Investors Create Cash Shortage As They Sell Everything From Treasurys To Gold (#GotBitcoin?)

A rush for cash shook the financial system Wednesday, as companies and investors hunkered down for a prolonged economic stall, taking the recent market turmoil into a new, more troubling liquidation phase. Investors Create Cash Shortage As They Sell Everything From Treasurys To Gold (#GotBitcoin?)

Investors sold nearly everything they could in the most all-encompassing market drawdown since the darkest days of the 2008 financial crisis. Short-term money markets at the heart of the financial system were strained and large companies have drawn heavily on credit facilities while they have them.

The selling engulfed stocks, sending the Dow Jones Industrial Average down 1,338.46 points, or 6.3%, to 19898.92, its first close below 20000 in more than three years. The blue-chip index, which dropped more than 2,300 points earlier in the session, has fallen by about a third in just the past month.

Wednesday’s selloff crushed shares of companies as varied as airlines, restaurants, banks and retailers. The declines showed the extent to which investors are worried that the novel coronavirus pandemic—which has already forced airlines to cut flights and businesses to close—could send the economy into a recession.

Shares of Boeing Inc. tumbled 18%, while stock in Citigroup lost nearly 10% in value. A drop of more than 20% in the price of oil slammed shares of energy companies. Exxon Mobil Inc. fell 10% and has halved so far this year.

Several stocks fell so sharply that exchanges had to temporarily halt trading in them. One such stock, Alaska Air Group Inc., tumbled 23% Wednesday. Olive Garden owner Darden Restaurants Inc. slid 19%. Coty Inc., whose beauty portfolio includes Sally Hansen, dropped 31%.

In debt markets, the sell-everything approach drove down prices of safe investment grade bonds and government debt alongside stocks and commodities of nearly all stripes. Normally, when investors turn away from risky assets, they buy safer government debt—or if they are really frightened, gold. Investors appear to be putting their trust in only the shortest-term government bonds or cash.

“When even silver and gold are getting crushed, that’s a panicked drawing of liquidity,” said Rob Arnott, founder of California-based investment firm Research Affiliates. “In the U.S., you can’t find toilet paper anywhere: This is the capital markets equivalent of that.”

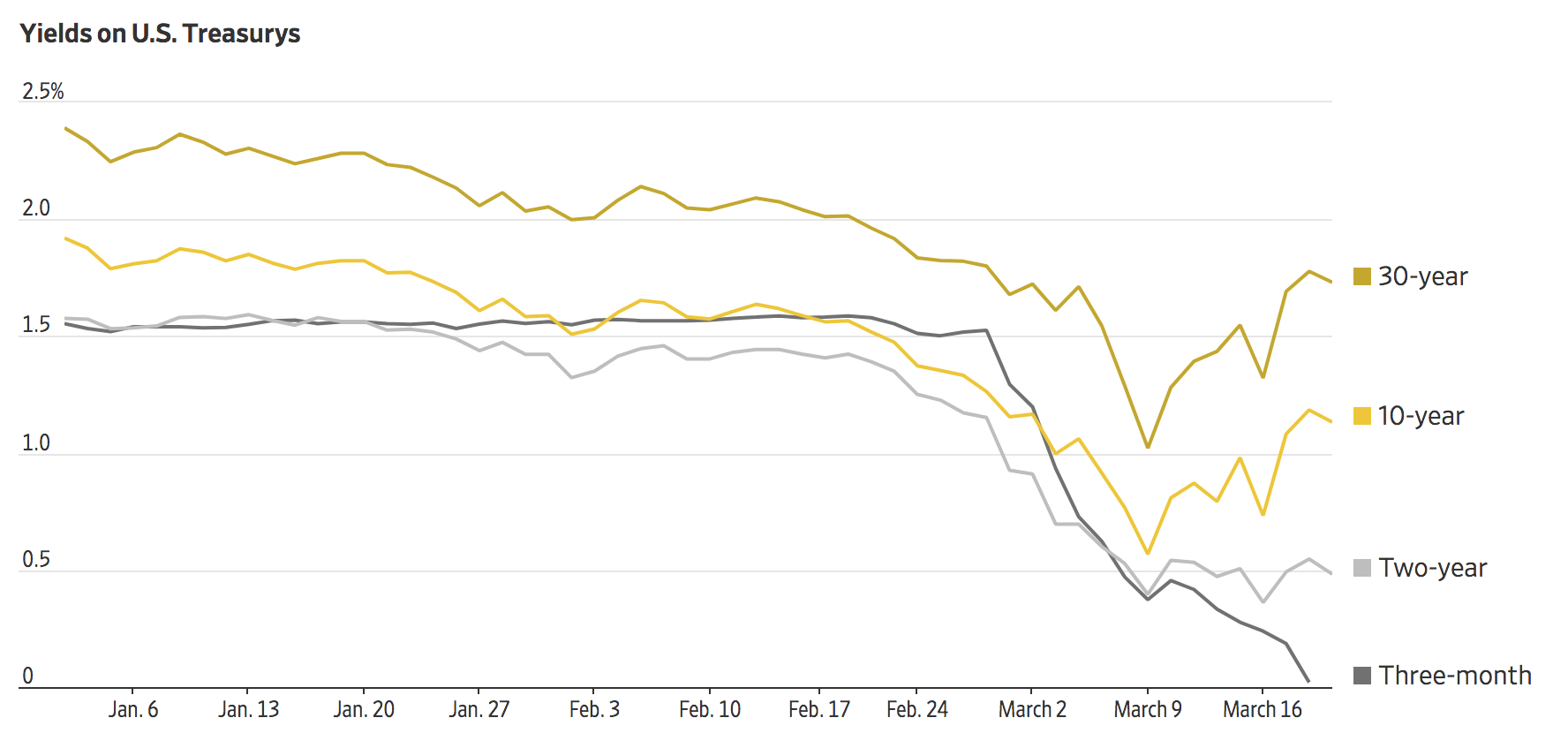

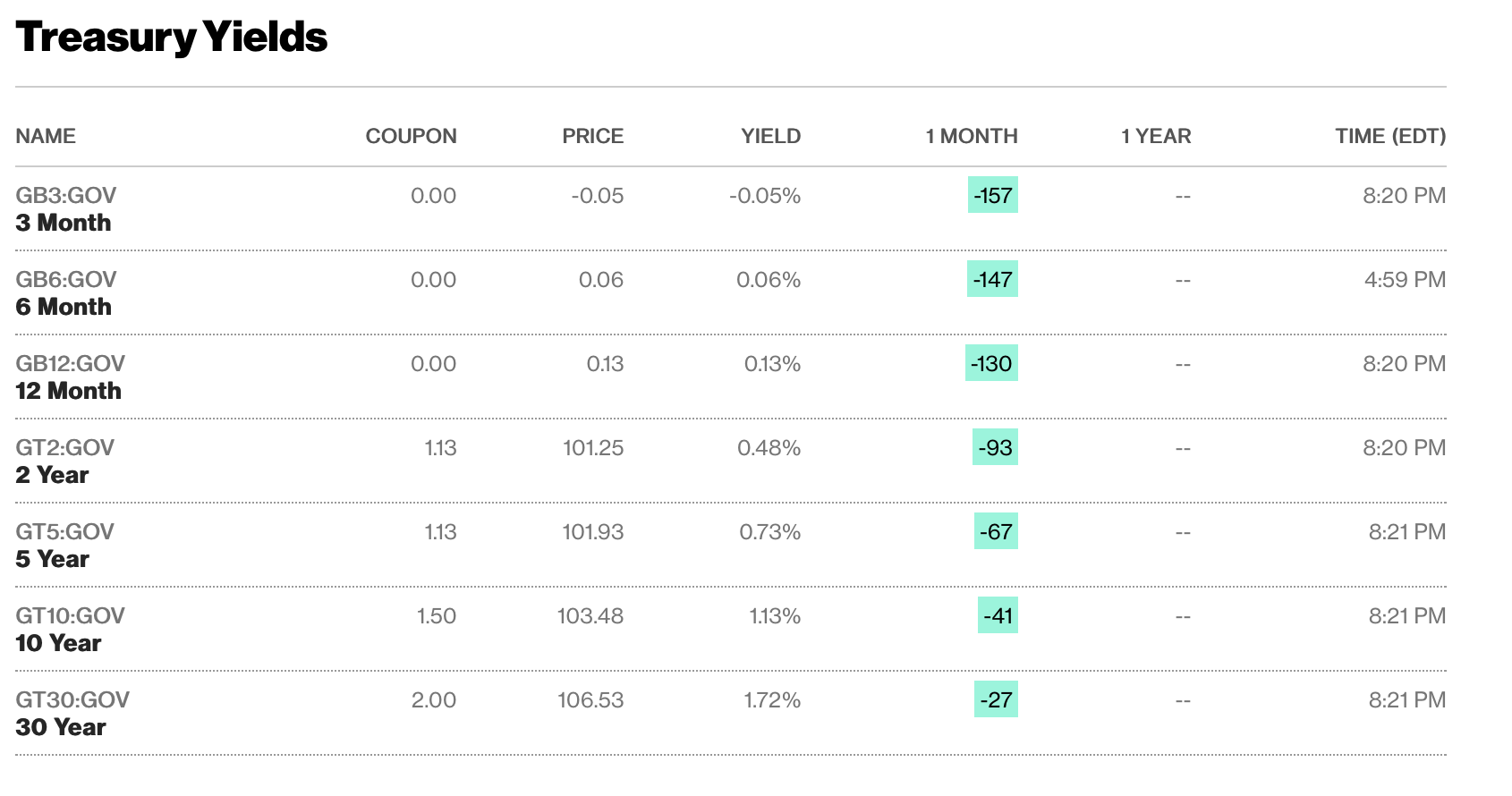

Yields on one-month U.S. Treasury bills, a close equivalent to cash, fell to as low as 0.0033% from 0.31% at the start of the week, their lowest level in several years.

“There are very few places to hide. The tightening in financial conditions is happening across markets,” said Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou, global markets strategist at JPMorgan Chase & Co. He pointed to strong selling of bond funds that own the debt of the safest big companies, which is causing corporate borrowing costs to rise despite central bank efforts to do the opposite.

Another factor pushing government bond yields higher: As investors dash for safety, they are contending with a potential massive new supply of government bonds that will be necessary to fund stimulus measures, including $1 trillion of spending discussed in Washington Tuesday. In the simplest terms, a greater supply of bonds should cause prices to fall and yields to rise.

The rush to cash, meanwhile, has put strain on money markets in the U.S. and globally. The difference between the yield on the three-month Treasury bill and interbank lending rates, known as the Ted spread, jumped above 1 percentage point, according to FactSet, a level not seen since early 2009. In good times, the difference between the rates, which reflects how easy it is for banks to get hold of short-term borrowing, is negligible.

The dollar, meanwhile, has surged against all currencies, as the cost to borrow dollars has risen substantially.

People and companies need cash to cover rent, bills and other fixed costs at a time when businesses and schools are shutting doors and sending staff home across the U.S. and Europe to halt the spread of the novel coronavirus.

“If you think about it from a small business standpoint, a big business standpoint, a fund manager standpoint—liquidity and cash is going to be king,” said John Briggs, head of strategy, Americas, at NatWest Markets. “Take Italy: They’ve just hard-stopped the eighth largest economy in the world. We’ve never seen anything like this.”

The Bank of England said Wednesday it would provide an unlimited amount of financing in commercial paper markets.

Small and medium-size companies in the U.S. and Europe are likely to be among the hardest hit because they have less room for error. Eric Lonergan, a portfolio manager at M&G Investments, said smaller companies in the U.K. were already delaying payments to their creditors if they could. Investors Create Cash Shortage,Investors Create Cash Shortage,Investors Create Cash Shortage,Investors Create Cash Shortage,Investors Create Cash Shortage,

“I think the entire economic system is trying to conserve cash at the moment,” he said.

Sushil Wadhwani, chief investment officer of QMA Wadhwani, a U.K.-based hedge fund, said the rational thing for individual companies was to access credit lines. Pension funds, meanwhile, which are normally built to ride out long market disruptions, may also be joining the cash dash.

“For pension funds, it is sell anything you can sell to build up reserves so you can tell your trustees that you have enough cash to pay pensions over the next nine or 10 months,” he said.

“The longer this goes on, the more bankruptcy you get and the more unemployment you get,” he said.

Updated: 3-21-2020

Flight To Quality: Investors Seek Shelter In US Dollars & Bitcoin

Two of the best-performing currencies since the March 12 meltdown have been the United States Dollar and Bitcoin. In times of economic turmoil, investors shed riskier assets and acquire less volatile ones. This is known as “flight to quality.” This happened in 2008 when the global demand for U.S. government bonds resulted in negative interest rates, and may be happening now with Bitcoin.

Bitcoin closed at $4,970.79 on March 12. However, on March 19, it rebounded 25% to $6,191.19.

Meanwhile, the USD has been gaining on its main competitors for global dominance: Euro, GBP, AUD, and CAD, amongst others.

Google Trends: Coronavirus, USD & BTC Go Hand-In-Hand

Google Trends indicates that the coronavirus has caused a simultaneous spike in searches for “Bitcoin” and the “United States dollar.”

There is a strong correlation between the searches for “Coronavirus,” “Bitcoin” and “United States Dollar.”

When the U.S. population began fixating on the virus in early March, it was followed by an increased interest in these two “quality” currencies. On the other hand, the interest in “Euro” and “FX Rates” are negatively correlated with “coronavirus.”

This could indicate that the public perceives two very different currencies as a hedge against potential economic collapse.

BTC Is A Hedge Against The Old Economy

As uncertainty about the old economic order deepens, even more people will start looking for an alternative, or hedge. It needs to be an asset that is as disconnected as possible from the rest of the economy. This used to be the gold, but without a solid banking system in place, there will be no gold as an asset class.

The same sentiment was expressed by Philip Salter, the head of operations at Genesis Mining, in a recent Cointelegraph interview:

“If this economic crisis is contained, then it will not have major implications for Bitcoin. However, if there is a real collapse, then the interest in Bitcoin will explode. It will go back to being seen as a hedge against the banking system. The more skepticism people will have in the old economy, the more they will flock to Bitcoin.”

Salter believes that an economic meltdown would fulfill the prophecy of Bitcoin becoming a new digital form of gold.

Updated: 3-21-2020

As This Crisis Worsens, Bitcoin Will Become A Safe Haven Again

Osho Jha is an investor, data scientist, and tech company executive who enjoys finding and analyzing unique data sets for investing in both public and private markets.

The week of March 9 was a ride regardless of what market you trade and invest in. Markets spiking up, markets spiking down, longs taking drawdowns, shorts getting stopped out on intraday bounces. While investor sentiment across markets was negative, there was also a sense of confusion as “there was nowhere to hide” in terms of assets.

Interestingly, I’ve yet to speak with anyone who made a “real killing” in that week’s trading. The ones who fared best are the ones who moved out of assets and into USD/hard currency and now have many options as to where to vest that capital.

On March 12, bitcoin having already traced down from $9,200 to $7,700 and then to $7,200 in the prior few days, plunged from $7,200 to $3,800 before spiking up and settling in the $4,800 to $5,200. The move tested the resolve of bitcoin bulls who had expected the upcoming halving to continue to drive the price higher.

Similarly, sentiment towards the crypto king and leading decentralized currency plunged with many pointing to bitcoin’s failure to be a hedge in troubled times – something that was long assumed to be a given due to the “digital-gold” nature of bitcoin. I, however, believe that these investors are mistaken in their analysis and that the safe haven nature of bitcoin is continuing.

Earlier that week, I wrote a short post on my thoughts around the BTC drawdown from $9,200 to $7,700. In it, I pointed out that gold prices were also taking a drawdown along with stocks and rates. My suspicion was there was some sort of liquidity crunch happening causing a cascading fire sale of assets.

This more or less played out exactly as one would expect, with all markets tanking later in the week and the Fed stepping in with a liquidity injection for short term markets. This liquidity injection included an expansion of the definition of collateral.

Repo Markets: The Canary In The Coal Mine

Having worked in both rates and equities, I’ve noticed that equities traders tend to ignore moves in rates and it’s, unfortunately, a waste of a very powerful signal. Specifically, “significant” or “odd” moves in short term markets signal shifts in the underlying liquidity needs for market participants.

While repo markets have many intricacies and dynamics, here is a general outline of what they do and how one might use them.

For context, a repo (repurchase agreement) is a short term loan – generally overnight – where one party sells securities to another and agrees to repurchase those securities at a date in the near future for a higher price. The securities serve as collateral, and the price difference between the initial sale and repurchase is the repo rate – i.e. the interest paid on the loan. A reverse repo is the opposite of this – i.e. one party buys securities and agrees to sell them back later.

Repo markets serve two important functions for the broader market. The first is that financial institutions such as hedge funds and broker-dealers, who often own lots of securities and little cash, can borrow from money market funds or mutual funds who often have lots of cash.

“This liquidity crunch and ensuing government intervention is laying the foundation for bitcoin’s adoption as a safe haven asset.”

The hedge funds can use this cash to finance day-to-day operations and trades, and money market funds can earn interest on their cash with little risk. Mostly, the securities used as collateral are U.S. Treasuries.

The second function for repo markets is that the Fed has a lever to conduct monetary policy. By buying or selling securities in the repo market, it is able to inject or withdraw money from the financial system.

Since the global financial crisis, repo markets have become an even more important tool for the Fed. Sure enough, the 2008 crash was preceded by odd movements in repo markets, showing what a good indicator of the future repo can be.

The Fragility of Our Current Financial System

With equities selling off in larger and larger moves and the markets becoming more volatile, the Fed injected liquidity into the short term markets.

While some headlines claim the Fed spent $1.5 trillion in a recent move to calm equities markets, those headlines are a bit sensationalist and are trying to equate last week’s actions to TARP (Troubled Asset Relief Program, which allowed the Fed to purchase toxic debt from bank balance sheets along with said banks’ stocks).

And I say this as someone with very little trust in the Fed. This wasn’t a bailout but was a move to calm funding markets and the money is now part of the repo markets making it a short term debt.

Let’s take a step back and think about what that means – short term markets where parties exchange very liquid collateral had a funding crisis, implying that market participants on aggregate didn’t have cash or didn’t want collateral in return for cash, and needed the intervention of the Fed to continue functioning.

There is no way to cut this as a positive. This would go a long way in explaining the wild movements and unprecedented yields hit across the entire yield curve. To make matters worse, this is not a new phenomenon. There was a funding crisis in September 2019 as well. It is clear that the repo markets are struggling without the Fed’s intervention.

Given the fire sale we saw recently, and the whipsaw in the treasuries markets, I suspect some funds were caught off guard, especially by the move in oil futures, and were unable to get funding. This then led to a sale of assets to generate cash and then a cascade of sales across markets.

What About BTC (And Gold)

To clarify, I keep putting “and Gold” in parentheses because the commentary applies to both markets given the nature of their fixed supply. I consider BTC to be a better version of gold as it is provably scarce, among other benefits.

However, gold has enamored mankind since…well, the dawn of mankind. So while I think BTC is the better option, gold has a place in portfolios not quite ready for digital currencies.

Bitcoin had a bad week, retracing much of 2019’s gains but remaining positive on a Y/Y basis (though it’s up again more recently). Here are the positives: bitcoin and traditional safe haven assets all sold off, bitcoin is now trading very cheaply on a USD basis, and the fundamental analysis and value proposition remains unchanged. Because of bitcoin’s newer, more volatile nature, the moves in this market will naturally be more extreme.

Safe Haven Status Remains Intact

People think bitcoin lost its safe asset use-case, but this liquidity crunch and ensuing government intervention is laying the foundation for bitcoin’s adoption as a safe haven asset.

It’s easy to talk about long term theses and other “hopeium” in the face of this nascent market’s most extreme recent drawdown and ignore the fact that a ton of people lost a ton of money. So let’s consider the short term thesis:

A “first-level” analysis would conclude that BTC went down, while stocks went down and so, there is no “store of value,” nor does it function as a “safe haven.”

I cannot stress how useless this commentary is, and masquerading it as “analysis” is somewhat insulting. Anybody with mediocre programming skills can plot two lines and point to a correlation – what value has this analysis added? None.

That aside, consider gold in 2008. Gold prices fell sharply at the beginning of the financial crisis, only to rally after TALF (Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facilities, which was a program to increase credit availability and support economic activity by facilitating renewed issuance of consumer and small business asset-backed securities.

Unlike TARP, TALF money came from the Fed and not the U.S. Treasury and so the program did not require congressional approval but an act of congress forced the Fed to reveal how funds were lent ) and other relief measures were implemented and then further bolstered by Quantitative Easing (QE), where central banks purchase a predetermined number of government bonds to increase the money supply and inject money directly into the economy.

In the U.S. QE started in November 2008 and ended about six years and $4.5 Trillion later.). This serves to illustrate that safe haven assets may sell off during a liquidity crunch but afterwards investors begin to see the need for assets with sound money properties that offer protection from currency devaluation.

For cryptocurrency markets, the signs of a pullback were building. I personally watch Bitmex leveraged positions to get an indication of where the market is. Whenever leveraged positions build up to an extreme, the market tends to (possibly is forced to) move in the opposite direction and clear out the leveraged positions.

There were over $1 billion in leveraged longs on Bitmex and from what I last read, roughly $700 million of those were wiped out during the week of the sell-off. It is a painful but necessary cleansing.

Because bitcoin is a mined coin with model-able production costs, it is important for fundamental investors to follow miner behavior closely. Leading up to the crash, miner inventory had built up. Miners either sell coins to market or build up reserves to sell when prices are more favorable.

This is called the MRI (miner rolling inventory). Chainalysis put out this fascinating chart that shows miners generated inventory vs. inventory sent to exchanges. One could assume miner hoarding is a sign that there is an expectation of a price increase, but a liquidity crunch throws all that out the window, AND historical data suggests that returns are better when miners are not hoarding.

So where do we go from here?

Losing money sucks, but when you invest or trade, it’s something you should get used to. If you’re a stellar investor, you’re probably still losing money 40 percent of the time. So, the short term shows a buying opportunity as we saw a large capitulation last week.

Alternative.me’s BTC Fear and Greed Index implies a startling change from last month flipping from a score of 59 (Greed) to 8 (Fear) showing that fear is currently the driving market force, and it’s almost always better to buy when others are fearful.

But I would urge caution. Until we see BTC, gold, and Treasuries dislocate from S&P500 i.e. break their recent correlation, I am cautiously deploying capital.

On a long horizon, things are going according to plan. The halving is still some blocks and months away. Miners who are already feeling the pain of this price reduction will continue to struggle to be profitable as block rewards are halved.

On Sunday, March 15th the Fed slashed baseline interest rates to 0 percent and announced the purchase of $700 billion in bonds and securities to calm financial markets and create an economic stimulus. After the recent pullback in stocks, many of us had assumed the Fed would engage in a new form of QE. If history serves us correctly, this is likely the first of many asset purchase programs.

The money printer is coming, and when that starts, fixed supply assets such as BTC and gold will do well. The stock market has spoken: it is demanding an economic stimulus and has shown over the past year that, without government liquidity injections, it cannot sustain its current growth.

Updated: 3-30-2020

Making Corporate America Hold Cash Is The Wrong Way To Prepare For Crises

What might make sense for a single company—amassing a rainy-day fund—makes less sense at the level of a whole economy.

As the economic impact of coronavirus lockdowns tears through business globally, the idea that companies should have held more cash to prepare for a rainy day is gaining currency.

For a single business, holding a buffer against unexpected slowdowns and other events outside its control might make sense. At the scale of a whole economy, it creates more problems than it solves.

For starters, despite the popular perception that American companies are overleveraged, U.S. nonfinancial corporations have been holding increasing amounts of cash in recent years. The value of checkable deposits and currency held by those firms has roughly quadrupled since the 2008 financial crisis, to over $1.2 trillion.

When imagining the impact of forcing or prodding companies to save more, it is worth remembering a simple macroeconomic accounting identity. If the private sector globally is lending on a net basis—meaning it’s accumulating assets, cash or otherwise—the world’s governments must be borrowing on a net basis. Without saying anything about the causality of the relationship, this is necessarily true in the most basic sense: One person’s asset is another person’s liability.

Of course, corporates could lend to other parts of the private sector—households, for example—but that would simply leave American families in a worse financial predicament during a shock. One country’s companies could lend overseas, but likewise that would simply shift the risk elsewhere.

If companies saved even more than they already do, demand for top-rated cash-like assets would rise. Governments could either issue more debt, or risk that corporations drift into superficially safe private assets as they did in the run-up to the financial crisis in 2008.

So the only solid path to higher corporate saving involves more government borrowing. Given that simple truth, there seems to be precious little difference between making companies pay taxes, and expecting the government to respond with fiscal policy in the result of an unpredictable emergency like a pandemic, and mandating that companies hold safe assets—typically in the form of government bonds—to cover themselves during emergencies.

Some might conclude from the current bailouts that corporations should pay more tax. That seems an easier fix than encouraging or even mandating gargantuan corporate cash hoards.

There are further arguments in favor of the existing arrangement. Holding cash depresses firms’ return on equity. That’s the reason why investors have spent decades pulling their hair out over the mountainous cash pile of Japan Inc. Cash holdings would also likely limit productive investment, as companies would save for a crisis that may take more than a decade to arrive.

The idea that corporations should set aside rainy-day funds to weather crises appeals to our sense of fairness and the understandable unpopularity of bailouts. But what makes sense for individual firms, as is often the case, makes less sense for the economy.

Updated: 1-19-2021

Shale Driller Stuns Bondholders As Argentina Runs Out of Dollars

In the 99 years since it was founded to pump the oil fields of Patagonia, Argentine energy driller YPF SA has been whipsawed by countless booms and busts. If global oil markets weren’t collapsing, it seemed, then Argentina was mired in a debt crisis that was wreaking havoc on the whole nation’s finances.

Never, though, had the company been pushed into a large-scale default of any kind. Until, it would appear, now. Word of this came in an odd way: Officials at state-run YPF sent a press release in the dead of night laying out a plan to saddle creditors with losses in a debt exchange.

Implicit in its statement was a threat that traders immediately understood — failure to reach a restructuring deal could lead to a flat-out suspension of debt payments — and they began frantically unloading the shale driller’s bonds the next morning. Today, some two weeks later, the securities trade as low as 56 cents on the dollar.

Creditors, including BlackRock Inc. and Howard Marks’s Oaktree Capital Group, are gearing up for bare-knuckled negotiations just four months after ironing out a restructuring deal with the government that marked the country’s third sovereign default this century alone.

YPF’s downfall underscores just how hard the pandemic has hammered both the global oil industry and the perennially hobbled Argentine economy. Dollars are now so scarce in Buenos Aires that the central bank refused to let YPF buy the full amount it needed to pay notes coming due in March. That was the immediate cause of the restructuring announcement.

A longer view reveals a steady decline in the company’s finances since the government re-nationalized it in 2012 and forced it to swell payrolls, artificially hold down domestic fuel prices and skimp on investments, leading to four straight years of oil-and-gas output declines.

YPF must now reach a deal with creditors to get its finances in order to boost investment in the gas-rich Vaca Muerta shale formation in Patagonia.

The task is even more urgent as the South American winter approaches with YPF unable to meet domestic gas demand, meaning Argentina will have to boost imports — and fork over precious hard currency — in the middle of a global spike in prices.

“The central bank’s decision really put YPF between a rock and a hard place,” said Lorena Reich, a corporate-debt analyst at Lucror Analytics in Buenos Aires.

Officially, YPF says that the swap is voluntary and that it will continue to pay all its bonds whether they are exchanged or not. But that’s certainly not how investors understand the situation, and ratings companies say the proposal constitutes a distressed exchange that would be tantamount to default.

Overall, YPF is seeking to restructure $6.2 billion of bonds, pushing back a total of $2.1 billion in debt payments through the end of next year so that it can invest the money in bolstering production. The deal offers investors a slight upside from current bond prices, but would stick creditors with losses of as high as 16% on a net-present-value basis, according to calculations by Portfolio Personal Inversiones, a local brokerage.

While some investors had anticipated YPF would try to refinance its short-term debt — without imposing any losses — the plan to restructure virtually all the company’s overseas bonds was a big surprise.

“The offer crossed the line of reason,” said Ray Zucaro, the chief investment officer at RVX Asset Management in Miami, who owns YPF bonds. “There was no reason they needed to include all the bonds when they only needed relief on the short-dated notes.”

YPF says it included all its securities in the swap to give all its bondholders a fair shot at exchanging into a new export-backed note maturing in 2026 that offers more protection than unsecured debt.

Creditors have begun to form groups to negotiate the terms of the restructuring, and while the talks haven’t begun in earnest, the company says it’s willing to negotiate. On Jan. 14, YPF amended some of the rules for its consent solicitation after investor outcry over a procedural issue.

Cash Crunch

Argentina’s cash crunch couldn’t come at a worse time for YPF, which was already facing a drop in demand because of the pandemic. The driller needs more investment to ramp up capital-intensive shale production in Vaca Muerta as aging traditional fields decline. It’s expected to spend $2.2 billion in 2021 after last year’s paltry $1.5 billion. But that’s still a far cry from the more than $6 billion a year it invested in the wake of the nationalization.

As the company looks for savings in the bond market, it’s also slashing other costs, cutting salaries and reducing its bloated workforce by 12%. It’s trying to sell stakes in some oil fields, as well as its headquarters in Buenos Aires, a sleek glass skyscraper where executives take calls looking out over the vast River Plate estuary into Uruguay.

Founded in 1922 as one of the world’s first entirely state-run oil companies, YPF was passed from nationalist governments to military dictatorships until the early 1990s, when it was sold to Madrid-based Repsol SA as part of a short-lived attempt to free up the economy. In 2012, President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner’s leftist government expropriated 51% of the company, eventually paying Repsol $5 billion in bonds for its stake. YPF’s market value today is just $1.6 billion.

The central bank’s refusal to sell YPF the dollars it needs to pay its obligations, despite the company’s earlier efforts to refinance its short-term debt, is a bad sign for all overseas corporate bonds from Argentina, according to the financial services firm TPCG. The concern is that if the country’s flagship company isn’t eligible to buy dollars at the official exchange rate as the bank seeks to hold onto hard-currency reserves, no one else will be either.

“The central bank’s message is pretty clear,” said Santiago Barros Moss, a TPCG analyst in Buenos Aires. “There just aren’t enough dollars in Argentina for corporates right now.”

Investors Create Cash Shortage,Investors Create Cash Shortage,Investors Create Cash Shortage,Investors Create Cash Shortage,Investors Create Cash Shortage,Investors Create Cash Shortage,Investors Create Cash Shortage,Investors Create Cash Shortage,

Go back

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.