Trumponomics Fails To Deliver As Truckers Cut Payrolls, Job Openings Fall & Tech Hiring Cools (#GotBitcoin)

Job openings fell in February to the lowest level in nearly a year, a sign that demand for workers eased modestly during a month when hiring fell sharply. Trumponomics Fails To Deliver As Truckers Cut Payrolls, Job Openings Fall & Tech Hiring Cools (#GotBitcoin)

Surprise!

Job Openings Fell by More Than 500,000 in February

Available jobs declined to lowest level since March 2018.

There were a seasonally adjusted 7.09 million unfilled jobs on the last business day of February, the Labor Department said Tuesday. That was down by more than 500,000 from January’s near record, to the lowest level of available jobs since March 2018.

“Like the rest of the economy, the labor market is not perfectly steady on its feet—it’s prone to the occasional wobbly month,” said Josh Wright, chief economist at iCIMS Inc., a maker of employee-recruiting software. “As the economy slows, we should see a few more wobbles over the course of 2019.”

Many economists expect the economy to gradually cool as the effects of last year’s tax cuts and stronger government spending fade, and the U.S. faces global headwinds. However, iCIMS, which separately tracks job opening figures, sees a healthy rebound in available positions in March.

The smaller number of openings came during a month when hiring slowed to a crawl. U.S. employers added 33,000 jobs to payrolls in February, revised data released last week showed. That was the smallest net job gain since September 2017, and one of the weakest months in the 102 straight months of improvements, dating back to 2010.

Any easing of demand for workers, however, may be only temporary. Employers added a solid 196,000 jobs to payrolls last month. February’s weakness may have reflected bad weather in parts of the country, slowing hiring and recruitment activities in some sectors, and a cooling after robust gains in both jobs and openings the prior month.

Openings declined in construction, local schools and leisure and hospitality, three categories that can be impacted by weather and temporary closures. Manufacturing openings also declined. Openings increased in professional and business services and held steady in health care.

There were 7.625 million job openings in January, revised data in a Tuesday report showed. That was just 1,000 fewer openings than November, the peak for available jobs on records back to 2000.

Despite February’s decline, jobs remain plentiful compared with the number of Americans who are unemployed but actively seeking work. There were 876,000 more available jobs than unemployed people.

Such a gap has occurred for 12 straight months, but never previously in nearly two decades of monthly records.

The report showed the rate at which workers quit their jobs held steady at 2.3% for the ninth straight month—the longest the rate has ever held at the same figure. That is a historically high rate, just below a record set in early 2001, but some economists have expected quits—a proxy of workers’ confidence in the job market—to move higher with the unemployment rate trending near 49-year lows.

Hiring Growth Slows Sharply As U.S. Adds Just 20,000 Jobs

The unemployment rate edged down to 3.8%.

Hiring growth slowed sharply in February, a sign that weakening global economic growth could be touching the U.S. economy, though strong wage growth and robust job gains in earlier months suggest the U.S. still has significant momentum.

U.S. nonfarm payrolls rose a seasonally adjusted 20,000 in February, the Labor Department said Friday, marking the slowest pace for job growth since September 2017, when hurricanes skewed the data, and falling well below economists’ expectations for 180,000 new jobs.

Jobs were lost in construction, mining and retail last month. Manufacturers added workers but at a slower pace.

“The sharp slowdown in payroll employment growth in February provides further evidence that economic growth has slowed in the first quarter,” wrote Michael Pearce, Capital Economics economist, in a note.

Still, economists warned against reading too much into February’s weaker-than-expected hiring. The three-month average for job gains clocked in at 186,000, a strong rate at this point in the economic expansion.

Slower hiring could also be a sign that employers are struggling to find workers.

A tighter labor market, in theory, should translate into faster wage growth, as employers compete for scarce labor. Friday’s report showed that is materializing: Wages rose 3.4% from a year earlier in February, a pace last matched in April 2009.

Average hourly earnings for all private-sector workers increased 11 cents last month to $27.66.

The labor-force participation rate, or the share of Americans working or looking for a job, held steady at 63.2% in February. That was up slightly from 63.0% a year earlier.

Participation generally had fallen since the early 2000s, as the wave of women entering the labor force slowed and baby boomers began to retire in greater numbers. But the rate has plateaued in recent years, as baby boomers are staying in the labor market longer and more workers are coming off the sidelines, defying expectations of demographic-driven declines.

The average workweek was 34.4 hours in February, down from 34.5 a month earlier.

Tech Hiring Cools In March

U.S. employers across all industries cut 155,000 IT jobs last month, while tech-sector employment rose by 16,000, CompTIA says.

Employers across the U.S. economy cut 155,000 information-technology jobs last month, following a sharp upturn in IT hiring in February, according to an analysis of the latest federal employment data by CompTIA Inc.

A total of 11.8 million people held tech jobs in 2018, up 2.3% from 2017. Tech positions accounted for 7.6% of the total U.S. workforce, up from 7.2%, CompTIA estimates.

Despite employment declines in March, the unemployment rate for IT occupations dropped to 1.9%, from 2.3% in February, the technology trade group said.

Hiring by U.S. businesses for all jobs in March increased a seasonally adjusted 196,000, up from 33,000 the previous month, while the overall unemployment rate inched up to 3.8%, the Labor Department reported Friday.

Postings for core IT positions by employers across all industries in March rose an estimated 62,433, after falling by nearly 40,000 in February, CompTIA said.

The highest demand was for software developers, followed by computer-user support specialists, computer-systems engineers and architects, computer-systems analysts and IT project managers.

Employment at companies within the tech sector rose by 16,000 jobs in March, up from 7,500 in February, with IT occupations accounting for roughly 44% of total tech-sector employment. The total also includes sales, marketing and other nontech positions at tech companies.

The sharpest gains at tech firms were led by IT and software services businesses, and computer, electronics and semiconductor manufacturers, driven by demand for technology-services staff, custom-software developers and computer-systems designers, the group said.

Tim Herbert, CompTIA’s senior vice president for research and market intelligence, said demand for these and other IT skills aligns with recent investments in technology.

“Technology services and software account for nearly half of spending in the U.S. tech market,” he said, citing continued growth in cloud computing, edge computing, 5G wireless networks and other infrastructure technologies.

He expects to see ongoing demand for tech workers in the software development and IT services and application fields.

Truckers Cut Payrolls As Freight Demand Softens

Hiring in broader logistics slows as red-hot growth pace of 2018 cools down.

Trucking companies pulled back from hiring in March as freight demand softened and job growth across the logistics sector slowed.

Carriers cut payrolls by 1,200 jobs last month, according to preliminary figures the Labor Department reported Friday, halting a nearly yearlong expansion amid signs a hot streak that boosted transportation companies’ profits in 2018 is cooling.

Trucking company Covenant Transportation Group Inc. last month lowered its first-quarter profit forecast, citing weaker than expected freight volumes from late January through mid-March.

“We attribute the softer demand to factors such as late 2018 inventory growth in advance of the perceived impact of tariffs, the effects of the partial government shutdown on spending and extended periods of inclement weather,” the company said in a statement.

Warehousing and storage companies added 1,700 jobs in March. It was the slowest month of growth since December in a sector where hiring has grown rapidly as more people shop online. Courier and messenger firms that deliver packages to homes and businesses added 1,800 jobs last month, recovering from a February slide when payrolls shrank by nearly 10,000.

Overall, U.S. employers added 196,000 jobs last month, bouncing back from weak hiring in February as unemployment held steady at 3.8%.

Sectors that feed goods into freight transport networks looked weaker, however. Factories cut 6,000 jobs, the first decline in the sector since July 2017, even though a separate report shows U.S. manufacturing activity expanding. Retail payrolls plunged by 11,700 as the service-sector expansion slowed.

The overall pace of logistics hiring slowed during the first quarter. Trucking companies, parcel-delivery firms and warehouse operators together added 144,500 jobs over the 12-month period ending in March, down from 167,200 in the 12 months through February and 191,200 through January.

The slowdown comes as other signs suggest the freight market is retrenching.

North American heavy-duty truck orders plunged 66% last month compared with March 2018. The Cass Information Systems Inc. Freight Index for U.S. domestic shipments declined year-over-year in February for the third straight month.

Demand for logistics workers is still outstripping supply, however, especially for skilled positions such as truck drivers and forklift operators, said Doug Hammond, zone president at Randstad US, a subsidiary of Dutch recruiting firm Randstad Holding NV.

“We are seeing a number of clients, especially in the retail and retail distribution space, making significant moves in their base wages,” with increases of between 8% and 10%, Mr. Hammond said.

Heavy-Duty Truck Orders Hit Lowest Level In Nine Years

Decline comes as truckers point to excess capacity and dimming industrial shipping demand.

The market for heavy-duty trucks at the heart of the U.S. industrial sector is running out of road.

Orders for Class 8 trucks fell last month to their lowest level since 2010, transportation-equipment research groups said. The July figure is the weakest yet since a strong rebound in truck-buying in 2018 lost steam this year on faltering freight-market demand.

“There is going to be a significant decrease in production coming in the second half of the year carrying into 2020,” said Don Ake, vice president of commercial vehicles at transport research group FTR.

FTR, which tracks equipment purchases by freight transportation carriers, said orders for heavy-duty trucks in North America fell to 9,800 in July, down 82% from a year ago. Separately, ACT Research said it counted 10,200 orders last month, the fewest it has measured in a month since February 2010. Figures for both groups were preliminary, with final reports due later this month.

Truck orders typically bottom out in the summer, with large carriers placing the bulk of equipment orders in the fourth quarter. But the seasonal pattern was upended last year as trucking companies flush with cash from a surging freight market and gains from the federal tax cut placed record monthly orders of more than 52,000 units in July and August 2018, according to FTR.

Now transportation companies are wrestling with “a persistent oversupply of capacity,” Mark Rourke, chief executive of Green Bay, Wis.-based truckload carrier Schneider National Inc., said in an Aug. 1 earnings conference call.

DAT Solutions LLC, which matches available trucks to companies looking to move goods in trucking’s spot market, said its measure of capacity in that arena was up 22.6% in July from a year ago while demand was down 37.3%. Several trucking companies said in their second-quarter earnings reports that increases in contract rates also have pulled back since the start of the year.

Truckers say a big part of the waning demand comes from weakness in the manufacturing sector. The Institute for Supply Management’s closely watched measure of U.S. factory activity fell in July for the fourth straight month, reaching the lowest level since August 2016.

Along with cancellations of orders, the pullback in truck purchases has reduced the backlog at factory lines by more than a third since it reached a multiyear high at the end of 2018.

“The industry backlog declined this quarter to below 200,000 units from its peak of over 300,000 eight months ago,” Tom Linebarger, chief executive of engine-maker Cummins Inc., said in a July 30 earnings call.

FTR now expects factory output of heavy-duty trucks to decline 22% next year to about 275,000 units, down from the 353,000 units forecast for 2019, Mr. Ake said.

“Certainly the pressure to get in line that there was last year does not exist this year,” said ACT Research President Kenny Vieth. “Ultimately, truckers have purchased too many trucks relative to the amount of freight expected in 2019.”

U.S. Budget Gap Widened in First Four Months of Fiscal Year

U.S. tax revenues declined 1.5% over past 12 months, Treasury says.

The U.S. budget gap widened in the first four months of the fiscal year as tax collections fell and federal spending increased.

The government ran a $310 billion deficit from October through January, compared with $176 billion during the same period a year earlier, a 77% increase, the Treasury Department said Tuesday.

Federal outlays climbed 9% the first four months of fiscal 2019, which began Oct. 1, and total receipts declined 2%.

Part of the percentage increase in the deficit was attributable to a shift in the timing of certain payments, which made the deficit appear smaller in the first four months of fiscal year 2018, Treasury said. If not for those timing shifts, the deficit would have risen 40.2% so far this fiscal year.

The tax code overhaul that took effect last year has constrained federal revenues over the past year, while a two-year budget deal has boosted government spending, particularly on defense. On a 12-month basis, revenues declined 1.5%, while outlays have risen 4.4%.

The budget deficit rose to $913.5 billion for the 12 months ended January, or 4.4% of gross domestic product. The last time the 12-month deficit exceeded 4.4% of GDP was in May 2013.

U.S. Posts Record Annual Trade Deficit

The shortfall grew last year despite President Trump’s aim to reduce it.

The international trade deficit in goods and services widened 19% in December from the prior month to a seasonally adjusted $59.8 billion, the Commerce Department said Wednesday. Economists surveyed by The Wall Street Journal had expected a $57.3 billion gap.

The shortfall grew last year despite President Trump’s aim to reduce it.

Over the course of 2018, Mr. Trump imposed tariffs on a range of goods that the U.S. imports from other countries, particularly China, in hopes of giving American producers a competitive edge. He publicly lambasted companies that outsourced jobs, renegotiated pacts with major U.S. trade partners like Mexico, Canada and South Korea, and rankled longtime European allies by deeming their steel and aluminum exports a threat to national security.

Still, the trade gap swelled 12% from 2017 to $621 billion. Excluding services that the U.S. sells to foreigners, such as tourism, intellectual property and banking, the deficit grew 10% to $891.3 billion, the largest level on record.

Economists say the shortfall was fueled, ironically, by another Trump administration policy: tax cuts and spending increases that juiced demand from U.S. consumers and businesses at a time when growth in the rest of the world was slowing. Concern that the U.S. economy could overheat prompted the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates four times in 2018, contributing to a strong dollar in the second half of the year that made foreign goods relatively

As a result, U.S. imports grew 7.5%, while exports increased just 6.3%.

“Higher take-home incomes for households have definitely proven to be very conducive to imports,” said Pooja Sriram, an economist at Barclays. “The outcome has been in almost the opposite direction of what the administration has wanted.”

U.S. imports of consumer goods last year jumped 7.7% to $647.9 billion, fueled in part by a 22% rise in inbound shipments of drugs. Industrial supplies like fuel and crude oil were another driver of the trade gap, with imports rising 13% from 2017 to $575.7 billion.

Highlighting the limitations of Mr. Trump’s trade policies, the goods deficit widened most with China, the U.S.’s largest commercial partner and the main focus of White House efforts. That is partly because Chinese authorities responded to tariffs by drastically scaling back their country’s purchases of key U.S. exports like soybeans, cars and metals, production of which is concentrated in states that Mr. Trump won in the 2016 election.

U.S. goods exports to China fell 7.4% in 2018 to $120.3 billion, while imports from China grew 6.7% to $539.5 billion as Americans increased their purchases of electronics, furniture, toys and other products.

But the deficit in goods also widened in other countries where Mr. Trump aimed his trade war, including the European Union and Mexico.

Most economists disagree with Mr. Trump’s strategy of targeting a reduction in the trade deficit, saying it merely reflects underlying economic forces. But deficits do subtract from gross domestic product, and the widening of the trade shortfall at the end of 2018 was a factor in slower U.S. growth in the fourth quarter.

Andrew Hunter, an economist at Capital Economics, said that’s likely to continue in early 2019 with imports set to grow while weaker global demand weighs on exports.

“Trade now looks set to be a more serious drag in the first quarter,” Mr. Hunter said in a note to clients. He estimates annualized GDP growth will slow to just 1.5% in the first three months of 2019, down from 2.6% in the fourth quarter.

The Idiocy Behind Trumponomics

U.S. deficits may not matter so much after all—and it might not hurt to expand them for the right reasons.

As the national debt swells, some economists are making a once-heretical argument: The U.S. needn’t be so worried about all of its red ink.

The 2017 Republican tax cuts and this year’s Democratic spending proposals have reignited long-simmering worries that the debt is getting too big. Annual deficits are set to top $1 trillion starting in 2022 and the Congressional Budget Office projects debt will total 93% of gross domestic product by the end of the next decade.

Yet borrowing costs are still historically low, despite a surge in deficits and debt in the years following the financial crisis. Debt as a share of GDP rose from 34% before the recession, to 78% at the end of 2018. Treasury yields, on the other hand, have fallen from over 4% before the recession to 2.7%.

That suggests investors aren’t worried about holding large volumes of credit.

In theory, high debt levels should cause interest rates to rise. That’s because investors will demand higher returns to compensate for the risk they take on when the government borrows at unsustainable levels or because they worry that so much debt could trigger inflation. The need to finance such high levels of debt also makes less money available for other investments.

In practice, investors are happy to keep lending to the U.S. in good times and bad, regardless of how much it borrows. In 2009, for instance, when the Obama administration’s stimulus efforts sent federal deficits rising to almost 10% of GDP, the highest since World War II, the interest on 10-year Treasury securities remained below where it had been before the recession.

Many Republicans warned the U.S. was pushing itself to the brink of a fiscal crisis and pressed Mr. Obama to rein in spending. Economists debated how much debt a nation could hold before it crimped growth. In one paper, Harvard University economics professor Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, a former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund, found that countries with debt loads greater than 90% of GDP tended to have slower growth rates.

Now, some prominent economists say U.S. deficits don’t matter so much after all, and it might not hurt to expand them in return for beneficial programs such as an infrastructure project.

“The levels of debt we have in the U.S. are not catastrophic,” said Olivier Blanchard, an economist at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “We clearly can afford more debt if there is a good reason to do it. There’s no reason to panic.”

Mr. Blanchard, also a former IMF chief economist, delivered a lecture at last month’s meeting of the American Economic Association where he called on economists and policymakers to reconsider their views on debt.

The crux of Mr. Blanchard’s argument is that when the interest rate on government borrowing is below the growth rate of the economy, financing the debt should be sustainable.

Interest rates will likely remain low in the coming years as the population ages. An aging population borrows and spends less and limits how much firms invest, holding down borrowing costs. That suggests the government will not be faced with an urgent need to shrink the debt.

Mr. Blanchard stops short of arguing that the government should run up its debt indiscriminately. The need to finance higher government debt loads could soak up capital from investors that might otherwise be invested in promising private ventures.

Mr. Rogoff himself is sympathetic. “The U.S. position is very strong at the moment,” he said. “There’s room.”

Some left-wing economists go even further by arguing for a new way of thinking about fiscal policy, known as Modern Monetary Theory.

MMT argues that fiscal policy makers are not constrained by their ability to find investors to buy bonds that finance deficits—because the U.S. government can, if necessary, print its own currency to finance deficits or repay bondholders—but by the economy’s ability to support all the additional spending and jobs without shortages and inflation cropping up.

Rather than looking at whether a new policy will add to the deficit, lawmakers should instead consider whether new spending could lead to higher inflation or create dislocation in the economy, said economist Stephanie Kelton, a Stony Brook University professor and former chief economist for Democrats on the Senate Budget Committee.

If the economy has the ability to absorb that spending without boosting price pressures, there’s no need for policy makers to “offset” that spending elsewhere, she said. If price pressures do crop up, policy makers can raise taxes or the Federal Reserve can raise interest rates.

“All we’re saying, the MMT approach, is just to point out that there’s more space,” she said. “We could be richer as a nation if we weren’t so timid in the use of fiscal policy.”

So far the runup in government debt has not led to steep price increases. Inflation has stayed at or below the Federal Reserve’s target for most of the past quarter century.

Still, many other economists aren’t ready to embrace these ideas.

Alan Auerbach, an economist at the University of California at Berkeley, says the MMT view “is just silly” and could lead to unwanted or unexpected inflation.

Meantime, Greece and Italy are two recent examples of countries that appear to have hit thresholds where high debt loads lead to higher interest rates and economic pain. The U.S. may have such a threshold too, just not yet seen.

Goldman Sachs Group Inc. economists found that countries with higher debt-to-GDP ratios heading into recessions have smaller fiscal responses, and subsequently worse growth outcomes, though countries that issue debt in their own currency—such as the U.S.—appear to be less affected.

By continuing to run large deficits, says Marc Goldwein, senior vice president at the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, the U.S. is slowing wage growth by crowding out private investment, increasing the amount of the budget dedicated to financing the past and putting the country at a small but increased risk of a future fiscal crisis.

Market interest rate signals can be misleading and dangerous. By blessing the U.S. with such low rates now, he says, financial markets just might be “giving us the rope with which to hang ourselves.”

Updated: 7-6-2019

U.S. Trade Gap Widened In May Despite Tariff Moves

Trade deficit in goods and services jumped 8.4% in May from a month earlier. The U.S. trade gap widened sharply in May despite a new round of tariffs on Chinese goods that took effect in the first half of the month.

The trade deficit in goods and services jumped 8.4% in May from a month earlier to a seasonally adjusted $55.52 billion in May, the Commerce Department said Wednesday.

The gap widened because of the biggest monthly rise in imports in more than four years along with moderate growth in exports amid a cooling global economy. The monthly trade figures provide a window into how U.S. trade is affecting the economy.

Sarah House, a senior economist at Wells Fargo , said that a bigger trade deficit appears likely to shave around half a percentage point off economic growth in the second quarter after adding almost twice that much in the first.

Regarding U.S. trade with China, the bilateral goods deficit widened in May by 12% from the prior month to $30.2 billion, as both imports and exports rose sharply. President Trumpraised tariffs on $200 billion worth of Chinese goods to 25% from 10% on May 10.

Beijing retaliated by increasing levies on $60 billion of U.S. imports. Analysts didn’t expect the tariff moves to have a major impact on the May figures because the moves were unexpected and came midway through the month, giving companies little time to react. The trade dispute between the world’s two largest economies has yet to be resolved.

Though negotiations between Mr. Trump and his Chinese counterpart resumed last month, companies saw the latest round of tariff increases as a sign that trade tensions between the countries are likely to simmer, and executives are scrambling to contain the impact.

Wednesday’s numbers increase the likelihood that foreign trade will drag on broader U.S. economic growth in the second quarter. Capital Economics said it expects gross domestic product growth in the second quarter to come in around 1.5% in annual terms, down from 3.1% in the first quarter.

Trade deficits subtract from GDP, and economists say a narrowing gap in the first quarter made growth appear better than underlying trends in U.S. investment and consumer spending implied.

Ms. House, of Wells Fargo, said the economy is “still relatively strong compared to what’s happening in the broader global economy,” a factor driving imports and the trade deficit.

How the trade balance performs going forward, she said, will in part depend on when Boeing Co. is able to resume exports of its best-selling 737 MAX aircraft, which has been grounded since March due to safety questions.

Civilian-aircraft exports rose in May from April but were down 12% in the first five months of 2019 compared with a year earlier. Many economists expect aircraft shipments to decline further in the months ahead.

Imports rose 3.3% in May from April, the fastest monthly growth since March 2015, to $266.16 billion, the Commerce Department said Wednesday.

The increase was led by a 7.5% rise in automotive imports, to a record $33.23 billion, as well as an 11% jump in crude-oil imports, to $13.02 billion.

Updated: 8-29-2019

Trucking Company Shutdowns Grow As Shipping Market Cools

Carrier failures more than triple in the first half of 2019 from the prior year period as truckers cope with slowing demand.

Trucking company failures are rising as faltering freight demand exposes operators unprepared for a downturn after last year’s red-hot shipping market.

Approximately 640 carriers went out of business in the first half of 2019, up from 175 for the same period last year and more than double the total number of trucker failures in 2018, according to transportation industry data firm Broughton Capital LLC.

This week, Denver-based HVH Transportation Inc. abruptly shut down, stranding about 150 drivers and loads out on the road. The closure adds to a 2019 tally that includes Ohio truckload company Falcon Transport Co. and regional less-than-truckload carriers New England Motor Freight Inc. and LME Inc.

Former HVH Chief Executive John Kenneally said he is negotiating with the carrier’s bank on steps to help get the drivers’ fuel cards reactivated so they can deliver their loads and get home. The company has about 380 trucks, including those tied to a related Canadian company, FTI Transportation, which also shut this week, Mr. Kenneally said. That company also belonged to HVH’s owner, private-equity firm HCI Equity Partners.

The increasing number of closures come as trucking companies that boosted driver pay and plowed last year’s profits into record orders for new equipment now are wrestling with a tougher pricing environment and slackening demand.

In 2018, “demand was so strong, rates were so strong, it was virtually impossible to fail,” said Donald Broughton, Broughton Capital’s managing partner.

Trucking rates stalled out in July, falling 0.1% from the prior year after a 27-month run of annual increases, according to the Cass Truckload Linehaul Index, which measures per-mile pricing for truckload carriers. Prices on trucking’s spot market, where shippers book last-minute transportation, were down nearly 19% last month compared with 2018, according to online freight marketplace DAT Solutions LLC.

That swing has hurt transport operators that shifted more business to the spot market last year to take advantage of surging rates. That also has proved painful for smaller operators that depend more on trucking’s spot market and may not have the leverage big trucking companies have with shipping customers to build higher prices into their contract rates.

Some trucking companies say rising insurance costs also are weighing on the business. Mr. Kenneally said HVH’s monthly insurance bill more than doubled this year, to about $368,000 from $150,000 in 2018.

Some trucking executives believe the recent spate of smaller carrier bankruptcies will give “larger carriers added control and pricing power in the marketplace,” Cowen & Co. transportation analyst Jason Seidl wrote in a research note last month.

Many big operators both bolstered their balance sheets during last year’s freight surge and deepened their ties to shipping customers with a broader array of services.

This week, Iowa-based truckload operator Heartland Express Inc. bought trucker Millis Transfer Inc. for about $150 million. Heartland last month reported its net profit jumped 25.6% in the second quarter despite declining revenue, and cash on the truckload carrier’s balance sheet jumped more than 27% from the end of 2018 to June 30, to $205.6 million.

Truckers Slashed Payrolls In August

The job cuts in trucking came as hiring in manufacturing and other goods-producing sectors remained weak.

Trucking fleets slashed 4,500 jobs last month and the pace of hiring slowed across the logistics field amid signs of tepid growth in the U.S. goods-producing economy.

The pullback in truck payrolls in August ended a four-month expansion, according to preliminary seasonally adjusted employment figures released Friday by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The overall shipping-focused transportation and logistics sector, excluding passenger and sightseeing companies, contracted by 600 jobs.

Courier and messenger companies that deliver packages to homes and businesses added 3,900 jobs, while warehousing and storage businesses, including fulfillment centers that process online orders, added 1,000 jobs in August. Those gains come as a divide between the U.S. industrial and consumer economies has been growing in recent months.

Road and rail carriers focused on industrial transport are grappling with softening shipping demand and a contraction in manufacturing operations that pushes freight through logistics networks.

Broader U.S. employment grew modestly in August, adding 130,000 positions including 25,000 temporary Census workers. The unemployment rate remained at 3.7% for the third straight month and average hourly earnings rose 3.2% from August 2018.

Goods-producing companies contributed just 12,000 jobs, however, and employment in manufacturing rose by only 3,000 jobs. The transportation equipment sector accounted for nearly a quarter of those gains, although truck manufacturers have said they expect production to slow in coming months.

Orders for heavy-duty Class 8 trucks fell 79% in August from the prior year, according to transportation data provider ACT Research. Production rates are dropping as truck makers work through backlogs from 2018. ACT expects equipment makers to build 238,000 units next year for the North American market, a 31% drop in production from the 2019 forecast.

Truck maker Navistar International Corp. will slow production at some of its plants because of declining U.S. and export orders and a falling backlog, finance chief Walter Borst said in a Sept. 4 earnings call.

The company plans to lay off about 136 unionized workers at a Springfield, Ohio, plant that makes medium-duty trucks, said Chris Blizard, president of United Auto Workers Local 402.

A Navistar spokeswoman didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

“If history is a guide there will be layoffs up and down the truck manufacturing supply chain as a result of falling demand, exacerbating the need to draw inventories down,” ACT president and senior analyst Kenny Vieth said.

On the road, big trucking companies are signaling they are more interested in maintaining pricing leverage gained amid surging demand in 2018 than in expanding capacity.

Old Dominion Freight Line Inc., one of the country’s largest less-than-truckload carriers, said in a mid-quarter operating update on Wednesday that its average daily shipment count declined by 4% in August from the same month a year ago but that revenue per hundredweight, a measure of pricing, expanded by 6.1%, excluding fuel surcharges.

“We remained committed to our disciplined yield management process,” ODFL Chief Executive Greg Gantt said.

Ramped-up U.S. consumer spending is providing a counterweight to the manufacturing slowdown. Retail sales and personal-consumption expenditures both rose in July.

Demand for local delivery drivers and distribution workers remains strong, with employers having trouble recruiting and retaining staff, said Melissa Hassett, vice president of client delivery for ManpowerGroup Solutions Recruitment Process Outsourcing, a subsidiary of staffing company agency ManpowerGroup Inc.

Last year an extra $1 an hour was enough to attract drivers and warehouse workers, Ms. Hassett said. “Now it needs to be a dollar plus scheduling flexibility or training opportunities,” she said.

Updated: 10-6-2019

Trucking Companies Cut Payrolls For Third Straight Month In September

Trucking company payrolls contracted last month as a manufacturing slump weighed on freight demand while logistics sectors tied to e-commerce notched modest gains.

Truckers cut 4,200 jobs in September, the third straight month of declining payrolls, according to preliminary employment figures the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released Friday. The cutbacks came as carriers slammed the brakes on fleet-expansion plans.

Warehousing and storage businesses added 3,400 workers, meantime, as a sector that includes labor-intensive online fulfillment centers stepped up recruitment ahead of the holiday season. The Labor Department revised its earlier numbers to show warehouse operators gained 1,700 jobs in August after earlier reporting a 1,000-job increase.

Hiring expansion slowed at parcel carriers that deliver packages to homes and businesses. Courier and messenger companies added 3,600 jobs in September.

Overall the U.S. gained 136,000 jobs last month and the unemployment rate dropped to 3.5%, a 50-year-low.

Expanded hiring in health care and business and professional services helped offset weakness in the industrial sector that feeds freight networks. Manufacturers lost a net 2,000 jobs, including 4,100 positions at companies that make motor vehicles and auto parts.

The weakness in the industrial sectors includes manufacturers of trucks. Orders for heavy-duty trucks fell 72% in September from the prior year, when trucking companies flush with cash from the 2018 freight boom raced to expand fleets and replace older equipment, according to research firm FTR.

Daimler Trucks North America LLC this week said it would lay off about 900 workers at two North Carolina Freightliner plants. “The market is now clearly returning to normal market levels,” the company said. “This levelling-off in the market requires us to adjust our production levels to meet the normalized demand and therefore reduce our current build rates and employment levels at these locations.”

The trucking sector now has cut payrolls by 9,600 jobs over the past three months.

Trucking companies that stepped up recruitment last year also are cutting off that hiring pipeline as freight demand softens, said Avery Vise, FTR’s vice president of trucking. “They overshot things a little,” he said. What’s more, “a lot of smaller carriers are going out of business…through August we’ve already lost twice as many for-hire carriers than we lost in the entire of 2018.”

This week Roadrunner Transportation Systems Inc., a large Downers Grove, Ill.-based trucking company, said it plans to cut about 450 jobs, or 10% of its total workforce, as it downsizes its unprofitable Rich Logistics truckload business as part of a broader operational overhaul.

Logistics employers in sectors tied more closely to retail and e-commerce are in expansion mode as they prepare for the holiday peak. The National Retail Federation expects holiday sales to rise by between 3.8% to 4.2% this year, although it warned that slowing economic growth and uncertainty over trade could erode consumer confidence.

Delivery giant United Parcel Service Inc. plans to hire 100,000 seasonal workers this year, and staffing agencies report demand for warehouse labor is outstripping the available supply.

Updated: 11-3-2019

Truckers Hiring Growth Slows On Industrial Weakness

Truckers expand payrolls but warehouse hiring is tepid heading into holiday season.

Truckers edged back into hiring mode last month as overall logistics-sector job growth remained muted ahead of the holiday peak.

Trucking company payrolls grew by 1,300 jobs in October, ending a three-month stretch of job losses, according to preliminary employment figures the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released Friday. The trucking industry added 11,000 jobs between October 2018 and October 2019, the slowest rate of annual growth in nearly two and a half years, as carriers contend with weakening freight demand and a slow start to the fall shipping period.

“We have seen some seasonality and promotional volumes related to the traditional retail peak season but they are well below the frothy conditions of last year,” Mark Rourke, chief executive of Green Bay, Wis.-based trucker Schneider National Inc., said in an Oct. 31 investor call.

Courier and messenger companies added 2,400 jobs last month as hiring slowed among businesses that deliver packages to homes and businesses. United Parcel Service Inc. said it expects to hire nearly 50,000 seasonal workers on Friday, when the parcel carrier was scheduled to hold more than 185 job fairs across the country.

Hiring at warehousing and storage businesses added just 500 additional jobs in a sector that includes online fulfillment centers.

The U.S. economy overall added 128,000 jobs in October despite the General Motors Co. strike, exceeding economists’ expectations. The unemployment rate ticked up slightly to 3.6%.

Auto manufacturing payrolls lost 41,600 jobs last month as thousands of GM workers took to the picket lines and some auto suppliers cut production. Excluding that category, manufacturing hiring expanded in October, when some measures showed modest improvement in the factory sector from the prior month.

Consumers have helped bolster the U.S. economy as industrial growth falters, with holiday sales expected to rise in a range of 3.8% to 4.2% this year, according to the National Retail Federation. Household spending increased heading into the fourth quarter, though at a slower pace than last year.

The divergence between the consumer and industrial sides of the economy is rippling through logistics networks that transport parts to factories and move retail goods from ports to warehouses and stores.

Several trucking companies have reported declining third-quarter revenues and profits, citing an oversupply of truck capacity and slipping demand.

Less-than-truckload carrier YRC Worldwide Inc. said the General Motors strike contributed to depressed volumes at its regional trucking units. YRC reported a 3.6% decline in quarterly revenue, to $1.26 billion, and said LTL tonnage per day fell 4% from a year ago.

“Our focus is on pricing for profit and using internal cost controls to weather the storm until we get back into a more normalized tonnage environment,” YRC Chief Executive Darren Hawkins said in a Thursday call with investors.

Updated: 12-9-2019

Trucker Celadon Group Files for Bankruptcy

Debt-laden truckload carrier to shutter operations, explore sale of its separate Taylor Express business.

Celadon Group Inc., one of North America’s largest truckload carriers, said Monday it filed for chapter 11 bankruptcy protection and will wind down its business operations.

The Indianapolis-based firm has been trying to turn around its business in the wake of an accounting scandal that triggered a management overhaul as the company was seeking to recover from financial problems.

“We have diligently explored all possible options to restructure Celadon and keep business operations ongoing, however, a number of legacy and market headwinds made this impossible to achieve,” Chief Executive Officer Paul Svindland said in the statement.

Celadon owes $293 million in long-term liabilities, according to a sworn declaration filed by the company’s treasurer, Kathryn Wouters. She said Celadon owes $138 million in long-term debt, $115 million on capital leases, $7 million in deferred taxes and $33 million to the Justice Department stemming from a federal probe into the company’s accounting. There are also $98 million in current liabilities, Ms. Wouters said.

On a net book basis, Celadon’s assets were worth $427 million as of Sept. 30, according to her declaration.

The company’s bankruptcy proceedings will be funded by an $8.25 million debtor-in-possession facility provided by some of its existing lenders.

Celadon’s Taylor Express business, based in Hope Mills, N.C., will continue to operate while Celadon explores a going concern sale of its operations, the trucking company said in a statement.

Celadon has been under pressure since the U.S. freight market stalled in late 2015 and 2016, with turnaround efforts complicated by another downturn this year. The carrier was laboring to recover from a failed bet on its truck-leasing business and a related accounting scandal that tanked the company’s stock and led to the indictment last week of its former chief operating officer and chief financial officer on multiple accounts of fraud.

In April, Celadon agreed to pay $42.2 million to settle fraud claims after filing false financial statements and lying to auditors in efforts to hide losses of its aging trucking fleet.

The carrier got into difficulty after rapidly expanding its former truck-leasing division Quality Companies LLC, which was at the center of the accounting scandal. The expansion marked a big bet on truck-leasing in the years leading up to a 2016 trucking slowdown in the trucking market.

The company hasn’t filed financial statements since February 2017 and is working to restate several years of its results extending back to its fiscal year ended June 30, 2014. It received $165 million in new financing in August, part of it from a shareholder identified in securities filings as Luminus Energy Partners Master Fund Ltd. who retained warrants to buy an up to 49.9% stake in the business.

In August Celadon also brought in Richard Stocking, the former leader of truckload-market leader Swift Transportation Co. , to assist in the recovery effort.

The company’s stock was delisted from the New York Stock Exchange last year.

Transportation research company SJ Consulting Group listed Celadon as the 16th largest U.S. carrier in the truckload sector, the largely industrial sector in which operators haul full-truck shipments to sites such as distribution centers and factories. Celadon counted $762 million in revenue in 2018, an 11% decline from $856 million in the previous year, according to SJ Consulting, a drop that came despite a booming freight market that lifted earnings at other carriers.

Trucking company failures have jumped this year, reaching 795 shutdowns in the first three quarters of 2019, more than three times the total number of trucker failures for the same period in 2018, according to transportation industry data firm Broughton Capital LLC.

Most of this year’s failures involved small-to-midsize operators—the average fleet size was 30 trucks—but some big carriers have also been swept out of business.

New Jersey-based New England Motor Freight Inc., one of the Northeast’s largest trucking companies, filed for bankruptcy in February and liquidated its fleet. Jack Cooper, one of North America’s biggest auto haulers, filed for chapter 11 bankruptcy in August in an attempt to slash the company’s debt and reduce its worker pension obligations.

Uncertainty for drivers

Kevin Williams, an independent contractor who hauls for Celadon, said the company sent a message to drivers late Sunday “and told us to deliver the loads to their destinations and they would give us information as to where to drop the trucks off and we would be paid.”

Celadon driver Rashard Anderson said Sunday that he went to the company’s Indianapolis terminal Saturday night and was told to “go home and sit tight until Monday morning.”

Another driver, José Fraser, said Sunday that his onboard computer had stopped working. He said he was headed back home to Oklahoma City with an empty truck and is worried he won’t be paid.

Student driver Felecia Moore of Detroit was at a driver training course at a Celadon facility in Indianapolis on Saturday when students were told to pack their bags and go to the company’s terminal. “That’s when we saw other trucking company recruiters outside of the welcome center, trying to recruit us,” she said on Sunday.

Ms. Moore said Monday that company officials told about 50 students at the terminal that the court has ordered a lockdown, and said the company is trying provide trainees with bus tickets home.

Updated: 1-11-2020

Parcel Carriers, Truckers Slashed Jobs In December

Delivery and warehousing companies expanded payrolls over the full year at the slowest rate since 2013.

Transportation companies slashed jobs in December, as logistics providers that are focused on e-commerce fulfillment retrenched and truckers pulled back in response to slowing industrial freight demand.

Courier and messenger companies cut 9,400 positions last month, ending an eight-month stretch of growth for operators that deliver packages to homes and businesses, according to seasonally adjusted preliminary employment figures the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released Friday.

Overall, parcel carriers added 23,200 jobs last year. It was the lowest annual increase since 2013 in a sector that includes delivery giants United Parcel Service Inc. and FedEx Corp., companies that have invested billions to automate their operations as e-commerce volumes swell.

Trucking payrolls also declined, losing 3,500 jobs in December. That capped a challenging year for transport companies that are resetting operations as the shipping market has cooled and U.S. factory activity has softened.

The trucking sector gained just 2,200 jobs last year compared with 44,100 in the freight boom of 2018, when carriers rushed to ramp up services in the face of strong economic growth and tight trucking capacity.

Warehousing and storage operators lost 2,200 jobs in December as growth tempered in a sector that includes increasing numbers of fulfillment centers where workers pick, pack and ship online orders. Warehousing payrolls grew by 30,500 last year, the slowest annual increase since 2013.

The weak employment figures reflect both the tight labor market and the influence of slowing industrial demand on warehousing and transportation operations not tied to the booming e-commerce market, said Michael Stull, senior vice president of Manpower North America, a subsidiary of staffing company ManpowerGroup Inc.

“As trade slows down you’re getting less stuff coming into the ports,” he said. Slowdowns in agricultural exports, for instance, ripple through supply chains, dampening purchasing of new farm equipment and paring back demand for storage and transport.

Overall, the U.S. economy added 145,000 jobs in December, fewer than expected but still capping a 10th straight year of payroll gains. Employers added 2.11 million jobs last year, compared with 2.7 million in 2018. The unemployment rate last month remained at 3.5%.

Payrolls for companies that feed freight through logistics networks were less bright. The manufacturing sector lost 12,000 jobs in December, though it charted modest gains for the year, adding 46,000 jobs compared with 264,000 in 2018. Mining employment fell by 7,600 last month and declined by about 24,000 for the year.

Slowing industrial demand and business uncertainty around trade have cast a shadow over the shipping market and demand for transportation equipment. Orders for heavy-duty Class 8 trucks, the big rigs that haul freight long distances, fell nearly 64% in 2019 after a record surge in 2018, according to industry data provider FTR.

“Freight growth has almost stalled out,” said Don Ake, FTR’s vice president of commercial vehicles.

The group forecasts that truck movements of goods will grow only about 1% this year. “That’s why you’re seeing a slight shakeout in the market,” Mr. Ake said.

Nearly 800 trucking companies shut down in the first three quarters of 2019, more than three times the number of failures the year before, according to transportation industry data firm Broughton Capital LLC. The biggest fleet to close this year was Celadon Group Inc., one of the largest North American truckload carriers, which in December sought chapter 11 bankruptcy protection after failing to turn around its business.

Updated: 4-8-2020

Ocean Carriers Idle Container Ships In Droves on Falling Trade Demand

More than 10% of the global boxship fleet are anchored as Western markets lock down against the coronavirus pandemic.

Container ship operators have idled a record 13% of their capacity over the past month as carriers at the foundation of global supply chains buckle down while restrictions under the coronavirus pandemic batter trade demand.

Maritime data provider Alphaliner said in a report Wednesday that shipping lines have withdrawn vessels with capacity totaling about 3 million containers in efforts to conserve cash and maintain freight rates.

Alphaliner, based in Paris, said more than 250 scheduled sailings will be canceled in the second quarter alone, with up to a third of capacity taken out in some trade routes. The biggest cutbacks so far have hit the world’s main trade lanes, the Asia-Europe and trans-Pacific routes.

“No market segment will be spared, with capacity cuts announced across almost all key routes,” the report said. “While the larger ships will be cascaded to replace smaller units on the remaining strings, carriers will be forced to idle a large part of their operated tonnage.”

The cutbacks are hitting the network of businesses, from ship-financing to vessel-leasing companies, behind maritime supply chains.

“We had two ships given back to us three months early in the past week alone,” said a Greek owner, who charters his fleet of 19 vessels to some of the world’s biggest liners. “Instead of boosting capacity for the peak summer season, we are discussing where to lay up our ships. It’s a crazy time.”

Ship brokers say giant ships that move more than 20,000 containers each now are less than half full.

“It will change when American and European consumers get out and start spending again, but this can be weeks or months away,” said George Lazaridis, head of research at Allied Shipbroking in Athens.

Sailing cancellations grew from 45 to 212 over the past week, according to Copenhagen-based consulting firm Sea-Intelligence. The “blanked” sailings are stretching into June, indicating operators expect the traditional peak shipping season, when retailers restock goods ahead of an expected buildup in consumer spending in the fall, will be muted this year by the lockdowns extending across economies world-wide.

France’s CMA CGM SA, the world’s fourth-largest container line by capacity, said this week it is idling 15 ships because retailers are pulling back orders over falling demand from European and American consumers.

The decision to idle, or “lay up,” ships is a difficult option for owners, as the vessels continue to generate costs without offsetting income.

There are two ways to idle ships. In a “warm layup” vessels are anchored and staffed, ready to go relatively quickly when demand resumes. This means saving on operating costs such as fuel but continuing to pay crew salaries and insurance fees and make charter payments.

In a “cold layup” a skeleton crew is kept on board for general maintenance but most of the ship’s systems are shut down. Returning the ship to service can cost millions of dollars and requires extensive testing to certify that the ship is safe to sail.

Many owners choose to lay up bigger vessels in Southeast Asia, mostly in Malaysian and Indonesian waters.

“It’s cheaper to book sea space compared to other parts of the world and ships can be deployed easily on the Asia-to-Europe trade route when things get back to normal,” Mr. Lazaridis said. “But laying up ships for an extended period is a mortal danger for any operator.”

Updated: 4-22-2020

For America’s Small Truckers, Demand Is ‘Falling Off A Cliff’

Small operators critical to supply chains are heavily exposed to a deepening downturn.

Tony Singh has spent much of the past month working the phones to find shipments to get his trucks back on the road. So far, the owner of a small Richmond, Va.-based trucking company has come up dry.

“There’s no freight, no freight at all,” said Mr. Singh, the owner of Sam Trucking LLC.

Loads that would have paid $1,000 last month, when a rush to restock grocery stores briefly lifted business, now fetch $300 or less, he said. That isn’t enough to cover the pay for drivers, fuel and other costs for his seven-truck fleet which is now sitting parked.

“Nobody can survive six months like this,” Mr. Singh said. “How can I pay my guys, the payments on trucks, the insurance?”

Sam Trucking is among thousands of small trucking companies that move the vast majority of the goods in U.S. freight markets. With light cash flow, limited reserves and uncertain access to credit, many of those carriers now are struggling under an upheaval in shipping markets created by lockdowns on economic activity meant to control the coronavirus pandemic.

Trucking companies with six or fewer trucks made up more than 90% of the carriers in the nearly $800 billion U.S. trucking market in 2018, the most recent year for which figures were available, according to industry group the American Trucking Associations.

Such operators also accounted for a significant share of the more than 1,000 trucking companies that shut down last year as freight demand faltered, according to transportation industry data firm Broughton Capital LLC. Analysts say small truckers’ slimmer margins may leave many on the edge in 2020.

Fleets of all sizes are getting hit by the downturn, and some big national trucking companies are slashing executive pay and pulling back spending.

Omaha, Neb.-based Werner Enterprises Inc. said last week that Chief Executive Derek Leathers would take a 25% cut in base salary, with other executives reducing pay by up to 15%, the company said in a filing.

“We anticipate a string of bankruptcies across the transportation sector,” Stephens Inc. analyst Jack Atkins wrote in a research note earlier this month. “We believe the next three to five quarters will be an extremely difficult time for small and mid-size carriers and for bigger truckers with limited liquidity.”

Although demand for food, household goods and essential medical supplies has soared, experts say the rush for that business is nowhere close to making up for the lost shipping from the shutdowns of factories and retail stores.

Truckers that aren’t moving food, medical supplies or other essential items “are sucking wind,” said Jeff Tucker, chief executive of Haddonfield, N.J.-based freight broker Tucker Company Worldwide Inc.

“All those carriers that have heavy exposure to automotive and other products not deemed essential are really, really badly hurting now… We’re starting to see pricing well below what it takes to run a truck,” Mr. Tucker said. “That can’t continue.”

Many small trucking companies rely heavily on the spot market, where retailers and manufacturers book last-minute transportation, and where pricing tends to be more volatile than the contract rates big carriers negotiate with shippers.

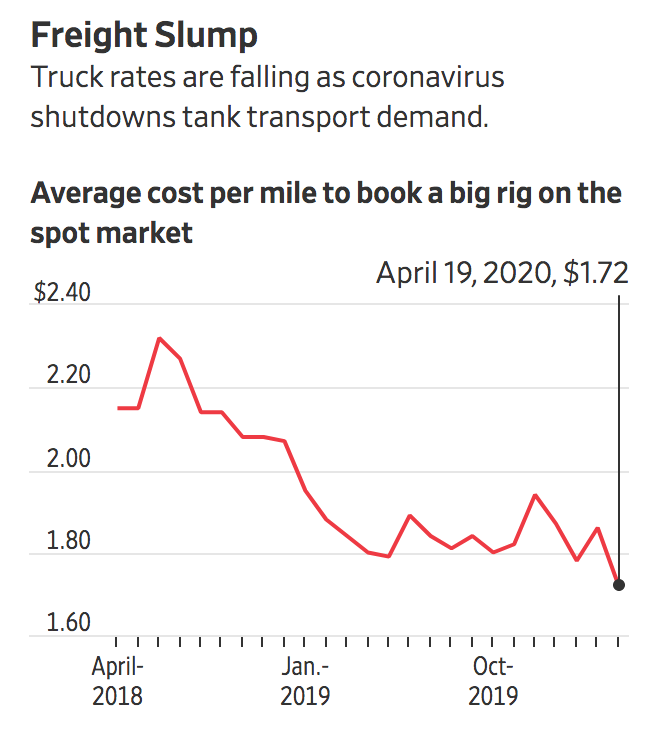

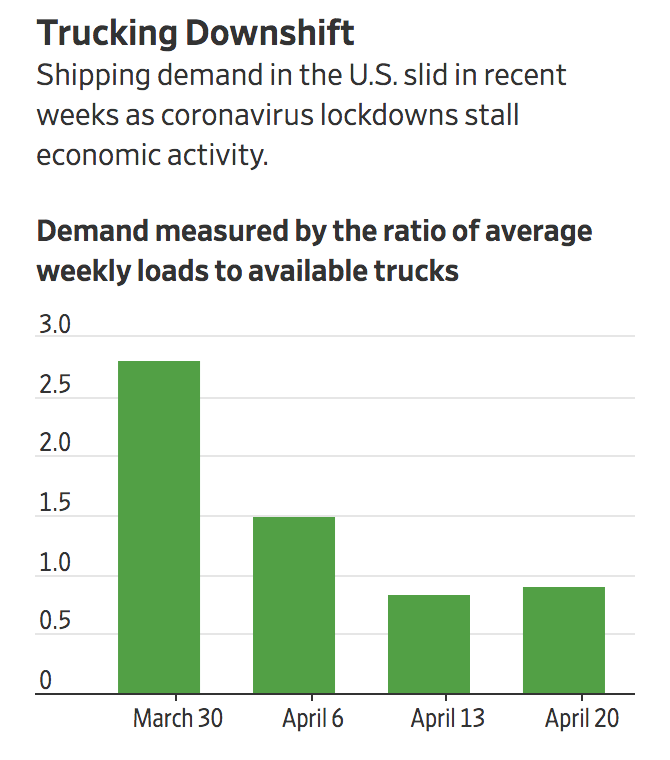

That business is drying up. Demand measured by the ratio of loads to trucks fell 68% to 0.91 for the week ending April 19 from the week of March 29, leaving more trucks looking to move freight than available loads, according to online freight marketplace DAT Solutions LLC. The average spot market price for booking a big rig fell to $1.72 per mile including fuel in the first three weeks of April, down 8% from the average during March.

Demand is “falling off a cliff,” said Todd Spencer, president of the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association, which represents independent truckers.

The group is lobbying for more assistance, including seeking additional funding for disaster and small business aid and asking Congress to waive certain taxes and fees, such as a use tax on heavy vehicles.

“If these businesses are allowed to fail, there will certainly be delays and increased costs across the economy when restarting from this crisis,” Mr. Spencer wrote in an April 14 letter to the heads of congressional committees on small business.

Sam Trucking’s Mr. Singh said he has sought federal disaster assistance but didn’t receive any aid. He doesn’t know if the company will get funding from its application to the Paycheck Protection Program, which last week exhausted its initial $350 billion allocation.

He said some drivers tell him they don’t have money for food and he has tried to help some with small advances when he can. But he also is trying to make payroll, and pay the rent on his office space and mechanic shop.

“We’re not making a single penny,” Mr. Singh said.

Updated: 5-5-2020

Heavy-Duty Truck Orders Plunge To Record Low

The 4,000 orders placed in April came as trucking companies experienced a sharp slowdown in demand.

Orders for heavy-duty trucks in April plunged to the lowest level on record as trucking companies put expansion plans on ice due to upheaval from the coronavirus pandemic.

North American fleets ordered 4,000 of the Class 8 trucks used in highway transport last month, down 73% from April 2019 and 44% from March, according to preliminary estimates from FTR. The transportation research group said it was the lowest reading it has recorded since it began tracking orders in 1996.

Trucking companies canceled or delayed new equipment orders as much of the economy shut down, tanking demand from many industrial and retail customers.

Demand measured by the ratio of loads to trucks fell 66% in April on trucking’s spot market, where shippers book last-minute transportation, according to online freight marketplace DAT Solutions LLC.

The weak market and uncertain outlook have made many trucking companies rein in spending. Last month, Canadian transportation and logistics company TFI International Inc. said it was slamming the brakes on capital spending for its U.S. truckload operations. After the second quarter, “everything has been canceled,” TFI Chief Executive Alain Bédard said in an April 22 call with investors.

“Fleets don’t need a lot of trucks in the short term and they’re unsure what they’ll need in the next few months, so they’re being cautious,” said Don Ake, FTR’s vice president of commercial vehicles.

The pandemic is accelerating a downturn in the heavy-duty truck market since the business reached a high point during 2018 as truckers raced to expand capacity on the back of booming freight demand. Trucking companies ordered a record 53,300 heavy-duty trucks in August 2018, according to FTR.

This April’s pullback in orders came as equipment makers already hit by a sagging market shut down or slowed production because of the coronavirus pandemic.

Daimler Trucks North America has suspended production at its plant in Portland, Ore., and two facilities in North Carolina, saying the work had “outpaced the current capabilities of the supply chain.”

Those factories and the company’s facilities in Mexico are scheduled to resume production on May 11, the company said, while two other U.S. plants in North and South Carolina were operating “near full speed.”

Industry observers said resuming production could be hampered by a shortage of parts from factories in the U.S. and Mexico that have shut down since the pandemic began.

“The ramp out of this is going to be arduous,” said Kenny Vieth, president of market forecaster ACT Research, which reported similar results. “You can only build at the speed of your slowest supplier.”

Mr. Ake said the backlog of heavy-duty trucks ordered but not yet built, which was 100,700 units in March, will likely dip below 2017 levels once production resumes. “The industry was going slow anyway, and the backlog will probably go below that 94,000 mark [in 2017] eventually,” he said.

Updated: 7-2-2020

U.S. Treasury To Lend $700 Million To Trucking Firm YRC Worldwide

Government will take a 29.6% equity stake in the company, Treasury says.

The U.S. government plans to lend $700 million in coronavirus stimulus funds to trucking firm YRC Worldwide Inc., in exchange for a 29.6% equity stake in the company, the Treasury Department said Wednesday.

The Treasury said publicly traded YRC qualified for the loan under a provision of the $2.2 trillion law Congress enacted in late March that authorized $17 billion for companies deemed essential to national security.

The loan is by far the biggest the government has extended to a U.S. business outside of the airline industry, and the first loan the government has awarded from a special fund for firms with ties to the Defense Department.

Overland Park, Kan.-based YRC is one of the largest U.S. trucking companies and does substantial business with the Defense Department, delivering food, electronics and other supplies to military locations around the country, as well as serving some 200,000 industrial, retail and commercial customers.

Congress authorized the Treasury to lend up to $46 billion directly to firms hard-hit by the pandemic, including $29 billion for passenger and cargo airlines, and $17 billion for firms deemed essential to maintaining national security. The program aims to help companies maintain staffing levels and is separate from other stimulus efforts directed at smaller businesses.

“This loan will enable a critical vendor to the Department of Defense to maintain significant employment while providing appropriate compensation to taxpayers,” Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said.

YRC generated $4.87 billion in operating revenue last year but has also struggled for years under a heavy debt load. The company employs about 30,000 workers, including 24,000 members of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters. It is the fifth-largest U.S. trucker by 2019 revenue, according to transportation research provider SJ Consulting Group Inc.

The pandemic battered YRC’s business as lockdowns meant to curb the spread of the virus curtailed the flow of freight from YRC’s industrial and retail customers.

The company slashed expenses, laying off and furloughing some workers, and striking a deal with lenders to improve liquidity.

“The hole created by the pandemic was our reason for pursuing the Cares Act loan,” YRC Chief Executive Darren Hawkins said in an interview. While shipping volumes have picked up as more states reopen, he said, “A lot of our exposure was to the heavy industrial side of the economy, which was the last piece to come online.”

The loan to YRC will mature on Sept. 30, 2024, and consists of two $350 million tranches.

The funds will allow the company to cover obligations including three months of missed pension and health-care payments at “roughly $40 million a month,” Mr. Hawkins said. The company will also use the money for equipment and property lease payments, and to make capital investments in its fleet.

In afternoon trading, shares of YRC climbed 68% to $3.12 each.

YRC applied for the loan in late April, under the Cares Act provision for firms critical to national security, “because of our longstanding service in national defense,” Mr. Hawkins said.

In 2018, the Justice Department sued YRC for allegedly overcharging the Pentagon millions of dollars for shipping from 2005 to at least 2013. Mr. Hawkins called the lawsuit “a contractual dispute from over a decade ago” and said YRC has filed a motion to dismiss the case.

The national security funds were once widely believed to be aimed at supporting Boeing Co., but the company decided against applying for federal funds after raising $25 billion from private investors.

One senior Pentagon official in May questioned whether the Treasury’s conditions for the loans aligned with the needs of Defense Department contractors.

Updated: 9-1-2020

Robot Trucks Are Seeking Inroads Into Freight Business

Startup Ike strikes a deal with several truck operators as pressure grows on self-driving ventures to show paths to profits.

As tautonomous trucking edges closer to market, technology providers and their potential customers are testing competing strategies for how driverless big rigs could help them make money in the real world.

Several startups are building out prototype fleets and hauling freight for big shippers that hope autonomous trucks could help cut transportation costs and speed up deliveries.

Other companies with self-driving trucking technology are trying to plug into existing operations, striking agreements with truck makers and large trucking fleets that they believe could eventually buy thousands of autonomous tractors.

Transport operators Ryder System Inc., NFI Industries Inc. and the U.S. supply-chain arm of German logistics giant Deutsche Post AG are working with Ike Robotics Inc., a San Francisco-based startup that plans to offer its automated trucking technology through a software subscription model.

Those fleets, along with others whose names the startup didn’t disclose, are collectively reserving the first 1,000 heavy-duty trucks powered by Ike’s technology, the companies said Tuesday.

New Jersey-based NFI, whose services include port trucking and intermodal truck-rail transport, is evaluating how autonomous trucks would integrate with its dedicated trucking operations moving freight from customers’ warehouses to retail stores.

Self-driving big rigs could handle longer highway portions of those regional runs, such as the 250-mile trip between the Dallas-Fort Worth area and Houston, said NFI President Ike Brown.

Because autonomous trucks wouldn’t be bound by rules that limit most commercial drivers to 11 hours behind the wheel, “We could use that asset, the truck, almost on a 24-hour basis,” Mr. Brown said.

That would lower the costs, making over-the-road service more competitive with intermodal rail-truck service, which is typically cheaper, he said. “I think automated trucking is going to bite into the intermodal market.”

Tapping into big carriers’ logistics networks and operational expertise means Ike can focus on the technology piece—systems engineering, safety and technical challenges such as computer vision—said Chief Executive Alden Woodrow.

“They are going to help us make sure we build the right product, and we are going to help them prepare to adopt it and be successful,” said Mr. Woodrow, who worked on self-driving trucks at Uber Technologies Inc. before co-founding Ike in 2018.

The question of whether autonomous truck businesses will seek to drive around existing operators or work with trucking’s array of equipment suppliers and logistics providers is growing as self-driving technology gets closer to widespread adoption.

As companies show robot trucks can run on roads, they’re under more pressure to show they can operate profitably.

Rival startup TuSimple Inc. is also working with big logistics operators but taking a different approach, bulking up its delivery business moving freight for companies such as grocery and food-service distributor McLane Co. as it builds a planned coast-to-coast autonomous freight network.

Starsky Robotics, an autonomous trucking venture that also ran its own trucking business, shut down this year, citing reasons including “that investors really didn’t like the business model of being the operator.”

Karen Jones, Ryder’s chief marketing officer, said Ike’s business model factored into the decision to work with the startup, along with its approach to safety. “Not operating their own fleet—that’s a win,” she said.

“It’s important to us to work with companies that want to enhance [our capabilities], not compete.”

Some ventures aim to automate trips door-to-door, while others, including Ike, are focused on highway moves with handoffs to human drivers to navigate surface streets, which experts say could provide a faster path to automation.

“Divided highway transportation, that’s the easiest problem to solve and the most challenging for finding drivers,” said Jim Monkmeyer, president of North American transportation for Deutsche Post’s DHL Supply Chain, which is reserving several hundred Ike-equipped trucks.

Still, those vehicles aren’t likely to form big fleets for a while, Ike said.

“It will be several years before automated trucks without drivers are operating commercially, and longer to reach any meaningful scale,” said Mr. Woodrow.

Updated: 5-19-2023

For Truckers, It’s Like The Great Financial Crisis, Only Still Getting Worse

An ultra-cyclical market turns down.

For truck drivers and larger carriers, the current business environment may be headed to a worse place than the one reached during the depths of the Great Financial Crisis.

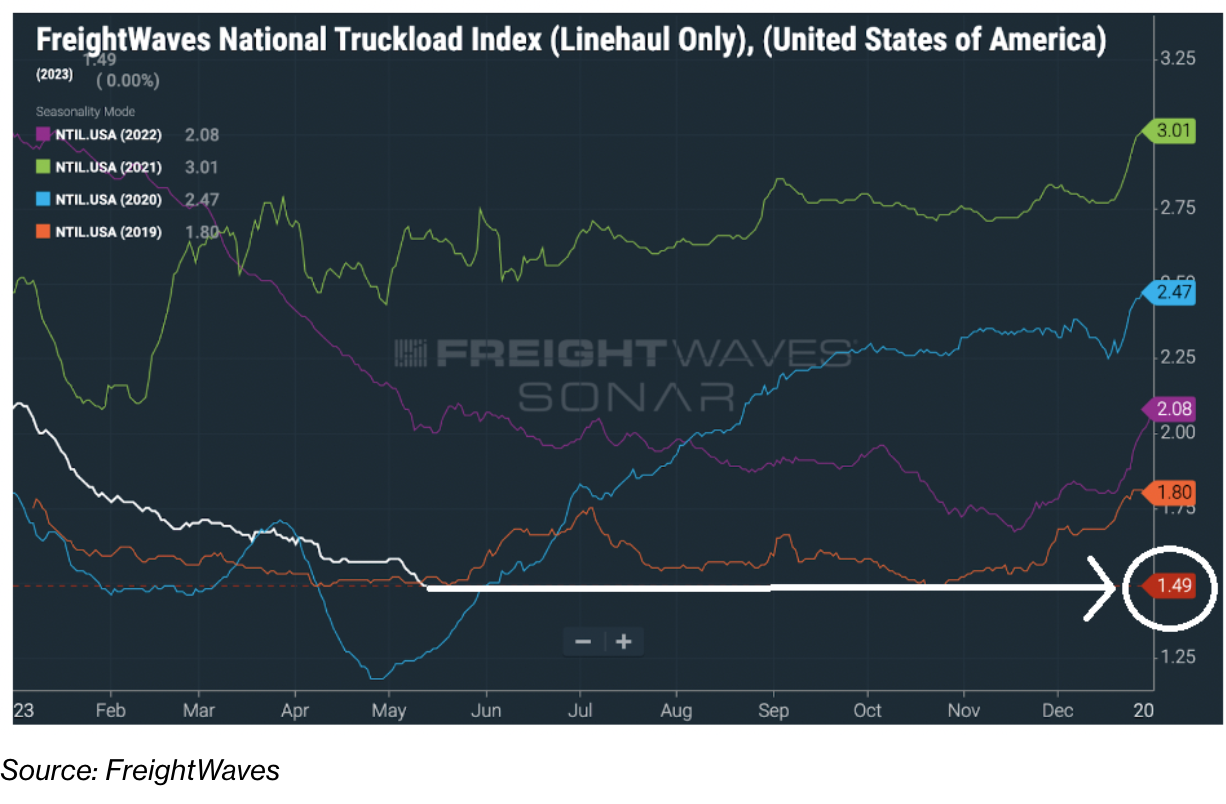

Per-mile rates have been plunging since the Covid-era goods boom brought a surge of new supply onto the market. Combine that with higher maintenance prices, an increase in the cost of capital and other difficulties in operating, and the result is a brutal mix for a notoriously cyclical industry — one that has the potential to be worse than famous trucking downturns experienced in 2019 and in 2008-09.

Trucking’s ultra-low barriers to entry mean the industry tends to be extremely volatile, with thousands of small-scale owner-operators ramping up capacity when carrier rates start to rise.

On the latest episode of the Odd Lots podcast, we spoke with FreightWaves CEO and founder Craig Fuller, alongside FreightWaves editorial director Rachel Premack. They walked us through the tough math facing the industry right now.

The big question for investors is how much of the current downturn has to do with declining demand for goods, which would add to concerns about a looming recession, and how much has to do with the cyclical nature of the industry.

In previous trucking downturns, “not only did you see a slowdown in volume related to the industrial economy, but you also saw an overbuild of capacity,” Fuller says.

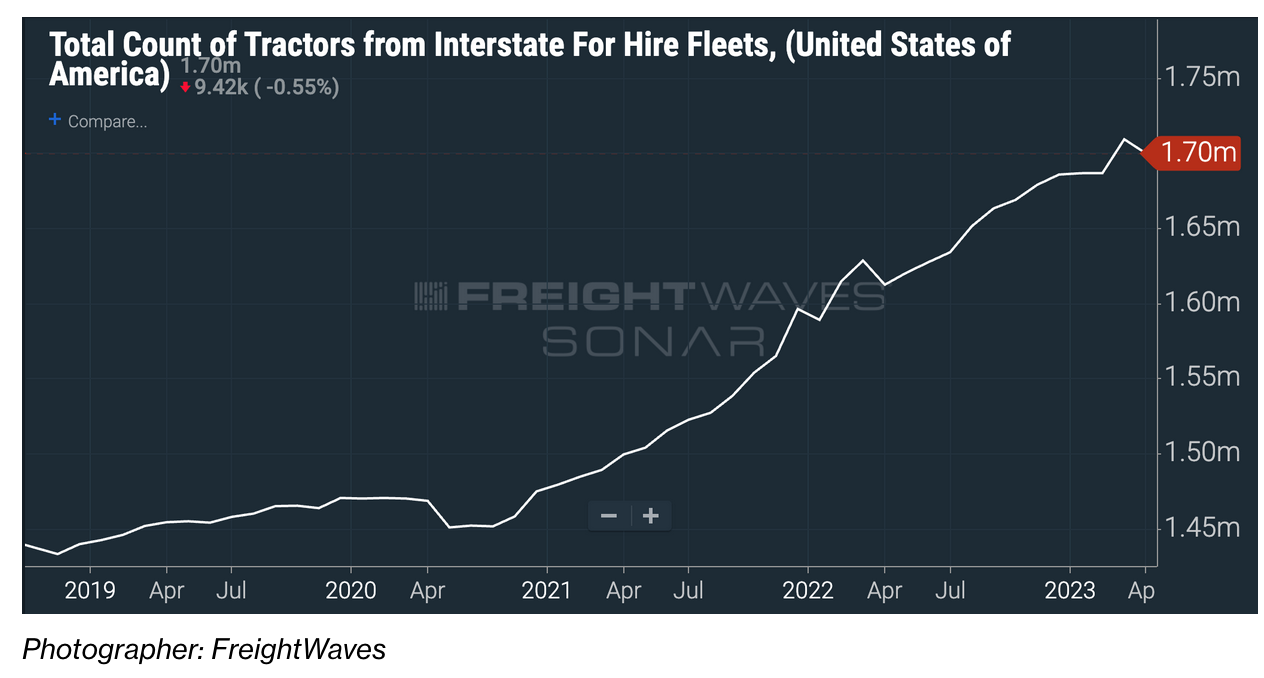

“We’ve seen a massive surge in trucking capacity. Over just the last year, there’s been an increase of as much as 8% of the dispatchable capacity in the market. So in this situation where it’s completely flooded, there’s so much capacity out there.”

One basic measure of how much truck drivers are getting for shifting their loads shows how bad things are right now, with rates falling to as little as $1.49 a mile according to FreightWaves. At the peak of the boom in 2021, drivers were pulling in as much as $3.01 per mile.

The current levels are worse than those seen in 2019, which was one of the worst years ever for the industry.

But the real economics may be even poorer than the chart above shows. With inflation running much higher than it was in 2019, on a like-for-like basis, the current $1.49 on the National Truckload Index is more equivalent to $1.19 a mile, Fuller says.

Meanwhile, operating costs have been increasing, he adds, and “there’s been a mechanic shortage across the country that can handle diesel and work on diesel trucks. That’s a big problem.”

Ironically, the very policies designed to reduce inflation for consumers may be exacerbating stress on the supply side.

“You look at the cost of capital,” Fuller adds. “One of the things to remember is that trucking is a capital intensive industry. It actually has one of the lowest returns on capital of any industry on the planet. But it requires a lot of capital. A lot of these trucking companies finance their working capital and they finance their trucks. What we’ve seen is a pretty dramatic increase in cost.”

Still, the number of trucks on the road has exploded since the Covid pandemic, with drivers chasing those high per-mile rates in 2021 and 2022, and big operators still keen to build out their own capacity and take market share.

“There’s a lot of talk of a truck driver shortage,” says Premack, “And when you keep hearing, ‘Oh, there’s a shortage in this industry. I should jump in, I should, you know, make a quick buck. I should really profit off of this. Too many folks get in and pretty soon after that, what goes up must go down.”

She estimates that some drivers may have pulled in as much as $400,000 in income at the peak of the recent cycle.

But the ability of drivers to command high rates for their services has been shifting, as evidenced by the National Truckload Index and also the tender rejection rate.

Just like airlines, individual drivers or carriers tend to overbook their loads and often have to reject shipper requests. The hotter the market, the more they’ll simply reject a job.

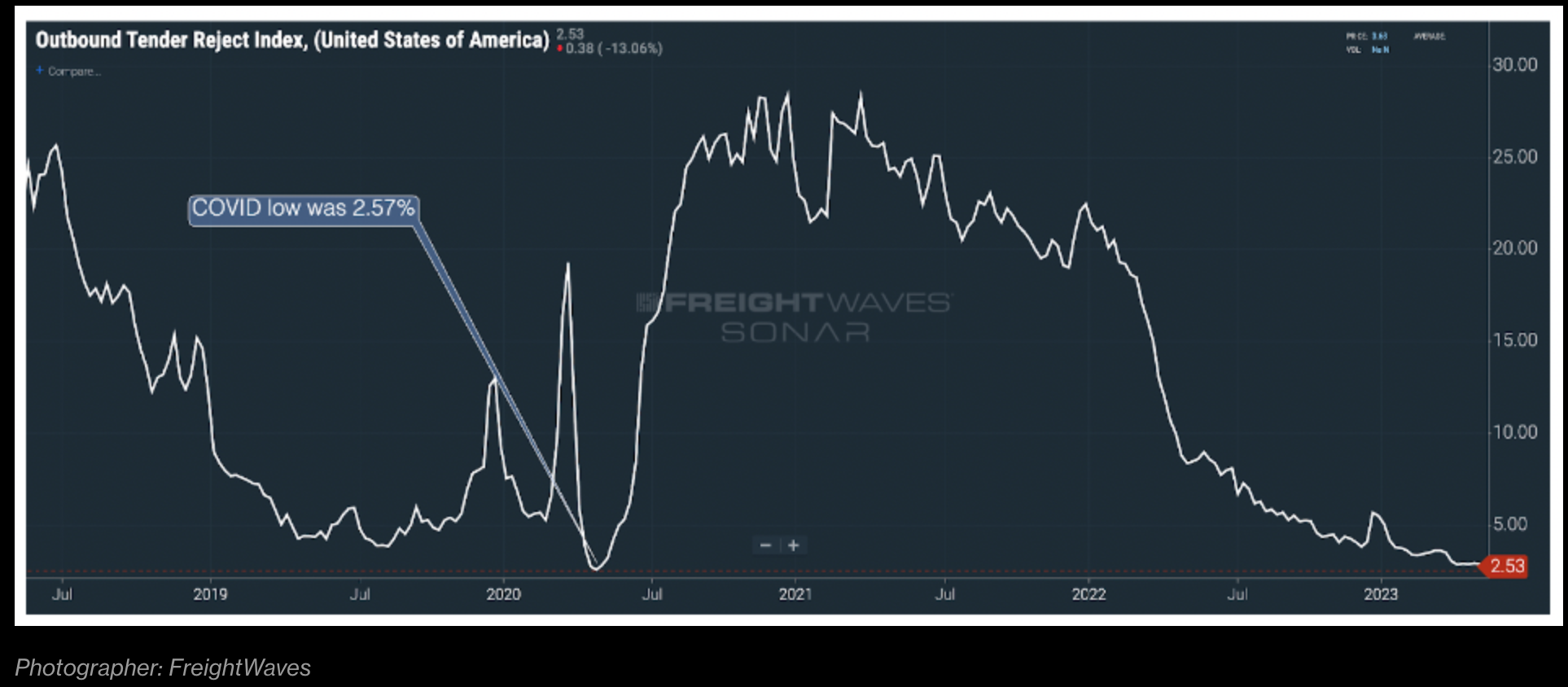

Back in 2021, nearly 30% of outbound tenders were being rejected, in part because capacity was famously so tight. But fast forward to today and we’re in the opposite environment with tender rejections having fallen to below even the lows seen during the Covid pandemic.

This is also the key measure to look at first for the signs of an eventual bottom, according to Fuller.

“The tender rejection data will start to basically turn around and you’ll see it accelerate,” he says. So far though, “we’ve not seen anything in tender rejection data which actually suggests that. We’re still in it for a while. If you listen to some of the larger carriers, they’ll tell you it’s probably going to get better in six months. The second half will be better. I don’t buy it.”

When it comes to how bad this could be, conditions are looking like some of the worst in perhaps 15 years.

“We saw during the last earnings call, the first quarter earnings, Shelly Simpson, the president of JB Hunt — one of the largest trucking companies in the US — she said this market is reminding us of 2009,” Premack says.

“And that’s certainly not something that I’ve ever heard. I’ve never heard a 2008-2009 comparison in the six years or so that I’ve been covering the trucking industry.”

Ultimately what might be needed to rebalance the market is an industry capitulation that results in a large cut to capacity — and there are no signs of that yet.

“This is a situation where it’s going to take a while to get rid of all the excess capacity,” Fuller says. “We have not yet seen a situation where large or mid-size carriers are going out en masse. I don’t think we can call a bottom … until we start to see a real washout of very large companies.”

Updated: 7-30-2023

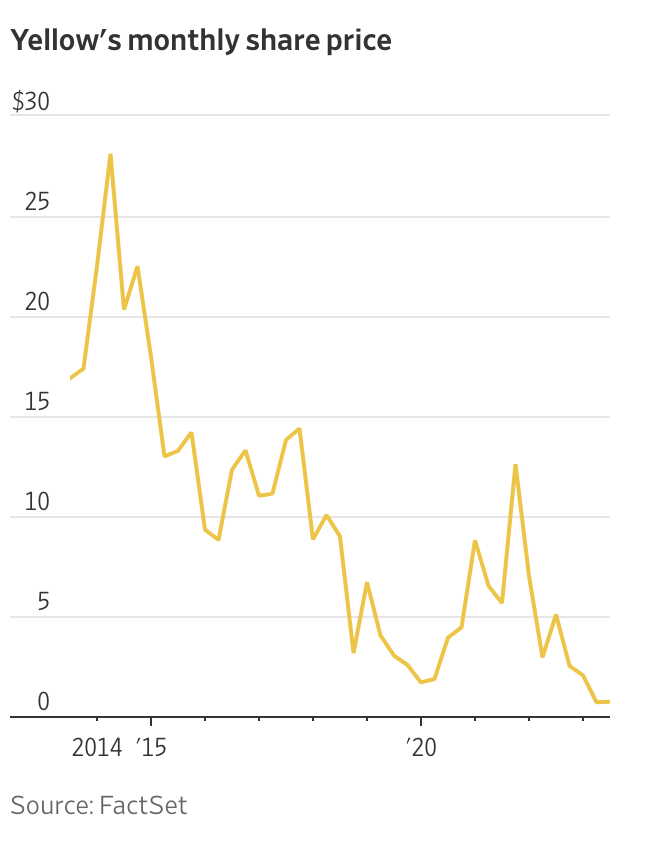

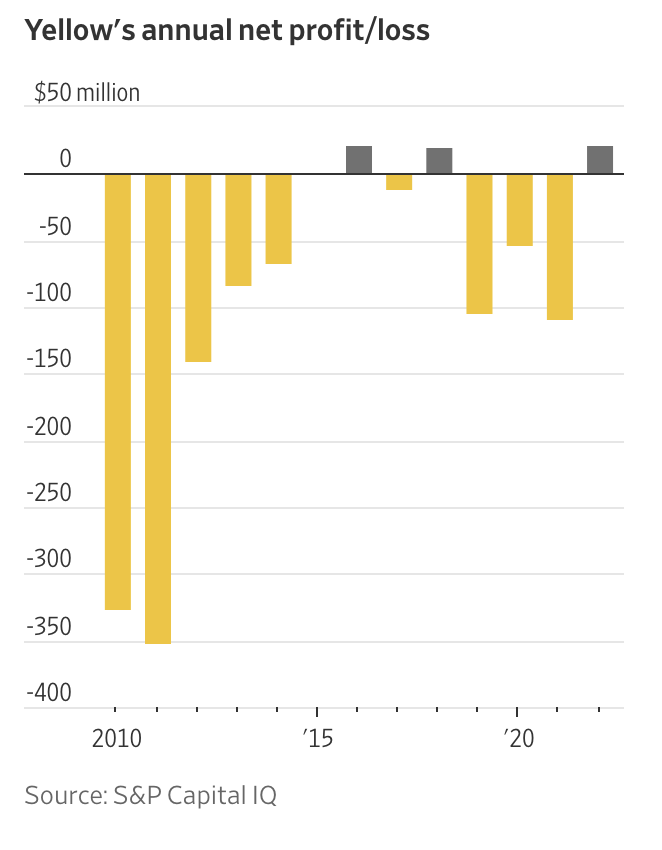

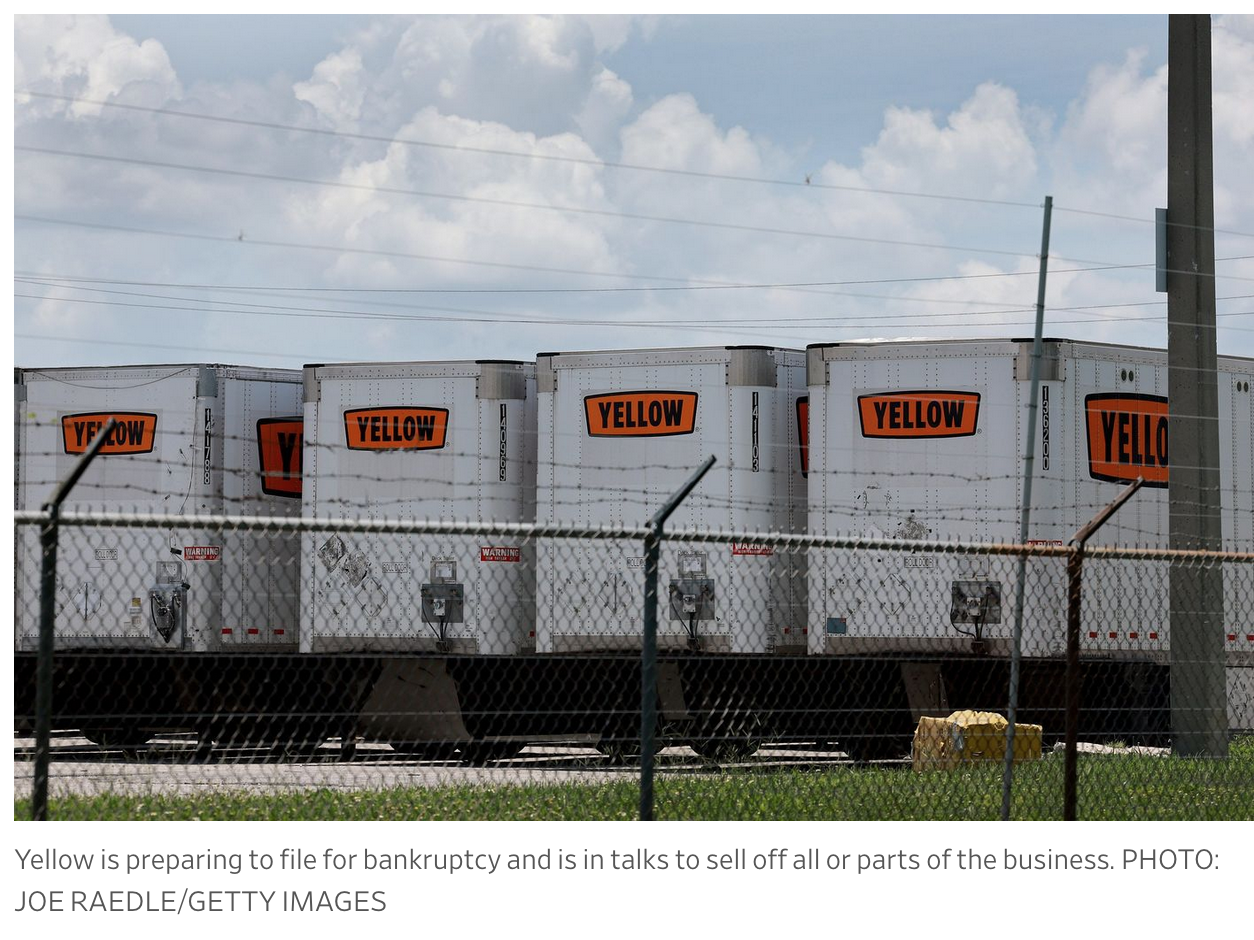

Trucking Giant Yellow Shuts Down Operations

The 99-year-old company with 22,000 Teamsters employees advises customers and workers of shutdown.