Who’s Watching Who? gSpy vs. iSpy

Randi Zuckerberg, sister of Mark, thinks she’s got problems? Who’s Watching Who? gSpy vs. iSpy

Well, over a few hours around town that day I counted 57 cameras–at traffic lights, various stores and the bank–and my phone told me I switched between eight different cellphone towers. We are all being watched, whether we like it or not.

So who’s winning? It is a battle between you and the government–like Mad Magazine’s Spy vs. Spy comic, but it’s gSpy vs. iSpy.

Related:

Citizen Surveillance Is Playing A Major Role In Criminal Investigations

Ultimate Resource On “Havana Syndrome” Including New Cases of The Mysterious Illness

Harvard Chemical Biology Department Chair Accused Of Selling Covid19 To Wuhan University

Pentagon Sees Giant Cargo Cranes As Possible Chinese Spying Tools

US. Can Learn From China’s Spot-The-Spy Program

Apple, Google Forced To Give Governments User “Push Notifications” Data

America’s Spies Are Losing Their Edge

Vast Troves of Classified Info Undermine National Security, Spy Chief Says

Pentagon Being Investigated For One Of The Most Dangerous Intelligence Breaches In Decades

Ex-CIA Engineer Goes On Trial For Massive Leak

Ex-Intelligence Analyst Charged With Leaking Classified Information

CFPB (Idiots) Says Staffer Sent 250,000 Consumers’ Data To Personal Account

There are thousands of toll booths at bridges and turnpikes across America recording your license plate. There are 4,214 red-light cameras and 761 speed-trap cameras around the country. Add 494,151 cell towers and 400,000 ATMs that record video of your transactions.

New York City alone has 2,400 official surveillance cameras and recently hired Microsoft to monitor real-time feeds as part of the Orwellian-named Domain Awareness System.

And that is nothing compared with England, where over four million surveillance cameras record the average Londoner 300 times a day.

Popular Mechanics magazine estimates that there are some 30 million commercial surveillance cameras in the U.S. logging billions of hours of video a week. I guarantee that you’re in hundreds if not thousands of these.

In the year 1984, we only had lame amber-screened PCs running Lotus 123. Now, 64 years after George Orwell sent “1984” to his publisher, we have cheap video cams and wireless links and terabyte drives and Big Brother is finally watching.

So gSpy Is Winning, Right?

Not so fast. We are watching back. I know the precise number of red-light cameras because a website (poi-factory.com) crowdsources their locations and updates them daily for download to GPS devices. And 30 million surveillance cameras are a pittance compared with the 327 million cellphones in use across America, almost all of them with video cameras built in.

How do you think the “Don’t tase me, bro” guy protesting a 2007 speech by John Kerry ever got famous? Last year, when cops at the University of California at Davis were caught on video pepper-spraying protesters, they had to pay $30,000 each to 21 students to settle. A man arrested for blocking traffic at an Occupy Wall Street protest (who was there to defend police tactics, oddly) was acquitted when smartphone photos and video showed protesters on the sidewalk, not the street. Six members of the 2004 St. John’s basketball team had rape charges against them dropped when a video of the accuser’s extortion demands was recorded on a player’s cellphone.

Zapruder, Rodney King, the young Iranian Neda Agha-Soltan’s death by gunshot after her country’s rigged 2009 election. In America and increasingly across the world, iSpies are watching, too.

Both sides are getting more sophisticated. Snowboarders mount GoPro Hero cameras to their helmets to record up to eight hours of their exploits. So-called lifeloggers pin small, $199 “Memoto” cameras to their shirts and snap a photo every 30 seconds. With cheaper data storage, it is easy to envision iSpies logging audio, GPS and eventually video of our lives.

But gSpy is going further. Already a third of large U.S. police forces equip patrol cars with automatic license plate-readers that can check 1,000 plates per hour looking for scofflaws. Better pay those parking tickets because this system sure beats a broken tail light as an excuse to pull you over. U.S. Border Patrol already uses iris-recognition technology, with facial-recognition in the works, if not already deployed. How long until police identify 1,000 faces per hour walking around the streets of New York?

In September, Facebook turned off its facial-recognition technology world-wide after complaints from Ireland’s Data Protection Commission. I hope they turn it back on, as it is one of the few iSpy tools ahead of gSpy deployment.

The government has easy access to our tax information, stock trades, phone bills, medical records and credit-card spending, and it is just getting started. In Bluffdale, Utah, according to Wired magazine, the National Security Agency is building a $2 billion, one-million-square-foot facility with the capacity to consume $40 million of electricity a year, rivaling Google ‘s biggest data centers.

Some estimate the facility will be capable of storing five zettabytes of data. It goes tera, peta, exa, then zetta–so that’s like five billion terabyte drives, or more than enough to store every email, cellphone call, Google search and surveillance-camera video for a long time to come. Companies like Palantir Technologies (co-founded by early Facebook investor Peter Thiel) exist to help the government find terrorists and Wall Street firms find financial fraud.

As with all technology, these tools will eventually be available to the public. Internet users created and stored 2.8 zettabytes in 2012. Facebook has a billion users. There are over 425 million Gmail accounts, which for most of us are personal records databases. But they’re vulnerable. We know from the takedown of former Gen. David Petraeus

that some smart legwork by the FBI (in this case matching hotel Wi-Fi tags and the travel schedule of biographer Paula Broadwell can open up that database to prying eyes. Google has accused China of cracking into Gmail accounts.

Google gets over 15,000 criminal investigation requests from the U.S. government each year, and the company says it complies 90% of the time. The Senate last week had a chance to block the feds from being able to read any domestic emails without a warrant–which would put some restraint on gSpy–but lawmakers passed it up. Google’s Eric Schmidt said in 2009, “If you have something that you don’t want anyone to know, maybe you shouldn’t be doing it in the first place.” Thanks, Eric.

From governments to individuals, the amount of information captured and stored is growing exponentially. Like it or not, a truism of digital technology is that if information is stored, it will get out. Mr. Schmidt is right. It doesn’t matter whether an iSpy friend of Randi Zuckerberg tweets it or a future WikiLeaks pulls it out of the data center at Bluffdale and posts it for all to view.

Gen. Petraeus knows it. Politicians yapping about “clinging to guns” or “the 47%” know it. Information wants to be free and will be. Plan for it. I’m paying my parking tickets this week.

Updated: 6-29-2023

Police Are Requesting Self-Driving Car Footage For Video Evidence

San Francisco police request driverless car footage from Waymo and Cruise to solve crimes from robberies to murders.

In December 2021, San Francisco police were working to solve the murder of an Uber driver. As detectives reviewed local surveillance footage, they zeroed in on a gray Dodge Charger they believed the shooter was driving. They also noticed a fleet of Waymo’s self-driving cars, covered with cameras and sensors, happen to drive by around the same time.

Recognizing the convenient trove of potential evidence, Sergeant Phillip Gordon drafted a search warrant to Alphabet Inc.’s Waymo, demanding hours of footage that the SUVs had captured the morning the shooting took place.

“I believe that there is probable cause that the Waymo vehicles driving around the area have video surveillance of the suspect vehicle, suspects, crime scene, and possibly the victims in this case,” Gordon wrote in the application for the warrant to Google’s sister company. A judge quickly authorized it, and Waymo provided footage.

As self-driving cars become a fixture in major American cities like San Francisco, Phoenix and Los Angeles, police are increasingly relying on their camera recordings to try to solve cases.

In Waymo’s main markets, San Francisco and Arizona’s Maricopa County, Bloomberg found nine search warrants that had been issued for the company’s footage, plus another that had been sent to rival autonomous driving firm Cruise. More warrants may have been issued under seal.

The footage presents new avenues for police to investigate serious crimes, as they did in the murder of the Uber driver, Ahmed Yusufi, who was killed between shifts.

Yet privacy advocates say it is crucial to consider the implications of handing police another tool for surveillance, especially as Waymo and Cruise accelerate expansion to more cities.

In the Phoenix area, Waymo has a partnership with Uber for people to eventually request driverless rides through that familiar app; it has also announced plans to test its service in Austin, where Cruise already operates.

While security cameras are commonplace in American cities, self-driving cars represent a new level of access for law enforcement — and a new method for encroachment on privacy, advocates say.

Crisscrossing the city on their routes, self-driving cars capture a wider swath of footage. And it’s easier for law enforcement to turn to one company with a large repository of videos and a dedicated response team than to reach out to all the businesses in a neighborhood with security systems.

“We’ve known for a long time that they are essentially surveillance cameras on wheels,” said Chris Gilliard, a fellow at the Social Science Research Council.

“We’re supposed to be able to go about our business in our day-to-day lives without being surveilled unless we are suspected of a crime, and each little bit of this technology strips away that ability.”

Waymo said it occasionally receives requests from local police in markets where it operates and generally requires law enforcement to provide a warrant or court order.

“We carefully review each request to make sure it satisfies applicable laws and has a valid legal process,” Waymo said. “If a request is overbroad (asks for too much information), we try to narrow it, and in some cases we object to producing any information at all.”

Cruise said it also strives to provide the minimum amount of data necessary to satisfy requests from law enforcement.

“Privacy is extremely important to us, which is why we disclose relevant data only in response to legal processes or exigent circumstances, where we can help a person who is in imminent danger,” Cruise said in a statement.

Waymo emerged from the labs of Google, whose rich user data creates opportunities for law enforcement at every turn. In one hit-and-run case in San Francisco, police learned Waymo had passed by the crime scene while reviewing footage from a Nest home surveillance camera, presenting yet another connection with Google, which bought the smart-home hardware maker in 2014.

Privacy advocates are particularly concerned about the evidence that police can glean from the so-called internet of things, the growing landscape of connected devices such as doorbells and home security cameras that collect vast amounts of data.

Amazon’s Ring doorbells have found a following with both consumers and law enforcement; thousands of agencies subscribe to its Neighbors app, where camera owners voluntarily upload footage.

Last year, Amazon revealed that it had shared footage in emergencies without owners’ permission, sparking criticism from lawmakers. Amid the controversy over Ring’s data collection, Amazon has begun offering end-to-end encryption of the videos and has asked cops to request footage publicly in the Neighbors app.

While self-driving services like Waymo and Cruise have yet to achieve the same level of market penetration as Ring, the wide range of video they capture while completing their routes presents other opportunities.

In addition to the San Francisco homicide, Bloomberg’s review of court documents shows police have sought footage from Waymo and Cruise to help solve hit-and-runs, burglaries, aggravated assaults, a fatal collision and an attempted kidnapping.

In all cases reviewed by Bloomberg, court records show that police collected footage from Cruise and Waymo shortly after obtaining a warrant.

In several cases, Bloomberg could not determine whether the recordings had been used in the resulting prosecutions; in a few of the cases, law enforcement and attorneys said the footage had not played a part, or was only a formality.

However, video evidence has become a lynchpin of criminal cases, meaning it’s likely only a matter of time.

In markets where Waymo and Cruise operate, police departments have alerted their detectives to the investigative opportunities that the vehicles present. A San Francisco Police Department training document obtained by Vice instructed detectives of the vehicles’ “potential to help with investigative leads.”

Waymo said it responds to law enforcement requests with footage that blurs license plates and faces “in order to protect the privacy of bystanders who may appear in the imagery that’s requested by the warrant.” But San Francisco police seem to be trying to find a way around that.

Two of the warrants reviewed by Bloomberg, which were obtained in burglary cases, noted Waymo’s practice of “fogging” footage and requested “a true and accurate depiction of the vehicle’s recordings.”

Comprehensive privacy legislation, which has languished for years in the US, is ultimately the only thing that can thwart overly broad requests from police, experts say.

“With the lack of consumer privacy protections that we have in the US right now, companies are able to collect as much information as humanly possible,” said Matthew Guariglia, a policy analyst at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, adding that police are then able to capitalize on the trove of data.

Police who have obtained footage from self-driving cars say they view it as a tool to be used judiciously — and that the evidence can be used not just to build cases, but to exonerate suspects.

Last year, a teen in Mesa, Arizona, said she was trying to hop into a Waymo she had hailed when her cell phone, which riders use to enter the vehicle, ran out of battery.

She claimed a man offered to help her charge her phone and then attempted to force her into his vehicle. Bystanders intervened. All the while, Waymo was recording.

When Mesa Detective Trisha Jackson received the report, she recalled a flyer she had received from her department when self-driving cars became more prevalent in the area about the opportunities that footage from the vehicles could create for cops.

She reached out to the company, which she said offered guidance on the warrant process. But when Waymo ultimately produced the footage, it contradicted the teen’s account. Jackson saw no evidence of a crime.

Jackson said reviewing the Waymo footage enabled her to close the case more quickly, saving police resources.

“We were able to contact the company and get the search warrant done, and they were able to give us exactly what we had asked for in a timely manner,” she said.

Last year, San Francisco police obtained a search warrant for Waymo footage to try to solve a spate of residential burglaries. John McCammon, whose apartment was among those burglarized, says he has mixed feelings about police seeking such evidence.

He’s wary of handing police a new tool, especially in San Francisco, where the police department has made headlines for its proposal to use robots and other high-tech investigative techniques.

When a Bloomberg reporter informed McCammon that Waymo had witnessed the crime, he wasn’t surprised. The vehicles are such a regular presence on his street that he has considered writing to the local government to complain.

He said Waymo’s assistance in his case was unlikely to change his opinion of the self-driving service, which he has already written off as a “constant irritant.” Local officials are often responding to complaints about Waymo and Cruise vehicles blocking roads when their software is confused by construction, parades and crime scene barricades.

And the footage isn’t always helpful. In the case of the Uber driver who was shot, San Francisco police arrested Clifford Stokes, who was convicted of murdering Yusufi earlier this year.

Yusufi had worked as an interpreter for the American military during the war in Afghanistan, and after settling in California, he supported himself by working as an Uber driver, according to local media reports. He was killed in a botched armed robbery in between shifts.

A lawyer involved in the case said though police did obtain the Waymo video, it was not ultimately used in the prosecution of Stokes, as Waymo had not actually filmed the Dodge Charger. Still, such cases are a reminder of the new frontier that self-driving cars open up for law enforcement, privacy advocates say.

Police tapped Waymo for the footage in that murder case just a few months after the company began testing its self-driving service with members of the public in San Francisco.

“Whenever you have a company that collects a large amount of data on individuals, the police are eventually going to come knocking on their door hoping to make that data their evidence,” Guariglia said.

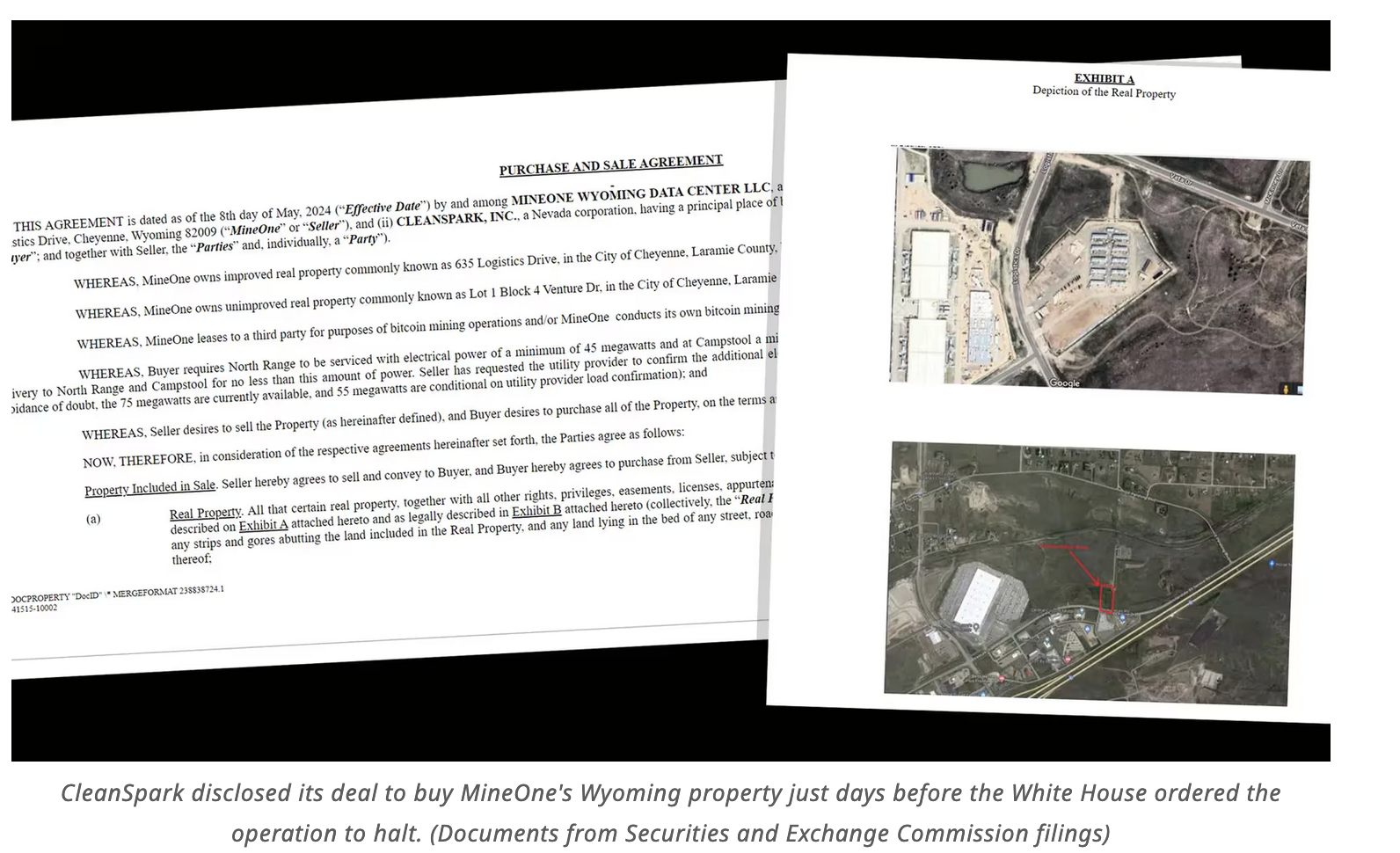

Spy Fears Over A Chinese Corn Mill Led Biden To Tighten US Investment Curbs

Rising US hostility toward China surfaces in Middle America.

Presidents Joe Biden and Xi Jinping are trying to ease tensions and calm trade fights between the world’s top economies. The collapse of a project in the American heartland shows just how deep a chill has set in.

Biden dispatched Secretary of State Antony Blinken for a visit to Beijing and a meeting with Xi last week, and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen is planning her own visit in July, according to people familiar with the matter.

But Biden’s gestures are accompanied by a souring national mood on China. Underneath the pomp of top-tier visits by US officials, there is growing resentment among ordinary Americans and state and local politicians toward Chinese attempts at US investment.

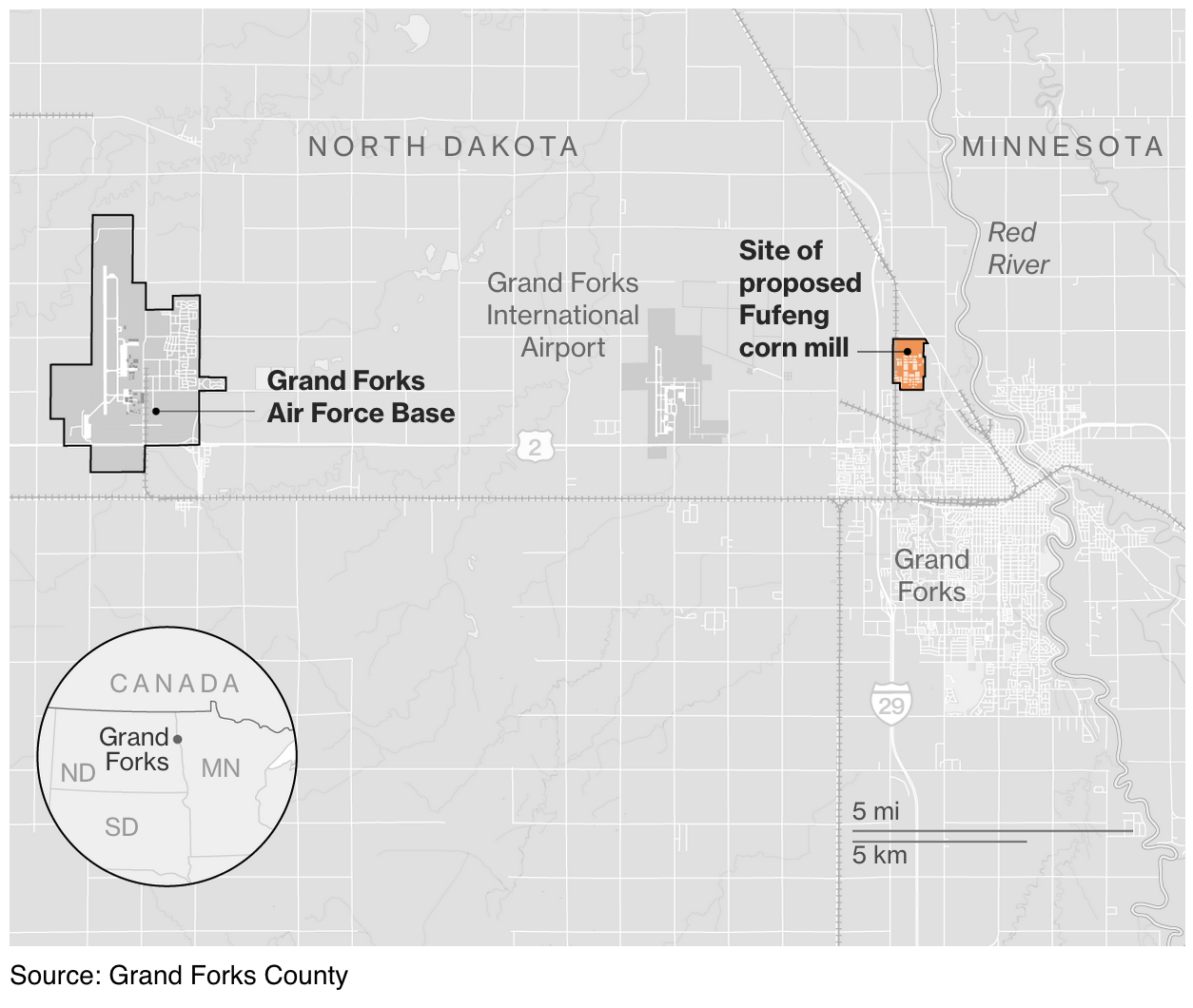

There’s no clearer example of the grassroots shift in sentiment than in Grand Forks, North Dakota, where a failed agricultural complex led to new proposals at both the federal and state level to restrict China-linked development.

The city this year abandoned a project that, just two years earlier, it had aggressively sought as an economic bonanza: a $700 million corn mill that would have risen from rich farmland on the outskirts of the community.

The mill faced a groundswell of opposition, especially regarding its owner: a Chinese company, Fufeng Group.

The saga touched off a battle emblematic of growing US angst about Chinese investment. It combined swirling local concerns, opaque federal rules, saber-rattling politicians and potential loopholes in security laws, ultimately concluding with an unusual public warning from the Air Force that the corn mill posed a national security threat.

The ripples reached beyond Grand Forks, as Biden’s administration in May quietly moved to tighten scrutiny of foreign property purchases near the city’s Air Force base and other military facilities.

The abandoned corn mill also illustrates a political shift. Politicians who once backed the project— including North Dakota’s governor, Doug Burgum, a Republican running for president — now oppose it.

Some Republican-led states, including Burgum’s, seek to restrict or outright ban Chinese property purchases. The mayor of Grand Forks, Brandon Bochenski, says cities like his shouldn’t be left to determine foreign investment policy.

“Until there is an actual strategy, I don’t see how you can have really any investment from China — whether it’s ag, or tech, or anything,” Bochenski said in an interview in a city building that once housed the local newspaper.

“Right now, I think that’s the problem,” he said. “There’s no clear direction from the federal government.”

`Great Day for Grand Forks’

Fufeng Group’s corn mill once looked like an economic prize. It promised hundreds of jobs and enough corn products to fill 180 train cars a week. Grand Forks won the project over about two dozen other Midwest locations.

A $700 Million Corn Mill That Raised US Suspicions

Beijing-based Fufeng Group sought to build a wet corn mill 12 miles from a US air base.

Fufeng Group, founded in 1999 and listed on the Hong Kong stock exchange, is the world’s largest manufacturer of the common food additives monosodium glutamate and xanthan gum, according to its website. Its investors include Treetop Asset Management, Blackrock Inc. and the Vanguard Group.

The company’s US representatives declined interview requests but said in written responses to questions that it “does not pose a national security threat.”

“Our plant is designed to mill corn and make livestock feed ingredients,” the company’s spokespeople said. “Neither the US company nor the Fufeng Group have any ties to any government, political party, or official.”

Fufeng’s US subsidiary sought in the spring of 2020 to build its first US wet corn mill. The endeavor was dubbed “Project Peony,” after a flower popular in both China and the US. Grand Forks officials were jubilant when the company notified them they’d won.

“Great Day for Grand Forks, Great Day for North Dakota!” Keith Lund, who leads the city’s economic development agency, wrote in an email.

Local opposition focused at first on concerns such as pollution, subsidies and land use, but soon shifted to the mill’s ownership.

“Larger and louder than all of the other concerns was a fear of Communist China,” said Katie Dachtler, the only member of the city council to initially vote against the project, who has since left office. “And we can’t talk about the Chinese without them being ‘communists.'”

People in Grand Forks who opposed the project from the start say their political leaders should have seen the trouble coming.

“You come here because you can get away with stuff,” said Frank Matejcek, a farmer who lives just outside the city.

“Everyone kept saying they would do due diligence, and look into this, and the company had been vetted and all this stuff, when actually none of this was happening,’’ he said.

Fufeng Fighters

The city and Fufeng signed a deal in May 2022. But as complaints mounted, city leaders grappled for a clear answer about whether the mill could be a front for Chinese spies.

City and state officials, including its two senators and the governor, requested a review by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US, or CFIUS, a secretive panel led by Yellen.

It would not have been Grand Forks’s first experience doing business with China. Cirrus Aircraft Corp., which operates a factory in the city, is owned by a Chinese government-controlled firm, China Aviation Industry General Aircraft. Cirrus’s purchase by CAIGA in 2011 was subject to a CFIUS review, which yielded an agreement allowing the government to closely monitor the business’s operations.

But CFIUS told state and local officials it didn’t have jurisdiction over the mill. Building the project on land Fufeng had already bought — for $26,000 an acre, according to its opponents, a price they regarded as suspiciously inflated — wasn’t considered an acquisition, and the property wasn’t close enough to the base to trigger a probe, under rules in effect at the time.

“If a wet corn-milling plant run by Fufeng isn’t under CFIUS jurisdiction, then CFIUS has a problem,” said Kelly Armstrong, the state’s lone House member.

The Air Force would have its own say. In January, the service’s assistant secretary, Andrew Hunter, wrote to the state’s two senators, Kevin Cramer and John Hoeven.

The Air Force’s “unambiguous” view, Hunter wrote, was that the mill posed “a significant threat to national security, with both near- and long-term risks.”

The one-page letter didn’t elaborate. But political support evaporated, and the city council voted Feb. 6 to end the project — two days after President Joe Biden ordered an alleged Chinese surveillance balloon shot down after it floated across the country.

Spokespeople for the Air Force and the Grand Forks base declined further comment.

Cramer, who received a classified briefing on the project in December, said he has little doubt about Fufeng’s motive.

“It was highly likely that the investment was made to take advantage of its proximity of the Air Force base,” the senator said in an interview.

Local opponents — who call themselves the Fufeng Fighters, a play on the name of the rock band Foo Fighters — say the federal government should have been more involved from the start.

“It’s easy to see how there needs to be more federal scrutiny,” said Ben Grzadzielewski, a contractor who organized a petition over a range of concerns, including the mill’s environmental impact and public subsidies. “Because at a local level, it’s pretty easy to convince them of how great things are, and get them to run with it.”

Burgum Reversal

Burgum, the governor who helped woo Fufeng to North Dakota, “initially expressed support for the value that a wet corn mill would add for the area’s corn growers and the economic benefits to the region,” his spokesman Mike Nowatzki said in a statement.

But he said the governor “urged an expedited review of the land purchase and shared our U.S. senators’ concerns about the project several months” before it was canceled.

The project’s demise has been felt far beyond Grand Forks.

The Treasury Department in May proposed adding the Grand Forks base and seven others to a list of military facilities around which foreign investment within 100 miles triggers a CFIUS review.

Sensitive Real Estate

The Biden administration added Grand Forks AFB and seven other installations to a list of bases where nearby foreign property purchases can trigger federal review.

The North Dakota saga ended hopes of reviving plans by Chinese state-owned food processor Cofco Corp. to purchase an interest in a Cargill Inc. and CHS Inc. shipping terminal, according to a person familiar with the proposed transaction.

North Dakota passed a law this year banning foreign purchases of agricultural land, except by Canadians. A similar bill in Texas passed the state’s Senate but died in the House. Florida’s government has been sued over a law it adopted earlier this year banning all property purchases by Chinese nationals.

Fufeng still owns its Grand Forks land but is seeking “alternative options.” The US political climate is working against it.

Bob Scott, the mayor of Sioux City, Iowa, another city Fufeng considered, said in an interview that there’s no longer any interest. “Following that, up in North Dakota, they’re going to have a very, very difficult time getting a community,” he said.

Updated: 6-30-2023

US Spies Issue Warnings Over Risks of Doing Business In China

US intelligence officials renewed warnings for American companies doing business in China, citing an update to a counterespionage law that’s due to take effect in the next day.

A bulletin issued by the National Counterintelligence and Security Center on Friday warns executives that an update to China’s counterespionage law, which comes into effect on July 1, has the “potential to create legal risks or uncertainty” for companies doing business in China.

It adds that the law broadens the scope of China’s espionage law and expands Beijing’s official definition of espionage. “Any documents, data, materials, or items” could be considered relevant to the law due to its “ambiguities,” the bulletin says.

The revisions to China’s counterespionage law have raised further concerns for US companies, which already find themselves in caught in the middle of an increasingly fraught US-China relationship.

The law is just one of a slew of measures taken by President Xi Jinping to strengthen state power and clamp down on foreign influence.

Earlier this year, authorities in China questioned staff at the China offices of US consultancy Bain & Company. Officials also raided

the Beijing office of New York-based due diligence firm Mintz Group and detained five of its Chinese employees. China’s foreign ministry put out a short statement saying Mintz was suspected of illegal business operations, while separately stating that it wasn’t aware of any raid at Bain’s Shanghai office.

The bulletin also draws attention to other pieces of Chinese legislation, including the 2021 Cyber Vulnerability Reporting Law, which it says could provide Beijing with the “opportunity to exploit system flaws before cyber vulnerabilities are publicly known.”

It also discusses the 2017 National Intelligence Law, which it says may force locally employed Chinese nationals working at US companies to assist in intelligence efforts for Beijing.

Updated: 7-17-2023

Inside Russia’s Spy Unit Targeting Americans

This transcript was prepared by a transcription service. This version may not be in its final form and may be updated.

Peter Zwack: My name is Peter Zwack, retired US Army Brigadier General. I was in Moscow serving as our senior U.S. Defense Attaché.

Kate Linebaugh: Peter served in Moscow from 2012 to 2014, and during that time he noticed some strange things, like the time he was driving and saw someone tailing his car from above.

Peter Zwack: We had a helicopter just there hovering for a while as we were driving along.

Kate Linebaugh: Sometimes his family would come home and just sense that something was off.

Peter Zwack: There would just be strange signs that somebody had been in your apartment. My son lost his watch or thought his watch would move, and then one day, a week or two later, the watch was sitting there on the floor, just odd, clothing moved. And it’s kind of a tap on the shoulder that we know you’re here.

Kate Linebaugh: A tap on the shoulder from Russia’s spy network.

Peter Zwack: You have to make the assumption when you’re in Moscow that you are under surveillance and you’re being followed one way or the other.

Kate Linebaugh: Peter is one of many Americans who said they’ve experienced unsettling things in Russia. Americans, including our colleague, Evan Gershkovich, who was followed by several Russian security officers. Earlier this year, Evan was arrested on espionage charges, charges that he and the Wall Street Journal vehemently deny. Now, after months of reporting, the Journal has uncovered that one secret unit in Russia’s powerful spy agency is behind it all. Welcome to the Journal, our show about money, business, and power. I’m Kate Linebaugh. It’s Monday, July 17th. Coming up on the show, the secretive Russian security force targeting Americans. On March 29th, Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich was on a reporting trip outside of Moscow when he was arrested. When they first heard the news, our colleagues, Joe Parkinson and Drew Hinshaw, had a lot of questions.

Drew Hinshaw: Almost immediately after, Joe and I started to think about, “Well, who took him?”

Joe Parkinson: And that’s a very simple question, but it led us on this very, very complicated transnational journey where the simple question actually revealed this much bigger truth about not just one of the most opaque corners of the Russian security services but also the power that this particular unit has inside Putin’s Russia today.

Kate Linebaugh: Joe and Drew’s reporting journey took them across Europe and the US. They interviewed dozens of senior diplomats and security officials, former Russian intelligence officers, Americans who’d previously been jailed in Russia and their families, as well as independent Russian Journalists and security analysts who fled the country. They also drew information from public court proceedings as well as reviewed leaked Russian intelligence memos.

Drew Hinshaw: And we spoke with former American officials and current American officials who had the unpleasant life of being based in Moscow or traveling to Moscow and being subject to spycraft and harassment.

Kate Linebaugh: They heard stories about intimidation tactics that at times sounded like juvenile pranks, like the kind Peter described.

Joe Parkinson: The bookcases have been moved around. People will come home; the car keys are missing, the jewelry is missing. Another thing they do is leave a calling card, which is a lit cigarette or a stubbed-out cigarette, on a toilet seat.

Kate Linebaugh: Other times, these calling cards were nasty.

Drew Hinshaw: An American official visiting Moscow came back to his hotel room and found someone had defecated in his suitcase.

Kate Linebaugh: Ew. Some were unsettling.

Joe Parkinson: They also liked to slash the tires of cars that are parked around the embassy or the residences of diplomats.

Drew Hinshaw: They’ve followed an ambassador’s young children to things like soccer practice and into a McDonald’s.

Kate Linebaugh: And sometimes the stories were downright scary.

Drew Hinshaw: Someone working in the Defense Attaché’s office came home and found his dog dead in what appeared to be a poisoning.

Kate Linebaugh: Joe and Drew suspected that behind many of these antics was Russia’s main security service, the FSB, which had replaced the old Soviet-era KGB. So they started to talk with their sources about what exactly was going on inside the agency.

Joe Parkinson: As we were plunging into this huge, opaque, deliberately secretive institution, which is the FSB, we tried, first of all, to map what the different directorates were because the FSB is very, very complicated, structured into these directorates, inside these directorates, all these smaller subdivisions.

Kate Linebaugh: And then they got a tip, a potential name for the unit.

Joe Parkinson: And one of the former US ambassadors that we spoke to said, “Well, the subdivision of the unit that’s responsible for following Americans has always been DKRO.”

Kate Linebaugh: DKRO, or the DKRO, for the Department for Counterintelligence Operations. Joe and Drew now had something to go on. The problem was they could scarcely find anything about it.

Drew Hinshaw: Well, I think at one point I Googled them, and there’s like 35 Google results, and most of them were just random. If you Google four random letters, some weird stuff comes up.

Joe Parkinson: Do you know that the Wikipedia page for DKRO was created after our story was written?

Kate Linebaugh: I did not know that. So what is DKRO?

Drew Hinshaw: DKRO is the counterintelligence arm of the FSB. They’re responsible for monitoring foreigners in Russia. So if you visit Russia, there’s a good chance they would be monitoring you. And its first section, DKRO-1, is the subdivision responsible for following Americans and Canadians.

Kate Linebaugh: Those slash tires, the dead dog, Peter’s car being trailed by a low-flying helicopter, US officials have chalked it up to DKRO, though it’s impossible to know whether DKRO is behind every such incident. The unit makes no public statements. And in the course of your reporting, you spoke with so many people; what did they tell you was the goal of all of this?

Drew Hinshaw: They said the goal is to stifle any American diplomats movements in Russia, to keep them inside the embassy walls, have them put their heads down, and do nothing during their two or three years they’re base there.

Joe Parkinson: Many people who worked in that embassy over the last 10 years did say that the Russians’ tactics were incredibly effective.

Kate Linebaugh: Neither the FSB nor the Kremlin responded to written questions. The State Department and the US Embassy in Moscow declined to comment, as did Evan’s lawyers in Russia. The modern-day FSB traces its roots to the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Drew Hinshaw: Every pillar of Soviet society collapsed. But there was one thing that survived, and that was the spy agencies.

Kate Linebaugh: Out of the ashes of the KGB came the FSB, and its expanding role in Russian life was helped by one person in particular, Vladimir Putin.

Joe Parkinson: This is a man who wanted to join the KGB since he was a teenager. He famously walked into the KGB office in St. Petersburg through the front door and asked if he could join, which is a very unusual way of being recruited. They told him to go off to university and study, and maybe then he could be hired.

Kate Linebaugh: The young Putin did return after graduating, and he had big ambitions. Around this time, Drew says a new Russia was emerging.

Drew Hinshaw: There’s this huge 1990s influx of American investors, reporters, visitors. There’s a McDonald’s in Moscow. Russia is now open.

Kate Linebaugh: In 1998, Putin became the head of the FSB, and then in 2000, he became President of Russia. Under his leadership, the security services role has expanded; some security analysts now call Russia a counterintelligence state, with the FSB controlling many aspects of Russian life. And one arm of the FSB that’s grown is DKRO.

Joe Parkinson: People that we spoke to said that DKRO’s operations essentially ebb and flow with the policy inside the Kremlin. However, as Russia and Putin’s Russia has become more and more insular in the last 20 years, as Putin himself has become more paranoid, DKRO has become an expression of that.

Kate Linebaugh: Isn’t this just what countries do, everybody’s spying on everybody?

Joe Parkinson: It’s definitely the case that intelligence services exist for a reason. Countries are spying on each other, enemies, friends, all of these institutions are trying to gather information, but there is something everyone who has served in Moscow says, and that is that it is qualitatively different. It is much, much more hostile.

Kate Linebaugh: And this more hostile posturing would have big consequences for foreign journalists, journalists like Evan Gershkovich. That’s next. Drew says Evan’s detention in March doesn’t seem to have been his first brush with DKRO agents.

Drew Hinshaw: Evan had had these bizarre experiences where, on one assignment, Evan was followed by several Russian security officers, at least one of whom had his camera out and was recording his movements.

Kate Linebaugh: After the invasion of Ukraine, Evan began investigating the expanding role the security services played in Russia. He and some colleagues reported that the FSB had mainly planned the invasion, not the military. But as the war dragged on and began to flounder, the FSB came under pressure from President Putin.

Drew Hinshaw: He publicly berated his spy agencies several times, saying that they needed to kick up their work. At one point, he says, quote, “You need to significantly improve your work.”

Vladimir Putin: (Russian)

Kate Linebaugh: Soon after, US officials noticed an uptick in aggressive actions toward the few Americans still in Russia.

Drew Hinshaw: And around that time, Evan, among many other reporters, started to notice that they were being followed by what we now understand to be DKRO.

Kate Linebaugh: While awaiting trial, Evan is being held in Russia’s Lefortovo prison, the same prison where former US Marine Paul Whelan was once held. Whelan is now serving a 16-year sentence on spying charges. The US State Department has deemed Whelan and Evan as wrongfully detained. Since Evan’s arrest, another American has been picked up by security services in Russia. Last month, a former US paratrooper and musician named Travis Michael Leek was detained on drug charges, which he denies. In recent years, Russia and the US have engaged in several prisoner swaps, including for Britney Griner, and last week President Biden said he is, quote, “serious about a prisoner exchange for Evan.”

Drew Hinshaw: So clearly, this continues. Evan is neither the first nor the last attempt by Russia to use human beings as bargaining chips in this conflict with America.

Kate Linebaugh: Joe and Drew say that their reporting showed Putin knew about the operation to arrest Evan.

Joe Parkinson: While we don’t know and we perhaps will never know whether Putin himself ordered Evan to be arrested, we do know a proposal for this operation reached his desk before March 29th, when Evan was taken. We do know from speaking to people who are familiar with the situation that, after the arrest, Putin was briefed by Vladislav Menshchikov, who is in charge of counterintelligence at the FSB. And we do know that he asked how the operation went. He wanted details on the operation.

Kate Linebaugh: What does this ramp up of surveillance of Westerners in Russia tell us about Putin?

Drew Hinshaw: The thing I was struck with is just how much Russia is a country run by the spy chief. Putin was the FSB director, and he runs the country exactly the way you would imagine an FSB director surrounded by paranoid former and current spies would.

Joe Parkinson: Yes, it’s a mentality that’s paranoid. Yes, it’s a mentality that is very, very suspicious of the West, but it also shows that he’s still very interested in operations that you would think someone like him perhaps wouldn’t have the time or the inclination to be following on a granular level. So it really is someone who’s still following the minutiae and someone who’s still running the entire country, not just as if he’s the president but as if he’s also head of the security services.

Kate Linebaugh: That’s all for today, Monday, July 17th. The Journal is a co-production of Gimlet and the Wall Street Journal. Also, if you haven’t listened to our recent series, With Great Power: The Rise of Superhero Cinema, go back and check it out. It’s in your feed. Thanks for listening. See you tomorrow.

Updated: 8-10-2023

To Battle New Threats, Spy Agencies To Share More Intelligence With Private Sector

Pandemics, cyberattacks and supply-chain disruptions are pushing government to work more with outside groups.

WASHINGTON—U.S. spy agencies will share more intelligence with U.S. companies, nongovernmental organizations and academia under a new strategy released this week that acknowledges concerns over new threats, such as another pandemic and increasing cyberattacks.

The National Intelligence Strategy, which sets broad goals for the sprawling U.S. intelligence community, says that spy agencies must reach beyond the traditional walls of secrecy and partner with outside groups to detect and deter supply-chain disruptions, infectious diseases and other growing transnational threats.

The intelligence community “must rethink its approach to exchanging information and insights,” the strategy says.

The U.S. government in recent years has begun sharing vast amounts of cyber-threat intelligence with U.S. companies, utilities and others who are often the main targets of foreign hackers, as well as information on foreign-influence operations with social-media companies.

The last National Intelligence Strategy was released in 2019 under the Trump administration, before the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

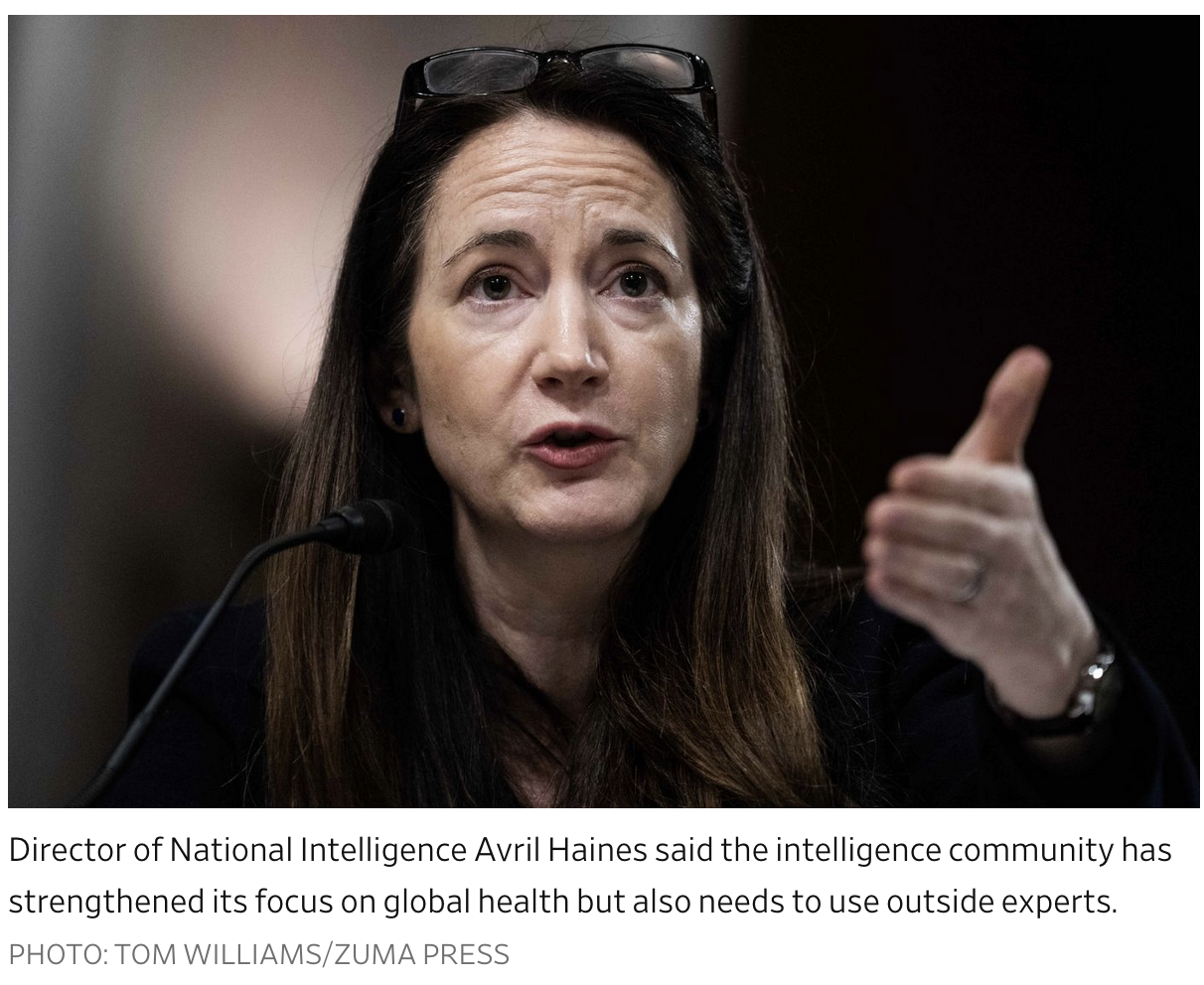

“There’s so much that’s changed in the threat landscape, and in the world that we’re operating in today,” Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines said in an interview.

She sketched out a broader, more institutionalized information exchange on a wider array of topics with the private sector, ranging from academia to local governments.

Illustrating the changing threats, a senior U.S. official said that the daily intelligence briefing prepared for President Biden and his top advisers—once dominated by terrorism and the Middle East—now regularly covers topics as varied as China’s artificial-intelligence work, the geopolitical impacts of climate change, and semiconductor chips.

The new strategy is meant to guide 18 U.S. intelligence agencies with an annual budget of about $90 billion whose work Haines coordinates.

The 16-page document, which contains no budget or program details, also says spy agencies must support the U.S. in its competition with authoritarian governments such as China and Russia, particularly in technological arenas.

On transnational threats such as financial crises, narcotics trafficking, supply-chain disruption and infectious diseases, the document calls on intelligence agencies to strengthen their internal capabilities to warn U.S. policymakers of looming threats.

A report last year by the House Intelligence Committee, at the time led by Democratic Rep. Adam Schiff, concluded that three years after the Covid-19 pandemic began, U.S. intelligence agencies still hadn’t made the changes needed to provide better warnings of future global health crises.

Haines said that the intelligence community has strengthened its focus on global health. Her office, she said, now has a senior official whose responsibilities include coordinating intelligence work on global health issues, has invested more resources and has strengthened outreach to organizations such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But the government, she said, also needs to rely on outside experts. Haines’ office brought in scientists and other specialists outside the government to help investigate the origins of the Covid pandemic and the health incidents affecting U.S. personnel abroad known as Havana Syndrome.

Such exchanges can be tricky. Many academics don’t want to be associated publicly with the intelligence community, said Haines, who has resisted efforts by Republican lawmakers to disclose the names of those consulted on the Covid question.

The emphasis on greater intelligence sharing is part of a broader trend toward declassification that the Biden administration has pursued. The United States has released unprecedented levels of formerly secret intelligence to warn of Russia’s plans in Ukraine and its quest for weapons from China, Iran and North Korea.

Updated: 10-13-2023

How Ads On Your Phone Can Aid Government Surveillance

Federal agencies buy bulk data, collected from ads you might never see, that can yield valuable information about you.

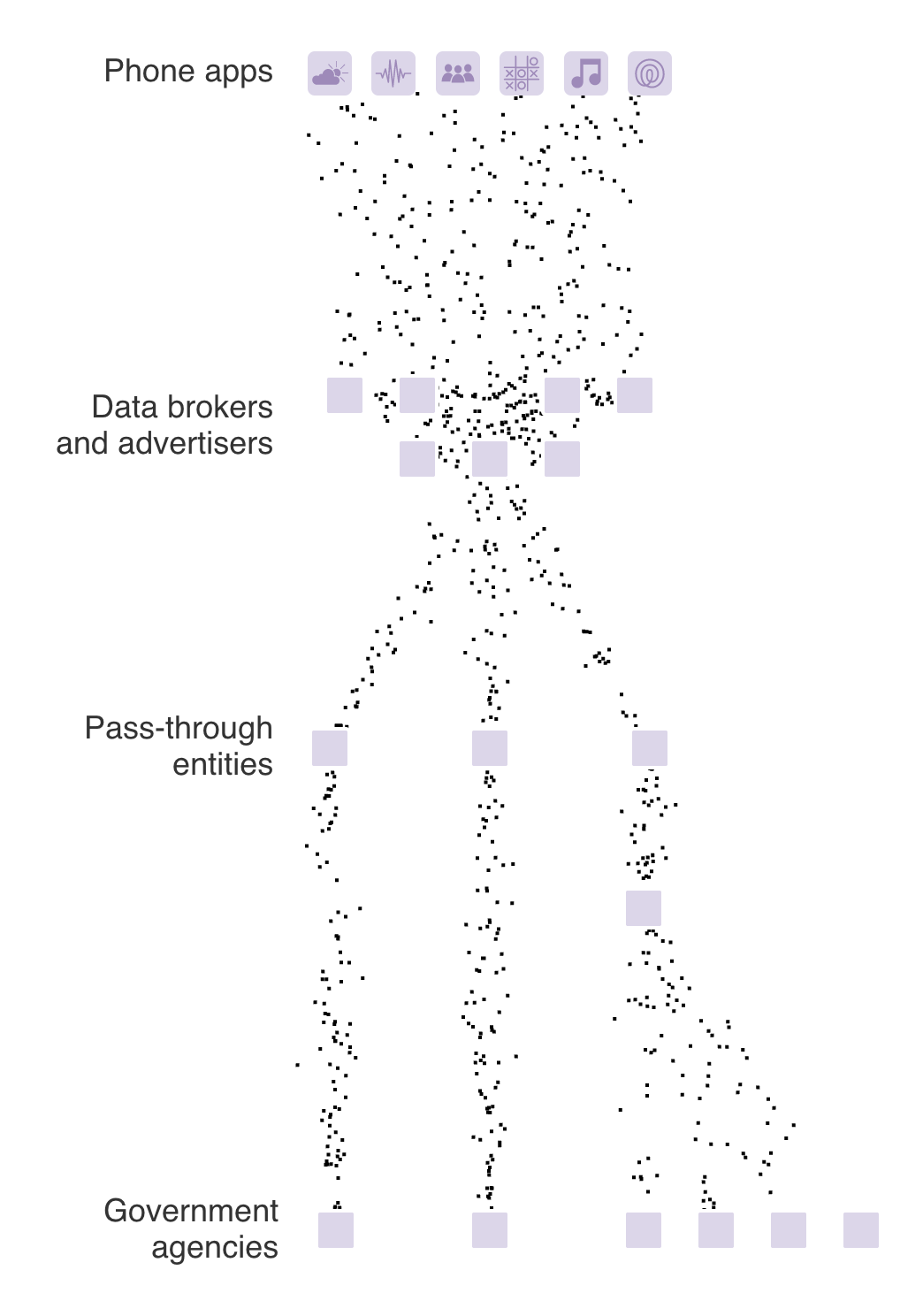

Technology embedded in our phones and computers to serve up ads can also end up serving government surveillance.

Information from mobile-phone apps and advertising networks paints a richly detailed portrait of the online activities of billions of devices. The logs and technical information generate valuable cybersecurity data that governments around the world are eager to obtain.

When combined with classified data in government hands, it can yield an even more detailed picture of an individual’s behaviors both online and in the real world.

A recent U.S. intelligence-community report said the data collected by consumer technologies expose sensitive information on everyone “in a way that far fewer Americans seem to understand, and even fewer of them can avoid.”

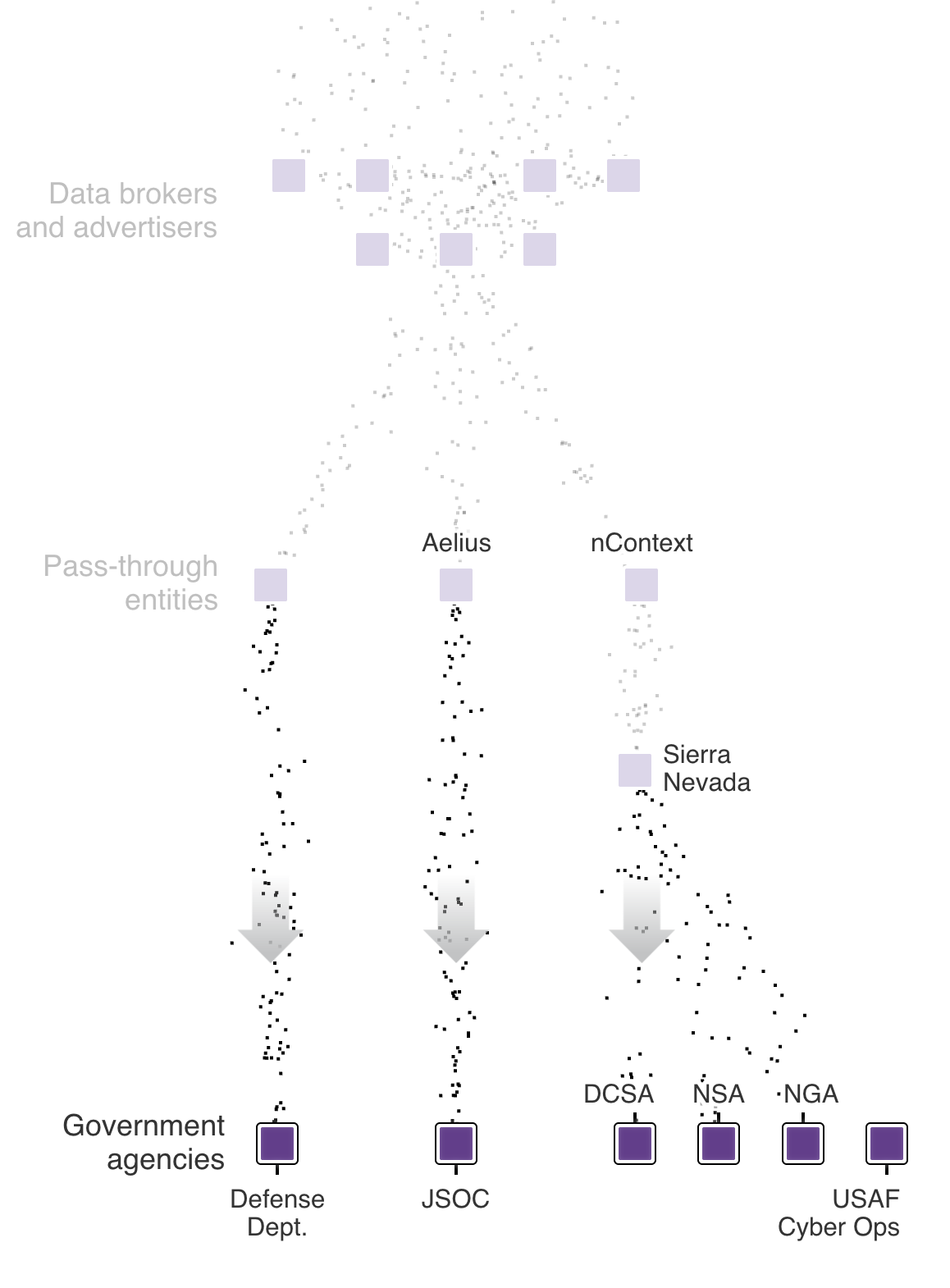

The Wall Street Journal identified a network of brokers and advertising exchanges whose data was flowing from apps to Defense Department and intelligence agencies through a company called Near Intelligence.

This graphic puts those specific examples in the context of how such commercially available information—bought, sold or captured by dozens of entities—can end up in the hands of intermediaries with ties to governments.

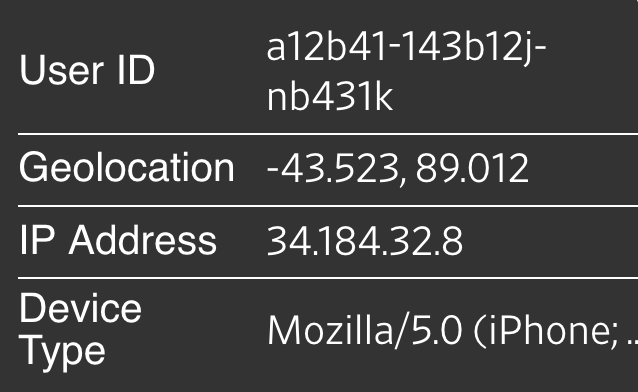

When you open an ad-supported app on your phone, your information is fed into a data stream that passes through many hands and has ended up in those of government agencies.

The moment before an app serves you an ad, thousands of advertisers compete for it to be their ad. While only one of the advertisers wins the spot, all the other advertisers in the bidding process are given access to information about your device.

Here’s an example of what that data looks like.

One of these apps collecting such data is Life 360, a family safety app, which generates a particularly rich set of information about the movement of devices. Until earlier this year, through brokers including Near Intelligence, some of that data ultimately ended up in the hands of government contractors.

A spokesman for Life360 said it has exited the data-brokerage business, adding that any sale of its data to government agencies violated its terms of service.

Mobile-phone information is collected by data brokers who are part of advertising exchanges and who repackage it for sale to their own customers. One such broker, Near Intelligence, had links to government contractors and used data from exchanges OpenX, Smaato and AdColony.

Those exchanges said they suspended data brokers who had violated their terms by collecting and reselling their data.

Additionally, some apps sell geolocation and other technical information about a device directly to data brokers. Mobfox and Tamoco, two brokers that sold such data to Near, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Another broker, SafeGraph, no longer sells data on people, a company spokesman said.

Data brokers sell data to each other. The Journal was able to trace flows of ad data from the data providers and ad networks as named in the graphic to one such company, Near Intelligence, that sold it on to others.

Until earlier this year, Near had several clients that were government contractors, according to people familiar with the matter. Its clients’ national-security contracts began with UberMedia, a U.S. company Near bought in 2021, according to the people and documents.

These contractors and pass-through entities then provide the cyber data to the U.S. government, where it may be used for cybersecurity, counterterrorism, counterintelligence and public safety.

Near Intelligence, based in India with offices in the U.S. and France, was until earlier this year obtaining data from other brokers and advertising networks.

It had several contracts with government contractors that were then passing that data to U.S. intelligence agencies and military commands, according to people familiar with the matter and documents reviewed by the Journal.

Near was surreptitiously obtaining data from numerous advertising exchanges, the people said, and claimed to have data about more than a billion devices. When contacted by the Journal, several ad exchanges said they have cut Near off for violations of their terms of service.

The exchanges told the Journal that their data is meant to help target ads, not for other purposes.

Privacy, legal and compliance specialists inside Near warned the company’s leadership that it didn’t have permission to save real-time bidding data and resell it this way, especially in the wake of tough new European privacy standards that came into place in 2018, the people said.

Those specialists also warned the company that indirect sales to intelligence-community clients were a reputational risk. Near’s leadership didn’t act on those warnings, the people said.

In an email viewed by the Journal, Near’s general counsel and chief privacy officer, Jay Angelo, wrote to CEO Anil Mathews that the company was facing three privacy problems.

“We sell geolocation data for which we do not have consent to do so…we sell/share device ID data for which we do not have consent to do so [and] we sell data outside the EU for which we do not have consent to do so.”

In another message, Angelo called the transfer of European Union data a “massive illegal data dump,” adding that the U.S. federal government “gets our illegal EU data twice per day.”

A spokesman for Near didn’t respond to questions about the messages. The company last week told the Securities and Exchange Commission that Mathews and several other executives had been placed on administrative leave while the board investigates allegations of financial wrongdoing.

The spokesman didn’t say whether the matter was related to Near’s sale of ad-tech data to government contractors.

In a statement, Angelo said Near had over the past year “taken deliberate measures to safeguard privacy,” including ending customer relationships that were inconsistent with its values, which forbid Near’s data from being used for law enforcement, tracking or surveilling. Near didn’t make him available for an interview.

“We are continuously improving our systems for preventing misuse of our data by customers,” Near said in a statement.

Other brokers that compete with Near also have done robust business with government contractors, the Journal has previously reported.

Many Near staff were told that the agreements with government contractors were for “humanitarian purposes,” people said. Advertising exchanges it worked with told the Journal they had no knowledge of Near asking permission to license their data to a government entity, which wasn’t allowed under their agreements with the company.

In another instance, Near contracted with a government-linked client, nContext, that described itself as a digital-marketing company, highlighting commercial work on its website for clients such as a Philadelphia cultural center and New York City’s 92nd Street Y.

Corporate ownership records show nContext is a wholly owned subsidiary of defense contractor Sierra Nevada. Federal contracting records show that nContext is a subcontractor on several large intelligence and defense data contracts.

The Defense Counterintelligence Security Agency, part of the Defense Department, confirmed it signed a contract with Sierra Nevada in 2020 in an effort “to better analyze publicly available data and government information to identify cyber threats to cleared contractors.”

A pilot program the following year included ad data supplied by nContext but was discontinued, a spokeswoman said, adding: “DCSA did not collect any information that would identify people.”

Sierra Nevada and nContext didn’t respond to requests for comment. Another government contractor that was licensing Near’s data, Aelius, also didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, also part of the Defense Department, lawfully procured data and services from commercial vendors to support a “wide variety of missions” including foreign intelligence, humanitarian assistance and navigational safety, a spokeswoman said, and an Air Force spokeswoman said cyber and intelligence personnel use publicly available information “in an ethical and legal manner to understand an-ever changing data landscape that could be used by foreign malicious cyber actors to erode U.S. national security.”

The National Security Agency declined to comment. The Defense Department declined to comment on the contract with Joint Special Operations Command.

The U.S. has no comprehensive national privacy law, and therefore no outright prohibition on the collection and resale of such data to private- or public-sector entities.

While such contracts for commercially available information are generally unclassified and require no special authority, its use by U.S. agencies for national-security purposes was until recently a closely held secret.

The U.S. intelligence-community report, made public in June and produced by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, said there is commercially available information “on nearly everyone that is of a type and level of sensitivity that historically could have been obtained” through targeted collection methods such as wiretaps, cyber espionage or physical surveillance.

Now ODNI is completing a framework to govern U.S. intelligence agencies’ use of such information, said spokeswoman Nicole de Haay.

“We will publicly share as much of this framework as possible,” she said.

Updated: 12-16-2023

AI Is Replacing 007 In The Espionage Arms Race

A conversation with Harvard’s Calder Walton about spies, lies and big data.

Folks who think about such things tend to look at the great espionage battle between the US and the Soviet Union as covering the four decades of the Cold War — the heady days of the Rosenbergs, the Wall, the Cuban Missiles and the owlish George Smiley.

But in truth, as Calder Walton reminds us in his remarkable new book Spies: The Epic Intelligence War Between East and West, a struggle that began after the Russian Revolution in 1917 is with us to this day.

Walton obsessively and entertainingly documents this century of the clandestine warfare, and reminds us that this contest didn’t waver during the brief enemy-of-my-enemy Alliance during World War II or in the immediate aftermath of the Soviet collapse, a period “Slow Horses” author Mick Herron memorably calls “the blissful break when the world seemed a safer place, between the end of the Cold War and about ten minutes later.”

Walton, a Brit who was born in the US, is the assistant director of the Harvard Belfer Center’s Applied History Project and Intelligence Project and a self-proclaimed “recovering barrister.” He is also quite fortunate:

While a graduate student at Cambridge University, he was selected to help research the official history of the British Security Service, or MI5.

We recently had a long discussion on how the lessons of that first Cold War can be applied (and misapplied) to the new one the US faces against China and its junior partner in Moscow. Below is a lightly edited transcript of the first part of that conversation. The second will follow in a future installment.

Tobin Harshaw: We of course need to talk about weighty geopolitical issues eventually, but let’s start with the fun stuff: How did you end up taking part in the official MI5 history?

Calder Walton: Right place, right time. My Ph.D. adviser at Cambridge University, Christopher Andrew, was selected as MI5’s authorized historian. And he said, hey, do you want to do some part-time research at the archives in MI5’s headquarters? It was too much of an opportunity to pass up.

TH: Indeed. What were those archives like? Or is it one of those “I could tell you but then I’d have to kill you” situations?

CW: If only! More Agatha Christie than 007, but it was certainly exciting. With British historic records, you open the file and it just tells the story of the person or the thing under investigation. For good and bad.

And it’s all meticulously a John le Carré-type affair: women typing up tapped telephone calls, bugged conversations, and so on.

And so the files invariably spill out compelling narratives of the people under investigation. Little wonder that some of the best espionage writers, like Graham Greene and le Carré, were British intelligence officers. They knew the land.

TH: How has the CIA done in comparison?

CW: The CIA is the world’s preeminent intelligence agency, but they’ve got some work to do in terms of releasing user-friendly dossiers. The declassified records on their website are difficult to use, and while you can find individual reports, they’re snippets; it’s not like with MI5, where you open a dossier, which tells a story.

TH: You write that even with its dwindling global influence and military since World War II, the UK has stayed in the geopolitical game because of the intelligence services. Is it just James Bond?

CW: Some of this is certainly explained by the James Bond effect — a first-class reputation — so the UK punches way above its weight. But I think it’s also down to genuine expertise, especially in areas like codebreaking. After all, the British essentially did the unthinkable in the Second World War.

TH: Bletchley and the Enigma machine.

CW: Right. And in the postwar years, the UK made itself indispensable to the US in terms of collection capabilities and decryption.

The US didn’t much like British colonialism, for obvious reasons, but Washington realized that having signals interception bases in Hong Kong, in Singapore, Cyprus, East Africa, in West Africa were incredibly useful in the context of the Cold War.

Britain’s declining empire became invaluable for the US.

The relationship was so intertwined that in the early 2000s, the UK’s signals intelligence agency, GCHQ, and the US National Security Agency acted as backup for each other. If NSA went down, a massive power cut or whatever, everything would just go over to GCHQ, and vice-versa. In the history of intel, there’s nothing else like that.

TH: So the whole le Carré thing about UK spies hating the “the cousins” at the CIA isn’t entirely true?

CW: The world of le Carré lies more with human intelligence, so MI6 rather than GCHQ. I was born in the US, and le Carré’s anti-Americanism does get tiresome pretty quickly. But yes, in reality there’s a love-hate, and that even shows up in the records. America’s got more resources, they’ve got more money. Begrudging respect and jealousy.

TH: I’ve heard from many people how high-quality British intelligence was in preparing for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

CW: That’s been borne out by a UK Parliamentary Intelligence Security Committee report published just a couple of days ago. In particular, GCHQ’s intelligence collection on Russian targets showed unambiguously that Putin’s buildup wasn’t a masking or just a show of force — that they actually meant what they were doing.

Do you remember the stories of Russian surgeons being brought toward the front line? This wouldn’t happen if it was just an exercise. And reading between the lines, GCHQ was all over that.

The British and the US worked together to declassify for the public intelligence on Putin’s war plans. This was not unprecedented — the US declassified intelligence during the Cuban Missile Crisis, for example. But on Ukraine, they did so in a striking way, in near-real time. It was a real game changer.

TH: Which brings us to open-source intel.

CW: Yes. What was available commercially gave the intelligence communities on both sides of the Atlantic the ability to say: We can get that information out without betraying our intelligence sources and methods.

TH: In the book, you say that during the Cold War, about 80% of US intelligence was derived from clandestine collection, and just 20% from open sources. But now it’s flipped to 80-20 the other way?

CW: Yes. There will continue to be a narrow but very deep margin of what intelligence communities can do in the traditional, clandestine, sense. A well-placed source in the Kremlin, in Beijing, etc.

But so much is now available through open sources that Western services are struggling to figure out what their role is in this changed world. Is it to try to do everything, or are they just going to be more conservative and concentrate on what open source cannot deliver?

Whatever happens, the age of a traditional secret service is over.

TH: Meanwhile, China’s hoovering everything up.

Collect, collect, collect. That’s their strategy. What they’re going to do with all of that is anyone’s guess. The intelligence struggle between China and the West is built around a race for machine learning, artificial intelligence, and quantum computing — it’s a race to process data.

Whoever masters AI will be able to master the data that’s been collected. And in the West, it will not be governments to do that. It will be the private sector. We’re thus at this watershed moment of redefining the nature of intelligence and national security. Intelligence communities are by necessity having to bridge gaps with the private sector. Quite how that will come out is anyone’s guess.

I’d be hugely in favor of the US intelligence community setting up a single open-source intelligence agency, and having it collaborate with all the clandestine agencies, rather than each individual agency trying to do open source itself.

TH: Is there a Cold War model for that?

CW: There is not. Although I argue in “Spies” that we are in a new Cold War, I think it’s important not to be shackled by the old Cold War, being stuck in the past.

That said, there are precedents for using open source effectively. The CIA’s Foreign Broadcast Information Service for example, which trawled through Soviet state media.

TH: That did really good work exposing Soviet propaganda efforts, like what the Kremlin made up about America cooking up AIDS in a lab. But now we didn’t respond nearly as well to the Covid misinformation that came out of China, for example.

CW: Looking at it from a historical perspective, it’s the same bloody conspiracy theory. The CCP is alleging that Covid was designed and let loose in the same lab in Maryland where the Soviets said AIDS was created. What’s old is new again.

TH: So why can’t we respond successfully today?

CW: First of all, it was a simpler time in the analog pre-digital era.

TH: Now we have social media.

CW: Exactly. Consider the mechanics of how Soviet intelligence spread disinformation: The story goes out in an obscure journal, a couple of months later it gets picked up more broadly — trickle, trickle, trickle — then some “useful idiots” in the West repackage it. It’s all very slow, and the Kremlin didn’t know whether a fabricated story was going to take off.

But now, obviously, everything travels at the speed of light. It’s easier, cheaper, quicker to spread disinformation than ever before. But it’s also more difficult for the authoring state to control the narrative. Once it’s out, where does it end up?

TH: In terms of open source and AI, you say we need to have public-private cooperation. But, as in the Cold War, I would imagine we need think tanks and universities as well.

CW: A bridge, yes.

TH: Whereas the Chinese are going to go about this the Chinese way, through centralized control. We like our model. We think it always wins in the end.

CW: That’s right.

TH: Should we have that much confidence today?

CW: Well, democracies have stood the test of time so far. Democracy is the least bad form of government compared to every other, to paraphrase Churchill. As for our model, do you mean our Western way of life, or just in terms of information warfare?

TH: Both. But in terms of us looking at national security in general, there’s a role for the federal government, there’s a role for universities, there’s a role for Silicon Valley today. It’s a collaborative Western-style effort as opposed to being a centralized one.

CW: Absolutely. I think we will prevail. I have full confidence in it. But we’ve got our work cut out for us.

Updated: 12-25-2023

China Is Stealing AI Secrets To Turbocharge Spying, U.S. Says

U.S. officials are worried about hacking and insider theft of AI secrets, which China has denied.

On a July day in 2018, Xiaolang Zhang headed to the San Jose, Calif., airport to board a flight to Beijing. He had passed the checkpoint at Terminal B when his journey was abruptly cut short by federal agents.

After a tipoff by Apple’s security team, the former Apple employee was arrested and charged with stealing trade secrets related to the company’s autonomous-driving program.

It was a skirmish in a continuing shadow war between the U.S. and China for supremacy in artificial intelligence. The two rivals are seeking any advantage to jump ahead in mastering a technology with the potential to reshape economies, geopolitics and war.

Artificial intelligence has been on the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s list of critical U.S. technologies to protect, just as China placed it on a list of technologies it wanted its scientists to achieve breakthroughs on by 2025. China’s AI capabilities are already believed to be formidable, but U.S. intelligence authorities have lately made new warnings beyond the threat of intellectual-property theft.

Instead of just stealing trade secrets, the FBI and other agencies believe China could use AI to gather and stockpile data on Americans at a scale that was never before possible.

China has been linked to a number of significant thefts of personal data over the years, and artificial intelligence could be used as an “amplifier” to support further hacking operations, FBI Director Christopher Wray said, speaking at a press conference in Silicon Valley earlier this year.

“Now they are working to use AI to improve their already-massive hacking operations using our own technology against us,” Wray said.

China has denied engaging in hacking into U.S. networks. Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin said this summer that the U.S. was the “biggest hacking empire and global cyber thief” in the world, in response to allegations that Beijing had hacked into the unclassified email systems of several top-level Biden administration officials.

A spokesman at the Chinese Embassy in Washington didn’t respond to requests for comment.

In recent years, the FBI’s interest in protecting American innovations in the area has more squarely targeted manufacturers of chips powerful enough to process artificial-intelligence programs, rather than on artificial-intelligence companies themselves.

Even if insiders or hackers were able to steal algorithms underpinning an advanced system today, that system could be obsolete and overtaken by larger advancements by other engineers in six months, several former U.S. officials said.

In 2022, the chip-manufacturing technology supplier Applied Materials sued a China-owned rival, Mattson Technology, alleging that a former Applied engineer stole trade secrets from Applied before leaving for Mattson.

The case attracted the interest of federal prosecutors, although no criminal charges have been filed, according to people familiar with the matter.

Mattson hasn’t been contacted by any federal agency over the matter, and there is no evidence that any Applied information taken was ever used by Mattson, a company spokesman said.

Mattson, based in Fremont, Calif., was acquired in 2016 by an investment arm of the city of Beijing, which currently owns about 45% of the company, the spokesman said.

The case remains in litigation. In November, Mattson sued Applied, claiming that engineers at Applied had applied for patents using intellectual property developed while they were working at Mattson.

Fears of how China could use AI have grown so acute over the past year that the FBI director and leaders of other Western intelligence agencies met in October with technology leaders in the field to discuss the issue.

Makers of AI technology are concerned about their secrets making their way to China, too, according to executives at these companies.

Recently, OpenAI reached out to the FBI after a forensic investigation of a former employee’s laptop raised suspicions that the employee had taken company secrets to China, according to people familiar with the company. The employee was later exonerated, according to a person familiar with the matter.

U.S. intelligence analysts have worried for years about the long-tail espionage dividends that China is believed to be reaping from amassing enormous troves of hacked personal information belonging to American officials and business executives.

Over the past decade, Beijing has been linked to the hacks of hundreds of millions of customer records from Marriott International, the credit agency Equifax and the health insurer Anthem (now known as Elevance Health), among others, as well as more than 20 million personnel files on current and former U.S. government workers and their families from the Office of Personnel Management.

The heists were so huge and frequent that Hillary Clinton, then a Democratic presidential candidate, accused China of “trying to hack into everything that doesn’t move.” China has denied responsibility for each of those heists.

China was so good at stealing private information—billions of pieces of data in all, according to U.S. officials, criminal indictments and cyber-threat researchers—that its hackers had likely collected too much of a good thing: an informational treasure trove so vast that humans would be incapable of locating the right patterns.

Artificial intelligence, however, would have no such limitations.

Microsoft believes China is already using its AI capabilities to comb these vast data sets, said Brad Smith, the company’s president, in an interview with The Wall Street Journal.

“Initially the big question was did anyone, including the Chinese, have the capacity to use machine learning and fundamentally AI to federate these data sets and then use them for targeting,” he said. “In the last two years we’ve seen evidence that that, in fact, has happened.”

Smith cited the 2021 China-linked attack on tens of thousands of servers running Microsoft’s email software as an example. “We saw clear indications of very specific targeting,” he said.

“I think we should assume that AI will be used to continue to refine and improve targeting, among other things.” Smith didn’t address the issue of AI technology being stolen by China.

In the 2018 case, the former Apple employee Zhang pleaded guilty to stealing trade secrets and is set to be sentenced in February. His plea agreement is under seal. Apple declined to comment.

U.S. authorities believe Chinese intelligence operatives are correlating sensitive information across the databases they have stolen over the years from OPM, health insurers and banks—including fingerprints, foreign contacts, financial debts and personal medical records—to locate and track undercover U.S. spies and pinpoint officials with security clearances.

Passport information stolen in the Marriott hack could help spies monitor a government official’s travel, for example, counterintelligence analysts have said.

“China can harness AI to build a dossier on virtually every American, with details ranging from their health records to credit cards and from passport numbers to the names and addresses of their parents and children,” said Glenn Gerstell, a former general counsel at the National Security Agency.

“Take those dossiers and add a few hundred thousand hackers working for the Chinese government, and we’ve got a scary potential national security threat.”

Although executives including Smith are concerned by the weaponization of AI, they point out that this technology can be used to spot and mitigate attacks, too.

“We believe that if we do our work well and we’re determined to do our work well, we can use AI as a more potent defensive shield than it can be used as an offensive weapon,” Smith said. “And that’s what we need to do.”

Updated: 1-29-2024

There’s So Much Data Even Spies Are Struggling To Find Secrets

Scouring open-source intelligence may not have the same cachet as undercover work, but it’s become a new priority for the US intelligence agencies.

Spying used to be all about secrets. Increasingly, it’s about what’s hiding in plain sight.

A staggering amount of data, from Facebook posts and YouTube clips to location pings from mobile phones and car apps, sits in the open internet, available to anyone who looks. US intelligence agencies have struggled for years to tap into such data, which they refer to as open-source intelligence, or OSINT. But that’s starting to change.

In October the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, which oversees all the nation’s intelligence agencies, brought in longtime analyst and cyber expert Jason Barrett to help with the US intelligence community’s approach to OSINT.

His immediate task will be to help develop the intelligence community’s national OSINT strategy, which will focus on coordination, data acquisition and the development of tools to improve its approach to this type of intelligence work. ODNI expects to implement the plan in the coming months, according to a spokesperson.

Barrett’s appointment, which hasn’t previously been reported publicly, comes after more than a year of work on the strategy led by the Central Intelligence Agency, which has for years headed up the government’s efforts on OSINT.

The challenge with other forms of intelligence-gathering, such as electronic surveillance or human intelligence, can be secretly collecting enough information in the first place. With OSINT, the issue is sifting useful insights out of the unthinkable amount of information available digitally.

“Our greatest weakness in OSINT has been the vast scale of how much we collect,” says Randy Nixon, director of the CIA’s Open Source Enterprise division.

Nixon’s office has developed a tool similar to ChatGPT that uses artificial intelligence to sift the ever-growing flood of data. Now available to thousands of users within the federal government, the tool points analysts to the most important information and auto-summarizes content.

Government task forces have warned since the 1990s that the US was at risk of falling behind on OSINT. But the federal intelligence community has generally prioritized information it gathers itself, stymying progress.

“You build your career on the idea that you have to obtain information covertly,” says Senator Mark Warner, the Virginia Democrat who chairs the chamber’s Intelligence Committee. “It’s a mindset change to say, ‘OK, no, I think we can learn just as much from open-source information.’”

Failing to develop new capabilities for using open data could be costly and even dangerous, say US policymakers and intelligence experts. OSINT is especially important when it comes to gathering information about the Chinese government, whose political system is highly compartmentalized and difficult to penetrate with human agents.

Michael Morell, who served two stints as acting director of the CIA during the Obama administration, says identifying and making more open-source information available to analysts would significantly improve the performance of the US intelligence community.