act.

But if we could get the mayors who represent the cities that these members of Congress and senators need to win their elections, then we would see more traction. And in seven months, we have 42 mayors who have signed on who are interested in the policy and want to test it. I can’t think of any other policy in this country right now where 42 cities have said, “We’re really going to try to do this.” And I think it’s incredibly exciting.

RR: What can these mayors say to the business community to build support for guaranteed income programs? What’s in it for employers?

MT: If you’re an employer, you do better when everyone does better — when consumers have more ability to spend, when people are healthier, when communities are safer. Guaranteed income is a massive investment in R&D, in the future prosperity of your company, your customers and your employees. The data says that you’ll have folks who are better able to contribute and be productive at work, so productivity increases.

And the pool of candidates to choose from increases. A guaranteed income allows people to have the agency to make decisions about how they spend their time, who they work for and to invest in training and upskilling if that’s what they need. And it also makes people healthier, less stressed, less anxious, better people and better employees, which is an overall win for all of us.

RR: What’s the bottom line? What is it going to take to make guaranteed income a reality for the Americans who can most benefit?

MT: Well, it’s going to take a majority of votes in the House of Representatives and a majority of votes from the Senate. It’s all political will. We know it works. The data in Stockton shows it works. The data from Mexico, Brazil, Kenya, Canada all shows that it works. The real question is, What else do our lawmakers need besides data to enact the policy? I think that’s where we’re at.

Updated: 4-19-2021

L.A. Set To Be Largest City To Offer Guaranteed Income For Poor

Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti is proposing a guaranteed income program for poor residents, making it the largest U.S. city to test such a policy.

Garcetti will ask the City Council on Tuesday to set aside $24 million in next year’s budget to send $1,000 monthly payments to 2,000 low-income families in America’s second-largest city, the mayor said in an interview. Funds from council districts and other sources could bring the total to $35 million.

Candidates for the one-year program would be selected from the city’s 15 districts, based on each area’s share of those living below federal poverty guidelines. Garcetti is targeting households with at least one minor, and suffering some hardship relating to the Covid-19 pandemic.

While the movement is nationwide, the magnitude of Los Angeles’s poverty, where one in five of Los Angeles’s nearly 4 million residents are barely able to make ends meet, puts a national spotlight on the program.

“How many decades are we going to keep fighting a war on poverty with the same old results,” Garcetti said. “This is one of the cheapest insertions of resources to permanently change people’s lives.”

The idea of the government providing poor residents with some basic level of income has been floated by a number of prominent people over the years, including civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., libertarian economist Milton Friedman and Republican President Richard Nixon.

Businessman Andrew Yang made the idea a centerpiece of his unsuccessful bid last year to be the Democratic presidential nominee, and he’s continuing to advocate for the policy in his campaign for mayor of New York City.

Accelerating Plans

Los Angeles would join a handful of other cities experimenting with a guaranteed income program. They include Stockton, California, Saint Paul, Minnesota, and Chelsea, Massachusetts. In many cases, the programs are funded by philanthropic organizations.

The coronavirus has accelerated plans for the program. In the past year, the Mayor’s Fund for Los Angeles, a non-profit affiliated with Garcetti’s office, has given out $36.8 million to 104,200 residents through a prepaid debit card called the Angeleno Card.

The city will be the recipient of more than $1.3 billion in federal stimulus funds from the recently passed American Rescue Plan, which could be used to fund the payouts. Los Angeles had a budget of roughly $10.5 billion in the current fiscal year.

“There’s no question the pandemic is proof that this works,” Garcetti said. “Small investments have big payoffs.”

California’s Lead

Garcetti, a Democrat in his second term, is co-chair of Mayors for a Guaranteed Income, which has been advocating for the policy at the federal level and funding local programs. The group, which has 43 elected officials as members, was founded last year by then-Stockton-mayor Michael Tubbs.

It has received $18 million in seed money from Twitter Inc. co-founder Jack Dorsey as well as $200,000 from Bloomberg Philanthropies, the charitable arm of Michael Bloomberg, founder and majority owner of Bloomberg News’s parent company.

California cities have been taking a lead with these programs. Compton, just south of Los Angeles, fully rolled out its program last week, with 800 families getting between $300 and $600 a month. Oakland and San Francisco also recently outlined details of their projects.

In San Francisco, grants and some revenue from hotel taxes will fund monthly payments of $1,000 to about 130 artists for six months beginning next month. Organizers said the pilot is the first to solely target artists. Oakland will tap private donations this summer to fund its guaranteed income program, providing $500 monthly to about 600 poor families.

Still, a majority of Americans oppose the federal government providing a guaranteed basic income, according to a survey last year by the Pew Research Center. Support for the policy is much higher among Democrats, younger people, Blacks and Hispanics. Nearly 80% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents oppose the idea of the federal government providing a basic income of $1,000 a month proposed by Yang.

Less Anxious

Stockton, about 80 miles east of San Francisco, distributed $500 a month for two years to 125 families. Research from the first year found that recipients obtained full-time employment at more than twice the rate of non-recipients, according to a release from Mayors for a Guaranteed Income. They were also less anxious and depressed, compared with a control group.

Beneficiaries of the Los Angeles program, which Garcetti is calling Basic Income Guaranteed: L.A. Economic Assistance Pilot, or Big:Leap, will be asked to participate in studies to evaluate the impact of the payments on their lives. The mayor said he was targeting $3.5 million in additional funding to study the results.

Ultimately the costs of such programs will be too big for cities to finance alone, he said. But with data proving it works, Garcetti said states and the federal government could be inspired to fund them.

“Everybody said: ‘You give people money, they’re going to buy even bigger TVs,” Garcetti said. “Stockton showed that’s just not true. Low-income Americans know what to do with additional resources to build health and wealth, but too many of them are caught in the cycle of poverty.”

Updated: 4-30-2021

Los Angeles Takes An Oprah Approach To Guaranteed Incomes

The city’s program looks more like “You Get a Car” than a transformative attack on local poverty.

Los Angeles understands publicity and trendiness. Its leading industries depend on grabbing attention and conjuring desire. Its culture celebrates storytelling.

So it’s fitting that in his recent State of the City address, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti announced plans to give 2,000 local households $1,000 a month for a year. He boasted of his role as a founding member of Mayors for a Guaranteed Income and touted his program as “the largest Guaranteed Basic Income pilot of any city in America.” The $24 million plan will also be the first paid for with taxes — funds from the federal American Rescue Plan — rather than private donations.

The idea is alluring in its apparent simplicity: The solution to poverty is reliable cash. Let’s give everyone a regular check.

“Everyone deserves an income floor through a guaranteed income, which is a monthly, cash payment given directly to individuals” without strings or work requirements, declares Mayors for a Guaranteed Income. The advocacy group has established a center at the University of Pennsylvania School of Social Policy and Practice to conduct and track research on the idea.