Short Sellers Bet On Opioid Fallout Sinking Drug Companies’ Stocks (#GotBitcoin?)

Hedge funds target drugmakers in expectation of financial pressures from potential settlements. Short Sellers Bet On Opioid Fallout Sinking Drug Companies’ Stocks (#GotBitcoin?)

At an investor lunch in late March, the chief executive of drugmaker Mallinckrodt PLC, one of the largest generic oxycodone producers in the U.S., said he expected the company would bear no liability for its alleged role in the opioid crisis, according to people familiar with the meeting.

Some Investors Are Betting Otherwise

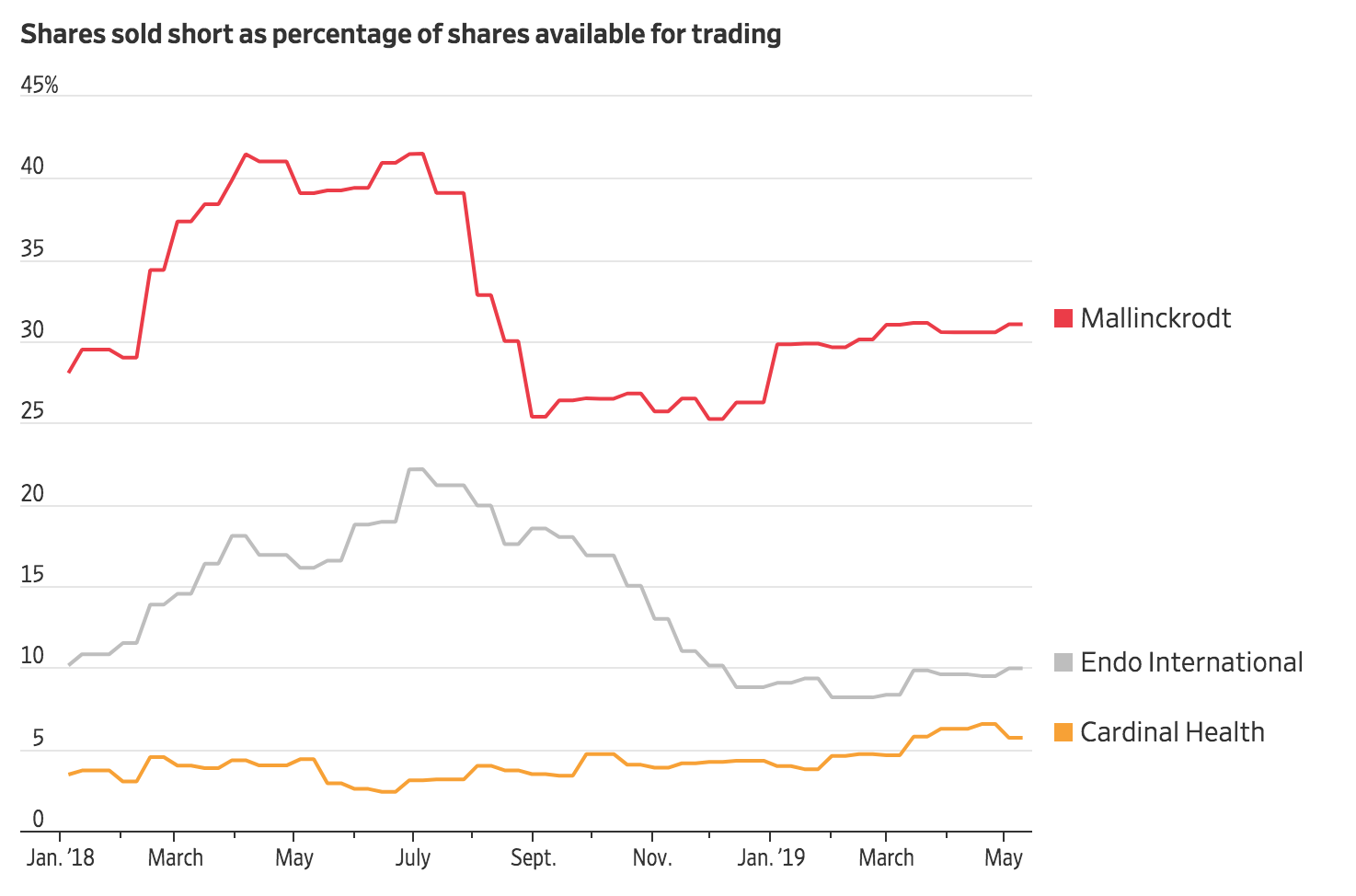

Around 2,000 lawsuits have been brought by municipalities and other plaintiffs accusing companies in the pharmaceutical supply chain, including Mallinckrodt, of fueling the opioid epidemic. “Wall Street is underestimating the impact on companies from the opioid litigation,” said Justin Simon of health-care hedge fund Jasper Capital Management LP in Chevy Chase, Md., who has been betting against Mallinckrodt and some other companies named in the lawsuits.

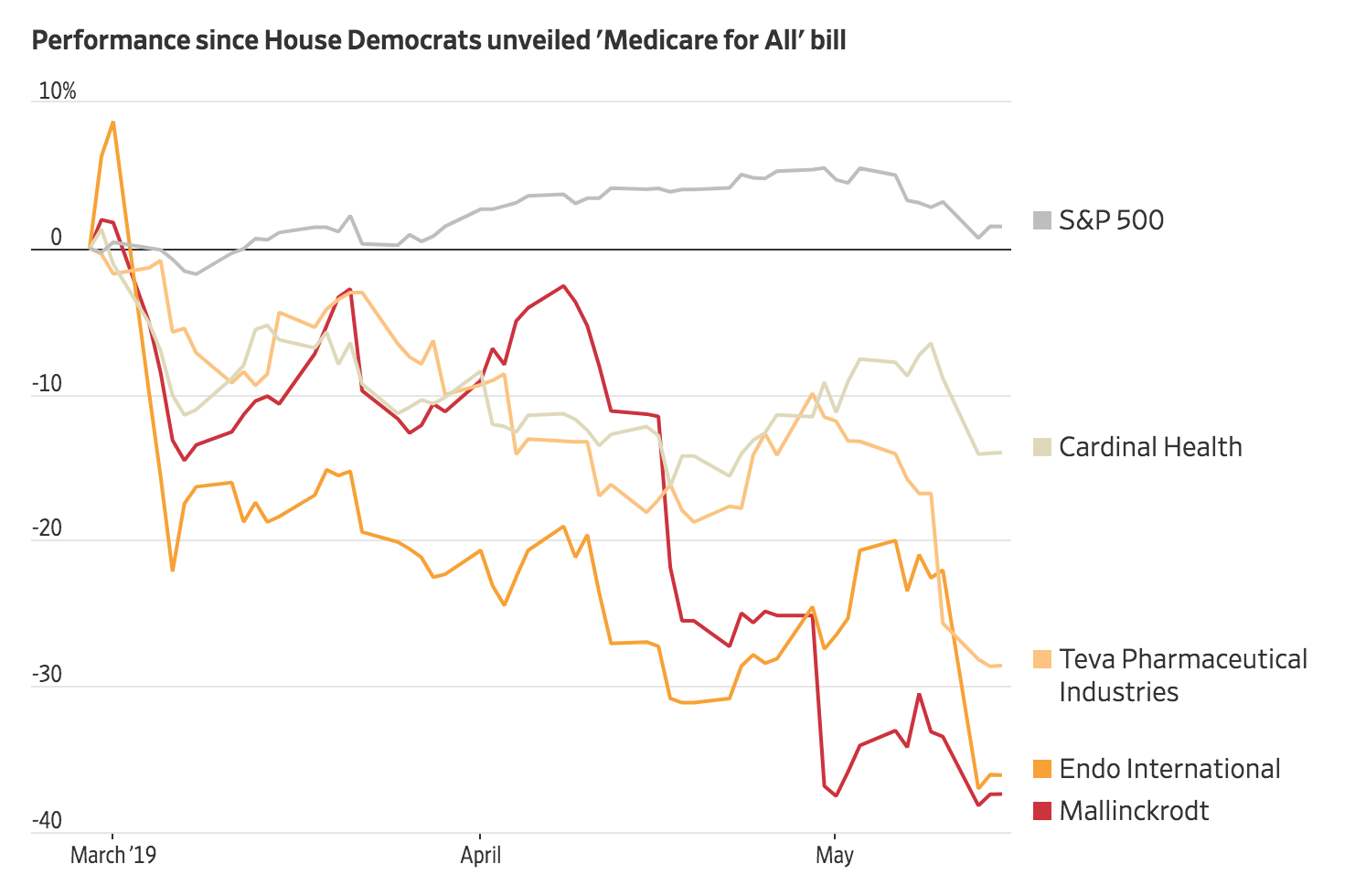

Drugmakers including Mallinckrodt, Allergan PLC, Endo International Inc., Johnson & Johnson and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., along with several drug distributors, have been named as defendants in the lawsuits and are the subject of hedge funds’ wagers that the companies will face costly settlements.

The companies named in the suits have been fighting the litigation and denied liability for the opioid crisis. Nearly 400,000 Americans have died from opioid overdoses from 1999 to 2017, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with the rate of deaths picking up over time. A Mallinckrodt spokesman said the company would vigorously defend itself against the claims and that “at this point, there is no settlement that is probable and estimable.” He also said Mallinckrodt expects any such settlement to be manageable.

Short sellers won big this week when shares of Insys Therapeutics Inc. fell 74% on Monday after the company said it might have to file for bankruptcy partly because of costs and liabilities related to opioid lawsuits. In a short sale, investors sell borrowed shares in hopes they can buy them back at a lower price, return the stock and pocket the difference.

Earlier this month, Insys Therapeutics co-founder John Kapoor was among five executives of the company, which sold a fentanyl spray for treating cancer-related pain, who were convicted of engaging in a racketeering conspiracy to boost prescription opioid sales. Insys has said actions taken by “a select few former employees” don’t represent the company’s current work.

The opioid litigation is just one of many problems facing the health-care industry, which is the worst-performing sector in the S&P 500 this year. Those issues include public resistance to drug-price increases, the possibility of universal health-care legislation, lawsuits alleging that pharmaceutical companies colluded to raise generic drug prices and the Trump administration’s proposed overhaul of drug rebates.

Investors such as James Chanos and BR Dialectic Capital Management LLC have placed bets on or against Mallinckrodt or other companies up and down what traders call the “pain chain,” betting that in addition to other factors affecting the sector, the companies would have to make payments for their alleged roles in the opioid crisis.

Plaintiffs broadly allege manufacturers misrepresented the addictive risks of their drugs and aggressively marketed them to doctors. Distributors, meanwhile, are accused of failing to flag suspicious orders and flooding communities with pills.

It isn’t clear whether the plaintiffs will win their lawsuits or see windfalls.

While the claims related to the crisis have been compared with landmark cases brought against tobacco companies in the 1990s, they are far more complex in both the number of plaintiffs and defendants involved and in the separate tracks—federal and state—involved. Complex-litigation experts said they accordingly expect it to be more difficult for any global settlement to be reached.

Defendants argue opioid deaths can also be blamed on doctors who write inappropriate prescriptions and on illegal opioids like heroin. In court filings, drugmakers and distributors point to the roles of the Food and Drug Administration and the Drug Enforcement Administration in approving opioids and overseeing their distribution.

Some investors see the risks as manageable. The Baupost Group, run by well-known value investor Seth Klarman, has been invested in distributors that have been named in opioid-related suits, including AmerisourceBergen Corp. , Cardinal Health Inc. and McKesson Corp. Baupost views their shares in part as inexpensive but is following the litigation closely, said people familiar with the matter. The distributors deny liability and have been fighting the claims.

One company that sells opioids, OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma LP, can’t be shorted because it is privately held by the Sackler family. The lawsuits allege Purdue played a central role in addicting the nation to opioids.

A spokesman for Purdue, which has denied the allegations, said it is working to reduce opioid addiction and is focused on expanding beyond opioids.

Purdue has said it could file for bankruptcy as it seeks to contain liability from the mounting cases. Shares of drugmakers and distributors fell in early March after news reports about the possible bankruptcy.

Mallinckrodt’s business consists largely of generic opioids—a unit that the company has said it plans to spin out—and its H.P. Acthar Gel drug used to treat infantile spasms and other conditions. Short sellers have targeted Mallinckrodt since before the opioid litigation gained momentum, and Mr. Chanos has been focused on Acthar, which was cited in the Medicare trustees’ annual report as an example of wasteful spending last year. A vial of the drug costs nearly $39,000.

Mallinckrodt and Teva have said that, unlike makers of branded opioid products, they don’t promote opioids.

Some hedge funds have been watching for distress in the sector, citing certain companies’ use of leverage or declining profitability.

Share Your Thoughts

Do you think investors will win their bets against companies under pressure for their alleged roles in the opioid crisis? Why or why not? Join the conversation below.

Investors said Teva could be hurt by any potential opioid settlement because of its weak balance sheet. On Teva’s most recent earnings call, Chief Executive Kåre Schultz said, “As you know, we have a lot of debt, so we don’t have that much money. So I think [opioid plaintiffs will] have to find somebody else if they want big settlements. It won’t be with us.”

Some traders said betting against behemoths like Johnson & Johnson, which could easily pay settlements, has its risks. J&J shares could rally even after a large settlement because of decreased uncertainty, one said. A J&J spokesman declined to comment on the opioid suits. A Teva spokesman said the company “hasn’t engaged in any conduct that would lead to civil or criminal liability” and that Teva would “continue to vigorously defend” itself.

So far, the highest-profile opioid settlement was reached in Oklahoma, where Purdue agreed in March to a $270 million payment. Hedge funds now are focused on Oklahoma’s claims against J&J and Teva, which are set for trial in late May.

In an interview, Mr. Schultz declined to say whether the company was planning to settle any opioid litigation. But he signaled a possible defense by Teva: “We played by the rules.”

Related Articles:

What Do You Get When Legal Drug Dealers Peddle “Heroin-in-a-Pill” To It’s “Clientele”?

Freedom of Information Act Document Reveals Antidepressant Drugs Are Less Effective Than Placebos

Fentanyl’s New Foe: A Quick Test Strip That Can Prevent Overdoses (#GotBitcoin?)

Pharmaceuticals Found In Our Drinking Water!

Opiate-Addicted Babies Are The New Crack Babies of 2019

A Billionaire Pledges To Fight High Drug Prices, And The Industry Is Rattled (#GotBitcoin?)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.