If You Didn’t Get The Memo IMF Says Global Recession Is Underway, Worse Than 2009 (#GotBitcoin)

International Monetary Fund Chairman Kristalina Georgieva said Friday a global recession is underway and predicted it will be worse than the 2009 financial crisis, especially in developing nations. If You Didn’t Get The Memo IMF Says Global Recession Is Underway, Worse Than 2009 (#GotBitcoin)

“We are being asked by our members to do more, do it better, and do it faster than ever before – and to do it in collaboration with the World Bank and our other partners,” she said.

Updated: 3-30-2020

US Cash In Circulation Sees Biggest Increase Since The Y2K Bug Panic, Fed Data Indicates

U.S. currency in circulation has experienced its largest percentage increase in over 20 years, according to data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

From March 11 to March 18, dollar banknotes in circulation shot up from around 1.809 trillion to 1.843 trillion, an increase of almost 2 percent, the data shows. The increase was noted Sunday by economist John Paul Koning.

The data is the first strong signal, beyond scattered anecdotes, that U.S. citizens are now withdrawing more cash than usual from banks and ATMs amid concerns over the effects of the coronavirus pandemic.

The surge is the biggest since late 1999, when fear of a global digital systems crash caused by a rumored glitch in numerical dates – the so-called “Y2K bug” – sparked a frenzy of withdrawals and panic buying.

Based on the weekly change, the week ending Dec. 22, 1999, saw a 3.78 percent rise, while the week ending March 18, 2020, saw an increase of 1.92 percent.

Currency in circulation includes paper currency and coin held both by the public and in the vaults of depository institutions.

The increase comes as the global outbreak of the deadly coronavirus (COVID-19) continues to worsen in many nations, and with the health authorities advising social distancing measures and minimal contact with surfaces that might be contaminated with the virus.

The pandemic has brought new attention to the idea that physical money represents the “dirtiest” form of currency exchange between two parties, driving the narrative further for digital value transfer, blockchain-based or otherwise.

Updated: 4-1-2020

Fed’s Quantitative Easing Strategy Holds Long-Term Benefits For Crypto

These are perilous times, and it hasn’t escaped anyone’s notice that the United States Federal Reserve is doing its part to alleviate the suffering — which began with the coronavirus pandemic and has spread to the global economy. It’s printing more money.

“There is an infinite amount of cash at the Federal Reserve,” Neel Kashkari, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, told Scott Pelley of CBS on March 22, adding: “We will do whatever we need to do to make sure there is enough cash in the financial system.”

The U.S. Federal Reserve itself reinforced that message on March 23, announcing that it would “continue to purchase Treasury securities and agency mortgage-backed securities in the amounts needed to support smooth market functioning.”

The Death Of Capitalism?

Reactions to these affirmations of quantitative easing, or QE, have been swift from sectors of the crypto community: “With these words, the last vestige of #capitalism died in the US,” wrote Caitlin Long, who established the first crypto-native bank in the United States. “[The] Fed’s monetization U.S. debt is now unlimited.”

Mati Greenspan, the CEO and co-founder of Quantum Economics told Cointelegraph: “The Fed said it is willing to buy the entire market” if necessary to stabilize markets.

Meanwhile, on the fiscal side, Congress’s $2 trillion stimulus package includes handouts like “helicopter money” — i.e., a $1,200 payment to every tax-paying adult who has an annual income below $75,000. “Inflation is pretty much a foregone conclusion at this point,” he stated elsewhere.

Garrick Hileman, head of research at Blockchain.com, told Cointelegraph: “The response by central banks to COVID-19 is truly unprecedented, with Fed and Bank of England officials using terms like ‘infinite,’ ‘unlimited’ and ‘radical.’” They’ve been using such extraordinary language in the hope they’ll prevent equity and credit markets from seizing up. “Only time will tell if they have gone too far.”

The U.S. Dollar Is Dominant

Is inflation really imminent, though? Not if one recognizes that the global demand for U.S. dollars continues to exceed supply. As Civic CEO Vinny Lingham told Cointelegraph: “The reality is: Everyone needs to reprice assets, and they need to do it in U.S. dollars.”

Lingham grew up in South Africa. He saw what happened with hyperinflation in neighboring Zimbabwe where “the demand for stable currency exceeded everything else.” With people in the grip of the current pandemic, entire business sectors have been shutting down all over the world. People have been selling assets whether it’s equities, collectible classic cars or Bitcoin (BTC). Lingham added:

“If I’m living in South Africa, I may have kept money in the form of a bar of gold that is priced in Rands. Now I’m selling it for local Rands and buying U.S. dollars with those Rands. As the Rand devalues, the dollar gets stronger.”

Under such conditions, “if the Federal Reserve prints another $2 trillion USD, it’s okay,” said Lingham. Greenspan agrees that the U.S. dollar has been the world’s most in-demand financial asset in recent weeks, and theoretically, the Fed could print trillions more than it is currently proposing — and there may not be any hyperinflation.

The problem is that no one knows what the “stop point” is — i.e., how much is too much. “We won’t know [hyperinflation is] happening until it’s too late.”

BTC As A Store Of Value?

What does all of this mean for cryptocurrencies? Many in the crypto world assume that Bitcoin, with its fixed maximum supply — 21 million BTC — is bound to come out ahead if the Fed and other central banks print too much money. “Though that assumption has not been tested in real-time except in Venezuela,” said Greenspan.

If you had bought BTC at its low point in Venezuelan bolivars and had sold BTC at its height, also for bolivars, you would have come out way ahead. It’s not clear that this case can be generalized, though.

During the current crisis, BTC and other cryptocurrencies have plunged dramatically, just like equities — which has somewhat damaged Bitcoin’s claim of being a store of value.

The current economic environment is not favorable for any asset class, Lingham observed. Bitcoin i3s now positively correlated with other asset classes.

Greenspan said the correlation between BTC and the stock market has recently reached a high point of 0.6 — with 1.0 representing perfect positive correlation. If this were not the case, BTC would currently be priced somewhere between $12,000 and $15,000, Lingham suggested.

Ariel Zetlin-Jones, associate professor of economics at Carnegie Mellon University’s Tepper School of Business, told Cointelegraph that he understands this moment is critical for the future of cryptocurrencies:

“U.S. equity markets have suddenly become as volatile as Bitcoin markets, and the U.S. government is undertaking a large scale intervention that involves a massive expansion of the money supply which in the absence of other major shocks (the economic shutdown due to the pandemic), would normally induce a large increase in the inflation rate.”

However, Zetlin-Jones does not see these developments causing Bitcoin to emerge as a leading store of value because in the long run: “Bitcoin is one of the riskiest stores of value in the world, with Bitcoin price volatility more than five times that of both gold or even U.S. equity prices.” Kevin Dowd, a professor of finance and economics at Durham University in the United Kingdom, told Cointelegraph:

“BTC does offer an alternative store of value, and there is no question about that. The issue is: How good is it? It all depends upon when you buy and when you sell, and so there remains a huge element of luck.”

According to Hileman, the University of Cambridge’s first “cryptocurrency academic,” the prices of gold and Bitcoin should both rise:

“Even before COVID-19, we felt the unprecedented level of public and private debts made Bitcoin, and hard assets in general, attractive. Historically, recessions and large fiscal and monetary expansions have driven up the price of hard assets like gold. […] We do not see a reason why this time should be any different.”

The Future Of Crypto?

It is still too early to gauge the impact of QE on crypto, said Greenspan. “The initial shock of the global economy grinding to a halt” is still too fresh. “The long-term trend is yet to emerge.”

Moreover, BTC is just a small part of the story, though it has held its value well compared with other asset classes, Greenspan told Cointelegraph.

People have been struggling, and many individuals are selling everything they can, said Lingham. “Until there is excess capital, Bitcoin is in the same basket as other assets.

There will be no mad rush to get into cryptocurrency unless the U.S. dollar falters” — and then, only maybe.

“I would be surprised if BTC bit the dust due to the current crisis, but you cannot rule anything out,” said Dowd, who has maintained in the past that Bitcoin’s price must go to zero in the long term — principally because its mining model, a natural monopoly, is unsustainable.

In the short term, meanwhile: “The injection of money tends to float all markets, and that includes crypto,” said Greenspan. “Stocks will be first, but [the fiscal stimulus] is also likely to push up the price of BTC.”

A More Decentralized Global Economy?

The current crisis might eventually impel structural changes in the world economy, however, and these could change the crypto and blockchain space — for the better. Zetlin-Jones told Cointelegraph that once the recovery begins, a new way has to be found:

“We will need a more robust economy — one where supply chains are less dependent on a single producer, where workers are less dependent on the operations of a single firm, where individuals are less dependent on a single source of health care.”

These are effective movements toward a more decentralized world economy, in which blockchain technology seems uniquely poised to play a key role, Zetlin-Jones said.

“They might speed up the demand for blockchain solutions and, therefore, [improve] the long-run viability of blockchains and their associated cryptocurrencies.”

Updated: 4-2-2020

SEC Chairman: Government Shouldn’t Ban Short Selling in Current Market

Short selling needed to facilitate ordinary market trading, Jay Clayton says.

Wall Street’s top regulator said he doesn’t believe the U.S. should try to prevent investors from betting against the stock market, as more countries look to short selling bans amid extreme volatility.

“We shouldn’t be banning short selling,” Securities and Exchange Commission Chairman Jay Clayton said Monday in an interview on CNBC. “You need to be able to be on the short side of the market in order to facilitate ordinary market trading.”

Short selling involves an investor borrowing a stock and quickly selling it for cash in hopes of buying the stock back at a lower price before returning it to the lender. It is one of the most common ways in which investors can bet on a stock falling in price.

At times of heightened volatility, critics often argue that the practice exacerbates downward pressure on equity prices. Market regulators sometimes heed their warnings.

During the 2008 financial crisis, the SEC temporarily banned most short sales in shares of financial stocks.

As markets reeled from the coronavirus pandemic in recent weeks, authorities in countries including the U.K., Spain, Italy and South Korea imposed temporary curbs on short selling in some shares.

Some market participants, particularly hedge funds, now fear that Germany will follow suit, potentially leading to a European Union-wide prohibition that could have spillover effects in U.S. markets.

Economists say short sellers help keep markets efficient by unearthing overvalued stocks, and former regulators involved with the U.S. ban in 2008 have come to regard it as a mistake.

James Overdahl, the SEC’s chief economist from 2007 to 2010, said a review by his office found that the short-sale ban caused a temporary bump in the prices of the affected companies.

But the spread between the buying price and the selling price of the stocks widened, volatility increased, and traders looking to hedge their positions migrated into less-transparent instruments in derivatives markets.

“What we found was, on net, it was harmful,” Mr. Overdahl said in a webinar last week. “There were many unintended consequences.”

Updated: 4-8-2020

Ocean Carriers Idle Container Ships In Droves on Falling Trade Demand

More than 10% of the global boxship fleet are anchored as Western markets lock down against the coronavirus pandemic.

Container ship operators have idled a record 13% of their capacity over the past month as carriers at the foundation of global supply chains buckle down while restrictions under the coronavirus pandemic batter trade demand.

Maritime data provider Alphaliner said in a report Wednesday that shipping lines have withdrawn vessels with capacity totaling about 3 million containers in efforts to conserve cash and maintain freight rates.

Alphaliner, based in Paris, said more than 250 scheduled sailings will be canceled in the second quarter alone, with up to a third of capacity taken out in some trade routes.

The biggest cutbacks so far have hit the world’s main trade lanes, the Asia-Europe and trans-Pacific routes.

“No market segment will be spared, with capacity cuts announced across almost all key routes,” the report said. “While the larger ships will be cascaded to replace smaller units on the remaining strings, carriers will be forced to idle a large part of their operated tonnage.”

The cutbacks are hitting the network of businesses, from ship-financing to vessel-leasing companies, behind maritime supply chains.

“We had two ships given back to us three months early in the past week alone,” said a Greek owner, who charters his fleet of 19 vessels to some of the world’s biggest liners. “Instead of boosting capacity for the peak summer season, we are discussing where to lay up our ships. It’s a crazy time.”

Ship brokers say giant ships that move more than 20,000 containers each now are less than half full.

“It will change when American and European consumers get out and start spending again, but this can be weeks or months away,” said George Lazaridis, head of research at Allied Shipbroking in Athens.

Sailing cancellations grew from 45 to 212 over the past week, according to Copenhagen-based consulting firm Sea-Intelligence.

The “blanked” sailings are stretching into June, indicating operators expect the traditional peak shipping season, when retailers restock goods ahead of an expected buildup in consumer spending in the fall, will be muted this year by the lockdowns extending across economies world-wide.

France’s CMA CGM SA, the world’s fourth-largest container line by capacity, said this week it is idling 15 ships because retailers are pulling back orders over falling demand from European and American consumers.

The decision to idle, or “lay up,” ships is a difficult option for owners, as the vessels continue to generate costs without offsetting income.

There are two ways to idle ships. In a “warm layup” vessels are anchored and staffed, ready to go relatively quickly when demand resumes.

This means saving on operating costs such as fuel but continuing to pay crew salaries and insurance fees and make charter payments.

In a “cold layup” a skeleton crew is kept on board for general maintenance but most of the ship’s systems are shut down.

Returning the ship to service can cost millions of dollars and requires extensive testing to certify that the ship is safe to sail.

Many owners choose to lay up bigger vessels in Southeast Asia, mostly in Malaysian and Indonesian waters.

“It’s cheaper to book sea space compared to other parts of the world and ships can be deployed easily on the Asia-to-Europe trade route when things get back to normal,” Mr. Lazaridis said. “But laying up ships for an extended period is a mortal danger for any operator.”

Updated: 4-14-2020

‘The Great Lockdown’: IMF Confirms Global Recession

The coronavirus economic crisis officially has a name: the Great Lockdown.

“The Great Lockdown is the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression, and far worse than the Global Financial Crisis [of 2008],” International Monetary Fund (IMF) Chief Economist Gita Gopinath said on Tuesday.

She projected the global economy will contract by 3 percent in 2020, due to $9 trillion in losses. The United States is expected to decline to roughly -6 percent growth, as are other nations in the advanced economy group. Gopinath said this year’s losses will “dwarf” the global financial crisis 12 years ago.

“For the first time since the Great Depression both advanced economies and emerging market and developing economies are in recession,” Gopinath said.

Furthermore, the IMF projected that vulnerable oil-exporting countries, like Iraq, will “be forced to make aggregate cuts,” according to IMF Research Director Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti.

For example, the IMF predicts the Iraqi economy will contract to -4.7 percent growth this year, down roughly 8 percentage points from 2019’s growth rate of 3.9 percent, while the Iranian economy will contract to -6 percent growth this year.

Overall, the IMF is encouraging debtors to forgive lenders and for leaders to cooperate on joint efforts to prevent de-globalization. The IMF said more than 90 of its 189 member states have requested financial support.

“We’re projecting for economic activity to still be below pre-virus levels in 2021,” said Gopinath. “This is a deep recession that involves insolvency issues and unemployment rates going up dramatically.”

Gopinath said nations with access to private-sector digital payment systems should use them to distribute aid and stimulus packages.

Although she didn’t specify technologies by name, the U.S. Treasury is already working with fintech giants including PayPal and Square while Kenya relies on the mobile money product M-Pesa to decrease in-person transactions.

Updated: 4-14-2020

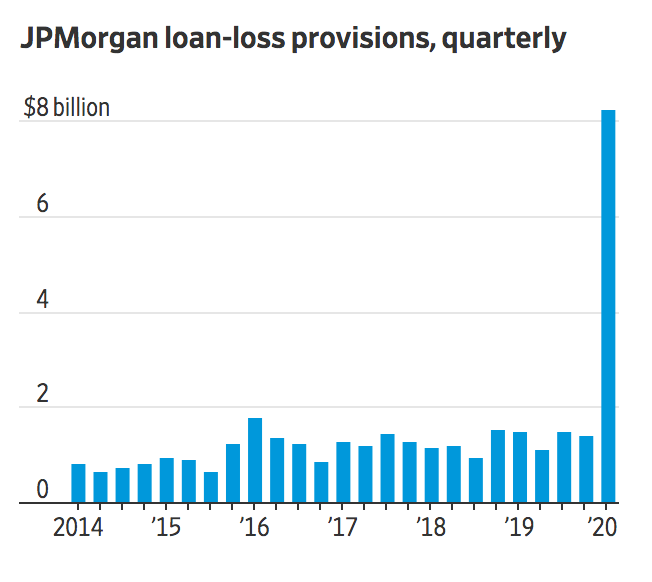

JPMorgan Prepares For Wave Of Defaults Linked To Coronavirus Shutdown

First-quarter results in New York bank’s consumer unit fall sharply, while trading revenue rises.

JPMorgan Chase & Co., bracing for a severe recession, set aside another $6.8 billion to cover potential losses on loans to consumers and companies struggling to stay afloat during the coronavirus shutdown.

The nation’s biggest bank said Tuesday that profit fell by nearly 70% in the first quarter, when the coronavirus pandemic slammed the brakes on the U.S. economy. It warned that it may set aside even more of its profits to cover loan losses if its second-quarter forecasts—including an unemployment rate of 20%—prove to be accurate.

In the past month, JPMorgan has temporarily closed hundreds of branches. Its biggest corporate clients have drawn down billions of dollars on their credit lines and sought billions more in new debt. Many of its customers—businesses and consumers alike—are struggling to pay their debts. For much of this turbulent period, longtime Chief Executive James Dimon was out of commission, recovering from emergency heart surgery.

“This is such a dramatic change of events,” said Mr. Dimon, who returned to work a few weeks ago. “There are no models that have ever done this.”

JPMorgan’s quarterly profit fell to $2.87 billion, or 78 cents per share, compared with $9.18 billion, or $2.65 a share, a year earlier. Analysts had forecast $2.16 per share, according to FactSet.

Revenue declined 3% to $28.25 billion, compared with $29.12 billion the year before. That fell short of the $29.55 billion analysts had predicted.

The sharp drop in profit is a reversal from the past two years, but it is likely only a hint of the damage yet to come.

The bank’s total provision for soured loans rose $6.8 billion from the previous quarter to $8.29 billion. That is already more than the bank has had in reserves since 2010.

Chief Financial Officer Jennifer Piepszak warned it may not be enough. She said the provision was based, in part, on the assumption that U.S. gross domestic product would fall 25% and that unemployment would rise to above 10% in the second quarter. Since then, Ms. Piepszak said, JPMorgan economists have amended their forecast to a 40% decline in GDP and a 20% unemployment rate.

JPMorgan prepared for the steepest losses in its consumer business. Ms. Piepszak said the government’s stimulus efforts will determine the ultimate size of its credit-card losses.

Profit in JPMorgan’s consumer unit plunged 95% to $191 million, largely due to the loan-loss provisions, particularly in credit cards. Revenue in the consumer unit dropped 2%. Card usage slowed in the quarter, as did home lending and mortgage originations.

Stock-market volatility increased demand for trading and big corporate clients clamored for cash. Trading revenue jumped 32% and lending profits rose. The bank said it was its best quarter ever for issuing investment-grade credit. Still, revenue in the corporate and investment bank slipped 1% to $9.95 billion and profit fell 39% to $2 billion, hit by a markdown on the value of loans its bankers hadn’t yet sold.

JPMorgan said corporate clients drew down some $50 billion on their credit lines in the first quarter, contributing to a 6% jump in borrowing that brought the banks’ total loan book above $1 trillion for the first time. Deposits grew by 23% to $1.8 trillion, largely due to business borrowers socking away their borrowed funds.

The commercial bank’s profit fell 86% to $147 million on credit-loss reserves of $1 billion, largely stemming from the worsening condition of its energy-industry borrowers. The asset and wealth management division’s profit was flat at $664 million.

JPMorgan shares started the year by hitting fresh highs, but have slumped over the past month along with other big banks. They fell 2.7% to $95.50 on Tuesday, trailing the broader market.

Updated: 4-23-2020

Global Economy Hit by Record Collapse of Business Activity

Surveys suggest governments have effectively closed parts of the economy where face-to-face interaction is unavoidable.

Business activity in the U.S., Europe and Japan collapsed in April as governments tightened restrictions on movement and social interaction aimed at limiting the spread of the coronavirus, according to surveys of purchasing managers.

The surveys, out Thursday, suggest governments have effectively closed parts of the economy where face-to-face interaction is unavoidable—such as restaurants and barbers—and activity has tumbled in parts of the economy less directly affected.

The drop in services-sector activity is unprecedented in the history of the surveys, even in the wake of the global financial crisis. Manufacturing activity is also contracting though not quite as severely.

According to data firm IHS Markit, the composite Purchasing Managers Index for the U.S.—a measure of activity in the private sector—fell to 27.4 in April from 40.9 in March. A reading below 50.0 indicates that activity has fallen, and the lower the figure, the larger the fall.

The April reading was the lowest in data dating back to October 2009.

“The scale of the fall in the PMI adds to signs that the second quarter will see an historically dramatic contraction of the economy,” said Chris Williamson, chief business economist at IHS Markit.

In the eurozone, the index dropped to 13.5 in April from 29.7 in March, a record low for data going back to July 1998. The lowest level reached in the wake of the global financial crisis was 36.2 in February 2009. In the U.K., the composite PMI fell to 12.9, a record low, from 36.0 in March. Japan’s composite measure also hit a record low of 27.8.

The declines were larger than expected, suggesting economic contractions in the second quarter of 2020 may be larger than economists had expected.

“While we knew lockdowns were shutting down large parts of the economy and expected the PMIs to decline from March, the scale of the falls in today’s release was staggering,” said Rosie Colthorpe, an economist at Oxford Economics.

The lockdowns now weighing on economies in the U.S. and Europe were pioneered in east Asia, where the coronavirus outbreak began.

Figures released by South Korea Thursday suggested the economic cost of its restrictions was relatively modest in the first three months of the year, with gross domestic product falling by 1.4% compared with the final three months of 2019. In China, the decline in GDP over the same period was 9.8%.

J.P. Morgan sees GDP in the U.S. falling at an annualized rate of 40% in the three months through June, the eurozone tumbling 45%, with the U.K. economy expected to contract by 59.3% and Japan by 35%. Some forecasts are for a relatively quick rebound, though the outlook depends on how quickly and thoroughly the coronavirus can be contained.

“You have to answer the medical question first, and I just don’t know,” said Todd Bluedorn, chairman and chief executive of cooling and heating manufacturer Lennox International, this week on an earnings call. “And so look, if we have therapeutics in two months, I’d say it’s, Katy, bar the door. If it’s three years and we’re still searching for a vaccine, then the barn’s burned down.”

Some economists believe that the April readings are as low as the PMIs will go, partly because some countries—including Germany—and some U.S. states have begun to ease their restrictions, and others are expected to follow in May. Also, the indexes can only fall so far—French service providers experienced the largest decline in activity during a single month for any sector in any country on record.

Health experts have cautioned that moving too quickly to reopen economies could lead to another wave of the disease.

“It’s hard to tell whether this is the bottom or not. It really depends on containment and how fast the economy can be reopened,” said Rubeela Farooqi, chief U.S. economist at High Frequency Economics.

Social distancing in some form is likely to continue for many months to come, whether by individual choice or government edict. That means activity is unlikely to rebound as quickly as it declined.

The surveys suggest it is almost certain the global economy has entered a recession, with figures for the first three months of the year pointing to widespread drops in economic output.

The U.S. and the eurozone will release estimates for the first quarter next week that are expected to show larger falls, but they will likely be modest compared with the contractions predicted for the April-June period.

Updated: 4-29-2020

Ship Orders Crash as Coronavirus Takes a Toll on Seaborne Trade

A new report says shipbuilding investment in the first quarter was down 71% to the lowest in more than a decade.

The economic fallout from coronavirus restrictions helped cut investment in shipbuilding to its lowest level in 11 years in the first quarter, with work at Asian shipyards nearly halted and owners holding back on orders as global demand for goods nosedived.

“Contracting activity was extremely limited in the first quarter of 2020, with the economic impact of the Covid-19 outbreak negatively affecting investor sentiment,” shipbroker Clarkson PLC said Monday in its monthly World Shipyard Monitor report.

Clarkson said 100 vessels of all types were ordered in the first three months of 2020 at $5.5 billion, a 71% decline from last year’s first quarter and the lowest total since the second quarter of 2009. Chinese yards got 55 orders in the quarter and South Korean yards got 13 orders, representing falls of 50% and 81%, respectively.

The firm expects orders to keep sliding as a global downturn in trade deepens, and that the number of overall orders will decline by 26% this year. “The continued escalation of the coronavirus outbreak is likely to have a severe impact on newbuild order potential in 2020,” Clarkson said.

Clarkson said seaborne trade, which stands at around 12 billion metric tons, will contract by 600 million metric tons this year, the biggest fall in more than 35 years. The firm forecasts that overall trade of goods moved on ships will shrink 5.1% in 2020 from last year, compared with a 4.1% annual decline during the 2008-09 financial crisis.

The falling orders affect every type of ship, from container vessels that move the world’s manufactured goods to high-margin natural-gas carriers where South Korean and Chinese yards had pinned their hopes for growth this year.

Orders for dry-bulk carriers and tankers also are drying up even though China is resuming commodity imports and energy traders are booking tankers to store oil on the back of the crude-price collapse.

The trade lapse will directly hit the Korean and Chinese yards that control around half of the global shipbuilding capacity, according to marine data provider VesselsValue.

South Korea’s Hyundai Heavy Industries Co. and Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering Co. are merging, and so are China Shipbuilding Industry Corp. and China State Shipbuilding Corp., combinations undertaken to help rationalize operations and cut costs amid declining orders over the past three years.

The yards were making more space to build liquefied natural gas carriers, which cost around $180 million apiece, about three times more than other types of ships, and generate profit margins that are at least twice as high as other ships.

“Then the virus hit and the bottom fell off,” said a senior executive at the China Association of the National Shipbuilding Industry, China’s state-run yard trade body. “It’s bad times, so we have to lure in orders. Depending on the customer and the type of ships, Chinese yards will be offering up to a 20% discount on new orders.”

The LNG market was surging before the coronavirus outbreak, mainly on demand from China and India, which are turning to gas rather than coal for power generation and heating.

Clarkson said the global order book for LNG carriers in the first quarter stood at 2,915 vessels, the lowest tally since 2004, when the natural-gas market was a fraction of what it is now.

The broker said travel restrictions also are delaying orders, as carrier executives are unable to meet with shipyard engineers and planners for the detailed work that goes into planning vessel specifications.

“We got a bulker and a small boxship on order which are already a month late and we can’t send our people to China to check on the progress of work,” said an Indonesian owner, who requested anonymity. “How can you buy a ship when you can’t be at the yard to make sure it’s being put together properly?”

Clarkson said Chinese yards that had suspended work in February under Beijing’s coronavirus restrictions had mostly resumed production by mid-March. But deliveries may be held up because critical parts like navigation systems provided by European suppliers have been delayed, and some shipowners are seeking to push back payments.

Updated: 5-6-2020

US Private Payrolls Drop By 20.2 Million In April, The Worst Job Loss In The History Of ADP Report

Private payrolls hemorrhaged more than 20 million jobs in April as companies sliced workers amid a coronavirus-induced shutdown that took most of the U.S. economy offline, according to a report Wednesday from ADP.

In all, the decline totaled 20,236,000 — easily the worst loss in the survey’s history going back to 2002 but not as bad as the 22 million that economists surveyed by Dow Jones had been expecting. The previous record was 834,665 in February 2009 amid the financial crisis and accompanying Great Recession.

“Job losses of this scale are unprecedented,” said Ahu Yildirmaz, co-head of the ADP Research Institute, which compiles the report in conjunction with Moody’s Analytics. “The total number of job losses for the month of April alone was more than double the total jobs lost during the Great Recession.”

The report likely still understates the actual damage done during the implementation of social distancing measures. ADP used the week of April 12 as its sample period, similar to the method the Labor Department uses for its official nonfarm payrolls count. The subsequent weeks in the month saw some 8.3 million more Americans file for unemployment benefits and economists expect another 3 million last week.

In all, more than 30 million have filed claims over the past six weeks.

The April total comes after a drop of 149,000 in March, revised lower from the initially reported 26,594.

The only bright spot from the report may be a signal that the worst is behind as more states curb or end restrictions put into place from coronavirus containment efforts.

“The worst of it is at hand,” said Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics. “We should see a turn here relatively soon in the job statistics. At least for the next few months, I would anticipate some big, positive numbers.”

Service Industries Hit Hardest

As expected, job losses were most profound in the services and hospitality sector, as bars and restaurants had to close during the pandemic with virtually no eat-in dining allowed. In all, the sector saw 8.6 million furloughs even as some establishments tried to make up for lost business with curbside and delivery services.

Trade, transportation and utilities was the next hardest-hit sector, losing 3.44 million, while construction dropped 2.48 million. Other big losses came in manufacturing (1.67 million), the other services category (1.3 million), and professional and business services (1.17 million). Health care and social assistance plunged by 999,000, information services fell by 309,000 and financial services had 216,000 layoffs.

The only areas reporting gains were education, with 28,000, and management of companies and enterprises, at 6,000.

Broadly speaking, service-related industries fell by just over 16 million, while goods producers declined by 4.3 million.

Big businesses, with more than 500 employees, were hit hardest, losing just shy of 9 million jobs. Companies with fewer than 50 workers were down by just over 6 million and medium-sized firms saw 5.27 million layoffs.

The steep job losses come amid trillions of dollars in rescue programs from Congress and the Federal Reserve that, in part, sought to encourage companies to continue paying workers during the shutdown. Fed Vice Chairman Richard Clarida told CNBC on Tuesday that while he sees a rebound coming in the second half of the year, he envisions policymakers having to do more to keep the economy afloat.

St. Louis Fed President James Bullard told CNBC on Wednesday that the sharp jump in jobless is not surprising and he expects the situation to turn around considerably before the end of the year.

“It’s not surprising. It’s a pandemic, it’s a shutdown situation,” Bullard said on “Squawk Box.” “We need to get the pandemic under control. Then of course you have to help these workers.”

The ADP report precedes Friday’s release from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which is expected to show that nonfarm payrolls fell by 21.5 million in April, from March’s 701,000 drop, with the unemployment rate climbing to 16% from 4.4%.

Updated: 5-13-2020

Maersk Expects Container Shipping Volumes To Fall Up To 25%

The boxship operator beat expectations and posted a quarterly profit built partly on cost cuts, higher freight rates.

A.P. Moeller-Maersk A/S expects container volumes to fall up to 25% this quarter and plans to cancel dozens of sailings as the Danish shipping giant copes with sliding demand in consumer and industrial markets from the coronavirus pandemic lockdowns.

Maersk, which moves 17% of all containers world-wide, posted better-than-expected first-quarter earnings on Wednesday as cost cuts, lower fuel outlays and higher freight rates helped offset the demand slump.

With the U.S. and European countries stepping carefully toward reopening their economies, Chief Executive Soren Skou said he expects no meaningful recovery until the end of the year, and added that container volumes are expected to fall 20% to 25% in the second quarter from a year ago.

“There is a massive impact on both Asia-to-Europe trades and across the Pacific with the U.S. and Europe into lockdown,” Mr. Skou said. ”Without a doubt it’s going to be the steepest ever drop in demand within a quarter.”

The company suspended its financial outlook in March, and Mr. Skou said business remains uncertain even if the lockdowns end and a coronavirus vaccine is developed and distributed in the coming months.

“It’s one thing to reopen and another whether the consumer will go out shopping,” he said, adding that with millions out of work, economic activity could be anemic for months.

Maersk and other container shipping lines have canceled hundreds of sailings on major trade lanes and idled ships to cut costs and maintain freight rates amid the declining demand.

Maersk said its average container freight rates were up 5.7% in the first quarter from a year ago. The carrier canceled more than 90 sailings in the first quarter and expects another 140 to be dropped in the second quarter.

“The aim is to provide capacity in line with demand. We save costs with the fewer sailings and capacity utilization on the ships that still sail is high,” said Mr. Skou.

Maersk scrapped most of its full-year guidance in March amid the Covid-19 impact on supply chains, but said Wednesday that it sees 2020 volume growth in its shipping unit in line or slightly lower than the overall market.

Industry research group Alphaliner has projected that global container trade will contract 7.3% this year from 2019 levels.

The company swung to a quarterly net profit of $197 million from a loss of $659 million in the same period last year, beating average expectations by analysts of $25 million in earnings, according to FactSet. Earnings last year were weighed down by a $552 million loss on discontinued operations.

Revenue rose 0.3% to $9.57 billion, while earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization of $1.52 billion beat Maersk’s own guidance of $1.4 billion.

Maersk Line, the company’s shipping unit and main earner, made a profit of $1.2 billion in the first quarter, up 25% from a year ago.

Shipping executives expect the world’s top 10 carriers to end the year deeply in the red. Industry analysts have said that could trigger some failures as carriers with strong cash holdings and access to credit markets outlast weaker operators.

France’s CMA CGM SA, the world’s fourth-largest container line, said Wednesday it had secured a €1.05 billion ($1.14 billion) bank loan backed by the French government to help it weather an expected 10% drop in its business.

It is the first time that a European government had guaranteed a loan of that scale to a private shipping company. Under the terms, the carrier must pay the loan back in a year but it get an extension of up to five years.

Maersk is in a strong financial position with $9.2 billion in cash reserves and access to revolving credit facilities, according to Mr. Skou. Along with other liners it is benefiting from substantially lower fuel prices.

Mr. Skou said he doesn’t expect the world to emerge from the pandemic-driven downturn with large changes in major trade patterns even though some political leaders have called for “reshoring” of manufacturing from Asia to domestic factories in Western countries.

Production of medical supplies now produced in China will be diversified, he said. “But masks and personal protection equipment don’t matter in terms of volumes in global trade and there is nothing to suggest that the manufacturing of electronics, toys, clothing, shoes, parts and others will not continue to be in Asia,” Mr. Skou said.

Updated: 5-18-2020

Uber Cuts 3,000 More Jobs, Shuts 45 Offices In Coronavirus Crunch

The ride-hailing giant also is exploring the sale of noncore businesses.

Uber Technologies Inc. is cutting several thousand additional jobs, closing more than three dozen offices and re-evaluating big bets in areas ranging from freight to self-driving technology as Chief Executive Dara Khosrowshahi attempts to steer the ride-hailing giant through the coronavirus pandemic.

Mr. Khosrowshahi announced the plans in an email to staff Monday, less than two weeks after the company said it would eliminate about 3,700 jobs and planned to save more than $1 billion in fixed costs.

Monday’s decision to close 45 offices and lay off some 3,000 additional people means Uber is shedding roughly a quarter of its workforce in under a month’s time. Drivers aren’t classified as employees, so they aren’t included.

Stay-at-home orders have ravaged Uber’s core ride-hailing business, which accounted for three-quarters of the company’s revenue before the pandemic struck. Uber’s rides business in April was down 80% from a year earlier.

“We’re seeing some signs of a recovery, but it comes off of a deep hole, with limited visibility as to its speed and shape,” Mr. Khosrowshahi said in his note to employees. The company’s food-delivery arm, Uber Eats, has been a bright spot during the crisis, but “the business today doesn’t come close to covering our expenses,” he wrote.

Uber is in talks to buy rival Grubhub Inc., according to people familiar with the matter, a deal that would help stem losses from the cost-intensive business of building out delivery operations and give Uber an edge in competing with industry leader DoorDash Inc. Mr. Khosrowshahi didn’t reference the potential deal in his memo.

The pandemic hit when Uber was pivoting from a strategy of growth at all costs. Mr. Khosrowshahi was trimming costs even before the outbreak in an effort to put Uber on a path to profitability by the end of the year. He recently extended that timeline to next year.

“I will not make any claims with absolute certainty regarding our future,” Mr. Khosrowshahi wrote in his note. “I will tell you, however, that we are making really, really hard choices now, so that we can say our goodbyes, have as much clarity as we can, move forward, and start to build again with confidence.”

As part of the latest changes, Uber will scale back on noncore businesses. Mr. Khosrowshahi said the company is winding down its product incubator and artificial-intelligence lab, and exploring “strategic alternatives” for Uber Works, which pairs prospective employers with gig workers.

The company is also re-evaluating cash-burning businesses such as freight and autonomous driving. Uber has spent hundreds of millions of dollars to advance self-driving research in recent years.

Employees in the U.S. will be the hardest hit by the cuts, according to a person familiar with the matter. Uber is closing one of its offices in downtown San Francisco, which had more than 500 employees. It is also considering moving its Asia headquarters from Singapore to a different market.

“We’re seeing some signs of a recovery, but it comes off of a deep hole, with limited visibility as to its speed and shape.”

— Dara Khosrowshahi, Uber CEO

Smaller rival Lyft Inc. said last month that it would cut about 17% of its workforce while also furloughing workers and slashing pay amid efforts to cut costs during the coronavirus pandemic.

Mr. Khosrowshahi said he wants to rally around core businesses—mobilizing people and goods—and build an organizational structure that avoids duplication.

He announced that Andrew Macdonald, Uber’s senior-vice president of rides, has been appointed head of a unified mobility team that will cover all aspects of Uber’s rides business, including its public-transportation partnerships. Pierre-Dimitri Gore-Coty, vice president of Uber Eats, was named head of a unified delivery team that will also include grocery deliveries.

While these measures should help rein in costs, Uber faces a fundamental question as governments begin to ease stay-at-home orders: Will people resume using its core rides services and, if so, how does the company assure drivers—and riders—that they are safe?

The company has allocated $50 million to buy supplies for drivers, including masks, disinfectant sprays and wipes. Starting Monday, the Uber app will ask drivers across much of the world to verify they are wearing face masks by taking selfies. Riders will also need to confirm they are wearing face coverings.

Meanwhile, regulatory hurdles loom for the ride-sharing giant. California sued Uber and Lyft earlier this month, alleging the companies’ misclassification of drivers as independent contractors deprives the drivers of rights such as paid sick leave and unemployment insurance—issues that became front-and-center during the pandemic. The state’s gig economy law that took effect Jan. 1 aimed to force the companies to classify drivers as employees.

Uber and Lyft have said their drivers are properly classified under the law. The ride-hailing companies have joined other startups that rely on gig workers and raised more than $110 million to back a ballot initiative for November, asking that voters exempt them from the law. The ballot initiative also would guarantee benefits such as health-care subsidies for drivers who work a certain number of hours a week.

Mr. Khosrowshahi didn’t mention the lawsuit in his memo.

He said he struggled to make the decisions that culminated in Monday’s announcement and even consulted other CEOs, hoping there was a way the company could “wait this damn virus out.”

“I wanted there to be a different answer,” Mr. Khosrowshahi said, “but there simply was no good news to hear.”

Updated: 5-22-2020

Dropping Growth Target, China Acknowledges Severity of Its Economic Challenges

In a humbling moment, Xi Jinping is forced to give up on a vaunted political goal.

Under leader Xi Jinping, China has established itself as an increasingly assertive global player, pushing back forcefully against challenges at home and abroad.

But even as Beijing tightens its grip on Hong Kong and steps up its rhetoric against the U.S., senior leaders bowed to the inevitable on Friday, acknowledging the scope of the challenges facing the economy—the bedrock of much of the country’s recent strength.

On Friday, Premier Li Keqiang abandoned the country’s annual gross domestic product target for the first time in more than a quarter-century, citing “factors that are difficult to predict”—most notably the coronavirus pandemic and uncertainties around trade.

Mr. Li and his fellow Chinese policy makers are portraying the decision as a liberating one that enables them to focus on ensuring stability and security.

There is an element of truth there. China’s economy is slowly plateauing after an extended run of world-beating growth, and leaders have in recent years de-emphasized explicit growth targets anyway, increasingly regarding them as burdensome.

In March, Mr. Li called on officials to prioritize employment over raw GDP growth, underscoring the senior leadership’s concerns about social instability. “As long as employment is stable this year, it’s not that big of a deal whether the economic growth rate is a bit higher or lower,” Mr. Li said.

“This year could be a turning point for Beijing to further downplay the GDP target,” said Liu Li-Gang, chief China economist at Citigroup. “We are likely to see this trend extend into the future.”

Even so, dropping the GDP target for the year, long the lodestar of Chinese economic policy, is a humbling moment, forcing Mr. Xi to give up on one of the Chinese leadership’s most vaunted political goals: to double the economy’s size from a decade earlier ahead of next year’s centennial of the Chinese Communist Party’s founding.

Officials have already begun to lower expectations. He Lifeng, the head of China’s main economic-planning body, told reporters Friday that even meager GDP growth this year of 1% would expand overall GDP by 1.9 times from a decade earlier—not quite double, but close enough.

“Beijing is taking a more realistic and humbler approach by omitting a growth target this year amid so many uncertainties,” said Betty Wang, an economist with ANZ Research.

Ultimately, the scrapping of the GDP target serves as a blunt reminder of the magnitude of the many risks that loom over China’s economy in the coming months.

While China claimed success in stamping out the initial outbreak of the coronavirus, which was first detected late last year in the central city of Wuhan, authorities have struggled to prevent continued outbreaks around the country and haven’t loosened tight restrictions on international travel.

Epidemiologists have warned about a potential reemergence of infections in the fall, which could force authorities inside and outside China to keep their economies on lockdown for longer than expected.

Then there is the other great uncertainty: a tense and quickly deteriorating relationship with the U.S., the world’s largest economy, as the two sides fight over trade, technology and the origins of the coronavirus.

In the past week alone, President Trump has moved to tighten restrictions on doing business with Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei Technologies Ltd. and threatened to tear up the phase-one trade deal with China. At the same time, he has offered vocal support for Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen, whose government, reviled in Beijing, began a second four-year term on Wednesday.

The danger for China is that the U.S. could take further steps to pinch China’s economy, particularly as emotions run high on Hong Kong, and Mr. Trump and his Democratic challenger, Joe Biden, vie to establish themselves as the toughest candidate on China.

“The uncertainty is too big, especially given the U.S. election later this year,” said Ding Shuang, an economist at Standard Chartered. “It’ll be awkward if they set a growth target and couldn’t reach it.”

Just hours before Mr. Li’s policy address in Beijing, U.S. senators from both parties began drafting legislation to sanction Chinese officials and entities involved in enforcing the new national-security laws in Hong Kong and punish any banks doing business with them—a move that could snarl China’s financial system.

With so many uncertainties, Chinese policy makers aren’t just struggling to forecast a growth target for the year. They are also holding back on stimulus, raising the fiscal deficit target to 3.6% or more of GDP—a new high—but falling short of the kind of forceful “all-in” stimulus that characterized their response to previous downturns.

“It’s a relatively modest package,” said Zhu Haibin, an economist at J.P. Morgan, who described China’s fiscal stimulus package as falling in the middle of the pack as far as global responses go. As a result, Mr. Zhu expects the Chinese economy to grow by 1.3% in 2020, the worst full-year performance since Mao Zedong’s death in 1976.

To be sure, if the situation deteriorates further, policy makers may be forced to ramp up stimulus, said Larry Hu, an economist at Macquarie Group. As it stands, he said, China’s other economic targets this year—to create more than nine million urban jobs and keep urban unemployment below about 6%—are ambitious enough, given the myriad uncertainties.

“Chinese authorities don’t have to defend the GDP growth target any more,” Mr. Hu said, “but they are still under pressure.”

Updated: 6-8-2020

Recession In U.S. Began In February, Official Arbiter Says

Monthly economic activity ‘reached a clear peak’ in February, marking the end of the 128-month expansion that began in June 2009.

The U.S. economy entered a recession in February, the group that dates business cycles said Monday, ending the longest American economic expansion on record.

Monthly economic activity “reached a clear peak” in February, marking the end of the 128-month expansion that began in June 2009, said the Business Cycle Dating Committee of the National Bureau of Economic Research. It was the longest expansion in records back to 1854.

Recessions are typically defined as declines in economic activity that last more than a few months, and the NBER often takes more than a year to declare a recession officially under way. It also takes into consideration the depth and duration of the downturn and whether activity has declined broadly across the economy.

The committee said the new coronavirus pandemic and the subsequent public-health response have led to a downturn with different dynamics than prior recessions.

“Nonetheless, it concluded that the unprecedented magnitude of the decline in employment and production, and its broad reach across the entire economy, warrants the designation of this episode as a recession, even if it turns out to be briefer than earlier contractions,” the group said.

Many economists had believed the U.S. was in recession since at least March, when governments began ordering businesses closed and workers sent home in an effort to slow the fast-spreading virus.

Employment and consumer spending has plunged as Americans curbed travel, shopping and eating out, and businesses laid off employees. Gross domestic product, the broadest measure of economic output, fell 5% in the second quarter.

Employers shed roughly 22 million jobs in March and April, and the jobless rate hit 14.7%, a post-World War II high. Consumer spending, the economy’s key driver, plunged 7.5% in March and 13.6% in April, setting back-to-back record declines in records tracing back to 1959.

Signs are emerging that the economy may have hit bottom in May. Employers added 2.5 million jobs last month, the most added in a single month on records dating from 1948, and the jobless rate fell to 13.3%.

Still, employment remained down by nearly 20 million jobs since February. By comparison, the U.S. shed about 9 million jobs between December 2007 and February 2010, a period that covered the recession caused by the financial crisis.

The NBER’s recession-dating committee looks at gauges of employment and production, as well as incomes minus government benefits, to determine when a recession has begun. Many other countries use a different measure: two or more quarters of declining real gross domestic product.

The committee doesn’t comment on how long the recession may last, though many economists project a swift rebound this summer followed by a long, slow return to pre-pandemic.

The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office said last week the U.S. economy could take the better part of a decade to fully recover from the pandemic and related shutdowns. Gross domestic product will likely be 5.6% smaller in the fourth quarter of 2020 than a year earlier, despite an expected pickup in economic activity in the coming months, and the unemployment rate could still be in double digits by the end of the year, the CBO said.

Updatd: 7-8-2020

United Warns It May Furlough 36,000 Staff

The airline’s involuntary cuts are likely to be set in August and go into effect from Oct. 1.

United Airlines Holdings Inc. UAL -2.90% said it could be forced to shed almost half its U.S. workforce, telling 36,000 employees on Wednesday that they could be furloughed from Oct. 1 because of the pandemic-driven slump in passenger demand.

Chicago-based United is the first major U.S. carrier to detail possible mass furloughs despite the billions of dollars in federal aid provided to airlines that covered payrolls through September.

A senior executive called the move “a last resort.” It follows the recent erosion of the fragile improvement in demand from April’s low, after a pickup in Covid-19 cases in some states and new quarantine measures in the New York City area and Chicago that have kept fliers from resuming travel.

The airline is still burning through $40 million a day, the executive told reporters Wednesday, adding that it could no longer count on a further round of government support to cover staff costs beyond Oct. 1.

Overseas carriers including United’s alliance partner Deutsche Lufthansa AG and British Airways have already announced plans to shed large parts of their workforce, with airline and finance executives not expecting global demand to recover to 2019 levels for between three and five years.

American Airlines Group Inc. has warned it may have as many as 20,000 more staff than it needs to handle reduced demand, and may also have to issue furlough notices.

United employs 95,000 staff world-wide, and the potential furlough notices cover 45% of its domestic employees, though thousands have already taken buyouts in a program open through July 15. Unpaid leave and other offers also could ultimately reduce the number of involuntary cuts. Another United executive said the number of involuntary cuts required should be clearer by mid-August.

“There is definitely an appetite with our employee base to participate in these voluntary programs,” the executive said, adding that 26,000 had taken part in one or more of them this year.

The airline said those receiving mandatory notices under the Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act of potential furloughs include 15,000 flight attendants, 2,250 pilots and 11,000 customer service staff. Employees would be rehired when demand recovers.

“The United Airlines projected furlough numbers are a gut punch, but they are also the most honest assessment we’ve seen on the state of the industry,” said Association of Flight Attendants-CWA President Sara Nelson.

Airline executives said the hoped-for recovery in leisure travel had started to fizzle as Covid-19 cases rose sharply, while business flying remains subdued.

The drop-off has been most acute at United’s Newark, N.J., hub, where near-term net bookings were about 16% of year-earlier levels as of July 1, according to the presentation to airline employees. Just weeks earlier, net bookings there had climbed to about a third of last year’s levels. The bookings metric, which is the difference between new reservations and cancellations, has also started to fall in other hubs.

“There’s a step back in demand, even further than where we are,” said the United executive.

At best, United expects to operate 40% of its pre-pandemic schedule by the end of the year, though it could flex that up or down, the executive said. The airline now expects to operate about 35% of its year-ago schedule in August, an increase from July but pared back slightly from the plans it announced last week.

Other carriers including American Airlines and Delta Air Lines Inc. have cut their August flying plans over the past week.

Updated: 8-17-2020

Japan’s Economy in Deep Hole After Second-Quarter Plunge

GDP falls 7.8% in April-June period compared with previous quarter after coronavirus pandemic closed many businesses.

Japan’s economy shrank slightly less in the April-June quarter than that of the U.S., but economists said it still had a long way to go before recovering from the coronavirus pandemic and a tax increase.

Gross domestic product in Japan fell 7.8% in the second quarter of 2020 compared with the previous quarter, the worst drop on record in the period since 1980, when comparable data began to be available. The contraction was sharper than the previous record of minus 4.8% in January-March 2009 after the global financial crisis.

“We will continue to take all possible policy measures to bring the economy—which likely bottomed out in April and May—back to a growth path led by domestic demand,” Economy Minister Yasutoshi Nishimura said Monday.

The new coronavirus forced many retailers and other businesses to close during a state of emergency in April and May and blocked virtually all foreign tourists from visiting Japan. As a result, private consumption, which accounts for about half of gross domestic product, fell 8.2% from the previous quarter. Exports, a figure that includes spending by foreign tourists in Japan, fell 18.5%.

Japan, the world’s third largest economy after the U.S. and China, fared better than Western peers, which imposed stricter lockdowns. The U.S. economy shrank 9.5% in the quarter, while major European economies generally shrank more than 10%, including a 20% drop in the U.K.

Asia has picked up more quickly. In China, where the virus was largely quelled by March, GDP in the second quarter rose 11.5% compared with the previous quarter, while South Korea’s GDP fell 3.3% in the quarter.

Although it did slightly better than Western peers, economists said Japan has still dug itself a deep hole that won’t be easy to get out of. Unlike the U.S., it was already headed for a recession early this year because of an increase last October in the national sales tax to 10% from 8%. The latest decline was the third straight quarter of contraction.

“If you look at the April-June results alone, Japan seems better. But Japan’s economy had already contracted in the October-December quarter, before the virus spread,” said Naomi Muguruma, an economist at Mitsubishi UFJ Morgan Stanley Securities. “Judging by the pace of the fall from its peak, Japan is no better than other Western countries.”

Ms. Muguruma said it would likely take until late 2022 or 2023 for the size of Japan’s economy to get back to where it was in mid-2019, while she said the U.S. was likely to recover to its pre-pandemic level before that.

On an annualized basis, which reflects what would happen if the second-quarter pace continued for a full year, Japan’s economy shrank 27.8% in the April-June quarter.

Economists say the second-quarter pace won’t continue and a recovery from the bottom has begun with most businesses open again. The question is how quickly the recovery will happen amid a second wave of infections throughout Japan that worsened in July.

Mizuho Securities economist Toru Suehiro said consumption would weaken again in the final quarter of the year as more people lose their jobs and companies scale back winter bonuses.

The resurgence in coronavirus cases may also weigh on domestic spending. Yuriko Koike, the governor of Tokyo, has asked people to avoid holding parties or traveling during their summer vacation. Many followed her advice, with train stations largely quiet last week when families would normally be traveling around the country on vacation.

Updated: 11-13-2020

Santander Plans 4,000 Job Losses, Adding To Wave Of Cuts

Banco Santander SA plans to cut as many as 4,000 jobs in Spain, adding to a global wave of staff reductions across the financial industry.

The lender told union leaders on Friday it will lay off as much as 13% of its Spanish workforce and close as many as 1,000 branches after the pandemic boosted a switch by customers to digital channels, according to two people with knowledge of the matter.

The lender also plans to relocate 1,090 more employees into other units, the people said, asking not to be named as the matter is private.

Banks worldwide have announced staff reductions of more than 75,000 workers and are set to surpass the 80,000 cuts made last year, according to calculations by Bloomberg. Britain’s Lloyds Banking Group Plc last week announced it was cutting about 1,070 roles, mostly at its technology and retail units. Dutch lender ING Groep NV expects 1,000 reductions by the end of 2021.

Other Spanish lenders are also making cuts. Banco de Sabadell SA is in talks with unions to shed as many as 1,800 workers while CaixaBank SA and Bankia SA are expected to announce a round of job cuts and office closures to generate 1.1 billion euros of cost savings as part of a merger to form Spain’s largest domestic bank.

Spain has been hit particularly hard by the Covid-19 pandemic, recording some of the highest infections in Europe. The country’s retail-focused banks are especially susceptible to the monetary policy of the European Central Bank, which has driven interest rates deeper into negative territory in response to the virus, making profit from lending harder to generate.

Santander said last month it’s accelerating plans to cut costs in Europe. It said it will reach a target to reduce costs by 1 billion euros by the end of 2020 ahead of schedule and plans to generate another 1 billion euros of savings by the end of 2022.

The bank is adjusting its distribution network to respond to the rapid rise in digital transactions, which were accelerated by a three-month lockdown in Spain, Chief Financial Officer Jose Garcia Cantera said in a Bloomberg TV interview last month.

Santander last year agreed with unions to cut more than 3,000 jobs as part of the integration of Banco Popular Espanol SA, which it bought in 2017 as part of a resolution coordinated by the European Union. The lender has also cut 140 branches in the U.K. and 2,000 jobs in Poland.

Updated: 2-14-2021

U.K. Economy Suffers Biggest Slump In 300 Years Amid Covid-19 Lockdowns

Lockdowns in Britain contributed to the largest contraction of the world’s major economies in 2020.

The U.K. economy recorded its biggest contraction in more than three centuries in 2020, according to official estimates, highlighting the Covid-19 pandemic’s economic toll on a country that has also suffered one of the world’s deadliest outbreaks.

Though the U.K. is grappling with a new, highly contagious variant of the coronavirus, Prime Minister Boris Johnson is hopeful that a rapid vaccination drive will permit a gradual reopening of the economy in the coming months, paving the way for a consumer-driven rebound later in the year.

Gross domestic product shrank 9.9% over the year as a whole, the Office for National Statistics said Friday, the largest annual decline among the Group of Seven advanced economies. France’s economy shrank 8.3% and Italy’s contracted 8.8%, according to provisional estimates. German GDP declined 5%. The U.S. shrank 3.5%.

However, the data showed the U.K. economy grew at an annualized rate of 4% in the final quarter of the year, aided by government spending and a small uptick in business investment.

The decline in U.K. GDP in 2020 was the largest in more than 300 years, according to Bank of England data, though the preliminary estimate is likely to be revised. BOE data shows the economy last recorded a comparable drop in 1921, when it shrank 9.7% during the depression that followed World War I. The economy last recorded a bigger contraction in 1709, when it tumbled 13% during an unusually cold winter known as the Great Frost.

Britain was hit especially hard in the second quarter of 2020 as a nationwide lockdown took effect. Social distancing and the closure of restaurants, bars, hotels and theaters were painful for the economy, where a higher share of national income is spent on recreation and similar services that require face-to-face contact than in other comparable economies.

The U.K. also kept restrictions on daily life and the economy in place for longer than some of its peers as it struggled to bring down Covid-19 case loads, limiting the extent of its post-lockdown recovery in the summer. The U.K. has suffered one of the worst Covid-19 outbreaks, with more than 120,000 deaths linked to the virus and at least four million people infected. On a per-capita basis, the death toll in the U.K. is higher than the U.S. and other hard-hit large countries including Italy, France and Brazil.

The U.K. has, however, raced ahead of many other advanced economies in the speed of its vaccine rollout, putting it on course for a speedier recovery, according to economists. British regulators were the first in the West to authorize a coronavirus vaccine in early December. Data through Thursday shows the U.K. has given at least one dose of vaccine to around a fifth of its population. That compares with 14% in the U.S. and 4% in France and Germany.

The Bank of England said this month that it expects a sharp rebound in consumer spending in the second half of the year. Government support programs have kept a lid on job losses and supported household incomes. Andrew Haldane, the U.K. central bank’s chief economist, has likened the economy to “a coiled spring” ready to release pent-up spending. Mr. Johnson is due to set out plans for a phased reopening of the economy later this month.

Progress with the vaccination drive means some businesses are starting to look forward to a revival later this year, and a strong 2022.

The arts-and-entertainment sector, for instance, was particularly hard hit during the pandemic, with output down almost two thirds in December compared with February last year, the month before the pandemic changed the direction of the U.K. economy.

“It feels to me that we will be back up and running in May,” said Tim Richards, chief executive of Vue International, which operates cinemas in nine European countries, including the U.K. He said he believes his cinemas can expect a burst of activity as a backlog of blockbusters hits the screens this year.

“We are going to be squeezing three years of movies into a 12-to-18-month period,” he said.

In the short term, economists expect a rocky few months. A resurgent epidemic, fueled by a highly contagious variant of the virus that has since spread around the world, led Mr. Johnson to tighten restrictions first in November and then impose another nationwide lockdown in early January.

Economists expect the economy to shrink again in the first quarter now the new lockdown is in place. First-quarter activity is also expected to take a hit from Brexit, as companies grapple with new customs procedures and other barriers to trade with the European Union that came into force at the end of the year.

The depth of the U.K. slump also means it has more ground to make up to recover the losses experienced during the pandemic. Its economy at the end of the year was 7.8% smaller than it was at the close of 2019 before the coronavirus swept the world. That compares with a shortfall of 5% in France, 3.9% in Germany and 2.5% in the U.S.

5-3-2021

Poland Says Ready To Ratify EU Stimulus Fund On Tuesday

Poland will most likely ratify the European Union’s pandemic stimulus in a parliamentary vote on Tuesday after the government won backing for the plan from one of the opposition parties.

The three-way coalition has for weeks lacked the majority to approve the bloc’s 800 billion euro ($968 billion) recovery fund due to internal disagreements. In the end, the ruling Law and Justice party agreed to demands from the Left in exchange for its support.

“Everything indicates there’s a majority in favor of the pact,” Waldemar Buda, a deputy minister of EU funds and regional policy, said on Friday. “Our understanding is that the support from the Left is real.”

With its decision to call a special parliament session next week, the bloc’s largest eastern member is seeking to allay concerns it’ll be a laggard in the ratification process.

Polish government will send its European Union-funded national recovery plan for approval by the European Commission on Friday even as the deadline for submissions has been extended.

“Poland doesn’t want to wait and intends to be somewhere in the middle between the countries that are ready with the Fund and those that have yet to work on it,” Buda said.

The government’s more comprehensive investment and development plan known as the New Deal is likely to be unveiled on May 15. It’s going to outline in detail how the Poland wants to help the economy emerge from the pandemic, he said.

Bond Vigilantes Swarm European Economies Where Inflation Is HotBond markets are famous for pushing their agenda, and in east Europe right now, they’re pushing for rate increases, never mind what central banks have to say on the matter.Yields on bonds of Hungary and Poland are rising faster than anywhere else in Europe.Hungary’s jumped 32 basis points last week, signaling traders are primed for rate liftoff as inflation roars back to life ahead of widespread economic re-openings this summer.Like peers in Frankfurt, central bankers in Hungary and Poland have signaled they’re in no rush to curb inflation that may turn out to be temporary, preferring to wait and foster still-fragile economic recoveries from the pandemic.Traders are less patient. In Hungary, market-implied pricing shows expectations for 130 basis points of rate hikes in two years, according to Bloomberg data.

“The central bank is walking a tightrope here,” said ING economist Peter Virovacz. “If it manages to communicate in a credible way that it believes CPI would return to its 2%-4% tolerance band next year, it can wait out the spike and avoid a hawkish cycle.”

The situation brings to mind the quip by political adviser James Carville that when he dies he wanted to come back as the bond market because “you can intimidate everybody.”

Carville was talking about traders who pushed up yields in protest against a ballooning budget deficit in the mid-1990s, but there are parallels with the Hungarian and Polish bond selloff on concerns that an economic boom will create an inflation spiral.

These latter-day vigilantes may be gaining the upper hand, with strategists at JPMorgan Chase & Co. reiterating their advice to stay underweight bonds in central and Eastern Europe.

A premature end of purchase programs is a big risk for Poland, where the central bank has bought the equivalent of 48% of issuance and in Hungary where it accounts for almost a third of purchases, according to JPMorgan.

QE Conundrum

If Polish policy makers bring forward their timetable for raising rates, the central bank would also have to wind down its quantitative-easing program, potentially removing the current backstop for the market.

One Polish policy maker, Eugeniusz Gatnar, recently called for a rate increase in June. Yet his voice remains in the minority on the 10-person panel. Polish central bank Governor Adam Glapinski has said that rates will stay at their record low until the end of the current policymakers’ term, which ends in early 2022.

Still, the inflation threat may be real: in Hungary the pace of annual consumer prices recently accelerated to 5.1%. In Poland it’s running at 4.3%. Both blew past the upper limit of the central banks’ tolerance range, and compare with an inflation reading of 4.2% in the U.S. that sent markets into a tailspin last week.

“With inflation surprising to the upside and growth on the mend, we think the market narrative will increasingly focus on the sustainability of QE in CEE,” according to JPMorgan emerging market strategists including Saad Siddiqui.

Updated: 3-7-2022

U.S. Retirement Funds, Heavy On Stocks, Brace For Losses

A sustained downturn could squeeze state and local government budgets

Volatile stock markets are eroding the retirement savings of America’s teachers and firefighters after public pension systems ended last year with equity holdings at a 10-year high.

Public pension funds had a median 61% of their assets in stocks as of Dec. 31, up from 54% 10 years ago, according to Wilshire Trust Universe Comparison Service. Since then, the Russia-Ukraine War and expectations that the Federal Reserve will raise interest rates this month have battered equity prices, reducing those holdings by billions of dollars.

At the nation’s largest pension fund, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, total reported holdings have fallen to $475 billion as of March 2 from $482 billion at the end of January. The S&P 500’s total return was minus 2.71% during the same period. Roughly half of the California worker fund is in stocks.

The situation highlights public retirement funds’ enduring dependence on the stock market and the potential impact on local government services and municipal-bond prices if losses continue. Smaller retirement systems tend to rely even more heavily on stocks than larger ones, which are more likely to seek returns from private-market assets like infrastructure and private equity.

U.S. state and local government pension funds control more than $4 trillion in public-worker retirement savings but will need hundreds of billions of additional dollars to cover promised future benefits. Over the past 12 years, blockbuster stock performance has swelled pension coffers, bringing state and local governments closer to being able to cover those liabilities and taking some of the pressure off taxpayers already burdened by high pension costs.

A downturn, however, could ultimately squeeze state and local budgets. That is because when pension-fund returns fall short, the workers and government employers that pay into them end up helping to make up the shortfall.

Annual pension contributions are already a drag on the finances of some cities and states, leaving less money for operations and debt payments and leading to credit-rating downgrades.

Research firm Municipal Market Analytics views a sustained market correction as the biggest threat to state and local general-obligation-bond prices.

“State pensions often have an allocation to equities that is greater than the size of [the states’] annual budgets, so a correction in equity prices can ultimately have an outsize impact on the state,” said Municipal Market Analytics partner Matt Fabian.

States and cities cut services, laid off workers and rolled back benefits for new employees after the 2007-09 recession took a huge bite out of U.S. public-pension-fund holdings.

Government finances today are far from that type of austerity scenario. With the S&P 500 returning double-digit gains in nine of the past 12 calendar years, pension funds have built back their holdings. Over the past two years, federal Covid-19 aid and rising tax revenues from the stimulus-fueled economic boom have bolstered municipal budgets.