Cold War Games: U.S. Is Unprepared To Test The Waters In Icy Arctic (#GotBitcoin)

Navy explores expansion of operations in far North, going head-to head with rivals Russia and China. Cold War Games: U.S. Is Unprepared To Test The Waters In Icy Arctic (#GotBitcoin)

The Navy is planning to expand its role in the Arctic as climate change opens up more ocean waterways and the U.S. vies with great-power rivals Russia and China for influence in the far north.

A Navy warship will sail through Arctic waters in coming months on what’s known as a freedom of navigation operation, or FONOP, said Navy Secretary Richard Spencer in an interview with The Wall Street Journal this week. It will be the first time the Navy has conducted such an operation in the Arctic.

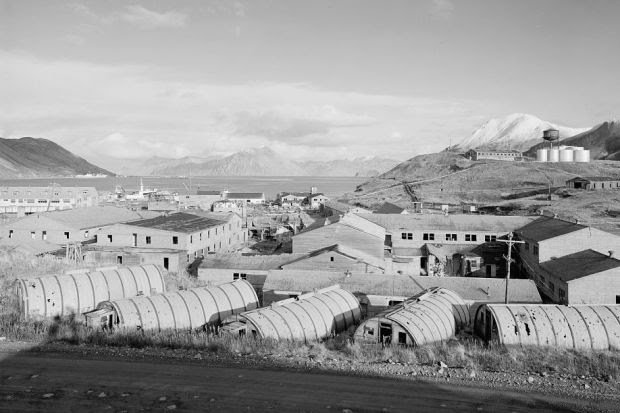

The Navy also is planning to station resources in Adak, Alaska, which would mark a return to the onetime World War II and Cold War base that operated from 1942 to 1997, when U.S. troops were withdrawn. The new detachment could include surface ships and P-8 Poseidon patrol and reconnaissance aircraft, he said.

“The concept is, yes, go up there,” Mr. Spencer said, adding that plans for new Arctic operations are in early stages. “We’re developing them as we speak,” he said.

The Arctic has become a markedly more contentious military and commercial environment as the changing climate has led to greater ice melt in the summer, opening more navigable waterways and leading to greater sea traffic in once-impassable lanes.

The National Snow and Ice Data Center found that 2018 saw the third-lowest Arctic ice level since satellite data collection began in the late 1970s, part of an adverse trend the center says threatens to further accelerate global warming and negatively affect climate patterns.

This could open up more trans-Arctic maritime routes, according to the Government Accountability Office, allowing exploration of untapped petroleum reserves and threatening the borders of countries once insulated by thick ice off their coasts.

The U.S. and allied militaries have used freedom of navigation operations around the world to assert the rights of ships from the U.S. and elsewhere to operate freely in waterways where there are territorial disputes, hoping to discourage or counter excessive claims.

Dozens of such operations in the South China Sea have targeted excessive Chinese maritime claims around islands and outposts across the region.

The Arctic mission will be the first time the U.S. Navy will undertake a FONOP in the Arctic, according to Cmdr. Jereal Dorsey, a Navy spokesman. Mr. Spencer said that the planning hasn’t yet addressed which ports would be visited or which ship will be used.

Russia has long worked to develop its Arctic capabilities because of its lengthy northern coastline and use of Arctic waters for trade and national defense, including establishment of military bases.

China, which has declared itself a near-Arctic power, issued a comprehensive Arctic policy last year that included a desire to build a “polar silk road” and to ensure its freedom to operate in the region.

Adak, which sits at the end of the Aleutian Islands near Russia, once served as a U.S. naval facility and still has a functioning airstrip used for commercial flights. The base was closed in the 1990s as part of the Base Realignment and Closure Program, better known as BRAC.

The decommissioned naval station was taken over in 2003 by the Aleut Corporation, founded in the 1970s to settle Alaska-native claims against the federal government.

With only a few thousand acres of the island still under government control, the Navy is currently in talks with the corporation, Mr. Spencer said. The Aleut Corporation didn’t respond to a request for comment on the matter.

The Navy’s planning is part of a broader move by the U.S. military to expand its influence in a region it has discounted, according to experts and military officials, and doing so is likely to pose a series of challenges.

Expanded military operations in the far north will require coordination with the Coast Guard, which handles a large portion of search-and-rescue missions and other U.S. surface capabilities in the Arctic. Mr. Spencer hasn’t said whether the Navy plans to move into some of these roles, but has said the Navy will work with the Coast Guard.

The Coast Guard also operates the only U.S. icebreaker in the region, a cause of concern among some lawmakers and defense officials because Russia operates dozens of icebreakers and the Chinese are building a fleet of such vessels.

The most recent U.S. defense budget includes authorization for new icebreakers, though the first one won’t be ready for use for years.

Ships that regularly sail in icy waters must be ice-hardened or winterized, to withstand the pounding and stress of thick ice and cold temperatures.

The Navy’s current fleet hasn’t been designed to operate in icy waters, the GAO said, but some experts and lawmakers have said the issue will have to be addressed.

The Navy is preparing changes to its official Arctic operations policy to include a broader focus on surface warfare, Mr. Spencer said. Existing policy focuses in large part on the Navy’s submarine and air patrol capabilities—not surface navigation.

Sen. Dan Sullivan (R., Alaska) said in an interview that surface navigation was important to emphasize the U.S. role as an Arctic nation.

“I’ve been pressing them to do something—not just with submarines,” Mr. Sullivan said. “It kind of defeats the purpose if you can’t see it.”

The Navy has moved to expand its footprint in the Arctic region in other ways recently. It launched what officials called the Second Fleet in August to focus on the North Atlantic and on expanding Marine Corps training for extreme cold-weather operations.

Currently, 600 Marines are training in Norway, with that country’s forces, and are preparing for land warfare in Arctic conditions, part of a longstanding commitment to such operations.

The coming Arctic freedom of navigation operation and plans for expanded missions in the far north are planned, in part, to better understand how to work and operate in the extreme cold, Mr. Spencer said.

“We’ve got to get up there and learn,” he said. “There’s no other way to do it.”

Updated: 7-29-2020

U.S. Names Arctic Policy Czar To Keep Tabs On China, Russia

Career diplomat James DeHart tapped to bolster the U.S. position in the Arctic, including repelling Beijing’s advances.

The State Department has tapped a career diplomat to coordinate efforts to bolster the U.S. position in the Arctic, including repelling China’s advances and capitalizing on commercial opportunities there.

James DeHart begins work Wednesday as the first U.S. coordinator for the Arctic region, representing the State Department in a Trump administration campaign encompassing several U.S. government departments and agencies.

He will report directly to Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Deputy Secretary Stephen Biegun, advising them on Arctic policy and engaging other Arctic nations in regional talks.

“A year or two from now, I think people are going to look back on the period of time that we’re in now and recognize it as a pivot point for us on the Arctic,” Mr. DeHart said in an interview. “We’re launching a comprehensive and integrated diplomatic strategy and engagement with the Arctic.”

Ice melt due to climate change has U.S. officials, as well as China and Russia, eyeing opportunities for resource extraction and shipping. Meanwhile, other regional powers have focused on the dangers posed by climate change—a discrepancy that hindered consensus at last year’s Arctic Council meeting.

In that context, the U.S. aims to maintain the Arctic as a site of peaceful cooperation, to guard against threats to national security, Mr. DeHart said, and to support economic growth and development in a manner consistent with international norms and “responsive to the needs of the local communities, including the indigenous communities throughout the Arctic.”

In a speech at the Arctic Council meeting last year in Rovaniemi, Finland, Mr. Pompeo warned against Chinese encroachment in the region and challenged Beijing’s assertion of its status as a “near-Arctic” state.

More recently, a Chinese state-owned firm’s purchase of a gold mine in the Canadian Arctic has raised alarm.

China’s pursuit of what its officials have referred to as the Polar Silk Road is cause for concern, Mr. DeHart said, noting that Beijing’s approach to infrastructure investment elsewhere is “a model that doesn’t fit well into the Arctic, from our perspective and I think from the perspective of our close partners in the region.”

Beijing has acknowledged that Chinese territory doesn’t touch the Arctic Circle, but says China is a stakeholder in Arctic affairs and has an interest in developing shipping, carrying out scientific research and exploiting the region’s oil, gas, minerals, fisheries and other natural resources.

By contrast, Russia is an Arctic power, and has collaborated with the U.S. and other countries in the region on search and rescue, pollution, and disaster response, Mr. DeHart said.

Deteriorating relations with Russia since its 2014 invasion of Ukraine have complicated matters, and Moscow is “becoming increasingly active” in the Arctic, including on security issues, he said.

The U.S. aims to maintain the region as a zone of international cooperation, but also recognizes that “the Arctic is NATO’s northern flank,” he said.

Noting that the department’s Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs has most of the Arctic nations in its portfolio and the Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs works on the “soft side” of Arctic issues, Mr. DeHart said, “I don’t plan to crowd anybody out.”

The creation of the post is the latest in a series of administration actions on the Arctic, including the White House’s plans to acquire a fleet of icebreakers; the June 10 reopening of the U.S. consulate in Nuuk, Greenland; and Mr. Pompeo’s recent meetings in Copenhagen with the Danish, Greenlandic and Faroese foreign ministers.

Mr. DeHart has held senior posts in Washington and abroad during his 28 years in the foreign service, including as deputy chief of mission in Norway and as assistant chief of mission in Afghanistan. He most recently served as a senior adviser for security negotiations and agreements in the department’s political-military affairs bureau.

In that capacity, he represented the U.S. in negotiations with South Korean officials over cost-sharing for the American military presence on the Korean Peninsula.

Recent U.S. actions are part of a long-term plan for the region, Mr. DeHart said, as the nation’s interests in the Arctic are ongoing.

“Our involvement is not a flash or a moment in time,” he said. “This is really an enduring commitment here that we have to the region, and I think that we’re all going to see this sustained.”

Updated: 10-11-2020

Russia’s Siberian Waters See Record Ship Traffic As Ice Melt Accelerates

The Northern Sea Route is becoming a highway to move Russia’s oil and natural gas exports while some global carriers shy away.

The Arctic has gone through its warmest summer on record, and with the ice melting, more ships than ever are sailing along Russia’s Siberian coast, underscoring its role as a growing energy transport corridor and potential as a new ocean trade route.

The Northern Sea Route, which runs from Alaska to the Baltic Sea, counted 71 vessels and 935 sailings across the waterway from January to June this year, according to the NSR information office.

That was up by double digits from the same period a year ago and a big increase from the 47 vessels and 572 voyages in the same period of 2018.

The mostly frozen seaway is used in warmer seasons to move some of Russia’s energy exports to overseas markets. Container ships and general cargo vessel operators also have used the route to move goods between Asia and Europe as it cuts an average 10 days of sailing time compared with the standard route through the Suez Canal.

Freight transport on the NSR is at its highest from July to November. Some sailings also take place in the rest of the year, and the Russian government expects largely ice-free year-round trips starting in 2024.

“There are many more ships because the ice is thin and you can sail without the help of icebreakers,” said Arne O. Holm, editor in chief of the Norway-based High North News, which monitors the NSR. “The NSR needs a lot of investment to attract bigger cargo vessels, but activity is picking up, and if the ice keeps melting it will be another option to move cargo from northern China to Europe.”

The National Snow and Ice Data Center, a private science research group supported by U.S. government agencies, said in September that this summer was the warmest on record in the Arctic, with the extent of sea ice across the entire Arctic shrinking to 3.74 million square kilometers, or 1.44 million square miles.

That’s not much more than half the average ice cover of 6.7 million square kilometers measured from 1979 to 2000.

“There was no ice at all across the coastline in September, no need for icebreakers or ice-hardened vessels,” said Nikos Papalios, a mechanic on a crude tanker that sails the NSR.

“It stayed above freezing for 10 days, from the port of Sabetta to the Bering Strait, and it was pleasant to sit on the deck. It felt out of place,” Mr. Papalios said.

Most vessels operating in the NSR are natural gas carriers and oil tankers carrying exports to European and Asian customers from Novatek’s Yamal liquefied natural gas project and Gazprom’s Novy Port crude oil project at the Yamal Peninsula along Russia’s northern coast.

These heavily reinforced ships are built to move through ice-filled waters and can cost more than $200 million each, more than twice the price of similar-size ocean vessels.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has said the NSR will be key to develop the Arctic and become a global transport route.

The Russian government expects cargo volumes across the waterway will reach 32 million metric tons this year, up 78% from 18 million metric tons in 2018. Novatek expects to ship about 52 million metric tons of LNG a year by 2030.

Updated: 5-23-2021

Arctic-Superpower Jostling Heats Up As Russia Takes On Key Role

Russia’s Sergei Lavrov claimed this week that “this is our land and our waters” as NATO allies boost military activity.

A battle of words between top Russian and U.S. diplomats this week is the latest sign of rising tensions between superpowers racing to seize Arctic resources made more accessible by climate change.

Ministers gathering in the Icelandic capital Reykjavik for a meeting of the Arctic Council weren’t due to discuss security. But the issue dominated conversations on the sidelines after Russia’s Foreign Affairs Minister Sergei Lavrov declared ahead of the summit that the Arctic “is our land and our waters.”

“We are especially concerned with what’s going on close to our borders,” Lavrov said on Thursday after journalists asked him about what Russia sees as increased U.S. military activity in the region. “We are going to undertake necessary measures in order to ensure our security, but our priority is to ensure dialogue.”

At the summit this week, which marked Iceland’s handover of the Arctic Council presidency to Russia for the next two years, most representatives called for the eight-nation body to remain focused on peaceful cooperation. But Lavrov signaled that Russia could take a different approach.

“Within the next two years we will create proper conditions so proper security will be part of the work of the Arctic Council,” he said. “We believe we can revitalize this mechanism if we decide so.”

The Arctic is one of the regions most affected by climate change and is warming more than twice as fast as the rest of the world.

Ice that used to cover the region’s waters for most of the year is shrinking and thinning. That’s opening new shipping routes and creating the prospect of easier access to once-trapped resources such as natural gas, oil and minerals.

Superpowers including Russia have rushed to claim some of these assets, leading to a stronger military presence that has resulted in a series of confrontations.

Last year, Russian planes buzzed U.S. fishing boats on the northern Bering Sea during a military exercise. In February, the U.S. deployed bombers to Norway for the first time, strengthening its presence in the region, and the two countries signed a new agreement in April to boost military cooperation.

“The Arctic as a region for strategic competition has seized the world’s attention, but the Arctic is more than a strategically- or economically-significant region” U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken said at the Arctic Council’s meeting on Thursday. “Its hallmark has been and must remain peaceful cooperation.”

The council, which gathers the eight Arctic nations— Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the U.S.—as well as indigenous peoples, has no mandate to address security matters.

These used to be negotiated at a separate Arctic Security Forces Roundtable, but Russia was removed from that forum, as it was from the Group of Eight advanced economies, following its annexation of Crimea from Ukraine in 2014.

The region doesn’t have a history of military conflicts because it’s difficult to access and its harsh climate makes it hard to position soldiers there. That’s changed as ice melts and countries try to get a foothold in the area, said Kate Guy, a senior fellow at the Council on Strategic Risks, a Washington-based nonprofit.

The Arctic is home to about 30% of the world’s undiscovered but recoverable gas reserves and 13% of undiscovered oil reserves, according to a report co-authored by Guy that was published this week.

Private shipping activity has increased 25% in recent years. Having more tankers and fishing boats in the waters could lead to more accidents, with search and rescue operations often performed by the military, the report found.

Russia is making the so-called Northern Sea Route, which runs along its Arctic coastline, a key part of its strategy to boost natural gas exports to Asia. At the same time, China has signaled its interest in small islands such as Svalbard, Guy said.

Armed forces are also upgrading their facilities in the region as permafrost, the frozen ground that covers most of Arctic land, thaws. The U.S. Department of Defense has already requested over $1 billion to retrofit and repair three Alaskan bases in the past five years, according to the report.

“We’re concerned about the level of recent angry and provocative rhetoric,” James Stotts, president of the Inuit Circumpolar Council in Alaska, said at the summit. “We don’t want to see our homeland turned into a region of competition and conflict, we don’t wish to see our world overrun with other people’s problems.”

Updated: 5-24-2021

As The Arctic Heats Up, How To Keep The Peace

Global warming has increased human activity at the top of the world, and fueled interest from non-polar China. How it’s overseen must reflect that.

Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, back in 1987, called for the Arctic to be a “zone of peace” — and it has been. Yet warmer temperatures are heralding ice-free summers, opening up all sorts of economic opportunities from potential oil and gas riches to new shipping routes.

Military might is being cranked up, too. Decades of harmonious exceptionalism may be coming to an end.

It is still possible to shield the region from rising tensions elsewhere. That will require rethinking the role of states without polar territory, China among them, and creating an informal venue for security discussions that includes sanctions-hit Russia.

The eight Arctic states, including the U.S., Canada and Russia, must also take real action to tackle the region’s greatest threat: climate change.

A statement after this week’s Arctic Council meeting made multiple mentions of global warming, but tough national targets need to match that talk.

It won’t be an easy balance to strike. Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov warned against encroachment ahead of the Council meeting, which included government ministers from the region. “This is our land and our waters,” he said, before Moscow officially took the two-year rotating leadership of the Council. Framing the discussion as raw competition helps no one.

Fortunately, there’s a track record of substantive cooperation. A “race for resources” narrative underplays the real cost of extracting oil in the Arctic, despite oft-cited estimates of untapped mineral wealth.

New shipping routes such as the Northern Sea Route along the Russian Arctic coast are swifter and matter greatly for fossil fuels.

But practical difficulties like pricier fuel bills, the need for stronger hulls and crews trained to deal with unpredictable sea ice mean these routes aren’t about to displace other options.

Nevertheless, the Arctic is changing fast. Temperatures have warmed at three times the global average over the past 50 years, according to the Council. Shrinking sea ice will probably make matters worse as more heat is absorbed, rather than reflected back. Melting permafrost has already contributed to one of Russia’s worst fuel spills. Pathogens are a major concern.

The surge in human activity increases the risk for misunderstandings and accidents. There are more soldiers and military hardware as Russia builds up capacity, resuming operations at Soviet-era bases.

The U.S. reestablished the Navy’s Second Fleet, responsible for the northern Atlantic Ocean, and is adding icebreaker capacity. In February, Denmark said it would invest in drones and radar for Arctic surveillance.

It’s a very different place than it was in 1996, when the Council, the closest thing to a regional governing body, was set up.

So what needs to be done? First, recognize the change. No one denies the rights of Arctic states and we won’t see a wholesale revamp of the consensus-run structure.

But the Arctic doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Beijing’s inflated language on its Arctic policy has done it few favors, but Mike Pompeo, former U.S. Secretary of State, was wrong to say that China, and by extension other outsiders, were entitled to “exactly nothing.”

A proliferation of issue-specific arrangements show the need for a broader approach, albeit one with the Council at its core. It’s significant that Lavrov mentioned the need to “evaluate” and “improve” the observer nation set-up that allows some countries from outside the region to take part, even if it’s less clear what he has in mind. A stronger Council needs this.

Russia wasn’t keen to allow China observer status in 2013, but Beijing is a key investor in Russian Arctic ventures such as the Yamal LNG project.

As Elana Wilson Rowe at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs says, it’s unclear how Moscow can keep pursuing an independent policy in the region and keep Beijing at arm’s length as China becomes more integral to the Arctic’s development.

Where security is concerned, something has to be done to foster dialogue and ensure more frequent armed forces’ maneuvers don’t lead to confrontation. Military affairs are explicitly outside the Council’s mandate.

Yet sideline discussions bridging Western and Russian interests stopped after the annexation of Crimea in 2014, and activity has hardly cooled since. Informal meetings or expert discussions are overdue — in a set-up that explicitly doesn’t exonerate Russia’s actions elsewhere, as Mathieu Boulegue of Chatham House points out. A code of conduct is also essential.

Updated: 5-26-2021

Arctic Wildfires Are Back With Record Blazes In Western Siberia

Scientists are worried about the intensity of fires this early in the season.

This year’s fire season in the Arctic started with intense activity in western Siberia and Canada, and a below-average number of blazes in eastern Siberia.

The boreal fire season, which typically runs from May to October, started earlier this year with the first blazes recorded in April, according to a report by the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service.

Europe’s Earth observation agency registers the daily number of incidents and total estimated emissions using satellites.

“While it isn’t uncommon to see some wildfires during spring in high latitudes, it is difficult to predict what we may expect during the summer,” said Mark Parrington, a senior scientist and wildfire expert at Copernicus. The intense activity in western Siberia this early in the season is raising concerns among scientists.

The Arctic suffered the worst wildfire season on record for the second year in a row in 2020, with greenhouse gas emissions from blazes rising to the highest ever. Last year a prolonged heatwave hit the region, which is warming almost three times as fast as the rest of the world.

Thermometers in one town hit 38 degrees Celsius (100°F) in June and in July, while average temperatures were more than 5°C higher than the historical level.

Fire activity at the start of this season was more intense in regions that also posted higher-than-average temperatures, and lower where temperatures were cooler, according to Copernicus.

Wildfire emissions in the area around the city of Tyumen in western Siberia were the second-highest between April 1 and May 24, while pollution around Omsk was the third-highest ever. In Canada, larger-than-average wildfires burnt in Manitoba and Ontario.

Updated: 6-23-2021

Melting Arctic Ice Pits Russia Against U.S. And China For Control Of New Shipping Route

Warming in the Arctic is opening a shipping passage through Russia’s northern waters that could put the country at the center of new Asia-to-Europe trade routes.

Melting ice in the Arctic Ocean is bringing a centuries-old dream closer to reality for Russia: a shipping passage through its northern waters that could put it at the center of a new global trade shipping route.

After one of the warmest years on record, the Kremlin is near to realizing its controversial plans for a global shipping route in its high north—plans that have put Moscow at odds with the U.S. and could create friction with China, two countries that also have designs on the Arctic.

Warming in the Arctic is happening twice as fast as the rest of the planet. Last year, ice coverage reached some of the lowest levels ever recorded, and it is only expected to shrink further in 2021.

That is pushing Moscow to build infrastructure along the route, which can cut the distance of trips between Europe and Asia by a third compared with shipping through the politically fraught South China Sea or congested Malacca Straits currently used for cargo.

This year’s shipping season on the passage, which spans Russia’s expansive Arctic coast, started earlier than ever before, in February, when the liquid-natural-gas carrier Christophe de Margerie sailed from China to the northern Yamal peninsula.

The voyage followed an unprecedented nearly eight-month shipping season last year, giving Russia a taste of what the future could hold for the Northern Sea Route if traffic continues to grow.

A host of issues remain, such as icebreaker escort tariffs, transit costs and navigational unpredictability in the Arctic Circle. But an opening of the passage would put Russia at the center of a new global shipping route for energy supplies and cargo.

Moscow says it has the right to restrict passage and set prices for transit, and the route would also give it an important bargaining chip in its ties with China—one of the biggest beneficiaries of the 3,500-mile long passage.

“We have to see what the future holds, but it could very well look a lot like this,” said Alexander Alyoshkin, head of shipping for the transport division of SUEK, Russia’s biggest coal company.

Mr. Alyoshkin said the company had planned one test-run shipment to China across the route last year from its port at Murmansk, but boosted that number to six: “In June, when we saw over satellite that there is practically no ice on the Northern Sea Route, we started to plan for a few more runs, then a few more.”

“This year we’ll do more, as many as we can,” he said.

The U.S. says Russia doesn’t have the right to regulate traffic through the waters and environmentalists say heavy shipping on the waters could cause untold damage to the high north’s fragile ecosystem.

But with other shippers, including the Chinese, interested in exploring the route, Russia has pushed ahead with plans.

So far this year, traffic regulated by the Russian government is up 11% from the record 1,014 trips made last year. That is a drop in the ocean for global shipping that sees some 60,000 vessels every year.

Last year’s traffic was up more than 25% from 2019 with 33 million tons of cargo, oil and liquefied natural gas, and Moscow expects that number to grow. Russian President Vladimir Putin has said he wants cargo to double to 80 million tons by 2024.

During his summit with U.S. President Joe Biden in Geneva on June 16, Mr. Putin said the two leaders talked about the project where Moscow, which has more nuclear icebreakers than any other country in the world, has developed a new class of vessels.

“Navigation will become practically year-round due to climate change,” Mr. Putin said. The two leaders spoke at length about the Arctic, where the U.S. has accused Russia of militarizing the region by reopening old Soviet-era bases. Mr. Putin called the accusations groundless.

The scope of the project, expected to cost around $11.5 billion, highlights Moscow’s great ambitions in the Arctic.

The State Atomic Energy Corporation, or Rosatom, which manages a fleet of nuclear icebreakers that can cut through ice up to 10-feet thick, is drafting plans to station personnel along the route, boost port infrastructure along the shipping lane to allow for loading, and provide navigational and medical aid for ships.

It has already stationed one floating nuclear-power plant on the route, to help with onshore construction.

“The Arctic region is quite a unique one so we must think about infrastructure in a complex way,” said Polina Lion, chief sustainability officer at Rosatom.

Russia still has a way to go in upgrading its network of dilapidated, Soviet-era ports along the route to provide for loading and refueling.

A British mining company, Kaz Minerals, has agreed to build a port on the eastern tip of the route to export gold and copper from a newly acquired asset, said Alexey Chekunkov, minister of development for the Arctic and Far East. The port will be open to other ships passing, he said.

But shippers remain cautious.

China is watching progress but hasn’t yet made any commitments to invest in the passage or give cargo guarantees. China’s state shipper, COSCO, carries out around nine test runs every year, but the amount of Chinese shipping could rise, said Ms. Lion, as some companies are already in talks to guarantee some annual shipping volumes.

Beijing is eyeing the route in case weather makes navigation more predictable or if other trade routes in the South China Sea are disrupted by tensions with the U.S. or its allies.

Moreover, “There is a certain interest in the NSR from the Chinese Navy for strategic mobility to move troops between Pacific to Atlantic theaters,” said Vasily Kashin, an expert on Russia-China relations at the Moscow-based Higher School of Economics.

“And they do have this interest in establishing their presence on the Atlantic.”

Russia has already boosted its military presence in the Arctic and along the Northern Sea Route, but the U.S. says Moscow’s legal jurisdiction doesn’t extend to the waters where the Kremlin is working to develop the passage.

“Unlawful regulation of maritime traffic along the Northern Sea Route undermines global interests, promotes instability, and ultimately degrades security in the region,” a U.S. naval strategy paper on the Arctic said earlier this year.

Russian authorities are still determining the transparent tariff duties, both for transit and for icebreaker escorts along the passage, that are key to attracting both investment and cargo.

Traffic on the route, however, is already guaranteed by Russia’s increasing production of Arctic oil and gas. The majority of vessels carry LNG from the port of Sabetta, where gas from Russian energy giant Novatek’s Yamal project is loaded for consumers in Europe or Asia. Crude from Rosneft’s planned Vostok oil field project will also be sent along the route when it comes onstream.

But Russia has yet to convince Europe’s biggest shippers about the Northern Sea Route.

The Danish integrated shipping company, Maersk, which made a test run of the passage in 2018, said it isn’t pursuing the route as a feasible alternative to current shipping passages, citing possible environmental damage to the fragile Arctic ecosystem.

Hapag-Lloyd AG , the German international shipping and container transportation company, has also said it isn’t interested.

Still, Russia says it will be able to bring Western shippers on board if the route proves predictable, and Mr. Chekunkov says the use of nuclear-powered icebreakers to help with escorts won’t add to carbon emissions in the high north.

“The dream, of course, is the dream of a regular container line. We are not there yet,” said Mr. Chekunkov. “But I’m a believer.”

Updated: 10-08-2020

Russia’s Siberian Waters See Record Ship Traffic As Ice Melt Accelerates

The Northern Sea Route is becoming a highway to move Russia’s oil and natural gas exports while some global carriers shy away.

The Arctic has gone through its warmest summer on record, and with the ice melting, more ships than ever are sailing along Russia’s Siberian coast, underscoring its role as a growing energy transport corridor and potential as a new ocean trade route.

The Northern Sea Route, which runs from Alaska to the Baltic Sea, counted 71 vessels and 935 sailings across the waterway from January to June this year, according to the NSR information office. That was up by double digits from the same period a year ago and a big increase from the 47 vessels and 572 voyages in the same period of 2018.

The mostly frozen seaway is used in warmer seasons to move some of Russia’s energy exports to overseas markets. Container ships and general cargo vessel operators also have used the route to move goods between Asia and Europe as it cuts an average 10 days of sailing time compared with the standard route through the Suez Canal.

Freight transport on the NSR is at its highest from July to November. Some sailings also take place in the rest of the year, and the Russian government expects largely ice-free year-round trips starting in 2024.

“There are many more ships because the ice is thin and you can sail without the help of icebreakers,” said Arne O. Holm, editor in chief of the Norway-based High North News, which monitors the NSR. “The NSR needs a lot of investment to attract bigger cargo vessels, but activity is picking up, and if the ice keeps melting it will be another option to move cargo from northern China to Europe.”

The National Snow and Ice Data Center, a private science research group supported by U.S. government agencies, said in September that this summer was the warmest on record in the Arctic, with the extent of sea ice across the entire Arctic shrinking to 3.74 million square kilometers, or 1.44 million square miles. That’s not much more than half the average ice cover of 6.7 million square kilometers measured from 1979 to 2000.

“There was no ice at all across the coastline in September, no need for icebreakers or ice-hardened vessels,” said Nikos Papalios, a mechanic on a crude tanker that sails the NSR.

“It stayed above freezing for 10 days, from the port of Sabetta to the Bering Strait, and it was pleasant to sit on the deck. It felt out of place,” Mr. Papalios said.

Most vessels operating in the NSR are natural gas carriers and oil tankers carrying exports to European and Asian customers from Novatek’s Yamal liquefied natural gas project and Gazprom’s Novy Port crude oil project at the Yamal Peninsula along Russia’s northern coast. These heavily reinforced ships are built to move through ice-filled waters and can cost more than $200 million each, more than twice the price of similar-size ocean vessels.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has said the NSR will be key to develop the Arctic and become a global transport route.

The Russian government expects cargo volumes across the waterway will reach 32 million metric tons this year, up 78% from 18 million metric tons in 2018. Novatek expects to ship about 52 million metric tons of LNG a year by 2030.

Brokers said container ships and bulk carriers operated by Cosco Shipping Holdings Co. Ltd., Nordic Bulk Carriers A/S and Norway-headquartered Golden Ocean Group are active in the waterway. Denmark’s A.P. Moller-Maersk, the world’s biggest container ship operator, sent a 3,600-container ship from Vladivostok in the Russian Far East to St. Petersburg in late 2018 laden with frozen fish to explore the NSR’s potential.

But there are limits to the waterway’s potential role in global trade.

Cargo between Asia and Europe is handled by massive ships that can carry more than 20,000 containers each. Parts of the NSR are too shallow for anything larger than a 5,000-container vessel and there are no transshipment ports.

Early hopes of big Chinese infrastructure investments also are fading. State-owned transport giants like Cosco and China Merchants Holdings Ltd. are pouring billions into linking ports with roads and rail to connect Asia and Europe under the Belt and Road Initiative rather than step up investments in the Northern Sea Route.

French container ship major CMA CGM SA and German counterpart Hapag-Lloyd AG have said they won’t send ships on the NSR, citing concerns over the environmental protections.

“The NSR is growing and it’s good if you want to move boxes quickly at a single destination port. But it’s not going to replace the Suez Canal,” a senior Cosco official said.

Updated: 1-13-2022

Danish Spy Agency Frets Over Arctic Operations By China And Russia

Danish intelligence service warned China and Russia are looking to destabilize parts of the Kingdom of Denmark, including Greenland, as these nations’ geopolitical ambitions in the Arctic region are growing.

Espionage and influence operations by Chinese and Russian spy services, including via cyber attacks, pose a threat against authorities, companies and research bodies in Denmark and the semi-autonomous Faroe Islands and Greenland, Danish security and intelligence service PET said on Thursday in its first publication assessing such risks.

“The kingdom is particularly vulnerable in that regard as Chinese or Russian intelligence services can exploit controversial topics to try to create tensions in or between the three parts of the kingdom or complicate relations with allies, particularly the U.S.,” the agency said.

Greenland and the Faroe Islands are strategically located on the pathway between the Arctic and the North Atlantic. Denmark’s primary security ally, the U.S., has its northernmost base on Greenland and the island’s natural resources have further boosted the interest from Russia and China.

Tensions between Denmark and Greenland, which has a strong independence movement, have grown recently.

The island’s new government, appointed after last year’s general election, has urged to demilitarize Greenland and rejected a 1.5 billion kroner ($230 million) deal struck by the Danish parliament to boost defense spending in the Arctic.

The previous government wanted to attract foreign companies, such as Chinese-backed Greenland Minerals, which were looking to tap the island’s rare-earth metals.

Updated: 6-15-2022

A Warming Arctic Emerges As A Route For Subsea Cables

So far, work is only possible in the summer months. But companies see the remote, fragile north as a future hub of crisscrossing digital infrastructure links.

Northern countries are racing to build undersea communications cables through the waters of the Arctic, as shrinking ice coverage opens the region to new business opportunities and heightens geopolitical rivalries between Russia and the West.

Planned cables by a group of Alaskan, Finnish and Japanese companies as well as by the Russian government are competing to create better digital infrastructure in a fragile yet increasingly vital area for defense and scientific research.

Subsea cables, bundles of fiber-optic lines, carry about 95% of intercontinental voice and data traffic. There are currently over 400 such cables, with signal delay roughly proportional to the length of each cable.

Because the geographical distance between continents is less at the Arctic than further south, a cable through the region would promise faster communications, experts say. The possibility of a route has become more feasible as accelerated warming has opened the area to development.

A bank in London transmitting data to Tokyo could do so 30% to 40% faster via an Arctic route than through existing routes which go from London and head East crossing Egypt, said Tim Stronge, analyst at subsea cable analysis firm TeleGeography.

Industries like defense, petroleum, gas and fishing as well as scientists doing climate research in the Arctic would all benefit from faster communications, he said, adding that communities living there would also have better internet access.

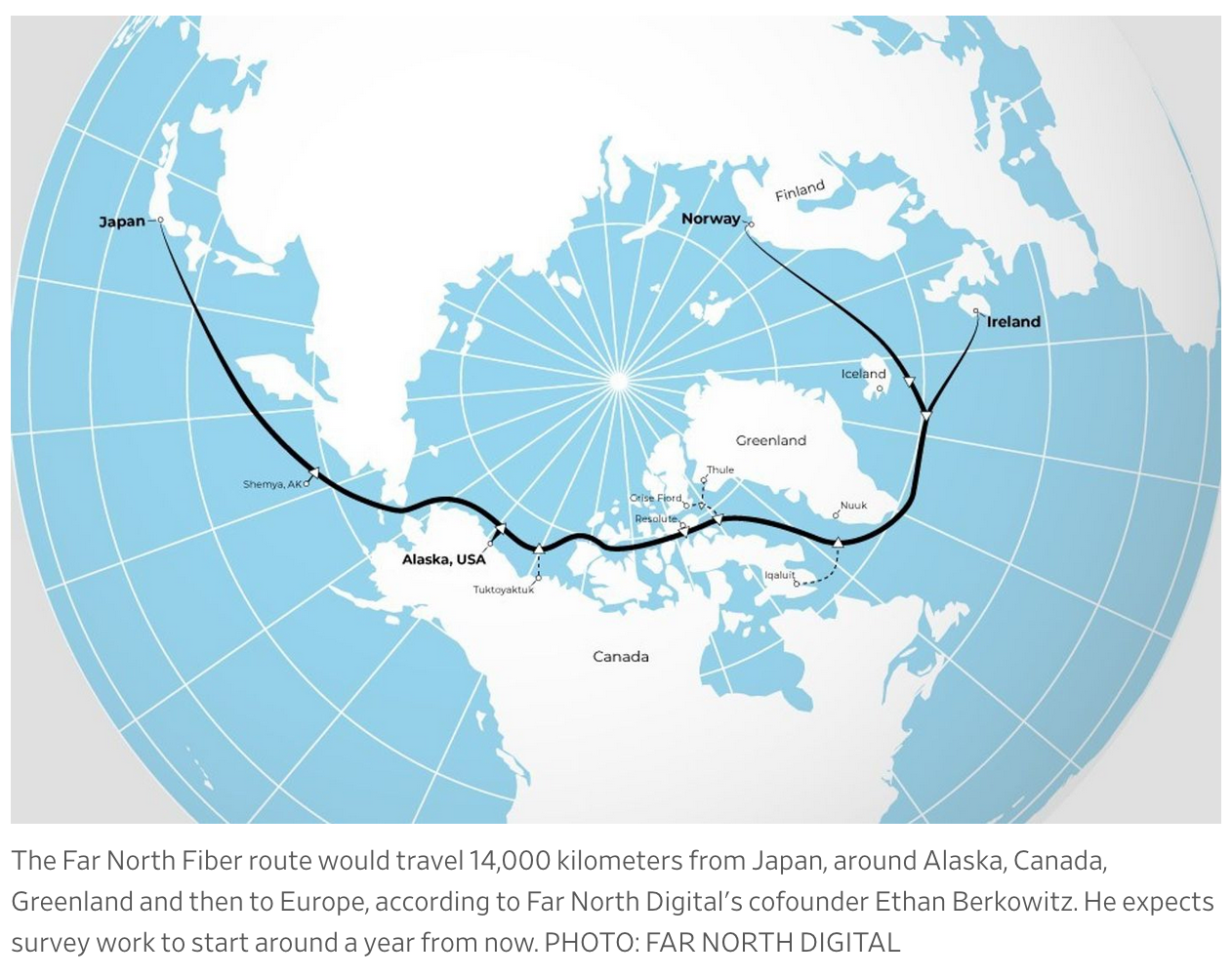

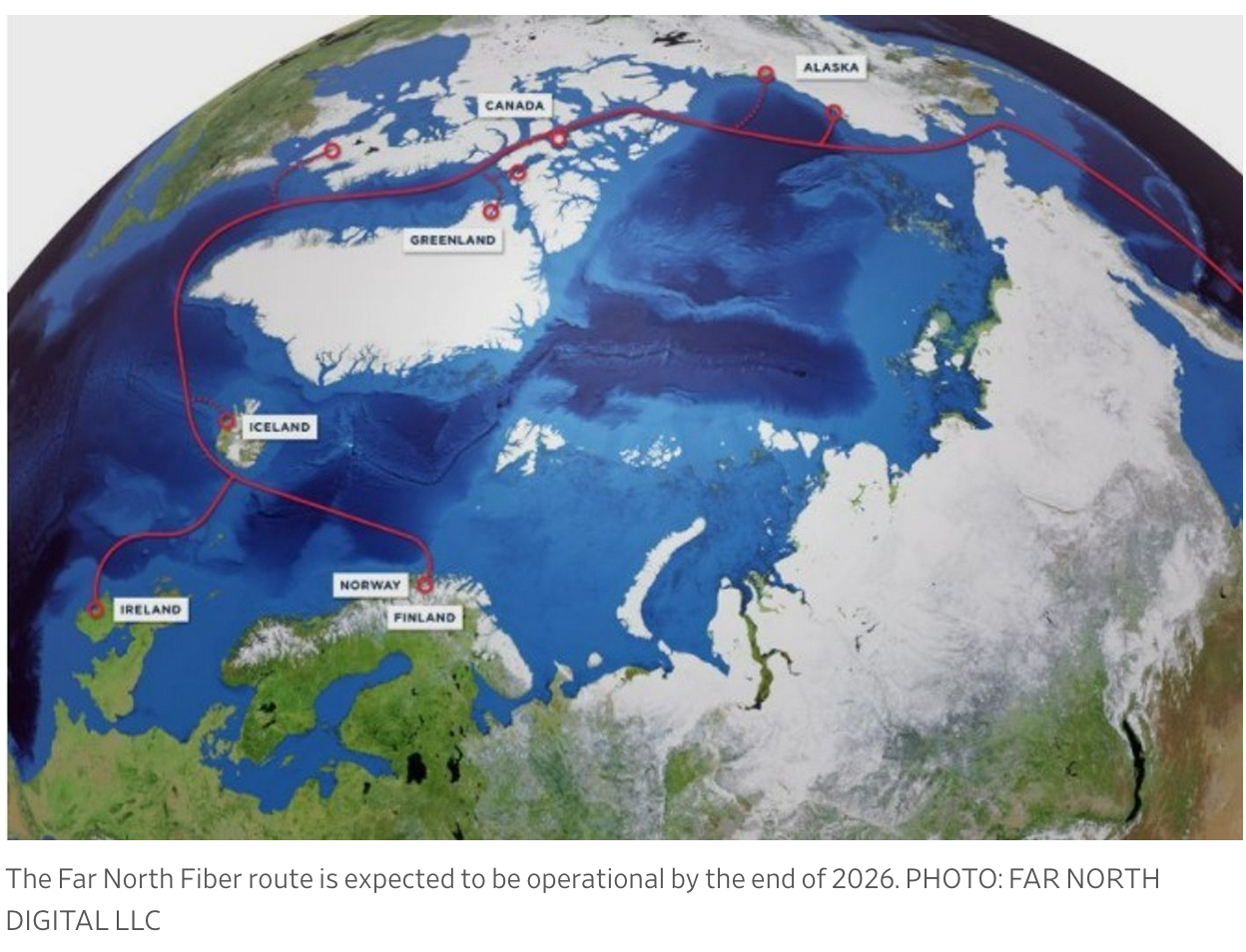

Alaskan company Far North Digital LLC, which is partnering with Finland’s Cinia Ltd. and Japan’s Arteria Networks Corp., plans to build a cable through the Northwest passage, the route that curls around northern Alaska and scattered Canadian islands and loops under Greenland, linking the Atlantic with the Pacific.

The company expects to deploy ships to begin survey work in the summer of 2023.

The proposed Far North Fiber route, which aims to be operational by the end of 2026, would travel approximately 14,000 kilometers, or 8,699 miles, east from Japan, through the Northwest passage and then on to Europe, according to Ethan Berkowitz, a co-founder of Far North Digital. The project has been in the works for several years, he said.

Mr. Berkowitz said the project has obtained an engineering, procurement and construction contract from Alcatel Submarine Networks and begun the permitting process “at various locations around the route.” The companies are in advanced talks to finance the project, he said, which is expected to cost approximately 1 billion euros, or $1.04 billion.

Far North Digital is hardly the only company staking a claim on the Northern frontier. A Russian state company, Morsvyazsputnik, made headlines in August when it said it started construction on a 12,650-kilometer cable around its northern and eastern coast.

The Russian government has been quiet about it since then. TeleGeography’s Mr. Stronge commented, “It’s our understanding from industry sources that certain segments are active.”

As the Arctic’s melting opens the region to economic opportunity, the area has become increasingly politicized and geo-economically competitive, said Tim Reilly, a research fellow at the University of Cambridge’s Scott Polar Research Institute. Russia’s war in Ukraine further heightened those tensions, he said.

“The strategic issue is the quiet, vicious fight for governance of the region using technological means instead of outright conflict,” Dr. Reilly said.

Nima Khorrami, a Stockholm-based research associate at The Arctic Institute, commented, “Having control over the passage of data, that, in and of itself, is a source of power.”

The cables represent an intelligence, strategic and economic advantage, said Dr. Reilly. They could help countries manage and intercept big data, better control space-based missile guidance systems and satellites that deliver content and services as a means of global influence, he said.

“With the likely admission of Finland into NATO, as well as Sweden, it is going to enable communications that we wouldn’t otherwise have,” said Mr. Berkowitz. “This route is more secure and less dependent on the good graces of non-NATO members.”

But building a subsea cable in frigid Arctic waters is no small feat, according to Matt Peterson, chief technology officer of Quintillion Subsea Operations, LLC, which operates a 1,180-mile subsea cable around the coast of Alaska.

The first difficulty is that cable can only be built or worked on during the summer months when ice sheets don’t cover the water’s surface, he said.

Another risk is when ice plates shift, especially in the shallower waters surrounding Alaska, they risk severing the fiber, he added. Quintillion contracted Alcatel Submarine Networks to create a sea plow that was able to bury the cable deep underneath the seabed in order to avoid that problem, he said.

Like Far North Digital, Quintillion is also planning to lay new cable. It expects to complete construction on a section connecting Alaska to Asia in about three years, and after that to begin on the Canada to Europe leg.

Arctic ice does have its advantages, Mr. Berkowitz said. Many subsea cable problems come from boats and anchors dragging and ripping up the bottom. “You don’t have those problems when you have an ice cover,” he said.

Mr. Berkowitz said he had been thinking about an Arctic cable for about a decade, before the region’s melting made the idea more realistic. “This is an essential piece of infrastructure,” he said.

“To me, it’s a question of: You look at a map and you see a need,” he said.

Updated: 5-4-2023

Russia’s Next Standoff With The West Lies In The Resource-Rich Arctic

The high Arctic is an internationally neutral zone that has long kept away from geopolitics. But climate change has precipitated an unusual level of activity in the remote polar region as colliding strategic interests and melting ice stand to reshape it profoundly.

Stewardship of the Arctic is suddenly in question as a result of the isolation of Russia, the largest Arctic state, over its war on Ukraine. The Arctic Council — the main body for cooperation among the eight nations that share guardianship — is in limbo. Its meetings have been suspended since last year, and no one is quite sure what will happen after May 11, when Russia is due to hand over the rotating chair to Norway.

Russia remains a member of the council, and so will “in principle” be involved in any decisions or activities, said Thomas Winkler, Arctic Ambassador for the Kingdom of Denmark. But how that would actually happen in the current political climate “is still something that’s being considered,” he said. “I simply don’t have an answer.”

What’s clear is that the low-conflict status quo is in jeopardy, putting at risk the scientific cooperation that’s flourished since the end of the Cold War. And things are becoming fraught at a time when both the warming of the Arctic and the race for its resources — possibly millions of barrels of oil and rich mineral deposits — are picking up.

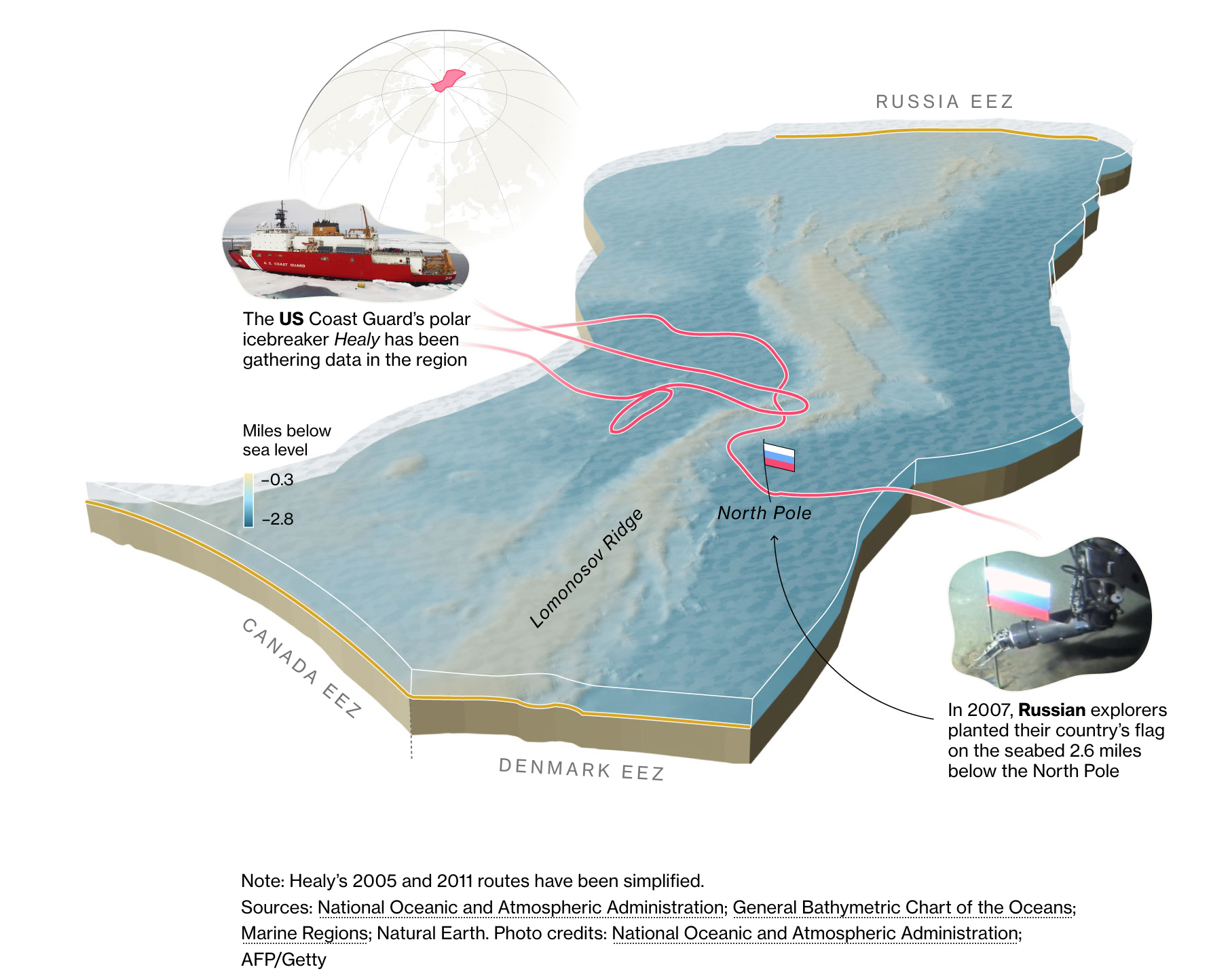

Who controls the top of the planet depends on where you draw the lines. Although no one “owns” the North Pole, countries with land ringing the Central Arctic Ocean already have rights extending some way beyond their coastlines, under international law.

Now three of them — Russia, Canada and Denmark, on behalf of its autonomous dependent territory Greenland — are redrawing maps and arguing for more expansive sovereign rights to what’s beneath the ocean: a huge swath of the Arctic seabed, stretching across the North Pole.

How the boundaries end up being delineated, to use the diplomatic terminology, depends on how far the continental shelf extends beyond each country’s coast. All three countries claim their continental shelves stretch into an underwater mountain range called the Lomonosov Ridge. (A fourth country, Norway, made a more modest case for redrawn boundaries some years ago.)

Countries will still be able to travel freely through what will remain international waters. But the natural resources below those waters could be vast and are up for grabs. The unfolding contest could have major repercussions for who controls key resources — and for the climate.

Nationalism Provides Another Incentive: The Arctic is a strategic priority in particular for Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Changes in Russia’s latest Arctic strategy, as outlined in a foreign policy document signed by Putin on March 31, remove references to “constructive international cooperation.”

The policy document pledges to push back against unfriendly states hoping to militarize the region and to establish closer cooperative ties with non-Arctic states “pursuing a constructive policy towards Russia,” a possible reference to China, which also has aspirations in the polar region.

The US, another Arctic power, remains committed to the region and to the council, a State Department spokesperson said in a statement. But Russia’s actions in conducting a war against Ukraine “inhibit the cooperation, coordination and interaction that characterize the work of the Arctic Council,” the person said.

Finland applied to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in response to Putin’s aggression and was admitted on April 4. Assuming fellow Nordic nation Sweden eventually accedes too, Russia will then be the only Arctic power that’s not a member of the alliance.

“It’s global politics in a microcosm,” Andreas Østhagen, senior researcher at Norway’s Fridtjof Nansen Institute and an expert on Arctic security and geopolitics, said of the region.

It’s also, he says, about countries hedging their bets.

“Fifty years from now, who knows whether we are still desperately trying to extract the last remaining oil and gas resources, or we’re in desperate need of more rare earth minerals — and these might be located in this part of the Arctic.”

That’s where the overlapping claims to rights over the seabed come in.

Russia, Denmark and Canada each claim that the Lomonosov Ridge, which traverses the pole, is an extension of the continental shelf continuing from its coastline into the Central Arctic Ocean.

Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, this would confer exclusive sovereign rights to natural resources on and below the polar sea floor, beyond the exclusive economic zones that stretch up to 200 nautical miles (230 miles) off their coasts.

As well as those countries, Norway has made a submission — backed in 2009 by the independent body tasked with reviewing the science, known as the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) — but it stops well short of the North Pole.

The US, meanwhile, hasn’t ratified the UN Convention but may be preparing its own claim anyway.

“The US has been gathering data for decades in the Arctic and we keep hearing how a claim may be coming out,” said Rebecca Pincus, director of the Polar Institute at the Wilson Center, a Washington think tank. Ultimately, the US will jump into the fray, she believes, if only to be able to control how at least some of the resources are used.

Gaining access to potentially lucrative resources is one of the main reasons countries have been making submissions. Still largely unexplored, the Arctic seabed is nonetheless thought to contain large stores of fossil fuels, metals and critical minerals that will become easier to access as global warming melts the sea ice above.

The most recent circum-Arctic assessment by the US Geological Survey was conducted in 2008. It estimated that about 90 billion barrels of undiscovered oil and 1,670 trillion cubic feet of gas lie inside the Arctic Circle, along with critical metals and minerals needed for electrification.

Still, most of what is known about the latter is confined to land studies. The offshore metal deposits of the Arctic’s continental shelves are still largely unexplored, though the geology suggests they could be significant.

“I think there was no doubt in the minds of any of these coastal states that they would file a claim with the continental shelf, despite high costs and despite the fact that the economic benefits are really unknown,” said Walter Roest, who served on the CLCS from 2012 to 2017.

“They have all claimed pretty much the maximum they can claim, with an objective to be strong when they have to negotiate.”

Exactly when it will become economically feasible to mine the polar seabed is an open question, but the national bragging rights are not. “There is definitely a political and a symbolic element to Arctic continental shelf claims,” says Philip Steinberg, director of the International Boundaries Research Unit at the UK’s Durham University.

“They speak to a national vision, an idea that a nation’s future is in the North.”

Climate change will make it easier to access these areas, for exploration and extraction, as well as to ship out any resources. The Arctic is warming up to four times as fast as the rest of the globe, and that pace is accelerating.

In its 2022 State of the Cryosphere report, the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative (ICCI) concluded it is now inevitable that there will be ice-free summers in the Arctic before 2050.

That’s expected to amplify a host of devastating climate-related consequences. While ice shields the Earth by reflecting the sun’s heat, open water does the opposite, accelerating warming. Changes in the temperature gap between the faster-warming Arctic and lower latitudes may make global weather patterns even more extreme, while ice loss and changes in ocean circulation disrupt the habitats of marine animals.

Changes on land create their own feedback loops in the Arctic. Thawing permafrost releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, hastening warming, which accelerates thawing. Melting glaciers cause sea levels to rise faster and higher.

Economic development in the Arctic poses risks to Indigenous populations, to biodiversity and — especially in the case of fossil fuel development — to a climate already changing faster than humans can adapt.

Current plans for extraction are mixed. Russia, which has been producing offshore oil in the Arctic for a decade, has pledged in its Arctic Strategy to increase land and sea production out to 2035 — though its most ambitious plans are on hold due to sanctions.

While the US recently approved the $8 billion Willow oil project on the Alaskan mainland, it’s restricting offshore oil leasing in Arctic waters. Norway has offshore fields above the Arctic Circle but its attempt to license new oil exploration in the Barents Sea faces legal challenges.

In 2021, Greenland scrapped plans for future oil exploration, saying the climate ramifications were too high. A Canadian ban on offshore development was recently extended. To date, these countries’ activity has been in the lower portion of the Arctic Circle only.

Fossil fuel extraction and deep-sea mining in a part of the world that’s critical to the planet’s climate defenses are highly controversial. But winning sovereign rights to offshore resources could be as much about protection as exploitation.

“If you have the right to the seabed you also have the right to say it’s not allowed to develop these resources,” said Marc Jacobsen, an assistant professor at the Royal Danish Defence College. “It’s not only about economic logic. It could also be about environmental logic.”

All parties are well aware of the region’s strategic military importance as melting opens up new routes for ships and submarines over the top of the planet. That has only gained in significance as a result of Moscow’s aggression.

In February, the CLCS determined that a significant portion of Russia’s submission is supported by the geology, though other parts require more mapping and research. Russia responded the same month with clarification.

If the CLCS agrees with it, Russia’s continental shelf in the Central Arctic Ocean would seem to consist of 516,400 square nautical miles (684,000 square miles) — an area larger than Libya, according to analysis by Durham’s International Boundaries Research Unit.

This means Russia is the only one of the three countries with overlapping claims to have achieved at least partial victory, said Jacobsen. “Russia has the narrative in their favor right now,” he said.

But it doesn’t mean Denmark and Canada are out of luck. Ultimately the CLCS may determine that the Lomonosov Ridge is part of a shared continental shelf, meaning everyone will have to share. Countries may end up needing to negotiate boundaries among themselves, or through a third-party tribunal.

Untangling the scientific submissions of the three countries will take years, or even decades. But while the process grinds along, the ice is melting — fast.

Conditions that allow the exploitation of Arctic resources “also amplify the risks and societal disruptions,” the ICCI said in its scientific report. “Such profound, adverse impacts almost certainly will eclipse any temporary economic benefits brought by an ice-free summer Arctic.”

Back in 2007, when Putin was nearing the completion of his second term as president, Russia planted a flag in the seabed floor at the North Pole as a means of staking a symbolic, if legally unsupported, claim to the top of the planet.

Sixteen years later, Putin is still in power and flexing his imperial muscle. For now, the North Pole — one of the most pristine places on Earth — belongs to everyone and no one. Once all the geological evidence is sifted through, there will be no going back for the Arctic.

Updated: 6-15-2023

Russia’s Arctic Shipping Dream Stumbles On Small Aging Fleet

* Rosatom Says Enough Arctic Ships Can’t Be Built By 2030

* Arctic Waters Are The Shortest Route From Europe To Asia

Russia will struggle to meet its strategic goal of more than quadrupling Arctic sea shipments by the end of the decade as the nation cannot increase and upgrade its small, aging ice fleet fast enough, according to the Northern Sea Route operator Rosatom.

The Arctic route, stretching more than 3,000 nautical miles (5,556 kilometers) between the Barents Sea and the Bering Strait, is the shortest passage between Europe and Asia.

Global warming has made the icebound waters increasingly more navigable, creating opportunities for Russian commodity exporters that are focusing on Asian markets amid the Kremlin’s standoff with the West over its invasion of Ukraine.

Russia aims to send at least 150 million tons of crude oil, liquefied natural gas, coal and other cargoes via its Northern Sea Route every year from 2030, a more than fourfold jump on the volumes shipped in 2022, according to the Northern Sea Route development plan approved by the nation’s government.

Yet this goal requires construction of a whole new commercial Arctic fleet, according to Vyacheslav Ruksha, head of the Northern Sea Route Directorate at state nuclear corporation Rosatom.

In the next seven years, the number of Russia’s Arctic cargo vessels — from oil and LNG tankers to bulkers carriers and container ships — will need to grow to 160 from just 30 now, according to the presentation Ruksha made at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum on Thursday. Currently, only 33 more vessels are under construction.

“I am afraid, we are underestimating technological issues here,” the Rosatom official said. “We cannot bring in such capacities within this timeframe.”

Russia’s fleet of ice-class supply vessels, used for safe navigation in Arctic waters, is aging, Ruksha added. Over 40% of the fleet is more than 30 years old now, and that proportion will grow to 75% by 2030, according to his presentation.

“To increase the navigation timeframe and reduce the shortage of supply vessels, a new universal supply vessel” of a higher ice-class needs to be designed, according to the presentation.

Russia has been successfully raising shipments via the Arctic Sea route in the past several years, bringing them to over 34 million tons in 2022 compared to just 7.5 million tons in 2016.

The additional cargoes mainly came from the Novatek PJSC-led Yamal LNG plant, with the producer of super-chilled fuel relying on South Korea to supply new tankers.

Higher cargo volumes would become available with the launch of several major hydrocarbon projects, including the Arctic LNG 2 plant led by Novatek and Rosneft PJSC’s Vostok Oil developed.

Relations between Russia and many of its former trade partners have been strained by the invasion in Ukraine. Korean shipyards will supply only five out of 15 contracted LNG carriers to Russia, Viktor Evtukhov, Russia’s Deputy Industry and Trade Minister, said at the forum.

The nation’s commodity producers will rely on domestic shipyards to grow their commercial Arctic fleet and are holding talks with Chinese shipbuilders to replace Korean partners, Evtukhov said.

Updated: 7-18-2023

Russia Sends Oil Through The Arctic Again To Speed Up Delivery To China

* Sailing Through Arctic Sea Cuts Voyage Times By 30% To China

* Environmental Concern About Using Arctic For Merchant Shipping

Russia is sending a rare cargo of crude oil through the Arctic Sea to China, a move that will fan environmental concerns even if it means cheaper delivery costs for the nation’s petroleum.

The Aframax-class tanker Primorsky Prospect is heading north up the coast of Norway, showing its destination as Rizhao in China, where it’s due to arrive on Aug. 12. It is one of a handful of tracked cargoes on the route.

European Union sanctions have forced Russia to seek new markets for its crude. Those are mostly in China and India, adding thousands of miles to delivery times and making freight more costly.

While that might make the shorter Arctic route appealing, there has long been opposition to using the sea for merchant shipping.

Organizations including the UN’s intergovernmental body for climate change have said doing so could have negative consequences for the region, including higher emissions and threats to marine ecosystems.

Using the so-called Northern Sea Route, or NSR, through the Arctic waters off Russia’s northern coast, could shave as much as two weeks, or about 30%, off the voyage compared with the southern route through the Mediterranean and the Suez Canal.

The vessel, built in 2010 and owned by Russia’s Sovcomflot, loaded about 730,000 barrels of Urals crude at the Baltic port of Ust-Luga on July 11-12, according to ship tracking data monitored by Bloomberg.

Eastbound navigation along Russia’s Northern Sea Route halted for winter on Nov. 30.

A previous cargo was sent last year, shortly before the route became impassable. At least two tankers went through in 2019.

Rosatom, which operates the NSR, and Russia’s oil producers are studying a possible redirection of crude shipments from Baltic ports through the Arctic.

Meanwhile Novatek, which operates LNG projects on Russia’s Arctic coast, plans to begin year-round eastbound navigation via the Northern Sea Route at the start of 2024.

Updated: 8-18-2023

The Panama Canal Has Become A Traffic Jam Of The Seas

More than 200 vessels are stuck on either side of the waterway as a serious drought cuts crossings.

A flotilla of ships are stuck on both sides of the Panama Canal, waiting for weeks to cross after the waterway’s authorities cut transits to conserve water amid a serious drought.

Vessel-tracking data show more than 200 ships currently waiting to transit, a figure that has been climbing since the canal capped daily transits to 32 last month from an average 36 under normal conditions.

The waterway’s entrances on the Pacific and Atlantic oceans are dotted with ships that are backed up for more than 20 days. Most are bulk cargo or gas carriers that are typically booked on short notice. Some shipowners are rerouting traffic to avoid the backlog.

“The delays are changing by the day. Once you make a decision to go there is no point to return or deviate, so you can get stuck,” said Tim Hansen, chief commercial officer at Dorian LPG, which operates more than 20 large gas carriers.

The canal, which uses three times as much water as New York City each day, relies on rainfall to replenish it. If there isn’t enough rain, ship transits are cut and those that cross pay hefty premiums that boost transport costs for cargo owners such as American oil and gas exporters and Asian importers.

The canal’s administrator, Ricaurte Vásquez Morales, said in late July that the restrictions could stay in place for the rest of the year.

He said the drought is expected to erase around $200 million in revenue from the canal next year if low rainfall levels persist into the fall and winter.

He said extreme rain or drought conditions are more frequent occurrences than in the canal’s earlier years of operation. That issue presents a challenge for the Panama Canal Authority, which also supplies water to about 2.5 million people, or about half the country’s population.

“The Canal communicates with its customers so that the information allows them to make the best decisions even if it means that they may choose another route temporarily,” Vásquez Morales said. “Demand remains high which proves the Panama Canal remains competitive in most segments, even with measures to save water.”

The canal has hired the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the original canal builder, and has earmarked $2 billion over the next 10 years to divert up to four rivers into the waterway in addition to the three that already feed it.

The drought hasn’t caused wide disruptions for containerships, the canal’s biggest users in terms of transits. Most boxships are given preferential status because they run on fixed schedules and book crossings up to a year in advance. But some are caught in the maze and have to pay multiple times the average tolls.

“We had two ships that couldn’t book and it was quite expensive,” said Lars Oestergaard Nielsen, A.P. Moller-Maersk’s head of customer delivery in the Americas. “We went to an auction and paid $900,000 on top of $400,000 normal toll fee for each ship to cross.”

Ships normally cross the canal at an average 50 feet of draft, which has been reduced to 44 feet. To match the lower water depth, big boxships have to cross with fewer containers aboard. Smaller ships are added to move the remainder of the cargo.

Vessels that aren’t on fixed routes like bulk and gas carriers that are booked to move cargo in short notice face the longest delays.

Oslo-based Avance Gas, which operates 17 vessels, has rerouted about three-quarters of its ships moving U.S. exports of butane and propane. Now vessels carrying those products to customers in Japan, South Korea and China sail through the Suez Canal or around the Cape of Good Hope.

“Waiting time is one thing, but it’s also the uncertainty,” said Øystein Kalleklev, the company’s chief executive. “It’s risky to fix a ship with no firm itinerary because you can lose the contract if the wait is too long.”

Bulk vessels that move commodities such as coal and iron ore are also stuck by the dozens. These ships are mostly owned by medium-size or smaller operators that get no priority at the port.

Coal-laden ships out of the Atlantic are deviating from their preferred Panama Canal route due to increasing transit times, shipping analysts at BRS Shipbrokers said in a report last week.

Tankers with crude or petroleum products stuck on the Pacific side reached a two-year high at the end of July, according to shipping-data provider Vortexa.

“The Panama Canal is a big mess these days,” said Kalleklev. “Twenty days in a queue is unprecedented at this time of the year.”

Updated: 9-17-2023

To Build Ships That Break Ice, U.S. Must Relearn To Cut Steel

U.S. has only two polar icebreakers to Russia’s three dozen; China, Russia growing more active around receding ice.

PASCAGOULA, Miss.—A $13.3 billion program to safeguard American interests in the Arctic has run aground on an old industrial challenge: cutting and shaping thick, hardened steel.

U.S. officials are racing to procure new polar icebreakers because one of only two that the Coast Guard now sails has reached the end of its life, and the one assigned to the Arctic is out of service for maintenance every winter.

Delivery of the first new icebreaker has slipped to 2028 from 2024 as designers, engineers and welders grapple with something the U.S. hasn’t done in decades: reliably shape hardened steel that is more than an inch thick into a curved, reinforced ship’s hull.

The Coast Guard hasn’t launched a new heavy icebreaker since 1976. Out of practice, U.S. shipbuilders have had to relearn how to design and build the specialized vessel, say officials in the industry and the government.

The technical challenge of working with special steel has been compounded by an industrywide labor shortage and the coronavirus pandemic.

Receding sea ice in the Arctic due to climate change is, paradoxically, increasing the need for icebreakers and other vessels that can handle rough conditions in and around the Arctic Ocean, officials say.

Russian vessel traffic in the northern reaches of the globe is rising, including liquefied natural gas bound for China—between Asia and Europe.

For the Coast Guard, a branch of the armed services that is part of the Department of Homeland Security, the goal is to launch a new class of armed icebreakers—called polar security cutters—that can tackle problems ranging from environmental disasters to strategic confrontation in icy waters.

The total estimated cost of the polar security cutter program increased to $13.3 billion in 2021 from $9.8 billion in 2018, according to the Government Accountability Office.

The science-focused Healy medium icebreaker, which is normally assigned to the Arctic, has to undergo repairs and refitting annually in California or Washington. The other, the heavy icebreaker Polar Star, is nearing the end of its useful service life.

By comparison, Russia has three dozen national icebreakers suitable for the Arctic, according to the U.S. Coast Guard, and China has four, including two icebreaking research ships that regularly appear at high latitudes.

U.S. officials suspect those have strategic purposes. Beijing says science is driving its Arctic ambitions.

Russia and China have also been increasing cooperation in the Bering Sea and the Arctic.

One Coast Guard cutter intercepted a joint Russian-Chinese squadron of warships last year in the exclusive economic zone near Alaska’s Aleutian Islands. Last month, a larger Russian-Chinese group was tracked by U.S. warships and surveillance craft.

“We need to increase the presence of our Navy and Coast Guard in the Arctic and improve our deterrence in the Pacific,” said Sen. Roger Wicker of Mississippi, the top Republican on the Senate Armed Services Committee.

“Without a monumental investment in our shipyards and defense industrial base, we will not be able to secure American dominance in the maritime domain.”

Besides a powerful propulsion system, the key feature of a heavy polar icebreaker is its thick hull, which needs extra strength, framing to reinforce its shape and smooth curves for maneuverability in sea ice, Coast Guard officers say.

‘It Takes A Beating’

The machinery and skills to build the hulls of most oceangoing vessels aren’t sufficient for the specialized icebreakers. The hull plates need a bespoke alloy and specialized heat-treatment, with a process to form and weld massive curved plates.

“Higher-strength steels require very skilled people,” said Jeff Moskaluk, senior vice president at SSAB Americas, a supplier of steel to the icebreaker program. “It’s not like you just treat it the same as any other piece of steel. It takes a beating—that’s exactly what the steel is designed for.”

In addition to the technical challenge, American yards are reckoning with a shortage of shipwrights. Employment in ship and boat building totaled just 154,800 in July after peaking at 1.3 million during World War II, according to data from the Federal Reserve.

“One of the challenges is the workforce—getting qualified welders,” said Bob Merchent, retired former chief executive of VT Halter Marine, since acquired by Bollinger Shipyards.

The U.S. government identified the need for half a dozen new polar vessels as far back as 2010. Two years later, the Coast Guard launched a program to acquire them.

In 2014, Russia’s seizure of Crimea soured hopes for post-Cold War cooperation in the Arctic. Meanwhile, China was building up reefs in the Pacific to boost its maritime claims and has since declared itself a “near-Arctic state” with an interest in Arctic policy.

Under a joint Coast Guard-Navy program in 2017, Bollinger Shipyards and Halter Marine won contracts for preliminary designs for the new icebreakers. In 2019, Halter Marine won the contract for the polar security cutters, but the pandemic and other delays have slowed design and engineering work and prevented the start of construction.

“When Covid hit, all of our suppliers were overseas,” Merchent said.

In 2020, a Finnish official spoke with President Donald Trump about leasing icebreakers to the U.S. more quickly and at a much lower cost than the U.S. could build on its own, another Finnish official said. The U.S. didn’t buy one and has no plans to.

A Trump spokesman declined to comment on the discussion. U.S. law generally bars the use of foreign ships for government and military purposes.

In 2022, as Russian President Vladimir Putin launched two giant icebreakers in St. Petersburg, Halter Marine was finally supposed to start construction of the first new icebreaker, to be christened the Polar Sentinel.

Instead the company, which was owned by a state-owned Singaporean firm with Chinese clients, was sold to Bollinger.

The U.S. icebreakers needed a bigger company with more resources to complete the design work and begin working with the steel, according to people familiar with the program.

Meanwhile, the Coast Guard and members of Congress last year considered buying an icebreaker, the 361-foot Aiviq built for the oil-and-gas industry, according to people familiar with the matter.

Officials were initially dissuaded by the amount of work needed to retrofit her for the armed services, but a Coast Guard official said the purchase is still under consideration.

The Aiviq is moored on Bayou Casotte, where the new icebreakers will be built. The Aiviq’s owner, Edison Chouest Offshore, declined to comment.

Only in August did Bollinger begin testing, cutting and assembling steel prototype modules that could become part of the Polar Sentinel—if the modules meet rigorous tests.

Meanwhile, the company will continue recruiting and training more shipyard workers. Full construction could begin next year.

“We’re relearning how to build this type of ship,” said the polar security cutter program manager, Coast Guard Capt. Eric Drey.

Updated: 9-18-2023

Russia Quits Barents Euro-Arctic Council In Spat Over Presidency

Russia announced it’s withdrawing from the Barents Euro-Arctic Council, which it said had been “virtually paralyzed” since the Kremlin’s invasion of Ukraine.

The Foreign Ministry in Moscow accused Finland, which currently holds the body’s rotating presidency, of “disrupting” preparations for Russia to assume the leadership in October. There was no immediate response from Finland.

Russia also blamed the council’s other members, Denmark, Iceland, Norway, Sweden and the European Commission, for a lack of cooperation since it started the war last year.

The council was established in 1993 to foster cooperation among states in the Barents Sea area with the aim of avoiding a repeat of the military tensions that built up during the Cold War.

Updated: 10-2-2023

China Is Gaining Long-Coveted Role In Arctic, As Russia Yields

Isolated over Ukraine invasion, Moscow seeks Beijing’s help as it ships more oil east through polar routes.

HONG KONG—China’s goal of becoming a major player in the Arctic has long been frustrated by its neighbor Russia, which has closely protected its dominant role in the region.

Now, along with the ice that encases the earth’s northern pole, Moscow’s resistance is beginning to thaw.

Faced with economic isolation over its invasion of Ukraine, Russia is turning to China for help developing the Arctic as Western energy companies are trying to pull out of Russian projects.

The newfound cooperation is most evident in surging shipments of crude through the Northern Sea Route, which traverses the Arctic from northwestern Russia to the Bering Strait.

The volume, while still small compared with what is carried via southern routes, has shot up in recent weeks. Russia asserts the right to regulate transit on the route.

It says the demand has driven it to permit larger tankers without so-called ice classification—stronger hulls and other reinforcements to sail the ice-filled waters—raising fears of spills in the remote region.

The first of two larger tankers arrived at a Chinese port in recent days, each carrying more than one million barrels of oil.

Russia has joined with China in naval exercises and maritime security arrangements in the far north, and looked to it for aid in technology such as satellite data to monitor ice conditions.

When it comes to the Arctic, China “doesn’t have to care so much about official Russian policy anymore,” said Marcus M. Keupp, an economics lecturer at the military academy of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich who studies the region.

For China, which declared itself a “near Arctic” nation in 2018 despite being more than 900 miles from the Arctic Circle, Russia’s new welcome provides a long-sought opportunity.