Ultimate Resource For Money Laundering, Spoofing, Market-Rigging, Etc. In Banking Industry (#GotBitcoin)

Bank of America To Pay $30 Million In Benchmark-Manipulation Settlement. Ultimate Resource For Money Laundering, Spoofing, Market-Rigging, Etc. In Banking Industry (#GotBitcoin)

The bank was accused of trying to help its own derivatives positions.

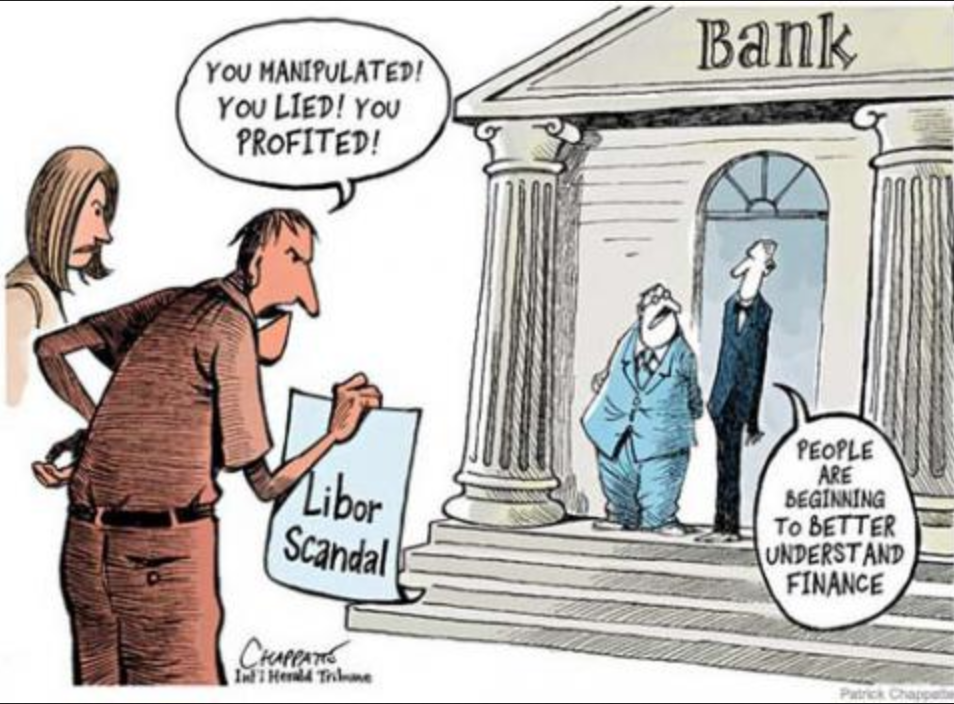

Bank of America Corp. will pay $30 million as part of a settlement with the Commodity Futures Trading Commission related to charges that the bank tried to manipulate a benchmark for interest-rate products over a span of six years.

The CFTC said Wednesday that Bank of America tried to manipulate the U.S. Dollar International Swaps and Derivatives Association Fix, or ISDAfix, to help its own derivatives positions. It also accused the bank of false reporting.

Bank of America traders, according to the futures regulator, attempted to manipulate rates to benefit specific trading positions and influence reference rates and spreads ahead of the time the final rates were published.

Related:

Morgan Stanley To Pay $10M For Anti-Money Laundering Failures (#GotBitcoin?)

JPMorgan To Pay $290 Million to Settle Jeffrey Epstein Accusers’ Suit

JP Morgan’s (Jamie Dimon’s) Total Fines/Settlements ($35 Billion And Counting)

Europe Goes Harder on Money Laundering With Record ING Fine (#GotBitcoin?)

Money-Laundering Is Completely Out-Of-Control In Traditional Finance/Banking Industry (#GotBitcoin?)

France Moves To Ban Anonymous Crypto Accounts To Prevent Money Laundering

The Money Laundering Hub On the U.S. Border? It’s Canada! (#GotBitcoin)

SEC And DOJ Charges Lobbying Kingpin Jack Abramoff And Associate For Money Laundering

CFTC Director of Enforcement James McDonald said in prepared remarks that the regulator’s settlement with the bank is its ninth enforcement action tied to manipulation with this benchmark. On Tuesday, the CFTC announced that Intercapital Markets LLC would pay $50 million as part of a settlement with the regulator.

“We have significantly enhanced our procedures to detect any inappropriate behavior,” a Bank of America spokesman said.

Updated: 1-13-2021

Christine Lagarde Convicted: IMF Head Found Guilty Of Criminal Charges Over Massive Government Payout

But former French finance minister, who faced potentially one year in jail, will not face any punishment.

International Monetary Fund chief Christine Lagarde has been convicted over her role in a controversial €400m (£355m) payment to a businessman.

French judges found Ms Lagarde guilty of negligence for failing to challenge the state arbitration payout to the friend of former French President Nicolas Sarkozy.

The 60-year-old, following a week-long trial in Paris, was not given any sentence and will not be punished.

The Court of Justice of the Republic, a special tribunal for ministers, could have given Ms Lagarde up to one-year in prison and a €13,000 fine.

The ruling, however, risks triggering a new leadership crisis at the IMF after Ms Lagarde’s predecessor Dominique Strauss-Kahn resigned in 2011 over a sex assault scandal.

Ms Lagarde, who was French finance minister at the time of the payment in 2008, has denied the negligence charges.

Her lawyer said immediately after the ruling that his team would look into appealing the decision.

On Friday she told the court: “These five days [of trial] put an end to a five-year ordeal for my partner, my sons, my brothers, who are here in this courtroom.

“In this case, like in all the other cases, I acted with trust and with a clear conscience with the only intention of defending the public interest.”

The case surrounded the decision to allow a dispute over Bernard Tapie’s sale of Adidas to Crédit Lyonnais bank to be resolved by a rarely-used private arbitration panel – instead of the courts.

Investigators suspected the payment to 73-year-old Mr Tapie was the result of a behind closed doors agreement with then-President Mr Sarkozy in return for election support.

IMF managing director Ms Lagarde was suspected of rubber stamping a deal to effectively buy off the business magnate with taxpayers’ money.

Civil courts have since quashed the unusually generous award, declared the arbitration process and deal fraudulent, and ordered Mr Tapie to pay the money back.

Today’s result was unexpected.

Even the trial’s chief prosecutor Jean-Claude Marin said the accusation was “very weak” and warned of confusion between “criminal negligence” and a “bad political decision”.

At the start of proceedings, the £355,000-a-year boss, of the global Washington-based institution, said: “I would like to show you that I am in no way guilty of negligence, but rather that I acted in good faith with only the public interest in mind.”

“Was I negligent? No. And I will strive to convince you allegation by allegation.”

Her lawyer Patrick Maisonneuve said on Europe-1 radio that Ms Lagarde was just following instructions from her administration and did not have time to read all 15 years of legal files on the case.

Ms Lagarde was only the fifth to be held before the Cour de Justice de la République since its inception in 1993.

IMF spokesman Gerry Rice said after Monday’s verdict that its executive board would meet soon “to consider the most recent developments”.

Another former IMF head, Rodrigo Rato of Spain, is standing trial on charges of misusing funds when he was boss of the Spanish lender Bankia.

Updated: 1-10-2021

Federal Investigators Probing AmEx Card Sales Practices

OCC and inspectors general offices of Treasury, FDIC and Federal Reserve probe company’s business-card sales practices.

Federal investigators are probing business-card sales practices at American Express Co., according to people familiar with the matter.

The inspectors general offices of the Treasury Department, Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. and Federal Reserve are investigating whether AmEx AXP 0.10% used aggressive and misleading sales tactics to sell cards to business owners and whether customers were harmed, the people said.

They are also examining whether specific employees contributed to the alleged behavior and if higher-level employees supported it, some of the people said.

The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency is also investigating business-card sales practices at AmEx, according to people familiar with the matter.

More than a dozen current and former AmEx employees previously told The Wall Street Journal that some salespeople strong-armed or misled small-business owners into signing up for cards to boost sales numbers.

Some salespeople misrepresented card rewards and fees, or issued cards that customers hadn’t sought, they said.

An AmEx spokesman said at the time that the company had found only a very small number of problems, which were resolved “promptly and appropriately,” including through disciplinary action.

“We have robust compliance policies and controls in place, and do not tolerate misconduct,” an AmEx spokeswoman said this week.

The civil investigation by the inspectors general offices is in early stages, according to some people familiar with the matter. The federal authorities have been staffing up investigation teams and have spoken with current and former employees, they said.

They are also reviewing whether the company’s compensation plans encouraged salespeople to cut corners, they said.

Spokespeople for the inspectors general offices at the Treasury, FDIC and Fed declined to comment.

The AmEx spokeswoman said that since last spring, “we have been cooperating with a regulatory review of small business card sales between 2015 and 2016.”

“We have conducted a detailed, independent review of these sales from this time period, and found no evidence of a pattern of misleading sales practices,” the spokeswoman said. “We take these matters seriously, and will continue to cooperate with our regulators.”

The previous Journal article focused on sales practices within the team that places calls to sell cards to small businesses. The spokeswoman said this group’s sales “represented approximately 0.25 percent of the 65 million total new cards American Express acquired world-wide between 2014 and 2019.”

The OCC’s investigation involves cards issued to business owners to replace their co-branded AmEx- Costco cards, according to people familiar with the matter. Costco Wholesale Corp. decided in 2015 to end its long-running partnership with AmEx, and AmEx launched an aggressive campaign to keep those customers.

The OCC, an independent branch of the Treasury, has been examining whether the problematic sales practices continued, according to some of the people familiar with the matter.

An OCC spokesman declined to comment.

After Wells Fargo & Co. disclosed a fake-accounts scandal in 2016, the OCC asked AmEx and other banks to review their sales practices. AmEx conducted a review and told the OCC it found few cases of inappropriate sales tactics, the Journal previously reported.

A whistleblower complaint filed with the OCC early last year said AmEx understated the number of problematic sales calls it reported to the OCC. According to the complaint, the company excluded some of the calls where AmEx employees tried to retain business-card holders who had been using AmEx-Costco business cards.

The complaint, which was reviewed by the Journal, also alleged a conflict of interest in how AmEx’s internal review was conducted. It said AmEx recruited a small number of employees in the sales division to help with the OCC-requested review. Those employees were told that the future of the sales division depended on the outcome of the review, the complaint said.

The investigation by the inspectors general offices is probing, among other issues, whether employees made sales calls that weren’t recorded, some of the people said. The investigators are also looking into how salespeople used customers’ personal information to make sales, these people said.

Current and former employees previously told the Journal that some salespeople in the Phoenix office placed calls from personal cellphones, and that senior managers sometimes closed sales on their unrecorded desk lines. Current and former employees also previously told the Journal that some salespeople pulled Social Security numbers and addresses from customer databases to submit card applications on behalf of business owners who didn’t always want them.

Updated: 2-14-2021

American Express Acknowledges DOJ Review of Card Sales

Company adds that it received a civil investigative demand from Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

American Express Co. acknowledged Friday that government agencies, including the Department of Justice, have reviewed the company’s sales practices regarding small-business cards.

The company said in a regulatory filing that in May it began responding to a regulatory review led by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and the DOJ’s civil division. AmEx said the review was connected to “historical sales practices relating to certain small business card sales.”

The Wall Street Journal reported last month that federal investigators including the inspectors general offices of the Treasury Department, Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. and Federal Reserve were investigating AmEx card sales. The investigators were looking into whether the company used aggressive and misleading sales tactics to sell cards to business owners and whether customers were harmed, the Journal reported.

The Justice Department is working with those offices, according to people familiar with the matter.

The Journal also reported last month that the OCC was investigating the company’s business-card sales practices.

More than a dozen current and former AmEx employees previously told the Journal that some salespeople strong-armed or misled small-business owners into signing up for cards to boost sales numbers. Some salespeople misrepresented card rewards and fees, or issued cards that customers hadn’t sought, they said.

AmEx has previously said it found only a very small number of problems that were resolved “promptly and appropriately,” including through disciplinary action.

AmEx said Friday that it had “conducted an internal review of certain sales from 2015 and 2016” and had “taken appropriate disciplinary and remedial actions, including voluntarily providing remediation to certain current and former customers.”

AmEx also said in its Friday regulatory filing that it received a grand-jury subpoena last month from the U.S. attorney’s office for the Eastern District of New York regarding small-business card sales. It also said it had received a civil investigative demand from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau “seeking information on sales practices related to consumers.”

The Company Said In The Filing: “We are cooperating with all of these inquiries and have continued to enhance our controls related to our sales practices. We do not believe this matter will have a material adverse impact on our business or results of operations.”

Deutsche Bank To Pay $130 Million To Settle Federal Criminal And Civil Investigations

German bank agreed to settle allegations that it violated laws against bribery by using middlemen and hiding payments.

Deutsche Bank agreed Friday to pay $130 million largely to settle allegations that it violated laws against bribery by using middlemen and hiding its payments to them as part of a global effort to win business.

The German bank admitted the wrongdoing in its agreement with prosecutors and reached a deal with the U.S. government over a commodity-trading scheme as it settles two longstanding cases before the change of administrations in Washington.

The bribery settlement exposed a wide-ranging effort by the bank to use consultants or middlemen to help it get deals in Saudi Arabia, Abu Dhabi, China and Italy. Regulators frown on the use of these consultants because they are often seen as a backdoor way to funnel cash to government or corporate officials.

The bank reached a so-called deferred-prosecution agreement with federal prosecutors in Brooklyn, meaning it won’t face criminal charges if it abides by certain requirements for three years.

The bank agreed to pay about $87 million to settle the criminal allegations. Deutsche Bank will pay $43 million to resolve a parallel investigation by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, the SEC announced Friday.

A Deutsche Bank spokesman said the bank couldn’t comment on the specifics of the resolutions but that it had taken significant remedial actions. “Our thorough internal investigations, and full cooperation with the DOJ and SEC investigations of these matters, reflect our transparency and determination to put these matters firmly in the past,” the spokesman said.

In court documents unsealed Friday, federal prosecutors accused Deutsche Bank of two separate schemes. In one, prosecutors accused the bank of falsifying records related to payments to third-party intermediaries, known as business development consultants.

These included concealing bribes to a client’s decision maker in Saudi Arabia and hiding millions of dollars in payments to an intermediary in Abu Dhabi, prosecutors said. They said that in Italy, Deutsche Bank falsely recorded payments to a regional tax judge who it employed to help attract clients.

In China, the bank hired a consultant who was a close friend of an official involved with setting up an investment fund with Deutsche Bank. It paid the consultant at least $1.6 million without fully documenting his services or reviewing invoices the consultant submitted for gifts and entertainment for government officials, the SEC said.

In the separate scheme that involved derivatives trading, Deutsche Bank agreed to pay $1.9 million to resolve allegations that former precious metals traders manipulated prices for gold and silver futures contracts. The bank was also assessed a $5.6 million fine, but the DOJ waived the amount because of earlier regulatory penalties paid by Deutsche Bank.

The traders were convicted in Chicago federal court in September of wire fraud. James Vorley and Cedric Chanu traded for the bank from its offices in London and Singapore. A jury found they manipulated prices for gold and silver futures contracts traded on exchanges operated by Chicago-based CME Group Inc.

The traders asked a judge in November to overturn the jury’s verdict or grant them a new trial. A third former trader, David Liew, pleaded guilty in 2017.

The settlement is part of an effort by Deutsche Bank Chief Executive Officer Christian Sewing to restore the lender’s tarnished reputation with regulators. The bank paid large fines in the U.S. and U.K. over weaknesses in its anti-money-laundering procedures and has been rebuked by Federal Reserve regulators over risk controls in its U.S. operations.

Deutsche Bank had previously said it was being investigated by the Justice Department for its hiring practices and use of consultants in foreign countries.

In 2019, the bank paid $16 million to settle charges by the Securities and Exchange Commission that it violated U.S. foreign bribery law by hiring relatives of foreign government officials in China and Russia. Deutsche Bank settled those Foreign Corrupt Practices Act charges without admitting to or denying the SEC’s findings.

In November, The Wall Street Journal reported that the bank was under pressure to exit Russia by outside monitors tracking its money-laundering controls. The monitors were appointed by New York state’s Department of Financial Services as part of a 2017 settlement related to “mirror trades,” in which the bank moved $10 billion of Russian client money out of the country.

Deutsche Bank has said it has committed significant resources to improve its money-laundering controls and has fully cooperated in investigations.

Updated: 5-30-2021

Fed Admonishes Deutsche Bank For Ongoing Compliance Failures

The Federal Reserve has privately told Deutsche Bank AG that its compliance programs aren’t up to snuff, signaling that the scandal-plagued bank is failing to adhere to a number of past accords with U.S. regulators, according to people familiar with the matter.

The Fed’s recent warning came in an annual regulatory assessment that said Deutsche Bank hadn’t improved its risk management practices despite being under confidential agreements with the central bank to fix the issues, the people said. The assessment letter has the German bank’s leaders bracing for potential sanctions, including the possibility of a large fine, said one person briefed on the matter.

The Fed’s latest admonishment is a setback for Chief Executive Officer Christian Sewing, who has been working diligently to repair Deutsche Bank’s relations with banking supervisors following a tumultuous period in which the lender stumbled from one crisis to the next. He now has a new hurdle to overcome — and it’s likely a big one.

Deutsche Bank spokesman Dylan Riddle said the firm doesn’t comment on any communications it has with regulators. A Fed spokesman also declined to comment.

Deutsche Bank has had multiple dust-ups with U.S. regulators — including foreign-exchange violations and ties to money-laundering cases. The lender has also been the subject of numerous Fed orders on how the company manages risks, and the firm’s efforts to overhaul its controls haven’t convinced the agency that the bank’s problems are behind it, the people said.

In a move that showed the firm is focusing on compliance issues, Deutsche Bank last week elevated Joe Salama, who had been general counsel for the Americas, to be global head of anti-financial crime and group money laundering officer. He succeeded Stephan Wilken, who had been in the post since October 2018.

While discussions with the Fed over Deutsche Bank’s ongoing missteps are in their early stages, the bank has faced similar rifts with the agency in recent years and been fined for them. The punishments include a $137 million settlement over allegations that traders rigged currency benchmarks and a $41 million penalty for money-laundering vulnerabilities.

Despite the Fed scrutiny, there are signs that Deutsche Bank has improved its risk management, at least in some areas. The firm emerged from the March collapse of Archegos Capital Management unscathed, while other banks that did business with Bill Hwang’s family office lost more than $10 billion combined.

The turn of fortune after years of gloom has lifted Deutsche Bank’s share price to outperform rivals as Sewing’s revamp has taken hold, and are up 38% this year.

Still, more trouble remains a possibility, as the Fed taking aim at the bank’s compliance systems shows. The stock is still trading at one of the steepest discounts to book value among European lenders with shares still far below their peak, and the bank has lost money in five of the past six years.

Updated: 12-17-2020

Credit Suisse Criminally Charged In Longstanding Money-Laundering Case

Swiss prosecutors allege the lender didn’t comply with provisions against money laundering, allowing a Bulgarian criminal organization to launder money through the bank between 2004 and 2008.

Credit Suisse Group AG CS +0.39% was charged by Swiss prosecutors Thursday for allegedly failing to prevent money laundering through the bank by clients and an employee, in a case stretching back more than a decade.

The Swiss attorney general’s office said Credit Suisse CS 0.39% in Zurich didn’t comply with provisions against money laundering or the bank’s own internal rules between 2004 and 2008 in opening and monitoring customer accounts.

It alleged that those and other flaws in the lender’s controls allowed a Bulgarian criminal organization to launder money through the bank during those years with the help of a bank executive. The organization allegedly recruited a Bulgarian wrestler and others in his orbit for operations transporting drugs and laundering money.

The former Credit Suisse executive, who wasn’t named, was charged with aggravated money laundering for allegedly assisting the Bulgarian organization and concealing the criminal origin of assets in transactions at Credit Suisse. Two more unnamed individuals, who prosecutors said were members of the Bulgarian organization, also were charged. Switzerland had started criminal proceedings in 2008.

Credit Suisse said it was astonished to be charged and refuted the allegations, including about “supposed organizational deficiencies.” It said it is convinced that the former employee, who left the bank in 2007, is innocent.

It said outside lawyers and consultants had reviewed its systems against money laundering during the yearslong probe and found its organizational setup was “correct and appropriate” throughout the period probed by prosecutors. It said those experts found prosecutors were alleging deficiencies based on rules and principles that didn’t apply at the time.

The charges come as Credit Suisse tries to untangle itself from a raft of mishaps this year that included fallout from a corporate-spying scandal. Like most global banks, it is involved in multiple criminal and civil probes and lawsuits over past alleged misconduct or governance or systems failures.

In 2014, it pleaded guilty to helping Americans evade taxes by hiding their wealth, as part of a settlement with the U.S. Justice Department. Rival UBS Group AG is currently fighting a $5 billion fine from a French court that ruled it illegally helped French clients hold undeclared Swiss accounts

The Swiss Federal Criminal Court could order the disgorgement of profits and impose fines up to 5 million francs, equivalent to about $5.7 million, Credit Suisse said. It said prosecutors would have to prove the former employee is guilty of crimes and that the bank’s purported organizational deficiencies enabled the employee and violated rules at the time.

The bank said its anti-money-laundering framework has been significantly expanded and strengthened since the probe started in 2008. It said meeting legal and regulatory requirements “has been and remains an absolute priority for Credit Suisse.”

Hundreds of compliance staff were hired in recent years to improve the bank’s systems, Credit Suisse executives have said previously. In 2018, its main regulator, Finma, said it found deficiencies in Credit Suisse’s anti-money-laundering processes in relation to dealings with clients linked to two oil companies and to FIFA, soccer’s governing body.

Credit Suisse Pays $600 Million To Settle U.S. Mortgage Case

Credit Suisse Group AG agreed to pay $600 million to settle a lawsuit over mortgage securities that collapsed in the 2008 financial crisis, an accord that locks in an expected hit to its profit.

The plaintiff, MBIA Insurance Corp., said late Thursday that it had reached an agreement, after a post-trial court decision that ordered the Swiss bank to pay about $604 million in damages. The settlement means there will be no appeal trial.

Credit Suisse is expecting to post a fourth-quarter loss when it reports earnings on Feb. 18, after setting aside $850 million for U.S. legal cases including MBIA and booking a $450 million impairment on a hedge fund investment.

“We are pleased to have resolved this legacy matter, which dates back to 2007. The settlement amount of $600 million is substantially less than our earlier guidance of up to approximately $680 million and has been fully provisioned for in our fourth quarter 2020 results,” Andreas Kern, a spokesman for Credit Suisse, said in an email.

MBIA’s shares rallied after the news, up almost 10% in pre-market trading.

Last month, the New York state judge presiding over the case ruled against Credit Suisse in the 2009 suit brought by the bond insurer over alleged misrepresentations of the quality of loans underlying residential mortgage-backed securities it guaranteed in 2007. MBIA had been seeking $686.7 million plus interest while Credit Suisse had estimated damages of $597.7 million.

Credit Suisse is among lenders including UBS Group AG, Morgan Stanley and Nomura Holdings Inc. that are still defending themselves against claims over the sale of the securities that plummeted in value during the 2008 crisis. Credit Suisse probably has the most exposure in repurchase litigation, as it faces suits seeking more than $3 billion, according to Bloomberg Intelligence’s Elliott Stein.

The case is MBIA Insurance Corp. V. Credit Suisse Securities LLC, 603751/2009, New York State Supreme Court, New York County.

Updated: 12-15-2020

FBI Is Investigating SEB, Swedbank, Danske Bank; Shares Tank

Shares in SEB AB, Swedbank AB and Danske Bank A/S plunged on Tuesday after one of Sweden’s biggest newspapers said the Federal Bureau of Investigation was probing allegations of money laundering and fraud.

Swedbank fell as much as 9.6%, SEB lost 7.6% and Danske dropped 4.2%, driving the three to the bottom of the Bloomberg index of European financial stocks.

The selloff followed a report in the Dagens Industri newspaper, which alleged that the banks are being investigated by three federal authorities in the U.S., namely the Justice Department, the FBI and a federal prosecutor’s office in New York. The newspaper didn’t say where it got the information.

Swedbank, SEB and Danske said the report contained no new information, amid ongoing investigations into allegations of money laundering. Danske, Denmark’s biggest bank, admitted more than two years ago that its Estonian unit was at the heart of one of Europe’s biggest dirty money scandals.

Frida Bratt, a savings economist at broker Nordnet, said that while the allegations against the banks are well known to most investors, the sudden selloff shows how vulnerable their shares are to bad news.

“This reflects the fear that the worst is not yet over in the money laundering issue,” she said.

Nicklas Andersson, a savings economist at another broker in Stockholm, Avanza, said, “Investors play it safe and reduce risk when information like this appears, before they know how to interpret that information.”

* Unni Jerndal, a spokeswoman for Swedbank, said the information contained in the Dagens Industri report is “old news.” The lender is in ongoing talks with U.S. authorities in connection with existing probes into allegations of money laundering, she said by phone. For legal reasons the bank can’t identify which authorities.

* Frank Hojem, a spokesman for SEB, also called the information “old” and said the bank has been in touch with U.S. authorities, but that it’s unaware of “any accusations” against it.

* Stefan Singh Kailay, a spokesman for Danske, said “it is known that we are being investigated by authorities in Denmark, the U.S., Estonia and France, and we continue to be in close dialogue with them all.” He said Danske is “unable to estimate any potential outcome of these dialogues,” which he said includes the “timing.”

The Probes

“The FBI’s involvement doesn’t strike me as a surprise,” said Elliott Stein, a senior litigation analyst for Bloomberg Intelligence in New York. “We’ve known for some time that the U.S. Justice Department was investigating potential money laundering violations in at least some Nordic banks. DOJ’s investigative work is often done by the FBI in conjunction with prosecutors.”

Danske has previously said it’s being investigated in the U.S. and Europe after admitting that a large part of about 200 billion euros ($243 billion) in non-resident flows through an Estonian unit were suspicious.

Swedbank has also said it’s being probed in the U.S., after its Baltic unit was allegedly used for transferring suspicious transactions. It was fined in Sweden earlier this year for its anti-money laundering breaches.

SEB has also been targeted in an investigation by Sweden’s regulator regarding allegations against the bank that it handled suspicious transactions via its Baltic operations. The lender has previously said it had been contacted by U.S. authorities, without elaborating.

According to Dagens Industri, the Swedish Ministry of Justice received a formal request for legal aid from the U.S. Department of Justice this summer due to the money laundering investigation in that country.

International Bank Agrees To Pay US $70 Million To Resolve CFTC Charges That It Attempted To Manipulate ISDAFIX Benchmark

Deutsche Bank Securities Inc. agreed to pay a fine of US $70 million to resolve charges brought by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission alleging that, from at least January 2007 through May 2012, it attempted to manipulate the US Dollar International Swaps and Derivatives Association Fix benchmark. The CFTC claimed that DBSI engaged in such violation through the acts of some of its traders who caused the firm to make false submissions in order to impact the Fix in a direction to help benefit the firm’s trading book.

American Express Gave Small Businesses One Rate, Then Secretly Raised It

For more than a decade, American Express Co.’s foreign-exchange unit recruited business clients with offers of low currency-conversion rates before quietly raising their prices, according to people familiar with the matter.

AmEx’s foreign-exchange international payments department routinely increased conversion rates without notifying customers in a bid to boost revenue and employee commissions, the people said. The practice, widespread within the forex department, was occurring until early this year and dates back to at least 2004, the people said.

The practice targeted mostly small and midsize businesses, the people said, a group of customers that accounts for about a quarter of the company’s credit-card revenue. AmEx, one of the largest small-business card issuers in the U.S., earlier this year said it hoped to become the leading payments and working-capital provider for small and middle-market companies.

AmEx said it doesn’t have contractual pricing arrangements with most of its foreign-exchange customers. “We have training, control and compliance oversight and believe that our transactions are completed and reported in a fair and transparent manner at the rates which the client has authorized,” said spokeswoman Marina Norville.

On Monday afternoon, Ms. Norville said the company takes “allegations like these very seriously” and will conduct a review with an external party to determine if its standards are being met. “If we find that we fell short of the mark, we will fix the problems and take appropriate actions to make sure it doesn’t recur,” she said.

Although the forex business is small—accounting for less than half of a percentage point of AmEx’s total revenue—it is among a suite of services the company offers to its small-business customers. Small business is a key growth area for AmEx, which has long sought to distinguish itself from rivals JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Citigroup Inc. by offering generous card-related benefits and tailored services to its consumer and business clients.

Current and former employees say the division’s commissions-driven culture fueled the practice.

Here’s how it worked, according to current and former employees: Salespeople would often tell potential clients that AmEx would beat the price they were paying banks or other financial institutions to convert currency and send money abroad. The salespeople didn’t inform customers that the margin, a markup that AmEx tacks on to the base currency exchange rate, was subject to increase without notice, they said. Prospective clients with certain AmEx cards also were accurately told they could earn points for the transactions, they added.

Some time later, salespeople would increase the margin without informing the customers, the current and former employees said. To spot the change, customers generally would have to log in to their accounts and compare the rate AmEx was offering to the market exchange rate at the time of the transaction. As recently as this year, they said, some customers had margins increased anywhere from 0.05 to 0.25 of a percentage point. In earlier years, margins rose by as much as 3 percentage points, according to former employees.

When clients did notice a change and inquired, AmEx salespeople sometimes would blame a glitch or other technicality and lower the margin, according to current and former employees and emails.

Current and former employees say the division targeted smaller businesses in part because they’re less likely than large corporations to have employees who closely track forex transactions.

Managers directed salespeople to keep the details of the payment arrangements hazy when speaking with potential customers and to avoid putting pricing terms in emails, current and former employees said.

Managers in the division tapped the brakes on the practice in recent months, according to current and former employees, following an article published late last year alleging similar practices at Wells Fargo & Co. An AmEx manager told salespeople they would need his approval before offering prospective clients a margin of less than 0.70 of a percentage point.

Current and former employees said the price changes were common knowledge within the forex business. Paul Hargreaves, who ran AmEx’s global foreign-exchange services division for many years, was aware of the tactic, former employees said. Following a long career with AmEx, he left the company earlier this year, Ms. Norville said.

Mr. Hargreaves couldn’t be reached for comment.

Current and former employees describe an environment focused on bringing in as many new clients as possible and squeezing revenue out of them before they depart. Employees were told that the average forex customer did business with AmEx for around three years, they said.

“Who cares if they come or go? Let’s make money while we have them,” one current employee said, referring to the attitude within the division.

“We constantly reinforce the importance of acting in the best interest of our customers,” said AmEx spokeswoman Ms. Norville.

Commissions are tied to monthly revenue targets, which are heavily influenced by margins and transaction volume, current and former employees said.

Salespeople who hit their targets earn a commission of 15% of the monthly revenue new customers generate, according to current and former employees. Commissions rise to around 25% after an annual revenue target of as much as around $285,000 is exceeded, they said. Sales reports distributed by managers list how much revenue salespeople generate, they added.

At AmEx, rate increases often would occur after managers told salespeople to review their accounts and adjust pricing, the current and former employees said.

Some salespeople said they were encouraged to employ the tactic at the division’s training program for new employees. One former employee said he was told during training to sign up as many accounts as he could in his early days and to go back later and adjust the rates upward to hit revenue targets.

Updated: 3-1-2020

AmEx Staff Misled Small-Business Owners to Boost Card Sign-Ups

Questionable sales tactics cropped up in push to retain cardholders after Costco partnership ended.

The American Express Co. saleswoman had finally convinced Bryan Daughtry to apply for a card. There was just one thing: She had to run a credit check.

Mr. Daughtry, who owns a disaster-cleanup company in Ohio, balked. He was trying to get a mortgage and didn’t want the inquiry to dent his credit score. She refused to stop the process, he said, checked his credit, and his application was approved.

“That left a bad taste in my mouth,” said Mr. Daughtry.

Some AmEx salespeople strong-armed business owners like Mr. Daughtry to increase card sign-ups, according to more than a dozen current and former AmEx sales, customer-service and compliance employees. The salespeople have misrepresented card rewards and fees, checked credit reports without consent and, in some cases, issued cards that weren’t sought, the current and former employees said.

An AmEx spokesman said the company found a very small number of cases “inconsistent with our sales policies.” “All of those instances were promptly and appropriately addressed with our customers, as necessary, and with our employees, including through disciplinary action,” he said.

“We have rigorous, multilayered monitoring and independent risk-management processes in place, which we continuously review and enhance to ensure that all sales activities conform with our values, internal policies and regulatory requirements,” he said. “We carefully examine any issues raised through our various internal and external feedback channels and audits, and we do not tolerate any misconduct.”

Current and former employees said the dodgy sales tactics date to at least 2015, when AmEx was scrambling to retain Costco Wholesale Corp. small-business customers after the warehouse club ended their long-running partnership.

The deal’s demise was a huge blow to AmEx. For 16 years, the warehouse club didn’t accept credit cards in its stores from any company but AmEx. AmEx also issued credit cards branded with the Costco logo that offered special perks.

Small businesses were a particularly valuable slice of the Costco cohort. The warehouse club sells a lot of things they need—two-liter jugs of olive oil, bulk cleaning supplies, big-screen TVs, tires for their delivery vans. AmEx was about to lose the stream of fees on all of those card purchases.

Customers were also free to use their Costco-branded cards elsewhere, and they did. Kenneth Chenault, then AmEx’s chief executive, said that about 70% of spending on the Costco cards were non-Costco purchases. Those fees would go away, too.

The potential revenue hit from the loss of the Costco customers was enormous, so AmEx launched an aggressive campaign to keep them. The push ushered in an era of escalating sales goals and hefty commissions that persists today.

Mr. Daughtry said he didn’t seek out the AmEx card. The saleswoman called his office numerous times over several weeks last spring before she finally got him on the line. Although he said he never consented to the card, he got a $250 bill for its annual fee in the mail.

He called to complain. “I told them I wouldn’t stand for it, and I would take some type of action,” Mr. Daughtry said. AmEx agreed to drop the charge.

Known for courting well-heeled consumers, AmEx also relies heavily on its business customers. It derives about 30% of its revenue from the services it sells to a range of companies—from mom-and-pop shops to multinational corporations.

AmEx is the largest business-card issuer in the U.S., according to the Nilson Report. Small businesses are an especially important constituency; AmEx has said its small-business card portfolio is larger than that of its nearest five competitors combined.

The task of retaining Costco customers initially fell to about a hundred AmEx salespeople in Phoenix. The “top client acquisitions” group employees were told that the Costco retention program—Project Lincoln—was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to make big money. Their task: dial up Costco business-card holders and convince as many as possible to sign up for AmEx business cards.

The dial-for-dollars strategy worked. AmEx managed to hang onto a big chunk of the Costco customers. Within six months of the push, some salespeople had earned commissions of $50,000 to $100,000, according to current and former employees. BMWs and other high-end cars began appearing in the office parking lot.

Some salespeople took shortcuts to get there, current and former employees said.

Salespeople are required to call customers on their recorded desk lines, but some placed calls from personal cellphones, often while standing in a breezeway between two buildings on AmEx’s Phoenix campus, according to current and former employees. Senior managers sometimes closed sales on their unrecorded desk lines.

There were red flags. Some 40% to 45% of cards that were being mailed out as part of Project Lincoln were being activated, according to a 2015 presentation by a senior employee in the division—well below the typical rate of at least 60%. Phoenix salespeople were earning the highest commissions, but the accounts they had opened had the lowest usage rates of any other group, said people familiar with the presentation.

An executive at the company’s headquarters in New York flagged the low activation rates to senior sales employees in Phoenix, according to people familiar with the matter. Commissions were scaled back, and some salespeople suspected of dicey behavior were fired, the people said.

The Costco retention campaign ended in 2016, but the problematic sales practices didn’t, current and former employees said. Salespeople who had grown accustomed to the big commissions from the retention program were back to mostly relying on cold calls to meet their now-higher monthly sales targets.

Salespeople sometimes told hesitant business owners they would send informational “welcome kits” in the mail. Instead, they used Social Security numbers and addresses gleaned from customer databases to submit applications on the business owners’ behalf. The “welcome kits” were simply the cards and their associated paperwork.

It didn’t take long for senior sales employees to begin spotting the same practice at another AmEx office in Florida focusing on business-card sales, they said.

Some employees tried to warn higher-ups about the questionable tactics. In early 2017, a saleswoman contacted Susan Sobbott, at the time president of global commercial services. She connected the saleswoman with employees in human resources and risk management so they could investigate the allegations.

When human-resources staff reached out to the employee’s manager, he denied the saleswoman’s allegations and said she was underperforming. The employee later left the company. The manager was later promoted. Ms. Sobbott has since left AmEx.

“The senior leader appropriately referred the matter to independent groups outside the business, who then investigated the allegations and found them to be unsubstantiated,” the AmEx spokesman said.

Around this time, AmEx was conducting a broad review of its sales tactics. After Wells Fargo & Co. disclosed in September 2016 that branch employees had opened fake accounts without customer consent, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency asked AmEx and other banks it oversees to make sure their employees weren’t doing the same thing.

AmEx reviewed calls from desk phone lines of sales staff between 2014 and 2017 and found evidence of misleading behavior, according to people familiar with the matter. Some customers were told their cards were being upgraded when they were being given new cards; others received more cards than they sought. Salespeople skipped over required disclosures and, in some cases, falsely told customers their credit wouldn’t be checked, the people said. Cards also had been issued without customer consent, they said.

AmEx told the OCC it found few cases of inappropriate sales tactics, the people said. The company reprimanded or fired a small number of employees and asked credit-reporting firms to remove inquiries from the credit reports of customers who didn’t consent to the checks, they said. AmEx asked customers who received cards they didn’t authorize if they wanted to keep them, the people said.

The review didn’t capture calls made from employees’ cellphones, nor did it catch those made by senior sales staff on unrecorded lines, according to people familiar with the matter.

An AmEx spokesman said the company “found no evidence of a pattern of misleading sales practices.”

Last year, the OCC listened to some AmEx sales calls and found evidence of misconduct, according to people familiar with the matter.

AmEx said the business-card sales teams were responsible for around 0.25% of 65 million new cards issued by the company world-wide between 2014 and 2019, or about 162,500 cards. “Less than 0.25% of the group’s sales activities have been identified by us as inconsistent with our sales policies,” a spokesman said.

As recently as last year, AmEx’s customer-service department fielded complaints from business owners who said they had received cards they didn’t sign up for, according to people familiar with the matter. Some of those calls made their way to the company’s executive escalations department, some of the people said. Angry customers were often offered extra rewards points to drop their complaints, they said.

Customers also complained that salespeople misled them about card fees and rewards, current and former employees said.

Abdelnasser Abdeen said a salesperson told him he wouldn’t be charged an annual fee if he didn’t activate his AmEx card. Soon after the card came in the mail last year, he got a bill for $295. When he called to complain, Mr. Abdeen said he was told the card rewards would more than cover the fee.

“They were pushing to sell me that card,” said Mr. Abdeen, who owns a used-car dealership in northern Virginia. “I didn’t like that.” He canceled the card and signed up for a different type of AmEx card. He said he isn’t getting the rewards points he was told he would get.

In the fall, an AmEx salesman convinced Glen Vitale to take out six business cards with an unusually generous offer of four rewards points per dollar on certain spending categories for the first $150,000 spent. He said he was led to believe he would pay a single annual fee of $295 for all the cards.

Mr. Vitale, an executive at an auto-parts manufacturer in Pompano Beach, Fla., began using one of the cards right away. The salesperson emailed to ask whether he would make a small purchase with the others to test their security chips.

Soon after, Mr. Vitale said he got six separate bills for $295 each. The salesperson told him the rewards would more than cover the cost.

“I said, ‘I hope you’re right,’ and I went on with my business,” he said. AmEx recently fired the salesman.

Updated: 2-27-2020

Wells Fargo To Pay $35 Million To Settle ETF Probe

SEC says sales controls weren’t sufficient over products called too risky for some investors.

Wells Fargo & Co. agreed to pay $35 million to settle regulatory claims that its financial advisers recommended exchange-traded funds that were too risky for some clients.

The Securities and Exchange Commission’s investigation targeted Wells Fargo’s sale of inverse ETFs, a type of fund that moves in the opposite direction of an index it tracks. Inverse ETFs can be used to hedge other positions or bet on a falling market, but the products are complex enough that regulators have warned for years they are unsuitable for many individual investors.

The sanction follows on an earlier blemish for similar conduct in 2012, when Wells Fargo paid $2.7 million to the brokerage industry’s self-regulator for selling inverse and leveraged ETFs without reasonable supervision. The SEC’s settlement order said Wells Fargo updated its policies for selling the products in 2012, but the controls still weren’t sufficient.

The deal comes one week after Wells Fargo resolved a bigger regulatory cloud, a multiyear investigation into how low-level employees who were stressed by high sales goals opened fake and unauthorized bank accounts. Wells Fargo paid $3 billion to settle those allegations.

Brokers and investment advisers have struggled for years with how to sell inverse and leveraged ETFs. Leveraged ETFs employ derivatives to deliver two or three times the daily price moves of benchmarks. The SEC approved the products over a decade ago and has been reining in their use by individual investors ever since.

Wells Fargo said Thursday that its advisory business “no longer sells these products in the full-service brokerage.”

The products are popular with some traders and are intended for daily, tactical trading. But many brokers have recommended the products to investors who held the funds for longer periods, which can lead to surprises.

For example, an inverse fund that should rise in value when the market declines can actually lose value during periods of sustained volatility. That outcome stems from the effects of daily compounding, which over longer periods produces returns that can vary from a leveraged or inverse ETF’s objectives.

The SEC’s settlement order said Wells Fargo’s employees advised clients from 2012 to 2019 to hold the funds “in many cases for months or years” in accounts, including those investors saving for retirement.

The SEC said the $35 million penalty would be used to compensate clients who had losses and held the funds for more than 30 days.

CFTC Names Four Banking Organization Companies, A Trading Software Design Company And Six Individuals In Spoofing-Related Cases;

The Same Six Individuals Criminally Charged Plus Two More: On January 29, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission and the Department of Justice coordinated announcements regarding the filing of civil enforcement actions by the CFTC, naming five corporations and six individuals, and criminal actions by the DOJ against eight individuals – including six of the same persons named in the CFTC actions – for engaging in spoofing activities in connection with the trading of futures contracts on United States markets.

Four of The Corporations – part of global banking organizations – simultaneously resolved their CFTC-brought civil actions. These four corporations were Deutsche Bank AG and its wholly owned subsidiary Deutsche Bank Securities Inc., UBS AG and HSBC Securities (USA), Inc. DB and DBSI settled their CFTC enforcement actions by agreeing to jointly and severally pay a fine of US $30 million; UBS settled by consenting to a sanction of US $15 million; and HSBC settled by agreeing to a fine of US $1.5 million. The companies additionally agreed to continue to maintain surveillance systems to detect spoofing; ensure personnel “promptly” review reports generated by such systems and follow‑up as necessary if potential spoofing conduct is identified; and maintain training programs regarding spoofing, manipulation and attempted manipulation.

Generally, DB, UBS and HSBC were charged for the spoofing activities of their employees on the Commodity Exchange, Inc. in gold and other precious metal futures contracts. Typically, alleged the CFTC, the employees placed a small lot order on one side of a market and larger lot orders on the other side of the same market for the purpose of artificially moving the market to effectuate the execution of the smaller lot order. As soon as the small lot order was executed, the larger lot orders were cancelled.

DB was also charged with manipulation and attempted manipulation, and UBS was additionally charged with attempted manipulation. The CFTC claimed that one DB and one UBS employee placed orders to try to trigger customers’ stop loss orders to benefit proprietary trading.

DBSI – a registered futures commission merchant – was charged with failure to supervise. According to the CFTC, DBSI maintained a surveillance system that detected many instances of potential spoofing by DB traders, whose accounts it carried. However, said the CFTC, DBSI failed to follow up on “the majority” of potential flagged issues.

The CFTC acknowledged each firm’s cooperation during its investigation. The Commission additionally noted that UBS self‑reported its own misconduct in response to a firm-initiated internal investigation. The CFTC said that it was previously not aware of the misconduct.

Additionally, the CFTC charged Jitesh Thakkar and Edge Financial Technologies, Inc. – a company Mr. Thakkar founded and for which he served as president – with spoofing and engaging in a manipulative and deceptive scheme for designing software that was used by an unnamed trader to engage in spoofing activities. This enforcement action was filed in a federal court in Chicago, Illinois.

According to the CFTC, Mr. Thakkar and Edge Financial aided and abetted the unnamed trader’s spoofing by designing a custom “Back-of-Book” function. This function automatically and continuously modified the trader’s spoofing orders by one lot to move them to the back of relevant order queues (to minimize their chance of being executed) and cancelled all spoofing orders at one price level as soon as any portion of an order was executed. The CFTC said that the unnamed trader admitted using the Back-of-Book function to engage in spoofing activities involving E-mini S&P futures contracts traded on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange from January 30 through October 30, 2013.

It appears from language in a parallel criminal complaint also filed against Mr. Thakkar in a federal court in Chicago, Il., that the trader he is alleged to have assisted was likely Navinder Sarao. In November 2016, Mr. Sarao pleaded guilty to criminal charges for allegedly engaging in manipulative conduct through spoofing-type activity involving E-mini S&P futures contracts traded on the CME between April 2010 and April 2015, including illicit trading that contributed to the May 6, 2010 “Flash Crash.” He also settled a CFTC enforcement action related to the same conduct. (Click here for background regarding Mr. Sarao’s settlement and initial charges in the article “Alleged Flash Crash Spoofer Pleads Guilty to Criminal Charges and Agrees to Resolve CFTC Civil Complaint by Paying Over $38.6 Million in Penalties,” in the November 13, 2016 edition of Bridging the Week.)

Previously, Mr. Thakkar has served as a member of the High Frequency Trading Subcommittee of the CFTC’s Technology Advisory Committee.

The CFTC also filed civil complaints against Cedric Chanu, Andre Flotron, Krishna Mohan, James Vorley and Jiongsheng Zhao, alleging spoofing and engaging in a manipulative and deceptive scheme. The DOJ announced that criminal complaints were filed against the same persons, as well as Edward Bases and John Pacilio. The criminal case against Mr. Flotron was filed in September 2017. (Click here for details in the article “Spoofing Case Filed in Connecticut Against Overseas-Based Precious Metals Trader,” in the September 17, 2017 edition of Bridging the Week.) Both the civil and criminal actions were filed in federal courts in Connecticut, Illinois and Texas.

CME brought and settled a disciplinary action against Mr. Zhao, alleging disruptive trading in November 2017 (click here for details). To resolve the CME action, Mr. Zhao agreed to pay a fine of US $35,000 and be barred from access to all CME Group exchanges for ten business days.

Prior to the filing of the eight criminal actions by the DOJ, only three persons had previously been criminally prosecuted for spoofing. (Click here for background in the article “Former Newbie Bank Trader Pleads Guilty to Criminal Charges and Settles CFTC Civil Charges for No Fine for Spoofing, Attempted Manipulation and Manipulation of Gold and Silver Futures,” in the June 4, 2017 edition of Bridging the Week.)

My View: The settlement against DB for spoofing and DBSI for failure to supervise was resolved by an agreement by the firms to jointly and severally pay a fine of US $30 million.

In settlements, the rationale for any provision – including the precise amount of a fine – is correctly not part of the public record. As a result, it would be disingenuous to speculate why any one provision might have been agreed.

Hopefully, however, through this settlement, the CFTC is not signaling that it equates the acts of a principal spoofer with the failure of a carrying FCM to follow up on its surveillance system’s detection of possible misconduct by a customer. If this was the CFTC’s intent, it raises the supervisory obligation of FCMs to a new and highly unfair level. Certainly, the commission of an illegal act, or even the affirmative aiding and abetting of such act, must be regarded as far more serious than the failure of a carrying broker to act after it detects such potential misconduct through its ordinary surveillance system.

This matter is the second recent settlement entered into by the CFTC in recent months that seems to impose an extraordinarily high standard of oversight responsibility on FCMs.

Just a few months ago, Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith Incorporated agreed to pay a fine of US $2.5 million to resolve charges brought by the CFTC that it failed to diligently supervise responses to a CME Group Market Regulation investigation related to block trades executed by its affiliate, Bank of America, N.A. on the CME and the Chicago Board of Trade. The CFTC said that the responses provided by BANA were not accurate. However, there was no indication that Merrill Lynch was aware or had reason to believe that its affiliate’s responses were inaccurate. (Click here for further details in the article “FCM Agrees to Pay US $2.5 Million CFTC Fine for Relying on Affiliate’s Purportedly Misleading Analysis of Block Trades for a CME Group Investigation,” in the September 24, 2017 edition of Bridging the Week.)

Earlier, in 2016, Advantage Futures LLC, Joseph Guinan (its majority owner and chief executive officer), and William Steele (who until May 2016 was Advantage’s chief risk officer), settled charges brought by the CFTC related to the firm’s handling of the trading account of one customer in response to three exchanges’ warnings and for the firm’s alleged failure to follow its own risk management policies. The CFTC claimed that, after three exchanges alerted Advantage to concerns they had regarding the trading of one unspecified customer’s account which they considered might constitute disorderly trading, spoofing and manipulative behavior, the firm initially failed “to adequately respond to the Exchange inquiries and did not conduct a meaningful inquiry into the suspicious trading.” (Click here for background and analysis in the article “FCM, CEO and CRO Sued by CFTC for Failure to Supervise and Risk-Related Offenses,” in the September 25, 2016 edition of Bridging the Week.)

FCM supervisory systems may, on occasion, fail to live up to regulator expectations. When that happens, a FCM may be fairly subject to penalties and other sanctions. However, in this settlement, the CFTC seems to equate the magnitude of the principal offense of spoofing with a failure to act after the detection of such potential offense by a customer – albeit an affiliated entity. If this is the intended message, the potential cost of engaging in the FCM business, or other businesses requiring CFTC registration, has just increased dramatically and unfairly.

Legal Weeds: Late last year, James McDonald, the CFTC’s Director of its Division of Enforcement, indicated during multiple public speeches that potential wrongdoers who voluntarily self-report their violations, fully cooperate in any subsequent CFTC investigation, and fix the cause of their wrongdoing to prevent a re-occurrence will receive “substantial benefits” in the form of significantly lesser sanctions in any enforcement proceeding and “in truly extraordinary circumstances,” no prosecution at all. The Division also released a formal Updated Advisory on Self Reporting and Full Cooperation, which memorialized and expanded the elements of Mr. McDonald’s presentations (click here to access).

The current settlements by DB, DBSI and UBS may provide some insight into what self-reporting might concretely be worth.

Factually, the allegations against DB and UBS were materially similar. In both actions, traders at each firm engaged in alleged spoofing activity that constituted attempted manipulation for a significant period of time – in DB’s circumstance, from February 2008 through at least September 2014, and in UBS’s situation, from January 2008 through at least December 2013. Some facts varied in each enforcement action, but the agreed fine was US $30 million combined for DB and DBSI and $15 million for UBS. Although the CFTC acknowledged both firms’ cooperation in its investigations, the CFTC noted that, in connection with UBS, “[d]uring the course of an internal investigation, [the firm] discovered potential misconduct, of which the Division was previously unaware” and promptly self-reported the misconduct. The CFTC said that both firms’ fines were “substantially reduced” because of their cooperation, but UBS’s fine was one-half that of the DB entities’ combined fine.

Under the Division of Enforcement’s new math – come forward + come clean + remediate = substantial settlement benefits – it appears that, at least in these two matters, coming forward was worth a 50% saving off an already reduced settlement attributable to coming clean!

(Click here for details on the CFTC’s new approach to settlements in the article, “New Math: Come Forward + Come Clean + Remediate = Substantial Settlement Benefits Says CFTC Enforcement Chief” in the October 1, 2017 edition of Bridging the Week.)

Compliance Weeds: The Thakkar and Edge Financial Technologies CFTC enforcement and criminal actions must be taken as a significant warning to programmers and technology firms that developing software to assist a trader in violating the law could result in a charge against such persons for such violation as if they ultimately committed the violation themselves. As a result, developers and their employers requested to customize software should raise any concerns about the purpose for such customization if the purpose seems contrary to law. They should not just accept all instructions and program! However, this may impose a heightened burden on programmers and could stifle the development of legitimate new technology.

JPMorgan Chase Settles Allegations It Violated U.S. Sanctions

The bank says it has since improved its compliance systems.

JPMorgan Chase Bank NA agreed to pay $5.3 million to settle allegations it violated various U.S. sanctions programs.

The bank was hit with two penalties, one monetary and the other a finding of violation. Both, the U.S. Treasury Department said, were connected to failures in its screening processes.

JPMorgan Chase voluntarily disclosed the issues more than six years ago, according to company spokesman Brian Marchiony.

“We have since upgraded our systems and made substantial enhancements to our sanctions compliance program,” he said.

The settlement relates to 87 net-settlement transactions between January 2008 and February 2012 totaling more than $1 billion.

Each of the 87 transactions involved a U.S.-based JPMorgan Chase client and a foreign entity with connections to eight airlines that were, at various times, subject to U.S. sanctions, the Treasury said. The Treasury didn’t identify the U.S. client or the foreign entity.

Before January 2012, JPMorgan didn’t appear to have had a process to independently evaluate members of the foreign entity despite receiving red-flag notifications on at least three occasions, the Treasury said.

“The bank failed to screen…for purposes of [sanctions] compliance, despite being in possession of the necessary information to enable screening,” the Treasury said in its penalty notice.

But since then, the Treasury said, the bank screened all net-settlement participants until it terminated its relationship with the American client. It also increased its compliance staff, implemented new sanctions-screening software and enhanced employee compliance training.

No managers or supervisors were aware of the transactions that led to the sanctions violations, the Treasury said.

Updated: 8-14-2020

An AmEx Manager Says She Spoke Up About Sales Problems, Then Got Pushed To The Side

Sophia Lewis’s career was on the rise. Then she began telling her bosses about questionable sales practices. ‘Things started going downhill.’

Sophia Lewis thought she would build a long career at American Express Co. A few years in, though, she was telling her bosses that something was wrong.

Ms. Lewis said she saw some AmEx employees routinely submit corporate card applications without verifying the companies’ financial information, pocketing commissions each time. Beginning in 2018, Ms. Lewis said, she alerted higher-ups about those complaints. But AmEx, she said, had created a culture where employees can get rewarded for breaking rules.

“It was when I started raising red flags,” she said, “that things started going downhill.” The company suspended her in February for reasons it said are unrelated to her complaints. Other current and former employees said they saw the same behavior that Ms. Lewis described.

An AmEx spokesman said the company, based in New York, is committed to fostering a culture of respect and integrity, and provides multiple channels for employees to raise concerns. “We encourage our colleagues to speak up when they believe our policies, values or standards are not being upheld, and we strictly prohibit retaliation,” he said.

In the race for customers, AmEx has relied heavily on commissions to motivate salespeople. More than a dozen current and former AmEx employees in sales, customer service and compliance previously told The Wall Street Journal that salespeople strong-armed small-business owners to increase those card sign-ups, sometimes misrepresenting card rewards or issuing cards that weren’t sought. An AmEx spokesman said at the time that the company had found only a very small number of problems, which were resolved “promptly and appropriately,” including through disciplinary action.

Banking regulators have kept a close eye on sales incentives since the Wells Fargo & Co. fake-accounts scandal exploded in 2016. According to an internal 2018 AmEx document, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency told AmEx to change how it paid employees who sold small-business and corporate cards—the division where Ms. Lewis works. The regulator said AmEx’s commission structure could increase the risk of misconduct.

An OCC spokesman declined to comment. An AmEx spokesman said the matter was raised by the OCC in 2017 and that the company addressed it.

In response to Ms. Lewis’s allegations, the AmEx spokesman said that her higher-ups had properly referred her concerns to “our independent investigatory teams.” He said the claims “were thoroughly reviewed and appropriately addressed” and that “no instances of customer harm were identified.”

Ms. Lewis, now 50 years old, joined AmEx’s Phoenix office in 2014 to sell small-business cards. She had worked for years selling mortgages.

By 2017, she was promoted to oversee a group of about 10 employees selling small-business and corporate cards.

In 2018, Ms. Lewis said, some of her employees told her about what they believed to be problems with certain salespeople on another team.

For a business to be eligible for a corporate card, it typically needed at least $4 million in annual revenue, according to current and former employees and company documents.

Ms. Lewis and other current and former employees said some salespeople were submitting applications without verifying their numbers. Many of the businesses fell far short of the $4 million threshold, they said.

Ms. Lewis told a sales director about what she and her employees were seeing, and AmEx launched an investigation.

The AmEx spokesman said that the company may make exceptions to the $4 million threshold, and that it is only one factor used to determine whether a business qualifies for a corporate card. “All applicants undergo a thorough risk assessment to determine their creditworthiness,” he said.

The spokesman also said that AmEx “found no violations of policies or procedures” when it reviewed Ms. Lewis’s claims.

The questionable applications typically wouldn’t get approved if underwriting employees reviewed them. But some did, and salespeople pocketed commissions either way, often about $475 to $650 per application, Ms. Lewis and former employees said.

Soon, in Ms. Lewis’s unit, AmEx changed commissions for corporate cards to pay them after the cards were approved and used. The AmEx spokesman said the company regularly reviews and modifies sales incentives, in part to reduce circumstances that could lead to inappropriate sales practices. He said the 2018 change was made “to better align with business objectives.”

After the AmEx investigation into Ms. Lewis’s claims about sales practices, she applied for several positions and didn’t get them.

In July 2019, she filed a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission alleging racial and gender discrimination. Ms. Lewis, who is Black, said she was also frustrated about not getting promoted.

The EEOC forwarded her complaint to the Arizona attorney general’s office, which closed her case last month, citing insufficient evidence. Ms. Lewis is appealing.

The AmEx spokesman said the company had “found no basis for” Ms. Lewis’s allegations of discrimination. “We are deeply committed to fostering a diverse and inclusive workplace,” he said.

Spokespeople for the EEOC and the Arizona attorney general declined to comment.

Around mid-2019, Ms. Lewis said, her salespeople told her that some employees in Arizona and Florida were again engaging in the questionable tactics she had previously flagged, including not verifying companies’ financial information. By then, AmEx had returned to paying commissions for applications—though now it could claw back the money if underwriters rejected them.

Ms. Lewis again alerted her bosses. In October, for example, she emailed several sales leaders, citing about a dozen examples of what she saw as problematic sales, according to a copy of the email reviewed by the Journal. In one case, a salesperson had submitted a corporate card application for a Greenbelt, Md., financial-services firm without including verifying documents and while using a corporate ID number related to Apple Inc. The financial-services firm isn’t related to the technology giant.

When asked about the exchanges that Ms. Lewis described, the AmEx spokesman said: “When the employee raised concerns of potential sales practice violations, they were properly referred by her leaders to our independent investigatory teams outside of her business unit, thoroughly reviewed and appropriately addressed.”

A few days later, Ms. Lewis was told by email that two of those sales leaders had met with “internal audit,” which was looking into the matter.

A week later, Ms. Lewis said, she was called into a sales leader’s office, where she was told to consider how she was affecting her “brand” and whether she wanted to remain at AmEx, Ms. Lewis said. He followed up with an email saying she wasn’t supposed to conduct her own investigations, according to a copy of the email reviewed by the Journal.

Ms. Lewis replied that she thought she was doing the right thing by bringing problems to leadership, according to a copy of the email reviewed by the Journal.

Ms. Lewis said she struggled over what to do next. Her husband encouraged her to press on. So did her mother.

In December, Ms. Lewis filed a Labor Department complaint. A Labor Department spokeswoman didn’t comment on Ms. Lewis’s case.

In February, Ms. Lewis was placed on a three-day paid suspension. The AmEx spokesman said she broke information-security policies by sending confidential company information to her personal email address.

Ms. Lewis said she did nothing wrong. She said she had sent an email to her personal account with information about a problematic sales call. She said she had also forwarded an email that she had written about sales problems to her personal account.

Ms. Lewis didn’t want to go back to the office. Exhausted and unnerved, she said, she filed for stress-related paid sick leave. AmEx granted it.

A couple of weeks later, Ms. Lewis learned that her performance rating for 2019 had plummeted. She doesn’t know why. During the first three quarters of 2019, Ms. Lewis was a top performer among small-business and corporate card sales managers, according to a company document.

Ms. Lewis said she tried to negotiate with AmEx through the Labor Department. She wanted to return, but only if her performance rating is revised. AmEx, she said, has declined.

Updated: 3-12-2020

JPMorgan Chase Settles In Suit Over Credit Card Crypto Purchases

The sixth-largest bank worldwide, JPMorgan Chase Bank, has settled a lawsuit over unannounced changes made to the fee structure applied to cryptocurrency purchases made using its credit cards in 2018. The details of the settlement have not been disclosed.

Plaintiffs Brady Tucker, Ryan Hilton, and Stanton Smith accused Chase Bank of violating its cardholder terms of service during January 2018.

The trio asserts that Chase applied the fee structure for cash advances to cryptocurrency purchases made with Chase’s credit cards for 10 days without providing any warning as to the change.

Chase Changes Fee Structure For Crypto Purchases Without Warning

During a previous hearing, Chase sought to argue that cryptocurrency purchases comprise “cash-like transactions” as per its terms of service, and as such, it did not breach its contract with cardholders.

However, in August, Judge Failla ruled that the trio had demonstrated a credible interpretation of “cash-like” as exclusively referring to financial instruments tied to fiat currency — such as traveler’s check and money orders, and cash.

Chase also claimed that the adjusted fee schedule was the result of crypto exchange Coinbase changing its merchant category code from “purchases” to “cash advances.”

Plaintiffs Sought $1 Million In Statutory Damages

Tucker originally filed the suit during April 2018. After the bank sought dismissal of the case in July 2018, Tucker filed an amended complaint alongside Smith and Hilton.

Claiming to represent a class of up potentially thousands of Chase Bank cardholders impacted by the unannounced changes, the plaintiffs sought full refunds of all charges wrongfully incurred in addition to $1 million in statutory damages.

All parties now have 75 days to submit their stipulations of settlement, otherwise, the plaintiffs can apply for the action to be restored.

JPMorgan Chase Targets Burgeoning Stablecoin Sector

Last month, JPMorgan Chase published a 74-page report examining the development and state of the blockchain industry.

While acknowledging that distributed ledger technologies had seen significant adoption for niche financial applications such as stock exchanges, the report concluded that mainstream blockchain adoption is still many years away.

Despite its predictions, America’s largest bank has moved quickly to capitalize on the recent boom in stablecoin interest.

During February 2019, JPMorgan Chase became the first U.S. bank to successfully test a stablecoin representing fiat currency after trialing its ‘JPM Coin’.

U.S. Sues UBS Over Mortgage Securities

The Swiss banking giant says it will contest the allegations.

The Justice Department on Thursday (11-11-2018) filed a civil suit against UBS Group AG over “catastrophic” losses incurred by investors from mortgage-linked securities sold in the run-up to the financial crisis in 2006 and 2007.

The lawsuit, which UBS has vowed to fight, will likely leave a legal cloud hanging over Switzerland’s largest bank for many months. It also serves as a reminder that, more a decade after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, some of the issues at the heart of the financial crisis have yet to be fully resolved.

“Investors who bought [residential mortgage-backed securities] from UBS suffered catastrophic losses, which not only caused direct harm to those investors, but also contributed to the financial crisis of 2008,” said U.S. Attorney Richard P. Donoghue.

In the complaint, the U.S. alleges that UBS misled investors about the quality of billions of dollars in subprime and other mortgage loans that were used to back 40 deals. UBS securitized more than $41 billion in mortgage loans through these deals, according to the complaint.

The government didn’t specify the damages that it was seeking, though it pegged the losses by investors as being “many billions of dollars.”

Earlier Thursday, prior to the announcement from U.S. authorities, UBS said it expected the lawsuit and would contest it.