Is This A Liquidity Crisis Or A Solvency Crisis? It Matters To Fed (#GotBitcoin?)

If central bank is too concerned about getting its money back, it may shun weaker companies. Is This A Liquidity Crisis Or A Solvency Crisis? It Matters To Fed (#GotBitcoin?)

Is the economy facing a liquidity crisis, or a solvency crisis? The distinction will determine how important the Federal Reserve is to returning the economy to health.

In a liquidity crisis, otherwise healthy firms collapse because they can’t access credit. The Fed can resolve such a crisis because it can print and lend unlimited amounts of money. In a solvency crisis, companies can’t survive no matter how much they can borrow: they need more revenue. The Fed can’t solve that.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell underlined the distinction Wednesday. The central bank had directed aid to sectors “where we have never been before and…quite aggressively,” he said at a news conference after the central bank’s policy meeting.

“Nonetheless these are lending powers. We can’t lend to insolvent companies. We can’t make grants.”

Is that lending enough to save the economy? The stock market seems to think so. The S&P 500 Index is down just 13% from its pre-pandemic level. By preventing illiquid companies from going bankrupt, the market seems to believe the Fed has set the stage for a brisk economic recovery once the coronavirus pandemic eases.

Investors may have conferred more power on the Fed than the Fed believes it has. Mr. Powell urged Congress to appropriate more money to aid potentially insolvent firms and the unemployed. “This is the time to use the great fiscal power of the United States to do what we can to support the economy,” he said.

The Fed was created to deal with one specific type of liquidity crisis: runs on banks. A bank in need of cash to meet deposit withdrawals could borrow from the Fed. In the 2008 global financial crisis, the Fed made itself “lender of last resort” to a much wider range of financial institutions and markets. It made money on those loans, which shows the recipients were, in fact, solvent.

In 2012, the European Central Bank’s then-president Mario Draghi provided history’s most vivid demonstration of central bank power by promising to do “whatever it takes” to save the euro. Investors correctly inferred that meant lending to heavily indebted countries such as Italy and Spain, which were being locked out of bond markets. Investors quickly resumed buying Spanish and Italian debt, before the ECB had spent a penny.

The Fed’s response to the coronavirus pandemic has been similar. When yields on Treasurys and mortgage-backed bonds spiked, the Fed brought them down with a flood of buying. When investors started to shun corporate debt, the Fed promised to buy it through special programs backstopped by the Treasury department. The spread on yields between investment-grade corporate bonds and Treasurys has since shrunk by about half, without the Fed buying any corporate bonds.

“It’s not just the actual lending we do,” Mr. Powell explained. “We build confidence in the market, and private market participants come in, and many companies that would have had to come to the Fed have now been able to finance themselves privately.”

Still, the companies able to issue bonds are those that are widely seen as solvent. A much bigger challenge looms: the many companies that were profitable before the pandemic and should be again when the pandemic has passed, but may not survive that long. Providing them with cash should pay economic dividends in terms of protecting jobs and incomes, but such a move is complicated by the question of whether the firms are illiquid or insolvent.

For small business, Congress chose to ignore the distinction by offering $660 billion in loans that don’t have to be repaid if they meet certain conditions. By contrast, the Fed’s Main Street loans, to which $600 billion has been allotted, are supposed to be repaid. If the Fed is too concerned about getting the money back, it may shun the weaker companies where the money will make the biggest difference. Congress provided the Fed with $454 billion of capital, presumably to make it easier to make potentially money-losing loans. Asked how much risk the Fed was willing to take with that money, Mr. Powell demurred: “That is really a question for the Treasury.”

Difference Between Liquidity Crisis And Solvency Crisis

What Is The Difference Between A Liquidity Issue And Solvency Issue?

A liquidity issue (crisis) occurs when a firm (or country) has a temporary cash flow problem. Its assets are greater than its debts, but some assets are illiquid (e.g. it takes a long time to sell a house. A bank can’t suddenly demand a mortgage loan back) Therefore, although in theory assets are greater than debts, it can’t meet its current payment requirements.

* A solvency crisis occurs when a country has debts that it can’t meet through its assets. i.e. even if it could sell all its assets, it would still be unable to repay its debts.

* To be insolvent is much more serious because even if you have access to temporary funds it can’t solve the underlying problem of excess debts.

Definition Of Liquidity: Capable Of Covering Current Liabilities Quickly With Current Assets

Definition Of Solvency: Ability Of A Business To Have Enough Assets To Cover Its Liabilities

Example of Solvency Crisis

When Lehman Brothers went under, its debts (liabilities) were much greater than its assets. Therefore, even though it had access to temporary funds from the Federal Reserve, this access to liquidity couldn’t solve the underlying problem that it couldn’t meet its liabilities.

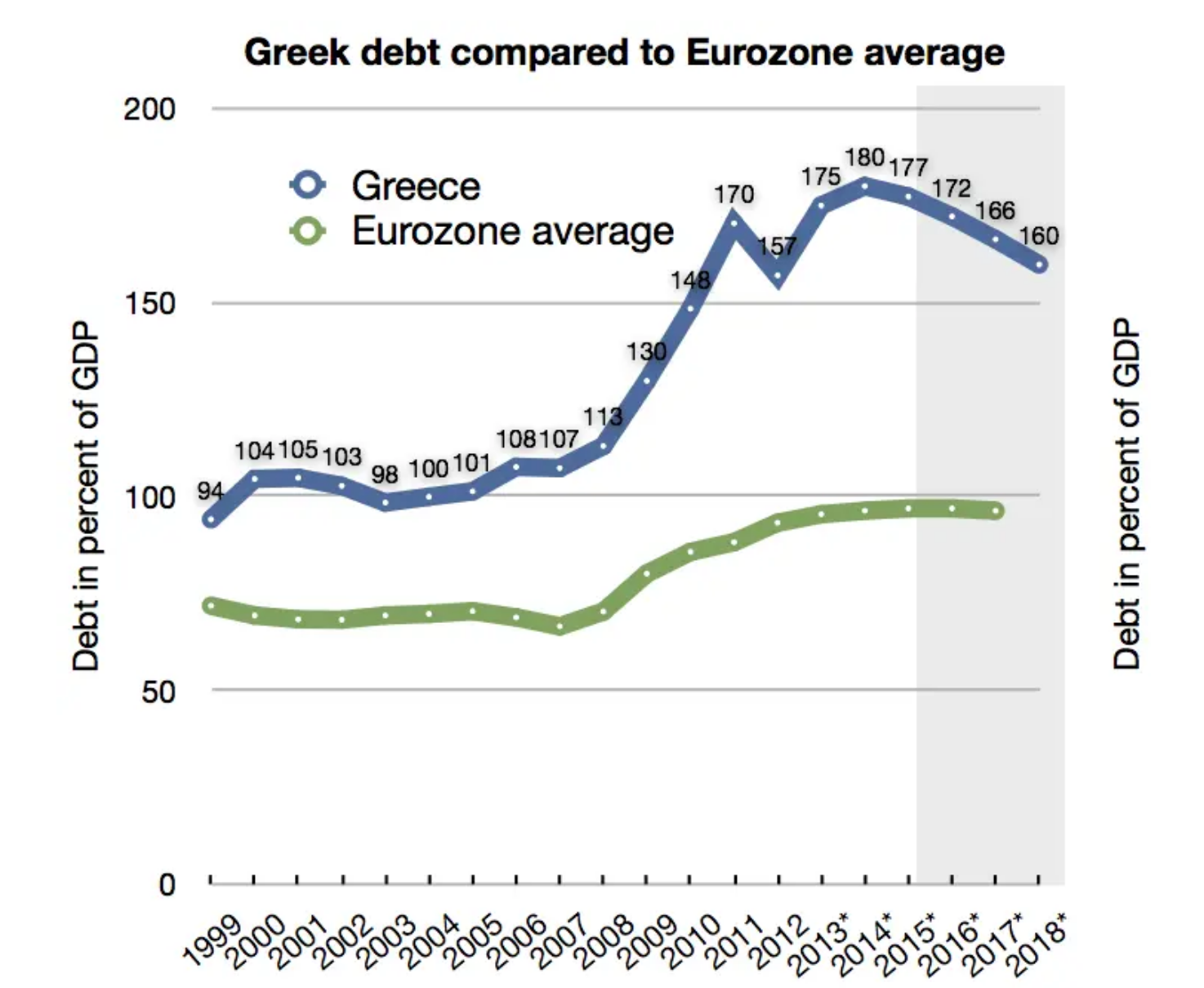

Example of Greece – Insolvency

Arguably, the debt Greece faces means that it is insolvent. It’s debt to GDP is so large that there is little chance Greece could pay off its debts from current tax revenue. Therefore, it will have to default on at least part of its debt and receive bailout funds.

Another example could be a country which faces a liquidity crisis. For example, suppose a country in the Eurozone has debt to GDP ratio of around 60%. With positive economic growth, this kind of debt should be manageable; they should be able to pay it off.

However, if there was a fall in confidence in bond markets, one month the country may be unable to sell sufficient bonds. The country might have some illiquid assets (e.g. islands, national treasures it could sell) but the problem is that in the short term, it can’t gain sufficient finance to meet its current expenditure. Therefore, it is experiencing liquidity issues.

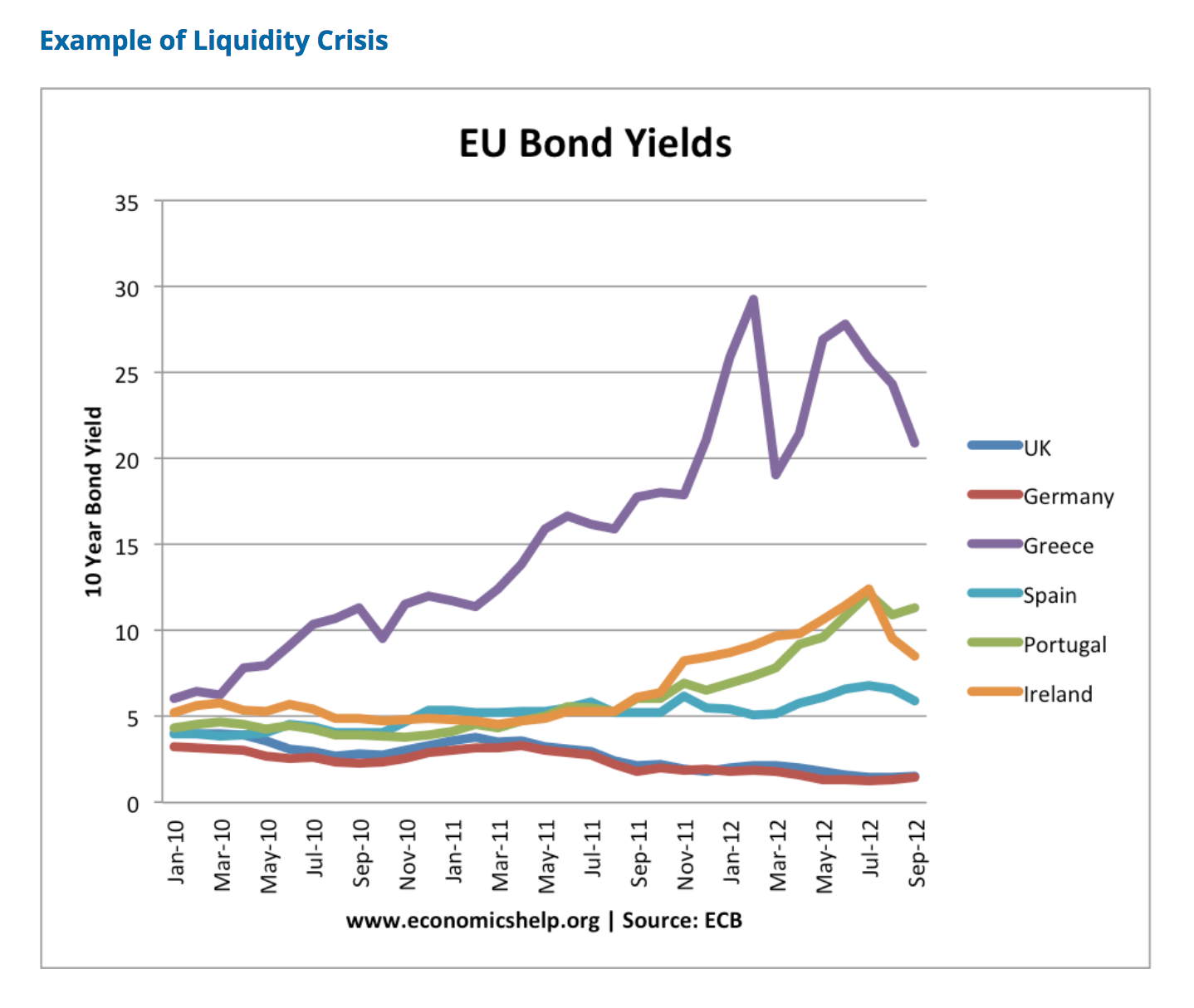

In 2012, there was a crisis of confidence in the Eurozone. It started with evidence Greece was insolvent. Investors no longer wanted to hold Greek bonds and so the yield on bonds rose rapidly – getting close to 30% – indicating it was seen as ‘junk bond’ with little hope of getting money back.

Because of uncertainties over Greece and recession in rest of Eurozone investors became nervous of holding debt in other Eurozone economies, such as Ireland, Portugal and Spain. These countries were not insolvent, but they had no Central Bank to print money and buy bonds.

Central Bank Can Provide Liquidity

A country like the UK can easily avoid liquidity issues by having a Central Bank who is willing to print money and buy bonds where necessary. This means that if the UK sold insufficient bonds one month, the Central Bank could intervene to provide liquidity.

A Central Bank can help avoid temporary liquidity shortages, but it wouldn’t be a solution if debt levels were fundamentally unsustainable and the country was insolvent.

For example, in 2008, the Zimbabwe economy was bankrupt by falling demand and shortages of goods. In response, the government printed more money – but this only caused hyperinflation and did not solve the fundamental problem

Liquidity crisis can cause solvency issues

Arguably, if countries face liquidity shortages (e.g. no access to liquidity in the Eurozone because there is no Central Bank to buy bonds) this could lead to solvency issues in the long term. Because markets fear illiquidity, bond yields rise. This causes:

Higher interest payments making it harder to repay actual debt.

It also forces governments into austerity measures which lead to lower growth and can make it very difficult to achieve a positive rate of growth and repay the debt in the long-term.

Therefore access to liquidity can help, but it can’t solve a fundamental situation of insolvency.

Updated: 5-10-2020

Speaking of Insolvent…..

A Nation of Zombie Borrowers Isn’t Inevitable—Even With More Debt

Governments and central banks are correct in trying to extend credit to companies that were already loaded up.

Can you cure a debt problem with more debt?

Governments and central banks everywhere are in the process of trying to do exactly that: extend more credit to companies that were already loaded up with plenty of it. With some caveats, they are right to do so—and truly radical action being tested in Europe could overcome even these drawbacks.

This sounds like it makes no sense. Put simply, a company that generates less cash than it has to pay in interest is bust, and adding more debt means adding on still more interest. If a company can’t repay a loan when it matures, it is also bust, and more debt means a bigger amount to repay at the end.

There are three ways new lending can fix this, and all are being used: refinancing at a lower rate, deferring interest to repay in the future and extending debt or making it easier to get a replacement loan at maturity. The caveats are that more debt makes the entire economy more at risk from any rise in interest rates, and that companies might be saved only to turn into the living dead—zombies forced to use all their cash to service their debt.

Lower rates help immediately by reducing interest costs and come from a mix of direct Federal Reserve rate cuts, discounted lending directly to companies by both government agencies and the Fed, and the Fed’s planned purchase of corporate bonds, bringing yields back down.

Many banks are offering deferral of interest on credit cards, car loans and some small-business loans (along with some government-backed business loans). The interest still has to be paid, but not for several months, when, one hopes, the economy will be improving again. It’s harder in the corporate bond market, where only a handful of issuers gave themselves an option to roll up the interest and pay it at maturity. Such a “payment-in-kind toggle” was included in only $4.2 billion of new bonds last year, according to Dealogic. The rest need to renegotiate terms or turn to the government for support.

Finally, extending a loan is a classic tactic for a troubled business, while even healthy companies can rarely afford to pay off all their debt when it matures. This is one reason the Fed is intervening so aggressively to keep the corporate bond market open, as an inability to repay old debt with new debt would force large numbers of solid companies into the bankruptcy courts.

All of this helps keep companies alive. And lower rates do even more, turning Fed liquidity into corporate solvency: The interest savings translate into higher profits and so a stronger balance sheet for the troubled company.

The danger is zombies. Lower rates enough, and you might animate a dead company—but not so much that it’s actually alive. The result is a company using all its cash to pay interest. It will merely limp along, unable to invest for the future or ever repay its debts.

Zombification is a real risk, not just now but in any effort to save a company by cutting rates. Advocates of creative destruction argue it would be better to let the zombies die and reallocate their workers and capital to more-productive uses.

It is true that creative destruction is capitalism at its best—in normal times. These are not normal times. Allowing companies to limp along holds out the hope that when the coronavirus pandemic recedes their revenues will improve and they will be revivified, albeit with weaker growth prospects than before they were loaded down with debt. Frankly, we all have to get used to that after months of economic collapse.

Not every zombie can be saved. The retailer Neiman Marcus was already close to being one of the walking dead before its bankruptcy filing, loaded down with debt that consumed most of its income. It has only been a year since it restructured its debt to gain breathing space for a planned three-year recovery, strangled by the lockdown.

Undoubtedly all the new debt will create new zombies, which will eventually have to be dealt with. But spreading out corporate failures over time is better than having them all at once, because the economy can better reallocate resources when it is growing. The sudden shock of a mass of bankruptcies all at once would hammer demand and risk a downward spiral into depression. Banks are being encouraged to “extend and pretend”—giving borrowers more time to pay and pretending they are still creditworthy—precisely to avoid adding another shock to a struggling economy.

Central banks can go further. Lower rates improve the profits (or reduce the losses) of borrowers, but negative rates transfer money from savers to borrowers. So far only a few of the best-rated companies in Europe, the region with the lowest rates, can borrow at below zero, but the European Central Bank is already experimenting with the next step: borrowing rates lower than deposit rates.

For now the gap is small, with the ECB’s best borrowing rate under new term loans to banks being minus 1%, for those that meet certain conditions, compared with a deposit rate of minus 0.5%. It isn’t nothing: Italian banks’ profits will get a 10% boost from the rate inversion, according to Frederik Ducrozet, a global strategist at Pictet Wealth Management. A widened gap would help banks more, and if the ECB insisted on the lower borrowing rates being passed on it could help nonbank borrowers too. Liquidity would be transformed directly into solvency.

The danger is that central banks handing out money doesn’t just cure the zombies, but creates inflation. That’s not a problem for now, and as M&G fund manager Eric Lonergan says, it is easy to fix: “If by a miracle we do too much, it’s not a problem: you just raise taxes.”

Updated: 5-9-2021

What Happens To Stocks And Cryptocurrencies When The Fed Stops Raining Money?

An unprecedented fiscal and monetary stimulus led by the Federal Reserve is fueling a new investor euphoria. Is this a new bubble? And when could it burst?

To veterans of financial bubbles, there is plenty familiar about the present. Stock valuations are their richest since the dot-com bubble in 2000. Home prices are back to their pre-financial crisis peak. Risky companies can borrow at the lowest rates on record. Individual investors are pouring money into green energy and cryptocurrency.

This boom has some legitimate explanations, from the advances in digital commerce to fiscally greased growth that will likely be the strongest since 1983.

But there is one driver above all: the Federal Reserve. Easy monetary policy has regularly fueled financial booms, and it is exceptionally easy now. The Fed has kept interest rates near zero for the past year and signaled rates won’t change for at least two more years. It is buying hundreds of billions of dollars of bonds. As a result, the 10-year Treasury bond yield is well below inflation—that is, real yields are deeply negative —for only the second time in 40 years.

There are good reasons why rates are so low. The Fed acted in response to a pandemic that at its most intense threatened even more damage than the 2007-09 financial crisis. Yet in great part thanks to the Fed and Congress, which has passed some $5 trillion in fiscal stimulus, this recovery looks much healthier than the last. That could undermine the reasons for such low rates, threatening the underpinnings of market valuations.

“Equity markets at a minimum are priced to perfection on the assumption rates will be low for a long time,” said Harvard University economist Jeremy Stein, who served as a Fed governor alongside now-chairman Jerome Powell. “And certainly you get the sense the Fed is trying really hard to say, ‘Everything is fine, we’re in no rush to raise rates.’ But while I don’t think we’re headed for sustained high inflation it’s completely possible we’ll have several quarters of hot readings on inflation.”

Since stocks’ valuations are only justified if interest rates stay extremely low, how do they reprice if the Fed has to tighten monetary policy to combat inflation and bond yields rise one to 1.5 percentage points, he asked. “You could get a serious correction in asset prices.”

‘A Bit Frothy’

The Fed has been here before. In the late 1990s its willingness to cut rates in response to the Asian financial crisis and the near collapse of the hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management was seen by some as an implicit market backstop, inflating the ensuing dot-com bubble. Its low-rate policy in the wake of that collapsed bubble was then blamed for driving up housing prices.

Both times Fed officials defended their policy, arguing that to raise rates (or not cut them) simply to prevent bubbles would compromise their main goals of low unemployment and inflation, and do more harm than letting the bubble deflate on its own.

As for this year, in a report this week the central bank warned asset “valuations are generally high” and “vulnerable to significant declines should investor risk appetite fall, progress on containing the virus disappoint, or the recovery stall.” On April 28 Mr. Powell acknowledged markets look “a bit frothy” and the Fed might be one of the reasons: “I won’t say it has nothing to do with monetary policy, but it has a tremendous amount to do with vaccination and reopening of the economy.”

But he gave no hint the Fed was about to dial back its stimulus: “The economy is a long way from our goals.” A Labor Department report Friday showing that far fewer jobs were created in April than Wall Street expected underlined that.

The Fed’s choices are heavily influenced by the financial crisis. While the Fed cut rates to near zero and bought bonds then as well, it was battling powerful headwinds as households, banks, and governments sought to pay down debts. That held back spending and pushed inflation below the Fed’s 2% target. Deeper-seated forces such as aging populations also held down growth and interest rates, a combination some dubbed “secular stagnation.”

The pandemic shutdown a year ago triggered a hit to economic output that was initially worse than the financial crisis. But after two months, economic activity began to recover as restrictions eased and businesses adapted to social distancing. The Fed initiated new lending programs and Congress passed the $2.2 trillion Cares Act. Vaccines arrived sooner than expected. The U.S. economy is likely to hit its pre-pandemic size in the current quarter, two years faster than after the financial crisis.

And yet even as the outlook has improved, the fiscal and monetary taps remain wide open. Democrats first proposed an additional $3 trillion in stimulus last May when output was expected to fall 6% last year. It actually fell less than half that, but Democrats, after winning both the White House and Congress, pressed ahead with the same size stimulus.

The Fed began buying bonds in March, 2020 to counter chaotic conditions in markets. In late summer, with markets functioning normally, it extended the program while tilting the rationale toward keeping bond yields low.

At the same time it unveiled a new framework: After years of inflation running below 2%, it would aim to push inflation not just back to 2% but higher, so that over time average and expected inflation would both stabilize at 2%.

To that end, it promised not to raise rates until full employment had been restored and inflation was 2% and headed higher. Officials predicted that would not happen before 2024 and have since stuck to that guidance despite a significantly improving outlook.

Running Of The Bulls

This injection of unprecedented monetary and fiscal stimulus into an economy already rebounding thanks to vaccinations is why Wall Street strategists are their most bullish on stocks since before the last financial crisis, according to a survey by Bank of America Corp. While profit forecasts have risen briskly, stocks have risen more.

The S&P 500 stock index now trades at about 22 times the coming year’s profits, according to FactSet, a level only exceeded at the peak of the dot-com boom in 2000.

Other asset markets are similarly stretched. Investors are willing to buy the bonds of junk-rated companies at the lowest yields since at least 1995, and the narrowest spread above safe Treasurys since 2007, according to Bloomberg Barclays data. Residential and commercial property prices, adjusted for inflation, are around the peak reached in 2006.

Stock and property valuations are more justifiable today than in 2000 or in 2006 because the returns on riskless Treasury bonds are so much lower. In that sense, the Fed’s policies are working precisely as intended: improving both the economic outlook, which is good for profits, housing demand, and corporate creditworthiness; and the appetite for risk.

Nonetheless, low rates are no longer sufficient to justify some asset valuations. Instead, bulls invoke alternative metrics.

Bank of America recently noted companies with relatively low carbon emissions and higher water efficiency earn higher valuations. These valuations aren’t the result of superior cash flow or profit prospects, but a tidal wave of funds invested according to environmental, social and governance, or ESG, criteria.

Conventional valuation is also useless for cryptocurrencies which earn no interest, rent or dividends.

Instead, advocates claim digital currencies will displace the fiat currencies issued by central banks as a transaction medium and store of value. “Crypto has the potential to be as revolutionary and widely adopted as the internet,” claims the prospectus of the initial public offering of crypto exchange Coinbase Global Inc., in language reminiscent of internet-related IPOs more than two decades earlier.

Cryptocurrencies as of May 7 were worth $2.4 trillion, according to CoinDesk, an information service, more than all U.S. dollars in circulation.

Financial innovation is also at work, as it has been in past financial booms. Portfolio insurance, a strategy designed to hedge against market losses, amplified selling during the 1987 stock market crash.

In the 1990s, internet stockbrokers fueled tech stocks and in the 2000s, subprime mortgage derivatives helped finance housing. The equivalent today are zero commission brokers such as Robinhood Markets Inc., fractional ownership and social media, all of which have empowered individual investors.

Such investors increasingly influence the overall market’s direction, according to a recent report by the Bank for International Settlements, a consortium of the world’s central banks. It found, for example, that since 2017 trading volume in exchange-traded funds that track the S&P 500, a favorite of institutional investors, has flattened while the volume in its component stocks, which individual investors prefer, has climbed.

Individuals, it noted, are more likely to buy a company’s shares for reasons unrelated to its underlying business—because, for example, its name is similar to another stock that is on the rise.

While such speculation is often blamed on the Fed, drawing a direct line is difficult. Not so with fiscal stimulus. Jim Bianco, the head of financial research firm Bianco Research, said flows into exchange-traded funds and mutual funds jumped in March as the Treasury distributed $1,400 stimulus checks. “The first thing you do with your check is deposit it in your account and in 2021 that’s your brokerage account,” said Mr. Bianco.

Facing The Future

It’s impossible to predict how, or even whether, this all ends. It doesn’t have to: High-priced stocks could eventually earn the profits necessary to justify today’s valuations, especially with the economy’s current head of steam. In the meantime, more extreme pockets of speculation may collapse under their own weight as profits disappoint or competition emerges.

Bitcoin once threatened to displace the dollar; now numerous competitors purport to do the same. Tesla Inc. was once about the only stock you could buy to bet on electric vehicles; now there is China’s NIO Inc., Nikola Corp. , and Fisker Inc., not to mention established manufacturers such as Volkswagen AG and General Motors Co. that are rolling out ever more electric models.

But for assets across the board to fall would likely involve some sort of macroeconomic event, such as a recession, financial crisis, or inflation.

The Fed report this past week said the virus remains the biggest threat to the economy and thus the financial system. April’s jobs disappointment was a reminder of how unsettled the economic outlook remains. Still, with the virus in retreat, a recession seems unlikely now. A financial crisis linked to some hidden fragility can’t be ruled out. Still, banks have so much capital and mortgage underwriting is so tight that something similar to the 2007-09 financial crisis, which began with defaulting mortgages, seems remote.

If junk bonds, cryptocoins or tech stocks are bought primarily with borrowed money, a plunge in their values could precipitate a wave of forced selling, bankruptcies and potentially a crisis. But that doesn’t seem to have happened. The recent collapse of Archegos Capital Management from reversals on derivatives-based stock investments inflicted losses on its lenders. But it didn’t threaten their survival or trigger contagion to similarly situated firms.

“Where’s the second Archegos?” said Mr. Bianco. “There hasn’t been one yet.”

That leaves inflation. Fear of inflation is widespread now with shortages of semiconductors, lumber, and workers all putting upward pressure on prices and costs. Most forecasters, and the Fed, think those pressures will ease once the economy has reopened and normal spending patterns resume.

Nonetheless, the difference between yields on regular and inflation-indexed bond yields suggest investors are expecting inflation in coming years to average about 2.5%. That is hardly a repeat of the 1970s, and compatible with the Fed’s new goal of average 2% inflation over the long term. Nonetheless, it would be a clear break from the sub-2% range of the last decade.

Slightly higher inflation would result in the Fed setting short-term interest rates also slightly higher, which need not hurt stock valuations. More worrisome: Long-term bond yields, which are critical to stock values, might rise significantly more. Since the late 1990s, bond and stock prices have tended to move in opposite directions. That is because when inflation isn’t a concern, economic shocks tend to drive both bond yields (which move in the opposite direction to prices) and stock prices down.

Bonds thus act as an insurance policy against losses on stocks, for which investors are willing to accept lower yields. If inflation becomes a problem again, then bonds lose that insurance value and their yields will rise. In recent months that stock-bond correlation, in place for most of the last few decades, began to disappear, said Brian Sack, a former Fed economist who is now with hedge fund D.E. Shaw & Co. LP. He attributes that, in part, to inflation concerns.

The many years since inflation dominated the financial landscape have led investors to price assets as if inflation never will have that sway again. They may be right. But if the unprecedented combination of monetary and fiscal stimulus succeeds in jolting the economy out of the last decade’s pattern, that complacency could prove quite costly.

Is This A Liquidity,Is This A Liquidity,Is This A Liquidity,Is This A Liquidity,Is This A Liquidity,Is This A Liquidity,

Go back

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.