Have You Broken A Federal Criminal Law Lately? Who Knows? No One Has Been Able To Count Them All!!!

There Has Been Many Failed Efforts To Count Nation’s Federal Criminal Laws Have You Broken A Federal Criminal Law Lately? Who Knows? No One Has Been Able To Count Them All!!!

“Simply pouring a bottle of vinegar into a bowl to kill someone’s goldfish, could potentially be punishable by life imprisonment.” – Justice Samuel Alito

“This effort came as part of a long and ultimately failed campaign to persuade Congress to revise the criminal code, which by the 1980s was scattered among 50 titles and 23,000 pages of federal law. You will have died and been resurrected three times and still not have an answer to this question.” – said Ronald Gainer, a retired Justice Department official

For decades, the task of counting the total number of federal criminal laws has bedeviled lawyers, academics and government officials.

In 1982, while at the Justice Department, Mr. Gainer oversaw what still stands as the most comprehensive attempt to tote up a number. The effort came as part of a long and ultimately failed campaign to persuade Congress to revise the criminal code.

Justice Department lawyers undertook “the laborious counting” of the scattered statutes “for the express purpose of exposing the idiocy” of the system, said Mr. Gainer, now 76 years old.

It can often be very difficult to make a call whether or not something counts as a single crime or many. That task fell to one lawyer, Mr. Gainer says, who read the statutes and ultimately used her judgment to decide: If a particular act fell under multiple crime categories—such as forms of fraud that could also be counted as theft—she had to determine whether it could be prosecuted under each. If an offense could be counted in either of two sections, she counted them separately, Mr. Gainer said.

The project stretched two years. In the end, it produced only an educated estimate: about 3,000 criminal offenses. Since then, no one has tried anything nearly as extensive.

The Drug Abuse Prevention and Control section of the code—Title 21—provides a window into the difficulties of counting. More than 130 pages in length, it essentially pivots around two basic crimes, trafficking and possession. But it also delves into the specifics of hundreds of drugs and chemicals.

Scholars debate whether the section comprises two offenses or hundreds. Reading it requires toggling between the historical footnotes, judicial opinions and other sections in the same title. It has also been amended 17 times.

In 1998, the American Bar Association performed a computer search of the federal codes looking for the words “fine” and “imprison,” as well as variations. The ABA study concluded the number of crimes was by then likely much higher than 3,000, but didn’t give a specific estimate.

“We concluded that the hunt to say, ‘Here is an exact number of federal crimes,’ is likely to prove futile and inaccurate,” says James Strazzella, who drafted the ABA report. The ABA felt “it was enough to picture the vast increase in federal crimes and identify certain important areas of overlap with state crimes,” he said.

None of these studies broached the separate—and equally complex—question of crimes that stem from federal regulations, such as, for example, the rules written by a federal agency to enforce a given act of Congress. These rules can carry the force of federal criminal law. Estimates of the number of regulations range from 10,000 to 300,000. None of the legal groups who have studied the code have a firm number.

“There is no one in the United States over the age of 18 who cannot be indicted for some federal crime,” said John Baker, a retired Louisiana State University law professor who has also tried counting the number of new federal crimes created in recent years. “That is not an exaggeration.”

As Criminal Laws Proliferate, More Americans Are Ensnared

Eddie Leroy Anderson of Craigmont, Idaho, is a retired logger, a former science teacher and now a federal criminal thanks to his arrowhead-collecting hobby.

In 2009, Mr. Anderson loaned his son some tools to dig for arrowheads near a favorite campground of theirs. Unfortunately, they were on federal land. Authorities “notified me to get a lawyer and a damn good one,” Mr. Anderson recalls.

There is no evidence the Andersons intended to break the law, or even knew the law existed, according to court records and interviews. But the law, the Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979, doesn’t require criminal intent and makes it a felony punishable by up to two years in prison to attempt to take artifacts off federal land without a permit.

Faced with that reality, the two men, who didn’t find arrowheads that day, pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor and got a year’s probation and a $1,500 penalty each. “We kind of wonder why it got took to the level that it did,” says Mr. Anderson, 68 years old.

Wendy Olson, the U.S. Attorney for Idaho, said the men were on an archeological site that was 13,000 years old. “Folks do need to pay attention to where they are,” she said.

The Andersons are two of the hundreds of thousands of Americans to be charged and convicted in recent decades under federal criminal laws—as opposed to state or local laws—as the federal justice system has dramatically expanded its authority and reach.

As federal criminal statutes have ballooned, it has become increasingly easy for Americans to end up on the wrong side of the law. Many of the new federal laws also set a lower bar for conviction than in the past: Prosecutors don’t necessarily need to show that the defendant had criminal intent.

Would-Be Inventor And Felon Kirster Evertson:

Would-Be Inventor And Felon Kirster Evertson:‘If I Had Abandoned The Chemicals, Why

Would I Have Told The Investigators About Them?

These factors are contributing to some unusual applications of justice. Father-and-son arrowhead lovers can’t argue they made an innocent mistake. A lobster importer is convicted in the U.S. for violating a Honduran law that the Honduran government disavowed. A Pennsylvanian who injured her husband’s lover doesn’t face state criminal charges—instead, she faces federal charges tied to an international arms-control treaty.

The U.S. Constitution mentions three federal crimes by citizens: treason, piracy and counterfeiting. By the turn of the 20th century, the number of criminal statutes numbered in the dozens. Today, there are an estimated 4,500 crimes in federal statutes, according to a 2008 study by retired Louisiana State University law professor John Baker.

There are also thousands of regulations that carry criminal penalties. Some laws are so complex, scholars debate whether they represent one offense, or scores of offenses.

Counting them is impossible. The Justice Department spent two years trying in the 1980s, but produced only an estimate: 3,000 federal criminal offenses.

The American Bar Association tried in the late 1990s, but concluded only that the number was likely much higher than 3,000. The ABA’s report said “the amount of individual citizen behavior now potentially subject to federal criminal control has increased in astonishing proportions in the last few decades.”

A Justice spokeswoman said there was no quantifiable number. Criminal statutes are sprinkled throughout some 27,000 pages of the federal code.

There are many reasons for the rising tide of laws. It’s partly due to lawmakers responding to hot-button issues—environmental messes, financial machinations, child kidnappings, consumer protection—with calls for federal criminal penalties. Federal regulations can also carry the force of federal criminal law, adding to the legal complexity.

Justice Anthony Kennedy, Pictured,

Justice Anthony Kennedy, Pictured,Recently Voiced Concern Over A Statute.

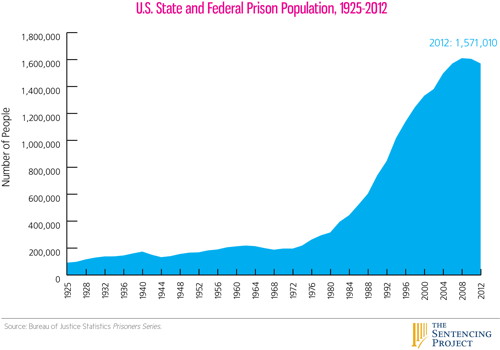

With the growing number of federal crimes, the number of people sentenced to federal prison has risen nearly threefold over the past 30 years to 83,000 annually. The U.S. population grew only about 36% in that period. The total federal prison population, over 200,000, grew more than eightfold—twice the growth rate of the state prison population, now at 2 million, according the Federal Bureau of Justice Statistics

Tougher federal drug laws account for about 30% of people sentenced, a decline from over 40% two decades ago. The proportion of people sentenced for most other crimes, such as firearms possession, fraud and other non-violent offenses, has doubled in the past 20 years.

The growth in federal law has produced benefits. Federal legislation was indispensable in winning civil rights for African-Americans. Some of the new laws, including those tackling political corruption and violent crimes, are relatively noncontroversial and address significant problems. Plenty of convicts deserve the punishment they get.

Roscoe Howard, the former U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia, argues that the system “isn’t broken.” Congress, he says, took its cue over the decades from a public less tolerant of certain behaviors. Current law provides a range of options to protect society, he says. “It would be horrible if they started repealing laws and taking those options away.”

Still, federal criminal laws can be controversial. Some duplicate existing state criminal laws, and others address matters that might better be handled as civil rather than criminal matters.

Some federal laws appear picayune. Unauthorized use of the Smokey Bear image could land an offender in prison. So can unauthorized use of the slogan “Give a Hoot, Don’t Pollute.”

The spread of federal statues has opponents on both sides of the aisle, though for different reasons. For Republicans, the issue is partly about federal intrusions into areas historically handled by states. For Democrats, the concerns include the often lengthy prison sentences that federal convictions now produce.

Those expressing concerns include the American Civil Liberties Union and Edwin Meese III, former attorney general under President Ronald Reagan. Mr. Meese, now with the conservative Heritage Foundation, argues Americans are increasingly vulnerable to being “convicted for doing something they never suspected was illegal.”

“Most people think criminal law is for bad people,” says Timothy Lynch of Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank. People don’t realize “they’re one misstep away from the nightmare of a federal indictment.”

Last September, retired race-car champion Bobby Unser told a congressional hearing about his 1996 misdemeanor conviction for accidentally driving a snowmobile onto protected federal land, violating the Wilderness Act, while lost in a snowstorm. Though the judge gave him only a $75 fine, the 77-year-old racing legend got a criminal record.

Mr. Unser says he was charged after he went to authorities for help finding his abandoned snowmobile. “The criminal doesn’t usually call the police for help,” he says.

A Justice Department spokesman cited the age of the case in declining to comment. The U.S. Attorney at the time said he didn’t remember the case.

Some of these new federal statutes don’t require prosecutors to prove criminal intent, eroding a bedrock principle in English and American law. The absence of this provision, known as mens rea, makes prosecution easier, critics argue.

A study last year by the Heritage Foundation and the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers analyzed scores of proposed and enacted new laws for nonviolent crimes in the 109th Congress of 2005 and 2006. It found of the 36 new crimes created, a quarter had no mens rea requirement and nearly 40% more had only a “weak” one.

Some jurists are disturbed by the diminished requirement to show criminal intent in order to convict. In a 1998 decision, federal appellate judge Richard Posner, a noted conservative, attacked a 1994 federal law under which an Illinois man went to prison for three years for possessing guns while under a state restraining order taken out by his estranged wife. He possessed the guns otherwise legally, they posed no immediate threat to the spouse, and the restraining order didn’t mention any weapons bar.

“Congress created, and the Department of Justice sprang, a trap” on a defendant who “could not have suspected” he was committing a crime, Judge Posner wrote.

Another area of concern among some jurists is the criminalization of issues that they consider more appropriate to civil lawsuits. In December, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which is considered liberal, overturned the fraud conviction of a software-company executive accused of helping to issue false financial statements. The government tried “to stretch criminal law beyond its proper bounds,” wrote the Circuit’s chief judge, Alex Kozinski.

Civil law, he said, is a better tool to judge “gray area” conduct—actions that might, or might not, be illegal. Criminal law, he said, “should clearly separate conduct that is criminal from conduct that is legal.”

Occasionally, Americans are going to prison in the U.S. for violating the laws and rules of other countries. Last year, Abner Schoenwetter finished 69 months in federal prison for conspiracy and smuggling. His conviction was related to importing the wrong kinds of lobsters and bulk packaging them in plastic, rather than separately in boxes, in violation of Honduran laws.

According to court records and interviews, Mr. Schoenwetter had been importing lobsters from Honduras since the mid-1980s. In early 1999, federal officials seized a 70,000-pound shipment after a tip that the load violated a Honduran statute setting a minimum size on lobsters that could be caught. Such a shipment, in turn, violated a U.S. law, the Lacey Act, which makes it a felony to import fish or wildlife if it breaks another country’s laws. Roughly 2% of the seized shipment was clearly undersized, and records indicated other shipments carried much higher percentages, federal officials said.

In an interview, Mr. Schoenwetter, 65 years old, said he and other buyers routinely accepted a percentage of undersized lobsters since the deliveries from the fishermen inevitably included smaller ones. He also said he didn’t believe bringing in some undersized lobsters was illegal, noting that previous shipments had routinely passed through U.S. Customs.

After conviction, Mr. Schoenwetter and three co-defendants appealed, and the Honduran government filed a brief on their behalf saying that Honduran courts had invalidated the undersized-lobster law. By a two-to-one vote, however, a federal appeals panel found the Honduran law valid at the time of the trial and upheld the convictions.

The dissenting jurist, Judge Peter Fay, wrote: “I think we would be shocked should the tables be reversed and a foreign nation simply ignored one of our court rulings.”

Robert Kern, a 62-year-old Virginia hunting-trip organizer, was also prosecuted in the U.S. for allegedly breaking the law of another country. Instead of lobsters from Honduras, Mr. Kern’s troubles stemmed from moose from Russia.

He faced a 2008 Lacey Act prosecution for allegedly violating Russian law after some of his clients shot game from a helicopter in that country. In the end, he was acquitted after a Russian official testified the hunters had an exemption from the helicopter hunting ban. Still, legal bills totaling more than $860,000 essentially wiped out his retirement savings, Mr. Kern says.

Justice Department officials declined to comment on Messrs. Kern and Schoenwetter.

One area of expansion has been environmental crimes. Since its inception in 1970, the Environmental Protection Agency has grown to enforce some 25,000 pages of federal regulations, equivalent to about 15% of the entire body of federal rules. Many of the EPA rules carry potential criminal penalties. Krister Evertson, a would-be inventor, recently spent 15 months in prison for environmental crimes where there was no evidence he harmed anyone, or intended to.

In May 2004 he was arrested near Wasilla, Alaska, and charged with illegally shipping sodium metal, a potentially flammable material, without proper packaging or labeling.

He told federal authorities he had been in Idaho working to develop a better hydrogen fuel cell but had run out of money. He had moved some sodium and other chemicals to a storage site near his workshop in Salmon, Idaho, before traveling back to his hometown of Wasilla to raise money by gold-mining.

Mr. Evertson said he believed he had shipped the sodium legally. A jury acquitted him in January 2006.

However, Idaho prosecutors, using information Mr. Evertson provided to federal authorities in Alaska, charged him with violating the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, a 1976 federal law that regulates handling of toxic waste. The government contended Mr. Evertson had told federal investigators he had abandoned the chemicals. It also said the landlord of the Idaho storage site claimed he was owed back rent and couldn’t find the inventor—allegations Mr. Evertson disputed.

Once the government deemed the chemicals “abandoned,” they became “waste” and subject to RCRA. He was charged under a separate federal law with illegally moving the chemicals about a half-mile to the storage site.

“If I had abandoned the chemicals, why would I have told the investigators about them?” said Mr. Evertson in an interview. He added that he spent $100,000 on the material and always planned to resume his experiments.

Prosecutors emphasized the potential danger of having left the materials for two years. “You clean up after yourself and don’t leave messes for others,” one prosecutor told the jury, which convicted Mr. Evertson on three felony counts. Prosecutors said clean-up of the site cost the government $400,000. Mr. Evertson, 57, remains on probation, working as night watchman in Idaho.

In a statement, Ms. Olson, the Idaho U.S. Attorney, said that by leaving dangerous chemicals not properly attended he endangered others and caused the government to spend more than $400,000 in clean-up costs. “This office will continue to aggressively prosecute” environmental crimes, she said.

Critics contend that federal criminal law is increasingly, and unconstitutionally, impinging on the sovereignty of the states. The question recently came before the Supreme Court in the case of Carol Bond, a Pennsylvania woman who is fighting a six-year prison sentence arising out of violating a 1998 federal chemical-weapons law tied to an international arms-control treaty. The law makes it a crime for an average citizen to possess a “chemical weapon” for other than a “peaceful purpose.” The statute defines such a weapon as any chemical that could harm humans or animals.

Ms. Bond’s criminal case stemmed from having spread some chemicals, including an arsenic-based one, on the car, front-door handle and mailbox of a woman who had had an affair with her husband. The victim suffered a burn on her thumb.

In court filings, Ms. Bond’s attorneys argued the chemical-weapons law unconstitutionally intruded into what should have been a state criminal matter. The state didn’t file charges on the chemicals, but under state law she likely would have gotten a less harsh sentence, her attorneys said.

Last month, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled Ms. Bond has standing to challenge the federal law. By distributing jurisdiction among federal and state governments, the Constitution “protects the liberty of the individual from arbitrary power,” Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote for the court. “When government acts in excess of its lawful powers, that liberty is at stake.”

Arrest Records From Way Back Hunt Current Employees

Companies Struggle to Navigate Patchwork of Rules That Either Encourage or Deter Hiring Americans With Criminal Records

Eddie Sorrells is evaluating job applicants he knows he can’t hire.

The chief operating officer of DSI Security Services, a provider of security guards, is checking out potential employees with felony or certain misdemeanor convictions even though they wouldn’t get licensed in many of the 23 states where the firm operates.

Driving the company in that direction are government officials in Washington and elsewhere who want to give people with rap sheets a better shot at a job. Mr. Sorrells figures the reviews take up hundreds of hours of staff time a year.

“It defies common sense,” said Mr. Sorrells, who is general counsel as well as COO of the Dothan, Ala., family-owned company.

Three decades of tougher laws and policing have left nearly one in three adult Americans with a criminal record, according to data kept by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. That arrest wave is washing up on the desks of America’s employers.

Companies seeking new employees are forced to navigate a patchwork of state and federal laws that either encourage or deter hiring people with criminal pasts and doing the checks that reveal them. Employers are having to make judgments about who is rehabilitated and who isn’t. And whichever decision they make, they face increasing possibilities for ending up in court.

Employers are in this position because there are nearly 80 million Americans with criminal records, including arrests that didn’t lead to a conviction, at a time when the Internet and computerized databases make such information easier than ever to obtain. Ignoring the records can leave a company vulnerable to making bad hiring decisions and to lawsuits. But using them can raise the ire of government officials and lead to charges of discrimination.

Scott Fallavollita, the owner of United Tool & Machine Corp. in Wilmington, Mass., said his first priority is keeping his 25-employee workplace safe. At the same time, he has hired individuals with criminal records who were good workers. “I think most people can see both sides and really want to do the right thing,” he said.

The number of companies running criminal background checks has increased steeply in recent decades, said Michael Stoll, a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, who has studied the topic. In the early 1990s, he said, fewer than 50% of employers used background checks.

But 87% of employers were doing them on some or all job applicants in 2012, a survey that year by the Society for Human Resource Management showed. The figure was 92% in 2010, according to the professional group.

Michael Aitken, its vice president of government affairs, said the recent decline could stem from the complex legal landscape. “Some employers might say it isn’t worth walking into that minefield,” he said, even though “a bad hire can have consequences for the company, its employees and its customers if that person commits another crime.”

Much of the nervousness traces to a 2012 document from the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. It recommended that employers not ask about criminal records on initial application forms. Before rejecting someone because of a criminal record, it said, the employer should examine such things as when a conviction occurred, whether the crime was related to the job in question and what rehabilitation efforts the individual had made.

Though not a law, the document, called an enforcement guidance, has teeth. It is the EEOC’s position on what the 1964 Civil Rights Act’s employment-discrimination section, Title VII, requires of employers.

It revises guidance from the 1980s. An update was needed, said EEOC Chairwoman Jenny Yang, because “more Americans have criminal records than they did [and] the Internet makes access to criminal records more available.”

‘‘Would I say that anyone with a felony record doesn’t deserve a job? Of course not. Just not a job in the security business.’’

—Eddie Sorrells, chief operating officer of DSI Security Services

In addition, 13 states and nearly 70 local jurisdictions have passed laws restricting employer requests for criminal records early in the hiring process, according to the National Employment Law Project, a nonprofit research and advocacy group. Some of these “ban-the-box” laws—referring to a check-off box on forms—don’t allow asking until a conditional job offer has been made.

The restrictions help those with rap sheets at least get a foot in the door. Yet companies remain within their rights to check criminal records at some point. The EEOC says there are instances where a criminal record is a valid reason to turn down a job applicant.

Washington, D.C., has a ban-the-box law. “You have people right now to the tune of 8,000 residents per year coming home to the District of Columbia from incarceration,” said Councilman Kenyan McDuffie, a Democrat. If they can’t find jobs, he said, crime rates go up, along with social-service and law-enforcement costs.

Race is a factor. Some minority groups, particularly black males, have higher arrest and conviction rates than whites, putting companies at risk of getting crosswise with the federal government’s antidiscrimination rules.

Under federal law, a decision that appears race-neutral, such as asking about criminal records in hiring, can run into legal problems if its effect is to disproportionately harm a particular racial or ethnic group.

A 2009 study of 250 entry-level job openings in New York City found an applicant’s likelihood of getting a callback or job offer fell by nearly 50% with a criminal record. Black applicants with records fared far worse than similarly situated white applicants in the study, done by researchers at Princeton and Harvard universities.

Critics of delaying a criminal-record question say this can just postpone the inevitable. “If it is a disqualifying offense, you’ve just wasted both the candidate’s and the employer’s time,” said Nick Fishman, executive vice president of EmployeeScreenIQ, a background-screening firm in Cleveland.

Grocery-store chain Aldi Inc., which operates in 32 states with varying laws, dropped the question from applications, said Thomas Behtz, a vice president. The Batavia, Ill., firm now asks about criminal history only after making a conditional job offer, then gives the applicant a questionnaire tailored to what can be asked in the state at issue.

“I wouldn’t say we feel handcuffed. But things are very, very defined,” Mr. Behtz said.

DSI, the security-guard firm whose Mr. Sorrells is evaluating some applicants he can’t hire, uses a criminal-background question on application forms in states where this is permitted and not elsewhere.

The firm doesn’t automatically exclude applicants who admit to being felons, instead proceeding to look at whether they meet other hiring criteria, such as willingness to work the hours and locations available. If so, it does an individualized assessment of the criminal record.

Only then, Mr. Sorrells said, does the company reject the applicant. A felon couldn’t get licensed as a security guard in most states where DSI operates, Mr. Sorrells said. Even where they could, the company—though it has hired people with minor misdemeanors—won’t employ felons.

The reason is “liability concerns and what we believe is our obligation to put the most qualified and well-suited officer at the client’s property,” he said.

“Would I say that anyone with a felony record doesn’t deserve a job? Of course not,” said Mr. Sorrells. “Just not a job in the security business.”

In its policing efforts, the EEOC has launched 100 investigations and a series of enforcement cases. It has reached settlements in the past year with six companies over alleged misuse of criminal history, the agency said in a report.

The EEOC settled with a PepsiCo Inc. unit in 2012 over allegedly discriminatory treatment of black applicants with criminal histories. Pepsi Beverages agreed to pay $3.1 million and possibly offer positions to some applicants. In a written statement, Pepsi said there wasn’t any finding of intentional discrimination, and it has worked with the EEOC to revise its hiring policy.

Retailer Dollar General Corp. and a U.S. unit of BMW AG are currently being sued by the EEOC. Both denied wrongdoing.

G4S Secure Solutions (U.S.A.) Inc., a Jupiter, Fla., supplier of security services, said it spent several hundred thousand dollars responding to information requests from the agency during a nearly three-year probe stemming from a complaint filed by a black applicant rejected for a security-guard job. G4S said he was turned down because of two theft convictions.

Once the EEOC starts looking into a company, “the burden is almost unending on the employer until it meets whatever expectation” for information the commission has, said Geoff Gerks, senior vice president at G4S. The probe ended with no charges by the EEOC, and G4S reached settlements with two individuals, he said.

The EEOC said it doesn’t confirm or deny the existence of particular investigations or comment on pending litigation.

A judge last year dismissed an EEOC suit accusing a Dallas events-marketing firm, Freeman Co., of a pattern of discrimination based partly on its use of criminal-background information. Judge Roger W. Titus, in dismissing the suit in federal court in Greenbelt, Md., said the agency was asking companies to ignore “criminal history and credit background, thus exposing themselves to potential liability for criminal and fraudulent acts committed by employees, on the one hand, or incurring the wrath of the EEOC.”

The EEOC has appealed. Freeman declined to comment.

While the federal government and some states have been moving to help people with criminal records catch a break, others have challenged the EEOC’s campaign or have toughened background-check requirements.

Texas sued the EEOC in federal court in Lubbock seeking to set aside the 2012 enforcement guidance, which the state’s complaint called the “felon-hiring rule.” The court said Texas didn’t have standing to challenge the rule, a decision the state is appealing.

Iowa recently expanded a background-check requirement for home-based child-care providers to include checks against the FBI’s criminal-records system, not just Iowa criminal records.

Ohio in 2007 passed a law barring people convicted of certain crimes from working in public schools. The Cincinnati system discharged 10 employees, nine of them black. Two of the nine filed a suit in Cincinnati federal court, which is still pending, alleging racial discrimination.

One plaintiff, Eartha Britton, 60 years old, was an instructional assistant and 18-year veteran. Her crime: a 1983 conviction for being a go-between in the sale of $5 worth of marijuana, a conviction that was later expunged, the suit said. Through her attorney, she declined to be interviewed.

The Cincinnati school district said in a court filing that public and private employers shouldn’t be in the position of second-guessing state law.

Even businesses that don’t hire can get entangled in the issue. Care.com Inc. is an online service that helps customers find caregivers. Though the caregivers aren’t its employees, the Waltham, Mass., firm faces a suit over the background of one.

Clients Nathan and Reggan Koopmeiners say in the civil suit they paid the firm for its highest level of background check, yet it didn’t tell them that a woman they hired had a “history of alcohol abuse and violence.” Under the influence of alcohol, she negligently struck or slammed the head of their infant daughter, killing her, said the suit, filed in Wisconsin state court in July and later transferred to Milwaukee federal court. The woman faces a murder charge, to which she has pleaded not guilty, said her attorney, who said she didn’t intend to harm the child.

Care.com said it screens caregivers based on information they provide, including searching a criminal database, but this is only a preliminary check and it offers three higher levels of checks at different prices. In a court filing, it said the Koopmeiners hadn’t purchased any of those, and it denied wrongdoing.

The varying impulses—to give job seekers a fair shot, to keep workplaces safe and to keep companies out of legal jeopardy—have left Paul O’Brien, president of engineering firm GHT Ltd. in Arlington, Va., struggling to chart a course.

He once hired a mechanical engineer with convictions for burglaries, figuring he had turned his life around, and it worked out fine. At the same time, some of GHT’s federal contracts require criminal-background checks of employees, Mr. O’Brien said. He is watching the growth of restrictions on such record checks.

“You gotta know what you’re getting into,” he said. Otherwise, “you bring somebody in and after he embezzles from you, then you find out he embezzled from his last boss, too?”

GHT’s job application still has a criminal-history question. Mr. O’Brien is thinking of dropping it. “I don’t want to get on the wrong side of the government,” he said.

Driver Bobby Unser Got A Criminal Record

Driver Bobby Unser Got A Criminal RecordAfter Being Lost In A Blizzard.

Obama, Koch Brothers Team Up To Push For Rewrite of Federal Sentencing Laws

When President Barack Obama praised conservatives Charles and David Koch for their efforts to overhaul the criminal-justice system, laughter rippled through the crowd at the annual convention of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

“No,” Mr. Obama said, “You’ve got to give them credit. You’ve got to call it like you see it.”

Mr. Obama’s tribute took many Democrats by surprise, given years of animosity between the two camps. It was a hint, however, of a deeper relationship. Behind the scenes, the Democratic White House and the high-dollar Republican donors have teamed up to push for a rewrite of federal sentencing laws and other changes to the criminal-justice system.

Koch Industries officials have met with top White House officials in recent months. Valerie Jarrett, an Obama confidante and senior adviser, spoke with David Koch about these issues a few weeks ago at the Aspen Ideas Festival, and Ms. Jarrett says she has an “open channel of communication” with the Kochs’ point man on criminal justice.

Charles Koch said in an interview he is encouraged by the fact that “the White House is cooperating with us rather than assuming everything we do is evil.” Quoting abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass, he added: “I will work with anyone to do good and no one to do harm.”

Ms. Jarrett echoed that sentiment in a separate interview, saying that administration officials regularly meet with people they generally disagree with if they can find some common ground. “You have to be able to compartmentalize,” she said.

Mr. Obama on Thursday became the first sitting president to visit a federal prison, and has begun talking more openly about pushing an overhaul of the criminal code in his last months in office, one that would loosen tough-on-crime policies in place since the 1990s.

“These are young people who made mistakes that aren’t that different from the mistakes I made and the mistakes that a lot of you guys made,” Mr. Obama said after touring the El Reno Federal Correctional Institution in Oklahoma. “That’s what strikes me—there but for the grace of God.”

That has found Mr. Obama advocating for many of the same criminal-justice objectives as the Kochs, who have long urged revisiting how prosecutors bring cases, how defendants are represented and how sentences are decided, with the aim of making the system fairer.

The current mutual admiration stands in contrast to the warfare during recent elections. In 2012, the Koch-backed Americans for Prosperity launched a series of attack ads against the president. In the 2014 midterm elections, Democrats portrayed the Kochs as public enemy No. 1 in TV spots that aired tens of thousands of times, according to an analysis by Kantar Media Intelligence, a research firm.

“We had never before seen such a widespread, top-down effort to demonize any individual who wasn’t a candidate or elected official,” said Elizabeth Wilner, a Kantar senior vice president.

Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid (D., Nev.) has pursued his own anti-Koch campaign, delivering speeches on the Senate floor focused on “the shadowy influence of two power-drunk billionaires.” His office didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The decision to collaborate now is based on a hope that rallying support at both ends of the political spectrum will bolster their chance of success.

The improbable relationship traces back to a March summit focused on criminal justice. Mark Holden, senior vice president and general counsel of Koch Industries, who has led the company’s push on the subject, was speaking on a panel. Roy Austin Jr., a deputy assistant to the president who works on justice issues, was in the audience.

A few weeks later, an invitation from Mr. Austin brought Mr. Holden to the White House to explore the possibility of collaborating. Ms. Jarrett dropped by unscheduled to signal how important the effort was to the president, she said. At the meeting, she praised the brothers’ “Ban the Box” push, an effort to remove the box on job applications that applicants must check if they have a criminal record.

They continued their conversation in Aspen, where Ms. Jarrett also met David Koch. She described her interaction with Mr. Koch as “extremely cordial.” Charles Koch said he and his brother are “always leery if we disagree on many issues with somebody, just as they would be with us.” But he said their record on criminal justice should persuade the White House this is a priority.

For both the Kochs and the president, these issues are personal. A federal environmental criminal case in 2000 put the Koch brothers on the wrong end of a 97-count indictment charging the company, four employees and a subsidiary with violating environmental law at a Corpus Christi, Texas, refinery.

The charges were dropped against the employees. Koch Petroleum Group L.P. reached a plea agreement on one count, relating to an issue the company had voluntarily reported.

Mr. Holden said the thought was if a major firm such as Koch Industries could be targeted, “what was happening to the average person in the street?”

Now, the first black president and two Kansas billionaires hope to advance their shared agenda, raising the question: Could they team up on other issues?

“Who knows?” Ms. Jarrett said. “When we get this done, we’ll see.”

Updated: 6-5-2020

George Floyd Protesters Post For U.S. Justice System Reforms

Calls for sweeping changes to U.S. justice system continue; some cities move to cut funding for police.

Protesters planned to take to the streets again Friday, with calls on social media for one million demonstrators to gather in Washington, D.C., this weekend amid continued demands for reform to the American justice system sparked by the death of George Floyd.

Some U.S. cities tried to respond to protester demands. San Francisco joined Los Angeles in announcing a decision to curtail funding for police departments and invest instead in minority communities.

In Washington, D.C., Friday, Mayor Muriel Bowser formally renamed a section of 16th Street, just outside the White House, “Black Lives Matter Plaza” and had “Black Lives Matter” painted in giant yellow letters.

The city’s Black Lives Matter chapter on Twitter called the move “performative and a distraction” from demands “to decrease the police budget and invest in the community.”

The move came as Ms. Bowser and congressional Democrats are pushing back against federal law enforcement and military forces in the city, which isn’t a state and therefore doesn’t have the same power.

In a letter to President Trump dated Thursday, Ms. Bowser asked all outside law enforcement and military presence be removed from the city: “The protesters have been peaceful, and last night, the Metropolitan Police Department didn’t make a single arrest. Therefore, I am requesting that you withdraw all extraordinary federal law enforcement and military presence from Washington, D.C.”

“Equal justice under the law must mean that every American receives equal treatment in every encounter with law enforcement regardless of race, color, gender or creed,” Mr. Trump said during a press conference in the Rose Garden Friday. “Hopefully George Floyd is looking down right now and saying this is a great thing that’s happening for our country.”

Protesters in Manhattan planned to gather in various locations Friday to hold a vigil for Breonna Taylor, a black emergency-room technician whom Louisville, Ky., police fatally shot in her home in March. Ms. Taylor would have turned 27 years old Friday. Organizers have also planned marches, protests and vigils in the Bronx, Queens and Brooklyn, according to social media.

New York Police Department officials reported an uptick in arrests connected to the demonstrations in New York City Thursday night and Friday morning. That was up from 180 such arrests the previous day.

Many cities across the country had reported a decrease in arrests Thursday and some, such as Los Angeles and Washington, D.C., allowed curfews to expire.

The National Guard announced Friday morning an additional increase in troops. More than 41,500 soldiers and airmen had been activated in 33 states and Washington to assist for civil-unrest operations.

In addition to the D.C. National Guard, troops from 11 states have been activated in Washington, D.C.

On Thursday, thousands of mourners gathered in and around the chapel at North Central University in Minneapolis to memorialize Mr. Floyd, and the Rev. Al Sharpton called in his eulogy for protesters to “keep going until we change the whole system of justice.”

“It’s time for us to stand up in George’s name and say get your knee off our necks,” said Mr. Sharpton, who asked mourners to stand in silence for eight minutes and 46 seconds, the length of time Mr. Floyd lay pinned to the pavement.

Mr. Floyd, a 46-year-old black man, was killed on May 25 after police officers arrested him for allegedly trying to pass off a counterfeit $20 bill. Video that circulated widely on social media showed a white police officer, Derek Chauvin, with his knee on Mr. Floyd’s neck as he pleaded for mercy and said he couldn’t breathe.

Mr. Chauvin and three other officers were fired immediately. Mr. Chauvin has since been charged with second and third-degree murder and the other three officers have been charged with aiding and abetting second-degree murder.

A judge in Minneapolis on Thursday set the bail at $750,000 for the three ex-officers charged with aiding and abetting second-degree murder in the killing of Mr. Floyd, the Associated Press reported. Only five news organizations were allowed into the courtroom amid constraints imposed due to the new coronavirus.

None of the officers entered a plea, as expected for a first court appearance, according to the AP. Judge Paul Scoggin set June 29 as their next court date.

Meanwhile, two police officers in Buffalo, N.Y., were suspended without pay after knocking down a 75-year-old man Thursday in an incident caught on a widely shared video, Mayor Byron W. Brown said on Twitter. The event came after a conflict between two groups of protesters who were out beyond curfew, said Mr. Brown, who added that he was “deeply disturbed by the video.”

In New York Thursday, thousands gathered for a memorial for Mr. Floyd, organized by some of his family, in Cadman Plaza Park in Brooklyn and then marched across the Brooklyn Bridge. Protesters carried signs that said “Black lives matter” and chanted, “No justice, no peace.”

New York Mayor Bill de Blasio received scattered boos, as he promised change. “It will not be about words in this city. It will be about change,” he said, leaving shortly after.

At Union Square later in the day, a crowd of about 400 protesters stood chanting “George Floyd” and “No justice, no peace” to the thumping of drums and hands clapping.

Roberto Escobar, a U.S. citizen who was born in El Salvador, has been coming out from Harlem to protest for three nights. He and his wife had initially held off on joining because they were concerned that coronavirus posed too much of a risk. But the 38-year-old decided he couldn’t stay silent.

“We go through a lot of discrimination with police as well,” he said, referring to Latinos. “There is a need for people to change how they look at people of color.”

In Chicago, the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office said Thursday it would investigate a family’s allegation that a young woman was pulled out of her car at a looted mall, thrown to the ground and subdued by an officer who put his knee on her neck.

Police said the woman, Mia Wright, had assembled with three others for the purpose of using force or violence to disturb the peace and that she had been charged with disorderly conduct.

In downtown Los Angeles on Thursday, about 1,000 people gathered, some holding signs reading “The fight ain’t over” and “Disarm the police,” as they listened to speeches condemning police brutality. There were fewer police around City Hall than in previous days, but a large contingent of National Guard troops encircled the Los Angeles Police Department headquarters.

Toyna Panton, one of the demonstrators, said police budget cuts announced by Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti weren’t adequate. Nearby, 37-year-old Kristen Fraser said the cuts were a step in the right direction. She attributed the move as well as the newly announced policies regarding police misconduct to the past week’s protests. “If no one said anything or put a light on it, nothing would have happened,” she said.

A thunderstorm that passed through Washington, D.C., Thursday just after 8 p.m. didn’t deter some protesters from marching near the White House, where security has been beefed up with additional fencing around the perimeter.

Earlier, some protesters marched to the Lincoln Memorial, where they listened to speeches until the rain started. The demonstration was leaderless and peaceful, and police cleared traffic for the marchers, as they wound through the streets.

“I was marching, and someone handed me a megaphone,” said Hilda M. Jordan, 22. Wearing a mask on which she had scrawled the words “no justice, no peace,” Ms. Jordan led the crowd in repeating the names of African-Americans who had died in police custody.

At the memorial service for Mr. Floyd Thursday, Mr. Sharpton said the colors of the faces of the young people on the streets protesting had given him hope. In many instances, he saw more white people than black people.

His remarks came a few moments after several siblings and cousins remembered Mr. Floyd as a bear of a man who was kind and humble and could polish off six pieces of chicken at a sitting. The family was so poor they had to wash their clothes in the sink and hang them over the hot-water heater to dry. But the household was warm and loving, his brother said. His mother regularly took in Mr. Floyd’s friends for long periods.

“That is where he got his character,” said Jeanette Sledge, who listened to the service on her car radio and came out to be part of a crowd of at least a thousand to watch the family leave the chapel and show her support.

Sobs rang out across the chapel as mourners stood in silence for eight minutes and 46 seconds, the amount of time Mr. Chauvin had his knee on Mr. Floyd’s neck.

“I listened to that and I started to cry,” Ms. Sledge said. “It was such a long time. I imagined myself running in to get the police off him.”

Updated: 8-2-2021

Removing Barriers To Success Created By The Criminal Justice System

For people who have served prison time, the penalties never end.

The California-based national nonprofit Alliance for Safety and Justice (ASJ) coined a term to describe what many of these people face: post-conviction poverty.

After completing a sentence, and being freed from prison, a formerly convicted individual encounters thousands of restrictions depending on where they live that make it challenging to reintegrate into society. They may not be able to vote, get a driver’s license, or, critically, get a job in a range of fields that require licensing, such as insurance, real estate, or even haircutting.

“A million people get convicted every year,” says Jay Jordan, ASJ’s vice president. And that means, “we’re putting one million people in poverty every year.”

ASJ has successfully lobbied to change laws in several states and has raised awareness, while helping to form communities of crime victims and also of formerly convicted individuals in eight states. In recent months, the group received funding and support from the just launched Justice and Mobility Fund that will allow them to deepen their current work and expand to more states.

The fund is a collaborative effort of the Ford Foundation, Blue Meridian Partners, and the Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Philanthropies, which together have pledged US$250 million to boost the economic mobility of 77 million Americans—about one third of all adults—who have been caught in the criminal justice system.

“The initiative is an effort to bring large-scale capital to a social justice enterprise,” says Tanya Coke, director of the gender, racial, and ethnic justice program at Ford.

Together the organizations have granted US$145 million so far to six national organizations, which include ASJ, the Center for Employment Opportunities (CEO), the Vera Institute of Justice, the Clean Slate Initiative, Jobs for the Future, and the Center for Policing Equity, and two state-based initiatives, the Michigan Justice Fund and the Oklahoma Justice Fund.

The funding provided to these nonprofits (about US$20 million on average) is intended to be transformative—by providing significant resources to allow them to grow and thrive—and supportive, in that Blue Meridian, which is a collaboration of several major foundations, provides strategic-planning guidance and support to ensure the targeted groups create clear, achievable goals.

The dollars committed so far are invested in initiatives across the spectrum of the criminal justice system. “At every stage there are places where we see future economic mobility for justice-involved people directly at risk,” Coke says.

The fact of an arrest and a conviction “makes it harder for people to access jobs, housing, public benefits,” she says. “A felony conviction, in particular, can be a life sentence, and devastating to one’s economic prospects. We also know there are fees and fines that attach to criminal convictions and that often dog people for decades and make it difficult for them to make child support payments, pay rent, invest in businesses.”

At each of these points, there are interventions that could reduce the barriers for individuals who have been in touch with the justice system, Coke adds, “and that’s really the aim of the fund.”

Because there is no single organization addressing all the ways the criminal justice system affects lives, Ford, Blue Meridian, and Schusterman Family Philanthropies sought organizations tackling “critical touch points across the system where justice reforms would be most conducive to addressing issues of economic mobility,” says Mindy Tarlow, managing director of portfolio strategy and management at Blue Meridian.

“No Silver Bullet”

They looked for groups offering “synergies between policy and advocacy, narrative change, [and] direct service,” with the goal of building a portfolio of organizations that would compliment one another and achieve the fund’s goals. “There’s no silver bullet here,” Tarlow says.

One focus of their efforts is to remove barriers for the 77 million Americans with a criminal record, a goal of both ASJ and a national initiative directed by Jordan called Time Done, and of the Clean Slate Initiative.

CEO, instead, works directly with the several hundred thousand people who come home from prison every year to address their immediate needs, and to give them support and training to get a job. During the pandemic, when many incarcerated individuals were sent home to avoid contracting the virus within prisons, the New York-based group gave these “returning citizens” up to US$2,750 in three cash payments—an amount significant enough for them to take initial steps for getting their lives in order.

“We are also looking through this whole portfolio [of investments] to change the narrative—to change the attitudes and behaviors of stakeholders that matter,” Tarlow says. “Employers, as an example—we want to see many more employers hire justice-involved people. We are trying to establish a strategy that will help that happen.”

And, Tarlow adds, the members of the fund expect to show they are building “stronger organizations, that not just have more money, but a strategic plan they can follow” and that will allow them to pivot, when needed, and think beyond the six months in front of them.

“We’re giving these fantastic leaders the opportunity to think ahead, to have the infrastructure they need to act and to pursue innovations and visions for an era where hiring justice-involved people is a norm,” she says.

The three-year strategic plan that Blue Meridian developed with ASJ includes measures to strengthen the group from a startup housed within the Tides Center, a California foundation that supports social ventures as they are starting out, to a self-sustaining nonprofit “with robust internal capacity and enhanced multi-state support” to sustain and grow its work.

The plan also seeks to expand ASJ’s impact by growing the number of members in its 3-year-old Time Done initiative from 40,000 to 300,000.

Building the plan alongside Blue Meridian and the Bridgespan Group, a Boston-based philanthropic advisory firm, allowed ASJ to think through issues, and to get support, without having their hands held. “It was one of the most tremendous, community-led processes I’ve been through in my life,” Jordan says.

This investment in ASJ, and Time Done, “allows us to build a community for us, by us,” and, as Jordan notes, he’s part of that community. Sixteen years ago he left prison after a seven-and-a-half year stint. Although Jordan found a successful path back into society, legal barriers continue to constrict what he can do, including adopting a child with his wife or coaching his son’s Little League team, he says.

With the fund’s support, Time Done can support the direct needs of individuals struggling to get back on their feet, to assist them in reintegrating.

“Once we do that, then we create fully functional citizens,” Jordan says. “That’s what is not happening.”

Jordan’s experience resonates with funders such as Schusterman Family Philanthropies, which is part of the Justice and Mobility Fund collaboration, and which also pursues its own separate criminal justice initiatives.

David Weil, co-president of the foundation, says he hopes society is recognizing that “more police, more incarceration, more punishment” is part of a unique U.S. system “that in many ways doesn’t keep us safe, but continues to create harm.”

Given the multi-faceted nature of reform, and the fact many of the problems and solutions are very local, nothing will be solved overnight.

“This was created over a long period of time, in many many small steps, and that’s going to have to be the way we find our way back out to a more just result,” Weil says.

Related Articles:

Hundreds of Police Killings Go Undocumented By Law Enforcement And FBI (#GotBitcoin?)

The FBI’s Crime Data: What Happens When States Don’t Fully Report (#GotBitcoin?)

Citizens Cannot Turn The Police Away If They Are Unhappy With Their Services (#GotBitcoin?)

Before Leaving, Sessions Limited Agreements To Fix Police Agencies (#GotBitcoin?)

Mobile Justice App. (#GotBitcoin?)

SMART-POLICING, COMPETITION AND WHY YOU SHOULD CARE (PART I, Video Playlist)

Citizen Surveillance Is Playing A Major Role In Terrorist And Other Criminal Investigations

Our Facebook Page

Your Comments Are Greatly Appreciated.

Monty

Go back

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.