Ultimate Resource On California’s (And Other States, Countries) User Data Privacy Laws

The statute was meant to standardize how companies disclose their consumer data-mining practices. So far, not so much. Ultimate Resource On California’s (And Other States, Countries) User Data Privacy Laws

Millions of people in California are now seeing notices on many of the apps and websites they use. “Do Not Sell My Personal Information,” the notices may say, or just “Do Not Sell My Info.”

But what those messages mean depends on which company you ask.

Even now, privacy and security experts from different companies are debating compliance issues over private messaging channels like Slack.

The provision about selling data, for example, applies to companies that exchange the data for money or other compensation. Evite, an online invitation service that discloses some customer information for advertising purposes, said it would give people a chance to opt out if they do not want their data shared with third parties. By contrast, Indeed, a job search engine that shares users’ résumés and other information, posted a notice saying that people seeking to opt out “will be asked to delete their account.”

The issue of selling consumer data is so fraught that many companies are unwilling to discuss it publicly. Oracle, which has sold consumer information collected by dozens of third-party data brokers, declined to answer questions. T-Mobile, which has sold its customers’ location details, said it would comply with the law but refused to provide details.

“Companies have different interpretations, and depending on which lawyer they are using, they’re going to get different advice,” said Kabir Barday, the chief executive of OneTrust, a privacy management software service that has worked with more than 4,000 companies to prepare for the law.

“I’ll Call It A Religious War.”

The new law has national implications because many companies, like Microsoft, say they will apply their changes to all users in the United States rather than give Californians special treatment. Federal privacy bills that could override the state’s law are stalled in Congress.

The California privacy law applies to businesses that operate in the state, collect personal data for commercial purposes and meet other criteria like generating annual revenue above $25 million. It gives Californians the right to see, delete and stop the sale of the personal details that all kinds of companies — app developers, retailers, restaurant chains — have on them.

“Businesses will have to treat that information more like it’s information that belongs, is owned by and controlled by the consumer,” said Xavier Becerra, the attorney general of California, “rather than data that, because it’s in possession of the company, belongs to the company.”

Some issues, like the practices that qualify as data selling, may be resolved by mid-2020, when Mr. Becerra’s office plans to publish the final rules spelling out how companies must comply with the law. His office issued draft regulations for the law in October. Other issues may become clearer if the attorney general sues companies for violating the privacy law.

For now, even the biggest tech companies have different interpretations of the law, especially over what it means to stop selling or sharing consumers’ personal details.

Google recently introduced a system for its advertising clients that restricts the use of consumer data to business purposes like fraud detection and ad measurement. Google said advertisers might choose to limit the uses of personal information for individual consumers who selected the don’t-sell-my-data-option — or for all users in California.

Facebook, which provides millions of sites with software that tracks users for advertising purposes, is taking a different tack. In a recent blog post, Facebook said that “we do not sell people’s data,” and it encouraged advertisers and sites that used its services “to reach their own decisions on how to best comply with the law.”

Uber responded to Facebook’s notice by offering a new option for its users around the world to opt out of having the ride-hailing service share their data with Facebook for ad targeting purposes.

“Although we do not sell data, we felt like the spirit of the law encompassed this kind of advertising,” said Melanie Ensign, the head of security and privacy communications at Uber.

Evite, the online invitation service, decided in 2018 to stop selling marketing data that grouped its customers by preferences like food enthusiast or alcohol enthusiast. Since then, the company has spent more than $1 million and worked with two firms to help it understand its obligations under the privacy law and set up an automated system to comply, said Perry Evoniuk, the company’s chief technology officer.

Although Evite no longer sells personal information, the site has posted a “do not sell my info” link. Starting Wednesday, Mr. Evoniuk said, that notice will explain to users that Evite shares some user details — under ID codes, not real names — with other companies for advertising purposes.

Evite will allow users to make specific choices about sharing that data, he said. Customers will also be able to make general or granular requests to see their data or delete it.

“We took a very aggressive stance,” Mr. Evoniuk said. “It’s beneficial to put mechanisms in place to give people very good control of their data across the board.”

Companies are wrangling with a part in the law that gives Californians the right to see the specific details that companies have compiled on them, like precise location information and facial recognition data. Residents may also obtain the inferences that companies have made about their behavior, attitudes, activities, psychology or predispositions.

Apple, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Twitter and many other large tech companies already have automated services enabling users to log in and download certain personal data. Amazon said it would introduce a system that allowed all customers of its United States site to request access to their personal information.

But the types and extent of personal data that companies currently make available vary widely.

Apple, for instance, said its privacy portal allowed people whose identities it could verify to see all of the data associated with their Apple IDs — including their App Store activities and AppleCare support history.

Microsoft said its self-service system enabled users to see the most “relevant” personal information associated with their accounts, including their Bing search history and any interest categories the company had assigned them.

Lyft, the ride-hailing company, said it would introduce a tool on Wednesday that allowed users to request and delete their data.

A reporter who requested data from the Apple portal received it more than a week later; the company said its system might need about a week to verify the identity of a person seeking to see his or her data. Microsoft said it was unable to provide a reporter with a list of the categories it uses to classify people’s interests. And Lyft would not say whether it will show riders the ratings that drivers give them after each ride.

Experian Marketing Services, a division of the Experian credit reporting agency that segments consumers into socioeconomic categories like “platinum prosperity” and “tough times,” is staking out a tougher position.

In recent comments filed with Mr. Becerra’s office, Experian objected to the idea that companies would need to disclose “internally generated data about consumers.” Experian did not return emails seeking comment.

The wide variation in companies’ data-disclosure practices may not last. California’s attorney general said the law clearly requires companies to show consumers the personal data that has been compiled about them.

“That consumer, so long as they follow the process, should be given access to their information,” Mr. Becerra said. “It could be detailed information, if a consumer makes a very specific request about a particular type of information that might be stored or dispersed, or it could be a general request: ‘Give me everything you’ve got about me.’”

Updated: 5-5-2021

Facebook And Others Should Pay Us For Our Data. Here’s One Way

A California group proposes taxing data companies on their “data dependency.”

It’s obvious that data companies make profits by using their customers’ data without paying for it. What’s not obvious is how to get them to cough up. Ten cents for every dog or cat picture you post on Facebook? Five dollars a month for your searches on Google?

A new white paper from an ad hoc group of scholars says paying individuals based on their usage is the wrong way to go about it. Customer data becomes valuable when billions of bits of it are aggregated and analyzed. So governments should tax data companies based on their dependence on user data, and then, rather than parceling out cash to individuals, they should spend the revenue on projects that serve the general public, the scholars say.

“The value of your data is only unlocked when it is combined with data from others,” says the 39-page white paper. “To design a data dividend,” it says elsewhere, “we must think in terms of ‘our data,’ not ‘my data.’”

The white paper is being published by the Berggruen Institute, a Los Angeles-based nonprofit dedicated to reshaping political and social institutions. I was given an advance copy. I will add a link to this column when one is available.

Data companies and their shareholders won’t like the scholars’ recipe. “Taxation is a tool to transform platform companies from private monopolies to regulated utilities in a manner similar to the way other natural monopolies such as electricity and water have been regulated since the early twentieth century,” they write.

Their paper also envisions the creation of a Data Relations Board, which would function like an environmental protection agency but for data, and a series of “public data trusts” that would contain data for public use. Companies that contributed their data to public data trusts would get a break on their data taxes.

Yakov Feygin, an economist who is associate director of Berggruen’s Future of Capitalism program, coordinated the research project. The other authors are Matthew Prewitt, a lawyer who is president of the RadicalxChange Foundation; Brent Hecht, a computer scientist at Northwestern University; a pair of Ph.D. students at Northwestern, Hanlin Li and Nicholas Vincent; Chirag Lala, a Ph.D. student at the University of Massachusetts; and Luisa Scarcella, a postdoctoral researcher at UAntwerpen DigiTax Center in Belgium.

The scholars admit that they can’t perfectly measure a company’s data dependency. They propose going by its number of users as a proxy for now, with an eye toward other approaches when better measurement technology is available, such as measuring the quantity of user data a company stores or uses.

The white paper is directed mainly to the state government of California. Feygin says in an interview that he got interested in the topic after Governor Gavin Newsom came out in favor of a “data dividend” in his State of the State speech in February 2019, without fleshing out the concept.

“We kind of answered the call,” Feygin says. “We wrote it in a California context because the idea came up here first,” but it could be adopted by other states and nations, he adds. He says it’s an improvement on the digital services taxes that several nations have adopted to capture tax revenue from the American tech giants because it’s based on companies’ data dependence rather than revenue.

“This is a long process. There are still a lot of questions that need to be worked out,” Feygin says. “Our focus is on a decade, not the next year.”

Updated: 5-6-2021

Over 20 Organizations Form Alliance To Focus On Data Privacy And Monetization

With privacy becoming increasingly important, the DPPA wants to help figure out ways to address the issue at scale.

Over 20 businesses worldwide have created the Data Privacy Protocol Alliance (DPPA). DPPA said Wednesday it intends to build a decentralized blockchain-based data system it hopes will compete against data monopolies such as Google or Facebook by allowing users to take control of their own data.

Specifically, the Data Privacy Protocol Alliance will develop a set of guidelines and specifications for a version of CasperLabs’ layer one blockchain “optimized for data sharing, data storage, data ownership and data monetization,” according to the announcement.

The Casper Network is a proof-of-stake network where businesses can build private or permissioned applications. The network also claims to offer upgradeable smart contracts, predictable gas fees and the ability to support scale.

Speaking at the founding members meeting on May 4, Ivan Lazano, head of product at DPPA founding member BIGtoken, presented an initial proposal. He said any system should include being able to support tools like a data wallet that gives users control over their data and who monetizes it, It should also include non-commercial data storing and sharing capabilities. He also said any data privacy system should also let commercial users onboard, verify and handle large data sets, among other areas.

“Together, we’re creating an ecosystem with the technology and scale to compete with the centralized data monopolies,” said Lou Kerner, CEO of BIGtoken, in a statement. “The DPPA will enable true data ownership and provide consumers the tools and transparency to individually choose how their data is shared and monetized.”

In practice, the DPPA will look to become a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO) that will govern the protocol to optimize data sharing, data storing, data ownership and data monetization.

The Data Privacy Appeal

The promise of data protections and privacy has long been a driving force in the appeal of decentralized systems. The removal of a centralized body that hoards user data – and could use or even abuse it – changes the dynamics for consumers. The companies focusing on these sorts of projects also tend to see increased interest from funders.

For example, Permission.io, one of the founding members of the DPPA, offers a platform that incentivizes users to grant advertisers and other merchant participants access to their time and data in a peer-to-peer way. The company has raised over $50 million. Similarly, the programmable privacy startup Aleo recently raised $28 million.

With privacy becoming increasingly important, the DPPA represents another stab at figuring out ways to address the issue at scale.

According to a recent survey from opt-in data marketplace BIGtoken, 78% of the 35,000 consumers queried said that they’re somewhat concerned or extremely concerned about their data privacy.

Founding members of the DPPA are located in the U.S., Singapore, the U.K. and Israel. The organization includes data aggregators, privacy advocates, brands, agencies and advertising platforms.

“In a world with all-time high unemployment rates, where people are struggling to meet their basic needs, personal data monetization can allow individuals to earn enough money to at least feed themselves and their families, securing their basic human rights. This is where data ownership is truly revolutionary,” said Brittany Kaiser, co-founder of the Own Your Data Foundation, another founding organization of the DPPA, in a statement.

Kaiser was previously a whistle-blower at Cambridge Analytica, notorious for its scandal involving the use of Facebook data for political purposes.

Updated: 5-9-2021

Privacy Chiefs Say Patchwork Data Laws Mean Lawyers Must Work Alongside Engineers

Having specialist staff involved from the start of projects eases compliance burden, executives say.

Ensuring compliance with data protection laws has become so complicated that companies must make room for regulatory and ethics experts in product engineering processes, privacy executives say.

These laws can present a potential risk without a clear process for making sure new products and services comply with them, said Ruby Zefo, chief privacy officer at ride-hailing company Uber Technologies Inc.

“I can’t tell you how important it is to leverage existing processes so that your engineers and your product people only have to go to one place,” she said while speaking at the WSJ Risk and Compliance Forum on Wednesday.

The patchwork of rules governing privacy can range from state legislation to international laws, such as the European Union’s 2018 General Data Protection Regulation, and carry severe penalties.

Companies that violate the GDPR, for instance, can face fines of up to 4% of their global revenue, or €20 million ($24 million), whichever is higher. Certain state laws, including the California Consumer Privacy Act, also allow individuals to sue companies and form class-action lawsuits over privacy breaches.

At Uber, Ms. Zefo said, projects undergo a review process where information is distributed to the appropriate people to ensure compliance with relevant regulations.

“It comes into a system that will both cover the engineering side and the legal side,” she said.

At financial-services company Visa Inc., the process is similar, said Kelly Mahon Tullier, the company’s chief legal and administrative officer, at the same event. Privacy and legal officials are involved from the start of projects, such as those involving artificial intelligence for antifraud tools, she said.

The team asks questions about what data are involved, which geographies will be covered and whom engineers are working with to ensure that the right compliance obligations are met.

“The laws are different in different places, which makes it challenging,” she said. “So all of those tools come through us regularly, to make sure that we’re at the table.”

Having legal and privacy personnel involved doesn’t mean slowing innovation, Ms. Zefo said, adding that it can sometimes simplify projects.

For example, Uber deployed a new tool during the pandemic to ensure that drivers were wearing masks.

The initial thought would have been to use facial-recognition technology, but her team and the product team quickly realized that a simple selfie submitted to an object-detection system met the need.

Having legal and privacy staff involved from the start meant that they were able to build the tool around a shared philosophy, Ms. Zefo said.

“Let’s make it simple, elegant, efficient, and not overly invasive,” she said.

Update: 7-25-2021

Facebook, Twitter, Google Threaten To Quit Hong Kong Over Proposed Data Laws

Industry group representing companies says proposed anti-doxing rules could put staff based locally at risk of criminal charges.

Facebook Inc., Twitter Inc. and Alphabet Inc.’s GOOG 1.33% Google have privately warned the Hong Kong government that they could stop offering their services in the city if authorities proceed with planned changes to data-protection laws that could make them liable for the malicious sharing of individuals’ information online.

A letter sent by an industry group that includes the internet firms said companies are concerned that the planned rules to address doxing could put their staff at risk of criminal investigations or prosecutions related to what the firms’ users post online. Doxing refers to the practice of putting people’s personal information online so they can be harassed by others.

Hong Kong’s Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau in May proposed amendments to the city’s data-protection laws that it said were needed to combat doxing, a practice that was prevalent during 2019 protests in the city. The proposals call for punishments of up to 1 million Hong Kong dollars, the equivalent of about $128,800, and up to five years’ imprisonment.

“The only way to avoid these sanctions for technology companies would be to refrain from investing and offering the services in Hong Kong,” said the previously unreported June 25 letter from the Singapore-based Asia Internet Coalition, which was reviewed by The Wall Street Journal.

Tensions have emerged between some of the U.S.’s most powerful firms and Hong Kong authorities as Beijing exerts increasing control over the city and clamps down on political dissent. The American firms and other tech companies last year said they were suspending the processing of requests from Hong Kong law-enforcement agencies following China’s imposition of a national security law on the city.

Jeff Paine, the Asia Internet Coalition’s managing director, in the letter to Hong Kong’s Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data, said that while his group and its members are opposed to doxing, the vague wording in the proposed amendments could mean the firms and their staff based locally could be subject to criminal investigations and prosecution for doxing offenses by their users.

That would represent a “completely disproportionate and unnecessary response,” the letter said. The letter also noted that the proposed amendments could curtail free expression and criminalize even “innocent acts of sharing information online.”

The Coalition suggested that a more clearly defined scope to violations be considered and requested a videoconference to discuss the situation.

A spokeswoman for the Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data acknowledged that the office had received the letter. She said new rules were needed to address doxing, which “has tested the limits of morality and the law.”

The government has handled thousands of doxing-related cases since 2019, and surveys of the public and organizations show strong support for added measures to curb the practice, she said. Police officers and opposition figures were doxed heavily during months of pro-democracy protests in 2019.

“The amendments will not have any bearing on free speech,” which is enshrined in law, and the scope of offenses will be clearly set out in the amendments, the spokeswoman said. The government “strongly rebuts any suggestion that the amendments may in any way affect foreign investment in Hong Kong,” she said.

Representatives for Facebook, Twitter and Google declined to comment on the letter beyond acknowledging that the Coalition had sent it. The companies don’t disclose the number of employees they have in Hong Kong, but they likely employ at least 100 staff combined, analysts estimate.

China’s crackdown on dissent since it imposed a national security law a year ago has driven many people in Hong Kong off social media or to self-censor their posts following a spate of arrests over online remarks.

While Hong Kong’s population of about 7.5 million means it isn’t a major market in terms of its user base, foreign firms often cite the free flow of information in Hong Kong as a key factor for being located in the financial hub.

The letter from the tech giants comes as global companies increasingly consider whether to leave the financial center for cities offering more hospitable business climates.

The anti-doxing amendments will be put before the city’s Legislative Council and a bill is expected to be approved by the end of this legislative year, said Paul Haswell, Hong Kong-based head of the technology, media, and telecom law practice at global law firm Pinsent Masons.

The tech firms’ concerns about the proposed rules are legitimate, Mr. Haswell said. Depending on the wording of the legislation, technology companies headquartered outside Hong Kong, but with operations in the city, could see their staff here held responsible for what people posted, he said.

A broad reading of the rules could suggest that even an unflattering photo of a person taken in public, or of a police officer’s face on the basis that this would constitute personal data, could run afoul of the proposed amendments if posted with malice or an intention to cause harm, he said.

“If not managed with common sense,” the new rules “could make it potentially a risk to post anything relating to another individual on the internet,” he said.

Updated: 8-1-2021

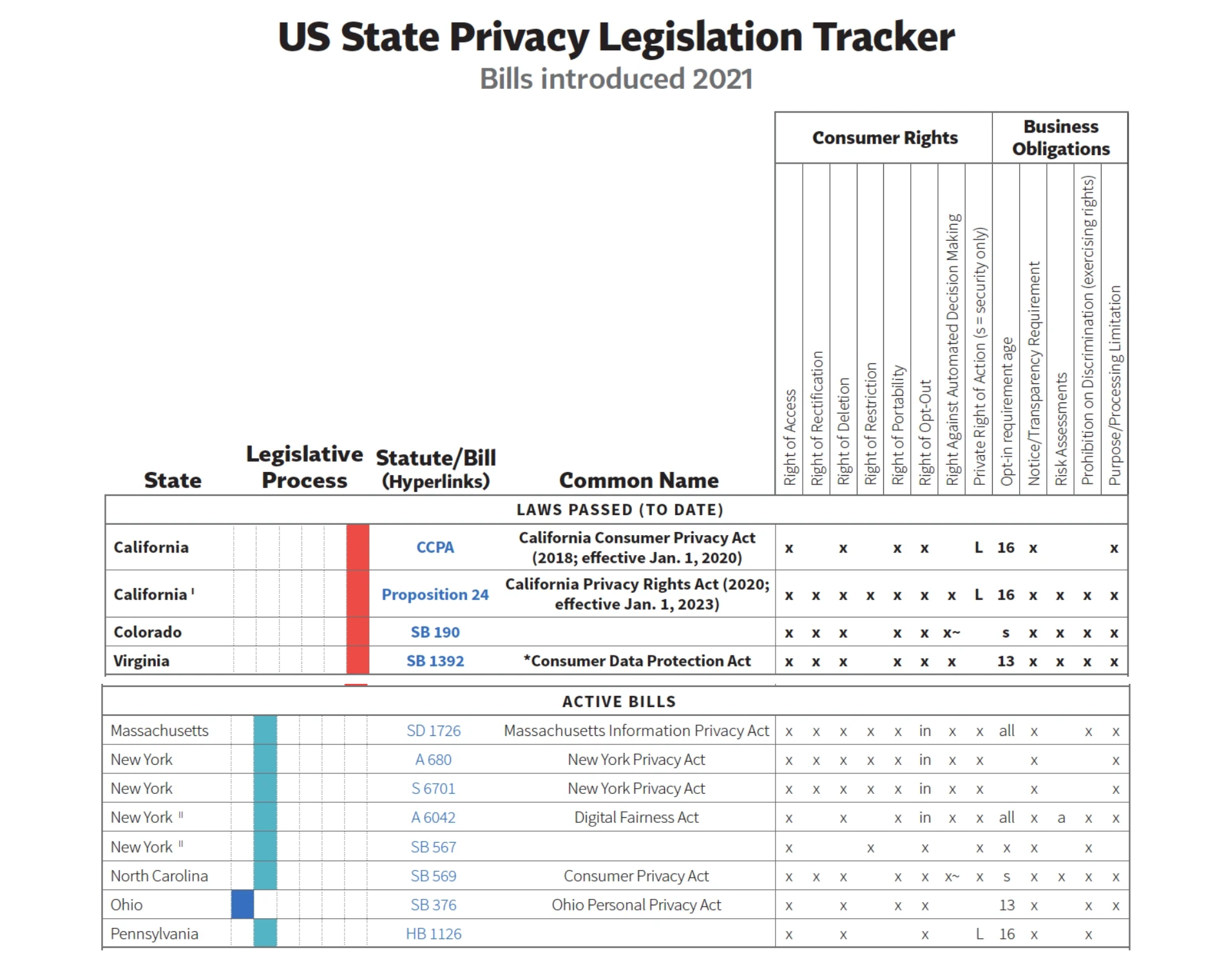

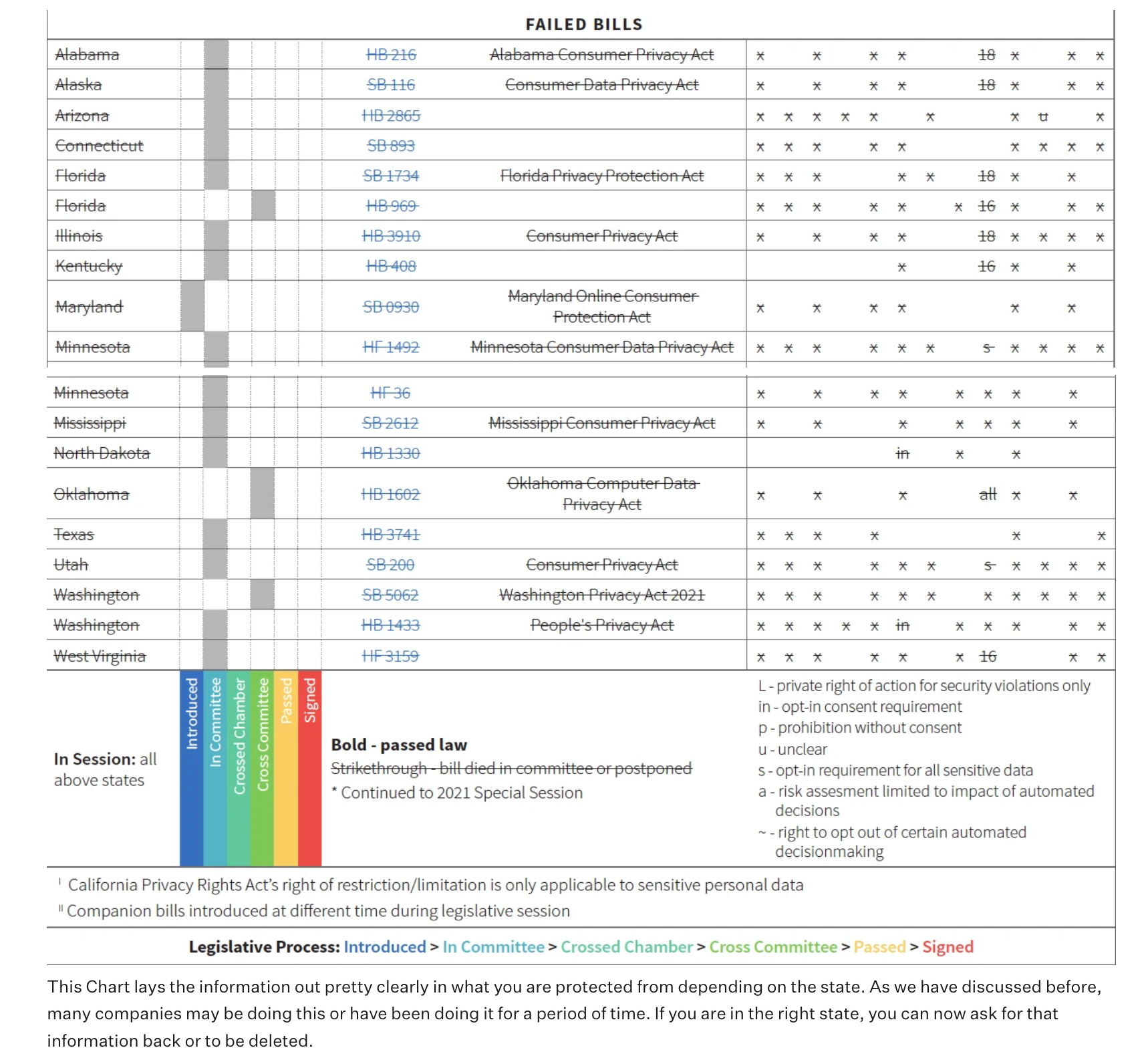

State Privacy Laws In The USA

In the last couple of years within the United States of America, several states have recently enacted new legislation to address advances in cybersecurity, medical privacy, and other privacy-related laws.

More than a quarter of the states in the United States have introduced comprehensive data privacy legislation. However, only a few of the state’s proposed legislation have advanced to the cross-chamber or cross-committee level, which means they have been debated in their respective state legislatures and are close to being signed into law.

See The Below Chart For A Number Of The Proposed Privacy Laws, Their Current Status, And What Rights They Protect:

This Chart lays the information out pretty clearly in what you are protected from depending on the state. As we have discussed before, many companies may be doing this or have been doing it for a period of time. If you are in the right state, you can now ask for that information back or to be deleted.

The Following Are More Specifics On States That Have Passed Privacy Related Legislation:

California

Expands The Protections For Personal Information Held By Consumers. Allows Customers To:

Businesses should not be allowed to share personal information.

Access Any Personal Information

Limit the use of “sensitive personal information” by enterprises, including precise geolocation, race, ethnicity, religion, genetic data, private communications, sexual orientation, and specific health data.

Delete Any Personal Information

Creates the California Privacy Protection Agency, which will be responsible for enforcing and enforcing consumer privacy laws and imposing fines. Changes the requirements that enterprises must meet to comply with the law. Maximum penalties for offenses involving consumers under the age of 16 are tripled.

Virginia

The second after the California legislation, Establishes a framework for the Commonwealth’s control and processing of personal data. The law applies to anybody who does business in the Commonwealth and either.

Does Business With At Least 100,000 Virginia Residents Within A Calendar Year

Generate over 50% of total revenue from the sale of personal data.

This law is based off of California’s Consumer Privacy Act, while additionally the law establishes obligations for data controllers and processors, as well as privacy protection measures. Consumers have the right to access, rectify, delete, and receive a copy of their data and opt-out of personal data processing for targeted advertising under the legislation. Finally, that any company or “controller” must receive explicit consent before processing a customer’s data.

Colorado

The Colorado Privacy Law Sb-190, Has Similar Traits To That Of California’s But Also Adds The Following:

Right To Correct Any Personal Information

Right To Receive A Copy Of Your Personal Data In A Portable Form

Right to opt out of profiling (also known as a company creating a “profile” based on your economic background, health, etc.)

This law is another great step in Consumer and Personal Information being put back into the hands of everyone.

Nevada

Nevada should be mentioned as it is a step in this direction, but ultimately,

“Companies are still allowed to share personally identifiable information with their own business affiliates and, for an individual to be eligible to opt out, a business must intend to actually sell the data.” Read More

While also Requires an operator(a person who owns or operates a commercial Internet website or online service or gathers and stores specific information about Nevada residents) to set up a designated request address where a consumer can send a verified request instructing the operator not to sell any covered information gathered about them.

Going Forward

A lot of what we do is because we think that your Privacy should be a given. Unfortunately, in this day and age, many companies took advantage of early loopholes to store data on their current and future consumers.

We believe that these states are just the beginning and we hope that all states will follow suit.

Until then, we’re here to help.

Storing your device in a Faraday Sleeve ensures that these companies can stop tracking your habits, and deriving data that tells them where you live, where you go, how long you stay at places, and more.

Updated: 8-6-2021

Complete Guide to Privacy Laws In The US

Contrary to conventional wisdom, the US does indeed have data privacy laws. True, there isn’t a central federal level privacy law, like the EU’s GDPR. There are instead several vertically-focused federal privacy laws, as well as a new generation of consumer-oriented privacy laws coming from the states.

Let’s take a tour of the US privacy laws and get a feel for the landscape. If you want to learn still more about the US legal landscape, download our amazing The Essential Guide to US Data Protection Compliance and Regulations.

Click Here For More Information

Updated: 8-17-2021

China Set To Pass One Of The World’s Strictest Data-Privacy Laws

New curbs come as citizens grow increasingly concerned about tech giants’ nosiness.

The world’s leading practitioner of state surveillance is set to usher in a far-reaching new privacy regime.

China’s top legislative body is expected this week to pass a privacy law that resembles the world’s most robust framework for online privacy protections, Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation. But unlike European governments, which themselves face more public pressure over data collection, Beijing is expected to maintain broad access to data under the new Personal Information Protection Law.

The national privacy law, China’s first, is being reviewed as frustration grows within the government, and in Chinese society at large, over online fraud, data theft and data collection by Chinese technology giants. The law is on its third round of reviews, usually the last before passage.

The law will require any organization or individual handling Chinese citizens’ personal data to minimize data collection and to obtain prior consent, according to the latest published draft. It covers government agencies, though lawyers and policy analysts say enforcement is likely to be tighter on the private sector.

While privacy in Europe and the U.S. is generally understood to mean protection from both private companies and the government, in China the government has aligned itself with consumers to fight data theft and privacy infringement, says Kendra Schaefer, a partner at Beijing-based consulting firm Trivium China.

“When the government makes laws about privacy, it’s not necessarily restricting its own access,” she said.

The new draft law is a positive development in the eyes of Chinese citizens like Wu Shengwei, a lawyer who sued a Chinese video-streaming company last year after it revealed his personal movie-watching history during a separate lawsuit over membership fees.

Such tech giants “believe they can do whatever they want with user information,” Mr. Wu said in an interview. “This kind of thinking is very serious, very wrong.”

Over the past year, Chinese regulators have reined in the tech sector on several fronts, from antitrust to data security. The privacy law is expected to be a key component of the new landscape for tech companies that had previously enjoyed largely unfettered access to user data. It will unify a hodgepodge of rules, making punishment easier.

“For China’s technology firms, the era of free data collection and usage in China—as in, free of responsibilities and at no cost—is over,” said Winston Ma, an adjunct professor at New York University’s School of Law, adding that the new law, combined with other regulations, will slow tech companies’ “unencumbered growth.”

The Chinese public has increasingly called for a tightening of data collection. For years, loose rules on accessing data, combined with pervasive government surveillance, led some internet users to describe their online activity as “running naked.”

In 2018, Robin Li, the chief executive officer of Chinese search giant Baidu Inc., framed the issue bluntly when he told audience members at a high-level forum that Chinese people in many situations were willing to “trade privacy for convenience, safety or efficiency.”

The comments sparked controversy at the time, and public awareness has only grown since then, say lawyers in China. Mr. Li has since said that Baidu uses only personal data that users agree to provide.

In urban residential compounds around the country, where cameras equipped with facial-recognition technology have proliferated to verify residents and visitors, complaints from tenants have spurred local governments to take action against property managers, such as banning the collection of biometric data without consent. Last month, China’s highest court instructed managers to offer alternatives for residents who don’t want to submit to facial recognition.

Others have taken companies to court. In 2019, Chinese law professor Guo Bing mounted what was widely seen as the first legal challenge against facial-recognition technology, suing a local zoo for requiring members to register their faces as part of a new entrance system.

Last November, the judge ordered the zoo to compensate Mr. Guo the equivalent of $160 for “the loss of contractual benefits and transportation costs.” The yearly membership had cost about $210.

Occasionally authorities are the target of privacy complaints. In the spring, a mobile application developed by a bureau within China’s Ministry of Public Security to combat online fraud by screening calls and messages incited a backlash for collecting data that included identification numbers and home addresses.

In the southern city of Shenzhen, some residents took to China’s Twitter-like Weibo platform to complain that schools were pushing students and parents to register for the app, and vaccination centers in two districts told The Wall Street Journal by phone that they had been visited by police officers to ensure people downloaded the app before getting their shots.

If app data is leaked, one user wrote in a review on China’s Apple App Store, “I can only get plastic surgery, change my name, change my phone, and get a fake ID.”

The new draft law bars government organizations from collecting data beyond what is needed to perform “legally prescribed duties.” But that is unlikely to affect police surveillance and tracking, said Jeremy Daum, a senior fellow at the Yale Law School Paul Tsai China Center. China’s new law, like its European counterpart, doesn’t explicitly mention police use.

“The theory is that the government is there to protect your rights, so it can be trusted not to violate them—it will only use your data as necessary for public safety,” said Mr. Daum. Whether or not there are meaningful checks on that is another matter, he added.

Public safety is a vague and expansive notion in China, affording the government broad powers to monitor citizens. In the northwest Xinjiang region, where a network of internment camps and prisons has been built to subdue local ethnic minorities, surveillance cameras are ubiquitous. An ID swipe and facial scan are needed just to gas up a car.

The trade-off remains palatable to many citizens.

Deng Yufeng, a Beijing artist who mapped security cameras in the capital last November to highlight their ubiquity, said he could see where Baidu’s CEO was coming from when he implied that Chinese people cared less about privacy that security and convenience. Indeed, on a personal level, he said, surveillance cameras make him feel safer.

“Perhaps, on this Earth, we are willing to sacrifice some of our privacy for safety,” said the artist. “But that is only my personal opinion…I don’t represent the Chinese people.”

Updated: 9-3-2021

U.K. Asks Companies To Tweak Internet Privacy Language So Kids Can Understand

New Children’s Code requires clearer explanations and promotes use of diagrams and cartoons.

Websites and apps have to comply with a new set of guidelines on privacy warnings for children, a part of the U.K.’s effort to create a safer and better online environment for users under 18 years of age.

Age Appropriate Design Code, also known as the Children’s Code, requires companies that target children to comply with its 15 standards, including turning off geolocation tracking by default, or face penalties for unclear or convoluted messaging around data sharing. The measures are part of the data-protection requirements enshrined in U.K. law.

The code’s transparency standard, for instance, recommends that companies use clear and plain language in privacy agreements and provide child-friendly, “bite-sized” explanations about how they use personal data at the point that use is activated. It encourages the use of diagrams, cartoons, graphics, video and audio content—as well as games and interactive content—to explain the meanings of privacy and data policies rather than relying on written communications only.

The code also recommends that websites and apps for those who are too young to read or comprehend the concept of privacy should provide audio and video prompts telling kids not to touch or change privacy settings, or get help from an adult if they initiate such changes. Another rule forbids the use of pop-up nudges that may encourage a child to hand over more data while in the moment by using clever design—such as a large “yes” button that distracts the eye away from the corresponding “no.”

The code is being implemented to protect British children, but its repercussions are expected to be further reaching. The rules, written to ensure companies abide by laws set out in the 2018 Data Protection Act, apply to both domestic and foreign companies that process personal data of children in the country, and websites and apps that aren’t explicitly designed for those under 18 but are still used by them must also comply, the commissioning body said.

Companies found to be in breach of the code may be subject to the same penalties as those that break the European General Data Protection Regulation, known as GDPR, which include fines of up to 4% of global revenue.

Several large social media companies, including Alphabet Inc.’s Google and ByteDance Ltd.’s TikTok, in the past month have made changes to their global privacy agreements and interfaces with younger users in mind, without making explicit reference to the Children’s Code.

Google last month said it would be introducing easy-to-understand reading materials for young people and their parents to improve their understanding of the search giant’s data practices. These include guides on privacy written for three age groups: ages 6-8, 9-12 and 13-17.

Its YouTube platform said it would adjust its default upload setting to the most private option for users aged 13-17 and turn off autoplay by default for those users.

Facebook, which owns the apps Instagram and Messenger, said it is working with experts in the fields of online safety, child development, child safety and mental health to develop new products and features for young people, after introducing new features that discourage minors from interacting with adults they don’t know.

TikTok this week announced a new feature that will prompt parents and guardians of teens to find out more about the platform’s privacy and safety settings, and help explain them to their children.

“Anything that is encouraging children and teens to better understand the cycle of use of our personal data is important, because even most adults don’t understand how all the data is used, and how much of it is collected,” said Caitriona Fitzgerald, deputy director of the Electronic Privacy Information Center, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit focused on privacy issues.

The hefty penalty and the costs associated with product redesigns to accommodate the code may deter some small businesses based outside of the U.K. from launching in the market, at least until it is clear how adherence to the code will be policed, said Tyler Newby, a privacy and cybersecurity lawyer at Fenwick & West LLP.

The code’s broad application may also push companies to rethink the use of unwieldy policy agreements for adults too, he said. It could spark a new kind of focus group: Children reading privacy agreements and noting what they can and can’t comprehend.

“Otherwise it’s a bunch of adult lawyers sitting around wondering what a kid understands,” Mr. Newby said.

Rep. Kathy Castor (D., Fla.) in July submitted a bill in Congress that includes elements of the Children’s Code, in a bid to strengthen the U.S. Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act, or Coppa, which came into effect in 2000 to give parents control over what information is collected from their children online. Sens. Ed Markey (D., Mass.) and Bill Cassidy (R., La.) in May introduced a similar legislative update called the Children and Teens’ Online Privacy Protection Act.

Updated: 9-10-2021

U.S. And EU Advance Talks To Preserve Data Transfers

Facebook and many other companies might need a deal to continue operating across the Atlantic Ocean.

U.S. and the European Union officials are making progress on keeping data flowing across the Atlantic, according to people familiar with negotiations that are vital to Facebook Inc. and thousands of other companies.

In talks that will continue next week in Brussels after a round in the U.S. this summer, the two sides hope to avert a disruption of company data transfers by resolving a long-running conflict between strict EU privacy laws and U.S. surveillance measures.

A U.S. delegation, led by officials from the National Security Council and including other branches, will meet with EU officials in the aim of nearing a deal on conditions to allow companies to continue storing and accessing personal information about Europeans on U.S. soil, according to people familiar with the matter.

Talks are likely to continue after the Brussels negotiations, the people said.

Among the main areas of discussion are creating ways to give Europeans effective means to challenge American government surveillance, the people said.

The two sides are “working together to advance our commitment to privacy, protect data and prevent disruptions that will hurt American businesses and families here at home,” a White House official said.

Any progress would be a relief to thousands of multinational companies, in particular big tech companies. An EU court ruling last summer restricted how companies can send personal information about Europeans to the U.S., in part because the court found that Europeans have no effective legal redress in the U.S.

Last fall, Ireland’s privacy regulator issued Facebook, which has its EU headquarters in Dublin, a preliminary draft order to suspend its transfers of European user data to the U.S., citing the court ruling. Facebook lost a procedural challenge to block finalization of that order earlier this year, but is still arguing before the Irish privacy regulator that it complies with the EU court decision.

The company has warned in securities filings that, unless the EU and U.S. can strike a deal, enforcement of the Irish draft order could render it “unable to operate material portions of our business in Europe.”

“How data can move around the world remains of significant importance to thousands of European and American businesses that connect customers, friends, family and employees across the Atlantic,” a Facebook spokesman said, adding that the company provides appropriate safeguards for user data.

Legal experts have said the logic in Ireland’s preliminary draft order could apply to other large tech companies that are subject to U.S. surveillance laws, such as cloud services and email providers, potentially leading to widespread disruption of trans-Atlantic data flows. At stake are potentially billions of dollars of business in the cloud-computing, social-media and advertising industries.

Portugal’s privacy regulator in April ordered the national statistics agency to stop sending census data to the U.S., where it was being processed by Cloudflare Inc.

Privacy concerns have dogged the commercial relationship between Europe and the U.S. since the late 1990s. Under EU law, information about Europeans can’t be sent overseas unless the country where it is being sent is deemed to give the same level of protection as the EU.

The U.S. has never made that cut, but to keep data flows alive, the EU two decades ago struck a special deal with the U.S. to allow companies to keep sending data if they opt into a program to apply EU privacy principles, enforced by the U.S. Federal Trade Commission.

In 2015, that deal, dubbed Safe Harbor, was invalidated by the EU’s top court because U.S. surveillance laws would expose the data of Europeans stored on American soil.

The EU and U.S. struck a replacement deal in 2016, but last year the same court struck that down too—and also cast doubt on companies’ ability to use a special kind of contract to promise to adhere to EU privacy principles, something many companies rely on as a backup.

It isn’t clear what concessions or legal rights the U.S. negotiators might be willing to give Europeans in the talks next week, nor whether the offer would pass muster in what officials in both countries expect to be a third EU court challenge. Some lawyers have said resolving the issue could require changes to U.S. surveillance laws.

WhatsApp To Offer Encryption On Cloud Backups, A New Step In Privacy Arms Race

Facebook messaging unit’s protection feature is the latest development in fight over encryption technology.

Facebook Inc.’s WhatsApp on Friday said it would extend encryption on the messaging service to backups of chats shared on the platform when they are stored on Apple Inc. and Google’s cloud services.

The new offering gives WhatsApp’s two billion users additional protections for their communications, an escalation in a growing fight over encryption technology. Companies developing privacy-preserving technologies continue to be at odds with law-enforcement organizations that want access to the vast array of digital information stored on smartphones and on computer servers known as the cloud.

WhatsApp’s new feature, which the company plans to ship in a software update later this month, will let users create an encrypted backup of their chats—including images, videos and audio—and store that data on Apple’s iCloud or Google Drive.

“If you save a copy of your messages, with Apple or Google, [you] save it in a way where they have no way to read it,” said Will Cathcart, the head of WhatsApp.

This extra layer of security could keep messages and photos shared via WhatsApp private if, for example, a user’s iCloud account is compromised, said Riana Pfefferkorn, a research scholar with the Stanford Internet Observatory, an academic research group that studies internet abuse.

Right now, WhatsApp messages are encrypted between sender and receiver, meaning that even WhatsApp itself is unable to read them as they pass through its servers. But when users back up their data to the cloud, these backups are readable by the cloud providers, Ms. Pfefferkorn said.

WhatsApp isn’t turning this encrypted backup feature on by default—people who want it will need to select it in the app’s chat settings and then come up with a password that could be used to unlock the encrypted backup. The servers that will verify this password and manage the backups’ encryption keys will reside in Facebook’s U.S. and European data centers, the company said.

While Apple has fought with the U.S. Justice Department over the strong encryption system that ships with its iPhone, backups of mobile phone data on the iCloud and Google Drive have emerged as important sources of information during investigations.

WhatsApp’s new encryption system could complicate some of those searches, but the fact that it is not enabled by default will greatly reduce the number of people using it, Ms. Pfefferkorn said.

WhatsApp presents itself as a defender of online privacy in the global encryption debate, but the company experienced some backlash earlier this year when it made changes to its privacy policy reflecting the company’s future plans to offer services for business customers.

In the coming months, the company is planning to offer businesses a way of managing WhatsApp conversations with their customers. Although WhatsApp had previously said that it wouldn’t store user messages on its servers, the service for businesses would store WhatsApp messages on Facebook’s servers. Those businesses could then use that information to create Facebook ads, according to the company.

The move is seen as a key step in Facebook’s plan to generate revenue from WhatsApp, but it concerned advocates who worried that the move invaded user privacy. The controversy caused a slowdown in WhatsApp downloads during the month of January as users flocked to WhatsApp rivals Signal and Telegram, according to data from the app analytics firm SensorTower.

The announcement comes weeks after Apple delayed the rollout of new software aimed at combating child pornography on iPhones after critics said they could create broad risks for users.

Through a software update, Apple plans to implement a system that would scan phones for known images of child pornography and alert Apple if a certain number of those images were uploaded to its cloud storage service.

Apple has defended the service as privacy-friendly, but critics including WhatsApp warned it could be misused by authoritarian governments to conduct surveillance on the iPhone. Last month, Apple’s engineering chief, Craig Federighi, strongly disputed this idea, telling The Wall Street Journal that the scanning system will include “multiple levels of auditability.”

The new WhatsApp backup option would give its users a way of backing up their chat messages, including images, while opting out of Apple’s scanning system, according to WhatsApp. If images are saved elsewhere on the device, however, they wouldn’t be protected by this encryption, the company said.

But the encrypted backups are “not a perfect defense against anything a phone manufacturer might do,” Mr. Cathcart said. “The people who build the phones have a lot of power over your life.”

Updated: 9-13-2021

Discontent Simmers Over How To Police EU Privacy Rules

Delay in WhatsApp fine highlights some EU regulators’ dissatisfaction with GDPR enforcement.

The European Union’s recent $270 million fine against WhatsApp was held up for months by disagreements among national authorities, ratcheting up tensions over how to enforce the bloc’s privacy rules.

The varied approaches to policing the EU’s strict General Data Protection Regulation are fueling calls to redesign how national authorities from the 27 EU countries can intervene in each others’ cases and to explore creating a broader EU-wide regulatory system.

WhatsApp, owned by Facebook Inc., was fined for failing to tell EU residents enough about what it does with their data, including sharing their information with other Facebook units. The fine was made public in early September by Ireland’s Data Protection Commission, which had jurisdiction over the case because WhatsApp’s and Facebook’s European headquarters is in Ireland.

Eight other regulators said the Irish authority’s proposed fine of up to 50 million euros, equivalent to roughly $59 million, was too low and disagreed with the Irish regulator’s analysis of the company’s data practices.

The regulators used a GDPR resolution process to settle their disagreements, and the Irish authority said it followed the other regulators’ recommendations, including raising the fine. But regulators and privacy experts say the process of sharing enforcement among national authorities has led to bottlenecks.

“We always have the same issue. If everything relies on the lead data protection authority taking the initial step then we have the big cases taking a lot of time,” said David Martin Ruiz, senior legal officer at the European Consumer Organisation, a Brussels-based advocacy group.

If authorities from other European countries cooperate early in investigations, instead of waiting for the lead regulator’s verdict before they can intervene, decisions might be issued faster, Mr. Martin Ruiz said.

Discontent among European privacy regulators has been brewing since the GDPR took effect in 2018, with some authorities publicly criticizing their counterparts for taking too long to investigate in high-profile cases.

In May, the regional authority in Hamburg, Germany, used an emergency measure to issue a three-month ban on Facebook’s collection of data from WhatsApp users in the EU, sidestepping a provision that prevents regulators from policing companies outside their jurisdiction.

Legal procedures determining that a regulator is responsible for investigating a company based in its jurisdiction “are often not timely enough” to keep up with technology, said Pasquale Stanzione, the head of Italy’s privacy authority, and one of the eight regulators who opposed the Irish draft decision on WhatsApp.

The others were authorities representing France, Hungary, the Netherlands, Portugal and Poland; the federal German regulator; and a regional German regulator from the state of Baden-Württemberg.

A spokeswoman for WhatsApp said the company will appeal the decision.

While European authorities have channels to voice disagreement with each other’s cases, there might still be a need to re-evaluate GDPR provisions in the next few years and enable broader investigations that aren’t overseen by one regulator alone, said Ulrich Kelber, the German federal data protection commissioner.

“There’s really a need for European decisions and not just the interference of other agencies,” he said. Privacy regulators might want to replicate elements of the system that European antitrust authorities use to share investigations if they affect more than one country, Mr. Kelber said.

Alternatively, the European Data Protection Board, the umbrella group of all 27 EU privacy authorities, could have a role in such large, cross-border cases, he added.

Andrea Jelinek, chair of the European Data Protection Board, said in an email that the dispute resolution process is time- and resource-intensive, but still works well.

“It is important to bear in mind that the dispute resolution process is only employed in the exceptional circumstance where the [authorities] could not reach consensus at an earlier stage,” she said. The GDPR specifies that the process can take no longer than two months and authorities met that deadline in the two dispute-resolution cases so far, she added.

The second case involved the Irish regulator’s fine against Twitter Inc. for failing to quickly disclose a 2019 data breach. That fine was also raised after other regulators voiced objections.

The European Commission, the EU executive arm that drafted the GDPR legislation, has said it is too soon to draw conclusions about the level of fragmentation and it will explore whether to propose some “targeted amendments” to the regulation.

Helen Dixon, Ireland’s data protection commissioner, circulated a draft decision in the WhatsApp case in December, and other regulators raised objections between January and March, according to a report from the European Data Protection Board.

Ms. Dixon’s office asked WhatsApp to respond to some objections in April, and then triggered the dispute-resolution process in June to resolve the conflicts between authorities. That process finished in late July and the decision was announced this month.

Authorities are managing to work through deadlocks to reach compromise decisions, as the WhatsApp case showed, but differences in culture and mindsets between regulators will likely remain, said Eduardo Ustaran, co-head of the privacy and cybersecurity practice at law firm Hogan Lovells International LLP.

“This is always going to be an issue when you have 27 regulators trying to operate as one in a place that is as diverse as Europe,” he said.

Updated: 9-18-2021

Law Enforcement’s Use of Commercial Phone Data Stirs Surveillance Fight

Agencies’ growing use of purchased data without warrants raises new legal questions.

In January 2020, a 14-year-old girl was reported missing from her home in Missouri and classified as a runaway by local police. Her phone had been wiped of data and left behind, leaving few clues about her whereabouts.

Several hundred miles away in Fayetteville, Ark., a local prosecutor named Kevin Metcalf heard about the teenager through his professional network and suspected she might have been abducted or lured into leaving. Using widely available commercial data, he pursued that hunch in a way that is now in the sights of privacy advocates and lawmakers from both parties.

Mr. Metcalf, who runs a nonprofit that assists law enforcement in data-driven investigations, used a commercial service that provides access to location data of millions of phones drawn from mobile apps to search for devices that had been in the vicinity of the girl’s home. He identified a mysterious cellphone that appeared there about the time the teenager was believed to have left.

Through the data, Mr. Metcalf says, he saw the device had traveled from Wichita, Kan., to the Missouri teenager’s home and then back to Wichita. He could see from the patterns of the cellphone movement that the device’s owner appeared to work at a Pizza Hut in the city and live at an apartment nearby—the kind of detailed movement history that law enforcement need a warrant to access from cell towers or tech giants.

Mr. Metcalf turned the information over to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, which shared it with Kansas police. They quickly identified and arrested the device’s owner, Kyle Ellery, and an accomplice on charges related to indecency and sexual contact with a minor and recovered the girl in Kansas. Mr. Ellery pleaded guilty in federal court earlier this year and was sentenced in June by a federal judge to 87 months behind bars.

Techniques like this—often called open-source intelligence by practitioners and denounced as warrantless surveillance by critics—are the subject of a vigorous national dispute about government tracking through data brokers without a judge’s approval.

Few consumers realize how much information their phones, cars and other connected devices broadcast to commercial brokers and how widely it is used in finance, real-estate planning and advertising. While such data has been quietly used for years in intelligence, espionage and military operations, its increasing use in criminal law raises a host of potential constitutional questions.

Data brokers sprung up to help marketers and advertisers better communicate with consumers. But over the past few decades, they have created products that cater to the law-enforcement, homeland-security and national-security markets. Their troves of data on consumer addresses, purchases, and online and offline behavior have increasingly been used to screen airline passengers, find and track criminal suspects, and enforce immigration and counterterrorism laws.

The Department of Homeland Security has been using open-source phone-tracking tools for border security and immigration enforcement, while the Internal Revenue Service and FBI have evaluated such data for other kinds of criminal law enforcement, The Wall Street Journal has previously reported. Law-enforcement agencies at all levels have access to tools such as social-media monitoring, commercial-address histories and troves of license-plate data showing travel patterns.

Privacy advocates on Capitol Hill, led by Sen. Ron Wyden (D, Ore.) and Sen. Rand Paul (R., Ky.), have proposed a bill—the Fourth Amendment Is Not for Sale Act—that would curtail warrantless searches by law enforcement, including by requiring government entities to secure a court order before buying U.S. cellphone locations and other commercially available data from data brokers.

The proposed bill only applies to law enforcement—not volunteers or other nonprofit groups, which could still pursue open-source intelligence leads and turn them over to police.

Though Mr. Metcalf is a prosecutor in Arkansas, he said was acting in this case as a volunteer helping other law-enforcement agencies find a missing child. His group, the National Child Protection Task Force, also has access to facial-recognition tech tools and expertise in extracting clues from photographs and video.

Critics say allowing law enforcement to use data gathered in this way is an end run around the constitutional guarantees against unlawful warrantless searches. Other avenues exist to get information on possibly endangered children without permitting warrantless searches of consumer data, said Jennifer Granick, the surveillance and cybersecurity counsel for the Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project of the American Civil Liberties Union.

“Police and prosecutors never brag when they misuse capabilities like this; we only hear about the successes they want us to know about,” Ms. Granick said. The ACLU and a number of other privacy and civil-liberties groups have lined up in support of the proposed bill, saying law-enforcement agencies should be overseen by courts when trying to obtain information on Americans—even if it is available for purchase.

One of the main federal laws governing data privacy, the Electronic Communications Privacy Act, already contains a mechanism for tech companies to disclose data on users in emergency situations “if the provider reasonably believes than an emergency involving immediate danger of death or serious physical injury to any person justifies disclosure of the information.”

The use of warrantless tracking also raises questions about to what extent suspects need to be told about the warrantless monitoring of their devices.

No mention of the government receiving warrantless location information leading them to Mr. Ellery was made in any of the court records for either him or his accomplice. Steven Mank, an attorney for Mr. Ellery, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Though law enforcement at all levels uses location data from carriers and tech giants under judicial supervision, federal law-enforcement agencies have had an uneasy relationship with commercial data that can be purchased and searched warrantlessly.

The Department of Homeland Security has embraced commercial data for immigration enforcement purposes—using cellphone data to track unlawful immigrants and consumer data collected by utility companies and sold to brokers.

The FBI has taken a different approach. While the bureau has used the cellphone data in high-profile criminal cases in the past, people familiar with the matter say, it has treaded more carefully in domestic instances in the wake of a 2018 Supreme Court case that said similar data pulled from cell towers constituted a search and required judicial supervision.

In July, the FBI disclosed in a court filing that it was using commercial geolocation data from more than 10 data brokers as part of its wide-ranging investigation into the Jan. 6 riot at the U.S. Capitol, along with cell-tower information from the carriers and account information from tech giants such as Google.

According to a person familiar with the matter, the commercial data related to Jan. 6 was subpoenaed from the location brokers—not purchased or queried in subscription databases.

An FBI spokeswoman didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Updated: 9-29-2021

FTC Weighs New Online Privacy Rules

Agency is looking at strengthening rules that govern how digital businesses collect user data.

The Federal Trade Commission is considering strengthening online privacy protections, including for children, in an effort to bypass legislative logjams in Congress.

The rules under consideration could impose significant new obligations on businesses across the economy related to how they handle consumer data, people familiar with the matter said.

The early talks are the latest indication of the five-member commission’s more aggressive posture under its new chairwoman, Lina Khan, a Democrat who has been a vocal critic of big business, particularly large technology companies.

Congressional efforts to assist the FTC in tackling perceived online privacy problems was the focus of a Senate Commerce Committee hearing Wednesday. If the agency chooses to move forward with an initiative, any broad new rule would likely take years to implement.

In writing new privacy rules, the FTC could follow several paths, the people said: It could look to declare certain business practices unfair or deceptive, using its authority to police such conduct.

It could also tap a less-used legal authority that empowers the agency to go after what it considers unfair methods of competition, perhaps by viewing certain businesses’ data-collection practices as exclusionary.

The agency could also address privacy protections for children by updating its rules under the 1998 Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act. And it could use its enforcement powers to target individual companies, as some privacy advocates urge.

The FTC might choose not to move forward with any major privacy initiative. And action could be delayed as agency Democrats wait for confirmation of President Biden’s newest nominee to the commission, privacy advocate Alvaro Bedoya.

But since taking office June 15, Ms. Khan has made a number of moves to lay the groundwork for potential rule making, including by voting with the FTC’s two other Democrats to change internal procedures to expand her control over the rule-writing process.

Mr. Biden has ordered the FTC to look at writing competition rules in a number of areas, including “unfair data collection and surveillance practices that may damage competition, consumer autonomy, and consumer privacy.”

This week, the progressive-leaning advocacy group Accountable Tech petitioned the agency to ban “surveillance advertising” as an unfair method of competition, defining the practice as targeted advertising based on consumers’ personal data.

As an example of the harms that an alleged lack of competition among online platforms can cause, the group cited a recent Wall Street Journal article about the impact of Facebook Inc.’s Instagram app on teens’ mental health.

“The ability and incentive to extract more user data to unfairly monetize, even at the expense of children’s wellbeing, has proven too great a competitive advantage for dominant surveillance advertising firms to pass up,” the group’s petition said.

Facebook has said it faces stiff competition and that the Journal mischaracterized internal research on Instagram’s impact. It said this week that it was pausing work on a version of the photo-sharing platform designed for children under 13.

If the FTC decides to write a privacy rule, it would first have to publish a draft and seek public comment. In some circumstances, the law requires the agency to take additional, time-consuming steps such as asking for public input before even publishing a draft of a proposed rule.

Such efforts could get a boost from congressional Democrats seeking more funding for the agency.

Sen. Maria Cantwell (D., Wash.), who chairs the Commerce Committee, argued Wednesday for augmenting the FTC’s resources to better address problems of the online economy.

“The truth is that our economy has changed significantly, and the Federal Trade Commission has neither the adequate resources nor the technological expertise at the FTC to adequately protect consumers from harm,” she said in her opening statement.

Some Republicans said it wouldn’t make sense to add significant new funding to the FTC without passing new laws.

Earlier this month, House Democrats proposed giving the FTC a $1 billion budget to fund a new bureau dedicated to overseeing “unfair or deceptive acts or practices relating to privacy, data security, identity theft, data abuses, and related matters.”

That proposal will be subject to negotiations as the narrowly Democratic-led Congress looks to pass a broad new spending plan this fall. Meanwhile, several Senate Democrats wrote to Ms. Khan on Sept. 20 asking her to write rules protecting consumers’ privacy.

The lack of a broad federal law protecting consumers’ privacy has become a bigger concern for advocates as online platforms and others have amassed vast troves of consumers’ search data and other information.

Many privacy advocates are particularly worried about children, who can be more vulnerable to targeted online advertising and attention-grabbing algorithms.

Legislation to establish broad-based federal privacy protections has stalled again in Congress this year over a range of concerns. Efforts to update an existing 23-year-old federal privacy law covering younger children haven’t gained significant traction among lawmakers.

Critics say the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act and the FTC-written rules that enforce it are ineffective and out-of-date, concerns that have helped lead the agency’s newly empowered Democrats to focus more on taking further action on privacy.

“I think it’s a really, really important area for attention,” Democratic FTC Commissioner Rebecca Slaughter has said of adopting broad-based privacy rules. She said at a July congressional hearing that a potential rule could target suspected online harms to children, adding, “That is an issue that’s near and dear to my heart.”

Ms. Khan and fellow Democratic commissioners indicated at that hearing that the agency would be giving more attention to how platforms might be abusing children’s privacy, as many kids have spent more time online during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Democratic Commissioner Rohit Chopra added that the FTC should examine the underlying business models that can lead to privacy abuses.

Republican Commissioner Christine Wilson has become an advocate for federal privacy legislation, saying that consumers don’t understand how their data is collected and monetized, creating what she terms a “market failure.”

“Without this information, they cannot analyze the costs and benefits of using different products and services,” she said last week at Duke University. “And the risks to consumers from the unchecked collection of their data have intensified in recent years.”

Updated: 12-20-2022

This New App Wants To Pay You To Share Your Data For Advertising

Caden Inc. hopes to give users thousands of dollars a year under one option of its data-sharing system, with lesser payments for more limited information.

A startup backed by an internet-search pioneer wants to give cash to users who share personal data including what they buy or watch on mobile apps.

The startup, Caden Inc., operates an app by the same name that helps users download their data from apps and services—whether that’s Amazon.com Inc. or Airbnb Inc. —into a personal “vault.” Users who consent to share that data for advertising purposes can earn a cut of the revenue that the app generates from it. They also can access personal analytics based on that data.

The idea of giving consumers a cut of whatever brands might pay to reach them isn’t new, but it has been reinvigorated as outside companies have found it harder to harvest and share so-called third-party data.

The digital ad industry has been seeking new sources of the consumer data that guides online marketing efforts as traditional tracking techniques have come under pressure. A new Apple policy last year requires apps to ask permission to track users, for example, permission that many people have declined to give.

Caden, which has been testing with a limited group of users, plans to begin a public beta test of 10,000 users early next year. The company last month closed a $6 million round of funding led by seed-stage venture-capital firm Streamlined Ventures and including Yahoo co-founder Jerry Yang through his venture firm AME Cloud Ventures.

“The team is uniquely focused on trying to solve one of the dilemmas of the internet: the exchange of consumer data for ‘free access’ to services, apps, and websites,” Mr. Yang said. Consumers have typically had little or no control over how their data is collected and who it is sold to, he said.

Caden will give consumers a range of choices about sharing their data, including how it is shared and for what purpose, it said.

One option in the public beta test will anonymize and pool the data before sharing it with outside parties in exchange for $5 to $20 a month, according to Caden founder and Chief Executive John Roa.

The amount of compensation will be determined by a “data score” reflecting factors such as whether consumers answer demographic survey questions and which apps and services’ data consumers are sharing.

Consumers will eventually be given the option to share more specific information for more tailored advertising. A marketer could then form audience segments and tailor their ad targeting and messaging to those groups.

For instance, a user could consent to sharing his ride-share history so advertisers could create segments of people who ride a certain amount. That would eventually pay consumers up to $50 a month, Caden said.

A third option would let advertisers take a direct action based on the data that Caden understands about a specific user. If a consumer were part of a department store’s loyalty program, for example, the store might reward her for sharing her individual Amazon shopping history and use it to provide more personalized offers. That could generate thousands of dollars a year for participating users, the company said.

Caden also hopes that the data it can aggregate will be compelling for consumers. Users could search for restaurants they’ve eaten at in a certain city, for instance, or how much they spent in certain categories across different apps, executives said.

“It’s like Spotify Wrapped for your whole life,” said Amarachi Miller, Caden’s head of product, referring to the streaming music service’s year-end distillation of each user’s listening.

Mr. Miller said two early groups that have shown interest in the app have included tech early adopters and couponers, a group of consumers that are savvy about rebates and deals, who hope to use the app as a passive income tool.

But any app that’s successful in the space will need to win over all sorts of consumers and keep them coming back in order to give marketers a compelling amount of data, said Ullas Naik, founder and general partner at Streamlined Ventures, the lead on the new funding round.

“The consumer app is going to have to be incredible. Not only the user experience, but also the value that the consumer gets is going to have to be amazing,” Mr. Naik said. He said his firm has looked at many companies attempting this in the past, but believes Caden is furthest along in putting it all together.

Caden is trying to crack into a nascent business with plenty of competitors, said Forrester Research Inc. analyst Stephanie Liu. Other companies in the space include CitizenMe Ltd., which lets consumers gather their own data and exchange it for money or rewards, according to its website.

Success will require not only wide adoption by consumers and advertisers but also trust from consumers, Ms. Liu said. She said if consumers’ data is used in ways they don’t expect, they could be turned off and abandon such platforms.

She said companies must do what they can to retain consumer trust and ensure advertisers don’t breach that trust.

Caden said it will initially sell only anonymized and aggregated data that doesn’t tie back to individuals. As it starts to let brands do more personal promotions for users, it said it will let users see which brands and partners it’s working with, and will let users control which brands can access their information.

For instance, a consumer would be able to see that they’re represented as someone who streamed a horror film in the past 30 days. They’d also be able to limit or restrict advertisers by a category or by name.

Caden’s plan to let consumers choose which brands they share with, and what kinds of information brands get, could be a differentiator, according to Ms. Liu. Some other players that offer compensation for data have required consumers share their entire profile with all brands.

But Ms. Liu also said she believes the space isn’t likely to see mainstream success until another privacy shift—Google’s plan to stop supporting third-party tracking in its Chrome browser—takes effect no sooner than 2024.

Brands for now can still collect much of the information about consumers that these services are asking users to consent to share on their own, she said.

“I think these will be a series of niche solutions, something advertisers can experiment with and something consumers can experiment with, but I don’t see them taking off,” she said.

Updated: 3-30-2023

California’s New Data Privacy Law On Customer Data Takes Effect

SACRAMENTO, Calif., (BUSINESS WIRE) –– The California Privacy Protection Agency (CPPA) marked a historic milestone by finalizing their first substantive rulemaking package to further implement the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), which was approved by the California Office of Administrative Law (OAL). The approved regulations are effective immediately.

“This is a major accomplishment, and a significant step forward for Californians’ consumer privacy. I’m deeply grateful to the Agency Board and staff for their tireless work on the regulations, and to the public for their robust engagement in the rulemaking process,” said Jennifer Urban, Chairperson of the California Privacy Protection Agency Board.