Over-Diagnosis And Over-Treatment Of Cancer In America Reaches Crisis Levels (#GotBitcoin?)

Debate Among Doctors Looks at Whether Zealous Screening Leads to Over-treatment. Over-Diagnosis And Over-Treatment Of Cancer In America Reaches Crisis Levels

Early detection has long been seen as a powerful weapon in the battle against cancer. But some experts now see it as double-edged sword.

While it’s clear that early-stage cancers are more treatable than late-stage ones, some leading cancer experts say that zealous screening and advanced diagnostic tools are finding ever-smaller abnormalities in prostate, breast, thyroid and other tissues. Many are being labeled cancer or precancer and treated aggressively, even though they may never have caused harm.

As a result, these experts say, many people may be undergoing surgery, radiation, chemotherapy and other treatments unnecessarily, sometimes with lifelong side effects.

Meanwhile, an estimated 586,000 Americans will die of cancer this year—many from very aggressive, fast-moving cancers that develop between screenings and spread too quickly to stop.

“We’re not finding enough of the really lethal cancers, and we’re finding too many of the slow-moving ones that probably don’t need to be found,” says Laura Esserman, a breast-cancer surgeon at the University of California, San Francisco.

Dr. Esserman chairs a National Cancer Institute advisory panel that is calling for major changes in how cancer is detected, treated and even talked about. Among its suggestions: devise new screening programs to target the deadliest cancers; create registries to track lower-risk cancers; and remove the term cancer from very slow-growing and precancerous tumors that are unlikely to progress. The panel suggests calling them “indolent lesions of epithelial origin,” or IDLEs, instead.

“Unfortunately, when patients hear the word cancer, most assume they have a disease that will progress, metastasize and cause death,” the group wrote in the journal Lancet Oncology in May. “Many physicians think so as well, and act or advise their patients accordingly.”

The new thinking could bring radical changes to the vast world of cancer care, which accounts for more than $100 billion in medical costs in the U.S. annually. It is being embraced by a growing number of medical associations and major journals.

“The harm of overdiagnosis to individuals and the cost to health systems is becoming ever clearer,” says Fiona Godlee, editor in chief of The BMJ, formerly the British Medical Journal, which is hosting a conference on the topic starting Monday at Oxford University.

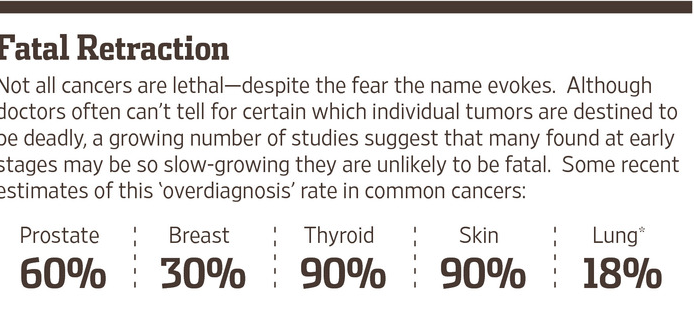

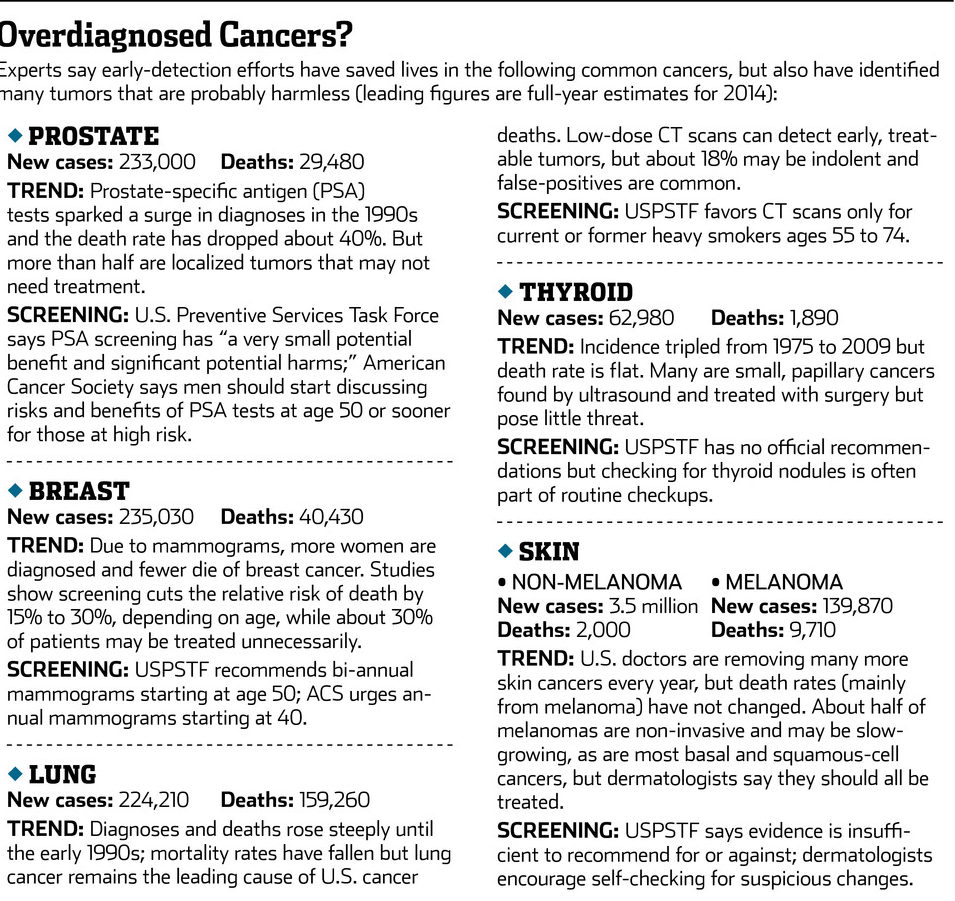

The idea that not all cancers are deadly is already beginning to transform treatment for prostate cancer. As many as 60% of the tumors detected via screening grow so slowly that they pose little threat in a man’s lifetime, experts say, and treating them with surgery or radiation carries a substantial risk of impotence or incontinence. About 15% of patients now opt to monitor them instead—and some experts say more could probably do so safely.

Some urologists even propose calling prostate tumors with a Gleason score of 6 or below “benign lesions”—although others note that that would mean half of the men treated for prostate cancer in the past 20 years didn’t have cancer after all.

Overdiagnosis—the detection of tumors that aren’t likely to cause harm—is now a hot topic in other cancers as well. A growing volume of studies estimate that as many as 30% of invasive breast cancers, 18% of lung cancers and 90% of papillary thyroid cancers may not pose a lethal threat.

—Laura Esserman, A Breast-Cancer Surgeon At The University Of California, San Francisco

More than 2.5 million Americans are diagnosed with non-melanoma skin cancers each year—more than all other cancers combined. They are rarely fatal, and some experts say that removing the term “cancer” would encourage more doctors and patients to monitor the lesions rather than remove them surgically. A commentary in the Journal of the American Medical Association last week noted that more than 100,000 people are treated for basal-cell cancers annually even though they died of other causes within a year. “Clinicians need to take a step back from the microscope and take a look at the patient,” the authors wrote.

Not So Fast

But such calls to rethink the C-word and slow the relentless drive for more and earlier treatments remain highly controversial.

Officials from five major dermatology societies have blasted the idea of calling non-melanoma skin cancers IDLEs, saying that deaths from squamous-cell cancers are rising and basal-cell carcinomas can invade surrounding tissues if untreated. “Renaming a destructive and sometimes fatal disease—to make it sound harmless—is a disservice to our patients,” the doctors wrote in Lancet Oncology.

Brett Coldiron, president of the American Academy of Dermatology, says it’s often the patients who want their skin cancers removed—”and sometimes you get surprised. These things that look like a basal-cell are a melanoma.”

Dr. Esserman and other doctors warning about overdiagnosis have been harshly debated at cancer meetings and have received angry letters from people convinced that early detection saved their lives, or could have saved loved ones.

Some critics say that the whole premise that cancers are over-diagnosed comes from statistical guesses, based on old, flawed studies, and that even if some patients are treated unnecessarily, early detection still saves lives.

“There’s no question that periodic screening doesn’t catch fast-growing cancers, but you save lives by finding moderate and slow-growing cancers and finding them earlier,” says Daniel Kopans, a senior radiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Even doctors who accept the idea of overdiagnosis say it poses a dilemma when it comes to treating individual patients.

“I am confident that somewhere between 10% and 30% of women with localized invasive breast cancer would be just fine if we just watched them,” says Otis Brawley, chief medical officer of the American Cancer Society. “But I cannot look into a patient’s eyes and say, ‘You’re one of the 10% to 30% that should not be treated.’ “

The conflicting messages have left many patients bewildered. After years of educational campaigns saying that early detection saves lives, it’s no wonder that some people view recommendations to cut back on cancer screenings as dangerous, or veiled health-care rationing.

Bitter disputes still rage over a U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation that men no longer use tests for prostate-specific antigen, or PSA, to screen for prostate cancer, and that women have mammograms every other year starting at age 50, rather than annually starting at 40, to reduce the likelihood of overdiagnosis. At Congress’s insistence, the federal health law requires insurers to fully cover annual mammograms starting at 40 as part of “essential health benefits.”

“Everyone says they’d be willing to be overtreated if it means not dying—but that’s a big fallacy,” says Dr. Esserman. “By treating 1,000 people who have low-risk disease, we’re not going to save the one person with aggressive disease.”

Sharks And Goldfish

What makes scientists think some cancers are indolent? One clue comes from autopsies that find a substantial number of breast, thyroid, lung and other tumors that never caused symptoms in people who died of other causes. Small, localized prostate cancers are so ubiquitous in older men that the risk is roughly equal to a man’s age: a 70-year-old has a 70% chance of harboring the disease. Yet the average lifetime risk of dying of prostate cancer is less than 3% according to the American Cancer Society.

Most of the evidence for overdiagnosis comes from statistical analyses of long-term cancer trends. Theoretically, as screening efforts find more early cancers, the death rate from those cancers should decline. Widespread use of colonoscopies and Pap smears has cut the death rate from colon and cervical cancers roughly in half since 1975.

But death rates from thyroid, kidney and skin cancers have stayed flat or increased, despite many more being diagnosed at early stages, leading researchers to conclude that many of those caught early would never have progressed.

Death rates from breast and prostate cancers have fallen by about 30% and about 40%, respectively, in the past 30 years. But experts disagree on whether that is due to the rise of screening mammograms and PSA tests or improved treatments.

“We have thrown the net very, very widely and eliminated some of the sharks,” says Ian Thompson, a urologist at University of Texas Health Science Center and co-chairman of the NCI advisory panel. “But we’ve also netted a lot of goldfish and assumed they’d behave the same way.”

The New War On Cancer

Part of the problem, says Dr. Brawley, is that modern medicine is using a definition of cancer that hasn’t changed since the 1850s, when German pathologists first described various types of the disease based on autopsy specimens. Tiny lesions that would never have been detected a few decades ago are now routinely biopsied and analyzed, he says, “and if it looks just like what killed that woman 160 years ago, we assume it will be deadly today.”

But assuming cells that look the same will behave the same way is the biological equivalent of “racial profiling,” Dr. Brawley adds. Many other factors—including the tumor’s genetic profile and the patient’s immune system, diet and overall health—could affect how fast those cancer cells grow, or conceivably regress. “We desperately need better tests to distinguish the things that will behave like traditional cancers versus the things that look like cancer but won’t,” Dr. Brawley says. “This is the beginning of the new war on cancer in the 21st century.”

Prodigious efforts are under way to devise such tests. The National Cancer Institute’s Early Detection Research Network is bringing together 300 investigators at 40 institutions to study how molecular patterns in screen-detected cancers differ from those that cause symptoms. Biotech firms and university labs are also racing to develop prognostic tools.

Much progress has been made in identifying subtypes of tumors and tailoring treatments to them. “It’s a fallacy to throw up our hands and say we have no idea which patients are low risk,” says breast surgeon Shelley Hwang at Duke University Medical Center, who is also on the NCI panel.

Tests such as Genomic Health Inc.’s Oncotype DX and Agendia Inc.’s MammaPrint analyze patterns of gene activity on breast tumors that have been removed and can help predict how likely the cancer is to recur and whether the patient would benefit from chemotherapy after surgery.

Several new gene tests for prostate cancer have hit the market in the past year. Oncotype DX has a test that works at the biopsy stage and can help doctors assess how aggressive a particular tumor might be.

But clinicians say much more research needs to be done before they can say for certain how any individual cancer will behave. “I think we will get there. I just don’t think we’re there yet,” says Clifford Hudis, chief of breast-cancer medicine at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York and past president of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Peace of Mind

In the absence of certainty, many doctors and patients are opting for more aggressive treatment, not less.

In breast cancer, for example, nearly 20% of women with early-stage tumors now elect to have both breasts removed, up from 3% in 1998

“Patients do this for peace of mind, for symmetry—but there’s no survival benefit for most of them,” says Barbara Smith, director of the breast program at Massachusetts General Hospital.

About one-quarter of the breast cancers diagnosed each year aren’t technically cancers, but abnormal cells confined to milk ducts called “ductal carcinoma in situ” that were seldom noticed before mammography. Experts think only about 20% of DCIS lesions might eventually progress to become invasive cancer. But they don’t know for sure, because virtually all DCIS cases are treated as if they are stage-one cancers, with lumpectomy or mastectomy, often combined with radiation.

“We are picking up on these conditions way before we know whether they are dangerous or not,” says Duke’s Dr. Hwang. “In our ignorance, it’s safest to assume they are all dangerous, but we’re hurting some women in the process.”

Few doctors dare leave DCIS untreated, but Dr. Hwang is leading a multicenter study treating patients who have small, estrogen-positive DCIS lesions with hormone therapy for six months in hopes they can avoid surgery. She hopes to start another study next year offering DCIS patients the option of hormone therapy or active surveillance alone. “We may identity a group of patients we could treat with just a pill rather than mastectomy,” she says.

Risk-Based Screening

Dr. Esserman is embarking on a major study to test a new approach to breast-cancer screening. She hopes to enroll 100,000 women from all five University of California medical centers and Sanford Health in North Dakota. Those with average risk will have mammograms every other year, starting at age 50. Those at higher risk due to genetic variations, family history, dense breast tissue or other factors will be screened—with mammograms and other imaging tests—younger and more often.

“For some people, early detection does save lives—but we need to sort out who that might be,” says Dr. Esserman, who theorizes that after five years, such “risk-based screening” will have netted more high-risk cancers, fewer indolent ones and fewer false positives.

Any breast cancers that are diagnosed will be treated and tracked in registries shared among the universities; women with low-risk DCIS will be offered active surveillance, with or without hormone therapy, as well as surgical options. The risks and benefits will be discussed in depth, and individual choices will be honored.

“For a woman with DCIS who has 6-year-old twins and a mother who died of breast cancer, the right option might be radical bilateral mastectomy,” says Dr. Esserman. “For someone who is 86 years old and has multiple co-morbidities, surveillance may be.”

Some critics, including Dr. Kopans, warn that risk-based screening could be risky, since about 75% of women diagnosed with breast cancers had no known risk factors.

Says Dr. Esserman: “We need to start testing some of these ideas, rather than just fighting over them. People are afraid to do less. We want to figure out how to do less safely.”

Related Article:

Fighting Cancer By Releasing The Brakes On The Immune System (#GotBitcoin?)

Your questions and comments are greatly appreciated.

Monty H. & Carolyn A.

Go back

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.