Affordable Housing Crisis Spreads Throughout World (#GotBitcoin)

Demand For Affordable Housing Has Spurred Architecture And Construction Firms To Develop New Techniques, Such As These Y:Cube Modular Units In The U.K. Affordable Housing Crisis Spreads Throughout World (#GotBitcoin)

Shortages persist despite millions of dollars invested and hundreds of thousands of units built. Affordable Housing Crisis Spreads Throughout World (#GotBitcoin)

Cities around the world, from New York to London to Stockholm to Sydney, are struggling to solve growing affordable housing crises.

Related:

Emergency Rental Assistance Program

Home Flippers Pulled Out of U.S. Housing Market As Prices Surged

Housing Insecurity Is Now A Concern In Addition To Food Insecurity

Smart Wall Street Money Builds Homes Only To Rent Them Out (#GotBitcoin)

No Grave Dancing For Sam Zell Now. He’s Paying Up For Hot Properties

Investors Are Buying More of The U.S. Housing Market Than Ever Before (#GotBitcoin)

Cracks In The Housing Market Are Starting To Show

Biden Lays Out His Blueprint For Fair Housing

Housing Boom Brings A Shortage Of Land To Build New Homes

Wave of Hispanic Buyers Boosts U.S. Housing Market (#GotBitcoin?)

Phoenix Provides Us A Glimpse Into Future Of Housing (#GotBitcoin?)

OK, Computer: How Much Is My House Worth? (#GotBitcoin?)

Sell Your Home With A Realtor Or An Algorithm? (#GotBitcoin?)

Acute shortages are persisting despite millions of dollars invested and hundreds of thousands of units built. Some countries have focused on solutions promoting unshackled free markets while others have turned more to rent control and subsidies.

But no approach has solved the crises and most have other negative ripple effects.

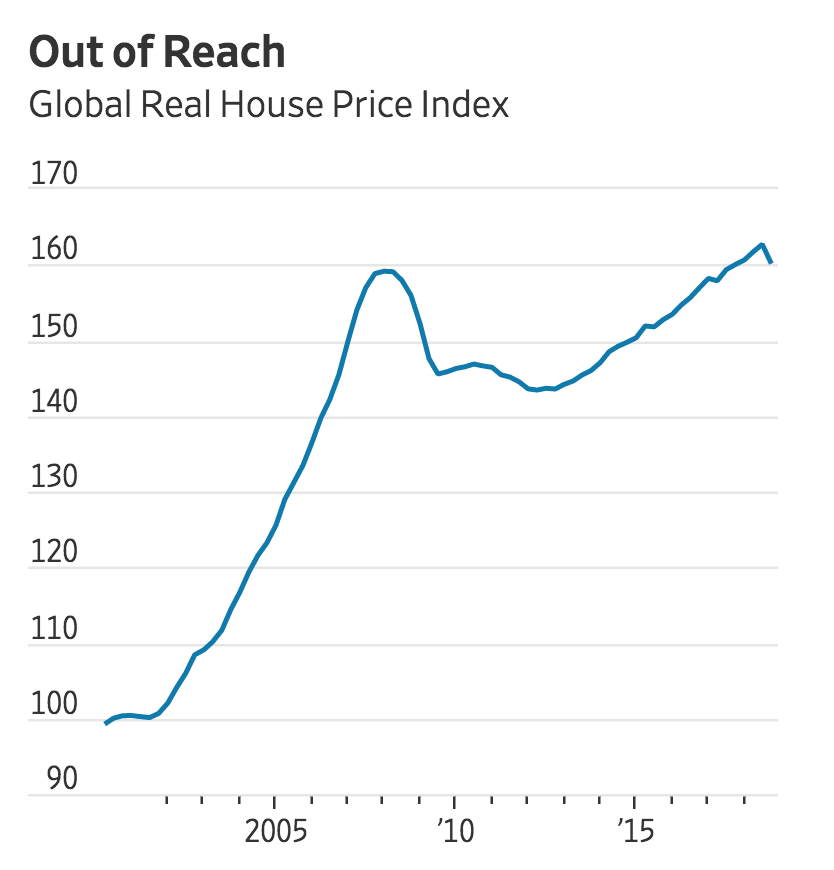

Across 32 major cities around the world, real home prices on average grew 24% over the last five years, while average real income grew by only 8% over the same period, according to Knight Frank, a London-based real-estate consulting firm.

Economists say it is striking that affordability has worsened even during a period of global prosperity over the last six years. But income growth has been unable to keep pace with a rapid run-up in home prices.

Inflation-adjusted home-price gains have outpaced income growth over the last five years in 18 out of 25 world cities in the Knight Frank report. In two other places—Dubai and São Paulo—real incomes have fallen more than home prices, creating similar challenges.

Migration patterns have been partly to blame. Cities have thrived over the last decade, as jobs and people have migrated back downtown from far-flung suburbs.

“Global cities are suffering from affordability issues, partially as a result of their own success,” said Liam Bailey, global head of research at Knight Frank.

Soaring prices are also being fueled by increasing demand from investors. These have included domestic “mom-and-pop” investors buying second homes and foreign investors taking advantage of new technologies and an increasingly globalized financial system.

Governments haven’t had the money to subsidize new supply. Most budgets are strained by an aging population with growing pension and health-care needs.

The private sector has also fallen short. In numerous hard hit cities, developers have built hundreds of thousands of units but most of them are priced at upscale buyers and renters, not the middle and working class people who are being priced out of the market.

Tokyo is one of the few cities in which supply has kept up with demand, keeping a crisis from developing. But that is due largely to deregulated housing policies that other countries would have a hard time reproducing.

“It goes against the notion of planning and developing cities in an orderly fashion,” said Laurence Troy, research fellow at the City Futures Research Centre of the University of New South Wales, Australia.

To keep a lid on prices, governments in some countries, including Canada and Australia, have added taxes aimed at curbing purchases by investors or foreigners. Buying by Chinese investors, who have been particularly active during most of the decade, has declined because of recent capital controls in that country.

These trends, coupled with a glut of luxury supply, have damped prices in some of the frothiest markets. In Sydney, the median house price at the end of last year was about $1.1 million Australian dollars ($780,000 U.S.), down about 11.3% from the peak hit in 2017, according to CBRE Group Inc.

A few years ago, prices in Vancouver and Toronto were growing by up to 30% annually. But today they’re virtually flat, thanks in part to a steep sales tax aimed at foreign buyers and tightened rules to make it more difficult for families to qualify for mortgages.

“Basically what we are doing now is we are undoing crazy years,” said Benjamin Tal, deputy chief economist at CIBC World Markets Inc.

Still, while these markets have cooled, prices are unaffordable to middle-class families. In Sydney, they’re still about 12 times the median income, compared with eight to 10 in markets where prices are considered more affordable. “When you’ve gone up 90% and you come down 10%, you’re still up 80%,” said Bradley Speers, head of research for CBRE’s Australia business.

The public and private sectors are searching for new solutions. Cities such as London and New York have rezoned swaths of land to allow for more high-rise construction or relaxed rules to allow for smaller unit sizes.

Architecture and construction firms are trying out new construction techniques made possible by advances in technology. For example, U.K. architecture firm Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners is looking at ways to expand to the suburbs the modular construction techniques it pioneered with its pilot Y:Cube development.

“A lot of the neighbors looked at these and asked where they could get one in their backyard for their parents,” said Ivan Harbour, senior partner with the firm.

Interior Of A Studio In A Y:Cube Development.

Meanwhile, housing is becoming an increasingly charged political issue, with proposals to expand rent control cropping up in places such as California, Germany and London.

Affordable housing has also become a big issue in the coming Australian election, with the Labor Party advocating measures intended to boost new supply and reduce speculation. Opponents of these measures warn that they could send the softening market further into a tailspin.

In Sweden, Stefan Löfven was able to eke out reelection as prime minister earlier this year but only after agreeing to numerous policies of other parties including one involving deregulating rents for tenants in newly constructed buildings, to encourage new supply. But many don’t expect any action soon because the government coalition is tenuous.

“Given the government we have in place, it unfortunately looks like it could be another four years without anything really happening,” said Albin Sandberg, an analyst with Kepler Cheuvreux, a financial-services firm.

Updated: 10-15-2019

So You Make $100,000? It Still Might Not Be Enough To Buy A Home

A record number of six-figure-income families rent, as student debt and meager savings cloud their financial future.

For Janessa White, the American dream of a red brick house on a tree-lined street blocks from a good elementary school remains obtainable. She just has to rent it.

Ms. White and her boyfriend moved with her 7-year-old son from Missouri to Denver last year. In Missouri, Ms. White owned her home, which she bought for a little over $100,000. To buy a house like the one she rents in Stapleton, an affluent section of the Colorado capital, would cost about four times as much. Even though her household’s income is in the low six-figures, homeownership is daunting in Denver.

“It’s hard not to want to buy,” she said. “Saving for a huge down payment seems almost impossible.”

Ms. White’s household is part of a growing camp: high-earning Americans who are renting instead of buying homes. In 2019, about 19% of U.S. households with six-figure incomes rented their homes, up from about 12% in 2006, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis of Census Bureau data that adjusted the incomes for inflation. The increase equates to about 3.4 million new renters who would have likely been homeowners a generation ago.

“I can’t think of anyone we’ve rented to recently who didn’t make $100,000,” said Bruce McNeilage, who owns 148 rental homes around the Southeast and is building 118 more.

As more people forgo homeownership, there is a risk that America’s already-wide wealth gap gets worse. Home-price appreciation has historically been the way most middle-class Americans accumulated wealth. When real-estate values rose steadily in the decades after World War II, middle-class wealth surged, according to a new analysis of consumer survey data from the University of Michigan going back to the late 1940s.

“Houses are the democratic assets, roughly half of housing wealth is owned by the middle class,” said Moritz Schularick, a professor of economics at the University of Bonn and one of the authors.

It isn’t unusual for high-earners to rent in pricey coastal cities like New York and San Francisco, where sky-high real-estate prices have long limited homeownership. Yet these markets account for less than 20% of the new six-figure renters, according to the Journal’s analysis.

To accommodate well-off renters, developers have raced to erect luxury apartment buildings around city centers. Investors, meanwhile, have bought hundreds of thousands of suburban houses to turn into rentals and are increasingly building single-family homes specifically aimed at well-heeled tenants.

The average tenant of the country’s two largest single-family landlords, Invitation Homes Inc. and American Homes 4 Rent, now earns $100,000 a year, the companies say. These companies own some 133,000 houses between them in attractive neighborhoods with good school districts around growing cities, like Houston, Denver and Nashville, Tenn.

In each of those cities as well as in Seattle, Cincinnati and Ann Arbor, Mich., the number of six-figure renters doubled or better between 2006 and 2017, making them the fastest-growing segment of renters in these markets, according to the Journal’s analysis.

During that period, which began just before the housing market imploded in 2007, the number of renter households in the U.S. grew 25% while the number of homeowners was nearly flat, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Since 2017 home buyers have started returning to the market, but not nearly enough of them to offset the decade of new renters.

The big home-rental companies are betting that high earners will continue renting. Bankrolled by major property investors like Blackstone Group Inc., Starwood Capital Group and Colony Capital Inc., these companies snapped up foreclosed houses with the expectation of renting them to educated workers who could afford to pay a lot every month but perhaps not buy.

“Very early in this business, we figured out that the cost to replace the HVAC unit is, for the most part, the same on a $1,200 or $1,300 rental as it is on $1,800 or $1,900 rental,” said Dallas Tanner, chief executive and a founder of Invitation Homes.

Six-figure earners tend to be more consistent rent payers, too. Car troubles or a sick child don’t cost them hours at work and income like they can for many lower earners.

High earners also tend to stay put and are willing to absorb regular rent increases if it means not having to move their children to new schools. That translates to lower turnover and maintenance costs for the landlords. “These tenants are treating our houses as if they are their homes,” American Homes CEO David Singelyn said at a real-estate investment conference this summer in New York.

Invitation and American Homes have reported record occupancy and rent growth as well as ever-growing retention as their average renters’ income has risen into six-figure territory.

The phenomenon is being felt down the line in the rental-home business and has prompted a rush among investors to buy and build family-sized rental houses around growing cities. Investors, a mix of big and small landlords and house flippers, accounted for more than 11% of U.S. home sales in 2018, their highest share on record, according to CoreLogic Inc.

A $100,000 income is still comfortably in excess of the median U.S. household income, which was $63,179 in 2018, according to the Census Bureau. But many Americans these days are mired in debt. They have car payments, credit-card debt, health-care bills and college loans. Student debt is particularly vexing for the younger Americans who are starting families.

There is a connection between student loans and the housing bust, which isn’t lost on young home buyers. Many students took out loans because the housing crisis wiped out the equity in their parents’ homes that would have helped pay for college. Since then the amount of student debt outstanding has tripled, to more than $1.6 trillion. A couple of years ago Fannie Mae, the government-sponsored mortgage giant, made it easier for borrowers with higher debt levels to qualify for a mortgage, though recently Fannie tightened its lending standards.

Despite the concession, and low unemployment, the homeownership rate remains stuck about a percentage point below its long-term average of 65% and well below the peak of 69% reached during the last housing bubble. In the second quarter, there were 78.5 million owner-occupied housing units compared with 43.9 million that were rented, according to the Census Bureau.

Those who do want to buy a home face the additional hurdle of high prices that have surged beyond the reach of even relatively high earners in cities with strong jobs growth. Prices in 75 of the country’s 100 largest metro areas have surpassed their precrash highs, not adjusting for inflation, according to mortgage data and analysis firm HSH. Many of those cities, such as Salt Lake City and Raleigh, N.C., also have some of the fastest growth in high-paying jobs. The sharpest recovery, according to HSH, has been in Denver, where home prices have doubled since 2012 amid an influx of California tech workers and New York finance firms. Prices are nearly twice their precrash high.

It takes an annual household income of about $90,000 to afford Denver’s median-priced house, which costs around $471,000, according to HSH. But that is assuming buyers have 20%, or about $94,000, for a down payment.

“The lack of savings for a down payment in this country is grossly underestimated,” said John Pawlowski, a housing analyst at Green Street Advisors, who estimates that the typical renter’s net worth is about $5,500. “Consumer balance sheets are not good.”

In Stapleton, where Ms. White lives, the typical household income is more than $135,000. Tom Cummings, whose company manages some 240 rental homes in the neighborhood, said his typical tenant is a two-income family with children, drawn by the neighborhood’s top-rated schools. Some are recent transplants unsure if they’re staying long-term. Others can’t afford to buy, he said.

Houses can be effective wealth builders because most people borrow most of the purchase price. That leverage magnifies gains when prices are rising, but also increases losses when they fall. That explains the big decline in household wealth in the financial crisis and why people are less excited about owning a home today despite otherwise steady appreciation over the decades.

Invitation’s Mr. Tanner likens attitudes toward rental homes to those of leased autos. “Twenty years ago people thought about leasing a car and it was like a bad word. Everyone wanted to own a car,” the 39-year-old CEO said. “Today nobody cares.”

In fact, the idea that homes can lose significant value means people may treat them more like cars, which lose value every year. According to a survey by mortgage finance company Freddie Mac, just 24% of renters said it was “extremely likely” that they would ever own a home, down 11 percentage points from four years ago.

Jacob Neuberger, a 30-year-old who works in Denver for an investment firm, considered buying when he moved out of his one-bedroom downtown apartment. He and his girlfriend opted to rent a townhouse for $2,700 a month. The one next door sold for $550,000. Mr. Neuberger estimated that his costs to own would be about 20% higher than renting and that he would need the townhouse to appreciate by about 10% to cover transaction costs if he needed to sell to buy a bigger home or if he had to move for work. “The price appreciation can’t go on forever,” he said.

Madeline Smith, an executive assistant for a local real-estate investor, and her boyfriend, who works in real-estate development, nearly bought a house in Denver two years ago. They had made a quick decision to offer about $25,000 above the asking price under pressure of a bidding deadline. At the inspection, they started adding up the expenses for repairs and upkeep.

“The yard was beautiful, ” Ms. Smith, 29, said. “But who takes care of it? Do we have to come home and take care of it or hire someone? That’s more money.”

The couple backed out and she instead traveled abroad for a few months. When she returned, they rented a luxury apartment downtown and are waiting for asking prices to come down.

Investors are betting many of today’s luxury apartment dwellers will soon be looking for high-end suburban rental homes. Many single-family investors have determined that high-earning renters are willing to pay up to be the first occupants of a rental, which has sparked a boom in built-to-rent homes.

In the second quarter, American Homes 4 Rent added 136 custom-built homes while only purchasing eight existing houses, the first period in which the company built more than it bought. The Agoura Hills, Calif. company estimates that it will spend as much as $900 million this year and next adding properties to its stable, mostly building them with high earners in mind.

Executives say they’ll be building around Denver, where its $2,195 average rent is the highest in its portfolio by more than $300 a month, as well as in other booming Western cities like Seattle, Salt Lake City and San Antonio.

Just off San Antonio’s main freeway and across the street from one of its top high schools, the newly built Pradera community features tidy houses big enough for a family, typical of many subdivisions. But they are available only to rent.

For Lakisha Caldwell, the community offers suburban living that is mortgage-free and maintenance-light. “We don’t have to cut our own grass. We don’t have to worry about changing the lightbulb,” she said.

Pradera, where the typical tenant earns above $100,000 a year, will eventually include 250 rental homes. It is one of several single-family-rental communities developed by AHV Communities LLC and Bristol Group.

Mark Wolf, CEO of Irvine, Calif.-based AHV, said he looks for plots of land near good schools, employment centers and transportation corridors where well-off families might be able to afford to rent but not yet buy.

“Most people don’t have $5,000 or $10,000 to put down on a house,” he said.

Ms. Caldwell, who is 32 years old and works for a medical-device company, and her husband have been renting since moving to San Antonio eight years ago. They have a 10-year old son, two rescue dogs and two foster children.

“Some people make me feel bad about renting. They say, ‘Oh my goodness, you spend all this money on renting,’” she said. She has no desire to become a homeowner at the moment. “I don’t want to do what the Joneses are doing.”

Updated: 12-26-2019

As Rents Rise, Cities Strengthen Tenants’ Ability to Fight Eviction

A half-dozen cities across the U.S. promise the right to an attorney, a costly response to increasing homelessness.

Half-a-dozen cities from San Francisco to Cleveland are promising tenants the right to an attorney in eviction cases, a costly and logistically daunting initiative that advocates say is a necessary response to rising housing costs and homelessness.

If successful, proponents say these programs could provide a bulwark against gentrification and homelessness, and end up saving cities money by reducing the number of families who end up on the streets and in shelters.

Implementing such a sweeping new right poses challenges. It requires staffing legal aid offices with dozens of new attorneys, finding space in courtrooms for lawyers to meet with their clients, and slowing the rapid-fire pace of housing court to allow lawyers to file motions in defense of their clients.

The Supreme Court granted defendants a right to an attorney in criminal cases in state court in 1963, but efforts to guarantee defendants the right to counsel in civil cases have been much more patchwork.

Most of the cities involved, including Cleveland, Philadelphia, Newark, N.J., and Santa Monica, Calif., passed legislation in the past year, so it is early to judge how they have fared.

New York was the first city to guarantee tenants the right to counsel, rolling out the program by zip code starting about two years ago. Early results suggest both that the program is working in driving down evictions and also that it has been tough to implement.

From 2017 to 2018, evictions declined five times faster in zip codes where tenants have a right to counsel, compared to similar ones where they don’t, according to an analysis by the nonprofit Community Service Society.

The infusion of lawyers into a system, where historically most landlords were represented, compared to about 1% of tenants, has strained the courts, not only in their ability to process cases but even to physically fit people in the courtrooms.

In housing court in Brooklyn on a typical Thursday, lawyers signed stipulations on recycling bins and searched for quiet crannies to discuss confidential client information. Maura McHugh Mills, a deputy director of the housing unit at Brooklyn Legal Services, said she used to see a couple of other attorneys at the courthouse on a typical day, and now she sees closer to 45.

Ishon Mathlin, a 38-year-old construction worker, used the service after his son was killed in June. Grief and an on-the-job injury led Mr. Mathlin to fall behind on his $950-a-month rent. He now owes $600, he said.

Attorneys at Brooklyn Legal Services said they can help buy Mr. Mathlin time to catch up on the remaining rent and push for the landlord to make repairs, including patching a hole in his bathroom ceiling and replacing a missing door knob that forces him to open his front door by sticking his hand through a hole.

Mr. Mathlin said he doesn’t want to lose the apartment for the sake of his 7-month-old daughter. “I’m not going to end up on the street. I have nowhere to go,” he said.

Landlords have said that the significant funds needed to provide representation to lower-income residents could be better spent offering temporary housing subsidies to keep people in their homes.

“While I understand the attractiveness of that approach, it does nothing to get to the core issue of the vast majority of evictions, which is people who are unable to pay their rent,” said Gregory Brown, senior vice president of government affairs at the National Apartment Association.

More states and cities have started considering providing guaranteed assistance in eviction cases in the past several years, said John Pollock, coordinator of the National Coalition for a Civil Right to Counsel. This has been driven in part by rising housing costs. Rents have shot up 35% in major U.S. metropolitan areas since 2012, according to Reis Inc., a housing data provider.

“The housing crisis is what has precipitated it into people’s consciousness,” said Martha Bergmark, executive director of Voices for Civil Justice, a nonprofit advocacy organization for civil legal aid.

Most cities have limited the right to counsel to tenants making around minimum wage or less, though San Francisco has no income limits.

The cities that have so far guaranteed tenants a right to counsel are largely places that already have strong tenant protections and relatively low levels of evictions. One exception is Cleveland, where about 5% of tenants were evicted in 2016, according to the Eviction Lab at Princeton University.

Tenants in Cleveland lack protections found in cities like New York, according to Hazel Remesch, a supervising attorney at the Legal Aid Society of Cleveland.

Without an attorney, many tenants agree to simply leave immediately, but Ms. Remesch said lawyers are often able to negotiate for additional time to pay rent or find a new place to live.

“We think that makes the right to having an attorney that much more important, because whatever rights they do have, we need to make sure they’re being enforced,” Ms. Remesch said.

Affordable Housing Crisis Spreads,Affordable Housing Crisis Spreads,Affordable Housing Crisis Spreads,Affordable Housing Crisis Spreads,Affordable Housing Crisis Spreads,Affordable Housing Crisis Spreads,Affordable Housing Crisis Spreads,Affordable Housing Crisis Spreads,Affordable Housing Crisis Spreads,Affordable Housing Crisis Spreads,

Related Articles:

Home Prices Continue To Lose Momentum (#GotBitcoin?)

Freddie Mac Joins Rental-Home Boom (#GotBitcoin?)

Retreat of Smaller Lenders Adds to Pressure on Housing (#GotBitcoin?)

OK, Computer: How Much Is My House Worth? (#GotBitcoin?)

Borrowers Are Tapping Their Homes for Cash, Even As Rates Rise (#GotBitcoin?)

‘I Can Be the Bank’: Individual Investors Buy Busted Mortgages (#GotBitcoin?)

Why The Home May Be The Assisted-Living Facility of The Future (#GotBitcoin?)

Our Facebook Page

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.