Wells Fargo, A Legal, Government-sanctioned Criminal Enterprise (#GotBitcoin)

This is a personal accounting of what’s happening with me at Wells Fargo Criminal Enterprise And Banking… Wells Fargo, A Legal, Government-sanctioned Criminal Enterprise (#GotBitcoin)

Related:

Wells Fargo Paid Colleges To Aggressively Market Products To Students Pushing Them Into Debt

Wells Fargo CEO Tim Sloan Steps Down

Executive Office: 866 218-1927

Case# 507-3741

Case Manager: Berto, Ramon, Kelly, Garret, Carlos, Ana, (Opened: 3-16-2019)

Personal Line of Credit: Opened 3-15-2019

It was supposed to have the ability to be used like an account that would allow automatic debiting (using and routing and account number), just like a checking or savings account.

However, after signing-up and going to my local branch to sign the paperwork, I was told that this product could not be used in the manner that I required.

Even though I spent an hour and 9 minutes (3-15-2019) on the phone with the rep. detailing and reviewing my requirements.

I was still told over the phone that it would indeed meet my requirements.

Now I’m finding out (3-28-2019) that no one at Wells Fargo Criminal Enterprise And Banking including Berto (Case Manager), Ramon, Kelly, Garret, Carlos and Ana, is able to address and/or resolve the

issue.

I have been persuaded to sign-up for something like the millions of people that we read about in the media including all of the other cases (up-selling of products, over-sold products such as car insurance, etc.) that have had accounts opened in their names without permission.

No one at Wells Fargo Criminal Enterprise And Banking (Berto, Ramon, Kelly, Garret, Carlos, Ana) or anyone else is taking responsibility or being held accountable for addressing this issue.

My call logs into Wells Fargo Criminal Enterprise And Banking with (Berto, Ramon, Kelly, Garret, Carlos, Ana) are both lengthy and detailed and there is absolutely no reason why the CFPB, the SEC. FINRA or any State regulators should not have ample reason to shut this sham and Ponzi-scheme down yesterday!!

This @WellsFargo fraudulent account scam destroyed my life and they got away with it. https://t.co/4QdFMYQV5C— Wells Fargo Fraud (@WFB_Fraud) June 19, 2017

Updated 4-6-2019

Subject: Re: Fee or service charge questions (KMM71910599V3148L0KM)From:Customer Service04/05/2019 06:19 AMContact UsDear Monty Henry:

Thank you for contacting Wells Fargo. My name is Aruna, and it’s my

pleasure to assist you today. I am an Email Care Specialist and your

concerns have been escalated to me for review.

I received your email about case number 235229593.

I forwarded this information to our Executive Office.

We’ll continue to work diligently to resolve this issue quickly.

Thank you for your business. We’re happy to have you as our customer.

Sincerely,

Aruna S.

Wells Fargo

ORIGINAL MESSAGE:

—————–

I was sold the wrong product and I just cancelled it. Also, the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau is looking into this. Please waive this 04/01/19 ANNUAL FEE FOR 04/19 THROUGH 03/20 $25.00

Thanks,

Monty b57d2217-5413-420e-b08f-3364c6852e86

Updated 3-29-2019

Subject: Re: Account questions or requests (KMM71775871V66169L0KM) From: Customer Service 03/29/2019 09:55 AM Contact Us

Dear Monty Henry:

Thank you for contacting Wells Fargo. My name is Caroline, and it’s my

pleasure to assist you today.

I received your email about your Personal Line of Credit account.

I appreciate the time you’ve taken to email us and bring this matter to

our attention.

Because of the nature of the situation and the feedback you provided,

I’ve forwarded your concerns to our Executive Office. Your case

reference number is 235229593.

A representative from our Executive Office will contact you within two

business days at phone number 818-298-3292.

If you’d prefer to speak with our Executive Office immediately, or if at

any time you’d like information regarding your case, you can call us at

1-877-224-5356. We’re available Monday through Friday from 6:00 am to

6:00 pm, Pacific Time.

Please provide the case number above when you call.

We look forward to speaking with you soon.

Thank you for your business. We’re happy to have you as our customer.

Sincerely,

Caroline N.

Wells Fargo

More To follow.

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau:

Your complaint has been sent to the company.

We’ve sent your complaint to the company for a response.

We will let you know when the company responds. The response should include the steps they took, or will take, in response to your complaint.

You should receive a status update within the next 15 days.

COMPLAINT ID

190329-3948212

SUBMITTED ON

03/29/2019

PRODUCT

Payday loan, title loan, or personal loan

ISSUE: Line of credit

The CFPB is an independent federal agency built to protect consumers. We write and enforce rules that keep banks and other financial companies operating fairly. We also educate and empower consumers, helping them make more informed choices to achieve their financial goals.

Updated 4-15-2019

To The CFPB:

I appreciate the monetary compensation ($525.00).

However, it would be nice if they also apologized and admitted that they led me to believe that the product met my requirements.

How many customers have actually accepted this type of treatment by the banks without going through what I went through (taking their case to the CFPB)?

Their transcript should clearly indicate how our 1hr. and 9 minute conversation should have been crystal as to what I expected vs what I finally received.

These banks typically are never actually held accountable for admitting exactly what they are doing and apologizing for deceiving customers.

Updated Friday, Apr 19, 3:32 PM

Wells Fargo Sent My CFPB Complaint Status To The Wrong Person!!!!

Why am I receiving this from someone who you guys undoubtedly thought he was me?

“On Fri, Apr 19, 2019 at 3:32 PM Sean Clark prplestain@yahoo.com wrote:

Mr. Henry,

My name is Sean Clark. On 3/31/19 I filed a case against Wells Fargo with the CFPB because a banking error on their part caused damage to my business. My case CFPB Case # is 190331-3952967. On 4/12/19 I received a response to my case stating they required more time and then another email stating that they had closed my investigation with this letter attached.

The letter was the response to you and provide me with your email address, case number, details regarding your case and so forth. I have attached the letter for your review. I contacted the CFPB immediately and advised them of the situation. They in turn contacted Wells Fargo to advise them of their error and had the letter erased from my case.

I am not sure but I do believe that without your consent I should not have had this personal information sent to me or attached to my case information.

I felt it was necessary to contact you and let you know of this error.

If you have any additional questions please feel free to email me.

Sean”

I am not Sean and Sean is not Monty Henry.

Please respond to this asap.

Thanks,

Monty

This is insane. Now I have to follow-up with the Executive Office: (866) 907-9913 Case# 5200-934

Consumer Finance Protection Bureau:

ID FOR COMPLAINT SENT TO WELLS FARGO & COMPANY

190420-4007490

Updated 4-23-1019

Subject: Re: RE : Re: Other questions or requests (KMM72246019V84704L0KM)From:Customer Service04/23/2019 08:21 AMContact Us ear Monty Henry:

Thank you for contacting Wells Fargo. My name is Latoya, and it’s my

pleasure to assist you today.

I received your email about case number 235229593. I apologize that our

previous email did not correctly address your concerns.

I forwarded this information to our Executive Office.

We’ll continue to work diligently to resolve this issue quickly.

Thank you for your business. We’re happy to have you as our customer.

Sincerely,

Latoya T.

Wells Fargo

NEXT MESSAGE:

—————–

This issue has nothing to do with any credit card. What credit card are YOU referring to?

I HAD a “personal line of credit” ending in “774” that I subsequently cancelled.

Monty

—————————————————————

From : Customer Service

Sent : 04/21/2019 04:30 PM

Subject : Re: Other questions or requests (KMM72212789V78850L0KM)

Dear Monty Henry:

I received your email about your credit card account.

I’ve forwarded your email to our Credit Card Non-Fraud Claims department

for review.

If we need more information from you, we’ll contact you by phone or U.S.

mail.

Many disputes require written notification before we can pursue the

claim.

If you receive a dispute letter from us, it’s important that you

complete and return it promptly to preserve your billing rights.

The Credit Card Non-Fraud Claims department doesn’t correspond through

email.

If you’d like to speak with us about the dispute process or to receive

an update on the dispute, please call us at 1-800-390-0533. We’re

available daily from 6:00 am to 11:00 pm, Central Time.

For more information about your billing rights, please refer to the back

of your monthly billing statement or your Customer Agreement and

Disclosure Statement.

My goal today was to provide you a complete and helpful answer. Thank

you for banking with Wells Fargo.

Sincerely,

Liberty P.

Wells Fargo Card Services

Wells Fargo is dedicated to protecting your information. To learn about

our security measures and what we do to protect your accounts online, go

to wellsfargo.com/privacy_security/fraud/

Updated 4-24-2019

Executive Office: (866) 907-9913

Justin Bell (866) 218–1922

(208) 297-7264 (Fax# (Doesn’t Even Work. No Actual Fax Tone!!)

Case# 5200-934

Monty, Owner DPL-Surveillance-Equipment.com

Updated: 11-4-2022

Wells Fargo Faces US Demand For Record Fine Exceeding $1 Billion (#GotBitcoin)

* CFPB Stance Is Said To Reflect Frustration With Repeat Abuses

* Firm Previously Said It’s In Talks To Settle Variety Of Probes

Wells Fargo & Co. is under pressure from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to pay more than $1 billion to settle a series of investigations into mistreatment of customers, a deal that would shatter the agency’s previous record — also with Wells Fargo.

The regulator’s demand in confidential talks, described by people with direct knowledge of the matter, reflects its escalating frustration with the bank, which has been punished multiple times by authorities over the past six years for a variety of past abuses.

In March, CFPB Director Rohit Chopra vowed to ratchet up sanctions on large, repeat offenders, potentially even limiting their ability to engage in certain businesses.

The latest talks with the CFPB span automobile lending, consumer-deposit accounts and mortgage lending, Wells Fargo said in a filing this week, without gauging the size of the potential payment.

The bank set aside $2 billion in the third quarter to cover a variety of regulatory and legal issues, including making harmed customers whole. The figures discussed by negotiators in the CFPB talks are around $1 billion, the people said.

Spokespeople for the regulator and bank declined to comment.

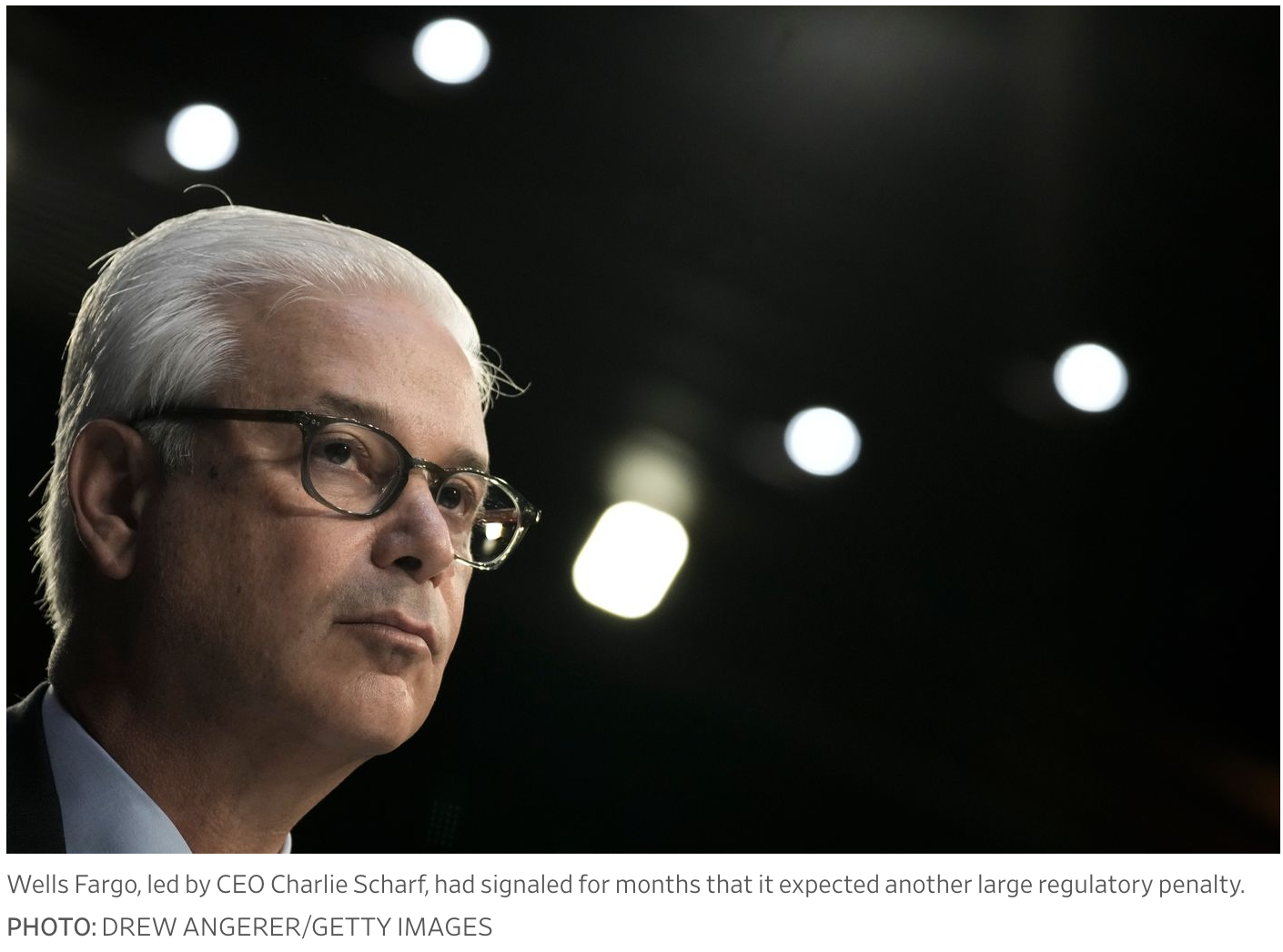

Under Chief Executive Officer Charlie Scharf, Wells Fargo has been trying to resolve a slew of scandals that erupted in 2016 with the revelation that the bank opened millions of bogus accounts.

Problems surfaced across business lines, resulting in the ousters of two CEOs and a number of costly penalties including the Federal Reserve’s decision to cap the bank’s assets. Scharf warned in October that the charge in the third quarter “isn’t the end of it.”

An accord with the CFPB isn’t imminent, nor is one likely to be announced this month, the people said, asking not to be named because the discussions are private.

Chopra has vowed to make punishments of large firms more painful, and the agency may ultimately seek restrictions on the bank’s businesses or other changes in addition to a financial penalty, some of the people said.

Wells Fargo aims to resolve as many of the agency’s concerns simultaneously as possible, which could offer some relief to shareholders. The talks could also stall.

The CFPB’s punishments of the bank have been notching higher for years.

In 2016, the agency fined the firm $100 million for opening accounts without customers’ permission. In 2018, the agency imposed a $1 billion sanction for additional misconduct, but gave the bank a $500 million credit for a concurrent settlement with the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

Measured against the portion that the CFPB collected, a sanction surpassing $1 billion would more than double the old amount — though the agency would probably use $1 billion as the prior benchmark.

Chopra, appointed by President Joe Biden, is under pressure from progressives in the Democratic party to reinvigorate the consumer watchdog, which they say pulled back from tougher policy making and enforcement under Republican President Donald Trump.

“Corporate recidivism has become normalized and calculated as the cost of doing business,” Chopra said in March. “We must forcefully address repeat lawbreakers to alter company behavior and ensure companies realize it is cheaper, and better for their bottom line, to obey the law than to break it.”

Updated: 12-20-2022

Wells Fargo To Pay Record CFPB Fine To Settle Allegations It Harmed Customers

Bank’s settlement includes a $1.7 billion penalty, the consumer agency’s largest ever.

Wells Fargo & Co. reached a $3.7 billion deal with regulators to resolve allegations that it harmed more than 16 million people with deposit accounts, auto loans and mortgages.

The settlement with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau includes a $1.7 billion penalty, the agency’s largest-ever fine, and more than $2 billion in consumer restitution, the regulator said Tuesday.

The consumer watchdog agency said the bank illegally assessed fees and interest charges on loans for cars and homes. Some consumers had their vehicles illegally repossessed while others had overdraft fees unlawfully applied, the agency said.

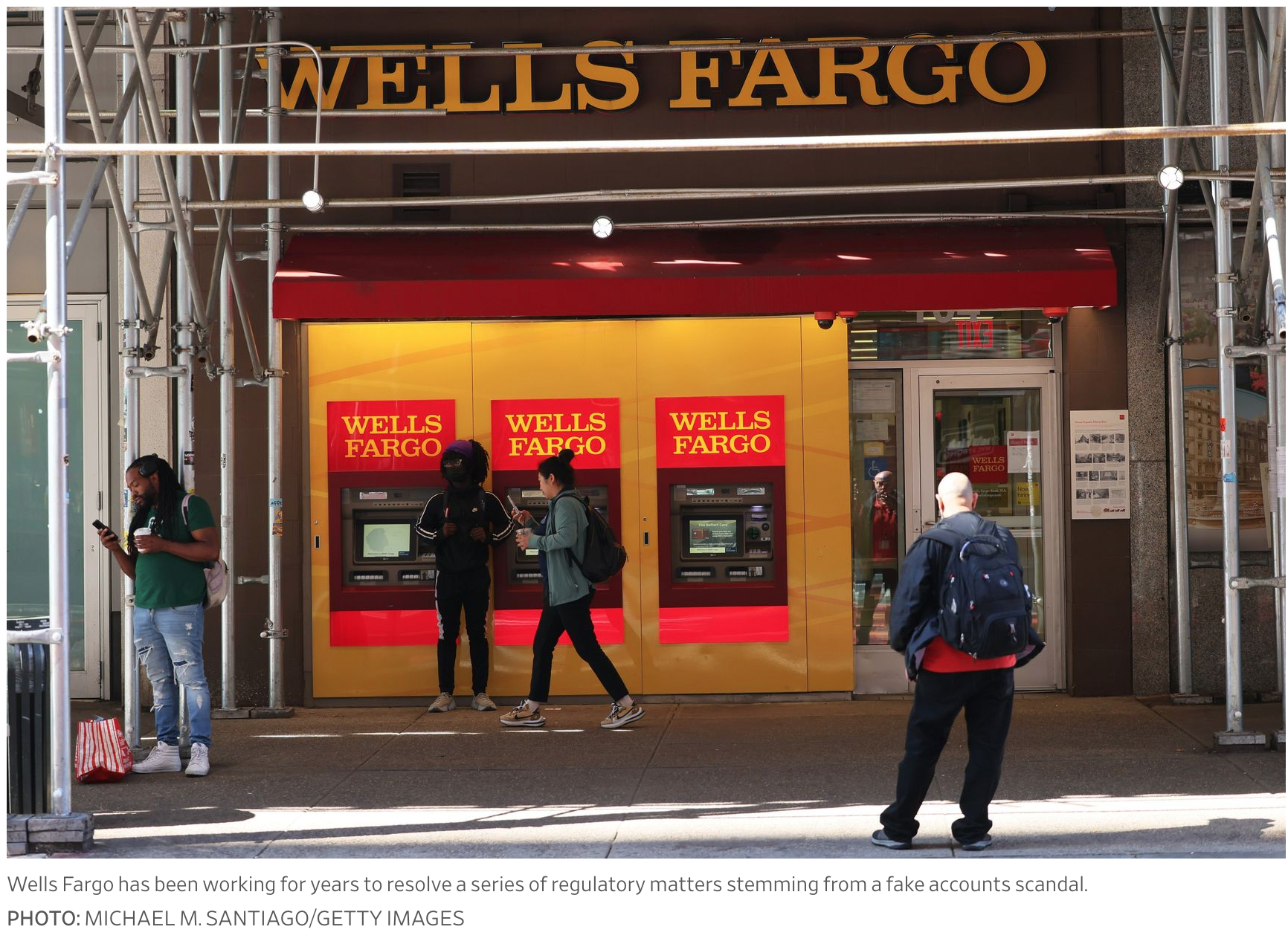

Wells Fargo’s regulatory troubles continue to ripple through the bank more than six years after its fake account scandal burst into public view. Other problems later surfaced across the San Francisco-based bank, including in its lending and deposit-taking businesses.

The CFPB settlement resolves a major penalty hanging over Wells Fargo but leaves it handcuffed by other regulators. The Federal Reserve has had a cap on the bank’s asset growth in place for nearly five years. Politicians continue to target the bank, and investors have filed a series of class-action lawsuits.

“Wells Fargo is a corporate recidivist,” said CFPB Director Rohit Chopra, on a call with reporters Tuesday. He said the settlement “should not be read as a sign that Wells Fargo has moved past its longstanding problems.”

The bank had been negotiating with the CFPB for months in an effort to lump as many outstanding issues into the settlement as possible, according to people familiar with the matter.

Much of the $2 billion remediation included in the settlement has already been doled out to customers. The bank, for example, has paid $1.3 billion to 11 million customers who had auto-loan servicing issues, the CFPB said.

Wells Fargo has been working for years to resolve a series of regulatory matters stemming from a fake-accounts scandal in 2016. Afterward, other problems surfaced across the bank, including in its mortgage and auto-lending businesses.

The CFPB said the bank’s actions span over a decade. Wells Fargo incorrectly applied auto-loan payments because of technology and compliance failures from 2011 through 2022, the agency said. Errors in its home loan modification process went on from 2011 to 2018, the agency said.

The bank sometimes charged overdraft fees even when a customer had enough funds available to make a debit-card transaction or ATM withdrawal, CFPB said. Wells Fargo is required to refund customers about $205 million in fees since the beginning of last year that weren’t yet reversed. CFPB will oversee that process.

Mr. Chopra, an appointee of President Biden, has said he plans to target repeat offenders. “Corporate recidivism has become normalized and calculated as the cost of doing business,” he said in a speech earlier this year. He has also sought to make his agency more adversarial toward financial firms.

The CFPB said Wells Fargo has accelerated efforts to clean up its act since 2020. Tied to the settlement, the agency will terminate one of the consent orders it had placed on the bank in 2016 and clarify that a 2018 consent order will terminate in no more than three years.

“This far-reaching agreement is an important milestone in our work to transform the operating practices at Wells Fargo and to put these issues behind us,” Chief Executive Charlie Scharf said in a statement.

Mr. Scharf was brought in to clean up the bank in 2019. He has overhauled the top executive ranks, cut its workforce and gave priority to remaking the bank’s back-end systems for managing internal controls and risk.

The bank had signaled for months that it expected another big regulatory penalty, and it took a $2 billion charge in the third quarter tied to resolving long-running legal and regulatory issues. The bank said Tuesday that it expects an operating losses expense of $3.5 billion in the current quarter.

Big US Banks Fall Short On Promises To Create Black Homeowners

Wells Fargo & Co., once the nation’s biggest home lender, has held mortgages on six houses on the block in recent decades, according to those records. Bank of America Corp. had five and JPMorgan Chase & Co. one.

Today, those banks are mostly a memory. The last Bank of America loan was paid off last year. There’s only one Wells Fargo mortgage left and one from JPMorgan — both to landlords.

The 2900 block of Walbrook Avenue in Baltimore is a study in contrasts. Row houses with tidy yards stand next to abandoned brick shells and rundown rental buildings.

Residents describe a dwindling community of working-class Black homeowners with ties going back generations. Property records tell another story, one about America’s racial wealth gap and the banks that walked away.

The exodus from Walbrook Avenue has been replicated across the country since the subprime mortgage crisis blew up the financial system more than a decade ago and a wave of foreclosures washed through cities like Baltimore.

And to this day it undercuts $120 billion of promises made by the largest banks to increase lending to Black homebuyers and help right one of the country’s great economic wrongs.

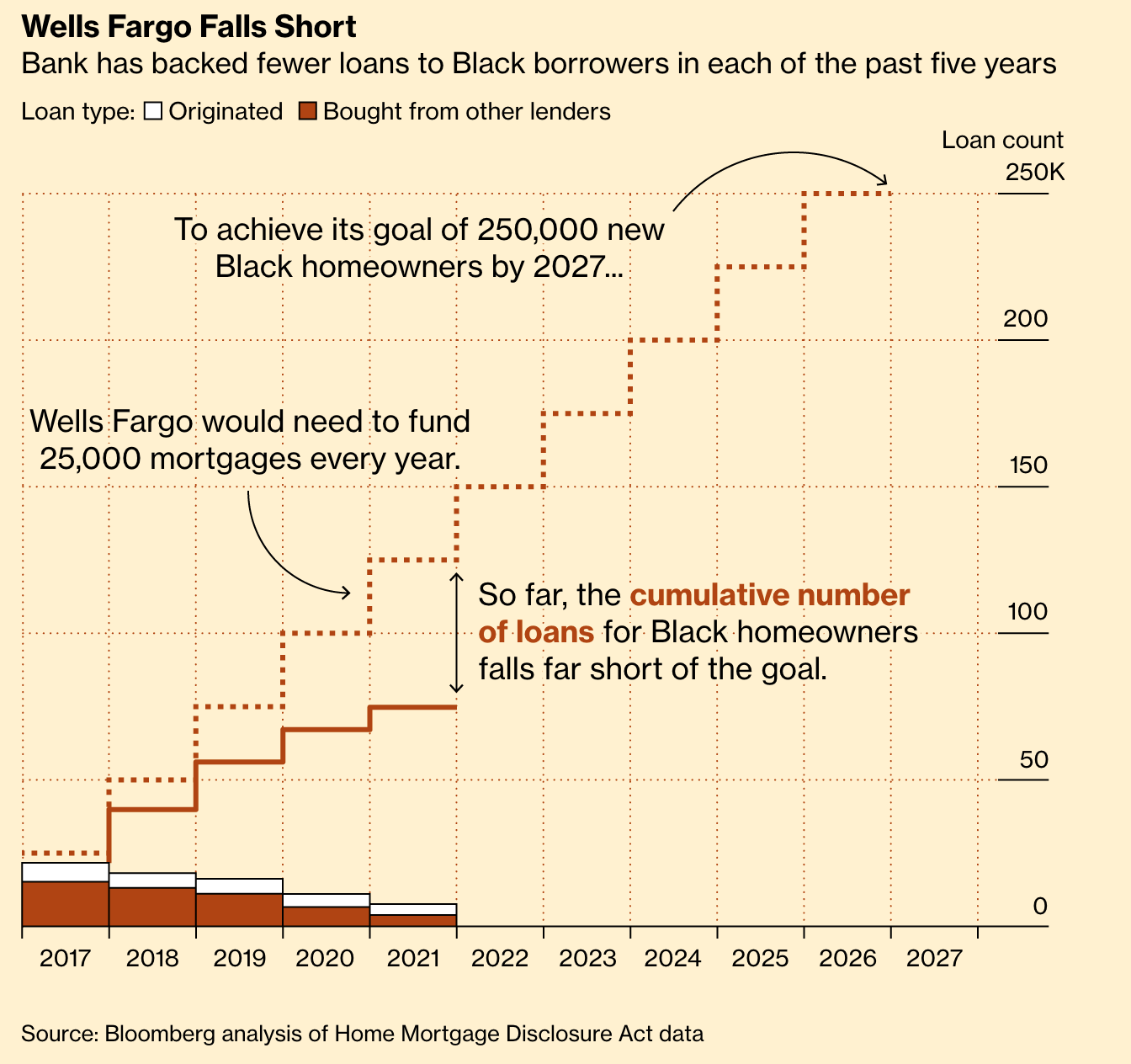

Wells Fargo, run by Tim Sloan at the time, made the boldest pledge in 2017, vowing to lend $60 billion to create 250,000 Black homeowners within a decade.

But last year, the San Francisco-based lender underwrote 42% fewer mortgages to Black buyers than in the year it announced its target, a Bloomberg News analysis of data covering more than 50 million mortgages over the past 15 years found.

Even counting mortgages purchased from other lenders, Wells Fargo has backed successively fewer loans in each of the past five years, hitting a 15-year low in 2021.

“That’s clearly going in the wrong direction,” says Brad Blackwell, the senior executive responsible for setting Wells Fargo’s 2017 goal, who retired from the bank the following year.

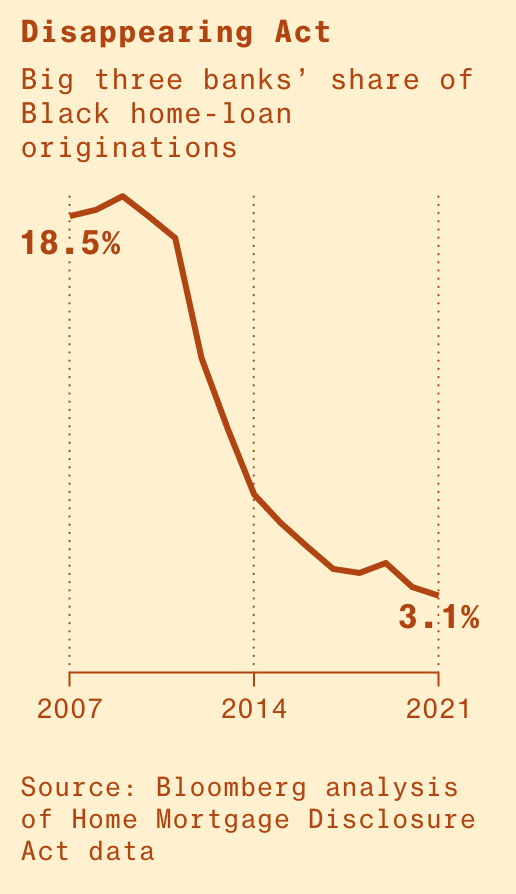

The pullback has affected borrowers of all races. In 2007, Wells Fargo, Bank of America and JPMorgan originated 19% of all US mortgages, Bloomberg found. By 2021, it was 4%.

In Baltimore, where a majority of the population is Black, the numbers are just as dramatic. Loans the three banks underwrote in predominantly Black neighborhoods fell to 1.2% of all mortgages in the city last year from about 10% in 2007.

Wells Fargo doesn’t dispute the decline in its lending to Black homebuyers since 2017. But it says its own calculations, which counted investment properties as well as owner-occupied homes, show the bank has backed more mortgages than the Bloomberg analysis. The bank didn’t respond directly to questions about how it plans to meet its pledge.

“Systemic inequities in the US have prevented minority families from achieving their homeownership and financial goals for too long,” Wells Fargo said in a statement. “Events and economic conditions of the last several years have further compounded the issue. Government and the private sector need to work together with community groups across the country to develop solutions that help address the gap.”

On Tuesday, the bank agreed to pay $3.7 billion to settle a variety of allegations made by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau over the mistreatment of customers, including the “widespread mismanagement” of auto loans, mortgages and deposit accounts.

JPMorgan, which in October 2020 pledged to create 40,000 new Black and Latino homeowners on top of what it was doing in 2019, has made only modest progress toward its goal. Last year it underwrote 122 additional mortgages for Black homebuyers, with the number of loans to Hispanic buyers actually falling.

Shannon O’Reilly, a spokeswoman for JPMorgan, says the bank remains committed to its goal, even though “market dynamics could affect the specific timing.” JPMorgan is expanding its presence in Baltimore, where it didn’t have a retail outpost until 2019.

This month it opened a branch not far from Walbrook Avenue, pitching the event as a sign of the bank’s commitment to the city’s Black communities. “If we don’t take a little bit of time to lift up all of our society, and we leave part of our society behind, we will all be worse off for that,’’ Chief Executive Officer Jamie Dimon said at a ribbon-cutting ceremony.

Bank of America has announced at least $30 billion in homeownership programs aimed at low-income and minority borrowers in recent years and said in August that it would offer zero-down mortgages in five cities.

The bank has almost doubled the number of mortgages it underwrote for Black buyers since 2017, but its lending to that group remains less than one-fifth of what it was in 2007.

The bank says it intends to meet its commitments. Increasing the Black homeownership rate “is a fundamental question that the industry is focused on,” says Matt Vernon, head of retail lending.

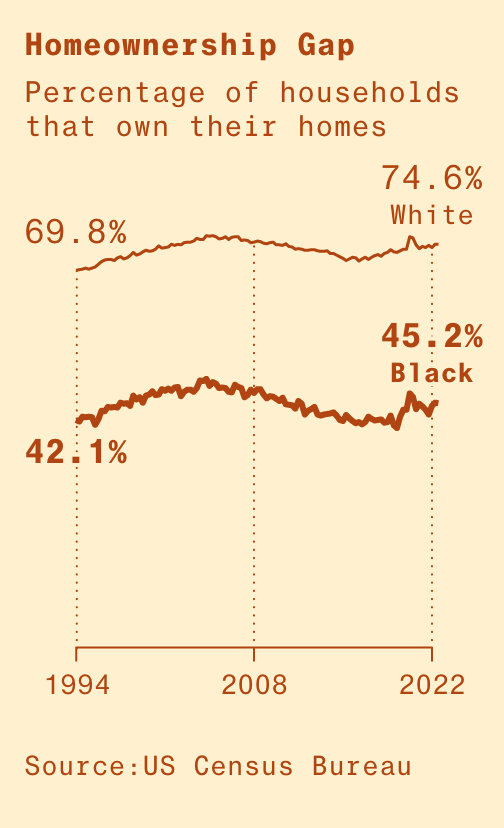

That rate remains stuck at about 45%, almost 30 points below that of White households — a gap that hasn’t changed much since the 1960s and that underpins the wealth divide.

The three banks have given millions of dollars in recent years to local and national housing groups working on increasing Black homeownership rates and have taken part in policy discussions in Washington. But those philanthropic efforts don’t match the trends in the lending data.

Bank executives put the blame for their diminished lending elsewhere: on increased capital requirements that reduce their capacity to lend, on regulations introduced after the financial crisis, on the billions of dollars in fines they paid for sloppy underwriting practices and on wider social problems that result in lower incomes and credit scores in Black communities.

Bloomberg reported earlier this year on racial disparities in Wells Fargo’s approval rates for homeowners seeking to refinance their mortgages during the pandemic to take advantage of historically low interest rates.

The new analysis of federal Home Mortgage Disclosure Act records released by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau focused on new mortgages, both those originated by banks and those bought from other lenders.

Mortgages for Black homebuyers plummeted by more than 60% — farther than those for borrowers of all other races — from 2007, when credit was easiest, to 2011, as big banks curbed their lending, the data show. Nonbank lenders such as Rocket Cos. eventually replaced them. But it wasn’t until 2020 that total loans to Black homebuyers exceeded 2007 levels.

Even with that surge, Black homebuyers in the first half of this year accounted for only 3% of purchases in the US, the National Association of Realtors reported in November. The banks’ promises will be harder to meet as the Federal Reserve’s battle with high inflation keeps mortgage rates near their highest in two decades, and home sales dwindle.

For many Black neighborhoods, the pullback was crushing, says Sean Closkey, president of Rebuild Metro, a housing group working to rehabilitate blighted Baltimore neighborhoods.

He says banks cut the “capital artery” to many communities. That it happened after a financial crisis they helped cause, he says, “that’s the smoking gun.”

Terrence Jones Jr. used to live at 2903 Walbrook. He remembers the surprise he got one afternoon in 2013 when he came home from school to find his mother waiting outside with grim news: They’d lost their house to the bank.

Jones’s father had fallen behind on the $65,000 mortgage he took out in 2003. He had cut his work hours to take care of his sick wife, and although she recovered, the family never caught up. “They just put us out,” says Jones, now 23. “They wouldn’t even let us get any of our stuff.”

Wells Fargo, which didn’t respond to questions about the Joneses, had bought the mortgage in 2012 from another lender and transferred the deed to foreclosure lawyers the following year.

The house was sold by the bank in 2016 for $500 to a Pennsylvania investor who flipped it for $9,000, property records show. It was refurbished and sold again for almost $90,000 last November.

Next door, at 2901, a house that was the subject of a Bank of America foreclosure is now a vacant shell. The mortgages on the block that pop up in property records in recent years are from nonbank lenders such as Rocket and Texas-based PrimeLending, which provided the loan used to buy the former Jones house last year. What you don’t see are new mortgages from big banks.

Rudy Miales, a retired longshoreman who has lived on the block since 1980 and paid off a Bank of America mortgage years ago, has watched families leave and a transient population of renters take their place. “All these people over here, they might not be here tomorrow,” Miales says, pointing to a cluster of rentals across the street.

The Joneses’ house was one of at least 3,000 Baltimore properties that Wells Fargo transferred to property lawyers, an initial step toward repossession, from 2012 through 2021, a Bloomberg review of public records found.

That was more than its peers, and more than the number of mortgages the bank originated for borrowers of all races in the city during that period.

About three-quarters of the properties Wells Fargo turned over to lawyers were in predominantly Black census tracts. Many of the mortgages, like the Joneses’, had been purchased from other lenders.

It isn’t clear how many people ended up losing their homes. But the arithmetic is clear: Subtractions by foreclosure matter as much as new loans when calculating ownership rates.

“It was a place that we could call home,” says Jones, who this month started working for Southwest Airlines at Baltimore/Washington International airport. It was also an asset that his parents, who now rent, could have passed on to him. “It definitely would’ve been nice to have them say one day that ‘You can have that house.’”

Jones says he’s down on the idea of getting a mortgage: “I don’t want to go through the same thing that my father went through, and my family went through, with losing the house.”

One reason the big banks extended fewer mortgages to Black homebuyers was their decision after the subprime crisis of 2007 to pull out of the market for Federal Housing Administration-backed home loans to low-income and first-time buyers.

That withdrawal followed a decision by federal regulators to use the Civil War-era False Claims Act to levy billions of dollars in fines against banks for loans that went bad.

“Why would a bank make an FHA loan when the False Claims Act can still be used to second-guess everything they’ve done in a down economy and cost them billions and billions of dollars more?” says David Dworkin, a former housing policy adviser at the US Treasury who leads the National Housing Conference, a group that works with lenders and advocacy and civil rights groups.

There were other reasons for the pullback beyond FHA loans, which account for less than 10% of the market. The industry’s reliance on commissions, making the sale of high-value “jumbo” mortgages in affluent White suburbs more profitable, hasn’t helped encourage lending into Black communities, Dworkin says.

And there are issues, he says, with how young Black Americans like Jones became disillusioned with the idea of buying a home.

Bank executives say comparisons to 2007 are unfair and that regulation has fundamentally changed the mortgage business. Nonbank lenders, which they say face fewer restrictions, account for a larger share of the market, especially for low-income buyers.

Rocket, now the biggest originator in the US, issued 12,029 mortgages to Black homebuyers in 2021, almost twice as many as the previous year and more than the three banks combined.

Rocket hasn’t announced any Black homeownership goals, but the company says it’s subject to the same fair-housing laws as traditional lenders. “We believe actions speak louder than words, and as our results indicate, we are making progress every day to help close the racial homeownership gap,” says Aaron Emerson, a Rocket spokesman.

The surge in online mortgage lending helped push up the Black homeownership rate last year to 45%, from a low of 41% in 2019. But that progress is unlikely to be sustained if interest rates remain high. In the first half of 2022, Rocket reported originating mortgages worth almost $100 billion less than in the same period last year.

While increased nonbank lending to Black homebuyers has been welcome, big banks have a responsibility to stay involved, says Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, who oversees policy and equity programs at the Washington-based National Community Reinvestment Coalition.

“They have a higher obligation to do this type of lending,” he says, “and they’re failing in a way that the nonbank institutions aren’t.”

Asante-Muhammad led an NCRC study that found boosting the Black homeownership rate to 60% over 20 years would require 165,000 mortgages a year above the 2019 level.

“We really need radical change to not even get to equality, but just to get to substantive majority Black homeownership,’’ he says.

To get there, some policymakers have called for rooting out systemic bias in appraisals and credit scores, or modifying the 1977 Community Reinvestment Act to target loans by race rather than income.

But closing the gap is also about volume: The number of first-time Black buyers needs to grow faster than the population. And that hasn’t been happening.

“We keep climbing a down escalator that moves faster and faster,” says Dworkin, whose National Housing Conference leads a campaign, endorsed by Bank of America, JPMorgan and Wells Fargo, to help create 3 million new Black homeowners by 2030.

No one wants a return to shady lending practices that led to the subprime crisis, but meeting that goal would require surpassing 2007 levels for many years to come.

Yet Wells Fargo, JPMorgan and Bank of America signed off on 44,000 fewer mortgages for Black buyers in 2021 than in 2007, housing data show. Their share of home loans originated for Black borrowers over the past five years has remained flat at about 3%.

When Wells Fargo set its 2017 goal, it knew it couldn’t rely on FHA mortgages, says Blackwell, who spent 17 years at the bank, ending up as executive vice president of housing policy and homeownership growth strategies.

The strategy, he says, was to buy and originate more conventional mortgages for Black buyers, partly by recruiting more Black loan officers. But, he says, the recruiting effort struggled.

The pledge was made before Charlie Scharf was brought in as CEO in 2019 to clean up a series of scandals. He has abandoned the bank’s long-time aim to be the biggest US home lender and plans further cuts to the business, Bloomberg reported earlier this year.

But Scharf told lawmakers in September that Wells Fargo is committed to working “within communities of color or those which are more racially and ethnically diverse.”

Blackwell says it’s hard to see the bank meeting its promises, particularly with the property market slowing. “When that happens,” he says, “the harder areas to lend are the first to suffer.”

Nneamaka Odum, a 29-year-old Internal Revenue Service officer, offers one example of how banks can help create new Black homeowners.

Odum had only $6,000 in savings when she went searching for a home in 2019. But in March 2020, as pandemic lockdowns began, she closed on a $137,000 five-bedroom house in Baltimore’s Waverly neighborhood.

“I didn’t have to pay a cent at closing,” she says. She got $29,000 in forgivable loans to cover her down payment and closing costs, $15,000 of which came from a Wells Fargo-backed program called NeighborhoodLIFT.

The program began after the bank agreed to provide at least $50 million in down-payment assistance in Baltimore and seven other cities as part of a 2012 settlement with the US Justice Department.

Federal officials alleged that Wells Fargo had targeted minority communities with high-interest subprime mortgages and wrongly foreclosed on them — allegations the bank denied. Ultimately, the bank put more than $10 million into Baltimore through the program.

Lenders, policymakers and housing groups all say down-payment assistance is an effective way to boost Black homeownership, and all three big banks have such programs. But the loans haven’t always reached minority neighborhoods. One reason: Programs were often based on income, not race.

A Bloomberg review of Baltimore property records found that only 61% of the 682 recipients of Wells Fargo’s down-payment assistance from 2013 through 2021 bought homes in majority-Black census tracts.

Some of those borrowers could have been White or Hispanic, and the review didn’t account for Black borrowers who bought homes in majority-White census tracts.

Neither Wells Fargo nor Neighborhood Housing Services of Baltimore, a nonprofit group that administered the program, would provide a racial breakdown of recipients over the past decade.

A spokesperson for NeighborWorks America, which oversees the national effort, did say that 32% of its down-payment assistance since 2019 has gone to Black homeowners.

Recent efforts have been focused on rural areas and states with low Black populations, the spokesperson says.

Bank of America says it has provided down-payment and closing assistance to 38,000 buyers nationwide, two-thirds of them “multicultural.” The bank wouldn’t provide any further breakdown.

Despite years of neglect, there’s still hope on the 2900 block of Walbrook. Much of it rests in the hands of Neighborhood Housing Services of Baltimore, which became a mortgage originator to help clients struggling to get loans.

The group has adopted the block, part of a five-by-seven-block area where it plans to invest as much as $30 million, mostly drawn from federal funds, to renovate about 100 vacant properties. The goal, says Executive Director Dan Ellis, is to restore roughly $100 million in wealth by lifting home prices and attracting new Black owners.

Sometimes the economics of projects can seem irrational. NHS bought 2935 Walbrook for $47,500 and plans to spend $188,000 renovating it. Add closing costs and sundries, and it is at least a $250,000 project, Ellis says.

A similar NHS-renovated property on the next block sold for more than $200,000 last summer, so this one is likely to show a loss.

But, Ellis says, ignore the story of a single house, restore the market, and eventually the economics will make sense. You create a new comparison point for appraisers. Lenders once spooked by vacant properties will reengage.

Big banks are backing such projects. JPMorgan earlier this year gave a $2 million grant to another Baltimore housing nonprofit that does similar work. Wells Fargo has announced a series of grants for community groups around the country.

Too often, though, Ellis and others doing the work say, getting the capital to rehabilitate homes depends on philanthropic groups willing to take a risk to close the wealth gap. “That’s why we do it,” says Ellis. “Because no one else will.”

Wells Fargo’s Problems Are Far From Over Even After Record $3.7 Billion Settlement

* CFPB Says Consent Order Doesn’t Mean The Agency’s Work Is Done

* Bank To Book $3.5 Billion In Litigation, Remediation Costs

Wells Fargo & Co. agreed to pay $3.7 billion to settle allegations that for years it mistreated millions of customers, causing some to lose their cars or homes. That record-setting amount still doesn’t mean the bank’s problems are over.

The head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau vowed that his agency might put further limitations on the bank. And the company itself warned it will have to set aside billions more in the fourth quarter to cover not only Tuesday’s settlement but other litigation as well.

“While today’s order addresses a number of consumer abuses, it should not be read as a sign that Wells Fargo has moved past its longstanding problems or that the CFPB’s work here is done,” Rohit Chopra, the agency’s director, said on a call with journalists. “Importantly, the order does not provide immunity for any individuals, nor, for example, does it release claims for any ongoing illegal acts or practices.”

Tuesday’s agreement with the CFPB includes more than $2 billion in redress for customers, with the agency saying it found “widespread mismanagement” of auto loans, mortgages and deposit accounts.

Taken together, the episodes chronicle an extraordinary 11-year period of illegal activity and mismanagement at one of the nation’s largest banks.

“We remain committed to doing the right thing for our customers and working closely with our regulators and others to deal appropriately with any issue that arises,” Chief Executive Officer Charlie Scharf said in a statement. “This far-reaching agreement is an important milestone in our work.”

Consumer Harm

According to the CFPB, Wells Fargo illegally repossessed vehicles, bungled record-keeping on payments and improperly charged fees and interest. The bank agreed to a consent order without admitting the agency’s allegations.

The CFPB found some of the bank’s misdeeds continued until earlier this year. Take its auto loan servicing business: Wells Fargo repossessed vehicles even if a borrower had made a payment or entered into an agreement with the bank to stall the action, according to the agency. In all, customers affected by conduct in the car-loan business will receive more than $1.3 billion in redress.

The problems didn’t stop there. In the mortgage business, Wells Fargo erroneously identified some 190 customers as dead, and therefore didn’t assess whether they were eligible to modify a government-backed loan in the five years leading up to 2018. The bank agreed to pay those borrowers $2.4 million, or an average of $12,631 per person.

Wells Fargo also illegally charged surprise overdraft fees, and in more than 1 million cases, it unlawfully froze consumer accounts “based on a faulty automated filter’s determination” that there may have been a fraudulent deposit.

“The bank’s illegal conduct led to billions of dollars in financial harm to its customers and, for thousands of customers, the loss of their vehicles and homes,” Chopra said. “We see this as an initial step to bring relief quickly to families who had their cars illegally possessed, who were tricked into seeing their accounts drained by illegal junk fees, and who had their accounts frozen without cause.”

More Charges

Under Scharf, Wells Fargo has been trying to resolve a raft of scandals that emerged in 2016 with the revelation that the bank opened millions of bogus accounts. Problems surfaced across business lines, resulting in the departure of two previous CEOs and a number of costly penalties, including the Federal Reserve’s decision to cap the San Francisco-based firm’s assets.

Securing Tuesday’s agreement actually marks a win for Scharf, who joined the firm in 2019 and has sought to move quickly to resolve the bevy of problems that have plagued the company. Scharf has long distanced himself from the actions of his predecessors, who oversaw much of the conduct described in this week’s settlement.

Still, Wells Fargo said it expects a pretax operating loss expense of about $3.5 billion in the fourth quarter, which it said includes the CFPB civil penalty and remediation, as well as other litigation expenses. The move comes after Wells Fargo already set aside $2.2 billion for similar matters in the third quarter.

“This sizable fourth-quarter number also means that Wells Fargo has been booking losses for other actions along the way that are still open-ended,” Ken Usdin, an analyst at Jefferies Financial Group Inc., said in a note to clients. “We do not see today’s action as having a direct read-though to the asset cap and its potential removal.”

The bank’s shares slipped 1.4% to $41.25 at 12:42 p.m. in New York, the worst performer in the 24-company KBW Bank Index.

Chopra Warning

In prepared remarks Tuesday, Chopra said he’s grown increasingly concerned that Wells Fargo’s recent efforts to boost profitability — through product launches and other growth initiatives — has delayed necessary reforms across the bank.

The director said federal banking regulators will have to consider whether further limitations must be placed on the bank in addition to the Fed’s asset cap and a move last year by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

The OCC limited Wells Fargo’s ability to acquire new mortgage-servicing business and required the bank ensure borrowers aren’t transferred out of its loan-servicing portfolio until remediation is provided.

“Our nation’s banking laws provide strong tools to ensure that insured depository institutions do not breach the public trust, and in the new year we expect to work with our fellow regulators on whether and how to use them,” Chopra said.

Updated: 5-18-2023

Wells Fargo To Pay $1B In Shareholders Lawsuit Settlement

A Redditor highlighted the recurring violations of regulations by banks, expressing their frustration at the relatively muted response from the SEC.

Financial services firm Wells Fargo has reached a settlement in a class-action lawsuit, agreeing to pay shareholders $1 billion.

The lawsuit alleged that the bank had misled its shareholders about its efforts to resolve the 2016 fake accounts scandal.

A $1 billion all-cash settlement was granted preliminary approval by United States district judge Gregory Woods in a Manhattan federal court. Another hearing will be held on Sept. 8 for final approval.

In a statement, the bank said it disagreed with the allegations made in the lawsuit. On the other hand, while it disagrees with the accusations, it is “pleased to have resolved this matter.”

In December 2022, Wells Fargo also reached a $3.7 billion agreement with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to resolve allegations that the bank’s actions had harmed more than 16 million individuals with deposit accounts, auto loans and mortgages.

At the time, Ripple CEO Brad Garlinghouse compared the Wells Fargo issue with the FTX collapse. According to Garlinghouse, the world was outraged by FTX, which he believed to be “appropriate.”

However, the CEO expressed his concern about the lack of attention to the Wells Fargo case, considering that it also “mismanaged billions in customer funds.”

Members of the community recently voiced similar concerns on a recent Reddit forum. On May 17, one Redditor said that the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission should also look into banks. They wrote:

“People put their hard-earned money in a bank thinking it is 100% safe, take loans for house and cars only to be scammed out of it.”

The community member also argued that banks had violated regulations multiple times every single year, but “the SEC has stayed rather quiet” about it. Another Redditor echoed the sentiment, saying it’s “obvious the banks get a pass for the most part.”

Related Articles:

Trump Administration’s ‘Plunge Protection Team’ Convened Amid Wall Street Rout (#GotBitcoin?)

Probes Reveal Central, US-Based, International Banks All Have Sticky Fingers (#GotBitcoin?)

Major Banks Suspected Of Collusion In Bond-Rigging Probe (#GotBitcoin?)

Some Merrill Brokers Say Pay Plan Urges More Customer Debt (#GotBitcoin?)

Deutsche Bank Handled $150 Billion of Potentially Suspicious Flows Tied To Danske (#GotBitcoin?)

Wall Street Fines Rose in 2018, Boosted By Foreign Bribery Cases (#GotBitcoin?)

U.S. Market-Manipulation Cases Reach Record (#GotBitcoin?)

Poll: We Should Get Rid of The Federal Reserve And Central Banks Because:

Your Questions And Comments Are Greatly Appreciated.

Monty H. & Carolyn A.

Go back

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.