A Billionaire Pledges To Fight High Drug Prices, And The Industry Is Rattled (#GotBitcoin?)

Ex-energy trader John Arnold has put $100 million behind efforts to curb prices. A Billionaire Pledges To Fight High Drug Prices, And The Industry Is Rattled

Billionaire John D. Arnold is spending a chunk of his fortune to campaign against America’s high drug prices. The drug industry is spending a chunk of its fortune to counter him.

Mr. Arnold is the biggest single spender on his side of the battle. He made his money placing bets on price swings in the natural-gas market, first as an energy trader at Enron, then at his own hedge fund after Enron’s collapse.

Now retired, the 44-year-old Texan with an estimated $3.3 billion in assets is dedicating himself to the topic of the U.S.’s ballooning health care costs.

He has spent more than $100 million in health-care-related grants since 2014. A million dollars went to Civica Rx, a nonprofit formed by seven U.S. hospital systems to make generic drugs. Up to $5.7 million is pledged to Initiative for Medicines, Access & Knowledge Inc., which files legal challenges to the validity of certain U.S. drug patents, to clear the way for lower-cost generics.

He funded research about the relationship between pharmaceutical packaging and drug costs, leading Medicare to pass new rules that took effect in 2017. The state of California, advised by an Arnold-funded group, passed a law in 2017 requiring drugmakers to justify steep price increases.

“Everybody thinks that the pharma industry is abusive in their tactics and doesn’t price drugs fairly,” he said in an interview in his Houston office.

For drugmakers, Mr. Arnold is a new and powerful opponent—and somewhat of a mystery. His profile as a critic has sharpened in the past year through his funding of a political action group active in the midterm elections, on behalf of candidates from both parties. Few pharmaceutical executives have ever had personal contact with him.

Several said that based on Mr. Arnold’s funding and choice of projects they are wary of his influence, and take issue with his findings and approach.

“My complaint with them is they seem to be positioning it as, ‘We’re pointing fingers at drugs companies, and we’re going to do everything possible to make them look bad without having a balanced view,’ ” said Ron Cohen, chief executive of drugmaker Acorda Therapeutics Inc.

In a tweet last month criticizing Mr. Arnold’s comments about “broken pharma pricing,” Dr. Cohen said pricing is “far more complicated, with far more competing interests, than your outlook acknowledges.”

Unlike in the energy market, where many buyers and sellers create market competition and monopolies face government regulations, Mr. Arnold contends there are no meaningful checks on the drug industry’s power to set prices. Health spending “is large and growing, and the trend line is going in the wrong direction in terms of financial sustainability,” he said.

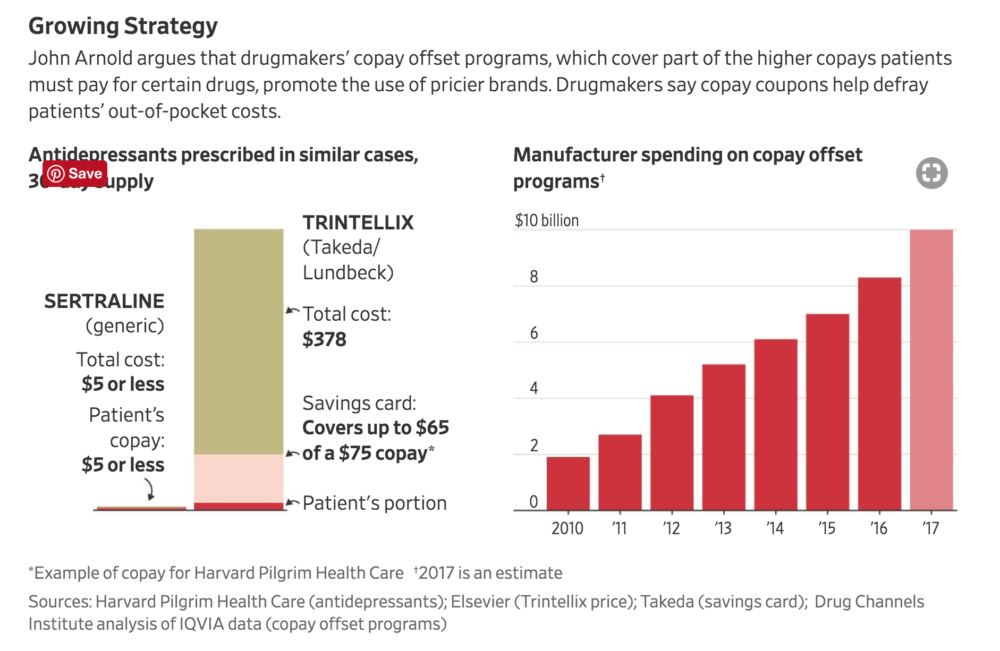

Growing Strategy

The pharmaceutical industry says a free hand on pricing helps fund risky research and development in the hunt for new and better drugs, and that prices reflect the benefit that drugs provide to many patients. Drugmakers also say middlemen in the industry’s supply chain contribute to higher prices by taking cuts of the list price.

The foundation set up by the trader and his wife, Laura, a former corporate attorney, has assets of $2.2 billion—that’s more than the American Red Cross, which had net assets of about $1.2 billion in 2017—and more than 70 staffers working in offices in Houston, New York and Washington. It also funds causes related to criminal justice, education and public-employee pension systems.

John Arnold argues that drugmakers’ copay offset programs, which cover part of the higher copays patients must pay for certain drugs, promote the use of pricier brands. Drugmakers say copay coupons help defray patients’ out-of-pocket costs.

Mr. Arnold has given $19 million to Boston-based Institute for Clinical and Economic Review to evaluate whether the prices of various drugs reflect their health benefits. ICER often concludes they don’t; for example, it says that some opioid pain drugs marketed as having “abuse-deterrent” formulations, such as capsules resistant to crushing into powder that can be snorted, aren’t cost-effective.

Last year the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs’ pharmacy-benefit program began incorporating ICER’s reports into its price negotiations with the industry. Some insurers are using the data in their contracts, and CVS Corp.’s pharmacy-benefit management division said in August it would give its clients—health insurers and employers—the option not to pay for certain drugs if their prices exceed ICER’s cost-effectiveness threshold.

Drugmakers have funded groups to counter ICER, including Patients Rising. The group, which has received $435,000 in the past 12 months from drug companies including Amgen Inc. and Celgene Corp. , said ICER uses flawed methodology and its reports are causing insurers to restrict patients’ access to drugs because of their price.

ICER is promoting the idea “that some patients are too costly to treat and too expensive to save,” said Terry Wilcox, executive director and co-founder of Patients Rising.

Spokespeople for Amgen and Celgene said they support organizations that work to ensure patients’ access to treatments.

Steven Pearson, head of ICER, said patients deserve access to the medicines they need, and ICER’s methods help reveal what fair prices would be for those medicines, not whether some patients are too costly to treat.

Industry lobbying group Biotechnology Innovation Organization has raised alarm about “an increasingly coordinated effort” by Mr. Arnold to focus on prices. It handed out a paper at a meeting of executives from its member companies in May titled “The Arnold Foundation’s $49 million Web of Influence,” listing groups that received funding for drug-price projects.

While project-funding details are available on the Arnold website, BIO spokesman Brian Newell said the page was distributed “to understand where the money was coming from and how many of these efforts are coordinated through a single entity.”

He said the Arnold foundation is “putting tens of millions of dollars behind a network of activists in order to shape how the media reports on the biotech industry, influence which medicines patients have access to and undermine the intellectual property rights of innovators.”

Mr. Arnold said the foundation also funds academic researchers, and it doesn’t direct the content of news coverage it helps fund, including Kaiser Health News, to which it provided about $1.2 million for coverage of drug development and pricing. Mr. Arnold said the ideas generated by foundation-funded researchers wouldn’t undermine intellectual property and would inject competition into the marketplace.

For Mr. Arnold, personal or emotional reasons aren’t driving his fight against high prices—making him a confounding opponent, drugmakers said. Instead, it is the intellectual challenge of tackling a seemingly intractable problem.

He said he became interested in drug pricing after hearing about steep price increases and high starting prices for new drugs, such as Gilead Sciences Inc.’s hepatitis C treatment Sovaldi, which went on sale in late 2013 at a list price of $1,000 per pill. Mr. Arnold called the price arbitrary.

“That made it clear normal market tensions didn’t exist in this market and existing regulation was deeply flawed,” he said. Gilead declined to comment.

Buyers and sellers in the health-care industry are vastly unequal, he said. For brand-name, patented drugs, companies can charge what they wish because no competing generics can enter the market.

“In any other industry where you have some type of monopoly, where the good that’s being sold is viewed as a necessity and there aren’t close substitutes, there has to be a strong regulatory environment on how to ensure access, and ensure affordability,” he said.

People in the drug industry counter that monopolies afforded by patents allow companies to recoup the sizeable cost of R&D before a drug goes generic, and that health insurers and pharmacy-benefit managers act as a check on pricing.

Another reason Mr. Arnold got involved: Drug pricing was an issue no other philanthropist had claimed.

What Is a Fair Price?

As a hedge-fund manager, Mr. Arnold had a reputation for keeping a cool head in volatile trading, confident in his bets because he carefully studied wonkish data such as weather trends, according to Bill Perkins, who worked for Mr. Arnold and now has his own trading firm in Houston. Mr. Arnold closed his hedge fund in 2012.

Mr. Arnold said he draws graphs in his head to identify parts of the market with the most egregious pricing. He said he imagines a 3-D grid with different factors he believes affect pricing.

“John loves solving puzzles,” said Mr. Perkins, the former trading colleague. “This is a big giant hairy puzzle. It’s easy for me to see John in the weeds” on the issue.

At the foundation, the Arnolds work in adjacent offices with their contemporary art collection scattered around the building.

Employees say Mr. Arnold is sometimes at the office before anyone else arrives, and can often be spotted reading in an office library stocked with titles including “Unhealthy Politics: The Battle Over Evidence-Based Medicine.”

He could never be called effusive. “They’re not the backslapping kind,” ICER’s Dr. Pearson said of the Arnolds.

Priti Krishtel, co-executive director of the Initiative for Medicines, Access & Knowledge, said meeting with the Arnolds was like “sitting with patent lawyers from a law firm.”

The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review evaluates the pricing of new drugs by applying the concept of the value of a quality-adjusted life-year, or an additional year of healthy life after receiving a treatment.

A $2.2 million grant went to cancer specialist Dr. Vinay Prasad to study health-care practices that turn out to be ineffective. Last year, Dr. Prasad co-wrote research contending it costs less than drug companies say to bring a cancer drug to market.

He asked questions “like he could be a reporter,” Dr. Prasad said of Mr. Arnold. “He pushed me on a lot of my thoughts: ‘Aren’t there some advantages to some of these things? Things you’re not thinking about?’”

The industry said Dr. Prasad’s report ignored necessary spending on drugs that don’t make it to market.

Jim Greenwood, president and CEO of BIO, said in a blog post responding to the report that a majority of experimental cancer drugs that enter clinical trials end up failing. He said there should be “compensating upside” for the few drugs that do make it to market to ensure investors continue to fund companies’ uncertain R&D efforts.

At an Arnold foundation board meeting in March, David Mitchell described how his group, the Arnold-funded Patients for Affordable Drugs, brings patients to Washington to meet with members of Congress and administration officials, and trains them to use personal stories in meetings, appearances and letters.

On a screen at one end of the conference room, Mr. Mitchell played for the Arnolds a CBS News interview with a patient his group has coached. Taking notes on a white pad, Mr. Arnold homed in on key points to press with lawmakers.

Near the end of the hourlong meeting, Kelli Rhee, the foundation’s president and CEO, made a pitch to Mr. Mitchell to moderate his public discourse.

“Some of the language around pharma is becoming more entrenched and dug in, and I wonder if there are opportunities for you guys to think about where there can be constructive dialogue,” she said.

Mr. Mitchell said it was too soon to be conciliatory. “More than 80% of Americans believe we should be doing something to lower drug prices,” he responded. “We are angry about it, and we have hot rhetoric.”

Go back

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.