Companies View Labor Shortage As Reason To Fully Automate Wherever Possible (#GotBitcoin)

Companies weigh new technologies to strengthen their shared services, customer relationship management. Companies View Labor Shortage As Reason To Fully Automate Wherever Possible (#GotBitcoin)

Finance chiefs are considering hastening investments in automation initiatives to better manage their companies’ finances and operations despite facing revenue declines stemming from the coronavirus pandemic.

While many finance executives are slashing costs to weather the downturn, some view investments in technology as essential to better equip newly remote finance teams or strengthen other parts of the business.

“For many, the crisis is accelerating the vision that they’ve already had for a long time,” said Michael Heric, a partner in consulting firm Bain & Co.’s technology, media and telecommunications practices. “While it could have taken years or even decades to make that shift, I think you’re going to see it much faster now.”

Eastman Chemical Co. expects recent digital investments into customer relationship management automation—which helps companies track engagement with customers—to pay off within the finance team and across the company as many employees work from home, Willie McLain, CFO of the Kingsport, Tenn.-based specialty chemical company, said in an interview.

Eastman is on track for $20 million to $40 million in cost savings this year stemming from recent digital and other productivity investments, Mr. McLain said at a conference on March 10.

Huntsman Corp., a The Woodlands, Texas-based chemical manufacturer, wants to use automation to make its shared services—centralized processes ranging from accounting to human resources—more efficient.

Sean Douglas, the company’s finance chief, said it is too early to pinpoint specific opportunities but noted that Huntsman’s need for automation remains on the company’s agenda during the pandemic. “We’re a little bit still on the beginning side of that path,” Mr. Douglas said. “There’s lots that can be done in this company by automating.”

For many companies, a finance department’s core transactional processes—such as closing the books, accounts payable, customer billing and processing supplier invoices—aren’t fully automated. Companies with shared-services employees who aren’t able to work from home are more likely to make a big push during the pandemic to automate processes, executives say.

“If you can’t send a bill to a customer or you can’t send a check to an employee, all of those operations basically halt,” said Mr. Heric of Bain. “You’ll struggle to close the books if there’s a lot of manual things that are going on.”

Fallout from the pandemic could change the pace of automation adoption, the execution of which has been slow for many companies, according to Bain. The proportion of companies ramping up globally on automation technologies, such as conversational artificial intelligence, robotic process automation, optical character recognition and low code automation, will at least double over the next two years, according a Bain survey of nearly 800 executives, one-third of which work in finance.

Many companies will have no choice but to employ automation to maintain their businesses in a bid to cut down on labor costs and other expenses. Automation of business processes could eliminate 20% to 25% of jobs world-wide by the end of the decade, Bain said.

Companies with call centers and customer-help centers, in particular, are moving rapidly to adjust their operations for a remote-work environment. Some businesses are developing bot-based answer systems that try to siphon off some calls to automated systems and prioritize calls that require person-to-person interaction.

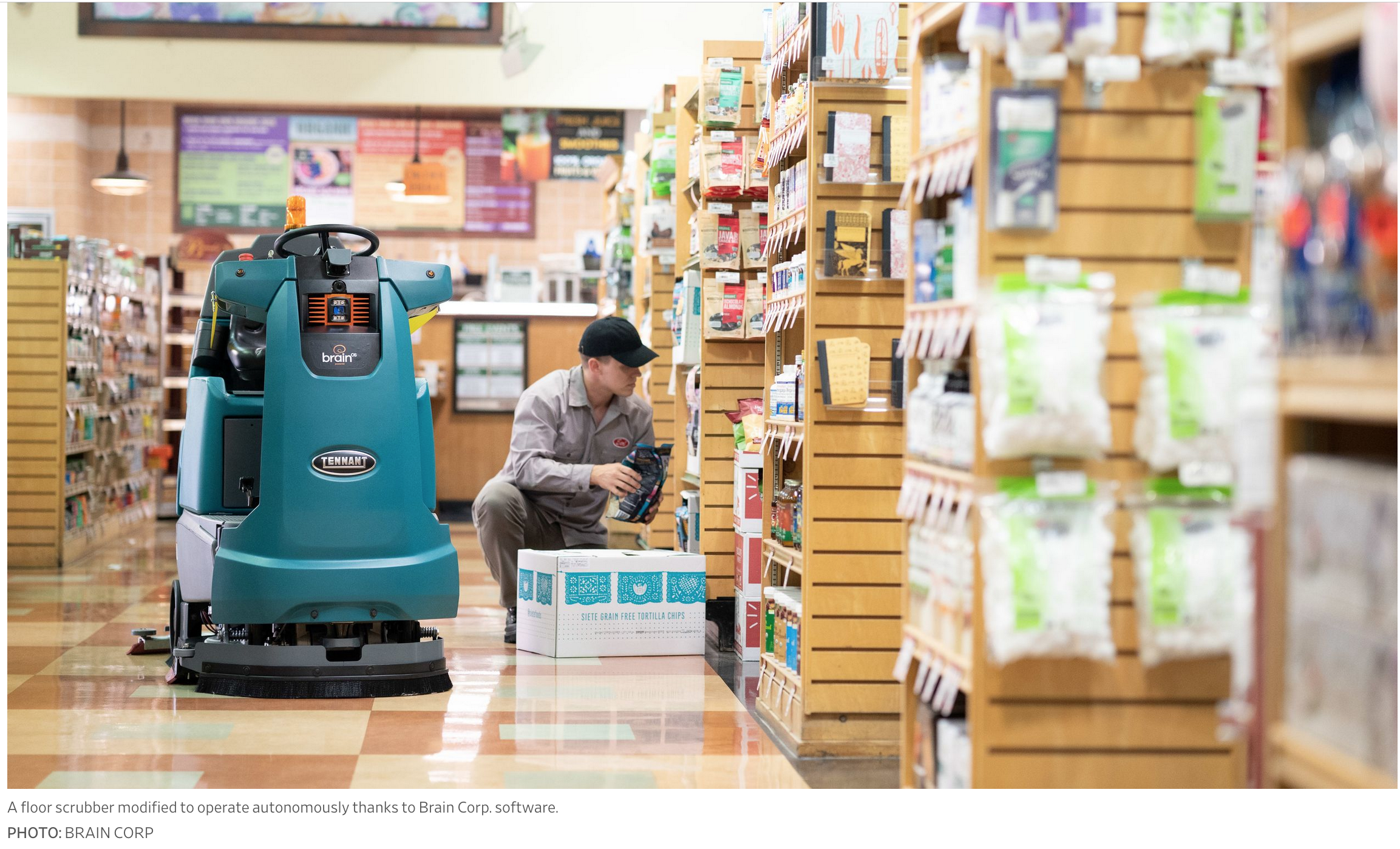

Meanwhile, hospitals, grocery stores and other essential services are deploying software and hardware robots in the fight against the outbreak. A global survey recently conducted by Pulse, an online research hub for chief information officers at large companies, found that half of roughly 50 businesses in its network are using some form of robotics or automation to help front-line workers cope with the pandemic.

Updated: 4-13-2020

One Side Effect Of Coronavirus: Robots Will Take Our Jobs At An Even Faster Rate

About 50 million jobs could be automated just in ‘essential’ industries.

American workers are locked into their homes, avoiding contact with anyone and everything touched by others. Social contacts and supply chains are disrupted by coronavirus and the COVID-19 illness it causes. In the workplace, there is a solution that addresses both problems simultaneously: new colleagues immune to pandemics and ready to replace American workers.

More robots.

While many bosses are discovering a new willingness to let at least some employees permanently work remotely, no one seems to be talking about this 800-pound gorilla that could be even more disruptive to jobs and could happen even faster than the already quite scary forecasts of only a few years ago.

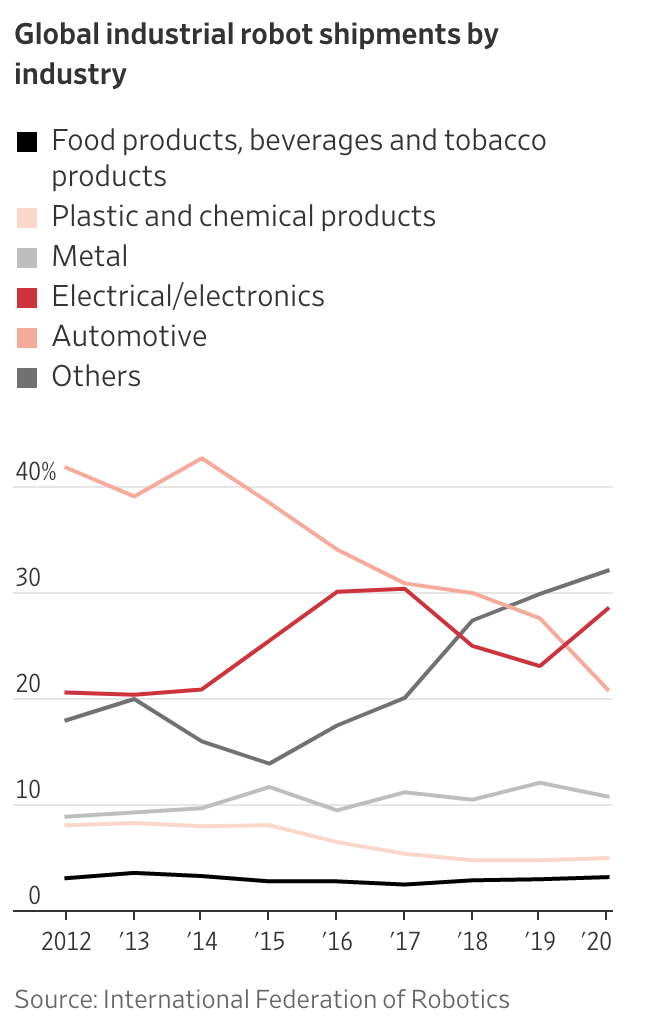

Even more automation with ever-more-powerful robots and computers can help immunize the economy against future pandemics. This has implications in particular for two industry groups that have come into focus recently: essential industries, including large parts of the manufacturing supply chain, and industries with direct customer contact, also called high-touch industries. Note that these categories overlap: for example, about half of the high-touch industries are considered essential.

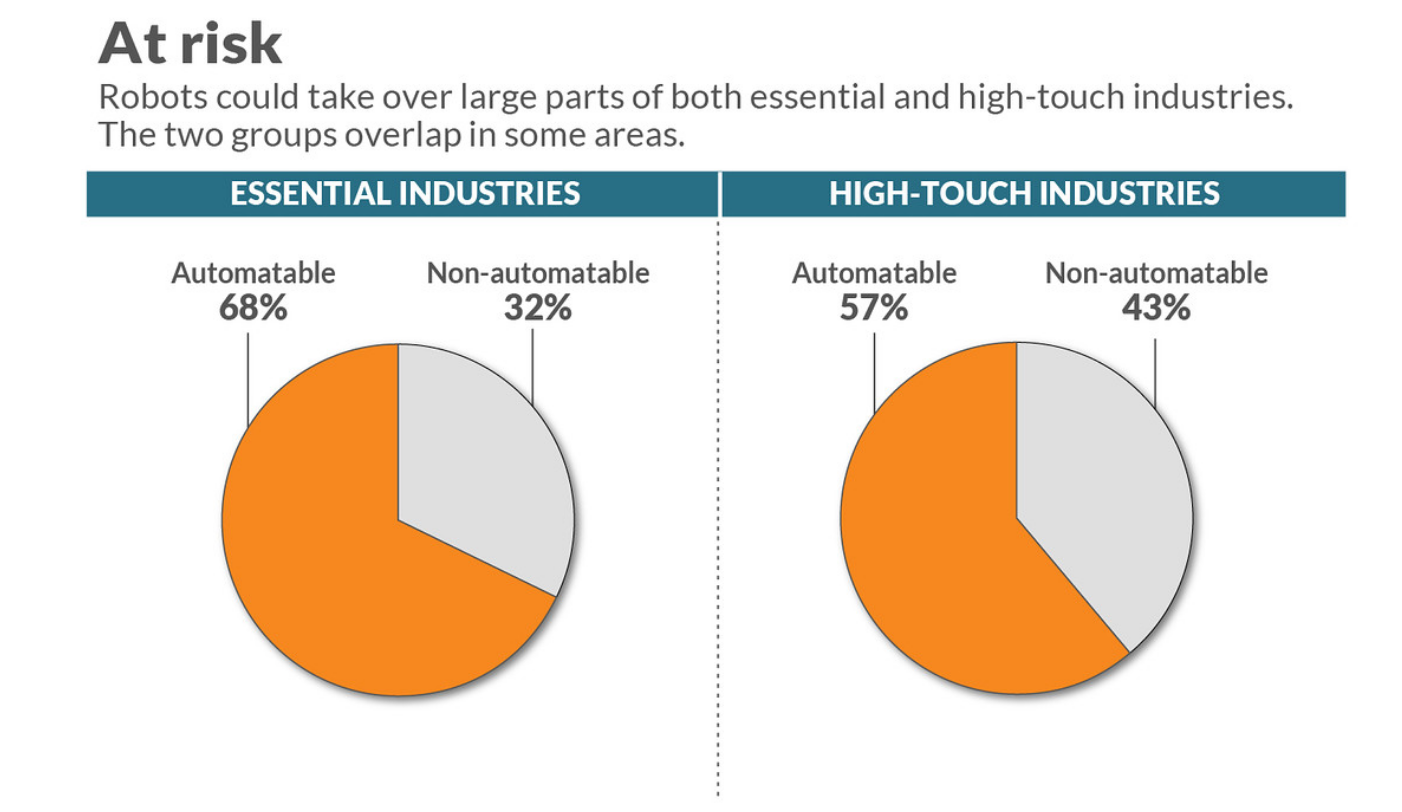

A widely cited 2017 study out of Oxford University provides data to calculate the share of jobs that can technically be automated in the next 15 years. Using this study, I calculated employment and wage risks for those industries. About 54% of all jobs in the U.S. are in industries classified as essential by the Department of Homeland Security, and 67% of these jobs — corresponding to 52% of wages — are susceptible to automation.

So it is the low-wage jobs, like retail and warehouse jobs, that face the highest risk. In comparison, high-touch industries account for 46% of jobs (with some overlap with essential industries), and 57% of those jobs are vulnerable.

Recall what social distance requires: don’t meet, don’t touch. That particularly affects some high-touch industries like restaurants, retail and recreation. According to the same Oxford study, we should have the technology to automate 86% of restaurant jobs, 76% of retail jobs, and 59% of recreation jobs by 2035.

Two years ago, I argued that many of the jobs with direct customer contact would likely not be automated as customers value personal contact. However, COVID-19 is a human tragedy, and research has shown that those affected severely will permanently change their behavior.

This means that certain customers at any time and almost all customers at certain times will value avoiding personal contact. That changes the mix of preferences and restaurant offers substantially.

As especially large companies consider rehiring, they will think twice whether a particular job can be done by a machine.

Robots are getting more capable by the hour and cheaper by the minute. Cost advantages are going to be reinforced by risk perception. Advantage robot.

Here’s What’s Coming

Some of the technology is already in advanced testing stages or readily available. Once Amazon.com AMZN, 0.00% starts licensing its Amazon Go technology, retail as we know it today will be limited to small stores — if they can survive.

Ford Motor’s delivery van prototype includes a robot that brings packages from the vehicle to the door – and targets a multi-billion dollar market. ABB, has already installed more than 400,000 industrial robots — by some estimates replacing more than 2 million workers.

Robot baristas as well as Starbucks’s self-service kiosks and intelligent coffee-stations may offer early substitution opportunities for those who want to avoid direct contact. This is not the end of the barista — but self-service stations will not only be used by germophobes, so once they move from office areas to public spaces, they will reduce regular barista-operated coffee shops.

What I expected to see in three to five years may now show up as quickly in fast-food restaurants as much as on factory floors.

The environment for automation has never been better: ultra-low interest rates, large sectors with low value-added per worker with repetitive tasks, exponential growth in patents involving artificial intelligence, low corporate tax rates, and venture capital firms that turned their interest toward process automation (namely robots and machines) all point toward accelerated use of automation technology.

With about 50 million jobs in essential industries that could be automated and wages of more than $1.5 trillion every year, the incentives to automate are huge.

Yes, capital spending will take a while to recover, but once it does, it will focus on technologies that protect essential industries, including supply chains, against the next virus attack. It also needs to satisfy the wants of those customers who prefer social-distanced service experiences. What I expected to see in three to five years may now show up as quickly in fast-food restaurants as much as on factory floors right when this recovery begins.

The coronavirus triggered demand and supply shocks. It will also accelerate and alter a technology shock that has been in the making for more than a decade. Firms that do not reduce vulnerability to future pandemics may find themselves at a disadvantage. The same applies to workers who need to upgrade their skill sets to match those new requirements.

We need to train our workforce for the full range of 21st century skills: expertise in human-machine interactions like machine operation and maintenance; social competence and communication proficiency; creativity; critical thinking; and complex problem solving.

The workforce that companies need during and after the recovery will likely look quite different from the workforce they sent on the dole.

Updated: 5-16-2020

Some companies, however, are already planning their retreat from traditional offices while a deadly virus spreads across the globe. OpenText’s elimination of more than half its offices will result in 2,000 of the company’s 15,000-person workforce working from home permanently across back-office roles, client relations and technology support, according to Chief Executive Mark Barrenechea. The company makes information-management software. “At this scale this is certainly being driven by the pandemic,” he said.

To keep the company’s culture intact while its people are physically apart, OpenText is conducting online happy hours, virtual chess tournaments and game nights while encouraging employees to use videoconferencing backgrounds that showcase their personalities. “I stepped back and said ‘OK, it’s working for us,’” Mr. Barrenechea said. The enterprise information-management software company is in the process of determining which office leases to let expire and which to renegotiate with landlords, he said.

In Silicon Valley, where company culture was always a cornerstone of startup life, some of the biggest companies were the first to embrace the concept of working remotely through the pandemic. Now they are also re-imagining how workers will congregate in the future.

Twitter Chief Executive Jack Dorsey notified employees Tuesday that they would be able to work from home even after the pandemic is over, with exceptions for some jobs that can’t be done remotely. Twitter doesn’t plan to close or shrink any of its offices.

Since the pandemic started, the social media company has been hosting virtual events to foster interaction between employees. Twitter’s chief human resources officer, Jennifer Christie, said more people engage in the meetings now that they are virtual. They also create a level playing field. “Everyone has the same experience,” Ms. Christie said.

In the last decade, corporations have tried to reduce their office space by squeezing in as many employees as possible on their floors, but social-distancing rules make that increasingly difficult. Now, many companies say they will allow more people to work from home and restructure office floors to allow for greater spacing. Companies typically spend 2% to 3% of their revenues on office space, according to real-estate analyst Green Street Advisors.

Updated: 5-16-2020

When It’s Time To Go Back To The Office, Will It Still Be There?

As companies prepare for employees to return, they are asking whether a traditional headquarters is still necessary. The workplace will likely never be the same again.

Someday the coronavirus pandemic will release its grip on our lives and we will return to the workplace. The question is: Will there be an office to go back to when this is all over?

The changes the business world is considering offer a radical rethinking of a place that is central to corporate life. There will likely be fewer offices in the center of big cities, more hybrid schedules that allow workers to stay home part of the week and more elbow room as companies free up space for social distancing. Smaller satellite offices could also pop up in less-expensive locations as the workforce becomes less centralized.

In San Francisco, Twitter Inc. TWTR 1.54% notified employees this week that most of them could continue to work from home indefinitely. Canadian information-technology provider OpenText Corp. OTEX 0.63% expects to eliminate more than half of its 120 offices globally. And Skift Inc., a New York media company, is giving up its Manhattan headquarters when its lease expires in July.

The modifications could have a profound impact on millions of workers who defined their work lives around a daily trip into “the office,” with consequences that aren’t yet known. Some employees in coastal cities might be able to take their existing salaries to places with a lower cost of living. But that may also mean those workers can be easily replaced by someone offshore, where costs are even lower.

Employees would gain flexibility, but they might miss the temporary respite from domestic responsibilities and exchanging ideas in more impromptu ways. Big companies would save on real estate costs, but they might struggle to outbid smaller companies for the best talent if traditional office perks like free food and bike storage are no longer as essential as they once were.

The zeal for a new definition of the traditional office is driven in part by the shrinking economy, as companies look for new ways to cut costs during a downturn that is expected to be the worst since the Great Depression. Many executives also point to the success of an unprecedented work-from-home experiment, and how little productivity appears to have been impacted after millions of employees in technology, media, finance and other industries have been forced to work remotely for months.

“I mean, if you’d said three months ago that 90% of our employees will be working from home and the firm would be functioning fine, I’d say that is a test I’m not prepared to take because the downside of being wrong on that is massive,” said Morgan Stanley Chief Executive James Gorman in mid-April on the bank’s earnings call.

The biggest loser in the rise of a reimagined office could be the commercial real-estate market and the big institutional investors that have invested heavily in it. Pension funds, insurance companies and other institutions have spent billions of dollars to buy big city office towers in cities. They are depending on continued tenant demand that now looks poised to slow.

This doesn’t mean urban offices are disappearing anytime soon. Leases are hard to tear up, and few companies want to ditch the office altogether. There were also other periods where the end of the center-city office building was wrongly predicted, beginning in the latter half of the 20th century as some companies decamped to suburban office parks and following the shock of 9/11. Each time the centralized office building proved to be surprisingly resilient.

Many who are attached to the real-estate industry still say there is no substitute to having all employees under one roof. “One of the most important aspects of American business over the last couple of decades has been the establishment of firmwide cultures—the idea that having the right firmwide culture can make your company successful,” said Will Silverman, a managing director at real-estate investment banking firm Eastdil Secured LLC. “I just don’t know how you establish a culture among people who are only together a few days a week.”

Space Race

Companies are re-evaluating their real estate needs in the era of Covid-19, asking whether a decentralized workforce might cut costs. Achieving that goal might be easier in certain cities where you can get more space for your money and enough excess square footage is available to let employees spread out safely.

Some companies, however, are already planning their retreat from traditional offices while a deadly virus spreads across the globe. OpenText’s elimination of more than half its offices will result in 2,000 of the company’s 15,000-person workforce working from home permanently across back-office roles, client relations and technology support, according to Chief Executive Mark Barrenechea. The company makes information-management software. “At this scale this is certainly being driven by the pandemic,” he said.

To keep the company’s culture intact while its people are physically apart, OpenText is conducting online happy hours, virtual chess tournaments and game nights while encouraging employees to use videoconferencing backgrounds that showcase their personalities. “I stepped back and said ‘OK, it’s working for us,’” Mr. Barrenechea said. The enterprise information-management software company is in the process of determining which office leases to let expire and which to renegotiate with landlords, he said.

In Silicon Valley, where company culture was always a cornerstone of startup life, some of the biggest companies were the first to embrace the concept of working remotely through the pandemic. Now they are also re-imagining how workers will congregate in the future.

Twitter Chief Executive Jack Dorsey notified employees Tuesday that they would be able to work from home even after the pandemic is over, with exceptions for some jobs that can’t be done remotely. Twitter doesn’t plan to close or shrink any of its offices.

Since the pandemic started, the social media company has been hosting virtual events to foster interaction between employees. Twitter’s chief human resources officer, Jennifer Christie, said more people engage in the meetings now that they are virtual. They also create a level playing field. “Everyone has the same experience,” Ms. Christie said.

In the last decade, corporations have tried to reduce their office space by squeezing in as many employees as possible on their floors, but social-distancing rules make that increasingly difficult. Now, many companies say they will allow more people to work from home and restructure office floors to allow for greater spacing. Companies typically spend 2% to 3% of their revenues on office space, according to real-estate analyst Green Street Advisors.

Updated: 5-27-2020

Tech Workers Fear Their Jobs Will Be Automated In Wake of Coronavirus

Concern about automation among tech workers exceeds that in other industries, KPMG says.

Technology-sector employees are particularly worried about being replaced by automation, including tools used by employers to cope with the impact of the coronavirus pandemic, according to KPMG LLP.

An estimated 67% of workers at U.S. technology companies are concerned about losing their jobs to digital capabilities powered by artificial intelligence, machine learning and robotic software, KPMG said in a report Friday. That compares with 44% among workers at companies outside the tech sector.

Beyond automation, 70% of tech-sector workers are worried about having their jobs eliminated as a result of the economic fallout from the crisis, compared with 57% of workers employed by companies in other industries.

The results are based on a survey of 1,000 full-time and part-time workers across a range of industries, including 223 employed in the tech sector, the firm said. The survey was conducted in April.

Technology workers’ fears could be a harbinger for the broader labor market in the aftermath of the pandemic, as tech company trends often spread across the corporate world over time, said KPMG tech-industry practice leader Tim Zanni.

“Workers in the tech industry are closer to the technology and thus have a unique understanding, more so than other industries, of technology and its capabilities,” said Mr. Zanni.

He said workers at technology firms see emerging digital capabilities in early stages of development and are more likely to be thinking of the impact of these tools on their jobs.

U.S. technology firms shed a record 112,000 jobs in April, erasing total job gains over the past year, according to an analysis of Labor Department data by IT trade group CompTIA.

The nation’s tech sector employs roughly 6 million workers, including tech professionals, as well as people in sales, marketing, human resources and other positions. Together they account for an estimated 4% of the total U.S. workforce, CompTIA says.

Jobs in the area of artificial intelligence, an increasingly key element of automation, are proving to be more resilient.

Technology market research firm International Data Corp. estimates that AI jobs globally could increase by as much as 16% this year, reaching more than 950,000. The gains are being driven by strong demand for AI capabilities as companies contend with the aftermath of the pandemic, IDC says.

It estimates that 40% of companies world-wide are increasing their use of automation as a response to the pandemic, often following the lead of tech firms involved in the development of these capabilities.

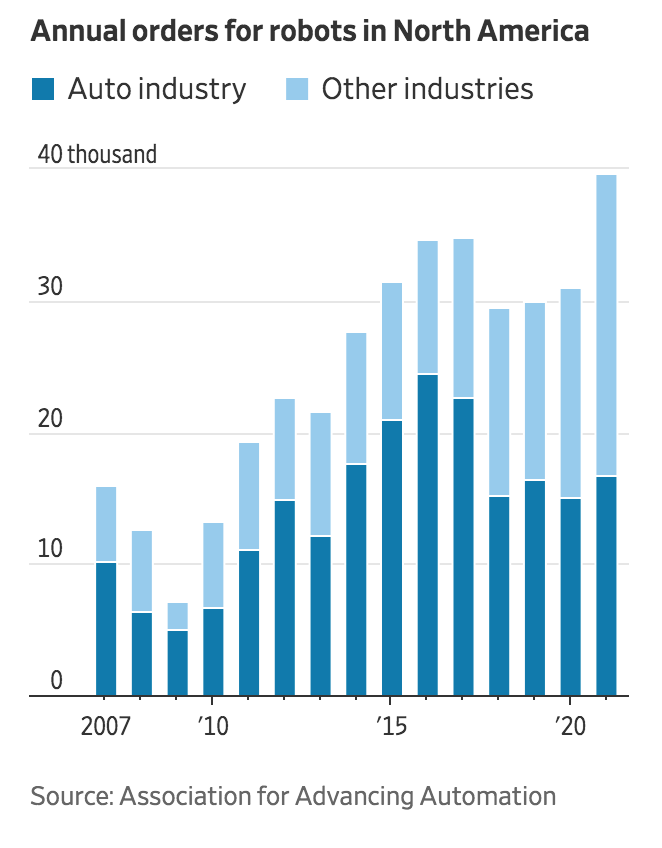

Automation displaced workers at companies in a range of sectors in the aftermath of the 2007-2009 financial crisis, according to a report by tech-industry research firm Forrester Research Inc. The trend slowed down the labor-market recovery in the wake of the crisis, with overall employment taking nearly two years to rebound, the report said.

“We believe that hyper automation is where the market is headed,” said Daniel Dines, chief executive of robotic process automation maker UiPath Inc. The New York-based company is already adding roughly 10 corporate customers a day, a faster clip than 2019, Mr. Dines said.

He believes AI-enabled automation will create new higher-tiered jobs, as software tools take over mundane, repetitive tasks, such as processing paperwork or managing emails, and enable employees to be more productive in other areas.

Updated: 7-9-2020

Tyson Turns To Robot Butchers, Spurred by Coronavirus Outbreaks

The pandemic is speeding meatpackers’ shift from human meat cutters to automated ones, but machines can’t yet match people’s ability.

Deboning livestock and slicing up chickens has long been hands-on labor. Low-paid workers using knives and saws work on carcasses moving steadily down production lines. It is labor-intensive and dangerous work.

Those factory floors have been especially conducive to spreading coronavirus. In April and May, more than 17,300 meat and poultry processing workers in 29 states were infected and 91 died, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Plant shutdowns reduced U.S. beef and pork production by more than one-third in late April.

Meatpackers in response spent hundreds of millions of dollars on safety equipment such as personal protective gear, thermal scanners and workplace partitions, and they boosted workers’ pay to encourage them to stay on the job.

They also are searching for a longer-term solution. That quest is playing out in a former truck-maintenance shop near the Springdale, Ark., headquarters of meatpacking giant Tyson Foods Inc. There, company engineers and scientists are pushing into robotics, a development the industry has been slow to embrace and has struggled to adopt.

The team, including designers who once worked in the auto industry, are developing an automated deboning system destined to handle some of the roughly 39 million chickens slaughtered, plucked and sliced up each week in Tyson plants.

Tyson, the biggest U.S. meat company by sales, currently relies on about 122,000 employees to churn out about one in every 5 pounds of chicken, beef and pork produced in the country. The work at Tyson’s Manufacturing Automation Center, which opened last August, is speeding the shift from human meat cutters to robotic butchers.

Over the past three years, Tyson has invested about $500 million in technology and automation. Chief Executive Noel White said those efforts likely would increase in the aftermath of the pandemic.

The Covid-19 pandemic has been a debacle for the $213 billion U.S. meat industry. For the first time in memory for some Americans, there wasn’t enough meat to go around. Reduced production forced grocery giants such as Kroger Co., Costco Wholesale Corp. and Albertsons Cos. to limit how much fresh meat shoppers could buy in some stores. Fast-food chain Wendy’s had to tell customers that some restaurants couldn’t serve hamburgers.

Now automation projects are racing ahead, said Decker Walker, a managing director with Boston Consulting Group, or BCG, who works with meatpackers. “Everybody’s thinking about it, and it’s going to increase,” he said.

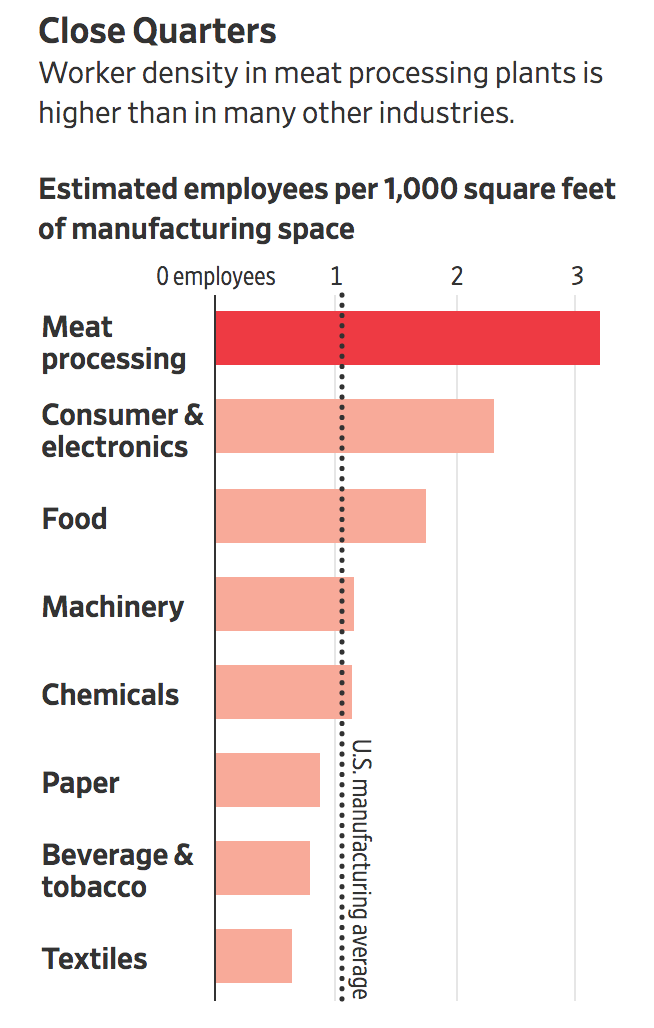

Automation has transformed jobs such as car assembly, stock trading and farming. Meat processors, though, employ 3.2 workers per 1,000 square feet of manufacturing space, three times the national average for manufacturers, according to data compiled by BCG. While U.S. manufacturing worker density overall has held steady over the past five years, in meat plants it has increased, according to the firm.

Executives of Tyson and other meat giants, including JBS USA Holdings Inc. and Cargill Inc., say that is because robots can’t yet match humans’ ability to disassemble animal carcasses that subtly differ in size and shape. While some robots, such as automated “back saw” cutters that split hog carcasses along the spinal column, labor alongside humans in plants, the finer cutting, such as trimming fat, for now largely remains in the hands of human workers, many of them immigrants.

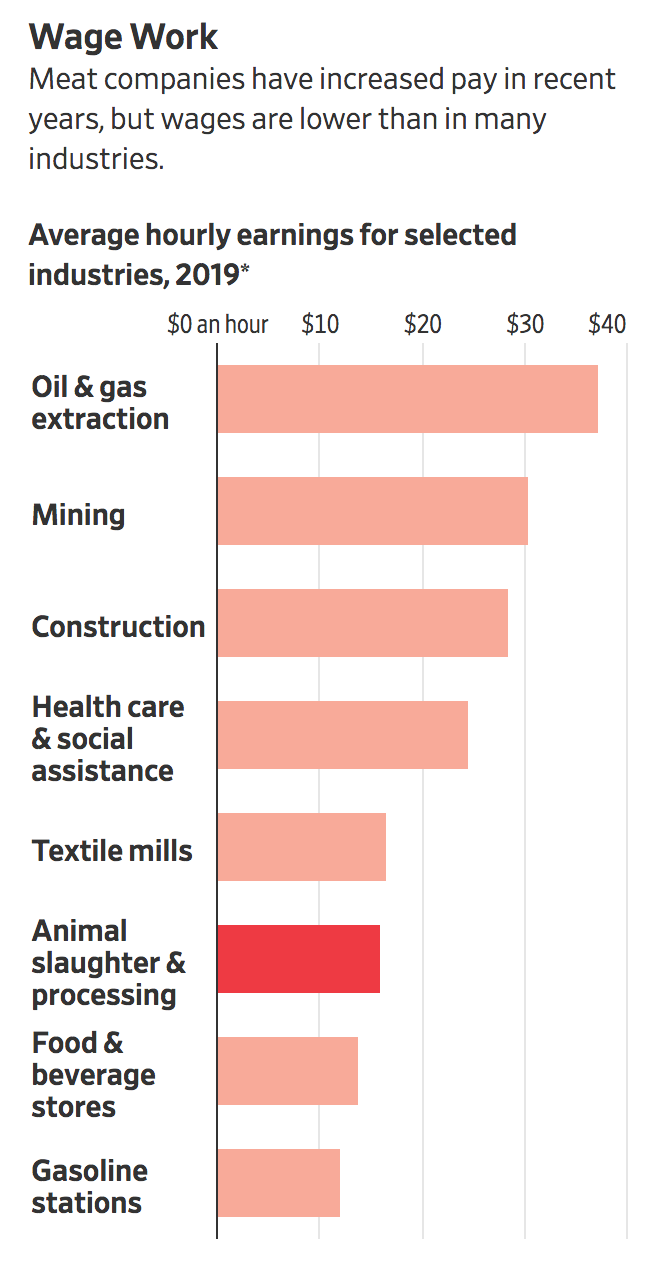

Workers in the animal slaughtering and processing industry, including some not working on processing lines, were paid an average $15.92 an hour in 2019, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

A skilled loin boner can carve a cut of meat like filet mignon without leaving too many scraps on the bone, which have to be turned into lower-value products like finely textured beef, a low-cost trimming used in hamburger meat, or dog food, said Mark Lauritsen, an international vice president for the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union, which represents many meatpacking workers. For beef companies, that’s the difference between meat selling wholesale at $5 a pound and 19 cents a pound, he said.

“Labor is still cheaper, and humans can do those skilled jobs much better than machines can,” he said.

Meat companies have raised hourly pay in recent years in response to a tightening U.S. labor market. Adjusted for inflation, though, average meat-processing wages have fallen 50% since 1975, according to University of Missouri history professor Chris Deutsch.

Meat industry officials say the cost of living is lower in rural areas, where many plants now are located, and that more experienced workers are paid more. Tyson said its average hourly pay for U.S. employees was $15.77 last year, and JBS said its average hourly worker makes more than $20 an hour.

While meat processing overall has grown safer in recent years, it remains one of the more hazardous jobs in the U.S. economy, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. With 4.3 workplace injuries or illnesses per 100 full-time workers in 2018, the industry’s rate is nearly 40% higher than the national average for all industries, surpassing logging, mining and construction.

Animal slaughter and processing facilities logged 23,500 nonfatal injuries and illnesses in 2018, the latest year for which data is available, though such data is marred by underreporting, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

Bashar Abdulrazzaq, an Iraqi refugee, said he lasted less than a year at Tyson’s Perry, Iowa, pork plant. After an eight-hour shift carving meat from the backs of hogs, Mr. Abdulrazzaq said, his fingers often were locked in place and he had to pry open his hand to begin work the following morning. Lower back pain, caused by moving heavy carcasses, ultimately drove him from the job, he said.

“Doing that for eight hours a day nonstop,” he said, “it’s not human.”

Tyson said it has invested in ergonomics and other changes to make jobs less physically demanding, including automated carcass split saws and spare rib pullers at the Perry plant. It said the position Mr. Abdulrazzaq held has been eliminated after the company installed a less labor-intensive production process.

Roughly 585,000 people work in U.S. meatpacking plants. Plant workers cycle in and out of jobs rapidly, with annual turnover in meat plants ranging from 40% to 70%, according to Boston Consulting Group, versus an overall 31% average for manufacturers.

Problems keeping plants staffed predate the pandemic. Plants struggle to draw enough workers to small towns in the South and Midwest that house most of the industry’s plants. Refugees, who can legally work in the U.S., and immigrants, including those can’t, make up a significant portion of the workforce.

Difficulties recruiting workers have been an impediment to expanding plants and building new ones, executives said. “The biggest push that we have in terms of automation over the last five years is because of the availability of labor in the U.S.,” said Andre Nogueira, chief executive of JBS JBSAY -2.59% USA, a unit of Brazilian meat company JBS SA.

Covid-19 compounded that problem. As the pandemic spread in March and April, hundreds of workers stayed home from plant jobs across the country, according to meat company and union officials. Meat companies responded by erecting partitions between workstations and break room lunch tables, installing automated temperature scanners and distributing masks and gloves.

While weekly U.S. meat production has recovered, labor challenges continue to force some meat processors to focus on high-volume, less-processed cuts, meaning fewer boneless products in supermarket meat cases, said Will Sawyer, an economist with agricultural lender CoBank.

Meatpacking companies have tested automated cutting systems before, with mixed results. Some projects were abandoned after wasting too much high-value meat, industry officials said. Poultry processors have successfully automated some steps, such as the job of “gut snatchers,” who removed birds’ entrails, partly because chickens tend to vary less in size than do cattle and hogs.

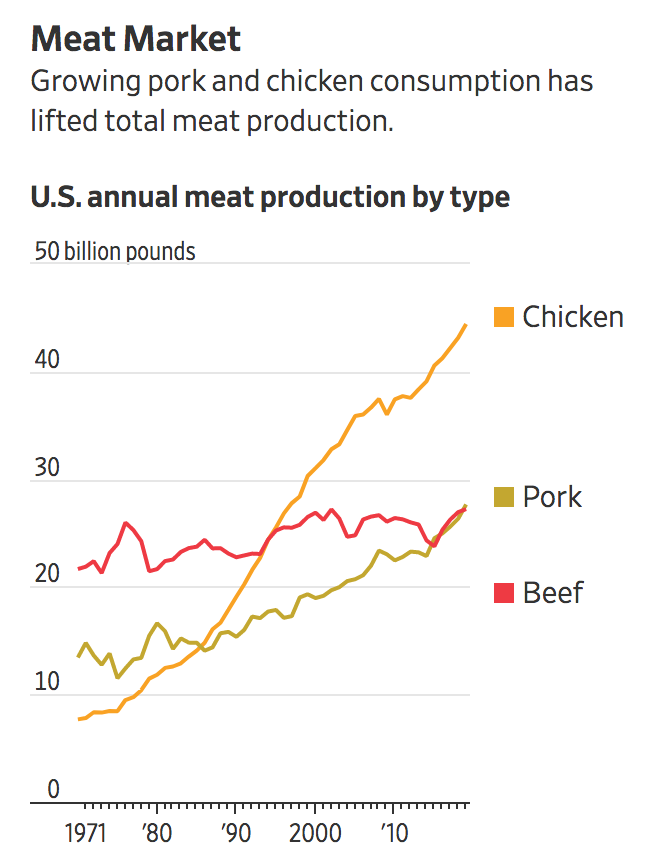

A growing consumer appetite for products such as deboned chicken and skinless meat has required more people on processing lines. Decades ago, most Americans bought whole chickens. McDonald’s Corp. ’s introduction of Chicken McNuggets in the 1980s changed that. Roughly 85% of chicken eaten in the U.S. today is parts like breasts and wings or products such as chicken fingers, according to the National Chicken Council.

JBS, the world’s biggest meat company by sales, has been working for years to automate portions of its poultry and livestock operations around the world, said Mr. Nogueira. JBS in 2015 paid $42 million for a controlling stake in Scott Technology Ltd., a New Zealand-based robotics company that has automated lamb processing.

Scott’s system works partly because much lamb meat is sold with bones still in it, said Mr. Nogueira. A Scott-developed robotic knife arm for deboning still can’t match humans, he said, though such systems are starting to catch up.

At Pilgrim’s Pride Corp., PPC -2.39% the second-biggest U.S. chicken processor and majority owned by JBS, deboning machines now trail humans by only 1% to 1.5%, in terms of meat yield per chicken.

“They are much closer to what the person can do than seven years ago,” Mr. Nogueira said. Technology and automation are part of the $1 billion in capital expenditures JBS USA has planned for 2020. “One day we will be there, but we are not there yet,” he said.

Dean Banks spent years directing automation projects at technology and health-care companies, most recently at X, the unit of Google parent Alphabet Inc. set up to solve some of the world’s most vexing problems. He joined Tyson’s board of directors in 2017 and became president in December.

Teaching robots to cut and sort meat, which involves soft material and variability, he said, “it’s the most challenging operational environment you can find.” The low temperatures at meat plants, kept cool for food-safety reasons, pose more hurdles for robotics, as does blood splatter, industry officials said.

Inside Tyson’s Arkansas robotics lab earlier this year, one room included a robot with a mechanical arm mounted inside a glass box, resembling an arcade crane game. With the push of a button, the robot’s arm dumped three cups of multicolored beads onto a tray, then rapidly grabbed each one and sorted them by color in less than 30 seconds.

Tyson’s technicians are trying to teach machines to recognize and quickly adjust to differences in meat coloration and shape, part of what executives say makes meat processing harder for machines than, say, assembling cars from uniform, manufactured components.

In meat plants, “our parts are infinitely variable,” said Marty Linn, previously the principle engineer of robotics for General Motors, who joined Tyson last year to help direct its automation efforts.

European meat plants have incorporated more automation than their U.S. counterparts, using lasers and optical eyes to read cuts of meat on a conveyor belt and send them to different departments to be packed, weighed and shipped. The technology means a single worker in plants in Sweden, Denmark and France does the work of eight or nine workers in U.S. plants, though the operations run at a slower pace, said Mr. Lauritsen, the union official.

Mr. Lauritsen said boosting automation at U.S. meatpacking plants needs to be done thoughtfully so job losses don’t devastate the communities they sustain.

“If you take half the jobs out of Worthington, Minn., and Denison, Iowa, you take away 2,000 jobs and the payrolls that come with them,” he said, referring to two towns with meatpacking plants. “You’ve crippled those communities.”

Tyson’s Mr. Banks said that workers are in no danger of being replaced broadly by robots soon. Workers whose jobs are automated can be moved into other, open positions, so layoffs aren’t needed, he said. Robots can improve employee retention, he said, by making jobs more skilled and less strenuous.

Mr. Banks said that the technology is needed to relieve bottlenecks in Tyson’s plants, where lack of skilled workers in critical jobs can slow overall production. To solve one such problem, he said, Tyson designed a water-jet cutting system capable of carving up chicken breasts more precisely than humans can. Many Tyson chicken plants now are using the system to develop new products that they couldn’t make using human labor, he said.

Automation “is something we think is going to be revolutionary for our business,” said Doug Foreman, Tyson’s director of manufacturing technology, who has designed meat-cutting equipment for decades. “We are on the cusp of a significant rollout.”

Updated: 8-9-2020

As E-Commerce Booms, Robots Pick Up Human Slack

The Covid-19 pandemic and the explosion in demand for home-delivered goods means FedEx and other shippers are pushing the limits of what robotic arms can do.

Sue, Randall, Colin and Bobby are four of the most reliable workers at the FedEx Express FDX 6.55% World Hub in Memphis, Tenn., according to their supervisors. Each clocks eight hours a day of steady work, sorting around 1,300 packages an hour from bins onto a conveyor—four hours on the day shift and another four at night.

They almost never take breaks, but since they’re still learning on the job, they do regularly call on coworkers in the facility for help. Sue, for instance, has had some trouble with the soft bags in which clothing is typically shipped.

The four workers are actually 260-pound industrial robot arms. Manufactured by Waukegan, Ill.-based Yaskawa America, 6506 -1.66% they are equipped with computer vision and artificial intelligence from San Antonio-based Plus One Robotics.

They work only about half as fast as skilled humans in the same roles, but they are quickly becoming an important part of the chain of machines and people that keep packages flowing through the world’s largest air freight facility, says Aaron Prather, senior advisor of the technology research and planning team at FedEx Express.

While companies such as FedEx Corp., Deutsche Post DHL Group, United Parcel Service Inc. and Amazon. com Inc. have long relied on billions of dollars worth of automation to get packages to customers quickly—from conveyors that divert packages down one path or another to guided vehicles that shuttle about entire shelves of goods—these robot arms are something different.

They’re the first arms of their kind to ever appear in a FedEx facility, and among the earliest examples of the day-to-day use of this technology anywhere in the world.

These robots typify an important and growing trend in automation in general, and robotics in particular. What’s new here is that existing machines are getting both “eyes” and “brains” that allow them to sense and respond. For robots, this generally means the addition of cameras not so different from the ones in cellphones, which perceive visible light.

Computer vision can also include sensors that use other technologies in order to perceive depth. Meanwhile the “brains” of the robot are built with artificial intelligence, generally some form of machine learning, a broad category that enables everything from Alexa’s understanding of our voices to systems that can teach themselves how to beat humans at board games.

This AI gives existing robots and other machines a level of adaptability not before seen. In fact, the new flexibility and intelligence make them able, for the first time, to replace humans in some of the most common jobs in warehousing and logistics.

It’s not as if these robots are about to steal all the jobs in these industries, however. For now, they’re mostly filling vacancies created by surging demand and, where possible, giving humans a chance for promotion. For the foreseeable future, humans will prove more adaptable as work needs change.

Proponents argue that bringing robots into these roles is necessary for at least three reasons.

First, the explosion of e-commerce means an explosion in the volume of packages shipped to homes. About 87 billion parcels were shipped worldwide in 2018—that’s 40 a year to every person in America—and this volume will more than double by 2025, according to Pitney Bowes, best known for its postage meters.

The number has grown much faster than expected during the pandemic. UPS said in the quarter ending in June, the volume of packages shipped from businesses to homes surged by 65% from a year before.

Second, with new and ongoing stay-at-home orders due to increasing Covid-19 cases, the availability of workers even for essential businesses is reduced. Third, the need for social distancing within warehouses and other logistics facilities means automation can play a role in helping workers do their jobs without being directly adjacent to one another.

Despite widespread unemployment, companies in the logistics industry are still finding it hard to hire people fast enough. FedEx’s air hub in Memphis currently has 500 job openings, says Mr. Prather.

Even before the pandemic, warehouses and sorting centers had a labor crunch because many of the jobs in the industry are both physically demanding and dull, leading to high turnover and challenges with recruitment, he adds.

“This has never been about, ‘Can a robot beat a human?’” says Erik Nieves, founder of Plus One Robotics. “This is about how they’re a thousand people short every night in Memphis, and there is no alternative.”

Some of the humans FedEx and others do hire could take on higher-level supervisory roles, with less risk of injury, expanding the burgeoning sector of robot tech support.

FedEx currently has four of these robots at its Memphis facility, but the company estimates one human could tend up to eight of them, jumping in only when they have a problem they can’t solve on their own, like when packages get caught in a conveyor and block a sensor.

Meanwhile, at the Plus One command center in San Antonio, people are on call to help guide the robot remotely when it encounters a package it can’t identify or some other logical difficulty, even before anyone is needed to intervene on site.

The AI that powers these robot arms is learning all the time, but there are always situations that trip it up and require human intervention.

No amount of AI, at least of the sort that exists now, can handle every possible “edge case,” those unexpected situations which are individually rare but quite common when considered all together. This galaxy of edge cases is a major barrier to fully autonomous AI systems.

For any attempts to automate e-commerce, “the challenge is that humans are incredible,” says Bruce Leak, founding partner at venture capital firm Playground Global. “Twenty-five years ago Amazon didn’t exist,” he adds, “and today they have more than a million direct employees.

People are trainable, flexible, resilient and intelligent, and automation and robots aren’t any of those things.” (Amazon currently has 876,000 employees, says a spokeswoman for the company.)

Mr. Leak is an investor in RightHand Robotics, based in Somerville, Mass., which makes a similar AI-powered, camera-equipped picking system. Its technology is used by a handful of companies, including Japan’s Paltac, a wholesaler of consumer packaged goods.

Many other startups have recently received funding or announced deals to sell robotic picking systems, including Covariant, Osaro, Dexterity, Pickle Robot Company, XYZ Robotics, Fizyr, Mujin and Dorabot.

In addition, established systems integrators like Daifuku, Dematic and Honeywell bring together technologies from these startups and established makers of industrial robots, including Yaskawa, Universal Robots, ABB, Kuka, Fanuc and others.

Despite this flurry of activity, the overwhelming majority of industrial robot arms in the world are still the “dumb” kind: They repeat the same action over and over again—for example welding the same parts together repeatedly on an automobile production line. In warehouses where e-commerce orders are filled, most automation consists of various sorting technologies.

Amazon itself has yet to move robot arms into the human job of picking and sorting, publicly at least. While the company is an avid producer and consumer of robots that move shelves and help sort packages, Amazon still uses humans to accomplish the task of taking goods off of shelves or out of bins and putting them into other bins or on conveyors.

The company’s enormous and quickly changing inventory still defeats even the best combination of AI, computer vision and gripper, says Brad Porter, vice president at Amazon Robotics.

“There will always be a need for people to support the automation in our fulfillment centers,” he adds. “We see new technologies increasing safety, speeding up delivery times, and adding efficiencies within our network; we re-invest those efficiency savings in new services for customers that lead to the creation of new jobs.”

While this technology is great for sorting packages, as at FedEx, and dealing with a limited range of items, as at Paltac, it’s possible that the holy grail of picking technology—a robot that can handle the same variety as a human—will remain out of reach for a long time, in the same way we have yet to create an autonomous vehicle that can handle the same variety of road situations a human can.

One reason for the sudden popularity of robots, says Mr. Nieves, is they are a way to do the same job as a human without completely re-engineering the inside of a warehouse.

“These robot arms make a lot of sense,” says FedEx’s Mr. Prather, “because we can’t just tear down the building and say, ‘OK, everyone wait a year until we have a new one.’”

But when one of these big players does build a new facility, using the sort of technology that’s only become available in the past few years, things are different. For example, many of the warehouses where packages are sorted for FedEx’s ground service are newer than its Memphis air hub.

These facilities are so completely automated with, for instance, smart conveyors known as “shoe sorters,” humans only touch packages when they’re brought into these buildings on trucks, and when they exit them on different trucks, says Ted Dengel, managing director of operations technology and innovation at FedEx Ground.

So until and unless every factory and fulfillment center in the world is re-designed to run “dark,” that is, without the involvement of any human labor, these uniquely challenging tasks will benefit from the human brain and body—or at least a reasonable facsimile.

Updated: 8-12-2020

Companies Step Up Distribution Automation Under Pandemic Strains

Robots are helping speed the flow of goods while workers maintain social distance in warehousing and fulfillment operations.

A handful of warehouse robots helped American Eagle Outfitters Inc. cope with a flood of online orders during coronavirus lockdowns as consumers loaded digital shopping carts with hoodies, leggings and loungewear.

Now the company is stepping up its use of automation. The company is installing 26 more piece-picking robots at its main U.S. distribution centers, making it the latest company to deepen its logistics technology investments as the coronavirus pandemic upends sales channels and supply chains.

The kiosk-size units from robotics provider Kindred Systems Inc. use mechanical arms, computer vision and artificial intelligence to sort through piles of apparel.

They provide steady labor to help workers organize orders and reduce crowding on the warehouse floor, where the company said one human can manage multiple robots instead of standing next to other associates.

“During non-Covid times, if demand grew by 50% I would go hire 300 more people,” said Shekar Natarajan, senior vice president of global inventory and supply chain logistics for American Eagle Outfitters, which said e-commerce sales for its American Eagle and Aerie brands shot up after stores closed in March.

Now, Mr. Natarajan said, “It’s really tough because you’re also trying to make sure you’re keeping the associates safe… You cannot actually bring in 1,000 to 2,000 untrained people into the distribution facility and maintain safe working conditions.”

Upheaval from the coronavirus pandemic is pushing more companies to consider automating distribution and fulfillment, as the consumer rush to online shopping and social distancing practices within warehouse operations add to the challenges in strained logistics networks.

Although fulfillment operations still rely largely on human labor, companies have been incorporating more technology in recent years as they seek to boost output and handle swings in demand more efficiently.

Covid-19 is accelerating that shift.

More than half of warehouse operators responding to a recent survey by Honeywell Intelligrated, Honeywell International Inc.’s warehouse automation business, said they were more willing to invest in automation as a result of the pandemic.

E-commerce companies showed the biggest shift, with 66% saying they were more willing to do so, followed by food and beverage companies and logistics providers, at 59% and 55%, respectively.

About half of the respondents who had invested in automation said it was helpful for the business during the pandemic, with many citing their ability to continue operating with fewer staff on-site as a benefit, according to the survey, which polled 434 U.S.-based professionals in April and May.

The pandemic has highlighted the importance of operating flexibility that some newer types of automation can provide, said Thomas Boykin, a leader of Deloitte’s supply-chain practice.

“The ability to scale up quickly or scale down without laying off workers or reconfiguring workers has become more important,” Mr. Boykin said.

About 39% of manufacturing and supply chain professionals said their organizations use robotics and automation, according to a survey by MHI, an industry group representing makers of material handling and logistics equipment and technology.

Adoption is expected to reach 58% in the next one to two years, and 73% in the next three to five years, the survey found.

Technology providers say smaller companies previously on the sidelines are now making serious inquiries about automation, especially for lower-cost options such as collaborative robots that work alongside humans.

Other businesses are looking into automated micro-fulfillment systems that fit in the back of stores or in small urban distribution centers to help grocers and retailers fill online orders more quickly.

The number of inbound sales calls to IAM Robotics Inc., a company in the Pittsburgh area that makes autonomous mobile robots, has more than doubled this year, said Chief Executive Tom Galluzzo.

“Our clients are saying, ‘We’ve underbuilt for buy online, pick up in store.’ It’s expanded the range of folks looking for automation,” Mr. Galluzzo said. “It’s not just Fortune 500 companies.”

Companies that already had logistics automation in place when the coronavirus pandemic hit are also ramping up technology investments.

A few years ago FreshDirect LLC, a New York-based online grocer serving regional markets in the Northeast, spent millions on a sprawling, highly automated distribution center in the Bronx with more than 640,000 square feet of usable space. Demand for FreshDirect’s home-delivery slots skyrocketed during the pandemic, particularly in suburban markets outside the company’s usual core base of urban customers.

Now the company plans to install micro-fulfillment technology from U.S.-Israeli robotics startup Fabric at a smaller facility outside Washington, D.C., so it can speed groceries to customers in that region in as little as two hours, augmenting its next-day delivery there.

“As we grow over time, particularly in the suburbs, we’re going to want to be as close to the customer as we can,” Chief Executive David McInerney said. “The velocity going through these micro-fulfillment centers will be a lot higher.”

Still, economic uncertainty has some businesses hitting the pause button on spending, including investment in automation.

The pandemic is expected to depress global industrial robot shipments this year, market-research firm Interact Analysis said in a recent report. Companies that delayed automation projects this year will likely advance those plans in 2021, the report said, although revenue and shipments for providers of collaborative robots is still expected to grow by double digits this year.

North Reading, Mass.-based equipment-maker Teradyne Inc. said the pandemic depressed second-quarter revenue in its industrial automation segment because of global manufacturing weakness. But subsidiaries specializing in mobile robots notched sales gains compared with the same period in 2019.

The company expects sales to pick up in the third quarter and grow by 20% to 35% over time, Chief Financial Officer Sanjay Mehta said in a July 22 earnings call.

“We’re seeing a lot of activity in this—plant managers and decision makers looking to harden their production lines and social distance,” he said.

Updated: 3-24-2021

KFC, Taco Bell, Pizza Hut To Start Taking Orders via Text

Parent Yum Brands acquires Israeli startup that developed the software after testing technology in 900 restaurants.

KFC-owner Yum Brands Inc. is buying an Israeli-based startup that helps customers order food to go via text, a strategy executives hope will fuel sales as people shift away from fast food and return to full-service restaurants.

Yum is set to use software made by Tictuk Technologies Ltd., a private tech firm founded in 2016, for fast-food ordering through text as well as social-media apps such as Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp, the companies said. The technology turns around a customer’s order in as fast as 60 seconds, said Clay Johnson, Yum’s chief digital and technology officer.

Sales at Yum, which is based in Louisville, Ky., have risen since testing Tictuk’s technology in roughly 900 KFC, Pizza Hut and Taco Bell restaurants in 35 countries, the company said. Financial terms of the deal weren’t disclosed.

As America’s restaurant industry begins to reopen, fast-food companies are searching for ways to keep customers they gained while sit-down restaurants were shut. Many chains are investing in online-order pickup systems to try to make them an appealing option as consumers eat out more.

Online sales have boomed for companies spanning retailers to auto dealers during the pandemic. Restaurants had started setting up digital ordering mechanisms before the crisis, and have quickly sought to do more since.

Chipotle Inc., which logged nearly half of its sales digitally in the past three months of 2020, is building online pickup drive-through lanes at its stores. McDonald’s Corp. is spending a billion dollars on technological systems annually as it seeks to get more customers to order through its mobile app and from drive-throughs with digital screens.

Food delivery and pizza companies, meanwhile, are also trying to keep up big surges in sales during the pandemic through digital loyalty programs.

Brands have focused more on developing their own mobile apps, said Andrew Robbins, CEO of Paytronix Systems, Inc., a technology firm working with restaurants and convenience stores. Voice-based ordering could provide more payoff, as built properly it would be easier and faster to use than texting, Mr. Robbins said.

Among digital orders processed by Paytronix, 84% come from the web and 15% from mobile apps.

Tictuk doesn’t currently offer voice ordering, but it is something Yum intends to explore with its new division, the fast-food company said.

Tictuk—which can be used for pickup, delivery or dine-in orders—is Yum’s second technology deal in a month. Yum also acquired Kvantum Inc., a Texas-based company that crunches consumer data to determine the best way to spend marketing money by area. That deal is expected to close later this year.

Yum executives say they are focused on tech deals after a surge in online ordering during the Covid-19 pandemic. The company made $17 billion in online sales last year, a roughly 45% increase from 2019 as dining rooms closed amid the crisis and customers ordered food for delivery or pickup instead.

Online orders tend to come with bigger sales and require less labor as they reduce customer interaction with workers, Yum Chief Financial Officer Chris Turner said. “Our digital transactions are a win on just about every dimension from an economic standpoint,” Mr. Turner said in an interview.

Tictuk and its 15 employees will become a business unit within Yum and work on additional tech projects, the companies said.

Updated: 4-27-2021

DoorDash Allows Restaurants To Choose Commissions In Post-Pandemic Future

New tiered system is effort to appease restaurants over fees they were forced to accept during health crisis.

DoorDash Inc. is changing the way it charges restaurants to deliver their food, marking a shift in a business model that has met with increasing pushback over fees as the company positions itself for a post-pandemic world.

Starting Tuesday, San Francisco-based DoorDash said it would allow restaurants to pick from three rates, setting commissions at 15%, 25% or 30% of every order. DoorDash said it would offer varying degrees of marketing and product support based on the different fee levels.

Previously, restaurants didn’t have a choice. Delivery apps charged restaurants a cut of every order and set the rate. Some bigger chains used their scale to negotiate commissions as low as 15%. Many small restaurants paid as much as 30% of every order.

Orders on major delivery apps boomed as shelter-in-place orders kept consumers at home and restaurant dining rooms closed. DoorDash now controls nearly half of the U.S. food-delivery market, up from one-third before the pandemic.

Small-business owners bristled over the fees, blaming the apps for squeezing their already thin margins as the coronavirus pandemic raged. Regulators in several cities, including New York, San Francisco and Seattle, stepped in to cap what the apps could charge restaurants as a result. Lawmakers in Chicago are considering whether to extend the city’s commission caps on apps, which expired earlier this month.

As the health crisis wanes, keeping restaurants happy is crucial if DoorDash wants to maintain its lead. Tuesday’s changes are among the early steps the company is taking as it prepares for dining rooms to reopen and delivery volume to slow after a year of exponential growth.

“This is us listening to our merchant partners and making adjustments,” DoorDash Chief Operating Officer Christopher Payne said at a virtual event announcing the changes. “Essentially we’ve been learning together about what restaurants need and testing our way into what the next phase of pricing should be.

DoorDash also lowered the commission on food that is picked up to 6% from 15%.

The food-delivery industry has made temporary concessions before. Grubhub Inc. deferred commissions during the early months of the pandemic. DoorDash and Uber Technologies Inc.’s Eats waived commissions for small businesses in March, but returned to charging them a few months later.

Hurt by high commissions, some restaurant owners signed up for lesser-known services offering more favorable rates during the health crisis; a few others tried to redirect business to their own websites and redeployed idled staffers as delivery drivers. Big chains are investing in building high-tech pickup services.

DoorDash’s effort to rework the commission structure comes with a few caveats. The company plans to offset lower restaurant commissions by raising delivery fees for consumers. For instance, consumers would pay a $4.99 delivery fee, on average, for restaurants that choose the lowest commission. By contrast, consumers would pay a delivery fee of $1.99, on average, for restaurants that choose the highest commission.

“Would that negatively impact order volume? Yes it will,” Mr. Payne said. “Delivery is a very cost-intensive service,” Mr. Payne said, “so we need to blend the economics on the consumer side and merchant side in order to make the overall system economics work.”

The company said part of the calculus over the new framework is that the additional costs to consumers mean the company won’t have to adjust driver pay.

The National Restaurant Association said it has been working with delivery companies to improve their relationships with restaurants during the pandemic, and DoorDash’s move helps to create more transparency and options for food businesses.

“We continue to see improvements,” said Mike Whatley, the trade group’s vice president for state affairs and grass-roots advocacy.

Despite record revenue last year, major food-delivery companies didn’t report annual profits. DoorDash posted a profit in the second quarter of last year before slipping back into a loss. Uber trimmed losses for its Eats division last year, but the unit hasn’t posted a profitable quarter. Meanwhile, Grubhub reported a wider loss last year, attributing it to spending during the pandemic and the commission caps, in part.

Sam Toia, president of the Illinois Restaurant Association, said DoorDash’s commission move is a step in the right direction for restaurants still trying to manage with occupancy restrictions and growing costs. Mr. Toia said he is concerned that local restaurants will have less prominence on the service’s app if they choose the lower-cost option, though.

“I worry about independent restaurants,” Mr. Toia said.

Updated: 8-7-2021

Amid The Labor Shortage, Robots Step In To Make The French Fries

Fast-food chains are working with a host of startups to bring automation to their kitchens.

In a White Castle just southeast of Chicago, the 100-year-old purveyor of fast food has played host for the past year to an unusual, and unusually hardworking, employee: a robotic fry cook.

Flippy, as the robot is known, is no gimmick, says Jamie Richardson, a White Castle vice president. It works 23 hours a day (one hour is reserved for cleaning) and has operated almost continuously for the past year, manning—or robot-ing—the fry station at White Castle No. 42 in Merrillville, Ind.

An industrial robot arm sheathed in a grease-proof, white fabric sleeve, it slides along a rail attached to the ceiling, lifting and lowering each basket when ready, immune to spatters and spills. White Castle is so pleased with Flippy’s performance that, in partnership with its maker, Miso Robotics, the chain plans to roll out an improved version, Flippy 2.0, to 10 more of its restaurants across the country.

There were more than 1.3 million unfilled job openings at restaurants and hotels as of the end of May, double the number a year earlier, according to the Labor Department. For many restaurants, surviving the current labor crunch and resulting wage inflation means using self-service ordering kiosks and other tech tools to automate away some customer-facing jobs and streamline things like online ordering. But entrepreneurs and industry executives also are trying to tackle a bigger, knottier problem: automating the production of food itself.

Commercial kitchens, especially those in fast food restaurants, have long used automation of one form or another, both on-site and in the preparation of food before it even arrives at a restaurant. The industry has benefited over the decades from innovations ranging from microwave ovens to the drive-through.

But what’s happening now is different, says Michael Schaefer, lead analyst of food and beverage developments at Euromonitor, a consumer-trends analysis firm. In the pandemic era, the combination of scarce labor, an unprecedented increase in demand for takeout and delivery, and the minimal margins that delivery allows are compelling restaurateurs to look at technology they might have shied away from before, he says.

At the same time, automation and robotics in general are having a moment. The falling cost of sensors and actuators, plus the growing power and accessibility of the software to drive them, is being combined with systems for automated handling of food that have been used for years in factories that mass-produce things like frozen meals and ready-to-eat snacks, says Doug Foreman, an entrepreneur who created and sold the Guiltless Gourmet and Beanitos brands. His current project, Tacomation, which is still just a prototype, is an effort to replace the humans who work behind the counter at restaurants like Chipotle.

It’s not at all clear how many of the attempts to automate food production in restaurants, commercial “ghost kitchens,” corporate cafeterias and the like will yield workable solutions.

Food automation is littered with the carcasses of ambitious and well-capitalized startups, from Softbank-funded Zume Pizza’sJanuary 2020 flameout to Silicon Valley darling Melt’s mid-2010s implosion despite its claims to have developed automated, software-driven smart grills and ovens.

One of the biggest challenges engineers face in automating food preparation is that food isn’t like boxes in an automated warehouse or metal panels to be welded together by robots in an automobile factory.

“The real challenge is, how do you make machines that can manipulate this peculiar, non-conformative, multi-dimensionally deformative substance,” says Barney Wragg, chief executive of London-based Karakuri robotics, which is in the midst of installing the first of its “robotic canteens” in a corporate cafeteria.

That’s engineer-speak for the way that food is tricky to handle, and its characteristics change as you prepare it. Think of how different dry rice is from a mass of its cooked equivalent, adds Mr. Wragg, who at one point in our conversation referred to stew as “a viscous liquid with entrained solids in it.”

The complexity of cooking is multiplied by the challenges of safe food handling and varied temperatures. Surveying the technology of nearly a dozen startups, it’s clear that the main solution to the problem of food’s complexity is either tackling just a part of the food-preparation process, as with the Flippy robot fry cook, or tackling just one relatively simple type of meal.

Karakuri’s robot can create nearly any meal you like, from a yogurt parfait to a green salad, as long as it’s in some kind of bowl. It resembles a small grain silo with a robot arm at its center, able to raise and lower itself as it moves bowls among cubbies where food is poured, plopped or squirted out like chocolate in the Willy Wonka factory.

Tel Aviv-based Kitchen Robotics’ Beastro cooking robot operates on this same everything-should-be-a-bowl principle, even though its design looks radically different.

Beastro fills bowls with ingredients from extruders, then moves them to a line of cooking stations, which spin and heat food like little cement mixers.

Kitchen Robotics is focused on making sure its robot chef can operate more cheaply, on an hourly basis, than the cost of the humans it replaces, says company co-founder Ofer Zinger. Beastro can be leased for $7,500 a month, maintenance included, and is intended to replace two to three people in the back of a small, delivery-only ghost kitchen, he says.

Pizza is another relatively simple food amenable to automated production, hence the rollout of 38 (and counting) PizzaForno vending machines across North America, says Les Tomlin, co-founder of the company behind the machines.

The company partially bakes its crusts, flash freezes them, then has humans top them at regional kitchens, before they’re delivered to the refrigerated innards of its 80-square-foot machines. When someone orders a pizza from the device’s attached touch screen, the machine bakes it in three minutes.

Doordash’s February acquisition of Chowbotics, the company that makes a salad-making robot, and which has partnered with Kellogg’s to offer college campuses a cereal-dispensing machine, points to a future in which more of our meals might be made inside what are essentially souped-up vending machines.

Sitting inside existing restaurants or ghost kitchens, their contents delivered to us through apps, consumers might be none the wiser that their meal was prepared by a robot, says Mr. Schaefer of Euromonitor.

Del Taco, a chain of about 600 Mexican fast-food restaurants, is partnering with Miso Robotics to be a sort of living laboratory for a forthcoming drink-filling machine. The goal is shaving seconds off the time required to fulfill every order, says Kevin Pope, Del Taco’s vice president of operations innovation.

Eventually, he adds, the moment a customer makes an order—on a phone, at a kiosk, in a drive through or at the counter—a system will automatically queue up her drink selection for the machine, which takes a cup, fills it with ice, pours the appropriate liquid, snaps on a lid and delivers the finished beverage at the end of a conveyor belt. The humans it works alongside have only to grab it, instead of standing at a soda machine making the drink themselves.

For many of the restaurateurs and executives examining the costs and benefits of bringing more robots into their kitchens, the potential benefits are consistency and reliability as much as savings.

“The 17-year-old fry cook isn’t expensive labor, but the 17-year-old becomes expensive labor if he or she doesn’t show up for work,” says Ruth Cowan, a historian who has researched kitchen automation. The desire to replace unreliable humans with more-reliable machines has been a primary driver of the adoption of automation for more than 100 years, she adds.

That pressure is only intensifying as more and more people question whether they want to work in food service—with its shifting schedules, relatively low wages and physically and mentally demanding workload.

At the White Castle in Indiana, Flippy handles not just fries but most of the restaurant’s side items, including cheese sticks and onion rings. That means the humans who work alongside it have more time to interact with customers, says Mr. Richardson. “If you know you’ve got the fryer covered, it frees you up to have the right person taking orders in the dining room, or the drive-through,” he adds.

Automation has always promised more efficiency, says Dr. Cowan, but in her research she has found that, just as often as it decreases the labor required, it also raises the bar for the quality and variety of goods consumers expect.

Today, in other words, kitchen automation is being viewed as a way for restaurants, ghost kitchens and delivery giants to save time and money. In the future, however, it might be just another way to compete for the attention of the ever-fickle consumer—leaving the amount of human labor required more or less the same.

“In 1921, we had four menu items—hamburgers, Coca-Cola, coffee and apple pie, but as time goes on, people want more variety,” says Mr. Richardson of White Castle. The kitchen of the future, he adds, is one more way to provide it.

Updated: 9-2-2021

How Short-Staffed Restaurants Can Keep Customers Happy

Faced with changing Covid mandates and labor shortages, many restaurants are struggling to keep returning customers satisfied. One key: Be honest.

It’s no secret that the service industry has taken a hit from the pandemic, with restaurants in particular bearing the brunt of Covid-related shutdowns. After a short-lived return to normalcy this summer, restaurants once again are navigating a moving target of mandates as new Covid variants emerge. They also are struggling with labor shortages at a time when many people are eager to dine out after not being able to for more than a year.

With socially distanced table configurations, limited capacities and QR-code menus, how can restaurants keep their customers satisfied and stay afloat?

Here Are Some Ideas:

Manage Expectations: Many people are looking for a reprieve from the pandemic when they dine out, a way to time-travel back to a simpler time. Unfortunately, that isn’t the experience they are going to get right now. To reduce disappointment, restaurants need to manage expectations from the moment customers make their reservations until they leave the restaurant.

Whether it’s a strict reservation policy, masking rules or an increase in prices, customers need to know what the new normal looks like. Restaurants should clearly communicate any changes in service or dining-room rules on the restaurant’s website or on the landing page of a third-party reservation system.

In addition, the restaurants need to have clear signage about Covid-related rules and social-distancing restrictions, as well as time limits on table service. And they should present all that information in a way that makes clear the changes are designed to keep people safe.

Educate Staff: The restaurant’s staff needs to reinforce and expand on those initial instructions as they guide customers through their visit. Information should be presented in a way that feels organic to the dining experience, and not an additional restriction.

For example, if a restaurant decides to forgo serving food in courses to reduce dining times, servers can tell customers that to have the best experience, they recommend letting dishes come out when they are ready. Guests will be more amenable to new rules if they don’t seem arbitrary.

Gauge How Much To Reveal: Running a restaurant is a delicate and complicated choreography—unseen by guests, who aren’t supposed to see the inevitable, proverbial fires in the kitchen. However, when a customer enters a seemingly empty dining room and is still asked to wait a half-hour for a table, there is a disconnect.

The staff understands that this is because there is only one server on the floor, the kitchen is doing double duty with dine-in and takeout orders, and that spacing tables will ensure everyone is able to do their job.

If customers knew all this, would it make them more understanding? Maybe, depending on how upscale the restaurant is, who its customers are and the experience it seeks to provide. Each restaurant has to decide how much to reveal without risking losing the “magic” that keeps customers coming.

Decrease Capacity And Increase Prices: It can be tempting for restaurants to try to recoup early pandemic-related losses by moving full steam ahead. But if a restaurant is short-staffed, maxing out the dining room every night will just leave employees unable to handle the volume and guests dissatisfied.

It also may be a good time for restaurants to start thinking about what they need to do to find and keep good employees. Perhaps it’s time for them to re-evaluate their compensation structure and accommodate by increasing prices. A pay increase across the board could result in better, happier talent, and satisfied guests who are willing to pay for a good dining experience.

Updated: 10-1-2021

Insurers Increase Investments In Drones, Robots

Farmers Insurance this year plans to deploy a four-legged robot to inspect properties.

Insurance companies are increasing their investment in robotic systems aimed at helping claims adjusters evaluate storm-damaged properties with greater safety and less cost.

Travelers Cos., United Services Automobile Association and Farmers Insurance Group were among the major property and casualty companies to deploy aerial drones this summer to inspect property damage in the wake of Hurricane Ida.

And Farmers said last month that it would bring inspections back to ground level with plans to deploy a robotic dog to properties damaged by hurricanes, earthquakes and other catastrophic events.

International Data Corp. expects the insurance industry to spend about $602 million world-wide on robotics systems, including drones, in 2021, with spending growing to $1.7 billion in 2025.

“All these technologies are about augmenting the capacities of the so-called knowledge workers,” said Patrick Van Brussel, research director at the technology research company.

Drones and robots make insurance more effective, more efficient and safer, he said. Drones, for example, can quickly inspect a damaged roof and transmit images back to a claims system without sending an adjuster into a building that might be compromised.

Insurers will continue to embrace drones, robots and other technologies as companies find new uses for them, Mr. Van Brussel said.

Travelers, which has a fleet of more than 700 drones, last month deployed some 200 to inspect customers’ properties in the wake of Hurricane Ida, which made landfall in Louisiana and then traveled north through the U.S. The company said it plans to increase the use of drones for claims inspection.

“Drone use helps improve the safety for our field claim professionals and our field risk control professionals,” said Jim Wucherpfennig, vice president of property claim at Travelers. “The technology allows us to write damage estimates more quickly for our customers, pay them more quickly, so that they can begin the repairs to their property and get back on their feet.”

Farmers said drones also helped it assess the damage done to customers’ homes hit by Hurricane Ida.

“We’ve learned in the 100 years that we’ve been in business that investing in technologies that help make the claims handling process faster and more efficient leads to higher customer satisfaction,” said Samantha Santiago, head of claims strategy and automation at Farmers.

The company’s latest investment is Spot, a 70-pound, four-legged robot from Boston Dynamics Inc. that can be used to access unoccupied, structurally compromised houses and buildings to assess damage. Farmers will be the first insurance carrier to deploy the mobile robot.

“Spot gives us the ability on the ground to see what’s ahead of us. Things that may be difficult for an adjuster to see,” said Ms. Santiago.

The Farmers robot is equipped with a pan-tilt-zoom camera that will allow for 360-degree image capture and a thermal camera that will detect hot spots. Images captured by the robot will be transmitted to Farmers’ claims systems, where human adjusters and image-analysis systems will help determine the extent of the property damage.

Spot is expected to be deployed later this year.

A Farmers adjuster will be deployed along with Spot and will direct the robot’s movement.

While robots are taking on more jobs traditionally done by people, neither technology analysts nor insurance experts see robots replacing adjusters anytime soon.

The future of work involves people and robots working side-by-side, often creating a division of labor that lets robots do things that are repetitive, dangerous, or require analytics and humans using judgment, creativity, and people skills, said J.P. Gownder, a vice president and principal analyst at advisory firm Forrester Research Inc.

He also noted that today’s insurance robots and drones are almost entirely operated by humans.