Ultimate Resource For What’s Taking Place In The Commercial Real Estate Sector

Storied real-estate investor is focusing on more mainstream deals, a strategy reflecting the dearth of distressed properties. Ultimate Resource For What’s Taking Place In The Commercial Real Estate Sector

Related:

Emergency Rental Assistance Program

Affordable Housing Crisis Spreads Throughout World (#GotBitcoin)

Home Flippers Pulled Out of U.S. Housing Market As Prices Surged

Housing Insecurity Is Now A Concern In Addition To Food Insecurity

Smart Wall Street Money Builds Homes Only To Rent Them Out (#GotBitcoin)

New Ways To Profit From Renting Out Single-Family Homes (#GotBitcoin)

No Grave Dancing For Sam Zell Now. He’s Paying Up For Hot Properties

Investors Are Buying More of The U.S. Housing Market Than Ever Before (#GotBitcoin)

Cracks In The Housing Market Are Starting To Show

Biden Lays Out His Blueprint For Fair Housing

Housing Boom Brings A Shortage Of Land To Build New Homes

Wave of Hispanic Buyers Boosts U.S. Housing Market (#GotBitcoin?)

Phoenix Provides Us A Glimpse Into Future Of Housing (#GotBitcoin?)

OK, Computer: How Much Is My House Worth? (#GotBitcoin?)

And indeed there has been a lot of talk lately about “office-to-resi” conversions.

So what does it take? In this podcast, we speak with Joey Chilelli, managing director at the Vanbarton Group, a firm that’s been involved with these projects for a decade and long before the pandemic upended both real estate markets. We discuss the challenges involved in actually pulling off these complex projects.

No Grave Dancing For Sam Zell Now. He’s Paying Up For Hot Properties

Sam Zell, who made a fortune buying distressed commercial properties, isn’t finding many bargains these days.

Instead, the storied real-estate investor is doing something he usually avoids: following the pack and spending big on something safer.

His most notable real estate deal during the coronavirus pandemic period came last month, when one of his companies agreed to pay about $3.4 billion for Monmouth Real Estate Investment Corp. Far from a hobbled company in distress, Monmouth owns 120 industrial properties in 31 states. The sector is one of the most profitable because of high demand for fulfillment centers from e-commerce companies such as Amazon.com Inc.

Mr. Zell also wasn’t able to drive as hard a bargain as he had in many previous distressed deals. The all-stock deal reached in May is valued at more than $18 a share, a near-record for Monmouth stock. He could conceivably have to pay even more, since Blackwells Capital, which made an $18-a-share all-cash bid late last year, said it is weighing options including a higher offer.

Mr. Zell declined to comment. But the 79 year-old’s more conventional investment strategy is the latest sign that the pandemic hasn’t produced the distressed opportunities many investors expected.

Hotels, malls and other properties have suffered enormous declines in revenue. But few owners have been forced to sell at steep discounts thanks to government stimulus programs and the Federal Reserve’s easy money policy which kept a lid on foreclosure.

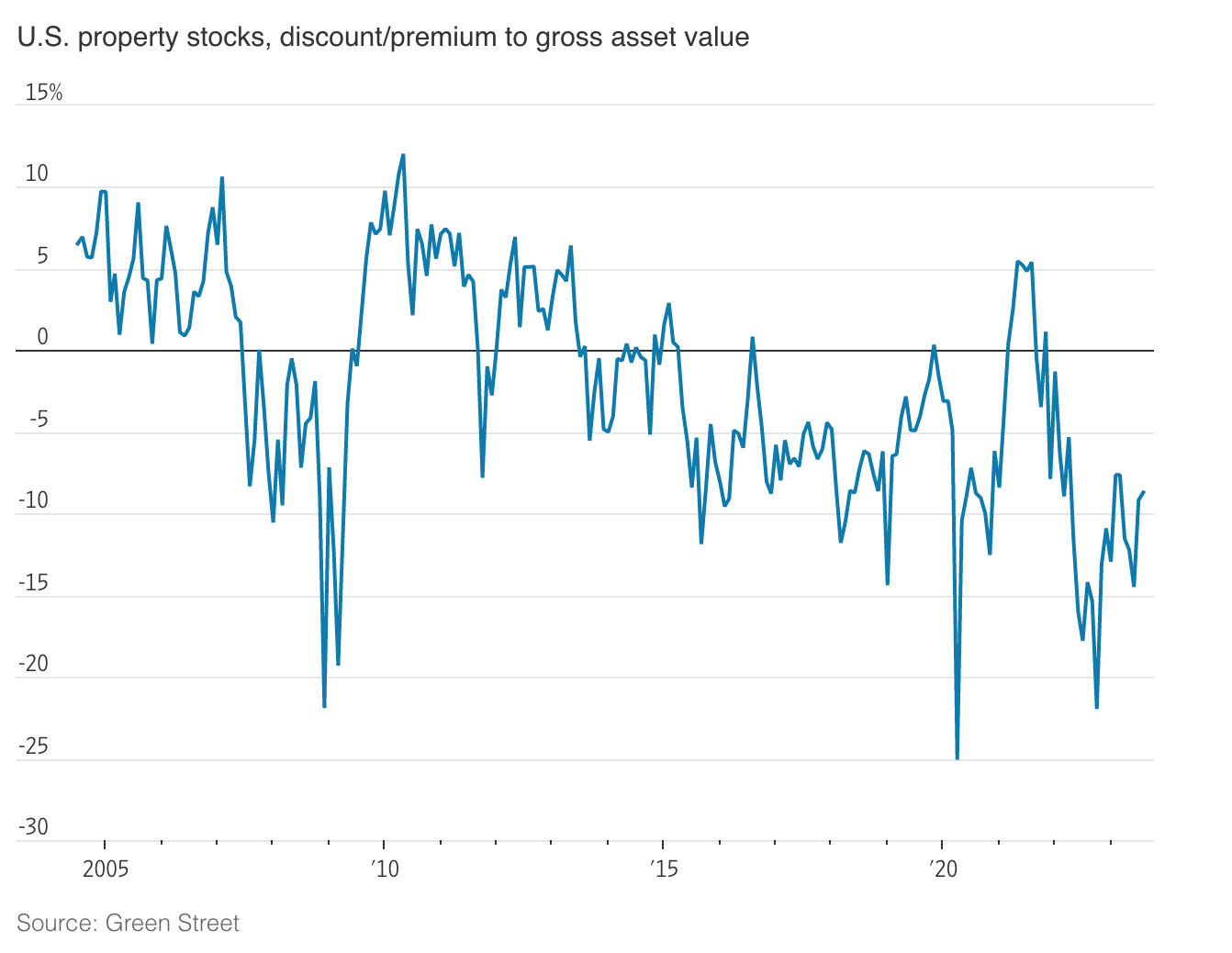

“From both a monetary and fiscal perspective, authorities have made sure that distress would be extremely limited in all walks of life,” said Cedrik Lachance, Green Street Advisors’ head of global REIT research.

Meanwhile, the popularity of online shopping and remote working during the pandemic raised big questions over when or if office buildings, malls and other property types would ever rebound. That has greatly increased the risk of buying such real estate at what might seem to be an attractive price.

Mr. Zell is known in the industry as the “grave dancer” for his ability to pick up wounded real estate for cheap prices, and then selling them years later at a big profit. He purchased dozens of foreclosed office buildings in the 1990s at steep discounts. He eventually sold most of them through his $39-billion Equity Office Properties deal in 2007.

Yet on a recent conference call, Mr. Zell described retail real estate as a “falling knife”—investors who think they are getting a bargain might end up getting bloody themselves. Prices haven’t fallen enough in the sectors that are getting beaten up, he said.

“There obviously is going to be an opportunity in retail. I just don’t think it’s here yet,” he said. He added that hotels also look expensive: “I can’t relate…pricing to the way I see opportunity.”

Mr. Zell owns a range of real estate through private and publicly traded companies as well as other businesses. His largest real estate holdings include his stakes in Equity Residential, which owns nearly 80,000 apartments, and Equity LifeStyle Properties Inc., one of the country’s largest investors in manufactured homes. Neither of these two companies made major acquisitions or dispositions during the pandemic.

His firm Equity Commonwealth, which has agreed to buy Monmouth, was formed after a group including Mr. Zell seized control of an office building company named CommonWealth REIT in 2014 by ousting its board in an unusual proxy battle.

The new board raised cash by selling most of its assets, recognizing that private investors were paying more for office buildings than their public market valuations.

The strategy was applauded by analysts. “Normally companies sell a couple of buildings and give themselves a pat on the back,” Mr. Lachance said. “These guys just kept going.”

Mr. Zell’s goal was always to reinvest that cash. “What it tells you about the Covid era is that they just couldn’t find true distress,” Mr. Lachance said.

The $10 Billion Bright Spot In The Battered World of Office Real Estate

Blackstone, KKR and other investors are betting on laboratory space as vaccines fuel the economic rebound.

Even as the remote-work era clouds the future for offices, one segment of the business is drawing cash from investors including Blackstone Group Inc. and KKR & Co.

More than $10 billion has gone toward buying buildings used for life sciences and other research this year, according to Real Capital Analytics Inc. That accounted for approximately 4% of all global commercial real estate transactions through May, double the share from last year.

That estimate doesn’t count new construction, and fresh buildings are breaking ground in U.S. cities including Boston, San Diego and San Francisco — many without having signed major tenants. Unlike workers in conventional offices, many scientists don’t work remotely. And as vaccines help fuel the economic rebound, funding for medical innovations is expected to drive the need for more space, particularly in the U.S. and U.K.

“The pandemic only amplified the demand growth, but it’s a trend we think will continue for years,” Nadeem Meghji, Blackstone’s head of real estate Americas, said in an interview. “This is about, broadly, advances in drug discovery, advances in biology and a greater need given an aging population.”

Last year, as social-distancing emptied out office buildings and damped investor interest in malls and hotels, life science building sales and refinancing totaled about $25 billion, up from roughly $9 billion in 2019, according to Eastdil Secured.

Blackstone, a veteran investor in the sector, booked a $6.5 billion profit from refinancing BioMed Realty Trust, the largest private owner of life-science office buildings in the U.S. It also agreed in December to buy a portfolio of lab buildings for $3.4 billion.

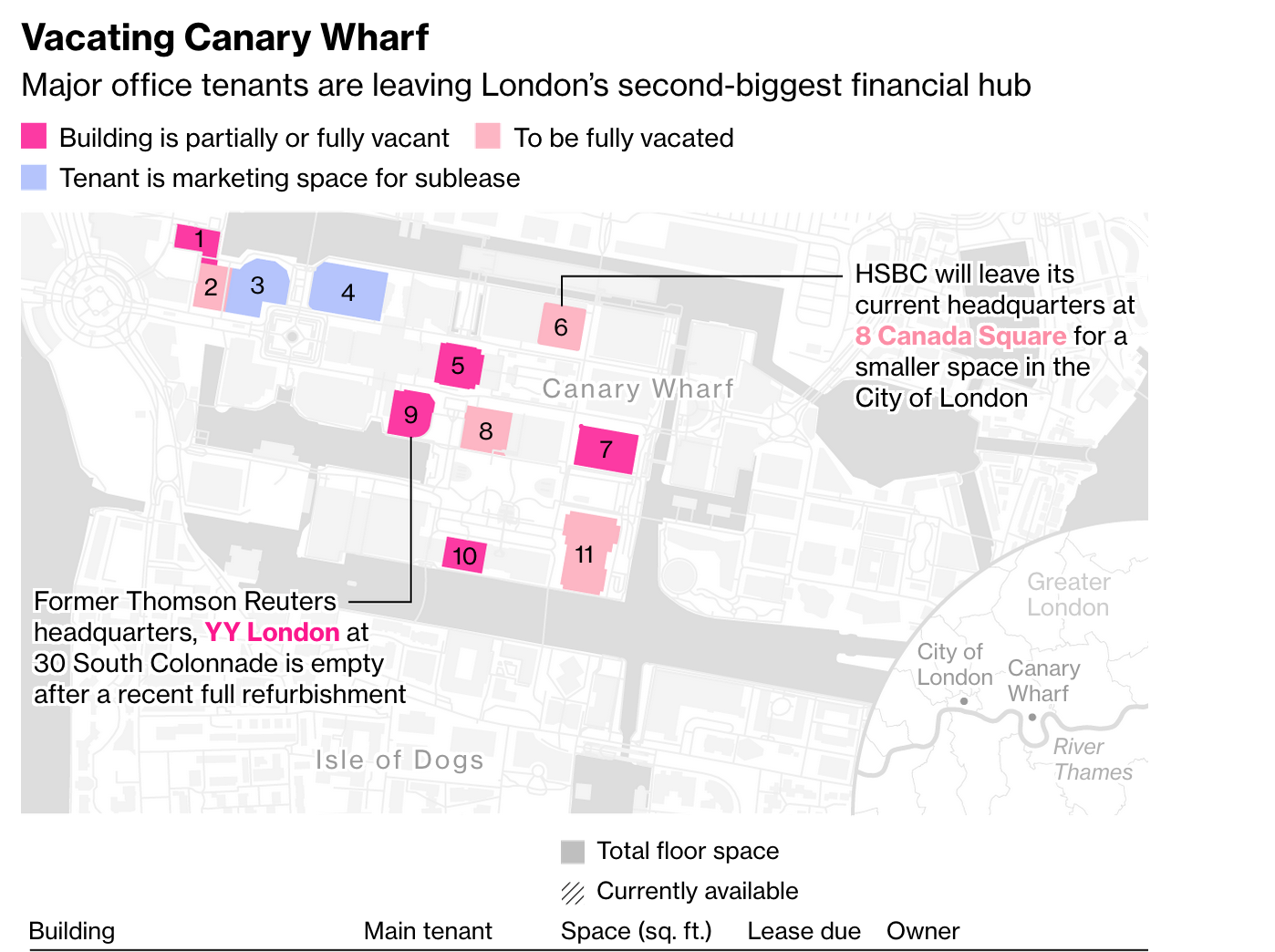

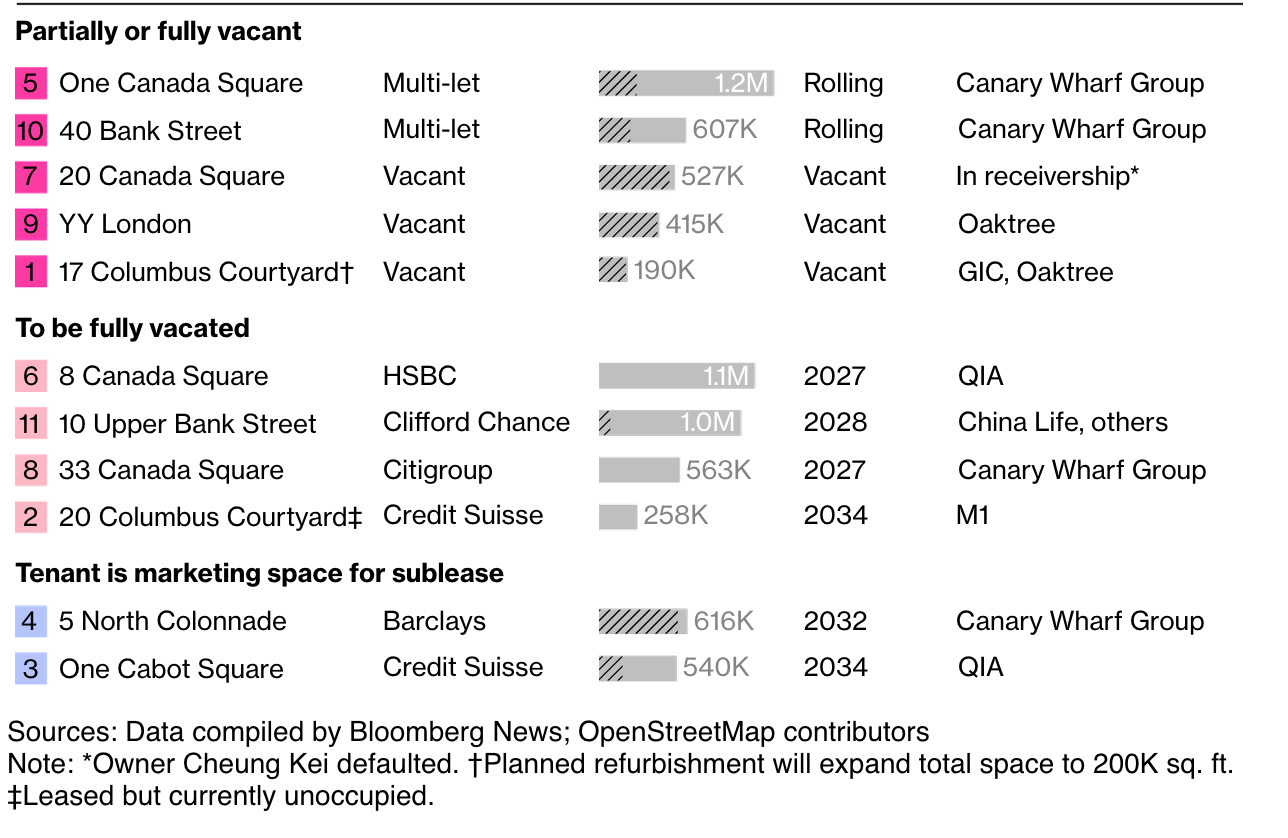

KKR paid about $1.1 billion in March for a San Francisco office complex it plans to repurpose for life science tenants. DropBox Inc. had rented the entire site in 2017, but gave up the space so employees could work remotely. In one high-profile U.K. example, a science campus is planned for a Canary Wharf site once slated as the London headquarters for Deutsche Bank AG.

Overall, the U.K. life sciences market saw a 166% increase in the volume of transactions in the last three years, according to real-estate services firm Jones Lang LaSalle Inc.

Even before the pandemic, life science property was on the upswing. Over the last five years, asking rents for such space soared 90% in the San Francisco Bay Area compared with 20% for conventional office space, according to commercial property brokerage Newmark. In Boston, which along with nearby Cambridge is an epicenter of the industry in the U.S., asking rents climbed three times as fast.

Labs Lead

Life sciences specialist Alexandria out-gained office REITs through Covid-19.

Investors see the higher rents translating into higher property values, which explains why construction projects are moving ahead without tenants lined up. Among the biggest spec builders is IQHQ, a startup that raised $2.6 billion last year to develop laboratory buildings that are breaking ground without signed leases.

In April, the firm launched construction of Fenway Center, a $1 billion complex on a platform above Boston’s Interstate 90 with a rooftop view of the famed Red Sox ballpark. The firm isn’t concerned about filling up the space, according President Tracy Murphy.

“We build spec, but we don’t build blind,” Murphy said in an interview from San Diego, where her firm is pouring concrete for a 1.6 million-square-foot waterfront lab complex. “I don’t see any end in sight for money coming in.”

Harrison Street, a Chicago-based alternative real asset investor, has about $2.6 billion invested in lab properties and wants to double that over the next 24 months, Chief Executive Officer Christopher Merrill said in an interview. Alexandria Real Estate Equities Inc., the largest life sciences real estate investment trust, also has big expansion plans.

In January, it paid $1.5 billion for a project in Boston’s Fenway neighborhood. The company has 4 million square feet of space under construction — about 1 million of which still hasn’t been leased.

As investors clamor to break ground, there’s a risk of an oversupply of space, said Jeffrey Langbaum, an analyst with Bloomberg Intelligence. Another hazard for developers is that lab space construction can cost as much as 15% more than conventional offices. Science buildings require stronger structures and higher ceilings to accommodate features such as enhanced air filtration. That limits potential other uses for the property if health-industry tenants don’t materialize.

Lab buildings are trading for capitalization rates, a measure of returns for investors, of less than 4%, which is lower than apartment buildings or industrial properties. There’s been cap rate “compression” over the last year amid a surge in investor capital flowing into the sector, according to Sarah Lagosh, managing director in the Boston office of Eastdil.

The recovery of traditional offices is expected to take time as companies call employees back over the next few months. Even then, many firms have said they’ll let people stay home at least part of the time. That’s raised concerns about the future of downtown skyscrapers, while Covid-19 has added to the momentum for life sciences properties.

“The pandemic has pushed life sciences into warp speed,” said Jonathan Varholak, who runs the life sciences team in the Boston office of the real estate firm CBRE. “You can’t do chemistry from home.”

Updated: 6-29-2021

How A SoftBank-Backed Construction Startup Burned Through $3 Billion

Katerra’s downfall shows how Silicon Valley’s strategy of growth at any cost can backfire in complicated industries like real estate.

Venture-backed startup Katerra Inc. aimed to revolutionize the construction business by mastering every element of the trade at once. Instead, its June bankruptcy filing made clear just how difficult it is for Silicon Valley to disrupt this complex industry.

The firm’s downfall wiped out nearly $3 billion of investor money, making it one of the best-funded U.S. startups ever to go bankrupt. Katerra thought it could save time and money by bringing every step of the construction process in-house—from manufacturing windows to factory-built walls to making its own lightbulbs.

It sold the idea to a deep-pocketed roster of financial backers, including SoftBank Group Corp. , Soros Fund Management LLC and the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board. At its peak, the company was valued at nearly $6 billion.

But Katerra never managed to do very well at all the aspects of construction it hoped to master, former employees say, leaving some of them exasperated at its recent demise.

“You guys had the golden goose, you had all that money from SoftBank and at the end of the day it was all pissed away,” said Chris Severson, a former construction-cost estimator at Katerra.

Katerra’s failure is the latest sign that the hypergrowth strategy employed by social media and software companies faces challenges in complicated, slower-moving industries like real estate.

Its bankruptcy also highlights the difficulty of modernizing construction, which accounts for around 4% of U.S. gross domestic product but still operates largely the way it did 100 years ago.

The company is in the process of crafting a restructuring through a chapter 11 bankruptcy process—one that involves selling some assets and keeping its international operations, a Katerra spokesman said.

The Menlo Park, Calif.-based company was co-founded in 2015 by a group of entrepreneurs including Chief Executive Michael Marks, the former CEO of electronics manufacturer Flextronics International Ltd.

Katerra’s strategy was to bring the electronics industry’s end-to-end manufacturing process to the construction business. The firm would buy materials and fixtures like sinks and faucets in bulk, skipping the middlemen and selling them directly to general contractors. When the company found general contractors were reluctant to use their products, Katerra took on that role, too.

Properties would be built with assembly-line-made parts in its own factories and shipped to sites managed by its in-house construction business. Katerra would then turn them into apartments, hotels or offices designed by its architects, all with the help of its in-house software.

This would streamline the process and enable an apartment building to be built in as few as 30 days, slicing off many months that the process would take through traditional construction.

Katerra managed to succeed with some of this top-to-bottom process, but few developers were interested in everything Katerra offered.

Still, as Katerra’s business model became more complex, it found a new backer in SoftBank. With the help of the Japanese conglomerate’s nearly $2 billion investment, Katerra bought general contractors across the U.S. and a building-parts manufacturer in India.

It was further aided by $440 million in debt from Greensill Capital, a SoftBank-backed lender that tumbled into insolvency in March. Eyeing international expansion, Katerra signed a contract to build thousands of homes in Saudi Arabia.

“Everyone’s so excited about the mission that everybody just says yes to everything,” recalled Erica Storck, one of the company’s first employees. ‘It gets out of control.”

In its race to boost revenue, Katerra agreed to build properties before it had figured out how to mass-produce building parts and get them to its projects cheaply and quickly enough to make the model work, say former employees, customers and investors. Architects designed buildings with parts from Katerra’s factories, only to learn that the parts wouldn’t be ready. Losses on projects piled up.

The company often signed contracts with prices based on rosy projections and then turned to its in-house team of estimators to figure out how much it would actually cost. Often there was a gap of millions of dollars, said Mr. Severson, the former Katerra estimator.

“We just beat our heads against the wall going: ‘No you can’t, it’s not possible,” Mr. Severson recalled. In one case, the company briefly considered leaving air-conditioning units out of a California student-housing development to make the numbers work, he said.

When architects and engineers raised concerns, Katerra executives would at times hold up an iPhone, telling the skeptical workers that if it could be done for phones, it could be done for apartments, a former employee said.

Rather than mass-produce a single type of building, Katerra built offices, hotels, single-family homes and apartment buildings of varying heights. That made it much harder to mass-produce prefabricated parts in factories and reduce costs because a wall panel designed for a three-story apartment building didn’t work for a 10-story building, former employees said.

The contractors it acquired also often balked at buying parts from Katerra, preferring their old subcontractors and suppliers, these people said.

By early 2020, the company was in danger of running out of money. Mr. Marks’s solution was to go even bigger. To realize his seamless vision, he believed Katerra needed to also be a developer that would own stakes in the real-estate projects it built and get a cut of their profits. That, he said, was where the real money was, former employees recalled.

The company’s board, though, ousted him early last year. His successor, the former oil-field-services executive Paal Kibsgaard, cut costs in part by shrinking the company’s research and design and manufacturing divisions. The cuts came too late, and Katerra filed for bankruptcy protection on June 6.

Former employees said they still believe in the idea of a vertically integrated, automated construction company. Multiple former executives said they believe cost overruns on early projects obscured more recent progress elsewhere in the business, and Katerra could have been profitable if it pivoted to more development and stayed focused on growth.

Still, many in the industry think a more focused approach is better.

“The problem’s not money,” said Gerry McCaughey, whose Entekra LLC makes factory-built wood frames for houses. “They were trying to go end-to-end on everything—and that’s what failed.”

Updated: 8-16-2021

Billionaire N.Y. ‘Bottom Feeder’ Buys Malls As Others Run Away

Igal Namdar has made a fortune buying shopping malls no one else wants.

He scoops up struggling centers at bargain-basement prices after their landlords lose faith, betting he can turn a profit before the last tenants turn out the lights. So far, that strategy has netted big gains — as well as lawsuits accusing Namdar of allowing his real estate to slide into disrepair.

In building an empire of 268 properties in 35 U.S. states — most prominently aging malls in small cities — Namdar has accumulated a personal net worth of about $2 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index.

The pandemic accelerated Americans’ years-long shift to e-commerce, forcing many already-ailing department stores and apparel shops to go dark. Landlords that own lower-end malls — with high proportions of tenants that have fallen behind on rents or shuttered stores — have been hit especially hard.

For Namdar, that smells like opportunity. He expects a flurry of deals in 2022 as more owners of troubled retail properties head for the exits.

“Any seller of retail — malls or open air — any size of portfolio, we’re there,” Namdar, 51, said in an interview from his headquarters in Great Neck, New York. “We can close immediately, as is, where it is, with no due diligence.”

The formula for Namdar Realty Group and partner firm Mason Asset Management is to recruit down-market retailers to fill vacancies while holding down costs by limiting debt and capital-improvement spending.

“They’ve been a bottom feeder, historically, buying on the cheap, for pennies on the dollar and making a go of it,” said Jim Costello, senior vice president at Real Capital Analytics Inc. “It’s not the high end of the market, but it’s solid retail if you can set it up right.”

Real Capital tracks 134 of the Namdar Realty Group’s properties and estimates that portfolio is worth about $2.7 billion.

Namdar declined to comment on the value of the properties his company owns, or his personal wealth, but said the figures Bloomberg is reporting are inaccurate.

Plunging Values

U.S. mall values have plunged 46% from their 2017 peak, including an 18% drop since the Covid-19 pandemic started, according to real estate information service Green Street. Declines have been fastest among B and C-rated malls like Namdar’s, where sales per square foot average a few hundred dollars.

Namdar’s bet is that he can pay a small enough price to outrun the decline. He said he sees value in the properties as malls, where other investors in the market are more interested in redeveloping them for other uses.

“It’s all about the cost basis,” said Cedrik Lachance, director of research at Green Street. “If you’re buying to harvest cash and not reinvest, it will work.”

Some of the biggest landlords, including Simon Property Group Inc. and Brookfield Asset Management Inc., have walked away from centers where values slumped below the property’s debt. Other companies — Washington Prime Group Inc., CBL & Associates Properties Inc. and Pennsylvania Real Estate Investment Trust — filed for bankruptcy, raising the potential for massive portfolios to come up for sale.

Namdar and Mason have averaged 20 acquisitions annually over the past decade, but could swallow 100 at a time if the right deal came along, Namdar said, declining to provide details on how much money they plan to spend.

Mason President Elliot Nassim, 40, whose cousin married Namdar, focuses on leasing and redevelopment while Namdar oversees property management.

Namdar and Nassim make no pretense of catering to luxury consumers. They say they charge affordable rents so stores such as Claire’s, Lids and Piercing Pagoda can fill vacancies.

One center, the Eastdale Mall in Montgomery, Alabama, is now 100% leased, up from 70% when it was purchased in January 2020 for $24 million.

“Is it where my wife would shop?” Nassim said about their properties. “It’s a different market.”

Buyer Lawsuit

Their first purchase, in 2012, was the DeSoto Square Mall in Bradenton, Florida, after Simon defaulted on the debt. They sold it in 2016 for $25.5 million to ML Estate Holdings LLC, which sued two years later, contending the property had lower revenue and higher costs than represented.

“Namdar’s approach to its real estate business generally is to purchase marginally performing properties, drain them of cash and operating funds, and then sell them,” the lawsuit in New York Supreme Court in Brooklyn alleged.

DeSoto Square closed permanently in April, according to local news reports. Meyer Silber, an attorney for ML Estate, declined to comment.

Namdar has also been sued by retailers, including International Decor Outlet, which in 2017 accused the landlord of contract breaches such as malfunctioning air conditioning, substandard repairs and inadequate security at the Regency Square Mall in Jacksonville, Florida.

“Landlord is an absentee landlord with a reputation as a ‘slumlord,’” the complaint in Duval County Circuit court alleged.

At the same property, Impact Church of Jacksonville accused managers of avoiding upkeep, making the “building look abandoned.” Impact paid $7.4 million in 2016 to buy a former Belk department store on the site, where it now runs a school as well as a church. The price was more than half the $13 million Namdar paid for the entire mall, which names 46 other tenants on its website.

Namdar declined to discuss individual cases but said such complaints are rare.

“There were factors that led to this, such as not having the rent to pay,” he said. “Properties that are marked for redevelopment are few and far between, so we maintain our assets.”

In addition to buying properties, the company has acquired potential tenants. Last year, Namdar and Mason paid $12 million to buy cinema chain Goodrich Quality Theaters Inc. out of bankruptcy. They also invested in the furniture chain formerly known as Jennifer Convertibles.

Among recent mall deals was the $10.3 million purchase in April of Marketplace at Brown Deer outside Milwaukee, valued at $45 million in 2005, according to loan documents and an announcement by the seller, Retail Value.

“We’d like to improve our quality but we’re not going to pay a crazy premium for an A-mall,” Namdar said. “Our goal is to stick to those B and B-plus assets. Those A’s get to be too crazy. The Ferraris of the world — that’s not the kind of car we’re looking for.”

Updated: 9-8-2021

Bill Gates Takes Control Of Four Seasons In Deal With Saudi Prince Alwaleed

Bill Gates will take control of the Four Seasons hotel chain after his investment firm agreed to acquire a stake from Saudi Prince Alwaleed bin Talal’s Kingdom Holding Co., in a bet that luxury travel will rebound from a pandemic-induced slump.

Gates’s Cascade Investment LLC will pay $2.2 billion in cash to boost its stake in Four Seasons Holdings to 71.25% from 47.5%, according to a statement Wednesday.

The lodging industry has been hobbled by a drastic slowdown in global travel as the world struggles to halt the spread of Covid-19. Vaccination campaigns helped fuel a lodging rebound led by leisure travelers, but luxury hotels are still lagging behind lower-quality properties, according to data from STR.

Gates, 65, and Alwaleed, 66, have known each other for decades. In 2017, the Microsoft Corp. co-founder described the prince as an “important partner” in their charitable work, and he was one of a few Western executives to voice support for Alwaleed after he was detained and accused of corruption by Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman.

Four Seasons shareholders took the company private in 2007, when it managed 74 hotels, with Gates and Alwaleed leading the deal. The new owners expanded the company’s footprint to more markets in a bid to capitalize on what was then a booming market for luxury travel.

The chain now manages 121 hotels and resorts, and 46 residential properties, and has more than 50 projects under development, according to the statement. Its landmark Kingdom Tower in Riyadh is among the two dozen hotels it owns across the Middle East and Africa. That property is popular among the consultants and bankers who commute from nearby Dubai and have helped transform Saudi Arabia’s economy.

It has also expanded efforts to attach its brand to luxury homes, as real estate developers realized that affluent buyers would pay more to live in a condominium or residential community associated with the hotel brand.

Kingdom Holding, which will retain 23.75% of the hotel chain, plans to use proceeds from the transaction for investments and to repay debt. Four Seasons Chairman Isadore Sharp, who founded the company in 1960, will keep his 5% stake. The deal is expected to be completed in January.

‘Confirmed Understanding’

Alwaleed has made a series of deals since he reached a “confirmed understanding” to secure his release from detention in 2018. Shortly after, he invested about $270 million in music streaming service Deezer. In February, he sold a stake in his Rotana Music label to Warner Music Group Corp.

Cascade, which is run by Gates’s money manager, Michael Larson, first invested in Four Seasons in 1997, when it was publicly traded. The investment firm also manages the endowment of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Gates and Melinda French Gates ended their 27-year marriage last month. He has a net worth of $152.2 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index, and she has received almost $6 billion of shares in public companies, filings show. More precise details of how the ex-couple’s fortune is being split remain confidential.

Alwaleed’s wealth has been almost cut in half since 2014 and now stands at $18.4 billion. In an earlier interview, he attributed the decline to a slump in Kingdom Holding’s shares and not because of any agreement or settlement he made during his detention. About half of the prince’s wealth is tied to shares in the holding company, in which he owns a 95% stake.

Alwaleed’s holdings include shares of Citigroup Inc., ride-hailing firm Lyft Inc. and Accor SA.

His investment company reported a loss last year of 1.47 billion riyals ($392 million). The value of his other holdings — including Saudi real estate, public and private equities, jewelry and a superyacht — helped mitigate some of the losses, according to figures previously provided by the firm.

Shares of Kingdom Holding rose 1.1% on Wednesday, giving it a market value of almost 40 billion riyals.

Updated: 9-14-2021

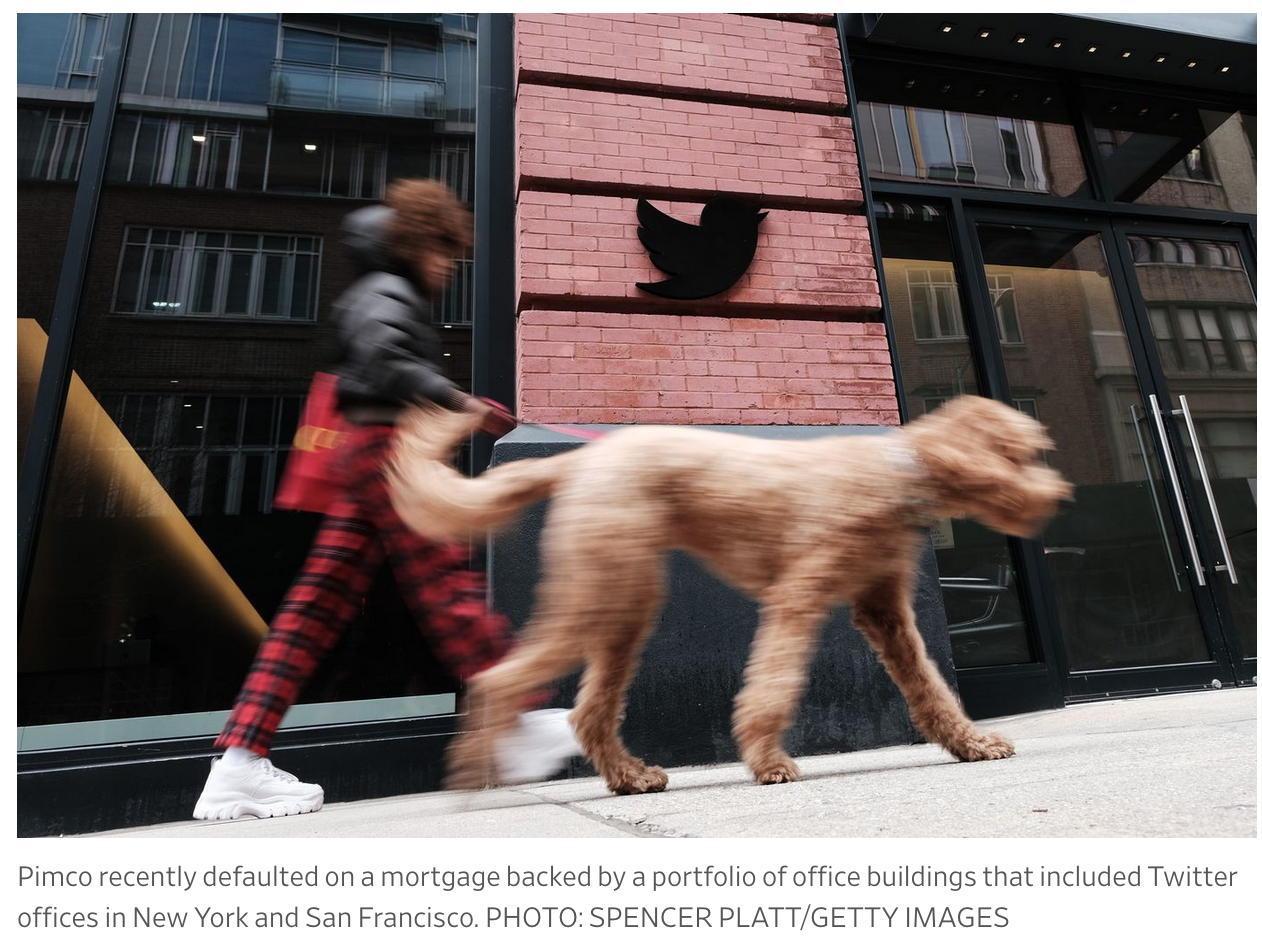

Pimco Sets Its Sights On Commercial Real Estate

As the Covid-19 pandemic reduces property values, the bond investor pursues higher yields by acquiring hotels and office buildings.

Pimco, one of the world’s largest fixed-income investors, has been ramping up its commercial real-estate holdings at the same time that historically low interest rates have undercut bond returns.

The firm, which is officially known as Pacific Investment Management Co. and has $2.2 trillion under management, has been seeking higher yields than those offered by investment-grade corporate bonds by buying hotels, office buildings and other property types that have lost value during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Pimco also has become more active because last year its parent, German insurer Allianz SE, put the firm based in Newport Beach, Calif., in charge of managing its Allianz Real Estate investment business. Between its own investments and those made by Allianz, Pimco acquired $12 billion in private commercial property between January 2020 and June 2021, the firm said.

The combined Pimco and Allianz real-estate business also originated or invested in $7 billion in real-estate loans during that time, a Pimco spokeswoman said.

In its biggest real-estate investment during the pandemic, Pimco agreed this month to pay $3.9 billion for Columbia Property Trust, a real-estate investment trust that owns a portfolio of office buildings in New York City, Washington, D.C., Boston and San Francisco. The purchase, subject to Columbia shareholder approval, would be the first acquisition of a pure office real-estate investment trust since 2019, according to Thomas Catherwood, an analyst with BTIG LLC.

Columbia owns 6.2 million square feet of space mostly in decades-old downtown office buildings, such as the former New York Times headquarters and 315 Park Avenue South in Manhattan.

The big bond manager’s recent property-buying spree stands in contrast to many dedicated real-estate investment funds and private-equity firms, which have mostly held on to money raised for distressed sales in hopes that prices might fall further.

In the early months of the pandemic, Pimco was the rare active competitor in the distressed public-securities market. The firm invested $1 billion in shares of real-estate investment trusts and commercial mortgage-backed securities. Pimco also was active last year restructuring properties as a lender, taking advantage of the retreat from the market of traditional lenders.

More recently, Pimco has been one of the first investors to begin buying downtown hotels. That sector has been slower to rebound than resort hotels because business travel has yet to make a big comeback.

Pimco’s recent hotel deals have included the W Washington D.C. hotel, which the firm agreed to buy for more than $200 million. The firm plans to rebrand the property, which opened in 1917 and offers views of the White House from its rooftop, as an independent hotel.

Pimco has been more optimistic than many other investors in the office sector. Some investors are steering clear of these buildings because the success of remote work has raised questions about whether office demand will ever return to previous levels.

But Pimco is bullish on well-located offices in major markets, as well as those “in high-growth markets like the Southeast that benefit from population migration,” the spokeswoman said.

By being a contrarian, Pimco is able to buy office buildings for lower prices. Pimco’s purchase of Columbia Property Trust amounted to $19.30 a share, or 20 cents below what an investment group led by Arkhouse Partners and the Sapir Organization offered in March. The price dropped as Covid-19’s Delta variant spread around the U.S.

“As recently as June, when vaccinations were going up and case counts were going down, there was a little more optimism,” said John Kim, analyst at BMO Capital Markets Corp. “But since Delta spread out, office REITs started to fall with the delay of return to office.”

Updated: 9-14-2021

Distressed Retail Debt Pile Collapses

Distressed debt tied to retail enterprises is putting on something of a vanishing act.

The overall amount of tradeable troubled debt has shrunk from near $1 trillion in March of last year to less than $60 billion as of September 10, data compiled by Bloomberg show. And the portion of that from the retail industry has collapsed at an even faster clip.

In late March 2020, about $60 billion of distressed bonds and loans could be traced to the retail industry, data compiled by Bloomberg show. That pile stands at some $1.1 billion now, representing about a 98% decline.

The retail industry has been in a tailspin for years, with brick-and-mortar sellers decimated by shifting consumer preferences and booming online rivals. The Covid-19 pandemic quickly made matters worse: lockdowns sent dozens of hobbled retailers into Chapter 11 bankruptcy, including the likes of J.C. Penney Co. and Brooks Brothers Group Inc.

Since then, a number of once-troubled retail giants have slashed their debt in bankruptcy, cut their store count or tapped wide-open credit markets to resolve immediate liquidity issues. Plus, massive government spending and a resurgent economy have helped troubled businesses more broadly.

“The pandemic accelerated restructuring plans for the weakest players, while the recovery narrative and, to no small extent, retail traders, facilitated a strong rebound for most survivors,” said Noel Hebert, director of credit research at Bloomberg Intelligence.

Elsewhere

So far this year, 95 companies with at least $50 million of liabilities have filed for bankruptcy in the U.S., according to data compiled by Bloomberg. That’s about half the pace seen last year, but still higher than the 10-year average of 93 filings as of September 13.

The total amount of traded distressed bonds and loans fell 6.9% week-over-week to $56.9 billion as of September 10, data compiled by Bloomberg show. The amount of traded distressed bonds dropped 3.9% week-on-week, while distressed loans slipped 14.6%.

There were 174 distressed bonds from 97 issuers trading as of Monday, down from 175 bonds and up from 94 issuers about one week earlier, according to Trace data.

Diamond Sports Group LLC had the most distressed debt of issuers that hadn’t filed for bankruptcy as of September 10, data compiled by Bloomberg show. Its parent company, Sinclair Broadcast Group Inc., said in a March filing that it expects Diamond to have enough cash for the next 12 months if the pandemic doesn’t get worse.

Updated: 9-24-2021

Home Builders Might Be A Home Run Once Supply Woes Ease

Lumber prices drop, but materials and labor hold back supply and send U.S. new home prices higher.

If only lumber had been all that was keeping home builders from selling more homes.

The Commerce Department on Friday reported that 740,000 new homes were sold in August, at a seasonally adjusted, annual rate. That was above July’s 729,000 but is nothing close to the 977,000 homes sold in August of last year.

The continuing problem is that builders have struggled to meet the increase in demand for homes that the pandemic helped set off. That struggle has been compounded by their difficulties obtaining materials and labor. Many builders have delayed putting homes on the market to bring their inventory levels back in balance with demand and taken other actions such as limiting how much buyers can customize homes.

One of the first indications of how severe builders’ supply-chain problems were came when framing-lumber prices began shooting higher last year. But many problems affecting lumber supplies have since been ironed out, and framing-lumber futures prices are now down over 60% from their May high. Yet there is a lot more that goes into building a house than lumber, and builders are dealing with myriad other materials that are in short supply, from garage doors to vinyl siding.

On Monday, Lennar said that in its fiscal quarter ended August 31 that it delivered fewer homes than it expected, blaming “unprecedented supply chain challenges.” Also on Monday, D.R. Horton said that it expects to close on fewer homes in its fiscal quarter ending this month than it earlier thought. It, too, cited supply-chain issues, as well as difficulties finding workers. KB Home on Wednesday reported fiscal third-quarter home deliveries that fell short of expectations and said that disruptions to its supply chain had intensified as the quarter progressed.

Even so, this is an especially profitable time to be a home builder. The Commerce Department reported the median price for a new home in August was $390,900, versus $325,500 a year earlier, and the drop in lumber prices is now providing them with a boost. D.R. Horton said that it expects the gross margin on its home sales in the current quarter to be 26.5% to 26.8%, for example, compared with its previous forecast of 26.0% to 26.3%.

It would be nice to have some assurances on when builders’ supply-chain woes will be worked out, but so far—and understandably given how uncertain the environment is—they aren’t giving them. If and when they are able to build enough houses to meet demand, they could be rolling in money.

Updated: 9-28-2021

Big Tech Companies Amass Property Holdings During Covid-19 Pandemic

Google, Amazon and Facebook acquire offices and retail space, helping prop up commercial real-estate markets.

The biggest U.S. companies are sitting on record piles of cash. They are getting paid next to nothing for holding it, and they are running out of ways to spend it.

So they are buying a lot of commercial real estate.

Google’s announcement last week that it would purchase a Manhattan office building for $2.1 billion is the latest in a string of blockbuster corporate real-estate deals since the start of the pandemic. Amazon.com Inc. last year paid $978 million for the former Lord & Taylor department store in Manhattan. Facebook Inc. bought an office campus in Bellevue, Wash., for $368 million.

Overall, publicly traded U.S. companies own land and buildings valued at $1.64 trillion, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence. That is up 38% from 10 years ago, and the highest for at least the past 10 years, according to S&P.

Retailers such as Walmart Inc. and restaurant chains such as McDonald’s Corp. have long been major property owners of their own stores. Big technology companies are now joining them, scooping up offices, data centers, warehouses and even retail space.

Buying real estate is a way for these companies to avoid sometimes pricey and cumbersome leases, because they often occupy these buildings and become their own landlords. These usually modern or renovated and sometimes custom-built properties are the kind of buildings that have appreciated in value over the years. But owning real estate also puts companies at risk of losses if urban property values fall.

For now, the corporate buying spree is helping prop up commercial real-estate markets at the same time many investors are shying away from office and retail buildings amid rising vacancy rates.

Many private-equity and real-estate funds have also raised hoards of cash, but for the most part they have been reluctant to spend during the pandemic in hopes that prices could fall further. And unlike real-estate investment firms, big corporations often buy their buildings without taking out mortgages, allowing them to spend more of their money and to close on deals more quickly.

A number of factors have converged to unleash the buying spree. For one, firms have more money to purchase real estate. Big, profitable companies that dominate their industries have grown even bigger, allowing them to accumulate more cash.

More recently, uncertainty over how much Covid-19 will harm the economy has prompted more companies to hoard cash, said Kristine Hankins, a professor of finance at the University of Kentucky.

U.S. publicly traded companies hold $2.7 trillion in cash, cash equivalents and short-term investments, not counting real-estate and financial companies, according to S&P Global. That is up more than 90% from the fourth quarter of 2011.

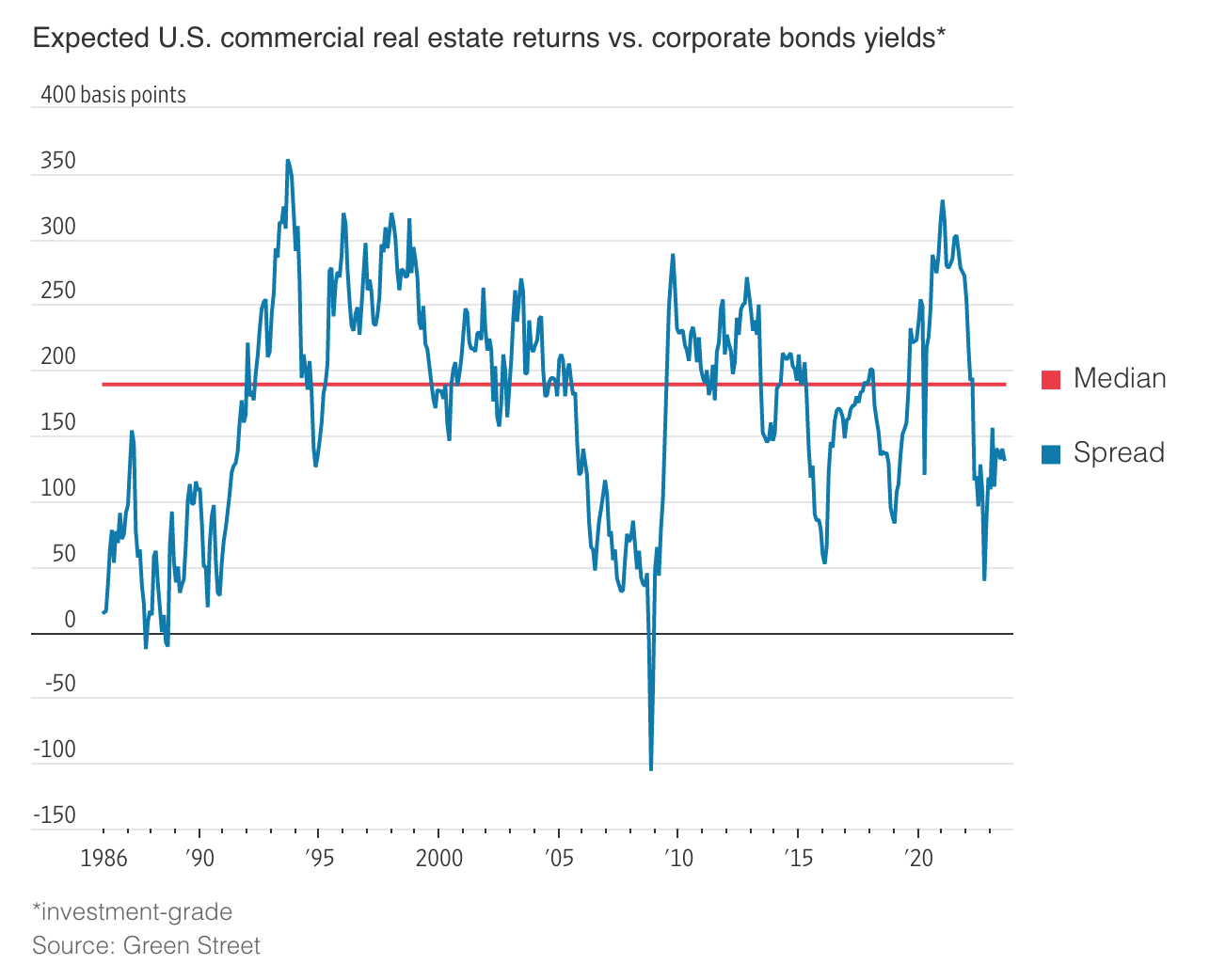

Interest rates are hovering around their all-time lows, so companies can get higher returns buying real estate than by keeping their money in low-risk bonds or other public securities, said Brian Kingston, chief executive of real estate at Brookfield Asset Management.

“That cash is just sitting there in a not particularly productive way,” he said.

Office prices, meanwhile, have fallen in Manhattan, San Francisco, Chicago and other big cities during the pandemic, making investing in this real estate cheaper than it was 18 months ago, investors say.

Google and its deep cash coffers have set it apart from most every other company in terms of an increasing appetite for real estate. Alphabet Inc., Google’s parent, held $135.9 billion in cash, cash equivalents and short-term investments as of the second quarter of 2021, more than any other publicly traded company, not counting financial and real-estate firms, according to S&P Global.

Alphabet is now one of the biggest real-estate owners in New York City and the U.S. It held $49.7 billion worth of land and buildings as of 2020, up from $5.2 billion in 2011.

Google buys real estate because it wants to control the buildings it occupies, for example to make changes without having to get a landlord’s permission, said the company’s director of public policy and government affairs, William Floyd.

Amazon, which owns a lot of warehouses, held $57.3 billion worth of land and buildings—more than any other U.S. public company except Walmart. The online retailer doesn’t care whether it buys or leases as long as the building is right, according to the company’s vice president of real estate and global facilities, John Schoettler.

“We’re really agnostic about it,” he told The Wall Street Journal last fall.

The Beauty of Buying A Ski Home In Idaho? Nobody Knows A Thing About It

Not typically regarded as a high-end ski destination, the state is attracting a wave of home buyers who want smaller resorts, shorter lift lines and a more low-key, laid-back vibe.

Schweitzer Mountain has 2,900 acres, great snow and stunning lake views; it’s Idaho’s largest ski terrain area.

Most people have never heard of it.

“We have no lift lines. It’s low-key, it isn’t pretentious and there’s a strong sense of community,” says David Thompson, a retired surgeon from Houston who bought a ski-in, ski-out house there with views of Lake Pend Oreille in 2009 for $850,000.

It isn’t easy to get to Schweitzer—the closest major airport is in Spokane, Wash., about a two-hour drive, including a steep road with sharp switchbacks. The two fastest routes from Idaho’s capital, Boise, are 10-12 hours and involve going through either Washington or Montana.

There aren’t many shops and hotels right at the mountain’s base, and cell and internet service can be spotty in the area. Residents have to pick up their mail in the village.

But Schweitzer is in the midst of a dramatic transformation, aiming to become a destination resort. Last season it added seven runs and two lifts and joined the Ikon Pass, a 47-mountain destination ticket that gives members access to elite ski areas around the world, including Aspen, Colo., Jackson Hole, Wyo., Utah’s Deer Valley, Vermont’s Killington and Zermatt in Switzerland.

The resort village, with a year-round population of about 65, currently looks like a giant construction site, as the resort embarks on a multiphase rollout of residential development. An angled, contemporary glass-and-steel hotel and restaurant, designed by hip Portland, Ore., firm Skylab Architecture, is rising amid the more traditional alpine condos and lodges.

The skeletons of new modern houses and townhouses bolstered by steel rods now inundate the steep slopes.

Demand for real estate is so high that there are currently no houses on the market for sale and only two condos—a stark difference from the 40-50 units for sale in the wider area at any given time in the past, says Patrick Werry, an agent with Century 21 Riverstone. Home prices have risen 40% over the past year in this resort village of about 700 homes.

“Everyone is trying to get on the bandwagon,” says Craig Mearns of M2 Construction, which has a three-year waiting list to even start building a custom house. Its latest spec project sold out in a month, even when prices increased from $550,000 to $950,000 for a unit.

What’s happening at Schweitzer is happening all over Idaho. The state is in the midst of a ski renaissance. As its resorts expand their ski terrain and add amenities, demand for homes is booming.

“Idaho is attracting people who want a smaller resort experience—the feel that other Western resorts used to offer but don’t anymore,” says Thomas Wright, president of Summit Sotheby’s International Realty.

Idaho’s ski resorts are scattered across the state and their characters are as different as the terrain that surrounds them, from the arid, celebrity-infused Sun Valley, to the insular, pine-tree dense village of Tamarack, north of Boise.

All the way east is the wilder, remote Grand Targhee, in the Teton Range, located in Alta, Wyo., just on the border with Idaho. But the appeal of all these places is the same: low-key, uncrowded skiing with consistent snow.

Real-estate agents say the demand for ski resort homes is an offshoot of the demand for homes in Idaho overall, a movement fueled by the pandemic, with people looking for properties with more space and, in some cases, more lax Covid restrictions.

(Idaho is currently in a hospital resource crisis because of its high rate of Covid.)

Idaho’s home prices have grown 42% in the past two years—twice the national average and the highest of all the states, according to Nik Shah, CEO of Home LLC., a down payment assistance provider.

“Most of my friends are like ‘Idaho, what’s there?’ My response is, ‘exactly—it’s because you don’t know about it,’ ” says Harmon Kong, a 57-year-old investment adviser from Lake Forest, Calif.

Mr. Kong and his wife, Lea Kong, fell hard last year for Tamarack and bought two places: a ski-in ski-out, three-bedroom, three-bathroom penthouse condo in the fall of 2020 for $1.8 million, and three-bedroom, three-bathroom chalet nearby for $1.28 million.

Mr. Kong was used to skiing at Heavenly Ski Resort in Lake Tahoe, Calif., which he likens to Disneyland because of the crowds. At Tamarack, he says the snow is routinely powdery, there are hardly ever lift lines and there’s lots of backcountry skiing.

Opened in 2004, then shut in 2008 due to bankruptcy, Tamarack is in the midst of a resurgence. The resort’s lifts currently service about 1,000 acres of skiable terrain and it has applied to the U.S. Forest Service for permits to add seven to nine new lifts, including a gondola, and more than double its size by adding 3,300 new acres of ski terrain and a new summit lodge.

Building is underway on ambitious, multiphase residential development projects, which will result in 2,043 residential units, including about 1,000 hotel rooms and a mix of condos, estate homes, townhomes, cottages and chalets.

Tamarack is in the process of starting a charter school. The average sold price for a home in Tamarack, which has about 450 homes in all, has grown 80% over the past two years, according to the Mountain Central Association of Realtors.

To attract more skiers, this past year Tamarack joined the Indy Pass, which includes small, independent resorts around North America.

The resort’s president Scott Turlington is aiming for 500,000 skier visits over the next couple of seasons (up from 120,000 last season), which he acknowledges might make him persona non grata among some of the current homeowners. “If I do my job properly I won’t be the most popular person,” he says.

Still, Mr. Turlington says, “We want to maintain our rugged individualism and independent spirit. It’s a very different feeling here than at one of the top resorts.”

The top ski resort in Idaho is Sun Valley. In fact, Ski Magazine readers voted Sun Valley the top ski resort in Western North America in 2021, in part because of its comparably short lift lines.

It’s located in an arid, high-altitude and desert-like environment and its famed Sun Valley Lodge has walls lined with photos of celebrities like Marilyn Monroe, Ernest Hemingway and Tom Hanks. Business moguls and world leaders convene there every summer for the annual Allen & Company conference.

Sun Valley has also been growing its ski operations. Last season, it added 380 acres of skiable terrain on Bald Mountain and a new high-speed chairlift. It became a partner in the Epic Pass, which includes mountain resorts like Colorado’s Vail, Utah’s Park City and Whistler in Canada, a move to bring more skiers to the mountains.

Sun Valley Resort’s vice president and general manager Pete Sonntag says the resort has no plans to expand further for now. “Our goal is never about competing for the most skiers. It’s about improving the guest experience,” he says, adding, “The remote location will keep it from feeling overrun.”

But, like many resort towns, the issue of development and affordable housing is a hot topic right now. “There’s a huge concern about people getting priced out,” says Katherine Rixon, a real-estate agent with Keller Williams Sun Valley. Property values have appreciated so much that many owners of rental properties are cashing out of the market, leaving their tenants having to find a new place to live in an already tight rental environment.

And at the same time, rental rates have doubled in the past year. There are a number of government and nonprofit groups working on increasing housing for the workforce, she says.

The number of sold homes was up 71% in August compared with a year earlier, the median price was up 20%, and the number of homes for sale down 56%. A three-bedroom, three-bathroom townhouse Ms. Rixon sold at Sun Valley last year for $2 million just resold for $3.6 million.

“People here complain when there’s four people in the lift line,” says Jean-Pierre Veillet, a real-estate developer. He moved with his family this summer from Portland, Ore., to Bellevue, about half an hour from Sun Valley’s main town of Ketchum, in part because his 15-year-old son Oliver is a ski racer and was attending a boarding school in the area.

Mr. Veillet, 50, and his wife, Summer Veillet, 45, bought a four-bedroom, two-bathroom, 3,000-square-foot house with a library, a three-car garage and a barn on 10 acres for $1.3 million in March. They’d been looking for a house in Ketchum and Hailey, the two towns in the area which are closer to the slopes, but gave up after not finding anything for a year.

Mr. Veillet still works in Portland, and even though that’s not far geographically, getting back and forth is strenuous because there are no nonstop flights to the small Sun Valley airport.

The Veillets say there are pros and cons of living there: the skiing is great, Oliver is thriving, and their younger son, Zealand, who is 10 and is home-schooled, is getting a great education from the growing, fishing and renovating the family is doing.

On the other hand, the internet is terrible, there can be fierce windstorms and there’s no food delivery service. “It’s been a hard transition. It can be hard to slow down and make a change in life,” says Mr. Veillet.

David and Kimberly Barenborg just moved to Ketchum, into a five-bedroom, five-bathroom, over 4,000-square-foot log cabin-style house with a guest cottage in a quiet neighborhood right along a stream. They bought it for about $4 million in August after they sold their house in the Seattle suburb of Mercer Island.

Mr. Barenborg, 60, who co-founded a financial advisory firm, wanted somewhere that had sun, felt safe and where he could ski, bike and fish. “It’s just play time,” he says. “I’m so happy here.”

The only catch is the threat of development on a 65-acre dog park and green space that’s directly across the creek from their new home. He is working to help the town raise the $9 million the developer is asking for the property.

He says the process has been slow going but the community is starting to see the value of protected green space. “Everyone is overwhelmed by what’s going on,” says Mr. Barenborg, referring to the rapid growth that’s stressing the town’s infrastructure.

The rapid growth is also increasing jobs, but Heidi Husbands, a council member in Hailey, says Sun Valley is currently facing a shortage of workers because people can’t afford to live there anymore. Ketchum approved funding for an affordable housing project, but it is still controversial. At one point the town considered allowing workers to put tents in a park, but that idea was canceled.

Some residents of Schweitzer are also worried about more crowds, traffic and a shortage of housing. The resort, owned by Seattle-based McCaw Investment Group, just sold out a 35-lot subdivision and broke ground on an addition to a condo building. In a few weeks, it will start building a new residential neighborhood with cabins before embarking on several others later next year. In five to 10 years, the resort plans a whole new area, with four new lifts and a new lodge.

The potential impacts from climate change are also an issue. Schweitzer CEO Tom Chasse says, “Strategically, we are concerned about the snow level. We are seeing a change in precipitation. The snow lines have been moving up for the last few seasons. So we want to make sure we have lift access to the higher elevations and we are doing feasibility studies on adding snow-making on the lower levels.”

However, Mr. Chasse says the resort has plenty of room to grow. “We want to increase our sophistication level,” he says.

Updated: 11-2-2022

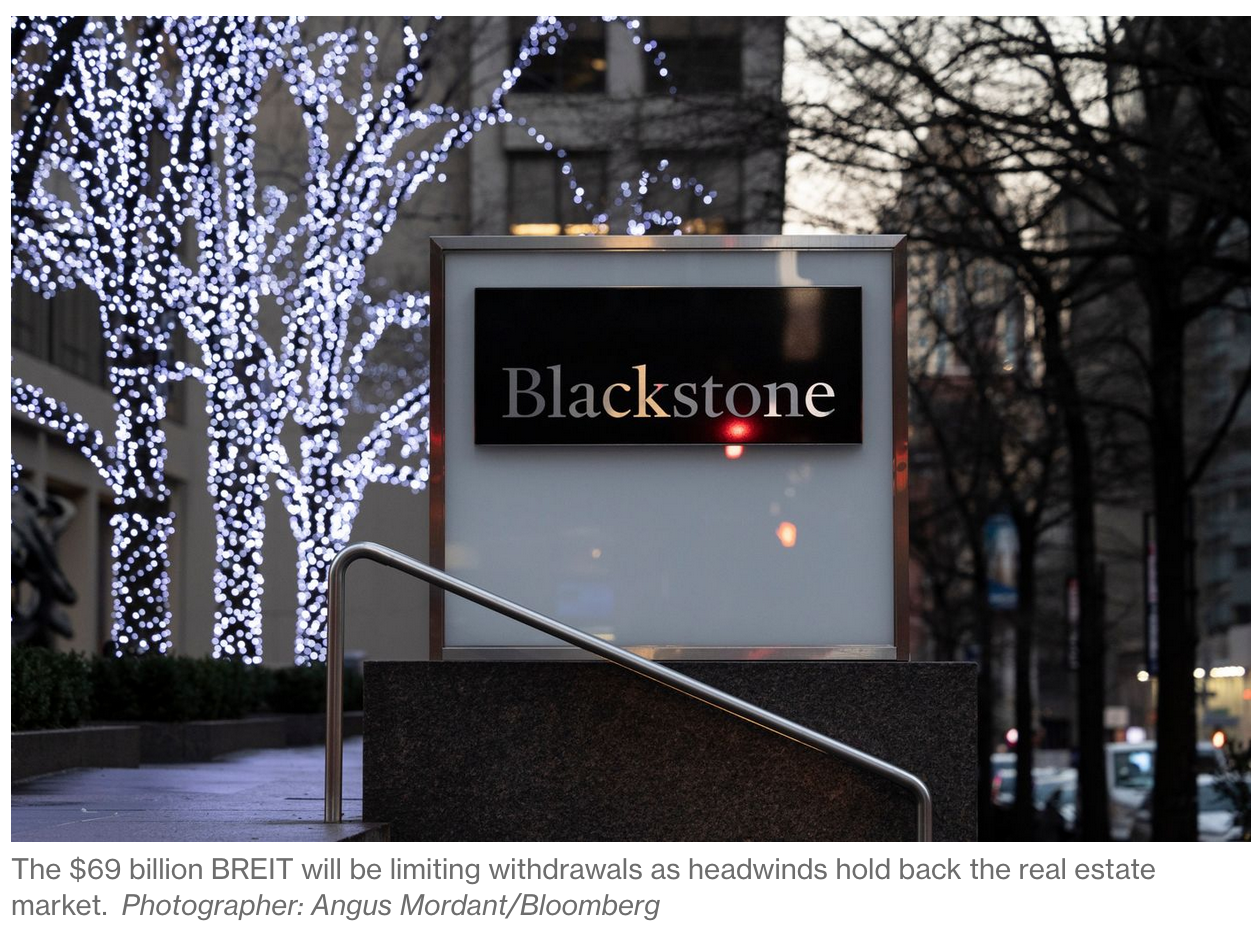

Blackstone’s $70 Billion Real Estate Fund for Retail Investors Is Losing Steam

A retail boom that supercharged private equity and real estate is slowing, challenging one of the firm’s most ambitious efforts.

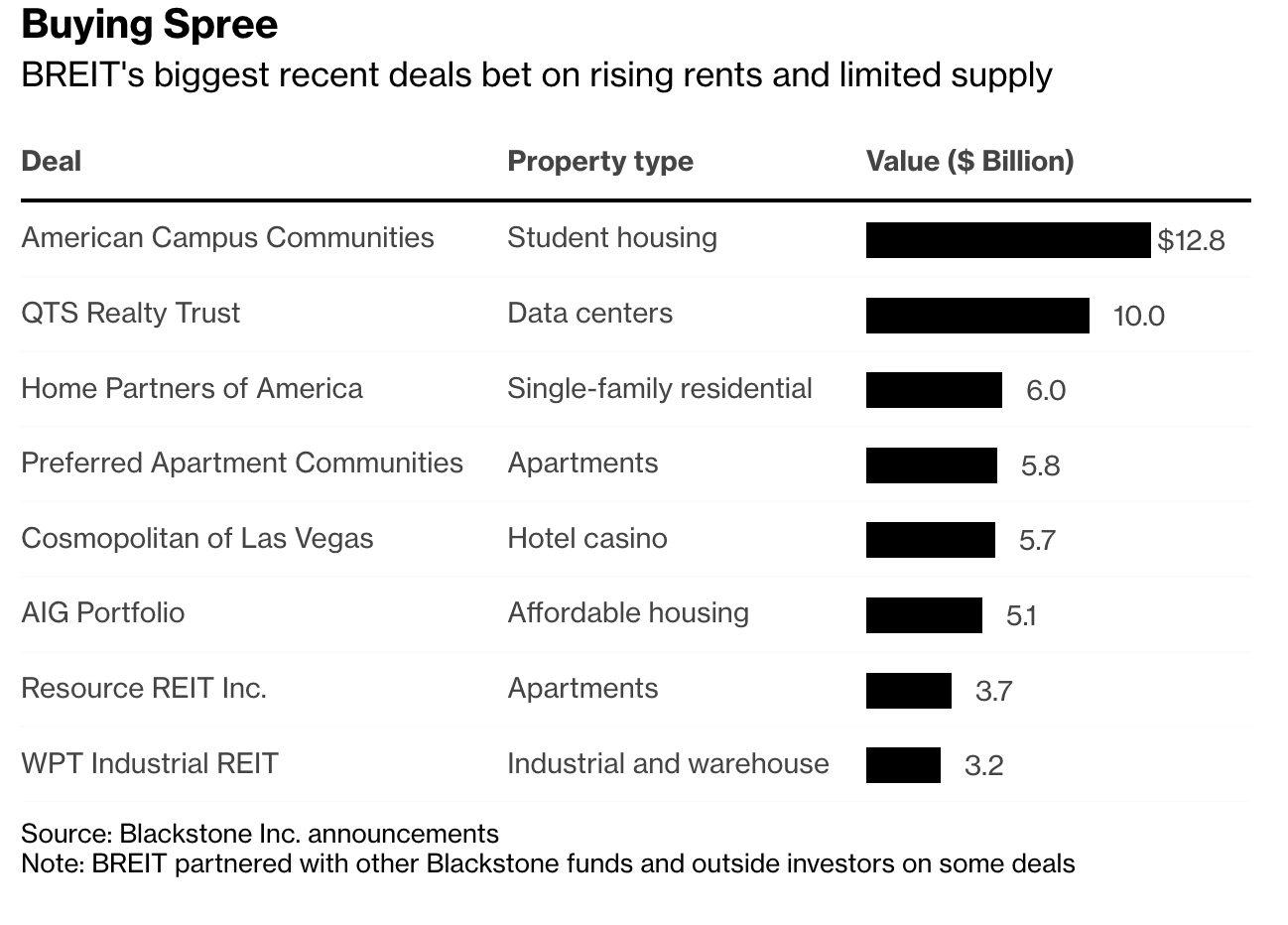

In just over five years, a Blackstone Inc. real estate fund for small investors has turned into a $70 billion force in the US economy.

It has swallowed up apartments, suburban homes, dorms, data centers, hotels and shopping centers. It owns Las Vegas’s lavish Bellagio hotel and casino; a 76-story New York skyscraper designed by Frank Gehry; and a sprawling Florida complex for interns working at the Walt Disney World Resort.

Unlike with many real estate investment trusts, its shares don’t trade on exchanges. But fueled by billions of dollars from affluent individuals, Blackstone Real Estate Income Trust has become one of the firm’s top profit drivers, expanding property investing in private markets to the masses.

Now, the money machine is facing its biggest test. Rising interest rates threaten to drag down property values and make cheap debt harder to come by. The Federal Reserve hiked its key rate by another 75 basis points on Wednesday and said “ongoing increases” will likely be needed.

Even though the BREIT strategy is outperforming stocks — total net returns for its most popular share class were 9.3% in the nine months ended September — inflows are slowing and redemptions are up.

Wealth advisers at some banks are growing cautious about client exposure to more illiquid investments. At UBS Group AG, some advisers have been shaving their exposure to BREIT after the fund’s massive growth made it too big a piece of clients’ savings, according to people close to the bank.

Staffers at Bank of America Corp.’s Merrill Lynch have been reviewing client portfolios more closely in this market to assess customers’ exposure to REITs that don’t trade on exchanges, other people said.

After years of attracting investors chasing yield at a time of rock-bottom interest rates, BREIT is coming under new pressure. It has thresholds on how much money investors can take out, meaning if too many people head for the exits, it may have to restrict withdrawals or raise its limits.

BREIT was built to weather challenging markets, said Nadeem Meghji, head of Blackstone Real Estate Americas, with its portfolio heavily weighted toward rental housing and warehouse assets in the US Sun Belt.

“This is exactly what you want to own in an environment like we are in today,” he said in a statement.

The REIT has piled into $21 billion worth of interest-rate swaps this year to hedge against higher debt costs. Such swaps have appreciated by $4.4 billion, helping to buoy the portfolio’s overall value.

BREIT “is operated with substantial liquidity and is structured to never be a forced seller of assets,” Meghji said. “All of this enables BREIT to deliver outstanding performance for its investors.”

Blackstone executives are personally invested: President Jon Gray has put $100 million more of his own money in BREIT since July, as has Chief Executive Officer Steve Schwarzman, according to a person close to the company. All told, the firm’s employees have some $1.1 billion of their own money in the REIT.

Still, money going into BREIT fell sharply in the third quarter. It took in $1.2 billion in net flows, down from roughly $7.7 billion in the year-earlier period. Investors added about 50% less new money.

Withdrawals have risen approximately 15-fold. A chunk of redemptions have been tied to Asian investors seeking cash in volatile markets, the person close to the firm said.

Blackstone set up BREIT as a semi-liquid product. It has an overall limit on investors cashing out of 2% of the fund’s net asset value each month, or 5% each quarter, although the fund’s board has final discretion to raise or lower these thresholds.

In June, the most recent date where monthly data was publicly available, the REIT had redemption requests of 1.96% of the fund.

If BREIT were to limit investors’ ability to take out money, it would send ripple effects through the real estate world because of the fund’s size and importance as a bellwether for financial markets.

“It doesn’t mean it’s bad, wrong, or it’s going to happen tomorrow,” said Rob Brown, chief investment officer for Integrated Financial Partners, a wealth advisory firm based in Waltham, Massachusetts. But some retail investors may be caught off guard if they assumed they could get their money when they wanted, he said.

Concerns about sluggish fundraising and a broader slump in dealmaking have been weighing on Blackstone shares: The stock is down 31% this year, after dipping 2.8% to $89.76 at 11:48 a.m. on Thursday, exceeding the 22% decline in the S&P 500.

Behemoth Rising

BREIT’s launch in 2017 was seismic for nontraded real estate investment trusts. That was a corner of finance with a tarnished reputation because of high fees, low returns and an accounting scandal that roiled the then-largest sponsor of such REITs.

The pitch for the trusts can be compelling: A person can take a stake in a swath of properties and collect dividends, benefiting from rising real estate values without stock-market gyrations.

BREIT stood out. It let smaller investors come in with as little as $2,500 and stay on as long as they wished, allowing for limited redemptions each month. That’s a contrast to most buyout funds that take in money from pensions and big investors, which require multiyear commitments. BREIT was less expensive than unlisted REITs of its time but more expensive than typical mutual funds.

At first, people inside the firm weren’t sure if BREIT could live up to the ambitions of top Blackstone leaders.

Kevin Gannon, chief executive officer of real estate investment bank Robert A. Stanger & Co., recalls telling Blackstone staffers just after the fund’s launch: “If you don’t raise $20 billion, you should be ashamed of yourselves.”

Blackstone employees at the meeting looked concerned, Gannon said, “as though I put a target on their backs.” Gray, one of the fund’s masterminds, had a different response, telling lieutenants: “I told you so.”

BREIT gave Blackstone an early mover position in the untapped multitrillion-dollar market for individual investors. It was a key plank of the firm’s bid to become a bigger retail brand.

Other private equity firms followed suit over the years in pursuit of individuals’ cash, while the fundraising circuit for pensions and large investors’ money became more crowded.

The entry of the world’s largest alternative-asset manager into nontraded REITs sparked an arms race, with Starwood Capital Group, KKR & Co. and others launching similar funds.

When markets surged, BREIT and other rivals in 2021 and early 2022 were key players in a fundraising boom “as action-packed as Pete Davidson’s love life,” analysts with real estate analytics firm Green Street wrote in May, referring to the comedian who dated Kim Kardashian and Ariana Grande.

When someone invests money in BREIT, they put in more than $150,000 on average, according to a person familiar with the matter. The constant flows fueled a hunt for acquisitions that one Blackstone real estate staffer described as unrelenting.

BREIT was Blackstone’s biggest driver of earnings in the last quarter of 2021. The fund takes in 1.25% of assets in fees and 12.5% of returns — higher fees than traditional stock-and-bond funds. Advisers have won big too, collecting upfront commissions on some BREIT customers.

Publicly-traded companies have been a frequent target, including Preferred Apartment Communities Inc. and university-housing landlord American Campus Communities Inc.

The student-dorm deal accounted for almost $13 billion of the $21 billion of announced REIT take-private transactions in the first half of 2022, according to Jones Lang LaSalle Inc.

BREIT parked some 20% of its money into warehouses and logistics centers, in a bet that e-commerce would buoy rents. Even more money went to residential property, which now accounts for about half of its portfolio.

Executives have a thesis that a housing shortage would give property owners leverage to constantly reset rents. This way, the fund could squeeze enough cash to offset inflation, which Gray had predicted in early 2021 would be persistent and stubborn.

BREIT last year took over Home Partners of America, which now owns 30,000 homes. It was a platform through which Blackstone could say it was giving renters a chance to to become homeowners.

The REIT expanded further into affordable housing with a roughly $5.1 billion purchase of properties from American International Group Inc. last year.

Blackstone executives concede that going forward, landlords across the board will find it harder to raise rents for apartments and single-family homes at the same pace as before, said people close to the firm.

But rental rates for warehouses, especially those in urban areas, are poised to continue to show strong growth as companies look to shore up inventory with supply chains snarled, the people said.

Rising interest rates have led BREIT to lower expectations on what it could earn from exiting its bets, though rising cash flows from rents have supported property values for now.

Rising Rates

With markets churning, some deals that BREIT was chasing earlier this year don’t make sense. BREIT and others had been looking at a sizable block of affordable housing apartments this year but recently lost interest, according to a person familiar with the matter.

BREIT ramped up swap trades to counter the effect of rising interest rates across the fund’s portfolio. The swaps will generate cash for BREIT as long as interest rates are above certain levels.

A floating-rate mortgage on the Cosmopolitan of Las Vegas, a 3,000-room hotel BREIT acquired alongside partners for $5.65 billion, has risen to about 7%, up almost two percentage points from the loan’s initiation in June.

Another adjustable-rate loan on a slice of debt on its takeover of American Campus Communities has also climbed to about 7%. Those increases have been canceled out with interest rate swaps, according to people familiar with the matter.

Those swaps, combined with cash flows from BREIT’s properties, have helped bolster the fund’s value. Meghji said the firm has locked in or hedged 87% of BREIT’s debt for the next six and a half years.

Blackstone representatives told one wealth management group recently that BREIT plans to consider doing more deals as a debt investor than it has before. That’s in contrast to buying equity, in an effort to protect money better in a downturn.

BREIT’s 9.3% net return in its most popular share class in the nine months ended September stand in stark contrast with publicly traded REITs, which tumbled about 30% in value this year through September. Meanwhile, BREIT’s returns are narrowing compared with the same period last year, when that share class delivered 21.5% returns.

“Before interest rates were so low and BREIT always had growth,” said Gannon of Robert A. Stanger. “Now it’s a bit more difficult.”

Updated: 12-1-2022

Blackstone Limits Redemptions From Real Estate Vehicle, Stock Sinks

Blackstone Real Estate Income Trust Inc. posts letter saying withdrawals requested in October exceeded limits.

Blackstone Inc. shares took a big hit after the investing giant’s real-estate fund aimed at wealthy individuals said it would limit redemptions.

Blackstone Real Estate Income Trust Inc., more commonly known as BREIT, said Thursday in a letter posted to its website that the amount of withdrawals requested in October exceeded its monthly limit of 2% of its net-asset value and its quarterly threshold of 5%.

That spooked Blackstone shareholders, who sent the company’s stock down nearly 10% at one point Thursday morning. More recently, they were down 7.1% Thursday, giving the company a market value of more than $100 billion.

BREIT, a nontraded real-estate investment trust whose net-asset value now totals $69 billion, has been one of Blackstone’s biggest growth engines in recent years.

It has helped the private-equity firm attract a new class of investors who might not be wealthy enough to invest in its traditional funds but want access to private assets.

BREIT is designed to generate steady cash flows for its investors. It has delivered net returns of 9.3% year-to-date and 13.1% annually since inception, with an annualized distribution rate of 4.4%, according to its website.

Despite those healthy returns, the vehicle has had an increase in redemption requests from investors in recent months.

The fund has invested heavily in rental housing and logistics in the Sunbelt region of the U.S. where valuations have held up, he said.

Blackstone executives have said BREIT’s withdrawal thresholds were designed to prevent it from having to become a forced seller. The firm said the vehicle has $9.3 billion of immediate liquidity and $9 billion of debt securities it could sell if needed.

BREIT said separately on Thursday it agreed to sell its 49.9% stake in MGM Grand Las Vegas and the Mandalay Bay to its co-owner Vici Properties Inc.

The deal values the properties at $5.5 billion and will deliver a profit of more than $700 million to Blackstone, which bought them less than three years ago. The deal was struck at premium to where BREIT was valuing the assets on its books, according to a person familiar with the matter.

“Our business is built on performance, not fund flows, and performance is rock solid,” a Blackstone spokesman said in a statement. “BREIT has delivered extraordinary returns to investors since inception nearly six years ago and is well positioned for the future.”

The sale of the casino properties will give BREIT $1.27 billion in cash that it can use in part to cover the uptick in its redemptions, The Wall Street Journal reported.

With the stock market down and bonds performing poorly, wealthy investors in need of liquidity have few areas of their portfolio where they can sell at a profit. The bulk of the redemption requests for BREIT are coming from Asia, according to a person familiar with the matter.

Updated: 12-2-2022

Why Blackstone’s $69 Billion Property Fund Is Signaling Pain Ahead For Real Estate Industry

The property industry is grappling with a pullback from investors, financing challenges and even more layoffs.

Pain is deepening across the US real estate industry.

Two of the biggest players — Blackstone Inc. and Wells Fargo & Co. — took steps this week to contend with weaker demand as the industry faces a rapidly cooling property market, rising interest rates and waning investor appetite.

The well-heeled investors in the $69 billion Blackstone Real Estate Income Trust Inc. learned Thursday the fund will limit withdrawals as people seek to pull money from what’s been a cash magnet for one of the largest owners of real estate globally.

Also Thursday, Wells Fargo, the biggest home loan originator among US banks, confirmed it’s cutting hundreds more mortgage employees as soaring borrowing costs crush demand.

“It’s a one-two punch,” Susan Wachter, real estate professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, said in an interview. “Both are realistic pullback responses to the overall economic weakness we’re seeing now as well as the spike in interest rates.”

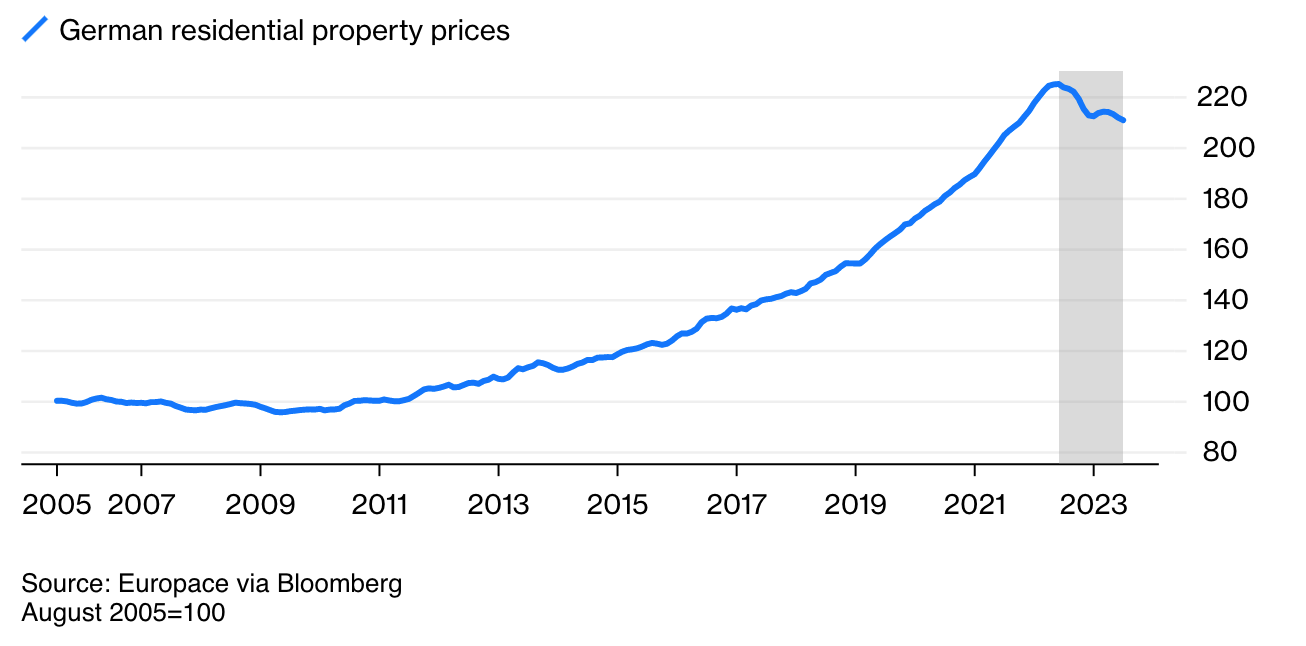

In the past decade, the real estate industry reaped the benefits of the Federal Reserve’s policy of low rates. Homebuyers, taking advantage of record-low borrowing costs, went on a spree that fueled double-digit price gains.

Ultra-low rates also drove a refinancing boom that put more money in homeowners’ pockets and spurred the creation of jobs for mortgage brokers, title insurance agents and appraisers.

Now, real estate has been among the hardest-hit sectors of the Fed’s campaign to quash inflation by boosting interest rates at the fastest pace in decades.

In the housing market, mortgage rates that have doubled this year are sidelining potential buyers and causing sellers to pull back on new listings. A measure of prices has dropped for the last three months, while pending home sales have fallen for five months in a row.

The volume of mortgages with rate locks plunged 61% in October from 2021 levels, according to Black Knight Inc.

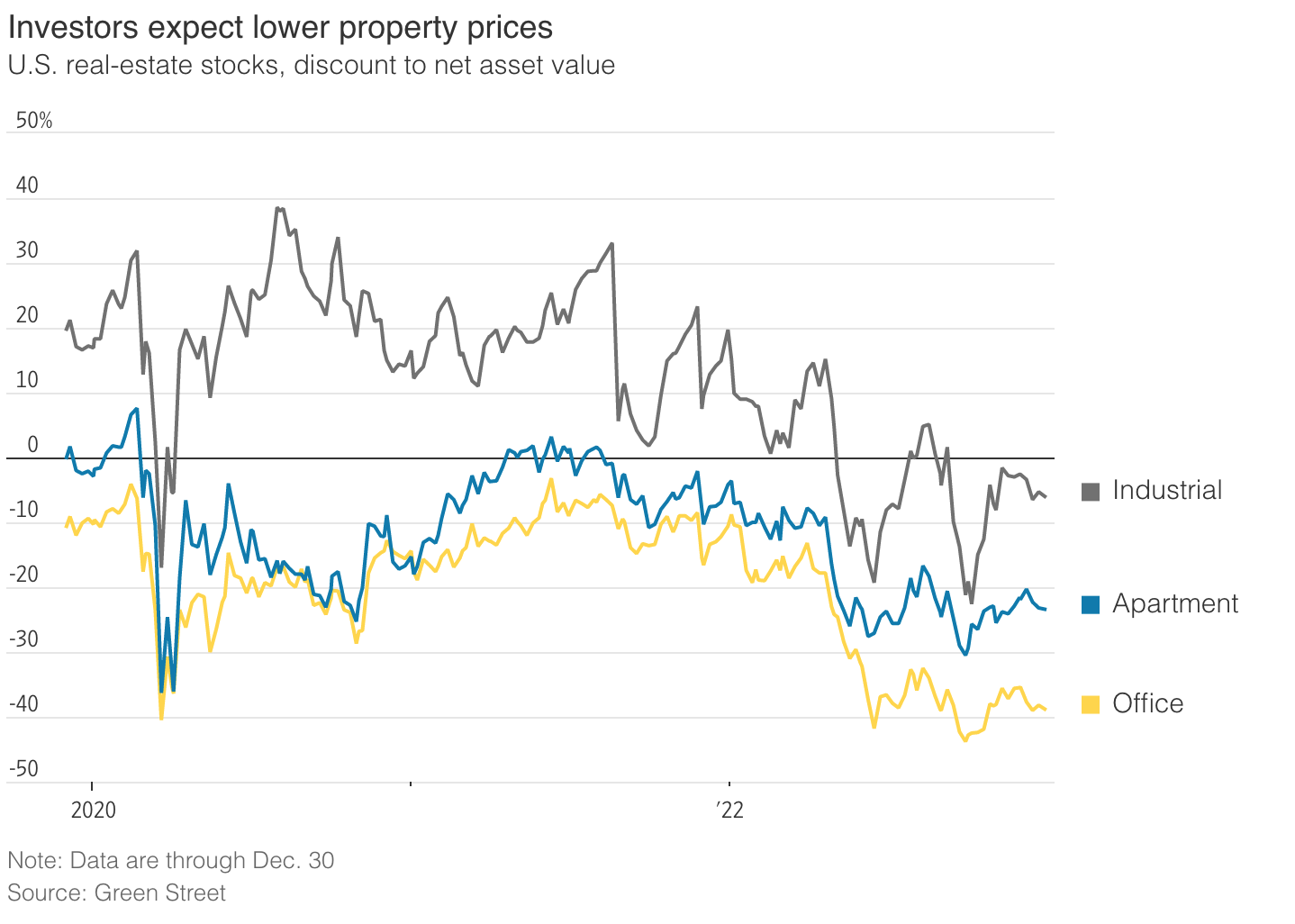

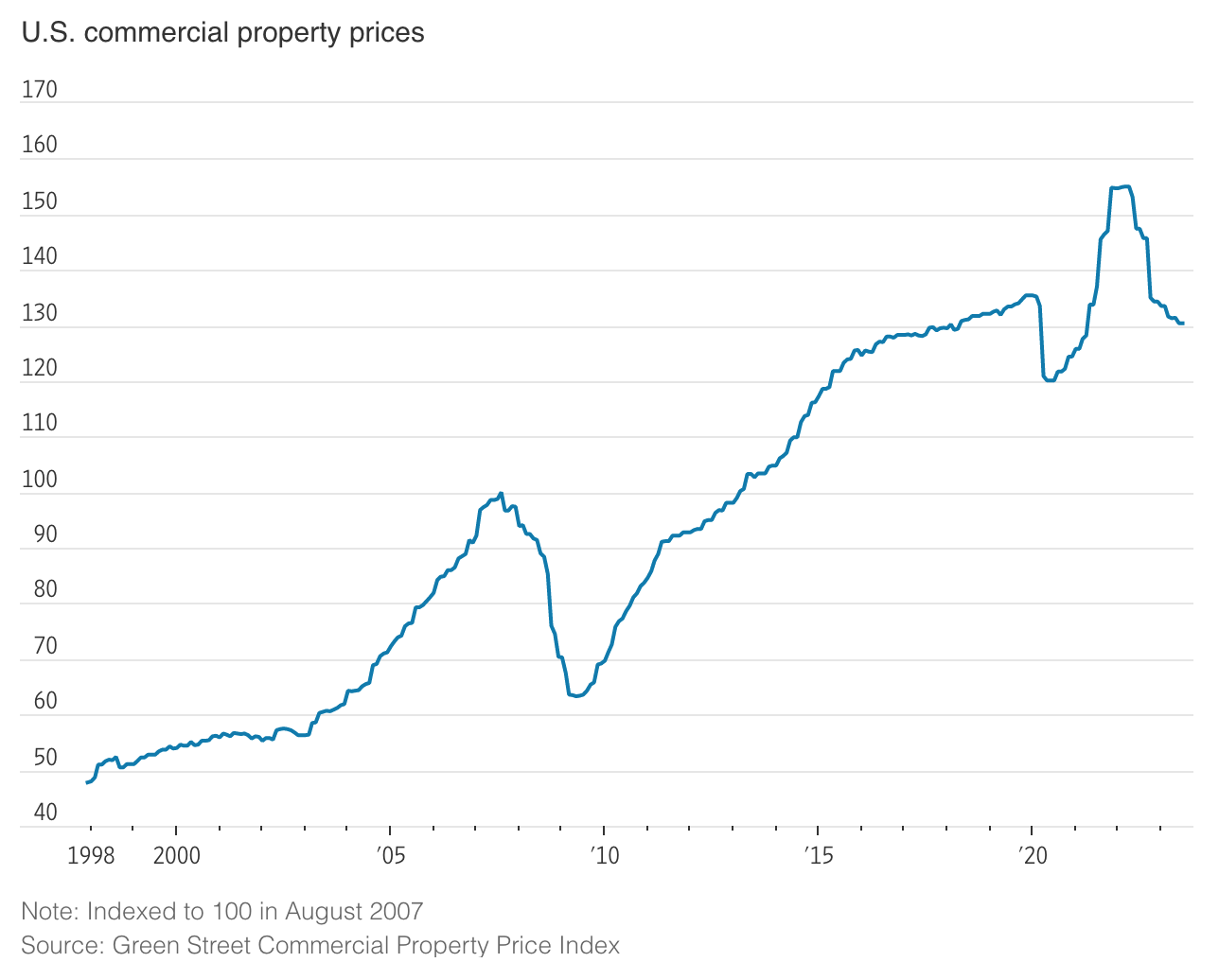

Commercial real estate is also feeling the sting. Property prices have slumped 13% from a peak this year, according to Green Street’s October price index.

The financing environment has become trickier as some big lenders have scaled back, leading property owners such as a Brookfield Asset Management Inc. unit to warn that it might struggle to refinance certain debt.

Industry Fallout

The industry fallout has been wide-ranging. Reverse Mortgage Funding, a home lender backed by Starwood Capital Group, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy this week.

Layoffs have been widespread. Opendoor Technologies Inc., which pioneered a data-driven spin on home-flipping known as iBuying, laid off about 18% of its workforce and wrote down the value of its property holdings by $573 million.

Brokerage Redfin Corp. went through two rounds of layoffs and shuttered its iBuying business, while competitor Compass Inc. also made deep cuts to its technology teams in a quest for profitability.

Layoffs only tell part of the story of the pain. While mortgage firms and real estate technology companies cut costs by firing workers, real estate agents make up a large share of the industry’s workforce.

They’re usually considered independent contractors and depend on commissions for a living. They don’t show up in layoff tallies but are also exposed to slowing home sales.

“There are hundreds of thousands of real estate agents who are not going to be practicing because people are buying and selling fewer homes,” said Mike DelPrete, a scholar-in-residence at the University of Colorado Boulder. “It’s like a silent culling of the ranks.”

Search For Yield

When interest rates were ultra low, investors turned to commercial real estate as a source for higher yields than they could get by owning Treasuries and other low-risk bonds.

That was part of BREIT’s appeal, drawing in high-net-worth clients lured by the 13% annualized returns in one major share class through October.

BREIT raked in money to buy apartments and industrial buildings, properties that the private equity firm bet would keep growing in value because demand outstripped supply.

People who couldn’t afford to buy a house needed to rent, the reasoning went, and shoppers increasingly buying online drove up the need for warehouse space.

“Our business is built on performance, not fund flows, and performance is rock solid,” a Blackstone spokesperson said Thursday after the firm announced the redemption limits.

Much of the money withdrawn from BREIT was from overseas, with offshore investors redeeming at eight times the rate of US ones in the past year. Blackstone shares dropped 2.7% Friday to $82.76 at 10:47 a.m., after tumbling 7.1% the day before.

Commercial-property owners are getting hit with financing challenges after years of paying for deals with cheap loans. Expensive debt has pushed some borrowers into negative leverage, which means that debt costs are outpacing expected returns.

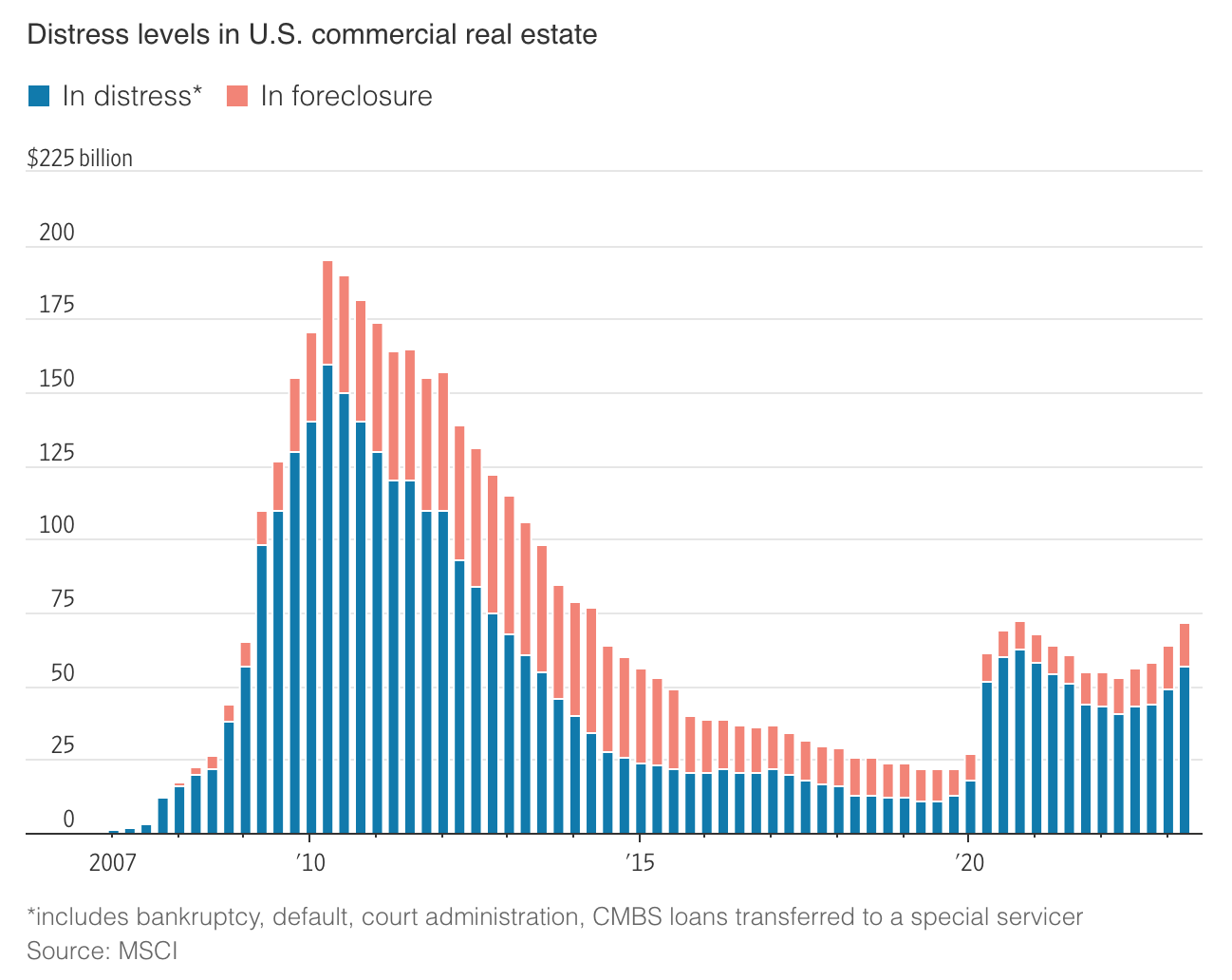

Dealmaking has also frozen, with transaction volume plunging 43% in October from a year earlier, according to MSCI Real Assets.

“With the benefits of leverage severely limited and owners who are not being forced to sell, the price expectations gap between sellers and potential buyers has been wide enough to limit deal closings,” Jim Costello, an MSCI economist, wrote in a Nov. 16 report.

Despite all the pain points, the housing and commercial real estate industries are in better shape than in some previous downturns, with more tightly underwritten loans and less of a risk of markets being oversupplied.

With BREIT, the fund is still outperforming the S&P 500 Index, even as investors increasingly want out. And Thursday’s announced sale of a stake in two Las Vegas hotels is expected to generate roughly $730 million in profit for BREIT shareholders, Bloomberg previously reported.

Relative Value

What’s changing most drastically across the industry is the relative value of real estate to other investments.

Thanks in part to the Federal Reserve’s hiking campaign, investors have other places to earn money that could generate more yield than in years past and tend to be more liquid than commercial real estate, including Treasuries, investment-grade bonds, and mortgage-backed securities.

“Real estate is quite cyclical,” Wharton’s Wachter said. “It’s bad for real estate when rates go up and you can get higher yields from Treasuries and other assets.”

Updated: 12-12-2022

Blackstone’s BREIT Highlights Looming Dangers of Private Funds

In a world increasingly demanding liquidity, Blackstone is selling illiquidity.

declared themselves baffled that so many retail investors want their money back from its giant private property fund, given its strong performance.

They shouldn’t be surprised. The very design of the fund encourages investors to withdraw when they see others doing so. My worry is, those same incentives could hit other parts of the financial system as central banks pull back from easy money.

A slow-motion dash for cash is under way across the whole of finance as the Federal Reserve sucks liquidity out of the system. Most harmed will be those who piled into private assets without thinking about how much cash they might need.

The basic principle of the Blackstone Real Estate Income Trust, or BREIT, is that it took $46 billion from ordinary investors, added debt and bought a bunch of property, mostly Sunbelt housing and warehouses. It was good at it, or perhaps lucky, and the value of the fund went up a lot, so it was very popular.

But this year mortgage rates soared and recession fears rose, and house prices began to come down. They have dropped only a bit so far, and not everywhere, but enough to make it less obvious to investors that they ought to be piling cash into a leveraged bet on property prices.

Blackstone isn’t dumb, and it thought in advance about the possibility that one day people would want their money back. The contracts limit withdrawals from BREIT to 2% of the fund each month, or 5% a quarter, to avoid the need for fire-sales of property. Now people want some of their money back, and the limits have kicked in.

The problem is that investors in BREIT now know that other investors in BREIT (and a similar fund, from Starwood Capital Group, known as SREIT) are trying to withdraw.

Just as with a bank run, an investor who thinks others will try to withdraw should get out first. Even those who think everything will soon calm down—and there are reasons to think it might—should still be concerned about the effects of others leaving.

It isn’t just BREIT. Private credit funds became wildly popular over the past decade and mutual funds bought into private equity, part of increasingly creative attempts to make money in a world of zero interest rates. Some, which hold hard-to-trade assets and allow withdrawals, are also vulnerable to self-fulfilling fears about liquidity.

I See Four Areas Of Vulnerability In BREIT That Could Apply To Other Funds: