Economic Effects Of The Black Death Pandemic And What US Citizens Could Learn About Wealth Redistribution

People need certain things and to have certain things done, and others provide these through their labor, at a price. Economic Effects Of The Black Death Pandemic And What US Citizens Could Learn About Wealth Redistribution

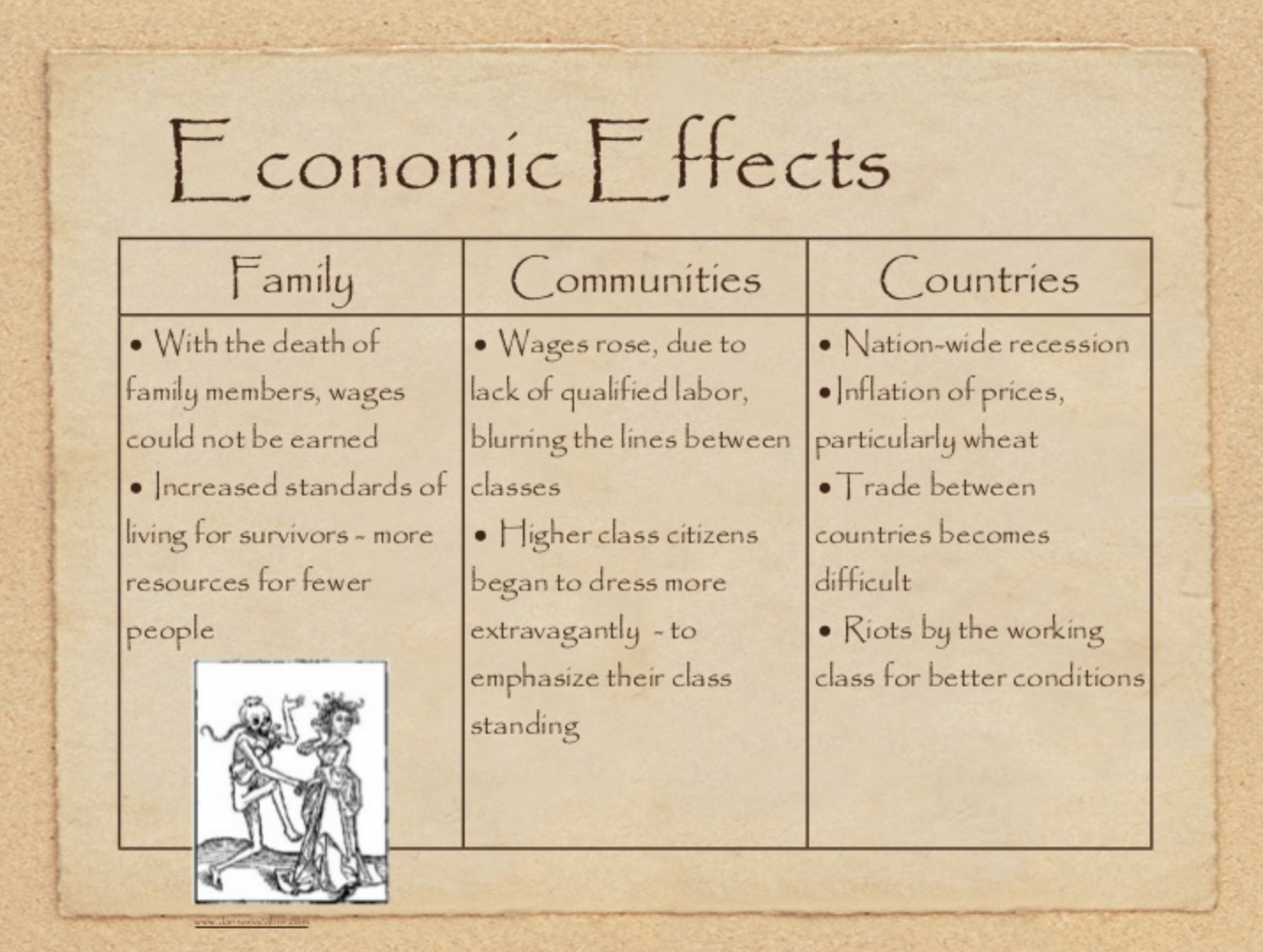

As in other aspects of social and cultural change, feudalism’s decline seems to have been accelerated by the Black Death and its recurrences; the Black Death was a crisis in the history of feudalism.

English historians have long argued the role of the Black Death in ending English feudalism. For our purposes this was defined by the fourteenth century as the manorial relationship of landlord and unfree serf who is due protection, justice, and a share of the crop in return for labor in the lord’s demesne fields and on roads and such, customary payments, and the obligation not to run away.

Landlords had always used both free and serf labor, but the percentage of land worked by free peasants seems to have been steadily growing for a couple of centuries prior to 1348.

Studies of local conditions appear to indicate that the nonagricultural burdens on serf labor were also lightening before the Black Death in many places.

The weakness of the landlords’ position, despite the Statute of Laborers, and the failure of the English population to regenerate itself inevitably meant that negotiation rather than coercion would become the norm. The fifteenth century saw the withering away of most obligations and restrictions on peasant labor, though serfdom on a limited scale survived into the sixteenth century.

Those who demand, or need, these goods and services are willing to pay for them, and they pay more for them when their need or desire for them is great or when the supply of them is small.

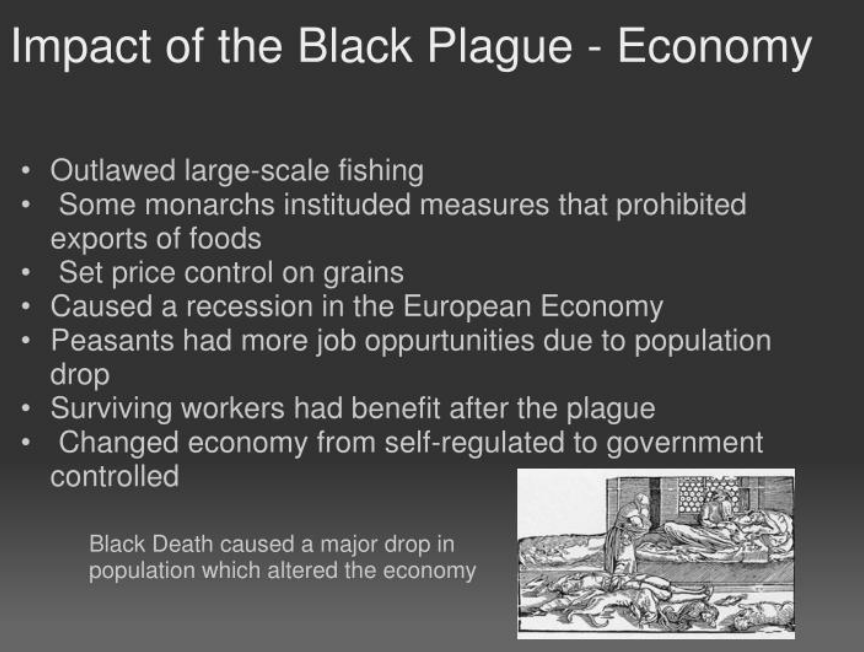

During the epidemic the people who needed and bought many types of goods and services died, and thus demand for many of these dropped, and prices dropped in the short run. There was an increase, however, in demand for other things, such as coffins, candle wax, medicines and herbs, cloth for shrouds, and the services of physicians, barber-surgeons, notaries, gravediggers, and priests. Prices or fees for these rose as they became scarcer, or as the professionals died off.

Gravediggers aside, the other professionals had a wealth of training and experience that disappeared when they died, and replacing them would not be easy or inexpensive. The same was true of people with other desired skills, such as carpenters, stonemasons, brewers (good ones), artists, teachers, shoemakers, and metalworkers. Not only were they not there to carry on their own work, they were also not there to teach a new generation their craft. Survivors could command high fees, prices, or wages. Cities, where such people tended to congregate, often made special efforts to bring survivors with these skills to their towns under very advantageous conditions, such as quick licensing for professionals, tax exemptions for certain types of merchants, or free lodging.

But this was only one type of “human capital.” In cities unskilled laborers also died and were in short supply, and they came to command rather higher wages than before the Plague. Some of these came from other towns or cities, but many moved in from the countryside around the city, leaving fields and crops behind and unattended. This certainly accounts for some of the rural-urban migration found throughout Europe from Dublin to Novgorod. This, of course, hurt the landlords, whose land and crops lay abandoned or underattended. In some places there was an excess of labor to begin with, or the death rates were minimal, and all of the jobs that needed doing were filled by the previously underemployed. In such places wages did not rise appreciably, nor did the prices of the produce or other goods supplied. But in most places labor became scarce and employers had to pay more for it, either by raising wages or lowering rents or by eliminating traditional services that land-bound peasants owed. Prices for grain and other food, which initially dropped as people died and demand fell, rose again as the supply fell (people ate it up) and the cost of supplying it rose. The tenants and laborers, rather than the landlords, however, were the ones to benefit from this situation.

Agricultural workers who were free to move about—and many who by law were not—followed the market incentives. In Italy landlords both old and new made sharecropping contracts with farmers, providing capital (land, seed, tools, housing) in exchange for their labor. In this mez-zadria system the tenant received a fixed percentage of the crop, and thus had a real incentive to work hard and produce as much as possible. In England peasant holdings tended to increase in size as there were fewer workers to tend to the same amount of cultivated land. Landlords had to make better deals with their tenant-farmers to convince them to stay. On large Church-controlled estates that were still essentially manorial, the religious landlords often reduced or eliminated the extra work or payments traditionally expected of peasants. Some even leased out to tenants their demesne land, which had traditionally been worked by peasants for the exclusive benefit of the landlord. In short, as long as labor was in relatively short supply, wages and other conditions for the laborer would be relatively good. Laborers also tended to profit from the redistribution of wealth that followed the initial drop in population. In villages poorer folks married slightly richer ones, and people combined their families and belongings and even landholdings; some moved into better housing, or acquired money, tools, or furnishings through inheritance or theft. On average, across Europe, the agricultural worker was better off financially and materially after the epidemic of 1348-50.

The landlord, however, lost by every concession. Higher prices for grain and other produce reflected their scarcity and higher cost of production, not greater demand, and certainly not higher profits for the landlord. Owners took less productive land out of production, and they shifted away from grain production. Especially in England and the Central Meseta in Spain landowners began to raise sheep, which were quite useful for both their wool and flesh, and which were also far less laborintensive than agriculture. The revenue from sheep grazing was not as high as that for most agricultural crops, but there was a profit to be had.

In England and Aragon the royal governments took steps to dampen these effects by restricting what an employer or landlord could offer in wages and benefits and forcing workers to accept the wages offered. Even the Church did this to regulate clerical incomes, amid claims that priests were charging excessively for their services. Edward III of England issued the Ordinance of Laborers in June 1349 in the immediate wake of the pestilence. “Employees” were choosing not to work, or to work for only “outrageous wages.” The Royal Government established 1346, “or five or six years earlier,” as the benchmark for appropriate wage levels. As historian R. C. Palmer summarized it, these were mechanisms to “force people to work, to diminish competition, and to moderate demands for higher wages.”15 Those who refused to work for such wages were to be imprisoned.

Enforcement of the Ordinance was left to the landlords and employers, who apparently did a poor job.

Two years later, in 1351, a more official Statute of Laborers was issued, which tightened some of the restrictions: hiring had to be done in the open with no secret agreements, and “without food or other bonus being asked, given, or taken.” Enforcement was taken out of the hands of the landowners themselves and placed in those of public officials, specifically “stewards, bailiffs, and constables,” who were responsible to the court of the Justice of the Peace. All who charged a fee for goods or services were to take an oath to charge as they had before the Plague. Oath-breakers were referred to as “rebels,” and prison terms were increased with subsequent breaches of the law—and their oaths.16 The charges brought could be as simple as the following: “they present that John Loue of High Easter is a common reaper and moves from place to place for excessive wages, and gets others to act in the same way against the statute.” It may not have been enforced vigorously everywhere, as some claim, but in Essex County in 1352, courts fined 7,556 people, of whom 20 percent were women, for breach of the Statute. As late as thirty-seven years later (1389), 791 fines were levied for such breaches in Essex.17

This kind of economic legislation by the English royal government was really new in two ways. First, it forced the king’s will right into the wallets of Englishmen, from the poorest laborers to wealthy merchants, for something other than taxes. It interfered in both guild and freemarket wage-setting. What the Ordinance and Statute really intruded on was the freedom of contract, and the intrusion was radical. Second, this is indicative of the slowly growing royal power and authority; the Crown would use the law to control society directly, not merely through the rapidly expiring feudal system. In so doing, the Crown allied itself not with local nobles, but with the lower, knightly class whose members increasingly served as sheriffs, bailiffs, and other Crown officers at the local level. This group emerged as the new gentry class, who became, in the words of one historian, “the self-interested architects of good order.” Landowners big and small tended to cease squabbling among themselves and found common cause against laborers and the new legal weapon with which to oppress them.18 To some—often disputed—extent, this led to the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. Despite the changes in the role and even structure of government, the Crown’s efforts were strictly conservative, and their purpose to preserve the social and economic status quo. Sumptuary laws restricting certain behaviors and styles of dress were issued in 1363 and meant to prevent lower classes from dressing or acting like their social betters. Though not well enforced, these did reinforce the line between classes and kept down the demand for—and price of—expensive cloth. Even beggars were soon to be regulated: the Statute of Cambridge (1388) sought to keep them from wandering and licensed those who needed to travel seeking work.19

Protests In U.S. To Coronavirus Restrictions Could Be Catalyst For Economic Change

Never Let A Good Crisis Go To Waste

Flag-waving protesters gathered outside government buildings in Michigan and Kentucky to voice their anger at stay-home orders.

Protesters in Lexington, Ky., had a different perspective, reportedly shouting loudly enough to be heard inside the Capitol. In Lansing, Mich., demonstrators took to the streets, snarling traffic as part of an “Operation Gridlock” rally.

Most of the protesters reportedly stayed in their cars, though others ventured onto the sidewalk and stood close together, disregarding social distancing.

“I support your right to free speech and I respect your opinions,” Whitmer said during a news conference. “I just urge you, don’t put yourself at risk and don’t put others at risk either … we know that this rally endangered people.”

The daily flood of statistics related to the COVID-19 pandemic, a compendium of numbers both promising and ominous, triggered starkly different reactions in different parts of the nation on Wednesday.

The situation in New York City suggests that making sense of coronavirus statistics can be difficult. This week, the city’s official death toll rose dramatically when health authorities began including people who may have had COVID-19 but died without being tested.

Updated: 4-17-2020

Fed Up With Staying Home, Some Americans Protest

Protests pop up from Virginia to Michigan as citizens, worried about their jobs and businesses, call for easing of coronavirus restrictions.

Americans impatient with continuing stay-at-home orders and other coronavirus-related restrictions have descended on several statehouses this week to clamor for governors to ease up and reopen the economy.

Some of the governors have rebuked the demonstrators, including in Kentucky, where Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear said during a briefing that reopening the state immediately “would absolutely kill people.”

The protests came as a record-shattering 22 million workers have sought unemployment benefits during a month of coronavirus-related shutdowns, and many employees and business owners have grown frustrated with forced shutdowns of businesses, especially those that don’t require large gatherings.

“Keeping people locked in their homes to save lives is going to collapse the economy, which is also going to cost lives,” Matt Seely, a volunteer with the Michigan Conservative Coalition, a group that helped organize a large protest in Lansing on Wednesday, said in an interview.

The events have ranged from the raucous rally in Lansing, which drew more than 3,000 people by police estimates, to a quiet picnic Thursday in Richmond, Va., that 40 people attended before authorities closed the gates to the square outside the state Capitol building.

In Raleigh, N.C., where about 100 people gathered Tuesday, police charged a 51-year-old woman with violating an executive order that limits gatherings to 10 people, a misdemeanor. The woman was given multiple opportunities to comply with the order “but chose not to do so,” said a spokesman for the state Department of Public Safety.

In Lansing, people protested Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s recent order expanding stay-at-home restrictions. They blocked traffic around the Capitol, and some protesters stood with guns a few feet from each other outside the building. Some chanted, “Lock her up!”

Ms. Whitmer had recently announced an extension of a state of emergency until the end of April. New measures include limiting the number of shoppers depending on the size of a store. One provision orders certain stores to close off some sections, including those for gardening supplies, saying they are nonessential, prompting the state’s greenhouse industry to say it will be devastated by the move.

The Facebook page for the protest, dubbed “Operation Gridlock,” listed as hosts the Michigan Conservative Coalition and Michigan Freedom Fund, a conservative advocacy group. Organizers of the protests said Ms. Whitmer’s action was a government overreach.

Tiffany Brown, a spokeswoman for Ms. Whitmer, said the governor supports the right to protest but that participants shouldn’t put themselves or others at risk.

“It is disappointing to see people congregating without masks, and without practicing social distancing,” she said in a statement. “This kind of activity will put more people at risk, and it could mean that more people will die.”

The Michigan Freedom Fund, which has backing from the DeVos family, wasn’t the main organizer, but did spend $250 advertising the event on Facebook, said Tony Daunt, the group’s executive director, in an interview Thursday. Mr. Daunt said his group was listed as a host on the Facebook page because it had advertised the event, but that the Michigan Conservative Coalition was the lead organizer.

The DeVos family, which includes Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, are prominent conservative donors. They have donated to the group, but weren’t involved with the protest held Wednesday, said Nick Wasmiller, a spokesman for the family. Most demonstrators stayed in their vehicles, but about 150 people were on foot, the Michigan State Police said. One attendee, a 45-year-old man, was arrested for simple assault against another protester.

Mr. Seely said the organizers of the protest urged attendees to practice social distancing. “It is only this group of jerks that descended on the steps to the Capitol and on the lawn,” he said.

In Kentucky, demonstrators carried homemade signs and American flags while chanting slogans like “Facts over fear” and “We want to work” outside the state Capitol in Frankfort.

Erika Calihan said she helped organize Wednesday’s protest by posting on Facebook that she planned to take her children to the Capitol. She said many people practiced social distancing, though there were also family members who clustered together.

Ms. Calihan, who estimated hundreds of people turned out, said Mr. Beshear, by keeping the state largely shut down, “is looking out for a very small percentage of Kentuckians, rather than looking out for all Kentuckians.”

“We’re not sure why we can’t operate just like the big businesses and put in safety precautions, and thereby potentially protect people and at the same time make a living,” said Ms. Calihan, whose husband is a small-business owner.

“If people are frightened,” she said, “they can choose to stay at home.”

Protesters’ chants and a horn could be heard as Mr. Beshear updated the public on the pandemic, including news that seven more state residents had died of Covid-19, the disease caused by the new coronavirus.

“Everybody should be able to express their opinion,” the governor said. “They believe we should reopen Kentucky immediately, right now. Folks, that would kill people.”

Thursday’s picnic in Richmond was organized by three groups including Reopen Virginia, which was formed Sunday and grew out of Facebook discussions, said organizer Markie Kelly. The group’s Facebook page has 19,000 members with 10,000 requests pending, she said.

“It is one thing to say there is a virus out there and it has put this amount of people in the hospital and this amount of people have died from it. It is another thing to say ‘stay home, do not leave your house, you cannot work if you’re this type of business,’” said Ms. Kelly, a 31-year-old stay-at-home mother.

Democratic Gov. Ralph Northam on Wednesday said he would extend until May 8 an emergency order that bans crowds of more than 10 people; closes recreation, entertainment and personal-care businesses; and limits restaurants to takeout and delivery.

“Gov. Northam will continue to make decisions based in science, data and public health,” a spokeswoman for the governor said.

A Virginia Capitol Police spokesman said police were alarmed by a Facebook notice for the picnic because it said “hugging, closeness and sharing of dishes is encouraged.”

Ms. Kelly defended the choice of words. “We didn’t say you have to do this, but yeah, if people want to hug each other, let them do it,” she said.

After about 40 people had arrived, police closed the gate to Capitol Square, said the police spokesman, Joe Macenka.

“We then went over to the group and asked them if they could please try and maintain safe social-distancing practice,” he said. “They did that, so we left them alone at that point.”

Updated: 4-15-2021

How Amsterdam Recovered From A Deadly Outbreak — In 1665

Following an epidemic of bubonic plague that wiped out 10% of the population, Amsterdam’s economy quickly rebounded, a new study shows.

For two years in the mid-1600s, Amsterdam experienced a shock that may now seem familiar.

The city was ravaged by a deadly epidemic of bubonic plague. As graveyards in poorer districts started to fill, the wealthy scattered to their country houses, while those that remained did their best to keep healthy through social distancing. Sick people were banned from markets, inns and churches, while infected houses warned off visitors with a sign hung outside — a bunch of straw tied with three bands.

These measures may have helped, but they weren’t enough to stop the plague. By the time the epidemic petered out in 1665, the disease had claimed 24,000 Amsterdammers — around 10% of the population.

In percentage terms, Amsterdam’s brush with the plague was more deadly than anything coronavirus has yet caused. But the experiences of the 17th century still uncomfortably echo those of many cities in the 21st: a highly contagious disease stalling the economy, highlighting social inequality, restricting travel and obligating citizens to curb their interactions with each other.

As some parts of the world tentatively enter the coronavirus recovery period, a new study examining Amsterdam’s post-epidemic return to normality might also foreshadow what contemporary cities can expect in the near future.

By looking at the 17th century housing market, the study finds that prices did indeed dip sharply as the economy floundered during the plague seasons. As death rates fell, however, things stabilized with surprising speed, followed by a period of urban innovation that ultimately had positive effects.

The study, which also examines the economic effect of cholera in 19th century Paris, complicates the vision of how cities have been affected historically by epidemics. It shows that rather than being waylaid, cities can actually prosper after serious health crises. They do so, the study suggests, partly because the shock can force through changes that create better living conditions more conducive to prosperity.

How Amsterdam Came Back

Written by Amsterdam Business School’s Marc Francke and Erasmus School of Economics’ Matthijs Korevaar, and published in the Journal of Urban Economics, the study suggests that Amsterdam swiftly recovered its pre-epidemic population — and its economy — by attracting migrants.

According to the researchers, the lessons behind the rebound of this growing metropolis might best be applied to developing cities and countries with stark societal inequalities and limited government support, rather than the contemporary Netherlands.

While construction work, along with much other economic activity, ground to a halt during the plague’s worst months, it soon resumed. The city was not just witness to this revival — it actively stimulated it, using a tool that might now seem too obvious to note but at the time was innovative. City records suggest that, for the first time, Amsterdam allowed landlords to buy its land parcels not using state loans.

“I jokingly say that the only difference between now and the 17th century is hand sanitizer and data tracking.”

The city may have been keen to stimulate the market because, just before the epidemic struck, it went through one of the most ambitious transformations in its history. By the 1660s, Amsterdam was booming as a global trading hub, with so many citizens involved in commerce that up to 50% of space in the city’s canal houses was used for warehousing goods. But while a thriving economy meant Amsterdam needed more space to grow, finding that space was difficult.

The city was built on a marshy, maritime site where, before any construction was possible, new land needed to be first drained and raised, then prepared with a base of wooden pilings, driven into the soggy soil to provide a foundation sturdy enough to take the weight of a house.

On top of this, the period’s constant wars meant that any new land had to be protected by strong city walls. Expanding the city thus took a lot of coordination and financing, happening in four major bursts of activity between 1585 and 1663. The city’s largest expansion, which required 100,000 wooden pilings to support its new walls alone, was completed in the year the plague arrived, and land was released for sale.

The plague likely came to Amsterdam by boat (and then spread via the bites of fleas carried by rats), but Amsterdammers didn’t know this at the time and fell back on the familiar Miasma Theory. Circulating since antiquity, this was the idea that disease was spread through stinking corrupted air, rising either from rotting matter or from inherently unhealthy spots such as marshes.

Previous plague epidemics had also taught people that keeping people apart could help — the reason why during the plague’s peak, England forced Dutch ships bound for London into a 30-day quarantine in a remote creek.

Even though the epidemic was severe, these attempts at isolation, and the fear of miasma, may indeed have saved lives. The best way to avoid smells is to avoid proximity, and foul-smelling places are indeed often rife with bacteria. While observance and enforcement may have been very slack, what is striking about Amsterdam’s measures is how familiar they are in the wake of Covid-19.

“The irony is that the forms of containment we use today are the same ones we used in the 1600s,” says Ed Cohen, author of “A Body Worth Defending: Immunity, Biopolitics and the Apotheosis of the Modern Body,” in an interview. “I jokingly say that the only difference between now and the 17th century is hand sanitizer and data tracking.”

An Omen In The Sky

Less familiar, perhaps, was a fear expressed by Amsterdammers that the cosmos itself was providing warnings of their fate and using the disease as a tool to punish them. When a “fiery ball” (probably a comet) appeared over the city in the winter of 1664, people interpreted it as a sign of the epidemic’s severity.

This was in keeping with contemporary practice: Earlier in the century a beached whale and even an unusually large bird that had perched overnight on an Amsterdam church’s roof had been taken as omens that past crises had been a form of divine judgement.

Pragmatically, the plague also meant that the city released its new land parcels for sale just as the the economy was in epidemic-induced stasis. To make sure the land sold once public health had improved, the city employed a tool it hadn’t previously tried: mortgages. Previously, buyers of city land had to pay its whole cost upfront — a system that worked for only a tiny proportion of citizens who actually had the means to buy property at the time.

By allowing loans, the city expanded its pool of potential buyers considerably, albeit still restricting ownership to a small elite. Within 10 years of the epidemic, land prices stabilized and new buildings started to appear in the city’s new extension.

At the same time, large-scale migration helped fuel this revival. While the period lacks firm population data, the historical consensus is that Amsterdam’s population rose during every five-year period of the 17th century — including those covering plague years.

The city’s “mortality penalty” wasn’t enough to deter migrants from the economic opportunities it offered, according to study co-author Korevaar. “Mortality in Amsterdam was always higher than fertility in those years so the city could only grow by migration,” he said in an interview.

The swift stabilization noted in Francke and Korevaar’s study shouldn’t be taken as evidence that the epidemic had been painless for the city, or that Amsterdam’s recovery was necessarily rock-solid. While home prices dropped sharply for a short period during the plague, rents fell by a much smaller amount.

In a period when most people rented their homes and very few owned, this suggests that a population undergoing severe, if temporary, economic shock didn’t have enough bargaining power or flexibility to reduce their housing costs.

There was one exception: Records for the time showed that rents on mansions plummeted, because Amsterdam’s wealthiest people took advantage of the city’s growth to move out of rentals and build new homes on and around the new Herengracht canal, still one of the city’s most exclusive addresses today.

Amsterdam’s expansion, meanwhile, did ultimately prove to be an overreach. While the city weathered the pandemic, it was still floored by the so-called “disaster year” less than a decade later. Invaded by France in 1672 , the Dutch Republic flooded the land surrounding Amsterdam, making it too swampy to march through but still too shallow-watered for boats.

This protected the city but smothered its economy, ending its building boom and, along with the war, bringing the Dutch Golden Age to an end. Without buyers for the new land within the walls, parts of Amsterdam’s last extension remained unbuilt as late as the 19th century.

But even this turn of events benefited the city in the long run. Unable to find buyers for the land, the city leased plots in the new district for 20 years, banning permanent buildings in hope of being able to sell the land more profitably at a later date. The result was that Amsterdam gained a new quarter with more greenery and open space, filled with market gardens and places of entertainment as well as the site of a new Botanical Garden. To this day, this area is somewhat greener and less dense than the rest of inner Amsterdam.

These adaptations have left their mark, even if they weren’t necessarily as sweeping as the changes in French and American cities after major 19th century disease outbreaks, which will be examined in subsequent articles.

They still follow a pattern repeated in those later public health crises: a nasty and relatively short epidemic followed by a recovery that set the scene for both an economic revival and — inadvertently — an urban fabric that was altogether greener and more spacious. They also suggest that even epidemics aren’t enough to prevent people from gravitating to where there are most opportunities: major cities.

There had been public protests in Ohio and North Carolina earlier in the week. Economic Effects Of The,Economic Effects Of The,Economic Effects Of The,Economic Effects Of The,Economic Effects Of The,Economic Effects Of The,Economic Effects Of The,Economic Effects Of The,Economic Effects Of The,Economic Effects Of The,Economic Effects Of The,Economic Effects Of The,Economic Effects Of The,Economic Effects Of The,Economic Effects Of The,Economic Effects Of The,Economic Effects Of The,Economic Effects Of The,Economic Effects Of The,Economic Effects Of The,Economic Effects Of The,Economic Effects Of The

Go back

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.