My Idea Of How To Finance The Management Of Wildfires

A California Start-up Wants To Fight Fire With An Impact Bond

A Californian start-up wants to save millions of acres of forest from fires by partnering with the US Forest Service and local businesses on an innovative social impact bond. Around 82 million acres of forest currently need restoration work, but the Forest Service only has enough funds to work on some five million acres annually. One of the few instances where a bond of this type has been initiated by a start-up, it would bring in public and private money for restoration. My Idea Of How To Finance The Management Of Wildfires

Results & Impact:

Blue Forest Conservation has secured about $1m in funding from the Rockefeller Foundation, and a trial is scheduled for later this year, which could cover anywhere 4-10000 acres

Key Parties:

Blue Forest Conservation, the US Forest Service, local water and electric companies

How:

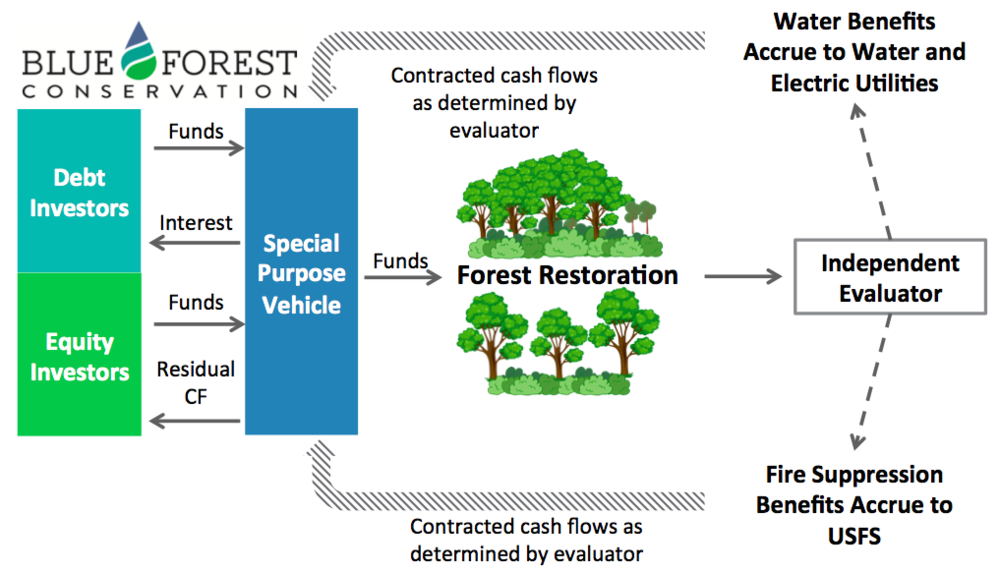

Under the Blue Forest proposal, private investors would provide money for forest restoration work. If the work is successful, the Forest Service and local utilities who stand to gain from better forest and water management would pay the investors a return. In this way, the project would channel private investment to government agencies. One way for investors to see how work is progressing is by looking at vegetation metrics from satellite data

Where:

Tahoe National Forest, California

Target Group:

Entrepreneurs, city dwellers

Cost & Value:

Around $1 million in funding has been achieved

Stage:

Planning

Hurdles:

One current hurdle is that all the partners -public sector agencies and utilities companies – have different understandings of conservation work. One of Blue Forest Conservation’s tasks is to recommend standardisation so all the partners are on the same page

Replication:

Social impact bonds – also known as “pay for success” bonds – have exploded in popularity since they were invented in the UK in 2010. This project is believed to be the first for forest fires, and the first pitched to the public sector by a start-up

The Story:

A San Francisco start-up is pitching government agencies a social impact bond to fight some of the worst forest fires in Californian history. The founders of a new San Francisco firm called Blue Forest Conservation want to help the state by channelling private investment to government agencies via the sale of so-called forest-resilience bonds.

Blue Forest Conservation’s scheme would be one of few instances where such bonds are initiated by a start-up rather than the public sector, and the money would be used to pay teams to cut small trees and clear plants. Investors would earn market rate returns through long-term cost-sharing contracts with partners such as the US Forest Service and water and electric companies, all of whom benefit from better forest management.

Over the last few years, the Forest Service has had to spend more time fighting fires than preventing them. Firefighting now counts for more than half of the Forest Service’s budget and around 82 million acres of forest currently require restoration to prevent fires. Due to a lack of funds, the Forest Service managed to work on only 4.6 million acres in 2014.

Several agencies that depend on the health of the forests stand to benefit. The Forest Service, water suppliers and power utilities could all contribute to paying for the bonds. Major water users such as breweries and bottling plants could also participate. In addition to reducing the risk of fires, the scheme is intended to allow more rainwater and groundwater to flow downstream to reservoirs, businesses and local homes.

Under the proposal, private investors would make funds available for restoration work. If that work is successful, the Forest Service and the local businesses who stand to benefit would agree to pay those investors a return. In this way, a large amount of private funding would be unlocked with only a comparatively small outlay over several years from the public sector.

Blue Forest has yet to sign a deal with the Forest Service, but has secured around $1m in funding from the Rockefeller Foundation. Its founders also aim to start small by raising just a few million dollars for their first bond, which will go towards conserving a small area in Tahoe National Forest.

“We are scoping out a number of areas where we could increase collaboration,” said Nick Wobbrock, co-founder and partner of Blue Forest Conservation. “We are looking at other projects which have already been through the permitting phase and the community collaboration phase. One thing for us to think about is that we don’t want investor money dictating where the projects take place.”

Mike Illenberg, a spokesman for the Forest Service’s parent agency, the US Department of Agriculture said partnering with outside groups is an “essential mechanism” for restoring forests.

Investment in areas of sustainability is a growing trend in public-private partnerships. From less than $1 trillion in 1995, there are now around $8 trillion investments in the US which are locked to environmental, social or corporate governance objectives, according to the Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment. As an industry, sustainable investing has seen 33% growth in the US since 2014.

Deep in the Stanislaus National Forest, an hour’s drive from the foothill town of Sonora, two forests stand side by side.

One is open and airy, with light that streams through gaps between vast sugar and ponderosa pines down to an almost bare forest floor. The other is so dense with brush and smaller trees that little sun peeks through, even at noon on a clear day.

Standing between them during a visit two months ago was a group of would-be financiers — an investment analyst, an engineer and a bond trader — who see potential profit in that stark contrast.

In the coming year, they hope to sell investors on a new type of bond that, instead of financing a corporate acquisition or a pool of mortgage loans, would address two of the biggest challenges facing California: fire and water.

The founders of fledgling San Francisco firm Blue Forest Conservation want to use the proceeds of what they call a forest-resilience bond to pay crews to cut down small trees, clear out shrubs and burn off ground cover in overgrown forests.

That thinning work would reduce the risk of destructive forest fires by removing extra fuel, and theoretically allow more water to flow downstream to reservoirs, hydroelectric dams, farms and faucets, instead of being soaked up by plant life.

That would benefit the U.S. Forest Service, public water agencies, private power utilities and possibly other entities that rely on a healthy forest ecosystem — stakeholders that need to be persuaded to pay back those bonds, with interest, for the whole scheme to get off the ground.

“There are all these entities that benefit from the work, but there’s not really any money to pay for it,” said former investment analyst Leigh Madeira, one of Blue Forest’s founders. “If you can bring all those parties together and repay investors over time, you have a financial instrument.”

The Forest Service, which owns vast tracts of forest land in Western states, pays for thinning or restoration work, but lately has had to spend more on fighting fires than preventing them, a trend made worse by a drought that has killed millions of trees. Last year, firefighting accounted for more than half its budget, up from 16% in 1995.

The Forest Service estimated it did restoration work on 4.6 million acres of land in 2014 — but still has a backlog of as much as 82 million acres.

For Blue Forest’s founders, a September visit to the Stanislaus National Forest was a chance to see up close the difference between a thinned forest and an overgrown one. Crews in 2012 thinned out a section of the forest near the town of Pinecrest but didn’t touch an area along a dry creek bed.

“It’s unbelievable,” Madeira said. “In some forests, there are between four and 10 times as many trees as there used to be. Until you see it, it’s hard to picture.”

Which is why, when pitching potential investors, Madeira begins her presentation with a photo of a forest taken in the 1890s — when small fires were allowed to naturally burn off brush — and the same, much denser forest in 1993 after decades of fire suppression.

The images, she said, help audiences get past a common question: Why does a company focused on conservation want to cut down trees?

“People are unaware that we have so many trees and that that’s a problem,” she said.

What Blue Forest’s founders envision is the latest variety of a relatively new class of investments dubbed social-impact bonds, which channel private capital into programs aimed at addressing social problems.

When those programs meet their goals, governments pay investors back. But when programs fall short, investors lose their money. That’s why they are also called pay-for-success bonds.

The first program funded by a social-impact bond — one aimed at reducing recidivism at a British prison — kicked off in 2010. The first domestic project, another recidivism program, was launched in New York in 2012.

Last year, California’s first social-impact bond program, aimed at reducing homelessness, launched in Santa Clara County. Blue Forest’s effort is among several new ones in the state under development.

Madeira, along with cofounders Zach Knight, Nick Wobbrock and Chad Reed, met while finishing their MBA degrees at UC Berkeley last year. They developed their forest bond for a sustainable-investment competition sponsored by Morgan Stanley and Northwestern University’s business school.

They won and were invited to speak at last year’s Milken Institute Global Conference in Beverly Hills. There, they drew the attention of an investment officer of the California State Teachers’ Retirement System, a massive pension fund with hundreds of billions of dollars to invest. Though he made no promises, he said their idea was interesting.

“That’s when we realized we were on to something,” Madeira said.

Though state and local governments, as well as major philanthropic foundations, have been keen on the idea of social-impact bonds, the financing mechanism has its detractors.

One persistent argument is that they give private investors a chance to profit from what the government should be doing already. Jon Pratt, a bond skeptic and executive director of the Minnesota Council of Nonprofits, said the programs have only become popular because governments are chronically underfunded and there’s little will to raise taxes.

“Much of government has lost public confidence, and so this feels like a solution,” Pratt said. “It can feel like we’re going to get better results, and it’s going to create new money to do this work, which kind of sounds too good to be true.”

He likened these new financing mechanisms to user fees, lottery proceeds and other alternative sources of funds that governments have turned to. They might help in the short term, but ultimately they create a mindset that makes it more difficult for governments to raise needed revenue, he said.

But Wobbrock argues that the forest-resilience bond actually broadens the revenue sources for forest thinning, and that even if the Forest Service had the money to pay all on its own, it shouldn’t.

“A host of utilities — some of which are investor-owned — would benefit financially, but they didn’t pay anything for that work,” Wobbrock said.

It’s also simply not realistic for the Forest Service to work through its backlog alone, he said. With thinning costs of about $1,000 per acre, the work runs into the tens of billions of dollars, many times the agency’s 2015 budget of $5.5 billion.

Though Blue Forest aims to start small, raising perhaps just a few million dollars for its first bond, the firm ultimately hopes to raise much more by tapping into a growing amount of capital earmarked for investments that promise more than a financial return.

Social-impact investing, which advances a social good or at least avoids promoting social or environmental ills, is drawing more and more money.

There are now about $8 trillion in U.S. investments guided by environmental, social or corporate governance criteria, up from less than $1 trillion in 1995, according to a report this year by US SIF, an advocacy group for sustainable investing.

Richard Jones, a wealth manager at Merrill Lynch in Los Angeles, said some of his clients have even started asking about social-impact bonds.

For now, though, he is advising clients to think about social-impact bonds as more akin to a donation — as “philanthropy with the possibility of a return” — and less like a true investment.

“This whole area is still so new,” he said. “If you want something that will maximize your financial return, that’s a different story. We’re not going to recommend social-impact bonds for that purpose.”

That’s why J.B. Pritzker, a billionaire Chicago investor and philanthropist, said he has backed social-impact bonds in his hometown and in Utah through his family foundation. He hopes those bonds end up providing a good return, but also sees them as a tool to refine later bonds that will be more attractive to investors.

One question in particular has dogged some early social-impact bond programs: how to measure whether they are successful. Traditional bonds measure success in dollars and cents, but the math behind behind this new class of bonds is often fuzzier.

In 2013, Pritzker and an impact-investing arm of Wall Street investment bank Goldman Sachs backed a bond that paid for a preschool program in Utah that targeted students believed to be at risk of needing special education. If the program kept students out of the pricey programs, much of the savings would be paid back to investors.

But last year, after the state made its first payment to investors, the program was criticized by experts who said it overestimated the number of students likely to need special education in the first place.

Pritzker said that’s the kind of problem that’s bound to arise from any novel financing mechanism. He noted that another social-impact bond he backed, one that will pay for a preschool program in Chicago, uses a more complicated and rigorous metric to figure out savings.

“Until you do something and make a mistake or two, you don’t really know what’s going to work,” he said.

That’s the same approach taken by the Rockefeller Foundation, a proponent of social-impact bonds that has backed Blue Forest with about $1 million in grant funding.

Saadia Madsbjerg, a managing director at the New York foundation, said the goal is for Blue Forest to develop a bond attractive to any investor.

“We want to develop it into a viable investment product that stands on its own,” she said. “We want investors to invest just based on the pure financial merits.”

Adam Connaker, an associate at the foundation, said Blue Forest could have a shot at meeting that goal because its bonds will be structured to guarantee some repayment even if the program doesn’t meet all its objectives.

The start-up’s founders hope to persuade the Forest Service and utilities to pay a fixed amount of money every year, probably for a decade, for each acre that’s thinned. That not only would reduce the risk of costly fires, but it would have ancillary benefits for utilities. Burned slopes are more prone to erosion, resulting in dirt and silt running into reservoirs, which lowers storage capacity and raises water-treatment costs.

The utilities would only make additional payments if they are convinced the thinned forests send more water into their reservoirs than they otherwise would expect given that year’s rainfall.

Major water users such as breweries and bottling companies might be willing to pay for water benefits, too, said Todd Gartner of environmental research nonprofit World Resources Institute, which is helping develop the bond.

“These companies are often the biggest water user in a watershed,” Gartner said. “They recognize this as a legitimate strategy to help them with physical risk to their water supply.”

Still, like other social-impact bonds, Blue Forest’s has a metrics problem. It will have to come up with ways of measuring how much, if any, extra water their program produces — and get utilities and others to agree on its methods.

The idea that forest thinning can produce more downstream water is not radical, as several studies over the last few years have suggested that’s the case. But it’s never been proved on a large scale and there’s no hard data to pinpoint the potential benefit.

“The question is, how much?” said Roger Bales, a UC Merced professor who studies mountain hydrology. “We’re trying to provide accurate estimates to that question. And we’re trying to write predictions that are accurate enough for investors to see there’s a benefit.”

It’s a complex problem. No watershed, no mountain, no single hillside in the Sierra Nevada range is exactly like another, and all sorts of factors — including elevation, slope, soil thickness and underlying rock features — can affect how much water flows downstream.

One possibility is to use satellite imagery documenting forests before and after thinning. That information would be combined with models developed by Bales and UC Merced research Philip Saksa, Blue Forest advisors who have data from weather sensors throughout the Sierra. The idea is to come up with a rough estimate of how much less water is being absorbed by the forest, and how much more is heading downstream.

Blue Forest has met with hydrologists at Pacific Gas & Electric, but has yet to persuade the utility to commit to the project. Utility spokeswoman Lynsey Paulo said PG&E is interested but needs to know more about the water benefits and other details.

A bigger issue is that the Forest Service has yet to commit to participating. “The Forest Service is sort of the elephant in the room,” Knight said.

Mike Illenberg, a spokesman for the Forest Service’s parent agency, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, said partnering with outside groups is an “essential mechanism” for restoring forests, but did not address Blue Forest’s plans.

And even if the Forest Service signs on and clear metrics can be agreed upon, Blue Forest will have to convince the other entities that the forest-thinning work will save them enough money or provide enough extra water to be worth backing the bond offering.

“If we spend $5 million to avoid a $2-million potential cost, that doesn’t sound like good business to me,” said Richard Sykes, an official with the East Bay Municipal Utility District water agency, which has spoken with Blue Forest.

He likened Blue Forest’s bond proposal to a shopping mall — one that needs a few big, anchor tenants to support many smaller ones.

“They need to have the Forest Service. They’re the biggest beneficiary,” he said. “You’ve got to have a Macy’s in there. We’re the taqueria.”

Facing Deadlier Fires, California Tries Something New: More Logging

Environmentalists and the timber industry, after long butting heads, increasingly agree that cutting trees to thin forests is vital to reducing fire danger.

Obscured amid the chaos of California’s latest wildfire outbreak is a striking sign of change that may help curtail future devastating infernos. After decades of butting heads, some environmentalists and logging supporters have largely come to agreement that forests need to be logged to be saved.

The current fires are hitting populated areas along the edges of forests and brush lands, including the 142,000-acre Camp Fire in Northern California’s Butte County. That now ranks as the most deadly and destructive in state history, killing at least 71 people, leaving hundreds missing and destroying more than 9,800 homes. The Camp Fire and the 98,400-acre Woolsey Fire in Southern California were fueled by fierce winds in unusually dry weather, which turned much of the state into a tinderbox.

Another dangerous factor, land-management experts say, is that forests have become overgrown with trees and underbrush due to a mix of human influences, including a past federal policy of putting out fires, rather than letting them burn. Washington has also sharply reduced logging under pressure from environmentalists.

Now, the unlikely coalition is pushing new programs to thin out forests and clear underbrush. In 2017, California joined with the U.S. Forest Service and other groups in creating the Tahoe-Central Sierra Initiative, which aims to thin millions of trees from about 2.4 million acres of forest—believed to be the largest such state-federal project in the country.

The current fires have trained a spotlight on the strategy: Parts of the forest burned in the Camp Fire in and around Paradise, for example, were overgrown with small, young trees, according to a 2017 forest health plan by the Butte County Fire Safe Council, which had planned to thin a thousand acres of land there over the next decade.

“We need to try new things because what we’ve done in the past hasn’t worked,” said David Edelson, Sierra Nevada project director of the Nature Conservancy, a nonprofit that is part of the new thinning partnership.

Says Rich Gordon, president and chief executive officer of the California Forestry Association, an industry group based in Sacramento: “We absolutely have to thin our forests. Through a long period of fire suppression and lack of timber production, we have allowed our forests to become overgrown.”

The Tahoe-Central Sierra initiative’s work to log and carry out prescribed burns on national forests is expected to pick up next year. Early stages of the project had wound down for the season before the current fires.

The chief aim is to better safeguard the more than 12 million acres of forest in the Sierra Nevada mountain range, roughly a third of the state’s total, and the source of nearly two-thirds of the water Californians depend on.

Communities housing nearly a million people would also get better protection, while lessons learned could lead to more aggressive thinning projects in more populated parts of the state, supporters of the initiative say.

“Having the fuel loads in forests and wild lands reduced is definitely helpful in modifying fire behavior, but it needs to occur at a much greater scale than we are currently doing,” said Jim Branham, executive officer of the Sierra Nevada Conservancy, a state agency that helped broker the partnership.

Wildfires in forests with widely spaced trees are more likely to stay on the ground and burn themselves out, while the brush and small trees in more overgrown forests act as a “ladder” to carry fire higher and spread, according to a 2015 forest-health plan devised in part by the state of Washington.

Thinning isn’t seen as a cure-all. More than anything, climate change is making California more fire prone, according to many scientists and state officials. Six of the state’s 10 most destructive fires have taken place since 2015.

“Even if we are successful on that [thinning] front, there will undoubtedly be events that simply overwhelm us,” Mr. Branham said. “It is a scary future.”

Some environmentalists oppose even the small-scale logging of the California project. The group is removing mainly small-diameter trees as opposed to the big ones favored in the past by commercial timber operations on federal land. Tim Hermach, executive director of the Native Forest Council in Eugene, Ore., blames logging for the buildup of flammable brush and younger trees.

“Every time they take a tree out of a forest, they’re making it hotter, drier and more flammable,” Mr. Hermach said.

Others say the state isn’t doing enough to better protect communities themselves from fire, such as by not allowing development in fire-prone areas and requiring prevention measures such as rooftop vents to capture flying embers.

The thinning coalition represents a new front. The Nature Conservancy’s Mr. Edelson used to sue to block logging plans in national forests as an attorney for another green group. Now he said he sees the need for limited logging because of the dramatic rise in wildfires.

That puts him in agreement not only with timber industry officials, but also U.S. Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, who has earned the ire of conservationists including on efforts to reduce the size of national monuments and open more areas to drilling.

On Wednesday, Mr. Zinke said priority needs to be given to reducing the density of overgrown woodlands to reduce more catastrophic blazes. “The bottom line is there’s just too much dead and dying material,” he said after touring the Camp Fire destruction. President Trump, who plans to tour the area Saturday, has blamed mismanagement for the fires.

California Gov. Jerry Brown, while citing climate change and other factors for the current problems, has spoken glowingly of the Tahoe initiative. The governor on Sept. 21 signed bills authorizing a $1 billion, five-year plan to thin forests, including by easing rules on logging. A month earlier, the Trump administration announced a plan to increase the amount of thinning and controlled burns on federal lands. Forestry experts say the number of acres thinned annually needs to be more than quadrupled from the approximate one million that are done now.

Eli Ilano, supervisor for the Tahoe National Forest, said the federal government has wanted to do thinning work in the past, but that the growing cost of fighting wildfires have siphoned off much of the agency’s funds. The Forest Service’s firefighting costs soared to a record $2.4 billion in 2017 from an average of $1.1 billion a year over the prior decade. A measure contained in a spending bill signed by Mr. Trump in March will provide a dedicated fund for thinning and other forest restoration work beginning in 2020.

U.S. wildfires, mostly in the West, have scorched more than 8.5 million acres so far this year as of Friday, and an average of 6.3 million acres during each of the past five years, far above a 10-year average of 3.7 million a year in the 1990s, according to the National Interagency Fire Center.

The threat is considered by many experts to be gravest in California, because it recently went through a five-year drought and has so many people living in wild areas.

One of California’s most serious fire threats is in the national forests that blanket the Sierra Nevada, the location of the state-federal thinning project, where the U.S. Forest Service estimates 129 million trees have died due to drought and bark beetle infestations. The initiative’s project covers seven counties of state, private and federal lands around Lake Tahoe—one of the mountain West’s biggest tourism draws.

On an afternoon in September, before the latest round of fires, the sound of logging equipment pierced the mountain air near the mile-high French Meadows Reservoir as crews cut trees in a forest owned by the American River Conservancy, another environmental group whose work is being coordinated under the partnership. Operator Brian Chamberlain wiped his brow as he took a break from a machine called a “masticator,” which chopped and ground small fir and cypress trees into tiny pieces.

“They work me like a rented mule,” the 58-year-old joked as fellow lumberjacks nearby sawed and cut other larger trees and stacked the trunks in neat piles.

In thinning projects, old, diseased or too small trees are individually marked for removal. Loggers move in—often operating in pairs—with chain saws or heavy machinery to take down the trees, which are then stripped of limbs by another machine and stacked up. Broad stands of dead trees killed by bark beetle are often clear-cut.

The finished logs are then usually hauled by truck to a commercial timber mill or shipped to a biomass plant to be converted into energy, said Mr. Edelson of the Nature Conservancy. Since there is otherwise little profit for cutters, the work usually needs to be subsidized by governments.

The past acrimony over forest management is partly rooted in the timber wars of the late 1980s and 1990s, when emotions ran so high activists chained themselves to logging equipment to protect endangered species including the northern spotted owl. Amid ensuing court battles, the federal government in effect closed much of its western forests to logging.

Overgrown forests have played a role in dangerous fires in recent years, including 2013’s Rim Fire, the largest recorded fire in the Sierra Nevada, which tore through 257,000 acres.

Of particular concern is the growing severity of the infernos, which get so hot they can actually create their own weather systems, causing winds to shift and spread flames in many directions. More than a third of the terrain in some of the recent big fires in the Sierra Nevada has burned so intensely that biologists say the soil may be too damaged to regrow a forest for many years.

That threatens the water supply. After the King Fire blackened nearly 100,000 acres of forest east of Sacramento in 2014, the Placer County Water Agency had to spend $5 million dredging hundreds of thousands of tons of topsoil that washed into its Hell Hole Reservoir as a result, said Marie Davis, a geologist with the agency. “We want a reliable watershed,” Ms. Davis said. “We can’t keep filling it with sediment.”

Lack of available labor and infrastructure are hurdles to expanding the thinning work. Many of the mills in the area have closed due to the slowdown in logging, a manager said. Many of the workers, meanwhile, including Mr. Chamberlain, the masticator operator, were at or near retirement age.

Despite the challenges, proponents of the thinning said all the work was worth it. “We can spend millions cleaning up the forest,” said Autumn Gronborg, supervisor of a crew near French Meadows, “or billions fighting the fires.”

Related Articles:

California’s Largest Utility Pummeled By Wildfire Risks (#GotBitcoin?)

California Utilities Plummet On Wildfire Fears (#GotBitcoin?)

Trump Is Responsible For Deaths In California Wildfires

Poll: The Cause Of California’s Wildfires Is Mainly Due To:

Your questions and comments are greatly appreciated.

Monty H. & Carolyn A.

Go back

This is such an informationrmative story and very clearly written. Every single thought and idea is direct to the point. Perfectly laid out. thank you for taking your time sharing this.

Thanks for the compliments.

We really appreciate the feedback.

Monty