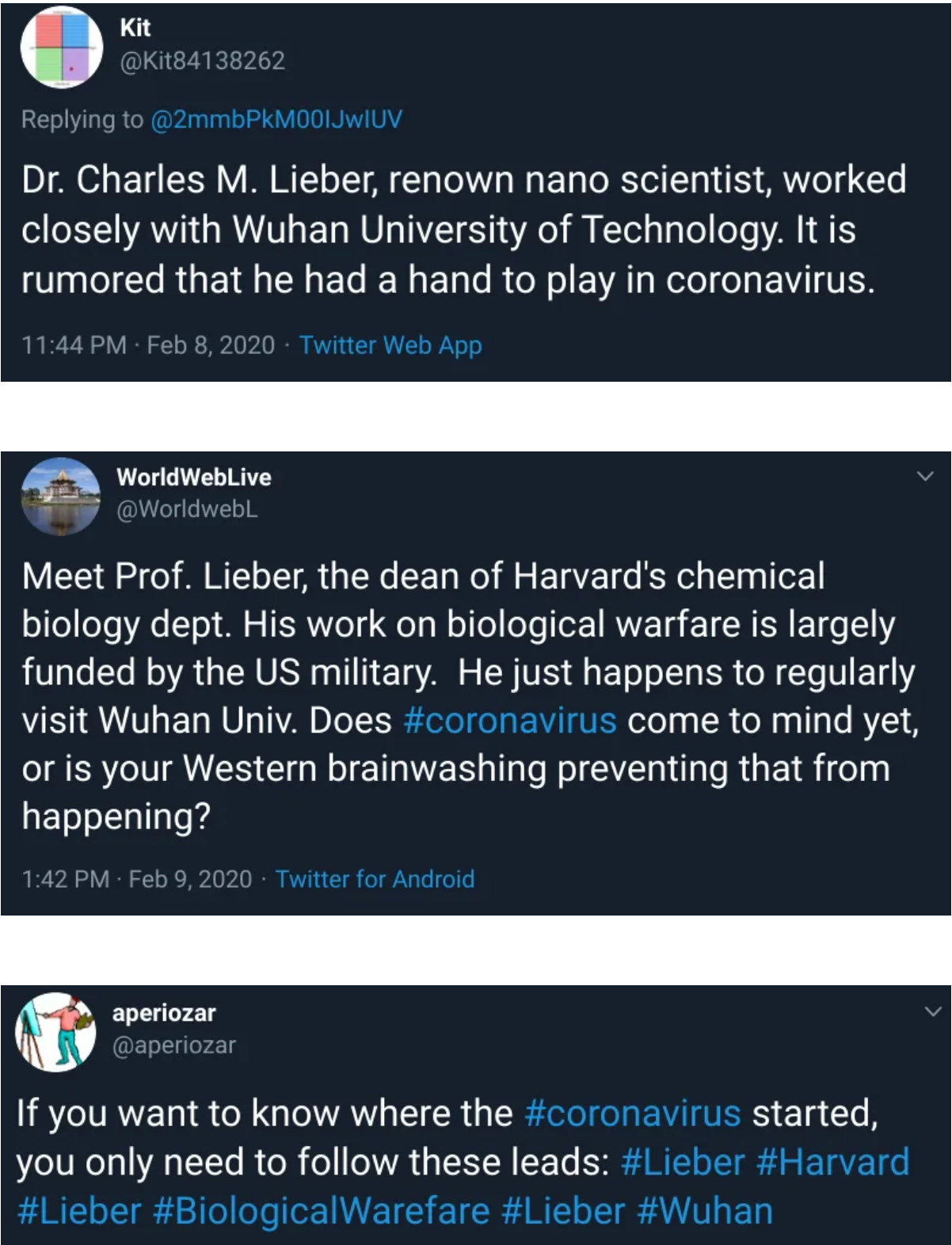

Harvard Chemical Biology Department Chair Accused Of Selling Covid19 To Wuhan University

Harvard Professor Among Three Charged With Lying About Chinese Government Ties. Harvard Chemical Biology Department Chair Accused Of Selling Covid19 To Wuhan University

He was being paid $50,000 per month by the Chinese university and given $1.5 million to establish a nanoscience research lab at WUT, the complaint said.

A Harvard University professor and two other Chinese nationals were federally indicted in three separate cases for allegedly lying to the US about their involvement with China’s government, the US attorney for the district of Massachusetts announced Tuesday.

Federal authorities told reporters the cases highlighted the “ongoing threat” posed by China using “nontraditional collectors” like academics and researchers to steal American research and technology.

Related:

Ultimate Resource On Long COVID or (PASC)

Paying Off Unfunded Pension Liabilities Will Be A Low Priority After COVID-19

US Says China Backed Hackers Who Targeted COVID-19 Vaccine Research

Ultimate Resource For Covid-19 Vaccine Passports

Companies Plan Firings For Anti-Vaxers And Giveaways For Covid-19 Vaccine Recipients

Four Stories Of How People Traveled During Covid

How To Travel Luxuriously Post- Covid-19, From Private Jets To Hotel Buyouts

‘I Cry Every Day’: Olympic Athletes Slam Food, COVID Tests And Conditions In Beijing

Lessons Of The Great Depression: Preserving Wealth Amid The Covid-19 Crisis

Cyber Attack Hits Health And Human Services Department Amid Covid-19 Outbreak

Dr. Charles Lieber, 60, who is the chair of Harvard’s Chemistry and Chemical Biology Department, is accused of lying about working with several Chinese organizations, where he collected hundreds of thousands of dollars from Chinese entities, US Attorney Andrew Lelling said at a news conference.

According to court documents, Lieber’s research group at Harvard had received over $15 million in funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Defense, which requires disclosing foreign financial conflicts of interests.

The complaint alleges that Lieber had lied about his affiliation with the Wuhan University of Technology (WUT) in China and a contract he had with a Chinese talent recruitment plan to attract high-level scientists to the country.

CNN has reached out to an attorney for Lieber. In a statement, Harvard called the charges “extremely serious.”

“Harvard is cooperating with federal authorities, including the National Institutes of Health, and is conducting its own review of the alleged misconduct,” the university said in a statement. “Professor Lieber has been placed on indefinite administrative leave.”

In a separate indictment unsealed Tuesday, Yanqing Ye, a 29-year-old Chinese national, was charged with visa fraud, making false statements, conspiracy and being an unregistered agent, the US attorney’s office said.

Yanqing had falsely identified herself as a “student” on her visa application and lied about her military service while she was employed as a scientific researcher at Boston University, according to the indictment. She admitted to federal officers during an April 2019 interview that she held the rank of lieutenant with the People’s Liberation Army, court documents show.

Yanqing is accused of accessing US military websites and sending US documents and information to China, according to documents.

Last week, a cancer researcher, Zaosong Zheng, was indicted for trying to smuggle 21 vials of biological material out of the US to China and lying about it to federal investigators, Lelling said.

Zaosong, 30, whose entry was sponsored by Harvard University, had hidden the vials in a sock before boarding the plane, according to Lelling.

“This is not an accident or a coincidence. This is a small sample of China’s ongoing campaign to siphon off American technology and know-how for Chinese gain,” Lelling said.

Lelling said Boston is a target for this “kind of exploitation” because of its universities, hospitals, research institutions and tech companies in the area.

Lieber is scheduled to appear later Tuesday afternoon in federal court in Boston. Yanqing is currently in China.

Zaosong was arrested and charged last month. He has been detained since December 30.

CNN has reached out to an attorney Zaosong. It was not immediately clear if Yanqing had a lawyer.

Case of Chinese researcher at Boston University renews fears Beijing is targeting American academia.

When a researcher from a Chinese military academy applied to study with celebrated Boston University physicist Eugene Stanley, he said her affiliation didn’t raise red flags.

“I’m not interested at all in politics. I’m a scientist,” said Mr. Stanley, whose wide-ranging research has included using artificial intelligence to decode financial markets and applying statistical physics to prevent diseases.

The recent indictment of the researcher, who is accused of lying on her U.S. visa application to conceal she is a lieutenant in the Chinese military, shows how U.S. universities’ openness to international collaboration in cutting-edge research leaves them vulnerable to potential exploitation.

Mr. Stanley said that he receives droves of research requests and that he vets candidates’ scientific credentials. A Boston University spokesman said the school doesn’t engage in classified research and relies on the State Department to screen foreign applicants for national-security risks.

A range of U.S. agencies, from the Defense Department to the National Institutes of Health, have sounded alarms over Beijing’s alleged attempts to tap U.S. university expertise to boost China’s military and technological competitiveness.

U.S. officials accuse China of targeting academia, including by sending military researchers to American labs and using talent-recruitment programs to attract to China top-flight scientists, entrepreneurs and experts, as well as their intellectual property.

Beijing has denied any systematic effort to steal U.S. scientific research, and Chinese state media have called U.S. allegations of intellectual-property theft a political tool.

Federal prosecutors in Boston brought the most high-profile China recruitment case to date last month when they charged the chair of Harvard University’s chemistry department with deliberately lying about receiving millions of dollars in funding through Beijing’s Thousand Talents Plan. According to the complaint, Prof. Charles Lieber, who hasn’t entered a plea, signed a five-year agreement to conduct research on a battery technology to power electric vehicles, a field China wants to dominate.

A review by officials with the Texas A&M University System found that more than 100 faculty at its schools were involved with Chinese talent-recruitment programs, though only five had disclosed their participation.

Some university leaders have dismissed U.S. officials’ national-security concerns as exaggerated and discriminatory and said there should be no restrictions on unclassified research that is meant to be published. They have also said that international collaboration—particularly with China, given its trove of science and engineering talent—is essential to advancing scientific discovery.

Despite commitment to open exchanges, universities should consider drawing the line at working with China’s People’s Liberation Army, or PLA, suggests a 2018 report by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, an Australian government-backed, nonpartisan think tank.

“Helping a rival military develop its expertise and technology isn’t in the national interest,” says the report by researcher Alex Joske. He found China’s military sponsored more than 2,500 scientists and engineers to study abroad over the prior decade, at times without their host schools’ knowledge of their military affiliation.

In the Boston University case, federal prosecutors accused Yanqing Ye of acting as an agent of a foreign government. On her application for a J-1 visa used for scholarly exchanges, she said she was a student at China’s National University of Defense Technology, but omitted that she was a lieutenant in the PLA, according to the indictment. It said she carried out assignments from military colleagues while at Boston University from 2017 to 2019.

A search of Ms. Ye’s electronic devices at Boston’s Logan Airport last April revealed messages instructing her to research a computer-security professor at the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, Calif. “Sure Teacher…I will start work on it immediately,” she replied, according to the indictment.

Ms. Ye didn’t respond to email requests for comment, nor did her university, which is one of the Chinese military’s leading research institutes. The Federal Bureau of Investigation, which recently issued a “Wanted” poster for her, said she is likely back in China.

Mr. Stanley, 78, is a renowned expert in statistical physics, having received numerous honors and fellowships. His lab has attracted more than 200 research associates and visiting scientists, including around 75 that appear to be from China, according to a copy of his résumé.

“If a person anywhere in the world wants to come to my group, and they have the money to come, I say why not?” he said, in an interview with The Wall Street Journal.

The Boston University spokesman said Mr. Stanley has been on leave since March 2019 and will retire at the end of 2020. He said that while the professor has brought collaborators from all over the world, the university applies the same criteria in reviewing visiting scholars, assessing their funding and academic credentials, among other factors.

In the fiscal year that ended on June 30, 2019, Boston University hosted 1,294 international scholars from 96 countries, with China as the top source, school data shows. Over the past year, the spokesman said, school administrators have educated faculty about U.S. government concerns of foreign influence and a policy-review committee has also made recommendations, which are being implemented.

The spokesman said the school counts on the U.S. State Department to vet visa requests “against organizations or individuals that are of concern to the U.S. government.”

A State Department spokesman declined to discuss specific cases but said that the Immigration and Nationality Act gives limited authority to deny visas. Currently, the spokesman said, consular officers may deny a visa on national-security grounds if they believe the applicant might intend to export a technology on a U.S. government control list. Many technologies, and basic research like that done in Mr. Stanley’s lab, aren’t on export-control lists.

Mr. Stanley said he is “totally overwhelmed” by the allegations against Ms. Ye. He said he doesn’t remember Ms. Ye well but found in his files a 2016 paper about machine learning that he had co-written with her and others before her stint at his lab in Boston. One of the co-authors was Ms. Ye’s university colleague Kewei Yang, a PLA colonel.

Machine learning, a field of AI, teaches computers to think like humans and has a range of civilian and military applications.

Col. Yang, identifiable as “Co-conspirator A” in the indictment, is accused of directing Ms. Ye while she was in Boston. He didn’t respond to requests for comment. On the paper he co-wrote with Ms. Ye and Mr. Stanley, both list their affiliations as National University of Defense Technology.

In 2015, the U.S. put the university on an export blacklist after finding it used U.S. semiconductors to build supercomputers, which, in addition to civilian tasks, are used in the development of nuclear weapons, encryption, missile defense and other systems. In a 2018 superseding indictment, Massachusetts prosecutors alleged the university was a top customer of a defendant accused of illegally exporting U.S. marine technology.

“Is it a bad place? I don’t know,” said Mr. Stanley, when asked if he had concerns about working with scholars from that school.

Updated: 12-14-2021

Harvard Professor Goes On Trial On Charges of Lying About China Ties

Government alleges that nanoscience expert Charles Lieber misled government, university about his links to Wuhan University of Technology.

Harvard chemistry professor Charles Lieber went on federal trial in Boston Tuesday over whether he misled the U.S. Defense Department and others about his relationship with a Chinese university, testing the government’s policing of U.S.-China collaborations after a similar case ended in an acquittal earlier this year.

Mr. Lieber, a pioneer in the field of nanoscience, was arrested in January 2020 on charges of lying to government agents about his involvement with a Chinese talent-recruitment program and the money he received through it. He has pleaded not guilty to those and related tax charges, and his lawyers have argued he didn’t mean to mislead anyone about his affiliations.

Jury selection consumed much of Tuesday morning behind closed doors, with U.S. District Judge Rya Zobel ultimately seating a jury of ten men and four women on Tuesday afternoon. Opening statements in the closely watched trial are set to begin on Wednesday morning.

Prosecutors alleged that, starting in 2012, Mr. Lieber participated in China’s Thousand Talents program and was under contract to be paid up to $50,000 a month to work at the Wuhan University of Technology, advising students and researchers there.

Instead he told both Defense Criminal Investigative Service agents and the National Institutes of Health in 2018 and 2019 that he was never asked to be a part of the Chinese program, the indictment alleged.

The trial comes as the Justice Department has struggled with an initiative aimed at stopping the transfer of American technology, research and other proprietary information to China. U.S. officials have worried that losing leadership in key scientific fields could lead to the U.S. being eclipsed as the world superpower.

Prosecutors have accused more than a dozen academics of lying about their China affiliations when applying for federal taxpayer support for their research. While such affiliations aren’t illegal, prosecutors said funding agencies need a clear picture of them before making decisions about what projects to support.

Citing Mr. Lieber’s Chinese contract, prosecutors said he was obligated to “conduct national important (key) projects…that meet China’s national strategic development requirements or stand at the forefront of international science and technology research field.”

Some of the professors facing similar charges have pleaded guilty while others have said the rules about what needed to be reported weren’t previously clear and argued they never intended to deceive.

In a March letter, dozens of colleagues of Mr. Lieber, who is 62 years old and suffering from an incurable lymphoma, described him as the victim of an “unjust criminal prosecution” and said the cases were “discouraging U.S. scientists from collaborating with peers in other countries, particularly China.”

Some former national-security prosecutors said such support could help Mr. Lieber with the jury. “He will have the opportunity to have witnesses testify to his reputation for truthfulness. That can be powerful evidence for a jury to hear,” said Michael Atkinson, a former prosecutor and inspector general for U.S. intelligence agencies who is now at the law firm Crowell & Moring.

Civil liberties and academic groups have criticized the cases for creating an environment of suspicion that they say stigmatized Chinese and other Asians, pointing to the acquittal in September of University of Tennessee-Knoxville professor Anming Hu on charges that he hid his China ties when applying for research grants to work on a NASA project.

When Rep. Ted Lieu (D., Calif.) asked Attorney General Merrick Garland in October about the Tennessee case and how the department could ensure it wasn’t wrongfully targeting people of Asian descent, Mr. Garland said the new head of the Justice Department’s national-security division would review the division’s activities. “I can assure you that cases will not be pursued based on discrimination, but only on facts justifying them,” Mr. Garland said.

The federal judge who acquitted Mr. Hu said the rules governing the research awards were confusing and prosecutors had provided no evidence that the professor intended to hide information from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the agency that had supported his work.

In Mr. Lieber’s case, prosecutors have pointed to some of Mr. Lieber’s emails and alleged that he knew he was misleading government agents.

In one email, for example, Mr. Lieber allegedly told an associate two days after his interview with Defense Department agents: “I will be careful about what I discuss with Harvard University, and none of this will be shared with government investigators at this time.”

In a memo filed last week, prosecutors said they planned to introduce other emails and evidence showing Mr. Lieber agreed in 2011 to serve as a “strategic scientist” for the Wuhan University of Technology, where one of his former postdoc students worked, and that, in 2012, he agreed to the Thousand Talents contract and performed work under it.

The Wuhan school had also appointed Mr. Lieber as director of the WUT-Harvard Joint Nano Key Laboratory, a lab that Harvard officials said they had no knowledge of and hadn’t approved as a collaborator.

When Defense Department investigators interviewed Mr. Lieber in 2018, he told them he “wasn’t sure” how China characterized him, prosecutors said.

The government said it planned to show that Mr. Lieber lied to protect his reputation and career at Harvard, and to preserve his ability to receive federal research funding.

Mr. Lieber unsuccessfully sued Harvard last year to cover his legal expenses. The university said his actions weren’t covered under its indemnification policies, arguing, “the known facts show that he intentionally lied to Harvard and federal authorities about his activities in China.”

Updated: 12-20-2021

The U.S. Pursued Professors Working With China. Cases Are Faltering

MIT professor’s academic collaboration in Shenzhen led to criminal charges, but the university says such ties are ordinary practice.

In January 2020, Gang Chen and about two dozen other professors and students from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology traveled to Shenzhen, China, to talk about overlapping university research, visit local companies and interview students interested in studying at MIT.

When Mr. Chen landed back at Boston’s Logan airport, Customs and Border Protection agents pulled him aside, seized his laptop and two cellphones and began asking him what he had been doing in China and why. Mr. Chen, a professor of mechanical engineering and an American citizen, told them he had been collaborating with a Chinese university and that all his research had been conducted in the U.S.

One year later, he was arrested on charges of concealing extensive ties to China in grant applications he had made to the U.S. government. It was one of a string of attention-grabbing cases brought by the Justice Department to address suspicions that the Chinese government was exploiting academic ties to engage in technological espionage.

Since then, the government’s pursuit of academics for alleged lying about their affiliations has faltered. The first such case to go to a jury ended in an acquittal. Out of 24 other cases, nine defendants have pleaded guilty. Charges have been dropped completely in six others, five of which officials said they dismissed because the scientists involved already had been sufficiently punished by being detained or otherwise restricted for a year.

The rest are pending, including one against a professor at Harvard University who went on trial on Dec. 14. By comparison, about 92% of the Justice Department’s overall white-collar prosecutions end in convictions.

In recent weeks, Justice Department officials have discussed whether to drop additional cases against academics, including Mr. Chen, according to people familiar with the matter. Mr. Chen has pleaded not guilty.

The allegations against Mr. Chen and others, which came amid sharp anti-China rhetoric from the Trump administration, sparked criticism from some in academia that the Justice Department was improperly targeting American scientists of Chinese descent—something the department has denied.

At a minimum, the cases showed that at times what the Justice Department saw as suspicious contacts between American professors and scientists and government officials in China were something the universities regarded as ordinary academic collaboration.

Attorney General Merrick Garland, questioned by a lawmaker in October about the cases, said the new head of the Justice Department’s national security division planned to review the department’s approach to countering threats posed by the Chinese government. A spokesman said that review would be completed soon, and the agency would provide additional information in the coming weeks.

Chinese officials have called on the U.S. to halt the effort. In a written statement, Liu Pengyu, a representative of the Chinese Embassy in Washington, said that China’s policies in connection with U.S. scientists “are no different from the common practice of other countries,” and that U.S. authorities should “stop stigmatizing China’s programs.” The embassy didn’t comment on the details of Mr. Chen’s case.

The U.S. effort seems to have helped Beijing attract Chinese-American scientists to China. More than half a dozen top researchers of Chinese descent said in interviews they had either moved from posts at U.S. universities to China or were looking for a chance to do so, saying they feared becoming a target of what they viewed as Justice Department overreach.

The federal government has estimated that each year more than $225 billion in intellectual property is lost to China. National-security officials have said publicly that U.S. universities are a key conduit in that loss of technology.

Beginning in about 2018, as the Trump administration criticized a variety of China’s trade and technology practices, the Federal Bureau of Investigation and U.S. agencies that sponsor much university research began flagging instances where grant recipients appeared to be trying to transfer sensitive technologies to China and to hide Chinese funding when applying for U.S. government support.

Separately, American officials urged universities to more thoroughly vet certain types of collaborative research with institutions in China, citing Chinese law that allows the government to tap any technology or research conducted under such collaborations to advance its own interests.

In 2019, federal prosecutors began charging academics with lying to U.S. grant-giving agencies about their China connections. In the summer of 2020, FBI Director Christopher Wray told lawmakers that the agency was opening a China-related counterintelligence case every 10 hours, and warned that Americans “are the victims of what amounts to Chinese theft on a scale so massive that it represents one of the largest transfers of wealth in human history.”

On Jan. 13, days before President Biden’s inauguration, prosecutors charged Mr. Chen with failing to disclose some of his ties to China to the Energy Department, which funded some of his research. They alleged he had served as an adviser to the Chinese government, to a Beijing-funded development company and to the board at Shenzhen’s Southern University of Science and Technology, or SUSTech, the institution with which MIT was collaborating.

As agents investigated Mr. Chen, they suspected he had pursued the collaboration at SUSTech not to benefit MIT but to benefit China, according to people familiar with the matter.

“The allegations of the complaint imply that this was not just about greed, but about loyalty to China,” said Andrew Lelling, then the U.S. attorney in Massachusetts, in announcing the case.

In a later filing, lawyers for Mr. Chen, who became a naturalized American citizen in 2000, described Mr. Lelling’s “speculation” about Mr. Chen’s loyalty as “grossly insulting.”

From the moment that charges were filed, MIT has offered vigorous defenses of its professor and the university’s SUSTech collaboration, saying such cooperation was crucial to advancing science. MIT President Rafael Reif called the arrest “deeply distressing and hard to understand.”

In a group letter to Mr. Reif, more than 200 of Mr. Chen’s colleagues wrote: “The complaint against Gang vilifies what would be considered normal academic and research activities, including promoting MIT’s global mission.”

A lawyer for Mr. Chen, Robert Fisher, said his client was grateful for the support and “looks forward to his day in court.”

Mr. Chen was born in 1964 and grew up in China’s Hubei province, where his mother had been forced to move during the Cultural Revolution. His university assigned him to study thermal power, which his father thought meant he would become a boilermaker.

Instead a Chinese-American scientist recruited him to the University of California, Berkeley, where he earned a Ph.D. in mechanical engineering in 1993.

After stints at Duke University and the University of California, Los Angeles, he moved to MIT in 2001, assembling a large research group and churning out papers on topics such as how to use batteries to convert thermal energy into electricity. In 2013, he became head of MIT’s mechanical engineering department.

MIT, in Cambridge, Mass., has been cultivating ties with China since the mid-2010s.

By the mid-2010s, MIT was cultivating ties with China. It received $125 million from Chinese nationals and organizations between 2015 and 2019, more than any of its university peers, according to self-reported data collected by the Education Department.

It also received around $11 million from now-blacklisted Chinese telecom giant Huawei Technologies Co., other Education Department data show. The U.S. government alleges that Huawei gear could be used by Beijing to spy globally, which Huawei has denied.

Chinese diplomats in New York often dropped by MIT to visit Chinese students, and they were in frequent contact with Mr. Chen, who was one of the most cited researchers in his field and was well-known in China. Those contacts, captured as the U.S. monitored Chinese diplomats, landed Mr. Chen on the U.S. government’s radar, according to people familiar with the matter.

The diplomats asked Mr. Chen to serve in various posts. Mr. Chen spurned some Chinese requests and accommodated others. In 2013, he declined to serve on an advisory panel for the Chinese government, according to people familiar with his activities.

The next year, told it would involve minimal effort, he accepted the offer, but there is no record that he followed up or was paid for it, those people said.

In February 2016, China’s then vice minister of science and technology, Wang Zhigang, visited Boston and spoke to MIT officials and faculty, including Mr. Chen, both on campus and at a dinner with Chinese-American scientists. In the subsequent complaint against Mr. Chen, prosecutors cited notes he took on his phone that day as evidence of his efforts to advance China’s strategic goals.

The most recent convention of the Chinese Communist Party had “scientific innovation placed at core,” Mr. Chen had written, noting that the question was “how to promote MIT China collaborations.” Mr. Chen later said the notes merely reflected Mr. Wang’s words to him.

After the meeting, MIT’s associate provost for international affairs, Richard Lester, asked Mr. Chen how China’s science ministry could be a partner for MIT in China. “It would seem from today’s meeting that there is a possible path forward there,” Mr. Lester wrote in an email.

At MIT, officials were particularly interested in Shenzhen, a city adjacent to Hong Kong that had grown into an advanced manufacturing and technology center.

In 2016, Ma Xingrui, then-Communist Party secretary for Shenzhen, pushed visiting U.S. professors for partnerships between the city’s institutes and U.S. universities, including the Georgia Institute of Technology and Stanford University. He suggested to Mr. Chen that he consider a collaboration between MIT and SUSTech, the university the city’s government had set up to complement the economic growth.

Former national-security officials not connected to Mr. Chen’s case said SUSTech’s recruitment of scientists with experience at labs run by the U.S. Department of Energy, including the SUSTech’s past president, had raised suspicions among government security officials.

MIT officials viewed a SUSTech collaboration favorably, given SUSTech’s Western-trained faculty and its decision to teach many classes in English. They believed Shenzhen’s manufacturing prowess would be valuable for MIT students to experience.

U.S. investigators were concerned about Mr. Chen’s continued contacts with Chinese government officials as he kept them apprised of the SUSTech-MIT plans.

In January 2017, Mr. Chen accompanied a dozen MIT faculty members to SUSTech for a workshop to discuss areas in which the two schools could cooperate.

That February, a Chinese diplomat sent Mr. Chen another note that was flagged by prosecutors. In it, Mr. Chen was told that the science ministry had launched a new area of funding for “key special projects” between China and other governments. The diplomat encouraged Mr. Chen to consider the MIT-SUSTech collaboration as such a project, provided he obtain related U.S. government funding. Mr. Chen never responded.

One month later, Mr. Chen renewed a grant he has received for more than a decade from the Energy Department, to continue his research into how atoms vibrate and carry heat in plastics.

Mr. Chen was reimbursed for his travel to speak at a California conference hosted by ZGC Capital Corp., a Silicon Valley fund affiliated with Zhongguancun Development Group, a company funded by the city of Beijing that was a member of an MIT program that connects faculty with industry. Prosecutors later alleged he hid from the Energy Department a post ZGC offered him. He turned down the post but continued to work with the Beijing company through the MIT program, people familiar with the matter said.

In the fall of 2017, Mr. Chen took a paid position to mentor students at a middle school in Chongqing, whose headmaster, Wu Xianhong, was the founder of investment company Verakin and had endowed a fellowship at MIT. Mr. Chen gave a speech there, encouraging students not to fear science.

Mr. Wu’s investment company advertised the affiliation, saying it offered a talent program that had “famous experts and professors from top universities” as tutors. Prosecutors said in the indictment that Mr. Chen hid that post from the U.S. as well. Lawyers for Mr. Chen have argued he was under no obligation to disclose it.

In June 2018, MIT and SUSTech struck a deal under which SUSTech agreed to pay MIT $25 million over five years. SUSTech would send some faculty members and students to MIT each year, and MIT faculty members and students would travel to Shenzhen. That fall, Mr. Chen took a sabbatical from MIT and spent part of the semester at SUSTech.

That November, MIT continued to expand its engagement with China, hosting with the Chinese Academy of Sciences a science and technology conference in Beijing. MIT’s president and Mr. Chen introduced the event.

The event included discussions between MIT professors and the founders of technology companies iFlytek Co. Ltd. and SenseTime. The following year, the U.S. Commerce Department added both firms to its blacklist, accusing them of playing a role in Beijing’s repression of Muslim minorities in northwest China. SenseTime described the allegations as unfounded, and iFlytek has said the U.S. move wouldn’t have a serious effect on its business. MIT has since terminated a research collaboration with iFlytek.

In 2019, Congress held a hearing in which U.S. national-security officials warned about scientific interactions with China.

That April, MIT said it wouldn’t renew its contracts with Huawei, and would intensify its vetting of projects that involved China, Russia or Saudi Arabia. Apparently, it didn’t think its January 2020 visit to SUSTech—which preceded Mr. Chen being questioned at the airport—would present any problem.

After Mr. Chen’s arrest early this year, Mr. Reif, MIT’s president, indicated that MIT and the government appeared to be construing the SUSTech collaboration very differently. “These funds are about advancing the work of a group of colleagues, and the research and educational mission of MIT,” he said. MIT has continued to pay Mr. Chen’s legal bills.

In a recent LinkedIn post, Mr. Lelling, the former Massachusetts U.S. attorney whose office charged Mr. Chen, said he thought the Justice Department should rethink its efforts to “avoid needlessly chilling scientific and business collaborations with Chinese partners.”

Meanwhile, professors at MIT and SUSTech are continuing their collaborations. University officials say they are still working to figure out how to respond to the growing calls to decouple the U.S. and Chinese economies while maintaining a welcoming research environment.

At an October hearing on research security before a House subcommittee, MIT’s vice president for research, Maria Zuber, said law enforcement and the university would benefit from better understanding each other, given the differences in the ways they work and share information. “It’s a work in progress,” she said.

Updated: 12-23-2021

Harvard Professor Found Guilty Of Hiding Ties To China

A Harvard University professor charged with hiding his ties to a Chinese-run recruitment program was found guilty on all counts Tuesday.

Charles Lieber, 62, the former chair of Harvard’s department of chemistry and chemical biology, had pleaded not guilty to two counts of filing false tax returns, two counts of making false statements, and two counts of failing to file reports for a foreign bank account in China.

The jury deliberated for about two hours and 45 minutes before announcing the verdict following five days of testimony in Boston federal court.

Lieber’s defense attorney Marc Mukasey had argued that prosecutors lacked proof of the charges. He maintained that investigators didn’t keep any record of their interviews with Lieber prior to his arrest.

He argued that prosecutors would be unable to prove that Lieber acted “knowingly, intentionally, or willfully, or that he made any material false statement.” Mukasey also stressed Lieber wasn’t charged with illegally transferring any technology or proprietary information to China.

Prosecutors argued that Lieber, who was arrested in January, knowingly hid his involvement in China’s Thousand Talents Plan — a program designed to recruit people with knowledge of foreign technology and intellectual property to China — to protect his career and reputation.

Lieber denied his involvement during inquiries from U.S. authorities, including the National Institutes of Health, which had provided him with millions of dollars in research funding, prosecutors said.

Lieber also concealed his income from the Chinese program, including $50,000 a month from the Wuhan University of Technology, up to $158,000 in living expenses and more than $1.5 million in grants, according to prosecutors.

In exchange, they say, Lieber agreed to publish articles, organize international conferences and apply for patents on behalf of the Chinese university.

The case is among the highest profile to come from the U.S. Department of Justice’s so-called “China Initiative.”

The effort launched in 2018 to curb economic espionage from China has faced criticism that it harms academic research and amounts to racial profiling of Chinese researchers.

Hundreds of faculty members at Stanford, Yale, Berkeley, Princeton, Temple and other prominent colleges have signed onto letters to U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland calling on him to end the initiative.

The academics say the effort compromises the nation’s competitiveness in research and technology and has had a chilling effect on recruiting foreign scholars. The letters also complain the investigations have disproportionally targeted researchers of Chinese origin.

Lieber has been on paid administrative leave from Harvard since being arrested in January 2020.

Updated: 1-14-2022

Prosecutors Recommend Dropping Case Over China Ties Against MIT Scientist

Possible reversal comes as Justice Department reviews its initiative to counter Chinese government activities in U.S.

Federal prosecutors have recommended that the Justice Department drop criminal charges against a Massachusetts Institute of Technology mechanical engineering professor accused of hiding his China ties, according to people familiar with the matter, as the Biden administration reviews an effort to counter Chinese influence at U.S. universities.

Gang Chen was arrested last January on charges of concealing posts he held in China in a grant application he had made to the U.S. Department of Energy in 2017. Justice Department officials have decided to drop the indictment against Mr. Chen, in part based on new information from an Energy Department official, said the people.

The official told prosecutors in recent weeks that the agency didn’t believe Mr. Chen had an obligation to disclose the posts at the time, and didn’t believe the department would have withheld the grant if they had known about them, the people said. The Energy Department has since started asking researchers for more information about their foreign connections.

Government investigators pursued Mr. Chen on suspicions that he had forged a collaboration between MIT and a university in Shenzhen to benefit China, though the collaboration had the support of MIT, The Wall Street Journal reported in December. Some of the posts Mr. Chen was accused of hiding were either connected to his relationships through MIT or those he wasn’t paid for.

Prosecutors could ask the court to dismiss the charges in the coming weeks but the decision hasn’t yet been completed and the timing could still slip, the people said. On Tuesday, prosecutors and Mr. Chen’s lawyers asked to delay a status conference scheduled for this week saying the parties were discussing legal issues pertinent to the case.

A lawyer for Mr. Chen, Rob Fisher, said on Friday: “Professor Chen was arrested one year ago today. It has been a long road, but we are still fighting to clear his name and get him back to his research and teaching at MIT.”

Mr. Chen was one of around two dozen academics charged since 2019 with allegedly lying about their affiliations, in attention-grabbing cases brought by the Justice Department to address suspicions that the Chinese government was exploiting academic ties to engage in technological espionage.

Some of the cases have been successful for the U.S. government. A jury convicted Harvard University chemistry professor Charles Lieber in December, for example, of lying to Defense Department investigators and others about his participation in the Chinese government’s Thousand Talents program aimed at wooing foreign experts.

But another case, the first to go to trial, ended in an acquittal in September and prosecutors have dropped several others.

A former federal prosecutor in Kansas who was involved in the first such case brought in 2019 said the goal of the cases was to interrupt what U.S. officials viewed as Chinese intelligence operations. “We debated, do we continue to investigate and prove the national security charges or indict on fraud. Our answer was, indict now to interrupt the operation,” said Tony Mattivi, who is now running for the Republican nomination to be attorney general in Kansas.

According to academic critics, the Justice Department has at times cast suspicion on contacts between American researchers and Chinese government officials that the universities regarded as ordinary academic collaboration.

Attorney General Merrick Garland said in October that he would task the Justice Department’s assistant attorney general for national security, Matt Olsen, with reviewing the department’s approach to countering threats posed by the Chinese government. The Justice Department is expected to provide more information about the results of that review in the coming weeks, a spokesman has said.

In a January 2021 indictment, prosecutors accused Mr. Chen of wire fraud, false statements and failing to report a foreign bank account.

They alleged that in 2017, when Mr. Chen applied for a research grant from the Energy Department, he didn’t report a consulting role with the Chinese government, an advisory board position with the Shenzhen university, an “overseas strategic scientist” role with a company linked to the Beijing city government, and roles as a review expert for the National Science Foundation of China and an adviser to the Chinese Scholarship Council.

After the charges were filed, dozens of Mr. Chen’s colleagues said several of those posts, which involved reviewing project proposals and recommending students for scholarships, were activities that most academics engaged in, including for China and other foreign governments. They also noted that the grant application forms had previously asked for limited information in connection with foreign contacts.

Updated: 1-20-2022

U.S. Drops Case Against MIT Professor Accused of Hiding China Ties

Gang Chen was one of around two dozen academics charged since 2019 with allegedly lying about their affiliations.

Federal prosecutors dropped criminal charges against a Massachusetts Institute of Technology mechanical engineering professor accused of hiding his China ties, saying in a Thursday filing that the government no longer believed it could prove its case at trial.

Gang Chen was arrested last January on charges of concealing posts he held in China in a grant application he had made to the U.S. Department of Energy in 2017. The Wall Street Journal reported last week that prosecutors had recommended that the Justice Department drop the case, based in part on witness testimony that investigators obtained since his arrest, citing people familiar with the matter.

One of those people included an Energy Department official who told prosecutors in recent weeks that the agency didn’t believe Mr. Chen had an obligation to disclose the posts at the time, and didn’t believe the department would have withheld the grant if officials had known about them. The Energy Department later started asking researchers for more information about their foreign connections.

“As a result of our continued investigation, the government obtained additional information bearing on the materiality of the defendant’s alleged omissions,” prosecutors wrote. “Having assessed the evidence as a whole in light of that information, the government can no longer meet its burden of proof at trial.”

The judge overseeing the case, U.S. District Judge Patti Saris, signed off on the dismissal, but could ask the government for more information about its decision.

In a statement, Mr. Chen’s lawyer, Rob Fisher, said: “The government finally acknowledged what we have said all along: Professor Gang Chen is an innocent man.” Mr. Fisher added that Mr. Chen was never in a Chinese government talent recruitment program and never served as an overseas strategic scientist for Beijing, as prosecutors had initially alleged.

In a separate statement, Mr. Chen thanked his friends and colleagues for their support “during this terrible year,” and said the Justice Department’s other similar cases continue “to bring unwarranted fear to the academic community and other scientists still face charges.”

In a December article, the Journal reported on how U.S. government investigators pursued Mr. Chen on suspicions that he had forged a collaboration between MIT and a university in Shenzhen to benefit China, though the collaboration had the support of MIT.

Some of the posts Mr. Chen was accused of hiding, the Journal reported, were either connected to his relationships through MIT or those he wasn’t paid for, and Justice Department officials had discussed dropping his case last year.

The U.S. Attorney in Boston, Rachael Rollins—who was sworn in to the post last week after Vice President Kamala Harris broke a tie on her confirmation—said in a statement that prosecutors had an obligation “to continually examine the facts while being open to receiving and uncovering new information.”

“Today’s dismissal is a result of that process and is in the interests of justice,” Ms. Rollins said.

MIT had supported Mr. Chen since his arrest and continued to pay his legal bills. After prosecutors’ Thursday filing, MIT President Rafael Reif posted a letter to the MIT community saying, “Having had faith in Gang from the beginning, we can all be grateful that a just outcome of a damaging process is on the horizon. We are eager for his full return to our community.”

Mr. Chen was one of around two dozen academics charged since 2019 with allegedly lying about their affiliations, in attention-grabbing cases brought by the Justice Department to address suspicions that the Chinese government was exploiting academic ties to engage in technological espionage.

Some of the cases have been successful for the U.S. government. A jury convicted Harvard University chemistry professor Charles Lieber in December 2021, for example, of lying to Defense Department investigators and others about his participation in the Chinese government’s Thousand Talents program aimed at wooing foreign experts.

But another case, the first to go to trial, ended in an acquittal in September after a judge said that prosecutors had provided no evidence that the professor intended to deceive the government, and prosecutors have dropped several other cases.

Attorney General Merrick Garland said in October that he would task the Justice Department’s assistant attorney general for national security, Matt Olsen, with reviewing the department’s approach to countering threats posed by the Chinese government. The Justice Department is expected to provide more information about the results of that review in the coming weeks, a spokesman has said.

Updated: 1-21-2022

Dropped MIT Case Shows The Perils Of The ‘China Initiative’

Racial profiling and an emphasis on disclosure and tax filings has investigators looking in the wrong places, to the detriment of American values.

Gang Chen wasn’t accused of spying, or taking bribes, or even of inappropriate handling of sensitive information. Instead, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology nanotechnologist was indicted a year ago for wire fraud and lying on his tax returns. But the Justice Department couldn’t even make those charges stick and dropped the case Thursday.

Chen was the latest innocent victim of the U.S. government’s four-year-old program called the China Initiative, aimed at cracking down on the theft of technology and trade secrets by China and those who work for it. 1 The department’s logic for running the operation seems sound, as outlined in an update published in November, three years after the initiative was formalized.

About 80 percent of all economic espionage prosecutions brought by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) allege conduct that would benefit the Chinese state, and there is at least some nexus to China in around 60 percent of all trade secret theft cases.

A skeptic would note that such figures, weighted heavily toward China-related cases, is a signal of confirmation bias — they’re looking for Chinese spies, so naturally they’re finding more Chinese spies. An analysis by Bloomberg News published in December found that just three of the 50 indictments announced or unsealed since the start of the China Initiative actually involved secrets being handed over to Chinese agents.

There are clear overtones of the Cold War era, when Senator Joseph McCarthy became the face of anti-communist investigations aimed at rooting out Soviet agents on American soil. Such inferences are not unwarranted today — China has sought to, and been successful in, stealing U.S. secrets to further its own economic and security goals. Indeed, the China Initiative has played a part in digging out some of those cases.

But it’s also made some serious errors. In doing so, it has hurt the people that law enforcement is meant to protect — U.S. citizens — and impinged on one of the nation’s greatest strengths: academic excellence. Critics have described it as racial profiling. The FBI has said there’s nothing racially motivated about these investigations.

“The China Initiative has had chilling effects on U.S. academic research and unjustly targeted Chinese American researchers through racial profiling,” wrote Zhengyu Huang, President of Committee of 100, a not-for-profit group of Chinese Americans in business, government, academia, healthcare, and the arts founded in 1990 by famed architect I.M. Pei, in a statement released Thursday.

On the surface, it might seem reasonable to believe that those with close ties to China — by birth, ethnicity, or business — are more likely to become deliberate or unwitting agents of Beijing. But that’s the wrong way to look at it. The vast majority of ethnic Chinese in the U.S. are simply living their lives, contributing to society, and enjoying the American Dream.

There have been successful prosecutions of Chinese nationals on U.S. soil. Earlier this month, Xiang Haitao pleaded guilty to conspiring to steal trade secrets in the agriculture industry. Yet, other defendants have also been successfully prosecuted.

Harvard University professor Charles Lieber was last month convicted of tax offences and making false statements. Lieber admitted to carrying bags of up to $100,000 in cash from Wuhan to Boston.

From an investigative point of view, focusing on one racial group risks incorrectly charging innocent victims, while missing those perpetrators who don’t fit the pre-conceived framework of a “likely suspect.” We’ve seen this play out with disastrous effect on African-American communities.

Just as important, this approach misses the forest for the trees. A key tenet for the U.S. ramping up the Tech Cold War, and bringing allies into the fight, is the belief in its own moral superiority. Freedom of speech, freedom of movement, due process, and the presumption of innocence are concepts which Washington and like-minded nations want to promote globally.

A rising China, which doesn’t pretend to advocate the same beliefs — instead emphasizing safety and stability — is a risk to these so-called American values. So when prosecutors start hunting down defendants based on race and file charges for crimes that are of little real risk to national security — tax and wire fraud is a far cry from stealing nuclear technology — they start to undermine these same ideals they’re supposedly promoting.

The failure of the Chen case heightens the need to reexamine the China Initiative: Attorney General Merrick Garland has previously pledged to review the program.

The threat from an increasingly assertive Beijing doesn’t disappear just because prosecutors bungled some cases. Indeed, China and its wolf warriors will seize on these failures as proof of its own righteousness and U.S. heavy-handedness. This should spur leaders in Washington to stay the course and continue to investigate those who seek to undermine national security by stealing technology or undermining the country’s political system.

But they should also remember the American values they’re sworn to serve and protect — including the right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty.

Updated: 1-26-2022

MIT Professor Gang Chen Says Misunderstanding Lay At Root of U.S. Case

Federal prosecutors dropped charges last week, a year after accusing the professor of hiding ties to China.

Witnesses started poking some holes in the government’s case against Gang Chen, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor accused of hiding his ties to China, soon after his arrest in January 2021, interviews and a review of related documents show, a year before prosecutors decided last week to drop criminal charges against him.

In an interview on Tuesday, Mr. Chen said he believed law-enforcement officials had miscalculated in bringing his case and some similar ones, in part because they are unfamiliar with how scientists work.

“I think they need to understand better how research is done,” he said, adding: “We need to do a better job to explain to them.”

Mr. Chen was one of around two dozen academics charged since 2019 with lying about their affiliations, in attention-grabbing federal cases—several of which have faltered—meant to address suspicions that the Chinese government was exploiting academic ties to engage in technological espionage.

National security officials say they believe some academics don’t understand the threat posed by the Chinese government.

Some of the cases have been successful. An electrical-engineering professor who worked at the University of Arkansas until 2020, for example, pleaded guilty last week to lying to the FBI about patents he held in China. Under his agreement with the government, he is expected to face one year in prison. A federal jury in Boston also convicted a Harvard University professor in December of similar charges.

In Mr. Chen’s case, many of his colleagues had criticized the charges against him from the outset and said the government was casting normal scientific practices as nefarious.

While the best scientists in the world have long wanted to come work in the U.S., Mr. Chen said he felt that attraction waning. “The U.S. should not take it for granted that we are a magnet,” he said, adding that he has learned in the past week about a half-dozen scientists leaving the U.S., with some of them citing his arrest as a reason.

Prosecutors recommended the dismissal of the case against Mr. Chen, who was arrested last January on charges of concealing posts he held in China in a grant application he had made to the U.S. Energy Department in 2017, as well as a tax charge.

That decision came after a Energy Department official told prosecutors earlier this month the agency didn’t believe Mr. Chen had an obligation to disclose the posts he was accused of hiding, and didn’t believe the department would have withheld the grant if they had known about them.

In a December article, The Wall Street Journal reported on how U.S. government investigators pursued Mr. Chen on suspicions that he had forged a collaboration between MIT and a university in Shenzhen to benefit China, though the collaboration had the support of MIT.

Some of the posts Mr. Chen was accused of hiding, the Journal reported, were either unpaid or connected to his relationships through MIT, and Justice Department officials had discussed dropping his case last year.

There were early indications that the case might not be clear-cut. In the hours after Mr. Chen’s arrest—as agents canvassed the house for possible espionage tradecraft, even asking about a magnet one of the Chen children had affixed to a lamp years earlier—his wife told them she was an accountant and that Mr. Chen didn’t handle any of the family’s taxes, possibly complicating the tax charge against him.

The same morning government agents also interviewed an associate of Mr. Chen’s seeking to confirm their suspicions that Mr. Chen had sought to use Chinese government awards known as talent plans in setting up a thermal energy storage company in China.

The associate instead told investigators that they didn’t ultimately pursue the company, that she didn’t believe Mr. Chen had ever been a member of a Chinese talent plan and that he “seemed very cautious about any collaboration in China,” according to documents reviewed by the Journal.

Prosecutors didn’t believe any of the interviews would undercut their case, according to a person familiar with the investigation. But they continued to hit other speed bumps. In March, a senior contract administrator at MIT told prosecutors she had worked in grant administration for decades, served as the university’s Energy Department liaison and had reviewed Mr. Chen’s grant application at issue in the case.

Upon questioning, the administrator said she didn’t believe Energy Department applications in 2017 required the disclosure of activities with foreign governments. In 2020, the department started asking researchers for more information about a range of potential conflicts of interest, including foreign-government funding.

The government had also identified papers co-authored by Mr. Chen, in which he cited his Energy Department grant funding and other authors cited Chinese government grants, as a potential undisclosed collaboration involving foreign-government funded research.

But a primary author of one of the papers, a professor at North Carolina State University, told investigators Mr. Chen’s name was included on it only because he had reviewed an earlier draft and offered helpful feedback, the professor, Jun Liu, said.

The case’s deathblow came in January, when the Energy Department official told prosecutors the agency didn’t believe Mr. Chen’s foreign positions would have mattered in 2017. Other Energy Department officials had indicated otherwise before Mr. Chen’s arrest.

“We always believed in Gang’s innocence, so the strategy was to attack the government’s case from both a factual and legal basis. While no one should have to experience what Gang and his family suffered through this past year, I appreciate that the government finally recognized that the evidence did not support the charges,” said Mr. Chen’s attorney, Rob Fisher.

On the day of the dismissal, the U.S. attorney in Boston, Rachael Rollins, said: “Our office has concluded that we can no longer meet our burden of proof at trial. As prosecutors, we have an obligation in every matter we pursue to continually examine the facts while being open to receiving and uncovering new information.”

During the past year, Mr. Chen, who studies how heat moves through solid materials, said he spent time reviewing research on how heat moves in liquids, an area he said he plans to spend more time studying now.

“This time, actually, in some ways, has been beneficial for me in terms of being able to make that shift,” he said, adding: “I was joking, if I study water, nobody will think I am doing secret research.”

Harvard Chemical Biology Department,Harvard Chemical Biology Department,Harvard Chemical Biology Department,Harvard Chemical Biology Department,Harvard Chemical Biology Department,Harvard Chemical Biology Department,Harvard Chemical Biology Department,Harvard Chemical Biology Department,

Related Articles:

CIA Has Had Keys To Global Communication Encryption Since WWII

Hostile Spies Target U.S. With Cyber, Encryption, Big Data, Report Finds

Hackers Stole And Encrypted Data of 5 U.S. Law Firms, Demand 2 Crypto Ransoms

Ex-CIA Engineer Goes On Trial For Massive Leak

Multi One Password (Portable App)

After He Fell For A $40K Phone Scam, His Bank Offered To Help—If He Stayed Quiet (#GotBitcoin?)

Your PGP Key? Make Sure It’s Up To Date

Bezos’ Phone Allegedly Hacked By Account Associated With Crown Prince

Major Companies Shared Vulnerability Used In Travelex Cyberattack (#GotBitcoin?)

Microsoft Releases Patch To Patch Windows Flaw Detected By NSA

VPN Tier List 2020 (Comparison Table)

SEC Market-Surveillance Project Hits Snag Over Hacker Fears

Inside China’s Major US Corporate Hack

Twitter Bug Exposed Millions of User Phone Numbers

U.S. Cyber Officials Give Holiday Shopping Advice For Consumers

Is Cayla The Toy Doll A Domestic Spy?

Google’s “Project Nightingale” Faces Government Inquiry Over Patient Privacy.

Which Password Managers Have Been Hacked?

DNS Over HTTPS Increases User Privacy And Security By Preventing Eavesdropping And Manipulation

Russia Steps Up Efforts To Shield Its Hackers From Extradition To U.S.

Barr Revives Debate Over ‘Warrant-Proof’ Encryption (#GotBitcoin?)

Should Consumers Be Able To Sell Their Own Personal Data?

Doordash Says Security Breach Affected Millions Of People (#GotBitcoin?)

Fraudsters Used AI To Mimic CEO’s Voice In Unusual Cybercrime Case (#GotBitcoin?)

Pearson Hack Exposed Details on Thousands of U.S. Students (#GotBitcoin?)

Cyber Hack Got Access To Over 700,000 IRS Accounts (#GotBitcoin?)

Take A Road Trip With Hotel Hackers (#GotBitcoin?)

Hackers Target Loyalty Rewards Programs (#GotBitcoin?)

Taxpayer Money Finances IRS “Star Trek” Parody (#GotBitcoin?)

IRS Fails To Prevent $1.6 Billion In Tax Identity Theft (#GotBitcoin?)

IRS Workers Who Failed To Pay Taxes Got Bonuses (#GotBitcoin?)

Trump DOJ Declines To Charge Lois Lerner In IRS Scandal (#GotBitcoin?)

DMV Hacked! Your Personal Records Are Now Being Transmitted To Croatia (#GotBitcoin?)

Poor Cyber Practices Plague The Pentagon (#GotBitcoin?)

Tensions Flare As Hackers Root Out Flaws In Voting Machines (#GotBitcoin?)

Overseas Traders Face Charges For Hacking SEC’s Public Filings Site (#GotBitcoin?)

Group Hacks FBI Websites, Posts Personal Info On Agents. Trump Can’t Protect You! (#GotBitcoin?)

SEC Hack Proves Bitcoin Has Better Data Security (#GotBitcoin?)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.