Millennials Are Still Catching Up From The Last Recession. Now They Face a New One.

Millennials take stock of their finances and prepare for financial uncertainty yet again. Millennials Are Still Catching Up From the Last Recession. Now They Face a New One.

In the fall of 2008, Rebekah Frank applied to graduate school. At the time, housing foreclosures, bank bailouts and recession fears ruled the election-year debate stage.

Related:

A Guarded Generation: How Millennials View Money And Investing (#GotBitcoin?)

‘Playing Catch-Up In the Game of Life.’ Millennials Approach Middle Age In Crisis (#GotBitcoin?)

As More Millennials Rent, More Startups Want To Lend To Them (#GotBitcoin?)

“Being under debt, I hate that feeling,” she said. “It gives me so much anxiety.”

Now, Ms. Frank and millions of other young Americans are again facing the prospect of a new, sudden recession—and she is terrified of going back into debt. The two bars where Ms. Frank works closed last month, following stay-at-home orders. She became one of the 22 million Americans seeking unemployment benefits.

Graduating during the last financial crisis had far-reaching financial consequences for many young Americans. In April 2010, the unemployment rate for those 20 to 24 years old reached a peak of 17.2%. The earnings losses of those graduating into a recession take up to 10 years to disappear, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Like Ms. Frank, many young Americans felt as though they were just getting back on their feet before the pandemic shut down the U.S. economy.

The specter of another recession—coupled with the stress of the pandemic and self-isolation—can resurrect many of the negative feelings and memories from the last one, said Lauren Hersch Nicholas, associate professor of public health at Johns Hopkins University.

In 2013 research analyzing the effects of the 2008 recession, Prof. Nicholas saw more people experiencing a sudden loss in wealth. This led to a “recession depression,” or growth in reported feelings of stress and negative mental health. Prof. Nicholas also found a “large effect”—a 6.2 percentage point increase—in the use of antidepressants and other prescriptions to battle this “recession depression.”

“I think this is a very scary time for a lot of people,” she said. “Every time you look at the news, there’s been another huge increase in the unemployment rate. There’s this feeling of ‘If I can’t do my job, is the social safety net even going to be there for me?’ and it’s increasingly uncertain with the current types of jobs a lot of people have.”

This sense of uncertainty can also lead to a feeling of paralysis, said Dan Ariely, a professor of behavioral economics at Duke University.

He described a feeling of learned helplessness that he sees in people continually set back by unpredictable financial situations. Without understanding the scope of a financial crisis and its ramifications, people struggle to find a sense of resiliency.

“We can receive the same amount of bad luck or bad consequences, but if we don’t know why it’s coming, we have a much harder time understanding it and a much harder time recovering psychologically,” he said. “I think in the financial crisis, we got some explanations. Here, we don’t even understand the enemy.”

Even graduating into a recession didn’t adequately prepare many for a new economic downturn. The recovery of the past decade presented many opportunities for many Americans. But as the cost of living rose and wages for many stagnated, millennials weren’t always able to take advantage of opportunities.

Millennial households had an average net worth of about $92,000 in 2016, adjusted for inflation. That is nearly 40% less than Gen X households (people born between 1965 and 1980) had in 2001 and about 20% less than baby boomer households (born from 1946 to 1964) had in 1989, according to Federal Reserve data.

“They’re very ill-prepared for catastrophe,” Prof. Ariely said. “That is tough for the millennials, because it’s a generation that is very optimistic—or was, optimistic.”

As Ms. Frank found out, it’s hard to save for a rainy day when it seems to never stop raining.

“Because I prioritized paying my loans off, I had payments every month and I normally would have been putting that aside, so my income was going up at a slower rate than the cost of living went up,” she said.

Ms. Frank said that while she worked hard to get out of debt, she did so at the expense of her savings account. She didn’t build as much of an emergency savings fund as she now wishes she had.

Prof. Nicholas said she expects to see more people experiencing many of the same mental health effects she previously studied—depression, anxiety, stress and more. But the unique circumstances of this downturn make it harder to understand how people will cope.

“I have a feeling this will be a completely different sort of recession than the one we saw in 2008,” said Ms. Frank. “It feels like a thing I don’t understand, like a lot bigger of a monster than the last one did, at least to me.”

Updated: 4-20-2020

Coronavirus Deepens Millennials’ Feeling They Can’t Get A Break

One of the great aftershocks of the crisis will be its impact on the economic trajectory and political attitudes of people born in the 1980s and 90s.

Put yourself in the shoes of a 32-year-old American. You graduated from college in the spring of 2009, loaded up with student-loan debt because that’s what the system encouraged you to do.

You walked into the worst recession since the Great Depression, which prevented you from moving onto the professional track you were promised. For a decade, you scratched and clawed to catch up, perhaps putting off getting married, buying a car, buying a house and having children along the way. By the beginning of this year, with the economy humming, you felt you finally caught up.

Then coronavirus struck. You and your friends, while less susceptible to the ravages of the virus itself, find you are the most likely to lose a job, wages and health insurance amid the crisis. Your faith that the economy will bounce back is, understandably, lower than everyone else’s—and your cynicism about the political and economic system that allowed all this to happen has deepened.

As all that suggests, one of the great aftershocks of the coronavirus crisis will be its impact on the economic trajectory and political attitudes of millennials, roughly defined as Americans born in the 1980s and early 1990s. Before this, they already have lived through two major shocks, the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the financial plunge of 2008 and 2009.

Beyond those jolts, they also have seen rising income inequality, and emerged as perhaps the first cohort in American history to believe life for them won’t be better than it had been for their parents. As a result, they don’t seem as inclined as their elders to see silver linings in the current virus upheaval.

That certainly is the picture that emerges from a new Wall Street Journal/NBC News poll. It found that voters aged 18-34 are more likely than any other age group to report having lost a job during the current crisis. In fact, that age group is most likely to have experienced at least one of four potential economic shocks caused by the virus crisis: loss of a job, loss of health insurance, a cut in pay or worry about job and pay loss.

Overall, just 13% of these younger Americans rate the current state of the economy as good or excellent, compared with 28% of Americans aged 35 to 49. They are less likely than any set of older Americans to think the economy will bounce back in the next few weeks. Among the population at large, almost three-quarters say the crisis is bringing out the best in America; only about half of those aged 18 to 34 feel that way.

It’s common, of course, for younger people to be a bit jaded about the world being prepared for them by their elders. For today’s millennials, the coronavirus pandemic may simply be adding to that feeling. Young Americans are the least satisfied with the federal government’s response, the poll indicates.

The political impact of these cumulative experiences is significant. Ben Wessel, a young activist who leads NextGen America, a progressive organization dedicated to increasing voter turnout among young Americans, describes the attitude this way: “Anxiety caused by all these crises manifests itself in a belief that leaders can’t really ever be trusted—that it’s gotta be us that makes a change.” He adds: “That means no one is looking for a singular leader to fix it. We don’t need a hero.”

Before the coronavirus hit, the shocks millennials already had endured had left them feeling “somewhat detached from the political system,” says Democratic pollster Celinda Lake. Indeed, a report by the GQR polling organization prepared early this year for NextGen America found that a majority of voters under the age of 35 were “unenthusiastic” about voting in 2020. “A basic dislike of politics keeps many from voting,” the report said.

It’s impossible to know right now whether the shock of the coronavirus will drive young voters further away from the political process, or draw them into it. If they do show up to vote, it’s clear they will be a force for the presumptive Democratic nominee, former Vice President Joe Biden. In the new Journal/NBC News poll, voters aged 18 to 34 favored Mr. Biden over President Trump by a whopping 23-point margin, 54% to 31%.

Yet that endorsement of Mr. Biden apparently comes with no great enthusiasm. Just 25% of those young voters reported having positive feelings about the former vice president personally, compared with 44% with negative feelings.

Broadly speaking, millennials are advocates for what Ms. Lake calls “a major role for government” in society, and that may be more true now. But, there may be a disconnect, she notes: “You can’t have a big role for government if you don’t take part in picking the government.”

Updated: 5-24-2020

Summer Jobs Dry Up And Teens Face Highest Unemployment In Decades

Younger workers’ go-to positions at pools, restaurants, golf courses are hit by the coronavirus.

Young Americans are having little luck finding summer jobs.

Coronavirus outbreaks throughout the country have dried up many of the traditional opportunities that high school and college-age students rely on each summer. Junior workers seeking seasonal employment are striking out so much that the April unemployment rate for teens aged 16 to 19 hit 32%, marking a high not seen since at least 1948, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. As more teens hit the job market in June and July, when school is generally out, that rate typically climbs higher.

Teen unemployment had been steadily falling since the aftermath of the 2008 recession. Summer jobs had been rising in popularity, reflecting a healthy labor market. The pandemic swiftly put that trend in reverse. More than two million retail jobs disappeared in April as thousands of stores closed.

Restaurant owners are grappling with how many people to hire back as states lift lockdown measures around the U.S. Social distancing guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have also curbed many summer activities that provided positions to younger workers as swimming pool lifeguards and golf-course caddies.

Without a chance to earn money over the summer, young workers are missing out on thousands of dollars of extra income that could be used to help their families or put toward expenses such as tuition payments.

Chuck Montrie runs Bethesda Aquatics, which operates several neighborhood swimming pools in Bethesda, Md. In a typical summer, he employs between 60 and 70 lifeguards and swim coaches between the ages of 15 and 22. This year, he has made many offers but doesn’t know when he will be able to put people to work. Normally, Mr. Montrie’s summer hires would be getting the pools in shape for Memorial Day crowds, but the state’s pools remain closed until further notice.

“At this point, it’s a big unknown if we will pay our lifeguards or not,” he said. “Our guess is mid- to late June, but that’s just based on hope.”

Mr. Montrie also said he has had more students than usual who worked for him in the past come back this season and ask for jobs; many told him their summer internships were rescinded.

Matt Kaye, 22, is graduating from University of California, Los Angeles, next month and was recently furloughed from a clerical job at the school’s student union. He was hoping to work through September, giving him the summer to look for a full-time job opportunity in finance.

Mr. Kaye said he may start looking for other part-time work in July if he can’t find a full-time job by then. “It’s definitely been a huge blow to my confidence,” he said.

David Benowitz, chief operating officer of restaurant operator Craft and Crew Hospitality Inc. based in Wayzata, Minn., said it hires about seven to 15 employees for the summer at each of his company’s five locations. Mr. Benowitz said he has recently hired back some furloughed workers as Minnesota moves to relax some of its restrictions on bars and restaurants next month.

Rather than cutting back on summer hires, Mr. Benowitz said he plans to hire a few extra workers at each location to ramp up delivery capability. But students and younger workers will face a lot of competition for those jobs.

“We have a lot of people to choose from now. It was challenging to be picky before this. That’s turned 180 degrees now,” he said. “We can bring on A players at every position.”

Riverside Golf Club in Riverside, Ill., normally hires nearly 140 teenaged caddies with roughly 70 working on any given day, said Joe Green, the club’s caddie master. Courses are open but local laws don’t permit caddies to work this summer.

Mr. Green said many of his summer caddies can make between $5,000 and $6,000.

“I don’t see how we’re going to bring them back safe this year,” he said. “To me, it’s the best job these kids can have. It teaches discipline, social skills, networking. It’s a great learning experience.”

While traditional temporary jobs for young workers are in short supply this summer, teens could find work in warehouses and distribution centers, said Traci Fiatte, head of nontechnical staffing at recruiting firm Randstad N.V.’s U.S. division. She said students looking for summer work should be flexible and willing to take roles other unemployed people may not want.

“Be willing to take work that a mother of two can’t take,” she said. “Be flexible with overnight shifts, or doing delivery at the restaurant you used to work at.”

Updated: 6-8-2020

Recession In U.S. Began In February, Official Arbiter Says

Monthly economic activity ‘reached a clear peak’ in February, marking the end of the 128-month expansion that began in June 2009.

The U.S. economy entered a recession in February, the group that dates business cycles said Monday, ending the longest American economic expansion on record.

Monthly economic activity “reached a clear peak” in February, marking the end of the 128-month expansion that began in June 2009, said the Business Cycle Dating Committee of the National Bureau of Economic Research. It was the longest expansion in records back to 1854.

Recessions are typically defined as declines in economic activity that last more than a few months, and the NBER often takes more than a year to declare a recession officially under way. It also takes into consideration the depth and duration of the downturn and whether activity has declined broadly across the economy.

The committee said the new coronavirus pandemic and the subsequent public-health response have led to a downturn with different dynamics than prior recessions.

“Nonetheless, it concluded that the unprecedented magnitude of the decline in employment and production, and its broad reach across the entire economy, warrants the designation of this episode as a recession, even if it turns out to be briefer than earlier contractions,” the group said.

Many economists had believed the U.S. was in recession since at least March, when governments began ordering businesses closed and workers sent home in an effort to slow the fast-spreading virus.

Employment and consumer spending has plunged as Americans curbed travel, shopping and eating out, and businesses laid off employees. Gross domestic product, the broadest measure of economic output, fell 5% in the second quarter.

Employers shed roughly 22 million jobs in March and April, and the jobless rate hit 14.7%, a post-World War II high. Consumer spending, the economy’s key driver, plunged 7.5% in March and 13.6% in April, setting back-to-back record declines in records tracing back to 1959.

Signs are emerging that the economy may have hit bottom in May. Employers added 2.5 million jobs last month, the most added in a single month on records dating from 1948, and the jobless rate fell to 13.3%.

Still, employment remained down by nearly 20 million jobs since February. By comparison, the U.S. shed about 9 million jobs between December 2007 and February 2010, a period that covered the recession caused by the financial crisis.

The NBER’s recession-dating committee looks at gauges of employment and production, as well as incomes minus government benefits, to determine when a recession has begun. Many other countries use a different measure: two or more quarters of declining real gross domestic product.

The committee doesn’t comment on how long the recession may last, though many economists project a swift rebound this summer followed by a long, slow return to pre-pandemic.

The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office said last week the U.S. economy could take the better part of a decade to fully recover from the pandemic and related shutdowns. Gross domestic product will likely be 5.6% smaller in the fourth quarter of 2020 than a year earlier, despite an expected pickup in economic activity in the coming months, and the unemployment rate could still be in double digits by the end of the year, the CBO said.

Updated: 7-8-2020

Recession Forces Spending Cuts On States And Cities

Education takes the brunt of reductions; governments have cut 1.5 million jobs since March, with more expected.

State and local governments from Georgia to California are cutting money for schools, universities and other services as the coronavirus-induced recession wreaks havoc on their finances.

Widespread job losses and closed businesses have reduced revenue from sales and income taxes, forcing officials to make agonizing choices in budgets for the new fiscal year, which started July 1 in much of the country.

Governments have cut 1.5 million jobs since March, mostly in education, and more reductions are likely barring a quick economic recovery. In Washington state, some state workers will take unpaid furloughs. In Idaho, Boise State University cut its baseball and swim teams in an effort to save $3 million.

Dayton, Ohio, Mayor Nan Whaley says the city may have to cut up to 8% of its general fund budget, which pays for fire, police, roads, trash collection and other services.

“I’m concerned we’ll have to lay folks off before the end of the year,” Ms. Whaley said.

Nationwide protests sparked by the killing of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police have heightened attention to municipal budgeting. In many cities, protesters are demanding that police budgets be cut or money redirected toward social services.

Across the country, the weeks before July 1 were marked by a scramble to complete spending plans. The task has been complicated by uncertainty over the economic outlook, which depends largely on unknowns such as the course of the virus and how quickly a vaccine can be developed. As a result, budgets may have to be rewritten in the coming months.

“I don’t think you can overstate the amount of uncertainty that states are dealing with,” said Tracy Gordon, an expert on state and local budgets at the Urban Institute in Washington. “You’re asking revenue estimators basically to consult epidemiological models and public health experts and take account of all kinds of variables that are normally not part of their forecasts.”

Adding to the uncertainty: Many states pushed back the income-tax-filing deadline to July 15 from April 15, following the U.S. Treasury’s lead. While that should bring a short-term revenue boost, officials don’t know how much revenue to expect in the months ahead.

It is also unclear whether states will get more help from Congress, which in March provided $150 billion but limited its use for pandemic response. Dayton got about $8 million and will use it to buy face masks for residents, Ms. Whaley said.

The National Governors Association says states need another $500 billion in federal aid to make up for lost revenue. The U.S. Conference of Mayors says cities need $250 billion.

The Democratic-led House in May passed a bill that included $1 trillion to help state and local governments.

But Republican senators have paused discussion on another fiscal package until later this month.

Almost all states and local governments require balanced budgets. For now, they have largely avoided raising taxes to plug budget holes, opting instead to cut spending or dip into reserves.

In Georgia, Gov. Brian Kemp signed a budget bill that reduces spending by about 10%, including a $950 million cut to the main state education fund. Some poorer school districts rely on the state to cover 70% of operating expenses, said Margaret Ciccarelli, director of legislative services for Page Inc., the state’s teachers’ association.

“These are challenging times and the budget reflects that reality,” Mr. Kemp, a Republican, said in a signing ceremony on June 30.

Maryland imposed $412 million in cuts, of which $136 million will come from higher education, an 8% reduction. Funding was also reduced for Washington, D.C.-area transit system, neighborhood revitalization and drug treatment.

Such cuts, though painful, could have been worse, experts say. The decadelong economic expansion that ended in February allowed states to replenish rainy-day funds. The median state went into the crisis with reserves totaling a record 7.8% of its general fund budget, according to the National Association of State Budget Officers.

California lawmakers used $9 billion of their $16 billion rainy-day fund to help balance the $202 billion budget that Gov. Gavin Newsom, a Democrat, signed June 29. Even so, state employees will have to take up to two unpaid furlough days a month, and public colleges and universities face about $602 million in reductions.

Some states are putting off hard decisions. New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy, a Democrat, signed a $7.6 billion stopgap budget for the next three months, which cuts $1.2 billion in previously allocated spending.

With an uncertain outlook, officials are trying to maintain reserves in anticipation of more lean years.

“You may need to use it in 2022 and beyond,” said Brian Sigritz, director of state fiscal studies at the budget officers’ association. “They’re not expecting this decline to be a one-year or two-year thing.”

The fiscal squeeze comes as cities face demands to cut police funding in the wake of Mr. Floyd’s killing. Los Angeles redirected $150 million from the police department’s nearly $2 billion budget to social services.

In New York, Mayor Bill de Blasio and the City Council struck a deal that he said would cut the police budget by about $1 billion, to $5.2 billion, and protesters are demanding even larger reductions.

The Atlanta City Council narrowly defeated a proposal to hold back some police funding until the department presented a plan to become more inclusive and transparent.

Most years, Atlanta council members hear two to three hours of public comment on the budget. This year, they listened to about 50 hours, largely about police funding, said City Council President Felicia Moore. To comply with social-distancing efforts, people called in to record their comments rather than appear in person.

“We had calls from people all over the world,” Ms. Moore said.

Shrinking budgets could make it easier for city officials to heed calls to cut police funding, said the Urban Institute’s Ms. Gordon.

“When revenues are constrained is exactly when you have some flexibility to look at longstanding practices and ways of doing things and potentially changing that,” she said.

Updated: 8-10-2020

Millennials Slammed By Second Financial Crisis Fall Even Further Behind!!

Millennials: “This is not where I thought I would end up.”

Trump: “Give Me (4) More Years”

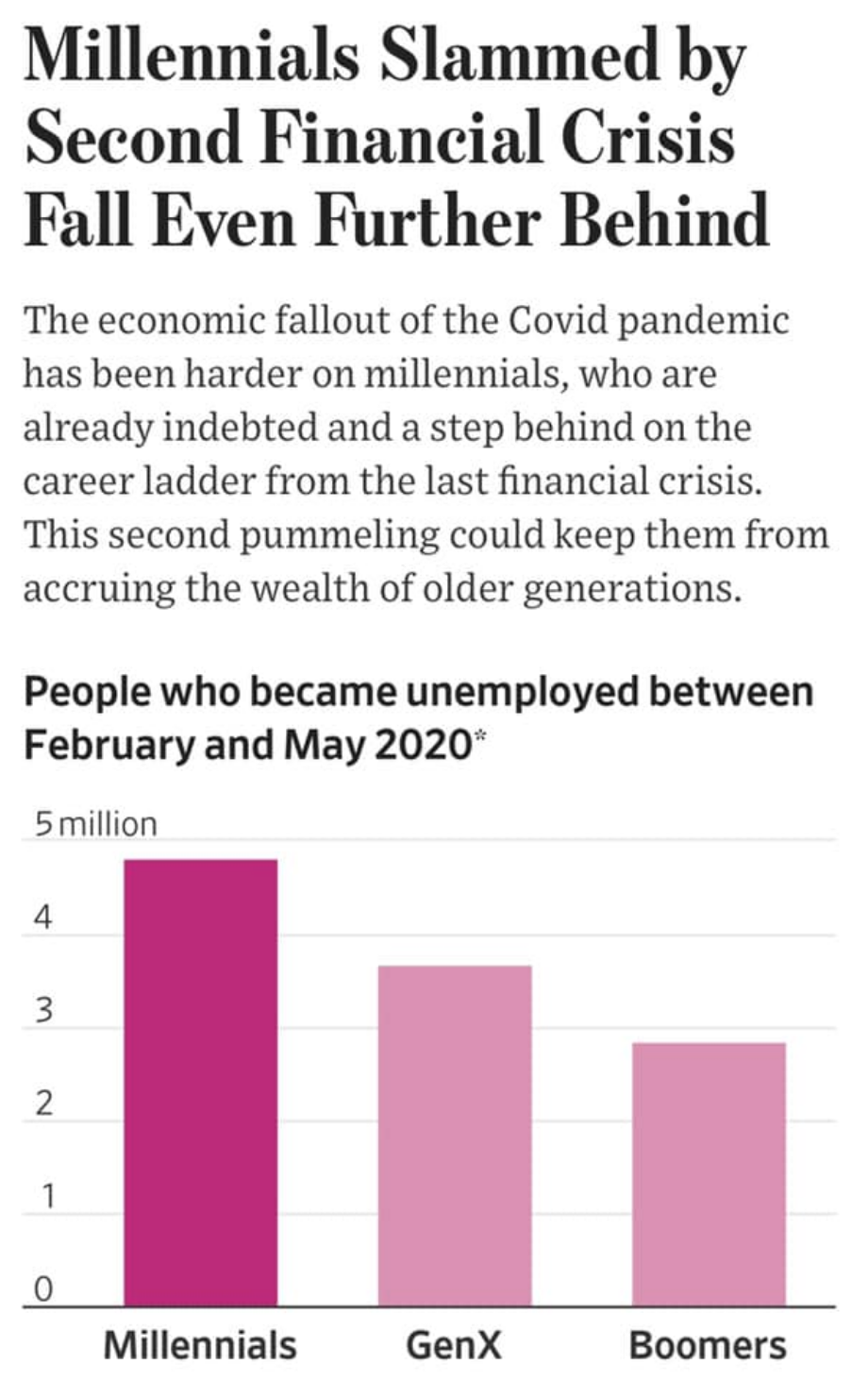

The economic fallout of the Covid pandemic has been harder on millennials, who are already indebted and a step behind on the career ladder from the last financial crisis. This second pummeling could keep them from accruing the wealth of older generations.

The economic hit of the coronavirus pandemic is emerging as particularly bad for millennials, born between 1981 and 1996, who as a group hadn’t recovered from the experience of entering the workforce during the previous financial crisis.

For this cohort, already indebted and a step behind on the career ladder, this second pummeling could keep them from accruing the wealth of older generations.

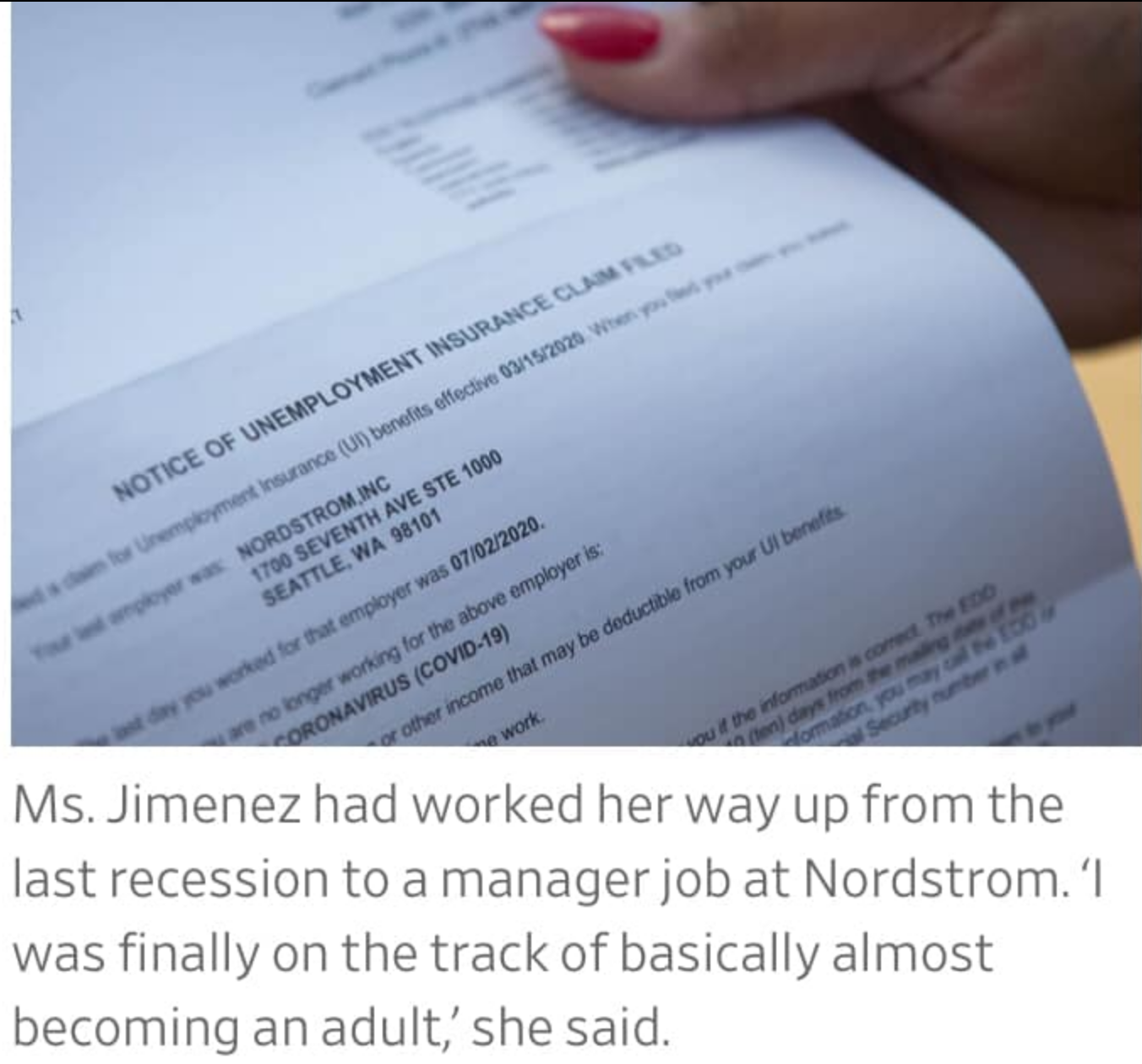

Jaclyn Jimenez put herself through college working for her father’s manufacturing company, but couldn’t find anything comparable when she graduated amid the economic slump of 2008. Even though she lowered her sights, she was turned down for roles from office assistant to drugstore worker.

As credit-card debt piled up, she took a job selling wedding gowns at a bridal salon, then leveraged that experience to land a sales position at Nordstrom. She was finally gaining traction, she says, having worked her way up to manager.

Then the pandemic struck the nation in February, sending the economy into a tailspin. She lost her job, and Ms. Jimenez has now joined the 4.8 million millennials who the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis says lost work since the new coronavirus triggered a recession. The group had more losses than the two previous generations.

“It’s been difficult to struggle so much and think that you’re getting somewhere, and you’re moving forward, and you finally see a glimmer of hope, and then this all hit,” said the 34-year-old Orange, Calif., resident. “Am I ever going to have an opportunity to have what my parents had?”

The 12.5% unemployment rate among millennials is higher than that of Generation X (born between 1965 and 1980), and baby boomers (1946 to 1964), according to May figures from the Pew Research Center.

One reason is that some of the hardest hit industries, including leisure and hospitality, have a younger workforce.

Millennials have found it fundamentally more difficult to start a career and achieve the financial independence that allowed previous generations to get married, buy a home and have children.

Even the most educated millennials are employed at lower rates than older college graduates, research shows, and millennials’ tendency to work at lower-paying firms has caused them to lag behind in earnings.

“It’s a sign that something has broken in the way the economy is working,” said Jesse Rothstein, professor of public policy and economics at the University of California, Berkeley, and a former chief economist at the Labor Department during the Obama administration. “It’s gotten harder and harder for people to find their footholds.”

As a result, the millennial generation has less wealth than their predecessors had at the same age, and about one-quarter of millennial households have more debt than assets, according to the St. Louis Fed.

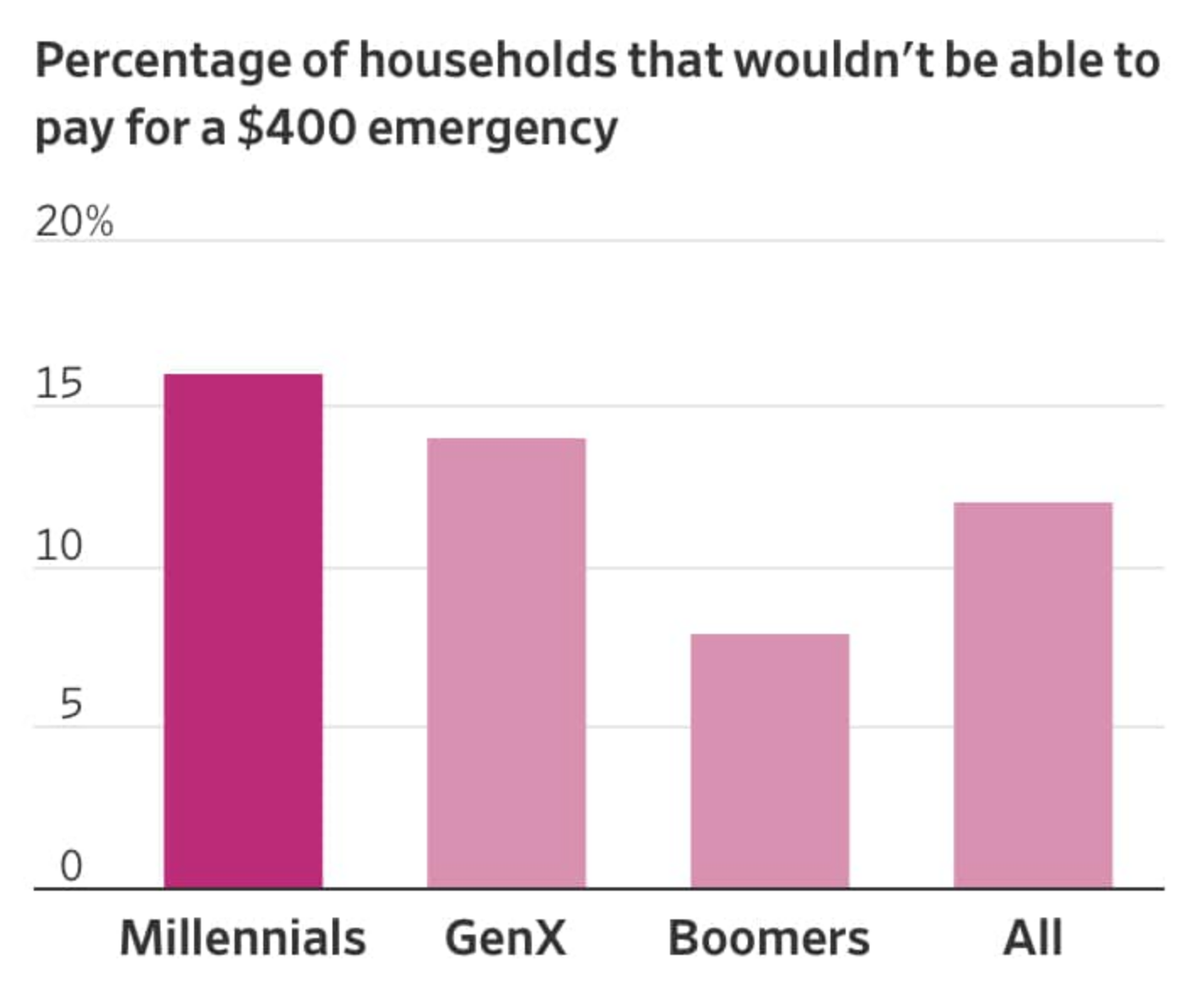

About one in six were unable to cover a $400 emergency expense before the pandemic started; that share is about one in eight among all Americans, the bank found.

Millennials are now at risk of falling further behind because they entered the pandemic in a weaker position than older Americans.

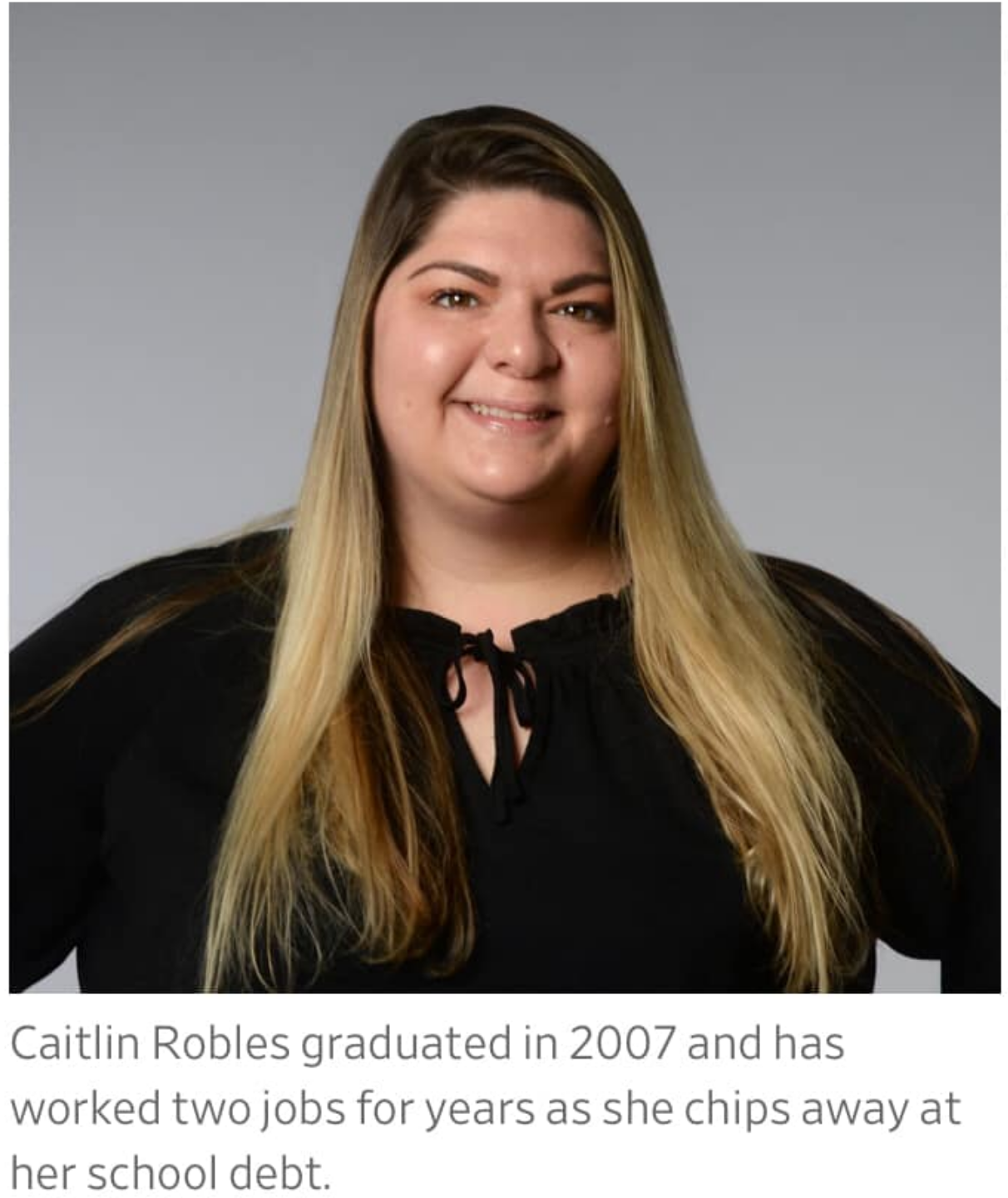

Caitlin Robles, 35, said she felt lucky to get a job maintaining a website for Sacred Heart University when she graduated from there in 2007 with a business management degree. But with $67,000 in student loans, she needed a second job to pay for them and cover $650 a month in rent to live with two friends in Milford, Conn.

Ms. Robles eventually got a second job working the front desk at a Massage Envy wellness franchise 15 hours a week. She planned to work there just long enough to make a dent in her debt.

Instead, she’s still working there nine years later and doubled her hours to pay the rising interest rates on her student loans and knee-surgery bills.

Even after being promoted at both jobs, to associate director of web content at the university and to assistant manager at the spa, the $70,000 to $80,000 she earned a year wasn’t enough to pay down all her debt. She skipped a family vacation to save money. Her 70-hour workweeks left little time for dating.

To improve her credit score and lower her interest rates, Ms. Robles last year borrowed $30,000 from her 403(b) retirement account to pay off her student loans. She planned to pay off that loan in five years and start saving so she could buy a home when she turned 40.

That plan got derailed in March when Massage Envy shut down because of the pandemic, leaving Ms. Robles without a second income for three months.

Since her location reopened in June, she has worked only seven hours a week because the company cut its hours and services. To conserve cash, Ms. Robles deferred payments on her retirement loan. Now she doesn’t know when she’ll be able to buy a home.

“I don’t want to work this way for the rest of my life,” Ms. Robles said. “I thought I had that figured out. And I don’t think I do now.”

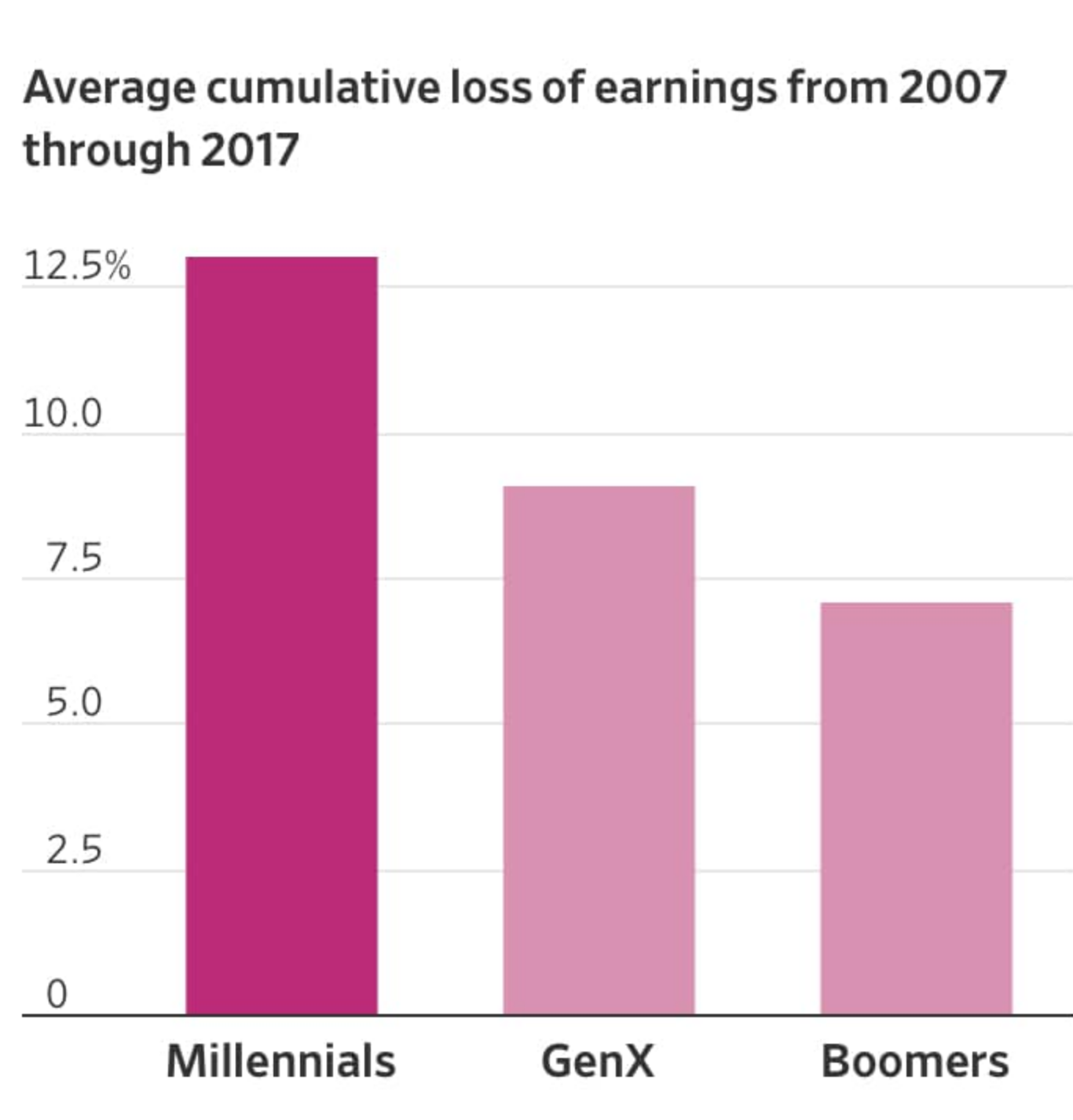

Economists are most concerned that millennials’ scars from starting their careers amid the last recession never went away.

Millennials on average missed out on more than $25,000 in pay, or 13% of their total earnings, during the decade that ended in 2017 as a result of the rising unemployment rate that started in 2007, according to an analysis published last year by Census Bureau economist Kevin Rinz.

That was a greater share than Gen X, which had their earnings reduced 9% over that time, and baby boomers, which didn’t get 7%. That’s mainly because millennials were less likely to work for high-paying employers than older Americans.

Although younger workers’ employment rates recovered more quickly than those of older workers, millennials’ earnings didn’t bounce back, Mr. Rinz found.

Demographers say that financial instability is prompting some millennials, who are aged 24 to 39 this year, to cohabit instead of wed, and to delay or forgo childbearing. Millennials helped push down the marriage rate to its lowest level on record in 2018, and drove the general fertility rate to an all-time low the following year.

“Exposure to something like this twice in the early part of your career,” Mr. Rinz said, “could certainly have important and negative long-term effects on people’s finances, on their work prospects and all sorts of other family outcomes as well.”

Millennials’ early headwinds mirror those of the G.I. Generation, born between 1901 to 1924, said Neil Howe. The economist and demographer coined the phrase “millennial generation” in 1991 with co-author William Strauss.

The G.I. Generation was first hit by recessions that followed the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918, and then the stock market crash of 1929 and the subsequent Great Depression. They recovered economic ground later in life thanks to a sharp rise in schooling and a booming post-World War II economy.

Michael Rafidi, a 35-year-old chef, spent more than a decade working at top eateries in Philadelphia, Washington and San Francisco while dreaming of opening his own restaurant.

In 2016, he started raising more than $1 million to develop an upscale Levantine restaurant that drew on his Palestinian heritage with dishes like smoked lamb and sumac carrots. He named it Albi (“my heart” in Arabic) and opened its doors in Washington’s hip Navy Yard on Feb. 20.

“I didn’t think twice about the timing being wrong,” Mr. Rafidi said. “D.C. is going in the right direction with restaurants. The dining scene is incredible. Everything was aligning perfectly.”

For the first few days, Albi was so popular that it was hard to get a table. Three weeks later, the pandemic forced Mr. Rafidi to shut down and switch to a limited takeout menu. He secured a Paycheck Protection Program loan. He said it isn’t enough to replace the lost revenue from operating at just over a third of his original capacity.

“I’m worried,” said Mr. Rafidi, who is relying on outdoor seating, a few inside tables and a newly added cafe serving pastries and coffee. “I put everything on the line these last couple of years to do this.”

Millennials with a bachelor’s degree have about four times as much wealth as their peers who lack that diploma, according to Ana H. Kent, a policy analyst at the St. Louis Fed. Yet the most educated millennials lag behind older college graduates in the job market.

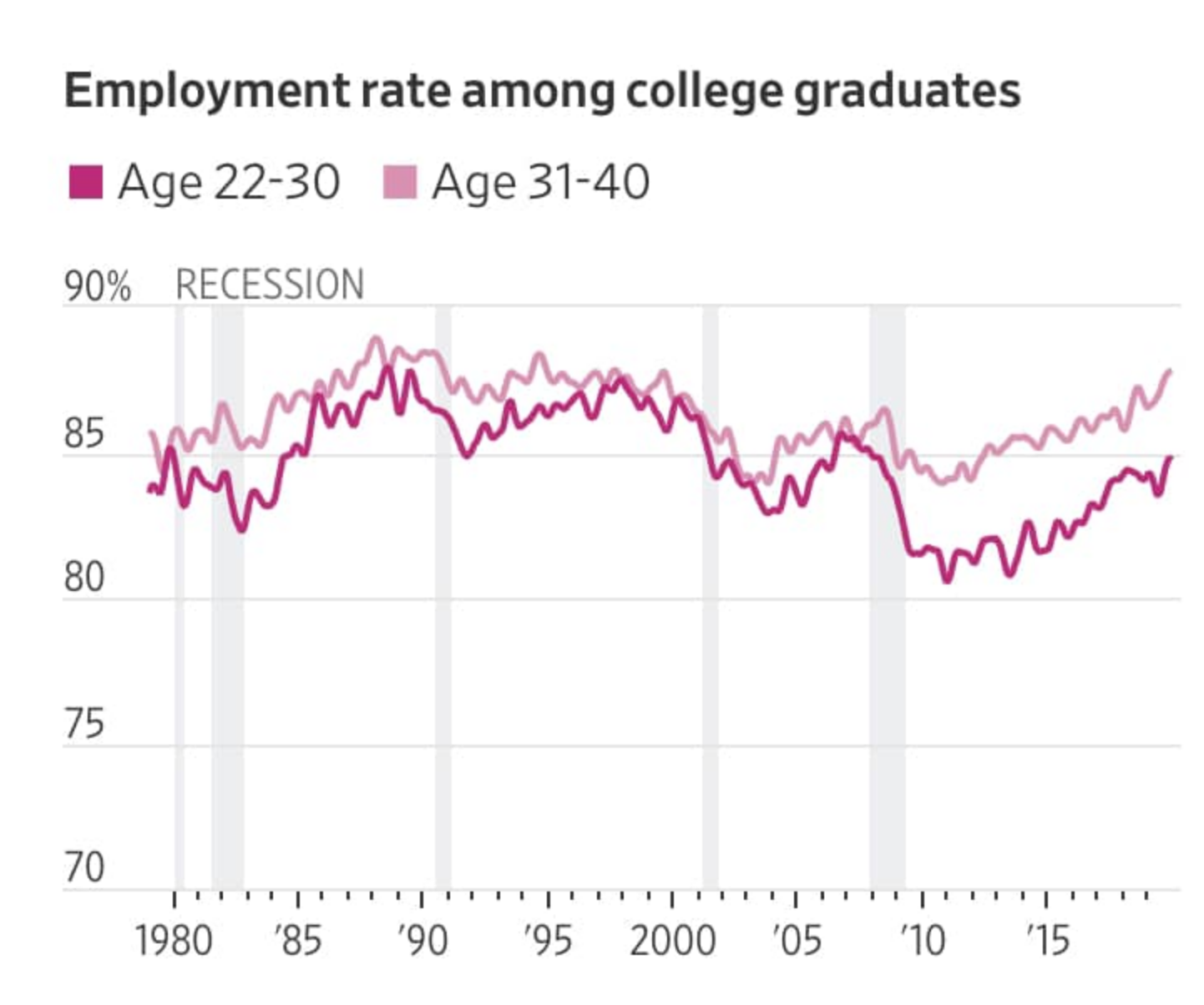

Berkeley’s Prof. Rothstein studied employment rates among recent college graduates and identified what he calls a dramatic structural break for the group that entered the workforce around 2005.

He found that each successive year’s group of college graduates has had lower employment rates relative to older workers in the same labor market than those before them.

Prof. Rothstein concluded that adverse early conditions permanently reduce college graduates’ employment prospects. That adds to a body of research showing that starting your career in a bad economy often carries a long-term penalty.

What surprised him was that when employment rates rose significantly following the 2007-09 recession for those already in the workforce, new entrants didn’t share in this improvement, he found in a paper he released last month.

Even college graduates who started their careers in 2015, and enjoyed several subsequent years of a strong labor market, were less likely to work.

For example, 24-year-old college graduates had an employment rate of 79.8% in 2015. Had the age-24 employment rate improved at the same rate as for older workers from 2009 to 2015, their employment rate would have been 81.6%, Prof. Rothstein found.

“It’s a finding that I don’t have a great explanation for,” he said. “I would have thought that the people who finished college in 2017, 2018 would be doing pretty well. But you don’t see that.”

Seeking to mitigate that penalty is Ankur Jain, an entrepreneur who founded the venture fund Kairos, which builds businesses that help make life more affordable for young adults. Last month, Kairos started to place thousands of young adults in home health-care jobs through CareAcademy and Care.com and pay for them to earn the necessary certification.

Although home health jobs typically pay low wages, Mr. Jain said the program will include a path toward becoming a licensed practical nurse, which pays more and can act as a springboard for a career in health care. “What we need to do is find ways to get people back on their feet,” said Mr. Jain, chief executive of Kairos.

Millennials have some advantages as they face a second severe recession. A larger percentage have college degrees than previous generations, which could pay dividends over time. They will also help fill gaps in the workforce as the large baby boomer cohort retires.

The young workers behind them, members of Generation Z, who this year are 23 and younger, have even higher rates of unemployment and less experience to buffer them from the economic fallout of the pandemic.

Ms. Jimenez, the former Nordstrom employee, paid her way through college at California State University, Fullerton, with the roughly $45,000 a year she earned helping run her father’s printed circuit boards design and fabrication business. She expected she would at least match that salary soon after graduating with a business degree in 2008.

But as she sent out resumes during the crisis, no one wanted to hire her. Even office manager or executive-assistant jobs required five years of experience that she didn’t have. As her father’s business took a turn for the worse, she started applying for hourly positions at CVS and Disneyland. They didn’t bite either.

Desperate for a paycheck, Ms. Jimenez took a few shifts a week at a bridal shop in Orange, where her mother worked. She was barely getting by when the bank foreclosed on her parents’ home, where she lived with her younger sister. Ms. Jimenez moved into an apartment with both of her sisters and a niece and leaned on her credit cards.

“That really locked me into being permanently behind,” she said.

By 2013, she was still struggling to get traction. She parlayed her bridal-salon experience into a job selling wedding dresses at Nordstrom in Brea, Calif., for $12 an hour plus commission. She made about $22,000 a year. Although she was grateful for the steady paycheck, her inability to find a professional job felt defeating, she said. “This is not where I thought I would end up.”

Still, she stuck with the upscale retail chain because it offered a path for advancement. Over the next six years, she moved up little by little, first to an interim wedding suite manager, then to an assistant manager in a few other departments. Last year, she clinched a job as service experience manager at the chain’s Riverside location, which paid $56,000 a year plus a $4,300 bonus.

Ms. Jimenez grew more optimistic about her career. She started thinking about one day becoming a Nordstrom regional manager, or even a director. With her bonus, she set her sights on whittling down the $12,000 of credit card debt she had accumulated during years of scraping by.

“I was finally on the track of basically almost becoming an adult because honestly I have never felt that way,” said Ms. Jimenez. “Then Covid hit.”

Nordstrom told workers in May that it would permanently close the Riverside store as part of a broader retrenchment. That put Ms. Jimenez out of a job in early July. Now she feels like “it’s 2008 all over again.”

Ms. Jimenez got $7,000 of severance that will help her pay the $700 a month she spends to live with her younger sister, a friend and the friend’s 7-year-old daughter. She is considering going back to school to earn an advanced degree in psychology so she can eventually become a therapist.

Recently a friend offered to help her get a job as a front office administrator at a dermatology practice in Newport Beach. It would pay about $15 to $17 an hour. She hasn’t decided whether to pursue it.

“I do feel like I’m starting back at square one,” she said.

Updated: 6-11-2021

Millennials’ Last Chance To Build Wealth

We’re easy to hate. We’ve been described as less patriotic. Some have accused us of killing marriage. Corporate research has even officially classified us as “self-centered.” Yes, I’m talking about millennials.

As the oldest of us turn 40 this year, I’d like to take a moment to highlight this very illuminating article. In it, my colleagues show something we hear a lot but rarely address head-on: Millennials are simply running out of time to build wealth before retirement. (That is, if you believe you’ll retire at all.) And the numbers show how far behind their parents they are, and why.

Millennials aren’t just whining. There are structural reasons for this imbalance. Many of us graduated into a recession, progressed through an uneasy recovery and seemed to find stability only to have it slapped in our faces when the pandemic hit.

The numbers don’t look good.

Older millennials had a net worth of $91,000 in 2019. For boomers? That figure was $113,000 — in today’s dollars — in 1989, when they were in their early 40s.

Millennials are paying 50% more for homes now than Boomers were in 1989 — meaning it’s more difficult to get into the housing market. Mortgage rates, however, are better.

Millennials have more student-loan debt but less in mortgage obligations than their Boomer and Gen X counterparts when they were 40.

What are we supposed to do? There are no easy answers. The good news is that as a generation, we are more open to talking about money than others. There are also signs that even if we’ve been cursed with a recession and a pandemic in the prime years of our careers, we may be willing to take bold steps to make our jobs work better for us, even if that means walking away.

I myself am unsure if I’ll manage to catch up to previous generations. But I’m hopeful about the end of this pandemic and am beyond ready for a fresh start.

Fewer Young Men Are In The Labor Force. More Are Living At Home

For 25- to 34-year-olds, the two trends add up to a failure to launch.

Are young men living at home because they’re not working? Or are they not working because they’re living at home? Hard to say, but either way, the trends are clear: More American males aged 25-34 are living in a parent’s home, and fewer are participating in the labor force.

There’s no way to tell from this set of data what the overlap is: i.e., how many young men are living in the home of a parent or parents while also being out of the labor force. But there’s undoubtedly a connection. The parental home can be a refuge, but also a trap that keeps young men from launching their careers.

(Labor force participation by women of the same age increased rapidly for decades, though it has sagged recently. They’re also less likely to live in a parent’s home at that age.)

The Conference Board, a business-supported research organization, has created a chart breaking down the living-at-home contingent by educational attainment. For those with a bachelor’s degree or more, the increase has been modest, from around 10% in the mid-1990s to around 13% this April. For those with less than a bachelor’s degree, the increase has been steeper, from around 15% in the mid-1990s to nearly 25% this April.

The Conference Board states unequivocally: “A growing percentage of young men without a bachelor’s degree are living at home. This trend is contributing to a lower labor force participation.”

To be out of the labor force means that you don’t have a job and you’re not actively looking for one. Improvements in video-game technology help account for young men’s detachment from the labor force, according to a 2017 paper by economists from Princeton, the University of Chicago, and the University of Rochester.

It found that an increase in the playing of video games by men 21-30 accounted for somewhere between 38% and 79% of the differential in the decline in their time spent on paid work vs. the smaller decline of work by older men.

Make no mistake, though, for a young man who’s not working the couch isn’t a bed of roses. “About half of prime age men who are not in the labor force may have a serious health condition that is a barrier to working,” the late Princeton economist Alan Krueger wrote in the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity in 2017.

Added Krueger: “Nearly half of prime age men who are not in the labor force take pain medication on any given day; and in nearly two-thirds of these cases, they take prescription pain medication.”

Updated: 6-23-2021

Millennials, The Wealthiest Generation? Believe It

The world has changed since boomers were young adults, and so has the value of housing, education and a steady job.

Millennials spent their early adulthood dogged by two large recessions, rising housing prices and exploding student debt. It’s no wonder they’re less likely, even as they approach 40, to have many of the traditional trappings of adulthood, including marriage and homeownership.

But a closer look at the data and a more inclusive definition of wealth reveals this often-maligned group is doing quite well. In fact, most are doing better than previous generations.

In modern history, each generation has typically been richer than the last. If millennials are falling behind, it could be a sign of the end of a multi-generational boom in prosperity. But comparing generations is hard. In large part because as the world changes, so do the markers of success, and we make different choices to thrive.

In other words, things are different since the baby boomers were young. Getting paid a decent salary and having stability now often requires some education or training beyond high school. For most, thriving in a career means living in a large metropolitan area that offers better job options and a network of talented peers that further your skill set. Millennials also need to invest and save for themselves for retirement.

It’s debatable whether all these changes are positive. But when you consider them as a whole, millennials’ portfolios don’t look so bad. They simply made choices in response to a new economy.

Take the high levels of debt. Millennials have almost twice as much debt as their parents did at their age. But this is mostly student debt, reflecting that they made an investment in their future earnings.

As the economy changes, more education has become necessary for higher pay. According to data from the Federal Reserve Bank, about 69% of millennials had some education beyond high school, compared with 54% of boomers.

True, millennials paid higher tuition than their parents. And the salary premium from going to college has fallen since the 1980s as more people get a degree, making them a little less valuable. There’s also evidence that starting wages are lower and may grow more slowly when you control for education. But that income has become more valuable.

In finance, an asset is worth more when it’s more predictable, and wages are much less variable than they used to be. Before, wages swung around as people changed jobs and worked more hours. But over time, people changed jobs less frequently and worked less. This helps explain why wages have stagnated, because in the past, increases were partly driven by more moving around and less secure positions.

An asset that pays predictable income each year is more valuable than a riskier asset because knowing how much you’ll be paid (or have to pay) each year is desirable, whether you are an investor or a worker. This is why junk bonds cost less than U.S. Treasuries. So when you account for less risk and more stability, a millennial’s reliable $1 wage in 2021 is worth more than an erratic boomer wage in 1991 that might swing from 50 cents to $1.50.

Education has contributed to that stability. The more education you have, the shorter, less frequent periods of unemployment you face. In the new economy we’ve traded risk for stability. It’s debatable if it’s worth the trade-off, but you can’t deny there is value in less risk. And in this new world, investing in yourself (or your education) is often the smartest investment you can make.

It’s also true millennials are less likely to own a home: 48% of 26- to 39-year-olds are homeowners today compared with 52% in 1989, according to Fed data, and home prices are much higher. But that also reflects some reasonable choices. Before the pandemic, at least, higher wages and better skills development were found in large urban areas.

These places also had higher home prices, in part because of demand and also because of policies that limit development. So if you live somewhere you can’t afford to buy a home, it might be because you live somewhere that puts your career on a fast track.

Millennials may have more debt, but they also have more financial assets — about 25% more than their parents did at their age. This is partly because they are more likely to have a retirement account at work, since these savings vehicles are more common than traditional pensions used to be. You could argue traditional pensions were better, but they were also harder to come by: 86% of millennials have some kind retirement plan, compared with 73% of boomers at their age.

The world has changed since the 1980s. Investing in your skills and in financial assets for your retirement may simply make more sense than owning a house because getting ahead requires more education and living in a city. Again, we can debate how much of that change is positive, and whether it’s driven by policy choices, such as restrictions on housing, or just changes in the global economy that put a higher premium on skills learned in school.

Maybe the pandemic will change some of these trends. But you can’t blame or pity millennials for making choices that reflect the economy they live in. Homeownership is overrated anyway.

Updated: 7-30-2021

Inflation And A Slowing Economy Takes Center Stage At Fed Meeting

Paging Dr. Pangloss.

As the Federal Open Market Committee enters day two of its policy, it confronts dual situations that call for diametrically opposite policy reactions. Inflation has risen substantially more than the monetary authorities had expected, which is weighing on consumers and approval ratings for President Joe Biden.

At the same time, the economy’s growth appears to be decelerating as spending on goods slows from its breakneck pace and the new burst of Covid-19 cases related to the Delta variant deters a recovery of spending on services. In particular, the much-anticipated return to the office by the millions still working at home may be pushed back, at least temporarily and perhaps permanently.

With the consumer-price index up 5.4% from a year ago, inflation is top of mind for consumers. As a result, 54% of Americans say the economy is in poor shape, according to a new Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research poll.

The Federal Reserve still pins the price rises on transitory factors, to use the buzzword of the moment. Even so, increased costs are having a negative impact. Sales of new single-family homes fell to a 14-month low in June, the third straight monthly drop, as soaring prices for materials and labor hit both supplies and demand. The median price of a new home was 6.1% more expensive from a year ago, to $361,800.

As this column discussed this past weekend, the Fed is exacerbating home-price inflation with its purchases of $120 billion of securities a month. That consists of $80 billion of Treasuries and $40 billion of mortgage-backed securities. Some would-be home buyers are giving up on the fruitless quest to buy a house as prices soar, the New York Times reported, a spiral made worse by the Fed’s injection of liquidity into the mortgage market.

At the same time, the economy has passed its peak growth and is expected to decelerate significantly from here on to 2022. Goldman Sachs on Monday reduced its GDP forecast, in line with the consensus of economists to 6.6% for the full year of 2021, but to a sharply lower trajectory next year, back to the prepandemic trend rate of just 1.5% to 2%.

That comes as no surprise to David Rosenberg, founder and head of Rosenberg Research, who said recently that the economy looked set to slow dramatically after the burst of consumer spending on durable goods such as automobiles and home appliances and durable goods diminished.

Goldman’s concern is a handoff from goods to services spending will be delayed or thwarted, especially as a slower return to offices continues to keep a lid on workers’ spending for commuting, work clothes and dry cleaning, and food away from home.

Chair Jerome Powell has said all along that Fed policy will depend on the path of the pandemic, which isn’t over, as shown by the upsurge of Covid cases and less than half the population vaccinated, Rosenberg wrote in an email. At the same time, if the FOMC indicates it is moving toward announcing the wind-down of asset purchases, this move to a more accommodative policy could be short-lived, he added.

Rosenberg recalled the Fed shifted to a tightening bias in mid-2008, thinking the worst of the mortgage crisis was over when Bear Stearns was folded into JPMorgan Chase (ticker: JPM) the previous March. Of course, the Fed then had to reverse itself radically by the time the crisis deepened, culminating in the failure of Lehman Brothers and the bailout of American International Group that September.

Nobody is suggesting the Fed is about to raise its key federal funds interest rate target from its current rock-bottom 0-0.25%, however. But the FOMC faces conflicting forces about continuing its massive liquidity injections that were initiated at the height of the pandemic crisis in March 2020 as the economy is passing from its peak growth phase and inflation is causing consternation on Main Street.

Whatever it decides, Powell will have some explaining to do Wednesday at his post-confab press conference.

Updated: 7-3-2022

Millennials Were Optimistic About Their Financial Future—but Now, Not So Much

Many of us haven’t faced the prospects of a prolonged market slump, combined with inflation and recession.

This is a nerve-racking time for me and my friends.

As I’ve written before, many of my millennial peers did pretty well during the pandemic (so well, in fact, that I felt some guilt about it).

We kept our jobs and saved more money, because we had fewer opportunities to spend. Many of my friends also took the opportunity to rethink their lives—changing jobs, getting married, moving to new places—in search of greater fulfillment.

That rosy picture has suddenly changed.

After being lucky enough to ride the longest bull market in U.S. stock-market history, my cohort is now facing the first prolonged market slump to hit our entire generation as adults.

On top of that, surging inflation is diminishing our spending power and general quality of life. And talk of a recession is adding to our fears and eroding the confidence we had in our ability to retire comfortably.

After a couple months of treating my 401(k) balance like a plague, I recently decided to rip the Band-Aid off and take a peek.

Yes, I winced. But truthfully, it wasn’t until I foolishly googled, “How much should you have in your 401(k) by 36?” that I felt the sting of the moment, with a sense of both frustration and futility washing over me.

According to many estimates, I wasn’t close to where I should be—just when it feels like the good times are over.

‘Get It Together’

As a young professional, I thought I had handled my finances relatively well. I had allocated a considerable amount of my paycheck to my employers’ retirement plans and taken advantage of my employer’s contribution match.

I had opened interest-bearing savings accounts and hired a financial planner. This was especially important to me, after watching some of my family members struggle with saving enough for retirement.

The specter of a possible future in which I become part of the 83% of Black Americans who lack sufficient retirement assets wasn’t only looming over me, but was tapping me on the shoulder and whispering, “Get it together.”

On top of that, the anxiety about retirement comes at a time when so many of us, having beefed up our savings during lockdown and motivated by the existential dread of the pandemic, thought we had been afforded the luxury of taking some inspired risks.

Personally, I had been growing increasingly exhausted and annoyed by New York City, and found myself seriously considering, as Beyoncé proclaims in her summer 2020 track “Black Parade,” “goin’ back to the South, where my roots ain’t watered down.”

Would the market slump, along with inflation and my apparent lack of appropriate long-term savings, throw a wrench in my deliberations?

In other words, a year ago, many of us were feeling secure enough to rethink our lives. Now, some of us wonder, is it time to rethink our rethink?

One friend who had left her corporate job—and additional employer contributions to her 401(k)—to work for a nonprofit said she was “TERRIFIED” (her capital letters) when I texted her, asking how she was feeling about her retirement savings.

Similar to me, she had also moved during the pandemic, taking on more rent to live by herself and increasing her housing expenses by more than $500 per month.

“I don’t think I’ll feel better about it until and if I’m able to get a higher-paying job, and then my plan is to save like crazy,” she says. “But I have no idea when that’s going to happen. It’s pretty scary honestly. And knowing that this will be the second major recession I’ve had to live through as an adult makes me feel a little like it’s pointless.”

Another friend who had sought long-term security in homeownership said he felt dejected by “through the freaking roof” housing costs, having been outbid four times in his effort to buy a home.

And some of us, like a friend who works in academia, felt a double burden: Our lagging retirement savings might impede our ability to care for our parents in the future as well.

“My mother wants to retire, but she can’t right now, which is already concerning,” he told me. “And there’s a bit of guilt that I’m not really in a position to help out at this point.”

No Paralysis

All of this threatens to put me and my friends in a difficult place: The pandemic had frozen everything for a while, and now it felt like the bear market and threat of a recession were freezing things once again.

However, I also know paralysis isn’t the answer, and I refuse to put my life on hold a second time. After speaking to some professionals focused on building retirement savings, I learned there are things that people in my situation—determined to keep moving forward financially but not quite sure how—can do to gird ourselves mentally and monetarily for this moment.

Nicole Cope, senior director of wealth advisers at Ally Financial, encourages savers to think of volatility as a feature, not a bug.

That is, if we want to invest in the stock market, it’s just something we have to accept. Many younger investors may be fully taking this in for the first time.

She also suggests we look into other kinds of securities, such as real-estate investment trusts, and focus on bolstering our emergency savings.

In another piece of advice that was a bit hard to swallow, Ms. Cope advised younger retirement savers to contribute more to our 401(k)s during the current slump, effectively buying stock for retirement at what she called a “hyperbolic discount.”

And of course, advisers offer such timeless advice as following a budget and automating investing and saving practices to keep our sights on the long term without being distracted by short-term fears. Apparently, “set it and forget it” has never been more important.

Admittedly, some of these tips feel more like salves than solutions to my anxiety. But that’s only natural: I can’t eliminate uncertainty in my life, but I can reduce it and learn to live with what remains.

If I want to weather the financial storm, I need to act now to create the necessary shelter. It’s a lot more effective than covering my eyes, doing nothing, and hoping that the storm won’t touch me.

Updated: 7-24-2022

China’s Gen Z Is Dejected, Underemployed and Slowing the Economy

Younger workers’ ambitions and salary expectations are diminishing in the wake of Covid and the tech crackdown.

The most educated generation in China’s history was supposed to blaze a trail towards a more innovative and technologically advanced economy. Instead, about 15 million young people are estimated to be jobless, and many are lowering their ambitions.

A perfect storm of factors has propelled unemployment among 16- to 24-year-old urbanites to a record 19.3%, more than twice the comparable rate in the US.

The government’s hardline coronavirus strategy has led to layoffs, while its regulatory crackdown on real estate and education companies has hit the private sector.

At the same time, a record number of college and vocational school graduates—some 12 million—are entering the job market this summer. This highly educated cohort has intensified a mismatch between available roles and jobseekers’ expectations.

The result is an increasingly disillusioned young population losing faith in private companies and willing to accept lower pay in the state sector. If the trend continues, growth in the world’s second-largest economy stands to suffer.

The sheer number of jobless under-25s amounts to a 2% to 3% reduction in China’s workforce, and fewer workers means lower gross domestic product.

Unemployment and underemployment also continue to impact salaries for years—a 2020 review of studies reported a 3.5% reduction in wages among those who had experienced unemployment five years earlier.

More young people taking roles in government may leave fewer jumping into new sectors and fueling innovation.

“The structural adjustment faced by China’s economy right now actually needs more people to become entrepreneurs and strive,” said Zeng Xiangquan, head of the China Institute for Employment Research in Beijing. Lowered expectations have “damaged the utilization of the young labor force,” he added. “It’s not a good thing for the economy.”

Pre-pandemic, 22-year-old Xu Chaoqun was prepared for a career in China’s creative industries. But a fruitless four-month job hunt has left him setting his sights on the state sector.

“Under the Covid outbreak, many private companies are very unstable,” said Xu, who majored in visual art at a mid-ranked university. “That’s why I want to be with a state-owned enterprise”.

Xu is not alone. Some 39% of graduates listed state-owned companies as their top choice of employer last year, according to recruitment company 51job Inc. That’s up from 25% in 2017. A further 28% chose government jobs as their first choice.

It’s a rational response in a pandemic-hit labor market. All workplaces have been hit hard by China’s snap lockdowns and strict quarantine measures, but private companies were more likely to lay off workers.

Beijing’s main employment-boosting policy has been to order the state sector to increase hiring.

President Xi Jinping may be relieved that the country’s unemployed youth are trying to join the government rather than overthrow it. During a June visit to a university in the southwestern China’s Sichuan province, he advised graduates to “prevent the situation in which one is unfit for a higher position but unwilling to take a lower one.”

He added that “to get rich and get fame overnight is not realistic.”

The message is getting through: Graduate expectations for starting salaries fell more than 6% from last year to 6,295 yuan ($932) per month, according to an April survey from recruitment firm Zhilian. State-owned enterprises grew in appeal over the same period, the recruiter said.

But lower income expectations and talent shunning the private sector are likely to lower growth in the long term, challenging the president’s plan to double the size of China’s economy from 2020 levels by 2035—by which point it would likely overtake the U.S. in size.

The phrase “tang ping”—“lying flat”—spread through China’s internet last year. The slogan invokes dropping out of the rat race and doing the bare minimum to get by, and reflected the desire for a better work-life balance in the face of China’s slowing growth.

As the unemployment situation has continued to worsen, many young people have adopted an even more fatalistic catchphrase: “bailan,” or “let it rot.”

That concept is “a kind of mental relaxation,” said Hu Xiaoyue, a 24-year old with a psychology masters degree. “This way, even if you fail, you will feel better.”

When Hu started looking for work last August, she found it easy to land interviews. “But when it came to spring, only one in 10 companies would offer an interview,” she said. “It fell off a cliff.”

China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs) aren’t all unproductive behemoths. But the weight of economic evidence suggests they are, on the whole, less efficient and less innovative than privately-owned companies.

China’s economic boom has coincided with a falling share of SOE jobs in urban employment—from 40% in 1996 to less than 10% pre-pandemic. That trend could now go into reverse.

Last year, China launched a regulatory crackdown on formerly high-flying sectors dominated by private companies that previously attracted ambitious young people.

Internet companies were hit with fines for monopolistic behavior, real estate businesses were starved of financing and the private tutoring sector was almost entirely shuttered.

Regulatory filings show that China’s top five listed education companies reduced their staffing by 135,000 in the last year after the crackdown.

The largest tech companies have kept their headcounts stable, and Zhilian says that there were more tech jobs advertised in the first half of this year than the same period in 2021. Even so, the sector’s allure has faded.

A graduate of the highly ranked Central University of Finance and Economics in Beijing, Hu was set for the tech sector—she interned at three internet companies including video-sharing giant Beijing Kuaishou Technology Co.

But she has changed her mind. “People who are going to work for Internet companies are all worrying about themselves because they feel like they could be fired any time,” she said.

Instead, Hu landed a position at a research institute within state-owned China Telecom Corp. “The working hours of my future job will be 8:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., and the workload will be quite light. Internet companies are too consuming,” she said.

As well as the movement of talent towards state-owned companies, there’s another mechanism at work that can damage long-term growth.

Studies from the US, Europe and Japan have shown that the longer young people are unemployed at the start of their careers, the worse their long-term incomes, an effect known as “scarring.”

That’s the risk facing Beiya, who was laid off from an e-commerce company this year. The 26-year-old, who gave only one name because she feared that talking about losing her job could hit her employment prospects, missed out on a role with TikTok parent company Bytedance Inc. because of her limited experience.

“I’m a good candidate with potential but they want to see me in two years,” she said. “But how can I get the experience if no one gives me a job now?”

The state sector already employs around 80 million people and the figure could grow by as much as 2 million on a net basis this year, according to Lu Feng, a labor economist at Peking University.

“But compared with total demand for jobs, it’s still relatively small,” he said. “We still need private firms to hire.”

That will only happen if the economy grows. To meet its employment goals, economists say China needs GDP to increase between 3% and 5% this year.

Economists are predicting growth closer to 4%—with the outlook highly uncertain due to the prospect of more lockdowns to contain the spread of the coronavirus.

“Lack of clarity on an exit strategy from the Covid-Zero policy makes companies wary of hiring,” said Chang Shu, Bloomberg Economics’ chief Asia economist.

Beijing has launched a version of the job-support programs seen in Europe during the pandemic, offering tax rebates and direct subsidies to companies who promise to retain workers.

But the amounts involved are small: The incentive for hiring a new worker is just 1,500 yuan. Provincial subsidies for graduates who start businesses are also small—just 10,000 yuan in the prosperous Guangdong region.

Even if China can return to strong growth in the second half of this year, the youth unemployment problem will persist—the rate has been rising since 2017, reaching 12% pre-pandemic.

Economists attribute that to two factors: urbanization and a mismatch between the education system and employers’ needs.

The hundreds of millions of workers who moved from the countryside to cities used to return to their villages during labor market slumps, acting as an economic shock absorber. Now, younger migrants increasingly stay put when they lose their jobs, pushing up urban unemployment.

“A lot of them are not even raised in rural areas. So they regard themselves as urban people,” says Peking University’s Lu. “The constraints for the government have changed substantially, it’s tougher than in the past.”

Second, the annual number of graduates in China has increased tenfold over the last two decades—the fastest higher-education expansion anywhere in the world, at any time. The share of young Chinese people attending college is now almost 60%, similar to developed countries.

The number of vocational graduates lags far behind those receiving academic degrees. Such is the stigma around vocational education that students rioted last year when told their university was being rebranded as a vocational school.

Highly educated young people are rejecting factory jobs. “That’s the basic matching problem. It is huge in this country,” said Lu.

That’s left manufacturers complaining about shortages of skilled technicians. “There are not a lot of people applying for those jobs, such as electrician or welder,” said Jiang Cheng, 28, an agent for electronics factories in central China.

Other sectors are oversubscribed. According to a 2021 study of 20,000 randomly selected jobseekers on Zhilian’s website, some 43% of the job applicants wanted to work in the IT industry, while the sector accounted for just 16% of recruitment posts.

Half of jobseekers had a bachelor degree, but only 20% of jobs required one. “There is now compelling evidence of over-education,” the study’s authors wrote, warning that the misalignment “could have profound influences on both individuals and the nation.”

In the longer term, it’s possible that government intervention may get the private sector hiring again, while education reforms and market forces can smooth the misalignment in the labor market.

China is easing its regulatory campaigns, and a vocational education law passed this year aims to improve standards. A study by Wang Zhe, an economist at Caixin Insight, found college majors that attracted a wage premium in 2020 became more popular in 2021. As applicants’ academic choices adapt to demand in the jobs market, mismatches stand to ease.

But the share of graduates from China’s nine top-ranked universities joining the private sector has fallen since the pandemic, according to research from Hong Kong’s Lingnan University.

That suggests ideological shifts, and not just market forces, are at play. Some graduates at top universities are adopting “ cadre style,” according to online forums where they seek tips on where to buy the black zippered windbreakers favored by Xi.

Even in the current environment, Kay Lou, 25, would be a leading candidate for any number of private-sector jobs. She has a masters in law from top-ranked Tsinghua University and has interned for a legal firm, an Internet giant, a securities brokerage and a court.

In the end, she won a government position in Zhejiang province—where some roles attract as many as 200 applicants.

“I felt my work wasn’t meaningful,” she said. “I became increasingly opposed to the capitalists’ pursuit of wealth after I read Marx, so in the end I chose to become a civil servant.”

Updated: 7-25-2022

Gen Z Thinks ‘The Money Will Come Back.’ Will It?

Despite the TikTok trend, you don’t have only two choices about money in your 20s — either be super-frugal or YOLO. In reality, you can do both.

Our current crop of 20-somethings — the majority of whom are Generation Z — have apparently caught on to the time-honored tradition of “living it up” while young and not worrying about money.

A social-media trend that’s recently taken over TikTok features people sharing video or photos from traveling abroad with the overlaying text: “I’ll make my money back, but I’ll never …” The blank at the end goes something like “… be 20 and swimming on a secluded beach in Albania again.”

This sentiment seems to creep up on every generation. (In 2015, it took the form of a viral article, “If You Have Savings in Your 20s, You’re Doing Something Wrong.”) The problem is, it’s misguided.

It is a myth that you have only two choices about money in your 20s — that you’re either completely locked down, frugal and saving for your future, or you’re YOLO-ing your way through life, racking up priceless experiences (and probably debt) and planning to become more financially prudent later on.

In reality, you can save for your future and be swimming in the waters of Albania or eating pie on a train through the Swiss Alps. (Or, depending on your particular financial situation, your “YOLO-ing” may be more cost-effective.)

You just have to think strategically about your money and your ambitions — i.e., set goals and stick to a budget that will allow you to meet them.

Taking stock of your cash flow and creating a spending plan can help you avoid volatile financial swings between always splurging or always saving. Instead, you can set yourself up for a life of stability and choice.

One important truth of the TikTok trend is “I’ll make the money back.” It’s true that many people will see raises and promotions over the course of their careers. But it’s also worth remembering that life doesn’t tend to get less expensive as you age.

Your expenses usually grow, too — your future self might want to buy a home, rescue a few dogs, have a wedding, take lavish trips, buy nicer clothes and food, have a child or two, maybe take a sabbatical from work. And it becomes more likely that you’ll experience a health crisis or need to financially support a loved one.

Overspending early in life can set a precedent that you won’t necessarily be able to maintain without financially harming yourself in the future.

Take one example: having children. A favorite line from one of my husband’s coworkers, who is married, child-free and in his 50s, is: If you don’t have kids, your 30s are your 20s, but with money.

Expanding a family is a huge expense, especially in the US, which has seen an increase in the maternal mortality rate, offers no mandated paid leave after childbirth, and offers heinously expensive child-care options for working parents.

This doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t be living it up in your 20s. You can still go on adventures and live a full life while working to build a strong financial base.

That just might mean making day-to-day financial choices that allow you to set money aside for your future goals or opting for a cost-effective version of your dream today instead of the all-out luxury one that will strain your savings.

The key is to be intentional. If you want the freedom to take a two-week vacation to the No. 1 destination on your bucket list, put money aside for it. That should be part of your spending plan (aka budget).

If you’re able to, set money aside each month for a trip on top of also putting money toward repaying any debt, building an emergency savings fund and investing in a retirement plan.

Here’s how this works in practice: Start with a list of your necessary monthly costs (rent, utilities, transportation, groceries, dog food, student loan payments, etc.). Write down your monthly net income and subtract your monthly costs.

You should be contributing to your retirement plan before money hits your checking account, so it checks one item off the to-do list already. In an ideal situation, your income is more than your necessary expenses.

Assuming a surplus, you can decide exactly where you want to direct that money each month after hitting your baseline needs.

This can include saving up for your next adventure and a line-item in your budget for dinners out or seeing shows. It can include whatever you want it to — but the point is to stay within your means.

Will you be able to do absolutely everything or buy whatever you want all the time? No. But keeping track can help you set priorities and make sacrifices that you won’t regret later.

Such planning allowed me to travel internationally in my 20s while also saving and investing and helping my husband pay off student loans.

It also helped that I had side hustles the entire time and directed that income toward my “fun goals.” There’s no need to delay “the money will come back.”

It’s easy to fixate on the binary of frugality vs. living it up. But it’s far more rewarding to discern what you actually find important. We are constantly bombarded with messaging about what we should value and strive for, but much of it is marketing and social pressure. (Does swimming on a secluded beach in Albania even sound appealing to you?

Maybe travel isn’t your thing and you’d rather put more money toward a hobby.) Focusing on your values will illuminate how you should be spending, saving and investing your money. Say no to what you don’t want, and budget in what’s important.

The future isn’t promised, so yes, please create some memories and live life as you go. But financially hedge your bets, just in case you do live to a ripe old age.

Updated: 7-26-2022

Elder Millennials Have Less Time for Fun

A new report on how Americans spend their days shows 35- to 44-year-olds have fewer leisure hours than anybody else, and less than two decades ago.

Along with some less-welcome changes, the Covid-19 pandemic brought many Americans a respite from time pressures. Average time spent sleeping went up by about 10 minutes a day in 2020, and time devoted to leisure and sports activities went up by about 32 minutes, according to the American Time Use Survey conducted by the Census Bureau on behalf of US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

There are some comparability issues here because the 2020 survey was interrupted by the onset of the pandemic. There are seasonal differences in leisure activity and the BLS ended up publishing only the results from May through December. But they’re not big issues: