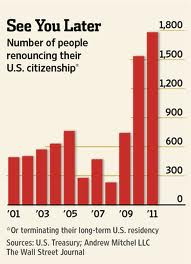

Number of Americans Renouncing Citizenship Surges To Escape Oppressive Financial Compliance And Tax Rules (#GotBitcoin)

A record 4,279 individuals renounced their U.S. citizenship or long-term residency in 2015, according to data released by the Treasury Department. Number of Americans Renouncing Citizenship Surges To Escape Oppressive Financial Compliance And Tax Rules (#GotBitcoin)

The Tools To Control The Masses Are Either To Print Money or Raise Taxes, That’s Pretty Much It!

Last year was the third year in a row for record renunciations, according to Andrew Mitchel, an international lawyer in Centerbrook, Conn., who tallies and tracks renunciation data. The Treasury Department renunciation list for the fourth quarter, which contained 1,058 names, was released on Friday.

Related Articles:

Reported US Citizenship Renunciations Nearly Triple In Q2

The Homes Where Families Go Off the Grid (#GotBitcoin?):

Dropping Off The Grid: A Growing Movement In America Part I

Dropping Off The Grid: A Growing Movement In America Part II:

Dropping Off The Grid: A Growing Movement In America Part III:

Dropping Off The Grid: A Growing Movement In America Part IV:

Who Is A Perpetual Traveler (AKA Digital Nomad) Under The US Tax Code

The Bitcoiners Who Live Off The Grid

“An increasing number of Americans appear to believe that having a U.S. passport or long-term residency isn’t worth the hassle and cost of complying with U.S. tax laws,” Mr. Mitchel said.

Experts say the growing number of renunciations by citizens and long-term holders of green cards is related to an enforcement campaign by U.S. officials against undeclared offshore accounts. It intensified in 2009, after Swiss banking giant UBS AG admitted that it encouraged U.S. taxpayers to hide money abroad.

Since then, the U.S. has collected more than $13.5 billion from individuals and foreign financial firms in taxes and penalties due on such accounts. This week, Swiss bank Julius Baer Group AG admitted it encouraged U.S. taxpayers to hide money abroad and agreed to pay $547 million to settle potential charges.

However, the campaign by U.S. officials also has complicated the financial lives of an estimated 7 million or more Americans living abroad, leading growing numbers to sever their U.S. ties.

Unlike many countries, the U.S. taxes nonresident citizens on income they earn abroad. According to Philip Hodgen, an international tax lawyer who practices in Pasadena, Calif., the law provides only partial offsets for double taxation when taxes are owed to both the U.S. and a foreign country, and complying with the law is onerous.

Mr. Mitchel adds that since 1995, the penalties for noncompliance by Americans living abroad who didn’t intentionally avoid filing common IRS forms have increased dramatically—in some cases from as little as $2,000 to as much as $70,000 annually.

IRS scrutiny of Americans abroad is also intensifying because of a new law known as Fatca, which requires foreign financial institutions to report income information for their customers who are U.S. taxpayers to the IRS, or else face severe penalties.

More than 180,000 foreign banks and other firms have signed up to comply with Fatca.

The Treasury Department is required by law to publish quarterly lists of people who renounce their citizenship or long-term residency. The list doesn’t distinguish between people turning in passports and those turning in green cards, or indicate which other nationality the individuals hold.

There is often a lag between when a person renounces and the government’s publication of his or her name. No information appears other than the name.

In the fiscal year ended Sept. 30, 2015, nearly 730,000 people became U.S. citizens, according to a spokesman for the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services division of the Department of Homeland Security.

U.S. Fee To Drop Citizenship Is Raised Fivefold

The fee for individuals to renounce U.S. citizenship is jumping to $2,350 as of Sept. 12—more than five times the current charge of $450.

The U.S. State Department, in its explanation for the increase, said that documenting a renunciation is “extremely costly” and requires a minimum of two intensive interviews with the applicant as well as other procedures.

The fees charged for a number of other services, such as “fiance(e) visas” and employment-based visa applications, increased far less than those for renunciation and in some cases declined.

The large increase in the renunciation fee comes at a time when record numbers of Americans living abroad are cutting ties with the U.S. Last year, 2,999 U.S. citizens and green-card holders renounced their allegiance to the U.S., a record number, and renunciations in 2014 are on track to exceed that.

The State Department estimates that 7.6 million Americans live abroad.

In its explanation of the fee increase, the State Department referred to the growth in renunciations, noting that since 2010 the demand has “increased dramatically, consuming far more consular time and resources.”

It also referred to a 2010 statement saying that the $450 fee was substantially less than what it cost to provide the service, adding that “there is no public benefit or other reason for setting this fee below cost.”

According to a State Department spokesman, the wait time for an expatriation interview has increased to as much as six months in some areas, while it is as short as two to four weeks in others.

He added that three-quarters of all renunciations are processed by consular offices in Canada, the U.K. and Switzerland.

Advocates for U.S. expatriates reacted angrily to news of the increase. “I’m so disappointed and insulted by the continuing punitive actions of the U.S. in trying to prevent persons and companies from leaving,” said Carol Tapanila, who was born in New York state but has lived in Canada for more than 40 years. She renounced her citizenship in 2012.

“The cost of U.S. tax lawyers, accountants and immigration lawyers made a good dent in our retirement savings. With these new fees, we would have had to take out a loan,” she added.

Helping boost the exodus of U.S. citizens, say experts, is a five-year old campaign by U.S. authorities to track down tax evasion by Americans hiding money abroad.

While the campaign has collected more than $6 billion in taxes, interest and penalties from 43,000 U.S. taxpayers, it has also swept up many middle-income Americans living abroad who pay taxes in their host country and say they weren’t trying to dodge U.S. taxes.

Scrutiny of these Americans by U.S. authorities is intensifying under the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, known as Fatca, which Congress passed in 2010.

The law’s main provisions took effect in July and require foreign financial firms to report income and account balances above certain thresholds to the Internal Revenue Service.

The heightened enforcement is prompting many to renounce their citizenship. While a renunciation doesn’t free them of taxes due for past years, these people don’t want to risk large tax bills for themselves and their children in the future

Record Numbers Living Abroad Renounce U.S. Citizenship over IRS Reporting Requirements.

Patricia Moon, shown in her Toronto home, renounced her U.S. citizenship after living abroad for three decades. Patricia Moon was born in Dayton, Ohio, to a family descended from Quakers who settled in the New World before the American Revolution.

As a young woman, Ms. Moon fell for a Canadian man and moved to Toronto. The 59-year-old homemaker, who still visits the U.S. to see relatives, said she feels American in her bones, even after three decades abroad.

Yet despite her deep roots, Ms. Moon walked into a U.S. consulate two years ago, raised her right hand and recited an oath renouncing her U.S. citizenship. Afterward, she said, “I bawled my eyes out.”

Ms. Moon is among record numbers of Americans cutting ties. U.S. offices abroad reported that 1,001 U.S. citizens and green-card holders had renounced their allegiance in the first three months of the year, according to Andrew Mitchel, a lawyer in Centerbrook, Conn., who analyzes Treasury Department data.

That figure puts 2014 on track to top last year’s total of 2,999 renunciations, he said, which was the most since the government began disclosing the data.

Helping boost the exodus, experts say, is a five-year-old U.S. campaign to hunt for undeclared accounts held by Americans abroad.

Since 2009, the government campaign has collected more than $6 billion in taxes, interest and penalties from more than 43,000 U.S. taxpayers.

Federal prosecutors have filed more than 100 criminal indictments, including the high-profile case of Beanie Babies inventor Ty Warner, who last year pleaded guilty to tax evasion involving secret Swiss bank accounts.

The tax dragnet has also swept up many middle-income Americans living abroad, prompting some to give up their U.S. citizenship.

While people who renounce aren’t freed of taxes due for past years, they don’t want to risk sizable taxes and penalties for them and their children in the years ahead, experts say.

Nearly 8,000 taxpayers have renounced U.S. citizenship in the past five years, Mr. Mitchel found, compared with fewer than 5,000 in the preceding decade.

“The increase is due to current and future changes in tax law and enforcement,” said Freddi Weintraub, a New York attorney at the Fragomen firm who specializes in immigration law. She said in recent years she has seen a threefold increase in expatriation inquiries related to taxes.

Ms. Moon, for example, feared the IRS could charge her family nearly a half-million dollars in penalties on undeclared savings and checking accounts—even though, she said, the accounts never held more than $102,000, weren’t intentionally hidden and didn’t have any U.S. taxes owed. “I was afraid we would have to cash in our retirement accounts and sell our home,” she said.

Experts say the U.S. campaign could affect millions of Americans like Ms. Moon—people who aren’t wealthy, pay taxes in their host country, and who say they weren’t trying to dodge U.S. taxes.

“We have reached the point where middle-class American citizens abroad are being forced to renounce—especially if they have assets and are moving toward retirement—because of taxes, paperwork and huge potential penalties,” said John Richardson, a Toronto lawyer with dual U.S. and Canadian citizenship.

He and Ms. Moon help run a nonprofit group seeking to keep Canada from sharing private account information with U.S. authorities.

As word spreads, experts said, more Americans are likely to consider surrendering their citizenship. The State Department estimates that 7.6 million American citizens live outside the U.S., but only a fraction file required financial disclosure forms.

Mark Mazur, the Treasury Department’s assistant secretary for tax policy, said the government’s new enforcement was intended to help make sure all taxpayers pay what they owe “regardless of where they live.”

At the same time, Mr. Mazur said, Treasury needs to “maintain a balance between enforcement efforts and equity, including the burdens that may be placed on taxpayers.”

Mr. Mazur said Treasury was looking into how best to work with Congress and the IRS to fine-tune the system: “You can always improve.”

U.S. officials launched their campaign after Swiss banking giant UBS admitted in 2009 that it helped wealthy American taxpayers hide money overseas.

To avoid criminal charges, the bank paid $780 million to the U.S. and turned over information on more than 4,400 accounts, ending decades of Swiss bank secrecy.

In May, Credit Suisse Group pleaded guilty to similar charges and agreed to pay $2.6 billion. Dozens of other Swiss banks are currently negotiating penalties with the U.S. Department of Justice, officials said.

Following the UBS revelations, U.S. officials announced they would begin vigorously enforcing both new and long-dormant tax rules.

Unlike other developed nations, the U.S. government taxes citizens on income they earn anywhere in the world. The rule dates to the Civil War, when Ms. Moon’s great-great grandfather served with Union forces.

U.S. tax liabilities also cover children born to Americans abroad, extending the reach of the IRS across generations, as well as oceans.

For decades, wealthy taxpayers were able to hide foreign assets in countries where bank-secrecy laws fostered attractive tax havens, including Switzerland, the Cayman Islands and Panama.

But the UBS case signaled the beginning of the end for such havens. Armed with information from the Swiss bank, U.S. authorities pursued individuals for back taxes, and pressured the tax professionals who helped them.

As a result of the crackdown, Ms. Moon and others learned they had failed to comply with the law. “We call it the ‘Oh, my God! moment.’ Every expatriate has it,” Ms. Moon said. “They were going to take every dime we had, that was my fear.”

The violations often don’t involve unpaid U.S. taxes on wages: The law currently exempts about $100,000 of income earned abroad each year. Ms. Moon, for example, didn’t owe any income tax.

She said she never made more than $11,000 a year when she worked from 2007 to 2012 as a bookkeeper for a business run by her husband, who earned about $65,000 a year devising special effects for movies and TV.

The most common mistakes usually involved Americans failing to submit a form called the Foreign Bank Account Report, or Fbar. Since 1970, U.S. taxpayers have been required to file if they held one or more foreign accounts totaling more than $10,000 over the course of a year. Until the enforcement push, many Americans never filed an Fbar.

The law is more than 40 years old, but “no one ever heard of it” before the crackdown, said Edward Kleinbard, a former chief of staff on Congress’ Joint Committee on Taxation, and an expert in international tax law at the University of Southern California.

FBAR penalties are as steep as 50% of the highest value of the account for each year no report was filed.

The IRS fined one taxpayer for Fbar violations in four separate years, and a settlement reached this month in the case yielded $1.7 million in penalties, which was more than the account held at the time.

Experts say the stiff penalties were originally enacted to discourage wealthy tycoons from hiding assets abroad.

In the fall of 2011, Ms. Moon learned she should have been filing Fbar forms on joint accounts she held with her husband. She calculated she could owe about $455,000 in penalties for the years she failed to file.

The IRS was unlikely to have imposed penalties that high, experts said, but it could have. “Getting professional help to correct her mistakes could easily have cost $15,000 to $20,000,” said Bryan Skarlatos, a lawyer with Kostelanetz & Fink in New York, which has advised thousands of taxpayers with secret offshore accounts.

Ms. Moon considered what to do. One of the IRS’s limited-amnesty programs had just ended and a new one didn’t start until 2012. She said she wouldn’t have entered a program in any case because she considered Fbar penalties too steep for “failing to file a piece of paper.” Penalties and other costs can amount to a third of the balance in an account or more.

“The programs are best for people who have done things serious enough to land them in prison and are willing to pay huge penalties to stay out,” said Philip Hodgen, an international tax lawyer in Pasadena, Calif.

Americans with smaller offshore accounts who entered the first IRS limited amnesty program paid proportionately higher penalties than taxpayers with larger accounts, according to Nina Olson, the National Taxpayer Advocate, an IRS ombudsman.

The typical taxpayer with less than $45,000 in undeclared accounts paid nearly six times the back taxes owed, while the typical taxpayer with more than $7 million in such accounts paid closer to three times their back taxes, Ms. Olson found.

IRS officials “didn’t think about the demographics of the population” of overseas Americans, Ms. Olson said, often treating middle-class taxpayers the same as “bad actors.”

“There’s an awful lot of minnows caught up in this,” said Marvin Van Horn, a 66-year-old retired financial controller for Alaska Airlines. He said he entered an IRS limited-amnesty program in 2009: “I assumed it would be very clear I was not one of those quote-unquote offshore tax cheats, those big whales they were looking for.”

In prior U.S. tax filings, Mr. Van Horn said he hadn’t declared rental income from a house he and his Australian wife own in New Zealand, as well as interest income. He said he didn’t know such declarations were required.

“I have to take some responsibility,” Mr. Van Horn said. “It was stupidity and not paying attention on my part.”

The IRS fined him more than $172,000, roughly eight times his back taxes, which amounted to about $21,000 over six years, Mr. Van Horn said. With help from Ms. Olson’s office, he said, the fine was reduced to about $25,000. Spokesmen for the IRS and Ms. Olson said they couldn’t comment on individual cases.

In a June 3 speech, IRS Commissioner John Koskinen said the agency may not have been accommodating enough to U.S. citizens who have lived abroad for years.

“We have been considering whether these individuals should have an opportunity to come into compliance that doesn’t involve the type of penalties that are appropriate for U.S.-resident taxpayers who were willfully hiding their investments overseas,” he said.

Scrutiny of Americans abroad will intensify, however, under the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, or Fatca, which Congress passed in 2010.

The law’s main provisions, which take effect in July, will require foreign financial institutions to report income of their U.S. customers to the IRS, much as U.S. banks and brokers file 1099 forms.

Middle-class Americans “face overwhelming problems when they try to engage in standard financial practices, such as having a small business, saving for retirement, investing, buying life insurance, and making wills and trusts,” because of the laws governing assets abroad, said David Kuenzi, a financial planner with Thun Financial Advisors in Madison, Wis., who works with expatriates.

The U.S. tax code, for example, doesn’t recognize Australia’s version of an individual retirement account, Mr. Kuenzi said. American taxpayers with these accounts must file at least two forms a year declaring the account a “foreign trust,” and paying taxes on annual appreciation.

The penalty for failing to file can be as much as 35% of both contributions and withdrawals each year, plus 5% of the assets, said Mr. Hodgen, the Pasadena tax lawyer.

Ms. Moon learned that U.S. law requires her to file annual reports on retirement accounts, such as her Tax-Free Savings Account—similar to a Roth IRA.

Her husband, Ken Whitmore, objected to divulging financial information on joint accounts to the IRS. “Would you want the Canada revenue service to know what your financial situation is?” he said.

Ms. Moon concluded that even if the IRS didn’t levy the stiffest fines, the potential consequences down the road for missing a deadline or making a mistake were too costly.

She later learned she would have been required to pay U.S. taxes on part of the gain on the couple’s Toronto house, which they hope to sell for a retirement nest egg.

They bought the house in the mid-1980s for $125,000, she said, and it was now worth an estimated $800,000.

Before renouncing her citizenship, Ms. Moon spoke with her sister, Sue Moon, a certified public accountant in Kansas City, Mo.

“U.S. citizenship is the most coveted citizenship in the world. To give it up, it has to be pretty serious,” Sue Moon said. “There was just a sadness on her part, that she had to make that decision. She didn’t take it lightly.”

Months after Ms. Moon renounced her citizenship, her official notice arrived in Toronto. Ms. Moon went to the U.S. consulate to pick it up and paid a $450 processing fee. She told the clerk it was “the saddest $450 I’ll ever spend.”

The number of U.S. taxpayers renouncing citizenship or permanent-resident status surged to a record high in the second quarter, as new laws aimed at cracking down on overseas assets increase the cost of complying and the risk of a taxpayer misstep.

A total of 1,130 names appeared on the latest list of renunciations from the Internal Revenue Service, according to Andrew Mitchel, a tax lawyer in Centerbrook, Conn., who tracks the data.

That is far above the previous high of 679, set in the first quarter, and more than were reported in all of 2012.

Taxpayers aren’t required to explain the move, but experts said the recent rise is likely due to tougher laws and enforcement.

“The IRS crackdown on U.S. taxpayers living abroad seems to be having an effect,” said Mr. Mitchel.

The IRS Declines Comment

Lags in reporting renunciations might mean that many who appeared on the current list made the move months earlier. Taxpayers who renounced can be subject to an exit tax, and people who renounced last year may have avoided higher taxes on capital gains and income that went into effect in 2013.

The U.S. is rare in that all income earned by citizens and permanent residents, even those living abroad, can be subject to U.S. tax, according to Bryan Skarlatos, a New York lawyer. The U.S. also confers citizenship on people who are born on American soil.

The U.S. launched the tax crackdown after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, and ratcheted up its efforts after 2009, amid evidence that UBS AG and other foreign institutions helped U.S. taxpayers hide assets.

Some taxpayers have applied for IRS limited-amnesty programs, in which they pay stiff penalties for past noncompliance but avoid prosecution.

Tax lawyers say the crackdown has ensnared smaller violators who weren’t intentionally evading U.S. taxes.

In addition, a law enacted in 2010, the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, or Fatca, requires foreign financial institutions to certify they aren’t hiding U.S. taxpayer assets, which lawyers say is leading some to reject U.S. customers.

Taxpayer penalties for failing to report assets can be severe, including up to 50% of an account balance for each year.

The web of rules is “overly burdensome,” said Jeffrey Neiman, a former federal prosecutor who led the 2009 UBS case, which resulted in the bank’s agreeing to a $780 million settlement.

He now is a lawyer in private practice in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. “You basically find yourself in this continuous nightmare.”

The cost of complying with various rules and regulations can be steep even for people with small tax bills.

Carol Tapanila, who moved to Canada more than 40 years ago and is now retired, renounced her citizenship in November and appeared on the current list. She says her U.S. taxes amounted to about $250 last year and she didn’t take the step to avoid paying them.

Legal and accounting fees and other costs of making sure she was in compliance in recent years have added up to nearly $40,000, says Ms. Tapanila. “It is nothing but stress.”

Expatriation can also be costly, requiring that taxpayers prove they have properly paid five years’ taxes, among other things.

Countries With And Without Income Tax Treaties With The U.S.

1) AFRICA

| Country | Income Tax Treaty with U.S.? (Yes/No) |

| Algeria | No |

| Angola | No |

| Benin | No |

| Botswana | No |

| Burkina Faso | No |

| Burundi | No |

| Côte d’Ivoire | No |

| Cape Verde | No |

| Cameroon | No |

| Central African Republic | No |

| Chad | No |

| Comoros | No |

| Congo | No |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | No |

| Dijbouti | No |

| Egypt | Yes |

| Guinea | No |

| Guinea-Bissau | No |

| Equatorial Guinea | No |

| Eritrea | No |

| Ethopia | No |

| Gabon | No |

| Gambia | No |

| Ghana | No |

| Kenya | No |

| Lesotho | No |

| Liberia | No |

| Libya | No |

| Madagascar | No |

| Malawi | No |

| Mali | No |

| Mauritania | No |

| Mauritius | No |

| Morocoo | Yes |

| Mozambique | No |

| Namibia | No |

| Niger | No |

| Nigeria | No |

| Rwanda | No |

| Sao Tome and Principe | No |

| Senegal | No |

| Seychelles | No |

| Sierra Leone | No |

| Somalia | No |

| South Africa | Yes |

| Sudan | No |

| Swaziland | No |

| Tanzania | No |

| Togo | No |

| Tunisia | Yes |

| Uganda | No |

| Zambia | No |

| Zimbabwe | No |

2) ASIA

| Country | Income Tax Treaty with U.S.? (Yes/No) |

| Afghanistan | No |

| Armenia | Yes |

| Azerbaijan | Yes |

| Bahrain | No |

| Bangladesh | Yes |

| Bhutah | No |

| Brunei | No |

| Cambodia | No |

| China | Yes |

| Georgia | Yes |

| India | Yes |

| Indonesia | Yes |

| Iran | No |

| Iraq | No |

| Israel | Yes |

| Japan | Yes |

| Jordan | No |

| Kazakhstan | Yes |

| Kuwait | No |

| Kyrgyzstan | Yes |

| Laos | No |

| Lebanon | No |

| Malaysia | No |

| Maldives | No |

| Mongolia | No |

| Myanmar (Burma) | No |

| Nepal | No |

| North Korea | No |

| Oman | No |

| Pakistan | Yes |

| Philippines | Yes |

| Qatar | No |

| Russia | Yes |

| Saudi Arabia | No |

| Singapore | No |

| South Korea | Yes |

| Sri Lanka | Yes |

| Syria | No |

| Tajikistan | Yes |

| Thailand | Yes |

| Timor-Leste (East Timor) | No |

| Turkey | Yes |

| Turkmenistan | Yes |

| United Arab Emirates | No |

| Uzbekistan | Yes |

| Vietman | No |

| Yemen | No |

3) AUSTRALIA AND OCEANIA

| Country | Income Tax Treaty with U.S.? (Yes/No) |

| Australia | Yes |

| Fiji Islands | No |

| Kiribati | No |

| Marshall Islands | No |

| Micronesia | No |

| Nauru | No |

| New Zealand | Yes |

| Palau | No |

| Papua New Guinea | No |

| Samoa | No |

| Solomon Islands | No |

| Tonga | No |

| Tuvalu | No |

| Vanuatu | No |

4) EUROPE

| Country | Income Tax Treaty with U.S.? (Yes/No) |

| Albania | No |

| Andorra | No |

| Austria | Yes |

| Belarus | Yes |

| Belgium | Yes |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | No |

| Bulgaria | Yes |

| Croatia | No |

| Cyprus | Yes |

| The Czech Republic | Yes |

| Denmark | Yes |

| Estonia | Yes |

| Finland | Yes |

| France | Yes |

| Germany | Yes |

| Greece | Yes |

| Hungary | Yes |

| Iceland | Yes |

| Ireland | Yes |

| Italy | Yes |

| Kosovo | No |

| Latvia | Yes |

| Liechtenstein | No |

| Lithuania | Yes |

| Luxembourg | Yes |

| Macedonia | No |

| Malta | No |

| Moldova | Yes |

| Monaco | No |

| Montenegro | No |

| The Netherlands | Yes |

| Norway | Yes |

| Poland | Yes |

| Portugal | Yes |

| Romania | Yes |

| Russia | Yes |

| San Marino | No |

| Serbia | No |

| Slovakia | Yes |

| Slovenia | Yes |

| Spain | Yes |

| Sweden | Yes |

| Switzerland | Yes |

| Turkey | Yes |

| Ukraine | Yes |

| United Kingdom | Yes |

| Vatican City | No |

5) NORTH AMERICA

| Country | Income Tax Treaty with U.S.? (Yes/No) |

| Antigua and Barbuda | No |

| Bahamas | No |

| Barbados | Yes |

| Belize | No |

| Canada | Yes |

| Costa Rica | No |

| Cuba | No |

| Dominica | No |

| Dominican Republic | No |

| El Salvador | No |

| Grenada | No |

| Guatemala | No |

| Haiti | No |

| Honduras | No |

| Jamaica | Yes |

| Mexico | Yes |

| Nicaragua | No |

| Panama | No |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | No |

| Saint Lucia | No |

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | No |

| Trinidad and Tobago | Yes |

6) SOUTH AMERICA

| Country | Income Tax Treaty with U.S.? (Yes/No) |

| Argentina | No |

| Bolivia | No |

| Brazil | No |

| Chile | No |

| Colombia | No |

| Ecuador | No |

| Guyana | No |

| Paraguay | No |

| Peru | No |

| Suriname | No |

| Uruguay | No |

| Venezuela | Yes |

I.R.S. Goes After Small Businesses

Thousands of small-business owners have received letters from the Internal Revenue Service questioning whether they are underreporting their business income, a harbinger of a broader initiative aimed at boosting federal tax receipts and ensuring compliance.

The program is the latest move in the agency’s effort to combat what it sees as a widespread problem: failure by businesses, including mom-and-pops, to report all cash sales in order to minimize tax bills.

Tax officials say the letters don’t constitute an audit and instead are simply a request for more information. Some business owners and some lawmakers, however, call the new IRS program alarming.

“There’s an emotional thing when you get a pretty ominous-looking letter from the IRS, [saying] you might have done some bad things,” said Tom Reese, owner of Hearing Well Inc., which operates a small chain of stores that fit and sell hearing aids in eastern Tennessee, who received a letter in recent weeks. “I really work hard with my accountant to make sure that I not only follow the law, but follow the letter of the law.”

The IRS says it is sending out about 20,000 letters to business owners as the program cranks up. While that is a small portion of the total number of U.S. small businesses, which is estimated in the millions, some tax accountants say they expect the program to expand.

Roger Harris, president of Padgett Business Services, a nationwide accounting firm that specializes in small businesses, said the letters have “created some heartache in the small business community.”

The IRS program stems from a 2008 change in the law that gave the agency broader access to merchants’ credit- and debit-card transaction records. The IRS has been comparing the data to information that small businesses report on their tax returns.

If the data suggest an unusually large percentage of a business’s receipts come from card transactions, the IRS might send a letter asking the business owner to explain why cash receipts seem relatively low.

Underreporting of income comprises the majority of the so-called “tax gap,” the difference between what Americans owe and pay, according to IRS data. In 2006, the most recent year available, the total tax gap was $450 billion.

Underreporting accounted for $376 billion of that total, and underreported small-business income totaled at least $141 billion.

One typical letter to a small-business owner is headlined, “Notification of Possible Income Underreporting.” It begins, “Your gross receipts may be underreported.”

The letter instructs the owner to complete a form “to explain why the portion of your gross receipts from non-card payments appears unusually low.” It says the business owner must respond within 30 days.

“The letter implies that this is a serious matter that could lead to assessments of additional tax, penalties and interest,” says a letter sent to the IRS Friday by Rep. Sam Graves (R., Mo.), chairman of the House Small Business Committee.

The IRS is now the target of a series of congressional investigations into its giving extra scrutiny to conservative groups seeking tax-exempt status.

Fran Coet, who runs an accounting business in Westminster, Colo., says the new IRS practice will cause a lot of fear among small businesses because it can often be difficult to match credit transactions with income.

“There are so many reasons why, even if you’re the most honest tax payer, you’re not going to match” what card records show, says Ms. Coet, whose company advises about 250 small businesses. Ms. Coet cited sales of gift cards, which for accounting purposes don’t count as a sale, but look that way to a credit-card company.

There are legitimate reasons why a business might report relatively high proportions of card receipts versus cash receipts. Card receipt totals can include cash that the customer takes back. Mr. Reese said his hearing aids carry price tags of $1,000 or more, which encourages clients to use cards.

Peter Fleming, a small-business accountant in Carnegie, Pa., said a client with a gift and souvenir shop received a letter from the IRS in December saying the revenue she claimed in tax returns the previous year was lower than sales reported in merchant card and third-party payments data.

The retailer reported gross receipts of $243,462, versus $249,994 in the payment data, according to the IRS. The letter told her to ensure she was “fully reporting receipts from all sources” and gave her 30 days to respond.

Mr. Fleming said the discrepancy was because payments data included sales tax, which wasn’t included in revenue claimed in tax returns. For small retailers, “Sales tax is a liability and is not reported as revenue,” Mr. Fleming said.

The IRS in a statement said the agency is “taking its first early steps” in using the new data, and promised “to carefully review the results of these initial steps.” It said the agency is “working diligently to minimize burden on both taxpayers and tax professionals.”

The agency defended its approach as “measured and equitable in several ways, including giving taxpayers the opportunity to explain and fix errors.” It added: “An important component of this project is [to] help ensure that people who are non-compliant don’t get an unfair advantage over those that play by the rules and follow the law.”

The IRS has told accountants that a principal aim of its program is to verify the quality of the card-transaction data the agency is getting.

Famous Americans Who Renounced U.S. Citizenship

Most Chose Renunciation To Avoid Paying Their Tax Bills

Renunciation of U.S. citizenship is an extremely serious matter that the federal government handles carefully.

Section 349(a)(5) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) governs renunciations. The U.S. Department of State oversees the process. An individual who seeks renunciation must appear in person at a U.S. embassy or consulate outside the United States.

The petitioner, in effect, forfeits the right to be in the United States and to travel freely here, and also the other rights of citizenship. Since the Great Recession of 2007, renunciations have increased as more U.S. citizens have tried to avoid taxes by giving up their citizenship and moving overseas.

Eduardo Saverin, Co-Founder of Facebook

Eduardo Saverin, the Brazilian internet entrepreneur who helped Mark Zuckerberg found Facebook, caused a stir before the company went public in 2012 by renouncing his U.S. citizenship and taking up residency in Singapore, which does not permit dual citizenship.

Saverin gave up being an American to save millions in taxes from his Facebook fortune. He was able to avoid capital gains taxes on his Facebook stock but was still liable for federal income taxes.

But he also faced an exit tax — the estimated capital gains from his stock at the time of renunciation in 2011.

In the award-winning movie The Social Network, Saverin’s role was played by Andrew Garfield.

Denise Rich, Grammy-Nominated Song-Writer

Denise Rich, 69, is the ex-wife of billionaire Wall Street investor Marc Rich, who was pardoned by President Bill Clinton after fleeing to Switzerland to avoid prosecution for tax evasion and profiteering allegations.

She has written songs for a dazzling list of recording artists: Mary J. Blige, Aretha Franklin, Jessica Simpson, Marc Anthony, Celine Dion, Patti LaBelle, Diana Ross, Chaka Khan and Mandy Moore. Rich has received three Grammy nominations.

Rich, who was born Denise Eisenberg in Worcester, Mass., moved to Austria after leaving the United States. Her ex-husband Marc died in June 2013 at the age of 78.

Ted Arison, Owned Carnival Cruise Lines and Miami Heat

Ted Arison, who died in 1999 at the age of 75, was an Israeli businessman, who was born as Theodore Arisohn in Tel Aviv.

After serving in the Israeli military, Arison moved to the United States and became a U.S. citizen to help launch his business career. He founded Carnival Cruise Lines and earned a fortune as it grew to be one of the biggest in the world.

He became one of the richest people in the world. Arison brought a National Basketball Association franchise, the Miami Heat, to Florida in 1988.

Two years later, he renounced his U.S. citizenship to avoid estate taxes and returned to Israel to start an investment business. His son Micky Arison is Carnival’s chairman of the board and current owner of the Heat.

John Huston, Movie Director and Actor

In 1964, Hollywood director John Huston gave up his U.S. citizenship and moved to Ireland. He said he had come to appreciate Irish culture more than that in America.

“I shall always feel very close to the United States,” Huston told the Associated Press in 1966, “and I shall always admire it, but the America I know best and loved best doesn’t seem to exist anymore.”

Huston died in 1987 at the age of 81. Among his film credits are The Maltese Falcon, Key Largo, The African Queen, Moulin Rouge and The Man Who Would Be King. He also won praise for his acting in the 1974 film noir classic Chinatown.

According to family members, daughter Anjelica Huston in particular, Huston despised life in Hollywood.

Jet Li, Chinese Actor and Martial Artist

Jet Li, the Chinese martial arts actor and film producer, renounced his U.S. citizenship in 2009 and moved to Singapore. Multiple reports said Li preferred the education system in Singapore for his two daughters.

Among his film credits are Lethal Weapon 4, Romeo Must Die, The Expendables, Kiss of the Dragon, and The Forbidden Kingdom.

Taxpayers Are Pressured To Keep Good Records

Meanwhile, The IRS Loses Lerner’s Emails

The IRS—remember those jaunty folks?—announced Friday that it can’t find two years of emails from Lois Lerner to the Departments of Justice or Treasury. And none to the White House or Democrats on Capitol Hill. An agency spokesman blames a computer crash.

Never underestimate government incompetence, but how convenient. The former IRS Director of Exempt Organizations was at the center of the IRS targeting of conservative groups and still won’t testify before Congress.

Now we’ll never know whose orders she was following, or what directions she was giving. If the Reagan White House had ever offered up this excuse, John Dingell would have held the entire government in contempt.

The suspicion that this is willful obstruction of Congress is all the more warranted because this week we also learned that the IRS, days before the 2010 election, shipped a 1.1 million page database about tax-exempt groups to the FBI.

Why? New emails turned up by Darrell Issa’s House Oversight Committee show Department of Justice officials worked with Ms. Lerner to investigate groups critical of President Obama.

How out of bounds was this data dump? Consider the usual procedure. The IRS is charged with granting tax-exempt status to social-welfare organizations that spend less than 50% of their resources on politics.

If the IRS believes a group has violated those rules, it can assign an agent to investigate and revoke its tax-exempt status. This routinely happens and isn’t a criminal offense.

Ms. Lerner, by contrast, shipped a database of 12,000 nonprofit tax returns to the FBI, the investigating agency for Justice’s Criminal Division.

The IRS, in other words, was inviting Justice to engage in a fishing expedition, and inviting people not even licensed to fish in that pond.

The Criminal Division (rather than the Tax Division) investigates and prosecutes under the Internal Revenue Code only when the crimes involve IRS personnel.

The Criminal Division knows this, which explains why the emails show that Ms. Lerner was meeting to discuss the possibility of using different statutes, specifically campaign-finance laws, to prosecute nonprofits.

A separate email from September 2010 shows Jack Smith, the head of Justice’s Public Integrity Unit (part of the Criminal Division) musing over whether Justice might instead “ever charge a 371” against nonprofits.

A “371” refers to a section of the U.S. Code that allows prosecutors to broadly claim a conspiracy to defraud the U.S. You know, conspiracies like exercising the right to free political speech.

The IRS has admitted that this database included confidential taxpayer information—including donor details—for at least 33 nonprofits. The IRS claims this was inadvertent, and Justice says neither it nor the FBI used any information for any “investigative purpose.”

This blasé attitude is astonishing given the law on confidential taxpayer information was created to prevent federal agencies from misusing the information. News of this release alone ought to cause IRS heads to roll.

The latest revelations are a further refutation of Ms. Lerner’s claim that the IRS targeting trickled up from underlings in the Cincinnati office. And they strongly add to the evidence that the IRS and Justice were motivated to target by the frequent calls for action by the Obama Administration and Congressional Democrats.

One email from September 21, 2010 shows Sarah Hall Ingram, a senior IRS official, thanking the IRS media team for their work with a New York Times reporter on an article about nonprofits in elections.

“I do think it came out pretty well,” she writes, in an email that was also sent to Ms. Lerner. “The ‘secret donor’ theme will continue—see Obama salvo and today’s [radio interview with House Democratic Rep. Chris Van Hollen ].”

Several nonprofit groups have recently filed complaints with the Senate Ethics Committee against nine Democratic Senators for improperly interfering with the IRS. It’s one thing for Senators to ask an agency about the status of a rule or investigation.

But it is extraordinary for Illinois’s Dick Durbin to demand that tax authorities punish specific conservative organizations, or for Michigan’s Carl Levin to order the IRS to hand over confidential nonprofit tax information.

And it’s no surprise to learn that Justice’s renewed interest in investigating nonprofits in early 2013 immediately followed a hearing by Rhode Island Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse in which he dragged in officials from Justice and the IRS and demanded action.

It somehow took a year for the IRS to locate these Lerner exchanges with Justice, though they were clearly subject to Mr. Issa’s original subpoenas.

The Oversight Committee had to subpoena Justice to obtain them, and it only knew to do that after it was tipped to the correspondence by discoveries from the watchdog group Judicial Watch. Justice continues to drag its feet in offering up witnesses and documents.

And now we have the two years of emails that have simply vanished into the government ether.

New IRS Commissioner John Koskinen promised to cooperate with Congress. But either he is being undermined by his staff, or he’s aiding the agency’s stonewalling.

And now that we know that Justice was canoodling with Ms. Lerner, its own dilatory investigation becomes easier to understand. Or maybe that was a computer crash too.

Updated: August 6th, 2014

Fewer Americans Renounced Their Citizenship in the Second Quarter

The number of people renouncing their U.S. citizenship or ending long-term U.S. residency fell in the second quarter, compared with the first three months of 2014.

The total number of renunciations was 576, down from 1,001 in the first quarter, according to Andrew Mitchel, an international tax lawyer in Centerbrook, Conn. He tracks the data based on lists published by the Treasury Department that give the names of people who renounced their U.S. citizenship or turned in certain green cards. The list for the second quarter was published today.

Mr. Mitchel notes that the total for 2014 is still on pace to equal or exceed the record set in 2013, when nearly 3,000 people turned in U.S. passports or green cards.

There is often a lag between when a person renounces and the government’s publication of his or her name. No information other than the name appears on the Treasury Department list, such as where the person currently lives or what other nationality he or she has. An estimated 7.6 million U.S. citizens live abroad.

According to Mr. Mitchel’s data, nearly 8,000 taxpayers have renounced U.S. citizenship in the past five years, compared with fewer than 5,000 in the preceding decade.

Helping boost the exodus, experts say, is a five-year-old campaign to hunt for undeclared accounts held by U.S. taxpayers abroad. U.S. officials launched the campaign after Swiss banking giant UBS admitted in 2009 that it helped wealthy American taxpayers hide money overseas.

Unlike other developed nations, the U.S. taxes citizens and green-card holders who live abroad on income they earn anywhere in the world. The rule dates to the Civil War.

Updated: 9-12-2020

Unbecoming American

President Trump hosted a televised naturalization ceremony at the White House, aired during the Republication National Convention.

“You’ve earned the most prized, treasured, cherished, and priceless possession anywhere in the world,” he told the five new United States citizens. “It’s called American citizenship.”

Prized? Perhaps. But maybe not priceless.

A record number of Americans are renouncing their citizenship. In just the first half of this year, 5,315 Americans gave up their citizenship. That puts the country on track to see a record-breaking 10,000 people renounce U.S. citizenship in 2020. Until a decade ago, fewer than 1,000 Americans per year, on average, chose to renounce their citizenship.

Why are so many people abandoning the United States?

The Financial Factor

While many liberal Americans threatened to move abroad after Trump’s election in 2016, rising renunciations are not directly attributable to any particular election result. The trend began in 2013, midway through the Obama administration. That year about 3,000 Americans suddenly gave up their passports — three times more than usual.

Nor are people fleeing the U.S. because of the coronavirus. The paperwork for the 5,315 renunciations completed so far this year began long before COVID-19 ravaged the country and made Americans global pariahs.

In fact, most Americans giving up their U.S. passport already live abroad and hold another citizenship. In surveys and testimonials, these people say they’re dropping their U.S. citizenship because American anti-money-laundering and counterterrorism regulations make it too onerous and expensive to keep.

In 2010, Congress passed the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, which requires foreign financial institutions to report assets held abroad by U.S. citizens and green card holders.

The law, intended to identify the non-U. S. assets of all taxpayers, also ended up strengthening a 1970 anti-money-laundering law, the Foreign Bank Account Report, which requires citizens to declare all foreign assets to the U.S. Treasury Department.

Together, these two regulations represent a major burden for low-income and middle-income expatriates. Until 2010, they could basically ignore or remain ignorant of the Foreign Bank Account Report because there was little chance the U.S. government would discover their noncompliance.

They weren’t avoiding taxes. Of the roughly 9 million U.S. citizens living abroad, most don’t earn enough to owe Uncle Sam a dollar. Only expatriates who make over $107,600 in foreign income are required to pay U.S. taxes.

According to a 2018 survey by InterNations, an expatriates’ networking organization, the education sector is the largest employer of Americans living abroad, at 29%. Few educators make six figures. In the U.S., the average teacher earns $60,000. In most other countries, it’s even less.

Still, all American expats — even those who’ve lived abroad for decades, earn no income in the U.S., and hold no U.S. assets — must submit an annual tax return to the Internal Revenue Service.

Now, ever since Congress strengthened anti-money-laundering and counterterrorism financial reporting requirements, many have had to hire costly international accounting firms to do their taxes.

The consequences of noncompliance are severe: forfeiting up to 50% of all undeclared assets held overseas

Unbecoming American

“Becoming American” is a favorite topic in U.S. literature, popular history and the media. There are entire sections of university libraries devoted to books and studies on the topic. My first book, about how ordinary American citizens shaped early American national identity, will soon be among them.

However, there is very little written about the reverse: unbecoming American.

Renouncing U.S. citizenship is pretty complicated and costly. It involves one or two interviews with a consular officer, a $2,350 administrative fee — very expensive compared to other wealthy countries — and potential audit of the citizen’s last five years of U.S. tax returns.

The whole process takes about a year. Once you have successfully unbecome American, you need to submit a tax return to the IRS the year after renouncing. After that, your ties to the U.S. government are severed.

The formal, bureaucratic process of unbecoming American resembles the process of becoming American. By the time those five new citizens were naturalized at August’s virtual Republican Convention, they had been U.S. residents for at least five years and spent the past 12 to 18 months filing paperwork, scanning their fingerprints, and studying for a civics test.

Early in American history, though, citizenship was clumsy, informal, and changeable.

Colonists during the Revolutionary War often switched their allegiance, declaring themselves Patriots or Loyalists, depending on personal circumstances or which army controlled their town at the time, according to historian Donald F. Johnson in his forthcoming book “Occupied America.”

National identity was still in flux after the war. It was often unclear who was actually a citizen. Sailors, in particular, were frequently challenged on their status because many looked and sounded indistinguishable from the British when at sea or in foreign ports, wrote Nathan Perl-Rosenthal in his 2015 book “Citizen Sailors.”

One of the sailors I researched for my book, James L. Cathcart, regularly changed national allegiances to improve his fortunes. By my count, he switched identities or allegiances eight times by the time he turned 29, in 1796.

Born in Ireland, Cathcart fought for both sides in the American Revolution. Then when captured by Algerian corsairs in 1785, he spent a decade in captivity wavering between calling himself British or American, depending upon which offered the best hope of ransom.

During captivity in Algiers he was also made a senior bureaucrat, advising and representing the interests of the ruler of 18th-century Algiers.

Goodbye, America

The confusion over identifying American sailors eventually inspired the documentation and bureaucracy that would ultimately be used to determine U.S. citizenship for all.

As this history shows, the notion of American citizenship as the “most prized, treasured, cherished, and priceless possession” is a relatively recent invention. And it may not be permanent.

With 10,000 U.S. passports expected to be dumped this year and another 23% of American expats — about 2 million people — saying they are “seriously considering” renouncing citizenship, unbecoming American is starting to sound as American as apple pie.

Updated: 11-24-2020

Rich Americans Are Increasingly Looking For Second Passports

Eric Schmidt acquired all the typical trappings of a mega-rich U.S. citizen: a superyacht, a Gulfstream jet, a Manhattan penthouse.

One of his newest assets is far less conventional: a second passport.

Alphabet Inc.’s former chief executive officer applied to become a citizen of Cyprus, according to an announcement last month in a Cypriot newspaper that was first reported by the website Recode. Schmidt, 65, joins a growing club of individuals participating in government programs enabling foreigners to acquire passports.

In previous years, U.S. citizens rarely sought to buy so-called golden passports. The business mainly thrived targeting people from countries with fewer travel freedoms than the U.S., such as China, Nigeria or Pakistan.

But that’s changing. People close to the industry say they’ve been inundated with inquiries from citizens of the world’s richest country.

“We haven’t seen the likes of this before,” said Paddy Blewer, a London-based director at citizenship and residency-advisory firm Henley & Partners, referring to queries from U.S. individuals. “The dam actually burst — and we didn’t realize it — at the end of last year, and it’s just continued getting stronger.”

A spokeswoman for Cyprus’s government declined to comment. Representatives for Schmidt — who is worth $19 billion according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index — didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The benefits of owning a second passport, which range from potentially lower taxes, to more investing freedoms and less hassle traveling, can be had for as little as $100,000.

The so-called citizenship-by-investment programs haven’t historically been as popular with Americans since one of their main draws — the favorable tax regimes of adopted countries — has been of little benefit to citizens of the U.S., one of the few nations to tax its people regardless of where they live.

The current heightened interest among U.S. citizens predates the coronavirus pandemic, but the crisis has helped turbo-charge demand as they plan for how to maintain some freedom of movement with lockdown measures increasing amid a swelling second wave of Covid-19 cases.

“Americans are thinking: ‘I want to have that ability to move as quickly as possible and not be stuck,’” said Nestor Alfred, chief executive officer of St. Lucia’s citizenship-by-investment unit.

U.S. Elections

The U.S. elections have also stoked interest. While Joe Biden has rejected the wealth tax pushed by some of his Democratic primary rivals, his proposals could disrupt the ways that many Americans minimize — or altogether avoid — taxes on their investment gains.

Some have also looked to get an additional passport due to fears of social unrest, according to citizenship advisory firm Apex Capital Partners, which said inquiries from clients — typically about five a year — have increased 650% since this month’s vote.

“We’re seeing this interest from Americans who are all saying the same things that Chinese, or Middle Eastern or Russian clients are saying,” Apex founder Nuri Katz said in an interview. “They’re saying, ‘We’re not leaving the U.S. right now, but we’re concerned and we want to have something else, just in case.’”

St. Kitts and Nevis was the first country to introduce a citizenship-by-investment program in the early 1980s, and more than half-a-dozen nations have since done the same. In many cases, they’ve proved lucrative.

Malta raised almost $1 billion through June 2019 after launching its program last decade, while the Caribbean territory of Dominica has raised more than $350 million in the past five years.

The industry has generated plenty of consternation for effectively turning citizenship — usually obtained from birthplace or heritage — into something that can be purchased.

It has also attracted scandal. Fugitive Malaysian financier Jho Low was among 26 individuals to lose their Cyprus citizenship last year. The speaker of the Cypriot House of Parliament, Demetris Syllouris, resigned last month after offering to help a Chinese businessman with a criminal record get citizenship.

‘Talking Points’

“European values are not for sale,” European Union Justice Commissioner Didier Reynders tweeted last month.

Following the scandal, Cyprus said it would end its current passport-for-investment program on Nov. 1. The European Union, meanwhile, issued legal ultimatums to Malta and Cyprus about their citizenship-by-investment programs, claiming they may have violated the EU law.

Representatives for Malta’s government, which announced plans to revise its program before the EU’s action, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

It’s unclear whether interest among Americans in reducing exposure to their home country will endure when the pandemic and post-election uncertainty have abated.

After an election, “we always have an uptick in emotion,” said Sherwin Simmons, principal at tax advisory firm Asgard Worldwide, adding he’s recently fielded increased inquiries from wealthy clients about renouncing U.S. citizenship, a complex process that involves a steep exit tax.

He reminds clients that politicians “have talking points. Once they’re elected, let’s wait and see before we make an immediate or emotional reaction.”

Updated: 3-10-2023

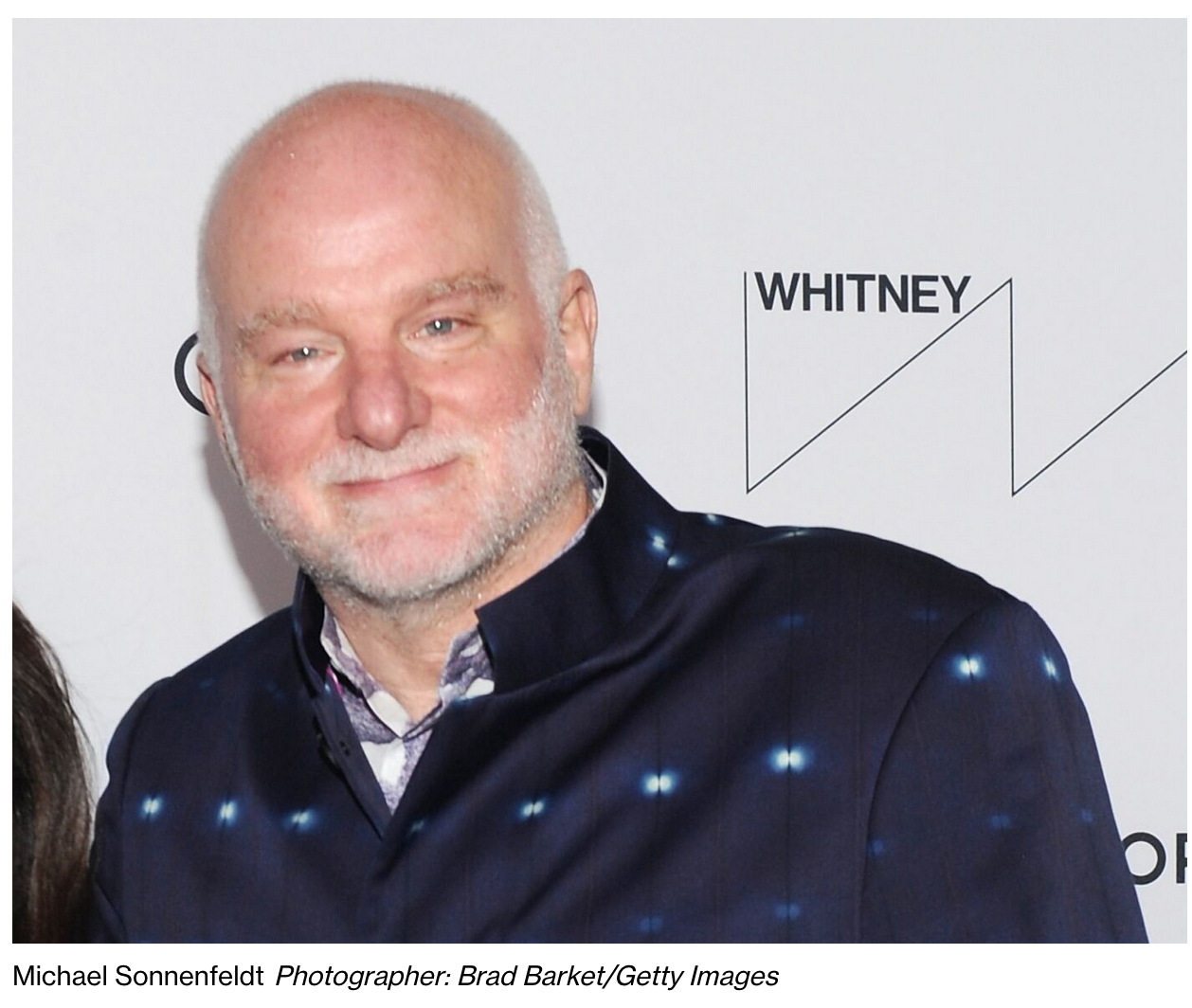

Ultra-Rich Investors Want Second Passports

Wealthy members in the elite network Tiger 21 are nervous about political instability, but they’re still putting money into riskier assets.

Wealthy investors are nervous.

So nervous that they’re lining up second passports, but not so nervous that they’re straying from tried-and-true investments like private equity.

That’s according to Michael Sonnenfeldt, the founder and chairman of Tiger 21, a worldwide network of more than 1,200 high-net-worth investors with assets totaling more than $135 billion.

“It’s totally perplexing,” Sonnenfeldt said in an interview with Bloomberg News, referring to the mixed messages currently being sent by Tiger 21’s members.

Here’s what he thinks is going on in their minds and portfolios. The excerpts have been edited for length and clarity.

Q. What is the general attitude toward risk among members today?

A. The mood is that we have more mixed signals than we’ve ever had to process before, maybe with the exception of the great financial crisis, when things moved so quickly it took your breath away.

Things are moving more slowly but they are more confusing than ever because we don’t know how to weigh where Ukraine is going. What comes up most in discussions is to what extent the outcome in Ukraine emboldens China to invade Taiwan, the center of microprocessor manufacturing.

This notion of the fragility of democracy has a lot of people wondering about how fragile the structures of society are that we take for granted.

People are comfortable with their individual business choices, but see this kind of landscape effect of being at war for the first time since World War II in Europe, and with China doing what it’s doing, and Iran and Israel, and it feels like a lot of macroeconomic uncertainty.

One interesting trend is that the interest in second-country passports has got to be at an all-time high. There are countries around the world, like New Zealand and Portugal, some Caribbean islands, with programs where you can apply for citizenship and get a passport.

The instability in the US is kind of like what’s happening in Israel with the right-wing government — a lot of Israelis are making sure they have second passports.

It creates an optionality that more people are concerned about, with the 2024 election coming up, than maybe ever before in history. But many of these countries are now closing the loopholes.

Q. How does that square with cash allocations being lower than normal?

A. In a million years I wouldn’t have predicted that cash would go down at this time when, as of 2022’s fourth quarter, more than half of members thought we were headed into a recession. Cash has been the steadiest allocation for 15 years — literally like tied to a rock at 12%. So being at 10% is significant.

I think in the past year members have found some compelling private equity investments and been willing to borrow from their cash account for a while.

Q. Many members made their money in private equity and real estate — is that where the bulk of assets remain?

A. Members have about 80% in public equity, private equity and real estate, the highest in 15 years or more. Private equity just topped 31% in member portfolios — an all-time high. Fifteen years ago, PE was 10%. As far as we can tell, the biggest growth within that allocation is venture capital.

Since our members made most of their wealth in PE and real estate, it’s no surprise that when they’re preserving wealth they fall back on what they have expertise in.

As things are getting more confusing, members rely more on the things they know best, which are basic business investments.

Long-term, solid businesses and real estate have come through for them year in, year out, decade in, decade out, and members have this abiding faith in the meat-and-potatoes of business. That’s where they get the most comfort and security.

Personally, in my own investment company, we were recently looking at where to put some money that had been distributed from another investment. Typically, we’d want to deploy it quickly, but for the first time in 20 years we said, let’s put it in Treasury bills for six months.

You can earn 4.5% on six-month Treasuries, so that’s become a viable cash management tool — as it had been for generations, just not in the past 15 years.

Q. What allocation do members have in public markets?

A. It’s down from 28% or 29% a year ago to 23% to 24%, mostly because of the drop in value, not because people liquidated. Members are split between whether they think the public market will go up or down in 2023.

Historically, portfolios had a lot of Berkshire Hathaway and Apple and high-tech companies, but the allocation is shifting more toward indexes and ETFs.

Members are a little concerned about tech but are long-term believers, so probably have a weighting in tech ETFs or some direct investments in tech companies.

Q. How do members view cryptocurrency?

A. Bitcoin and crypto are in the 1% to 3% range in portfolios. For members who believe they have a fundamental and clear understanding of crypto, and like it for those reasons, they’re in it for the long-term and saw the past year as a buying opportunity. Even if they didn’t double down, they didn’t liquidate.

Updated: 8-26-2023

IRS To Use of Artificial Intelligence To Detect Tax Evasion And Identify Emerging Compliance Threats

Funding from the Inflation Reduction Act is allowing the IRS to make a significant investment in its technological and human resources—an opportunity that’s been largely absent for more than a decade.

The latest initiative builds on years of efforts to improve tax administration benefiting every American.

The IRS is now focusing on getting “high-income earners, partnerships, large corporations and promoters abusing the nation’s tax laws” to comply with the law using improved technology and artificial intelligence to detect tax evasion, identify emerging compliance threats, and improve case selection tools.

Advanced data and analytic strategies have enhanced capabilities to identify areas of noncompliance in ways that weren’t remotely possible just a few years ago.

The IRS has access to decades of important data that, coupled with improved funding and emerging technologies, should allow it to more efficiently and effectively build audit workplans as well as identify noncompliant taxpayers and anomalies in filed returns.

Enhanced AI will be effective in helping to determine returns that should be examined as well as returns that shouldn’t be subjected to examination, lessening the burden on compliant taxpayers.

Historic Initiatives

A compliance focus on wealthy taxpayers isn’t new. In the late 1990s, the IRS focused heavily on wealthy individual and corporate taxpayers engaged in various “listed transactions” designed to artificially reduce certain tax responsibilities.

At the same time, the agency pursued one of the largest criminal tax investigations in history, solely focused on whether certain tax professional enablers assisted various wealthy taxpayers in evading their tax responsibilities.

The IRS’s enforcement radar has long focused on: potentially abusive transactions, including offshore noncompliance, high-wealth and high-income non-filers, cryptocurrency transactions, certain tax shelters such as syndicated conservation easements and micro-captive insurance shelters, certain monetized installment agreements, certain Maltese individual retirement arrangements, and certain split-dollar loan arrangements, as well as certain grantor retained annuity trusts.

For most of a decade, the IRS’s global high wealth program has focused on wealthy, potentially noncompliant taxpayers, often using personnel from other parts of the agency to assist on a complex examination.

The Office of Fraud Enforcement, Office of Promoter Investigations, Whistleblower Office, the Joint Strategic Emerging Issues Team, and the Advanced Collaboration Data Center pursue noncompliant high-wealth and high-income taxpayers and corporations.

For the past few years, a special compliance initiative, Revenue Officer Compliance Sweep, has also focused on wealthy non-filers and others. These efforts target activities that are more likely to be engaged in by wealthy taxpayers.

In 2020, the IRS created the enterprise digitalization office to improve business processes and modernizing systems. The staff of “Team Digi” are customer-centered thinkers who focus on desired outcomes instead of prescriptive approaches, and quickly identify combinations of business process and technology that will best improve IRS operations.

Team Digi, composed of some of the most creative people in government, has operated similarly to a highly motivated private sector tech company, improving both internal and external operations.

While facing long-term, consequential resource challenges, the agency routinely was tasked with new, significant responsibilities. Resource constraints often prevented investments in new technologies, leaving the agency to maintain current systems or to build them internally.

Without significant, annual investments in technology, the cost to just maintain existing systems could soon exceed several billion dollars a year.

New Resources

Investing in new technologies using the new funding from Congress will radically improve every facet of operations—internal, external, both service and compliance efforts—allowing the IRS to become a “best in class” agency.

Private sector technology is also more available to the IRS. The private sector has relentlessly pursued new technologies to streamline and accelerate important processes, increase efficiency, leverage important human resources, reduce errors, and improve data quality.

To move forward quickly, private sector firms are acquiring technology from others rather than relying on homegrown technology and in-house teams.

The IRS has also used Inflation Reduction Act funding to expand efforts to recruit and retain experienced, sophisticated, and specialized, technical personnel who can conduct meaningful examinations of complex returns, including those from multinationals and multi-tiered partnerships.

But the number of recent accounting graduates has been steadily declining, and many other tax practitioners are deciding to leave the profession.

It won’t be easy for the IRS to recruit and onboard new staff, although this is a great opportunity for mid-career financial people to gain invaluable professional experience and to serve our country.

Congress should require whatever oversight it desires for IRS operations but should respect the critical need for funding to rebuild the agency and avoid opportunities to reduce existing funding.

The IRS interacts with more Americans than any other public or private institution and reports annual gross revenue of approximately 95% of the country’s entire gross revenue. Congress should help in earning trust and respect for the IRS, rather than targeting it for political gain.

Most recent IRS commissioners have pushed Congress to provide “timely, consistent, flexible, multi-year funding” that would enable the IRS to enhance taxpayer services, compliance, and modernization efforts.

The IRS must be able to provide meaningful services of a type and quality every American deserves. Timely, meaningful guidance should be readily available in whatever form (and language) the taxpayer desires.

For many years, important IRS operational decisions have too often been resource driven, but no more. The IRS is best suited to provide the services Americans deserve and equitably enforce the tax laws to support compliant taxpayers when it receives the resources it needs to do so.

Updated: 2-1-2024

Why People Renounce Their U.S. Citizenship

Rise of Nomadic Lifestyles

The lifestyle of global nomads, characterized by constant travel and residence in diverse countries, presents a unique set of challenges and opportunities. Though the nomadic lifestyle existed prior to COVID-19, the pandemic brought about greater awareness and adoption to the lifestyle.

A nomadic lifestyle poses some practical challenges, particularly in the context of citizenship. Some countries require citizens to maintain a permanent residence or fulfill specific residency obligations.

For global nomads, renouncing citizenship may become a practical solution to navigate the complexities associated with constant travel.

According to MBO Partners, the population of digital nomads in the U.S. rose dramatically from 2019 to 2020, increasing nearly 50%!

Other sources cite there was nearly 17 million digital nomads in the United States alone during the pandemic. Though these statistics do not indicate those leaving the U.S. for this type of lifestyle, it does support the notion that nomadic lifestyle adoption has been on the rise and could perpetuate U.S. citizenship renouncement.

The current tax laws—and the reporting, filing and tax obligations that accompany them—have made many Americans choose to renounce their citizenship, not just because of the money, but because they find the tax compliance and disclosure laws inconvenient, onerous, and even unfair.

One other side effect of FATCA—and the requirement for foreign financial institutions to report information to the U.S. regarding U.S. citizens’ accounts—is that many foreign banks don’t want to deal with American clients at all.

As a result, many U.S. citizens have been turned away by financial institutions abroad, a frustrating problem if you live overseas and want to pay your bills.

In somber language, Section 349(a)(5) of the Immigration and Nationality Act details a U.S. citizen’s right to renounce his or her citizenship by voluntarily “making a formal renunciation of nationality before a diplomatic or consular officer of the United States in a foreign state, in such form as may be prescribed by the Secretary of State,” and by signing an oath of renunciation.1

U.S. Congress. “Public Law 414-June 27, 1952; Immigration and Nationality Act,” Page 268.

The government maintains a federal register of individuals who have renounced their citizenship. In the report issued in July 2023 as well as October 2023, the list of names spanned 12 pages.23 However, the report published in January 2024 showed a spike in individuals leaving with the report now spanning 17 pages.4 Why would someone renounce their U.S. citizenship?

Key Takeaways:

Giving up U.S. citizenship means giving up all benefits, such as voting rights, government protection should you need help while abroad, and citizenship for children born outside the United States.

Renunciation is a lengthy process that involves extensive paperwork, interviews, and fees; it is also a process that is typically permanent—you can’t change your mind and regain your citizenship.

Some Americans have renounced their citizenship because of new laws that require taxpayers to report foreign-held assets to the IRS, and to pay “double” taxes, both in the U.S. and abroad.

Other people have renounced their citizenship for personal or political reasons, such as opposing a war that the country is engaged in or objecting to a political party or elected official.

Under U.S. law, citizenship can be terminated for reasons such as becoming a citizen of a different country, fighting in a war for a different country against the U.S., or attempting to overthrow the U.S. government.

The Process And The Impact Of Expatriation

Abandoning citizenship has serious consequences: You give up the benefits granted to U.S. citizens, including the right to vote in U.S. elections, government protection, and assistance while traveling overseas, citizenship for children born abroad, access to federal jobs, and unrestricted travel into and out of the country.

What’s more, renunciation is not as easy as throwing out your passport. It’s a lengthy legal process that involves paperwork, interviews, and money.

Because of the increase in the number of U.S. citizens seeking renunciation, the U.S. Department of State raised the fee for renunciation from $450 to $2,350, around five times more than the average cost in other high-income countries like the United Kingdom.

In addition, some high-income citizens may owe a type of capital gains tax called an “exit tax” (officially called an expatriation tax).

It’s important to recognize that in nearly all cases, a renunciation is an irrevocable act, meaning you won’t be able to change your mind and regain U.S. citizenship. Despite these (and other) consequences, more and more people are choosing to renounce their U.S. citizenship.

Here’s Why:

To offset the decline in people renouncing their citizenship, the U.S. government boosted the fee from $450 to $2,350, making it more than 20 times the average cost of other wealthy nations. This information is up to date as of the Fall of 2023.

Why So Many Renunciations?

While the reasons for abandoning citizenship vary from one person to the next, the recent spike in numbers is largely due to newer tax laws, including the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) of 2010.

According to the IRS, FATCA is “an important development in U.S. efforts to combat tax evasion by U.S. persons holding accounts and other financial assets offshore.” FATCA focuses on reporting by:

* U.S. Taxpayers About Their Foreign Financial Accounts And Offshore Assets

* Foreign Financial Institutions Regarding Financial Accounts Held By U.S. Taxpayers

* Foreign Entities In Which U.S. Taxpayers Hold A Substantial Ownership Interest

Under FATCA, certain U.S. taxpayers with financial assets outside the U.S. that total more than the reporting threshold must report their assets to the IRS, using Form 8938, Statement of Specified Foreign Financial Assets (the threshold varies based on your filing status and whether you live in the U.S. or abroad).

The IRS warns there are “serious penalties for not reporting these financial assets.” It should be noted the FATCA requirements are in addition to Form 114, Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts (FBAR), the long-standing requirement for reporting foreign financial accounts. The penalties for failing to comply are significant, and, in some cases, involve criminal liability.10

In addition to financial reporting requirements is the issue of double taxation. Unlike most countries, the U.S. has citizen-based taxation, meaning citizens are taxed regardless of where in the world they live and where they earned their income.

While foreign tax credits can reduce the tax burden, they do not eliminate all double taxes, particularly for higher-income earners, who end up filing and paying taxes both in the U.S. and abroad.

The Federal Register reports are slightly delayed in timing. For example, the report released on Jan. 29, 2024, contained the names of renounced individuals who lost citizenship for the period ending Sept. 30, 2023.

Dual Citizenship

Dual citizenship can also be a path that leads to one citizenship being renounced. One primary challenge is the potential conflict of laws and loyalties.

Holding citizenship in two different countries may subject individuals to conflicting legal obligations. This could arise due to military service obligations, taxes, or legal policies.

Another critical consideration in the administrative angle. Managing multiple passports, dealing with tax implications in different jurisdictions, and navigating bureaucratic complexities can cause folks to renounce one of their citizenships.

Keep in mind that in 2023, the United States welcomed 878,500 new citizens; though it’s not directly known how many currently possess dual citizenship, each of these people could have retained citizenship in their home country only to later renounce of the two.

Other Reasons for Renunciation

Historically, Americans have occasionally renounced their citizenship for other reasons. For example, opposition to U.S. policy during the Vietnam War. Certain acts can also cause an individual to lose U.S. citizenship without formally renouncing it.

Under the Internal Revenue Code and/or the Immigration and Nationality Act (found in Title 8 of the United States Code), citizenship can be terminated (and therefore relinquished, not renounced) for several reasons, including:

* Applying For And Becoming A Naturalized Citizen Of Another Country (With Exception Of Dual Nationality)

* Making An Oath Of Allegiance To Another Country