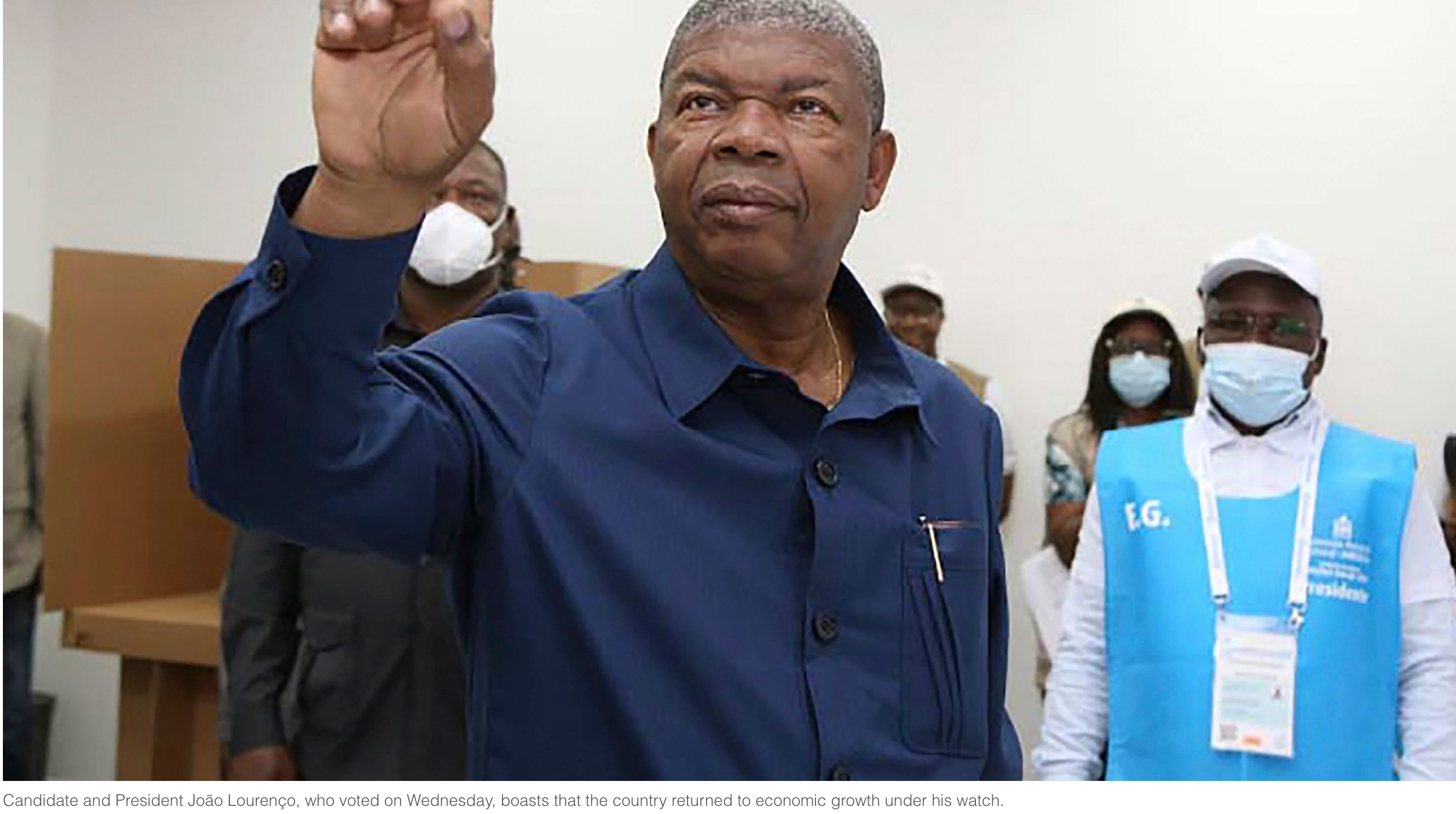

US Doesn’t Have The Money To Match Beijing’s “Belt-and-Road” Initiative (#GotBitcoin)

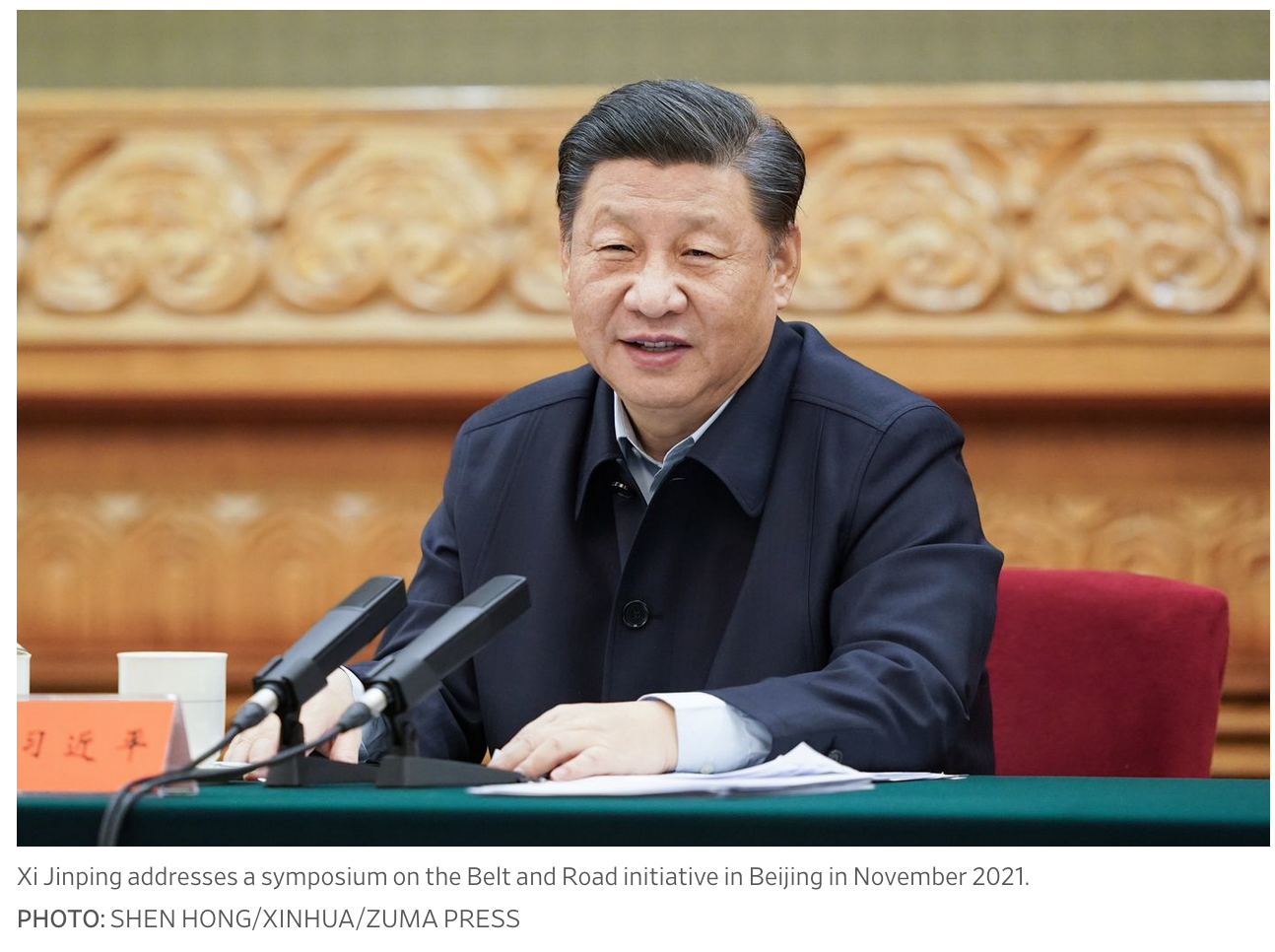

Xi Jinping, looking to expand global program—and responding to criticism—invites multilateral input. US Doesn’t Have The Money To Match Beijing’s “Belt-and-Road” Initiative (#GotBitcoin)

China has unleashed easy credit for more than five years to fuel its ambitions to build global infrastructure, heaping debt upon itself and other developing economies.

Related:

To Counter China, U.S. Looks to Invest Billions More Overseas

Russia, Sri Lanka And Lebanon’s Defaults Could Be The First Of Many

China Outspends US When It Comes To Building The World’s Infrastructure

President Xi Jinping is now adjusting that strategy, pledging to reformulate his Belt and Road Initiative with greater emphasis on market principles and sustainability.

The U.S. and other countries have warned that aspects of the program pose financial risks to borrowers, alleging a lack of transparency and graft in deals that primarily benefit Beijing.

China doesn’t intend to go it alone, Mr. Xi said in a speech on Friday. He referred repeatedly to “Belt and Road cooperation,” inviting foreign and private-sector partners to play a bigger role.

“Going ahead, we should focus on priorities and project execution,” Mr. Xi said, “just like an architect refining the blueprint.”

His pledges at a Beijing forum, where he hosted three dozen foreign leaders, marked the highest-level acknowledgment that China’s efforts to export its speedy, government-led brand of development carry risks for participating countries, and itself.

While many developing countries have embraced Mr. Xi’s infrastructure program since its 2013 launch, doubts have festered over whether the primarily Chinese-funded and built projects are always worth the money.

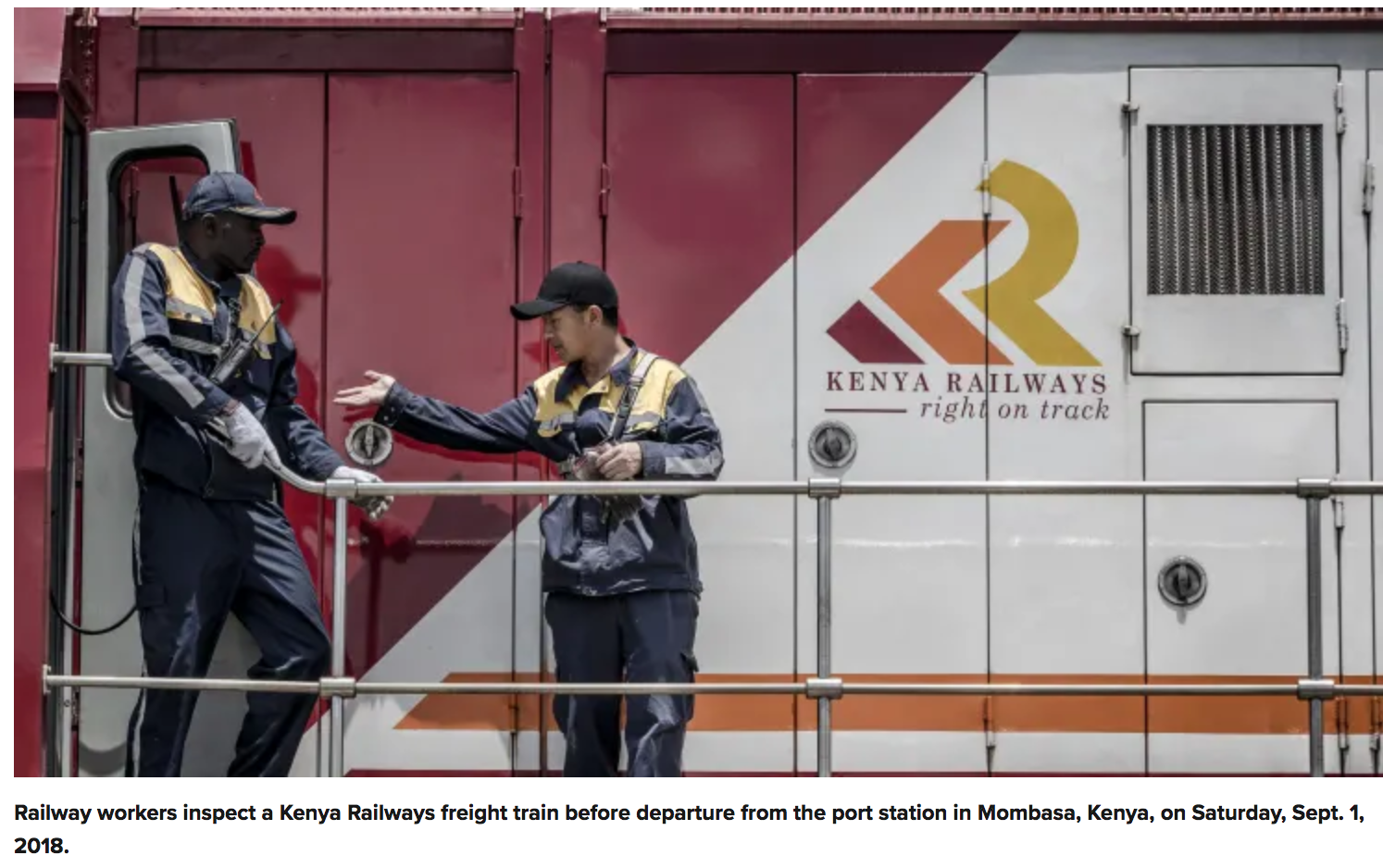

In Pakistan, heavy debt associated with Chinese projects helped sway an election, while the cost of a highway in Montenegro has threatened to devour its budget. Kenya has argued that Chinese infrastructure building hasn’t created many jobs for locals, while Malaysia recently negotiated a one-third cut in the price of a railway project its officials suggested originated due to graft.

Those challenges are mounting amid pushback from the U.S. about how Beijing wants to reshape the global order and as China’s debt-heavy domestic economy faces new trouble.

Far from abandoning an initiative he has enshrined in his Communist Party’s governing charter, Mr. Xi outlined a more expansive definition of Belt and Road, stretching it beyond infrastructure-building into areas including international cooperation in education and media.

‘We need to pursue open, green and clean cooperation,” he said in his Friday speech.

Mr. Xi also called for more multilateral and commercial funding for infrastructure projects, a contrast to his pledges of Chinese financing in a similar speech two years ago.

Beijing is fine-tuning Belt and Road, according to Zhang Zhexin, an analyst at Shanghai Institutes for International Studies. Its initial presentation was too broad and too loud, he said, and participating countries—often in distress—saw the program as a source of easy money from China.

“China just doesn’t have the resources to fulfill everyone’s demand,” Mr. Zhang said.

First pitched in 2013 as a platform to spur global development, the Belt and Road Initiative has pushed China’s massive construction, telecommunications and shipping companies to go global as a cooling domestic economy reduces business at home.

But as the program ballooned beyond infrastructure construction, Western officials—including from the U.S., which snubbed the Belt and Road forum—blamed it for advancing opaque financial deals that give Beijing political leverage by burdening countries with debt to China.

As criticism built over the past year or so, Beijing de-emphasized big-ticket infrastructure projects in its Belt and Road publicity and stepped up pledges to ensure sustainable lending and fight graft.

“Everything should be done in a transparent way and we should have a zero tolerance for corruption,” Mr. Xi said Friday.

As part of the oversight effort, Chinese officials have been negotiating with foreign governments to draw up lists of official Belt and Road projects, people familiar with the matter said, a move that would curb misuse of the Belt and Road label.

Ahead of Mr. Xi’s speech on Friday, Chinese officials appeared at side seminars to stress their attention to financial risks in the program and their desire to attract private-sector money.

“A country’s total debt capacity should be taken into account,” Yi Gang, governor of the People’s Bank of China, told a seminar on Thursday. “Private lending should be the mainstay” in financing projects to achieve sustainable development, he said.

International Monetary Fund Managing Director Christine Lagarde welcomed the shift in tone, telling the forum after Mr. Xi’s speech that the initiative could “benefit from increased transparency, open procurement with competitive bidding and better risk assessment in project selection.”

Some observers don’t expect China to slim down the Belt and Road program, despite Mr. Xi’s pledged adjustments.

Recalibrating Mr. Xi’s signature foreign policy is a welcome move but also “a big ask,” said George Magnus, an economist at Oxford University’s China Center. “To change its structure by incorporating Western ideas and values including the rule of law, full and open accounting, and market-based transparent lending standards and terms is most likely a bridge too far.”

China is adapting to current circumstances, but its long-term goals remain unchanged, said Kishore Mahbubani, a former senior Singapore diplomat who was in the audience for the Chinese leader’s speech. “They’re still rich in capital.”

Beijing’s more circumspect public messaging belied its highhanded approach when negotiating with some foreign diplomats during preparatory meetings for the forum, people familiar with the process said.

In meetings to draft a joint statement for Mr. Xi’s Saturday summit with foreign leaders, a Chinese diplomat chastised some negotiators, particularly European officials, after they pressed for references to best practices in business and investment, as well as human rights, the people familiar with the process said.

Guo Xuejun, a deputy director-general at China’s Foreign Ministry who chaired the meetings, accused the negotiators of showing disdain for Mr. Xi and China. He dismissed European requests for references to reciprocity as “American language,” referring to similar U.S. demands in trade talks with China, the people said.

“Remind me to disinvite your president,” Mr. Guo said at one point, according to the people, who said Chinese officials lodged diplomatic complaints against countries that sought amendments it disliked. China’s Foreign Ministry didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Updated: 1-16-2020

China Touts Its Belt-and-Road Effort As Collaborative, But Foreign Companies Feel Left Out

Beijing ‘is offering the financing, the building, the equipment—even the labor,’ an EU Chamber of Commerce official says.

Roughly seven years after Beijing launched a high-profile transcontinental infrastructure program aimed at building goodwill abroad and boosting economic cooperation with the rest of the world, some foreign companies say they are being left out of those projects.

Not only have a minuscule number of foreign companies been invited to participate in China’s Belt and Road initiative—a trillion-dollar flagship foreign-policy effort—but Beijing has also undercut its message of cooperation by keeping many partner nations at arm’s length, a new study by the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China argues. The initiative focuses mainly on infrastructure projects.

“China is offering the financing, the building, the equipment—even the labor,” said Jörg Wuttke, president of the Beijing-based European trade group. “That is a very closed system.”

China has framed the Belt and Road initiative as a way to more closely integrate its economy with those across Asia, Africa, Europe, the Middle East and Latin America, primarily through infrastructure projects. That has earned it comparisons to the Marshall Plan, under which Washington gave billions of dollars to help rebuild swaths of Europe and which placed the U.S. at the center of the postwar economic order.

During the first 11 months of 2019, Chinese companies signed 6,055 contracts in 61 countries as part of Belt and Road with a total value of $127.67 billion, an increase of 41.2% from the same period a year earlier, according to China’s Commerce Ministry.

The Belt and Road effort, however, has attracted criticism alleging that it lacks of transparency on financing, leading to charges of corruption, waste and out-of-control debt. President Xi Jinping has responded in part by recalibrating his signature program, pledging more transparency and financial sustainability.

However, the European Chamber, in its report published Thursday, said some apparently successful Belt and Road projects relied on large Chinese subsidies to stay afloat, quoting one logistics company that detailed handouts that heavily distorted market prices for freight traffic between Western China and Europe.

The trade group counted that just 20 of its 1,700 member companies in China had participated in the initiative. Those that did so joined because of existing relationships with the Chinese government or to lend technology expertise that couldn’t be supplied by Chinese companies, the chamber said.

Most of the participating companies did so through joint ventures with Chinese state-owned companies and in almost all cases held a small minority share in the project. Others had bid on Belt and Road-related projects, though very few were awarded the project, said the report, which pointed out the lack of an office or even a phone number for the initiative.

Geng Shuang, a Foreign Ministry spokesman, dismissed the European Chamber’s report as biased, saying the initiative was launched in a spirit of openness, inclusiveness and transparency.

Under the Belt and Road initiative, “Chinese and foreign companies follow the market rules and principle of fairness,” Mr. Geng said Thursday. He listed Germany’s Siemens and Deutsche Post’s DHL business, as well as France’s Schneider Electric, as examples of participating European businesses.

Siemens, which was among the first Western companies to work with Chinese companies on Belt and Road projects, opened an office in 2018 to oversee its involvement in the plan.

While some U.S. companies have shown interest, few have gotten directly involved. Most notable among them is General Electric Co., GE -0.25% which has partnered with Chinese state-owned enterprises on power-plant and grid projects in Africa. In July, Larry Culp, GE’s chairman and chief executive, met with Hao Peng, chairman of the body that oversees China’s state-owned assets, to discuss the Belt and Road initiative.

Some of the Belt and Road’s advertised participants had been only retroactively labeled as joining the effort, the European Chamber said. When a Chinese consortium won a bid in 2018 to build a bridge in Croatia as part of an EU-funded initiative to create transport, energy and digital connections between Europe and Asia, the Chinese news media were quick to laud it as a part of the Belt and Road initiative.

Updated: 6-11-2020

China’s Trillion-Dollar Campaign Fuels A Tech Race With The U.S.

Beijing plans to spend $1.4 trillion in the next five years in sectors including 5G, artificial intelligence and data centers.

China has embarked on a new trillion-dollar campaign to develop next-generation technologies as it seeks to catapult the communist nation ahead of the U.S. in critical areas.

Since the start of the year, municipal governments in Beijing, Shanghai and more than a dozen other localities have pledged 6.61 trillion yuan ($935 billion) to the cause, according to a Wall Street Journal tally. Chinese companies, urged on by authorities, are also putting up money.

Under a plan outlined earlier this year by China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, these efforts would contribute to at least $1.4 trillion in investments during the next five years in artificial intelligence, data centers, mobile communications and other projects.

At China’s annual legislative meeting last month, China’s Premier Li Keqiang said the campaign was a top priority of the Communist Party and would give the country a “new-style infrastructure.”

That marked a subtle shift from months earlier, when Chinese leaders played down their previous industrial policy, known as Made in China 2025. The Trump administration has pointed to that previous policy as evidence of Beijing’s intent to subsidize national champions and tilt the playing field against foreign companies.

A key aspect of Made in China revolved around replacing foreign tech components with local products, said Caroline Meinhardt, an analyst at the Mercator Institute for China Studies in Berlin. That goal hasn’t changed, even though the new plan doesn’t explicitly call for a similar push, she said.

China’s program is likely to add heat to the U.S.-China technology race as Beijing seeks a global edge in construction of superfast cellular networks known as 5G. It could also serve as an important source of economic stimulus to cushion the impact of the global coronavirus-related slowdown.

“China is still a heavily planned economy,” said Lester Ross, policy committee chairman at the American Chamber of Commerce in China. “Such plans are a significant driver of economic policies.”

The new campaign has a similar thrust to Made in China 2025, but is both more targeted at cutting-edge technologies and broader in its ambitions. It focuses on upgrading technology throughout the Chinese economy and relies mostly on investment from the private sector and local governments instead of national government spending.

Unlike utilities and roads, new-style infrastructure investments such as vehicle charging stations offer better returns for private investors, Sun Guojun, a senior official with China’s cabinet, the State Council, said at a news conference in late May. The central government would provide policy support to the campaign, partly as a bid to increase domestic demand, Mr. Sun said.

This week, Chinese cities Beijing and Guangzhou announced new spending and projects related to the plan. Beijing aims to build 13,000 new 5G base stations by the end of 2020, while Guangzhou officials said they would increase spending to 500 billion yuan, up from 180 billion yuan announced previously, according to the city’s government work report.

The government is pushing hardest for investment in building new 5G networks. Supercharged 5G mobile connections are expected to underpin a whole new world of next-generation connected devices, collectively known as the internet of things, that businesses believe could revolutionize daily life and manufacturing alike.

China hopes to more than triple the number of 5G base stations to 600,000 by the end of the year, according to the state-run Xinhua News Agency. In 2019, Bernstein Research said the U.S. was on pace to install 10,000 5G base stations by the end of that year.

In March, China’s three national telecom carriers collectively promised to invest about 220 billion yuan to build 5G base stations.

The rest of the money is slated to flow into the building of new data centers and intercity rail networks, development of homegrown artificial intelligence chips, smart factories, electric-vehicle charging stations and ultrahigh-voltage power facilities.

Local governments have rushed to announce their investments. Shanghai’s government said this April it would pump 270 billion yuan on artificial intelligence, the industrial internet of things and other advanced technologies. Neighboring Jiangsu province said it plans to invest 182 billion yuan in its own new infrastructure projects.

Tencent, which runs China’s popular do-everything app WeChat, said last month it would invest 500 billion yuan during the next five years in new infrastructure technologies like cloud computing and cybersecurity. Its rival, e-commerce giant Alibaba, pledged 200 billion yuan in similar outlays over three years.

In his work report last month, Mr. Li said the government planned to issue 3.75 trillion yuan in bonds and spend another 600 billion yuan to support the digital infrastructure push, as well as accelerate urbanization and upgrade traditional infrastructure like roads and bridges.

Preferential policies favoring Chinese companies mean foreign companies are unlikely to see much of a windfall from the campaign, foreign business groups said.

“Such an unfair playing field may exacerbate the current trend of global decoupling of supply chains and increase protectionism,” the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China said in a statement.

Continuing trade friction with the U.S. could hinder the rollout of the new Chinese plan, at least in the short term, as many of the Chinese companies involved still rely on the U.S. for critical components. That includes China’s dominant maker of 5G equipment, Huawei Technologies Co., which has been placed on a U.S. export blacklist.

Chinese leaders also have a track record of allowing political goals to skew industrial plans, leading to overspending in areas where there’s little demand, according to analysts.

“Demand for 5G in China isn’t quite there yet,” said Dan Wang, a technology analyst with research consultant GaveKal Dragonomics in Beijing. “For now, it remains a solution looking for a problem.”

Updated: 12-21-2020

What It’s Like Living Next To A Belt And Road Project

The real-life environmental and social impact of China’s infrastructure initiative shouldn’t be overlooked.

A lot has been written about China’s multibillion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative. Economists have debated the debt dynamics. Political scientists have analyzed how it fits into the rising power’s geopolitical strategy. And climate experts have decried the emissions China is adding to the atmosphere by supporting fossil fuel projects.

Rarely do we hear from the people whose lives are directly affected by the program. Earlier this year, a coalition of activist groups published Belt and Road Through My Village, a compilation of interviews with about 100 local residents who live close to BRI projects in five Asian countries.

It was a chance for them to express their concerns, and the list is long: disputes over land use rights, water and air pollution, deforestation, and loss of indigenous culture are just some of the issues they raised. The stories are a powerful reminder to governments and investors to consider the environmental and social impact of the BRI.

Muhammad Asif, 42, used to work at the Sahiwal coal-fired power plant, a BRI project built on 690 hectares of fertile land between Karachi and Lahore — Pakistan’s two biggest cities. The plant created more than 3,000 jobs and has been held up as an example of the good the BRI can do.

But Asif worries about the damage the plant is doing to the land and air. “All this development work has its cost,” he says in the book. Contaminated water from the plant is released into a nearby canal that’s used for crop irrigation and drunk by cattle.

“We fear that this contaminated water may sicken our cattle and make our lands barren or, at least, contaminate the produce. Air pollution is also becoming a problem as people have begun suffering from nasal, skin and lung diseases,” he says.

China insists that BRI projects are strictly vetted for environmental impacts and are meant to benefit the people who live in those areas, but in practice it has fallen short in introducing concrete steps to limit its financing of carbon-intensive practices. Local communities have also complained about a lack of transparency around the projects.

That’s slowly changing as environmental concerns become a greater investment risk. In Myanmar, the $3.6 billion Myitsone hydroelectric dam co-developed by China Power Investment Corp. has been stalled since 2011 following large protests over the lack of a proper environmental assessment.

he license for a $2 billion coal power plant in Lamu was canceled by a tribunal in Kenya because the public wasn’t consulted. A China-funded dam under construction on the Indonesia island of Sumatra is also facing fierce protests for posing a serious threat to endangered orangutans.

As countries step up their climate commitments under the Paris Agreement, more governments are expected to turn away from coal and other projects that damage the environment.

Pakistan, for example, said at the Climate Ambition Summit this month that it will stop building coal-fired plants. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which is the centerpiece of the BRI, has been long criticized for increasing Pakistan’s dependence on coal.

“If coal-fired power is now being de-prioritized within CPEC, then it could also happen right across the BRI program,” says Simon Nicholas, an analyst at Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

Even as awareness grows within China that it has to manage such risks, the government has so far only issued non-binding recommendations to improve green standards in its overseas investments.

The BRI International Green Development Coalition, which is supervised by China’s environmental ministry, this month proposed a color-coded classification mechanism as a way to better assess environmental risks assessments. The system would be based on three major factors: pollution prevention, climate change mitigation and biodiversity conservation.

Projects that would cause “significant and irreversible” damage would mandate stricter supervision from the government, harder financing conditions and more stringent financing status disclosure requirements.

That sounds like step in the right direction, but the proposal is merely a suggestion. More government departments and state banks would have to get on board for it to be implemented.

What’s missing are laws that require environmental and social assessments for every overseas project the BRI is considering investing in, according to Wang Xiaojun, founder of People of Asia for Climate Solutions, a Manila-based nongovernmental organization which co-published the book. Policymakers need to understand that local concerns are real and will increasingly become an important factor in determining the success of a project, he says.

One of the official goals of the BRI is to enhance people-to-people communication. That’s “the hardest but also the most urgent,” says Wang. “To hear the people, instead of excluding them from the dialog, should be the first step to reach this goal.”

Updated: 12-29-2020

Japan Group To Lend Vietnam $1.8 Billion For Coal-Fired Power

Tokyo bucks backlash from investors and its own environment minister, citing project’s contribution to economic development.

A Japanese-led group said it would extend nearly $1.8 billion in loans to build a coal-fired power plant in Vietnam, bucking criticism about the project’s impact on climate goals.

Plans call for a total of 1.2 gigawatts of electricity output at the plant in central Vietnam’s Vung Ang district. Investors include Tokyo-based trading company Mitsubishi Corp.

The government-owned Japan Bank for International Cooperation said Tuesday it would lend slightly more than a third of the total $1.767 billion in financing for the project. It said the project would “contribute to economic development in Vietnam through the stable supply of electricity.” Japanese commercial banks and the Export-Import Bank of Korea are also providing financing.

The project has become a flashpoint in the debate over whether rich nations should continue supporting coal-fired power in developing nations with growing electricity demand.

Critics of the project include a group of international investors and Japan’s own environment minister, Shinjiro Koizumi, who is considered a potential future prime minister. In January, Mr. Koizumi said the project couldn’t gain the understanding of the international community.

An October letter signed by Nordea Asset Management, a unit of the Nordic region’s biggest lender with more than $200 billion in assets under management, and other investors called on companies involved in the Vietnam project to pull out. It said the plant was incompatible with the Paris climate accord.

“To build a coal-fired power plant with that scale is just incomprehensible,” said Eric Pedersen, Nordea’s head of responsible investments, in response to Tuesday’s move by Japan. “This looks like the last spasms of old-fashioned industrial policy where you just keep doing what you’ve been doing.”

Mr. Pedersen said he didn’t believe the Vietnam plant would operate long enough to make back the money invested in it, given rising international pressure against coal.

Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga, a supporter of the Paris accord, said Dec. 14 that “all countries must take bold action” to tackle the threat of climate change. However, the government in July said it would continue to finance coal-fired power plants in countries where other options cost more or carry national-security risks.

Japan and Vietnam enjoy close ties and share concerns about China’s rise. Vietnam was the first country Mr. Suga visited after taking office in September.

Updated: 1-18-2021

China In Talks With Kenya For Debt Relief After Paris Club Deal

China is in talks with Kenya on a debt-service suspension deal, its embassy in Nairobi said, days after the Paris Club agreed to delay $300 million in payments by the East African nation.

China signed payment suspension agreements with 12 African countries and gave waivers on mature interest-free loans for 15 African nations under the G-20 framework, the embassy said in an emailed statement, without providing details. The China International Development Cooperation Agency and the Export-Import Bank of China implemented all eligible debt suspension requests from the nations, it said.

Kenya’s second-biggest external creditor after the World Bank said it “attaches great importance to debt suspension and alleviation in African countries including Kenya and is committed to fully implementing the G-20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative,” according to the statement.

Kenya applied for waivers under the DSSI framework for about 40.6 billion shillings ($368.7 million) due in the first half of this year.

Chinese loans comprised 21% of Kenya’s external debt, compared with the World Bank’s 25% at the end of June 2020, according to a National Treasury report. Sovereign bondholders held another 19%, commercial banks 11% and the African Development Bank 7.5%.

Updated: 3-25-2021

China’s New Belt And Road Has Less Concrete, More Blockchain

The Covid-19 pandemic hasn’t been good for China’s Belt and Road Initiative. The virus “seriously affected” one-fifth of the projects in the China-centered infrastructure drive, according to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Djibouti, Laos, Maldives, Pakistan, and Zambia, among others, have asked China to renegotiate or forgive Belt and Road loans. Kyrgyzstan and Sri Lanka have already extracted concessions.

But Belt and Road isn’t going away. China is making more rigorous lending decisions while focusing somewhat less on heavy-duty construction and more on digital technology, says a Council on Foreign Relations task force report released on March 23.

The 190-page report, titled China’s Belt and Road: Implications for the United States, was written by Jennifer Hillman and David Sacks of the CFR based on the findings of an independent task force chaired by former Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew and retired Admiral Gary Roughead.

For the U.S., calibrating an effective response to Belt and Road is tricky. The Obama administration pursued constructive engagement with China. As Belt and Road ramped up and became more of a threat, the Trump administration was more confrontational, but without allies’ support.

The Biden administration aims to build more of a united front of nations to counter Chinese influence. Reflecting the difficulty of striking the right balance, the Council on Foreign Relations report says the U.S. response “has been too little, too late,” but also says “its blanket condemnation risks alienating partners.”

Tensions between the U.S. and China were clear on March 19 when both sides aired grievances in an hourslong meeting at a hotel in Anchorage, Alaska. “We expected to have tough and direct talks on a wide range of issues, and that’s exactly what we had,” U.S. National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan told reporters afterward.

The U.S. has restricted sales of 5G wireless network gear from Huawei Technologies Co. and other Chinese suppliers and tried to get other countries to go along. But the Council on Foreign Relations report makes clear that the Digital Silk Road—the tech portion of Belt and Road—goes well beyond wireless networks.

It includes, among other things, Ant Group’s Alipay and Tencent’s WeChat Pay mobile payments apps. While Ant and Tencent are private companies, “they often use the BRI or Digital Silk Road label to gain domestic political support for their overseas commercial expansion and leverage the market access provided by BRI projects,” the report says.

China’s push in blockchain, if successful, could pose a serious threat to U.S. interests. Here’s a paragraph about that from the report:

Beijing is also focusing on blockchain ledgering. Chinese leaders believe that blockchain technology will be the foundational infrastructure for future technological innovation, and in 2020 Beijing launched the Blockchain Service Network (BSN). BSN is designed to leverage blockchain technology to offer software developers a cheaper alternative to current server storage space offerings.

A number of major blockchain projects have joined BSN, integrating their own chains with it, thereby enabling developers to create applications on the larger, less expensive BSN. Such integration also allows Beijing to bring this “international plumbing,” including the network infrastructure in Australia, Brazil, France, Japan, South Africa, and the United States, under its influence.

As China’s BSN white paper noted, “Once the BSN is deployed globally, it will become the only global infrastructure network autonomously innovated by Chinese entities and for which network access is Chinese-controlled.”

Belt and Road, says the report, “poses a significant challenge to U.S. economic, political, climate change, security, and global health interests.” It concludes that the U.S. shouldn’t attempt to “match China dollar for dollar or project for project.” Rather, it says, the U.S. should focus on areas where it can offer a “compelling alternative,” either on its own or with like-minded nations.

Among the specific recommendations: “reenergize the World Bank so that it can offer a better alternative to BRI,” and improve and then join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, which is the successor to the trade agreement that President Trump dropped out of as one of his first acts in office.

Updated: 4-12-2021

Djibouti Says Ethiopia Conflict Hinders Economic Rebound

The speed of Djibouti’s economic recovery from a contraction last year hinges on how soon conflict ends in neighboring Ethiopia, Finance Minister Ilyas Dawaleh said.

“The recent and escalating conflict in Ethiopia is worsening prospects for regional peace, trade and undermines regional cooperation,” Dawaleh said in an emailed response to questions on April 10. “As a result of these external and internal factors, Djibouti’s economic recovery is likely to be a prolonged affair.”

Situated at the entrance to the Suez Canal, Djibouti is a major trade conduit for Ethiopia, Africa’s second-most populous country. Fighting in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region that erupted in November has exacerbated the impact of the coronavirus pandemic and raised economic uncertainty in that country.

Djibouti’s economy shrank 1% last year, and is forecast to expand 5% this year and 5.5% in 2022, according to the International Monetary Fund. The country, is targeting growth of 7% to 9% in the coming years, driven by port upgrades, investments in green energy and technology, Dawaleh said.

The country has been ruled by President Ismail Omar Guelleh, 73, for the past two decades. He secured a fifth term in an April 9 election, winning more than 97% of the vote, according to the state-owned La Nation newspaper.

Situated on one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes, Djibouti has become increasingly important to regional and world powers. Smaller than the U.S. state of Massachusetts, it hosts the largest U.S. military base in Africa in addition to a Chinese People’s Liberation Army support facility.

In June, the Horn of Africa nation announced the creation of a sovereign wealth fund that will target domestic and regional investments, focusing on industries including telecommunications, energy and logistics. The fund is targeting $1.5 billion of contributions within a decade.

“The Djibouti Sovereign Fund will play an important role to attract and generate more international private capital,” Dawaleh said.

Updated: 4-14-2021

In Battle With U.S. For Global Sway, China Showers Money On Europe’s Neglected Areas

Goods are arriving in Europe through a new trade corridor consisting of railroads, airport hubs and ports built with Chinese support.

The struggle between the U.S. and China for global influence has come to Europe’s gritty industrial backwaters, where China is steadily co-opting local economies starting with their railroads.

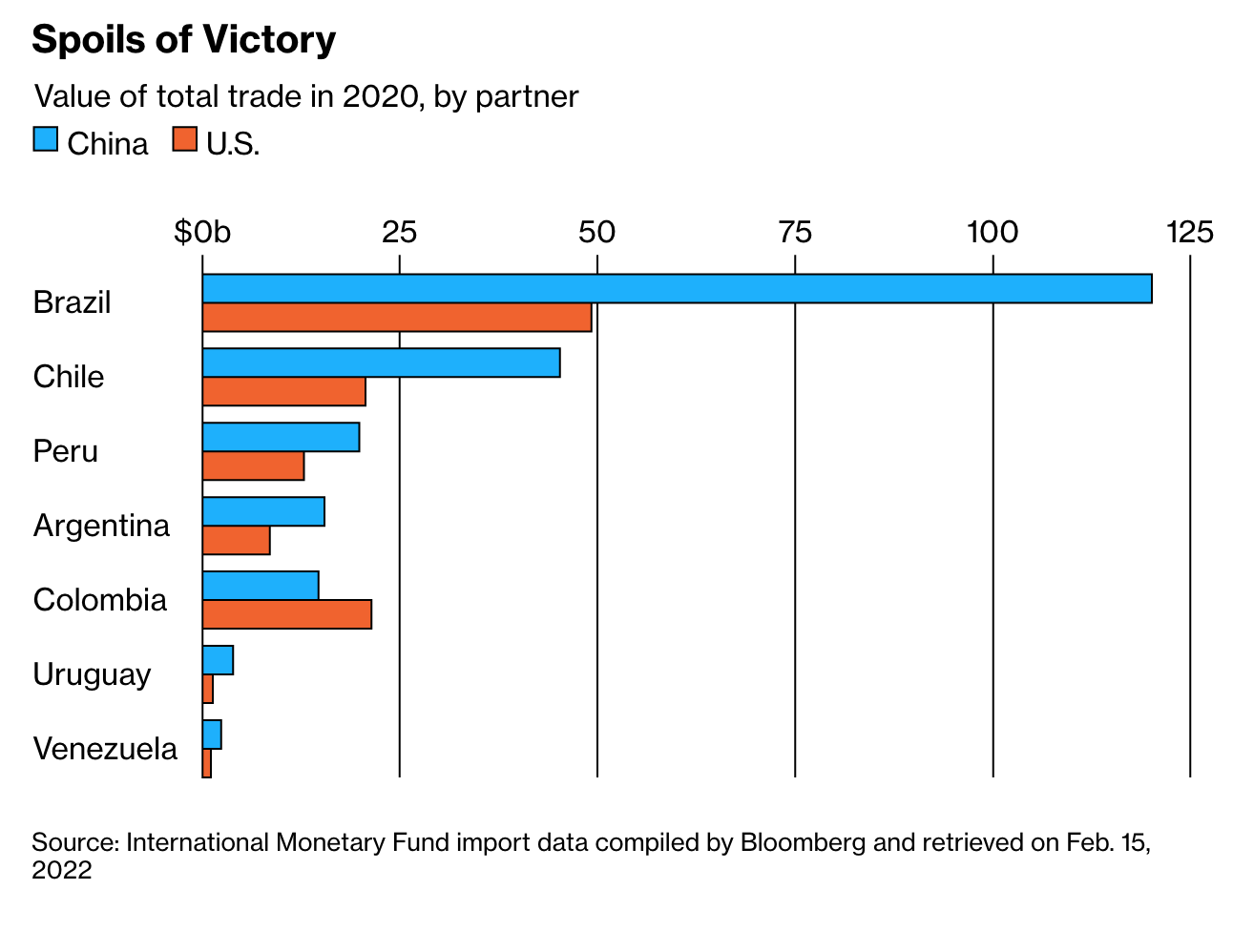

China overtook the U.S. as the European Union’s biggest trading partner for goods last year, a historic turning point driven in part by Europeans’ hunger for Chinese medical equipment and electronics during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Increasingly, those goods are arriving in Europe through a new trade corridor consisting of railroads, airport hubs and ports built with Chinese support, often as part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, the giant global infrastructure effort aimed at binding China more closely to the rest of the world.

By greasing the wheels of China-Europe trade, those investments have lifted long-neglected, rust-belt cities in places like Duisburg, Germany, and Liege, Belgium.

Western officials, including in the U.S., have accused China of using the Belt and Road to trap poor countries in debt. The Chinese government has denied those accusations.

While the pandemic has clouded the outlook for Belt and Road, Beijing isn’t likely to abandon it now that the Chinese economy is recovering.

In Europe, China has adapted its approach, sometimes operating below the radar with local authorities and companies.

China subsidizes the trains and tracks while big companies such as Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. provide direction and demand.

That might help Beijing tie rich countries even more closely to China. Europe’s trade links with China have already made it reluctant to accede to Washington’s attempts to turn it against the Asian giant.

The number of freight trains running between China and Europe topped 12,400 last year, 50% higher than in 2019 and seven times that of 2016, according to Chinese authorities. Demand for trains has been so high that freight companies have introduced a lottery system to allocate space, according to Chinese state media.

The World Bank estimates that Belt and Road transport infrastructure can boost trade by up to 10% for countries along the route.

Liege and Duisburg are both part of the Belt and Road initiative, although Germany and Belgium haven’t formally signed up to it, according to Chinese state media and local port officials.

“In gray, unglamorous areas like infrastructure and supply chains, there’s a lot less media and political attention, and more understanding that economic integration is necessary,” said Bruno Maçães, a former Portuguese minister who wrote a book on the Belt and Road project.

Europe’s political relationship with China has soured in recent months, notwithstanding a sweeping investment deal they loosely agreed to in December. While many European manufacturers rely heavily on Chinese appetite for autos, luxury products and other goods, they are increasingly alarmed to see China take market share in areas such as advanced manufacturing and engineering.

In infrastructure, however, Europe is much more welcoming of China’s presence and know-how, Mr. Maçães said.

Chinese shipping groups own terminals or share ownership in around a dozen European ports including Antwerp, Rotterdam, Valencia and Marseille.

U.S. officials have warned their European counterparts against excessive dependence on China. The U.S. launched a more limited global infrastructure project in 2019 alongside Japan and Australia.

In Duisburg, a west German steel town that handles more than a third of Europe-China rail freight traffic, trade with China rose 70% last year. A new rail terminal there part-built by China’s Cosco Shipping Holdings Co. will help expand China trade a further 40% to 100 trains a week, according to local officials.

“For Duisburg, it’s manna from heaven,” said Markus Taube, professor of East Asian economics at the University of Duisburg-Essen.

The rail line’s speed compared with the sea route offers a valuable alternative for producers of perishable or time-sensitive, high-value goods like electronics. Chinese internet giant JD.com Inc. is working with the port to export European industrial and consumer goods to China, according to the port’s chief executive, Erich Staake.

“We are currently transporting as much as possible—as much as our tracks allow,” said a spokesman for German rail company Deutsche Bahn AG, which operates trains between 17 European countries and China via Poland, Belarus and Kazakhstan. Some studies suggest that several hundred thousand trains a year could be plying the Europe-China rail route by the 2030s, he said.

The rail route was recently boosted further by the blockage of the Suez Canal.

Chinese investments support 23,000 jobs in the German state of North Rhine Westphalia, home to Duisburg and the Ruhr industrial heartland, while more than 1,000 local companies have invested in China, according to Andreas Pinkwart, the state’s economy minister.

In Liege, a Belgian city that has suffered the downturn in steel partly due to low-cost competitors in China, airfreight volumes are up 50% in the two years since Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba picked the city as its European hub, said Steven Verhasselt, who runs the airport’s commercial department.

“Every month in 2020 was a record and now in 2021 we are growing 20% year on year,” he said.

With support from Belgian officials, the airport has combined with a sleepy rail station to create a single customs zone. Six trains a week now travel between Liege and China, making it the first dedicated service for e-commerce between the Yangtze River Delta region of China, Central Asia and Europe.

That is all before Alibaba has even completed construction on the new hub. With other Chinese companies also looking at using it, Mr. Verhasselt expects freight volumes to double over the next four years to two million metric tons annually, potentially putting the airport on par with Paris Charles de Gaulle and Frankfurt International.

The airport’s expansion has created around 1,000 jobs over the past two years in a region with high unemployment.

Belgium’s postal service and other non-Chinese businesses have become heavy users of the new rail line. And aircraft and trains back to China are filling up with European goods, including milk powder, leather products, salmon and cheeses. Planes that used to return empty are now 80% full.

The rail link to China was one of the requirements that Alibaba had when selecting its European hub, said Mr. Verhasselt. “The Belt and Road is a success story in Liege because of Alibaba,” he said.

An Alibaba spokesperson said the company is investing 100 million euros, equivalent to $119 million, to build a logistics hub at Liege Airport that should be operational this year, as part of an agreement with the Belgian region of Wallonia.

The fast rail link has provided a critical edge for Chinese manufacturers competing in Europe, said Alexander Alban, managing partner at German mechanical parts manufacturer Walter Schimmel GmbH. Italian business executives say they are being squeezed out of Germany’s industrial supply chain by the Chinese, who can now transport heavy industrial goods quickly and cheaply into the heart of Europe.

Chinese exports to the EU jumped 63% in January and February year-over-year, while imports from Europe rose 33%.

However, tensions exist. U.S. officials recently cautioned German officials about China’s plans to expand its activities in Duisburg, according to a person familiar with the matter. In Portugal, where Chinese companies are considering building a container port terminal, the U.S. ambassador warned recently that Portugal must choose between America and China.

Chinese investment in Piraeus, near Athens, has helped transform Greece’s primary port over the past decade from an economic backwater into Europe’s fourth-busiest.

Cosco, which controls the port, has proposed building a fourth container terminal that could allow trade volumes to double again, potentially putting Piraeus on a par with giant European ports such as Hamburg.

Ten trains a week ply a new rail route that connects Piraeus’s port with Eastern European markets including the Czech Republic, transporting around 100,000 containers a year, said Nektarios Demenopoulos, a spokesman for the Piraeus Port Authority.

Greece hasn’t yet approved Cosco’s expansion plans. Greek officials have complained the Chinese company has received most of the benefits. But after Cosco said last month that it would build a children’s playground for local residents, the mayor of Piraeus, Ioannis Moralis, expressed confidence the port would soon be better integrated with the city.

Updated: 6-1-2021

G-7 Set To Back Green Rival To China’s Belt And Road Program

The Group of Seven nations plans to launch a green alternative to China’s Belt and Road initiative when the leaders meet at a summit next week, according to two people familiar with the matter.

The strategy, expected to be called the “Clean Green Initiative,” would provide a framework to support sustainable development and the green transition in developing countries, the people said. The initiative will also be on the summit agenda for the leaders.

A G-7-backed plan to rival China’s infrastructure strategy was initially pushed by U.S. president Joe Biden, and has featured in technical discussions between diplomats preparing next week’s meeting in Cornwall, England, one of the people said.

The same person said that it was not clear whether any new money would be put behind the G-7 initiative, explaining that the initial purpose was a pledge toward creating a strategic framework.

The U.K. Cabinet Office didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

Beijing’s trillion-dollar initiative has seen over 100 countries endorse the program, and its network of projects and maritime lanes already snake around large parts of the world.

But critics argue that the projects often create a debt dependency and expose nations to undue influence by Beijing. Montenegro, a NATO member and European Union aspirant, is one of the latest countries struggling to repay loans to China.

In the lead up to next week’s summit, G-7 members have expressed different views on the geographical focus the initiative should have, said one of the people familiar with the discussions.

Germany, France and Italy are keen for it to support activities in Africa, while the U.S. is pushing for action in Latin America and Asia. Japan argues for more focus on the Indo-Pacific region. But all nations broadly agree on the need for a more transparent alternative to the Chinese program, the person added.

In recent years, several G-7 countries, as well as the EU, have launched their own infrastructure initiatives with mixed results. More are in the works.

The G-7 leaders’ summit takes place June 11-13.

Updated: 7-18-2021

China Buys Friends With Ports And Roads. Now The U.S. Is Trying To Compete

Rare bipartisan program dedicates $60 billion for overseas infrastructure projects including cellular networks, vaccine production and maybe even a crumbling Greek shipyard.

An aging shipyard here has a new suitor sizing it up for investment: the U.S. government.

To counter China’s rising global economic influence, Washington has taken a new direction with foreign assistance. Rather than just lend money or promote trade, as in recent decades, the U.S. is now investing dollars overseas to advance American national-security interests. It wants ports, cellular networks and other strategic assets to stay in friendly hands.

At the forefront of this effort is an agency Congress overhauled in 2019, the International Development Finance Corp., or DFC.

“It’s a very significant investment tool that we have to compete” against China, said Rep. Michael McCaul, the top Republican on the House Foreign Affairs Committee.

The Trump administration was quick to use the DFC, discussing purchasing the shipyard with Greek officials and offering loans to get Ethiopia to shun 5G cellular equipment from China’s Huawei Technologies Co.

The Biden administration wants to go further, to offset Beijing’s vaccine diplomacy and other efforts. The Group of Seven wealthy democracies last month announced a new initiative, called Build Back Better World, that they promised would unleash hundreds of billions of dollars for projects in needier countries. It was designed as an explicit alternative to Chinese infrastructure offerings.

U.S. officials say the DFC is the initiative’s most powerful tool. Its $60 billion investment cap exceeds the combined resources of its counterparts in the other six nations.

“We’re going to invest more this year than any time in the agency’s history, which reflects the president’s vision,” Chief Operating Officer David Marchick said.

U.S. leaders say the DFC offers financing with fewer strings attached compared with Beijing, whose loans can come with high interest rates, hard collateral such as ports and requirements to use Chinese suppliers.

The DFC aims to spur private-sector investment, and not just for American companies.

The goal of the DFC and its G-7 counterparts is “to offer a better product than the opaque, extractive and coercive terms” of Chinese-backed projects, said deputy national security adviser Daleep Singh, the White House official working closely with the DFC.

China’s new aggressiveness on the world stage has refocused Washington’s foreign-assistance game. The DFC resulted from a bipartisan effort rare today, broadly supported in Congress and by both the Trump and Biden administrations.

Foreign assistance in developing countries is inherently risky, and the DFC could yet back out of the Greek and Ethiopian projects after each hit hurdles.

Congress is still debating which countries should qualify for funding. The DFC was briefly pulled into a messy effort last summer to fund Covid-19 pharmaceutical-chemical production at Eastman Kodak Co., but has otherwise focused overseas.

The DFC is the latest incarnation of postwar American foreign assistance, which included the Marshall Plan that helped rebuild Europe and the U.S. Agency for International Development, which provides economic and disaster assistance to developing countries. Washington launched the programs to strengthen ties with allies, halt communism’s spread and open markets for U.S. companies.

After the Soviet Union collapsed, the aid mission broadened, with initiatives such as the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief launched in 2003 by President George W. Bush to improve healthcare in sub-Saharan Africa. Some congressional critics say U.S. aid lost focus.

It sharpened again with China’s Belt and Road initiative. First pitched in 2013 as an effort to build a modern version of ancient Silk Road trading routes, the initiative includes a global network of ports, railways and other projects largely built by Chinese companies and using at least $400 billion in funding from government-run banks.

Sen. Chris Coons (D., Del.) saw Beijing’s soft power win friends. As a member of a foreign-relations subcommittee focused on Africa, he visited a Benin hospital where the U.S. funded medicine and training.

“But if you were the Beninois walking into the hospital, you wouldn’t know that,” Mr. Coons said. A sign in Chinese outside made it clear that a Chinese company had refurbished the hospital.

Such experiences, and word from African leaders about Chinese infrastructure pitches, persuaded him to champion legislation offering a U.S. alternative to Belt and Road. It won bipartisan support.

Democrats wanted to strengthen U.S. foreign-assistance programs. Republicans in Congress and the Trump administration saw a chance to take on Beijing.

Congress passed the BUILD Act, led by Sens. Coons and Bob Corker (R., Tenn.), in 2018. The law transformed an existing assistance agency, the Overseas Private Investment Corp., into the DFC.

The new agency opened doors in December 2019, chaired by the secretary of state. The DFC’s investment cap—essentially a credit-card limit—rose to $60 billion, double that of the old agency.

And it isn’t required to back projects involving only American companies. That made it easier to target telecommunications projects, considered vital. The U.S. lacks a major international player in the industry.

The DFC receives an annual federal appropriation for administrative and other expenses. The investment fund of the DFC and its predecessor has never turned a fiscal-year loss, but it has no legal requirement to make a profit.

Its mandate is to balance returning money to U.S. taxpayers with foreign-policy and national-security goals, which include countering authoritarian governments and promoting economic growth in developing countries.

Early Trials

One of the DFC’s first initiatives, announced in late 2019, was agreeing to lend up to $190 million to a Nevada-based company to create the world’s longest subsea fiber-optic cable, between the U.S., Singapore, Indonesia and Palau, offering an alternative to Huawei-built undersea networks.

Adam Boehler, a Trump administration appointee who served as the DFC’s first chief executive, said it was easy for him to reach leaders of any developing country.

“Countries are more excited to meet the head of DFC than the secretary of state,” said Mr. Boehler, who stepped down in January amid the administration transition. “It’s hard money.”

The DFC’s potential quickly emerged in Greece, which was too wealthy to qualify initially for DFC assistance. Chinese shipping giant Cosco in 2016 bought a 51% stake in the Piraeus port outside Athens for the equivalent of more than $310 million, an investment that Chinese President Xi Jinping dubbed the “dragon’s head” of the Belt and Road initiative in Europe.

Greek satisfaction with the deal soon waned, after China started exerting political pressure to support it in international disputes. Athens residents saw little economic gain from Cosco’s spending inside the vast port facility.

U.S. Ambassador to Greece Geoffrey Pyatt saw a role for the DFC in the country, particularly in the Elefsina shipyard a short drive from Piraeus. Greek officials said Chinese buyers might try to snap up the shipyard, but prefer an American investor.

“It’s important for us that the U.S. presence in this area would be a significant one,” said Adonis Georgiadis, Greece’s minister of development and investments, in an interview. He said the government must help Greek shipyards and that “we cannot give everything to China.”

Just as the DFC was opening shop in late 2019, Amb. Pyatt successfully lobbied Congress to add Greece to its remit. He connected Mr. Boehler, Greek officials and Onex SA, a Greek-American industrial group that wanted to buy Elefsina.

Onex Chief Executive Panos Xenokostas said he wants American assistance because Beijing’s subsidies make Chinese companies tough competitors. “The funding for Chinese companies in the shipyard business is massive,” he said in an interview.

Onex last year struck a provisional agreement with the shipyard’s private shareholders, brokered by the government, to buy and modernize the facility. It pledged more than $300 million over 10 years to cover investments and debts.

The deal is being reviewed by a Greek court, which could rule on it this fall.

The DFC discussed a long-term loan worth roughly tens of millions of dollars, said former DFC official Caleb McCarry. Current DFC officials say the project remains uncertain because of concerns about its financial feasibility.

Representatives for China’s foreign ministry didn’t respond to a request for comment for this article. Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Le Yucheng said earlier this month that the new U.S. push to finance infrastructure projects only proves that China’s Belt and Road initiative “is the right path and the path of the future.”

Another deal that Mr. Boehler, a healthcare entrepreneur and former Department of Health and Human Services leader, struck was with Ethiopia. The East African country is important for U.S. efforts against terrorist groups linked to al Qaeda and Islamic State.

Visiting in 2019, Mr. Boehler asked Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, who had just won the Nobel Peace Prize, about infrastructure opportunities.

Ethiopia was opening its telecom market, long controlled by a government monopoly with unreliable service, to private wireless carriers.

The country had been using telecom equipment from China’s Huawei and ZTE Corp. From 2006 to 2013, the two lent $3.1 billion to Ethiopia for telecom projects, according to the China Africa Research Initiative and Boston University Global Development Policy Center. The U.S. considers Huawei and ZTE spying threats, an allegation the companies deny.

Mr. Boehler learned that a U.K. foreign-aid agency was in talks to finance an Ethiopian bid led by London-based wireless giant Vodafone Group PLC. He asked his British counterpart and Vodafone if the DFC could pitch in.

Mr. Boehler said Vodafone was considering using Chinese equipment because it costs less than U.S.-approved alternatives from Sweden’s Ericsson AB, Finland’s Nokia Corp. and South Korea’s Samsung Electronics Co.

“We’d love to do this, but can you rip out the Huawei equipment?” Mr. Boehler said. Non-Chinese equipment would cost about $400 million more, he said. The DFC agreed to subsidize that by lending up to $500 million at an interest rate below commercial terms.

Vodafone faced only one other bidder for an Ethiopian wireless license: South Africa’s MTN Group, a longtime Huawei and ZTE user whose proposal was backed in part by the Chinese government-owned Silk Road Fund, which was designed to help finance Belt and Road projects.

In May, Ethiopia announced only one winner: the U.S.-backed consortium.

The deal might not shut the door on Chinese gear. Vodafone, which isn’t obligated to follow through on the loan, said it is still finalizing which equipment suppliers to use.

And it is unclear whether the U.S. wants to go through with the loan either. Secretary of State Antony Blinken has criticized Ethiopia’s government for not allowing humanitarian access to the country’s Tigray region, where he said there were credible reports of human-rights abuses amid a violent conflict.

A DFC spokeswoman said it and other U.S. agencies were monitoring the situation in Tigray “and will carefully consider its impact on any potential financing of the Vodafone consortium.”

An Ethiopian government spokeswoman said humanitarian groups have had access to the region for months, and that the government is focused on improving people’s lives through initiatives like the telecom project.

Sen. Coons isn’t surprised the DFC has faced challenges. “Doing development and infrastructure investment in the developing world is inherently risky—that’s the point,” he said.

New Administration

The Biden administration considers the DFC one of its most powerful foreign-assistance tools because of its large investment cap and flexibility to offer loans, equity financing, grants and insurance, said Mr. Singh, the deputy national security adviser.

He said the White House is focusing the DFC on four areas: health, technology, climate change and gender equality.

In March, after President Biden met with the leaders of Australia, India and Japan as part of an alliance known as the Quad, the White House asked the DFC to collaborate with the allies on a health initiative.

The DFC asked the U.S. Embassy in India, one of the world’s biggest vaccine-making countries, to identify pharmaceutical companies it could join with.

That’s how Mahima Datla ended up on a call with Mr. Marchick and other DFC officials. “They said, ‘If you had access to capital, how many more vaccines could you make?’ ” recalled Ms. Datla, managing director of vaccine-manufacturer Biological E Ltd.

Biological E had already agreed to produce at least 600 million doses of Johnson & Johnson’s one-shot Covid-19 vaccine, at a pace of 50 million a month.

She said a DFC loan would enable her to add a third assembly line to her Hyderabad facility and produce 100 million doses a month.

Ms. Datla and DFC officials agreed to a provisional deal in less than a month and hope to complete it soon. The agreement calls for Biological E to produce at least one billion vaccine doses by the end of 2022.

DFC officials say that while advancing healthcare in the developing world is the main motivation behind the potential investment, providing an alternative to Beijing’s vaccine diplomacy is also a factor.

Updated: 7-22-2021

How Biden Can Take On China With A Better Belt And Road

The G-7 initiative to counter Beijing’s infrastructure diplomacy can’t end up as a bridge to nowhere. Here’s what it should look like.

There’s good reason to be skeptical about U.S. President Joe Biden’s plan for an alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, the infrastructure-building bonanza that Beijing uses to expand its global clout.

Sure, the Group of Seven nations committed to the idea last month, calling it “Build Back Better World,” or B3W. But that’s no more than a start. Success will require a focused program outlining what to build, how to pay for it, and how to convince needy nations to sign up.

Unfortunately, such details are in short supply. Fiscally stretched by Covid-19 outlays, the advanced economies can barely afford needed infrastructure at home, let alone splurge on roads, bridges and telecom networks in the far corners of the earth.

Even the Chinese have been scaling back lending to developing countries in recent years, possibly a result of deleveraging pressure at home and too many troubled loans abroad. It’s tempting for the West to hope that Belt and Road runs out of highway entirely on its own.

But betting on China to fail isn’t a strategy. The Western powers need to realize they are entering a prolonged period of competition with China, and that requires a renewed commitment to global action. B3W could be an important part of a revitalized agenda.

Not only is it a smart way to contend with rising Chinese power — without direct confrontation — but could also help the creaking U.S.-led global economic system prove to the world that it can provide prosperity well into the future.

China has left the door wide open for a Western resurgence. The poorly planned Belt and Road isn’t the high-minded model of sustainable development Beijing says it is, but a boondoggle for Chinese business. In some cases, poor countries have paid the price.

The program has suffered from too many ill-conceived projects — from a railway in Ethiopia to a highway in Montenegro – that have left governments unable to pay back their Chinese loans. Research outfit Rhodium Group figured that as much as a quarter of the money China has lent overseas has had to be renegotiated.

That offers opportunity for Biden and his friends to promote B3W as a source of financially sound, high-quality and well-organized infrastructure.

They can capitalize on the long experience that their development institutions and programs, such as the World Bank, have had vetting, planning and financing infrastructure.

The rich donor countries have also designed wise guidelines for lending to governments of low-income nations (albeit after much painful trial and error) to help prevent them from amassing unsustainable debt.

This isn’t to say that the Western institutions are infallible; far from it. But they have at least learned from previous, often tumultuous, experience with debt crises and other controversies.

Of course, a better-designed project also comes with stricter conditions and controls, and that’s often been seen as a disadvantage versus Chinese-backed efforts, which, though not exactly “strings-free” as widely perceived, don’t get overly hung up on labor rights, debt dynamics and other pleasantries.

But the West’s more stringent methods may actually be a selling point.

A recently released survey of nearly 7,000 leading figures in the developing world by research lab AidData revealed that the respondents preferred programs with greater transparency on financing, stronger environmental and labor protections, and tougher measures to combat graft.

To appeal to such sentiments, B3W should be promoted to a wide swath of society in borrower nations – NGOs, legislators, and the taxpaying public at large – to woo support and increase political pressure on governments to make better choices.

This suggests that B3W’s success will depend as much on marketing as money. The fact is that the Western world is far from stingy.

According to data compiled by the Global Development Policy Center, China’s two main state-owned policy banks – the Export-Import Bank of China and China Development Bank – extended $462 billion in financing to foreign governments and state-owned entities between 2008 and 2019. A huge sum indeed – but still $5 billion less than the World Bank lent over that same time period.

More resources would be helpful. The White House intends to mobilize private capital to minimize B3W’s burden on strained fiscal budgets – a good idea. But existing development spending can also be reoriented toward more physical infrastructure.

An analysis by the Council on Foreign Relations makes the intelligent point that the Western powers don’t need to match Chinese largesse, but should target resources where they have an edge, such as technology.

Biden can also make the program more attractive by making it more inclusive. Though China’s project managers do share the pie with locals, Belt and Road doesn’t live up to Beijing’s broad claims of international cooperation. Chinese companies overwhelmingly benefit, shoving other firms to the shoulder.

B3W can distinguish itself by being as open as possible to companies and workers, international and local. This would help build support in the borrowing countries, and likely bring greater expertise and top technology to the projects.

Such inclusiveness is key to this superpower contest. Beijing uses Belt and Road as a tool to tie developing countries to its economy by reorienting trade toward China and entrenching its own technologies in foreign markets.

China also hopes the money can purchase political influence – and there are some indications it has. In a recent interview, Imran Khan, prime minister of Pakistan, a major Belt and Road recipient, acknowledged that he is silent on the treatment of minority Uighurs in part because China is an important economic partner.

B3W could reaffirm economic bonds between the advanced democracies and the developing world, and keep these markets open to Western business. But most of all, it would be proof that the U.S. and its allies can continue to lead in positive ways.

Rather than just criticizing China and its initiatives – Belt and Road has been derided as a “debt trap” – Washington is more appealing when proposing real alternatives reflecting its ideals.

The global contest with China is about more than who can build ports or power grids. It’s about which system can offer what the world needs – one based on agreed international norms and free enterprise, or one rooted in state capitalism and illiberal practices.

Allowing Belt and Road to go uncontested suggests that the U.S.-led global economy can no longer provide prosperity and progress. And that’s truly a bridge to nowhere.

Updated: 9-30-2021

Chinese Loans Leave Developing Countries With $385 Billion In Hidden Debts, Study Says

Key Points:

* AidData, an international development research lab based at Virginia’s College of William & Mary, analyzed 13,427 Chinese development projects worth a combined $843 billion across 165 countries, over an 18-year period to the end of 2017.

* Researchers found that these nations’ debt obligations to China are larger than international research institutions, credit ratings agencies or intergovernmental organizations estimate.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative has caused dozens of lower- and middle-income countries to accumulate $385 billion in “hidden debts” to Beijing, a new study has claimed.

AidData, an international development research lab based at Virginia’s College of William & Mary, analyzed 13,427 Chinese development projects worth a combined $843 billion across 165 countries, over an 18-year period to the end of 2017.

China has provided record amounts of financing to developing countries over the past two decades, supporting both public and private sector projects.

The Belt and Road Initiative is President Xi Jinping’s flagship foreign policy initiative; launched in 2013 to invest in almost 70 countries and international organizations, it has propelled China to global dominance in international development finance.

The U.S. is planning to develop a similar scheme in South America, and the EU announced in September that it is launching a worldwide “Global Gateway” program, as both regions look to challenge China’s massive financial and geopolitical influence in the developing world.

China currently spends at least twice as much on international development finance as the U.S. and other major economic powers, according to the AidData report — around $85 billion a year.

However, this is often in the form of debt rather than aid, and this imbalance has accelerated in recent years. Since the introduction of the Belt and Road, China has issued 31 loans for every 1 grant, the report found.

The deals’ financing arrangements remain somewhat opaque, with a lack of detailed information causing investor reticence in recent years in some lower- and middle-income countries, such as Zambia.

China has long denied pushing developing nations into so-called debt traps, which could pave the way for Beijing to seize assets as collateral for unpaid debt obligations.

However, concerns have been aired since the Belt and Road’s (BRI) inception about the possibility that lending could be higher than officially reported in many lower- and middle-income countries. AidData collectively estimates that underreported debts are worth around $385 billion.

CNBC has contacted the Chinese embassies in London and Washington for comment on AidData’s report.

“During the pre-BRI era, the majority of China’s overseas lending was directed to sovereign borrowers (i.e., central government institutions),” the researchers said.

“However, a major transition has since taken place: nearly 70% of China’s overseas lending is now directed to state-owned companies, state-owned banks, special purpose vehicles, joint ventures, and private sector institutions.”

These debts often do not show up on countries’ government balance sheets, but many are guaranteed by their governments, blurring the lines between private and public debt and creating fiscal challenges for countries.

These guarantees can be explicit, or implicit — in that public or political pressure could force the government to bail out a company in financial distress.

Researchers found that these nations’ debt obligations to China are significantly larger than international research institutions, credit ratings agencies or intergovernmental organizations estimate.

The report claims that 42 countries now have public debt exposure to China that exceeds 10% of their GDP.

“These debts are systematically underreported to the World Bank’s Debtor Reporting System (DRS) because, in many cases, central government institutions in LMICs [lower- and middle-income countries] are not the primary borrowers responsible for repayment,” the report said.

“We estimate that the average government is underreporting its actual and potential repayment obligations to China by an amount that is equivalent to 5.8% of its GDP.”

This would collectively amount to approximately $385 billion, and AidData suggested that managing these hidden debts has become a “major challenge” for many affected countries.

“The ‘hidden debt’ problem is less about governments knowing that they will need to service undisclosed debts (with known monetary values) to China than it is about governments not knowing the monetary value of debts to China that they may or may not have to service in the future,” researchers added.

Updated: 11-15-2021

Updated: 12-1-2021

Laos Will Open $5.9 Billion Railway As Debt To China Mounts

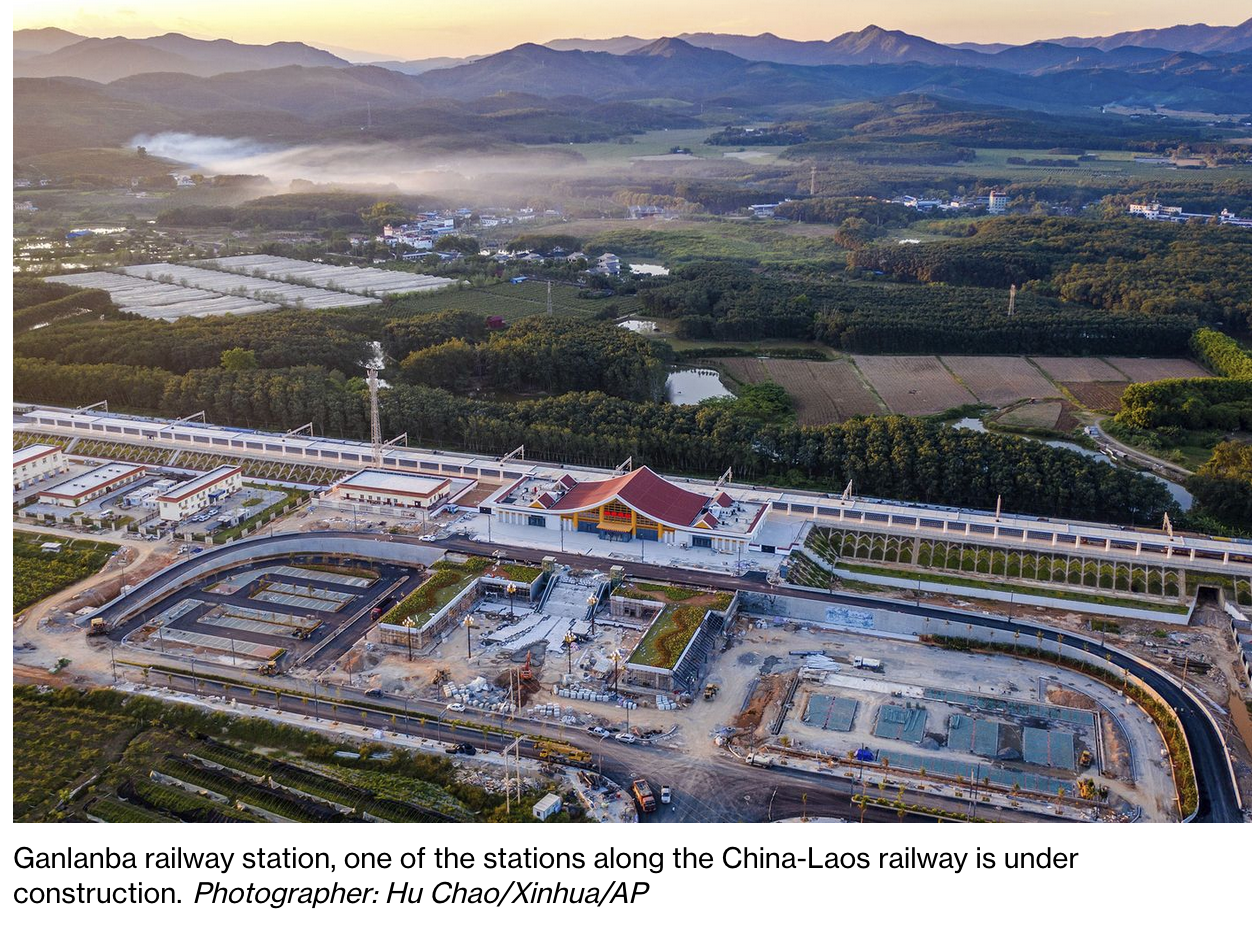

Laos, a nation of 7 million people wedged between China, Vietnam and Thailand, is opening a $5.9 billion Chinese-built railway that links China’s poor southwest to foreign markets but piles on potentially risky debt.

The line through lush tropical mountains from the Laotian capital, Vientiane, to Kunming is one of hundreds of projects under Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative to expand trade by building ports, railways and other facilities across Asia, Africa and the Pacific.

The 1,035-kilometer (642-mile) line opens this week to cargo but no regular passengers due to anti-pandemic travel curbs.

Poor countries welcome China’s initiative. But the projects are financed by loans from Chinese state-owned banks that must be repaid. Some borrowers complain Chinese-built projects are too expensive and leave too much debt.

The Kunming-Vientiane railway is a link in a possible future network to connect China with Thailand, Vietnam, Myanmar, Malaysia and Singapore. That would give southern China more access to ports and export markets.

Laotian leaders hope the railway will energize their isolated economy by linking it to China and markets as far away as Europe.

But foreign experts say the potential benefits to Laos beyond serving as a channel for Chinese trade are unclear and the cost appears dangerously high.

The railway will “generate very positive economic returns” for China and possibly other countries, but it is harder to see “exactly what the economic benefits are going to be” for Laos, said Scott Morris of the Center for Global Development in Washington.

With only 21 stations in Laos, the line is designed to serve Chinese needs to reach foreign ports quickly, Morris said. He said a railway to serve mostly rural Laos would have more stations to connect farmers to markets.

“This is essentially a Chinese public infrastructure project that happens to exist in another country,” he said.

Chinese contractors are building a high-speed rail line from the Thai capital, Bangkok, to northeastern town of Nong Khai on the Lao border. That won’t be completed until 2028 and leaves a gap to be filled between the border and the line to China.

The Kunming-Vientiane railway’s 418-kilometer (260-mile) segment in Laos will be operated by the Laos-China Railway Co., a joint venture between China Railway group and two other Chinese government-owned companies with a 70% stake and a Laotian state company with 30%.

Borrowed money makes up 60% of the railway’s investment, according to the two governments.

Such a debt load is unusually heavy and “repayment risk should be quite high,” said Laura Li of S&P Global Ratings, a specialist in infrastructure financing.

Laos might be forced to take over repaying the joint venture’s full $3.5 billion debt to keep the line running if the company defaults and the Chinese partners choose not to put in more money, said Ammar A. Malik and Bradley Parks in a report for AidData, a research project at Virginia’s College of William & Mary.

That is the equivalent of nearly a fifth of Laos’s economic output last year.

The country’s outstanding debt, much of it owed to Beijing, is equal to about two-thirds of annual economic output. Laos ranks among poor countries deemed to be at “high debt risk.”

Railways can raise incomes by linking rural areas with cities and export markets. But that payoff can take decades, while railways require big spending on equipment, land and construction.

Operators that start with high debt need revenue fast to pay lenders.

“Laos has put itself in a position where if the railway doesn’t make a profit, then it’s got real debt issues,” said Greg Raymond, a Southeast Asian expert at Australian National University.

Laos has been one of the world’s fastest-growing economies over the past decade but still is one of its poorest. Its average economic output person more than doubled since 2010 but stands at $2,600.

The railway has the potential to raise incomes by 21% in the long run if other reforms also are carried out to make trade and doing business easier, the World Bank said in a report last year.

The railway “will convert Laos from being geographically disadvantaged, by taking advantage of its location, to a regional land-linked hub,” said the vice president of the Lao National Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Valy Vetsaphong, according to the Lao news agency.

People who were displaced from their homes to make way for the railway complain they were paid too little.

Environmentalists say construction damaged natural habitats and threatens endangered species in Laos, which already is a center for wildlife trafficking.

“Any new transport facilitator between the country and major markets for wildlife, such as China, is going to threaten wildlife,” said Steven Galster, executive director of the Freeland Foundation, which investigates and combats wildlife trafficking.

Laos represents a new market for China’s railway technology. China’s state press describes the Kunming-Vientiane line as high-speed, but its 160 kph (100 mph) speed is about half that of China’s bullet trains.

China’s bullet train network is the world’s biggest. The system is based on technology licensed from French, German and Japanese manufacturers, but China is developing its own trains and marketing them globally.

Railways built with BRI financing, including in Kenya and Ethiopia, have struggled to repay Chinese loans. Beijing has started offering lower-cost loans and forgiving some following complaints about debt loads for poor countries.

In 2019, Beijing forgave debts owed by Ethiopia and Cameroon. The same year, Malaysia canceled a $20 billion rail line due to be built by Chinese contractors after failing to renegotiate the price.

Laos also is turning to its giant neighbor to help develop other industries, including delivering power from hydroelectric dams to neighboring countries, one of the country’s biggest exports.

Under an agreement signed in March, the national power distribution grid and export system will be run by a joint venture between the Laos utility and state-owned China Southern Power Grid Ltd.

Updated: 12-2-2021

Uganda Can Meet China Loan Terms, Keep Airport, Legal Head Says

* Reworking Debt Agreement Clauses Unnecessary, Kiwanuka Says

* Repayment Of The 20-Year Loan Due To Start April 1, 2022

Uganda’s chief legal officer urged the Finance Ministry to refrain from renegotiating the terms of a $200 million Chinese loan as it is able to meet its debt obligations.

The agreement signed in 2015 with the Export-Import Bank of China to fund the expansion of the Entebbe Airport came with several contentious clauses, including one that could see the lender take ownership of the facility in the event of a default.

It’s unnecessary to rework the clauses as the nation is capable of meeting its obligations, Attorney General Kiryowa Kiwanuka was cited as saying in a statement on the Parliament of Uganda’s website.

“Contracts in our view are bad when you put out obligations which are impossible of performance,” Kiwanuka said. “The obligation in this contract is all capable of performance.”

Fears of the airport being taken over by the Chinese are unfounded as Uganda has not yet started repaying the 20-year loan, which came with a seven-year grace period that expires in April next year, he added.

Updated: 12-27-2021

Uganda Finds China’s Leverage Is In The Fine Print of Its Lending

A clause in an agreement with the African nation has stirred a flap over whether the country signed away financial control of Entebbe International Airport

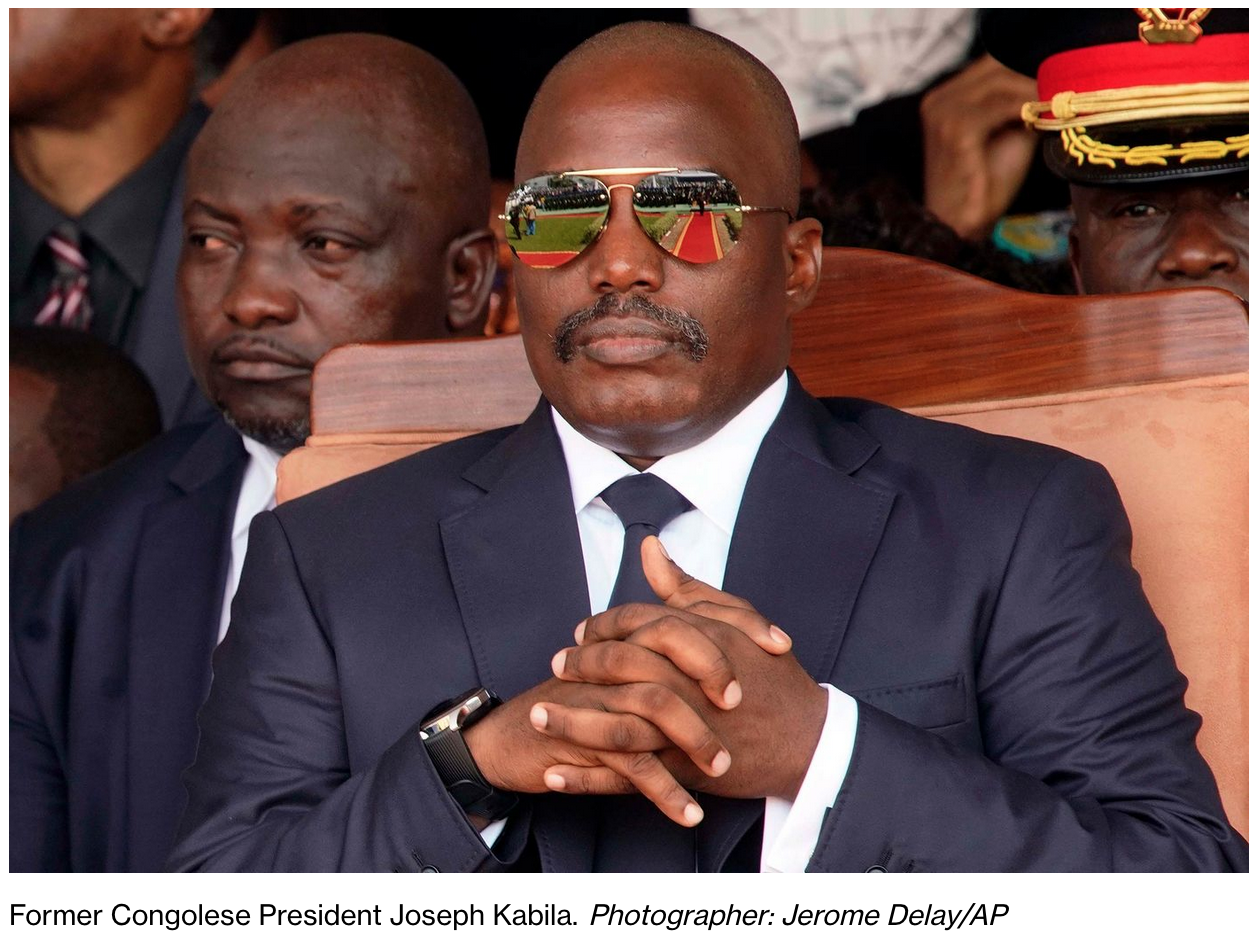

Chinese lending stemming from President Xi Jinping’s signature Belt and Road Initiative transformed economies across the developing world.

Now, as bills are coming due in Uganda and elsewhere, attention is turning to how aggressively Beijing is enforcing contractual obligations even as it sometimes extends repayment periods.