Ultimate Resource On Insider Trading

CEOs are departing in droves. Also, America’s corporate insiders along with politicians dumped shares at record levels. Bad news for the stock market. Ultimate Resource On Insider Trading

* CEOs Are Departing In Droves.

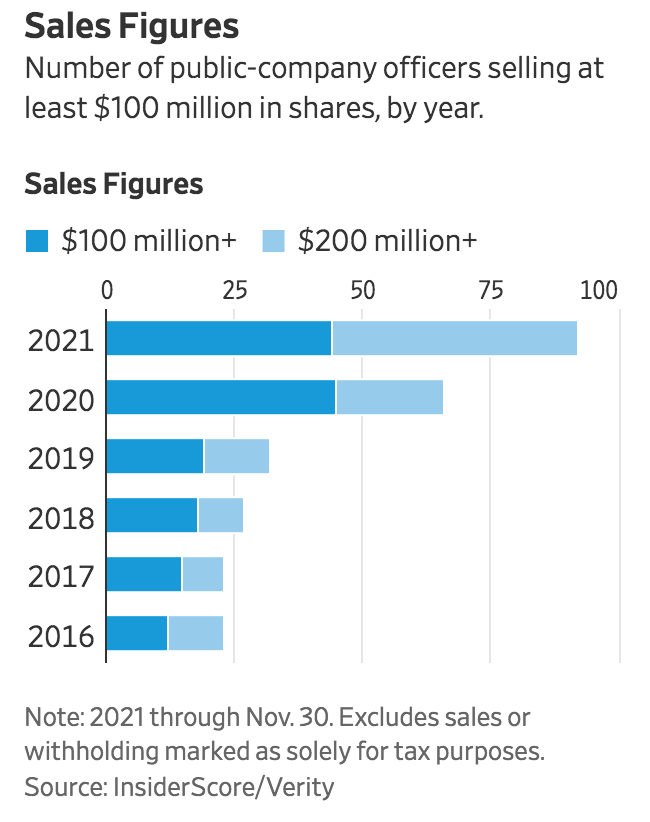

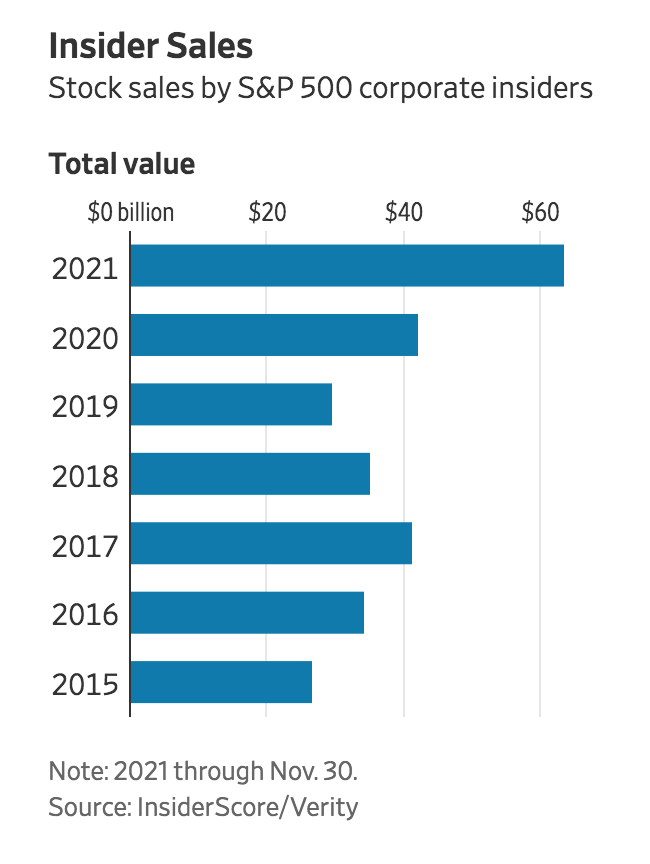

* America’s Corporate Insiders, Which Include Chief Executives, Dumped Company Shares At Record Levels.

* One Wall Street Firm Is Projecting A Stagnant Year For U.S. Companies.

The stock market is in trouble. The Dow Jones Industrial Average printed its worst one-day point drop in history after plunging 1,191 points Thursday. The S&P 500 is also making history. Over the last six days, the index tumbled by 10% from the all-time high at a pace never seen before.

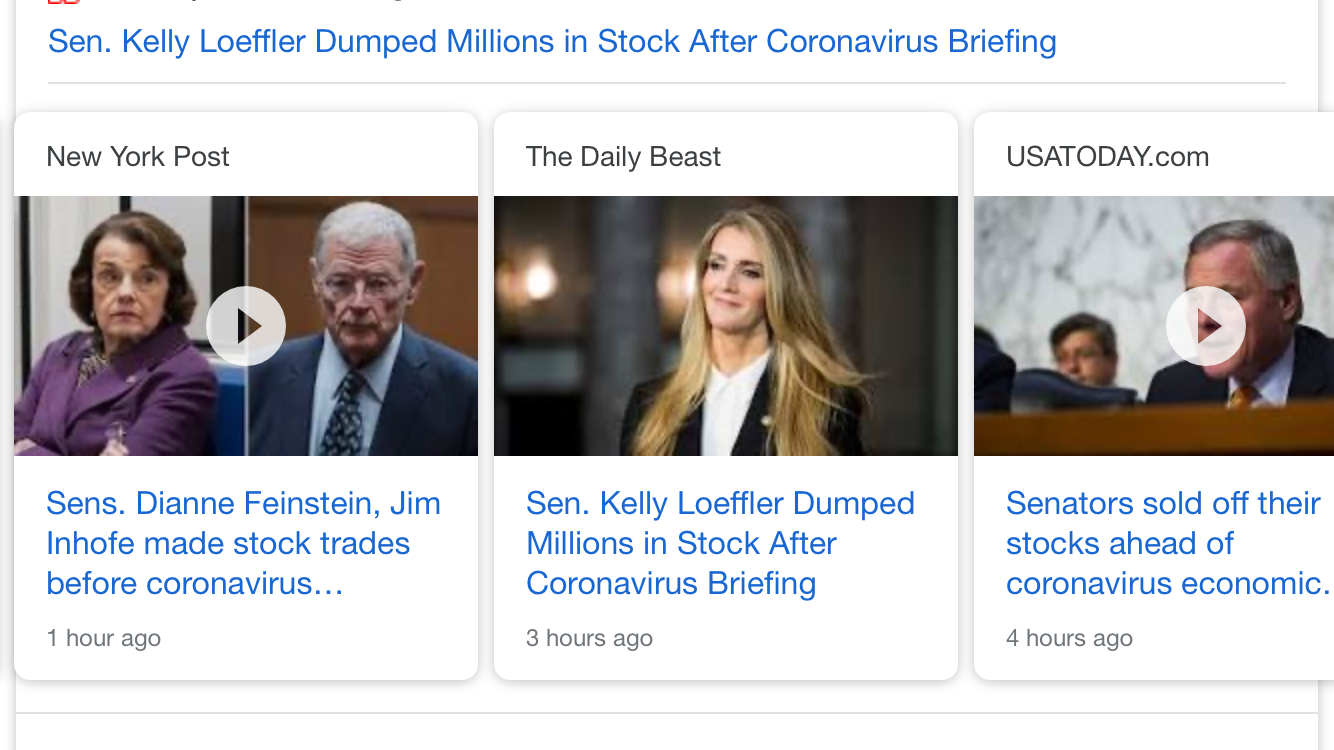

Numerous Senators In The Trump Adminstration Dumped Millions In Stock Weeks Before Coronavirus Pandemic Hit US!!!

Multiple members of Congress and spouses made sales that saved them from losses before markets slid.

Weeks before the new coronavirus pandemic sent the stock market plummeting, several members of Congress, their spouses and investment advisers each sold hundreds of thousands of dollars in stock after lawmakers attended sensitive, closed-door briefings about the threat of the disease.

Related:

Track US Politicians Stock Trades

Insiders Profited From Advanced Knowledge of Donald Trump (Tariff, Covid19, Etc.) Announcements

U.S. Corporate Insiders Selling Shares At Fastest Pace Since 2008

Some of the well-timed sales saved the senators and their spouses as much as hundreds of thousands of dollars in potential losses, a Wall Street Journal analysis of the trades shows.

Sen. Richard Burr, a top Republican from North Carolina who sits on two committees that received detailed briefings on the growing epidemic, reported in disclosure reports that he and his wife on Feb. 13 sold shares of companies worth as much as $1.7 million.

The Journal analysis shows that the shares sold by the Burrs were worth—at minimum—$250,000 less at the close of trading on March 19 than they were when the senator and his wife sold them. Mr. Burr said in a statement that he relied upon “public news reports to guide my decisions regarding the sale of stocks.”

On Friday morning, Mr. Burr said he “understands the assumption that many could make in hindsight” and asked the Senate Ethics Committee chairman “to open a complete review of the matter with full transparency.”

While some market analysts were warning at the time of the potential damage the emerging coronavirus could cause to the stock market, the sales also came at a time when President Trump and some Republican politicians were playing down the potential harm from the epidemic.

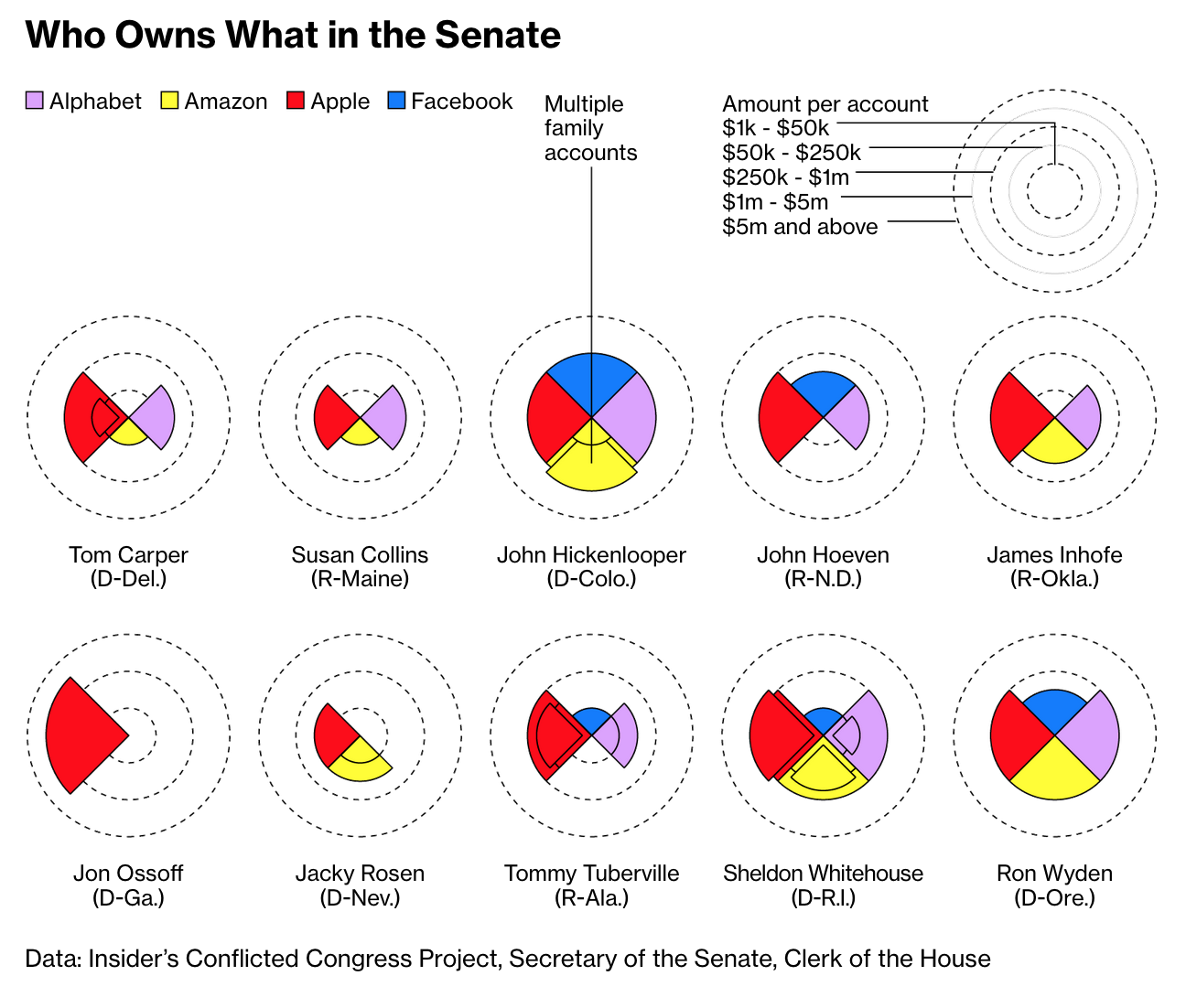

Other senators who were actively trading before the spreading infectious disease caused the markets to fall were Republican Senators Kelly Loeffler and David Perdue of Georgia, and James Inhofe of Oklahoma. The husband of Sen. Dianne Feinstein, the California Democrat, also sold stock before the market downturn.

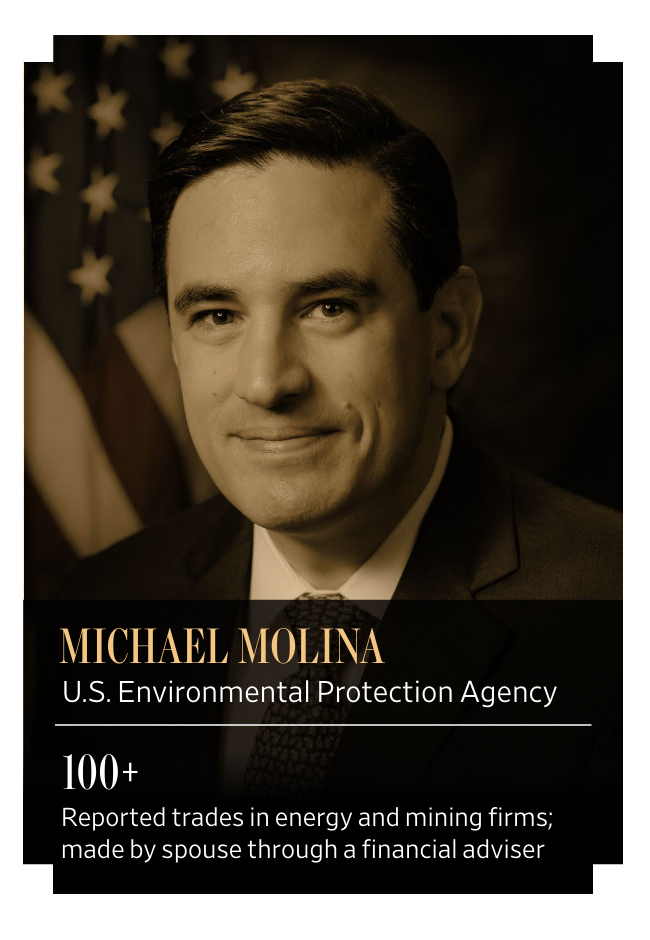

Ms. Loeffler and Ms. Feinstein, who are both married to investment professionals, said they had been unaware of the trades because they are handled by advisers. Mr. Perdue said his portfolio is managed by an investment adviser who regularly makes dozens of trades and was buying as well as selling shares of companies at the time. Mr. Inhofe in a statement said he also has an investment adviser and doesn’t manage trades.

Mr. Burr, chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee, which has been receiving frequent briefings on the spread of Covid-19 since it emerged in China, made 33 stock trades on Feb. 13 worth between $628,000 and $1.7 million, according to the filings. Congressional rules require that trades be reported in ranges, not precise figures.

Mr. Burr, who is regarded as the Senate’s leading authority on pandemics as the author of the 2006 Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act, is also on the Senate health committee, which was briefed on the coronavirus on Jan. 24.

Three of Mr. Burr’s sales were in hotel company stocks—Park Hotels and Resorts Inc., Wyndham Hotels & Resorts Inc. and Extended Stay America Inc. —which have seen their value drop 74%, 63% and 50%, respectively, since Mr. Burr made the sales.

Mr. Burr and his wife also sold between $96,000 and $265,000 in stock between Jan. 31 and Feb. 4, the filings show, including additional shares of Extended Stay.

In an opinion piece published on Fox News online, Mr. Burr said, “Thankfully, the United States today is better prepared than ever before to face emerging public health threats, like the coronavirus.”

Behind closed doors, in a meeting with a small group of constituents in Washington, Mr. Burr warned them to prepare for dire economic effects of the coronavirus, according to a recording obtained by NPR. On Twitter, Mr. Burr called that report a “tabloid-style hit piece.”

On Friday, Mr. Burr explained his trades were motivated by news reports. “Specifically, I closely followed CNBC’s daily health and science reporting out of its Asia bureaus at the time,” he said.

Sales were also reported by two other members of the Intelligence Committee, Mr. Inhofe and Ms. Feinstein.

Between Jan. 27 and Feb. 20, Mr. Inhofe sold between $230,000 and $500,000 of stock in several companies, including Brookfield Asset Management, a real-estate company.

Mr. Inhofe in a statement said that his investment adviser has been moving him out of stocks and into mutual funds after he took the chairmanship of the Senate Armed Services Committee in December 2018 “to avoid any appearance of controversy.

Richard Blum, the husband of Ms. Feinstein and a professional investment manager, sold shares of Allogene Therapeutics Inc., a biotech company, on Jan. 31 and Feb. 18 in amounts between $1.5 million and $6 million.

Ms. Feinstein’s spokesman said the senator wasn’t involved in the sales. “All of Senator Feinstein’s assets are in a blind trust, as they have been since she came to the Senate. She has no involvement in any of her husband’s financial decisions,” her spokesman, Tom Mentzer, said in an email.

Matthew Sanderson, a political ethics attorney for Caplin & Drysdale, said he advises his congressional clients either to invest in mutual funds and 401(k)s, or turn investments over to an adviser with a regime to separate the lawmaker for the decision-making.

Mr. Burr’s statement that he acted based upon what he heard from the news media, and not what he learned as a committee chairman, could land him in hot water, Mr. Sanderson said. “That’s pretty weak tea, as for defenses,” Mr. Sanderson said. “That really doesn’t pass muster.”

In 2012, President Obama signed the Stop Trading on Congressional Knowledge Act to outlaw members of Congress and other government employees from engaging in insider trading based on information learned through their jobs.

The public interest group Common Cause filed complaints asking the Justice Department, the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Senate Ethics Committee to investigate the trades of Sens. Burr, Feinstein, Loeffler and Inhofe for possible violations of the law. A Common Cause spokesman said the group’s lawyers had just learned of Mr. Perdue’s trades and were considering adding him to the complaint.

Ms. Loeffler also sits on the Senate’s health committee, which had a closed-door briefing on Jan. 24 about the virus with presentations from the leading U.S. public-health officials, including Dr. Anthony Fauci, the top infectious-diseases specialist in government.

That day, Ms. Loeffler reported, she and her husband began making more than two dozen transactions, primarily selling millions of dollars in companies, including retailers AutoZone Inc. and Ross Stores Inc. They sold between $1.28 million and $3.1 million in stock.

By selling stock when they did, Ms. Loeffler and her husband avoided at least $480,000 in losses as of market close on March 19. The couple also purchased two stocks in February, one of which rose in value despite the market crash. Citrix Systems Inc., which makes remote computing software, rose nearly 3% value since the couple bought shares on Feb. 14.

Ms. Loeffler said neither she nor her husband make her own day-to-day decisions on purchases and sales. She said didn’t learn about these transactions until three weeks after they were made. “This is a ridiculous & baseless attack,” Ms. Loeffler said on Twitter.

Ms. Loeffler’s husband, Jeffrey Sprecher, is the chairman of the New York Stock Exchange.

Ms. Loeffler was appointed to her seat in December after Sen. Johnny Isakson resigned for health reasons and is locked in a fierce intraparty battle for a Senate seat in Georgia. Her primary rival, Rep. Doug Collins, criticized the senator. “It’s a sad situation,” Mr. Collins said.

The stock sales of Ms. Loeffler and Mr. Sprecher were reported earlier by the Daily Beast.

The stock market is cratering and corporate America’s chief executives have been a step ahead of the disaster. Many have been dumping shares prior to the correction. On top of that, top honchos of big U.S. companies are leaving their posts in record numbers. These signs indicate that the longest bull market in history may be over.

Corporate Captains Are Abandoning Ship

Chief executives of top companies in the U.S. are leaving their posts at a pace not seen in nearly two decades. Challenger, Gray, and Christmas reported that 1,480 CEOs departed in 2019. This caught the attention of some analysts as C-level executives don’t often step aside while both the economy and the stock market are booming.

The trend continued in January 2020 with 219 chief executives calling it quits. The number represents the highest CEO departures on a monthly basis since 2008. Are they getting out while the getting is good?

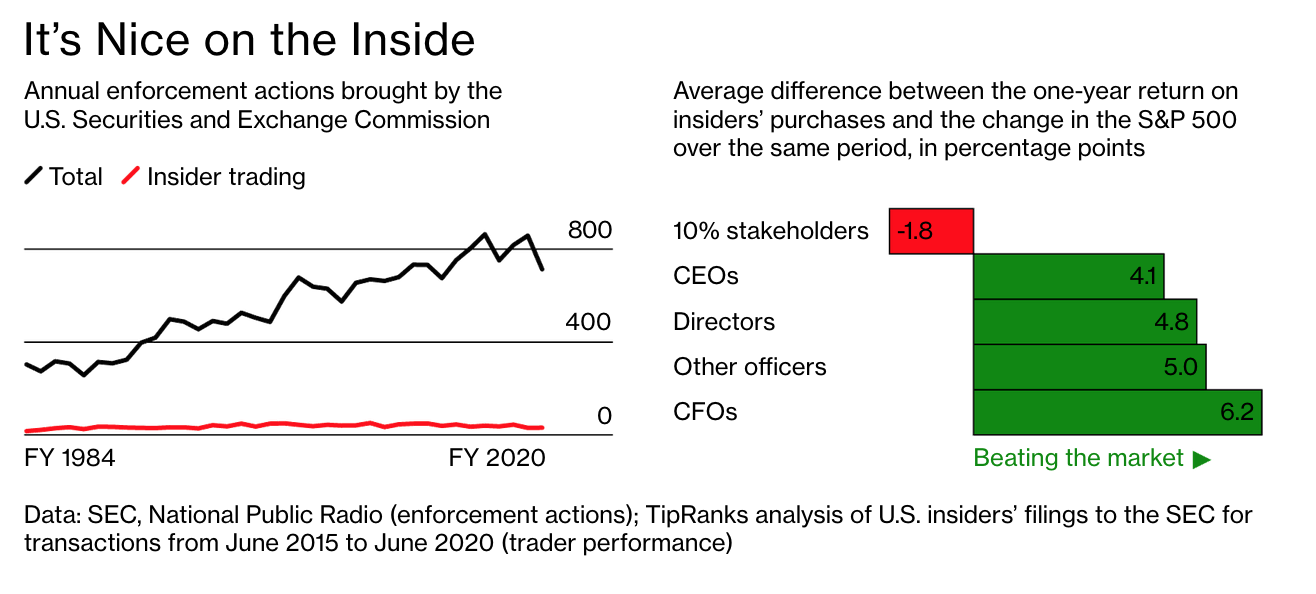

When CEOs vacate their positions while the stock market is trading at record highs, it can be a sign that the business cycle has peaked. Massive insider selling of shares adds weight to this theory.

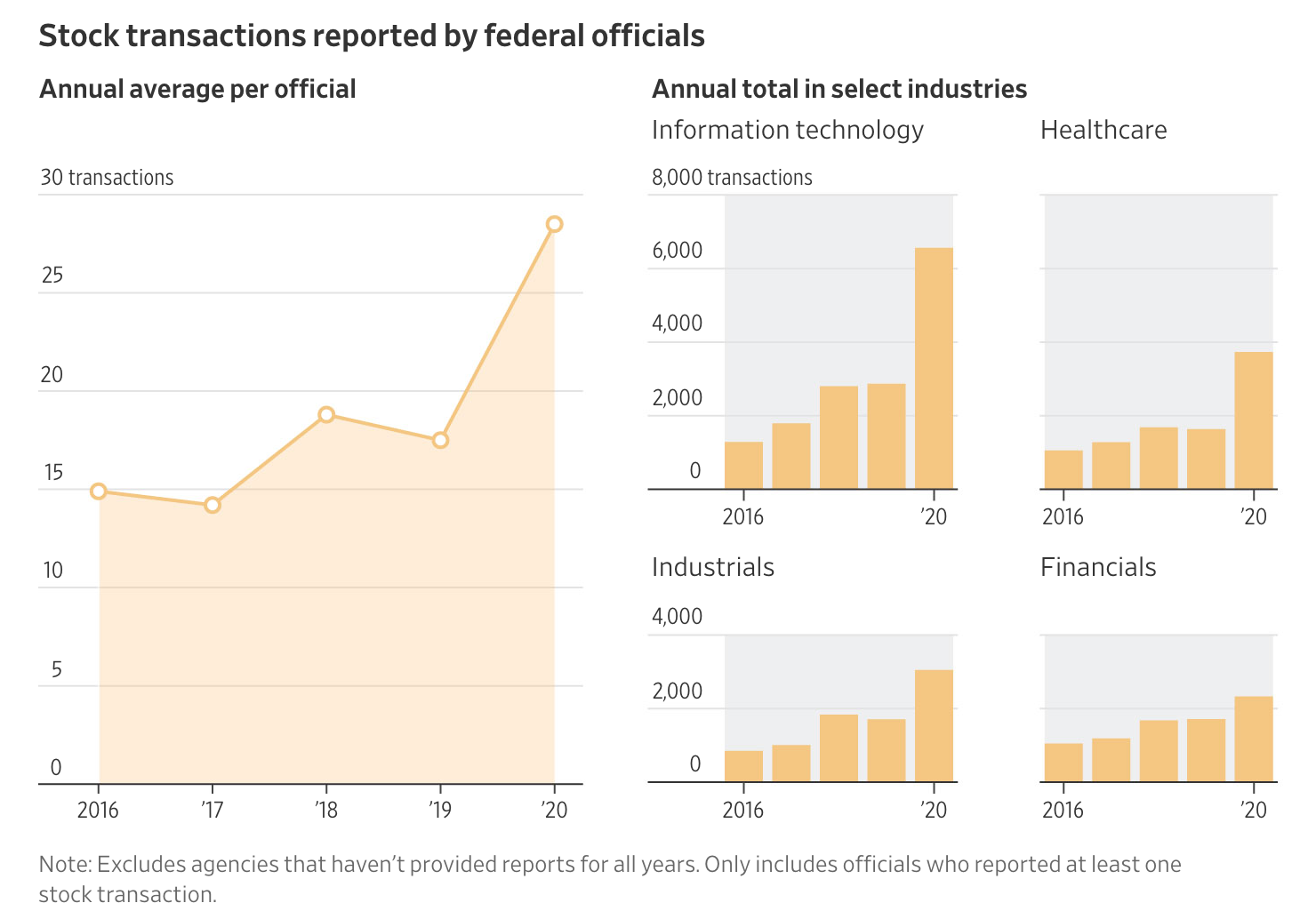

Financial Times reported that corporate insiders, such as chief executives and chief financial officers, sold an estimated $26 billion worth of shares in 2019. This puts insider selling at the highest level since 2000 when corporate insiders sold $37 billion worth of stock in the midst of the dotcom bubble.

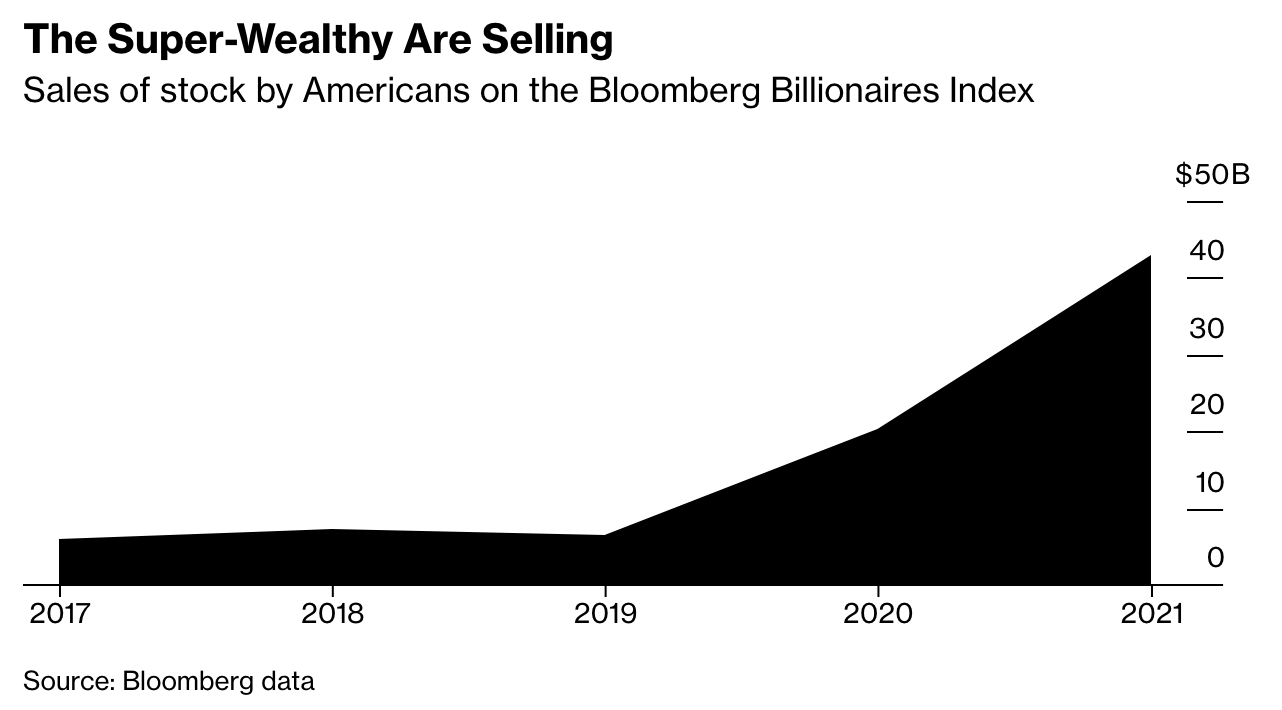

Jeff Bezos alone sold $4 billion worth of Amazon stock in a week. Meanwhile, Warren Buffett has been patiently sitting on a cash pile worth $130 billion. The writings on the wall suggest we may be witnessing the beginning of the end of the longest bull market in history.

Earnings Growth for U.S. Companies Will Be Flat This Year

To add fuel to the fire, one Wall Street firm estimates that 2020 will be a stagnant year for U.S. companies. Goldman Sachs revised its earnings estimates for 2020 to $165 per share from $174 per share. The change represents 0% growth for the year.

The multinational investment bank expects coronavirus to shock both supply and demand in China and the United States. In a note to clients, Goldman equity strategist David Kostin wrote,

“We have updated our earnings model to incorporate the likelihood that the virus becomes widespread.”

He added,

“Our reduced profit forecasts reflect the severe decline in Chinese economic activity in 1Q, lower end-demand for US exporters, disruption to the supply chain for many US firms, a slowdown in US economic activity, and elevated business uncertainty.”

Once again, it appears that many chief executives are a step ahead of a disaster. The captains of corporate America are fleeing like rats on a sinking ship while dumping shares in record numbers. The best days of the longest bull market in history may be over.

Updated: 4-9-2020

Former Bakkt CEO To Sell All Holdings After Insider Trading Accusations

Following major accusations of insider stock trading during the coronavirus-induced market crash, Senator Kelly Loeffler (R-GA), the former CEO of Bakkt, is liquidating her holdings along with her husband.

In an April 8 tweet, Loeffler said that she and her husband Jeffrey Sprecher, CEO of ICE, which is the company that owns Bitcoin (BTC) options contracts regulator Bakkt, are liquidating their holdings in managed accounts to focus on tackling the coronavirus situation.

“I’m Doing It Because The Issue Isn’t Worth The Distraction”

The former CEO of Bakkt has also published an opinion piece in the Wall Street Journal, emphasizing that her action is not caused by Senate requirements but rather a strong commitment to defeat the coronavirus.

Loeffler Added That She Will Report All Transactions In The Public Periodic Transaction Report:

“I am taking action to move beyond the distraction and put the focus back on the essential work we must all do to defeat the coronavirus. Although Senate ethics rules don’t require it, my husband and I are liquidating our holdings in managed accounts and moving into exchange-traded funds and mutual funds. I will report these exiting transactions in the periodic transaction report I file later this month.”

Accusations Of A Coronavirus Insider Trading Scandal

As reported by Cointelegraph, Loeffler came under fire on March 20, with reports claiming that she sold millions in stock within days of a private Senate Health Committee hearing on the novel coronavirus.

American political commentator Keith Boykin explicitly accused Loeffler of being involved in a “coronavirus insider trading scandal” alongside other Senators including Richard Burr, Jim Inhofe and Ron Johnson.

Loeffler rejected the accusations of improper trading, claiming that she is not directly involved in decisions regarding her portfolio. As reported, the former Bakkt CEO explained that a third party person or set of advisors is tasked with making those decisions.

Loeffler Was Delaying Her Financial Disclosure After Swearing Into The Senate

Loeffler was sworn into the United States Senate on Jan. 6, 2020 after serving as CEO of digital asset exchange Bakkt for about a year.

After taking her seat in the Senate, Loeffler was reportedly delaying her Financial Disclosure Report. The report is a basic requirement for all officials that reveals potential conflicts of interest by identifying asset holdings.

Updated: 5-16-2020

Former Bakkt CEO Hands Documents To DoJ Amid Insider Trading Controversy

Former Bakkt CEO Kelly Loeffler sent documentation concerning her stock trades to the Justice Department amid insider trading accusations.

The former chief executive officer of both Bakkt and the New York Stock Exchange’s parent company Intercontinental, U.S. Senator Kelly Loeffler, has handed over documentation concerning her trading activities to the U.S. Justice Department, or DoJ, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and the Senate Ethics Committee.

Loeffler is seeking to quell widespread accusations of improper trading, after the third party managing Loeffler and her partner’s portfolio offloaded millions in shares shortly after the senator attended a closed-door senate hearing on coronavirus in January.

In a statement issued on May 14, Loeffler claimed that the documents evidence that both her and her husband, Jeffrey Sprecher, chairman of the New York Stock Exchange, “acted entirely appropriately and observed both the letter and the spirit of the law.”

Senator Loeffler Relinquishes Trading Documents

Since operating Intercontinental Exchange and the New York Stock Exchange, decisions surrounding Loeffler and Sprecher’s portfolios have purportedly been made by “multiple third-party advisors” without input from either individual.

“The documents and information demonstrated her and her husband’s lack of involvement in their managed accounts, as well the details of those accounts,” Loeffler’s statement said.

The accusations stem from 27 stock sales that were executed on Loeffler and Sprecher’s behalf during February — a period through which Loeffler consistently expressed confidence in the U.S. economy, despite her enormous sell-off amid the worsening coronavirus pandemic.

The pair also made a number of six-figure investments into Citrix — a firm selling technological solutions for distributed workplaces.

Richard Burr Under FBI Investigation For Improper Trading

The move follows reports detailing a probe launched by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, or FBI, into republican senator, Richard Burr, regarding stock trades that he made following the same hearing. Senator Burr has handed his phone to investigators and was served a search warrant at his address.

Loeffler has repeatedly declined to answer questions regarding whether she has been contacted by the FBI regarding her or her husband’s trades.

The FBI has also contacted democratic Senator Dianne Feinstein concerning stock transactions made by her husband.

Updated: 5-16-2020

NBA Star Wants Fans To Buy His Contract For $24.6M… Because Bitcoin?

Spencer Dinwiddie has launched a crowdfunding campaign in a bid to sell his NBA contract to his fans for the cash equivalent of 2,625.8 BTC.

The latest development in pro basketballer Spencer Dinwiddie’s efforts to tokenize his NBA contract has seen the star launch a Gofundme campaign in an attempt to raise the cash equivalent of the 2,625.8 Bitcoins (BTC) — worth roughly $24.6M at time of writing.

Dinwiddie launched the campaign, oddly titled ‘Dinwiddie X BTC X NBA’, to purportedly affirm his “commitment to [his] previous tweets” that offered his fans the opportunity to choose which NBA team he would go to in exchange for the value of his contract in Bitcoin.

Dinwiddie Abandons Crypto Campaign, Wants Cash Instead

However, the new campaign is requesting the cash equivalent of the BTC he previously asked for — giving the $24.63 million fundraiser little relation to Bitcoin.

If unsuccessful, Dinwiddie claims that 100% of the money raised will be designated to an undisclosed charity.

Since launching the campaign roughly 11 hours ago, Dinwiddie’s bizarre fundraiser has raised $690 from 65 donors.

Sporting Organizations Tokenize Athletes

During September 2019, Dinwiddie first announced his intention to tokenize his then-reported $34 million NBA contract extension — however, the offer was framed as an opportunity for investors to receive principal and interest.

While many sporting organizations have sought to establish partnerships with crypto firms to offer gamified tokenized representations of stars to fans in recent months, few initiatives appear to have taken off.

Last month, billionaire investor and owner of the NBA’s Dallas Mavericks, Mark Cuban, revealed that since relaunching Bitcoin as an option for fans to purchase tickets and merchandise in August 2019, the team has taken in a measly $130 in BTC.

Updated: 9-28-2020

Nominee To Financial Regulator CFTC Traded Stocks, Options While In Government

Robert Bowes, a housing official, bought options in cruise-ship operator, shares of in-flight internet company.

President Trump’s nominee to the agency that regulates the vast derivatives market is no stranger to risky bets.

Robert Bowes, a political appointee in the Department of Housing and Urban Development, has reported 140 trades of stocks and options that collectively amount to between $671,000 and $3.2 million since joining the government in early 2017. Three bets on options or individual stocks were larger than $50,000 each.

Disclosure forms filed by Mr. Bowes, a former banker and fund manager nominated by Mr. Trump to the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, list wagers against cruise operator Royal Caribbean Group, bets on market volatility and purchases of small-cap stocks.

Ethics rules don’t ban government officials from trading, as long as they steer clear of conflicts of interest and don’t take advantage of inside information, which Mr. Bowes said he didn’t. What was unusual, ethics experts said, was the frequency of his transactions, the high-stakes bets he sometimes made and the exotic securities he sometimes traded. On several occasions in 2018 and 2020, he bought and sold thousands of dollars of options on the same day.

“It is literally day trading,” Robert Rizzi, a partner at law firm Steptoe & Johnson LLP who advises government officials and nominees on financial disclosure, said after reviewing Mr. Bowes’s filings. “When they’re in the government, a lot of them don’t have time to do this, so it’s pretty amazing that he’s doing all this trading.”

Despite his investment activity, which continued into August of this year, Mr. Bowes listed no financial income, brokerage accounts or bank accounts on his year-end 2018 or 2019 financial disclosures.

In response to questions from The Wall Street Journal, Mr. Bowes said that he made a mistake on the 2018 filing and that his bank and brokerage-account balances at the end of 2019 were too low to require disclosure.

Mr. Bowes, 59 years old, had a decadeslong career in finance as a vice president at Chase Manhattan Bank and a director of counterparty risk at government-backed housing-finance giant Fannie Mae.

A staffer on Mr. Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign, Mr. Bowes was appointed senior adviser to HUD in January 2017 and has since held several positions within and outside the department, including stints as a policy adviser to Stephen Miller, a top aide to Mr. Trump, and in the Office of Personnel Management.

In August, Mr. Trump nominated Mr. Bowes to a seat on the five-member CFTC, a financial regulator that oversees derivatives markets and enforces laws against insider trading and fraud.

If he is confirmed by the Senate Agriculture Committee, Republicans can maintain their 3-2 majority on the commission until 2022, giving them the chance to block tougher financial regulations if Joe Biden wins the presidential election in November and appoints a Democrat to head the commission.

In his most recent role at HUD as director of faith-based initiatives, Mr. Bowes advocated a plan to shelter homeless residents of New Orleans on a Carnival Corp. cruise ship following the Covid-19 outbreak, despite being told by Housing Secretary Ben Carson to drop the idea, according to people familiar with the matter.

David Bottner, executive director of the New Orleans Mission, an evangelical Christian organization that supports the cruise-ship idea and hoped to manage it, said Mr. Bowes traveled to New Orleans a few months ago to discuss the plan with him. City officials were opposed to the idea, LaTonya Norton, a spokeswoman for the city said.

In June and July, Mr. Bowes reported 13 trades to buy or sell put options on shares of Royal Caribbean, a rival cruise operator.

Several of the transactions were valued at between $15,000 and $50,000, his disclosure forms show. Put options give the holder the right to sell shares at a predetermined price and are typically used by investors to bet against a company’s stock. It couldn’t be determined whether Mr. Bowes made a profit or a loss on those trades.

“HUD initially explored in May, June and July connecting the cruise-ship companies with the large homeless shelters operating in U.S. port cities,” Mr. Bowes said, without specifying whether this was his idea. He added that he hadn’t been involved in the plan since early July.

Mr. Bottner said Sept. 1 that he had last spoken with Mr. Bowes “a couple weeks ago,” telling the HUD official he had been unable to secure a berth for the vessel in New Orleans and that the plan’s chances of coming to fruition were diminishing.

Carnival didn’t comment. Royal Caribbean didn’t comment on Mr. Bowes’s trades but said it had been contacted by HUD earlier this year “about the possibility of using cruise ships for homeless housing. After preliminary inquiries, we decided it was not practical and we walked away from it,” company spokesman Jonathon Fishman said in an email, without providing additional details.

A HUD spokesman declined to comment on Mr. Bowes’s investment activity or the cruise-ship plan but said he is “a talented public servant who is more than qualified to handle the new job he is taking on.” A White House official said Mr. Bowes’s financial disclosure was cleared by the Office of Government Ethics before his nomination to the CFTC.

On March 26, 2018, Mr. Bowes bought 15,500 shares of Genworth Financial, a Richmond, Va.-based insurance company with a market capitalization of less than $2 billion. The stock closed that session at $2.88 a share, making Mr. Bowes’s investment worth about $45,000.

The following day, Genworth and Beijing-based financial-holding company China Oceanwide Holdings Group Co. agreed to extend a merger deal that was pending before a U.S. government panel, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S., which reviews foreign investments.

On June 11, the first trading day after Cfius approved the merger, Genworth’s shares jumped 27% to $4.82. Mr. Bowes sold his shares on Nov. 8, when Genworth’s stock closed at $4.71, increasing the value of this stake by almost $30,000.

In a written response to questions about the trades, Mr. Bowes said he had no inside or advance information, and no knowledge of Cfius’s deliberations. He also disputed the notion that the bet was well-timed, without providing further details.

In October and November of 2018, Mr. Bowes bought between $53,000 and $145,000 of call options on shares of Bermuda-based shipping company Golar LNG, according to his disclosures. Call options give the holder the right to buy shares at a predetermined price.

He said in a text message to the Journal that he held the options until Jan. 3, 2019, when he sold them for about $41,000.

“I thought I had sold the GLNG call positions just before year end but instead sold them a business day or two later,” Mr. Bowes said in the text message. He said he has submitted a letter to HUD’s ethics officer to amend that form.

Other trades included dozens of bets on market volatility and the purchase of between $65,000 and $71,000 of shares in Gogo Inc., an in-flight internet provider with market capitalization of less than $1 billion. Mr. Bowes said in another text message that he sold those shares in 2018, though the transaction doesn’t appear in his disclosure forms. It couldn’t be determined whether Mr. Bowes made a profit or a loss on those trades.

Regulations require federal employees to disclose cash holdings above $5,000 and financial assets, such as stocks, worth more than $1,000. Mr. Bowes said his bank and brokerage balances were below those thresholds at the end of 2019. Money for his more recent trades, he said, has come from his bank account and income this year.

Mr. Bowes said his trading isn’t unusual and pointed to his career in finance.

“I was a fund manager,” he said in a text message. “I banked the securities brokerage industry. I have a 30+ year career covering large complex financial institutions.”

Updated: 7-8-2021

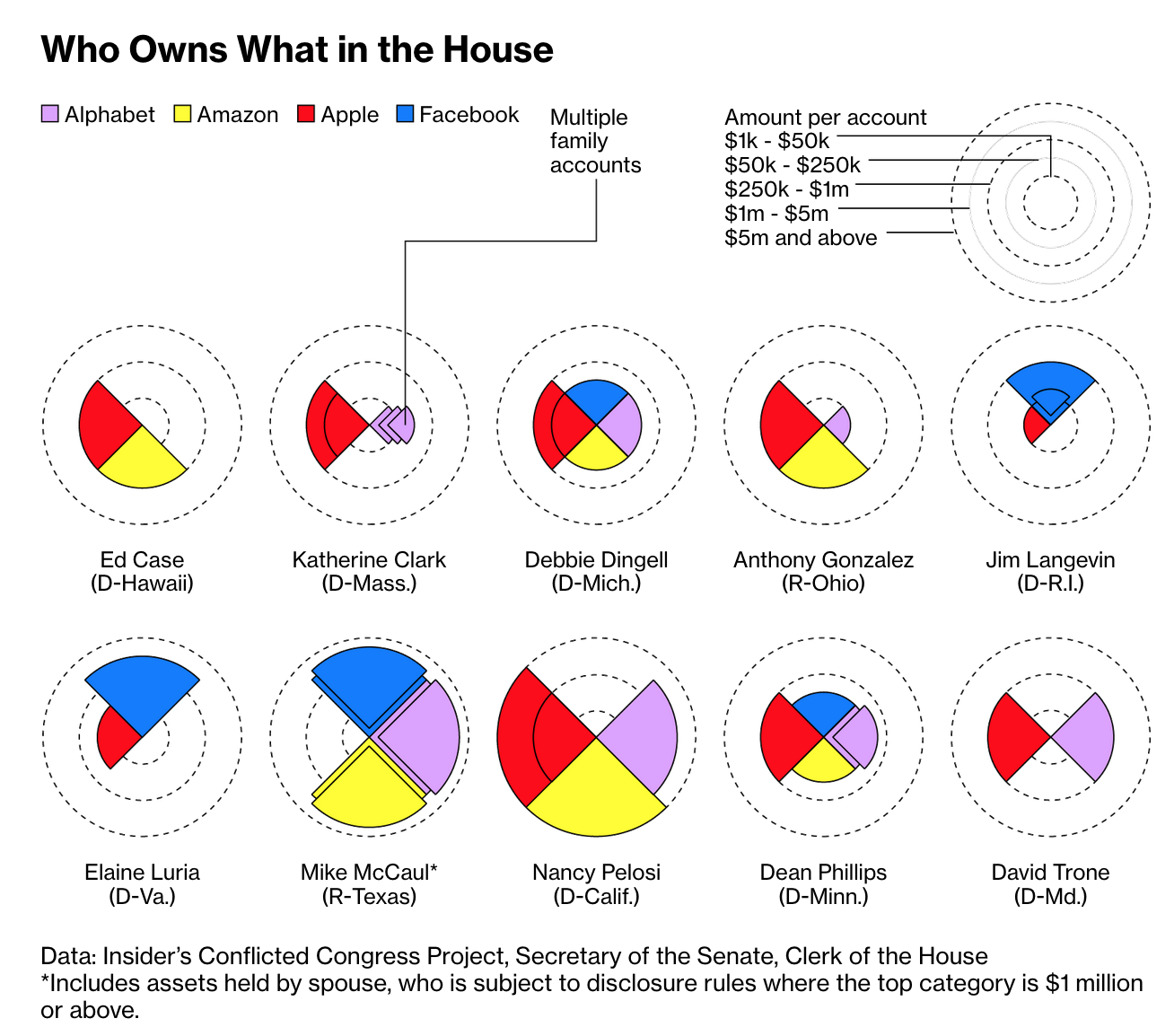

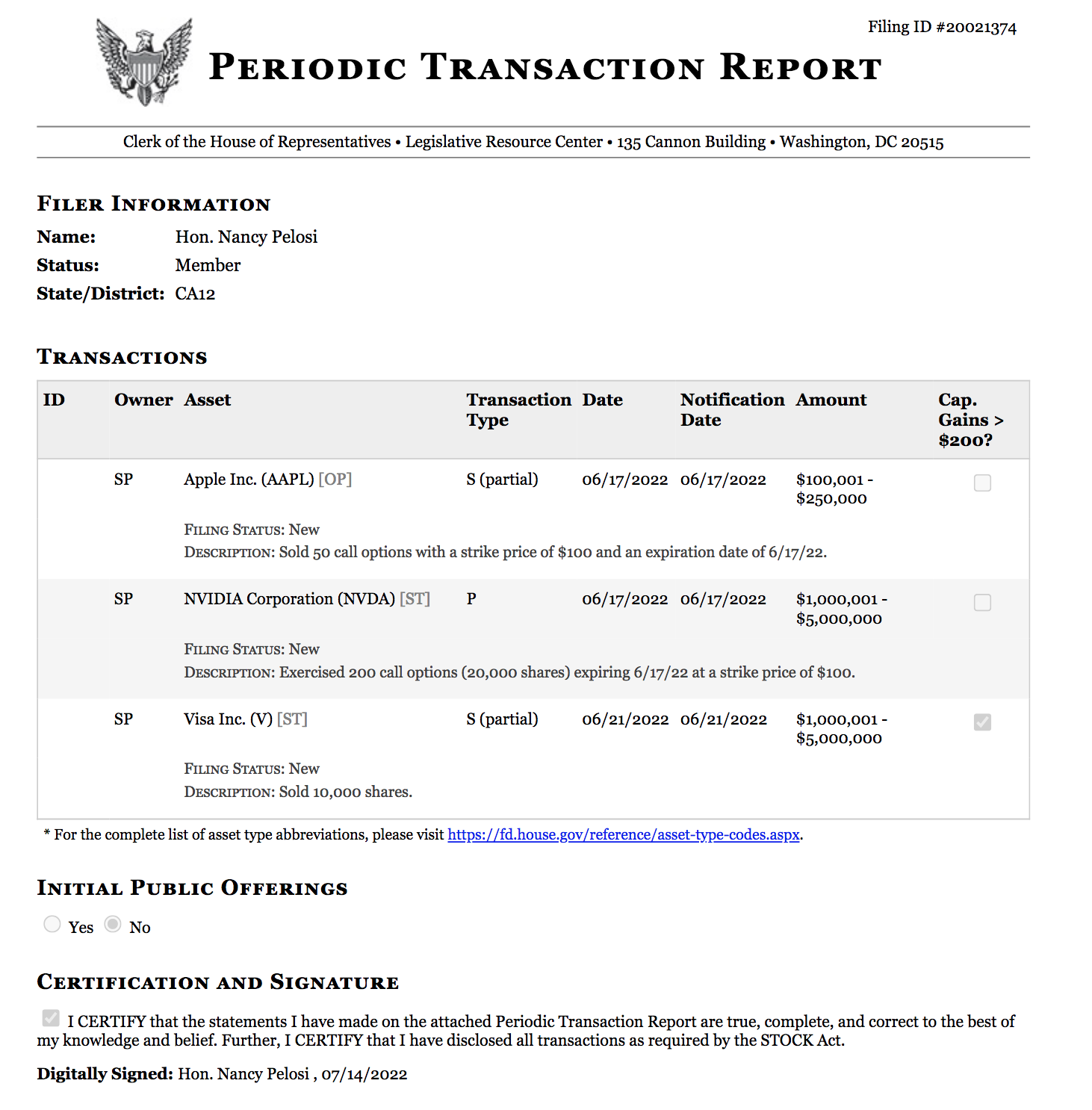

Pelosi’s Husband Locked In $5.3 Million From Alphabet Options

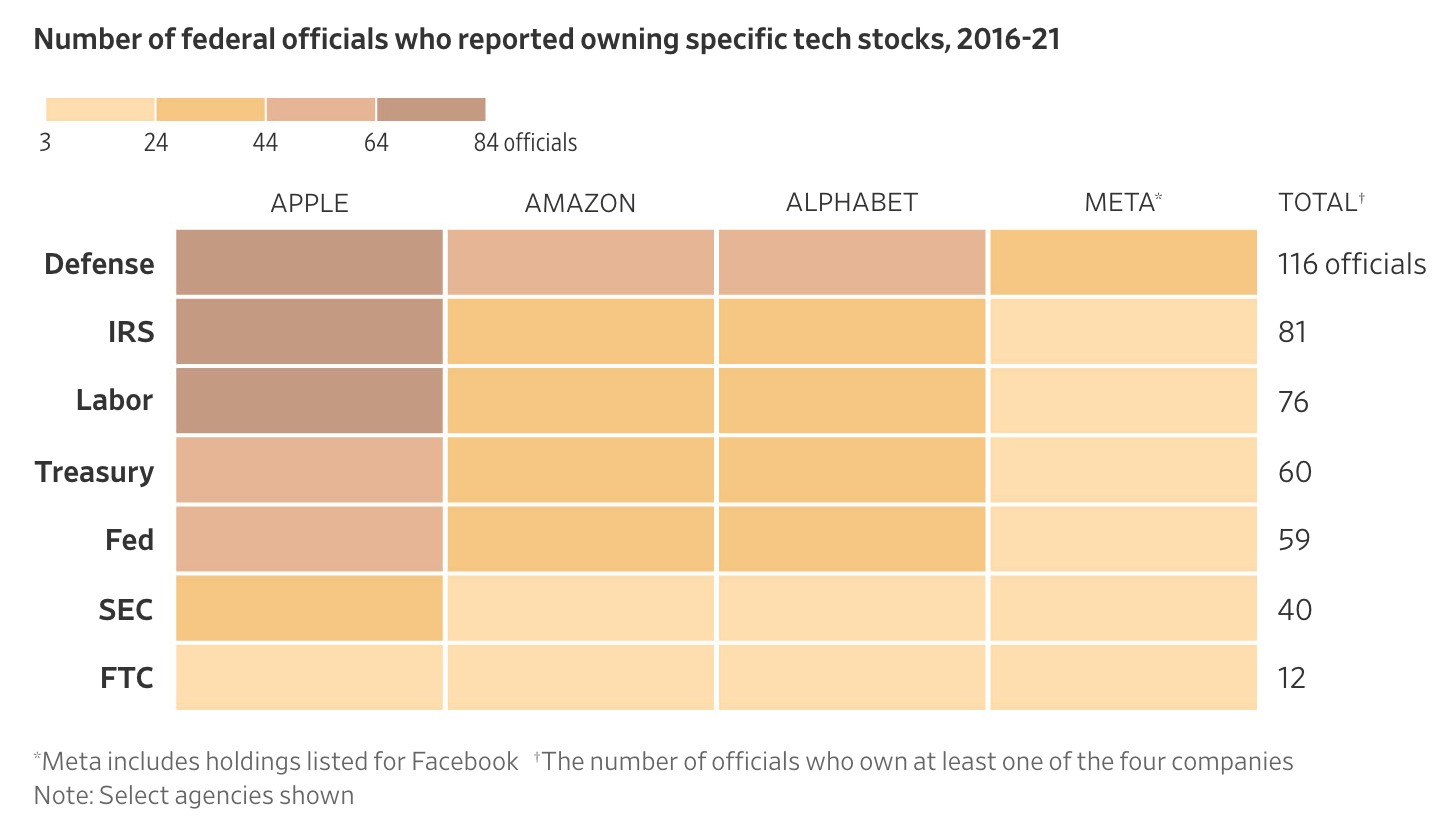

Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s husband, Paul Pelosi, won big on Alphabet Inc. stock and added bets on Amazon.com Inc. and Apple Inc. in the weeks leading up to the House Judiciary Committee’s vote on antitrust legislation that seeks to severely limit how these companies organize and offer their products.

In a financial disclosure signed by Nancy Pelosi July 2, her husband reported exercising call options to acquire 4,000 shares of Alphabet, the parent company of Google, at a strike price of $1,200. The trade netted him a $4.8 million gain, and it’s risen to $5.3 million since then as the shares have jumped.

The transaction was completed just a week before the House Judiciary Committee advanced six bipartisan antitrust bills, four of which take aim at Google, Amazon, Apple and Facebook Inc. Market reaction was muted, suggesting that investors don’t see the House proposals as a real threat to the companies.

Alphabet’s share price has increased 3.2% since the judiciary panel approved the legislation.In fact, Nancy Pelosi last month said she supports the Judiciary committee’s bipartisan effort to challenge the hold that big technology companies have over the internet economy, telling reporters that Congress is “not going to ignore the consolidation that has happened and the concern that exists on both sides of the aisle.” She said Congress’s responsibility is to “the consumer and competition.”

The six antitrust bills, especially the four that target a narrow set of companies, have a long road to become law. Pelosi’s top deputy, Majority Leader Steny Hoyer, said the legislation needs work before getting a vote in the full House. And the Senate presents an even tougher hurdle, where support from at least 10 Republicans is required to pass.

Paul Pelosi made his fortune in real estate and venture capital in the San Francisco area. His transactions are not suspected of violating any laws regarding members of Congress, their spouses and insider trading.

Disclosure reports must be filed within 30 days that lawmakers are aware of a transaction, or no more than 45 days after the transaction took place, according to House guidelines.

Paul Pelosi on May 21 also bought 20 call options for Amazon with a strike price of $3,000, expiring in June 2022, suggesting that he expects the online retailer to continue its gains. He also bet on Apple, purchasing 50 call options with the same expiration date and a strike price of $100.

“The speaker has no involvement or prior knowledge of these transactions,” her spokesman Drew Hammill said in an emailed statement on Wednesday, adding that Speaker Pelosi doesn’t own any stock.

Updated: 8-11-2021

Executive Stock Sales Are Under Scrutiny. Here’s What Regulators Are Interested In

10b5-1 plans allow executives to create schedules for buying and selling shares in the future, but they can be modified without disclosure.

Securities regulators are rethinking rules on popular plans that let corporate executives sell stock without violating insider-trading provisions.

The plans—known as 10b5-1 plans—allow executives to create schedules for buying and selling shares in the future. In theory, a predetermined sale, even if it comes at a fortuitous time, wouldn’t be based on inside information.

But years of research has shown that the reality is more complicated: Executives might establish a plan to sell shares that very day. Executives could set up a raft of plans to sell on different days, then cancel most of them. They can modify plans without disclosing what they are doing.

Securities and Exchange Commission Chairman Gary Gensler has expressed skepticism about the plans and in June asked the commission’s staff to recommend changes that would curb abuses.

Lawmakers called for changes last year after pharmaceutical executives developing Covid-19 vaccines sold $500 million worth of shares; many of the sales came under 10b5-1 plans that were modified after vaccine trials began. The companies say the trades followed rules for 10b5-1 plans, and no one has been accused of wrongdoing.

The plans are wildly popular: They accounted for 61% of all insider trades during 2020, up from 30% in 2004, according to data from InsiderScore, a research service tracking executive-trading data.

“The original intent was to create a safe harbor so people who want to follow the rules have a clear way to do that, but there may be a need to further strengthen those rules,” said Priya Huskins, partner and senior vice president at insurance brokerage Woodruff Sawyer & Co. who advises clients on corporate-governance issues including 10b5-1 plans.

Here Are Four Areas Likely To Draw Regulators’ Attention:

No Waiting Around

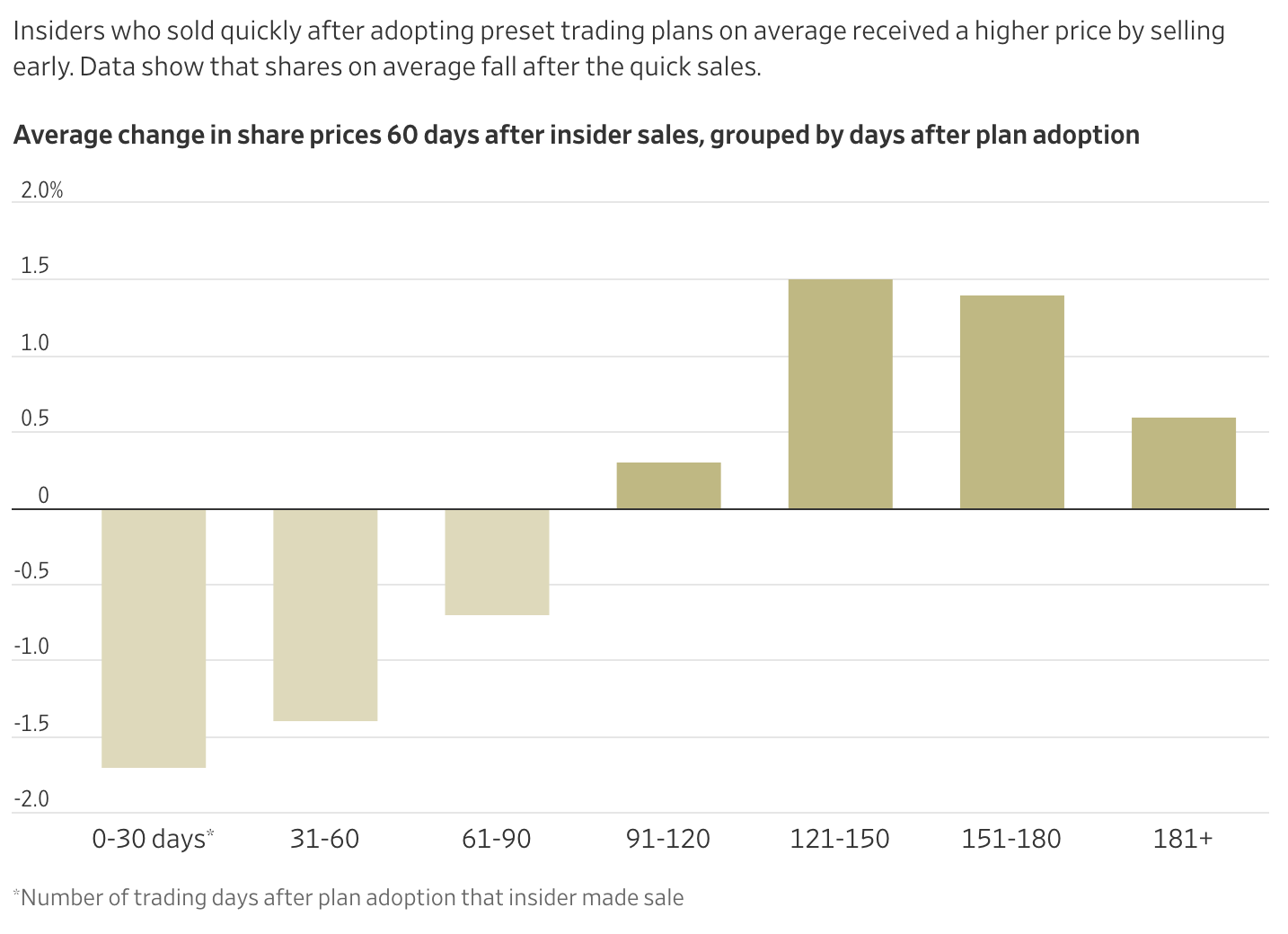

Under the current rules, an executive can trade the same day a plan is adopted. Trades that occurred within 60 days of the plan’s establishment were more likely to avoid significant losses and to have come ahead of stock-price declines, according to a January study of more than 20,000 plans by researchers from Stanford University, the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Washington. After 60 days, the advantages disappeared.

“I worry that some bad actors could perceive this as a loophole to participate in insider trading,” said Mr. Gensler in early June during an Investor Advisory Committee meeting.

He said he supports proposals to establish a four-to-six month window between establishing a plan and executing a trade.

Nearly 50% of all 10b5-1 sales since 2004 occurred within 60 days of an insider’s establishing a plan, according to data from InsiderScore.

Charles Schwab Corp.’s stock was trading at more than twice its pandemic low in late May when Chief Financial Officer Peter Crawford established a plan to sell shares; eight days later he sold more than $642,000 worth of shares near the all-time high, according InsiderScore data.

In July, the company revealed an SEC investigation into disclosures related to its robo-advisory service; the shares fell 5% a week after the announcement. Mr. Crawford hasn’t been accused of wrongdoing. The trade was executed as part of a broader 10b5-1 plan and adheres to all applicable regulations, a company spokesman said. Mr. Crawford declined to comment.

Cancel Anytime

Current rules allow executives to cancel plans even when they have nonpublic market-moving information. For instance, an executive who has a plan scheduled to sell shares on Sept. 1 could cancel that plan knowing that good news is coming on Sept. 2.

“This seems upside-down to me,” Mr. Gensler said. “It also may undermine investor confidence.” The SEC is reviewing options to limit cancellations.

Insiders aren’t required to disclose when a plan is canceled, so researchers have been unable to study the extent of terminated plans. Just 0.44% of plans since 2004 included details about a termination, according to InsiderScore data.

Darren Lampert, chief executive of cannabis-equipment seller GrowGeneration Corp., established a 10b5-1 plan in September 2019 that executed a series of transactions while the stock traded for less than an average of $6 through last August.

The plan was terminated after selling 70% of its anticipated 750,000 shares two days after the company said it would take legal action against a short seller that published a report about GrowGeneration’s management team.

After the presidential election, shares of cannabis companies rallied and GrowGeneration’s stock price rose nearly 300% to $35 between August 2020 and the end of November 2020.

Mr. Lampert’s next transactions were made without a plan days after earnings were announced, selling for as much as $31 a share at the end of November, according to InsiderScore data. GrowGeneration declined to comment. Mr. Lampert couldn’t be reached for comment; the company’s president declined to comment.

Single Trades

Many 10b5-1 plans steadily sell shares, whether the stock is up or down. Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, for example, has sold consistent volumes of shares at regular intervals since at least August 2019, according to InsiderScore data.

“Those plans that are selling routine amounts of shares every month over multiple years; that’s what the plan was intended for, to sell shares slowly over time,” said Daniel Taylor, an accounting professor who runs the Forensic Analytics Lab at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School and one of the authors of the January study of trading under plans.

But about a third of plans since 2004 involve just a single trade, according to InsiderScore data. (Because documentation is scant, researchers can’t differentiate between plans that intended to execute a single trade and those that planned for multiple trades but were terminated after the first sale.)

Single-trade plans outperformed multi-trade plans regardless of the timing, according to Mr. Taylor’s research. “When it’s a single-trade plan, it’s abusive,” he says.

Another twist: Insiders can also adopt a variety of plans with different strategies and then cancel those with unfavorable trades before they are executed. Mr. Gensler is considering limits on how many plans can be established at once.

Mandatory Disclosure

Insiders aren’t required to tell the SEC about modifications to 10b5-1 plans, which could include changing the volume, frequency and price targets of trades.

Since 2004, voluntary filings indicated that just 2.2% of nearly 34,000 plans were modified, according to InsiderScore data. Even when amendments are disclosed, there are seldom details about what changed.

Mr. Gensler isn’t the first SEC official calling for additional disclosures; a 2002 proposal would have required public companies to report each executives’ adoption, modification and termination of a plan. Some elements of the proposal were adopted by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act that year, but requirements to disclose modifications were abandoned.

“Disclosures are important because it helps facilitate an outside learning,” said Alan Jagolinzer, a professor of financial accounting at the University of Cambridge who has studied 10b5-1 plans. “We really don’t know how people utilize these plans because we see only the ones we see so it’s really hard to understand the outliers.”

Updated: 9-29-2021

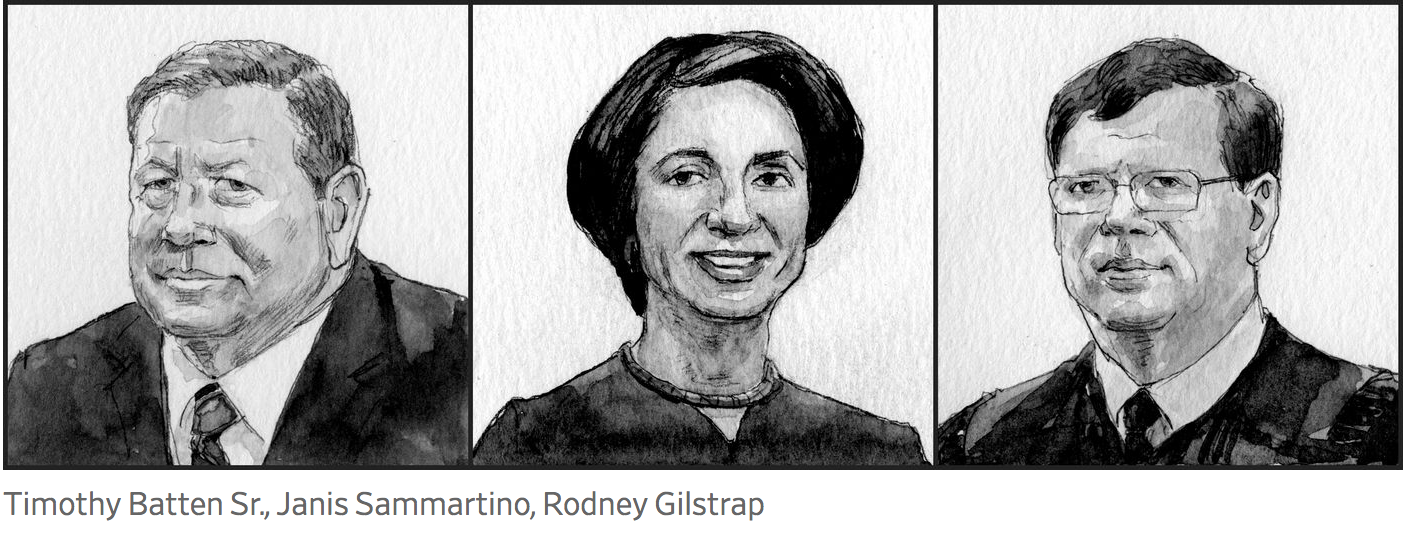

Judge Rodney Gilstrap Sets An Unwanted Record: Most Cases With Financial Conflicts

The patent-law expert took on 138 cases involving companies in which he or his spouse had a financial interest, a Wall Street Journal investigation found.

No federal judge in America has heard more patent-infringement lawsuits in the past decade than Rodney Gilstrap, who presides over a small courthouse in Marshall, Texas.

He also holds another record: Judge Gilstrap has taken on 138 cases since 2011 that involved companies in which he or a family member had a financial interest, more than any other federal judge, a Wall Street Journal investigation shows.

The companies included Microsoft Corp. (53 cases), Walmart Inc. (36 cases), Target Corp. (25 cases) and International Business Machines Corp. (9 cases).

A 1974 federal law requires judges to disqualify themselves from cases if they, their spouse or minor children hold a financial interest in a plaintiff or defendant, including the interest of a beneficiary in assets held by a trust.

The Journal investigation, which compared judges’ financial-disclosure forms against their court dockets, found that 131 federal judges violated this law from 2010 to 2018, in a total of 685 cases. Judge Gilstrap had several dozen more violations than the runner-up, Judge Janis Sammartino of California, who heard 54 cases involving companies held in her family’s trusts. She has since directed court clerks to inform the parties in most of the cases that she should have recused herself.

Judge Gilstrap, the chief judge for the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas, also disclosed one of the largest holdings in a conflicted company. He oversaw a patent-infringement case against a Walt Disney Co. unit while he or his wife reported holding between $100,001 and $250,000 of Disney stock. The plaintiff later withdrew its claim.

The 64-year-old Judge Gilstrap, one of America’s most prominent district judges, said he believed he didn’t need to recuse himself from some cases because they required little or no action on his part, and in other cases because the stocks were in a trust created for his wife without her stock-picking input. Legal-ethics experts disagree on both counts.

Judge Gilstrap declined interview requests. “I take my obligations related to potential conflicts/recusals seriously,” he said in one of seven emails to the Journal. “Throughout my judicial career, I have endeavored to comply with all such obligations, and I will continue to do so.”

Beyond violating law and ethics, the judges’ handling of lawsuits filed by and against companies in which they have financial interests threatens the federal courts’ hard-earned and crucial reputation for fairness, impartiality and objectivity.

Federal district judges have considerable discretion on matters of fact finding and other pretrial issues, and this can be especially important in patent litigation, a complex area of law. “The more important questions in any given patent case are the small discretionary, often procedural questions that the judge resolves before trial,” said Paul Gugliuzza, a law professor at Temple University.

Friends and other lawyers said they couldn’t imagine that Judge Gilstrap would ever be swayed by his or his family’s investments in making court rulings. “That man is as pure as the driven snow in terms of his ethics and personal responsibility,” said Brad Toben, the dean of Baylor University Law School and a longtime friend of the judge.

An unusually large role in patent litigation has made the Eastern District of Texas a lightning rod for criticism from some academics, corporations and think tanks.

These critics say its rules encourage patent holders to bring suits there because they are dispatched swiftly, often with quick settlement payouts to the plaintiffs. A 2016 article in the Southern California Law Review described how it said the court engaged in “forum selling,” a pejorative twist on “forum shopping,” the practice of lawyers seeking out friendly legal venues.

Some have lauded the court’s efforts to cater to patent litigants. A 2011 article in Southern Methodist University’s Science and Technology Law Review said the patent rules in East Texas “provide structure and a default schedule for the efficient, effective, and more predictable administration of patent cases.”

It is in patent suits where 85% of Judge Gilstrap’s recusal violations identified by the Journal occurred. In one, a McKinney, Texas-based company called Biscotti Inc. alleged that Microsoft’s Xbox One services infringed a patent covering live video-chat capabilities. A jury found in Microsoft’s favor in 2017.

Biscotti sought a new trial, citing numerous reasons, including an assertion that a video shown to the jury about videoconferencing calls violated evidentiary rules.

“The video does not present the sort of prejudice that would justify a new trial,” Judge Gilstrap said in rejecting Biscotti’s claims in 2018. “A plethora of other evidence in this record supports the jury’s verdict in this regard.”

For most of the nearly five years he oversaw the case, Judge Gilstrap’s disclosure forms listed between $15,001 and $50,000 of Microsoft stock.

In another instance, Judge Gilstrap took unusually strong action in a 2015 case that he shouldn’t have overseen because of stock held in his wife’s trust.

A firm called Iris Connex LLC sued Microsoft and 17 other technology companies alleging that their computer and smartphone devices infringed its patent for videoconferencing. In a 2016 ruling, Judge Gilstrap said that “no reasonable juror could find the accused camera system” with fixed cameras violated a patent held by the plaintiff that called for a movable camera.

The judge granted summary judgment, though the defendants hadn’t requested it. In doing so, he cited court precedent that said disposing of the claims at such an early point in the infringement case was highly unusual “but entirely appropriate at an early stage in a case where…the issues are cut and dry.”

In a later ruling, Judge Gilstrap also called Iris Connex’s lawsuit “exceptionally bad,” said the company was a shell meant to insulate the true owner of the patent against sanctions for filing frivolous cases, and ordered him to pay attorneys’ fees and expenses to one of the defendants.

Lawyers for Iris Connex and a spokesman for Microsoft declined to comment.

Judge Gilstrap said he removes himself from cases involving plaintiffs or defendants in which he or his wife hold stock—but not when those stocks are held in a trust created for his wife and her descendants.

Judge Gilstrap said that a trustee makes investment decisions for the trust and holds legal title to its assets and that the trust will continue to exist after his wife’s death.

Judge Gilstrap said he checked the trust’s characteristics against ethics guidance provided to other federal judges and believes that “its structure, the limitations it imposes, and the Trustee’s discretion place it in a category of trusts which would not require recusal.”

Legal experts told the Journal that Judge Gilstrap’s wife has an interest in the trust’s stocks, even if she doesn’t hold legal title to them.

Federal law defines a “financial interest” in a party as either a “legal or equitable interest,” such as a beneficiary’s interest in a trust.

“The judge must recuse if the trust for the spouse has even one share of stock in a party,” said Stephen Gillers, a New York University law professor and author of a judicial ethics casebook, who reviewed the filings for the Journal. “It does not matter that the spouse or child have no say in the investment choices.”

Investments in his wife’s trust should be disclosed if she either is the legal owner of the trust or has an equitable interest, said Ben Johnson, a law professor at Pennsylvania State University, who published research on recusal failures among district judges. “He would have to recuse.”

Judge Gilstrap’s financial disclosure forms make no distinction between the trust’s assets and stocks the judge and his wife hold in other investment accounts.

In emailed statements, he declined to provide an accounting of the stocks in the trust but confirmed that Microsoft was among them, reiterating that he believed he had no duty to recuse himself in cases involving the company.

Judge Gilstrap also initially said he had no duty to recuse himself from some cases involving parties in which his family’s other investment accounts held stock because the cases identified by the Journal were handled by a magistrate judge or required only “ministerial” actions by Judge Gilstrap.

After the Journal contacted him, he sought counsel from the federal judiciary’s ethics committee. The panel said he was mistaken.

A Sept. 2 opinion by the committee, provided to the Journal by Judge Gilstrap, said the Code of Conduct for U.S. Judges “requires recusal when a judge has a financial conflict, regardless of the substance of the judge’s actual involvement in the case,” and “encompasses a situation where the Clerk’s Office assigns you a case, even where you do not act.”

In sharing the opinion with the Journal, Judge Gilstrap said he would follow the panel’s guidance. “In hindsight and considering the attached opinion from the Committee, I now understand that, despite my lack of any involvement or action, such cases result in a need for me to recuse,” he said.

He declined to say whether he sought an opinion from the committee on whether he was required to recuse in connection with his wife’s trust.

Court dockets in the cases identified by the Journal give no indication that Judge Gilstrap or the court clerk has notified parties that he held a disqualifying interest while assigned to the cases.

On Tuesday, another federal judge notified by the Journal about recusal violations directed a court clerk to make public alerts to parties in 16 lawsuits saying he shouldn’t have heard the cases. That brought to 57 the number of judges who have told clerks to issue similar court notices, in 345 lawsuits.

Judge Gilstrap joined the federal bench in 2011, nominated by former President Barack Obama and recommended by two Republican senators from Texas. “He has earned the support of people of all political stripes in East Texas and around our great state,” Sen. John Cornyn said at the confirmation hearing.

When nominated, he reported that he or his family owned a total of nearly $1.8 million in shares of more than three dozen companies. In a more recent accounting, his 2018 disclosure form, Judge Gilstrap reported holding $3.7 million in stocks, among total assets of more than $8 million.

The shares he disclosed owning when nominated included $16,521 of Microsoft, $6,915 of JPMorgan Chase & Co. and $1,756 of Cisco Systems Inc. Within days of his confirmation, his docket filled with more than 100 cases, including suits that named Microsoft, JPMorgan and Cisco as parties.

By the end of the year, he had more than a dozen cases that involved companies in which he or his wife owned stock, the Journal found.

Mr. Gilstrap faced no questions about his investments at his confirmation hearing. But senators asked him about “patent-troll” litigation, a derisive term for suits by plaintiffs—often firms that make no products but own patents—to enforce rights against alleged infringers far beyond the patents’ value.

He vowed to be fair. “I’ve heard it said that to be an effective district judge, you have to be willing to disappoint your friends and astound and please your detractors sometimes,” he said at the hearing.

Judge Gilstrap is known around Marshall for meeting with students for civics lessons, singing in a church choir and handing out jars of homemade honey he has branded “Sweet Justice.”

A magna cum laude graduate of Baylor with a degree in religion, Mr. Gilstrap went to Baylor Law School before starting to practice law in Marshall. In 1984 he co-founded a firm there specializing in intellectual-property and patent law.

Court rules at the time allowed plaintiffs to file patent-infringement suits anywhere the defendant’s product was sold. When Dallas-based Texas Instruments sued competitors based in Asia to defend its semiconductor patents In the late 1980s, TI’s lawyers brought the cases not in Dallas but in Marshall, which had acquired a reputation for having juries sympathetic to plaintiffs and where suits could go to trial quickly.

A series of judges in the Eastern District of Texas adopted local rules that promised a “rocket docket” for patent cases. In a patent case before the U.S. Supreme Court in 2006, when an attorney complained of a pro-plaintiff bent at the court in Marshall, Justice Antonin Scalia referred to it as being among “renegade jurisdictions.”

“Why Do Patent Trolls Go to Texas? It’s Not for the BBQ,” the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a libertarian digital-rights group that opposes patent trolls, said on its website in 2014. The pro-defendant American Tort Reform Association in 2016 deemed the district among “judicial hellholes” because of its plaintiff-friendly reputation.

The Marshall community benefited from the local court’s being a center of patent litigation. Law firms needed hotels. Some companies opened local outlets to facilitate filing cases in the district.

“These attorneys are coming to small-town Texas for cases, often bringing a team of 20 lawyers,” said Prof. Gugliuzza of Temple, who has studied the court.

Before joining the federal bench, Judge Gilstrap served for a dozen years as the local Harrison County judge. That made him a top county politician, in a role concerned with local economic development as well as with the local court.

When tapped for a federal judgeship, he committed to taking on what by then was a bulky patent-suit caseload in Marshall. Since 2011, Judge Gilstrap has heard nearly 15% of the more than 47,800 patent cases filed in federal courts.

The assets reported by Judge Gilstrap and his family include companies that are typically defendants in patent-infringement suits.

Judge Gilstrap has retained or enhanced rules that made the local court attractive to plaintiffs’ lawyers seeking to enforce patents rights, who often seek to settle their suits quickly.

In the period before patent cases got to trial, Judge Gilstrap’s court has proved somewhat plaintiff-friendly, according to data analyzed for the Journal by Lex Machina, a legal analytics provider. Of 6,929 patent cases in front of Judge Gilstrap, 83% were resolved with a settlement before trial, compared with 69% of patent cases nationally since 2011.

Once litigants got to trial, however, the data analysis shows Judge Gilstrap’s rulings have favored defendants more often than in patent suits nationwide. Since 2011, he has found that defendants infringed patents in 34 cases and didn’t infringe in 35. Nationwide, judges have found infringement in 277 cases and none in 204 cases, according to Lex Machina, which also counted more patent suits handled by Judge Gilstrap than any other judge in the past decade.

Judge Gilstrap didn’t respond to requests for comment on these findings.

The tort-reform association said that in 2015, Judge Gilstrap threw out 168 suits filed by what the association labeled “a serial patent troll” that sought small settlements from numerous companies.

Over the years, Judge Gilstrap has championed the Eastern District of Texas on the legal-lecture circuit. In 2018, he made two dozen trips, many to speak at national and international conferences about patent litigation, paid for by the U.S. court system, bar associations and universities, his financial disclosure form shows. All this was permissible.

The Eastern District’s outsize role in patent litigation has eased since 2017, when the Supreme Court limited plaintiffs to bringing their suits where defendants have an established place of business. The district now is only the third-busiest, of 94 federal court districts, in patent cases. Judge Gilstrap, though, is still one of the busiest patent judges and has been since his earliest days on the federal bench.

Judge Gilstrap disqualified himself from a patent case weeks after his Senate confirmation in 2011, but he kept the case when it boomeranged back to him after brief stops in the courtrooms of two other judges.

In the suit, the plaintiff alleged its patent was infringed by a tool on the websites of McDonald’s Corp. and several other companies to help people find stores near them. Judge Gilstrap recused himself in January 2012 without explanation.

Asked recently about it, he said, “This was a long time ago, but I suspect the presence of McDonald’s Corp. (which I hold in a personal brokerage account) would have prompted” him to bow out.

The judge to whom the case was reassigned retired after about two months. The district court assigned it to another judge, but later took it away from that judge in a rebalancing of caseloads. The case landed on Judge Gilstrap’s docket again in January 2013. This time, he didn’t recuse himself.

McDonald’s was no longer a defendant, having settled. The plaintiff, however, had filed more suits alleging that various retailers, banks and big-box stores were infringing its patent. Judge Gilstrap consolidated these suits.

Of the more than two dozen companies that were by then parties, Judge Gilstrap’s disclosure forms showed investments in five: Home Depot Inc. and JPMorgan (each $15,001 to $50,000 worth) plus Microsoft, Target and Walmart (each up to $15,000).

Walmart and the plaintiff, LBS Innovations LLC, entered into an agreement to dismiss the claims against the retailer in September 2013. Judge Gilstrap discarded some of LBS’s infringement claims against the remaining companies in a January 2014 ruling. Settlements with Home Depot, JPMorgan, Microsoft and Target quickly followed.

Judge Gilstrap said the stocks in the five companies were assets of his wife’s trust and didn’t require his recusal.

Eric Buether, a lawyer who represented LBS in the case, said, “My experience is that he’s a fastidious judge who holds all parties and lawyers to obey the rules and [I] would not expect this to be anything other than an innocent error if there even were one.”

Mr. Buether has a trial in Judge Gilstrap’s court starting next week.

Updated: 9-30-2021

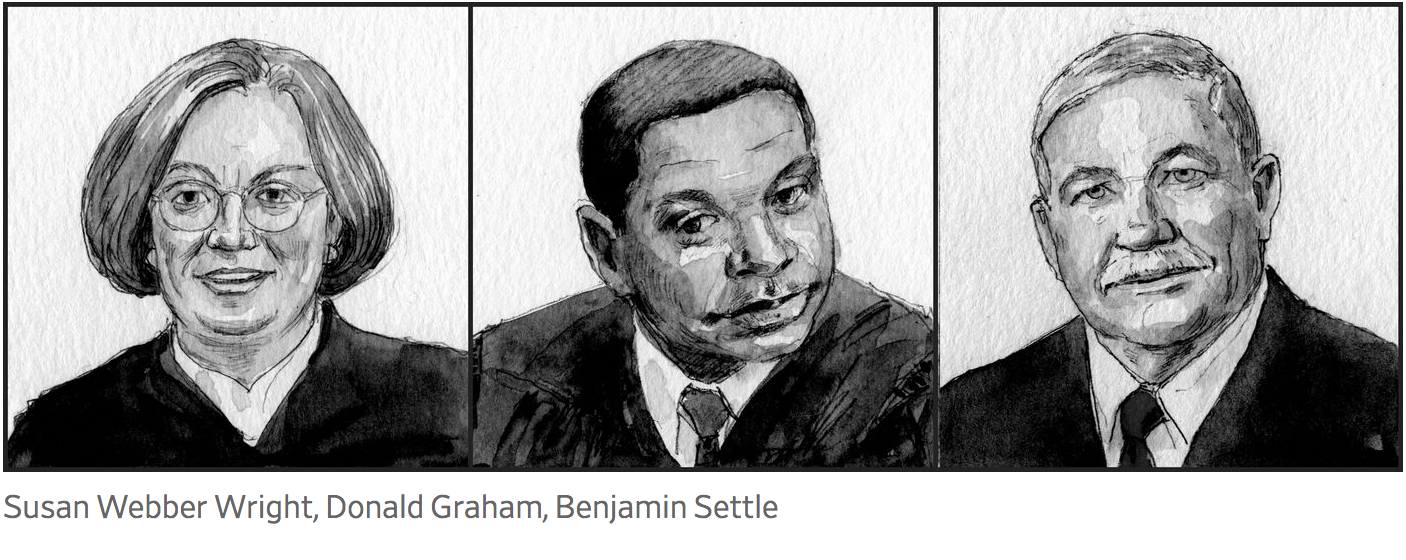

131 Federal Judges Broke The Law By Hearing Cases Where They Had A Financial Interest

The judges failed to recuse themselves from 685 lawsuits from 2010 to 2018 involving firms in which they or their family held shares, a Wall Street Journal investigation found.

More than 130 federal judges have violated U.S. law and judicial ethics by overseeing court cases involving companies in which they or their family owned stock.

A Wall Street Journal investigation found that judges have improperly failed to disqualify themselves from 685 court cases around the nation since 2010. The jurists were appointed by nearly every president from Lyndon Johnson to Donald Trump.

About two-thirds of federal district judges disclosed holdings of individual stocks, and nearly one of every five who did heard at least one case involving those stocks.

Alerted to the violations by the Journal, 56 of the judges have directed court clerks to notify parties in 329 lawsuits that they should have recused themselves. That means new judges might be assigned, potentially upending rulings.

When judges participated in such cases, about two-thirds of their rulings on motions that were contested came down in favor of their or their family’s financial interests.

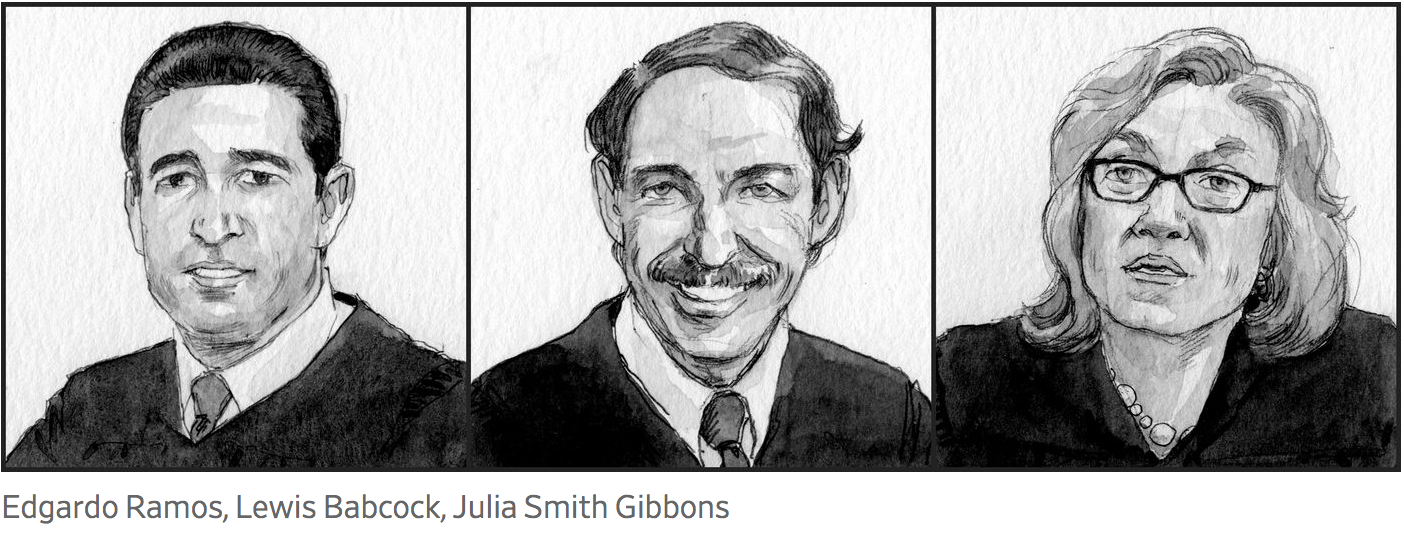

In New York, Judge Edgardo Ramos handled a suit between an Exxon Mobil Corp. unit and TIG Insurance Co. over a pollution claim while owning between $15,001 and $50,000 of Exxon stock, according to his financial disclosure form. He accepted an arbitration panel’s opinion that TIG should pay Exxon $25 million and added $8 million of interest to the tab.

In Colorado, Judge Lewis Babcock oversaw a case involving a Comcast Corp. subsidiary, ruling in its favor, while he or his family held between $15,001 and $50,000 of Comcast stock.

At an Ohio-based appeals court, Judge Julia Smith Gibbons wrote an opinion that favored Ford Motor Co. in a trademark dispute while her husband held stock in the auto maker. After she and the others on the three-judge appellate panel heard arguments but before they ruled, her husband’s financial adviser bought two chunks of Ford stock, each valued at up to $15,000, for his retirement account, according to her disclosure form.

The hundreds of recusal violations found by the Journal breach a bedrock principle of American jurisprudence: No one should be a judge of his or her own cause. Congress first laid out that principle in 1792 to guarantee litigants an impartial judge and reassure the public that courts could be trusted.

Judge Ramos, who oversaw the Exxon case, was unaware of his violation, said an official of the New York federal court, because his “recusal list”—a tally judges keep of parties they shouldn’t have in their courtrooms—listed only parent Exxon Mobil Corp. and not the unit, whose name includes the additional word “oil.” The official said the court conflict-screening software relied on exact matches.

The unit had informed the court at the outset of the case that it was a subsidiary of Exxon Mobil so Judge Ramos could “evaluate possible disqualification or recusal,” a court filing shows.

After the Journal contacted Judge Ramos, who was named to the court by former President Barack Obama, the court’s clerk notified the parties of his stockholding. TIG attorneys asked the court to set aside his ruling and send the case to a new judge because of “the inevitable appearance of partiality.” Exxon opposed assigning a new judge, calling that a “manifest unfairness, gross inefficiency, and waste of judicial resources.” An appellate court has put a hearing on hold until the district court decides what to do.

In the Comcast case, a Colorado couple asked Judge Babcock to issue an order blocking Comcast from accessing their property to install fiber-optic cable. Representing themselves in court, Andrew O’Connor and Mary Henry accused Comcast workers of bullying them, scaring their 10-year-old daughter and injuring their dog, Einstein, allegations the company denied.

Judge Babcock, who was appointed to the court by former President Ronald Reagan, ruled the couple had “continually blocked Comcast’s access to the easement.” He sent the case back to state court, as Comcast wanted.

“I dropped the ball,” Judge Babcock said when asked about the recusal violation. He blamed flawed internal procedures. “Thank you for helping me stay on my toes the way I’m supposed to,” he said. A Comcast spokeswoman declined to comment.

Mr. O’Connor, who settled his case in state court, said, “If you are a federal judge, you should not be holding individual stocks.”

Judge Gibbons from the Ford trademark case, appointed to the appeals court by former President George W. Bush, said she had mistakenly believed holdings in her husband’s retirement account didn’t require her recusal. She later directed the clerk of the Sixth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals to notify the parties of the violation and said that her husband has since told his financial adviser not to buy individual stocks.

“I regret my misunderstanding, but I assure you it was an honest one,” she said.

A spokesman for Ford said: “A fair and impartial judiciary is critical to the integrity of our legal system. In this case, the violation of Ford’s trademarks was clear.”

“I dropped the ball. Thank you for helping me stay on my toes the way I’m supposed to.”

Judge Lewis Babcock, When Asked About His Violations

Nothing bars judges from owning stocks, but federal law since 1974 has prohibited judges from hearing cases that involve a party in which they, their spouses or their minor children have a “legal or equitable interest, however small.” That law and the Judicial Conference of the U.S., which is the federal courts’ policy-making body, require judges to avoid even the appearance of a conflict. Although most lawsuits don’t directly affect a company’s stock price, the Supreme Court in 1988 said the law’s purpose is to promote confidence in the judiciary.

Conflict-of-interest rules are common for state and federal employees as well as for lawyers, journalists and corporate executives. U.S. government workers may not participate “personally and substantially” in matters in which they have a financial interest.

The Journal reviewed financial disclosure forms filed annually for 2010 through 2018 by roughly 700 federal judges who reported holding individual stocks of large companies, and then compared those holdings to tens of thousands of court dockets in civil cases. The same conflict rules apply to criminal cases, but large companies are rarely charged, and the Journal found no instances of judges holding shares of corporate criminal defendants in their courts.

It found that 129 federal district judges and two federal appellate judges had at least one case in which a stock they or their family owned was a plaintiff or defendant.

Judges’ stockholdings exceeded $15,000 in 173 cases and $50,000 in 21 of those cases, although under the law, the amount doesn’t matter.

The Journal found 61 judges or their families not only holding stocks in companies that were plaintiffs or defendants in the judges’ courts but also trading the stocks during cases.

Judges offered a variety of explanations for the violations. Some blamed court clerks. Some said their recusal lists had misspellings that foiled the conflict-screening software. Some pointed to trades that resulted in losses. Others said they had only nominal roles, such as confirming settlements or transferring cases to other courts, though there is no legal exemption for such work.

The ethics code for federal judges “requires recusal when a judge has a financial conflict, regardless of the substance of the judge’s actual involvement in the case,” the Judicial Conference’s Committee on Codes of Conduct wrote in a letter to a judge this month.

Some blamed court clerks. Some said their recusal lists had misspellings. Some pointed to trades that resulted in losses.

In response to the Journal’s findings, the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts said: “The Wall Street Journal’s report on instances where conflicts inadvertently were not identified before a case was resolved or transferred is troubling, and the Administrative Office is carefully reviewing the matter.”

It said the federal judiciary “takes very seriously its obligations to preclude any financial conflicts of interest” and has taken steps, such as conflict-screening software and ethics training, to prevent violations. “We have in place a number of safeguards and are looking for ways to improve,” the office said.

Chief Justice John Roberts, who heads the federal judiciary, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The nation’s roughly 600 full-time federal trial judges, supplemented by about 460 semiretired jurists called senior judges, wield enormous power. Holding lifetime appointments, they preside over hundreds of thousands of civil and criminal cases each year in 94 court districts.

They have soup-to-nuts control over all elements of their courtrooms, from pretrial process and trial to criminal pleas, judgments and sentencing. Judges have wide latitude for fact findings and evidentiary rulings, most of which can be overturned only for abuse of discretion, a high hurdle.

Violations of the 1974 law almost never become public. Judges’ financial disclosures aren’t online, are cumbersome to request and sometimes take years to access.

Judges are informed if anyone requests to see their disclosures, creating a disincentive for lawyers who might fear annoying judges in whose courtrooms they frequently appear.

Judges rarely make public the lists of companies on whose cases they shouldn’t work. When judges disqualify themselves from cases, they typically don’t disclose details. No judges in modern times have been removed from the federal bench solely for having a financial interest in a plaintiff or defendant that appeared in their courtroom.

“I just blew it. I regret any question that I’ve created an appearance of impropriety or a conflict of interest.”

— Judge Timothy Batten Sr., When Notified Of His Violations

The Journal analyzed data from the Free Law Project, a nonpartisan legal-research nonprofit that is planning to post judicial disclosure forms online. The findings amount to a pervasive disregard for the judicial conflict-of-interest laws, legal experts said.

A recusal violation in isolation could be viewed as an oversight, but the Journal’s investigation “raises a more systemic problem of judges chronically neglecting their duty to disqualify in such cases,” said Charles Geyh, a law professor at Indiana University, who specializes in judicial conduct, ethics and accountability.

The findings “are both surprising and disappointing,” said Timothy Batten Sr., chief judge of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Georgia and a member of the Committee on Codes of Conduct for the Judicial Conference of the U.S.

“I believe in the vast majority of these cases, it is an oversight and indolence,” he added.

Judge Batten himself owned shares of JPMorgan Chase & Co. while he heard 11 lawsuits involving the bank, most of which ended in the bank’s favor, the Journal’s analysis shows.

“I am mortified,” Judge Batten said in a phone interview when notified about his violations, which occurred in 2010 and 2011, before he joined the Codes of Conduct committee in 2019. “I had no idea that I had an interest in any of these companies in what was a most modest retirement account” managed by a broker.

“I just blew it. I regret any question that I’ve created or appearance of impropriety or a conflict of interest,” he said.

Judge Batten, appointed by former President George W. Bush, said he stopped investing in individual stocks in 2012 and moved his portfolio to mutual funds, which don’t require recusal, and has since closed the account.

The Journal analyzed cases to determine whether judges made rulings on contested motions, such as those seeking dismissal or summary judgment. Judges ruled on contested motions in 21% of the nearly 700 cases in question.

Those rulings favored the judges’ financial interests in 94 cases, went against the judges’ interest in 27 cases and had mixed outcomes in 24 cases.

Already, several parties on the losing side of the rulings have petitioned for a new judge to hear their cases after they were alerted to the violations identified by the Journal.

Several judges misunderstood the law, initially saying that they didn’t have to recuse themselves because their shares were held in accounts run by a money manager.

The ban on holding even a single share of a company while presiding in a case involving the firm means judges must be vigilant. The 1974 law requires judges to inform themselves about their own financial interests and make a “reasonable effort” to do the same for their spouses and any minor children. The Judicial Conference of the U.S. requires courts to use conflict-checking software to help identify cases where judges should bow out.

Judge Janis Sammartino of California traded in stocks of Bank of America Corp. , CVS Health Corp. , Deutsche Bank AG , Hartford Financial Services Group Inc., HSBC Holdings PLC, JPMorgan, Pfizer Inc., Public Storage, Wells Fargo & Co. and Microsoft Corp. while hearing 18 lawsuits involving one or more of those companies, the Journal found. In all, she heard 54 cases involving companies held in her family’s trusts.

In the Microsoft case, a Chicago man alleged the software giant violated the Telephone Consumer Protection Act by sending an unsolicited text about its Xbox gaming console to his mobile phone. He filed suit in 2011. One of Judge Sammartino’s family trusts bought Microsoft stock twice in 2012 and added three purchases in 2013.

The plaintiff’s lawyers sought in 2013 to turn the case into a class action involving 91,708 people who allegedly received the text messages. Microsoft said that it had received permission to send the texts but that records confirming this had been destroyed. Had a class been approved, the case could potentially have cost Microsoft more than $45 million, according to court filings by the plaintiff.

Judge Sammartino denied the class-action motion as well as Microsoft’s motion to dismiss the case. She ruled that the law permitted the plaintiff to seek damages of $500 for one alleged violation, potentially tripled. He appealed but settled before the appeal was heard. A spokesman for Microsoft declined to comment. One of the plaintiff’s lawyers also declined to comment.

Judge Sammartino, an appointee of former President George W. Bush, initially referred questions from the Journal to William Cracraft, a spokesman for the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

“She asked me to let you know” her stocks “are in a managed account, so she’s not seeing as how there could be a conflict,” Mr. Cracraft said. “She’s not inclined to discuss her private business with you since it is all in managed accounts, and she thinks that’s sufficient.”

An opinion by the Judicial Conference’s Committee on Codes of Conduct in 2013 confirmed that judges must bow out of cases involving stocks they own in accounts run by money managers.

Judge Sammartino later informed the court clerk’s office of the conflicts, and the office filed a letter notifying parties to the Microsoft case and other cases with violations identified by the Journal.

“Judge Sammartino was not aware of this financial interest at the time the case was pending,” the letter said. “The matter was brought to her attention after disposition of the case. Thus, the financial interest neither affected nor impacted her decisions in this case. However, the financial interest would have required recusal.”

Before the Journal contacted Judge Sammartino about her recusal violations, she disqualified herself in at least 10 other cases involving companies whose stocks were listed on her disclosure forms, a review of her cases shows.

Judge Rodney Gilstrap, chief of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas, had the largest number of conflicts in the Journal’s analysis: 138 cases assigned to him involving companies in which he or his wife held an interest.

Judge Gilstrap said he believed he didn’t need to recuse himself from some cases because they required little or no action on his part, and in other cases because the stocks were in a trust created for his wife. Legal-ethics experts disagreed on both counts.

“I take my obligations related to potential conflicts/recusals seriously,” he said in an email. “Throughout my judicial career, I have endeavored to comply with all such obligations, and I will continue to do so.”

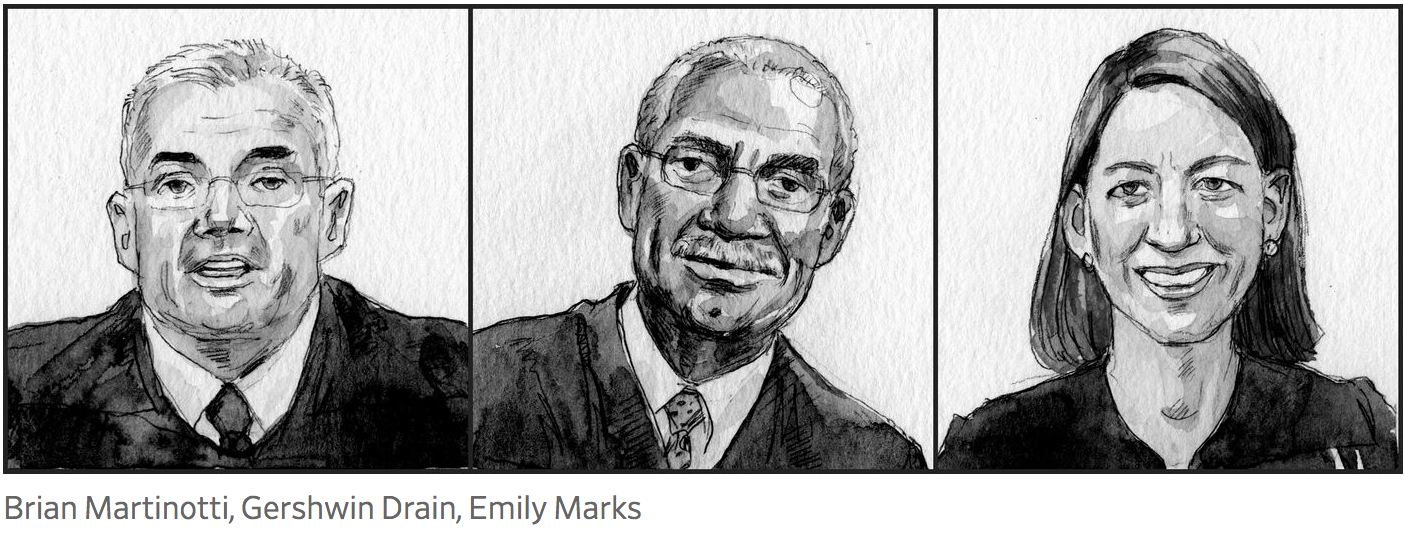

Judge Sammartino’s 54 conflicts were the second-most recusal violations. Brian Martinotti in New Jersey ranked third, handling 44 cases involving companies in which he had invested. Among his biggest holdings was Alphabet Inc., the parent of Google. He disclosed in 2016, 2017 and 2018 that he owned $15,001 to $50,000 of Alphabet shares.

In 2017, the judge threw out a lawsuit against Google alleging that videos on its YouTube unit falsely said the plaintiff was a sex offender, ruling that the Communications Decency Act let Google off the hook.

Judge Martinotti, an Obama appointee, didn’t respond to requests for comment, but after the Journal inquired, the district court clerk notified parties to 44 cases of Judge Martinotti’s stock ownership. His Alphabet holding didn’t affect the judge’s decisions but would have required recusal, the clerk wrote. A spokesman for Google declined to comment.

“I would like my case to be re-opened as Judge Brian R. Martinotti was unfairly biased and should have recused himself from my case,” the plaintiff, Nuwan Weerahandi, wrote in an August 2021 letter to the court, after receiving notice of Judge Martinotti’s violation.

The chief judge of the New Jersey federal court, Freda Wolfson, denied Mr. Weerahandi’s request on Sept. 2, saying the Communications Decency Act bars defamation-related claims against computer services such as Google.

“Importantly, in making this purely legal determination, Judge Martinotti did not engage in any factfinding that would bear on the credibility of any party, including you,” Judge Wolfson wrote.

In at least 18 instances, judges disqualified themselves over conflicts, only to have the case reassigned to a judge who also had a conflict but didn’t recuse.

In 2015, Judge Robert Cleland in Michigan, a George H.W. Bush appointee, bowed out of a suit by an injured motorist against insurer Allstate Corp. , whose stock the judge had been buying and selling that year.

The case was reassigned to Judge Gershwin Drain, who also owned Allstate shares. Judge Drain heard the case—and six others involving Allstate—and wrote a ruling denying a request by the motorist to move the dispute to state court. The case then settled on undisclosed terms.

Presented with his conflicts in 42 cases, Judge Drain, an Obama appointee, said he had added notices to the court’s public docket for each suit.

“I can say with absolute certainty that I never made any decision in favor of a company because I owned stock and was invested in that company,” Judge Drain said in an email. “To prevent any future issues, however, I have taken steps to review any new cases and if I am invested in any of the companies among the new cases that are assigned to me I will immediately recuse myself.” Allstate didn’t respond to requests for comment. A lawyer for the motorist declined to comment.

Frequent recusals can upset courts’ random drawing of judges for cases and lead to a smaller pool. In 20 federal districts, a third or more judges owned the same stock in the same year. In the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia in 2017, fully a third disclosed a Microsoft stock holding.

More than 340 federal appellate and trial judges reported holdings in Apple Inc. at some point from 2010 to 2018 and 300 in Microsoft. About 500 judges owned Bank of America, Citigroup Inc., JPMorgan or Wells Fargo shares at some point.

Those numbers reflect only stock ownership, not recusal violations. However, the Journal found 37 judges who owned a bank stock while improperly hearing a case involving that bank.

Judge Emily Marks bought Wells Fargo stock two weeks after she was assigned a Wells Fargo case, a conflict that now threatens to upset a ruling she made.

In the suit, Jacob Springer and Jeanetta Springer of Roanoke, Ala., acted as their own attorneys in challenging Wells Fargo’s foreclosure of Ms. Springer’s father’s home.

In court filings, they said her ailing father missed a mortgage payment three months before he died, after which his daughter, who inherited the home, made payments. Wells Fargo foreclosed, saying the Springers missed payments of about $4,100 on an outstanding mortgage of more than $80,000; they said they had missed just one $695 payment.

“This is outrageous. How am I supposed to know she owns stock in Wells Fargo?”

— Jacob Springer, When Told Of The Judge’s Violation In The Case He Lost

Judge Marks, chief judge of the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Alabama and an appointee of former President Donald Trump, was assigned the case in mid-August 2018. The judge bought Wells Fargo stock at the end of the month. In September, she adopted a magistrate judge’s recommendation to dismiss the Springers’ suit, a decision affirmed on appeal.

Judge Marks declined to comment. The court clerk told parties to the case that the judge had informed her of having owned the bank stock and directed the clerk to notify the parties. The clerk told them Judge Marks’s stock ownership didn’t affect her decisions in the case but would have required recusal.

Mr. Springer said, “This is outrageous. How am I supposed to know she owns stock in Wells Fargo?”

The Springers asked the court to reopen the case, saying in a filing that “a non-interested Judge” might have let them amend their pleadings. The court assigned a new judge to their suit in July. A spokesman for Wells Fargo declined to comment.

The nation’s 94 district courts are organized into 12 circuits, or regions. The Journal identified recusal violations in each region.

The U.S. Supreme Court wasn’t part of the Journal’s analysis. Nor did it include bankruptcy or magistrate judges.

Half of all federal trial and appellate judges in the Journal’s review disclosed minimum financial assets of $775,000 in 2018, while 31 reported a minimum of $10 million of assets. Some jurists joined the bench after lucrative careers in private practice.