Trump Concedes Economic Defeat Trumponomics Will Result In Negative Interest Rates (#GotBitcoin?)

Blaming ‘boneheads’ at the Fed, president says U.S. is missing out on opportunity. Trump Concedes Economic Defeat Trumponomics Will Result In Negative Interest Rates (#GotBitcoin?)

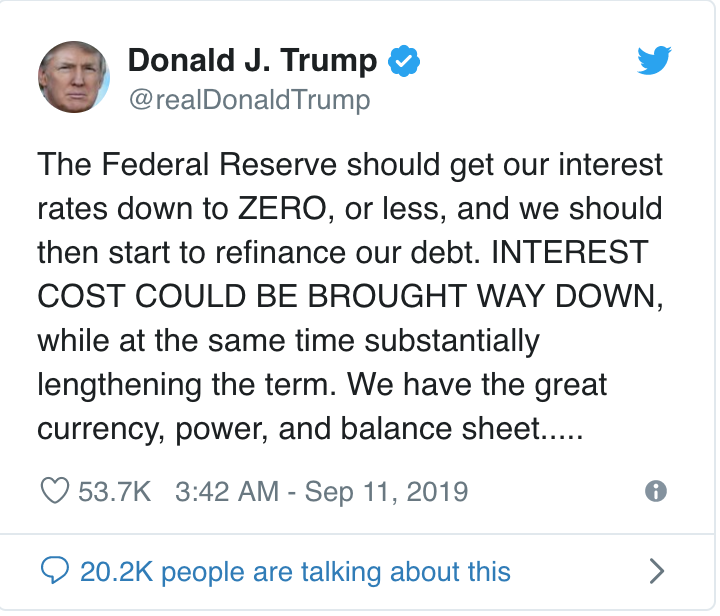

President Trump renewed his call for lower interest rates and his criticism of the Federal Reserve Wednesday, saying on Twitter that the Fed should reduce rates to “ZERO, or less.”

He said the U.S. should always be paying the lowest rate and complained that the “naivete” of Chairman Jerome Powell and the Fed means that this was a “once in a lifetime opportunity that we are missing because of ‘Boneheads.’”

A Fed spokeswoman declined to comment on the tweets.

After cutting their benchmark interest rate in July by a quarter percentage point, Fed officials are gearing up to cut rates again, likely by another quarter point, at their Sept. 17-18 policy meeting.

Mr. Powell, who has defended the Fed’s independence from political pressure, framed the July decision to lower the Fed’s benchmark short-term rate to a range between 2% and 2.25% as a “mid-cycle adjustment.”

The global growth and trade outlook has deteriorated since then amid an escalation in the trade war with China.

The comments by Mr. Trump mark the latest escalation of his unprecedented attack on the Fed and Mr. Powell, who the president picked for the post in 2017.

The president said last month that the Fed should cut its benchmark interest rate by at least a full percentage point and resume its crisis-era program of buying bonds to lower long-term borrowing costs. Such moves would typically be considered only when the economy faces a substantial downturn.

Wednesday’s comments are the first time Mr. Trump has called for rates below zero. In response to a reporter’s question several weeks ago, Mr. Trump said he didn’t want negative rates.

Yields in some countries including Germany, France and the Netherlands have fallen below zero already. On Tuesday, JPMorgan Chase & Co. Chief Executive James Dimon said the bank has begun discussing what fees and charges it could introduce if interest rates go to zero or lower. Even during the last recession, the Fed didn’t employ negative rates.

President Trump and White House officials have said they don’t believe the U.S. is headed toward a slowdown, but also have floated other ideas, such as tax cuts, to boost the economy.

A rate cut of the magnitude Mr. Trump is calling for hasn’t happened since the global financial crisis in late 2008.

In comments last week, Mr. Powell said the U.S. economy faced a favorable outlook despite significant risks from weaker global growth and trade uncertainty.

President Trump renewed his call for lower interest rates and his criticism of the Federal Reserve on Wednesday, by pressing for the central bank to cut short-term rates to “ZERO, or less,” negative rates that the U.S. avoided even after the 2008 financial crisis.

For weeks, Mr. Trump has pushed for lower rates to help cushion the economy against fears of a broader global slowdown. On Wednesday, he introduced a different argument for rate cuts by saying it would allow the U.S. to lock in lower interest rates for a longer period of time.

“We should then start to refinance our debt,” he wrote on Twitter, arguing it would reduce interest costs “while at the same time substantially lengthening the term.”

But some economists, including one of Mr. Trump’s former advisers, warned that his push for lower short-term interest rates might make it harder to achieve the stated goal of locking in lower rates, because it could send up long-term Treasury yields.

The tweets marked the latest escalation of Mr. Trump’s pressure on the Fed and attacks on Chairman Jerome Powell, whom the president picked for the post in 2017. Mr. Trump said the U.S. should always be paying the lowest rate and complained that the “naivete” of Mr. Powell and the Fed means that this was a “once in a lifetime opportunity that we are missing because of ‘Boneheads.’ ”

A Fed spokeswoman declined to comment on the tweets. Mr. Powell has previously defended the Fed’s tradition of independence from political pressure.

After cutting their benchmark interest rate in July by a quarter percentage point, Fed officials are gearing up to cut rates again, likely by another quarter point, at their Sept. 17-18 policy meeting.

Mr. Powell framed the July decision to lower the Fed’s benchmark short-term rate to a range between 2% and 2.25% as a “mid-cycle adjustment.” The global growth and trade outlook has deteriorated since then amid an escalation in Mr. Trump’s trade war with China.

Economists warn that pushing short-term interest rates to near zero could signal that Fed officials expect a much deeper economic downturn.

“That could have the unintended consequence of triggering a major drop in confidence in the economy that could precipitate a recession, which would have the opposite effect,” said Diane Swonk, chief economist at Grant Thornton.

Lowering rates all the way to zero now, when the economy is still on solid footing, could also leave the Fed without any ammunition if an actual recession hits, Ms. Swonk said.

Some economists were also skeptical that pushing interest rates to zero would actually lead to lower interest costs on government debt.

Mr. Trump has previously floated the idea of refinancing the U.S.’s nearly $17 trillion in publicly held debt, which has jumped in the wake of Republican tax cuts and bipartisan budget deals that boosted federal deficits.

“I would like to see the rates be low and pay amortization, pay off debt,” Mr. Trump said in an October 2018 interview with The Wall Street Journal, complaining that the Fed had made this difficult by raising rates several times in recent years.

Debt-servicing costs are one of the fastest growing drivers of federal spending: Interest payments have increased nearly 10% so far this fiscal year, totaling $497.2 billion through July, roughly $1.6 billion a day, according to the Treasury Department.

It isn’t exactly clear what Mr. Trump envisions. Sovereign debt is different from mortgage debt, and can’t be renegotiated to reduce monthly payments or pay debt off early. But the Treasury can replace maturing government securities with new, long-term debt at lower interest rates, which could bring down costs.

“The Treasury should start issuing debt in much longer terms,” said Stephen Moore, an economic adviser to Mr. Trump’s 2016 campaign who at one point was under consideration for a slot on the Fed board, in a Wall Street Journal op-ed last month. “This would lock in today’s low interest rates on the national debt for 10, 20, 30 years or perhaps even longer.”

Ernie Tedeschi, an economist at Evercore ISI, said such an idea makes sense, but it is something that the Treasury is already doing. The average length to maturity of publicly held federal debt has risen to 66 months, from 46 months at the height of the 2008 financial crisis.

The Treasury has also asked an advisory group to reconsider the potential benefits of issuing ultra-long bonds, as other countries have done.

Lowering the Fed’s benchmark federal-funds rate to zero wouldn’t automatically translate to lower interest rates on government debt, which is determined by bond markets, Mr. Tedeschi said. While short-term interest costs would likely fall, “it could be that the 10-year [Treasury note] goes up because markets are more confident in the Fed management of the economy,” he said, a shift that would lead to higher interest costs.

Paul Winfree, the director of the Heritage Foundation’s Roe Institute for Economic Policy Studies and a former budget adviser to Mr. Trump, said the president’s argument is “economically inaccurate.”

“Treasury has to offer interest rates that will attract buyers,” he said. “If all of a sudden we decide to roll over all of our debt, well, that will surely influence the interest rate on the debt. Like if all of a sudden every household in America decided to refinance.”

Mr. Trump said last month that the Fed should cut its benchmark interest rate by at least a full percentage point and resume its crisis-era program of buying bonds to lower long-term borrowing costs. Such moves would typically be considered only when the economy faces a substantial downturn.

Wednesday’s comments are the first time Mr. Trump has called for rates below zero. In response to a reporter’s question several weeks ago, Mr. Trump said he didn’t want negative rates.

Yields in some countries, including Germany, France and the Netherlands, have fallen below zero already. On Tuesday, JPMorgan Chase & Co. Chief Executive James Dimon said the bank has begun discussing what fees and charges it could introduce if interest rates go to zero or lower. Even during the last recession, the Fed didn’t employ negative rates.

Mr. Trump and White House officials have said they don’t believe the U.S. is headed toward a slowdown, but also have floated other ideas, such as tax cuts, to boost the economy.

A rate cut of the magnitude Mr. Trump is calling for hasn’t happened since the global financial crisis in late 2008.

In comments last week, Mr. Powell said the U.S. economy faced a favorable outlook despite significant risks from weaker global growth and trade uncertainty.

She echoes concern that low borrowing costs can contribute to asset bubbles, overreliance by companies and households on cheap debt.

Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester said Thursday there was a risk of financial imbalances developing in an environment of low interest rates and that the central bank had relatively few tools to address such issues outside of monetary policy.

She was referring to a concern among some officials and economists that low borrowing costs can contribute to asset bubbles, overreliance by companies and households on cheap debt and excessive risk-taking by economic actors.

“You have to recognize that, if you’re running very low interest rates, that you may be creating some financial imbalances that may come back to haunt you in the future,” Ms. Mester said on a panel at the Brookings Institution.

In theory, Ms. Mester said, authorities would be able to use so-called “macroprudential” mechanisms such as closer oversight and targeted regulations to safeguard against instability in the financial sector, rather than the blunt instrument of interest rates.

But, in practice, “that’s a hard thing to do because we don’t really have that many macro-prudential tools,” she said.

Ms. Mester reiterated the Federal Reserve’s general view that financial risks are manageable at the moment, notwithstanding “some issues” related to high levels of corporate debt and elevated pricing for commercial real estate.

She didn’t comment on the Fed’s current interest-rate policy.

Updated: 10-15-2019

Fed Paper Says Negative Rate Policy Can Provide Real Stimulus

U.S. might have benefited from a negative rate policy during financial crisis, San Francisco Fed paper says

Negative interest rates are a viable tool to provide stimulus to economies that need it, and the U.S. might have benefited from using it during the financial crisis, a new report from the San Francisco Fed said Tuesday.

“Analyzing financial market reactions to the introduction of negative interest rates shows that the entire yield curve for government bonds in those economies tends to shift lower,” writes bank economist Jens Christensen. “This suggests that negative rates may be an effective monetary policy tool to help ease financial conditions.”

Negative short-term term rate policies are controversial and thus far haven’t been tried in the U.S. But variations are in place in other nations.

In normal times, central banks seek to influence their respective economies through changes in positive short-term rate targets. Right now, the Fed’s target rate range is set between 1.75% and 2%.

But changes in how economies are structured, as well as demographic shifts and other factors, have created an environment where short-term rates are lower than they have historically been. That means when a central bank confronts trouble, it is more likely to lower rates to zero. In the U.S., during the financial crisis, that so-called zero lower bound was the stopping point for interest-rate policy. The Fed provided additional stimulus via purchases of long-term bonds and guidance about the future of rate policy.

Negative rates upend the normal system wherein lenders are compensated for risk by getting a positive return on their investment. With negative rates, borrowers get paid to take loans, rather than the other way around. Central banks pursue negative rates to induce those sitting on cash to put it to work, hoping that will boost activity, rather than see their holdings diminished by the negative rates. Rates under zero also help lower market-based borrowing costs.

The European Central Bank’s deposit facility rate now stands at minus 0.5%. The Bank of Japan also has a negative policy rate.

The San Francisco Fed paper looked at bond markets affected by the negative rate policies of the Danish National Bank, the ECB, the Swiss National Bank, the Swedish Riksbank and the Bank of Japan.

“The entire cross section of government bond yields tends to exhibit an immediate and persistent negative response to the introduction of this policy tool,” Mr. Christensen wrote. “Negative interest rates therefore appear to be a powerful monetary policy tool that could help ease financial conditions when interest rates would otherwise be stuck at zero as the perceived lower bound.”

The economist said the U.S. could have benefited from negative rates during the financial crisis. “Mildly negative U.S. policy rates from 2009 to 2011 could have supported higher economic growth and eventually pushed up inflation closer to the Federal Reserve’s target,” he wrote.

So far this year, the Fed has lowered rates twice and is widely expected to do it again at the end of the month. The already low level of the central bank’s target-rate range has reintroduced speculation about possible negative rates as a tool for the Fed in the future. But top central bankers seem remain as reluctant as ever on that question.

“If we were to find ourselves at some future date again at the effective lower bound—again, not something we are expecting—then I think we would look at using large-scale asset purchases and forward guidance” as the main sources of stimulus, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said at his press conference after the Fed’s September policy meeting. “I do not think we’d be looking at using negative rates.”

But that isn’t a universally held view. In an interview with the Wall Street Journal on Thursday, Minneapolis Fed leader Neel Kashkari said “we’d have to consider negative rates, if we were in the same position as Europe.” He added that when it comes to negative rate policy, “nobody could ever completely rule it out. But I don’t think it would be one of the first things we do.”

Updated: 10-22-2019

Fiat-To-Crypto ‘Carry Trade’ May Tempt Traders Tired of Negative Interest Rates

With the era of negative interest rates well and truly here, return-hungry investors may increasingly borrow in low-interest fiat currencies and invest in higher-yielding cryptocurrency accounts.

“The fiat-BTC carry trade is the next step in bitcoin growth,” tweeted popular bitcoin quant investor @100trillionUSD on Oct. 10.

A carry trade is a strategy where a trader uses a low-yielding currency to fund a high-yielding investment.

For instance, the yen carry trade was popular in 2004-2008 when the Federal Reserve hiked rates from 1 percent to 5.25 percent and interest rates in Japan were stuck near 0.5 percent.

Investors borrowed in yen to fund dollar-denominated investments. As a result, the yen weakened by 20 percent against the U.S. dollar.

Currently, the carry trade in the FX markets is pretty much dead with almost every advanced nation having interest rates at or below zero.

But that situation bodes well for a new type of carry trade with a crypto twist.

Lucrative Lending…

On the lending side, crypto-asset platforms like Binance, Crypto.com, Celsius Network, BlockFi are paying interest rates on cryptocurrency deposits. They fund this with interest earned from credit lines extended to margin traders and hedgers.

The interest rates are subject to fluctuations, either modified by the platform operator or influenced by the supply-demand mechanics of users interacting with the platform.

For instance, the Bitfinex exchange pays an annual interest rate of 0.66 percent interest on bitcoin deposits and provides loans at 0.59 percent, according to CoinMarketCap’s new Interest tracker.

In a sense, Bitfinex is operating as a commercial bank by charging a higher rate on loans and paying relatively less on deposits. (Think of the old 3-6-3 rule: “borrow at 3 percent, lend at 6 percent, hit the golf course at 3” – except unlike a bank, crypto exchanges never close.)

While Bitfinex is offering 0.66 percent, other platforms are paying significantly higher interest rates on bitcoin deposits, as seen in the chart below.

One possible reason for the disparity is that like a demand deposit at a bank, Bitfinex allows customers to withdraw at any time, whereas other crypto platforms require the money to be locked up for a period for weeks or months. Crypto.com, for instance, is paying 6 percent, but deposits need to be maintained at least for 90 days.

Then again, BlockFi also allows withdrawals any time (it even removed an early withdrawal penalty, allowing one free withdrawal per month) and it is offering an annual interest rate of 6.20 percent.

Meanwhile, crypto lending provider Nexo is offering up to 8 percent yield on deposits of stablecoins DAI, USD Coin (USDC), Paxos Standard (PAX), TrueUSD (TUSD) and Tether (USDT). Stablecoins are cryptocurrencies whose value is pegged to a fiat currency like the U.S. dollar.

…and cheap borrowing

The annual interest rates paid by crypto lending platforms are significantly higher than the rates across the advanced world, as seen below.

Central banks in Europe and Japan are running a negative interest rate policy (NIRP), under which financial institutions are required to pay an interest rate for parking excess reserves with the central bank.

The Swiss National Bank, which introduced negative rates in 2015, currently has the lowest rate in the world at -0.75 percent. The Bank of Japan (BOJ) cut rates to -0.1 percent in January 2016 and has been running the negative interest rate policy ever since.

The yield of -0.12 percent seen on the 10-year Japanese government bond is the side effect of BOJ’s market-distorting policies.

Also, corporate debt yields have recently hit unprecedented lows. For instance, Toyota Finance Corp will be issuing three-year notes at an unprecedented low yield of 0.0000000091 percent, according to Bloomberg. It means a trader buying 1 billion yen of the bonds would not even make 1 yen on maturity.

The situation is somewhat better for investors in the U.S. and U.K., where the target short-term rates set by the central bank stand at 1.75 percent and 0.75 percent, respectively. The benchmark 10-year government bond yields, however, are significantly lower than the interest rates paid by the likes of Nexo and Celsius Network.

More importantly, central banks running NIRP are unlikely to normalize their policy anytime soon, given the bleak outlook for the global economy. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) recently slashed its 2019 global growth forecast to 6 percent – the lowest since 2008.

All-in-all, interest rates across the globe are low and could slide further, boosting the allure of high-yielding crypto deposits.

Halving Factor

Aside from the interest rate differential, there’s another reason borrowing fiat to buy bitcoin could pay off.

In May of next year, the amount of new bitcoin awarded to miners every 10 minutes or so will be cut in half for the third time in the cryptocurrency’s history. Historically, reward halvings have boded well for bitcoin’s price.

The next halving could reduce the amount of new bitcoin added to the market by $51 million per week at current prices, according to Alistair Milne, chief investment officer of Altana Digital Currency Fund.

As of writing, BTC is trading above $8,200, representing 120 percent gains on a year-to-date basis.

And, if the carry trade becomes popular, all else equal BTC should appreciate sharply against the USD, the way the greenback did against the Japanese Yen.

Updated: 10-25-2019

Stanford Prof: Crypto Will Rain on Banks’ Low-Interest Rate Parade

A professor at Stanford Graduate School of Business says cryptocurrencies will put an end to the windfall that banks currently enjoy from low-interest deposits.

In an Oct 24 interview for the university, Dean Witter Distinguished Professor of Finance Darrell Duffies said that one way or another, cryptocurrencies are likely to upend banks’ business model within the next decade.

Major Disruption Inevitable

Professor Duffie said the public should not be misled by the relatively still-low levels of adoption of decentralized cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin (BTC); nor should they take the pushback against Facebook’s Libra as the sign of a moratorium on major private initiatives.

“The future is coming, and it will be very disruptive to legacy banks that don’t get with the program,” he said.

Whether it in the form of a dollar-backed stablecoin, a Facebook product, or a central bank digital currency, the benefits of the digital asset model will likely mean that banks lose their access to lucrative low-interest deposits within ten years, he said, adding:

“New payment methods will trigger greater competition for deposits. If consumers have faster ways of paying their bills, and merchants can get faster access to their sales revenue without needing a bank, they won’t want to keep as much money in accounts that pay extremely low interest.”

As the report notes, consumers and businesses currently store around $14 trillion in deposits with United States banks alone that pay out an extremely low rate of interest on average.

Banks currently pay less than 0.1% interest on checking and savings accounts, and only a slightly higher rate on one-year certificates of deposit. Meanwhile, the amount banks receive from routine overnight loans has climbed from 0.3% in 2015 to over 2% in 2019.

Slow Adopters Will Fall By The Wayside

This dependence on deposit accounts to process payments by the vast majority of the population ensures huge profits for banks. In addition, banks charge high fees from credit card vendors — a cost that is mostly then passed on to the consumer.

Different models for future central bank digital currencies could also develop in ways that would bypass commercial banks for at least part of the payment process.

And if adoption is driven by the private sector — as with Libra, due to the unprecedented scale effects it has — it could have a huge impact on the status quo.

He argued that the current system is not sustainable and that technology, economics and public pressure will wrest control of the global payment system away from banks.

“The smartest banks will be on the front edge of this, but others will be reluctant to cannibalize their very profitable franchises,” he said. To those banks that are slow on the mark, he cautioned:

“The future is coming, and it’s not good.”

Updated: 11-26-2019

Powell Says Fed’s Rate Cuts Reflect More Bearish View of Economy

Central bank’s policy move based on trade uncertainty, global growth as well as shifting economic assessment, chairman says.

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell said the central bank cut interest rates this year in part because officials concluded the economy wasn’t as strong as anticipated when the Fed lifted rates last year.

The central bank signaled last month it was done cutting rates for now after making its third quarter-percentage-point reduction since July. Officials have said a slowdown in business investment and global growth—amplified by the U.S.-China trade war—justified those cuts.

“Monetary policy is now well positioned to support a strong labor market and return inflation decisively to” the Fed’s 2% target, said Mr. Powell in remarks Monday evening at the Greater Providence Chamber of Commerce. “If the outlook changes materially, policy will change as well.”

Mr. Powell said that the economic outlook had remained favorable this year largely because the Fed had quickly adjusted its policy stance. “While events of the year have not much changed the outlook, the process of getting from there to here has been far from dull,” he said.

The central-bank chief has repeatedly cited risks from global growth and trade uncertainty, together with muted inflation, in explaining why the Fed was lowering its benchmark rate, which is currently in a range between 1.5% and 1.75%. The central bank raised rates four times in 2018 based on expectations inflation would strengthen as solid hiring gains pushed unemployment lower.

In his speech Monday, Mr. Powell walked through a separate, additional justification for the rate reductions: how a reassessment of the economy’s presumed momentum last year warranted rate cuts as it became clear the economy might not have been nearly so strong.

For example, the Labor Department in August previewed a forthcoming revision to job creation for the year ended March 2019 that suggests the economy over this period added an average of 170,000 jobs a month, instead of the initially reported 210,000.

“While this news did not dramatically alter our outlook, it pointed to an economy with somewhat less momentum than we had thought,” Mr. Powell said. The revisions serve as a reminder that “we never have a crystal clear real-time picture of how the economy is performing.”

Mr. Powell said the Fed continually re-examines its outlook about the economy’s underlying growth rate, including the labor market’s capacity to employ workers without generating more inflation and the short-term rate of interest that neither spurs nor slows growth—sometimes called the neutral rate of interest.

This year, economists inside and outside the Fed have lowered their estimates of the neutral rate and the unemployment rate consistent with stable inflation.

A lower neutral rate means the Fed’s short-term rate setting provided “somewhat less support for employment and inflation than previously believed,” Mr. Powell said. A lower unemployment rate consistent with stable prices “would suggest that the labor market was less tight than believed.”

Those developments “were not a game changer for policy, but they provided another reason why a somewhat lower setting of our policy interest rate might be appropriate,” he said. They could also explain why inflation has been weaker than officials expected, Mr. Powell said.

Inflation has been running slightly below the Fed’s 2% target this year after reaching the goal in much of 2018. Excluding volatile food and energy categories, prices were up 1.7% in September from a year earlier. Officials also pay close attention to readings of consumers’ and businesses’ expectations of future inflation because they believe these play an important role in determining actual price changes.

While some Fed officials have played down recent inflation readings as only minor deviations from the Fed’s 2% goal, Mr. Powell said officials needed to be concerned about even a small shortfall because of the difficulty witnessed in Europe and Japan in generating stronger price pressures. Both countries have struggled to lift inflation, leaving interest rates below zero with little room to counteract any slowdown in growth.

“That is why it is essential that we at the Fed use our tools to make sure that we do not permit an unhealthy downward drift in inflation expectations and inflation,” said Mr. Powell.

The Fed’s desire to lift inflation to 2% and to show it isn’t concerned about slightly higher inflation is one reason why officials are unlikely to reverse this year’s interest-rate cuts next year by raising interest rates, even if the economy strengthens.

Mr. Powell said he saw no reason why the economic expansion, which is in its 11th year and is the longest since the U.S. began keeping records in the mid-19th century, couldn’t continue. Earlier on Monday, Mr. Powell and Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren toured a section of East Hartford, Conn., and met with workforce and community development leaders to discuss economic challenges.

In his remarks Monday evening, Mr. Powell said there was growing evidence that the long expansion was benefiting low- and middle-income communities to a degree that hasn’t been experienced in many years.

“At this point in the long expansion, I see the glass as much more than half full,” he said. “With the right policies, we can fill it further.”

Mr. Powell and the Fed have been attacked frequently this year by President Trump for not taking stronger action to support the economy. Mr. Powell has repeatedly said political calculations won’t interfere with the central bank’s analytical and nonpolitical approach to setting policy.

“I think it’s fair to say that doing so has certainly not been easy,” said Sen. Jack Reed (D., R.I.), in introducing Mr. Powell at an annual dinner of local business executives. He effusively praised the Fed leader’s decency and “steady hand.” Before he spoke, Mr. Powell received a standing ovation from hundreds of attendees at the convention center ballroom.

Updated: 12-1-2019

Why You Shouldn’t Expect Rates To Head Upward For A While

Several forces have weighed on U.S. and global inflation for years and appear unlikely to reverse soon.

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell recently set a high bar for raising interest rates, one that looks unlikely to be met for a long while.

“We would need to see a really significant move-up in inflation that’s persistent before we would consider raising rates,” Mr. Powell said at a press conference in October.

Even without a precise definition of significant or persistent, this standard appears out of reach through at least next year, given recent inflation trends and the Fed’s shifting understanding of the economy.

Fed officials raised rates four times last year largely because they expected solid U.S. economic growth and falling unemployment to lift inflation above their 2% target or higher, after it fell short for most of the past decade. They also thought their benchmark rate, even after those increases, was still low enough to drive faster price gains.

But they reversed course this year, cutting rates three times due to slowing global growth and trade uncertainty.

In a speech last week, Mr. Powell also justified the rate reductions by saying the U.S. economy had less momentum last year than Fed officials thought. He also said the Fed’s benchmark interest rate—currently in a range between 1.5% and 1.75%—was providing less support to the economy last year than policy makers thought and even now isn’t very stimulative.

Moreover, several forces have weighed on U.S. and global inflation for years and appear unlikely to reverse soon. These include China’s economic slowdown, aging populations, globalization and technological advances.

Annual U.S. inflation has been running below 2% for most of the past decade and was just 1.3% in October, according to the Fed’s preferred gauge. Core inflation, which excludes volatile food and energy prices, was 1.59% in October.

Mr. Powell and other officials have indicated they would be willing to let inflation exceed 2% for a time to convince people their target isn’t a ceiling.

“The threshold to cut rates is still significantly lower than the threshold to raise rates,” said Diane Swonk, chief economist at Grant Thornton. She said core inflation would probably have to hit 2.25% for six months or so for the Fed to consider lifting rates.

But the last time that happened was in 2008, when circumstances were very different.

Back then, global inflation was climbing as China’s economy grew up to 12% a year, almost twice its current pace, boosting demand for raw materials needed to build new infrastructure and feed an expanding middle class. Between 2003 and 2008, global prices for copper and crude oil quintupled, prices for iron ore quadrupled, and prices for soybeans and corn more than doubled.

The effects of the commodity boom rippled through the U.S. economy. Gasoline and some food prices rose sharply, but so did prices for services including shipping, utilities and air travel. Housing prices surged amid a bubble in subprime lending, while health-care prices climbed about twice as fast as they have risen in the current expansion.

Few of those phenomena appear likely to repeat themselves—individually or in unison—in the foreseeable future.

China’s leaders are reluctant to provide stimulus because they believe a cooling economy is inevitable and even necessary to curb rising debt levels.

While droughts or hurricanes may cause occasional price spikes for some goods, a synchronized surge across commodity markets could require another large nation to repeat China’s boom—something that has few historical precedents.

Core U.S. inflation hasn’t significantly exceeded 2% in the absence of a major rise in commodity prices since the mid-1990s.

Meanwhile, new technologies have enabled the extraction of oil and gas from shale or deep-sea reservoirs that were either unknown or unreachable just a decade ago. U.S. oil production has more than doubled in the past 10 years, reducing the ability of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries to prop up prices—a recurring catalyst for inflation since the 1970s.

When global oil prices spiked in late 2017 and early 2018, U.S. shale drillers quickly increased output, causing prices to fall back. Broader U.S. inflation followed suit, slowing to 1.31% in February 2019 from 2.45% in July 2018.

Also keeping inflation in check are technologies enabling consumers to comparison shop online, older people who buy fewer goods and services and a globally integrated economy that makes many prices less sensitive to domestic factors like changes in wages or productive capacity.

With inflation weak and economic growth slower this year than last, many forecasters have lowered their expectations for Fed rate increases.

“Our forecast is that the Fed’s on hold, really, for the foreseeable future,” said Brett Ryan, a senior U.S. economist at Deutsche Bank.

Updated: 2-16-2020

The Bond Market Might Finally Be Nearing Its Limit

In the next recession, bonds might stop providing investors with the protection they crave against falling stock prices.

For two decades bonds have offered a form of free insurance for investors, tending to move in the opposite direction to stocks over short periods while making good money over the longer run.

But investors counting on the ballast of bonds should take note: There is reason to believe this win-win might be ending. And thus when the next recession hits, bonds may be less useful than they were in the last.

Observe what’s been happening in places with negative interest rates. Shares briefly dropped last month out of fright over the new coronavirus. Government bonds in most places did what they were supposed to do—they rose (and their yields fell). Yet in countries like Germany and Switzerland, they rose far less.

There is some sense to this: In theory, there must be some limit to how negative yields can go. As yields fall (and so prices rise), potential future gains are capped by that boundary, while potential losses from higher yields remain the same. This skew in future returns ought to make bonds progressively less attractive as they approach the lower limit on yields, restricting the gains they can make to offset stock-price falls in bad times.

The U.S. 10-year Treasury price gained almost 3% in the two weeks after human-to-human transmission of the virus was announced. In Germany, though, 10-year bonds offered less protection, with the price rising only 2.3%, even though German stocks fell further than the S&P 500. In Switzerland—which has the lowest interest rates and bond yields in the world—the 10-year benchmark made a paltry 1.2%. (The income from the U.S. bond and lack of income from the German and Swiss bonds accentuates the difference, although it is small over such a short period.)

A couple of weeks of trading doesn’t constitute proof, but this pattern seems to have started only as German yields fell toward zero in early 2015. Before that, the tendency for German stocks and bond prices to move in opposite directions was typically about the same or even stronger than for U.S. stocks and Treasurys.

Since then, the correlation has been consistently weaker, suggesting investors are becoming reluctant to use German bonds—which currently guarantee a loss of 0.39% a year for 10 years if held to maturity—as an alternative to stocks.

The trouble with the theory is writ large in the example of Japan. For two decades after the Bank of Japan took interest rates to 0.5% in 1995, it seemed obvious to many that bond yields had finally hit a floor and could only go up. Yet, yields kept making new lows, with the 10-year falling from 2.8% then to slightly below zero now. Investors betting on higher yields mostly lost money.

Dhaval Joshi, chief European investment strategist at BCA Research, thinks the Japan experience won’t be repeated, because there is a hard floor for yields at around minus 1%. Beyond that, it makes sense to store bank notes in a vault instead, so central banks can’t cut the policy rate much below that without the politically explosive move of abolishing physical cash.

Bond investors might accept an even lower yield for two reasons: because they were betting on being repaid in a new strong German currency after a euro breakup, or because they value the ease of trading that bonds offer compared with physical cash. Even then, there is a limit somewhere.

Most bonds still offer some upside in a recession. If Germany’s 10-year yield fell from the current minus 0.39% to minus 1% because the economy worsened even further, the bond price would rise about 6%. But compare that to the gains in the 2008 crash, when the yield plunged from 4.6% to 2.9% in a little under six months as stocks plummeted. Bondholders made 16%, including the coupon payment, a handy offset to the 25% loss, including dividends, on Germany’s DAX index. The yield on Treasurys, at 1.62%, can fall a lot further, meaning more potential upside for the price.

There is no way to be sure that minus 1% is the right limit; after all, everyone used to think zero was the lower bound, before rates went negative. Still, as government yields have collapsed many big investors have already shifted to other assets, in part because they worry that bonds might not provide the protection they crave in the next downturn.

Assets touted as alternative portfolio cushions are typically just riskier: Stocks with a reliable dividend are more likely to cut their payout than Germany or the U.S. are to default; gold is much more volatile; momentum or volatility-trading strategies come with the risk of sudden swings or trader error; cryptocurrencies bring big security and scam risks and massive volatility, quite apart from logical flaws.

Making it harder for investors to hide from a downturn fits the bigger central-bank plan. Central banks want investors to take more risk, pushing up the price of stocks and corporate bonds and so helping finance new projects.

Investors are right to worry that deeply negative yields will probably make it hard to hedge their portfolio, and will certainly stop bonds providing the free insurance they have offered for the past couple of decades. Exactly where the limit on yields is remains a matter of guesswork, but the more negative yields go, the less effective bonds should be as protection against stock losses.

Updated: 4-25-2020

What Negative Prices Tell Us About The Future

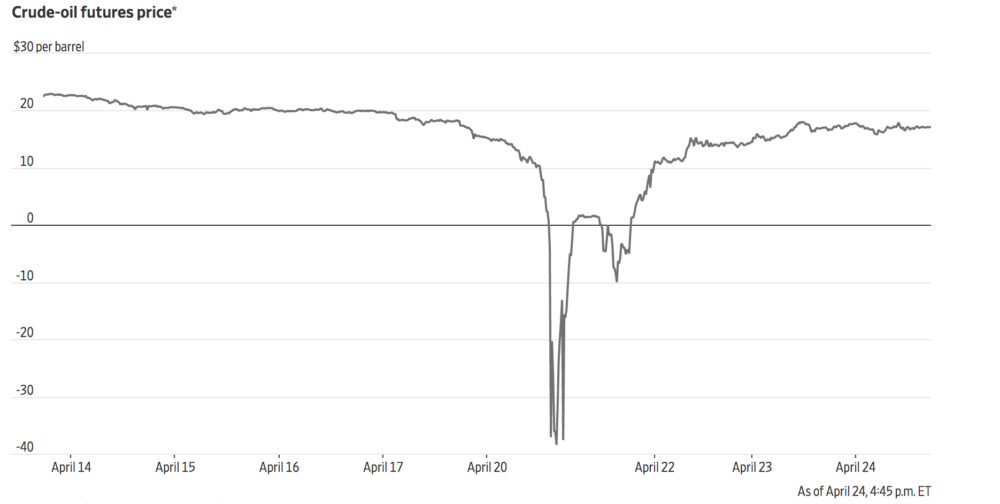

Oil prices falling below $0 are merely the weirdest illustration of the destruction of demand in the economy.

Focus in closely and oil prices turned negative this week because of technicalities in the futures market and storage capacity in Oklahoma. But zoom out and negative oil prices are merely the weirdest illustration of the destruction of demand in the economy—and fit with two longstanding negative prices in Europe, for money and for electricity.

In all three cases, the problem is that supply can’t respond quickly to changes in demand, while demand can’t or won’t increase quickly enough to take advantage of lower prices.

This isn’t normal. In almost all industries, when demand collapses, production is fast turned off. Car factories are closed, and no company would choose to keep them open if it had to pay you to take a new car.

Even in the cases where production has to continue, it would be weird to pay people to consume it. Farmers can’t stop producing milk (or rather their cows can’t) but it would be dumb to pay people to drink it when they can use it to fertilize their fields for free.

Powering Down

European electricity prices have been more negative more often since lockdowns began.

But oil wells aren’t like car factories, and oil isn’t like milk. Closed oil wells are less productive when reopened. That means it is better to keep them running even if their output is temporarily worthless, so long as the owner expects prices to recover. The oil can’t just be dumped, because the toxic sludge is highly regulated. Usually it would be stored to sell when prices recover, but for now storage is basically full.

Oil prices have fallen faster than ever before because demand has fallen faster than ever before. Worse, demand for oil isn’t rising the way it usually does when prices fall, because of the lockdown. Even when things are normal it can take a long time for overall oil use to catch up with lower prices, because it needs a change to behavior, such as driving more or buying a less-efficient big vehicle.

Consumers do respond quickly in some ways, with a study in 2011 finding a close link between monthly fuel prices and the fuel efficiency of newly bought vehicles. When oil prices soared before the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, people switched to small cars, and when they fell again people moved back to SUVs and pickups as soon as they had a job. But it still takes years for such shifts to have a significant effect on overall demand.

The same combination—regulation, production that is costly to cut and demand that isn’t very sensitive to prices—has given France more days with negative electricity prices since its lockdown started in March than it had in the 20 years before that. On Tuesday, Belgian electricity producers had to pay €90 ($97) at lunchtime to get rid of an excess megawatt for an hour, and in Germany the price went to minus €84—with far more days with negative prices than usual.

Throwing Money At The Problem

Better-than-free money in Europe hasn’t done much to boost borrowing.

Better-than-free electricity has been familiar in Europe on windy, sunny days thanks to subsidized wind farms and solar plants, but has been worsened by the collapse in industrial and office power demand.

Power markets are different from oil, but there are parallels in each part of the supply-demand imbalance. Extra generation can’t just be earthed without damage to network equipment, so it has to be sold whatever the price. There is little capacity to store electricity (though more is being developed). Coal and nuclear power plants are slow or expensive to shut, just as with oil wells.

“Negative prices may be phased out when demand comes back and storage starts to come through,” says Dan Eager, principal analyst for European power at Wood Mackenzie. He could equally be talking about oil—or money.

The European Central Bank has made the price of money, the interest rate, negative as it struggles with the same problems as oil producers and power generators. The supply of savings is stubbornly high; savers are failing to respond to the punishment of superlow interest rates. Negative rates were also slow to boost demand for money, with the weak economy deterring companies and individuals from borrowing to invest or spend, even when they were paid to do so. The coronavirus-induced recession worsens the situation.

Money can be stored more easily than electricity or oil, but the cost, risk and regulatory disapproval of holding large amounts of bank notes has so far meant little is piled in vaults.

The puzzle for investors is what will happen to supply and demand after the lockdown. If supply is permanently damaged—closed oil wells and mothballed power plants, and savers forced to spend their rainy-day funds—while demand rapidly returns to normal, the rigidities that pushed prices negative could lead to them rising fast. Other industries could suffer too, with supply-chain problems or staffing troubles if they can’t hire back the workers they fired. A lack of savings and a need to invest to rebuild supply chains and damaged production would mean higher interest rates, or inflation, or both.

On the other hand, if the economy is reopened and oil wells, factories and power plants get up and running quickly and savers return to their frugal habits, while consumers stay cautious, we could have a long period of falling prices and lower interest rates—deflation.

It could all be fine if both supply and demand come back together as the economy is reopened. But balancing these two opposite risks without falling into either inflation or deflation is going to be tricky.

Share Your Thoughts

What do you think of the Fed’s ‘lower-for-longer’ outlook for interest rates? Join the conversation below.

Updated: 9-30-2020

Fed’s Low-Rate Strategy Confronts Concerns Over Bubbles

Lack of consensus on how to handle possible asset bubbles could threaten the central bank’s willingness to maintain its low-rate promises.

Federal Reserve officials’ promises to hold interest rates very low for a long time could pose a dilemma once the pandemic is over: how to deal with the risk of asset bubbles.

Those concerns flared when Dallas Fed President Robert Kaplan dissented from the central bank’s Sept. 16 decision to spell out those promises. The Fed committed to hold short-term rates near zero until inflation reaches 2% and is likely to stay somewhat above that level—something most officials don’t see happening in the next three years.

“There are costs to keeping rates at zero for a prolonged period,” Mr. Kaplan said in an interview. He added that he worries such a commitment “causes people to take more risk in that they know it’s much less likely that they’re going to be able to earn on savings.”

The question of whether the Fed should raise rates to prevent bubbles from forming has long vexed officials. Mr. Kaplan’s concerns show how the lack of consensus could one day sow doubts over the central bank’s ability or willingness to follow through on the new lower-for-longer rate framework Fed Chairman Jerome Powell unveiled last month.

The new strategy, adopted unanimously by the Fed’s five governors and 12 reserve-bank presidents, alters how the central bank will react to changes in the economy. The Fed is now seeking periods of inflation above its 2% target to compensate for periods like the current one, when inflation is running below that goal and short-term rates are pinned near zero. This means the Fed will effectively abandon its prior approach of raising rates pre-emptively, before inflation reaches 2%.

The Fed’s statement spelling out the new framework included an escape clause of sorts by saying that achieving its inflation and employment goals “depends on a stable financial system.”

The Fed’s subsequent Sept. 16 rate guidance alluded obliquely to financial bubbles by saying officials would adjust their current lower-for-longer policy stance “if risks emerge that could impede the attainment of the committee’s goals.”

Mr. Kaplan said his concerns were reinforced in March after the coronavirus pandemic triggered a near financial panic. “I saw…a lot of forced selling,” he said. “There were just some people who came into this with too much risk.”

To be sure, with millions of Americans displaced from work and loan defaults on the rise, no one at the Fed is worrying that their policies are too easy right now. Rather, the question is about the trade-offs they might face if, after the pandemic has passed, inflation remains slow to rise to their goal of averaging 2%.

“I share a lot of Rob’s concerns,” said Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren, who doesn’t have a vote on the Fed’s rate-setting committee until 2022. “I am worried about financial-stability aspects of this policy. I think we’re going to need to address it over the next couple of years,” he said in an interview.

Financial-stability concerns motivated Mr. Rosengren to vote against three separate interest-rate cuts last year. He has warned for years of potential excesses building in commercial real estate that would worsen a downturn, a prophecy he worries the pandemic will fulfill.

“People reach for yield in commercial real estate when interest rates get quite low, and you start doing riskier projects, and when the economy hits a shock—in this case, it was a pandemic—it means that big losses are going to likely occur,” Mr. Rosengren said.

He also pointed to bankruptcies of many larger retailers, hastened by the pandemic. “One of the reasons they’re failing is they took on a lot of debt,” he said.

Mr. Rosengren expects a difficult economic recovery and said he had no concerns signaling that the central bank expects to keep rates very low for several years. But he said he “would have preferred a more muscular financial-stability statement.”

While Mr. Powell hasn’t ruled out using interest rates to one day address financial bubbles, he has repeatedly played down such prospects. “Monetary policy should not be the first line of defense,” he said this month.

When pressed on whether the Fed would raise rates if other defenses didn’t materialize or were inadequate, Mr. Powell implied the bar was high. “It’s not something we’ve done,” he said.

Before the mid-1990s, recessions were triggered by an overheating economy that generated higher inflation. The Fed raised interest rates, and spending fell. Setting the right interest rate could achieve both low, stable inflation and low unemployment, which economists dubbed the “divine coincidence.”

But, as Mr. Powell said in a 2017 speech, this doesn’t mean the same interest rate will achieve those two goals plus a third one: a stable financial system.

“Monetary policy is one tool. It can’t take care of everything,” said Nellie Liang, a former Fed economist who is now at the Brookings Institution.

Ms. Liang and Mr. Rosengren are among those who say it would be easier for the Fed to execute its new framework if Congress granted the central bank or other regulators better so-called macroprudential tools to address problems such as high levels of indebtedness or the heavy use of short-term borrowings to finance long-term assets.

The more effective those other tools are, the lower the costs of keeping interest rates lower for longer, they say. “We don’t have anybody that has authority like the Bank of England to think about, ‘Is the household sector or the corporate sector unduly leveraged?’ ” Mr. Rosengren said.

Trump Concedes Economic Defeat, Trump Concedes Economic Defeat,Trump Concedes Economic Defeat,Trump Concedes Economic Defeat,Trump Concedes Economic Defeat,Trump Concedes Economic Defeat,Trump Concedes Economic Defeat,Trump Concedes Economic Defeat,Trump Concedes Economic Defeat,Trump Concedes Economic Defeat,Trump Concedes Economic Defeat,Trump Concedes Economic Defeat,Trump Concedes Economic Defeat,Trump Concedes Economic Defeat,Trump Concedes Economic Defeat,Trump Concedes Economic Defeat,Trump Concedes Economic Defeat,Trump Concedes Economic Defeat,Trump Concedes Economic Defeat,Trump Concedes Economic Defeat,Trump Concedes Economic Defeat,Trump Concedes Economic Defeat,

Related Articles:

U.S. Corporate Insiders Selling Shares At Fastest Pace Since 2008 (#GotBitcoin?)

Median U.S. Household Income Slows As U.S. Job Openings Cool

High Debt Levels Are Weighing On Economies (#GotBitcoin?)

Budget Deficit Grow, Stocks, Bond Yields Fall, Negative Interest Rates Spread!

Central Banks Plan For Negative Interest Rates (#GotBitcoin?)

Junk Bond Yields Go Negative As Central Banks Cut Interest Rates And Print Money (#GotBitcoin?)

White House Pushes Fed Towards Negative Interest Rates (#GotBitcoin?)

U.S. Junk Bonds With Negative Yields? Yes, Kind of (#GotBitcoin?)

Investors Ponder Negative Bond Yields In The U.S. (#GotBitcoin?)

European Central Bank Warns World Of Drawbacks of Negative Rates (#GotBitcoin?)

Bond Yields Sink To New Lows, Federal Deficits Skyrocket And Trump Back-Tracks On Tax Cuts

Recession Is Looming, or Not. Here’s How To Know (#GotBitcoin?)

How Will Bitcoin Behave During A Recession? (#GotBitcoin?)

Many U.S. Financial Officers Think a Recession Will Hit Next Year (#GotBitcoin?)

Definite Signs of An Imminent Recession (#GotBitcoin?)

What A Recession Could Mean for Women’s Unemployment (#GotBitcoin?)

Investors Run Out of Options As Bitcoin, Stocks, Bonds, Oil Cave To Recession Fears (#GotBitcoin?)

Goldman Is Looking To Reduce “Marcus” Lending Goal On Credit (Recession) Caution (#GotBitcoin?)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.