Citizen Surveillance Is Playing A Major Role In Criminal Investigations

As surveillance technology has spread from security cameras to smartphones in every pocket, it has sparked privacy concerns. Citizen Surveillance Is Playing A Major Role In Terrorist And Other Criminal Investigations

Armed with drones, cell phone interception technology, battery and/or solar-powered hidden cameras citizens set-out to assist law enforcement solve some of the world’s most difficult cases.

Related:

Who’s Watching Who? gSpy vs. iSpy

At the same time, the technology has proved helpful to criminal investigations–including the one focused on the Boston Marathon explosions.

On Wednesday, a government official said the Federal Bureau of Investigation used surveillance video from a Lord and Taylor department store and restaurants near the bomb site, as well as photographs from average citizens, news organizations and others to help identify a suspicious person at the marathon.

The use of such technology in the Boston investigations highlights how, since the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, the adoption of surveillance technology and the amount of data gathered has grown considerably. Still, video and photo facial-recognition technologies remain in their infancy.

From 2011 to 2016, the global market for video-surveillance technology is expected to nearly double to $20.5 billion, according to IHS IMS Research. According to Forrester Research, 68% of public-sector and 59% of private-sector companies have adopted video-surveillance technologies–and 9% plan to adopt it in the next two years. Moreover, more than a billion people now carry a basic tool of surveillance in their pockets: camera-equipped smartphones that connect to the Internet.

Combining forensic image data from professional and personal sources has worked in previous cases. After the 2011 riots in Vancouver, British Columbia, authorities used nearly 1 million digital images and 1,600 hours of video gathered from the public and closed-circuit cameras to identify criminal acts and eventually bring charges against more than 200 people.

Challenges remain to making use of all the new data. Facial recognition is often difficult to use in large-scale investigations because surveillance footage rarely has full-frontal images, which are needed for computers to identify enough key points on a face.

“It’s not the way it is in the movies,” said Aki Peritz, a former counterterrorism analyst at the Central Intelligence Agency, now senior policy adviser for national security at Third Way, a Washington think tank. “In real life you don’t have someone looking directly into the camera, and the ability to make a match can be very much degraded if you don’t have a full frontal.”

Then there is the challenge of collecting and sorting through the data. Boston has one of 77 nationwide intelligence “fusion centers” that is involved in helping investigators in this week’s bombings to pool data and conduct analysis, said Mike Sena, director of the Northern California Regional Intelligence Center. The state-run centers were funded by the Department of Homeland Security after the Sept. 11 attacks to address the lack of interagency information sharing.

The centers allow authorities to tap thousands of law-enforcement data sources, along with public data such as information from credit agencies, said Mr. Sena. But the system is still hampered by having data stored in separate systems that can’t easily communicate. For example, classified reports from different federal agencies can’t be accessed on the same machines, he said.

Last year, the Senate subcommittee on investigations released a report questioning the effectiveness of the centers in fighting terrorism and protecting privacy.

Citizens also play a role in investigations, with the growing culture of crowdsourcing. Users of online discussion board 4chan sifted through photos and spotted a man seen at the marathon finish line wearing black pants, a black shirt and a white hat. That man appeared to bring a backpack to the race, but it seemed to be gone later.

Researchers at Northeastern University in Boston formed a 10-person social-media research team to run a similar project, scheduled to launch Thursday, which would allow people to upload photos from the attack and tag clues. They said they plan to continue their project even if a suspect is found.

How A Community Uses Already-in-Place Camera Systems To Partner With Police For Solving Crime

It involves getting people and places with security cameras to register them with the city.

“We’ve been working on this for awhile,” said Bisceglie, who is overseeing the STS ( Security Through Surveillance ) efforts. “There is so much out there in the community; and by knowing where cameras may be, it will help us make better use of them.”

Helping Police:

As the STS Web page notes, “When a crime occurs, a resident or business may unknowingly record the crime, possible suspects, or an escape route the criminals used. If private surveillance cameras are not registered, the information captured is often lost to law enforcement personnel.”

It also notes that police won’t have direct access to footage captured on private property. Rather, such a registry should help police become better aware of where cameras are throughout Elgin.

“If a crime occurs in the vicinity of a residence or business with registered cameras, the police department will contact registrants to request a copy of their footage for evidence or investigative leads,” the page states.

Bisceglie said work also would involve drawing up floor plans of where cameras are in buildings and dwellings, to further hone what details that might be available to help police working crime as well as missing persons and traffic cases.

Bisceglie said that pretty much every day, patrol officers make requests to see if there is any video available of incidents to which they respond.

Sparking the boom on the private surveillance side is a dramatic drop the last five years in the costs of quality equipment, Bisceglie said.

Clancy recalled that when he began working surveillance, a computer and processor cost $3,800 – compared to the $300 smartphone he now has that is more powerful than the aforementioned system. Likewise, Rouse noted that surveillance camera systems for homes and businesses that used to cost more than $1,000 now can be had for as little as $300 to $400.

Both detectives also pointed out, however, that while technology is rapidly advancing, crime is neither solved as quickly as – nor with the ultra-sophisticated equipment seen on – TV crime shows.

Stay Safe:

Rouse stressed that while police will use private smartphone-made photos and videos, he doesn’t encourage people to put themselves in harm’s way by doing so.

Still, he noted that camera phone recorded evidence has come in handy in local cases, particularly ones involving juveniles who have made habits of posting details both good and bad about their lives online.

And public cameras have played key roles in helping police solve Elgin cases.

Police Cmdr. Glenn Theriault mentioned the Jan. 30, 2009, mistaken-identity murder of Paola Rodriguez along Raymond Street in which footage from a nearby fast-food restaurant – recorded in the same time frame – showed suspect Tony Rosalez, who was convicted of the crime in April 2012.

He also said that ROPE (Resident Officer Program of Elgin) Officer Eric Echevarria helped solve a case involving a burglary in January at St. Joseph Roman Catholic Church in his east-side neighborhood.

Echevarria knew that the church had cameras, which caught the theft of two brass holy water fonts worth about $1,000. And last year, the city also passed an ordinance requiring pawn shops and metal recyclers to save video footage for at least 30 days.

Police checked with a recycler and found an image of the church thief at one of them, which led to the arrest of Daniel Wells, Theriault said.

Lt. Sean Rafferty mentioned a recent case where Elgin Detective David Baumgartner was able to recognize someone committing a robbery at a gas station along Big Timber Road using a knife. Images captured by a store camera showed only the midportion of the man’s face. But according to reports, on April 23, police arrested Daniel Ontiveros for the crime after Baumgartner recognized him from an internal bulletin compiled using the store’s visual information.

Works Both Ways :

Rouse also noted that cameras can be used to corroborate what those on both sides of crime tell them and to clear as well as implicate those who might be involved.

As for where this all might be headed, Theriault said the department eventually would like to expand its use of license plate recognition software beyond the one vehicle that has it now. Such technology can link to other places using it to create a picture of where a particular car has been.

The department eventually also is looking into how, somewhere down the road, cameras already put in place by Kane County and the Illinois Department of Transportation to monitor traffic at intersections can be integrated into Elgin’s surveillance, Theriault noted.

Clancy and Rouse mentioned eventually getting software that would allow police to more smoothly jump back and forth when viewing the cameras in the city’s own systems.

Long-range, Theriault said the department is exploring how a smaller city such as Elgin might use what now are costly technologies that big-cities are using to fight as well as prevent crime.

In the meantime, the concerted effort to bring the community into the surveillance plan is part of a four-pronged approach to policing that involves educating residents and firms, building awareness and forming partnerships, thereby creating efficiencies from crime solving and prevention, Rouse said.

Updated: 6-13-2020

They Used Smartphone Cameras to Record Police Brutality—and Change History

Video-camera technology on our phones got better. In the process, it made eyewitnesses of us all.

In 2008, Steve Jobs had an assignment for a small team of engineers in Cupertino: Make the iPhone record video. After seeing that people liked taking photos with the first iPhones, he wanted to add moving pictures. A year later, Apple released the iPhone 3GS, the first iPhone to record video.

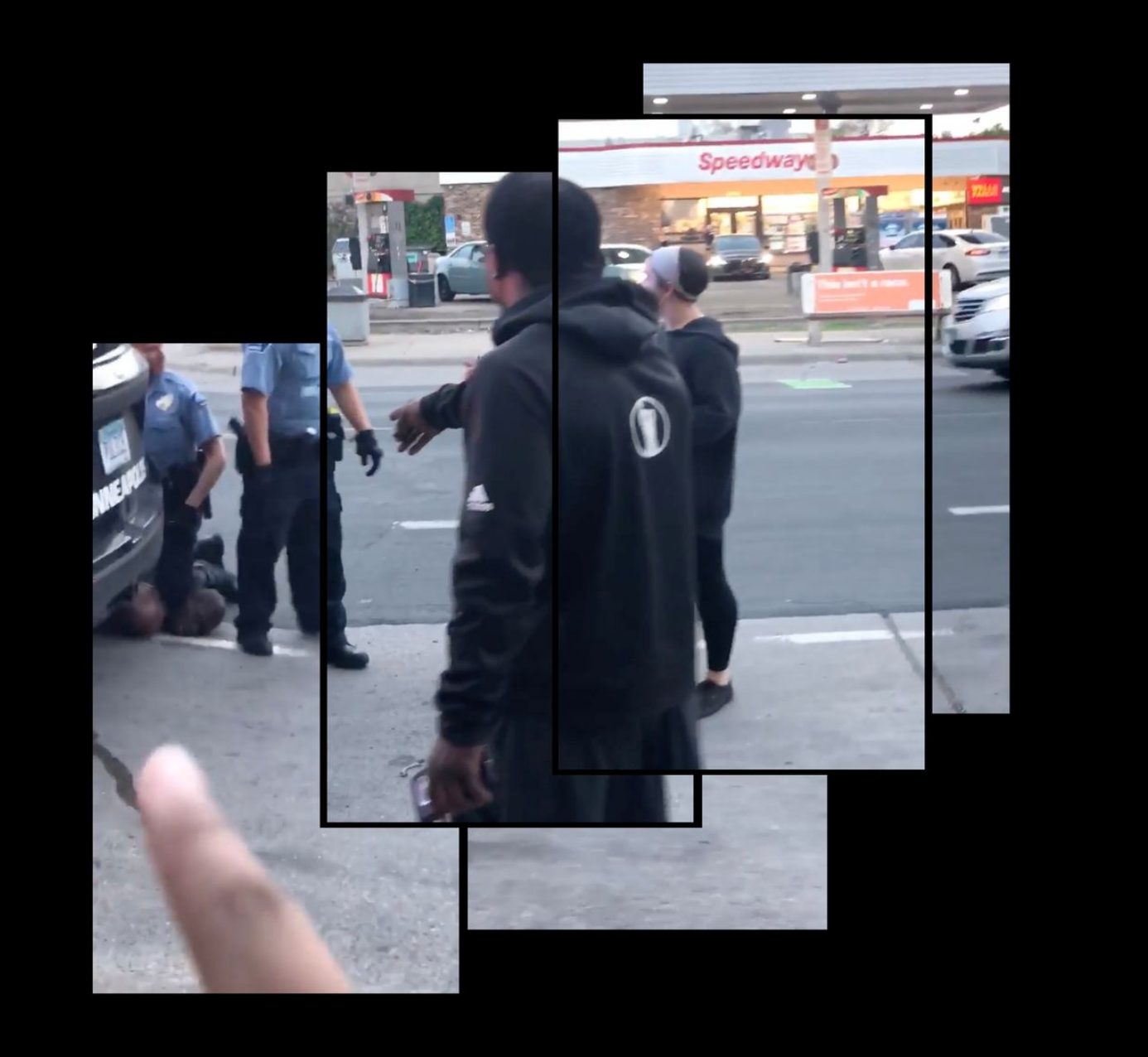

About 10 years and 10 iPhone models later, 17-year-old Darnella Frazier found herself standing on a sidewalk in Minneapolis, swiping on her purple iPhone 11 lock screen to launch the video camera as fast as possible.

She hit the red circle and for the next 10 minutes and 9 seconds she held her phone as steady as she could, capturing George Floyd, a black man crying for his mother as his face was smashed into the pavement by white police officer Derek Chauvin.

“I opened my phone and I started recording because I knew if I didn’t, no one would believe me,” Ms. Frazier said in a statement provided by her lawyer, Seth Cobin.

A day later, May 26, she opened up the Facebook app, and tapped the video of Mr. Floyd to upload it. The world now knows his name.

Over the last decade, while tech companies were focused on marketing megapixels and multiple lenses to better record pastries and puppies, smartphone cameras found a greater purpose.

“This is our only tool we have right now. It is the most effective way to get us justice,” Feidin Santana told me. Mr. Santana used his smartphone in 2015 to film a police officer killing Walter Scott in South Carolina.

“The smartphone is a weapon that tells the story. This is going to tell what happened to me, this is what will tell what took place,” said Arthur Reed, whose organization Stop the Killing surfaced an anonymously filmed video of the 2016 killing of Alton Sterling by a police officer in Baton Rouge, La.

Many white Americans, myself included, failed until recently to grasp one of the biggest impacts of the smartphone: its ability to make the world witness police brutality toward African-Americans that was all too easy to ignore in the past. We could now see, with our own eyes, the black sides of stories that were otherwise lost when white officers filed their police reports.

For this column, I looked back at a decade of incriminating cellphone video, and tracked down many people who bravely used their phones to capture brutality and tragedy on American streets.

2009 – Oscar Grant

2015 – Walter Scott

2020 – George Floyd

All said some variation of the same thing: It’s not that these incidents never happened before, it’s that we have the ability to capture proof and expose it widely—now, more clearly and indisputably than ever. The smartphone’s proliferation and evolving user experience is partly to thank, though through this we’re also discovering its limitations.

Once upon a time, capturing bystander video was about being in the right place, at the right time, with the right equipment.

That is the story of George Holliday on March 3, 1991, brand-new Sony Handycam in hand as he stood on his balcony with a view of Los Angeles police officers beating Rodney King. The footage is shaky, the bodies are hard to make out, the helicopters drown out the screams yet it was enough to set off what Mr. Holliday calls “the first viral video.”

It’s also the story of Karina Vargas, who had her Fujifilm Finepix digital camera the night of Jan. 1, 2009, when she witnessed officer Johannes Mehserle shooting 22-year-old Oscar Grant III at the Fruitvale BART transit station in Oakland, Calif.

Ms. Vargas also had a Motorola Razr cellphone, but she turned on her 10-megapixel Fujifilm because it could record better quality video. (At the time, that meant 480p.) In a series of clips, many of them pixelated and shaky, she captured the officers surrounding Mr. Grant and eventually the sounds of the gunshots.

A day later a local television producer came out to watch what she had recorded; he transferred the footage from her memory card to his laptop and aired it that day.

“If I had this iPhone back then I would have taken much better video,” Ms. Vargas told me. “I would have been able to get closer and I probably would have shared it to Instagram or another place so everyone could see it.” She added, “Right now, there is this culture of ‘Let’s f—ing record these cops.’ It wasn’t that way then.”

Other bystanders recorded from different angles with cellphones, though their details were quite blurry. All were submitted as evidence. In 2010, Mehserle was convicted of second-degree murder.

Jump ahead to 2014. Ramsey Orta and his 2011 Samsung Galaxy phone captured 720p high-definition video of Eric Garner, surrounded by New York City police officers. Mr. Orta filmed police wrestling Mr. Garner to the pavement and putting him in a chokehold. On the video, he said he couldn’t breathe 11 times before he died.

Mr. Orta originally shared the video with the New York Daily News, and it quickly spread across Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. The phrase “I can’t breathe” became a slogan of the Black Lives Matter movement. Though Mr. Garner’s death was ruled a homicide, the officer involved was not indicted.

By 2015, 69% of Americans had a smartphone, according to the Pew Research Center.

Feidin Santana in North Charleston, S.C., had just gotten a new one from a friend, a Samsung Galaxy S5 with a 16-megapixel camera. He happened to be walking to his job when he saw Mr. Scott being chased by officer Michael Slager. Mr. Santana tapped the camera app and began recording for three minutes, capturing Slager shooting Mr. Scott five times as he tried to run. It was the first thing he filmed with the new phone.

“I was getting used to the phone but in less than a few seconds I was able to get to the video option,” recalls Mr. Santana, who doesn’t consider himself tech savvy.

The video, which was used as evidence in the trial, is shaky and at times blurry, but readable enough to see key parts of the incident play out. A jury convicted Slager of second-degree murder. He was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Over the next few years, as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube made uploading, sharing and viewing mobile video easier, buckets of cellular data dropped in price, and smartphone ownership among Americans ages 18 to 49 passed 90%, recordings of police interaction mushroomed.

On July 5, 2016, one of two videos of police officers killing Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge, La., was uploaded to Twitter. One officer was later fired but not charged. The next day, Diamond Reynolds went live on Facebook as she sat next to her dying boyfriend, Philando Castile, who had just been shot by an officer in St. Anthony, Minn. The officer was later found not guilty of second-degree manslaughter.

That brings us to two weeks ago, when Ms. Frazier, only feet away from George Floyd and the police officer bearing down on him, captured it all in 1080p resolution video with the latest iPhone. It’s one of the clearest, highest-resolution videos of such a situation ever captured.

“I will post the video in the morning as soon as I wake up. I don’t give a f—. If it gets taken down I don’t care,” Ms. Frazier said in a live-stream on Facebook a few hours after recording Mr. Floyd’s killing. “At least you all will see for yourselves. I’m pretty sure it’s a murder we’ll be seeing on the news.” Officer Chauvin has since been charged with second-degree murder, the other officers at the scene have also been charged and the city of Minneapolis has moved to restructure its police forces.

Over the past decade, the smartphone changed our behavior. We went from photographing momentous occasions with specialized equipment—remember buying cameras?—to constantly, instantaneously capturing and sharing any moment we choose. Everyone I spoke to who had recorded these scenes of violence used the same word to describe why they did it: instinct.

“I knew what was going on wasn’t right. I felt something was about to happen so I just took out my phone and started recording,” said Brandon Brooks, who filmed Dajerria Becton, a black teenager, being violently wrestled to the ground by a white officer in McKinney, Texas, in 2015. A few days later, the officer resigned.

But capturing video of apparent brutality by those in power comes with a dark consequence: fear of retaliation.

“I didn’t share it right away,” Mr. Santana, the man who filmed the killing of Walter Scott, told me. “I thought my life might be in danger. It’s a tough decision to come forward.” He said he feared the police department would come after him; he also said he wanted to wait to hear the police department’s side of the story. Ms. Vargas said she still vividly remembers an officer trying to get a hold of her camera on the train after she filmed the Oakland shooting of Oscar Grant.

Allissa Richardson, a journalism professor at University of Southern California and author of the book “Bearing Witness While Black,” said that the proliferation of such footage can have an insidious side effect, the expectation of video where none is available. “We are almost asking black people to prove they didn’t deserve this [violence]. We don’t ask white people where the video is after mass shootings,” she said. Plus, the videos can end up being excessively played in the media, she added.

And filming police violence doesn’t lead to an open-and-shut case. John Burris, a civil-rights attorney who represented Mr. Grant’s family, said that “without the videos all I would have had was the testimony of the African-American men against several cops. But ultimately the cops had their own stories about what happened which still made it extraordinarily difficult.”

Police officers are increasingly aware of the presence of smartphone cameras, and aren’t always deterred by them. Police departments have equipped officers with their own body cams or car dashboard cameras—though smartphone footage often provides a different vantage point. Some experts say that qualified-immunity laws and the power of police unions offer bad actors unwarranted protection.

“If someone were to do such a violent act knowing they are on camera, that’s some evil intent right there,” said Sheriff Christopher Swanson, from the Office of Genesee County Sheriff in Flint, Mich. He believes the killing of Mr. Floyd will result in widespread police union reform.

So smartphone videos have been far from a panacea for racial injustice. But at least now, more than ever, we all can see it, clearly and vividly.

The cameras will continue to improve. Like any technology story, what we do with them, and the world we want them to capture, is up to us.

Updated: 9-20-2021

Disappearance of Gabby Petito

Gabrielle Petito is a 22-year-old American woman from Suffolk County, New York, who was reported missing on September 11, 2021, while traveling across the United States with her fiancé.

Her family lost contact with her in late August when she was in or near Grand Teton National Park in Wyoming.

Updated: 11-27-2021

Citizen Surveillance Becomes The New Big Brother

‘The foundational elements of espionage, I argue, have been shattered—they have already been broken.’

— Duyane Norman, a former CIA station chief

Operatives widely suspected of working for Israel’s Mossad spy service planned a stealthy operation to kill a Palestinian militant living in Dubai. The 2010 plan was a success except for the stealth part—closed-circuit cameras followed the team’s every move, even capturing them before and after they put on disguises.

In 2017, a suspected U.S. intelligence officer held a supposedly clandestine meeting with the half brother of North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, days before the latter was assassinated. That encounter also became public knowledge, thanks to a hotel’s security camera footage.

Last December , it was Russia’s turn. Bellingcat, the investigative website, used phone and travel data to track three operatives from Moscow’s FSB intelligence service it said shadowed and then attempted to kill Russian opposition politician Alexei Navalny. Bellingcat named the three. And published their photographs.

Espionage and covert action aren’t what they used to be.

A trained CIA case officer could once cross borders with a wallet full of aliases or confidently travel through foreign cities undetected to meet agents. Now, he or she faces digital obstacles that are the hallmarks of modern life: omnipresent surveillance cameras and biometric border controls, not to mention smartphones, watches and automobiles that constantly ping out their location. Then there is “digital dust,” the personal record almost everyone leaves across the internet.

Combined with advances in artificial intelligence that allow rapid sifting of this data, the technologies are fast becoming powerful tools for foreign adversaries to root out spies, according to current and former U.S. and Western intelligence officials.

“It’s really bad,” a former top U.S. counterintelligence official said of the impact on U.S. espionage operations. “It really challenges the fundamental assumptions and approach of how you do business.”

“Ubiquitous technical surveillance,” as it is known, is now a pervasive concern at the CIA, forcing it to devise new, often more resource-intensive ways of recruiting agents and stealing secrets, the officials said.

In the new environment, it is “much more complicated to conduct traditional tradecraft,” CIA Director William Burns acknowledged during his February confirmation hearing. “The agency, like so many other parts of the U.S. government, is going to have to adapt.” He added: “I’m entirely confident that the women and men of CIA are capable of that.”

In the Dubai case, Israel has never confirmed or denied its involvement. The CIA has declined to comment on its ties to the North Korean leader’s half brother. Russia has denied poisoning Mr. Navalny.

A January report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies think tank said that while advanced digital technologies will also help U.S. spy agencies gather intelligence and spot adversaries, the advantage lies with authoritarian societies like China and Russia that can exert greater control over them.

CIA officers “will struggle to maintain cover and operate clandestinely and face a persistent risk of exposure—of themselves, their agents, and their operational tradecraft,” said the report by a CSIS task force.

In an interview, a senior CIA official disputed suggestions that the agency’s operating space is shrinking, and said it would employ both new and traditional spy tradecraft. “We go to extraordinary lengths to avoid detection of our officers, and the sources we are meeting.”

“Humint isn’t dead, not by a long shot,” the official said, using the acronym for human intelligence.

Others aren’t so sure.

“The foundational elements of espionage, I argue, have been shattered—they have already been broken,” said Duyane Norman, a former CIA station chief who led an early agency effort to adapt spying for the digital age, called “Station of the Future.”

As an example, he asks, how can a CIA officer purport to work for another government agency or private enterprise if his cellphone isn’t regularly present at that entity’s location, there is no record of him making ATM withdrawals or paying for lunch with a credit card in the vicinity, and no sign of him on video cameras there?

Having no electronic “signature”—as in not carrying a cellphone and having no presence on the internet—is itself a tipoff to adversary spy services, Mr. Norman and others said.

In a 2018 speech, Dawn Meyerriecks, who was then deputy CIA director for Science & Technology, said that in about 30 countries, foreign intelligence services no longer bother to physically follow agency officers “when we leave our place of employ,” an apparent reference to U.S. embassies. “The coverage is good enough that they don’t need to. Between CCTVs and wireless infrastructure.”

A recent top secret cable from counterintelligence officials at CIA’s headquarters to stations and bases world-wide warned that a large number of agency informants in foreign countries were being captured, according to officials familiar with its contents.

The cable suggested a more difficult operating environment for U.S. spies abroad, in part as a result of pervasive digital surveillance. It was first reported by the New York Times.

Intelligence officials, citing operational secrecy, declined to discuss further details of how such surveillance in the hands of Chinese, Russian, Iranian and other governments potentially crimps the CIA’s mission—or how the agency is responding.

But they offered outlines of what the future of spying might look like.

Crossing international borders under an assumed name is rapidly becoming yesteryear’s tradecraft, because of biometrics like facial recognition and iris scans, several former officials said.

“It’s more difficult for intelligence officers to masquerade under alias,” said a retired Western intelligence officer who estimated he had nine false identities during his career, and credit cards for each.

More spying will be done in “true name,” meaning the spy won’t pose as someone else, but “live their cover” as a businessperson, academic or other professional with no obvious connection to the U.S. government.

Moscow and Beijing have sent “a massive influx” of what are known as nontraditional intelligence collectors abroad globally, said former U.S. counterintelligence chief William Evanina. Asked if the U.S. would do likewise, he replied: “That would be a great presumption on your part.”

Spying is also becoming more of a team sport. Where once a lone spy conceived and conducted an operation—meeting an agent, retrieving cached documents—in the future, it will require a group to help watch for digital surveillance and guide the CIA officer around it.

Ms. Meyerriecks in her 2018 speech described how, as a test, a CIA team compiled a map of surveillance cameras in the capital of a U.S. adversary she didn’t name, along with the type of camera and the direction each was pointed. Using artificial intelligence, the team plotted a surveillance-free route that a CIA officer could travel.

While headquarters colleagues monitor over a computer dashboard, the CIA officer on the street might wear a smartwatch telling her if she is “green”—free of digital surveillance—yellow, or red.

These undertakings require more time, personnel and other resources.

It is more “Mission Impossible” than James Bond, and “implies fewer operations, total” with a smaller pool of foreigners recruited to spy for the U.S., said Mr. Norman. “You’re going to spend a lot more energy working on the few that are important.”

There are also endless digital tricks to play in what Mr. Evanina called “the technological version of cat and mouse.” For example, it is possible to “spoof” a cellphone’s location, misleading foreign spycatchers to think their quarry is in one place, when he is safely in another, current and former CIA officials said.

The officials say the CIA, which turns 75 next year, has faced and overcome profound technological challenges before. In Cold War-era Moscow of the 1980s, it was long assumed the agency couldn’t recruit and meet Soviet spies under the KGB’s nose.

A former station chief and his colleagues devised ways, including new methods of short-range communications with agents and of disguise, and the agency during that period was able to run one of the most valuable Soviet spies of the Cold War, Adolf Tolkachev.

“Most technological challenges are surmountable,” the senior CIA official said. “We play great offense, and aren’t sitting around in a defensive crouch.”

Citizen Surveillance Is Playing,Citizen Surveillance Is Playing,Citizen Surveillance Is Playing,Citizen Surveillance Is Playing,Citizen Surveillance Is Playing,Citizen Surveillance Is Playing,Citizen Surveillance Is Playing,Citizen Surveillance Is Playing,Citizen Surveillance Is Playing,Citizen Surveillance Is Playing,Citizen Surveillance Is Playing,Citizen Surveillance Is Playing,Citizen Surveillance Is Playing,Citizen Surveillance Is Playing,Citizen Surveillance Is Playing,Citizen Surveillance Is Playing,Citizen Surveillance Is Playing,Citizen Surveillance Is Playing,

Related Articles:

Hundreds of Police Killings Go Undocumented By Law Enforcement And FBI (#GotBitcoin?)

The FBI’s Crime Data: What Happens When States Don’t Fully Report (#GotBitcoin?)

Citizens Cannot Turn The Police Away If They Are Unhappy With Their Services (#GotBitcoin?)

Have You Broken A Federal Criminal Law Lately? Who Knows? No One Has Been Able To Count Them All!!!

Before Leaving, Sessions Limited Agreements To Fix Police Agencies (#GotBitcoin?)

Mobile Justice App. (#GotBitcoin?)

SMART-POLICING, COMPETITION AND WHY YOU SHOULD CARE (PART I, Video Playlist)

Your Questions And Comments Are Greatly Appreciated.

Monty H. & Carolyn A.

Go back

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.