Los Angeles And Other Cities Stash Money To Prepare For A Recession (#GotBitcoin?)

“Every year that the recovery lasts, it just makes the pressure around preparedness for a downturn that much more urgent,” said Mary Murphy, who studies rainy-day funds at the Pew Charitable Trusts. Los Angeles And Other Cities Stash Money To Prepare For A Recession (#GotBitcoin?)

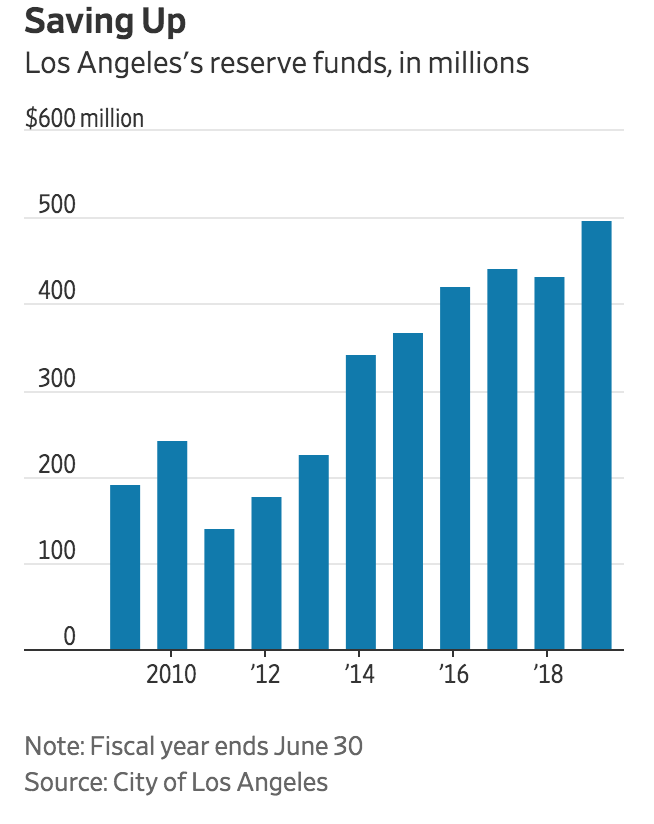

Local officials are feeding their rainy-day funds, hoping to ride out the next slump.

Pressured by declining revenue, local governments around the U.S. shed a half-million jobs in the last recession through layoffs and attrition, according to Pew. Everything from public safety to trash collection to school administration was on the chopping block. Some cities raised taxes and fees, too, but most cut spending to make ends meet.

States commonly use rainy-day funds to smooth the jolt from recessions, which can come quickly when sales- and income-tax revenue plummets. Thirty-one states boosted rainy-day fund balances in the last fiscal year, and 26 have projected increases this year, according to the National Association of State Budget Officers.

States may cut aid to local governments during recessions, and cities still have to balance their budgets, Ms. Murphy said. Many cities don’t lock away money in formal rainy-day funds, but they commonly set aside excess revenue as reserves. The amounts vary widely, though the Government Finance Officers Association maintains that enough money to cover two months of a city’s annual general-fund budget is a good benchmark.

Denver’s policy has been to keep reserves equal to between 10% and 15% of its annual general fund. During the last recession, the city delayed recruit classes for the police and fire departments, put off technology purchases and closed a motor-vehicle department branch. But officials also drew down its reserve by $62 million to soften the blow. The city expects to end 2019 with about $221 million in reserve.

In Las Vegas, city officials are holding more than 50 jobs open to save $6.4 million, out of concerns that the next downturn would only mean cutting those positions. It is also building up reserves, which recently stood at $132 million, 55% more money than it had set aside before the last recession.

“We are trying to position ourselves to be ready,” the city’s finance director Venetta Appleyard said. “We don’t want to be stuck being reactive.”

Cleveland has plumped its rainy-day fund to about $30 million, after adding $12 million since 2017. Even so, finance director Sharon Dumas told the City Council last month she thinks the city needs far more—roughly $160 million—to cover three months of general-fund costs.

Slow revenue growth has made it hard for many cities to rebuild reserves to prerecession levels, S&P warned in a recent report. “Should that rainy day come sooner than later, local governments might find themselves less able to withstand financial pressures while maintaining credit quality,” the report said.

In Philadelphia, officials haven’t put a dime in a rainy-day fund created in 2011, instead focusing on continuing priorities like shoring up its pension fund. But the current administration said it is committed to stashing at least $20 million there in the next fiscal year, starting in July, thanks in part to a record-high $368 million budget surplus. Even so, officials said they would need a $750 million surplus to hit the GFOA’s target.

“I don’t think you could talk to any big-city finance official and have them say they’re not worried,” Philadelphia’s finance director Rob Dubow said.

States Face Crunch If Fed’s Tool Kit Is Limited in Next Recession

Simulation by the Boston Fed shows the central bank’s inability to cut rates by the usual 5 percentage points would disproportionately hit certain states.

BOSTON—When the next recession comes, some states are likely to suffer much more than others if the Federal Reserve lacks ammunition to make economic downturns less severe, new research shows.

In recent downturns, the Fed has cut its short-term benchmark interest rate by about 5 percentage points to stimulate growth. But in the future, that might be impossible because rates are still historically low. The Fed’s benchmark rate is currently in a range between 1.75% and 2%.

“Monetary buffers have been depleted,” said Eric Rosengren, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, which sponsored the conference this weekend where the research was released. A decline in rates over the past decade means the Fed’s recent experience of running out of room to cut them after lowering them to zero will not be “a one-time event,” he said.

Mr. Rosengren and his co-authors, Boston Fed economists Joe Peek and Geoffrey Tootell, ran an experiment that shows how a recession might affect states assuming a traditional monetary-policy response, in which the Fed could cut its short-term benchmark rate by 5 percentage points.

Then they looked at two other alternatives. In both scenarios, monetary policy couldn’t fully respond because the Fed had raised rates to only 2% before the hypothetical downturn. But in the last scenario, regulatory, state and local, and federal fiscal buffers were also depleted because they weren’t built up before the recession.

The results show, unsurprisingly, that the last scenario is the grimmest. But they also show that the effects are distributed unevenly across states—some fare much worse than others when the Fed can’t cut rates as it traditionally has.

States with industries that are sensitive to both the economic cycle and interest rates—think of Michigan, with its heavy dependence on the auto industry—could face a much worse downturn than Midwestern states that are heavy in agriculture, which is less exposed to a cyclical downturn.

State of Policy

New research suggests changes in per capita personal income growth would hit some States much harder depending on how aggressively monetary policy can respond to a recession.

Take the first example, in which monetary policy is able to respond as it traditionally does. Here, 16 states avoid declines in inflation-adjusted-per-capita income, including many Southern states.

In the second scenario, where monetary policy is limited but the other policy buffers are available, all states experience declines in personal income. Midwestern states that depend on agriculture avoid some of the sharpest declines.

The Southern states that manage through the recession in the first simulation fare worse in the second example. In Alabama, for example, per-capita income falls 1.9%, versus nearly no change in the first simulation.

In the final scenario, the Southern states that didn’t see any income loss in the first simulation are “now among the states most severely adversely impacted when all policy buffers are insufficient.” Personal income falls even further, by 2.7%, in Alabama.

Mr. Rosengren highlighted three areas where policy tools, if deployed now, could help compensate for the potential dearth of monetary stimulus.

First, regulators could require banks to raise more capital in good times to prevent tighter lending from exacerbating an inevitable recession.

Second, the federal government could implement fiscal policies that automatically boost safety-net spending, such as unemployment insurance, during downturns.

Third, state and local governments can build up “rainy day” funds to cushion downturns. Unlike the federal government, states generally can’t run budget deficits, which typically leads to spending cuts and layoffs during a recession—a double whammy because private-sector employment and investment is often also shrinking.

Updated: 6-1-2020

Cities’ Next Dilemma: Cut Essential Services or Take On More Debt

Shutdowns dry up local revenues, leaving leaders with no good options to keep cities running.

Cities across the U.S. are hemorrhaging money as the coronavirus pandemic shut down commerce, entertainment and tourism activities that provide much of their revenue.

The shortfalls are hitting cities ranging from struggling towns to thriving metropolises. Nearly 90% of cities expect revenue shortfalls, according to a survey by two advocacy groups, the National League of Cities and the U.S. Conference of Mayors, which polled 2,463 cities and towns that are home to 93 million people.

Cities have long funded core services by capitalizing on their role as gathering places, charging to park in their downtowns, enter through their ports and eat in their restaurants. They are now having to keep running without any clear sign of when those revenues will return to normal levels.

With no good options, city officials are turning to measures that could jeopardize their future, such as borrowing money for operations or cutting police and fire protection.

“It’s a staggering set of circumstances that I don’t think anyone whether it be at the federal level or certainly at the municipal level was prepared to deal with,” said Portland, Maine, City Manager Jon Jennings, who served in the White House’s Office of Cabinet Affairs under President Clinton.

More than half of U.S. cities expect to cut public-safety spending and more than a quarter plan to lay off workers, according to an April survey by the two advocacy groups.

Portland, the biggest city in Maine with a population of 66,215 and a general fund operating budget of $207 million, is expecting shortfalls in the revenues it collects from downtown parking, parks and recreation programs. With far fewer arrivals to the local airport, rental-car companies aren’t registering new vehicles, eroding one of the city’s biggest revenue streams. Fees from cruise ships typically amount to $3.6 million a year: This year the city is expecting nothing.

To save about $150,000 a week, the city is furloughing workers and freezing some spending. Finance officials have torn up their projections for a balanced budget next year and are forecasting a potential shortfall equivalent to the salaries of more than 200 police, fire, public works and other city staff unless there is a significant recovery.

Meanwhile, annual bond payments are increasing 8% to $45 million as Portland works to pay back money borrowed to cover its pension obligations to police, firefighters and other public workers, and to update the 234-year-old city’s infrastructure.

Congress has authorized $150 billion in aid to state and local governments to cover costs related to Covid-19, but that aid can’t be used to replace lost government revenues.

Federal lawmakers also laid out another option for large cities: spending now and paying later. Congress gave $454 billion for the Treasury to use to backstop losses in Fed lending programs, and the Treasury has committed $35 billion of that money for a central bank effort to backstop debt with maturities of up to three years issued by states and large cities and counties—at last-resort interest rates.

Separately, New York state Senate Finance Committee Chairwoman Liz Krueger this month introduced a bill that would allow up to $7 billion in long-term borrowing for operating costs by New York City.

Debt has long functioned as an escape hatch for cities, because they are often limited in their taxing abilities by state law or the need for voter authorization. A December study of 25 major cities by Moody’s Investors Service found their debt and retirement costs amounted to a median 23% of revenues, a share analysts described as moderately high.

New Haven, Conn., is trying to manage the loss of revenues from parking tickets, building permits and property transfers in a budget stretched thin by debt. The city of about 130,250 spends about 21% of its operating budget on bond and retiree-benefit payments after years of borrowing and paltry pension-fund

More than half of city property is owned by nonprofits, mostly Yale University, that don’t pay property taxes, according to city financial reports. Kicking costs down the road enabled New Haven to hold down taxes on other residents while investing in the local school system, where around half of students are low-income, and help support a shelter system for its significant homeless population.

“I think it’s an easy decision for people to make,” said New Haven Mayor Justin Elicker, who was elected last year after pledging to stop pushing the city’s obligations onto future generations. He said he intends to keep that promise even though “that means we’ll have to make some difficult decisions in the coming years.”

Peoria Mayor Jim Ardis hasn’t made the same promise. In the past seven years, the central Illinois city of 110,417 has lost nearly 5% of its population along with the headquarters of global equipment manufacturer Caterpillar Inc. Debt and retirement-benefit payments have grown to 31% of the budget, as the shrinking city has strained to cover a yearly increase in pension contributions.

In an attempt to make up for past underfunding and mitigate losses from the financial crisis, cities nationwide have been increasing deposits into pension coffers even after many saw revenue declines last year. Total retirement contributions by 49 of the nation’s largest cities doubled between 2007 and 2018, according to data from the Boston College Center for Retirement Research.

“We were really struggling working our tails off to get a balanced budget and then to have this Covid thing come up—our hotel taxes are down 65%, our restaurant taxes are down 35%, income taxes, sales taxes, every revenue stream that a community of our size depends on to operate, everyone of them is hemorrhaging,” Mr. Ardis said.

The city is considering cutting 94 positions, including 28 police officers’ jobs, and contemplating adding to the city’s massive debt burden by issuing a long-term bond to fund operations.

But turning to the bond markets isn’t working as well as it once did, as fearful investors are demanding more compensation to hold risky debt.

When the Los Angeles suburb of Ontario attempted in mid-March to borrow $340 million to cover its debt to the state public-worker pension fund, it ended up canceling the deal for lack of interest. By the time Ontario sold a downsized $237 million deal this month, the additional interest investors demanded to hold low-investment-grade taxable 30-year bonds compared with AAA debt had increased more than 30% from when the city filed its borrowing plans March 2, according to Refinitiv.

State law generally prohibits California local governments from raising property-tax rates except to finance voter-approved debt, so cities like Ontario often depend on the type of revenues that Covid-19 shutdowns affected first, such as taxes on hotel stays.

Some cities have nowhere left to turn. Hawaiian Gardens, a 14,159-person town on the outskirts of Los Angeles County, collects much of its revenue from the local casino, also a major employer, said Lucie Colombo, the city clerk and president of the city’s management chapter of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees Local 36.

“Without it coming back, I expect that the city will declare bankruptcy,” Ms. Colombo said about the casino. She recently received notice that she could be laid off.

Los Angeles And Other,Los Angeles And Other,Los Angeles And Other,Los Angeles And Other,Los Angeles And Other,Los Angeles And Other,Los Angeles And Other,Los Angeles And Other,Los Angeles And Other,Los Angeles And Other,

Related Articles:

Recession Is Looming, or Not. Here’s How To Know (#GotBitcoin?)

How Will Bitcoin Behave During A Recession? (#GotBitcoin?)

Many U.S. Financial Officers Think a Recession Will Hit Next Year (#GotBitcoin?)

Definite Signs of An Imminent Recession (#GotBitcoin?)

What A Recession Could Mean for Women’s Unemployment (#GotBitcoin?)

Investors Run Out of Options As Bitcoin, Stocks, Bonds, Oil Cave To Recession Fears (#GotBitcoin?)

Goldman Is Looking To Reduce “Marcus” Lending Goal On Credit (Recession) Caution (#GotBitcoin?)

Your Questions And Comments Are Greatly Appreciated.

Monty H. & Carolyn A.

Go back

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.