Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature Touting Its Lower-Priced Products Over Resellers (#GotBitcoin?)

Amazon.com Inc. tested a pop-up feature on its app that in some instances pitched its private-label goods on rivals’ product pages, an experiment that shows the e-commerce giant’s aggressiveness in hawking lower-priced products including its own house brands. Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature Touting Its Lower-Priced Products Over Resellers

Experiment in mobile app forced customers to either click through or dismiss pop-ups.

The recent experiment, conducted in Amazon’s mobile app, went a step further than the display ads that commonly appear within search results and product pages. This test pushed pop-up windows that took over much of a product page, forcing customers to either click through to the lower-cost Amazon products or dismiss them before continuing to shop.

When a customer using Amazon’s mobile app searched for “AAA batteries,” for example, the first link was a sponsored listing from Energizer Holdings Inc. After clicking on the listing, a pop-up window appeared, offering less expensive AmazonBasics AAA batteries.

The limited experiment, which ended last week, highlights the power Amazon holds over brands on its home turf. In its quest to offer the best selection at the lowest price, Amazon has created more than a hundred in-house brands, from batteries and trash bags to nutritional supplements and furniture.

Amazon’s private-label brands have chipped away at market share in some categories, such as batteries, and the company actively advertises its products throughout the site. Consumer-product manufacturers have found Amazon increasingly important because the website accounts for roughly half of all U.S. sales online.

The test, which didn’t appear on every customer’s mobile device, ran on top of both sponsored and non-sponsored listings. Amazon also said it pitched lower-cost alternatives from other brands, but it didn’t specify which ones.

Amazon said the pop-up windows weren’t ads, but rather a test of a feature to help shoppers find cheaper alternatives. The group that developed the test was from Amazon’s retail business, not its advertising operations. The company declined to discuss the results of the experiment.

“We regularly experiment with new shopping experiences for customers, and this was a small test,” the company said. “The similar, lower-priced product options shown to customers featured relevant items from a range of brands on our website and were displayed when a customer clicked on any type of listing.”

The Wall Street Journal last week conducted dozens of product searches in a variety of categories in the mobile app, clicking on the first several products listed including those from Amazon. The Journal found three instances of the pop-up ads, which took up about half of a nearly 6-inch iPhone screen and which all touted Amazon products on rival pages. The ads didn’t show on several other phones tested under different user accounts.

One company whose sponsored-listing page was targeted, Nested Naturals Inc., only found out about the test through social media, its co-founder and chief marketing officer, Kevin Pasco, said.

Before mobile shoppers included in the experiment could buy Luna sleeping pills from the Vancouver-based supplement company for $21.95, they were offered a pop-up window hawking an $11.99 vial of melatonin pills from Amazon Elements. The pop-up included the tag “Similar item, lower price” with a link to the Amazon product.

Mr. Pasco described the tactic as “sneaky,” though he said building a business on Amazon requires “having a stomach of steel and taking whatever they throw at us.”

Nested Naturals sold about $10 million of its supplements on Amazon last year, roughly 85% of its business, he said. That makes it easier to roll with Amazon’s efforts to compete against Nested Naturals, Mr. Pasco said. The experiment, he added, had no discernible impact on Luna sales.

“We try to be a little less emotional and say this is Amazon being Amazon,” Mr. Pasco said.

In the Energizer example, Amazon’s pop-up appeared in a sponsored listing for a 24-pack of MAX Premium AAA batteries priced at $12.14. The rival 36-count AmazonBasics batteries cost $8.99.

An Energizer spokeswoman declined to comment.

Another target of Amazon’s test was Clorox Co.’s Glad Products Co. and its 110-count of tall kitchen trash bags for $19.06. The pop-up touted Amazon’s Solimo bags for $14.49. A Clorox spokeswoman didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Like many big-box retailers in physical stores, Amazon is taking premium space to sell its own generic products. But unlike placing generic acetaminophen on a shelf next to Tylenol, Amazon’s test forced consumers to dismiss the option of viewing alternatives before they could continue with a purchase.

Amazon declined to say if it notified the advertisers when the test usurped sponsored listings or if it refunded sponsored-ad payments.

The company is increasingly finding ways to monetize the space on its website, especially as it forges deeper into the advertising business. Shoppers are encountering a variety of sponsored ads, whether at the top of search results with sponsored listings that look similar to regular listings, or within product pages in a number of formats.

Last fall, The Wall Street Journal reported that Amazon for more than a year wove sponsored product listings from Johnson & Johnson and Kimberly-Clark Corp. , onto consumers’ baby registries that led some shoppers into believing the new parents had chosen the items. Amazon said it has since phased out the sponsored listings on the baby registries.

Amazon’s sales of private-label goods on its website received increased scrutiny last week when Sen. Elizabeth Warren, a Massachusetts Democrat running for president, proposed banning large companies from participating in the platforms they have created. She specifically called for splitting AmazonBasics from the company’s marketplace business.

Updated: 4-23-2020

Amazon Scooped Up Data From Its Own Sellers to Launch Competing Products

Contrary to assertions to Congress, employees often consulted sales information on third-party vendors when developing private-label merchandise

Amazon.com Inc. employees have used data about independent sellers on the company’s platform to develop competing products, a practice at odds with the company’s stated policies.

The online retailing giant has long asserted, including to Congress, that when it makes and sells its own products, it doesn’t use information it collects from the site’s individual third-party sellers—data those sellers view as proprietary.

Yet interviews with more than 20 former employees of Amazon’s private-label business and documents reviewed reveal that employees did just that. Such information can help Amazon decide how to price an item, which features to copy or whether to enter a product segment based on its earning potential, according to people familiar with the practice, including a current employee and some former employees who participated in it.

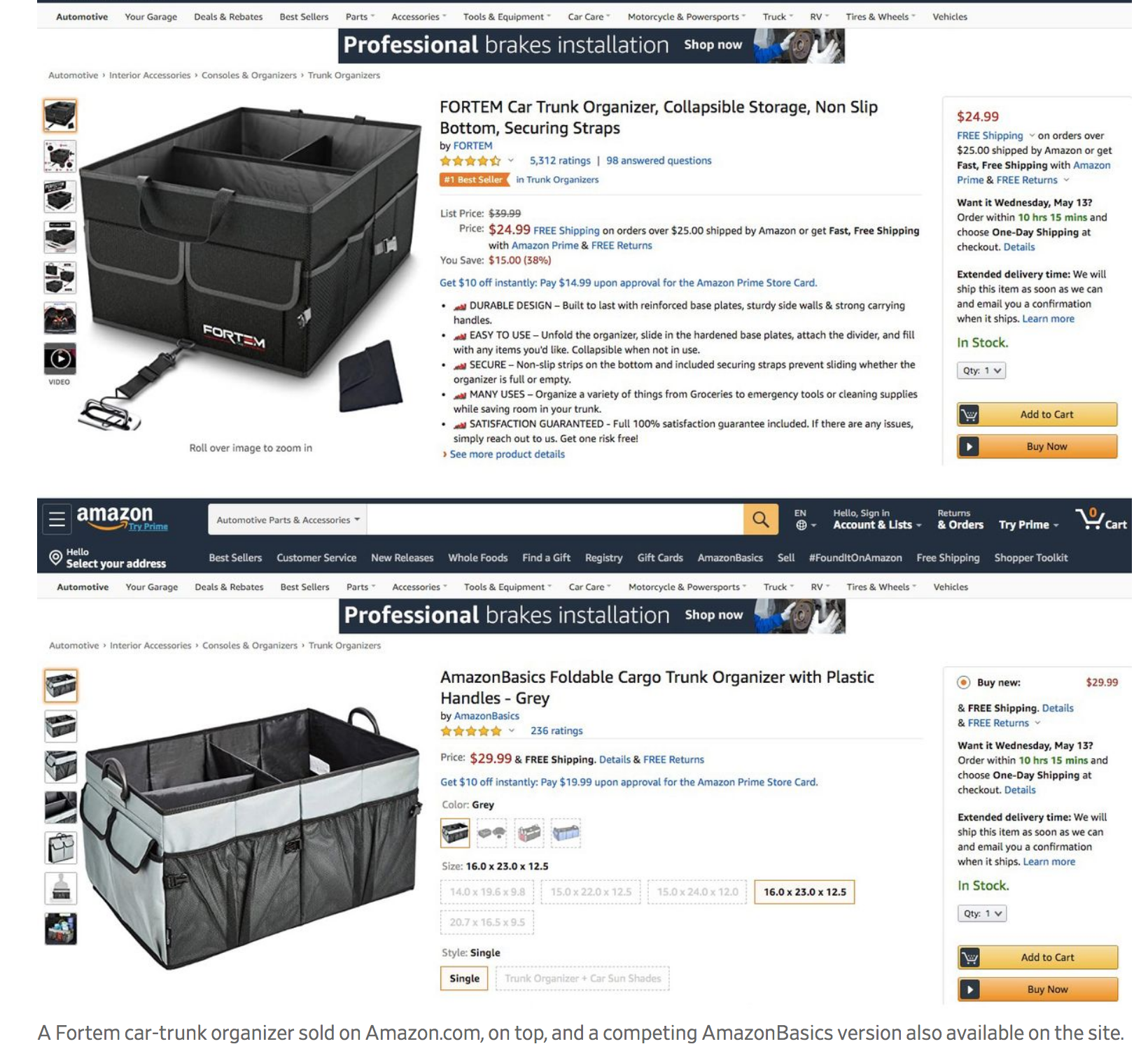

In one instance, Amazon employees accessed documents and data about a bestselling car-trunk organizer sold by a third-party vendor. The information included total sales, how much the vendor paid Amazon for marketing and shipping, and how much Amazon made on each sale. Amazon’s private-label arm later introduced its own car-trunk organizers.

“Like other retailers, we look at sales and store data to provide our customers with the best possible experience,” Amazon said in a written statement. “However, we strictly prohibit our employees from using nonpublic, seller-specific data to determine which private label products to launch.”

Amazon said employees using such data to inform private-label decisions in the way the Journal described would violate its policies, and that the company has launched an internal investigation.

Nate Sutton, an Amazon associate general counsel, told Congress in July: “We don’t use individual seller data directly to compete” with businesses on the company’s platform.

It is a common business strategy for grocery chains, drugstores and other retailers to make and sell their own products to compete with brand names. Such private-label items typically offer retailers higher profit margins than either well-known brands or wholesale items.

While all retailers with their own brands use data to some extent to inform their product decisions, they have far less at their disposal than Amazon, according to executives of private-label businesses, given Amazon’s enormous third-party marketplace.

The coronavirus pandemic has enabled Amazon to position itself as a national resource capable of delivering needed goods to Americans sheltering in place, garnering it goodwill in Washington. The company continues, however, to face regulatory inquiries into its practices that predate the crisis.

Last year, the European Union’s top antitrust enforcer said that it was investigating whether Amazon is abusing its dual role as a seller of its own products and a marketplace operator and whether the company is gaining a competitive advantage from data it gathers on third-party sellers.

The Justice Department, Federal Trade Commission and Congress also are investigating large technology companies, including Amazon, on antitrust matters. Amazon is facing scrutiny over whether it unfairly uses its size and platform against competitors and other sellers on its site.

Amazon disputes that it abuses its power and size, noting that it accounts for a small proportion of overall U.S. retail sales, and that the use of private-label brands is common in retail.

Amazon has said it has restrictions in place to keep its private-label executives from accessing data on specific sellers in its Marketplace, where millions of businesses from around the globe offer their goods. In interviews, former employees and a current one said those rules weren’t uniformly enforced. Employees found ways around them, according to some former employees, who said using such data was a common practice that was discussed openly in meetings they attended.

“We knew we shouldn’t,” said one former employee who accessed the data and described a pattern of using it to launch and benefit Amazon products. “But at the same time, we are making Amazon branded products, and we want them to sell.”

Some executives had access to data containing proprietary information that they used to research bestselling items they might want to compete against, including on individual sellers on Amazon’s website. If access was restricted, managers sometimes would ask an Amazon business analyst to create reports featuring the information, according to former workers, including one who called the practice “going over the fence.”

In other cases, supposedly aggregated data was derived exclusively or almost entirely from one seller, former employees said.

Amazon draws a distinction between the data of an individual third-party seller and what it calls aggregated data, which it defines as the data of products with two or more sellers. Because of the size of Amazon’s marketplace, most products have many sellers. Viewing the data of a product with a number of sellers wouldn’t give it insight into proprietary seller information because the figures would show lots of different seller behavior.

Amazon said that if there is only one seller of an item, and Amazon is selling returned or damaged versions of that item through its Amazon Warehouse Deals clearance account, Amazon considers that “aggregate” data—and hence is permissible for its employees to review.

Amazon’s private-label business encompasses more than 45 brands with some 243,000 products, from AmazonBasics batteries to Stone & Beam furniture. Amazon says those brands account for 1% of its $158 billion in annual retail sales, not counting Amazon’s devices such as its Echo speakers, Kindle e-readers and Ring doorbell cameras.

Former executives said they were told frequently by management that Amazon brands should make up more than 10% of retail sales by 2022. Managers of different private-label product categories have been told to create $1 billion businesses for their segments, they said.

Amazon has a history of difficult relationships with sellers, especially those that choose not to sell their products on its site.

While some of the issues have involved counterfeit goods or frustration about lack of pricing control on their products, another concern for some is that Amazon would use data they accumulate to copy the products and siphon sales.

Because 39% of U.S. online shopping occurs on Amazon, according to research firm eMarketer, many brands feel they can’t afford not to sell on the platform. In a recent survey from e-commerce analytics firm Jungle Scout, more than half of over 1,000 Amazon Marketplace sellers said Amazon sells its own products that directly compete with the seller’s products.

“We had a brand say they wanted to sell exclusively on Walmart, and when we proposed Amazon, they said they don’t want to risk private-label copying their product,” said Kunal Chopra, the CEO of etailz, which helps vendors sell across platforms.

Early last year, an Amazon private-label employee working on new products accessed a detailed sales report on a car-trunk organizer manufactured by a third-party seller called Fortem, a four-person, Brooklyn-based company run by two 29-year-olds.

That employee showed the report to the Journal. More than 33,000 units of the organizer were sold during the 12 months covered in the report, according to a copy reviewed by the Journal. The report has 25 columns of detailed information about Fortem’s sales and expenses.

Fortem accounted for 99.95% of the total sales on Amazon for the trunk organizer for the period the documents cover, the data indicate. Oleg Maslakou, one of Fortem’s founders, said “no one is selling the Fortem organizer besides us and Amazon Warehouse deals,” a resale clearance account of returned or damaged goods from Fortem. “You hit us with a big surprise,” he said after reviewing the data Amazon’s private-label employee had on his brand.

Amazon said that there was one other seller of Fortem’s trunk organizer during the period of the data the Journal reviewed. It wouldn’t comment on how many days that seller was active or how many sales it made. The Journal reached the other seller of the Fortem trunk organizer, who said for the period of time, he sold only 17 units of the item.

Fortem’s own sales and a slight number of its own damaged goods and returns sold through Amazon’s Warehouse Deals account accounted for nearly 100% of the more than 33,000 sales of the unit during the period, the data show.

The data in the report reviewed by the Journal showed the product’s average selling price during the preceding 12 months was about $25, that Fortem had sold more than $800,000 worth in the period specified, and that each item generated nearly $4 in profit for Amazon.

The report also detailed how much Fortem spent on advertising per unit and the cost to ship each trunk organizer, according to the documents and former Amazon employees who explained their contents.

“We would work backwards in terms of the pricing,” said one of the people who used to obtain third-party data. By knowing Amazon’s profit-per-unit on the third-party item, they could ensure that prospective manufacturers could deliver a higher margin on an Amazon-branded competitor product before committing to it, said another person who accessed the data.

Fortem launched its trunk organizer on Amazon’s Marketplace in March 2016, and it eventually became the No. 1 seller in the category on Amazon. In October 2019, Amazon launched three trunk organizers similar to Fortem’s under its AmazonBasics private-label brand.

The Fortem trunk organizer detailed in the documents is still a bestseller in the category, Amazon noted. Fortem spends as much as $60,000 a month on Amazon advertisements for its items to come up at the top of searches, said Mr. Maslakou.

Pulling data on competitors, even individual sellers, was “standard operating procedure” when making products such as electronics, suitcases, sporting goods or other lines, said the person who shared the Fortem documentation. Such reports were pulled before Amazon’s private label decided to enter a product line, the person said.

“Customers’ shopping behavior in our store is just one of many inputs to Amazon’s private-label strategy,” said Amazon. Other factors include fashion and shopping trends and suggestions from manufacturers, it said.

Amazon employees also accessed sales data from Austin-based Upper Echelon Products, according to the data reviewed by the Journal. Its office-chair seat cushion is a popular seller on Amazon. An Amazon private-label employee pulled a year’s worth of Upper Echelon data when researching development of an Amazon-branded seat cushion, according to the person who shared the data.

An Amazon employee pulled the data early last year. Last September, AmazonBasics launched its own version.

After the Journal disclosed the contents of the sales report to Travis Killian, CEO of seven-person Upper Echelon, he said: “It’s not a comfortable feeling knowing that they have people internally specifically looking at us to compete with us.”

Amazon said there were more than two dozen sellers of the Upper Echelon seat cushion during the period, but declined to specify how many units those sellers sold. Mr. Killian said if that were the case, he isn’t sure how the private-label data on his seller account provided to the Journal matched his internal sales data so perfectly.

In traditional retail, a company such as Target Corp. or Kroger Co. places a weekly purchase order with the brands on its shelves. It subsequently owns the inventory, setting the price and discounts.

Because of the limitations of shelf space, traditional retailers stock far fewer products than Amazon’s hundreds millions of items. Typically, they create private-label products to compete in generic categories such as paper towels, rather than copycat versions of items created by smaller entrepreneurs, private-label executives said. Amazon said the vast majority of its private-label sales are staples such at batteries and baby wipes.

The majority of Amazon’s sales—58%—come through third-party sellers, primarily small and medium-size firms that list their items for sale on Amazon’s Marketplace platform. (Amazon also buys items directly from manufacturers and sells them directly in “first-party” sales.)

Amazon started making its own products in 2007 with its Kindle e-reader, and it has steadily added new categories and other private-label brand names. Some of its private-label products, such as batteries, have been home runs. Investment firm SunTrust Robinson Humphrey estimates Amazon is on track to post $31 billion in private-label sales by 2022, or nearly double retailer Nordstrom Inc.’s 2019 revenues.

Updated: 4-28-2020

Senator Pushes DOJ To Open Criminal Investigation Into Amazon

Sen. Josh Hawley requests antitrust probe of Amazon’s use of third-party seller data.

A senator is pushing the Justice Department to open a criminal antitrust investigation into Amazon. AMZN -2.61% com Inc. after a Wall Street Journal report detailed the company’s use of third-party seller data to develop its products.

In a letter addressed to Attorney General William Barr, Sen. Josh Hawley (R., Mo.) urged the Justice Department to “open a criminal antitrust investigation of Amazon.” He said recent reports suggest the company “has engaged in predatory and exclusionary data practices to build and maintain a monopoly.” Mr. Hawley said the department should look at Amazon’s position as an online platform that also creates products that compete with its third-party sellers.

Last week, on the day the Journal’s report ran, a top congressional committee investigating technology companies questioned whether Amazon misled Congress in sworn testimony from July. At the time, an Amazon associate general counsel told Congress: “We don’t use individual seller data directly to compete” with businesses on the company’s platform.

“Amazon abuses its position as an online platform and collects detailed data about merchandise so Amazon can create copycat products under an Amazon brand. Internal documents and the testimony of more than 20 former Amazon employees support this finding,” Mr. Hawley said in the letter Tuesday.

The Journal found that Amazon employees accessed proprietary data about individual sellers on its site to research and develop competing Amazon-branded products, according to documents and interviews with more than 20 employees of the company’s private-label business.

Amazon has launched an internal investigation into the matter, and the company said employees using such data to inform private-label decisions would violate its policies. In response to previous antitrust scrutiny, Amazon has said it follows all laws and has emphasized that it accounts for less than 4% of the U.S. retail market.

The Justice Department last year launched a broad investigation of the market power of large technology companies, including Amazon. The Federal Trade Commission, the other agency that enforces U.S. antitrust laws, has also dedicated a team of lawyers in its antitrust office to focus on tech firms.

Officials in both departments have met with Amazon’s retail competitors, with the FTC more actively keeping tabs on the company, people familiar with the matter have said. But probes into other tech firms appear to be more advanced. Amazon hasn’t disclosed receiving formal investigative inquiries from either the Justice Department or the FTC, as have both Facebook Inc. and Google parent Alphabet Inc.

An antitrust case, if Mr. Barr decided to launch one, might take years to run its course and would surely meet stiff opposition from the company. Most antitrust enforcement actions are civil, with criminal actions generally limited to overtly anticompetitive actions such as price-fixing. A criminal case could in theory lead to monetary penalties or even jail time for individuals if the government proved they intentionally violated antitrust laws.

Mr. Hawley took office in 2019 and has distinguished himself as one of Washington’s harshest critics of large technology firms. During President Trump’s “Social Media Summit” bashing Google, Facebook and others at the White House last year, Mr. Trump praised Mr. Hawley and invited him on stage.

Mr. Trump often takes aim at Amazon, questioning the taxes it pays, the rates it pays the U.S. Postal Service and its efforts to win a multibillion-dollar Pentagon cloud-computing contract. He has blamed Amazon founder Jeff Bezos for articles published by the Washington Post, which Mr. Bezos owns. The Post has said its editorial decisions are independent.

Updated: 6-11-2020

Amazon to Face Antitrust Charges From EU Over Treatment of Third-Party Sellers

Charges are set to accuse Amazon of scooping up data from third-party sellers and using that information to compete against them.

The European Union is planning formal antitrust charges against Amazon. AMZN -3.38% com Inc. over its treatment of third-party sellers, according to people familiar with the matter, expanding the bloc’s efforts to rein in the alleged abuses of power by a handful of large U.S. technology companies.

The charges—the EU’s first set of formal antitrust accusations against the company—could officially be filed as early as next week or the week after, one of the people said. The European Commission, the bloc’s top antitrust regulator, has been honing its case, and the case team has been circulating a draft of the charge sheet for a couple of months, another person said.

The formal charges, which would come at the same time as Amazon and other tech firms face increased scrutiny in the U.S., would be the commission’s latest step in a nearly two-year probe into Amazon’s alleged mistreatment of sellers that use its platform. The charges—called a statement of objections—stem from Amazon’s dual role as a marketplace operator and a seller of its own products, the people said. In them, the EU accuses Amazon of scooping up data from third-party sellers and using that information to compete against them, for instance by launching similar products.

Amazon declined to comment. It has previously disputed that it abuses its power and size and said that retailers commonly sell their own private-label brands.

A decision by the commission on whether Amazon broke competition laws is expected to take at least another year. If the company is found in violation, the commission can force Amazon to change business practices and fine it as much as 10% of its annual global revenue—or as much as $28 billion based on 2019 figures.

Amazon can challenge any such decision in an EU court.

For the past year, U.S. authorities have also been probing Amazon’s alleged anticompetitive behavior. The Justice Department, Federal Trade Commission and Congress are investigating large technology companies, including Amazon, on antitrust matters. Amazon is facing scrutiny over whether it unfairly uses its size and platform against competitors and other sellers on its site.

A Wall Street Journal investigation published in April found that employees at the online retailer at times used data from other sellers to develop competing products. According to former workers, the company sometimes asked an Amazon business analyst to create reports featuring restricted information or using supposedly aggregated data that was derived exclusively or almost entirely from one seller.

The EU’s case delves into the same types of conduct, the people familiar with the matter said.

Following the Journal article, a top congressional committee questioned whether Amazon misled Congress in sworn testimony last year, when an executive denied using “individual seller data directly to compete” with other businesses on the platform. Lawmakers have said Amazon hasn’t fully responded to requests for information about its relationship to sellers. “Seven months after the original request—significant gaps remain,” a letter to the company said.

Amazon launched an internal investigation, and said that employees using such data to inform private-label decisions would violate its policies.

In Europe, Amazon’s alleged behavior is seen as part of a pattern by online platforms to use data to quash rivals. Last year, Margrethe Vestager, the European Commission’s vice president in charge of competition and digital policy, launched similar probes into Alphabet Inc.’s Google and Facebook Inc. The two companies have said they are cooperating with the inquiries.

Ms. Vestager has in recent years fined Google over $9 billion for anticompetitive behavior in three separate probes. The cases cover accusations the company used its search engine to steer traffic to its own product ads over rivals’, and that it used the control of its Android operating system to force device makers to install its cash-cow search engine onto Android devices. Google is appealing the decisions in the EU’s General Court, the bloc’s second-highest court.

Critics, such as competing search engines, have argued that large fines have done little to blunt Google’s power, however. Ms. Vestager has admitted publicly that fines alone “are not doing the trick” and that reigning in tech giants may require new powers and regulations. She plans to put forward regulatory proposals by the end of the year, including powers for the commission to order changes in business practices before a dominant platform quashes its competitors, she has said.

“Our competition enforcement has taught us a lot about the sort of behavior by dominant platforms that can stop the markets which they regulate from working well,” Ms. Vestager said in a speech in March. “And we can draw on that experience to design regulations that clearly set out what those platforms can do with their power—and what they can’t.”

While these would be the EU’s first antitrust charges leveled against Amazon, the company has been in the EU’s sights before. In 2017, Amazon settled an EU investigation into its e-book contracts with publishers. That same year, the EU also ordered Luxembourg to recoup €250 million from the e-commerce company under the bloc’s state-aid rules, saying that the Grand Duchy had granted the e-commerce giant illegal state aid in the form of a sweetheart tax deal.

Amazon has appealed that decision in the EU’s General Court, where it described the commission’s findings as “without merit.”

Updated: 7-23-2020

Amazon Met With Startups About Investing, Then Launched Competing Products

Some companies regret sharing information with tech giant and its Alexa Fund; ‘we may have been naive’.

When Amazon.com Inc.’s venture-capital fund invested in DefinedCrowd Corp., it gained access to the technology startup’s finances and other confidential information.

Nearly four years later, in April, Amazon’s cloud-computing unit launched an artificial-intelligence product that does almost exactly what DefinedCrowd does, said DefinedCrowd founder and Chief Executive Daniela Braga.

The new offering from Amazon Web Services, called A2I, competes directly “with one of our bread-and-butter foundational products” that collects and labels data, said Ms. Braga. After seeing the A2I announcement, Ms. Braga limited the Amazon fund’s access to her company’s data and diluted its stake by 90% by raising more capital.

Ms. Braga is one of more than two dozen entrepreneurs, investors and deal advisers interviewed by The Wall Street Journal who said Amazon appeared to use the investment and deal-making process to help develop competing products.

In some cases, Amazon’s decision to launch a competing product devastated the business in which it invested. In other cases, it met with startups about potential takeovers, sought to understand how their technology works, then declined to invest and later introduced similar Amazon-branded products, according to some of the entrepreneurs and investors.

An Amazon spokesman said the company doesn’t use confidential information that companies share with it to build competing products.

Dealing with Amazon is often a double-edged sword for entrepreneurs. Amazon’s size and presence in many industries, including cloud-computing, electronic devices and logistics, can make it beneficial to work with. But revealing too much information could expose companies to competitive risks.

“They are using market forces in a really Machiavellian way,” said Jeremy Levine, a partner at venture-capital firm Bessemer Venture Partners. “It’s like they are not in any way, shape or form the proverbial wolf in sheep’s clothing. They are a wolf in wolf’s clothing.”

Former Amazon employees involved in previous deals say the company is so growth-oriented and competitive, and its innovation capabilities so vast, that it frequently can’t resist trying to develop new technologies—even when they compete with startups in which the company has invested.

Drew Herdener, an Amazon spokesman, said that “for 26 years, we’ve pioneered many features, products, and even whole new categories. From amazon.com itself to Kindle to Echo to AWS, few companies can claim a record for innovation that rivals Amazon’s.

Unfortunately, there will always be self-interested parties who complain rather than build. Any legitimate disputes about intellectual property ownership are rightly resolved in the courts.”

In February, the Federal Trade Commission ordered five large technology companies, including Amazon, to provide details on certain investments and acquisitions from 2010 through 2019 to determine whether any of the deals were anticompetitive. The FTC declined to comment on the status of that review.

Amazon also is facing scrutiny from Congress, the FTC and the Justice Department over whether it unfairly uses its size and platform against competitors and other sellers on its site. Amazon Chief Executive Jeff Bezos and fellow technology CEOs are scheduled to testify to Congress on Monday about their companies’ business practices.

In April, the Journal reported that Amazon employees on the private-label side of its business have used data about individual third-party sellers on its site to create competing products. Amazon said it was conducting an internal investigation into the practices described in the story.

Amazon takes stakes in some startups and acquires others outright. Many investments are made through its Alexa Fund, an investment vehicle launched in 2015 after Amazon unveiled a line of smart speakers that became a runaway technology hit. The fund aims to support companies involved in voice technology.

In one instance, an investment from the Alexa Fund led to an acquisition. The fund made an investment in smart-doorbell maker Ring in 2016, then bought the company in 2018.

“Our constant collaboration and joint innovation with the Alexa [Amazon] team has enabled us to bring more value and better security products and services to our customers,” said Ring founder Jamie Siminoff, who now works for Amazon, in an emailed statement.

In 2016, a group of investors led by the Alexa Fund bought a stake in Nucleus, a small company that made a home-video communication device that integrated with the Alexa voice assistant.

Nucleus’s founders and the venture-capital funds investing alongside the Alexa Fund had reservations about collaborating with an Amazon-backed firm, according to some of the co-investors.

“Our biggest concern at the time that we invested was that Amazon could come up with a competing product,” one of the investors said. Representatives from the Alexa Fund told co-investors there is a firewall between the Alexa Fund and Amazon itself, the investor said.

Some investors and people involved with the deal said Amazon assured them and Nucleus’s leadership it wasn’t working on a competing product.

After striking the deal, the Alexa Fund got access to Nucleus’s financials, strategic plans and other proprietary information, these people said. Eight months later, Amazon announced its Echo Show device, an Alexa-enabled video-chat device that did many of the same things as Nucleus’s product.

Nucleus’s founders and other investors were furious. One of the founders held a conference call with some investors to seek advice. He said there was no way his small company could compete against Amazon in the consumer space, according to people on the phone call, and began brainstorming ways to pivot his company’s product.

An Amazon spokeswoman said that the Alexa Fund told Nucleus about its plans for an Echo with a screen before taking a stake in the company. Several people on the Nucleus side of the deal disputed that.

Before Amazon introduced its product, the Nucleus device was sold at major retailers such as Home Depot, Lowe’s and Best Buy. Once the Echo began selling, those sales declined sharply and retailers stopped placing orders, said two people involved in the deal.

Nucleus threatened to sue Amazon, which settled with Nucleus for $5 million without admitting wrongdoing, according to people familiar with the settlement. Both sides agreed not to discuss the matter.

Nucleus reoriented its product to the health-care market, where it has struggled to gain traction, some of those people said.

In 2010, Amazon invested in daily-deals website LivingSocial, gaining a 30% stake and representation on the startup’s board. Former LivingSocial executives said Amazon began requesting data. “They asked for our customer list, merchant list, sales data. They had a competitive product and they demanded all of this,” said one former executive. LivingSocial declined to hand over the data, this person said.

LivingSocial executives began hearing from clients that Amazon was contacting them directly and offering them better terms, some former executives said. Amazon also began hiring away LivingSocial employees. Groupon Inc. bought LivingSocial, including Amazon’s stake, in 2016.

“We may have been naive in believing they weren’t competitive with us, and we ran into conflicts over employees, merchants, customer lists and vendors,” said John Bax, LivingSocial’s chief financial officer until 2014.

Vocalife LLC, a Texas-based sound-technology firm, has sued Amazon, alleging it improperly used proprietary technology. Amazon had contacted the inventor of Vocalife’s speech-detection technology in 2011 after he had received an award at the Consumer Electronics Show, said Alfred Fabricant, a lawyer representing Vocalife.

The inventor thought the visit could be a prelude to some kind of licensing deal or buyout offer, according to Mr. Fabricant. He demonstrated a microphone array, for which he had filed for two patents, and sent over documentation related to its invention and engineering, Mr. Fabricant said. Shortly after the meeting, Amazon’s executives didn’t respond to several emails from the inventor, Mr. Fabricant said.

Vocalife contends that Amazon used the technology in its Echo device, infringing on its patents.

“They find technology they think is extremely valuable and seduce people to engage with them, and then cut off all communication after initial sessions with an inventor or company,” Mr. Fabricant said. “Years later, lo and behold, the technology is in an Amazon device.”

Amazon has disputed Vocalife’s claims in responses to the court, an Amazon spokesman said. The case is slated for trial in September.

Leor Grebler created a voice-activated device called Ubi that had much of the functionality of an Amazon Echo, and he got it on the market well before the Echo was introduced. In late 2012, he said, he began meeting with Amazon about his technology. He said he thought Amazon would want to acquire Ubi or license the technology.

Both parties signed nondisclosure agreements meant to prevent them from improperly using information gleaned in the discussions. They held five discussions bound by the agreement, Mr. Grebler said.

In early 2013, a team of Amazon executives, including two involved in developing the Echo speaker, flew to Toronto for a demonstration of the technology, Mr. Grebler said. Before the meeting, Amazon called and said that it would be terminating its nondisclosure agreement, which Mr. Grebler said he interpreted as a step that could lead Amazon to buy Ubi.

During the demonstration, the Ubi device told the participants the weather in the area after receiving voice-activated instructions, it checked flight statuses and sent emails, said Mr. Grebler. He asked the Ubi to turn the lights on and off.

Mr. Grebler said he provided Amazon with lots of proprietary information during the meetings. “They saw all the things we wanted to do with the device [like] music and shopping. It was almost a road map for the product,” he said.

After that final meeting, Amazon began engaging less with Mr. Grebler, he said. On Nov. 6, 2014, he received an email from his brother with the subject line “Uh Oh.” It contained a link to an article about Amazon’s planned Echo device.

An Amazon spokesman said that work on its Echo device had been under way for some time by 2012, when it began meeting with Mr. Grebler, and that it told him it was working on a competing product.

Mr. Grebler said he met with a law firm to consider his legal options, but decided he didn’t have the funding to sue Amazon. The Echo launched on June 23, 2015.

In the six months that followed, Mr. Grebler said, “We ended up burning through our cash and ended up having to downsize most of the company. We moved out of our offices.” Six months after the Echo started selling, Ubi discontinued its product and tried to pivot to becoming a voice-enabled services provider.

Matthew Hammersley, the co-founder of a voice-driven storytelling app company called Novel Effect Inc., said he accepted an investment from the Alexa Fund in 2017 despite hearing about Nucleus’s experience with the Alexa Fund.

As part of Alexa’s incubator program for early-stage startups, he had meetings with a half-dozen Amazon executives, including top Alexa executives, he said. In the end, Mr. Hammersley, a former patent lawyer, decided not to let his app operate on Alexa devices.

“We could never work out a deal because Alexa can’t do what our voice technology does, and our options were either we teach them how to do this and you use our software, or you license this from us,” said Mr. Hammersley, who said Amazon asked to be shown how the technology works. “We couldn’t come to an agreement there, because obviously I’m not going to teach them how to do it.”

An Amazon spokesman said that Alexa Fund has a strong relationship with Novel Effect.

Vivint Smart Home Inc., a maker of doorbell cameras, garage-door openers and other connected-home devices, was one of the first smart-home companies to integrate with Amazon’s Echo devices. In 2017, Amazon was launching an update to its Echo speakers.

It told Vivint that it would only allow the company to remain on the Echo if Vivint agreed to give it not only the data from its Vivint function on Echo, but from every Vivint device in those customers’ homes at all times, according to people familiar with the matter and emails reviewed by the Journal.

Vivint customers typically have about 15 of the company’s devices in their homes, and the company has more than 1.5 billion pieces of data coming in daily from customers the company monitors for home-security issues. The company declined to hand over the data. Even so, Vivint remained integrated with the Echo devices.

A Vivint spokeswoman confirmed that Amazon asked for all such device data. An Amazon spokesman said the company didn’t request information on devices not connected to Alexa.

Updated: 9-19-2020

Six Charged With Bribing Amazon Employees To Boost Third-Party Sellers

Defendants were part of groups that acted as consultants to vendors on Amazon’s marketplace, according to the indictment.

A federal grand jury in Washington state has indicted six people on charges of bribing Amazon.com Inc. AMZN -1.79% employees to gain advantages for third-party sellers on the e-retailer’s online storefront, where its business practices have drawn increased regulatory scrutiny.

Since at least 2017, the defendants were part of groups that acted as consultants to vendors on Amazon’s marketplace, the U.S. attorney’s office for the Western District of Washington alleged. In that role, the defendants paid more than $100,000 in bribes to Amazon employees to give some third-party sellers a leg up over competitors, according to the charges.

The indictment gives a window into some of the behind-the-scenes tactics that have been used to manipulate Amazon’s marketplace for third-party sellers and undermine trust in the accuracy and quality of its listings.

Amazon has struggled to contain the sale of faulty products on its site, including listings for thousands of products that had been deemed unsafe by federal agencies, The Wall Street Journal reported last year.

The six people charged—including two former Amazon workers—allegedly bribed Amazon employees to reinstate sales of products that were deemed substandard or dangerous, such as suspect dietary supplements and inflammable household electronics.

The alleged conspirators also worked to attack clients’ competitors by using inside access to suspend accounts and share proprietary details about Amazon’s algorithms for listings, the U.S. attorney’s office said.

The conspiracy allegedly unfolded as the group used insider information to contact and recruit Amazon employees and contractors who would take bribes in exchange for manipulating accounts on Amazon Marketplace, according to the U.S. attorney’s office.

In exchange for bribes, Amazon insiders provided the group access to proprietary Amazon data, which they used to the advantage of their third-party seller clients. In some cases, the defendants gained credentialed access to the company’s systems even though they didn’t work for Amazon, prosecutors said.

Amazon said in a statement that the company supported the investigation and had worked with the federal agencies involved in the criminal probe.

“Bad actors like those in this case detract from the flourishing community of honest entrepreneurs that make up the vast majority of our sellers,” the company said.

Two defendants, Joseph Nilsen and Kristen Leccese of New York City, provided consulting services for third-party sellers through a company called Digital Checkmate Inc., according to the U.S. attorney’s office. Another New York City man, Ephraim Rosenberg, led a similar operation called Amazon Sellers Group TG. A fourth defendant, Hadis Nuhanovic of Acworth, Ga., also provided fee-based consulting for third-party sellers in addition to running his own third-party seller accounts.

The other two people charged in the scheme, Rohit Kadimisetty and Nishad Kunju, are former Amazon employees, both of whom worked for the company in Hyderabad, India. Later, the two men became consultants to third-party sellers. Mr. Kadimisetty now lives in Northridge, Calif., according to the U.S. attorney’s office.

Including Mr. Kunju, at least 10 Amazon employees and contractors accepted bribes in the scheme that had been under way since at least 2017, the charges allege. An Amazon spokesman declined to offer details about other Amazon employees who may have been involved in the alleged bribery.

Amazon has previously drawn attention for its practices around third-party sellers who use the company’s website to sell products. The Wall Street Journal reported in April that the company was using data on third-party sales to launch its own competing products. The revelations sparked a congressional investigation that contributed to rising federal scrutiny of tech giants this year.

Attempts to contact the defendants directly were unsuccessful.

“We are in the midst of reviewing the indictment,” Sara Shulevitz and Mindy Meyer, lawyers who are representing Mr. Nilsen, said in a statement. They added that they will comment further after fully reviewing the charges.

“We don’t believe that the allegations…are fair or accurate,” said Jess Johnson, a lawyer representing Mr. Nuhanovic.

“We are studying the indictment and will vigorously respond to these charges in court,” Peter Offenbecher, a lawyer for Mr. Rosenberg, said in an emailed statement.

The wire-fraud and wire-fraud-conspiracy charges against the group can bring up to 20 years in prison plus fines, the U.S. attorney’s office said. Another charge, conspiracy to use a communication facility in furtherance of commercial bribery, is punishable by up to five years in prison plus fines.

The defendants are scheduled to appear in U.S. District Court in Seattle on Oct. 15.

Updated: 9-23-2020

Amazon Restricts How Rival Device Makers Buy Ads On Its Site

Some makers of smart speakers, video doorbells and other hardware hit roadblocks buying key ads in search results; gadgets made by e-commerce giant get edge.

Amazon.com Inc. is limiting the ability of some competitors to promote their rival smart speakers, video doorbells and other devices on its dominant e-commerce platform, according to Amazon employees and executives at rival companies and advertising firms.

The strategy gives an edge to Amazon’s own devices, which the company regards as central to building consumer loyalty. It puts at a disadvantage an array of gadget makers such as Arlo Technologies Inc. that rely on Amazon’s site for a significant share of their sales.

The e-commerce giant routinely lets companies buy ads that appear inside search results, including searches for competing products. Indeed, search advertising is a lucrative part of the company’s business. But Amazon won’t let some of its own large competitors buy sponsored-product ads tied to searches for Amazon’s own devices, such as Fire TV, Echo Show and Ring Doorbell, according to some Amazon employees and others familiar with the policy.

Roku Inc., which makes devices that stream content to TVs, can’t even buy such Amazon ads tied to its own products, some of these people said. In some cases, Amazon has barred competitors from selling certain devices on its site entirely.

The policies show the conflicts between Amazon’s large e-commerce platform for sellers and its role as a product manufacturer in its own right. While traditional retailers buy inventory from manufacturers and resell it to consumers, limiting the number of vendors they can work with, Amazon’s platform has more than a million businesses and entrepreneurs selling directly to Amazon’s shoppers.

Amazon accounts for 38% of online shopping in the U.S. and roughly half of all online shopping searches in the U.S. start on Amazon.com.

Amazon’s digital-advertising business, moreover, ranks behind only that of Google and Facebook Inc. That first page of search results can make or break a seller, with the majority of Amazon shoppers buying from the company’s first page of search results.

In response to a request for comment, Amazon didn’t directly address the question of whether or not it hobbles rivals’ marketing. Instead, it said that it is common practice among retailers to choose which products they promote on their websites.

“News Flash: retailers promote their own products and often don’t sell products of competitors,” said Amazon spokesman Drew Herdener in a written statement. “ Walmart refuses to sell [Amazon brands] Kindle, Fire TV, and Echo. Shocker. In the Journal’s next story they will uncover gambling in Las Vegas.”

But the restrictions Amazon has put in place mean that products sold directly by Roku often don’t appear atop search results for Roku’s own products. In tests conducted by The Wall Street Journal in August, searches for Roku products frequently displayed sponsored product advertisements for Roku competitors, and Rokus offered by resellers. Many of the searches displayed Amazon’s Fire TV product atop the results, with a banner saying “Featured from our brands.”

Amazon already is facing scrutiny over its treatment of competing sellers on its site. In July, CEO Jeff Bezos testified to Congress about Amazon’s business practices and the tactics of its private-label brands. The Federal Trade Commission, Justice Department, European Union and Canadian regulators are also looking into Amazon’s business practices.

In April, the Journal reported that Amazon’s private-label employees used data from its third-party merchants to create competing Amazon-branded products.

Amazon has had success in recent years selling its own hardware, including Kindle e-readers, Echo smart speakers and Fire TV streaming devices. Amazon employees involved in advertising decisions said the policies for dealing with competing device makers are a deliberate part of Amazon’s strategy for promoting its own products.

Like many platforms, Amazon allows bidders to buy advertising to try to ensure their products appear at the top of search results. This includes purchasing the right to appear in search results for the products of rivals, a standard industry practice. When a company purchases such ads on Amazon, the products appear in the search results and are labeled as “Sponsored.”

In the case of competing device makers, Amazon’s devices team flagged some of the biggest to its advertising team to restrict them from buying ads tied to keywords for Amazon-branded products, according to the employees involved in advertising decisions. Amazon’s largest rivals in certain categories, which it calls “Tier 1 Competitors,” are unable to buy Amazon-specific keywords, those people said, while lesser competitors are allowed to buy the keywords.

When the devices team launches a new product, part of its strategy for bringing it to market is to determine which keywords to suppress in advertising, the people said. Employees are told to mark any discussion of this practice internally at Amazon with “privileged and confidential” in the subject line of emails so that regulators cannot access them, the people said.

An Amazon spokesman said that employees are instructed to mark emails as privileged only when seeking legal counsel.

Documents released after July’s congressional hearing indicate that Amazon told Apple Inc. that it gives its own devices favorable treatment. The documents said Amazon’s own products have “competing ads removed from search,” product detail pages and checkout pages. As part of negotiations with Apple, Amazon offered it “content, search and navigation equivalent to what Amazon has for its own products,” the documents said.

An Amazon spokesman said that for some keywords related to Amazon devices, Amazon may offer more limited ad inventory.

Roku, based in San Jose, Calif., is the biggest maker of streaming-media players in the U.S., according to research firm Strategy Analytics. As a device maker and a platform for streaming content, it competes directly with Amazon’s Fire TV devices. Amazon is the second-largest streaming-device maker with its line of Fire TV products.

Roku has been blocked from buying sponsored product advertisements on Amazon for years, although resellers of Roku products are able to buy Roku keywords for such ads, according to people familiar with the matter and documents reviewed by the Journal.

In Journal searches conducted in August for “Roku Ultra,” a streaming box with headphones the company was then selling for $89.88, the top result was a sponsored ad from TiVo, a rival streaming-device maker.

Two other sponsored results followed. One listing was from a seller called “AMAZING WAREHOUSE DEAL” that was selling the Ultra for $119.99. The other, from seller iPuzzle Online, bundled the Ultra with a 6-foot HDMI cable for $165.

To purchase a Roku Ultra from Roku, a buyer would have had to scroll down to the fourth result, where it sold for $89.88, according to the Journal review.

In another search by the Journal on Amazon for “Roku Streaming Stick,” Amazon featured its Fire TV products four times under “Featured from our brands” on the first page of search results, which generally show about 20 to 25 results. The Fire TV products showed up twice more on the first page of results.

By comparison, a search for “Fire TV” at around the same time showed an Amazon “Fire TV” banner across the site’s search results, with the Amazon logo followed by three Amazon products sold by Amazon. There were no sponsored results in that search, the analysis showed.

Amazon limits competitors’ advertisements by using up to five of the 12 spaces typically sold as advertisements to highlight its own offerings, according to a Journal analysis of search results. For six days, the Journal downloaded search results for 67 keywords describing Amazon products and those by competing brands including Google, Roku and Arlo.

Netgear Inc., based in San Jose, is able to buy the keywords of rival makers of Wi-Fi routers on Amazon. For the past year and a half, the company hasn’t been able to buy search ads keyed to “eero,” Amazon’s own brand of router, that appear on the first page of results, according to people familiar with the matter. Amazon bought eero in early 2019.

Facebook hadn’t been able to buy sponsored ads using Amazon Echo-related keywords for some time, according to a person familiar with the matter. The social-media company makes a device called Facebook Portal that competes directly with Amazon’s Echo Show device. Facebook has been able to buy keywords for other competitors, the person said.

Amazon started its advertising unit in 2012, allowing sellers on its site to bid on keywords used in search queries. With more than a million sellers competing on Amazon, many selling similar or identical items, its sponsored-product advertisements business became an important way for sellers to ensure that their items got to the top of the first page of search results.

Last year, the Amazon unit that includes its advertising business brought in $14.1 billion in revenue. Amazon will capture 17.1% of the $54.37 billion U.S. search-ad market, research firm eMarketer estimated in June 2020.

According to Amazon’s advertising website, any seller is eligible to buy keywords for its sponsored-search advertisements.

Some types of products are prohibited from being advertised in sponsored products, its website says. Amazon’s own products aren’t on the list of keywords or categories restricted for sponsored-product advertisements.

An Amazon spokesman said advertisers can bid on or buy Amazon keywords.

Amazon blocked Google from selling its Chromecast streaming devices, which compete with Fire TV, for more than a year, the people said. Google said in December 2017 that it was pulling its YouTube online-video service from some Amazon devices in retaliation for Amazon refusing to sell many Google products. In 2019, Google reversed course.

Amazon’s device business has been a priority for Mr. Bezos. “When somebody buys an Amazon device, they become a better Amazon customer,” said Dave Limp , head of the company’s devices business, in an interview last year. Amazon can build services attached to those devices, he explained, enabling it to sell the gadgets at a low price. “We don’t have to make money when we sell you the device,” he said.

Amazon’s acquisition of Ring shows how its ownership can change a device-maker’s fortunes on its site.

Before that deal, Arlo Technologies, which makes smart security products and doorbells, was the market leader for smart security devices. Emails in 2017 between Amazon’s management team discussing a potential acquisition of Ring referenced Arlo’s top position at the time. Ring held the second sales position, followed by Google Nest and startup Blink, according to the emails, which were disclosed as part of a congressional hearing.

“To be clear, my view here is that we’re buying market position—not technology,” Mr. Bezos wrote that Dec. 15. “And that market position and momentum is very valuable.” Amazon bought smart camera and doorbell startup Blink in late 2017 and purchased Ring a few months later in early 2018.

Since then, Arlo has been unable to buy keywords on Amazon’s sponsored product advertisements for Ring products, said people familiar with the matter. Amazon’s Ring devices, though, have appeared at the top of the search results for “Arlo,” in banner placements touting “Featured from our brands” showing a suite of Ring Doorbell devices.

Arlo’s team raised this issue with Amazon’s advertising team, the people said. Arlo was concerned that it could buy keywords for competitors like Eufy and Wyze, but not for Amazon’s own brands such as Ring and Blink, the people said. The advertising team apologized to Arlo executives, and said that there was nothing they could do about the issue, the people said.

Updated: 11-1-2020

After Going All-In on Amazon, a Merchant Says He Lost Everything

Barak Govani says he was kicked off the site after being falsely accused of selling fakes. Accounts like his prompted a House panel to accuse Amazon of mistreating its merchants.

Barak Govani made a big bet on Amazon.com Inc. earlier this year that he now regrets. He shuttered his New York Speed clothing store on Los Angeles’s storied Melrose Avenue, packed up $1.5 million in inventory and shipped it to Amazon warehouses around the country, putting his fate in the hands of a company that has routinely presented itself to the world as a friend of small business.

Today, the 41-year-old retail veteran is broke and couch surfs between his mother’s home and his sister’s place. Govani hopes to start anew by getting Amazon to pay him for inventory the company destroyed after suggesting his products could be fake—an accusation Govani strenuously denies. His lawyer in September sent a demand for $800,000—along with invoices to verify his merchandise came directly from fashion brands—and they’re waiting for Amazon’s response.

“All my life, I’d wake up at 5:30 a.m. and work 40, 50, 60 hours each week,” Govani said. “That inventory was everything I had. Amazon ruined my life, and I did nothing wrong.”

Amazon has become the world’s largest e-commerce company in large part thanks to the millions of third-party merchants who have chosen to set up shop on its sprawling marketplace. Small- and medium-size businesses are responsible for more than half of the goods the company sells to customers around the world—moving 3.4 billion products alone in the year ending May 31. The average small business has annual sales of $160,000 on Amazon, up about 60% from the previous year.

In blogs and press releases, Amazon highlights the success of these merchants as a win-win—for them and itself. Lost in the public-relations glare are merchants like Govani.

Stories like his have swirled for years in online merchant forums and conferences. Amazon can suspend sellers at any time for any reason, cutting off their livelihoods and freezing their money for weeks or months. The merchants must navigate a largely automated, guilty-until-proven-innocent process where Amazon serves as judge and jury.

Their emails and calls can go unanswered, or Amazon’s replies are incomprehensible, making sellers suspect they’re at the mercy of algorithms with little human oversight.

Recourse is limited because when merchants set up shop on Amazon, they waive their right to a day in court by agreeing to binding arbitration to resolve any disputes. Amazon doesn’t negotiate terms with merchants. The boiler plate agreement is take-it-or-leave-it, a telling reminder of who has the upper hand in the relationship.

How Amazon treats third-party sellers is at the heart of a recent House Judiciary Committee report concluding that big technology companies often abuse their power over smaller partners. The committee’s recommendations include providing adequate recourse to sellers and eliminating forced arbitration clauses from contracts that deprives them from filing a lawsuit.

“Because of the severe financial repercussions associated with suspension or delisting, many Amazon third-party sellers live in fear of the company,” the report states. “This is because Amazon’s internal dispute resolution system is characterized by uncertainty, unresponsiveness and opaque decision-making processes.”

In an emailed statement, an Amazon spokeswoman said the company works hard to ensure products sold on its site are authentic and provides a fair dispute resolution process.

‘Inauthentic’ Products

Govani has been selling clothes for more than 20 years, mostly brands like Hugo Boss, Calvin Klein and Lucky. About a decade ago, he began supplementing his store sales by putting merchandise on web marketplaces including Amazon and EBay Inc. Amazon emerged as the most effective partner, accounting for more than 90% of his online sales.

Initially, Govani stored, packed and shipped all the orders himself, paying the company a commission on each sale. Amazon representatives suggested he try Fulfillment by Amazon, a service that handles that for additional fees. Govani decided to send all of his inventory to Amazon, becoming one of 450,000 businesses to try the service in the year ending May 31.

Govani’s problems began soon afterward. In April, Amazon emailed him to say his account was being reviewed based on four customer complaints over “inauthentic” products.

“In order to ensure that customers can shop with confidence on Amazon, we take ‘inauthentic’ complaints seriously,” the message said. “The sale of counterfeit products on Amazon is strictly prohibited.”

One complainant from San Rafael, California, was unhappy with the fit of a $125 Lucky Moto jacket and said she was “wondering if this was a fake.” Govani refunded her money and explained that jackets made with different materials fit differently.

Another shopper was upset that his Calvin Klein underpants arrived in a damaged carton. “Box is pretty much broken, the item is a knock off,” the shopper said in a product review. It’s not clear why Amazon characterized the other two complaints—about apparel wrapped in tissue paper and shipped in envelopes—as “inauthentic.”

Govani appealed the suspension and submitted invoices from the brands to Amazon. His invoices were more than a year old because that’s when he had purchased the inventory, but Amazon wanted invoices from the previous 365 days. Govani was notified that his inventory would be destroyed if he didn’t reclaim it by mid-July. Merchants must pay Amazon additional fees for inventory removal.

Hoping to have his account reinstated and continue selling on the site, Govani put off the decision. He was equal parts encouraged and confused by subsequent messages from Amazon saying his inventory was scheduled to be destroyed later in July and then in early August then in late August. He received a total of 11 emails from Amazon each giving him different dates at which time his inventory would be destroyed if he hadn’t removed it.

He sought clarity from Amazon about the conflicting dates. When he tried to submit an inventory removal order through Amazon’s web portal, it wouldn’t let him.

The spokeswoman said Amazon repeatedly asked Govani to provide evidence that the products sold were authentic but that the invoices he sent were either illegible or didn’t match the records of the brand owners.

“After being unable to resolve the matter following several appeals as part of our dispute resolution process, we informed this seller six separate times that they needed to remove their inventory from our store by specific dates or it would be destroyed,” she said. “The seller failed to request to remove their inventory by the dates provided.”

Emailing Bezos

At the end of July, Govani sent a panicked email to Chief Executive Officer Jeff Bezos—the world’s wealthiest man—with the subject line: “URGENT: Invalid Disposal of $1.5 Million Worth of Inventory.” He exchanged emails with an Amazon representative named “Brigitte M.,” who promised to investigate.

“I haven’t been able to sleep for months now and I still do not know what Amazon is going to do that will determine my future,” Govani said in a final plea to Brigitte M. on July 31. “Amazon is in possession of my entire life’s hard work, closing my seller account with no valid reason that I understand and disposing of it! All of that without proper communication with me, not responding within a timely manner, responding without answering my questions or addressing the actual issue, being vague.”

Brigitte M. gave her final response on Aug. 3, reiterating that there was nothing else she could do. “I understand that you are disappointed with our previous response and we regret this inconvenience,” she wrote. “I’m sorry for any disappointment caused and appreciate your understanding. We won’t be able to comment further on this matter.”

Amazon has been more aggressive in using algorithms to knock suspected counterfeits off the site, and consultants say Govani’s experience is common. Chris McCabe, a former Amazonian who now helps merchants navigate the appeal process, says suspensions based on complaints about inauthentic products are rising and often lodged by rival merchants looking to sabotage a competitor.

“Numerous sellers find themselves appealing this endlessly only to hear that their invoices aren’t acceptable or their suppliers aren’t verifiable, but without any indication as to why,” said McCabe, who testified before the House panel. “Or they receive no reply.”

If Amazon declines to reimburse Govani for his inventory, his next step is binding arbitration, which the House panel said gives Amazon the upper hand in disputes. From 2014 to 2019, only 163 Amazon merchants initiated arbitration proceedings against the company because “sellers are generally aware that the process is unfair and unlikely to result in a meaningful remedy,” the report states.

“Arbitration functions as a way for Amazon to keep disputes within its control, with the scales tipped heavily in its favor,” the report’s authors wrote. “As such, Amazon can withhold payments from sellers, suspend their accounts without cause, and engage in other abusive behavior without facing any legal consequences for its actions.”

Govani’s attorney Mario Simonyan, who has represented other Amazon sellers in similar disputes, suspects the company will make a low-ball offer, forcing Govani to decide if he wants to pay for arbitration, which can cost tens of thousands of dollars.

Govani said he is eager to start a new business in an entirely new field—possibly construction—even though he spent his career in retail.

“I don’t want to go back to online retail even though it’s the only thing I’m good at,” Govani said. “I’m so scared to sell on Amazon. This has been traumatizing.”

Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,Amazon Tests Pop-Up Feature,

Related Articles:

Amazon Is Contributing To Global Pollution!!! Sign Our Petition To End This Now!!

Why Does Amazon Want To Hire Blockchain Experts For Its Ads Division?

Amazon Wants To Build A Blockchain For Ads, New Job Listing Shows (#GotBitcoin?)

Supermarkets Try Swapping Cashiers For Cameras Like Amazon (#GotBitcoin?)

Amazon-Owned Twitch Quietly Brings Back Bitcoin Payments (#GotBitcoin?)

You Can Now Shop With Bitcoin on Amazon Using Lightning (#GotBitcoin?)

Why Amazon Needs Others To Keep Selling (#GotBitcoin?)

‘They Own the System’: Amazon Rewrites Book Industry By Marching Into Publishing (#GotBitcoin?)

Is It Really Five Stars? How To Spot Fake Amazon Reviews (#GotBitcoin?)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.