Fed Makes It Easier For Banks To Pass Stress Tests (#GotBitcoin)

The Fed recently made it easier for banks to pass the stress tests, easing a “qualitative” component of the exam that evaluates banks on factors such as the quality of its internal data and management controls. Fed Makes It Easier For Banks To Pass Stress Tests (#GotBitcoin)

Related:

Fed To Further Overhaul Stress-Testing Regime, Making It Easier For Banks To Pass

Annual January 3rd “Proof of Keys” Celebration of The Genesis Block!

Bitcoin Is World’s Best Performing Asset Class Over Past 10 Years

What Are Lightning Wallets Doing To Help Onboard New Users? (#GotBitcoin)

Ultimate Resource For Your Crypto Hardware (And Other) Wallets

Ultimate Resource On Trezor Hardware Wallets (#GotBitcoin)

Ultimate Resource On Ledger Hardware Wallet (#GotBitcoin)

Next Bitcoin Core Release To Finally Connect Hardware Wallets To Full Nodes (#GotBitcoin)

Apple Announces CryptoKit, Achieve A Level of Security Similar To Hardware Wallets (#GotBitcoin)

Introducing BTCPay Vault – Use Any Hardware Wallet With BTCPay And Its Full Node (#GotBitcoin)

Bitcoin Dev Reveals Multisig UI Teaser For Hardware Wallets, Full Nodes (#GotBitcoin)

The Fed is also considering changes that would eliminate the chance banks could fail the second part of the test—which evaluates whether the banks would have enough capital under a hypothetical shock to remain above all regulatory capital requirements—in favor of a continuous capital requirement.

Those changes have sparked concerns from some Democrats, who say the Fed is making the exercise too easy for banks. For the second time ever this year, no firm failed the stress tests.

Annual exam must explore unexpected scenarios or it might fail to prepare financial system for next downturn.

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell said stress tests of the nation’s largest banks must adapt and keep firms on their toes, or the annual exam could fail to prepare the financial system for the next downturn.

“If the stress tests do not evolve, they risk becoming a compliance exercise, breeding complacency from both supervisors and banks,” Mr. Powell said Tuesday in prepared remarks for a stress-testing conference at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

“When the next episode of financial instability presents itself, it may do so in a messy and unexpected way,” Mr. Powell added. “Banks will need to be ready not just for expected risks, but for unexpected ones.”

The tests must vary from year to year and explore “even quite unlikely scenarios,” Mr. Powell said, warning that too rote an exam could encourage banks to have similar portfolios, making the system more vulnerable to specific risks.

“All banks would look much alike rather than the banking system we want and need, one with diverse institutions with different business models,” he said.

Updated: 11-26-2019

U.S. Banks Cram For Fed Risk Test, With Ripple Effects In Repo

New quarterly data from the biggest U.S. banks suggest that some will need to back away from short-term lending markets by year-end to avoid triggering requirements that they hold more capital.

The data, posted on Friday by the Federal Reserve, showed four of the six biggest U.S. lenders were above or close to thresholds that would increase their capital surcharges.

An easy way to get the scores down would be doing less lending through overnight repurchase agreements and foreign exchange swaps, said analysts who track the filings.

Those markets have experienced stress in recent months. Retreats by lenders would make them more vulnerable.

“If the economic narrative shifts in December, it could have a greater impact than if it were to shift at any other point in the year,” said Josh Younger, a derivatives strategist at JPMorgan who is not involved in the bank’s lending.

Calculations from September data in the JPMorgan Chase & Co (JPM.N) filing, for example, indicate that its score as a Global Systemically Important Bank, or GSIB, was 751, or 21 points above the level at which its capital surcharge would be increased to 4% from 3.5%.

If JPMorgan doesn’t get below 730 it will have to hold another $8 billion of capital, analysts estimated. That would dampen return on equity. The bank has said it will be under the threshold.

The Fed, similar to bank regulators abroad, began imposing GSIB surcharges in 2016. The aim was to make big banks bear the costs to others of their failure and force them to choose whether to shrink or hold more capital.

Goldman Sachs Group Inc (GS.N) needs to take at least 16 points from its score to avoid a higher surcharge and Bank of America Corp (BAC.N) needs to shave eight points. Citigroup Inc (C.N) is two points under a markup, but could seek a wider margin because higher fourth-quarter stock prices are poised to add to all scores.

Backing away from certain short-term lending instruments, particularly swaps and other derivatives, is one of the easiest temporary ways to reduce scores, which are compiled from dozens of measurements and calculations.

Borrowers in the $3.2 trillion-a-day FX swap market are nervously looking toward year-end and having to decide between paying up or exiting positions.

The Federal Reserve has been stabilizing the repo market since mid-September when rates spiked to as much as 10% from about 2%.

Updated: 12-17-2019

Regulators Find Shortcomings In Resolution Plans At Six Large U.S. Banks

The banks must address the shortcomings by the end of March.

Regulators on Tuesday said they had found “shortcomings” in the resolution plans at six of the largest U.S. banks, while none of the eight major banks they examined had more serious “deficiencies.”

The Federal Reserve and Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. said the firms, including Bank of America Corp. , Citigroup Inc. and Wells Fargo & Co. had shortcomings related to their ability to reliably produce data needed to execute orderly wind-downs, also known as living wills, “in stressed conditions.”

The six banks, which also include Bank of New York Mellon Corp. , Morgan Stanley and State Street Corp. , must address the shortcomings by the end of March. They next submit living wills in 2021.

Tuesday’s moves, the regulatory equivalent of a slap on the wrist, are less severe than the finding of a “deficiency,” which could lead to more stringent capital and liquidity requirements for the firms.

The agencies didn’t find shortcomings in the plans from Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and JPMorgan Chase & Co.

Fed officials have grown increasingly confident that big U.S. banks are safer than they were in 2008, when the financial crisis exposed significant weaknesses in their risk management.

Tuesday’s findings are a turnabout from just three years ago, when the Fed ordered five big U.S. banks to make significant revisions to their plans, citing deficiencies.

“The largest banks have been making steady progress, and the regulators are in greater agreement on what progress is than in prior rounds,” said Karen Petrou, managing partner of Federal Financial Analytics, a regulatory advisory firm.

Wells Fargo said it was pleased the Fed found no deficiencies with its plan.

A Bank of New York spokeswoman said the lender “will work diligently to address the specific areas of feedback identified by the regulators in the required time frame.”

Spokesmen for Bank of America, Citi and JPMorgan declined to comment. The other banks didn’t immediately respond to requests for comment.

Kevin Fromer, president and chief executive of the Financial Services Forum, which represents the largest U.S. lenders, said the results show the firms “are strong, resilient and resolvable.”

Under the 2010 Dodd-Frank law, big banks must file plans showing they have a credible strategy to go through bankruptcy without causing a broader economic panic, one of many provisions in the law designed to prevent a repeat of financial-crisis bailouts.

Updated: 2-6-2020

Risky Corporate Debt To Take Center Stage In 2020 Stress Tests

The Federal Reserve will test the strength of the largest U.S. banks by subjecting them to a hypothetical recession.

The Federal Reserve will test the strength of the largest U.S. banks by subjecting them to a hypothetical recession in which credit markets seize up and private-equity investments take a hit.

The annual stress tests, in which 34 large banks must show how they would survive dramatic market and economic shocks, will feature a situation in which a severe global recession leads to “widespread defaults” on corporate loans, the Fed said Thursday.

In the worst-case scenario, which the Fed terms “severely adverse,” a broad selloff in corporate bonds and leveraged loans hits an array of risky credit instruments and private-equity investments, sending shocks through a variety of markets. The biggest banks in America—a group that includes JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Goldman Sachs Group Inc.—must pass the tests to return money to shareholders.

Leveraged loans are typically extended by banks to low-rated corporate borrowers. Many get packaged into structured products called collateralized loan obligations. Both have been among the hottest investments in recent years, raising concerns about how they would fare in a recession.

“This year’s stress test will help us evaluate how large banks perform during a severe recession, and give us increased information on how leveraged loans and collateralized loan obligations may respond to a recession,” said Randal K. Quarles, the Fed’s vice chairman for supervision.

The stress tests reflect the brisk growth in corporate debt in recent years. U.S. nonfinancial corporate debt has risen to nearly 47% of gross domestic product, a record high, according to the Fed and the Commerce Department.

The other pieces of the severely adverse scenario remained largely the same as last year, including a rise in the unemployment rate to 10%. It was at 3.5% in December, down from 3.9% a year earlier. The scenario also assumes a drop in real gross domestic product and falling inflation, as well as plunging stock prices and home values.

Updated: 4-4-2020

Fed Unlikely To Order Big U.S. Banks To Suspend Dividends

U.S. central bank isn’t seen following European counterparts in pressuring banks to halt dividends.

U.S. banks will likely be allowed to keep paying dividends to shareholders, according to people familiar with the matter, even as the coronavirus pandemic threatens to create a mountain of bad loans that could eventually weaken the lenders.

Some former U.S. regulators have said the Federal Reserve should order the largest banks to suspend payouts to preserve capital at a time of soaring unemployment and business disruption that may eclipse the 2008 financial crisis.

“If things work out well, banks can distribute income later on,” said Janet Yellen, a former Fed chairwoman. “If not, they’ll have a buffer that will be needed to support the credit needs of the economy.”

The European Central Bank and the Bank of England over the past week pressured banks to stop using their capital to make dividend payments to shareholders, raising questions about whether the Fed would follow suit in the U.S.

But Fed officials are unlikely to do so, at least in the short term. They see key differences in how lenders distribute capital on the two continents, and they plan to conduct a more deliberate analysis of the U.S. banking system’s health, the people said.

Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester said she prefers to await the results of the next set of the banks’ “stress tests” in June before deciding whether to limit dividend payments. The tests are used to assess banks’ ability to continue lending in a crisis.

Updated: 6-25-2020

Fed Stress Test Finds U.S. Banks Not Healthy Enough To Withstand A Prolonged Economic Downturn

In its annual stress test, the Fed said the nation’s biggest banks are healthy but could suffer 2008-style losses if the economy languishes.

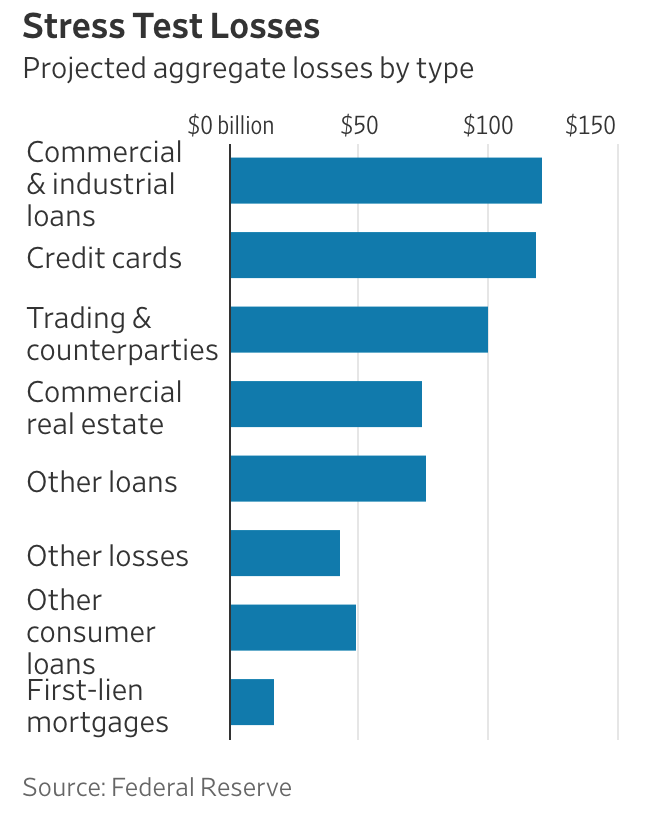

The Federal Reserve on Thursday said a prolonged economic downturn could saddle the nation’s biggest banks with up to $700 billion in losses on soured loans and ordered them to cap dividends and suspend share buybacks to conserve funds.

In a worst-case scenario, where unemployment remains high and the economy doesn’t bounce back for a few quarters, the 33 largest U.S. banks would suffer heavy loan losses that would erode the capital buffers meant to keep them on stable financial footing, the Fed said when it announced the results of its annual stress tests.

Designed to gauge the health of the nation’s banking system, the stress tests were expanded this year to study the effect of the downturn brought on by the coronavirus pandemic. The Fed said U.S. banks are strong enough to withstand the crisis and restricted dividend payouts and buybacks to make sure they stay that way.

Banks, which will announce their dividend plans for next quarter as soon as Monday, won’t be able to make payouts that are greater than their average quarterly profit from the four most recent quarters.

The Fed also barred them from buying back shares in the third quarter. Most of the largest banks had previously agreed to halt buybacks during the second quarter. Buybacks are the main way U.S. banks return capital to shareholders.

In a sign of the uncertainty facing the industry, the Fed required banks to resubmit updated capital plans later this year to reflect current stresses.

The central bank didn’t break out the results of the coronavirus analyses for individual banks. However, among the six largest, only Wells Fargo & Co. had a dividend payout that would breach the new threshold set by the Fed, according to Wolfe Research forecasts. The bank’s dividend in the third quarter would be 150% of its average expected profits over the past four quarters. A Wells Fargo spokesman declined to comment on the stress test results.

The Fed said limiting shareholder payouts would help keep banks healthy during the recession. Its analysis of the current pandemic found that if the economy takes a long time to recover, banks could experience losses similar to the financial crisis of 2008.

Banks could suffer losses on consumer debt such as auto loans and mortgages, as well as corporate debt and commercial real estate. Most of the firms would remain well capitalized, but some would approach their minimum capital levels.

Randal Quarles, the Fed’s point man on financial regulation, said the central bank could take additional steps to restrict buybacks or dividends “if the circumstances warrant.”

The Fed’s decision to allow banks to keep paying dividends during the crisis drew a sharp dissent from Lael Brainard, the Fed’s lone holdover from the Democratic Obama administration. Allowing banks to “deplete capital buffers,” she said, could force them to tighten credit in a protracted downturn.

“This is a time for large banks to preserve capital, so they can be a source of strength in a robust recovery,” she said in a statement. “This policy fails to learn a key lesson of the financial crisis, and I cannot support it.”

Former Fed officials and Democratic lawmakers have urged the central bank to prohibit both buybacks and dividends to ensure the firms could continue to lend if the economic fallout from the pandemic worsens.

Daniel Tarullo, who oversaw bank regulation at the Fed from 2009 until 2017, said Thursday’s moves “don’t really amount to much” and reflect a “substantial erosion” in the value of the annual tests. The Fed ought to have taken the time to recalibrate this year’s tests to reflect the actual coronavirus shock, rather than adding analysis that “apparently was not good enough to release on a bank-by-bank basis to the public,” but is nonetheless being used to inform bank capital policies during the third quarter.

The Fed annually releases a scenario for an economic catastrophe and then looks at banks’ ability to withstand it.

The results, which were broken out by individual banks and released Thursday, were largely as expected. But this year’s scenario was quickly overshadowed by the pandemic, whose economic effects were far worse.

After coronavirus ground the U.S. economy to a halt in March, the biggest U.S. banks set aside billions of dollars to cover a wave of expected loan defaults. In the months since, a period that saw unemployment surge to a post-World War II high, Americans skipped more than 100 million debt payments.

A gradual reopening of stores, restaurants and factories in recent weeks has given the economy a much-needed boost. But a recent surge in coronavirus cases in big states like Arizona, Texas and Florida has clouded the outlook.

Reflecting the uncertainty about how the economy will fare in the year to come, the Fed’s analysis looked at three extreme scenarios to gauge their effect on banks. The first was a “V-shaped” recovery, in which the economy bounces bank rapidly from a severe downturn. That would result in nearly $560 billion in loan losses across the nine-quarter period that the Fed studied.

A more prolonged downturn that led to a “U-shaped” recovery would cause $700 billion in loan losses. A “W-shaped” recovery in which the economy bounces back quickly but then takes another dip, would result in $680 billion in loan losses.

The analysis excluded capital distributions that were already planned and didn’t take into account government efforts to support the economy, such as expanded unemployment benefits and the Paycheck Protection Program.

Updated: 6-28-2021

Wall Street Funnels Cash To Investors On Stress-Test Success

* Morgan Stanley Doubles Dividend, Announces Stock Repurchases

* Ample Capital Buffers Prompt Fed To Loosen Restrictions

Morgan Stanley led big U.S. banks in raising payouts to investors — by jacking up dividends or announcing plans to buy back shares — after amassing cash piles that easily met the Federal Reserve’s capital requirements.

Dividend payouts by the nation’s six largest lenders will rise, on average, by almost half — and that’s with Citigroup Inc. abstaining from an increase — according to statements issued Monday. Morgan Stanley doubled its quarterly payout while also announcing as much as $12 billion in stock buybacks.

“Morgan Stanley has accumulated significant excess capital over the past several years and now has one of the largest capital buffers in the industry,” Chief Executive Officer James Gorman said in the bank’s statement

Shares of Morgan Stanley climbed 2.9% at 9:51 a.m. in New York trading.

The firms began announcing their plans for distributing capital after getting the green light from the Fed to resume dividend and buyback increases.

All lenders passed the central bank’s stress tests last week, which freed them from remaining pandemic-era restrictions on payouts.

The stress tests used to trigger anxiety across Wall Street, but the banks’ solid showing underscores how comfortable the industry has grown with the exercises. This year, with firms sitting on a massive stockpile of excess cash, the exams were primarily an indicator of how much of that money can be doled out to shareholders.

Wells Fargo & Co., the troubled San Francisco-based lender, announced an $18 billion buyback program and doubled its dividend to 20 cents.

Investors may be less than enthralled with the payout, however, which stood at 51 cents about a year ago when the scandal-plagued firm cut it to 10 cents. Shares of the company declined 0.8% in New York.

Goldman Sachs Group Inc. said it was boosting its quarterly payout 60% to $2 a share, effective Oct. 1, according to a statement. And JPMorgan Chase & Co. is raising its dividend to $1 from 90 cents, and said it continues to be authorized to repurchase shares under a previous plan. Goldman shares advanced 1%.

“The Federal Reserve’s hypothetical CCAR stress test once again showed that banks continue to have strong capital levels and could withstand an extreme outcome while continuing to support the broader economy,” JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon said in a statement.

Bank of America Corp. will increase its dividend 17% to 21 cents, subject to board approval, according to a statement from the Charlotte, North Carolina-based bank. Shares of the company were down 0.6% in New York.

Citigroup Inc. was an outlier among the big banks, holding its dividend steady at 51 cents a share — where it’s been for almost two years. The bank will also be “continuing with our planned capital actions” regarding share repurchases, CEO Jane Fraser said in a statement. Citigroup fell 1.6% in New York.

Congressional Critics

A surge in payouts is welcome news for investors but could put big banks on the defensive again in Washington. Critics including U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts have condemned buybacks and dividends for enriching executives, and have called for lenders to use excess capital to do more for employees.

While Monday marked the first day that the Fed said firms could release their capital plans, companies may choose to disclose their intentions, or provide additional details, at a later date.

Firms don’t need the Fed to sign off on their capital plans, as long as each lender stays above its established capital minimum. If a bank falls below its required stress capital buffer at any point in the year following the stress tests, the Fed can hit it with sanctions, including restrictions on capital distributions and bonus payments.

Updated: 7-12-2021

China Just Cut Reserve Requirements For Its Banks. Why One Economist Is Worried

Trouble At China’s Banks?

The Chinese government has unexpectedly announced a broad-based RRR [reserve requirement rate] cut to be effective July 15. This isn’t the targeted cut mentioned in an important government meeting, and it sends a bad signal. So why does China need this cut? What’s wrong with the economy?

My own view is that the main intention of this cut is to help banks with their capital and liquidity requirements. From the Q&A written by the People’s Bank of China, we understand that this RRR cut aims to increase financial institutions’ capital and liquidity, and lower their cost of doing lending business.

This gives me a sense of unease. Are banks under stress? If this is the case, it implies there could be more bad loans. These bad loans could stem from the recent deleveraging reform.

Banks haven’t been able to lend to real estate developers as easily as before and have shrunk their mortgage business. Fintechs, which banks also lend to, have also been subject to deleveraging reform.

After this RRR cut, banks should have more breathing room on capital and liquidity. But what’s next for the PBoC and banks? Banks cannot change the lending framework for real estate developers. But they could step into microlending left by fintechs, though this is a risky business.

This means banks will continue to suffer from the same issues. And while they have some breathing room for now, this may only last for another quarter or so given that the release of liquidity is quite small compared to loans outstanding.

China may need another RRR cut in the fourth quarter.

Updated: 6-23-2022

Real Stress Hurts Bank Buybacks More Than Fed’s Test

Rising interest rates and bond losses are already curbing share repurchases this year.

Jerome Powell is putting big US banks through two stress tests. The Federal Reserve chair’s merciless interest-rate increases are hitting asset values hard, and that’s likely to prove painful in second-quarter earnings and beyond.

Share buybacks by most big banks are already slower this year than last as they cope with billions of losses on government bonds they own and potentially on debt deals underwritten for clients.

Meanwhile, the just-published results of the Fed’s theoretical crisis exams showed big banks have plenty of capital to survive a severe shock. It ran tougher scenarios than last year, including a bigger rise in unemployment and drop in home prices.

At the same time, the Fed has already told JPMorgan Chase & Co., Citigroup Inc. and Goldman Sachs Group Inc. to build in bigger cushions next year to guard against the systemic risks they present.

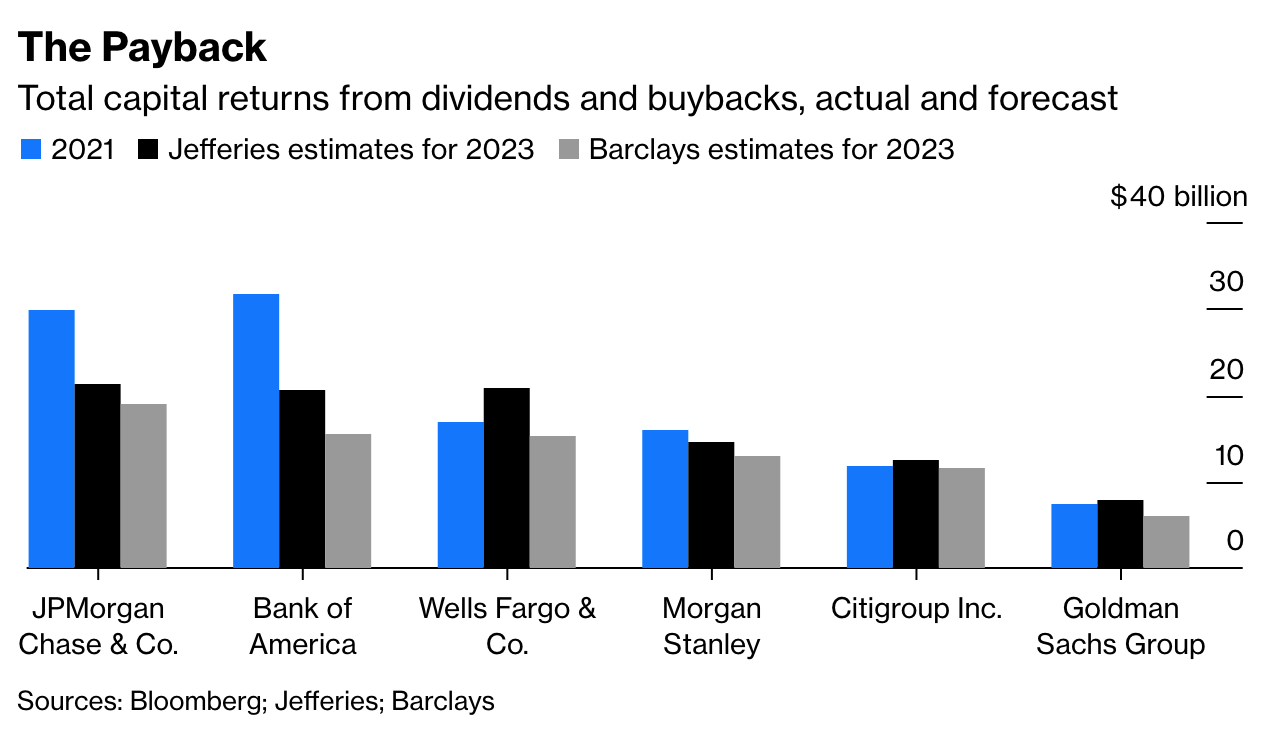

And yet for shareholders, the news is that dividends and buybacks in 2023 will still likely be extremely healthy. In forecasts made ahead of the Fed’s stress test result, JPMorgan was expected to lead the pack with dividends and buybacks in 2023 adding up to $19 billion to $21 billion, according to estimates from analysts at Barclays and Jefferies.

That is way down from 2021’s total of nearly $30 billion, but that included profits held over from 2020 during the depth of the Covid crisis.

Bank of America Corp. and Wells Fargo & Co. are next in line, both forecast by Barclays to return a total of more than $15 billion and by Jefferies to return nearly $21 billion, again much lower than last year.

Morgan Stanley follows, then Citigroup, and Goldman brings up the rear with estimated payouts of $6 billion (Barclays) to nearly $8 billion (Jefferies). The banks can start outlining their capital plans next week.

Next year’s buybacks are likely to be better than this year’s, especially for the big deposit taking commercial banks. JPMorgan has already slowed share repurchases this year in part because of declining values of Treasuries held on its books as interest rates rose. Executives at BofA, Wells and Citi made cautious comments about stock repurchases during first-quarter earnings calls.

All four suffered billions in unrealized losses in the first three months of the year and are likely to do so again because of further Fed rate increases. Very short-term Treasury yields and very long-term ones have risen more in the second quarter than in the first, but yields between two and seven years have risen less.

This should mean losses for banks are less bad, according to Mike Mayo, an analyst at Wells Fargo, who said moves in five-year yields are the best indicator. They could still amount to 2.5% to 3.5% of equity, he estimates.

For investment banks, there could also be big losses on debt they have underwritten for companies, especially those involved in buyout deals, as investor appetite has dried up. Some loans and bonds are being sold at heavy discounts as Wall Street looks to clear risky deals off the books.

The saving grace for some will be strong profits from active trading in currencies, rates and commodity-linked products. Citigroup, for example, expects trading revenue to be up 25% this quarter compared with results in the period a year earlier.

Sharply rising interest rates to fight inflation underpin all of this and should lift revenue for commercial banks through higher net interest income even as they initially roil markets.

Still, shares in all these banks except Wells have underperformed the S&P 500 Index, which shows investors are ignoring the lower risks and greater resilience of banks, Mayo said.

The volatility in banks’ capital returns in recent years and the fact that regulators acted to restrict payouts during the Covid pandemic in 2020 raise questions about the point of the stress tests.

They are meant to prepare banks for the worst so that they can keep making their own decisions on capital when disaster strikes. Critics of the Fed’s tests, meanwhile, say they have been so watered down under the loosening of rules by President Donald Trump’s administration that they are ineffective.

The truth is in between: The tests are important for banks and regulators to exchange information, and they help set bank capital requirements tailored to the real risk they present in a reasonably transparent way.

Bank executives will almost always argue they have too much equity, but shareholders are still reaping handsome rewards. The lessons of previous crises are that regulators are right to err on the side of caution.

Fed Stress Test Finds Big Banks Can Weather Severe Recession

Ability to lend and maintain capital levels in a hypothetical downturn is measured by central bank.

The Federal Reserve gave the biggest U.S. banks a clean bill of health in its annual stress test, saying they would be able to continue lending to households and businesses even in a severe recession.

This year’s stress test measured the 34 biggest banks’ ability to maintain strong capital levels in a hypothetical recession marked by sharply higher unemployment and a steep decline in stock prices.

The banks subject to the test remained above their minimum capital requirements in the test’s worst-case scenario, though they would collectively lose more than $600 billion, the Fed said.

Their capital ratios would decline to 9.7%, more than double their minimum requirements, according to the Fed. Bigger banks have additional surcharges that require them to hold higher levels of capital beyond the minimum.

The severely adverse scenario, as it is known, had U.S. unemployment rising to a peak of 10% in the third quarter of next year. It assumed a 40% decline in commercial real estate prices, a 28.5% drop in home prices, widening corporate bond spreads, a 55% decline in stock prices and increased market volatility.

This year’s hypothetical scenario is tougher than the 2021 test by design, the Fed said. Last year’s test found that the 23 biggest U.S. banks would collectively lose more than $470 billion. Some smaller banks are only required to take the test every other year.

This year, the biggest banks in the country, including JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Bank of America Corp., saw their capital levels fall farther than last year on higher loan and trading losses.

The economy’s swift and strong recovery from the pandemic helped big banks post record profits in recent years. Recession fears, however, are clouding their outlook.

Inflation is at a 40-year high, and Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said this week that higher interest rates in response to rising prices could tip the economy into a recession. Several bank executives have issued similar warnings in recent weeks.

How the banks perform in the tests determines how much capital they must sock away for potential trouble. Once they satisfy that requirement, they are able to return their excess capital to shareholders in buybacks and dividends. Banks are expected to announce their capital plans Monday evening.

Big U.S. banks will likely boost their dividend payouts soon, but total stock buybacks are expected to drop to $13 billion in the second quarter from $36 billion last summer and remain slow, Barclays analysts said in a research note.

The Fed temporarily barred stock buybacks and capped dividend payments in 2020, citing the need to conserve capital while the coronavirus pandemic took hold. Those restrictions were removed last summer.

The stress tests were introduced following the 2008-09 financial crisis, when the U.S. government bailed out some of the largest financial institutions. The results of the first tests helped restore investor confidence in the banking system.

Bank stocks have languished this year after a sharp rally in 2021. The KBW Nasdaq Bank Index is down 24% so far in 2022, a performance slightly worse than that of the S&P 500.

Banks Ace Fed Stress Tests, Pave Way For Shareholder Payouts

* Results Show Top Firms Could Withstand A Severe Recession

* Large Lenders Are Poised To Return $80 Billion To Investors

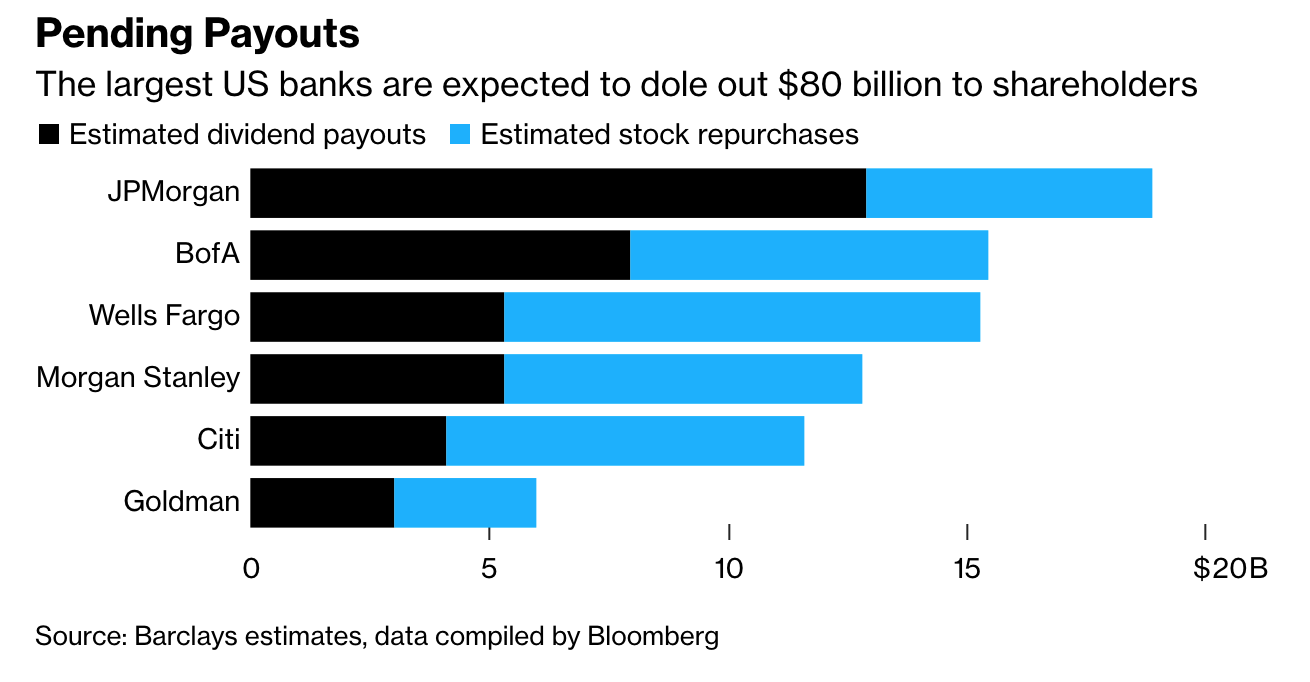

Wall Street’s biggest banks are set to return tens of billions of dollars to investors after all the lenders passed the Federal Reserve’s annual test of their ability to withstand market turmoil.

The banks examined showed that they had enough capital to handle a cocktail of surging unemployment, collapsing real-estate prices and a plunge in stocks, the Fed said in a statement Thursday.

Major firms including JPMorgan Chase & Co., Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs Group Inc. also faced a made-up market shock that tested the resiliency of their trading operations.

While the terms of the tests were announced in February before US inflation had surged to a 40-year high, the scenarios no longer seem as far-fetched amid mounting concerns of a global economic slowdown.

The passing marks effectively give banking giants a green light to return billions of dollars to investors in dividends and share buybacks.

“Banks continue to have strong capital levels, allowing them to continue lending to households and businesses during a severe recession,” the Fed said in the statement.

The Fed said the more than 30 lenders it examined were able remain above their minimum capital requirements during the hypothetical economic meltdown, which would have caused them total projected losses of $612 billion.

Lenders use the tests to assess how much capital they can afford to dole out to investors without falling below the amount they are required to hold as a cushion.

If a firm breaches its so-called stress capital buffer at any point in the year following the exams, the Fed can apply sanctions, including restrictions on capital distributions and bonus payments.

With their results in hand, banks can announce their payout plans starting Monday. Estimates by Barclays Plc analysts indicate that JPMorgan is set to lead the way with $18.9 billion in combined dividends and share buybacks, followed by Bank of America Corp. and Wells Fargo & Co. with $15.5 billion and $15.3 billion, respectively.

In all, US banking giants are set to return $80 billion to shareholders this year, according to data compiled by Bloomberg based on the projections.

“The nation’s largest banks remain well-positioned to absorb a range of potential economic shocks while continuing to support their customers, clients and communities,” Rob Nichols, president of the American Bankers Association, said in a statement. “The industry’s strong balance sheets and high capital levels ensure banks can make the loans that drive our economy even if they face substantial headwinds.”

Last year, dividend payouts by the nation’s six largest lenders rose by almost half after the country’s largest banks amassed mountains of excess capital during the pandemic. Morgan Stanley alone doubled its quarterly payout while also announcing as much as $12 billion in stock buybacks.

The Fed’s 2022 stress tests included “a severe global recession accompanied by a period of heightened stress in commercial real estate and corporate debt markets,” according to the Fed’s website.

In a sign of the Covid-19 pandemic’s impact, the hypothetical downturn “is amplified by the prolonged continuation of remote work, which leads to larger commercial real estate price declines that, in turn, spill over to the corporate sector and affect investor sentiment.”

The scenario featured a peak US unemployment rate of 10%, a real gross domestic product decline of 3.5% from the end of last year and a 55% drop in equity prices. It also incorporates a sharp decline in inflation to an annual rate of 1.25% in the third quarter of 2022 on higher unemployment and lower demand.

Updated: 7-29-2022

US Banks Passed The Latest Stress Test, But Are Still Unhappy

The regulatory checkups by the Federal Reserve are one reason no one’s talking about a financial crisis today.

Wall Street loathes bank stress tests—and arguably owes a lot to them. The regulatory checkups by the Federal Reserve, instituted after the 2008 global financial crisis with the aim of averting another one, run banks’ balance sheets through simulated doomsday scenarios to gauge whether they’d make it through.

This year banks were tested on a hypothetical cocktail of surging unemployment, collapsing real estate prices, and a plunge in stocks.

All 33 of the biggest lenders in the US passed this year’s exam. But the results chafed some of them. JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Citigroup Inc. were told that in the future they would need to increase the amount of high-quality capital they hold to protect against losses, and as a result they will be pausing stock buybacks that return money to shareholders.

Jamie Dimon, the chief executive officer of JPMorgan, lashed out over the test. “It’s a terrible way to run a financial system,” he said during an earnings call.

He called the process capricious and unpredictable, and complained that it could force banks in general to reduce mortgage lending to lower-income people. “Not a benefit to JPMorgan, but it hurts this country,” he said.

In bank accounting, loans are considered assets. Being required to raise the percentage of capital compared to assets doesn’t force a bank to reduce its lending.

The bank can increase capital by raising money from shareholders or by retaining profits, and it will be safer for doing so. In this way, the highest-quality bank capital is similar to the equity you might have on your house—it’s the money you won’t have to scramble to pay back if the market goes against you, because you didn’t borrow it.

Banks often prefer to fund their lending and increase their assets by borrowing cash themselves—say, by issuing bonds—because that’s more profitable in good times. But the point of stress tests is to keep taxpayers from having to bail out banks that take on too much risk.

“The way to do that is to make sure the institutions have more skin in the game, and skin in the game basically means more capital,” says Richard Sylla, a professor emeritus of economics at New York University Stern School of Business.

US banks today have capital of almost 13% of assets, by one key measure that adjusts for risk, compared with about 8% before the financial crisis.

Dimon’s latest criticism of post-crisis regulations—he’s bemoaned their complexity for years—focused on what he says was an unrealistic stress-test result. “I think they had us losing $44 billion,” he said. “There’s almost no chance that that would be true.”

He noted the bank’s “huge underlying earnings power” and steady revenue in consumer banking, asset management, and other areas. Banks complain that the Fed’s calculations are a black box, making it difficult for them to know whether they’re allocating capital to the right businesses.

“I love and hate the Fed stress test at the same time,” says Mike Mayo, a banking analyst at Wells Fargo. He loves that banks are less likely to fail now—no small thing when other parts of the economy, from inflation to consumer confidence to crypto, seem headed in the wrong direction. “But I also hate the Fed stress tests because of the volatile nature of its outcomes.”

Still, some analysts think that’s a small price to pay. “We don’t doubt that the testing mechanism is an imperfect instrument, but it seems that the biggest problem from JPMorgan’s perspective is that the test results have some teeth” in forcing JPMorgan to be more conservative with buybacks, wrote Kathleen Shanley, an analyst at Gimme Credit, an independent research company, in a note to clients.

Her readers tend to be bondholders, who prefer banks to be safer even if it means stock investors get smaller rewards. “There was no mention of the fact that higher capital ratios might benefit the bank and even lower its funding costs over time.”

Anat Admati, a professor of finance and economics at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business, has her own criticisms of the reliance on stress tests and agrees they’re overcomplicated.

But she and others have advocated instead that banks be required to have much more equity to absorb losses. Barring that, she says stress tests at least are a way “that regulators are trying to somehow prevent disasters.”

Updated: 10-7-2021

Bankers On Back Foot As Push To Dilute EU Basel Rules Flounders

* European Commission Seen Rejecting Plea To Dilute Basel III

* Banks Will Have Less Autonomy In Assessing Loan Risks

European banks are falling short in their lobbying effort against oncoming stricter capital rules which would limit their ability to boost shareholder returns, according to people familiar with the matter.

Lenders expect the European Commission to disregard their plea to retain significant freedom to assess the riskiness of their own loans, as the region implements the global bank standards known as Basel III, according to people familiar with the matter.

A Commission proposal on the subject is expected this month, after which member states have their say.

The banks are now focused on winning extra flexibility in other areas, such as easier terms on assessing the capital required to be held against mortgages, they said.

Global regulators spent a decade after the financial crisis forcing banks to boost their equity reserves to avoid a repeat of the 2008 credit crunch and ensuing taxpayer-bailouts.

European banks still face a bigger jump in required capital levels than their more-profitable U.S. peers, as the full weight of the Basel accords is phased in by the EU this decade.

Frenzied Effort

One of the most important parts of the updated Basel standards is the hard limit on the extent to which banks are allowed to calculate loan risk themselves instead of using a standardized approach, a rule known as the “output floor.”

Banking lobbies have argued that this should be split off as an additional requirement — or “parallel stack” — leaving several of their relevant capital buffers unchanged.

Bank executives often contend that higher capital requirements curtail their ability to lend to businesses and the wider economy.

The legislation matters in particular now, as lenders seek to win over investors after regulators imposed constraints on capital returns during the pandemic.

Banks including French lender BNP Paribas SA are already signaling they want to boost returns next year, though the implementation of Basel III could weigh on other banks’ plans.

“Of course the banks are in a last frenzied lobbying effort and retrying some of the same old arguments they’ve made,” Carolyn Rogers, the secretary general of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, said at a conference on Wednesday.

A group of central banks and regulators pushed back last month and sent a letter to the Commission calling for Europe to not water down or delay the Basel standards.

That letter probably quashed banks’ calls for a parallel capital requirement, said the people familiar with the matter. The banks are now preparing to focus their lobbying on ensuring that the EU takes a more granular approach to capital requirements for mortgages, provides exemptions for loans to companies that lack credit ratings, and allows flexibility in the calculation of so-called operational risk, they said.

The European Commission declined to comment on the matter. Applying the output floor to all capital buffers “overburdens” banks and the economy, a spokesperson for the European Banking Federation said in an email to Bloomberg.

Trust At Stake

Tackling issues such as how to treat unrated companies would help “avoid a steep increase in the cost of lending,” the EBF said.

“Limiting the ability of banks to choose their own risk models via the Basel reform is a positive development since capital ratios are still historically low,” said Harald Benink, a professor of banking at Tilburg University.

“Banks should be able to pass on the additional costs to clients given that interest rates are low anyway, or they can restrict payouts to shareholders in an effort to boost profitable lending.”

The Basel standards will be applied step-by-step until 2028. They are expected to increase the capital requirements of the biggest lenders by 23% on average, the EBA said last month.

Elizabeth McCaul, a member of the European Central Bank’s supervisory board, says higher capital requirements showed their worth in the pandemic as banks were able to keep lending during the lockdowns.

“Watering down Basel III reforms in Europe because of so-called concerns about recovery puts at risk the broader trust that European banks now enjoy and that trust is something that we know would be needed in any future crisis,” she said this week.

Updated: 10-25-2021

Europe Scales Back New Bank Capital Proposal To Boost Recovery

* EU Will Give Banks More Flexibility According To Latest Draft

* Proposal To Be Released Wednesday By European Commission

The European Union plans to soften the blow to banks from new capital rules, arguing that an easier stance ensures lenders can keep funding the economy as it recovers from the shock of the pandemic.

In its implementation of the global banking standards known as Basel III, the European Commission will include flexibility on several issues banks had lobbied for while stopping short of meeting the industry’s key demand of retaining significant freedom to assess the riskiness of their own loans, according to a draft proposal seen by Bloomberg. On average, banks will see their capital requirements rise by less than previous predictions.

Global regulators spent a decade after the financial crisis forcing banks to boost their equity reserves to avoid a repeat of the 2008 credit crunch and the ensuing bailouts by taxpayers. European lenders still face a bigger jump in required capital levels than their more profitable U.S. peers, as the full weight of the Basel accords finalized in 2017 is phased in by the EU this decade.

Here are some of the main points in the proposal, which could still change before its scheduled publication on Wednesday:

Capital Requirements

The measures are expected to increase banks’ capital requirements by as much as 8.4% on average by 2030. The European Banking Authority said last month that the Basel III standards would drive up the Tier 1 capital requirements of 99 banks by 13.7% on average, based on data from the end of 2020. The industry had sought to limit the increase to about 5%.

Measuring Risk

The proposal includes a hard limit on the degree to which banks are allowed to estimate their own risk, known as the output floor. That was necessary because some lenders took a rosier view than warranted, yet the industry still lobbied to largely circumnavigate the output floor. The commission suggests that it wants to “strengthen the risk-based approach” rather than replace it with a one-size-fits-all approach.

Corporate Loans

Banks will eventually face higher capital requirements for loans to companies that don’t have credit ratings. It’s a move that lenders and some government officials had warned could hurt the economy because European companies rely on bank loans rather than bond markets and often don’t have such ratings. However, the commission suggests that banks be allowed to treat such loans as investment grade as a “transitional arrangement,” depending on their probability of default.

Mortgages

The commission suggests that European countries have the option to allow banks to apply for preferential treatment of “low-risk” loans secured by residential mortgages. The EBA would monitor that transitional treatment, according to the draft seen by Bloomberg.

Sustainability

The commission also wants to introduce harmonized definitions of environmental, social and governance risks suggested by the EBA into the EU’s banking rules. Banks will be required to report on these to their relevant regulators.

Payouts

The commission said it opted not to give regulators new powers to restrict dividends and share buybacks by banks after the watchdogs said they didn’t need the power. The European Central Bank’s de facto ban on such payouts last year hit the share prices of lenders and was criticized as potentially undermining confidence in the industry.

Updated: 3-20-2023

Depositors Stress Test Their Banks Like Bitcoiners Perform “Proof-of-Keys”

Some entrepreneurs ask tough questions or shift deposits.

The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank has created a new worry for many small businesses: what to do with their cash.

Some owners of small and midsize businesses are moving funds to other institutions, splitting them between multiple banks, moving cash into money-market funds or buying Treasurys. Others are more closely reviewing the finances of their banks, while some entrepreneurs are even thinking about the potential risks for key partners and customers.

Responding to the recent banking-industry turmoil is particularly challenging for small businesses, which typically don’t have large finance teams or sophisticated cash-management strategies. Small-business owners with conservative habits often keep lots of cash on hand as a cushion. Loan restrictions can make it tough to split that cash among multiple institutions.

“I think we need to analyze banks just like they analyze us,” said Brent Frederick, owner of Minneapolis-based Jester Concepts, which has five restaurants including Butcher & the Boar and a concession operation that includes food trucks, a food trailer and stadium locations. “What is the bank’s core value? What do their balance sheets look like?”

Mr. Frederick, who has more than 300 employees, has long kept millions of dollars in deposits at one large, national bank. Now he is considering shifting funds to a handful of smaller banks that have provided the restaurant group with loans.

“It seems like the bigger banks are having the bigger problems,” he said. “The smaller banks, the local banks, provide that small-business support.”

Many small-business owners are doing nothing for now, but the actions of others provide an early sign of how the banking industry’s troubles are rippling through the economy and leading some entrepreneurs to scrutinize relationships and habits they took for granted.

“There is a very broad ripple effect,” said Jennifer Pearce, a managing principal with Boulder, Colo.-based AVL Growth Partners, a provider of chief financial officer and accounting services to small and midsize companies. “It’s not just where did you bank? It’s where did my customers bank? Where are my vendor providers banking?”

Those questions have been most common among companies whose business partners had some connection to Silicon Valley Bank, she said.

Gabe Abshire, founder and chief executive of Utility Concierge in Dallas, is in discussions with potential equity investors for his 150-person company, which helps customers set up home services and utilities when they move.

Mr. Abshire received a call last week from a banker representing one potential investor, assuring him that the bank’s financing was sound.

He now plans to learn more about where other potential investors keep their funds, how they are financed, where they bank and how they are securing their funds.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and President Biden in recent days have sought to calm jittery consumers and businesses and reassure them that the U.S. banking system is sound.

Larger lenders, including those who brought capital to First Republic Bank, also sought to ease fears from depositors about banking with regional, midsize and smaller institutions.

Ami Kassar, CEO of business-loan adviser MultiFunding, said he worries that if customers decide to move funds from smaller banks to larger ones, that outflow could ultimately hurt small businesses by leaving them with fewer lending options.

Banks had begun tightening their lending standards toward the end of last year as rising interest rates increased the amount of cash flow needed to cover loan payments, said James Arnold, CEO of American Bank of Commerce in Lubbock, Texas.

“We were seeing tightening before we had this Silicon Valley issue,” said Mr. Arnold, whose community bank has $1.5 billion in assets. “It may be a little too early to tell if this is going to exacerbate it,” he said. Like many bankers, Mr. Arnold has been fielding questions from customers and reaching out to reassure them.

Griffin Dooling, chief executive of Blue Horizon Energy in Minnetonka, Minn., is considering moving one or two months of cash into a second bank or securing a credit line with another lender that the developer of commercial and industrial solar projects could draw on in an emergency.

“We are having conversations about treasury management that we’ve never had before,” said Mr. Dooling, whose bank called offering reassurances last week.

Many small-business owners wish they had enough cash to worry about exceeding the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.’s $250,000 limit on deposit insurance. But it is easy for even a modest-size business with conservative habits to exceed that limit, said Ryan Hurst, a partner with RKL LLP, an accounting firm in Lancaster, Pa.

“Call it the rainy-day fund,” Mr. Hurst said. “They feel more comfortable having more cash at their disposal.” Most of RKL’s small-business clients don’t appear rattled by the recent bank failures, he said.

Unlike large corporations, most smaller companies don’t have sophisticated treasury management operations, making responding to recent events more challenging.

“I’m not set up to evaluate the balance sheet of a bank,” said Alan Pentz, chief executive of Corner Alliance Inc., a federal contractor based in Washington, D.C., with 70 employees. “Treasury management is handled by the same person who does payroll, projections and 50 other things.” Corner Alliance’s bank called last week offering reassurances, he said.

Loan covenants can present another challenge for companies rethinking cash management. Peter Elitzer, CEO of Huck Finn Clothes Inc., which has about 600 employees, said his loan agreements have typically required his company to keep all of its deposits with the lender or, at the least, an amount exceeding the FDIC’s $250,000 standard deposit-insurance coverage limit.

Huck Finn, based in Latham, N.Y., has 60 different bank accounts in proximity to its 71 Label Shopper and Peter Harris stores, which are located in small and midsize cities.

The bank holding the retailer’s main line of credit sweeps those accounts twice a week and transfers the money into an account at the larger bank. A second lender that holds the company’s real-estate loans has its own deposit requirements.

Mr. Elitzer said he is asking his lenders to relax the deposit requirements. “I’ve begun the conversation and am not getting a great reception,” he said. “They are saying we are so stable. Everyone always is until they are not.”

Updated: 8-14-2023

US-Chartered Banks Hold A Whopping 2.9 Trillion Of Commercial Real Estate Debt AKA Half-Empty Office Towers

Office buildings have been plummeting in value because of hybrid work, all commercial real estate faces challenges as low-interest loans mature amid higher rates, and look who’s holding the bag: the nation’s small and midsize banks, already facing doubters after deposit runs led to the failure of several of them earlier this year.

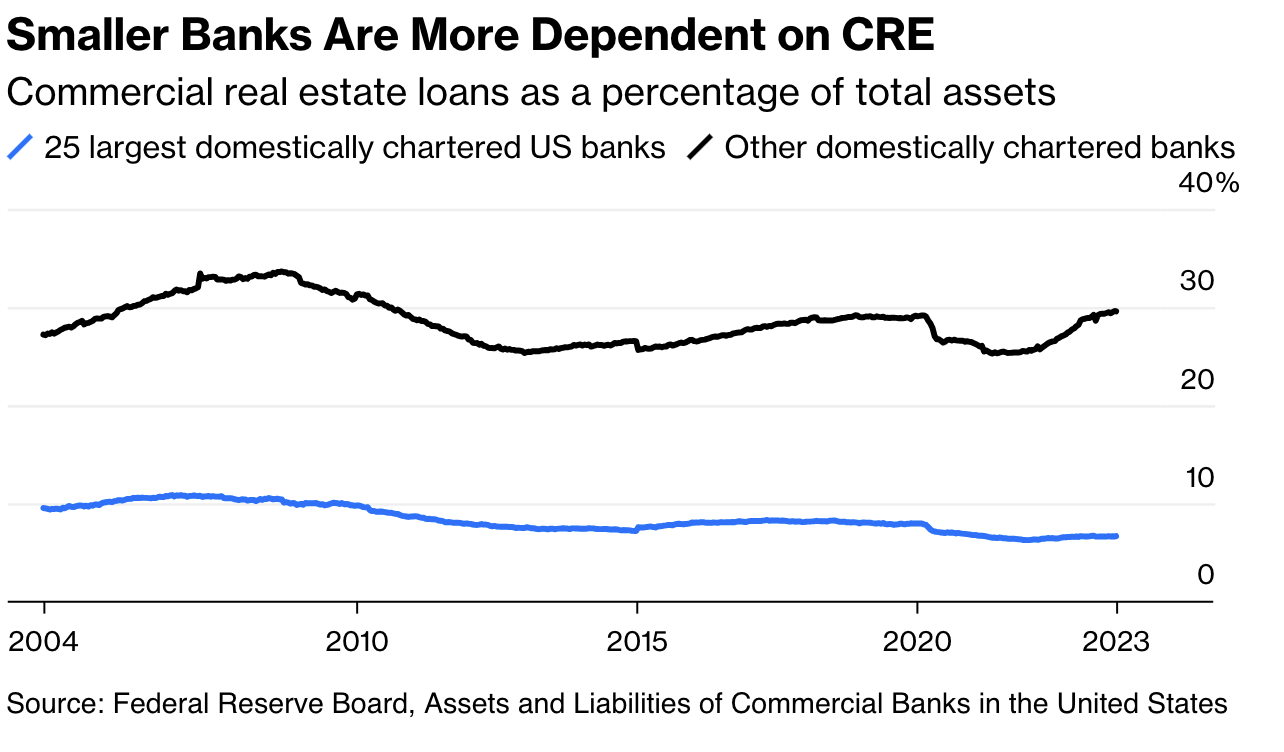

Happily, this factoid isn’t true. That is, small banks — defined as those not among the country’s 25 largest — do in fact hold 69% of the commercial real estate loans on the balance sheets of domestically chartered commercial banks, up from 60% five years ago, according to the Federal Reserve’s weekly reports on bank assets and liabilities.

But most US commercial real estate debt is owed to lenders other than domestically chartered commercial banks.

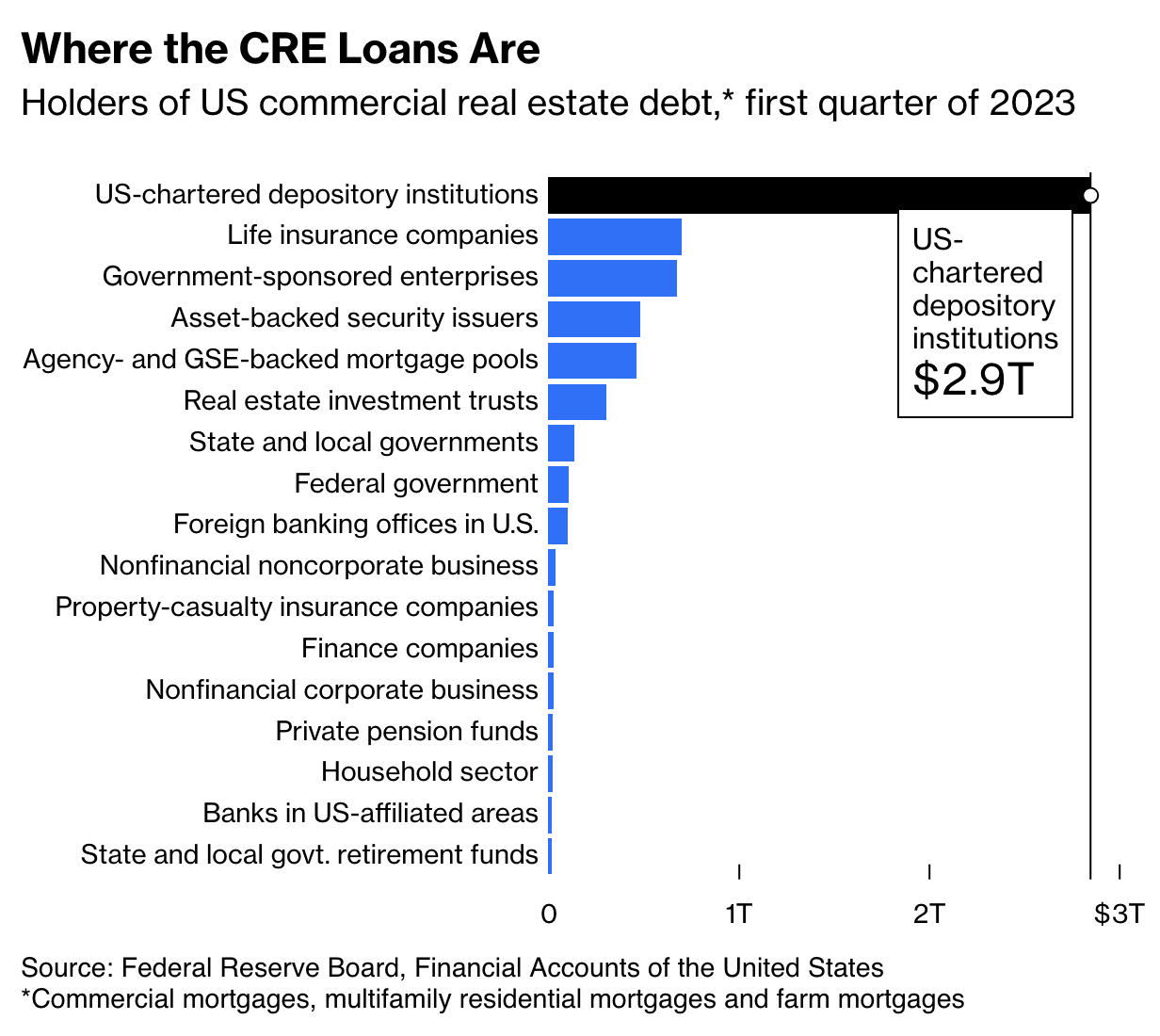

As of the end of March, this time according to the Fed’s quarterly Financial Accounts of the United States, domestic depository institutions (aka banks)1 held 47% of CRE debt, which works out to about 32% of the total in the hands of banks outside the top 25.

That’s much less than 70%. It’s still a lot, though, and no other class of CRE lender comes close to the banks.

Perhaps more to the point for those worried about smaller banks’ commercial real estate exposure, CRE loans make up a much larger share of assets at smaller banks than they do at the 25 biggest.

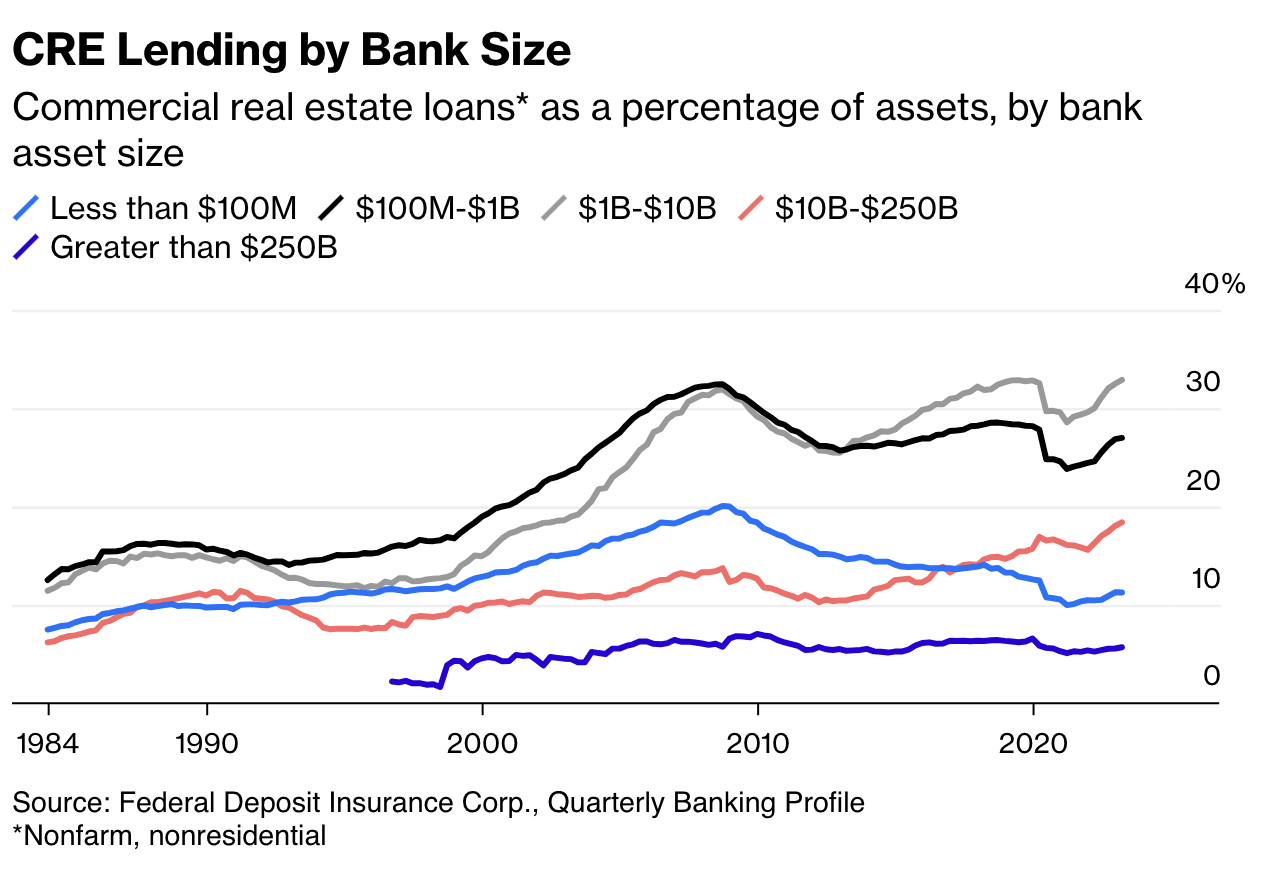

A longer-term view from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. that divides banks into five asset-size classes (and uses a narrower definition of commercial real estate) makes clear that the CRE concentration is highest for banks in the $100 million to $10 billion asset range — community banks, basically.

These banks usually serve smaller cities, or specific communities within larger ones, and their loans seldom finance big downtown office buildings. At OP Bancorp, which serves the Korean-American community in Los Angeles and where CRE loans make up almost 40% of assets, the average balance on those loans is just $838,526.

At Mountain Commerce Bancorp Inc. in Knoxville, Tennessee, where CRE loans are 47% of assets, the loans are distributed among not just retail, warehouses and offices but hotels, campgrounds, marinas, mini-storage facilities and vacation rentals.

At West Bancorporation Inc. in West Des Moines, Iowa, where CRE loans are 49% of assets, a recent investor presentation emphasizes that “office lending makes up less than 7% of the total loan portfolio, none of which is located in major metropolitan downtown areas.”

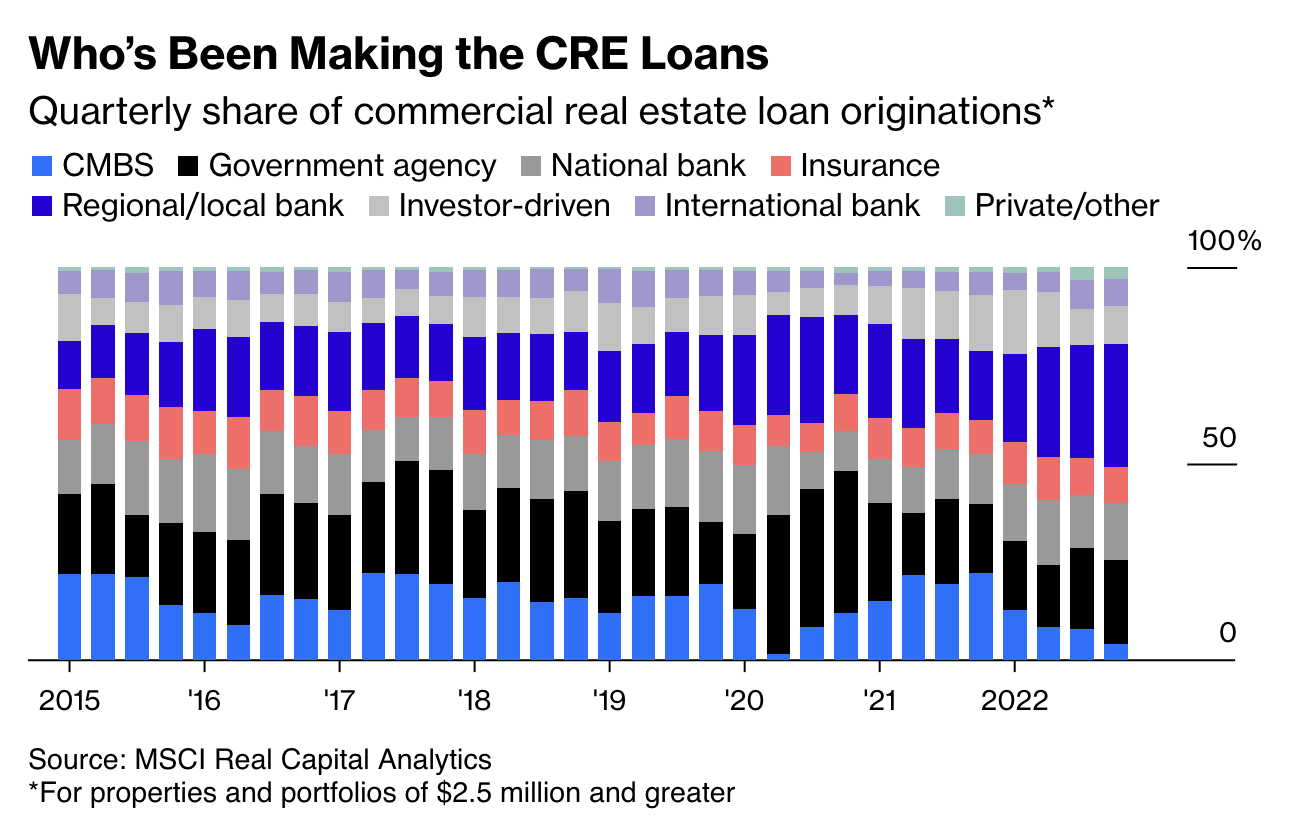

MSCI Real Capital Analytics, which tracks originations of commercial real estate loans for properties and portfolios worth $2.5 million or more, reports that the share originated by local and regional banks has more than doubled since late 2018, to 31% from 15%.

This increase is due in large part to deal activity shifting to smaller markets that other lenders are less likely to serve, said MSCI Real Assets team chief economist Jim Costello, who has been pointing out the falsehood of the 70% factoid for several months.

The biggest decline in origination share has been for commercial mortgage-backed securities, which tend to be used for larger projects.

On the whole, smaller banks seem to have been taking advantage of the shifts in economic activity causing distress in big urban office markets rather than being victimized by them. Also, because so many of their loans have been originated since 2019, relatively few will be maturing this year or next.

Of course, a low-interest loan originated in 2021 doesn’t do anything good for a bank’s profitability, and the fact that smaller banks are so dependent on commercial real estate lending as opposed to, say, trading, means that they will continue to struggle in the current interest-rate environment relative to the giants.

But what seems to be the biggest, scariest challenge facing commercial real estate in the US at the moment — what to do about all those half-empty downtown office buildings — is for the most part not a small-bank problem.

Updated: 9-6-2023

Real-Estate Doom Loop Threatens America’s Banks

Regional banks’ exposure to commercial real estate is more substantial than it appears.

Bank OZK had two branches in rural Arkansas when chief executive officer George Gleason bought it in 1979. The Little Rock lender today has billions of dollars in commercial real-estate loans, including for properties in Miami and Manhattan, where it is helping fund the construction of a 1,000-foot-tall office and luxury residential tower on Fifth Avenue.

Regional banks across the country followed a similar playbook, gorging on commercial real-estate loans and related investments in big cities over the past decade.

With the commercial real-estate market now in meltdown, those trillions of dollars in loans and investments are a looming threat for the banking industry—and potentially the broader economy. Banks’ exposure is even bigger than commonly reported.

The banks are in danger of setting off a doom-loop scenario where losses on the loans trigger banks to cut lending, which leads to further drops in property prices and yet more losses.

Bank OZK hasn’t pulled back from lending, but it has started to see some signs of market trouble. In January, a developer defaulted on a roughly $60 million loan from Bank OZK after construction costs escalated, the bank said.

The loan was considered relatively safe because it was far below the building site’s value of $139 million in 2021. In December, a new appraisal put the property’s value at $100 million.

The bank is effectively stuck with the property. “Buying land in the current unstable environment is not something that a lot of people will do,” Gleason, the CEO, said during an April earnings call. Bank OZK declined to comment.

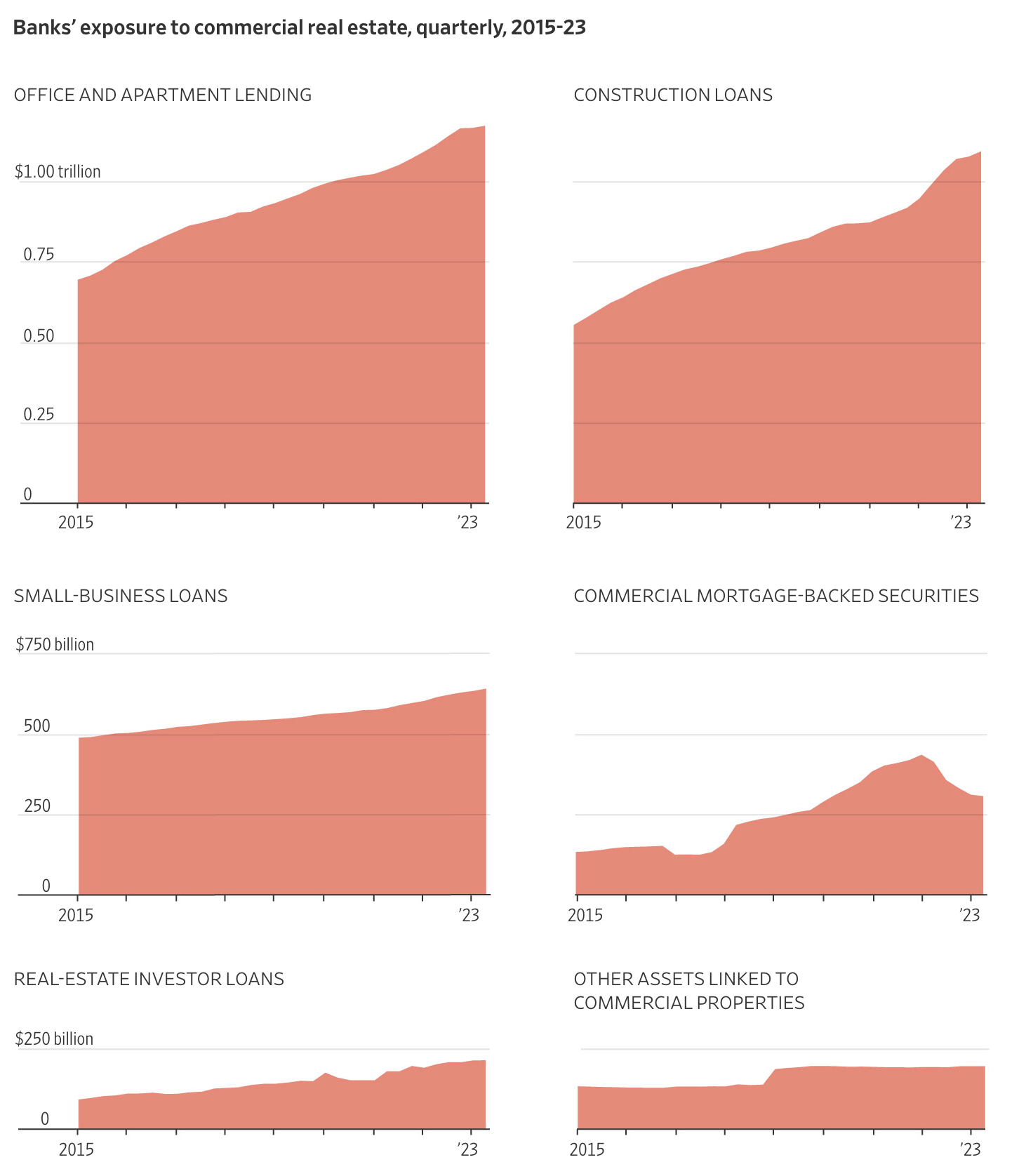

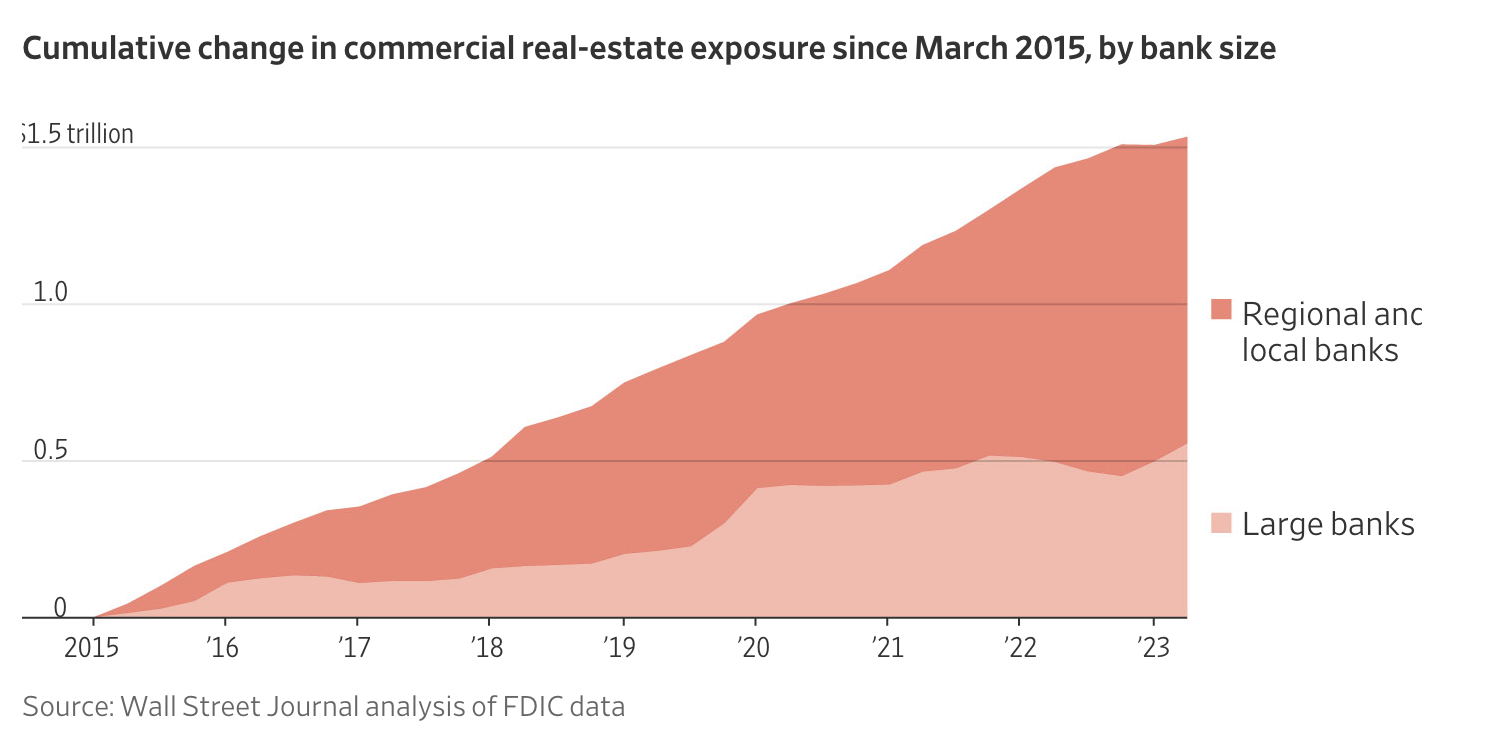

Today’s troubled market, fueled by rising interest rates and high vacancies, follows years of boom times. Banks roughly doubled their lending to landlords from 2015 to 2022, to $2.2 trillion.

Small and medium-size banks originated many of those loans, and all that lending helped push up property prices.

Bank OZK’s success over the years allowed Gleason to build himself a 27,000-square-foot French chateau-style mansion in Little Rock, which he filled with a vast collection of European art. “I’ve never said that what we do is risk-less,” Gleason told the Journal in 2019. Still, he added, he considers OZK “probably the most conservative” commercial real-estate lender.

Over the past decade, banks also increased their exposure to commercial real estate in ways that aren’t usually counted in their tallies. They lent to financial companies that make loans to some of those same landlords, and they bought bonds backed by the same types of properties.

That indirect lending—along with foreclosed properties, trading portfolios and other assets linked to commercial properties—brings banks’ total exposure to commercial real estate to $3.6 trillion, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis. That’s equivalent to about 20% of their deposits.

The volume of commercial property sales in July was down 74% from a year earlier, and sales of downtown office buildings hit the lowest level in at least two decades, according to data provider MSCI Real Assets.

When deals begin again, they will be at far lower prices, which will shock banks, said Michael Comparato, head of commercial real estate at Benefit Street Partners, a debt-focused asset manager. “It’s going to be really nasty,” he said.

Lending is the lifeblood of all real estate, and regional and community banks have long dominated commercial real-estate lending. Their importance grew after the 2008 financial crisis, when the country’s biggest banks reduced their exposure to the sector under scrutiny from regulators. Low interest rates made higher-yielding real-estate loans lucrative to hold.

That strategy now appears risky after the Federal Reserve raised interest rates. Banks are under pressure to pay depositors more to keep customers from fleeing to higher-yielding investment alternatives.

Without cheap deposits, banks have less money to lend and to absorb losses from loans that go bad. Depositors withdrew funds from many small and regional lenders earlier this year after the collapse of three midsize banks stoked fears of a systemwide crisis.

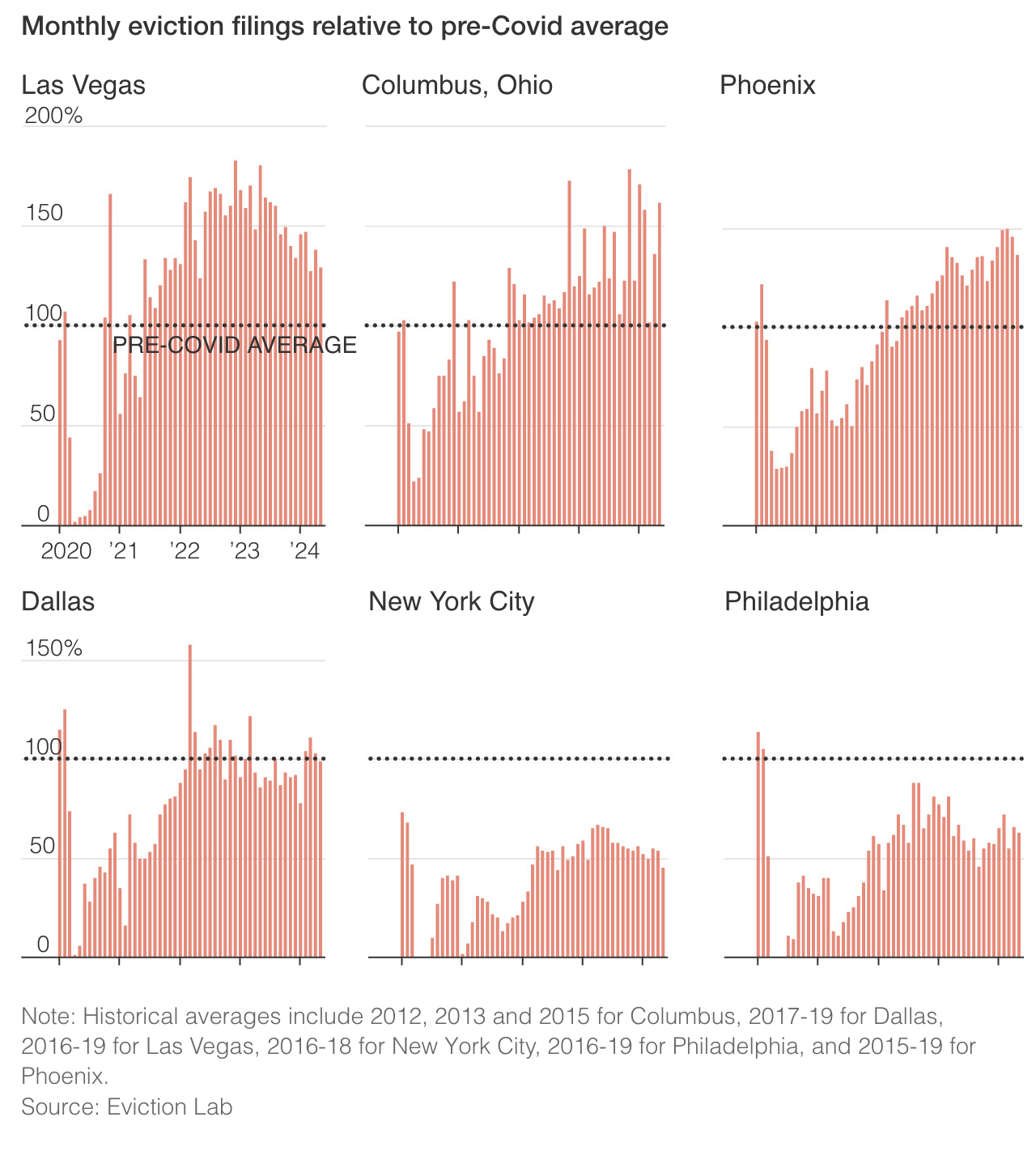

The doom-loop scenario is starting to play out in big cities where office vacancies have soared. Real-estate investors that are unable to refinance their debt, or can only do it at high rates, are defaulting.

The lenders, no longer getting the debt payments, often have to write down the value of those mortgages. Sometimes the bank ends up owning the property.

“The plumbing is clogged right now,” said Scott Rechler, chief executive of real-estate investor RXR. “And that is going to create a backup that will eventually overflow on the commercial real-estate markets and on the banking system.”

When Rechler asks banks to refinance his office loans now, few respond. In some cases, he said, it’s not even worth trying. Rechler had a $240 million mortgage coming due on a 33-story office building in lower Manhattan. Vacancies were high, renovating or converting the building would be expensive and the cost of a new mortgage was way up.

He ran the numbers and decided to default on the loan. RXR said that it’s been working with the lender to market the building for sale to repay the loan at a discount, and that they have discussed possible loan modifications if the building isn’t sold.

Besides banks, lenders such as private debt funds, mortgage REITs and bond investors can also provide funding—but many of them are financed by banks and can’t get loans. “We are seeing a serious credit crunch developing,” said Ran Eliasaf, managing partner of Northwind Group, a private real-estate lender.

Earlier this year, Buffalo, N.Y., regional lender M&T Bank reported nearly 20% of loans to office landlords were at higher risk of default. The bank has reduced commercial estate lending by 5%.

At the end of June, the bank wrote off $127 million worth of loans for three offices and a healthcare facility in New York City and Washington, D.C., according to the company.

It also has unrealized losses on $2.5 billion worth of securities that are tied to loans for offices, apartments and other commercial properties, according to the Journal’s analysis. M&T declined to comment.

Darren King, who oversees retail and business banking at M&T, said at a June investor conference that the bank’s commercial-real estate losses would be a slow grind. “It won’t be Armageddon all in one quarter,” he said.

For its analysis, the Journal tallied hundreds of billions of dollars worth of indirect lending, which often isn’t clearly disclosed, by analyzing banks’ reports filed with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. and tapping former bank examiners for their knowledge of bank lending practices.

Between 2015 and 2022, banks more than doubled their indirect real-estate exposure. That included loans to nonbank mortgage companies and to real-estate investment trusts that own and operate buildings and lend to landlords.

It also included investments in bonds known as commercial mortgage-backed securities, or CMBS. Banks boosted lending to small businesses that used property as collateral as well.

Holdings of CMBS and loans to mortgage REITs and other nonbank lenders accounted for about 18% of the nearly $3.6 trillion in commercial real-estate exposure in 2022, or nearly $623 billion, according to the Journal’s analysis.

The first quarter of 2023 marked the first decline in banks’ commercial real-estate holdings since 2013, according to the Journal’s analysis. At that point, banks’ overall securities holdings had lost nearly $400 billion in value, largely due to higher interest rates.

Banks don’t have to mark down the value of loans in most cases, so the real losses are likely greater.

Banks with less than $250 billion in assets held about three-quarters of all commercial real-estate loans as of the second quarter of 2023, the Journal’s analysis shows. They accounted for nearly $758 billion of commercial real-estate lending since 2015, or about 74% of the total increase during that period.

That increase in lending helped boost commercial real-estate prices by 43% from 2015 to 2022, according to real-estate firm Green Street.

Banks and real-estate developers could be relieved from a downward spiral by lower interest rates or by investors stepping up to buy distressed properties.

Wall Street firms are raising funds to scoop up properties, but many properties will likely be sold at well below their recent prices, potentially triggering losses for owners and lenders.

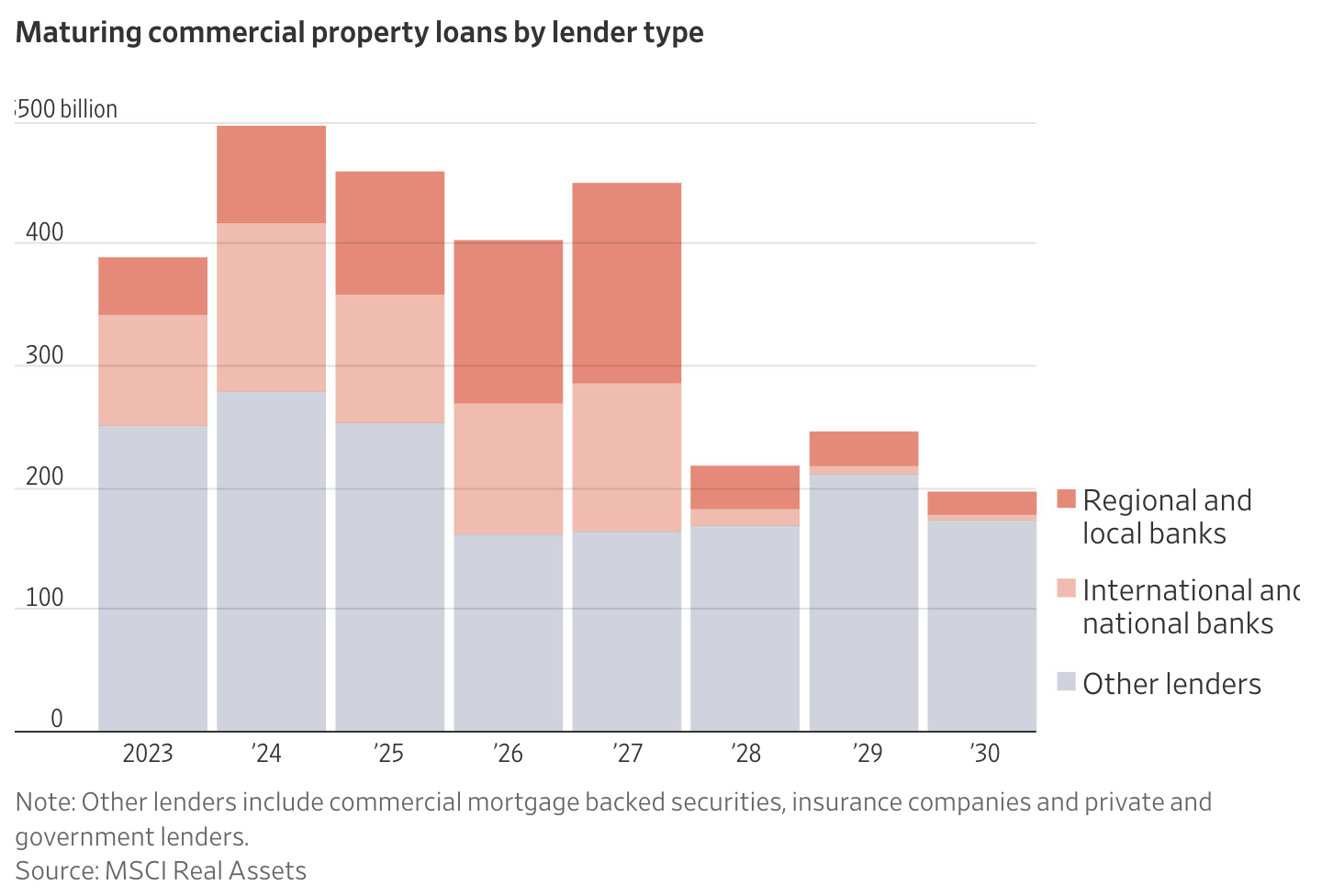

Roughly $900 billion worth of real-estate loans and securities, most with rates far lower than today’s, need to be paid off or refinanced by the end of 2024.

Coming Due

Nearly $900 billion in commercial property loans are maturing this year and next, forcing many landlords to seek out more expensive financing from private investors and banks still willing to lend.

Real-estate developer Riaz Taplin’s financier of 20 years, First Republic Bank, failed in May. That put him on a scavenger hunt for cash.

The San Francisco Bay-area developer was turned down by a subsidiary of regional lender PacWest Bancorp. The bank was a big real-estate lender but many of its depositors fled in the spring, worried about potential losses.

“They’re like: Riaz, we’re just trying to get through the storm,” he said. “Call back when it’s not a torrential downpour.”

PacWest was bought by Banc of California in July for about $1 billion. By then the bank had already sold a real-estate lending unit and a $2.6 billion property portfolio. PacWest and Banc of California declined to comment.

Taplin said he is still able to get loans from other banks, but they are smaller, more cumbersome and take longer to close. And banks will only lend to him if he deposits money there, he said. He now has deposits with four banks and has to constantly move money among them.

Regulators have been warning banks about commercial real-estate lending for years. In 2015, the country’s banking regulators joined together to warn that high concentrations of commercial mortgages and poor risk management put banks “at greater risk of loss or failure.”

Many banks responded by making individual loans less risky, but collectively increased lending and loosened their underwriting standards in other ways.

Centennial Bank, based in Conway, Ark., became a big funder of developers building luxury skyscrapers in New York and Miami. Construction loans are among the riskiest types of real-estate lending.

John Allison, chairman of the bank’s holding company, Home BancShares, told the Journal in late 2019 that representatives from the Federal Reserve urged him to slow down the bank’s lending. “They’re telling us the construction lending space is going to blow up…and the world is coming to an end,” Allison recalled.

“And I said, ‘You know what? I don’t see it.’” Centennial continued increasing its construction loans, although they grew more slowly than deposits during the pandemic.

Home BancShares said it didn’t lose money on construction loans and that a surge in deposits stashed away in supersafe investments reduced the bank’s risk. “If the big, bad wolf shows up it will hurt a lot of banks, but it won’t hurt Home BancShares,” Allison said in a recent interview.

In June, after the failure of three regional banks, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell called for “regulatory strengthening” for regional and local banks because of risky levels of commercial real-estate exposure.

Regulators’ playbook for banks now is similar to its strategy after the 2008 financial crisis: allow banks to work with struggling borrowers and allow them to keep mortgages on their books at face value in many cases.

That approach will be ineffective because interest rates have risen so much, said Tyler Wiggers, a lecturer at Miami University in Ohio and former adviser to the Federal Reserve Board on commercial real estate.

“All of a sudden banks have borrowers who are saying, holy crap, I was paying at 3.5% and now I’m paying 7.5%,” he said. “If borrowers aren’t able to service their debt then banks have to recognize this as a bad loan.”

Banks are selling commercial mortgage-backed securities. While mortgage-backed securities helped cause the 2008-09 financial crisis, more recently issued securities are considered safer than their precrisis counterparts because lending standards are now more conservative.

Banks own about half of the bonds outstanding, according to Bank of America Global Research, the result of a pandemic-era buying binge.

Banks added $131 billion to their CMBS holdings in 2020 and 2021. Real-estate companies happily met that demand by doubling their annual issuance to $110 billion in 2021, according to commercial real-estate data company Trepp. CMBS issuance fell to $16.4 billion in the first half of this year.

When banks were snapping up CMBS, property owners were able to load up on debt tied to their buildings. In early 2021, an affiliate of Brookfield Asset Management borrowed $465 million in CMBS and other debt against the Gas Company Tower, a 52-story office building in downtown Los Angeles.

At the time, appraisers valued the property at $632 million, according to Trepp, up from a valuation of $517 million when Brookfield bought the building in 2013. When the loans came due this February, the owner defaulted. An appraiser earlier this year cut the building’s estimated value to $270 million.

Updated: 7-5-2024

JPMorgan Warns It’s 86 Million Customers: Prepare To Pay For Your Bank Accounts!

They are also planning to further limit debit-card fees and how much they can charge to software companies like Venmo and CashApp for accessing and using their customers’ data. On top of that, new bank capital rules would make it harder for banks to lend by requiring them to hold more reserves against mortgages and credit-card loans.

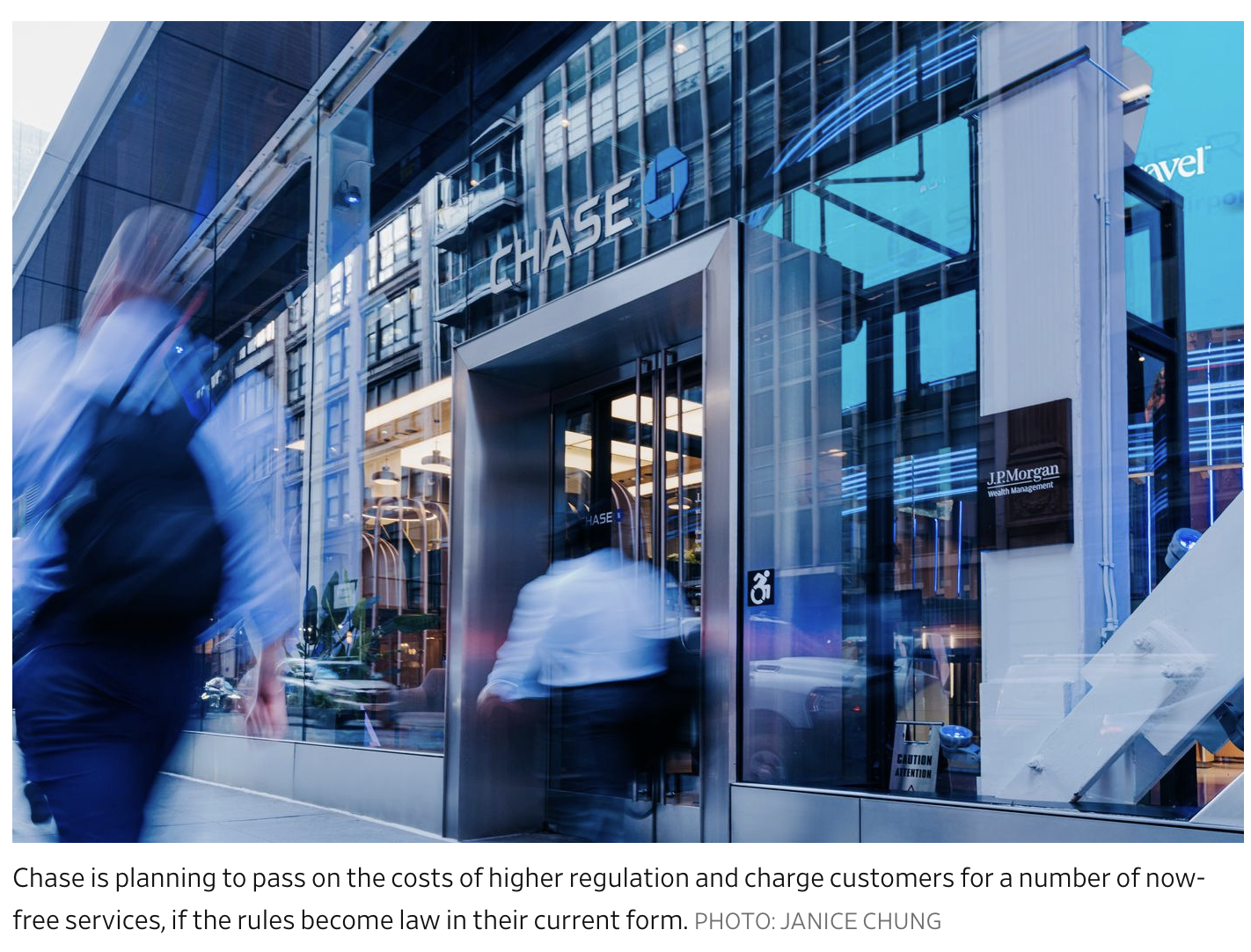

Head of Chase says bank customers stand to lose out if Washington enacts new rules.

The head of America’s biggest retail bank has a warning for its 86 million customers: Prepare to pay for your bank accounts.

Marianne Lake runs Chase Bank, the sprawling franchise inside JPMorgan Chase that is the country’s biggest bank for consumers and one of its biggest credit-card issuers. Lake is warning that new rules that would cap overdraft and late fees will make everyday banking significantly more expensive for all Americans.

Lake said Chase is planning to pass on the costs of higher regulation and charge customers for a number of now-free services, including checking accounts and wealth-management tools, if the rules become law in their current form. She expects her peers in the industry will follow suit.

“The changes will be broad, sweeping and significant,” Lake said. “The people who will be most impacted are the ones who can least afford to be, and access to credit will be harder to get.”

This isn’t the first time banks have said they would pass on higher costs to consumers when regulators have attempted to cap their fees. In 2010, after the post-financial crisis overhaul of bank regulations, lenders warned that they would levy fees on debit cards because of a cap on some card charges—but few ended up doing so because consumers threatened to move their business. Some consumer advocates say this time is no different.

“The banks say that their only option is to pass on their costs to customers, but that’s not true,” said Dennis Kelleher, president of Better Markets, an economics think tank that is in favor of the proposed bank regulations. “Yet again, banks are dressing up their attempts to maximize their own profit under the guise of what’s good or bad for customers.”

Banks are saying this time could be different because of the scale of new financial regulations coming out of Washington. Agencies such as the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau are proposing an $8 cap on credit-card late payment fees and a $3 cap for overdrafting bank accounts.

It is possible some of the rules could be watered down, or not become law at all, if Donald Trump takes the White House in November. But as the landscape looks right now, Lake said many of the types of basic services that Chase customers have become accustomed to—including free checking accounts, credit score trackers, and financial planning tools—won’t likely be free anymore.

Long considered one of two front-runners to succeed Jamie Dimon as chief executive when he retires, Lake has worked in many parts of JPMorgan Chase. She served as chief financial officer between 2013 and 2019, and controller for its investment bank between 2007 and 2009.

She said she has seen how regulation of debit card swipe fees has made some banking services more expensive for customers, and she expects that to happen again.

“It is not practical for many of the services to be free if we won’t be able to draw from those profit pools,” Lake said.

Banks across the board have launched a number of appeals and taken the government to court to stop the raft of forthcoming rules. Most of the lawsuits have been filed in the Northern District of Texas, a favorite jurisdiction of institutions trying to stop rules and regulations promulgated by the Biden administration.

The rule capping credit card late fees was passed by the CFPB in March, but then a coalition of bank industry groups sued to stop it before it could become law. The law is pending appeal before a judge.

Trade organizations representing large banks also sued to prevent changes to the Community Reinvestment Act, which requires banks to offer their services to low-income and historically disadvantaged communities.

Even though the credit card late fee cap hasn’t become law yet, some credit-card companies are ready to pass on costs to customers. Chase has sketched out plans to ratchet up interest rates and take a more conservative approach to underwriting credit-card loans, according to an investor presentation.

In the long run, big banks such as Chase might actually stand to be the winners if the rules out of Washington are passed.

“Any change in regulations that would cap fees will create opportunities for institutions that are highly efficient,” said Dan Goerlich, a consulting partner at PricewaterhouseCoopers who advises bank clients.

“Big banks can make up for a dent in consumer banking revenues with profit from their wealth management and investment banking arms. Smaller and regional banks will struggle to make up for that.”

But he warned that it might not be so easy for banks to pass on costs, either.

The highly competitive environment for retail deposits means that banks might wind up needing to keep services free, no matter what the final rules end up looking like.

“Most customers can access retail banking easily and seamlessly today,” Goerlich said. “It might be disadvantageous to keep services at zero cost, but banks’ hands could be forced by other competitors who will offer customers low-cost services.”

Updated: 7-15-2024

Goldman Sachs Forced To Curb Buybacks After Stress Test Reveals It Needs To Set Aside More Capital

Goldman Sachs Group Inc. plans to cut down on stock repurchases after the Federal Reserve’s annual stress test required it to set aside more capital. The bank again pushed back against the results.