Germ-Killing Brands Now Want To Sell You Germs (#GotBitcoin)

The world’s best-known antibacterial labels are pouring millions into probacterial health and beauty startups. Germ-Killing Brands Now Want To Sell You Germs (#GotBitcoin)

It was a snowy week in February 2009 when David Whitlock packed up his three-bedroom apartment near Cambridge, Mass., and moved into his van.

Then 54 years old, the inventor had spent all his money, almost half a million dollars, on worldwide patent filings for a newfound obsession: a type of bacteria, culled from soil samples, that he theorized would improve skin disorders, hypertension, and other health problems.

“It was the most important thing I could work on,” Whitlock says. “But I knew I needed patents, otherwise I wouldn’t be able to get anyone interested.”

To make his white Dodge Grand Caravan habitable, Whitlock sawed down his queen-size bed frame and squeezed it in. He donated or abandoned most of his furniture, storing his lab equipment in a barn owned by his business partner, Walter “Hilly” Thompson.

Then Whitlock drove to his former employer, cement company Titan America LLC, where he still had an office and did some consulting.

Without asking permission, he pulled into the parking lot and made it home for the next four and a half years. “I found that if I stayed fully dressed and got inside two sleeping bags, I could tolerate it,” he says of the coldest winter nights.

Every so often, he would coat himself in a concoction made with his homegrown bacteria, a ritual he’d begun years earlier in the belief it would improve his overall health and all but eliminate the need to bathe or use soap.

Then he’d spend the day in his office, tirelessly researching microbes. “A lot of people gave me shit for living in my car,” Whitlock says. “But it was like nothing, trivial.”

His real problem was finding investors, a challenge exacerbated by his autism spectrum disorder. To get his message out, he relied mainly on Thompson. Most everyone dismissed the duo’s idea as nuts.

Today things look very different. Whitlock lives in an apartment, and his startup, AOBiome Therapeutics Inc., has raised almost $100 million.

The company is seeking to become the first to get Food and Drug Administration approval for pharmaceutical-grade topical live bacteria, with six clinical trials under way to treat acne, eczema, rosacea, hay fever, hypertension, and migraines.

AOBiome’s cosmetics branch, Mother Dirt, already counts tens of thousands of customers for its products, including the spray Whitlock developed from his bacterial elixir; they’re sold online, at natural beauty and food retailers, at Whole Foods Market stores in the U.K., and, starting in June, in the U.S. Several of Whitlock’s early investors are so enthusiastic about AOBiome that they’ve adopted his hygiene habits.

“I haven’t used soap or shampoo or antiperspirant or deodorant or toothpaste or mouthwash in five or six years,” says entrepreneur and venture capitalist Lenny Barshack.

The company’s message fits well with a growing body of research into the human microbiome showing that some bacteria are not only good but also vital. Microbial imbalances play a role in many conditions, including allergies, autism, cancer, depression, irritable bowel syndrome, and obesity.

Also, probiotics and prebiotics—which refer, respectively, to beneficial live microbes and the ingredients that promote their growth—are a new frontier in health and beauty.

From 2015 to 2016, equity funding for companies invested in the so-called microbiome jumped from $173 million to $728 million, according to CB Insights, a company that tracks the tech market. Last year the figure rose to $939 million. The global market for probiotic supplements reached $5 billion in 2017, according to the International Probiotics Association, making it the fastest-growing supplement category in the world.

Even corporations that built brands dedicated to killing bacteria are investing in microbiome research and startups, sometimes on the sly.

In 2016 the Clorox Co., maker of microbe-annihilating Clorox Bleach, acquired Renew Life Formulas Inc., which sells prebiotic and probiotic supplements. This January, Unilever Ventures Ltd., the conglomerate’s investment arm, took a minority stake in Gallinée, a tiny London-based startup whose slogan is “Happy skin needs happy bacteria.”

The German chemicals giant BASF is 3D-printing artificial skin and embedding it with bacteria to develop treatments for aging, pigment disorders, and pollution exposure. And last October, AOBiome licensed Whitlock’s bacteria spray to MBX LLC, which trademark and company documents reveal to be a shell company owned by S.C. Johnson & Son Inc., maker of Windex, Drano, and Raid.

The term “microbiome” is widely traced to a 2001 Scientist magazine article that deployed it “to signify the ecological community of commensal, symbiotic, and pathogenic microorganisms that literally share our body space.” That group includes fungi, viruses, and bacteria, some of which help produce vitamins, hormones, and other chemicals vital to our immune system, metabolism, mood, and much more. In the typical person, these microorganisms account for about 2 pounds and roughly as many cells as the ones containing human DNA.

In recent decades our microbiomes have been altered by poor dietary habits; overuse of disinfectants, antibiotics, and other germ fighters; dwindling contact with vital environmental microbes, including those carried by wildlife and livestock; and the rise in cesarean section births, which don’t immerse babies in the valuable bacteria found in the birth canal. According to one 2015 study, Americans’ microbiomes are about half as diverse as those of the Yanomami, an isolated Amazonian tribe.

A series of studies begun in 1998 examined the relationship between bacteria and disease incidence in the Finnish-Russian border region of Karelia, where people share similar genetics. On the richer, cleaner Finnish side, people were as many as 13 times likelier to suffer from inflammatory disorders as on the Russian side, where the majority live in rural homes, keep animals, and tend their own gardens.

A comparable American study, published in 2016, examined the genetically similar Hutterites of South Dakota and Amish of Indiana. The Hutterites, who use pesticides and industrial farming techniques, had higher asthma incidence, 23 percent, than almost any other U.S. group. Among the Amish, who farm without chemicals and rely on manpower and horses, the condition is quite rare. To see whether each community’s respective bacterial populations were affecting people’s health, researchers collected dust samples from Hutterite and Amish bedrooms, mixed them with egg proteins, then gave them to mice with an egg-protein allergy.

The mice exposed to Hutterite dust developed extreme asthmatic symptoms, whereas those exposed to Amish dust exhibited almost no allergic response.

These and many more studies have some scientists fearing that people, especially in the West, are cleaning themselves sick. The trick for companies hoping to cash in on the countervailing trend will be to figure out which microbes help restore human health. It won’t be easy.

“Most of the species in our body don’t have names. They’ve not been cultured,” says Robert Dunn, a professor of applied ecology at North Carolina State University, whose most recent book, Never Home Alone, details the relationship between nature and health. “Nobody has studied them in any real detail.”

“That first winter, I did start to smell,” Whitlock recalls. Instead of giving up, he doubled down

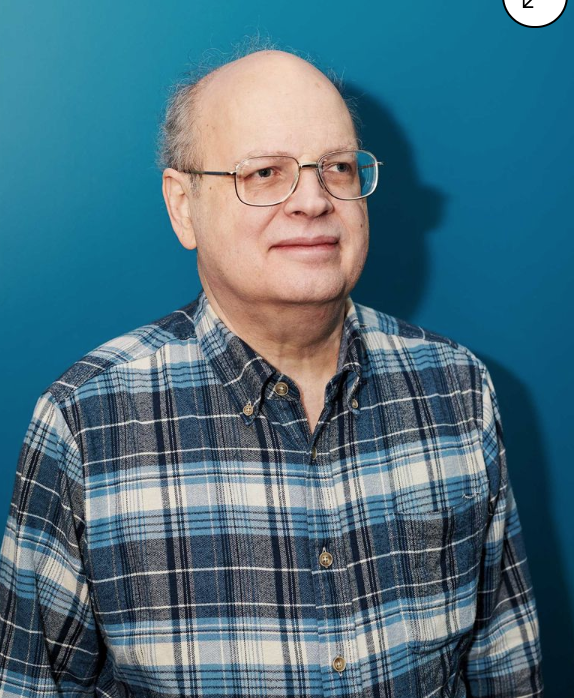

Whitlock’s passion for microbes began around 2000. “No one was talking about this stuff back then,” he says, sitting in a conference room at AOBiome’s headquarters in Cambridge. At 64, he’s bald on top, with wispy gray hair around his ears. His daily uniform consists of large wire-rimmed glasses, well-worn jeans, hiking boots, and a flannel shirt. For the record, he has no discernible odor.

His autism is pronounced enough that he didn’t notice when all his colleagues dressed like him on his birthday in 2015. Nor did he recognize me the third time we met for an interview. But in conversation he’s open and funny about his passions and quirks. Among the latter is his habit of drinking multiple cups of black coffee a day from a sludge-coated mug advertising the antidepressant Zoloft, which he’s been taking for decades. “I haven’t washed it in probably 20 years,” he says. In an effort to improve his longevity, Whitlock eats only one meal a day: typically a breakfast pile of oats, dried blueberries and raisins, prunes, mushrooms, and a half-pound of shredded mozzarella.

For an entire year, he tells me, he also ate hard-boiled eggs with the shells still on. “That wasn’t an experiment. I just thought it was a good idea—and it wasn’t,” he says, shaking his head. “Shells have sharp edges.”

Whitlock holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees in chemical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Before starting AOBiome, he invented a more environmentally friendly cement production process and, together with Thompson, co-founded Separation Technologies Inc., which Titan America bought in 2002. He didn’t begin thinking in earnest about biology until a fateful date with a bubbly fifth grade teacher.

Why, she asked him, did her horse roll in the dirt, even in the cool springtime months before biting insects had hatched? “I was her Mr. Scientist friend, and I tried to find an answer,” Whitlock says. The romance didn’t flourish, but his curiosity did; he read hundreds of scientific papers and grew fascinated by a type of bacteria, found in soil and other natural environments, that derives energy from ammonia rather than organic matter.

That gave him an idea: What if these ammonia-oxidizing bacteria, or AOB, transformed sweat into something beneficial? Further study proved his hunch correct. AOB, it turns out, convert ammonia into nitrite, a molecule with anti-infective properties, and nitric oxide, which Science magazine declared “molecule of the year” in 1992.

“It helps maintain blood pressure by dilating blood vessels, helps kill foreign invaders in the immune response, is a major biochemical mediator of penile erections, and is probably a major biochemical component of long-term memory,” the magazine’s editor wrote. In 1998 three Americans won the Nobel Prize in medicine for discovering that nitric oxide transmits chemical signals important to a wide range of health-related functions.

Hooked, Whitlock began collecting soil samples from stables and fields, then analyzing them in a makeshift basement lab. Eventually he extracted an AOB called Nitrosomonas eutropha, which he describes as “relatively athletic.” He coaxed it to multiply in an ammonia solution using a set of tanks and jury-rigged aquarium bubblers. To test its efficacy, he began running experiments on himself. That’s when he stopped showering. “That first winter, I did start to smell,” he recalls.

Instead of giving up, he doubled down: “I had the idea, if I wear a sweater, I will sweat more, release more ammonia to the AOB, and they will make nitrite, and that will suppress the bacteria that are causing the odor.” When that worked, he tried sleeping encased in a giant plastic bag fashioned from a computer-server dust cover, in the hope that minimal airflow would increase nitric-oxide absorption. That investigation ended after Whitlock broke out in a rash. He also gauged his nightly erections with a volume-measuring device called a plethysmograph, on the theory that more nitric oxide would mean increased blood flow. (He says it did.)

All the while, Thompson was raising money to fund additional research and clinical trials. “I was trying to find people who’d listen and not write David off as some kook,” he says. “David is a very gentle, brilliant man who really cares about people and helping the world, and money was not that big a driver for him.” Even though Thompson didn’t fully understand AOB himself, he spent about $600,000 across 12 years to pay Whitlock a minimal monthly stipend and cover patent, equipment, and legal expenses. He was just about to run out of funds when another investor stepped in: Jamie Heywood, co-founder of PatientsLikeMe, an online info-sharing network.

Three years earlier, Whitlock had presented Heywood with a tinfoil-wrapped Poland Spring bottle filled with his microbial elixir. “Here’s my drug,” he said. “Try it.”

Heywood did, and he and his teenage daughter came to swear by it. He recalls thinking he’d be the only one willing to invest with “this crazy guy from MIT who looks like he’s homeless.” But he concluded that the idea was too important to ignore. He also found the underlying science compelling. “It’s a bacterial delivery of a necessary drug,” he says. “You can’t just dump nitric oxide in the system. You have to enhance the body’s ability to operate its own system more effectively.”

Heywood’s group raised an initial round of $1.4 million, recruited a chief executive officer, and retested Whitlock’s science under the banner of AOBiome. “We wanted to see: Is there a bug? What’s its sequence? Can you grow it? Does it do anything? Do any of David’s radical self-experimentation claims hold up?” he says. After the bacteria proved safe, the team began testing on independent human subjects.

One of these early experimenters was the writer Julia Scott, who described her monthlong “No-Soap, No-Shampoo, Bacteria-Rich Hygiene Experiment” in a cover story for the New York Times Magazine. Initially her hair turned dark with grease, and she began to smell. But after the second week, she detected a wonderful change in her skin.

“It actually became softer and smoother, rather than dry and flaky, as though a sauna’s worth of humidity had penetrated my winter-hardened shell,” she wrote. “And my complexion, prone to hormone-related breakouts, was clear. For the first time ever, my pores seemed to shrink.” The article prompted so many inquiries that AOBiome’s web host began bouncing emails, thinking a spam attack was under way.

The team hadn’t intended to introduce a cosmetic brand, but it seized on the opportunity, rebranding its side project Mother Dirt in 2015. The company outsourced the bacteria farming to a bioreactor operator in India, where regulations are less stringent and landlords less squeamish. From there, the AOB were refrigerated and shipped in high concentrations to a monoseptic factory outside Boston for dilution and bottling.

(Full Disclosure:

I was among the early adopters and still occasionally use the spray on my face in humid summer months. At $49 for a 3.4-ounce bottle, it’s a bit pricey, though, and I’ve had mixed results.)

In 2017, Mother Dirt recorded revenue of $2.6 million for its cosmetic spray and a microbiome-neutral cleanser, shampoo, and moisturizer. Some of those sales were to MBX, the shell company registered to S.C. Johnson, under a resale agreement struck that October for every market except China. (The plan is to introduce the cosmetic spray there starting next year.) S.C. Johnson declined to comment on its foray into marketing live bacteria, and AOBiome executives say they’re prohibited from talking about the deal.

In November, beauty experts convened at a stuffy London conference center for the third Skin Microbiome Congress. Many conglomerates were on hand, including BASF, Bayer, Coty, Merck, Nestlé, L’Occitane, L’Oréal, and Unilever, but representatives from startups did most of the talking.

Featured brands included Yun Probiotherapy, a Belgian startup that encapsulates live bacteria and mixes it into creams, and Esse Probiotic Skincare, a company headquartered in South Africa that offers genetic sequencing of the skin microbiome, as well as live-bacteria serums and bacterial spa treatments.

Whitlock wasn’t in attendance—he tends to avoid conferences—but a few kindred spirits were. Esse’s founder, Trevor Steyn, told me he takes the youngest of his seven children outside to eat a weekly spoonful of dirt. “I let them choose where they want to get it from,” he said. “We live in a very rural area outside Durban.”

The picture was very much of a still-gestating industry. “We don’t think it’s mainstream, and we don’t think it’s going to be mainstream next year or the year after that,” Jasmina Aganovic, president of Mother Dirt, told an audience of roughly 200. “All of us are here and dedicated to what we’re doing because we see a long-term vision.”

L’Oréal was among the few big brands to host a talk, demonstrating how harsh cleansers dry out the skin and damage the microbiome, and how some moisturizers begin to revive bacteria populations after a few hours.

(Months after the talk, the French giant announced a partnership with UBiome Inc., a Silicon Valley startup with patented technology for analyzing the human microbiome.) L’Oréal-owned La Roche-Posay also held a talk touting the brand’s thermal spring, which contains diverse bacteria that seem to ameliorate inflammatory skin disorders such as psoriasis; in addition to appearing in cosmetic products, the spring’s waters draw some 8,000 patients each year.

Most of the other large companies just took notes. “The big players come to these conferences and kind of sit on the sidelines,” says Marie Drago, founder of Gallinée, the Unilever-backed happy-bacteria startup. “They have a branding problem to figure out because, for so many years, they’ve been pushing antibacterial products.” “We’ve got far more to lose,” says Geoff Briggs, technology manager for Walgreens Boots Alliance Inc. “If a niche brand is out there and the claims don’t stack up, nobody really cares in the wider world. But if we put something out on a shelf and it doesn’t work, doesn’t support the claims we’re making on it, then it ruins our brand.”

Some companies, including Estée Lauder Inc., have quietly incorporated bacterial ingredients since the 1970s. But “quietly” is the key word, because most consumers still equate microbes with bad skin. Until the science and marketing advance, top companies seem content to invest in smaller brands that can lead the trend while they discreetly pursue their own research. That said, Briggs suggests that all the major personal-care—and even home-care—brands could be at least microbiome-friendly in the next decade.

Getting there could mean eliminating some of the haziness around the category. The FDA still has no precise definition for “probiotic.” And in contrast with the food industry, which defines it as a live microbe with proven health benefits, skin-care brands apply it liberally, to live bacteria, to dead and ruptured bacteria, and more.

Then again, loose definitions haven’t hurt sales of products labeled “natural” or “organic.”

In some respects, the new microbe-oriented brands are trying to restore an earlier, more natural relationship between humans and the environment. And it’s true that people have been exploring microbial beauty and health treatments since before Robert Hooke and Antonie van Leeuwenhoek discovered microorganisms circa 1665.

Cleopatra was said to have bathed in donkey’s milk, which is chock-full of prebiotics. In China, where human stool has been used as medication since at least the fourth century, a 16th century doctor named Li Shizhen penned a recipe for “yellow soup”—a broth made from fresh, dried, fermented, or infant feces—to treat gastrointestinal illnesses.

The potential health benefits of bacteria were expressly recognized as early as 1905, when Elie Metchnikoff, a colleague of Louis Pasteur, hypothesized that Bulgarians’ relative longevity owed not to their yogurt-heavy diet, but more specifically to the lactobacilli used to ferment the yogurt. Soon thereafter, a German doctor, following in the footsteps of the Chinese, created a cure from the excrement of a soldier who’d been the only one in his battalion to evade dysentery during World War I; the doctor’s formulation is still sold as a treatment for digestive problems in Europe, under the Mutaflor label.

It wasn’t until about 15 years ago that scientists developed genetic sequencing tools allowing them to better tally microbial populations and study how their presence or absence affects human health. The advent of improved and cheaper technology has in turn made it possible for a market in microbiome therapeutics to emerge. Tiny for now, the sector could grow to $10 billion by 2024, according to IP Pragmatics Ltd., a London consulting firm. “Every company that does anything with human health is exploring the microbiome,” says Jack Gilbert, professor and microbiome researcher at the University of California at San Diego. “The microbiome, over the next 5, 10 years—I hope—will lead to a revolution in personalized treatments.” This could span everything from acne medications to cancer immunotherapy.

“The idea that a single microbe is going to be a fix-all for people of different backgrounds seems somewhat simple”

Sorting out the medicine from the proverbial snake oil will involve clinical trials. Currently only a few dozen companies worldwide are conducting them, and AOBiome, like many of the others, has its share of skeptics. Among the doubters is Dunn, the applied-ecology professor and author.

There’s little evidence, he says, that Whitlock’s N. eutropha was ever a permanent resident of our ancestors’ skin. And he doubts that one type of bacteria alone could significantly improve health outcomes. “The idea that a single microbe is going to be a fix-all for people of different lifestyles and context and genetic backgrounds all around the world seems somewhat simple,” he says.

There’s even a risk, he adds, that Whitlock’s bacteria could become an unchecked invasive species:

“One worry is that it becomes the cane toad of the skin and has unanticipated consequences that spread throughout the ecosystem.”

Asked about this possibility, AOBiome says it has performed safety testing and that if anything were to go wrong, its AOB are so slow to reproduce that people would only need to take a soapy shower to kill them.

AOBiome’s double-blind trial for acne will soon enter its final, human-testing phase. The company says its initial findings show that its pharmaceutical-grade spray, which is roughly five times as concentrated as its cosmetic spray, led to a 48 percent reduction in pimples and red bumps, compared with a 32 percent reduction for those who’d used a placebo.

The spray also decreased skin pH, which is considered a beneficial effect, and resulted in a 300-fold decrease in Staphylococcus aureus, a strain known to cause eczema. Preclinical trials for acne also turned up an interesting side effect of Whitlock’s spray: It caused a medically significant drop in blood pressure. To follow up, AOBiome is now conducting clinical trials for an AOB nasal spray.

The company’s six active trials are being funded almost entirely by one investor: Jun Wang, the former CEO of a research center called the Beijing Genomics Institute and the founder of ICarbonX, a Chinese artificial intelligence health company valued at $1 billion. Wang, like other investors, is devoted to Whitlock’s spray and says his friends and family are self-experimenting to see how it holds up against conditions such as migraines and pollution-induced skin woes.

“It has become very popular in my circle,” he says, speaking to me over Skype from China. Now chairman of AOBiome, he says he hopes to turn the Cambridge startup into a pipeline for bacteria-based drugs.

The company is considering whether to set up additional labs in China and has begun generating a diverse library of AOB for further study. “AOB is just the first bacteria we’re working on,” Wang says. “We are thinking about how to do gold mining in the bacteria world.”

On a rainy evening in November, Whitlock meets me at Summer Shack, a giant seafood restaurant off a busy thruway near AOBiome’s office. Outside stands a statue of a New England fisherman, its elongated, blocky proportions resembling those of an Easter Island head. Inside the waiting area, a video demonstrates how to shell a lobster.

Whitlock was never very involved in Mother Dirt (“I’m cosmetic-challenged”), and he says he’s impatient for AOBiome’s clinical trials to prove the theories from his minivan days.

The company’s mission is personal for him. In addition to autism, he suffers from anxiety, depression, hypertension, and post-traumatic stress disorder from being bullied as a child. He’s convinced his bacteria have improved these conditions, although he’s careful to emphasize that he has no clinical proof. “Before, I could never have sat here and talked like this with a stranger,” he tells me. “I want a billion people to use this every day.”

When the waitress comes to take drink orders, Whitlock sticks with water. Alcohol, he explains, might harm the AOB population he’s been cultivating on his skin. “They’re very sensitive,” he says.

Related Articles:

Understanding The Gut Microbiome

Food, The Gut’s Microbiome And The FDA’s Regulatory Framework

Germ-Killing Brands Now Want To Sell You Germs (#GotBitcoin?)

Pocket-Sized Spectrometers Reveal What’s In Our Foods, Medicines, Beverages, etc..

The Complete Guide To The Science Of Circadian Rhythms (#GotBitcoin?)

Billionaire is Turning Heads With Novel Approach To Fighting Cancer (#GotBitcoin?)

Fighting Cancer By Releasing The Brakes On The Immune System (#GotBitcoin?)

Over-Diagnosis And Over-Treatment Of Cancer In America Reaches Crisis Levels (#GotBitcoin?)

Cancer Super-Survivors Use Their Own Bodies To Fight The Disease (#GotBitcoin?)

Microbiome Live News

@metagenomics

Your Questions And Comments Are Greatly Appreciated.

Monty H. & Carolyn A.

Go back

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.