The Pin That Burst Facebook And Google Online Ads Business Bubble

The dispute comes amid upheaval in the online-ad world because of the coronavirus pandemic. The Pin That Burst Facebook And Google Online Ads Business Bubble

A major contraction in ad spending threatens the revenue of all companies that sell digital ads, including giants like Google and Facebook Inc. Being on good terms with Madison Avenue is as important as ever.

Brand safety has become a critical issue for advertisers over the past few years after many brands discovered their ads were appearing next to objectionable social-media content, including on YouTube videos promoting racism or hate speech.

In 2017, many big brands temporarily suspended their ad spending on YouTube amid evidence that some ads were appearing alongside content considered to be objectionable. Last year, several brands suspended their ads on the site after revelations that inappropriate user comments were appearing under videos featuring underage girls.

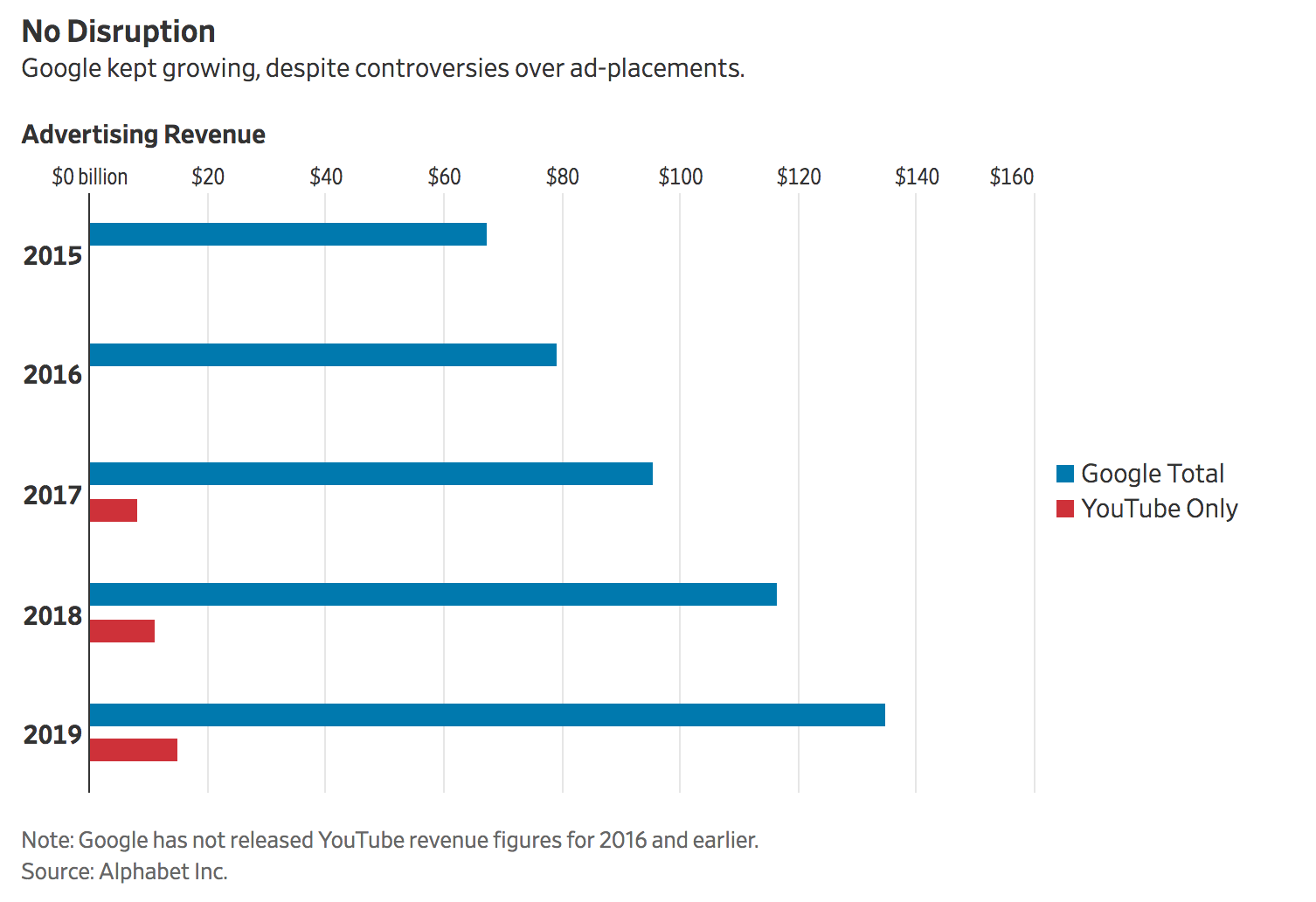

Despite the controversies, Google has remained the world’s largest advertising platform. It is expected to have a roughly 30% share of the $369 billion world-wide digital ad market this year, according to research firm eMarketer. YouTube had $15.1 billion in ad revenue for 2019.

YouTube has taken steps to assuage marketers’ concerns, including improving the technology it uses to screen videos and by allowing third-party measurement companies to monitor where ads appear on the site.

Advertisers have become dependent on these so-called brand safety firms, like OpenSlate, not only to avoid placing ads next to controversial content but also to make sure they are spending their money wisely. For example, advertisers that are trying to target adults would want to make sure that their ads avoid running on children’s content.

Under the terms Google proposed to OpenSlate, the types of information OpenSlate would be allowed to share remain unclear.

In its email, OpenSlate assured ad agencies that even if it isn’t included in the new measurement program, it will still be able to measure and score a large amount of YouTube content because it uses public data about the more than 700 million videos appearing on YouTube.

However, OpenSlate might not be able to analyze Google Preferred, YouTube’s curated lineup of top content that brands pay a premium to advertise on, since Google shares that list with approved partners.

Facebook Ad Rates Fall As Coronavirus Undermines Ad Spending

YouTube Spars With Auditor Over Transparency of Advertising Risks

OpenSlate has declined to sign a Google contract it believes bars sharing of information on hate speech, profanity and violence.

Google wants to substantially limit the information a key auditor of YouTube can share about the risks of advertising on the video service, according to people familiar with the situation, highlighting tensions between the tech giant and Madison Avenue.

The auditor, New York-based OpenSlate, is refusing to sign a contract that would prevent it from reporting to clients when ads have run in videos with sensitive subject matter, including hate speech, adult content, children’s content, profanity, violence and illegal substances, according to an email the firm sent over the weekend to ad agencies.

Under the terms Google proposed, OpenSlate would need approval from Google to share certain metrics about YouTube’s content, one of the people familiar with the situation said.

OpenSlate works with leading brands and ad agencies, like McDonald’s Corp., Pfizer Inc., Unilever PLC and WPP PLC, providing them with information to confirm that their ads on YouTube are appearing alongside content that marketers deem safe.

In the email to ad agencies, which was reviewed by The Wall Street Journal, OpenSlate said it hasn’t been able to reach an agreement with Google to be included in a new, updated version of YouTube’s ad-measurement program.

“The terms of this program would severely limit OpenSlate’s ability to deliver transparency to clients,” the firm said in the email. The firm also said in the email that it remains open to an agreement that doesn’t include such restrictions.

Alphabet Inc.’s Google said in a statement, “Our brand safety partners are always able to share their independent reporting with clients.” Google said OpenSlate isn’t currently among its official brand-safety partners. The company didn’t comment specifically on whether it has proposed restrictions for OpenSlate in any categories of content, citing contractual confidentiality obligations during active negotiations.

Google said it is expanding the number of measurement companies it works with, including brand-safety firms, changes expected to be made public Monday. “We know how important it is for our industry to have a healthy third party ecosystem of trusted independent solutions for driving and measuring marketing performance on YouTube,” the company said.

Google said it has invited OpenSlate to participate in its expanded program.

It is unclear if the partners for the newly-expanded program will face the same restrictions Google proposed to OpenSlate.

“We are able to freely report across the suite of services we offer, including viewability and invalid traffic, as well as brand safety and brand suitability,” Integral Ad Science Inc., one of Google’s approved brand-safety partners, said.

Another such partner, DoubleVerify Inc., said it “delivers transparent, unrestricted reporting across the entirety of its measurement solutions,” according to a statement.

Updated: 5-8-2020

As YouTube Traffic Soars, YouTubers Say Pay Is Plummeting

Advertising rates on the platform have dropped significantly during the coronavirus pandemic.

Newspapers, websites, and TV channels have all been decimated by the coronavirus. And YouTubers are also feeling the pinch.

While boredom-inducing stay-at-home orders may be good for YouTube channel traffic, increasing by 15%, according to the New York Times, YouTubers say that the rates companies pay to advertise on their videos are dropping significantly. That means that despite increased audiences, some YouTubers are making less money.

Carlos Pacheco, a former media buyer turned YouTube adviser, says that across 180 YouTube channels he works with — which have a total of nearly 68 million subscribers worldwide across a range of different interests — advertising rates have tanked by an average of nearly 50% since the start of February.

“Everyone is pausing their campaigns on YouTube,” Pacheco says.

Data from the Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB), an advertising industry body, suggests that one in four media buyers and brands have paused all advertising for the first half of 2020, and a further 46% have adjusted their spending downwards.

Three-quarters say the coronavirus will be more damaging for the ad industry than the 2008–’09 financial crisis. That means fewer ads for Big Macs on TV and in newspapers, but it also means advertisers are less likely to compete for the pre-roll ads that usher you toward your next YouTube video.

Digital ad spending is down by a third, according to the IAB — a slightly less painful drop than the traditional media’s 39% cut, but still damaging. YouTubers are reporting anywhere from 30% to 50% declines in their cost per mille (CPM), or the amount YouTube receives for every 1,000 views of an advertisement served against a video. YouTube takes that money, keeps 45% for itself, and gives 55% to creators.

Roberto Blake, a YouTuber who also advertises his social media consultancy business through social media ads, says he has seen a 10% drop in his CPMs, to around $20. But, he says, other YouTubers have it worse. “People I know are going down from $8 to $5.50. I’m seeing people go down from $12 to $4.”

Those calculations are based on advertisers and their budgets.

If you’re a food-based channel focused on finding the world’s best street food in the planet’s farthest-flung corners, you might rely on tourist boards, airline companies, and restaurants to advertise against your videos. But when the restaurants are closed, the airplanes are grounded, and the tourism industry in all practicality doesn’t exist, there’s no reason for anyone in the chain to spend money advertising.

While the entire industry is becoming parsimonious with their spending, some areas are affected less than others: You still need groceries, and given you’re likely working from home, office supply companies may be keen to market to customers.

“Everyone is pausing their campaigns on YouTube.”

Video game content received 13% more views across five key markets in Europe in the last month compared to the same time in 2019, according to data collated by Tubular Labs, a video intelligence company.

Though CPMs for video game content have also taken a hit, it’s a glancing punch to their finances rather than a knockout blow. “They’re dropping,” admits Pacheco, “but just not dropping as much as other channels.”

Hank Green is an author and one half of the Vlogbrothers YouTube channel, which has 3.3 million subscribers. He also runs a suite of different educational channels, including Crash Course and SciShow, which combined have tens of millions of subscribers. Even he’s not immune to the impact of falling CPMs: He said in a tweet in late March that while views across the multiple channels he runs were up by around 5%, CPMs dropped by 30%. Another creator, who uploads drumming videos to YouTube, reported his ad income had halved.

Jason Kint, CEO of Digital Content Next, a digital content trade organization, believes that TV will hold out better than YouTube. When budgets are tight, he says, brands seek safe harbors, and while YouTube has managed to project a message of professionalism in recent years, it still has an radical, independent streak that companies shy away from. “I would expect the savvier brand advertising money to go towards trusted brands and higher quality video, including traditional TV,” he says.

Both Pacheco and Blake say that falling ad revenue hasn’t discouraged YouTubers from producing more content, who see increased traffic to the video sharing platform from people stuck at home as an opportunity to attract new followers.

“Everyone is being a little careful and tightening their belts in terms of the production side of things, but using this opportunity to gain audiences,” says Pacheco. “Think about it this way — it’s the perfect environment, where many people who wouldn’t be online consumers now are, so the audience is growing exponentially.”

But making more content unfortunately only makes the falling advertising prices fall faster. More content, says Blake, “means the bidding war for that advertising is lower. It’s cheaper to advertise, and there’s more inventory to sell it against. The market just shrunk, but more people are creating content.”

Many YouTubers, he says, are hoping that the pandemic’s impact on advertising lasts three or four months, before bouncing back. (They may be holding their breath: IAB data forecasts that advertising in the third quarter of 2020 will be 75% planned budgets, and only 88% the original planned spent in the last three months of the year.) “Anyone that makes money only off YouTube at the minute is in a very precarious place,” he says.

YouTubers have been here before. The “adpocalypse,” a 2017 scandal where advertisements were being placed against terrorist recruitment videos on the platform, caused a mass exodus of big business from YouTube. Some of the world’s biggest brands yanked their advertising budgets away from the site, hitting creators in the pocket.

The advertisers eventually returned after YouTube made sweeping changes to clean up the platform — changes which ended up irking the site’s independent creators, and making it more difficult for them to survive. In the interim, YouTubers sought income off the platform.

They diversified their revenue streams by developing and selling merchandise, building up an audience on other social networks in case their YouTube channels disappeared, and joining platforms like Patreon, where fans can directly support their favorite talent financially with a monthly stipend. Those who did diversify back then are better prepared to weather the storm now. “Anyone that has all their eggs in one basket right now is getting hammered,” reckons Pacheco.

Updated: 6-22-2020

Google’s U.S. Ad Revenue Is Expected to Decline in 2020, eMarketer Says

Research firm eMarketer says decline would be the first since it started tracking Google’s ad revenue in 2008.

Google’s U.S. advertising revenue will decline this year for the first time since eMarketer began modeling it in 2008, the research firm said, largely because Google’s core search product is so reliant on the pandemic-battered travel industry.

As the world’s largest digital-advertising company, the Alphabet Inc. GOOG +1.16% unit has heretofore been a money-printing machine, expanding its overall advertising revenue at double-digit rates in nearly every year of its two-decade existence, save for the 2008-09 financial crisis, when it only grew 8%. The firm doesn’t break out its U.S. revenue, but eMarketer’s model found that even in that crisis, Google’s U.S. ad revenue grew.

What is different this time is the way the coronavirus pandemic obliterated marketing spending in some of Google search’s biggest advertisers, and the way some of these advertisers have been public about rethinking their plans to return to the platform even after the pandemic passes.

“The biggest single culprit here is the travel industry, which has been both hardest hit by the pandemic generally, and has concentrated spending on Google in the past,” said Nicole Perrin, principal analyst at eMarketer. “We have already heard statements from major travel companies, like Expedia, that normally spend billions of dollars on Google, mostly on search, that they are pulling back spending on Google and search, and that will continue for the rest of this year.”

Travel represented about 11% of search ad revenue in 2019, Needham analyst Laura Martin estimated.

Expedia Group Inc., which owns brands such as Travelocity, Orbitz and Vrbo, has historically been one of Google search’s biggest advertisers, according to data from the advertising-research company Kantar.

On an earnings call in May, Expedia CEO Peter Kern said the pandemic offered the company an “opportunity of an entire reset” on its traditionally search-heavy advertising spending. Expedia has warned its investors that a risk for the company is the way Google has launched travel products in recent years that compete directly with its largest advertising partners, and then uses its search function to drive users to its own products.

“As we wade back in, we’re able to be more precise, be more constrained, watch and learn and grow into it, and not just dive back in head first and spend back to the levels we were at,” he said.

EMarketer also pointed to Amazon, another big search spender, pulling back its search spending sharply as the pandemic hit as it struggled to fulfill orders.

EMarketer estimates that Google’s gross U.S. advertising revenue will decline 4%, while its net U.S. revenue—accounting for the payments it makes to website owners to acquire traffic—will drop by 5% this year.

Google declined to comment.

That is still less of a drop than for the advertising market overall, which eMarketer estimates will shrink by about 7% this year.

Despite the pandemic, digital advertising continues to steadily take share from traditional media. And the “triopoly” of Google, Facebook and Amazon is sucking up an ever-greater share of digital spending.

EMarketer estimates that digital advertising will increase its share of the overall advertising market by about 5 percentage points this year, to 60% from 55%. But in absolute terms, the pie is shrinking.

The firm expects digital to grow by nearly 2%, television ad spending to decline by 15% and print to drop by 25%.

The triopoly’s share will also inch up this year, albeit at a much slower rate than before, from 62% to 62.2%. Most notable, though, is the changing face of this triopoly: Google, long the biggest player, is shrinking, while both Facebook and Amazon are growing.

While the pandemic hurt all advertising players, and eMarketer had to revise its estimates of Facebook’s performance downward like everyone else, it still expects net U.S. revenue at Facebook to grow by 5% this year to $31 billion.

“The factors that have propelled Facebook to be a digital advertising superpower in the first place are the same ones keeping advertisers spending during the pandemic: huge reach, effective targeting at scale and performance ad products that tie spending to results,” the report said.

It also helped that Facebook has less exposure to travel, and more exposure to categories that have thrived under lockdown, such as direct-to-consumer retail and gaming, eMarketer noted.

“They were pretty resilient,” Ms. Perrin said.

In recent days, civil-rights groups including the Anti-Defamation League and NAACP have called on advertisers to pull spending from Facebook for the month of July to protest the platform’s approach to policing hate speech and misinformation. Densu Group Inc.’s digital firm 360i advised clients to support the boycott. On Friday, outdoor-gear maker the North Face said it would join.

Updated: 7-2-2020

Facebook’s Tensions With Advertisers Predate The Boycott

Big marketers’ pullback is their most visible confrontation with Facebook but not the first.

In a virtual town hall with marketers and advertising agencies on Tuesday, Facebook Inc. executives once again tried to answer complaints that the company hasn’t done enough to counter hate speech and misinformation.

Led by Carolyn Everson, vice president of Facebook’s Global Business Group, executives described efforts to make the Facebook and Instagram platforms less hostile and the difficulty of moderating conversations without constraining speech, according to participants.

It was just the latest effort by Facebook to show that the social-media giant takes seriously the concerns about its policies.

But the company isn’t only confronting the challenge sparked on June 17, when several civil-rights groups called on advertisers to pull their spending as a way to pressure Facebook into changing the way it handles content. Facebook is also facing discontent from advertisers stretching back years.

“The history really helped everyone feel pretty vindicated in taking this action and being serious about it,” said Katia Beauchamp, co-founder and chief executive at beauty retailer Birchbox Inc., which joined the boycott on June 26.

That history includes the revelation in 2018 that personal data of tens of millions of Facebook users improperly wound up with data firm Cambridge Analytica, prompting government probes and calls for stricter privacy protections online.

Marketers have also criticized Facebook for the way it handles measurement on its platform and what some call a lack of commitment to brand safety—keeping their ads away from objectionable content.

A Facebook spokeswoman pointed to the company’s announcement on Monday about a new audit, run by industry watchdog Media Rating Council. It will evaluate Facebook’s content monetization and brand-safety tools and practices as part of new initiatives the company is undertaking in response to recent criticisms.

Other companies that have paused ad spending with Facebook now include Volkswagen AG, Ford Motor Co., Clorox Co., Denny’s Corp., Verizon Communications Inc., Coca-Cola Co., Unilever PLC, Levi Strauss & Co., along with smaller brands.

Some have also suspended advertising elsewhere in social media, and not all are identifying themselves with the boycott effort. More have focused directly on Facebook.

“Marketers’ dissatisfaction goes way back,” said Joy Howard, chief marketing officer at password manager Dashlane Inc., which said it won’t advertise with Facebook at least through July, the month targeted by boycott organizers.

Ms. Howard participated in an earlier, one-week boycott of Facebook advertising over Cambridge Analytica when she was chief marketing officer at Sonos Inc., she said.

At Dashlane, her team was already trying to reduce reliance on Facebook over concerns about content even before the boycott call, she said, but also because of controversy over the potential for discriminatory advertising several years ago.

Facebook said then it would no longer let marketers target housing, employment and credit-related ads by ethnic affinity. In March 2019 the company settled five discrimination lawsuits in part by also removing age, gender and ZIP Code targeting for housing, employment and credit-related ads.

Facebook is also still trying to bolster advertisers’ trust in the metrics it provides, going back to the 2016 disclosure that it had overestimated average viewing time for video ads on its platform for two years.

The Media Rating Council warned Facebook this spring that it could be denied a seal of approval that gives companies confidence they are getting what they pay for when it comes to advertising on its platforms.

The notice said that Facebook had failed to address advertiser concerns arising from a 2019 audit performed by Ernst & Young, most notably concerning how Facebook measures and reports data about video advertisements.

“These exchanges are part of the audit process,” Facebook said in May. “We will continue working with MRC on accreditation, as we have since 2016.”

Each incident has created blowback from advertisers, but Facebook has managed to continue to grow ad revenue. It reported companywide ad revenue of $69.7 billion last year, up from $55 billion in 2018 and $17.1 billion in 2015.

Facebook and Instagram’s U.S. ad revenue alone is expected to grow nearly 5% to $31.43 billion this year, according to research firm eMarketer.

Even as the list of major marketers now suspending their advertising grows, Facebook remains somewhat protected because the bulk of its revenue comes from small and midsize companies. Facebook’s top 100 advertisers comprised less than 20% of its total ad revenue in the first quarter of 2019, Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg said last year.

Many small companies and marketers that sell directly to consumers without going through retailers would suffer more than a major multinational from a Facebook boycott, said Kevin Simonson, vice president of social for digital marketing agency Wpromote LLC.

The business model of most consumer brands that sell primarily through the internet relies heavily on Facebook and Instagram, Mr. Simonson said. “So for them to pause their main source of revenue would be devastating to their business in ways that it won’t for a vast majority of the big brands participating in the boycott.”

Particularly for prominent brands, however, the current confrontation may be different than past strife because it revolves around broad ethical issues rather than concerns largely specific to the ad industry, some ad executives said.

“The difference this time is that CMOs are getting pressure from their boards, and the boards are getting pressure from the public and advocacy groups,” said an executive at a large ad-agency holding company.

Facebook said that it invests billions of dollars every year to keep its platform safe and has banned 250 white-supremacist organizations from Facebook and Instagram. Facebook’s technology finds nearly 90% of hate speech before anyone flags it, the company said.

“We know we have more work to do,” Facebook said, adding that it would continue to work with Global Alliance for Responsible Media, an ad-industry group created to improve the digital ecosystem, and others.

The fight against hate speech overlaps with a longtime business concern of marketers in the digital age: keeping their ads far from offensive content.

Verizon suspended its advertising on Facebook and Instagram after the Anti-Defamation League released a screenshot showing a Verizon ad next to a Facebook post alleging that FEMA was getting ready to put people in concentration camps. The ADL is one of the organizers of the boycott.

“We’re pausing our advertising until Facebook can create an acceptable solution that makes us comfortable and is consistent with what we’ve done with YouTube and other partners,” Verizon Chief Media Officer John Nitti said on June 25.

The Facebook spokeswoman declined to comment on Verizon’s decision.

“There’s more to it than issues of misinformation and hate speech,” an ad buyer at a major advertising agency said. “Facebook needs to invest more in keeping advertisers away from objectionable content.”

Updated: 7-2-2020

Where Advertisers Boycotting Facebook Are Spending Their Money Instead

Marketers’ plans include Gmail promotions, more influencer marketing and first-time TikTok buys.

Facebook Inc.’s sprawling reach among consumers and its powerful ad targeting abilities have made it a seeming must-buy for many marketers.

Its Facebook and Instagram platforms are likely to collect 23.4% of U.S. digital ad revenue this year, second only to Alphabet Inc.’s Google and far ahead of its next closest rival, Amazon.com Inc., according to research firm eMarketer.

But a growing list of companies are pausing their advertising with Facebook for July or longer, responding to civil-rights groups’ call for a boycott over what they say is a lack of progress in preventing hate speech and misinformation.

While the ad industry waits to see how the confrontation will play out, the boycotters have another question to answer: What is their marketing strategy without Facebook?

The alternatives sometimes don’t get enough attention because Facebook advertising is considered a safe choice, according to an ad buyer at a major advertising agency.

“Putting your next dollar into Facebook, you know it’s going to work,” the buyer said. “Whereas putting that dollar someplace else, you might not know it’s gonna work.”

Facebook on Friday said it would start labeling political speech that violated its rules and take other measures to prevent voter suppression and protect minorities from abuse.

That didn’t stop more companies from joining the boycott. The list of advertisers that say they won’t buy ads on Facebook or Instagram in July at a minimum now includes Levi Strauss & Co., Beam Suntory Inc., Hershey Co., Patagonia Inc., North Face, the U.S. sales and marketing arm of Honda Motor Co., Eddie Bauer LLC and Recreational Equipment Inc. Clorox Co. on Monday said it will cease advertising with Facebook through December.

“We invest billions of dollars each year to keep our community safe and continuously work with outside experts to review and update our policies,” a Facebook spokeswoman said Monday. “We’ve opened ourselves up to a civil-rights audit, and we have banned 250 white supremacist organizations from Facebook and Instagram.”

Facebook finds nearly 90% of the hate speech on which it takes action before users report it but will continue to work with civil-rights groups and others to do more, she said.

Some of the marketers pulling back from Facebook are now going to find out if their strategies will work out.

“We stand with the Black community and support those who are fighting for stricter policies that stop racist, violent or hateful content and misinformation from circulating on these platforms,” the VF Corp. backpack brand JanSport said Friday as it joined the boycott. “As such, we will shift the planned launch of our July back-to-school campaign to YouTube and TikTok.”

YouTube, part of Google, and video-sharing social networking service TikTok, which is owned by Bytedance Ltd., are already part of the JanSport campaign but will assume a larger role, a spokeswoman said.

Apparel brand North Face, also owned by VF, is likely to increase ad spending with current partners such as Google and Pinterest Inc., a spokeswoman said. But it is also exploring opportunities in affiliate marketing, in which websites get commissions for referring traffic to a brand, and targeting consumers elsewhere around the web, she said.

Password manager Dashlane Inc. will spend more on sponsored content, online display ads and social media platforms such as Pinterest, said Joy Howard, chief marketing officer at the company. It will also collaborate with other marketers to bring in new customers through joint promotions, she said.

“There is a lot of interest in doing things in a different way,” Ms. Howard said. “People are hungry to find alternatives.”

Outdoor apparel company Eddie Bauer will redirect some money to tools that it already uses, like the ads that show up when consumers search Google or Amazon for terms such as “hiking shorts,” according to Damien Huang, president at the company.

Eddie Bauer also plans an updated test of advertising within Gmail, something it tried previously, plus new territory for the brand such as TikTok and Snap Inc.’s Snapchat.

Clothing and design brand Eileen Fisher Inc. said it would increase spending on current tactics such as using Google Display Network and Rakuten Inc., the Japanese online merchant, to attract new customers and re-contact existing ones with online display ads, for example.

And it will lean more on marketing programs like the one from RewardStyle Inc., which helps find influencers who might promote brands to their followers.

Company executives are also exploring the use of streaming TV services for later in the year, drawn in part by increased viewing as lockdowns during the virus pandemic forced people to stay home, said Jamie Habanek, director of brand marketing.

“It’s a shift that we were already talking about and could become more important if we decide that we have to move away from Facebook and Instagram for a longer period of time,” Ms. Habanek said.

Not every boycotter will reallocate its Facebook and Instagram ad spending to other advertising and marketing channels: REI, the outdoor retailer, said it will spend the money elsewhere in its business instead.

Updated: 7-3-2020

Facebook Boycott Organizers Want A Civil Rights Expert In The Company’s Executive Suite

Groups leading the advertising boycott of Facebook have outlined 10 initial steps they want Facebook to take.

Facebook Inc. leaders including Chief Executive Mark Zuckerberg and Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg are set to meet early next week with civil rights groups that called for an advertising boycott against the company over its handling of hate speech and misinformation.

Among the top requests from the groups will be for Facebook to hire an executive with civil rights expertise for a post in the social-media giant’s C-suite.

“If they have civil rights leadership that’s experienced in the C-suite, it will keep the company accountable on those issues,” said Jonathan Greenblatt, chief executive of the Anti-Defamation League, one of the organizers of the boycott.

Leaders of civil rights groups are meeting with Facebook executives after calling for an ad boycott of the platform for the month of July.

Facebook, which has been under growing pressure to change and update some of its content and brand-safety policies, this week requested a new meeting with civil rights leaders, including Mr. Greenblatt, Rashad Robinson, president of Color of Change, and Derrick Johnson, president and CEO of the NAACP.

“We share the goal of these organizations; we don’t benefit from hate and we don’t want it on our platforms,” a Facebook spokeswoman said in a statement. “We look forward to hearing directly from these organizations and sharing an update on the investments we’ve made and the work we’re continuing to do.”

The civil rights leaders want Facebook to make meaningful changes and be more accountable at the top echelons of its leadership structure. Facebook executives, such as Joel Kaplan, the company’s vice president of global public policy, play a role in content decisions.

But they have a conflict of interest because they also are looking to curry favor with politicians who may have their own opinions about content on Facebook, said Mr. Robinson.

“There needs to be a separation between content security and safety, and the people who lobby with politicians,” Mr. Robinson said.

Facebook’s work in this area includes embedding civil rights expertise on teams across policy and product, the company said.

The ad boycott is just one of many pressures confronting Facebook, which also has been under fire from many employees, activists and Democrats who say it has failed to enforce its rules against politicians, including President Donald Trump.

Several employees have disagreed publicly with Facebook’s stances on a variety of issues, including its recent decision to leave up a post by Mr. Trump that many academics and employees say violated the company’s rules about inciting violence.

Some employees say some of these missteps stem from the lack of diversity at the top of the company.

Thursday, a Black Facebook employee and two job candidates filed a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission saying Facebook is biased against Black employees and makes it more difficult for them to get hired and promoted. Among other issues, the employee said he heard the N-word said at work.

“We believe it is essential to provide all employees with a respectful and safe working environment. We take any allegations of discrimination seriously and investigate every case,” a Facebook spokesman said in a statement.

The civil-rights groups have listed 10 steps they would like Facebook to take, and say each one is important. But Mr. Greenblatt said another priority among them is for regular, outside audits of identity-based hate speech and misinformation on the company’s platforms, with the results made available publicly.

Whether Facebook will agree to any of the groups’ specific recommendations is far from certain. Facebook executives, including Carolyn Everson, vice president of its Global Business Group, previously told advertisers that the company wouldn’t change its policies based on revenue pressure.

Mr. Greenblatt said the boycott wasn’t about making a dent in Facebook’s ad revenue, which totaled $69.7 billion last year, mostly from small and medium-size companies. The goal is to get the company’s attention and encourage change, he said.

Advertisers that have paused spending on Facebook and Instagram include Unilever PLC, Clorox Co., Starbucks Corp., Ford Motor Co., Microsoft Corp., Coca-Cola Co., Levi Strauss & Co. and Verizon Communications Inc. But not every one of them is a member of the boycott campaign, and may have different priorities.

Some of the boycott organizers’ recommendations speak more directly to advertising concerns, including broadening Facebook’s brand-safety tools and providing more refunds when ads appear next to objectionable content.

Facebook issues refunds when ads run in videos and some other content formats that violate its policies, but the policy doesn’t include ads that run next to Facebook’s main news feed, according to a person familiar with the matter.

Other steps requested of Facebook by the boycott organizers include the creation of an internal system to automatically flag hateful content in private groups for human review, and the finding and removing of public and private groups focused on white supremacy, violent conspiracies, vaccine misinformation and other objectionable content.

Facebook addressed some of the groups’ requests in a blog post on Wednesday, describing some of the steps it has taken and its plans for countering hate speech and misinformation, as well as for ensuring a safer environment for advertisers.

The company said it already generates reports on suspected hate speech and funnels them to reviewers with training in identity-based hate policies in 50 markets and 30 languages.

It also said it is exploring ways to make users who moderate groups on Facebook more accountable for the content in those groups.

On Tuesday, Facebook also classified a large segment of the boogaloo movement as a dangerous organization and banned it from its network for “actively promoting violence against civilians, law enforcement and government officials and institutions.”

Civil rights leaders said they had notified Facebook earlier about the presence of this movement on its platforms.

“Facebook had a knowledge of the growing boogaloo presence on their site and they did nothing about it,” said Mr. Johnson of the NAACP. “What must happen is a change in their algorithm so those white supremacists and hate groups are not directed at their targeted audiences.”

Facebook said it has removed boogaloo content when it has identified a clear call for violence, including pulling more than 800 posts in the last two months.

Earlier this week, Facebook announced it would include the prevalence of hate speech as a data point in its Community Standards Enforcement Report, through which the platform shares updates on its progress combating content that violates its policies. The reports are assembled and issued by Facebook, which said it would now release those reports quarterly.

Mr. Zuckerberg previously said Facebook would look to open its content moderation systems for external audit. The company also agreed to a new outside audit by the Media Rating Council, the ad industry’s measurement watchdog, which will evaluate Facebook’s content monetization and brand-safety tools and practices.

Facebook has said that 90% of the hate speech it removes is found by its artificial-intelligence tools before users report it.

Mr. Robinson, the Color of Change president, said that doesn’t account for possible hate-speech that goes undetected.

Updated: 7-7-2020

Civil-Rights Groups Express Disappointment With Facebook Meeting

Social-media giant says it would begin labeling politicians’ posts that have violated its content standards.

Civil rights advocates came out of a meeting Tuesday with Facebook Inc. FB 0.24% Chief Executive Mark Zuckerberg saying they didn’t make progress on their demands over how the social-media giant polices the platform.

The lack of headway, one week into a boycott by some of the company’s top advertisers over the issue, points toward the likelihood of a protracted campaign that could extend beyond July, the original time frame. The organizers said they’re asking more advertisers to pause their spend on Facebook globally.

“Facebook had our demands in multiple ways, and they showed up to the meeting expecting an A for attendance,” said Rashad Robinson, head of the Color of Change, a progressive advocacy group for Black communities.

After years of simmering discontent and requests for change, a coalition including Anti-Defamation League and Color of Change are making the case that Mr. Zuckerberg and Facebook haven’t combated racism and misinformation on its platforms in good faith. Top brands including Unilever and Clorox have agreed to pause advertising on the platform in a show of solidarity with demands Facebook do more.

In response to the discontent, Mr. Zuckerberg had pledged to reconsider its policies around discussion of the government’s use of force. The company has also said it would begin labeling politicians’ posts that have violated its content standards but are protected by Facebook on the grounds that they are newsworthy.

“They want Facebook to be free of hate speech and so do we,” the company said in a statement after the meeting. The company said it has invested billions of dollars in content moderation and taken hundreds of white supremacist entities off its platforms. “We know we will be judged by our actions not by our words and are grateful to these groups and many others for their continued engagement.”

The meeting over Zoom lasted a little over an hour and involved Mr. Zuckerberg, Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg, product chief Chris Cox, other members of Facebook’s policy team and a product official, the groups said.

“Today we saw little and heard just about nothing,” said Jonathan Greenblatt, chief executive of the Anti-Defamation League, which is devoted to combating anti-Semitic speech.

On paper, the differences between Facebook and civil rights organizations seem limited. Both agree that incitements to violence have no place on Facebook, that hate speech should be suppressed and that the company should vet its products for potential bias. While there are meaningful disagreements about subjects including Facebook’s refusal to fact-check political advertising, Facebook has said it broadly shares the protesters’ goals.

But the civil-rights groups argue that Facebook hasn’t lived up to its past commitments to address misinformation, hate speech, radicalization and brand-safety concerns. A turning point came with Mr. Zuckerberg’s free-speech talk at Georgetown University in October, when the executive framed Facebook as a democratically essential “fifth estate.” Mr. Zuckerberg framed progressive calls to restrain rhetoric on the platform as a greater risk than civil rights’ leaders concerns about the platform’s misuse.

The Rev. Bernice King, CEO of the King Center, said the talk failed to acknowledge how tolerance for toxic rhetoric set the table for the assassination of her father, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Vanita Gupta, who as head of the Leadership Conference on Civil & Human Rights had been one of the most active liaisons to Facebook, wondered “if there’s any point to engagement at all.”

The gap has only widened since protests over police killings of Black Americans and President Trump’s social media-led rhetoric about Black Lives Matter protesters, alleged corruption in absentee voting and the historical value of Confederate monuments. After Twitter labeled Mr. Trump’s tweet—that “when the looting starts the shooting starts”—as an incitement to violence, civil rights groups seized on Facebook’s unwillingness to do the same.

Updated: 7-3-2020

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg Doesn’t Think Ad Boycott Will Change Anything

Facebook Inc. Chief Executive Mark Zuckerberg isn’t overly concerned about the advertising boycott and doesn’t believe anything is going to change in the long-run, according to a report published by The Information today.

More than 500 companies have so far said they will send advertising on Facebook, names that include Verizon Communications Inc., Coca-Cola Company, Levi Strauss & Co., Unilever Plc, Ford Motor Co., Starbucks Corporation and Adidas AG.

Those companies, along with various civil rights groups, have called for the boycott due to Facebook’s policies on the speech and the proliferation of misinformation spread on the platform. Much of the condemnation came after the company did not act on an inflammatory post made by President Donald Trump in regards to the protests after George Floyd’s death.

“We’re not gonna change our policies or approach on anything because of a threat to a small percent of our revenue, or to any percent of our revenue,” Zuckerberg said in a virtual meeting with staff last Friday, according to The Information that got hold of a recording.

“My guess is that all these advertisers will be back on the platform soon enough.” Zuckerberg reportedly went on to say that the boycott was a “reputational and a partner issue”, rather than a financial issue.

After large brands joined the boycott this week, the company saw its market value plunge $60 billion, although it seems the loss was short-lived. Facebook has tried to appease advertisers and the public alike, this week saying that it had made changes to the News Feed so that more trustworthy news would be ranked higher.

According to analysis undertaken by Fortune, the boycott will have little impact on Facebook anyway. The company’s 8 million advertisers created a revenue of around $70 billion last year, but according to that analysis, it would take thousands of companies to join the boycott to make a dent in Facebook’s bottom line. That’s why it’s been called symbolic, rather than any threat to the company. Zuckerberg is likely correct in that the boycott concerns reputation over anything else.

Updated: 7-19-2020

Disney Slashed Ad Spending on Facebook Amid Growing Boycott

Hundreds of advertisers have paused spending on social network due to concerns about hate speech, divisive content.

Walt Disney Co. has dramatically slashed its advertising spending on Facebook Inc., according to people familiar with the situation, the latest setback for the tech giant as it faces a boycott from companies upset with its handling of hate speech and divisive content.

Disney was Facebook’s top U.S. advertiser for the first six months of 2020, research firm Pathmatics Inc. estimates. It joins hundreds of other companies that have paused spending, including Unilever PLC, Starbucks Corp., Ford Motor Co., Verizon Communication Inc. and many small marketers.

Civil-rights groups including the Anti-Defamation League and NAACP called on advertisers to pull ad spending for July, arguing Facebook hasn’t made enough progress enforcing its policies on hate speech and misinformation.

Some brands paused spending for longer stretches; the time frame for Disney’s pullback wasn’t clear. Unlike many other companies, Disney didn’t make a public announcement that it was cutting back on Facebook, but instead shifted advertising plans quietly.

The entertainment giant, which is concerned about Facebook’s enforcement of its policies surrounding objectionable content, has paused advertising of its streaming-video service Disney+, the people familiar with the situation said. Disney has promoted the service heavily this year and it makes up a substantial portion of the company’s spending on marketing.

In the first half of this year, Disney spent an estimated $210 million on Facebook ads for Disney+ in the U.S., according to Pathmatics. Disney was the biggest ad spender during that period. Last year, it was the No. 2 Facebook advertiser in the U.S., behind Home Depot Inc.

Disney also paused spending on Facebook-owned Instagram for its sister streaming service Hulu, a person familiar with matter said. Hulu spent $16 million on Instagram from April 15 to June 30, Pathmatics said.

Other divisions of Disney are also re-examining their advertising on Facebook. Ads for ABC and Disney-owned cable networks such as Freeform have all but vanished from the site. While there are fewer shows to market during the summer, a person familiar with the matter said, it is unlikely that ads will return when new episodes need to be promoted, unless the social platform polices itself better.

It couldn’t be determined how much Disney businesses are spending on Facebook.

Disney representatives had no comment.

“We know we have more work to do,” Facebook said in a statement, adding that it would work with civil-rights groups, a leading ad trade group and other experts “to develop even more tools, technology and policies to continue this fight.”

Facebook has said it invests billions of dollars to keep its platforms safe and has banned 250 white-supremacist organizations from Facebook and Instagram. It also has said artificial intelligence helps it find nearly 90% of hate speech before anyone flags it.

Earlier this month, the company said it would start labeling political speech that violates its rules and take other measures to prevent voter suppression and protect minorities from abuse.

Facebook has around $70 billion in annual advertising revenue, generated from over eight million advertisers. It would take a sustained boycott from its biggest advertisers to put a significant dent in the company financially.

Some marketers are reducing ad spending broadly because of financial pressures caused by the coronavirus pandemic. Many brands prefer not to cut Facebook ad spending, because they regard it as an especially effective marketing vehicle.

While Disney has been aggressively marketing Disney+ during the pandemic, it has had less reason to market other areas of its business, such as its theme parks, which have been closed until recently. Disney’s movie studio, which is typically a heavy ad spender, has been forced to delay the release of new movies because of theater closures.

Marketers are demanding that Facebook find ways to keep their ads away from objectionable content.

The company, which has been meeting with advertisers and agencies, said late last month that it planned to evaluate the rules publishers and creators must follow if they wanted to make money from their Facebook content through ads. It will also assess the tools it gives brands to ensure their ads don’t appear near inappropriate content. The audits will be handled by industry measurement watchdog Media Rating Council.

Civil-rights groups met virtually with Facebook executives on July 7 and came away from the Zoom call feeling the tech company wasn’t taking sufficient steps to address their concerns.

Stop Hate for Profit, the name of the coalition behind the boycott effort, has laid out 10 steps that it wants Facebook to take, such as adopting “common-sense changes” to its policies to reduce hate on its platforms and remove content that could inspire people to commit violence.

In a statement following the meeting, Facebook said, “We will be judged by our actions, not by our words, and are grateful to these groups and many others for their continued engagement.”

Facebook executives, including Carolyn Everson, vice president of its Global Business Group, previously told advertisers that the company wouldn’t change its policies based on revenue pressure.

Updated: 7-31-2020

Some Facebook Ad Boycotters Return—but Plenty of Big Players Are Staying Away

North Face, Pernod Ricard and Heineken are back on the social network; Beam Suntory, Eddie Bauer and SAP aren’t.

Some advertisers that left Facebook Inc. for July to protest its handling of hate speech on its platforms say they are coming back, while the tech giant’s financial outlook suggested the boycott isn’t taking a major financial toll.

VF Corp.’s North Face, arguably the first widely known brand to join the campaign, said it would resume doing business with Facebook in August. “We are encouraged by the initial progress and recognize that change doesn’t happen overnight,” said a spokeswoman for North Face.

Marketers including brewer Heineken, sportswear maker Puma SE and spirits giant Pernod Ricard SA also said they would return to Facebook.

Other brands said they would extend their planned July boycotts into August at least, however, calling Facebook’s moves insufficient. They include packaged-goods marketer J.M. Smucker Co., spirits maker Beam Suntory Inc., retailer Eddie Bauer LLC, business-software company SAP SE and Boston Beer Co.

Volkswagen AG said Friday that it will resume advertising with Facebook everywhere but the U.S., where it will extend its boycott. “Except in the U.S., we have seen great progress and movement in the right direction,” the company said in a statement provided by a spokesman for Volkswagen Group of America. The spokesman said he did not have further information.

In June, civil-rights groups including the Anti-Defamation League and NAACP asked marketers to pull ad spending on Facebook and Facebook-owned Instagram for July, recommending 10 steps that they said Facebook should take to reduce hate speech and misinformation on its platforms. The steps included appointing a civil-rights expert at the upper echelons of the company and providing refunds to advertisers whose ads appeared next to objectionable content.

Since the boycott began, Facebook said it would hire an employee at the vice-president level to focus on civil-rights work. It also agreed to a new audit by industry measurement watchdog the Media Rating Council, expected to begin in August, that will evaluate the rules publishers and creators must follow if they want to make money from their Facebook content through ads, among other aspects of Facebook’s ads business.

“We’ve invested billions of dollars to keep hate off of our platform, and we have a clear plan of action with the Global Alliance for Responsible Media and the industry to continue this fight,” said a Facebook spokeswoman. The Global Alliance for Responsible Media is a group of advertisers, media companies, tech companies and others focused on improving safety standards online. Facebook’s commitments to GARM include adopting proposals regarding the definition of hate speech and two outside audits of its transparency reports and ad policies.

In a call Thursday afternoon to discuss second-quarter earnings, Facebook Chief Executive Mark Zuckerberg said the company valued all of its advertisers but wasn’t dependent on major brands. Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg said the company is working on civil rights “not because of pressure from advertisers, but because it is the right thing to do.”

Facebook said ad revenue in the first three weeks of July, when the boycott was in effect, increased at roughly the same 10% year-over-year rate as it did in the second quarter. It cited the boycott among the factors contributing to its performance in the third quarter, along with economic uncertainty related to the coronavirus pandemic and new restrictions on ad targeting.

Facebook had more than 9 million advertisers in the second quarter, it said. More than 1,100 advertisers participated in the boycott, according to organizers.

Jonathan Greenblatt, chief executive of the Anti-Defamation League, said Facebook’s decision to appoint a civil-rights leader and its creation of teams to study and address potential racial bias on its platforms proved that the “Stop Hate for Profit” boycott campaign produced results.

While some advertisers may resume spending on Facebook, Mr. Greenblatt said, the company still hasn’t done enough and the campaign will continue. “Ultimately, this movement will not go away until Facebook makes the reasonable changes that society wants—they have shown a willingness to do some of that,” he said.

He said some advertisers agreed to join a future boycott if required, though he declined to name them.

Beyond the North Face, two other VF Corp. units—backpack brand JanSport and sneaker marketer Vans—also said they would end their boycotts when July ends. All said they would hold regular check-ins with Facebook about its policies and the content on its platform.

A spokesman for Puma, one of the companies ending its boycott, said the company was “encouraged by the progress that has been made in regards to tackling hate speech, racism and discrimination on Facebook’s platform.”

But Smucker, whose brands include Folgers coffee and Jif peanut butter, and other marketers extending their boycotts said Facebook hadn’t delivered an adequate plan.

And advertisers that paused their Facebook spending for longer periods or without a set return date, such as Unilever PLC, Coca-Cola Co., Chipotle Mexican Grill Inc. and Verizon Communications Inc., said they aren’t ready to come back.

Coca-Cola, which pulled back from all social-media advertising on July 1, said it was returning to YouTube and LinkedIn on Aug. 1 but not Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.

Verizon didn’t join the “Stop Hate for Profit” campaign but suspended Facebook and Instagram ads in June after the Anti-Defamation League released a screenshot showing a Verizon ad next to a Facebook post alleging that FEMA was preparing to put people in concentration camps.

That incident reflected one major area of concern for advertisers: the chance that their ads could appear next to objectionable content.

That is particularly true within Facebook’s news feed, where advertisers don’t have controls to limit what type of content or posts their ads might appear next to. Facebook said it is looking into the issue, but advertisers want concrete actions and results, according to two senior ad buyers who have had discussions with Facebook executives on the matter.

Advertisers have brand-safety controls for ads on other parts of Facebook, such as videos on Facebook Watch, but Facebook’s biggest and most important ad placement remains its news feed, the buyers said.

“Everyone is buying feed,” said one of the buyers, whose agency spends hundreds of millions of dollars on Facebook annually. “And that’s the biggest thing we’re dissatisfied with—their [lack] of commitment to making changes in the news feed.”

Facebook has around $70 billion in annual advertising revenue, providing plenty of insulation during the boycott.

Many brands, especially so-called direct-to-consumer companies and other performance marketers, didn’t cut Facebook ad spending because they regard it as an effective and important marketing vehicle.

“There’s a middle segment of clients who boycotted and are not happy with Facebook but can’t afford not to be on Facebook in some capacity—because their business models say they need to be on Facebook or because their audience is already there,” said one of the ad buyers.

In a sign of Facebook’s continued importance and consumer reach, Unilever-owned Ben & Jerry’s Homemade Inc. said it won’t advertise its products on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter for the rest of the year—but it will still buy ads from the companies for its social-justice and election-related work.

“This work is too important to ‘unilaterally disarm’ across these platforms that remain powerful channels to engage citizens on these critically important issues,” a spokesman said.

Updated: 8-26-2020

Facebook Says Apple’s New iPhone Update Will Disrupt Online Advertising

The social-media company says Apple’s privacy changes will affect its Audience Network business, which connects users’ Facebook identities with their off-platform activities.

Facebook Inc. said privacy changes in Apple Inc.’s latest operating system would cripple its ability to place personalized ads and deal a financial blow to app-makers, highlighting a high-stakes clash between the tech titans over the rules of the road in the mobile-internet economy.

Under Apple’s changes, which will go into effect this fall in its iOS14 operating system, Facebook and other companies that facilitate online advertising will no longer be able to collect a person’s advertising identifier without the user’s permission. Many apps will begin asking users whether or not they want their behavior on the web to be tracked for the purposes of personalized ads.

Facebook fears many users will reject tracking, if given the choice, affecting not only its business but also any app that uses its services to sell ads, from game-makers to news publishers. Facebook told app developers Wednesday the changes will affect its “Audience Network” business, which facilitates ad sales in outside apps.

Apple’s move also will hit Google’s AdMob unit, which facilitates ad sales in apps, as well as several ad-technology companies that rely on tracking iPhone users. Apple’s ad identifier, or IDFA, is a 32-character string of numbers widely used in the digital ad and data-broker industries to match up datasets that reveal where users go online, what they do and what they buy.

An Apple spokesman said the company welcomed in-app advertising and wasn’t prohibiting tracking. Apple was simply requiring each app to obtain users’ explicit consent to track, the spokesman said.

Facebook’s announcement is another shot in the increasingly contentious relationship between the two companies, whose different business models have led to public sparring. Apple, which produces devices sold worldwide, says it is standing up for user privacy, and has criticized the data-collection operation that underlies Facebook’s advertising business.

Facebook, meanwhile, prizes the free flow of data that underpins digital marketing and has faulted Apple for the exclusionary nature of its platform.

Apple’s latest policy change adds more momentum to a big shift in the internet world, as moves to enhance user privacy make it harder to track what users are doing online.

Google plans to block the use of “cookies”—snippets of code that help track users’ web behavior—in its Chrome browser by 2022, following in the footsteps of Apple’s Safari. New privacy laws in the European Union and California give users more control over ad tracking.

“Apple’s policy change is accelerating a paradigm shift—that was already well under way—towards consumers having rightful ownership and control over their data,” said Matt Littin, co-founder and CEO of gaming company Lootcakes.

Facebook doesn’t disclose the size of the Audience Network business within its nearly $70 billion digital-ad empire. Before the Covid-19 pandemic struck, ad-tech consulting firm Jounce Media estimated Facebook Audience Network would bring in $3.4 billion in 2020. The Apple change could also affect Facebook’s sale of ads on its own properties, since apps that use Facebook code—from food-delivery apps to games—send data back to the company.

“If advertising effectiveness suffers, it will limit the scale of ad spend on Facebook in the future, consequently limiting Facebook’s growth,” said digital-ad consultant Ratko Vidakovic. Still, Facebook is far better positioned to weather such difficulties than other ad-industry players because of the vast quantities of data it collects directly from users.

Facebook expects the impact from Apple’s new consent requirements will be significant enough that the company acknowledged the changes on its July 30 earnings call. Facebook said that it was continuing to ask Apple for guidance, and might revisit the way it handles the advertising identifier if Apple provides it.

Facebook said Audience Network will continue to operate on Apple devices using previous operating systems and those made by other manufacturers.

Facebook said the changes would likely result in reduced earnings for developers of apps “at an already difficult time for businesses.” That is because ads that can be targeted at users based on data about their interests and online habits generally bring in more revenue for publishers.

Some publishers have expressed concern that ad prices will fall for iPhone users who don’t agree to tracking. Facebook said in preliminary testing it has seen a 50% drop in publisher revenue when personalization was removed from advertising.

One major digital publisher is weighing options to help cope with Apple’s change, including requiring app users to provide their email addresses or showing users a second prompt asking them to opt into the tracking. Game publisher Activision Blizzard Inc. acknowledged in an earnings call that the change would affect its business, but didn’t elaborate.

Others in the app world were more optimistic that app makers could adapt. “A critical mass of consumers may be willing to share data if companies provide explicit and sufficiently meaningful benefits for them to do so,” said Mr. Littin of Lootcakes.

In a survey by Tap Research Inc. 85% of respondents said if given the choice they would ask apps not to track them.

Apple isn’t a big player in online advertising, but it does have its own small business that personalizes ads shown in the App Store and on Apple News based on where users go and what users do in Apple’s apps. The company is applying separate rules for its own ad-personalization; to opt out, users must find an option in the iPhone’s settings.

Apple Chief Executive Tim Cook has made privacy one of the company’s priorities in recent years, running advertisements based on its intent to protect user data and refusing to comply with some law-enforcement requests to unlock iPhones for high-profile investigations.

Mr. Cook has also sought to turn a principle advocated by his predecessor, Steve Jobs—that “our customers are not our product”—into a business strategy.

The company has gradually aimed to increase customer awareness of the value of privacy with features such as a sign-in option on apps that conceals personal information and a browser update that reveals how sites track users.

“Our view of privacy started from our values, then we crafted a business plan from that,” Mr. Cook said during a Fortune conference in 2018.

Apple critics have argued the company is limiting access to its platform to restrict competition. Facebook earlier this month joined those protesting Apple’s 30% cut from transactions within apps, saying in a product release that it asked for an exemption but was refused.

Facebook at the time presented the issue as a benefit for small businesses struggling during the pandemic.

Updated: 12-16-2020

Google Is Accused of Enlisting Facebook To Aid In Ad-Rigging

Ten states sue google, alleging deal with facebook to rig online ad market

Texas-led coalition accuses Alphabet unit of striking arrangement with rival tech giant to preserve its own dominance; legal action follows federal case.

Ten states sued Google Wednesday, accusing the search giant of running an illegal digital-advertising monopoly and enlisting rival Facebook Inc. FB 0.04% in an alleged deal to rig ad auctions that was code-named after “Star Wars” characters.

The complaint, filed in U.S. District Court in Texas, alleges that Facebook emerged in 2017 as a powerful new rival to Google, challenging the Alphabet Inc. unit’s established dominance in online advertising.

Google responded by initiating an agreement in which Facebook would curtail its competitive moves, in return for guaranteed special treatment in Google-run ad auctions, the lawsuit claims.

Google’s internal code name for the alleged Facebook deal referenced characters from Star Wars, according to the suit, which redacted specifics. A person familiar with the matter said the code name was “Jedi Blue,” after the sci-fi franchise’s Jedi knights.

“Google is a trillion-dollar monopoly brazenly abusing its monopolistic power, going so far as to induce senior Facebook executives to agree to a contractual scheme that undermines the heart of [the] competitive process,” Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, who led the suit, said in a statement.

The accusations opened up a fresh front of criticism for both tech giants, each of which face federal antitrust lawsuits filed in recent weeks.

Facebook declined to comment. Google denied engaging in any anticompetitive behavior and repeated its stance that it operates in highly competitive markets.

“Attorney General Paxton’s ad tech claims are meritless, yet he’s gone ahead in spite of all the facts. We’ve invested in state-of-the-art ad tech services that help businesses and benefit consumers,” a Google spokesperson said Wednesday. “We will strongly defend ourselves from his baseless claims in court.”

The spokesperson said that the allegation about Facebook isn’t accurate and that the company doesn’t receive special data.

Nine other attorneys general, all Republicans like Mr. Paxton, joined the lawsuit. Noticeably absent were Democrats who had initially joined Texas in launching a bipartisan state investigation of Google last fall, though it is possible more states could join the suit later.

A separate, bipartisan group of state attorneys general is preparing another antitrust case against Google, which is expected to target its search business and could filed as soon as Thursday.

The Texas-led case contains allegations that aren’t addressed in detail in a Justice Department lawsuit filed Oct. 20 against Google. The federal suit focused on Google’s flagship search business, alleging it maintains its status as gatekeeper to the internet through an unlawful web of exclusionary and interlocking business agreements that shut out competitors.

Wednesday’s complaint traces back more than a decade, alleging that Google quietly built up and defended its dominance in the market for digital ads, beginning with its acquisition of the ad-technology firm DoubleClick in 2008.

Many of the accusations involve Google’s ad-tech software, which is used to buy and sell ads on sites across the web. Google owns the dominant tool at every link in the complex chain between online publishers and advertisers, giving it unique power over the monetization of digital content. It also owns key platforms for reaching consumers, such as YouTube.

The Texas-led suit accuses Google of illegally tying these products to one another, leveraging its power in one part of the advertising chain to force publishers or advertisers to use another Google-owned tool.

The claims echo past concerns from advertising-technology companies and news publishers. They say Google created a system rife with conflicts of interest, in which it used its superior data advantage and dominant position in the marketplace to give preference to its own tools and steer money to its own properties.

Google “now uses its immense market power to extract a very high tax of [REDACTED] percent of the ad dollars otherwise flowing to the countless online publishers and content producers like online newspapers, cooking websites and blogs who survive by selling advertisements on their websites and apps,” the lawsuit says.

The suit alleged that this added cost “is ultimately borne by American consumers through higher prices and lower quality on the goods, services and information those businesses provide.”

The complaint also targets Google for allegedly influencing an initiative for developing mobile webpages, known as Accelerated Mobile Pages, to effectively force publishers to adopt a format that would make it harder to use alternative ad technologies on those pages.

The suit alleges that Google came up with a secret program to harm publishers, code-named in reference to the “Star Wars” franchise, with the precise name redacted in the complaint.

The program appeared to allow publishers more freedom to choose among exchanges that match the buyers and sellers of digital ads, the lawsuit alleged. But it says that Google “secretly let its own exchange win, even when another exchange submitted a higher bid.”

The program was “designed…to avoid competition and the program consequently hurt publishers,” the suit says, citing an internal Google communication.

The company has consistently disputed claims that it dominates the advertising technology market.

“To suggest that the ad tech sector is lacking competition is simply not true,” it said in a blog post last year. “To the contrary, the industry is famously crowded. There are thousands of companies, large and small, working together and in competition with each other to power digital advertising across the web, each with different specialties and technologies.”

According to the lawsuit, Google went to great lengths to preserve its market power.

When Facebook emerged as a threat, “Google made overtures to Facebook,” the lawsuit says, with the two parties allegedly entering into the Jedi Blue deal. Facebook withdrew as a direct threat in return for Google giving Facebook “information, speed and other advantages in the auctions that Google runs” for publishers’ mobile advertising, the lawsuit says.

“The parties agree on [REDACTED] for how often Facebook would [REDACTED] publishers’ auctions—literally manipulating the auction with [REDACTED] for how often Facebook would bid and win,” the suit says.

The lawsuit seeks monetary damages from Google and asks the court to restrain Google’s behavior, including via “structural relief to restore competitive conditions in the relevant markets.”

States joining in the Texas-led case include Arkansas, Idaho, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, North Dakota, South Dakota and Utah.

The federal suit filed this fall highlighted Google’s relationship with another tech giant, Apple Inc., alleging that Google uses billions of dollars collected from advertising to pay for mobile-phone manufacturers, carriers and browsers such as Apple’s Safari to maintain Google as their preset, default search engine.

Taken together, the cases risk tarnishing Silicon Valley’s reputation with suggestions of preferential arrangements that harm both consumers and potential competitors.

The lawsuits could take years to resolve. Eventually, the state and federal lawsuits against Google could be combined into a single case.

Up to now, the states have coordinated with the Justice Department, which also has been posing increasingly detailed questions—to Google’s rivals and to executives inside the company—about how Google’s third-party advertising business interacts with publishers and advertisers, according to people familiar with that probe.

Wall Street Journal publisher News Corp, a longtime Google critic, was among the publishers contacted by antitrust investigators, along with New York Times Co. , Gannett Co. , Nexstar Media Group Inc. and Condé Nast, some of the people said.

David Chavern, chief executive of the News Media Alliance trade association, welcomed the states’ suit. “Quality local journalism has been directly damaged by Google’s anticompetitive conduct, and we look forward to the judicial authorities examining the full range of their behaviors and businesses,” he said.

Updated: 12-20-2020

Google, Facebook Agreed To Team Up Against Possible Antitrust Action, Draft Lawsuit Says

Draft lawsuit quotes Facebook’s Sandberg saying Google pact was a ‘big deal strategically’.

Facebook Inc. and Alphabet Inc.’s Google agreed to “cooperate and assist one another” if they ever faced an investigation into their pact to work together in online advertising, according to an unredacted version of a lawsuit filed by 10 states against Google last week.

The suit, as filed, cites internal company documents that were heavily redacted. The Wall Street Journal reviewed part of a recent draft version of the suit without redactions, which elaborated on findings and allegations in the court documents.

Ten Republican attorneys general, led by Texas, are alleging that the two companies cut a deal in September 2018 in which Facebook agreed not to compete with Google’s online advertising tools in return for special treatment when it used them.

Google used language from “Star Wars” as a code name for the deal, according to the lawsuit, which redacted the actual name. The draft version of the suit says it was known as “Jedi Blue.”

The lawsuit itself said Google and Facebook were aware that their agreement could trigger antitrust investigations and discussed how to deal with them, in a passage that is followed by significant redactions.

The draft version spells out some of the contract’s provisions, which state that the companies will “cooperate and assist each other in responding to any Antitrust Action” and “promptly and fully inform the Other Party of any Governmental Communication Related to the Agreement.”

In the companies’ contract, “the word [REDACTED] is mentioned no fewer than 20 times,” the lawsuit says. The unredacted draft fills in the word: Antitrust.

A Google spokesperson said such agreements over antitrust threats are extremely common.

The states’ “claims are inaccurate. We don’t manipulate the auction,” the spokesperson said, adding that the deal wasn’t secret and that Facebook participates in other ad auctions. “There’s nothing exclusive about [Facebook’s] involvement and they don’t receive data that is not similarly made available to other buyers.”

The redacted lawsuit filed last week makes no mention of Facebook Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg. According to the draft version, Ms. Sandberg signed the deal with Google. The draft version also cites an email where she told CEO Mark Zuckerberg and other executives: “This is a big deal strategically.”

Like Google, Facebook has also disputed the allegations in the lawsuit, saying its agreements for bidding on advertising promote choice and create clear benefits for advertisers, publishers and small businesses.

“Any allegation that this harms competition or any suggestion of misconduct on the part of Facebook is baseless,” a Facebook spokesperson said.

The final version of the lawsuit didn’t make public details about the deal’s value. The draft states that starting in the deal’s fourth year, Facebook is locked into spending a minimum of $500 million annually in Google-run ad auctions. “Facebook is to win a fixed percent of those auctions,” the draft version says. The lawsuit says “Facebook is to [REDACTED].”

According to the draft version, an internal Facebook document described the deal as “relatively cheap” when compared with direct competition, while a Google presentation said if the company couldn’t “avoid competing with” Facebook, it would collaborate to “build a moat.” The redacted lawsuit filed last week doesn’t include those quotes.

The lawsuit alleges that Google executives worried ahead of the deal about competition from Facebook as well as others deploying “header bidding,” a technique for buying and selling online ads.

In an internal Google presentation from October 2016, an employee expressed concern about the potential for competition from Facebook and other big tech companies, saying, “to stop these guys from doing HB [header bidding] we probably need to consider something more aggressive,” according to the draft.

The redacted lawsuit discusses Google’s concerns about competition and mentions the presentation, but it doesn’t include the quote.

According to an internal Google communication from November 2017 discussing a potential “Facebook Partnership” for Google’s “Top Partner Council,” Google said that its endgame was to “collaborate when necessary to maintain status quo…” The redacted lawsuit describes a presentation about Google’s endgame, but doesn’t include the quotes.

As the two sides neared agreement, according to the draft, Facebook’s negotiating team sent an email to Mr. Zuckerberg, saying the company faced options: “invest hundreds more engineers” and spend billions of dollars to lock up inventory, exit the business, or do the deal with Google. Mr. Zuckerberg wanted to meet before making a decision, according to the draft.