30% Of All Mortgages Will Default In “Biggest Wave Of Delinquencies In History”

Unlike in the 2008 financial crisis when a glut of subprime debt, layered with trillions in CDOs and CDO squareds, sent home prices to stratospheric levels before everything crashed scarring an entire generation of homebuyers. 30% Of All Mortgages Will Default In “Biggest Wave Of Delinquencies In History”

This time the housing sector is facing a far more conventional problem: the sudden and unpredictable inability of mortgage borrowers to make their scheduled monthly payments as the entire economy grinds to a halt due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Related:

Retail Store And U.S. Household Evictions Skyrocket Due To Missed Payments

And unfortunately this time the crisis will be far worse, because as Bloomberg reports mortgage lenders are preparing for the biggest wave of delinquencies in history. And unless the plan to buy time works – and as we reported earlier there is a distinct possibility the Treasury’s plan to provide much needed liquidity to America’s small businesses may be on the verge of collapse – an even worse crisis may be coming: mass foreclosures and mortgage market mayhem.

Borrowers who lost income from the coronavirus, which is already a skyrocketing number as the 10 million new jobless claims in the past two weeks attests, can ask to skip payments for as many as 180 days at a time on federally backed mortgages, and avoid penalties and a hit to their credit scores. But as Bloomberg notes, it’s not a payment holiday and eventually homeowners they’ll have to make it all up.

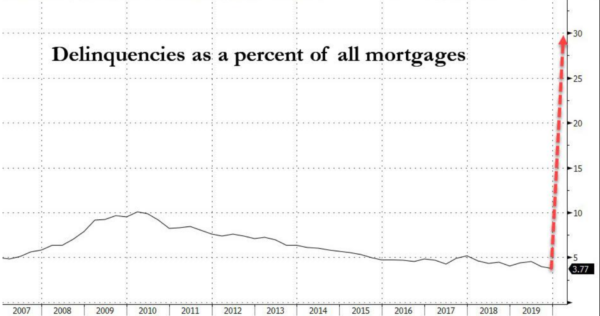

According to estimates by Moody’s Analytics chief economist Mark Zandi, as many as 30% of Americans with home loans – about 15 million households – could stop paying if the U.S. economy remains closed through the summer or beyond.

“This is an unprecedented event,” said Susan Wachter, professor of real estate and finance at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. She also points out another way the current crisis is different from the 2008 GFC: “The great financial crisis happened over a number of years. This is happening in a matter of months – a matter of weeks.”

Meanwhile lenders – like everyone else – are operating in the dark, with no way of predicting the scope or duration of the pandemic or the damage it will wreak on the economy. If the virus recedes soon and the economy roars back to life, then the plan will help borrowers get back on track quickly. But the greater the fallout, the harder and more expensive it will be to stave off repossessions.

“Nobody has any sense of how long this might last,” said Andrew Jakabovics, a former Department of Housing and Urban Development senior policy adviser who is now at Enterprise Community Partners, a nonprofit affordable housing group. “The forbearance program allows everybody to press pause on their current circumstances and take a deep breath. Then we can look at what the world might look like in six or 12 months from now and plan for that.”

But if the economic turmoil is long-lasting, the government will have to find a way to prevent foreclosures – which could mean forgiving some debt, said Tendayi Kapfidze, Chief Economist at LendingTree. And with the government now stuck in “bailout everyone mode”, the risk of allowing foreclosures to spiral is just too great because it would damage financial markets and that could reinfect the economy, he explained.

“I expect policy makers to do whatever they can to hold the line on a financial crisis,” Kapfidze said hinting at just a trace of a conflict of interest as his firm may well be next to fold if its borrowers declare a payment moratorium. “And that means preventing foreclosures by any means necessary.”

Take for example Laura Habberstad, a bar manager in Washington, D.C., who got a reprieve from her lender but needs time to catch up. The coronavirus snatched away her income, as it has for millions, and replaced it with uncertainty. The restaurant and beer garden where she works was forced to temporarily shut down. Laura has no idea when she’ll get her job back, nor does she have any idea how to look for a new job. After all, how do you search for another hospitality job during a global pandemic? Now she’s living in Oregon with her mother, whose travel agency was also forced to close.

“I don’t know how I’m going to pay my mortgage and my condo dues and still be able to feed myself,” Habberstad said. “I just hope that, once things open up again, we who are impacted by Covid-19 are given consideration and sufficient time to bring all payments current without penalty and in a manner that does not bring us even more financial hardship.”

Borrowers must contact their lenders to get help and avoid black marks on their credit reports, according to provisions in the stimulus package passed by Congress last week. Bank of America said it has so far allowed 50,000 mortgage customers to defer payments. That includes loans that are not federally backed, so they aren’t covered by the government’s program.

Meanwhile, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin has convened a task force to deal with the potential liquidity shortfall faced by mortgage servicers, which collect payments and are required to compensate bondholders even if homeowners miss them. The group was supposed to make recommendations by March 30.

“If a large percentage of the servicing book – let’s say 20-30% of clients you take care of – don’t have the ability to make a payment for six months, most servicers will not have the capital needed to cover those payments,” QuickenChief Executive Officer Jay Farner said in an interview. But not Quicken, of course.

Quicken, which serves 1.8 million borrowers, and in 2018 surpassed Wells Fargo as the #1 mortgage lender in the US, has a strong enough balance sheet to serve its borrowers while paying holders of bonds backed by its mortgages, Farner said, although something tells us that in 6-8 weeks his view will change dramatically. Until then, the company plans to almost triple its call center workers by May to field the expected onslaught of borrowers seeking support, he said.

Ironically, as Bloomberg concludes, “if the pandemic has taught us anything, it’s how quickly everything can change. Just weeks ago, mortgage lenders were predicting the biggest spring in years for home sales and mortgage refinances.”

Habberstad, the bar manager, was staffing up for big crowds at the beer garden, which is across from National Park, home of the World Series champions. Then came coronavirus. Now, she’s dependent on her unemployment check of $440 a week.

“For us, it was a no-brainer,” he said. “It’s worth the follow-through.”

Updated: 8-11-2020

Commercial Properties’ Ability To Repay Mortgages Was Overstated, Study Finds

Many borrowers are now struggling because of coronavirus, though study finds income often fell short of underwritten amount before the pandemic.

Thousands of commercial-mortgage borrowers have been struggling to meet payments on their loans in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic. But there might be another reason so many are falling behind: aggressive lending practices that overstated borrowers’ ability to repay.

A study of $650 billion of commercial mortgages originated from 2013 to 2019 found that even during normal economic times, the mortgaged properties’ net income often falls short of the amount underwritten by lenders. The underwritten amount should be a conservative estimate of how much a property earns. Instead, the actual net income trails underwritten net income by 5% or more in 28% of the loans, according to the study of nearly 40,000 loans by two finance academics at the University of Texas at Austin.

The study shows risks in the $1.4 trillion market for commercial mortgage-backed securities, or CMBS, where loans on malls, apartment buildings, hotels and the like get packaged into bonds bought by investors, often with guarantees from the government. The findings suggest that loans sold to investors before the pandemic frequently featured overstated income and could have more trouble staying current in case of a downturn.

The findings corroborate a complaint received last year by the Securities and Exchange Commission stating that commercial mortgage loans frequently feature inflated financials. They also come at a sensitive time for the commercial-mortgage-backed securities industry, which has been seeking a lifeline since the spring, when the Federal Reserve left out swaths of the market from its $2.3 trillion economic-rescue package.

Congressional legislation introduced last month is seeking to help the industry survive the pandemic, which has sent commercial loan delinquencies to near-record highs.

John Griffin, a finance professor and co-author on the study, says his findings provide evidence that the commercial-mortgage industry is at least partly to blame. He found that when the pandemic hit, loans with inflated income were quicker to enter watch lists for troubled loans maintained by loan servicers. Income was overstated by more than 5% in more than 40% of loans originated by UBS, UBS 0.33% Starwood Property Trust STWD 2.56% and Goldman Sachs Inc., GS 0.77% the study said. Loans from these originators were among those most likely to be on a watch list, Mr. Griffin found.

“This is a direct function of the aggressive underwriting,” Mr. Griffin said. He disclosed in his paper that he owns a fraud-consulting firm, Integra FEC LLC, which could benefit if the government or investors acted against the bond issuers.

UBS and Goldman Sachs declined to comment. Starwood said it has “consistently experienced strong performance across its portfolio of originated loans.” The Commercial Real Estate Finance Council, which represents the industry, called Mr. Griffin’s study flawed and said the industry’s record on underwriting was solid.

The organization’s chairman, Adam Behlman, said the study should have used long-term cash flow to judge the underwriting and said the originators identified in the study had lower-than-average default rates on their loans. “Defaults are the ultimate barometer of the quality of the underwriting,” Mr. Behlman, a Starwood executive, said.

The expected income generated by a property is an important factor in how much the owner can borrow. The bigger a property’s net income, the bigger the value and thus the loan it can support. Shaving a few hundred thousand of expenses or claiming additional income can add millions to a loan’s size, which can benefit borrowers by giving them room to cash out equity from properties. Higher net income also makes loans worth more, enabling more profit for originators.

Mr. Griffin’s study doesn’t definitively answer the question of who might be inflating loan financials. But it does provide evidence that the industry is aware of the practice. Mr. Griffin found that loan originators charged higher interest rates for loans with overstated income, suggesting they viewed them as riskier. Kroll Bond Rating Agency Inc. and DBRS Morningstar, two rating firms that grade CMBS bonds, also tended to treat inflated loans more skeptically in their rating models, the study found.

Kroll declined to comment. DBRS Morningstar said that analyzing loans’ cash flows is a key element of its rating process and that it consistently applies its criteria when grading deals.

Borrowers, lenders and their representatives have a lot of leeway in calculating a property’s earning power. Unforeseen circumstances such as a natural disaster can also take a bite out of expected income after a loan is originated. Sometimes, however, fraud can play a role, too, according to federal prosecutors.

In 2019, the SEC and the Justice Department each filed fraud cases against Robert Morgan, who had borrowed about $3 billion to amass a multifamily property empire that once spanned more than 34,000 units across 14 states. Prosecutors alleged that Mr. Morgan conspired to create fictitious leases at some of his properties to make their income look bigger than it was. The SEC alleged that he ran a Ponzi-scheme-like scam that used investors’ money to “repay an inflated, fraudulently obtained loan” on one of his properties.

A lawyer for Mr. Morgan said he is “vigorously defending against the criminal charges.” The SEC, which recently disclosed that it has reached a tentative settlement with Mr. Morgan, declined to comment.

The SEC has been aware of potential income inflation in CMBS loans since at least February 2019, when it received a complaint about the issue. The complaint, earlier reported by ProPublica, pointed to a pattern of inconsistent figures in different financial reports providing income for the same property in a previous year.

Mr. Griffin’s study validates inconsistencies in such overlapping reports. In a subsample of 2,172 loans, Mr. Griffin found that 70% of loans exhibiting income inflation of 5% or more in the first year of the CMBS deal also overstated properties’ historical financials.

The SEC declined to comment on the complaint. John Flynn, a CMBS industry veteran who filed the complaint, said that after poring over thousands of loans, he feels relieved to see someone else spot the same pattern.

“It’s much more widespread than I even realized,” Mr. Flynn said.

“Everybody wants to work but we’re being asked not to for the sake of the greater good,” she said.

Updated: 8-17-2020

FHA Mortgage Delinquencies Reach A Record

Federal Housing Administration mortgages — the affordable path to homeownership for many first-time buyers, minorities and low-income Americans — now have the highest delinquency rate in at least four decades.

The share of late FHA loans rose to almost 16% in the second quarter, up from about 9.7% in the previous three months and the highest level in records dating back to 1979, the Mortgage Bankers Association said Monday. The delinquency rate for conventional loans, by comparison, was 6.7%.

Millions of Americans stopped paying their mortgages after losing jobs in the coronavirus crisis. Those on the lower end of the income scale are most likely to have FHA loans, which allow borrowers with shaky credit to buy homes with small down payments.

For now, most of them are protected from foreclosure by the federal forbearance program, in which borrowers with pandemic-related hardships can delay payments for as much as a year without penalty. As of Aug. 9, about 3.6 million homeowners were in forbearance, representing 7.2% of loans, the MBA said in a separate report. The share has decreased for nine straight weeks.

Housing has held up better than expected in an otherwise shaky economy, with record-low mortgage rates fueling sales of both new and previously owned houses. With job losses mounting and Congress slow to act on a fresh stimulus package, that momentum could be threatened.

New Jersey had the highest FHA delinquency rate, at 20%. The state also had the biggest increase in the overall late-payment rate, jumping to 11% in the second quarter from 4.7%. Following were Nevada, New York, Florida and Hawaii — all states with a high proportion of leisure and hospitality jobs that were especially hard-hit by the pandemic, the MBA said.

But the current spike in delinquencies is different from the Great Recession, thanks in part to years of home-price gains and equity accumulation, according to Marina Walsh, vice president of industry analysis for the bankers group.

Updated: 9-17-2020

A Million Mortgage Borrowers Fall Through Covid-19 Safety Net

Some homeowners don’t know they qualify for a relief program that allows them to delay payments.

About one million homeowners have fallen through the safety net Congress set up early in the coronavirus pandemic to protect borrowers from losing their homes, according to industry data, potentially leaving them vulnerable to foreclosure and eviction.

Homeowners with federally guaranteed mortgages can skip monthly payments for up to a year without penalty and make them up later. They must call their mortgage company to ask for the relief, known as forbearance, though they aren’t required to prove hardship.

Many people have instead fallen behind on their payments, digging themselves into a deepening financial hole through accumulated missed payments and late fees. They could be at risk of losing their homes once national and local restrictions on evictions and foreclosures expire as early as January.

“Some borrowers are falling through the cracks that we’re not picking up,” said Lisa Rice, president and chief executive of the National Fair Housing Alliance. “It’s just a really sad series of events.”

About 1.06 million borrowers are past due by at least 30 days on their mortgages and not in a forbearance program, according to mortgage-data firm Black Knight Inc. Of those, some 680,000 have federally guaranteed mortgages and thus qualify for a forbearance plan under a March law. The rest have loans that aren’t federally guaranteed, and their lenders aren’t required to offer forbearance, though many have chosen to do so.

“Borrowers who are eligible to be in forbearance will preserve their options to avoid foreclosure, versus those who became delinquent and have accumulated penalties and interest in a march toward foreclosure,” said Faith Schwartz, president of Housing Finance Strategies, an advisory firm.

Lenders and consumer groups said the number of past-due mortgages that aren’t in forbearance could grow as several million people who are in forbearance reach the six-month point of their plans by the end of October. An extension of up to six months is possible, but homeowners must ask for it. Lenders said they are reaching out to these borrowers before their forbearance periods expire.

Some 250,000 of the six million borrowers who were in forbearance at one point since the pandemic began are again delinquent on their homes, according to Black Knight.

The borrowers who are falling through the forbearance safety net represent a small portion of the roughly 53 million active mortgages in the U.S. Lenders and consumer groups said these consumers tend to be among the more financially vulnerable, with lower incomes and weaker credit scores.

A recent survey of the National Housing Resource Center found that 56.6% of respondents didn’t know about the forbearance program. An even larger share of consumers were confused about their options, including 69.9% who said they feared being required to make a large lump-sum payment at the end of the forbearance period.

A group of consumer advocates and housing-policy experts have discussed starting a national ad campaign to educate borrowers about their options, but the effort is in the early stages. A group of government agencies have set up a website designed to educate borrowers about their alternatives, but consumer groups said more work is needed to reach at-risk borrowers. Lenders that collect mortgage payments said they have boosted their outreach to borrowers.

“Servicers are absolutely reaching out to borrowers who are delinquent and not already in forbearance,” said Pete Mills, a senior vice president at the Mortgage Bankers Association. “For borrowers who haven’t called or are avoiding talking to their servicer, it’s important that they connect with them in order to understand their forbearance options.”

Sue Stevenson, a mortgage-default counselor near Seattle, said homeowners have had trouble getting through to mortgage-service companies on the phone. Calls are often sent to voice mail and not returned, she said. Other times, calls are answered but dropped. Borrowers must then call again and endure yet another lengthy hold period.

Compounding the problems, Ms. Stevenson said, representatives responding to questions read from jargon-laden scripts that can confuse or scare borrowers. For instance, the first option most borrowers are given to make up missed payments is to pay a lump sum at the conclusion of the forbearance period.

“Representatives are restricted in what they are allowed to say, leading to misunderstandings because it’s not in layman’s terms, so it can just be so confusing,” she said.

The Mortgage Bankers Association and lenders said requests for forbearance as well as call hold times are both down significantly since the beginning of the pandemic. Meanwhile, most borrowers who have needed assistance since the crisis began have been able to enter forbearance plans and are now beginning to exit their plans or seek extensions.

Some borrowers said the process is still confusing.

Susan Mclaren Shiflett got a forbearance this summer after her work hours were cut at a retailer in Wenatchee, Wash. But she was thrown for a loop when her servicer, Guild Mortgage Co., still sent her warnings that she was past due on her mortgage and that she was at risk of foreclosure.

She said a company representative told her the letters were required by law. Even so, she said: “It’s just scary every time they send a letter of being delinquent. I’m doing everything I’m supposed to do.”

In a statement, Guild said it “recognizes the impact and confusion of these notices going to the borrower and is committed to educating customers about their purpose.”

Updated: 9-21-2020

Commercial Closures Are Causing A Ripple Effect Impacting The Residential Sector

The departure of building-anchoring retail can erode rent premiums and increase the costs for some homeowners.

When the coronavirus pandemic seized the U.S., Allen Morris had a plan for Maitland City Centre, a 220-apartment community with a 35,000-square-foot commercial space that claims a whole city block in Maitland, near Orlando, Florida. Mr. Morris, who helms the eponymous development company, would not seek rent from the Centre’s restaurants, which included a gelato shop and several concept eateries, if they stayed operational during Covid-19.

“We took the initiative to go to our restaurant tenants on the ground floor,” Mr. Morris said. “And we said, ‘Look, don’t worry about paying your rent. Just, you must stay open, you must promise us to stay in business because it’s so beneficial to the leasing of our apartments.”

In a time when urban developments across the U.S. are bleeding renters to the suburbs, Maitland City Centre boasts a 94% residential occupancy rate, Mr. Morris said. To a large extent, he attributes that to the presence of commercial tenants, especially food and beverage establishments that have provided convenient dining and takeout options for residents amid the pandemic.

“I believe that the commercial elements and the residential elements in a mixed-use project are entirely symbiotic,” Mr. Morris said. “They benefit one another and create a synergism in a mixed-use project that you don’t get in a standalone building.”

That mutual advantage, however, seems to have somewhat eroded during the pandemic, which has triggered the bankruptcies of major retailers in the caliber of Neiman Marcus, which was to have occupied New York City’s Hudson Yards on Manhattan’s far West Side. The volatile economy is also threatening numerous small businesses and experiential retail, which struggled to stay afloat during the nationwide shutdowns this spring.

According to commercial real estate data provider CoStar, so far this year, retailers have laid out plans to shutter 130 million square feet of stores in the U.S., a record driven by the disruption of foot traffic and the acceleration of e-commerce caused by coronavirus. Most commercial closures will affect malls, CoStar said, but residential buildings that also house retail are not immune. The typical commercial occupants— think restaurants and gyms that help foster a community for renters and homeowners—are in industries battered by the pandemic.

Not all major cities, however, are seeing these woes play out equally. While big retailers are closing stores across the nation, some cities like Seattle—which has a relatively low unemployment rate and was able to get the virus under control early on—have been recovering faster than others, propping up small businesses that rely on foot traffic. Moreover, not all metros attract mixed-use developments, which tend to favor dense urban pockets, where residents both work and live.

“Commercial tenancies have a much larger impact on residential buildings in real urban centers like San Francisco or New York or Washington DC or Chicago,” said Scott Gordon, senior vice president for Kennedy Wilson’s property services division in Los Angeles. “There, a very significant retail and dining presence on the lower floors has a much greater economic impact than perhaps in Los Angeles, which is obviously a lot more spread out.”

Renter Woes

Commercial troubles in mixed-use developments usually undermine residential rent prices.

“If you have failed retail tenants in your mixed-use building, it makes the other components of the mixed-use building less desirable because those previous amenities are not there anymore,” Mr. Morris said. “That would tend to put downward pressure on the residential rents or the concessions or the terms that the landlord is getting to the multifamily apartments.”

That pressure can erode the residential rent premium that mixed-use developments often carry compared to the overall market. Depending on the location and the mixture of retail, the premium can be as high as 20%, studies show.

For instance, a Whole Foods supermarket alone can pump up rents by as much as 8.4%, according to a 2019 report by Newmark Knight Frank that analyzed the rent effects of seven grocers in Washington, D.C., Virginia and Maryland. And, this is for apartments located within a mile of the grocer. Units directly above a Whole Foods see even more pronounced prices, the report authors say. For mixed-use developments, retail-anchoring grocers contribute the highest rent premiums.

“Some people just like the convenience of being able to go to the grocery store and not have to step out or being able to run down if they forgot something for dinner,” said Lindsey Senn, executive vice president of finance and development with Chicago-headquartered real estate company Fifield. “Because of that, the loss of a grocer makes much more of an impact than, say, a restaurant closing when there’s another restaurant that’s down the block.”

Taking it a step further, the absence of a business, signaled by dark and boarded-up windows, might give scores of potential residential tenants a pause.

“When you are leasing an apartment, you are selling an experience,” said Mr. Gordon. “When you have an empty commercial space, it is about perception.”

Because of this, developers are now more scrupulous about the commercial tenants they sign on. Before the coronavirus outbreak, developer Joseph Kavana, chairman and CEO of Sunrise, Florida-based K Group Holdings, had been in talks with multiple restaurants he considered bringing to Metropica, a $1.5 billion, 65-acre community under construction in Broward County near Fort Lauderdale. The pandemic has changed the conversations.

“We have had discussions with a lot of different restaurant groups,” Mr. Kavana said. During the pandemic, “some of them have done better than others. Frankly, at this point, we believe that the best approach is to take a breathing moment and wait and see what develops after this.”

Despite the pandemic, Mr. Kavana hasn’t scrapped his intention to have eateries as well as offices in Metropica, banking on the idea that people will eventually return to both.

NYC Co-ops Can See A Direct Hit

One segment where shuttered retail has easy-to-measure financial implications for residential occupants is the New York City co-op market. When co-op buildings lease their ground floors to businesses, the generated revenue helps defray the monthly fees for the residential owners.

Earlier this year, Warburg real estate agent Christopher Totaro worked with the buyer of a 2,500-square-foot home in an eight-unit co-op in downtown Manhattan. The monthly co-op fee was about $1,000. Then, in April, before Totaro’s client purchased the unit, the business downstairs, an upscale furniture design shop that paid roughly $1 million in annual rent, moved out for a reason unrelated to the coronavirus. The departure pushed the co-op fee to $3,000, Mr. Totaro said.

“If you’ve got a business such as a restaurant that is shut down because of Covid or is not paying rent, the people that live upstairs may be paying to carry that restaurant through these times,” Mr. Totaro said.

Co-ops without hefty reserves to continue paying their mortgage and maintenance in the absence of commercial rent might have little choice but to increase their owners’ fees. After some consideration, Mr. Totaro’s client went through with the purchase.

“People, I think, don’t understand the magnitude of the ripple effect” of underperforming retail, Mr. Totaro said.

Updated: 9-22-2020

Blackstone Ready To Lend After Raising Record Property Debt Fund

Investment firm raises $8 billion as falling rates help increase appeal of relatively high-yielding real estate debt.

Blackstone Group Inc. closed this month on the largest real-estate debt fund ever, giving the investment firm plenty of cash to lend to property investors looking to go shopping during the coronavirus pandemic.

One of the world’s largest owners of commercial property, Blackstone began raising money for the fund in the spring of 2019 and the $8 billion it took in exceeded expectations, said Jonathan Pollack, global head of Blackstone Real Estate Debt Strategies. Fundraising got a boost after Covid-19, partly because interest rates fell, increasing the appeal of relatively high-yielding real estate debt.

“There’s an expectation that there will be a greater opportunity in real estate debt than there has been,” Mr. Pollack said in an interview.

The fund will make new loans and buy real-estate debt securities along with other investments. Blackstone’s real-estate debt business has grown to $26 billion of property debt assets under management, up from $10 billion five years ago. Overall, its global real-estate portfolio is valued at $329 billion.

Fundraising by private-equity firms has declined overall this year as the pandemic created enormous uncertainty and barriers to travel and other business practices especially in the early months. As of mid-September, private-equity funds had raised $81.5 billion compared with $142.9 billion during the same period last year, according to data firm Preqin.

But it is beginning to pick up. Other recent closings include a $950 million real-estate debt fund raised by KKR & Co. that is focusing on the most junior tranches of commercial mortgage-backed securities.

During the first few months of the pandemic “everybody regardless of lender class was assessing their own portfolio,” said D. Michael Van Konynenburg, president of Eastdil Secured LLC. “Once people got to July they felt they understood where their own portfolios are and started to ramp up and look for new deals.”

Much of the new capital raised is by firms planning to focus on distress properties. Billions of dollars of loans backed by malls and hotels are in default, according to data firm Trepp LLC. At the same time, many of the traditional lenders, like originators of commercial mortgage-backed securities, have put on the brakes. That is increasing the rates borrowers are willing to pay to lenders still in the game.

“New capital invested expects to earn greater returns,” said Mr. Pollack.

Blackstone’s debt funds—which have historically returned about 10% annually to investors—tend to avoid riskier debt deals. Much of its business involves making first mortgages to some of the world’s largest real-estate companies and investors.

For example, Blackstone might make a loan today to the buyer of a well-leased office building that was in contract to be sold before Covid-19 hit and the deal collapsed. “It’s going to get done today in much more uncertain capital markets,” Mr. Pollack said.

“Twelve months ago the guy buying the building would get 12 different term sheets from lenders of all stripes,” he said. Today fewer lenders will be able to give the buyers the certainty they need that they can close the deal “and they’ll pay more” for certainty, Mr. Pollack said.

Mr. Pollack said Blackstone’s debt portfolio hasn’t suffered many problems from loans it made before the pandemic. He said that is partly because Blackstone’s low risk loans are typically about 60% to 65% of the values of the properties.

“It also helps to be very selective about who you lend money to,” Mr. Pollack said. He pointed out that Blackstone’s borrowers have tended to be “well capitalized institutional investors that you would expect to hold on to [properties] through a period of dislocation.”

Updated: 10-25-2020

Landlords Challenge U.S. Eviction Ban And Continue To Oust Renters

A lawsuit backed by the National Apartment Association and other challenges aim to undo the national eviction moratorium ordered by the CDC.

In September, the Trump administration announced a national moratorium on evictions, via an order by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention aimed at reducing the spread of coronavirus. The four-month temporary suspension applies to any tenant who can’t make rent due to economic conditions and who presents a written declaration about their circumstances to their landlord.

But the CDC ban now faces legal challenges on multiple fronts, even as landlords continue to routinely file evictions for nonpayment of rent — the very outcome that the order was designed to prevent.

On Oct. 20, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Georgia heard the first case against the moratorium, Richard Lee Brown, et al. v. Secretary Alex Azar, et al.. That challenge, brought by a nonprofit called the New Civil Liberties Alliance, has been joined by the National Apartment Association, which represents some 85,000 landlords responsible for 10 million rental units.

Lawyers and scholars working on behalf of plaintiffs in the cases say that the CDC lacks the constitutional authority to enact a policy affecting rents.

“This is a very sweeping measure,” says Ilya Somin, law professor at George Mason University. “It’s being done on the basis of laws and regulations that allow the CDC to adopt regulations to stop the spread of contagious disease across state lines. If these regulations are broad enough that they give the CDC the authority to adopt an eviction moratorium that applies to the entire country, then they’re broad enough to mandate or restrict almost any kind of activity.”

A decision for a preliminary injunction could be issued, or denied, within the next two weeks. That could throw open the door for landlords to pursue their claims in court before the moratorium expires at the end of the year.

Such a decision could trigger a surge in evictions: More than 6 million households missed their rent or mortgage payment in September, according to an analysis by the Mortgage Bankers Association. Recent surveys by the Census Bureau show that as many as 11 million people living in rental housing — 1 in 6 adult tenants — were late or behind on rent as of last month.

Other studies show that the ranks of people living in poverty have grown by some 8 million people after increases to the social safety net in the spring were allowed to lapse.

A separate suit brought by the Pacific Legal Foundation is still pending. One of the plaintiffs in that case, a landlord just outside New Orleans who was originally blocked from evicting a tenant by the CDC moratorium, dropped out of the challenge after she was able to pursue the eviction by a different means. Another challenge in Ohio faltered for a similar reason.

Tenant organizers point to these dropped cases as an illustration of the porousness of the federal moratorium. The policy has led some landlords to pursue nitpicking lease violations or punitive measures against tenants who are unable to pay rent — tenants who would otherwise enjoy protection under the CDC’s aegis if they went to court.

“It’s not a protection at all for many renters,” said Alana Greer, director and cofounder of the Community Justice Project, a Miami-based nonprofit, during a press conference earlier this month. “This week alone, we’ve had two clients whose electricity was shut off in their building after serving the CDC moratorium,” she said, referring to the declaration required under the order.

The previous federal eviction moratorium, which was authorized by Congress as part of the CARES Act and applied to a narrower subset of renters, expired in July. So did the $600-per-week federal boost to unemployment benefits that proved so critical to out-of-work renters. The first federal moratorium also faced several legal challenges; none of the suits succeeded.

It’s not just landlords pushing back against the eviction moratorium this time, however. The Texas Supreme Court issued an emergency order in September to clarify that landlords can still seek an eviction by challenging the declaration provided by tenants under the CDC order.

Jeremy Brown, a justice of the peace in Harris County, Texas — where thousands of Houston tenants have been evicted since the onset of the pandemic — says that most tenants don’t realize their rights and even fewer have the legal resources to successfully pursue them.

“Regardless of your crime, if you get arrested, there’s an obligation for that arresting agent to tell you that you have certain rights,” Brown says. “The right to counsel, the right to remain silent — that same obligation is not there for housing.”

And the CDC itself released an update on Oct. 9 indicating that landlords could still file eviction for nonpayment even if the cases could not be heard until the new year. Civil rights advocates say that this guidance effectively undoes the eviction ban, since so many tenants lose their eviction hearings by default by not showing up for the case once they receive an eviction notice.

“Why would a landlord want to start eviction proceedings in October for an eviction that can’t happen until January?” says Diane Yentel, president and CEO of the National Low Income Housing Coalition. “The answer: to pressure, scare or intimidate renters into leaving sooner.”

“If there wasn’t a pandemic going on, they wouldn’t be able to impose a moratorium.”

Attorneys for the plaintiffs point to a constitutional question: Congress cannot delegate to the executive branch what is effectively legislative authority, and the CDC order usurps this law-making power, they say. Conservatives and libertarians eager to curb the administrative state have used the non-delegation clause as an argument to some success.

Somin at Geoge Mason University points to Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan’s argument in Gundy v. United States that there is a violation when “unguided and unchecked” authority is given to a federal agency or an executive branch official.

“If the CDC has the power to prevent virtually any activity simply by claiming that doing so might reduce the spread of contagious diseases, and they don’t even have to prove that it actually will, that is as ‘unguided and unchecked’ as anything that I can think of,” Somin says.

Steve Simpson, senior attorney for the Pacific Legal Foundation, says that in addition to the constitutional question, the CDC lacks the statutory authority to enact an eviction ban. The texts for the regulation (42 CFR § 70.2) and the underlying statute (42 USC § 264) both list fumigation, inspection and extermination among the available powers. The statute also authorizes “other measures” as deemed necessary.

“You can’t read a catch-all provision like that, especially when it has enumerated things the CDC can do, so broadly as to obviate the rest of the statute, to make it all pointless,” Simpson says. “Why bother enumerating things if they can basically do anything they want?”

Eric Dunn, director of litigation for the National Housing Law Project, a housing justice nonprofit, says that the plaintiffs have no grounds for the solution they’re seeking. Plaintiffs hope to see a preliminary junction that unfreezes evictions immediately, since the actual resolution of the case could last far longer than the moratorium itself.

When the injury in question is entirely economic in nature (and not irreparable harm”), courts by and large won’t issue a preliminary injunction. The injury in eviction challenges such as Brown v. Azar is exclusively economic, Dunn says.

Beyond that technical issue, Dunn says that emergency powers by definition explain the CDC’s statutory authority to take steps normally not available to the agency.

Experts dealing with communicable diseases need to be able to take action in order to prevent them from spreading when there’s not time to convene legislative bodies or committee hearings to write new laws — or when there’s no will to do so, as the present stalemate in the Senate has shown. “If there wasn’t a pandemic going on, they wouldn’t be able to impose a moratorium,” he says. “This is a pandemic.”

The public health risks associated with evictions have been modeled by Michael Levy, an epidemiologist at the University of Pennsylvania. His research — which was independent of these legal challenges to the CDC moratorium — focused on the potential effect of evictions on the spread of Covid-19.

When tenants are evicted, they often move in with other family members, increasing the size of households and the chance for viral transmission. Levy’s model predicts that a 1% eviction rate would result in a 5% to 10% higher incidence of infection, leading to approximately 1 death for every 60 evictions.

Housing advocates cite evidence like that to argue that the displacement of even a small fraction of the millions of renters at risk of eviction would inflict lasting damage on the economy, further spread the coronavirus, and bring unspeakable pain for families.

No matter what the courts decide, struggling tenants still face a potential catastrophe: With no further coronavirus aid likely coming before the November election, they’ll have to find a way to pay when the eviction moratorium expires and all the rent comes due immediately. That could happen later, on Dec. 31, or it could happen sooner.

And even under the moratorium, evictions for nonpayment still continue, albeit at a slower rate.

“We treat housing in this country as a commodity more so than a right,” says Brown, the justice in Houston. “Somebody in my court might have mold in their apartment. It may be uninhabitable. If they don’t pay rent, they still get evicted. The pandemic has highlighted these issues, not caused these issues.”

Updated: 11-18-2020

Hot Mortgage Market Is The Fed’s House of Cards

Many Americans have weathered the pandemic by refinancing their homes and benefiting from soaring property values. But what happens next?

When the definitive story is written about U.S. financial markets during the coronavirus pandemic of 2020, expect America’s housing market to play a starring role.

In many ways, it’s hard to reconcile worsening Covid-19 outbreaks with record-high levels for the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the S&P 500 Index, or the unprecedented surge in unemployment earlier this year with the fact that American households are by some measures in their best financial shape overall in decades, regardless of wealth level. It becomes a bit easier to see what’s happening when using the mortgage market as a frame of reference.

Benchmark 30-year mortgage rates have slowly but surely dropped to record lows throughout the pandemic, touching 2.78% earlier this month, according to Freddie Mac data. This has naturally encouraged more and more homeowners to refinance their mortgages, thereby allowing them to lower their monthly payments or tap equity.

With more cash in their pockets, these people have kept spending levels relatively steady while also socking money away or investing in stocks or other assets. Janet Yellen, the former Federal Reserve chair and contender to be President-elect Joe Biden’s Treasury secretary, said during the Bloomberg New Economy Forum on Monday that a “savings glut” was helping to prop up financial markets.

What she didn’t say, and what’s flown largely under the radar amid the central bank’s efforts to bolster the economy, is the Fed’s role in pushing the $6.8 trillion mortgage-backed securities market to extremes. I wrote last month that the Fed might resort to infinite quantitative easing to support the $20.4 trillion U.S. Treasury market. But if the central bank ever steps away from backstopping mortgage bonds, there’s reason to believe the consequences could be even more dire.

As it stands, the Fed has bought more than $1 trillion of mortgage bonds since March, a record pace, and now holds $2 trillion of the securities on its balance sheet. That easily eclipses the previous high during the last economic recovery.

Central bankers have pledged repeatedly to keep adding bonds each month “at least at the current pace,” which is often quoted as $40 billion. But that’s actually a net figure: Total monthly purchases tend to be closer to $100 billion because borrowers’ principal repayments take out some debt already on the Fed’s balance sheet.

In recent weeks, the Fed has taken its mortgage-bond buying even further. On Oct. 29, it took the unprecedented step of purchasing conventional 30-year securities with a 1.5% coupon, the lowest now available. Though it’s been careful not to go overboard, the move is nonetheless a clear indication that the central bank doesn’t expect to raise interest rates in the years to come.

All of this serves to squeeze mortgage-bond investors in higher-rate securities. Most of them bought the debt at a premium, and the constant reduction in lending rates leaves them vulnerable to prepayment risk as homeowners refinance and pay off their existing obligations at par. But it would be arguably even more painful if investors are herded into ultra-low coupon MBS, only to see rates rise.

Known as “extension risk,” fund managers left holding 1.5% or 2% MBS could be saddled with huge losses if longer-term interest rates start to increase next year as the U.S. economy rebounds and inflation starts to pick up on the back of a Covid-19 vaccine.

It should be clear by now that the Fed is in a tricky spot. On the one hand, pushing down long-term mortgage rates is one of the most direct ways the central bank can bolster household balance sheets. And yet the Fed desperately wants inflation above 2% and for the U.S. economy to bounce back.

If America indeed comes roaring back next year, longer-term Treasury yields should jump higher, as would the benchmark 30-year mortgage rate. But if that happens too quickly, and homeowners can no longer free up cash, that removes a key pillar of support for the economic recovery.

JPMorgan Chase & Co. may have a temporary answer for the Fed’s dilemma. Michael Feroli, the bank’s chief U.S. economist, predicted on Monday that the Fed will announce at its December meeting that it will tilt its bond buying toward longer-dated Treasuries, potentially doubling the weighted average maturity of its $80 billion of purchases. This would presumably pin down 10-year and 30-year yields, and, by extension, mortgage rates, even with the economy on the mend.

Fed Vice Chair Richard Clarida on Monday indicated that policy makers are still monitoring asset purchases, though he gave no indication they were leaning in the direction of extending maturities. Still, it’s the logical next step, in the same vein as Operation Twist.

Regardless of whether policy makers go that route, it’s hard to see a way out of the mortgage market for the Fed without causing at least a hiccup in the U.S. housing market and an implosion at worst.

As my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Aaron Brown wrote last week, even though U.S. home prices are nearing all-time highs, the current market isn’t necessarily a disaster in the making because the high valuations are the result of rock-bottom interest rates. However, as he made clear: “It’s one thing to be a peak valuation, it’s another to be at peak valuation with no discernible upside.”

If there’s a modest correction in housing prices, that shouldn’t be too disruptive for the economy as a whole. Rather, it’s the second-order effects of higher mortgage rates that should concern investors. As Bloomberg News’s Christopher Maloney reported, aggregate Fannie Mae 30-year prepayment speeds in September increased to their fastest since April 2004, and Wall Street analysts expect that the current “perfect refinance environment” can last awhile longer.

If that doesn’t happen, for whatever reason, it would remove a crucial variable behind sustained consumer spending and the rally across risky assets.

As the calendar turns to 2021, Fed officials will need to figure out how to engineer a soft landing for the housing market. The refinancing boom the central bank engineered has helped countless Americans get through the pandemic. But it can’t afford to see it go bust. Most likely, the Fed won’t be able to extricate itself from buying mortgage bonds for at least the next several years, and possibly longer, or else risk toppling the entire house of cards it built.

Updated: 11-19-2020

U.S. Homebuyers Put Up Biggest Down Payments In 20 Years

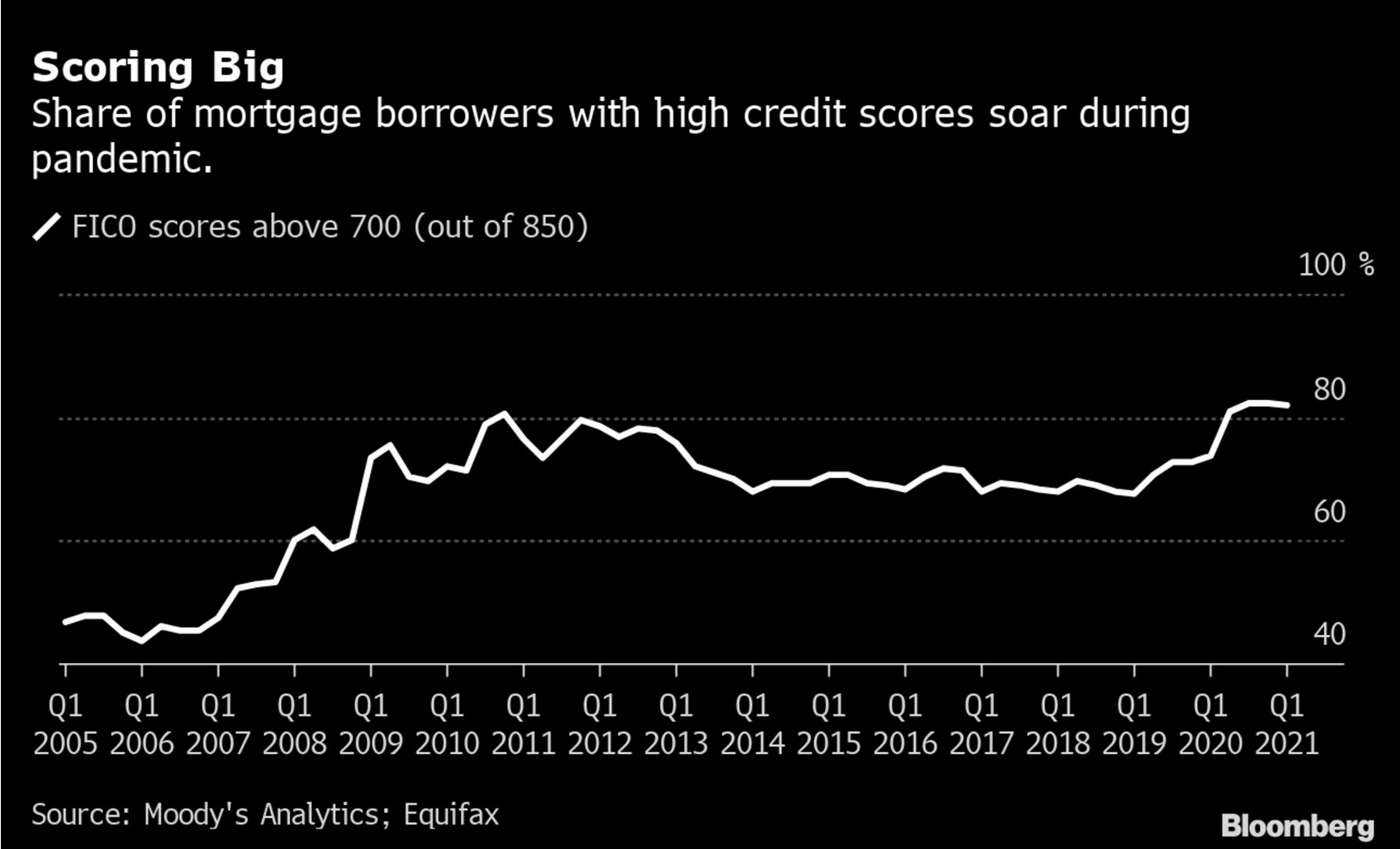

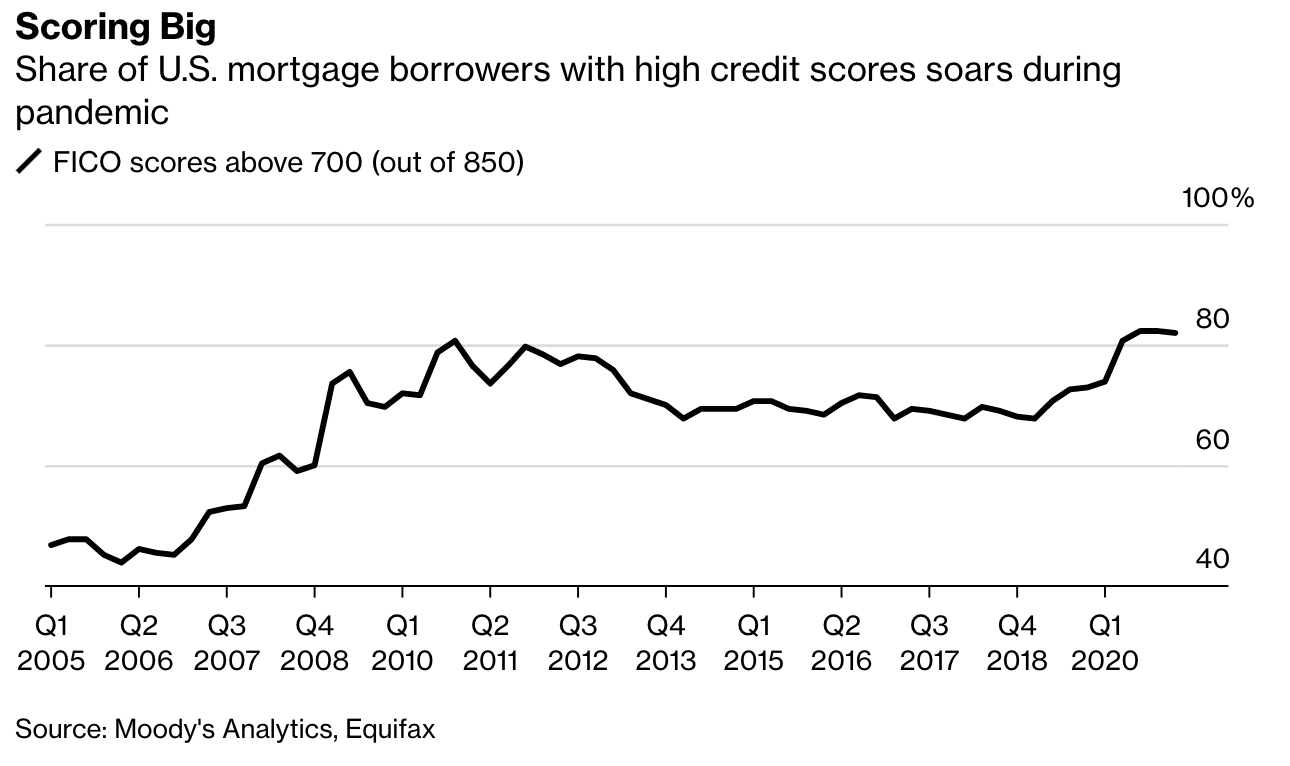

Homebuyers, facing tightening credit standards and skyrocketing prices, are putting up the biggest down payments in at least two decades.

The median down payment for single-family homes and condos in the U.S. was $20,775 in the third quarter, the most in records going back to 2000, according to a report from Attom Data Solutions. That’s up 69% from $12,325 a year earlier, before record low mortgage rates kicked the housing boom into a higher gear.

Borrowers put up 6.6% of the median sale price of homes financed in the quarter, up from 4.7% a year earlier and the highest level since 2018. The median loan amount in the quarter of $275,500 was the highest since 2000, up 24% from the third quarter of last year.

”Down payments are rising at a time when lenders are tightening their guidelines,” said Todd Teta, chief product officer at ATTOM Data Solutions. “Lenders have grown more cautious in order to protect themselves from more delinquencies.”

Mortgage companies are raking in cash in the midst of the pandemic, earning hefty margins while consumers flood in to buy homes or refinance existing loans to take advantage of record-low mortgage rates. The average for a 30-year, fixed loan tumbled to 2.72% this week, the lowest in data going back almost 50 years, Freddie Mac said Thursday.

It’s no wonder that lenders have gotten more picky than they have been in decades.

Lenders including JPMorgan Chase & Co. have tightened terms for borrowers amid widespread worry about future economic growth. JPMorgan, for instance, told loan officers earlier this month that it would limit jumbo loans to 70% of the sale price for most co-ops and condominiums in Manhattan.

The typical borrower last quarter had a 786 credit score, the highest median score in quarterly figures dating to 1999, according to data maintained by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

The $1.05 trillion of home mortgages originated last quarter was the highest since 2003, New York Fed data show, when homeowners across the country were taking advantage of a previous historic refinancing boom.

Updated: 2-11-2021

Why Can’t The Government Stop Evictions?

A patchwork of protections has so far prevented the “tsunami” of evictions that housing advocates fear. But in many U.S. cities, the number of filings is growing.

Alice Nondorf spent the holidays waiting to be evicted from her home in Manhattan, Kansas.

Unable to work and relying on disability benefits, Nondorf says she had struggled to pay rent for her $700-per-month apartment since September. At the same time, she escalated complaints to the city about roaches, bats in the walls and broken appliances that she says the building’s new management failed to address.

After her lease rolled over at the end of October, Nondorf and her fiancé, Gary LaBarge — who was living in an adjacent unit on a month-to-month lease, and who has stage 4 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease — received notices in November to vacate.

The couple applied for emergency rental assistance. They also filed the declaration forms required under the federal eviction moratorium issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in September.

But attorneys for the landlord told Nondorf that the CDC order didn’t apply, since the landlords were simply declining to renew the couple’s leases. And while Nondorf and LaBarge were each eligible for up to $5,000 in rental assistance in Kansas, their landlord wouldn’t take the money.

“The CARES fund was there,” says Nondorf, who was served with an eviction order in mid-January. “We reached out to our landlord. ‘I know we owe rent. We’re not trying to screw you.’ They flat-out refused.” (Nondorf’s landlord, Rodney Steven III, confirmed the eviction but declined to answer other questions.)

The Kansas couple are among the thousands of households in the U.S. at risk of tumbling through gaping loopholes in the regime of federal, state and local orders designed to keep people housed during the pandemic.

As newly appointed CDC Director Rochelle Walensky explained in her order extending the federal eviction moratorium on through March 31, preventing evictions is critical to contain the spread of Covid-19: Displaced households can end up homeless or crowded into shared apartments with friends or extended family, increasing the risk of infections.

President Joe Biden made the federal eviction ban one of his Inauguration Day priorities. Yet eviction filings continue to mount by the thousands in courthouses across the country.

Nearly a year into the pandemic crisis, a much-feared nationwide “tsunami” of evictions has yet to materialize. Instead, changes in tenant protections have led to a more gradual groundswell in eviction filings.

Legal challenges to remove tenants are up almost everywhere, according to a year’s worth of data across 27 U.S. cities tracked by Princeton University’s Eviction Lab and reviewed by Bloomberg CityLab. Even with the CDC moratorium in place and extended into spring, evictions are rising, which has advocates worried about displacement without more decisive federal action.

“Generally speaking, the CDC moratorium is doing what it was intended to do,” says Diane Yentel, president and CEO of the National Low Income Housing Coalition. “But there are many shortcomings in the order and an alarming number of evictions despite the moratorium. We have been calling on Biden and CDC Director Walensky to not only extend the moratorium, but to strengthen and improve and enforce the moratorium.”

Yentel and Shamus Roller, executive director of the National Housing Law Project, sent a letter to Walensky on Jan. 21 requesting a meeting to discuss ways to improve the federal eviction ban. They haven’t received a reply yet. Along with other tenant and housing leaders, they point to problems plaguing the federal government’s efforts to support renters through the pandemic.

Tenants need to know their rights in order to exercise them. Landlords can let the clock run out on a lease. Violations are rarely enforced. And most emergency rental aid programs require buy-in from landlords.

“The landlord has to sit down with you and do that paperwork, or you don’t get the money,” Nondorf says.

Beyond the CDC order, a patchwork of state and local protections protect millions of tenants in the U.S. from eviction. In many places, it’s these local protections that make the difference in the swing in eviction filings.

In New York City, for example, eviction actions plummeted to zero back in March, shortly after the novel coronavirus surfaced in the U.S. and Congress issued the first federal eviction moratorium as part of the original CARES Act.

At the same time, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo also issued a 90-day ban on all eviction proceedings, fully backstopping the federal order, which applied to many but not all renters. Once those federal and state orders lapsed over the summer, eviction filings picked back up again.

Filings in New York City fell off once again in January, after the state passed the COVID-19 Emergency Eviction and Foreclosure Prevention Act of 2020, another ironclad eviction ban.

Elsewhere, the story was different. Back in the spring, eviction filings also fell in Houston and Phoenix — where notorious “rocket dockets” typically process hundreds of evictions every day — but they never quite fell to zero. Since then, eviction proceedings have gradually gathered steam.

For now, tenants in Harris and Maricopa Counties are protected only under the CDC order, which permits filings but does not allow evictions for nonpayment, so long as tenants can produce a declaration that qualifies them.

The strength of an eviction order comes down to the details and procedure. Under the recent law in New York, any and every notice that a landlord gives to tenants must be accompanied by a hardship declaration form. The form protects tenants from eviction under just about any circumstances — not just for nonpayment but for holdover proceedings, such as when a renter’s lease expires.

That form shows up at every step along the way: When a landlord issues a five-day notice over late rent, tenants get the hardship declaration. If a landlord escalates with a rent demand, tenants get the hardship declaration. Once the court gets involved, the court, too, will make sure the tenants sees this form. Under the CDC moratorium alone, it’s up to tenants to know about their rights.

“Right now in New York, the federal moratorium is more lax than what our state moratorium is. The qualifications for the federal moratorium are less than what our state qualifications are,” says Lisa Faham-Selzer, partner at Kucker Marino Winiarsky & Bittens, a Manhattan-based law firm that represents commercial and residential property owners. The full stop on housing court proceedings in the state lasts through Feb. 28, and longer for those impacted by the pandemic. “If you are affected by Covid, and all you have to do is supply a little bit of a hardship declaration, you’re stayed through May.”

Around the country, local and state actions make all the difference. In Boston and Pittsburgh, filings spiked after state moratoriums expired, while local and state orders have kept eviction filings out of courts in Austin and Minneapolis.

Generally, these orders have softened over time, as governors and courts have chipped away at them or as the clock ran out, even as the pandemic got worse. Winter is typically the slowest season for evictions, but the pandemic winter saw filings trending upward in cities across the U.S. As of February, few local or state orders remain.

Filings alone don’t tell the whole story. New York has expanded the right to counsel in eviction cases for tenants across much of the city. Between that and the state order, Faham-Selzer says, exceedingly few orders to vacate were ever served, even while landlords were able to legally file for eviction. Since the start of the pandemic, across all five boroughs, only a handful of eviction orders have been executed. Pressure may be building for a surge of evictions once the state order lifts.

At the same time, eviction filings alone are often enough to pressure a tenant to leave. In Kansas City, Missouri, activists with the group KC Tenants have tried to stop eviction filings by physically blockading the doors to the Jackson County Courthouse and disrupting Webex conferences to shout down online hearings.

Tenant advocates in Jackson County have been especially heated since court deputies shot a man while they were serving him an eviction notice last month. A judge put a temporary stay on evictions in January; between the order and their direct actions, KC Tenants claim they prevented more than 700 evictions last month.

“We need immediate relief. An expanded eviction moratorium, including a ban on all eviction filings, summons, hearings, judgments, and writs of execution,” said Tiana Caldwell, board president for KC Tenants, in a call with reporters. “Biden should do this tomorrow. Congress should strengthen and expand it in the next relief bill.”

Eviction filings haven’t reached pre-pandemic levels in most places. In Ohio, for example, 2020 filings have stayed mostly below average 2015–19 levels for Cincinnati, Cleveland and Columbus. It’s hard to know how many evictions are actually happening.

A lack of data makes it incredibly difficult to track evictions even in normal times, and the pandemic presents some special obstacles to measuring housing precarity across the country. Thousands of landlords aren’t filing evictions now but may yet still; thousands of evictions, legal or otherwise, simply aren’t being recorded.

Calls For Reform

In their letter to Walensky, Yentel and Roller call on the CDC to overhaul the federal eviction moratorium. Housing advocates want to see a universal moratorium — one that applies whether tenants know it exists or not. The letter asks Walensky to block eviction filings, not just eviction orders or writs, to keep landlords from using the legal process to intimidate renters.

The letter also appeals to the CDC to expand protections for nonpayment to cover no-fault evictions or hold-over evictions for tenants whose lease has ended. These changes would make the federal moratorium work more like the state-level orders that successfully brought eviction filings to nil.

Another request involves stiffening enforcement: Yentel and Roller call on the Biden administration to establish a national hotline number for tenants to report landlords who violate this beefed-up CDC moratorium — and for the U.S. Department of Justice and Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to enforce its terms and penalties. Legal confusion also poses a threat.

Numerous efforts to overturn eviction bans have failed thus far in federal court, although challenges continue. But at least three local state courts have blocked or invalidated the CDC order anyway since November, according to a letter to the DOJ from the American Civil Liberties Union and National Housing Law Project.

Eviction bans are unpopular with landlords, of course. Faham-Selzer says she represents a New York client in a case that started in 2018; the tenant hasn’t paid rent since 2016. Winter maintenance costs and property taxes still apply even if the rent (and mortgage) payments have stopped.

As the pandemic stretches on, landlords say they are suffering, especially the smaller mom-and-pops. But the logic behind the CDC’s eviction order isn’t economic. Evictions lead to family members living together in greater numbers, speeding the spread of Covid-19; a universal eviction ban put in place at the start of the pandemic might have prevented thousands of deaths.

Tenant organizers and industry representatives alike agree on one solution to stop evictions: give tenants cash. Leaders of six left-leaning think tanks, including the Roosevelt Institute and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, issued a letter on Feb. 1 to leaders in Congress calling for assistance above and beyond the $25 billion in emergency rental relief included in the December stimulus.

Leaders with the National Apartment Association, National Association of Realtors and 10 other industry groups sent a separate letter on Feb. 4 to the House asking for the same.

But rental aid wasn’t any help to Nondorf, who says she was eligible for up to $5,000 through the Kansas Eviction Protection Program. That program — and many others like it — requires landlords and tenants to apply jointly, with the money delivered directly to landlords. “If you’re not in good with your landlord, there’s the first obstacle,” she says. Her experience isn’t atypical.

Barriers To Cash Assistance

For landlords, emergency aid comes with strings attached. A significant share of state emergency rental assistance programs (38%) require landlords to agree to not evict for some period of time, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

About one in five state programs (21%) ask them to waive late fees. A similar share (17%) require landlords to forgive some level of overdue rent.

These requirements can go further. In order for a tenant to participate in Philadelphia’s emergency rent assistance program, for example, their landlord must hold a valid rental license and be current on their taxes, in addition to agreeing to limitations on evictions and forgiving past-due rent. And the rental unit must meet a standard of habitability based on the tenant’s testimony.

A survey released in December by the Reinvestment Fund and the Housing Initiative at Penn found that some 8,900 tenants applied for rental aid in Philly, but only a little more than 4,000 tenants got help, with many eligible applicants excluded because their landlords refused to participate.

So why would landlords opt out of thousands of dollars in potential government assistance they’ll otherwise never see again?

For any number of reasons: beliefs about federal aid, confusion over the requirements, unease with the concessions, informal or unlicensed arrangements, interpersonal conflicts with tenants, or some combination of concerns.

Race is almost certainly a factor in landlords’ decisions about evictions; Black tenants in Philadelphia face an annual pre-pandemic eviction rate (8.8%) that is almost three times higher than white tenants (3.1%). The vast majority of evictions filed in Boston since the start of the pandemic are located in areas with larger Black or immigrant populations.

For the $25 billion in emergency rental aid included in the stimulus package passed by Congress in December, tenants will be able to apply for relief directly if their landlords won’t comply. While this is ostensibly a measure to ease the administrative burden, it’s not clear how this is supposed to work in practice for the dozens of state or local aid programs that pay out directly to landlords or require their signatures.

“It creates a good opportunity for tenants to receive the payment, in the case where the landlord refuses, but there are a lot of barriers to the tenant applying themselves,” says Mariel Block, staff attorney for the National Housing Law Project. “There’s no requirement right now about tenants having an accessible portal to apply directly in the case when landlords refuse. A landlord can refuse and a tenant might not have an avenue to apply or figure out what to do.”

The hypotheticals only compound from there. If a landlord can’t or won’t accept assistance from the state, what is a tenant supposed to do with the money? Could a tenant whose landlord refuses to participate in a rental assistance program apply for aid to use as a down payment at a new apartment? Housing advocates are seeking guidance from Treasury about the bounds of the aid program.

The outlook for emergency assistance varies from place to place. Block says that the program works well in places like Seattle, where landlords can choose to either accept aid for every eligible tenant in their buildings or get none at all, leaving little opportunity for animus or malice.

But landlords in other cities would likely resist the Seattle approach, she says; some cities don’t have the staff or technical expertise to ensure that emergency rental aid is administered smoothly. Programs that didn’t deliver aid efficiently before the pandemic — or didn’t exist at all — are being put to the test by a global emergency.

By far, the biggest obstacle to keeping tenants in their homes over the next year is the lack of funds. There’s not yet anywhere close to enough money to match the need, tenants and advocates say. With U.S. renters behind by as much as $70 billion, they will need at least a third round of stimulus.

Biden has proposed another $30 billion for the package that Congress is currently debating. But many millions of dollars in aid may be lost due to red tape or landlord reticence. The only real solution to pandemic evictions would have been to have a broader working housing safety net before the crisis struck. That’s something that Biden has also pledged to address.

For her part, Nondorf says she and her fiancé only narrowly avoided being put out on the street. After the order for their evictions arrived in mid-January, they managed to secure federal income-based public housing.

The week the couple were supposed to move, Covid-19 hit their moving company as well as staff at their new apartment building. They finally moved in late January, two days before sheriffs were due to arrive. Nondorf says that they are still pursuing their legal options over what they consider to be retaliatory evictions.

“We are doing better,” she says. “We are safe. We are in a place with clean hallways, working laundry machines, and someone who shovels the snow the next day. And no bats.”

Updated: 2-14-2021

GOP State Lawmakers Are Slowing Emergency Rental Dollars from Congress

In Idaho and Michigan, federal aid for renters has met resistance from Republican-led legislatures, forcing cities and counties to find workarounds.

As many as 76,000 households in Idaho have struggled to make rent payments during the pandemic, and 34,000 households may soon face the threat of eviction, according to the Idaho Center for Fiscal Policy. To address the housing crisis, the state is set to receive $200 million in emergency rental assistance — their share of the $25 billion in housing aid in the Covid relief bill passed by Congress in December.

But in a budget committee hearing on Feb. 8., Idaho State Representative Ron Nate argued that the state shouldn’t take the aid. “Going forward into the future, seems like we’re choosing between economy and dependency,” the GOP lawmaker said. He and three other Idaho Republicans voted to reject the federal assistance.

A similar standoff over rental assistance is flaring in Michigan. Even as Democratic leaders in Congress debate the scope of the next coronavirus relief package, Republican state lawmakers are slow-rolling millions of dollars in relief from the last bill. That’s forcing some cities and counties to pursue workarounds — seeking aid directly from the federal government.

Threats to stall or block aid distribution could have real-world consequences for tenants: States have only so long to spend the money from Treasury before they lose it. And other bottlenecks still await.

In Michigan, Republican lawmakers have taken steps to release only a fraction of its nearly $661 million allocation. The state received its emergency housing funds in January, the week of President Joe Biden’s inauguration; the fund has been idling ever since. “There is a chance that due to delay we are putting those dollars at risk,” says Eric Hufnagel, executive director of the Michigan Coalition Against Homelessness.

“When you’re talking about losing tens of millions of dollars, that’s very significant. That shouldn’t be held hostage due to political shenanigans.”

The status of federal relief funds has emerged as a chasm between the Republican-led state legislature and Governor Gretchen Whitmer, a Democrat. The governor chastised state lawmakers on Tuesday after both the Michigan House and Senate introduced plans to meter out the federal funding approved by Congress. Lawmakers have proposed releasing one-quarter of the emergency rent relief for now.

Michigan currently faces a gap: Funds for an eviction diversion program from the last go-round of federal relief have already been exhausted, so there’s no help for households who need urgent assistance now. Even if the state releases the aid sooner rather than later, gaps could have consequences. Congress has stipulated that 65% of the funds must be obligated by Sept. 30; in order to meet that marker, the state will need to spend about $50 million per month.

If the state legislature’s delay extends into March, that figure rises to $60 million per month. Spending this money has proven difficult for states, due to red tape, beleaguered systems and landlord reticence. “We will see people adversely affected due to this waiting period,” Hufnagel says.

In Idaho, federal rental aid was approved by budget committee, and a supplemental funding bill for the money will be assembled this week; then the measure needs to win the approval of both the Idaho House and Senate. There’s no timeline for this action. Hundreds of tenants have been evicted in the Boise area in recent weeks, despite the federal stay on evictions issued by the Centers on Disease Control and Prevention.

“Prior to the pandemic, the state of Idaho did not administer a statewide rental assistance program or any other form of housing assistance,” says Kendra Knighten, policy associate for the Idaho Asset Building Network, in an email. “Due to this lack of background, we are concerned that many of Idaho’s lawmakers underestimate the urgent and widespread need for rental assistance throughout our state and do not consider it to be a priority.”

Nate, an economics professor and one of four Idaho lawmakers who voted against a budget measure with a total of $176 million for renters, was the lone representative to make any statement about the congressional appropriation, pointing to moral and practical objections. “In principle I think we should follow the path of economy and freedom,” Nate said during the budget hearing, noting challenges in oversight and administration.

In an email, he elaborated: Accepting the funds would have a negative impact on people returning to work, while rejecting the money will open opportunities for “neighborly assistance” and incentives for tenants to find jobs.

“Accepting federal dollars for new programs expands government and increases dependency,” Nate said. “I believe we can and should provide assistance for those in need in Idaho, but private charity is a better avenue because it improves caring, results, and incentives to return to self-sufficiency.”

As USA Today reports, red states will receive disproportionately more rental assistance from Congress than their more populous blue state counterparts: Congress set a $200 million minimum in payouts per state, favoring states with rural populations and fewer renters, such as Wyoming, Vermont and Alaska. That means rent relief “will overwhelmingly benefit white Americans living in less populated states,” reporters Romina Ruiz-Goiriena and Aleszu Bajak conclude.

Most states, red or blue, appear willing to take the money. In Missouri, for example, the Republican-controlled House voted unanimously in January to approve $324 million in federal emergency rent dollars, moving swiftly to fund the Missouri Housing Development Commission. After brief delays, so did Oklahoma and North Carolina.

Perhaps sensing the potential for conflict, Congress included a provision in the December aid bill to allow cities or counties with a population of at least 200,000 residents to apply for funding directly. Ada County in Idaho and its largest city, Boise, have taken this tack, claiming $12 million each from the state’s $200 million share. Urban counties in Arkansas and Oklahoma also sought direct aid. So did Michigan’s Genesee County (home to Flint) and Macomb County (suburban Detroit).

Most local governments in Michigan chose not to apply for funds directly from Treasury, according to Hufnagel, since they stand to get more under the state formula and because it would require extra work. But delays in funding could make it harder for cities and counties to spend their rent relief dollars in time.

North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper signed a bill into law on Wednesday authorizing the first tranche of federal Covid relief. Rental aid was included in that measure — although it too was briefly the subject of debate, says Pamela Atwood, director of housing policy for the North Carolina Housing Coalition. “We’ve learned not to be surprised,” she says.

Updated: 3-21-2021

Why Some Landlords Don’t Want Any Of The $50 Billion In Rent Assistance

Building owners say the aid often has too many strings attached.

A federal program designed to help people avoid eviction by paying their rent is running into an unexpected hurdle: Some landlords are turning down the payment, saying it comes with too many conditions.

Congress has allocated about $50 billion for rental assistance to stave off a surge in evictions of tenants who lost jobs during the pandemic and missed rent payments. The federal support is also meant to help struggling landlords who have to make mortgage payments and have been overwhelmed by tenants falling behind on their rent.

But thousands of building owners across the country are rejecting the government offer. They say the aid often has too many strings attached, such as preventing them from removing problematic tenants or compelling them to turn over sensitive financial information to government agencies or contractors.

Their decision to forgo the cash could be costly for tens of thousands of renters who have been counting on that aid and who are vulnerable when the national ban on most evictions expires at the end of March, though the government could extend it again.

The government has said the money should be used to help low-income tenants pay back part or all of their missed rent for up to 12 months.

In Houston, a nonprofit charged with administering pandemic rental assistance last year said more than 5,600 households who applied for money had a landlord who refused to take it.

In Boston, one tenant attorney said at least 20% of his current cases involve a landlord who refused the funds. “I’ve seen it happen more and more,” said Brian Miller, an attorney at Greater Boston Legal Services.

The city of Los Angeles said that nearly half its tenants receiving rental assistance last year had landlords who declined to participate in the program.