Federal Reserve Taps BlackRock To Purchase Bonds For The Government (#GotBitcoin)

World’s largest money manager by assets to purchase agency CMBS on behalf of New York Federal Reserve. Federal Reserve Taps BlackRock To Purchase Bonds For The Government (#GotBitcoin)

The Federal Reserve on Tuesday asked BlackRock Inc. to steer tens of billions of dollars in bond purchases, a reflection of the influence of the world’s largest money manager.

Related:

BlackRock Offices Raided in German Tax Probe

BlackRock (Assets Under Management $7.4 Trillion) CEO: Bitcoin Has Caught Our Attention

BlackRock Exposes Confidential Data on Thousands of Advisers on iShares Site

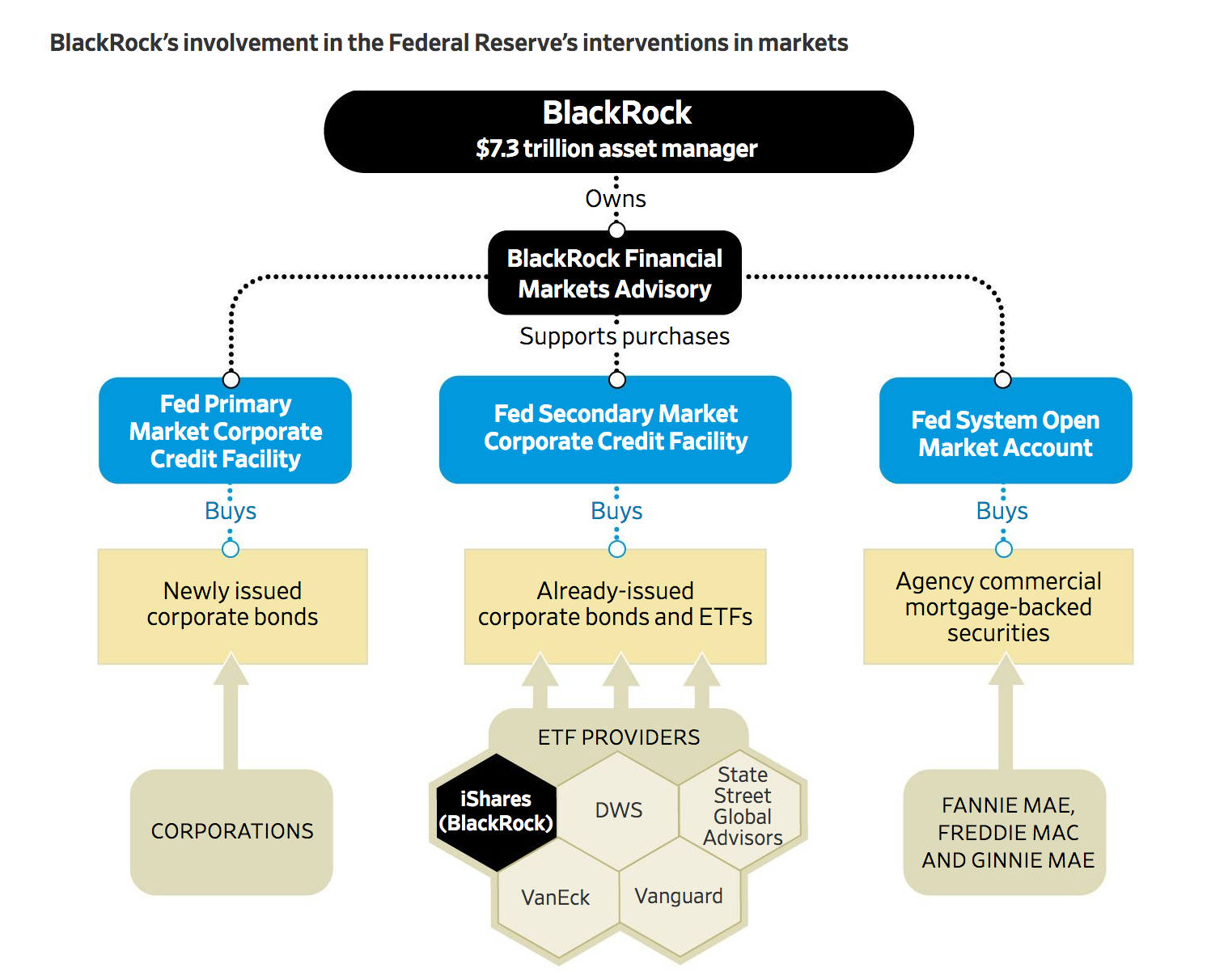

BlackRock will purchase agency commercial mortgage-backed securities secured by multifamily-home mortgages on behalf of the New York Federal Reserve. The Fed will determine which securities guaranteed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and Ginnie Mae are suitable for purchase. BlackRock will execute the trades.

BlackRock also will manage two large bond-buying programs. It will be in charge of a Fed-backed facility to buy new investment-grade bonds from U.S. companies.

The firm also will oversee another vehicle for buying already-issued investment-grade bonds. Bond purchases will be the focus of that effort. But the firm has latitude to buy U.S. investment grade bond ETFs—including exchange-traded funds of its own. BlackRock is the largest provider of bond ETFs.

The mandate is expected to be significant. The Treasury Department is expected to inject $10 billion in initial equity funding in connection with each of the two facilities, according to a previous Fed statement.

The tasks place BlackRock in a potentially controversial position of implementing the administration’s response to the spreading coronavirus pandemic. The firm’s roughly $7-trillion reach extends into everything from equities to bonds to private equity. The firm will face significant scrutiny on how it prevents conflicts of interests.

BlackRock will be working with the Fed through its financial markets advisory business, and not its asset-management arm.

That financial markets unit advises governments on how to manage their balance sheets, assisting them in the purchase of investments and the unwinding of toxic instruments.

For the program that involves ETF purchases, BlackRock can’t invest in more than 20% in any one ETF.

Exchange-traded funds that mirror broad swaths of the market can sometimes be a more politically palatable way of pumping money into the fixed-income market than investing in individual securities. It doesn’t require a manager to actively pick winners and losers, but simply track an index.

BlackRock will use Aladdin, a software system that assesses risks and prices investments, to monitor the assets. Aladdin watches over more than $20 trillion in assets.

BlackRock Chief Executive Laurence Fink is no stranger to turning his Rolodex and Aladdin into a powerful role for his firm in times of crisis. In the last financial crisis, the U.S. government tapped BlackRock to oversee assets once owned by Bear Stearns Cos. and American International Group Inc. after the two financial institutions collapsed.

That mandate put scrutiny on the firm, generated billions of dollars to the U.S. government and became a milestone that sealed BlackRock’s influence in Washington.

Mr. Fink, in a recent market briefing to some clients, said the firm was working with regulators to ensure the smooth functioning of markets. He has told clients the current situation doesn’t rise to the magnitude of a financial crisis, but it does mark a crisis of confidence that can be addressed with the help of prudent fiscal policy.

Updated: 4-8-2020

State Funding Woes Are Dragging The Fed Into Muni-Market Reboot

The central bank has been aggressive in supporting the economy, but financing by local governments poses unique challenges.

Reviving the market for bonds sold by state and local governments is shaping up as one of the stiffest tests in the Federal Reserve’s campaign to restore financial normalcy.

The Fed has committed trillions of dollars to keep money flowing through markets vital to economic growth, including huge purchases of government and mortgage securities and new programs to backstop money-market funds and corporate-debt markets.

Those efforts have helped to fuel the markets’ partial recovery, say investors and portfolio managers, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average up 22% from its March 23 low.

But the central bank is limited in its efforts to revive the $4 trillion market for municipal securities, which back everything from school facilities to stadiums and highways.

The Fed has so far intervened in only a few corners of the market, which is fraught with idiosyncrasies that make it difficult to categorize debt as investment-grade or risky, the line in the sand drawn by the Fed to ascertain what it backstops during a crisis.

The constraints stem in part from the coronavirus’s decimation of state and local finances, which could make the risks even harder to judge, and the Fed’s traditional deference to Congress in handling local government financing decisions.

“The Fed doesn’t want to be in a position to say you have to raise taxes or cut pay to policemen or firemen” to secure or repay a loan from the central bank, said Scott Alvarez, who was the Fed’s general counsel from 2004 to 2017.

Fed and Treasury Department officials are working on a program to backstop some financing for states, according to people familiar with the matter, but the devil of any program will be in the details.

While the Fed has the authority to purchase municipal debt with maturities of six months or less, it hasn’t exercised that authority. A more likely route would be to establish an emergency lending program to backstop longer-dated muni debt. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin told Democratic lawmakers Wednesday that officials would unveil their financing plans soon.

The $2 trillion rescue package that Washington approved last month includes $454 billion that the Treasury can use to absorb losses on any Fed lending facilities. That bill provided $200 billion in direct funding for states and cities, but they are likely to need another $300 billion to $600 billion, said Tom Kozlik, head of municipal credit at Hilltop Securities.

The aid to cities and states in the recent rescue package “will not be enough to offset the cost many states and municipalities are encountering,” said Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren. The Fed can help with financial markets, but those efforts will be less effective without more direct aid, he said.

Officials are trying to avoid a rerun of state and local government layoffs after the 2007-09 recession, which contributed to an underwhelming economic recovery despite unprecedented Fed stimulus.

The Fed typically seeks to steer clear of concerns about the potential loss of taxpayer funds by focusing on purchases of assets such as highly rated bonds whose default is widely judged to be minimal.

Such judgments are harder to come by in the market for municipal bonds, where even the strongest borrowers have been hammered by the challenges arising from an unprecedented shutdown of business and commerce around the country.

States face not just the burden of boosting spending on public-health responses, but also a drop in revenue from sharp declines in sales-tax collections.

“In almost every way, states are at the front lines of fighting this,” said Joe Torsella, Pennsylvania’s state treasurer.

Fears that state and local finances will be permanently damaged are evident in the investor flight from this market, which until recently has ranked among the most resilient.

In March, investors pulled $32.8 billion from municipal-bond mutual and exchange-traded funds, according to Refinitiv, the largest monthly outflows since data collection began in 1992. State and local governments canceled billions of dollars of planned borrowing. The S&P Municipal Bond Index gave up more than a year’s worth of gains.

The Fed has long resisted lending to states and companies, having spurned requests from lawmakers in 2008 to aid ailing U.S. auto makers and ruled out a muni-debt backstop.

The central bank has already broken some taboos during the current crisis. It is in the process of unveiling lending facilities for large and midsize companies, and it has dipped a toe into muni-debt markets by expanding a money-market lending backstop to include certain types of municipal debt—and by purchasing some highly rated municipal debt in a facility backing the market for very-short-term commercial debt.

Analysts and state officials said the Fed could provide support by buying a broad-based muni index, avoiding the prospect of picking winners and losers outright.

Among the issues the Fed must weigh is who ultimately benefits. The yields on bonds issued by Montgomery County, Md., an affluent suburb of Washington, D.C., and Cook County, Ill., home to Chicago and where more than 700,000 people live in poverty, both jumped more than 2 percentage points over a week in March, indicating lower prices.

Yields on the Montgomery County bonds have since declined more than those on the Cook County bonds—indicating that while the market views the Montgomery County bonds as a better risk, the Cook County securities are potentially the ones more in need of support. Those sorts of regional and distributional issues carry significant risk for the Fed, investors said.

“It would be very problematic for the institution and its credibility to decide between New York and Montana,” said Mark Spindel, a Washington-based investment manager who co-wrote a history of the Fed.

The prospect of increased lending to businesses and local governments, often in consultation with the Treasury Department, could reshape the Fed’s longstanding autonomy from the executive branch.

During and after World War II, the central bank pegged Treasury yields to finance war spending and the recovery. A bruising fight with the Truman administration, which resulted in the resignation of the Fed chairman, ultimately led to a formal agreement in 1951 to end the Fed’s policy of fixing Treasury yields.

“I think it is possible that we will have a central bank when this is all over that has sacrificed a piece of its independence,” said Jeremy Stein, a former Fed governor who now teaches at Harvard.

Fears about the loss of central-bank independence are overstated given the gravity of the current crisis, said Mr. Torsella.

While political and constitutional tensions loom, “smart, well-intentioned people can figure out how to do this in a way” that “simply restores functioning of this market,” said Mr. Torsella. “I want to make sure we have a fighting chance of getting back to those more normal times.”

Updated: 5-10-2020

Big Money Managers Take Lead Role In Managing Coronavirus Stimulus

BlackRock is about to start buying billions of dollars in corporate bonds for the Fed, reflecting the firm’s rise to financial might but also opening it to scrutiny.

The Federal Reserve’s giant program of corporate bond buying is about to kick in. It will hand a critical new role in propping the struggling economy to a business with increasing clout in the financial world: money management.

The central bank has tapped BlackRock Inc. to help it direct money into both new and already-issued corporate bonds, assisting the Fed in its recently adopted role as lender of last resort for businesses. The Fed is expected to launch the program in coming days.

The Fed also has given Pacific Investment Management Co., or Pimco, the job of helping it purchase commercial paper, or companies’ short-term borrowings. That program is already up and running.

The two firms could eventually invest hundreds of billions of central-bank dollars.

Their role as agents of the Fed’s intervention is the latest chapter in a decadelong shift in the financial power structure, with the largest asset managers gaining ground on Wall Street banks.

A few leading asset managers have become critical conduits for directing the money of individuals, pension plans and endowments into U.S. companies. BlackRock and Pimco are shareholders and debtholders in thousands of companies on behalf of funds they manage.

The shareholder votes they control and their role as creditors give them powerful levers. The two collectively manage more than $8 trillion, across markets from bonds to private equity.

They oversee money in exchange-traded funds and traditional mutual funds that are held mainly by individuals. The firms run all kinds of funds and managed accounts. In these, a client entrusts the money-management firm with cash that the firm invests in line with the mandate it’s given, whether betting on individual companies, targeting certain industries or mirroring a market.

Although money-management firms played roles in the 2008 financial crisis, helping to handle toxic assets for the Fed, their remit in the new crisis is far bigger. They will be central players in what is expected to be a multitrillion-dollar overall program of central-bank support to the economy and markets, a program that will help decide which businesses survive the pandemic.

“Here’s a chance for asset managers to show they could be powerful partners in the recovery,” said Ben Phillips, a principal at Deloitte consulting arm Casey Quirk. “They’re organizing capital, as opposed to using their own balance sheet, and can think longer term.”

They are taking on new importance as the biggest investment firms have pushed back on the idea that their reach brings unintended risks for financial systems. Asset managers have successfully fought against the label as “systemically important financial institutions” and the regulations that come with it.

BlackRock will steer as much as $750 billion into the corporate debt market for the Fed.

“BlackRock is acting as a fiduciary to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York,” a firm spokesman said in a written statement.

“BlackRock will execute this mandate at the sole discretion of the Bank, and in accordance with their detailed investment guidelines,” he said, “in order to provide broad support to credit markets and achieve the government’s objective of supporting access to credit for US employers and supporting the American economy.”

Former government officials encouraged administration officials not to hire banks for the corporate-bond buying, said people familiar with the matter. They believed that money-management firms, by not being in the business of arranging debt offerings or maintaining an inventory of bonds for clients, would be best positioned to be impartial.

Also suiting them for the Fed operation, the biggest investment firms have experience managing central bank money, have systems to cordon off work for different clients, and can make informed purchases because they sit in the middle of a stream of information about buying and selling all kinds of securities, the former officials said.

In early March, when data signalled market strains a few weeks after the first U.S. coronavirus cases, Fed staffers examined the tools used in the 2008 crisis. They also laid the groundwork for potentially having the central bank act much more broadly.

Through March’s extreme market volatility, Fed and government officials were on the phone with investors at BlackRock and Pimco as well as Goldman Sachs Group Inc.’s asset-management arm, JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s investment team and State Street Corp., said people familiar with the outreach. They consulted prominent investors such as Mohamed El-Erian, chief economic adviser to Pimco parent Allianz SE.

The officials tapped all kinds of networks to understand what was happening in the commercial paper market; the state of the “repo” market where firms borrow and lend cash and Treasurys; and how the bond market was doing. There was deep trouble in almost every corner of the bond world by mid-March. Junk bonds, investment-grade bonds, Treasurys—all saw shortages of buyers.

During the week of March 15, a Fed official phoned Scott Simon, a former Pimco head of trading and portfolio management, for perspective. Mr. Simon advised the official to regard mortgage real-estate investment trusts as coal-mine canaries signaling danger. Mortgage REITs, which borrow and invest the proceeds in mortgages, and which rarely play a meaningful role in the overall economy, saw their share prices tumble.

Mr. Simon also pointed to an exchange-traded fund, BlackRock’s iShares iBoxx $ Investment Grade Corporate Bond ETF, which was among a swath of bond ETFs trading at steep discounts to the values of the bonds inside them. He said the gap was a sign the bond market was frozen.

“If you don’t fix” the market for top-rated bonds, “it will get away from you,” he told the Fed official, according to a person close to the matter.

During one of the worst weeks in Wall Street history, BlackRock Chief Executive Laurence Fink went to Washington and huddled with President Trump as a pandemic with no equivalent in modern history roiled markets. Stocks fell more than 7% the day they met, March 18, and trading almost stopped in several bond markets, making it hard for corporations as well as cities to raise needed cash.

The Fed had said it would intervene substantially in money-market funds, and would shift its purchases of Treasury bills toward a broader range of maturities. Then on March 23 it unveiled sweeping measures. It said it would purchase all kinds of bonds, pledging to do whatever was needed to shore up the economy.

The Fed works with outside firms if it believes they bring speed and expertise the central bank can’t provide on its own. Moving fast, it tapped BlackRock’s financial markets advisory business to buy corporate bonds for it, without a tender process that would let others bid for the job.

That arm of BlackRock, separate from its money-management business, worked for the Fed in handling assets of American International Group Inc. and Bear Stearns Cos. after both collapsed early in the financial crisis.

The issue was who could get a program up and moving fast, said a former senior U.S. official who was an informal adviser to Treasury officials and other policy makers as they formulated plans.

The Fed first focused on the highest-rated companies, those least likely to default. It wrestled with a question: What about companies that would be highly rated except that coronavirus-related troubles had cut them to junk? Would it be right to leave them out? When the Fed said on April 9 it would buy fallen-angel bonds too, its word sparked a bond rally long before any Fed buying.

As part of its role, BlackRock would buy bond ETFs. Fed officials saw this as a way to buoy broad swaths of the market rapidly, said a person with knowledge of their thinking.

Rivals cried foul. Some economists and finance commentators voiced concern the Fed mandate would allow BlackRock to boost its own ETFs.

“If you’re an asset manager working for the Fed, your own funds should be excluded from the purchases,” said Nouriel Roubini, an economics professor at the New York University’s Stern School of Business and chief executive of Roubini Macro Associates.

During a call with analysts April 16, BlackRock’s Mr. Fink bristled at the suggestion the Fed mandate was a bailout for the ETF industry or his firm. “I think it’s insulting,” he said. “What we’re doing with governments is based on great practices.”

The Fed will use predetermined rules to guide its investments, to avoid picking winners and losers, said people familiar with the matter.

The central bank said in preliminary disclosures that BlackRock would assess its own ETFs on equal footing with those of competitors, and the firm won’t charge fees on investing in any ETFs. BlackRock will credit income it could earn on the Fed program’s holdings of the firm’s ETFs back to the central bank. There would also be limits on how much of any one ETF could be bought.

That hasn’t stopped investors from trying to get in ahead of the Fed. In April, traders rushed into corporate-bond ETFs, including the one Mr. Simon flagged. They briefly drove the ETF’s price sharply above the bonds’ value. The gap between its price and the net asset value of its underlying bonds has since narrowed.

The central bank gave Pimco a commercial-paper role similar to what it had in 2008, and disclosed no limit on total purchases of the short-term corporate debt. The Fed did give banks one job—processing emergency loans for businesses. State Street will hold custody of assets for a number of Fed programs.

Other firms will be allowed to bid on BlackRock’s and Pimco’s work for the Fed as soon as this summer, said people familiar with the plans.

“If you’re the firm running a large mandate, you’re going to be the first call from brokers and the destination for information. It could make it difficult for other investors to compete,” said Patrick Luby, a municipal strategist at research firm CreditSights Inc. “But there will be benefits for others who can now take advantage of a healthy functioning market,” he added.

The Treasury promised to shoulder any initial losses on the Fed’s mammoth purchases. The central bank isn’t allowed to risk taxpayer money by propping up insolvent companies. During negotiations over the Treasury funds, Senate banking committee members tried to lock in prescriptive terms on how the Fed and Treasury would deploy the money. Fed officials voiced concerns, and won flexibility.

Some Democratic lawmakers said BlackRock’s outsize role risks unintended consequences for the financial system. In April, one group circulated a letter to the Fed urging the government to come up with safeguards so the economy doesn’t become over-reliant on BlackRock. Various politicians also pressed the Fed to make BlackRock consider the costs to the environment when it steers money for the government.

“We’re choosing financial champions,” said Itamar Drechsler, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School who studies the effects of central bank policies. “Hiring a big firm to execute the buying is in a sense a simple way to get expertise,” he said, “but there are good reasons why people are wary of having national champions.”

Updated: 5-12-2020

BlackRock Stock Still Isn’t Cheap After PNC Sale, Analyst Says

Shares of BlackRock, down sharply after PNC Financial Services announced it would sell its 22.4% stake in the world’s largest asset manager, still aren’t attractive, writes Morningstar analyst Greggory Warren.

PNC (ticker: PNC), believed to be in the hunt for more deals, currently holds 34.8 million shares of BlackRock (BLK), worth about $17 billion. Not all of PNC’s interest will be sold in the secondary offering. BlackRock has committed to buy approximately $1.1 billion worth of its common shares back from the bank after the secondary sale closes. PNC will also donate 500,000 shares (about $247 million) to its charitable organization. BlackRock has 154 million shares outstanding.

Despite the dip, BlackRock stock trades at 99% of Morningstar’s fair-value estimate of $500 a share, or 18 times Morningstar’s 2020 earnings estimate and 16.6 times its 2021 forecast. “It would take a meaningful sell-off in the shares to get them into more attractive territory for long-term investors,” Warren writes.

The bank first invested in BlackRock in 1995.

The deal removes the potential for future large-scale sales, and a bigger float is a good thing for shareholders.

“This sale will increase [BlackRock’s] float, trading volume and index ownership,” wrote analysts at Credit Suisse. And it will “further separate [BlackRock] from PNC’s regulatory oversight.”

BlackRock, with $6.467 trillion in assets under management, is a market favorite owing to solid long-term growth thanks in part to iShares, the leading domestic and global provider of exchange-traded funds. Warren estimates BlackRock’s assets will grow 3% to 5% a year, and revenue at a similar rate.

“The deal is way more about PNC than BlackRock,” says investment manager Jim Russell of Cincinnati-based Bahl and Gaynor, which owns shares of both companies. Russell said it would free up capital for PNC, which it needed to hold against the BlackRock investment, as loan losses worsen in the industry and acquisition targets emerge. PNC’s BlackRock investment has risen roughly 70-fold.

PNC may have considered the sale in March as it contemplated doubling its provision for credit losses, Russell said, but the steep market decline may have prevented it. “The rally got them over the line,” he added.

Analysts will be busy trimming earnings forecasts for PNC for 2020 and 2021 because BlackRock was additive to earnings.

Part of the decline in BlackRock shares is “the market worried about a less strategic [buyer] or long-term holding in potentially weaker hands,” Stephen Bigger, director of financial institutions research at Argus Research, told Barron’s.

So far, however, no such buyer has emerged. “Very short term, this is a supply and demand imbalance,” says Russell. BlackRock shares have been “jostled around a bit” but have enormous appeal because of the strength of its ETF platform and the popularity of its Aladdin risk-management platform with other managers, he said.

Russell, who owns stocks with strong patterns of annual dividend growth, continues to like both BlackRock and PNC.

Updated: 5-12-2020

Are Blackstone And Blackrock Related To One Another?

When Larry Fink and his co-founders started his fledgling risk management and bond analytics advisory firm in 1988, he was seeded by Blackstone co-founders Steve Schwarzman and Pete Peterson. In fact, the firm known today as BlackRock started life as Blackstone Financial Management.

In time, ‘Blackstone Financial Management’ grew rapidly. By 1994, with over $50 billion under management, it became time for the two organizations to formally separate. In a decision I imagine he has since had cause to regret more than once, Schwarzman allowed Fink to call the business ‘BlackRock’.

While this may have been a natural evolution of its original name, I can’t imagine Schwarzman would have agreed to this arrangement if he’d had the slightest sense for what BlackRock would become. In recent years he has (I believe) acknowledged that a tipping point arrived a few years ago where people went from referring to BlackRock as Blackstone (since the latter was historically the better known brand) to referring to Blackstone as BlackRock.

Updated: 6-7-2020

Fed Debates Whether To Reinforce Low-Rate Pledge With Yield Caps

Officials are studying Australia’s program to buy government securities in unlimited quantities to peg some yields at low levels.

To stimulate the economy in the past decade with interest rates pinned near zero, the Federal Reserve made promises about how long they would remain low.

Now, Fed officials are thinking hard about a new tool that would reinforce such promises by committing to buy Treasury securities in whatever amounts are needed to peg certain yields at low levels.

Fed officials aren’t prepared to announce any decision on so-called yield caps when their two-day policy meeting concludes Wednesday.

With rates near zero and unlikely to go lower, two other policy questions must get resolved first: how to manage their pace of bond purchases and how to communicate their long-run intentions, using so-called forward guidance.

Fed officials believe forward guidance helps stimulate demand after their policy rate is near zero because it sets public expectations about future policy, which influences the rates set by markets.

How they calibrate those two tools could determine whether and how they cap yields, which would function as a hybrid of both. The Fed hasn’t capped yields on Treasury securities since 1951, when it dismantled a stimulus scheme used during World War II.

Fed officials are closely studying the experience of Australia’s central bank, which in March set a target of 0.25% for the country’s three-year government-bond yield and which has so far managed to keep it there without significant asset buying.

For the U.S., caps might work like this: If the Fed concludes it is likely to hold rates near zero for at least three years, it could amplify this commitment by capping yields on every Treasury security that matures before June 2023.

While some officials don’t think caps are needed now because investors don’t expect the Fed to lift short-term rates for several years, caps could limit any unwelcome jump in Treasury yields due, for example, to a coming surge of government-debt issuance to finance virus-related economic relief.

Reinforcing forward guidance with caps could also push back against the strong pressure to raise rates that officials faced last decade amid fears of an inflation upturn that never materialized, said Fed governor Lael Brainard in a speech last fall.

First, officials will have to design their forward guidance and consider their asset-purchase goals. Forward guidance comes in two flavors: One ties changes in rates to meeting certain economic thresholds, while the other links them to certain calendar dates in the future. In the first case, for example, the Fed could say it won’t raise rates until inflation reaches 2% and unemployment falls to 5%. In the second, it could say it will hold rates steady for at least two years.

Tying guidance to economic thresholds might better address the uncertainty surrounding the outlook, while calendar-based guidance provides more certainty to investors and could be more effective at keeping rates low when data turn around decisively, said Roberto Perli, a former Fed economist who is now at Cornerstone Macro.

Yield caps would be a natural complement to the calendar-based guidance but could be trickier to communicate if paired with outcome-based guidance.

Capping yields brings risks. Because investors already expect rates to stay low, the tool may not provide much stimulus unless the Fed were prepared to target longer-dated Treasurys. Prematurely ending the caps, either because of inflation or financial-stability concerns, would damage the Fed’s credibility and could lead to a nasty rise in rates. Setting caps at a level investors deem too low could force the Fed to buy massive amounts of securities to defend its peg.

“It’s easy going in, but we don’t really understand how the exit is actually going to work,” said William Dudley, who was president of the New York Fed from 2009 to 2018.

At this week’s meeting, Fed officials are likely to debate how to clarify their asset-purchase plans. The Fed extinguished a financial panic in mid-March by purchasing huge quantities of Treasurys and mortgage bonds after investors dumped long-dated securities in a flight for cash. The Fed has been gradually reducing purchases every week.

Officials have said their purchases, totaling more than $2.2 trillion since mid-March, are designed to restore orderly market function. This rationale is different from their prior open-ended round of asset purchases, called quantitative easing or QE, conducted between 2012 and 2014, which was designed to stimulate hiring and investment and was more concentrated at longer-dated securities than the current purchases have been.

Finally, officials face questions about when to roll out any policy shift. Recessions have typically been caused by a sharp rise in oil prices or economic and financial imbalances that trigger an abrupt increase in interest rates. The Fed cuts interest rates to stimulate growth during and after a downturn.

The current downturn is different. The economy is facing a cash-flow problem, not just a drop-off in demand, and a potential wave of bankruptcies looms. Because it may take time to safely restore economic activity given the threat of infection, what ails the economy can’t be solved solely by boosting demand.

Economists have warned that while financial markets are functioning better amid recent Fed actions, the lifting of lockdown orders could reveal more economic damage than expected.

Analysts at Bank of America think the Fed will implement forward guidance and yield caps in September, “once the bounce from reopening passes and it becomes clear that the recovery will be protracted and challenging,” said Mark Cabana, the bank’s head of interest-rate strategy.

Declining inflation would mean that short-term interest rates, adjusted for inflation, could rise, posing a challenge for Fed policy makers as they seek to provide more stimulus in the coming months.

By the fall, Mr. Cabana expects inflation will be running very low, and the Fed will want to push expectations of future inflation higher by sending a strong signal that rates will be held near zero until 2023 if not longer.

Updated: 6-28-2020

Automakers, Technology Firms Are Largest Components of Fed’s Corporate-Bond Purchases (#GotBitcoin?)

The central bank disclosed names of 794 companies whose bonds it began purchasing this month.

Apple Inc., Verizon Corp. and the U.S. divisions of several foreign auto makers are among the largest direct beneficiaries of Federal Reserve efforts to support the corporate-debt market, according to disclosures Sunday.

In all, the Fed on Sunday identified 794 companies whose bonds it will be buying directly to support the market for investment-grade corporate debt. In addition to Apple and Verizon, the recipients include AT&T Inc. and the U.S. units of Toyota Motor Corp., Volkswagen AG and Daimler AG. Together those six companies accounted for 10% of debt purchased from a broad list of borrowers the Fed is supporting.

The list includes debt from across 12 different sectors. Two of those—consumer cyclical and consumer noncyclical industries—account for more than one-third of corporate bonds the central bank planned to purchase, according to the latest disclosures.

The Fed announced in March that it would buy corporate debt to prevent the market from freezing up and squeezing companies of needed cash as the economy ground to a halt from the coronavirus shock to the nation.

The central bank’s corporate-debt program is structured in different phases. The Fed plans to purchase up to $250 billion of debt already issued by companies. Later it plans to purchase up to $500 billion in newly issued bonds.

As part of its purchases of outstanding debt, the Fed in mid-May started buying exchange-traded funds that hold investment-grade and junk bonds. In another phase of those purchases, the Fed this month started buying actual corporate bonds, and not just ETFs. The latest central-bank disclosures for the first time included the actual bonds it started buying this month.

In all, the central bank accumulated $8.7 billion in corporate debt through June 24. The program runs through Sept. 30. The Fed’s support has led to a boom of debt issuance by U.S. companies.

The Fed is tapping into a $9.6 trillion corporate-debt market from companies that satisfy the Fed lending program’s criteria, including companies that were investment-grade-rated as of March 22 and had maturities no longer than five years in duration.

The Fed will recalculate the list of its potential purchases every four or five weeks to add companies that meet the eligibility requirements and to remove those that no longer qualify.

The latest disclosures showed $398 million in securities purchased as of June 17, the first two days of individual bond purchases. Those include bonds issued by drugmaker AbbVie Inc., media company Comcast Corp., beverage giant Coca-Cola Co. and UnitedHealth Group Inc., parent of the nation’s largest health insurer.

The announcements of the lending programs—on March 23, when the Fed said it would buy investment-grade debt, and on April 9, when it said it would include debt of so-called fallen angels that had been downgraded from investment grade after March 22— helped sharply reduce borrowing costs for an array of businesses.

Some critics have questioned whether the Fed should be buying bonds in the secondary market at all since borrowing is now so cheap.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell defended the purchases at a congressional hearing earlier this month. Markets reacted strongly to the central bank’s announcement because investors expect the Fed to follow through with those purchases.

“We feel that we need to follow through and do what we said we’re going to do,” he said.

The Fed will dial up or down the quantity of bonds it buys depending on various measures of market functioning. If those measures indicate sustained improvement to levels that prevailed before the coronavirus pandemic disrupted markets in March, the Fed’s purchases would “slow notably and, in some cases, could pause entirely,” the New York Fed said earlier this month.

It is possible the Fed won’t buy the maximum $250 billion it has allocated for the program by Sept. 30.

On the other hand, purchases would increase “if those measures subsequently indicate a deterioration in market functioning,” it said.

The Fed also disclosed $6.8 billion in holdings of ETFs that invest in corporate debt, up from $1.3 billion one month earlier. Funds that focus on buying non-investment-grade debt accounted for around 11% of the central bank’s ETF purchases, down from around 17% for the period May 12 to May 18.

Updated: 7-8-2020

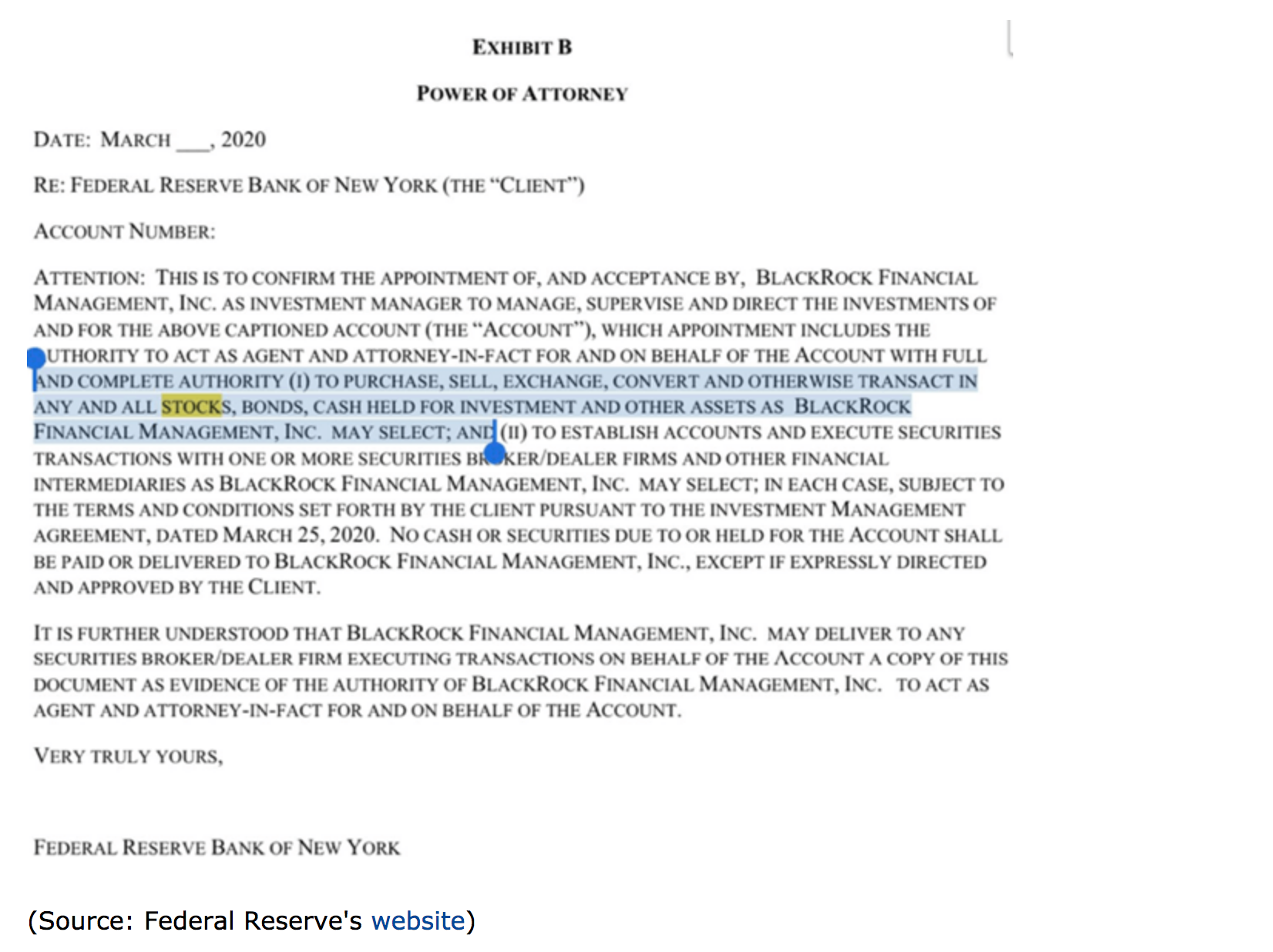

Exhibit B In Below Shows Fed Is Ready To Buy Stocks

* Janet Yellen said, “but longer term it wouldn’t be a bad thing for Congress to reconsider the powers that the Fed has with respect to assets it can own.”

* The Bank of Japan and Swiss National Bank serves as a template for the U.S. Fed to copy should they really need to purchase stocks.

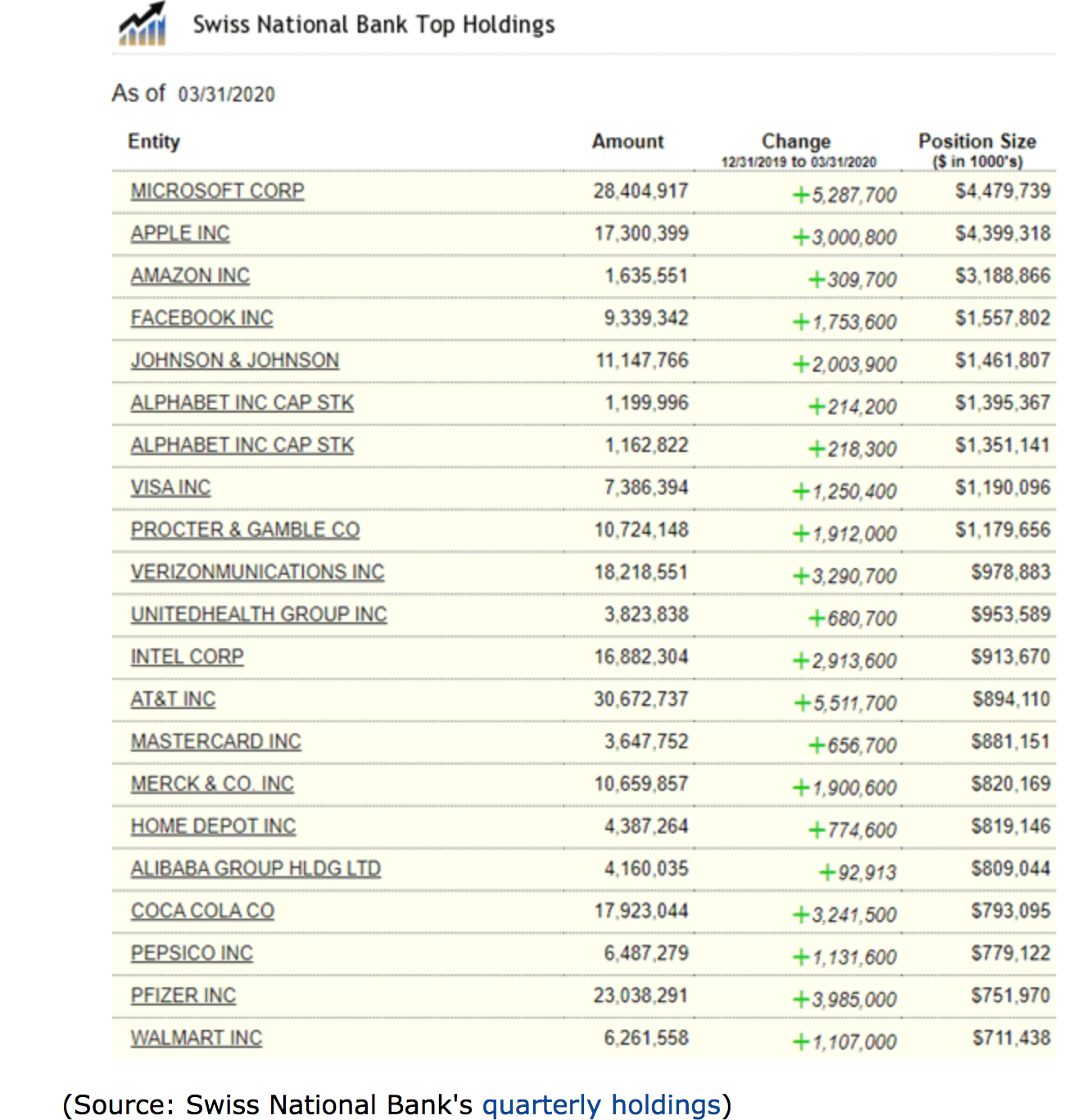

* Based on the latest Q1’20 holdings, the Swiss National Bank owns about $100 billion in U.S. stocks. The U.S. Fed is surely taking notes.

U.S. Federal Reserve Ready To Buy Stocks

According to the Federal Reserve’s website, they created a special purpose vehicle (SPV) in March 2020 and managed by BlackRock (BLK) to do the buying of bonds. Most people are well aware of the bond purchases that is already happening. You can view my previous videos on this. However, in the investment management agreement with BlackRock, most people missed the fact that the Federal Reserve also included language to allow them to transact in stocks as well. Essentially, the Fed is ready to go and buy stocks if truly needed. This is their hidden ace card.

In this video, I will be providing a background on the U.S. Federal Reserve’s readiness for buying U.S. stocks, what some financial professionals are saying about this, and also explain what this means for investors. So please stick to the end of the video to find out.

You can see that according to the Exhibit B, this is the power of attorney language for BlackRock to “manage, supervise, and direct the investments” for the Fed’s account. Clearly, the language in Exhibit B says, “transact in any and all stocks, bonds, cash held for investment and other assets.”

Scott Minerd’s Opinion — The Fed Will Likely Buy Stocks

Let’s see how well-known financial people are saying about this. Scott Minerd, Global Chief Investment Officer at Guggenheim Partner said in a recent CNBC article, that “a reckoning is coming, and soon. He expects the S&P 500 will retest its March 23 low of 2,237.40 over the next month, potentially crumbling to as low as 1,600.”

It should be noted that Minerd is one of the more bearish people on Wall Street right now. Scott Minerd further adds, “there’s a point where the Federal Reserve is going to have to pull out a bazooka,” Minerd said in an interview. “And I think the option of buying stocks on the part of the Fed is on the table.” Clearly, if the stock market does continue to fall due to sustained high unemployment rates, then it would erode confidence among consumers, small businesses and CEOs.

Janet Yellen’s Opinion — “Buying Stocks Wouldn’t Be A Bad Thing”

In early April, Janet Yellen (former Fed Chair) said, “Technically, the Fed does not have the legal authority to purchase stocks, although the US central bank should seek that power.” It is important to note that buying stocks would be a significant escalation in the Fed’s mission to avoid a depression – it is truly their last resort. “I frankly don’t think it’s necessary at this point,” Yellen said, “but longer term it wouldn’t be a bad thing for Congress to reconsider the powers that the Fed has with respect to assets it can own.”

Swiss National Bank & Bank Of Japan Have Already Been Buying Stocks

Some foreign central banks are already aggressively buying stocks in the market. The Bank of Japan owns more than 70% of Japan’s equity ETFs and has started buying since 2010. As well, based on the latest Q1’20 holdings, the Swiss National Bank owns about $100 billion in U.S. stocks.

On this holding, you can see that the Swiss National Bank actually owns well known mega-cap technology companies (see below picture). According to a recent article, as the stock market crashed by nearly 30% in March, the Swiss National Bank went on a wild spending spree, increasing its top 20 holdings by nearly 22%. The Swiss National Bank has to disclose its holdings of US-traded stocks via a quarterly 13F filing with the SEC.

Conclusion — What It Means For Investors

Overall, this article is to really show to investors that the Federal Reserve is ready to buy stocks based on the agreement they signed with BlackRock.

They are ready to act – yet there has really been no press coverage of this at all. What this means for investors is that the market is artificially “propped” up by the Fed. The Fed has reiterated multiple times that they will do “what it takes” to keep the market and economy afloat. The Bank of Japan and Swiss National Bank serves as a template for the U.S. Fed to copy should they really need to purchase stocks. The Swiss National Bank did not hesitate at all to purchase stocks in Q1’20, and this should be reassuring to U.S. investors if the Federal Reserve takes similar actions.

The reason why this would happen is if the market begins to fall precipitously, which would erode the paper value of people’s 401k accounts.

This would induce fear and panic, and even cause psychological mindset of not wanting to spend in the economy. Therefore, the Fed still has this ace card, yet to be played. At this current level, it may very well not have to play their final “ace card” in buying stocks.

Updated: 8-16-2020

Saudi Wealth Fund Moves Billions From Blue Chips To ETFs

Many of the stocks PIF targeted in the first quarter were trading at historic lows.

Saudi Arabia’s sovereign-wealth fund has sold shares valued at over $5.5 billion in several major multinational corporations just months after buying into them as the financial fallout from the coronavirus pandemic weighed on global stock-market prices.

At the same time, the roughly $300 billion Public Investment Fund chaired by the kingdom’s powerful Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, invested nearly $4.7 billion in exchange-traded funds focused on the real-estate, utilities and materials sectors, a U.S. filing showed.

PIF unloaded stakes worth more than half a billion dollars each in companies like Boeing Co., Facebook Inc. and Marriott International Inc., according to a filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

It had picked up the minority stakes in big corporates in the first quarter, highlighting a strategy of piling into global stocks even as the novel coronavirus and a crash in oil prices mean that Saudi Arabia’s financial position is now the most precarious in a decade.

The filings showed that in the second quarter PIF also sold positions in U.S. banks Citigroup Inc. and Bank of America Corp., as well as European energy firms BP PLC, Royal Dutch Shell PLC and Total SA, while buying more shares of cruise operator Carnival Corp. and concert promoter Live Nation Entertainment Inc.

Many of the stocks PIF targeted in the first quarter were trading at historic lows, bruised by the fallout from the coronavirus and rock-bottom oil prices that have battered stocks of energy companies. U.S. markets have broadly recovered in recent months, but it wasn’t clear from the sales information provided in the filing what sort of gains or losses PIF realized on its trades.

Tarek Fadlallah, chief executive of Nomura Middle East, the regional asset-management arm of the Asian investment bank, said the latest moves were unexpected.

“This suggests that the PIF is taking a more opportunistic ‘trading’, rather than a traditional strategic ‘buy-and-hold’ approach of most other SWFs,” he said in an email.

Prince Mohammed, the kingdom’s day-to-day ruler, tasked PIF in 2015 with diversifying the country’s economy away from oil by investing in companies and industries untethered to hydrocarbons.

While PIF has dipped into stocks in recent years, it has focused more on private equity, allocating capital to managers such as SoftBank Group Corp. Its record is mixed. The fund’s $45 billion investment in the Vision Fund has suffered losses, and the value of its pre-listing investment in Uber Technologies Inc. of $3.5 billion is also currently down.

Updated: 9-19-2020

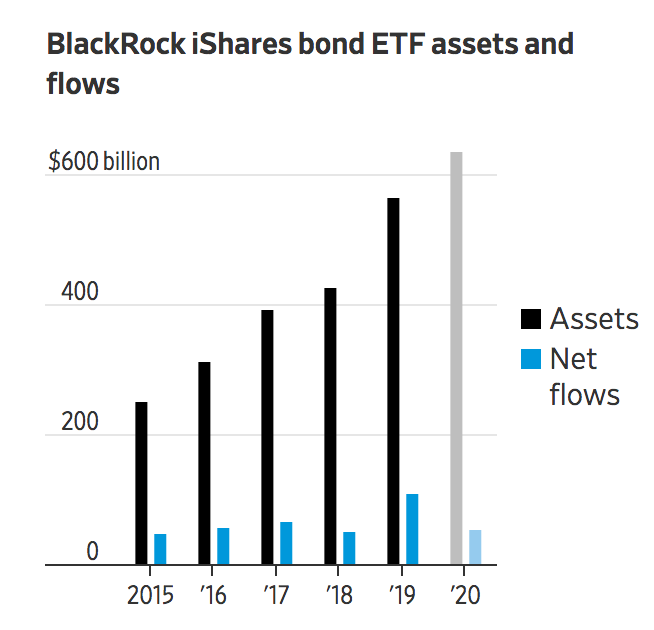

Fed Hires BlackRock To Help Calm Markets. Its ETF Business Wins Big

The central bank’s market intervention helped the largest U.S. provider of corporate bond exchange-traded funds get larger.

The Federal Reserve’s March commitment to deploy billions of dollars to prop up the economy was a boon for the company the Fed hired to help execute its plan: BlackRock Inc., BLK 1.55% the world’s largest asset manager.

In response to the pandemic-induced market collapse, the Fed promised to buy corporate bonds and exchange-traded funds that invest in collections of corporate debt.

The Fed had never bought ETFs or corporate bonds before. The central bank tapped BlackRock to help advise it and buy the bonds and funds on its behalf, though the central bank retained ultimate authority over what to purchase.

The Fed’s interventions worked as designed, stoking investor confidence and restoring market function—even before the central bank had bought anything at all. But one side effect was that many of the funds investors poured into were BlackRock’s own, making the giant firm an even bigger player in the exchange-traded-fund market.

In the days after the Fed’s announcement on March 23, traders jockeyed to figure out what funds the central bank might buy, and bought those funds themselves.

BlackRock’s share of assets increased in 27 funds Morningstar Inc. analysts deemed potentially eligible for the Fed program.

BlackRock’s share grew from 51% on March 20 to about 56% on July 23, when the Fed last bought ETFs, according to Morningstar.

The funds the Fed ultimately did buy became even more popular with investors, who put $48 billion into them in the first half of 2020, nearly twice the amount that went in the year before. BlackRock funds were especially popular: They took in $34 billion, about 160% more than in the first half of 2019.

“The unprecedented actions taken by the Fed during Covid-19 just accelerated the trend where the biggest products get bigger,” said Linda Zhang, chief executive of Purview Investments in New York.

A $7.3 trillion asset manager run by CEO Laurence Fink, BlackRock was already the largest provider of these kinds of ETFs, which are commonly used by big institutions to enter and exit markets cheaply.

BlackRock President Robert Kapito said that the firm’s gains were neither outsize nor surprising.

He said the firm’s most actively traded corporate bond ETFs draw institutions seeking rapid exposure to markets. This means its market share expands in periods when investors are more likely to take risks and contracts when they become more risk averse, he said.

“The success we’ve seen in recent years is the result of our strategic investments into the business over time,” he said. “We’ve repeatedly gained market share during periods when these investors increase their risk exposure.”

BlackRock’s advisory arm aiding the Fed is separate from BlackRock’s asset-management arm, which runs its ETF business.

The firm will receive modest compensation for its role assisting the Fed—a roughly $3 million fee for the six months ending Sept. 30, and $750,000 per quarter thereafter, according to BlackRock’s contract with the Fed. BlackRock will also collect fees on the small corporate bond portfolio it manages for the Fed. BlackRock isn’t charging any fees on ETFs and is rebating fees from its own iShares ETFs back to the Fed. The central bank limited the amount of BlackRock ETFs it would buy.

Of the 16 ETFs the Fed ultimately purchased, eight were BlackRock’s iShares funds. BlackRock, Vanguard Group and State Street Global Advisors made up 99% of the Fed’s ETF portfolio, valued at $8.7 billion as of August. Two remaining funds were managed by smaller competitors DWS and VanEck.

The thaw in markets meant the Fed only spent about $13 billion of the up to $750 billion it had designated for corporate-bond and ETF buying.

While BlackRock is set to earn a relative pittance from the Fed, it made millions in fees from other investors.

“Even if BlackRock waives its fees from the purchases that the Fed is making, the fact that it is associated with this program means that other investors are going to rush into BlackRock funds,” said Bharat Ramamurti, a member of the congressional body overseeing the Fed’s coronavirus stimulus programs, who also worked for Elizabeth Warren’s presidential campaign.

“BlackRock obviously generates fees from those flows. So the net result is that this is very lucrative for BlackRock,” Mr. Ramamurti said.

BlackRock’s popular ETF that trades under the ticker LQD saw $8.2 billion of inflows in the first seven trading days after the Fed’s March announcement, Morningstar estimates show. The Fed didn’t start buying any funds until May.

BlackRock charges 0.14% in fees for LQD, or $14 for every $10,000 invested.

Across all categories of iShares bond ETFs, beyond just corporate bonds, BlackRock’s revenue rose 11.5% to $261 million in the second quarter from the same period last year.

The Santa Monica, Calif., asset manager Angeles Investments bought about 90,000 shares of LQD in the two days after the Fed’s announcement.

“It’s not that complicated, really. The Fed says, ‘We’re buying this.’ OK, then, I’m going to buy it too,” said Michael Rosen, chief investment officer of Angeles Investments.

Mr. Rosen said he picked the fund because of its size and liquidity. His firm had also bought about 45,000 shares of LQD on March 16.

Columbia Threadneedle Investments snapped up seven million LQD shares in March, nearly doubling its position to about 4% of LQD’s shares outstanding, FactSet data show. Wisconsin’s state pensions system bought a million shares. Some actively managed BlackRock portfolios also increased their exposure to LQD and to several other bond ETFs managed by the firm, FactSet data show.

State Street published a list of seven potential candidates across State Street’s, Vanguard’s and BlackRock’s offerings—and the guesses were all correct, including BlackRock’s LQD.

“If I only had the same luck with picking fantasy baseball players,” said Matthew Bartolini, who heads Americas research at State Street’s ETF division.

Updated: 10-12-2020

Record $170 Billion Has Flooded Into Bond ETFs Thanks To Fed

Things were looking pretty bleak back in March for bond exchange-traded funds. The Covid-19 selloff created a liquidity crunch that drove their prices to trade at deep discounts to the value of the underlying assets. Skeptics questioned whether these products could ever be trusted again.

Then the Federal Reserve stepped in. On March 23, it announced that that it would begin buying corporate debt ETFs. This ignited a wave of front-running investments and served as a stamp of approval for the market sector.

A thank-you note to Jerome Powell may be in order. Flows into U.S. fixed-income products this year have surpassed the total for all of last year. New funds are coming down the pipeline. And investors are increasingly using corporate bond ETFs to bet on an economic recovery and hedge against what could be a volatile post-election season.

“The events from the onset of the pandemic have only accelerated the growth of fixed-income ETFs,” said Matthew Bartolini, head of SPDR Americas Research at State Street Global Advisors.

So far this year, inflows to bond funds total $170 billion, compared with $154 billion in all of 2019, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Of course, another sharp downturn could reopen a chasm between bond ETF prices and their underlying assets, and the Fed’s eventual unwinding of its holdings might spur distress. But the central bank hasn’t given indications about its exit timeline, so purchases for fixed-income funds remain strong.

The Fed has bought 16 different corporate bond ETFs, with purchases peaking in June at $4.2 billion, according to data from Bloomberg Intelligence. Investors anticipating the central bank’s moves added $28 billion to those products.

Two of the funds the Fed bought ended up topping the list of biggest sector gainers this year. BlackRock’s iShares iBoxx $ Investment Grade Corporate Bond ETF (LQD) is leading with $17.5 billion, while Vanguard’s Intermediate-Term Corporate Bond ETF (VCIT) has attracted $12.2 billion.

Even some without the Fed backing have seen stellar years. Vanguard’s Total Bond Market ETF (BND) and BlackRock’s iShares Core U.S. Aggregate Bond ETF (AGG) have added $12.1 billion and $8.2 billion, respectively.

“We’re already in record territory, and we’re likely to blow that record away, given the volatility headed into an election,” said Todd Rosenbluth, head of ETF and mutual fund research for CFRA Research.

Novel Uses

Investors have been shoveling money into U.S. government and mortgage-backed bond ETFs in the past month, anticipating further choppiness from uncertainties over fiscal stimulus and the presidential election outcome. Other strategies for bond funds recently include shorting high-yield securities and hedging long positions.

“There’s a variety of ways they can be used in portfolios, and I think that helps to draw a more diverse investor base,” said Dave Perlman, ETF strategist for UBS Global Wealth Management.

These ETFs also enable clearer price discovery in the less-liquid bond markets and make it easier for investors to amass a diversified portfolio of specific types of securities.

“Institutional investors are getting more comfortable using ETFs to gain more targeted exposure” instead of buying individual bonds, Rosenbluth said.

This, in turn, has created a flurry of new funds. So far this year, 39 fixed-income ETFs have begun trading, compared with 38 at the same point last year and 37 in 2018. Two new ones in 2020 — iShares 0-3 Month Treasury Bond ETF (SGOV) and Franklin Liberty U.S. Treasury Bond ETF (FLGV) — have already attracted $890 million and $423 million respectively.

Fed Hangover

Yet the good times may have their limits. The Fed stopped buying bond ETFs in August. And early birds who bought ahead of the Fed could start profit-taking.

Corporate-bond products might see up to $30 billion in outflows in the next month or two, according to Bloomberg Intelligence. The category lost $3.2 billion in September, but has regained $6.1 billion in October so far.

And bond ETFs haven’t converted everyone. Some investors still prefer purchasing the individual bonds.

Jim Paulsen, chief investment strategist for Leuthold Group, said that for high-quality bonds like Treasuries, he would rather just buy them directly, so he doesn’t have to worry about any fees. But he said that for complex formulas and diversifying holdings, the ETFs can come in handy.

“As you get into more credit risk or structure mortgages or prepay instruments, then I think ETFs can play a role,” he said.

Updated: 11-23-2020

Fed’s ETF Purchases Have Changed Markets Forever

The central bank’s corporate-bond facilities may expire on Dec. 31, but their legacy will inform investor behavior for years to come.

Last week’s public spat between Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell may have set an end date for the central bank’s unprecedented intervention in U.S. credit markets. But make no mistake, the legacy of this episode will most likely permanently change investors’ mindset during periods of crisis.

In particular, the Fed’s swift purchases of corporate-bond exchange-traded funds set a clear precedent for the type of policy response that traders can expect during the next period of economic distress — or what section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act calls “unusual and exigent circumstances.”

In contrast to the central bank’s Main Street Lending Program and Municipal Liquidity Facility, which didn’t get many takers, the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility revved up in a hurry and provided an even stronger backstop to financial assets than traders saw coming.

Recall that on March 23, the Fed unveiled the credit facility, explaining that it could buy high-grade corporate bonds and exchange-traded funds tracking that market.

Then on April 9, it amended the parameters to allow for purchases of double-B rated junk bonds as long as the company had investment grades as of March 22. Just for good measure, it also added a provision that it could buy high-yield ETFs, even though that seemingly defied explanation.

By May 12, the facility was gobbling up ETFs, executing 35 separate trades totaling $305 million, according to disclosures to Congress. The next day it bought $330 million. And on and on it went until July 23, the last day the central bank added corporate-debt ETFs.

By that time, it had switched over to individual bonds, seemingly by skirting the law and creating an entirely new class of eligible assets called “Broad Market Index Bonds.” Those purchases have continued unabated through at least Oct. 29, when the Fed bought debt of Amazon.com Inc., Kroger Co. and Visa Inc., among others.

It’s telling that the Fed plunged first into ETFs through secondary-market purchases. The central bank sought to ease financial conditions as quickly as possible, and corporate-bond ETFs, which trade transparently in real time and represent the broad market, are an easy way to do that. In fact, by the time the facility got around to buying individual bonds on June 16, the yield on the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Corporate Bond index was already at a record low of 2.18%.

The ETF purchases were so successful, and so relatively effortless, that such a strategy is not only likely to serve as the blueprint for the next corporate credit crunch, but it also raises the obvious prospect of the Fed going even further during a market meltdown and buying another financial asset that trades on exchanges: U.S. stocks.

Powell didn’t exactly slam the door on this option when Politico’s Victoria Guida brought it up during his July 29 press conference. She asked: “What is the scope of your authority under 13(3)? What type of assets are you allowed to buy? Could you buy equities through an SPV, for example?”

Here’s His Response (Lightly Edited For Clarity):

We haven’t done any work or thought about buying equities. But we’re bound by the provisions of 13(3), which requires that we make programs or facilities of broad applicability, meaning it can’t just be focused on one entity. It has to be a broad group of entities. There’s a lot in 13(3) about the solvency of the borrowers.

Remember, it was rewritten or amended after the financial crisis, and it was written in a way that was meant to make it challenging to bail out large financial institutions. There was a lot in there to make sure that they were going to be solvent and things like that. So we have to meet those requirements. We haven’t looked and tried to say, “what can we buy?” and “let’s make a complete list.”

None of this seems to preclude equity ETFs. Certainly, indexes tracking the broad stock market could include companies that are struggling to stay solvent. But in April, the iShares iBoxx High Yield Corporate Bond ETF (ticker: HYG) had 11.3% of its assets in bonds rated triple-C or double-C. The Fed’s facility now has a $325 million stake in it.

Guida even followed up to give Powell one more out to differentiate the Fed from the Bank of Japan, which has been buying equity ETFs for several years: “Is it generally supposed to be primarily directed at debt instruments, since you talked about borrowers?” Powell replied:

The statute doesn’t say that, but, yeah, you could read the statute that way if you want. Honestly, we haven’t tried to push it to, you know, what’s the theoretical limit of it. I mean, I think, clearly, it’s supposed to replace lending.

That’s really what you’re doing. You’re stepping in to provide credit at times when the market has stopped functioning. That’s fundamentally what you’re doing with 13(3). And so I think you’ve got to sort of work within that framework.

In truth, the secondary-market credit facility never functioned like this once it was operational. It’s hard to see how buying ETFs, or even individual bonds on the open market, replaces lending. It mostly serves to prop up debt prices to encourage private lenders to engage in public markets. Ironically, the Fed program that would have actually stepped in to provide direct credit to corporations, the Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility, has never been used.

Mnuchin noted on Friday that Fed officials “always like to keep things open.” He added that while some other facilities would be extended for 90 days, “we don’t need to buy more corporate bonds.”

He’s right on both counts. As of the end of October, the Fed holds $8.6 billion of corporate-bond ETFs and $4.8 billion of individual securities. While that’s still just a fraction of the facility’s potential firepower, adding more debt in the secondary market with yields at record lows isn’t serving as a “backstop” in any sense of the word.

However, I’ve argued for extending the lifelines for municipal and Main Street borrowing precisely because they’re only ever used by those who need it the most, like New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which is facing a fiscal reckoning.

It’s still unclear how much of Mnuchin’s decision was driven by prudence versus politics. Either way, Powell said in a letter released late Friday that the Fed would return the money to Treasury as asked, meaning the central bank’s corporate credit facilities will be shut down after New Year’s Eve, earlier than it anticipated.

That shouldn’t bother investors too much. Instead, they’ll likely take comfort in knowing what the central bank and Treasury are capable of in credit markets during the next unforeseen crisis and how that’s just a stone’s throw away from directly intervening in equities. For better or worse, the “Fed put” is here to stay.

Updated: 12-01-2020

Record-Shattering Flows Into Stock ETFs Leave Bond Funds In Dust

Equity exchange-traded funds have overtaken their fixed-income peers for inflows this year thanks to November’s epic stock rally.

After lagging bond funds for most of 2020, ETFs tracking equities lured a record $81 billion last month, bringing their total haul for the year to $196 billion, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. That catapulted them ahead of fixed-income funds, which attracted $17 billion and have a tally of $192 billion.

Investors are redeploying cash into stocks following a series of breakthroughs in the race for a Covid-19 vaccine and amid mounting optimism for growth. Beaten-down areas of the market have benefited the most, with small caps and energy shares posting their strongest months on record in November. Global equities notched their largest monthly gain since at least 1988, while multiple major benchmarks are at or near all-time highs.

“The prospect of multiple Covid-19 vaccines on the horizon, combined with diminished uncertainty over the presidential transition, boosted investor appetite for stocks. Equity ETFs reflected that,” said Nate Geraci, president of investment-advisory firm the ETF Store. “Given that November was a historic month for stocks and with some investors questioning the risk/reward profile of bonds, it’s no surprise to see equity ETF inflows surpass bond ETFs.”

About 95% of stock funds posted gains last month, with around two-thirds of them beating the S&P 500.

The clear winner from the renewed appetite has been Vanguard Group thanks to its line-up of low-cost products. The $189 billion Vanguard Total Stock Market ETF (VTI) has seen the most inflows this year at $27.2 billion, followed by the $177 billion Vanguard S&P 500 ETF (VOO), which has absorbed $26.7 billion.

They may have been overtaken for flows, but it remains a banner year for fixed-income ETFs.

After a violent selloff created a liquidity crunch across bond markets, the Federal Reserve announced in March that it would buy ETFs for the first time. Billions poured into credit funds in the aftermath, curing deep discounts and putting them on track for a record 12 months.

The Fed has only purchased about $8.7 billion worth of corporate bond ETFs in total, but the central bank’s presence has been enough to give the products a stamp of approval. BlackRock Inc.’s $58.6 billion iShares iBoxx $ Investment Grade Corporate Bond ETF (LQD) has attracted $18.3 billion so far this year, putting it in third place behind VTI and VOO.

Total assets in U.S. bond ETFs stand at roughly $1.1 trillion, while their stock counterparts hold $4 trillion. If the equity rally gains further steam, that gap could grow even bigger.

“Flows follow performance,” said Dan Suzuki, deputy chief investment officer at Richard Bernstein Advisors. “Investor confidence over the past couple months has also benefited greatly from positive vaccine news.”

Updated: 6-28-2021

Clean Energy ETFs Take A Hit, but Money Keeps Flowing In

Exchange-traded funds that track renewable-energy indexes have posted double-digit declines this year.

Investors have lost a bundle this year betting on solar-panel and wind-turbine makers. Their response: to double down.

A year ago, green stocks and the funds that track them rallied tremendously in the aftermath of the market’s recovery from a pandemic-induced swoon. Solar-panel and wind-turbine companies were among firms benefiting from a surge of investor- and consumer-driven demand for renewables, despite many being small unprofitable ventures.

This year, returns are trailing the broader stock market. That is thanks, in part, to stocks having run so far and uncertainty around the Federal Reserve’s interest-rate course and how its actions may ultimately affect growth stocks.

Exchange-traded funds that track renewable-energy indexes have posted double-digit declines so far this year. BlackRock’s iShares Global Clean Energy ETF has fallen 18% since December; Invesco Ltd. ’s popular Solar ETF has posted a 17% decline.

Even so, money continues to pour in. Professional money managers and individual traders alike have invested $6.2 billion into green-energy ETFs so far this year, according to data from Refinitiv Lipper. The inflows are on course to eclipse last year’s record $7.2 billion.

Index makers and asset-management firms say that, for now, large pullbacks in share prices don’t reflect investors’ desire to bet on green companies.

“It’s an area where we see continuous demand,” said Ari Rajendra, a senior director of strategy and volatility indexes at S&P Dow Jones Indices.

At BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, clean energy funds reported $2.7 billion in inflows so far this year and $1 billion into a European clean-energy fund, according to FactSet. Interest was so high that S&P had to broaden its clean-energy benchmark used by BlackRock funds to fix the problem of having too much money in mostly small, hard-to-trade companies.

Such changes don’t happen often, said S&P’s Mr. Rajendra, but intense demand from investors warranted the index’s revamp to 82 stocks from just 30. The firm also lowered the criteria for the inclusion of stocks, among other things.

Ross Gerber, chief executive of Gerber Kawasaki Wealth and Investment Management, thinks renewable-energy stocks, from solar-panel makers to manufacturers of alternative batteries, will eventually transform transportation and other facets of everyday life.

Mr. Gerber has put more client cash into Invesco’s clean-energy fund, contributing to the $446 million of total inflows into ETF so far this year. He shuns oil stocks, which are among the stock market’s best performers this year.

“The more speculative the stock, the higher the valuation. But in this market, people care more about fantasy than reality,” said Mr. Gerber. “So with solar, you have a little bit of the fantasy in there, too.”

Invesco’s solar ETF jumped 233% in 2020, while BlackRock’s global clean-energy fund soared 140%—easily the best years ever for both as valuations of green stocks climbed to dizzying heights.

Although both funds have declined in the year to date, valuations are elevated. Invesco’s solar ETF trades at a forward price/earnings ratio of 36, versus 21 for the S&P 500, according to FactSet.

Meanwhile, clean-energy companies trade at a 70% premium to traditional energy companies based on a ratio of enterprise value to earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization, a standard valuation yardstick, strategists at Bank of America said. They noted this valuation was down from highs earlier this year but still well above the five-year average.

With stocks pricey, they and funds that track them may be more vulnerable to market or political changes. Their allure may dim, for example, if the Fed begins to raise interest rates earlier than expected, taking some of the shine off growth stocks.

Or volatility could increase if there are hiccups for a $1 trillion infrastructure plan agreed to by President Biden and some U.S. senators. Green stocks rallied last year after Mr. Biden won November’s presidential election, as investors bet the new administration would hasten the U.S.’s transition toward wind and solar energy and away from fossil fuels.

Investors already are experiencing some of that volatility. Clean energy stocks have rallied alongside growth stocks in recent weeks. Invesco’s solar fund is up nearly 11% over the past month, while BlackRock’s ETF has added 2.2%.

The willingness of investors to continue pouring money into this part of the market shows they are positioning for a potential longer-term readjustment of the energy sector and economy.

Rene Reyna, head of thematic and specialty product strategy at Invesco, said expectations are premised on a belief that technology will eventually bring the cost of batteries, solar panels and other green efforts down enough to garner wider adoption—and big profits. In that sense, clean energy is the “hope trade,” he said.

Updated: 3-31-2022

Federal Reserve Pumps Billions Into French Global Bank, BNP Paribas

As thousands of businesses were forced to close in the U.S. as a result of the coronavirus outbreak in March of 2020, and millions of Americans were financially struggling, the Federal Reserve was pumping what would become a cumulative $3.84 trillion in secret repo loans into the U.S. trading unit of the giant French global bank, BNP Paribas, in the first quarter of 2020.

The repo loan market is where banks, brokerage firms, mutual funds and others make loans to each other against safe collateral, typically Treasury securities. Repo stands for “repurchase agreement.” The Fed only comes to the rescue of this market when there is a liquidity crisis and Wall Street firms are backing away from lending to each other.

September 17, 2019 was the first time the Fed had to intervene in the repo market since the financial crisis of 2008 and it was months before the first case of COVID-19 was discovered anywhere in the world.

BNP Paribas is not just any ole global bank. It’s the bank that the U.S. Department of Justice fined $8.8 billion in 2015 for flouting U.S. sanctions, covering its tracks, and pleading guilty to a criminal charge.

What may have led to the scramble for money by BNP Paribas Securities is – wait for it – risky derivatives, the same financial weapons of mass destruction that blew up the U.S. financial system and economy in 2008 and led to the biggest bailout of Wall Street in history by the Fed.

The BNP Paribas information comes from a repo loan data dump by the New York Fed this morning – the regional Fed bank that handled all of these secret repo loans from their inception on September 17, 2019 to July 2, 2020.

The Fed has withheld the release of the names of the banks that got these massive loans for two years but is now forced to release them under the provisions of the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation of 2010. This morning’s data covers the first quarter of 2020.

The Fed has previously released the banks’ names for its repo loan bailouts from September 17, 2019 through December 31, 2019 – also after a two-year lag. All of the repo data released thus far is available here. (You have to manually remove reverse repo data before summing the repo columns.)

Mainstream media has heretofore instituted a news blackout on the names of the banks that received the repo loan bailouts and the Fed’s data releases. (See our report on January 3 of this year: There’s a News Blackout on the Fed’s Naming of the Banks that Got Its Emergency Repo Loans; Some Journalists Appear to Be Under Gag Orders.) As of 4:00 p.m. today, we see no other news reports on this critical information that the American people need to see.

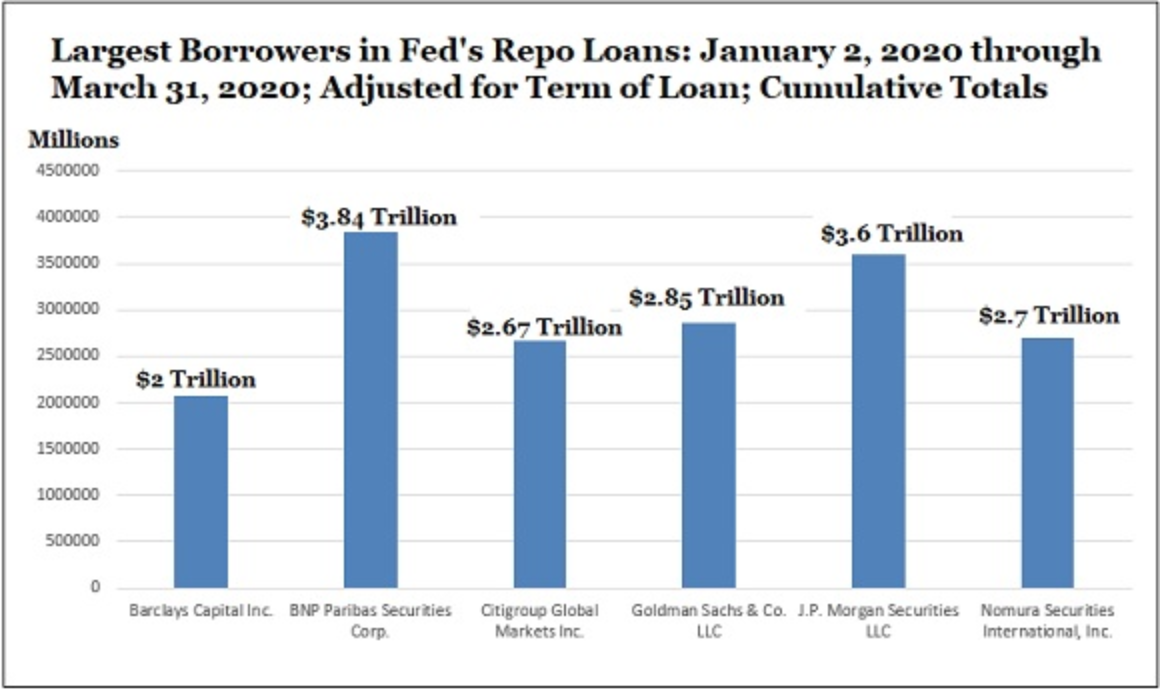

The Fed data released this morning shows that the trading units of six global banks received $17.66 trillion of the $28.06 trillion in term adjusted cumulative loans, or 63 percent of the total for all 25 trading houses (primary dealers) that borrowed through the Fed’s repo loan program in the first quarter of 2020.

The normal repo loan market is typically an overnight (one-day) loan market. The Fed started out with one-day overnight loans but then periodically also added 14-day, 28-day, 42-day and other term loans.

We had to adjust our cumulative tallies to account for these term loans in order to get an accurate picture as to who was grabbing the bulk of these cheap loans from the Fed.

For example, let’s say a trading firm took a $10 billion loan for one-day but on the same day took another $10 billion loan for a term of 14 days. The 14-day loan for $10 billion represented the equivalent of 14-days of borrowing $10 billion or a cumulative tally of $140 billion.

If we simply tallied the column the New York Fed provided for “trade amount” per trading firm, it listed only $10 billion for that 14-day term loan and not the $140 billion it actually translated into.

The trade amount column for the first quarter of 2020 comes to $4.4 trillion while the term-adjusted total comes to $28.06 trillion.

The Fed’s audited financial statements show that on its peak day in 2020 the Fed’s repo loan operation had $495.7 billion in loans outstanding. On its peak day in 2019, the Fed’s repo loans outstanding stood at $259.95 billion.

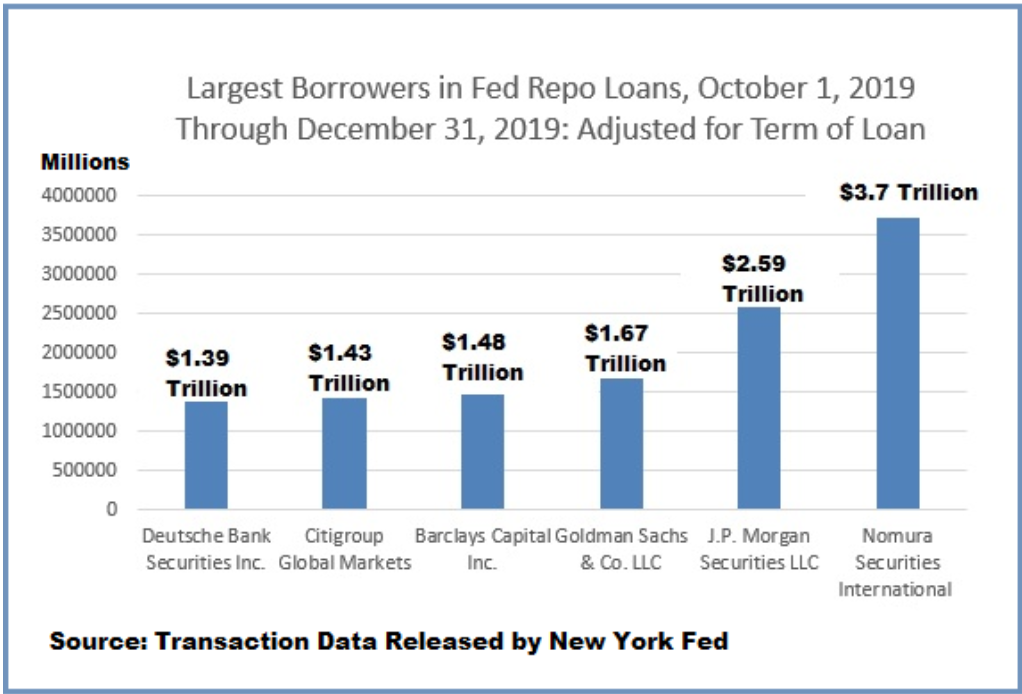

Per the chart below, when we crunched the numbers for the fourth quarter of 2019, the trading unit of a Japanese firm, Nomura, had received the lion’s share of the largesse from the Fed.

In both the last quarter of 2019 and first quarter of 2020, the trading units of three of the banks in the U.S. with the largest exposure to risky derivatives were among the six largest borrowers from the Fed: J.P. Morgan Securities, Goldman Sachs, and Citigroup.

The Senate Banking Committee and the House Financial Services Committee need to subpoena documents and hold serious hearings into these perpetual bailouts by the Fed and learn just how interconnected these trading firms are via risky derivatives and counterparty exposure.

Officials at both the Fed and the New York Fed need to be put under oath at these hearings. JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs and Citigroup all own federally-insured banks backstopped by the U.S. taxpayer.

The public’s money is on the line and the public needs to fully understand what’s going on here.

Updated: 4-6-2023

BlackRock Can’t Wait Forever To Sell $114 Billion Of Failed Banks’ Assets

* The Amount Of Supply Coming Is Formidable, Analysts Cautioned

* Assets From Failed Lenders Signature, Silicon Valley Bank

BlackRock Inc., the chosen seller of a pile of securities once held by failed banks, faces a dilemma between flooding the market and risking higher costs to hold the debt.

The selection of a top-tier manager by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and assurances that the sales would be “gradual and orderly,” helped assuage any concerns the government might choose to quickly offload the securities, according to analysts.

Regulators amassed the assets, mostly in the form of mortgage backed securities, from failed lenders Signature Bank and Silicon Valley Bank.

Prices of MBS were only modestly lower early Thursday afternoon against Treasury and Secured Overnight Financing Rate hedges, suggesting traders had mostly anticipated the FDIC’s strategy to eventually offload the debt.

BlackRock and the FDIC declined to comment.

Still, BlackRock doesn’t have an unlimited amount of time to conduct its sales. The FDIC hasn’t given a timeline for the sales, but as a practical matter it can’t wait forever.

It’s paying the Federal Reserve interest on credit lines to hold the securities, and holding the assets a long time brings other difficulties.