Ultimate Resource For Retirees And Retirement Planning (#GotBitcoin)

We can’t tell the difference between needs and wants and are unable to delay gratification. From the lofty perch of old age, and after a lifetime of thrift, I declare that I am qualified to comment on how not to waste money. Ultimate Resource For Retirees And Retirement Planning (#GotBitcoin)

We’ve all heard the reports: Most Americans live paycheck to paycheck, a large number can’t come up with $400 for an emergency, and there’s no money to save for retirement and other goals.

Related:

Pension Funds And Insurance Firms Alive To Bitcoin Investment Proposal

Public Pensions Miss Fantastic Bitcoin Gains

The Pension Hole for U.S. Cities and States Is the Size of Japan’s Economy

Big Gains Did Little To Boost Corporate Pension Plans

The Long Bull Market Has Failed To Fix Public Pensions

Paying Off Unfunded Pension Liabilities Will Be A Low Priority After COVID-19

World’s Top Pension Fund Books ‘Historic’ $339 Billion Gain

Most of that data comes from surveys where people are, in effect, saying they don’t have enough income. My curmudgeonly reaction: Stores, fitness centers and entertainment venues are packed with shoppers, many of them buying unnecessary goods and services.

If three-quarters of Americans are living paycheck to paycheck, how can they afford to spend like this? It’s a funny thing: I have yet to see Warren or Bill in one of the many local spas.

Most Americans live like no other people on earth. We have more and bigger stuff: Larger houses, bigger vehicles, more shoes. And, in my not so humble opinion, we can’t tell the difference between needs and wants, between necessities and desires—and we sure can’t defer gratification. These 16 Money Wasters

All this leads me to one conclusion: We’re unable to control our spending or manage our money. Here are 16 things that this 75-year-old considers big money wasters:

These 16 Money Wasters:

1. Tattoos. They’re an admitted obsession of mine. What will they look like when you’re my age? From what I’ve heard, a good tattoo artist charges $200 an hour.

2. Vacations. Hey, everyone needs a break. But you don’t need to go into tuition-level debt to have a good time. Your kids will survive if they never visit the Magic Kingdom.

3. College. Picking a college involves many factors. Affordability is one that’s often overlooked. If the cost of the school you choose will land you in debt, you’d better have a plan for paying it off. Don’t mortgage your future, just so you can have a prestigious decal on your car window.

4. Restaurants. Eating out, or buying $4 designer coffee, is expensive and—wait for it—it’s also a luxury. Skip that daily $4 coffee and after 30 years you’ll have more than $121,000, assuming a 0.5% monthly return.

5. Opportunities Lost. We do it every day by failing to grab the employer match on our 401(k) plan, not investing in a tax-free Roth IRA, failing to fund a flexible spending account to pay medical costs with pretax dollars, and withholding too much from our paycheck, so we’re essentially making an interest-free loan to the IRS.

6. Transportation. You don’t “need” an SUV or $40,000-plus pickup truck to get from A to B. My four kids grew up riding in our 1972 Duster. Now they, too, all have trucks or SUVs.

7. Credit Cards. When people say they live paycheck to paycheck, does that include purchases put on credit cards that aren’t paid off that month? In that case, they’re spending more than their paycheck—and what they buy will cost them the purchase price, plus a hefty interest rate.

8. Lottery. The lowest-income groups spend the most on lottery tickets, wasting hundreds of dollars a year—about the same as that $400 emergency fund they don’t have. Not to worry: 60% of millennials think winning the lottery is part of a wise retirement strategy.

9. Clothing. My new condo has two bedrooms and three walk-in closets, two of them larger than the bathroom in my old 1929 house. The average adult spends $161 a month on clothing. We are obsessed with keeping up with the latest fashions and ensuring nobody sees us in the same clothes twice.

10. Shoes. Surveys suggest the average American woman owns more than 25 pairs of shoes, which they admit they don’t need. So why buy so many pairs? It seems shopping and wearing trendy stuff makes us feel good.

11. Tchotchkes And Stuff. Clean out a house after many years—which my wife and I just did—and you often hear the words, “Where did we get that?” Though relatively inexpensive per item, tchotchkes and similar stuff cost money—and it all adds up.

12. Failing To Look Ahead. Henry Ford said, “Thinking is the hardest work there is, which is the probable reason why so few engage in it.” I still marvel that people spend so little time thinking about retirement. After working 30 to 40 years, they reach retirement with no plan and are shocked they can’t live on Social Security alone. Planning for retirement early in your career is essential for financial security—and it isn’t that hard.

13. No Backup Plan. I like to think ahead about “what ifs” and how I’ll deal with them. In my head, I have backups for the backups. I recently took out a large mortgage to buy a condo. Now I’m thinking, “What if I can’t sell the house to cover the mortgage? What if I must do some upgrades to sell the house?” I temporarily stopped reinvesting my tax-free bond interest, so I can build up more cash—just in case.

14. Holidays. Somehow, every December, financial caution goes out the window and we pay for it the following year. But my pet peeve are those inflatable characters on lawns that cost hundreds of dollars. Talk about blowing money.

15. Toys. One study shows that U.S. parents spend $6,500 on toys during a child’s upbringing. The spending is even higher for millennials, who favor “smart” toys—toys that do the thinking for the child. There’s something wrong with this picture. Hey, I’ll challenge anyone to a contest dropping clothespins into a milk bottle.

16. Haircuts. The average haircut reportedly costs $28.30 in a barber shop. Many men pay a lot more. Nowadays, nearly a third prefer a “salon.” I pay $12 at my local barber. But I’m still annoyed: My hair is disappearing, but the price is inching up.

Updated: 8-20-2021

Quirks In A U.S. Treaty With Malta-Based Pensions Turn Into A Tax Play

An offshore tax shelter promises rich Americans they can avoid lots of capital-gains taxes by setting up pension plans in Malta—and maybe some can.

Have you heard of Malta Pension Plans? They’re offshore tax shelters that are hot with some wealthy Americans.

As usual with tax shelters, the promoters promise they’ll slash tax bills by making clever use of legal quirks. That puts them in a somewhat gray area, meaning the tax savings could bring legal risks.

Malta has caught the attention of advisers due to quirks in a 2011 tax treaty between the U.S. and the small, sunny island that sits at a historic crossroads in the Mediterranean Sea.

Advocates say Malta plans can dramatically lower U.S. taxes on the sale of highly appreciated assets like cryptocurrency, stock or real estate. Instead of paying a top federal rate of 23.8% on capital gains—or 43.4% if a Biden administration proposal is enacted—U.S. investors can fund a Malta pension with such assets, sell them, and soon withdraw large chunks of the money tax-free if the saver is age 50 or older.

Predictably, Malta pensions have also caught the eye of the Internal Revenue Service. In July, the agency put them on its “Dirty Dozen” list of tax scams to avoid. However, the IRS said only that it may challenge some Maltese pensions—not that all plans are abusive, or that it will challenge them.

California attorney and Malta-plan advocate Jeffrey Verdon has posted a YouTube video extolling these strategies as a “unique opportunity” for high-income taxpayers. The video says these pensions are like “a supercharged cross-border Roth IRA” that offer high earners benefits they typically can’t get from Roth IRAs under U.S. rules.

Mr. Verdon declined to comment on Malta pensions.

Cross-border specialists concur that the U.S-Malta treaty’s language provides unusual tax benefits. They caution that the Treasury Department may have overlooked them when it negotiated the treaty, and the loopholes may not last.

“Malta exempts pension payments received by its own residents, so the treaty requires the U.S. to exempt certain payments from U.S. tax,” says Jeffrey Rubinger, an international tax lawyer in Miami.

Did U.S. officials mean to allow Americans to set up Maltese pensions mainly to avoid U.S. taxes? “It’s unlikely this outcome was intended,” he says.

Here’s a simplified example of how Malta pensions work under the plain language of the treaty, based on a blog post by Mr. Rubinger.

Say that Jane is a 49-year-old U.S. resident with highly appreciated cryptocurrency holdings and shares of a startup about to go public. These assets have a cost basis—i.e. the starting point for measuring taxable capital gains—of $10 million.

After the IPO, the assets could have a total value of $100 million. Under current law, the top rate on these gains would be 23.8%, or about $21 million.

As part of her retirement planning, Jane contributes these assets to a Maltese pension account, which is allowed to receive large contributions of appreciated assets. (Assets in the plan don’t have to be in Malta; they can be held at a U.S. institution and invested by U.S. managers.) Jane then sells both assets and has $100 million in her pension account.

Under Malta rules, Jane needs enough assets to provide her with a pension payout of “sufficient retirement income,” but meeting that threshold isn’t hard. She’ll owe tax to Uncle Sam at ordinary-income rates on part of this payout. But she doesn’t have to withdraw right away, and the assets can grow tax-free.

‘Does the law really intend to allow people to avoid all these taxes?’

— Scott Diamond, Roxbury Consultants

Now comes the tax magic: Based on the Maltese criteria, Jane has more than enough money saved for her pension, and she can take large withdrawals of excess funds as lump-sum payments once she turns 50—even on assets that had a lot of untaxed appreciation going into the plan.

These payouts are free of both Malta and U.S. tax under the treaty language, say advocates.

The Maltese rules allow the first tax-free lump sum to be about 30% of the assets, or $30 million for Jane. The next tax-free lump sum, about half the remainder, can come out in the fourth year.

If the assets have grown to $85 million by that point, Jane could likely take another tax-free payout of $40 million or more.

As a result, Jane could withdraw $70 million or more, tax free, within five years of setting up her plan—saving her about $17 million of U.S. tax. She can take further tax-free withdrawals annually after that.

This strategy comes with caveats. Richard LeVine, an international tax lawyer with Withers Bergman, says that to be free of U.S. tax, the payouts under the U.S.-Malta treaty must also comply with the treaty’s overall conception of a pension.

“To qualify for the tax-free treatment, a plan has to operate mainly as a pension—or the IRS could argue it’s not one,” he says.

Improper moves could include making large withdrawals too fast, or putting too much of one’s net worth into a plan—judgment calls that depend on a taxpayer’s circumstances.

In addition to an IRS crackdown, the Treasury Department could seek changes to the Malta treaty. Congress could also move to limit benefits, says Mr. LeVine.

Scott Diamond, a Los Angeles-area adviser who heads Roxbury Consultants, has a simpler reason for not allowing clients to have Malta pensions.

“My struggle has been the smell test. Does the law really intend to allow people to avoid all these taxes?” he says.

Still, Malta plans aren’t totally out of bounds. Andrew Mitchel, an international tax lawyer in Centerbrook, Conn., who also hasn’t recommended Malta plans to his clients, says he can understand their appeal.

“Someone who has $200 million in bitcoin or IPO shares may not mind spending $2 million on legal fees to see if they can avoid a lot of taxes,” he says.

Updated: 9-4-2021

Main Street Pensions Take Wall Street Gamble By Investing Borrowed Money

Municipalities have assumed about $10 billion in debt this year to shore up retirement obligations.

Many U.S. towns and cities are years behind on their pension obligations. Now some are effectively planning to borrow money and put it into stocks and other investments in a bid to catch up.

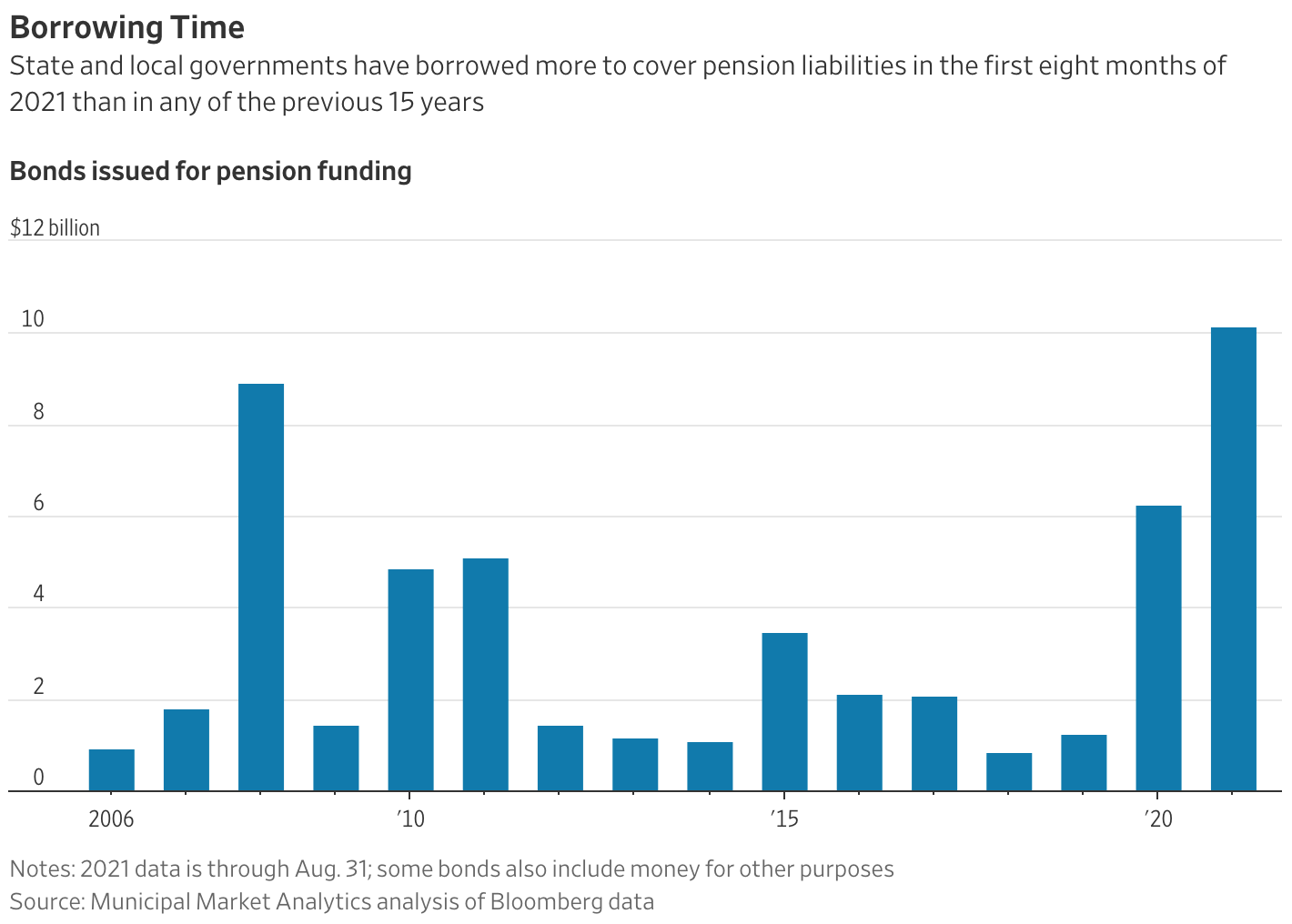

State and local governments have borrowed about $10 billion for pension funding this year through the end of August, more than in any of the previous 15 full calendar years, according to an analysis of Bloomberg data by Municipal Market Analytics.

The number of individual municipalities borrowing for pensions soared to 72 from a 15-year average of 25.

Among those considering what is known as pension obligation borrowing is Norwich, a city in southeastern Connecticut with a population of 40,000.

Its yearly payment toward its old pension debts has climbed to $11 million in 2022—four times the annual retirement contribution for current workers and 8% of the city’s budget.

The city will vote in November on whether to sell $145 million in 25-year bonds to cover the pensions of retired police officers, firefighters, city workers and school employees.

Norwich’s rating from Moody’s Investors Service is in line with the median for U.S. cities, and officials expect to pay about 3% in interest. Norwich’s pension consultant, Milliman, projects investment returns of 6.25%.

Comptroller Josh Pothier said that spread helped him overcome his initial hesitation. “It’s pretty scary; it’s kind of like buying on margin,” he said he thought to himself. “But we’ve had a long run of interest rates being extraordinarily low,” he added.

Milliman forecasts that Norwich would save $43 million in today’s dollars over the next 30 years.

Over the past few decades, state and local governments across the country have fallen hundreds of billions of dollars behind on savings needed to pay public employees’ future promised pension benefits. Officials have been trying to catch up by cutting expenses from annual budgets and making aggressive investment bets.

With big pension payments looming and Covid-19-era federal stimulus pushing municipal borrowing costs to record lows, local officials are taking a gamble: that their retirement plans can earn more in investment income on bond money than they pay in interest.

Here is how a pension obligation bond works: A city or county issues a bond for all or a portion of its missed pension payments and dumps the proceeds into its pension coffers to be invested. If the returns on pension investments are higher than the bond rate, the additional investment income will translate into lower pension contributions for the city or county over time.

(The $10 billion in pension borrowing captured by the Municipal Market Analytics analysis also included some money used directly for pension benefits, rather than being invested, and at least one borrower directed some bond proceeds to other uses.)

Pension obligation bonds can backfire. If investments don’t perform as expected and returns fall below the bond interest rate, the city can end up paying even more than if it hadn’t borrowed.

Norwich is one of many smaller municipalities venturing into pension borrowing. This summer local governments issued 24 pension obligation bonds with an average size of $112 million, according to data from ICE Data Services.

That compares with 11 deals with an average size of $284 million during the same period last year.

The Government Finance Officers Association, a trade group, in February reaffirmed its recommendation against the practice.

“Absolutely nothing has changed,” said Emily Brock, director of the group’s federal liaison center. “It’s still not a good choice.”

In 2009, Boston College’s Center for Retirement Research examined pension obligation bonds issued since 1986 and found that most of the borrowers had lost money because their pension-fund investments returned less than the amount of interest they were paying. A 2014 update found those losses had reversed and returns were exceeding borrowing costs by 1.5 percentage points.

By swapping out their pension liability for bond debt, local pension borrowers give up the budgetary flexibility to skip a retirement payment in an acute crisis.

Pension obligation bonds have contributed to the chapter 9 bankruptcies of Detroit, Stockton, Calif., and San Bernardino, Calif. Chicago three years ago considered, and then scrapped, plans for a big pension borrowing deal.

Other local officials are starting to educate themselves about the deals. More than 200 people attended the webinar “How to Explain Pension Obligation Bonds to Your Governing Board,” hosted by the law firm Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe last month.

For investors, the bonds can be more of a mixed bag. A pension obligation bond approved by Houston voters in 2017 earned praise from analysts because the city paired it with benefit cuts.

Howard Cure, director of municipal bond research at Evercore Wealth Management, said that though he occasionally purchases the securities, the decision to issue them raises red flags. “I have a lot more questions about how an entity is governed if they’re using this tactic,” Mr. Cure said.

Updated: 9-7-2021

Democrats Aim To Push Firms Into Auto-Sign-Up Retirement Plans

House Democrats proposed requiring companies to automatically enroll workers for IRAs or 401(k)-type retirement plans under a provision tucked into draft legislation enacting the bulk of President Joe Biden’s economic plan.

The proposal addresses a problem that has been exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic: Americans haven’t saved enough for retirement. Nearly half of people aged 55 or older have nothing saved for after they stop working, according to a 2019 U.S. Government Accountability Office report.

The draft legislation, unveiled by the House Ways and Means Committee on Tuesday, would direct 6% of each employee’s pay into a retirement savings plan, gradually escalating to 10%, unless they took action to opt out or change their contribution rate.

The idea is a pet cause of House Ways and Means Chairman Richard Neal and his Republican counterpart Kevin Brady, who jointly introduced legislation last year to bolster retirement savings through automatic contributions.

It has also been promoted in research by behavioral economists showing the importance of nudging people toward savings by setting defaults.

The legislation also would allow low-income Americans who don’t make enough to pay taxes to take advantage of the “savers credit,” a tax credit available to low- and middle-income Americans to partially offset retirement contributions. The credit would become refundable under tax law.

Automatic enrollment would cost the U.S. Treasury $22.7 billion over 10 years as more Americans take advantage of tax savings from retirement plans. The entire retirement provision, including the changes to the savers credit, would cost $46.8 billion over the period, according to an estimate by Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation.

Companies that fail to comply with the new rules would face an excise tax of $10 per employee per day.

The retirement proposal was one of a slew of draft measures released by the House Ways and Means Committee Tuesday, part of work under way by panels in both chambers of Congress to assemble legislative text for what’s currently planned as a $3.5 trillion tax-and-spending package.

Americans Say They’re Now Less Likely To Work Far Into Their 60s

Americans say it’s increasingly unlikely that they’ll work deep into their 60s, according to new data from the New York Federal Reserve.

The share of respondents expecting to work past the age of 62 dropped to 50.1% in the New York Fed’s July labor-market survey, from 51.9% a year earlier — the lowest on record in a study that’s been conducted since 2014.

The numbers saying they’re likely to be employed when they’re older than 67 also dropped, to 32.4% from 34.1%.

The data reinforces other research pointing to a wave of early retirements triggered by the pandemic.

More than 1 million older workers have left the labor market since March 2020. Some Americans have been rethinking their priorities after the trauma of Covid-19 — with a bigger nest egg to fall back on, thanks to exuberant financial markets. For others the withdrawal may be involuntary, driven by a lack of employment prospects.

It’s adding up to a dramatic shift in a labor market where job growth has been dominated by older workers over the last two decades.

Job Poachers Beware

As many older Americans eye the exit, they’re also holding tighter to the jobs they have.

The so-called “reservation wage’ — the lowest salary that respondents would be willing to accept to switch to a new job — rose sharply for workers age 45 and over, according to the New York Fed report. It increased by some 11% in the year through July — roughly double the rate of inflation.

Updated: 10-1-2021

Murder Victim’s Son Can Get Money From 401(k) Linked To Killers

The son of a man murdered by a Colombian guerrilla group can obtain money from a 401(k) account connected to the perpetrators, a Massachusetts federal judge ruled, deciding a novel legal question involving federal benefits and anti-terrorism laws.

Fidelity Investments can turn over 401(k) assets to the victim’s son under the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act of 2002 without violating the federal law protecting retirement plan assets from being used for other purposes, Judge Indira Talwani of the U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts held Thursday.

The TRIA begins with a “notwithstanding” opening clause, signaling that it’s intended to override any conflicting federal statutes, including the Employee Retirement Income Security Act, Talwani said.

“Where the clear and broad language of TRIA signals Congress’s intent to override conflicting statutory provisions, the court concludes that ERISA’s anti-alienation provision does not prevent” Antonio Caballero “from executing on the attached assets,” she said.

The lawsuit is an attempt by Caballero to execute a judgment against Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia and Norte de Valle Cartel for the kidnapping, torture, and murder of his father.

He asked Fidelity to turn over about $200,000 that it held in connection with these defendants, and Fidelity sought a court ruling on whether it could turn over money held in a 401(k) account without violating ERISA’s anti-alienation rule.

Talwani ruled that Fidelity could distribute the money to Caballero, but only under the same terms that the owner of the 401(k) account would have been able to access the money.

Doherty Law Offices LLC and Zumpano Patricios represents Caballero. Dechert LLP represents Fidelity.

The case is Caballero v. Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, 2021 BL 373566, D. Mass., No. 1:21-cv-11393, 9/30/21.

Updated: 10-7-2021

Companies Decide the Time Is Right To Offload Pensions To Insurers

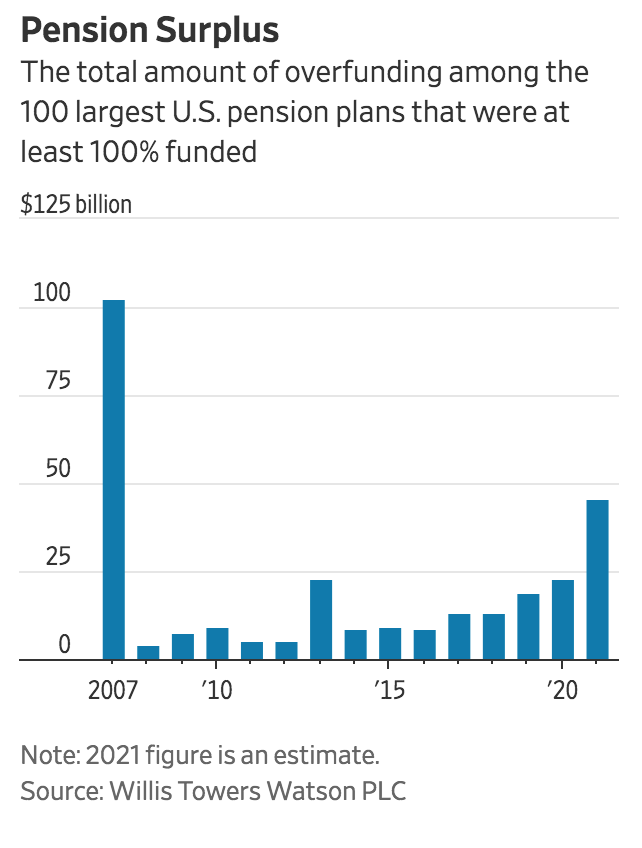

The roaring stock market means plans are fully funded, and by yearend the deals may total $30 billion.

Many Americans who still have a traditional pension—the kind that pays a regular income no matter what the market does—could soon have a different company paying their benefits.

U.S. companies owe current and future retirees and their beneficiaries more than $3 trillion, and many have been trying to exit the retirement business for years. Right now they have a golden opportunity to buy their way out.

It’s called a pension risk transfer, or PRT: By buying a financial product called an annuity, a company can essentially place the assets of a plan and the responsibility for paying for it into the hands of a life insurance company. The insurer makes money if it can earn more from investing the assets than it has to pay out.

(Another risk-transfer option is to offer to pay benefits in a lump sum; in that case, the risk of ensuring the money lasts is taken on by the pensioner rather than another company.) These deals with insurers aren’t new, but record high markets are making them especially attractive to employers.

That’s because investment gains have helped many pensions get close to full funding, meaning they hold enough assets to satisfy their obligations to current and future retirees. If a company transfers a plan that’s not fully funded, it has to pay to cover the shortfall. There’s a very small amount to make up right now.

The 100 largest corporate pensions were funded at 97.1% in August, according to the consultant Milliman Inc., and they could creep as high as 102% by the end of the year under optimistic projections. A year ago, pensions were less than 87% funded.

The window to strike a pension deal could close quickly. If the markets start to fade, an employer would need to pay more to top off its plan before handing it over. Conversely, if a plan’s investments do well enough to surpass 100% funding, the sponsoring company has less incentive to exit as it could face a tax bill.

And it doesn’t benefit from having excess cash sitting idle in the fund. “There’s a bit of an inflection point for sponsors as they reach full funding,” says Matt McDaniel, a pension consultant with Mercer, which advises companies on their benefit plans.

There have already been a handful of jumbo pension deals this year, including a $4.9 billion transaction by Lockheed Martin Corp. and insurer Athene Holding Ltd. and a $5.2 billion accord between Prudential Financial Inc. and HP Inc. By yearend, insurance broker Willis Towers Watson Plc expects more than $30 billion worth of transactions, which could make 2021 the busiest year since 2012.

Companies have been eager to shed the plans for several reasons. The simplest one is risk: A pension is a liability that sits on an employer’s balance sheet for a very long time, and it has to be paid even if business is slow and markets are down.

Most companies now prefer to fund 401(k) plans, which put the burden of managing retirement assets on the employee.

Additionally, low interest rates and bond yields mean that companies could struggle in the future to earn high enough returns to fund their obligations, even as the plans remain costly to maintain.

Providers are required to pay premiums to the federally backed Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp., which insures the trillions of dollars of obligations the plans carry.

Many life insurance companies like pension assets because they can balance the obligations against other products in their portfolios. For example, pension payments are made as long as a participant lives, while a life insurance policy is paid out only upon death. The insurer can hedge the risk of people living longer than expected against that of customers dying too soon.

Insurance companies backed by private equity have also jumped into the business. Apollo Global Management Inc. is the largest shareholder in Athene, which is taking on the Lockheed Martin plan. Athene’s retirement assets have provided Apollo with a big pool of long-term capital it can invest and on which it’s earned lucrative fees. In March, Athene and Apollo announced a plan to merge.

Pension plan participants might wonder how their benefits change after a risk-transfer deal goes through. Most things will seem quite similar: Payments will still arrive monthly and in the same amounts; Prudential Financial says it matches previous payments down to the penny.

The big difference is in how these plans are supervised. Rather than being insured by the PBGC, which pays benefits up to a limit when a plan fails, they’re monitored by the state regulators who oversee insurance companies. Each state also has a guaranty association that can provide some protection if an insurance company collapses.

Joshua Gotbaum, who served as the director of the PBGC during the Obama administration, told a federal panel in 2013 that there was no real difference between a plan backed by the PBGC and one managed by an insurer.

James Szostek, a vice president for the American Council of Life Insurers, says life insurers have “decades of experience managing long-term obligations” as well as being subject to regulatory oversight.

Even so, retiree advocates say the shift can be a source of consternation for pension participants. “The reaction whenever there’s change is concern,” says Norman Stein, a law professor at Drexel University and a senior policy adviser to the Pension Rights Center. In a stroke, people go from relying on the company they worked for over a career to an insurer they may have never given a thought to.

Stein says some of the regulations around PRT transactions and the protections for workers and retirees after a switch can be murky. He says the shift can be particularly worrying in the case of insurers backed by private equity firms, which have a reputation for risk-taking investments.

Sean Brennan, executive vice president of pension risk transfer at Athene, says insurers are a safer bet than many employer-run plans “with a bunch of equity and interest rate risk.”

Since Prudential brokered two giant pension deals nine years ago, life insurers have expanded aggressively. There are now 19 life insurers willing to strike PRT deals, and more are expected to enter the fray, Mercer’s McDaniel says.

“Competition is certainly there,” says Melissa Moore, senior vice president for U.S. pensions at MetLife Inc. That’s helped bring down the main cost of a transfer, which is buying the annuity. “Annuity pricing is currently exceptional, and the annuity market is bustling as a result,” says Steve Keating, managing director at BCG Pension Risk Consultants/BCG Penbridge, which helps employers manage their retirement costs.

A recent study commissioned by MetLife found that 93% of 250 plan sponsors surveyed intend to divest all of their obligations, up from 76% in 2019. Companies can choose to fully divest the plans or reduce the scope of pensions on their balance sheets without removing them entirely.

But plenty of businesses are looking to get out for good, according to Yanela Frias, president of Prudential’s group insurance business. “The reality is that an insurance company is much better positioned to manage this liability than a car manufacturer or a telephone company,” Frias says. “We do this for a living.”

BOTTOM LINE – U.S. employers have been trying for years to get the cost of funding employees’ retirement off their books, and insurance companies are ready to make them a deal.

Updated: 10-10-2021

Here’s How Much Those Lottery Tickets Could Cost You In Retirement

For one lucky lottery player, retirement planning just got a whole lot easier.

Last Monday’s $699.8 million Powerball jackpot—the seventh-biggest in U.S. lottery history, according to Powerball.com—went to a lone winner, who purchased the ticket in California.

Even if the holder takes the $496 million cash prize over the full jackpot amount spread out over 29 years in an annuity, he or she should have ample income for a potentially long retirement.

A chance at that kind of money can be hard to pass up, even if the odds of winning a Powerball jackpot are 1 in 292.2 million. For Mega Millions, another multistate lottery whose jackpots often end up in the hundreds of millions,the odds are even worse at 1 in 302.5 million. Still, as Monday’s drawing proves, someone has to win eventually.

“We actually do have one client who won the lottery, so it does happen,” said Kevin Barlow, managing director at Miracle Mile Advisors. “But in general, the value of the lottery is in dreaming about winning, not in actually having a high likelihood of winning. And unfortunately, it’s often the people who have less money to lose who play the lottery.”

With lottery jackpots climbing higher in recent years, even the most disciplined savers can be tempted to take a shot. What’s more, lottery games are expanding and becoming more expensive to play.

In August, Powerball added a Monday drawing to its weekly schedule of Wednesdays and Saturdays. Mega Millions, which holds drawings Tuesdays and Fridays, might follow suit.

But players should remember that each $2 ticket is almost guaranteed to lose, and over time, they could be building a small fortune by redirecting that money to retirement savings accounts, financial advisors say. Before Monday, Powerball players had gone a record 40 consecutive drawings without a grand-prize winner.

Barlow said the seemingly small expenditures that become part of everyday life, like playing the lottery, smoking cigarettes, or visiting a coffee shop each morning, add up to significant sums over time.

By consistently investing that money in an S&P 500 index fund, for example, savers could enjoy sizable gains over 30 to 40 years, resulting in a higher standard of living in retirement, he said.

A lottery player purchasing one ticket for each of the week’s five major drawings spends $520 a year, or $15,600 over 30 years. If those funds were invested instead, after 30 years, the saver would have about $90,000, based on the S&P 500’s average annualized return of almost 10%.

Similarly, smokers who drop the habit and invest the money can be richly rewarded. The average price of a pack of cigarettes in the U.S. in March was $7.22, according to the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. Smoking one pack a day amounts to about $2,635 a year in average spending, or $79,000 over 30 years. If that money were invested in the S&P 500 instead, it would grow to about $459,000, based on historical returns.

“For people who truly are addicted to things like the lottery or cigarettes, it adds up to a pretty big number over time,” Barlow said. “It’s very hard to visualize how a small amount of spending in your 20s, whether it’s on vices or other goods and experiences, is actually a large amount of money in your 50s and 60s, because compound interest can create a lot of wealth over time.”

Barlow said it’s OK for people to play the lottery “within reason,” buying an occasional ticket when jackpots are high, so long as they’re also addressing their financial priorities, including saving for retirement.

Charles Rotblut, vice president at the American Association of Individual Investors, said the only time it makes mathematical sense to play the lottery is when the Powerball jackpot reaches $490.7 million or the Mega Millions jackpot hits $530.5 million.

At those levels and higher, the expected return per ticket exceeds the $2 cost, according to Rotblut’s calculations, so the “expected value” per ticket justifies a purchase.

“Even if the expected value is positive, what’s really driving that is the massive jackpot,” Rotblut said. “So, even though from an odds basis you’re getting more potential value from this ticket than you’re paying for it, at the end of the day, you’re still facing very extreme odds.”

Despite those long odds, when reached before Monday’s big drawing, Rotblut said he planned to plunk down two bucks in pursuit of the big prize.

“I’ll probably buy a single ticket, and that’s it,” he said.

Updated: 10-12-2021

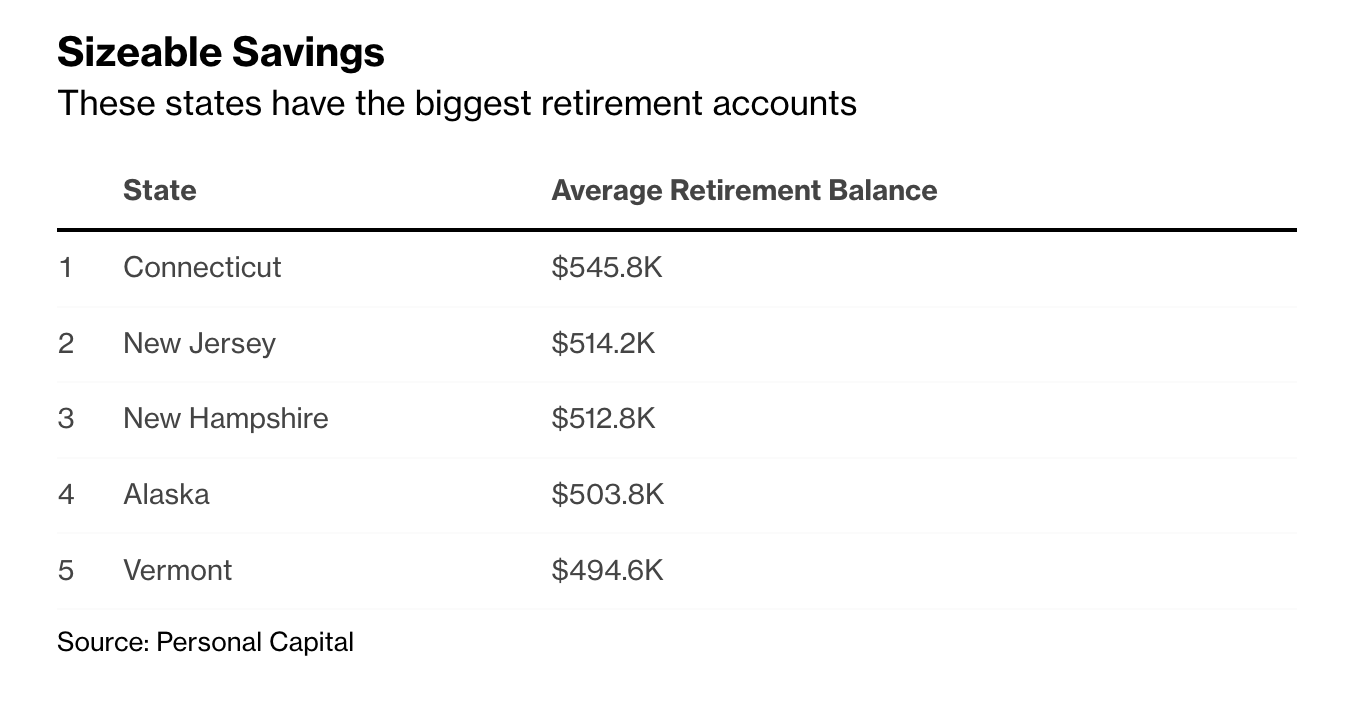

Connecticut Leads U.S. With $545,000 Average Retirement Savings

Hedge fund hub Connecticut is home to the fattest retirement accounts in the U.S.

Residents there have socked away an average of about $545,000 in retirement savings, according to a report from financial advisory Personal Capital. New Jersey came in second at $514,000.

More than 400 private investment funds have offices in Connecticut, including Ray Dalio’s Bridgewater Associates and Steven Cohen’s Point72 Asset Management. And, along with New Jersey, the states are among a handful with the highest ratio of millionaires per capita.

As for New York, it’s near the bottom of the list — ranked 40th with an average balance of $382,000.

The Personal Capital report analyzed 2.8 million user accounts.

Updated: 10-20-2021

An Ohio Pension Manager Risks Running Out of Retirement Money. His Answer: Take More Risks

Farouki Majeed and other retirement-system officials are turning to private equity, private loans and real estate to plug gaps in their ‘leaking bucket’.

The graying of the American worker is a math problem for Farouki Majeed. It is his job to invest his way out.

Mr. Majeed is the investment chief for an $18 billion Ohio school pension that provides retirement benefits to more than 80,000 retired librarians, bus drivers, cafeteria workers and other former employees.

The problem is that this fund pays out more in pension checks every year than its current workers and employers contribute. That gap helps explain why it is billions short of what it needs to cover its future retirement promises.

“The bucket is leaking,” he said.

The solution for Mr. Majeed—as well as other pension managers across the country—is to take on more investment risk. His fund and many other retirement systems are loading up on illiquid assets such as private equity, private loans to companies and real estate.

So-called “alternative” investments now comprise 24% of public pension fund portfolios, according to the most recent data from the Boston College Center for Retirement Research. That is up from 8% in 2001. During that time, the amount invested in more traditional stocks and bonds dropped to 71% from 89%. At Mr. Majeed’s fund, alternatives were 32% of his portfolio at the end of July, compared with 13% in fiscal 2001.

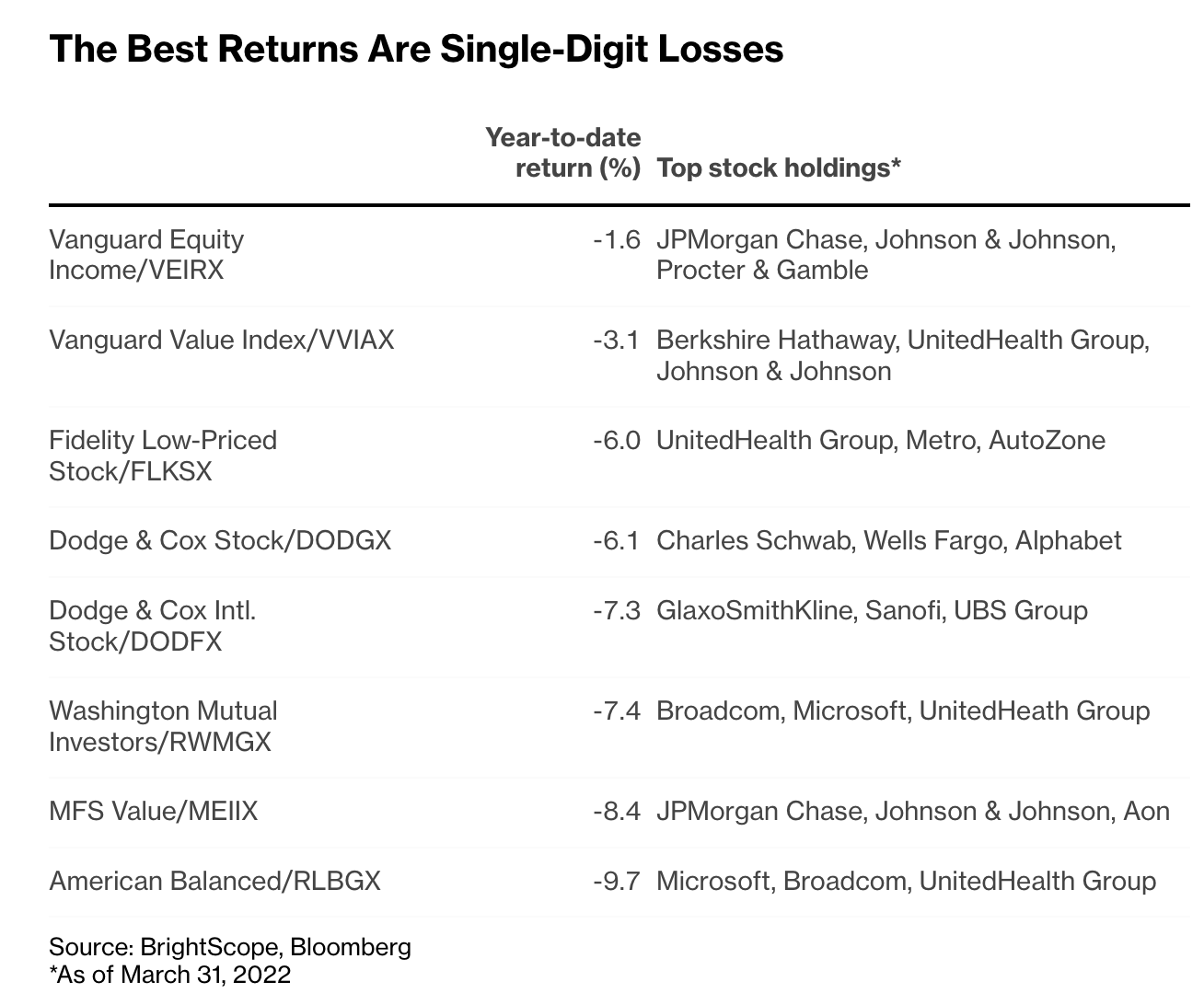

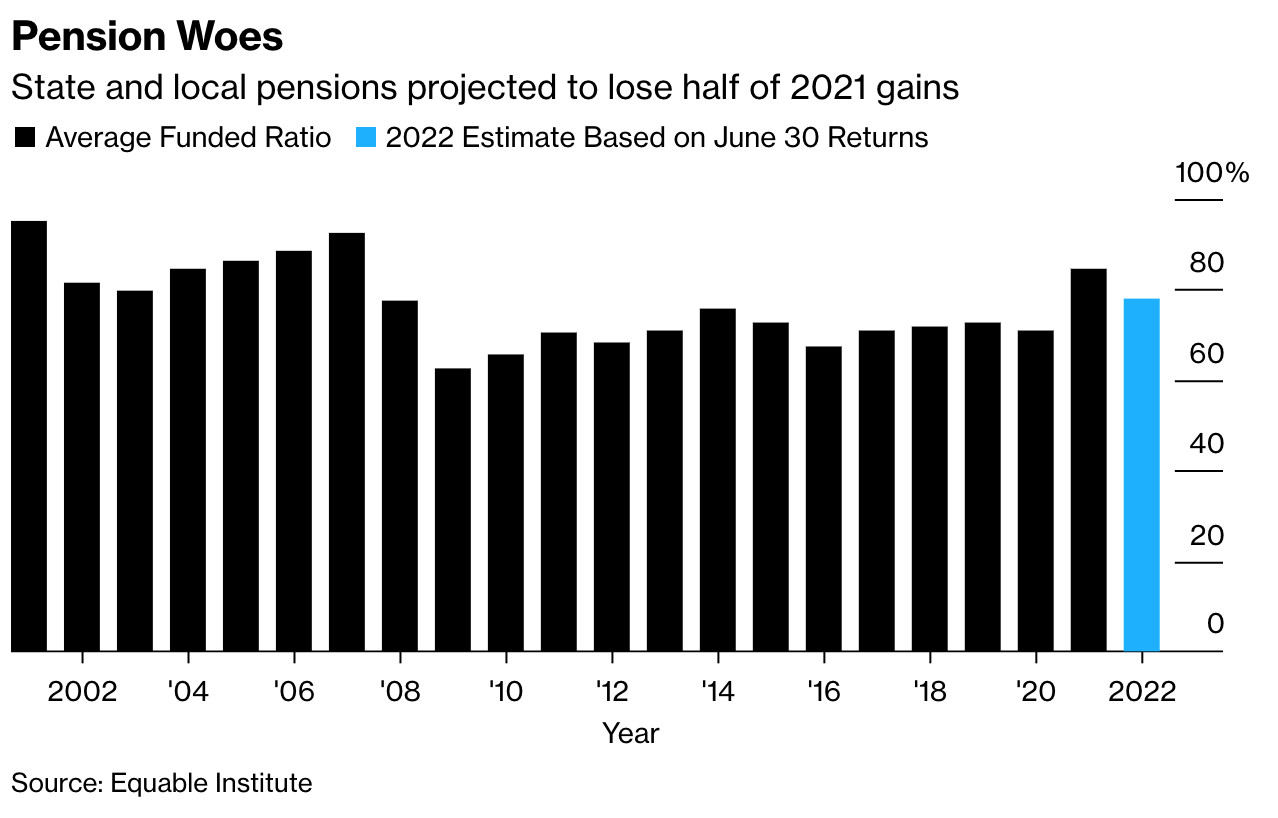

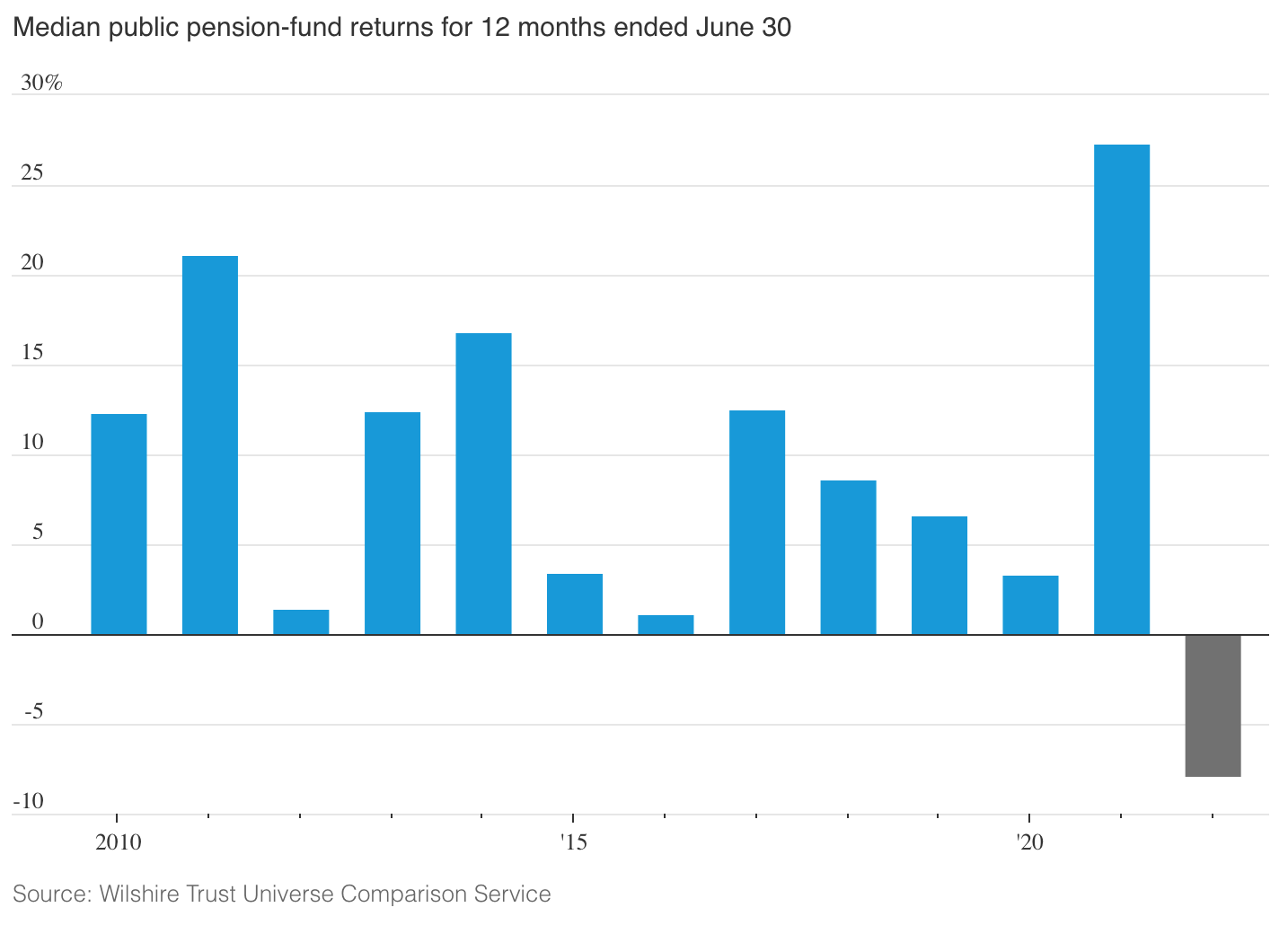

This strategy is paying off in Ohio and across the U.S. The median investment return for all public pension systems tracked by the Wilshire Trust Universe Comparison Service surged to nearly 27% for the one-year period ending in June.

That was the best result since 1986. Mr. Majeed’s retirement system posted the same 27% return, which was its strongest-ever performance based on records dating back to 1994. His private-equity assets jumped nearly 46%.

These types of blockbuster gains aren’t expected to last for long, however. Analysts expect public pension-fund returns to dip over the next decade, which will make it harder to deal with the core problem facing all funds: They don’t have enough cash to cover the promises they made to retirees.

That gap narrowed in recent years but is still $740 billion for state retirement systems, according to a fiscal 2021 estimate from Pew Charitable Trusts.

Digging Out Of A Deep Hole

This public-pension predicament is the result of decades of underfunding, benefit overpromises, unrealistic demands from public-employee unions, government austerity measures and three recessions that left many retirement systems with deep funding holes.

Not even the 11-year bull market that ended with the pandemic or a quick U.S. recovery in 2021 was enough to help pensions dig out of their funding deficits completely.

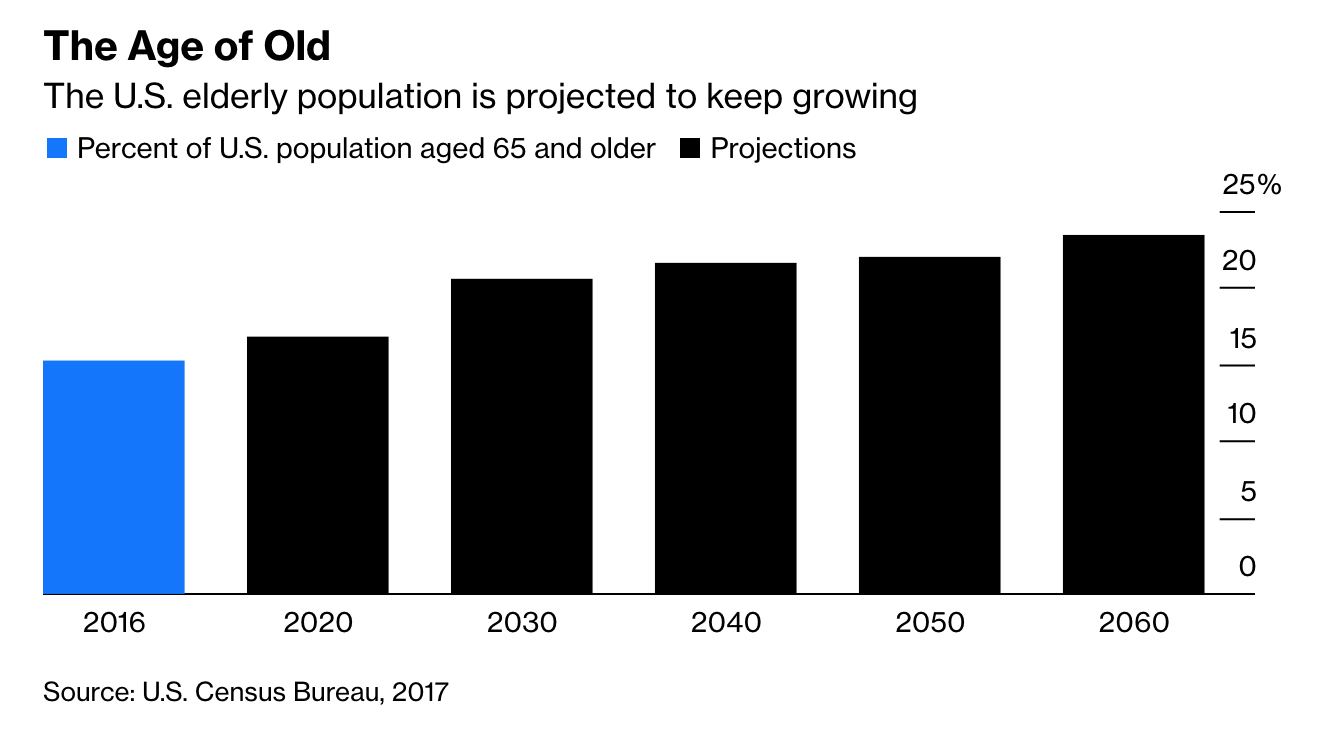

Demographics didn’t help, either. Extended lifespans caused costs to soar. Rich early-retirement arrangements and a wave of retirees world-wide also left fewer active workers to contribute, widening the difference between the amount owed to retirees and assets on hand.

Low interest rates made the pension-funding problem even more difficult to solve because they changed long-held assumptions about where a public system could place its money. Pension funds pay benefits to retirees through a combination of investment gains and contributions from employers and workers.

To ensure enough is saved, plans adopt long-term annual return assumptions to project how much of their costs will be paid from earnings. Those assumptions are currently around 7% for most funds.

There was a time when it was possible to hit that target—or higher—just by buying and holding investment-grade bonds. Not anymore.

The ultra low interest rates imposed by central banks to stimulate growth following the 2008-09 financial crisis made that nearly impossible, and losing even a few percentage points of bond yield hindered the goal of posting steady returns.

Pension officials and government leaders were left with a vexing decision. They could close their funding gaps by reducing benefits for existing workers, cutting back public services and raising taxes to pay for the bulging obligations.

Or, since those are all difficult political choices and courts tend to block any efforts to cut benefits, they could take more investment risk. Many are choosing that option, adding dollops of real estate and private-equity investments to the once-standard bet of bonds and stocks.

This shift could pay off, as it did in 2021. Gains from private-equity investments were a big driver of historic returns for many public systems in the 2021 fiscal year.

The performance helped improve the aggregate funded ratio for state pension plans, or the level of assets relative to the amount needed to meet projected liabilities, to 85.5% for the year through June, Wilshire said. That was an increase of 15.4 percentage points.

These bets, however, carry potential pitfalls if the market should fall. Illiquid assets such as private equity typically lock up money for years or decades and are much more difficult to sell during downturns, heightening the risk of a cash emergency.

Alternative assets have tripped up cities, counties and states in the past; Orange County famously filed for bankruptcy in 1994 after losses of more than $1.7 billion on risky derivatives that went sour.

The heightened focus on alternative bets could also result in heftier management fees. Funds pay about two-and-one-half percentage points in fees on alternative assets, nearly five times what they pay to invest in public markets, according to research from retired investment consultant Richard Ennis.

Some funds, as a result, are avoiding alternative assets altogether. One of the nation’s best-performing funds, the Tampa Firefighters and Police Officers Pension Fund, limits its investments to publicly traded stocks and bonds. It earned 32% in the year ending June 30.

‘It’s Going To Be Very Tough’

It took some convincing for Mr. Majeed, who is 68 years old, to alter the investment mix of the School Employees Retirement System of Ohio after he became its chief investment officer.

When he arrived in 2012, there was a plan under way to invest 15% of the fund’s money in another type of alternative asset: hedge funds. He said he thought such funds produced lackluster returns and were too expensive.

Changing that strategy would require a feat of public pension diplomacy: Convincing board members to roll back their hedge-fund plan and then sell them on new investments in infrastructure projects such as airports, pipelines and roads—all under the unforgiving spotlight of public meetings.

“It’s a tough room to walk into as a CIO,” said fund trustee James Rossler Jr., an Ohio school system treasurer.

It wasn’t Mr. Majeed’s first experience with politicians and fractious boards. He grew up in Sri Lanka as the son of a prominent Sri Lanka Parliament member, and his initial investment job there was for the National Development Bank of Sri Lanka. He had to evaluate the feasibility of factories and tourism projects.

He came to the U.S. in 1987 with his wife, got an M.B.A. from Rutgers University and quickly migrated to the world of public pensions with jobs in Minneapolis, Ohio, California and Abu Dhabi.

In Orange County, Calif., Mr. Majeed helped convince the board of the Orange County Employees Retirement System to reduce its reliance on bonds and put more money into equities—a challenge heightened by the county’s 1994 bankruptcy, which happened before he arrived.

His 2012 move to Ohio wasn’t Mr. Majeed’s first exposure to that state’s pension politics, either; he previously was the deputy director of investments for another of the state’s retirement systems in the early 2000s.

This time around, however, he was in charge. He said he spent several months presenting the board with data on how existing hedge-fund investments had lagged behind expectations and then tallied up how much the fund paid in fees for these bets.

“It was not a pretty picture at that point,” he said, “and these documents are public.”

Trustees listened. They reduced the hedge-fund target to 10% and moved 5% into the real-estate portfolio where it could be invested in infrastructure, as Mr. Majeed wanted.

What cemented the board’s trust is that portfolio then earned annualized returns of 12.4% over the next five years—more than double the return of hedge funds over that period.

The board in February 2020 signed off on another request from Mr. Majeed to put 5% of assets in a new type of alternative investment: private loans made to companies.

“Back when I first got on the board, if you would have told me we were going to look at credit, I would have told you there was no way that was going to happen,” Mr. Rossler said.

The private-loan bet paid off spectacularly the following month when desperate companies turned to private lenders amid market chaos sparked by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Mr. Majeed said he added loans to an airline company, an aircraft engine manufacturer and an early-childhood education company impacted by the widespread shutdowns.

For the year ended June 30, the newly minted loan portfolio returned nearly 18%, with more than 7% of that coming in cash the fund could use to pay benefits. The system’s total annualized return over 10 years rose to 9.15%, well above its 7% target.

Those gains closed the yawning gap between assets on hand and promises made to retirees, but not completely. Mr. Majeed estimates the fund has 74% of what it needs to meet future pension obligations, up from 63% when he arrived.

Mr. Majeed is now eligible to draw a pension himself, but he said he finds his job too absorbing to consider retirement just yet. What he knows is that the pressures forcing a cutthroat search for higher returns will make his job—and that of whoever comes next—exponentially harder.

“I think it’s going to be very tough.”

Updated: 11-6-2021

You’ll Be Able To Put More Money In Your 401(K) Next Year

Americans 50 or older can defer $27,000 to their 401(k) plans in 2022.

Americans will be able to save more in their workplace retirement accounts in 2022, the Internal Revenue Service said on Thursday.

As part of the changes, employees will be able to contribute $20,500 to their 401(k), 403(b), the federal government’s Thrift Savings Plan and most 457 plans in 2022, up from $19,500 in 2021.

The catch-up contribution for workers who are age 50 and older will remain unchanged, at an additional $6,500, so in 2022, an employee participating in one of these workplace plans who is at least 50 years old can defer $27,000 to their account.

The income thresholds for qualifying deductible contributions to traditional IRAs also increased. Americans can always contribute to traditional IRAs, but must meet income limits in order to deduct their contributions for calculating their adjusted gross income if they participate in a workplace retirement savings plan. The income ranges also increased to claim the Saver’s Credit.

In 2022, the income ranges are:

– For single taxpayers, $68,000 to $78,000, up from $66,000 to $76,000

– For couples who are married filing jointly and if both spouses are participating in a workplace retirement plan, $109,000 to $129,000; for the spousal IRA contributions, where one spouse is covered by a workplace plan but the other is not and they are married filing jointly, $204,000 to $214,000.

– For couples who are married filing separately, the range remains at $0 to $10,000.

The contribution limits for IRAs also remained unchanged, at $6,000 with an additional $1,000 for catch-up contributions.

The contribution limits for IRAs also remained unchanged, at $6,000 with an additional $1,000 for catch-up contributions for savers age 50 and older.

The thresholds for Roth IRAs have also increased. Unlike traditional IRAs, workers must meet these thresholds in order to contribute to a Roth IRA.

In 2022, the ranges will be $129,000 to $144,000 for singles and heads of household; $204,000 to $214,000 for married couples filing jointly; and $0 to $10,000 for married couples filing separately.

For the Saver’s Credit, available to low- and moderate-income workers who save for retirement, the limits are: $34,000 for single individuals, $51,000 for heads of household, and $68,000 for married couples filing jointly.

Updated: 11-7-2021

Newly Flush With Cash, Retirement Funds Struggle To Find Appealing Investments

Long-underfunded pension systems share bittersweet challenge with other investors that see hazards in many asset classes.

State and local pension funds are reaping a historic windfall thanks to billions of dollars in record market gains and surplus tax revenues. Now they need to decide what to do with the money.

It is a bittersweet dilemma that the chronically underfunded retirement systems share with many household and institutional investors around the country. Just when they finally have cash to play around with, every investment opportunity seems perilous.

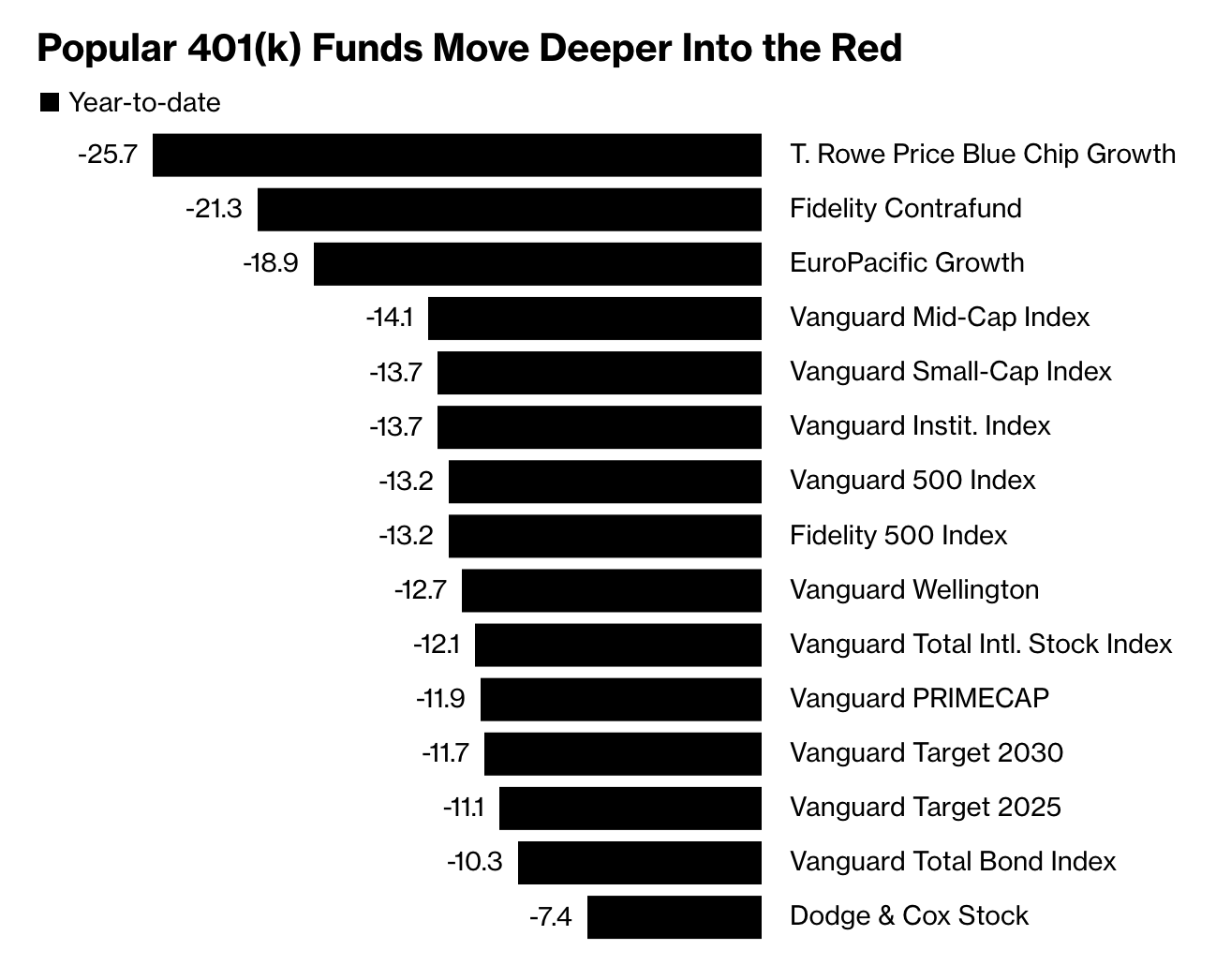

Leave the money in stocks, and a pension fund becomes more vulnerable to the type of losses suffered in the 2008-09 financial crisis. Move the money into bonds for safekeeping, and the fund risks losing even minimal gains to inflation.

Seek out alternative assets to help diversify and drive up returns, and the fund enters a crowded competition for private equity and real estate where it can take years for money to be put to work.

Pension funds and other institutional investors lost 0.06% for the quarter that ended Sept. 30, according to Wilshire Trust Universe Comparison Service data released last week, their first negative return since the early days of the pandemic.

After a year of stimulus-fueled economic gains on the heels of a decadelong bull market, it is hard to find bargains anywhere. That means investment chiefs are choosing where to park their unprecedented windfall in an increasingly volatile and unpredictable world.

“There are things going on that I’ve never seen, ever—people leaving the labor market, office buildings being vacant, ships in the middle of the ocean with cargo,” said Angela Miller-May, chief investment officer for the $55 billion Illinois Municipal Retirement Fund. “Even if you’ve had years and years of investment experience, you’ve never experienced anything like this.”

Ms. Miller-May’s fund swelled by more than $10 billion over the past fiscal year, between market gains and contributions from the towns, cities, school districts and other governments it serves.

The fund has bought close to $1 billion worth of bonds and, since a board decision to increase alternative investments in December, allocated an additional $1.54 billion to private equity and real estate, Ms. Miller-May said. She said about $140 million of that money has been put to work so far.

Around the country, pension managers are competing to reinvest blockbuster gains from the 2021 fiscal year, which injected around $800 billion into state retirement systems alone, according to an estimate by the Pew Charitable Trusts.

The funds, which serve police, teachers and other public workers, still have hundreds of billions of dollars less than needed to cover promised benefits. Even so, they grew more in the 12 months ended June 30 than in any of the past 30 years.

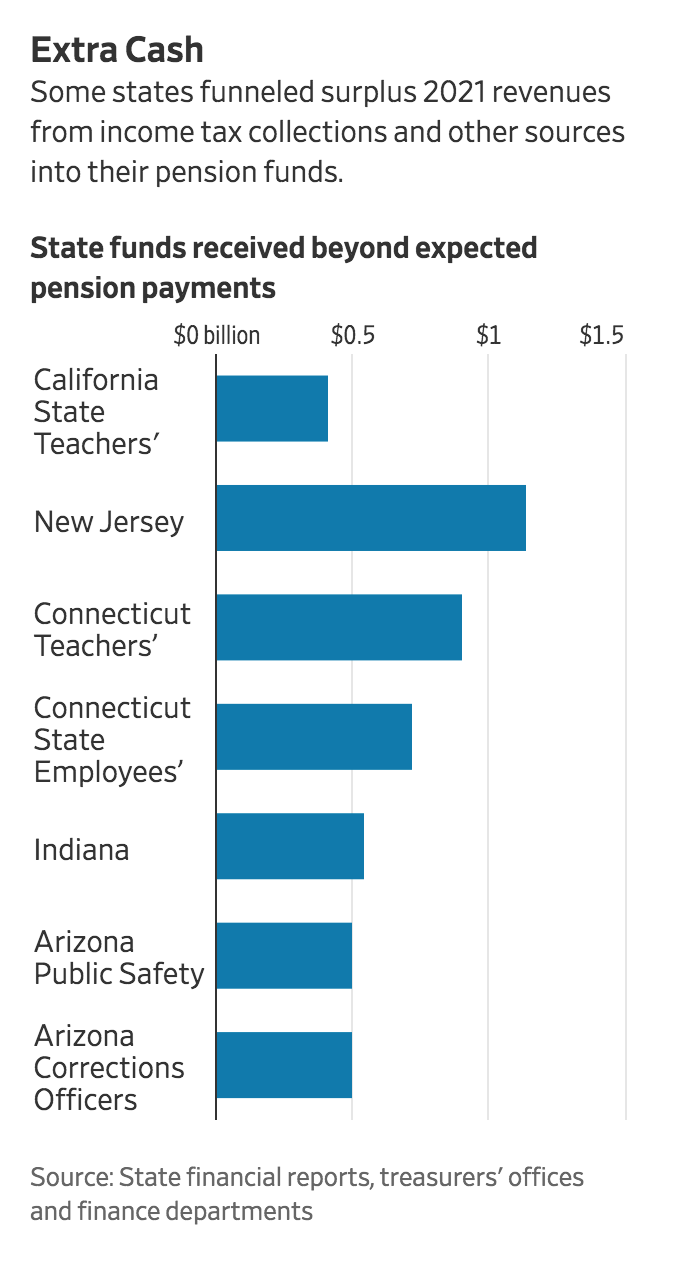

Some pension funds are also getting injections of cash from 2021 state tax collections supercharged by federal stimulus programs.

California transferred an extra $2.31 billion to its teachers’ and public workers’ pension funds after stock gains and the economic recovery bolstered income tax collections, according to budget documents.

Connecticut Treasurer Shawn Wooden is transferring an additional $1.62 billion to that state’s teachers’ and workers’ pension funds in accordance with a mandate that excess revenue be used to pay down debt.

This year New Jersey is making the full pension payment recommended by its actuaries for the first time since 1996, plus an extra half-billion dollars, funneling a total of $6.9 billion to the state’s deeply underfunded retirement plan, the New Jersey treasurer’s office said.

Asked how the money would be used, a spokeswoman for the state’s division of investment said it “will continue to move forward toward the previously established allocation targets.” The $101 billion fund’s private equity, private credit, real estate and real assets portfolios each contained between $1 billion and $3 billion less than the goal amount as of Aug. 31, records show.

New Jersey’s investment division said this fall that it intended to start reinvesting gains from one of its private-equity investments as a way to deploy capital into the asset class more quickly after the fund earned nearly 48% on its private-equity portfolio for the year ended June 30.

Some funds are branching out into new assets. In May, the Jacksonville, Fla., Police and Fire Pension Fund approved the first investment in a recently created $200 million private credit portfolio, a $100 million allocation to Ares Management Corp. The Houston Firefighters’ Relief and Retirement Fund in October bought $25 million worth of bitcoin and ether.

One of the most common moves pension funds are making amid the current windfall, however, isn’t an investment at all.

Instead, retirement systems from South Carolina to Idaho are surveying the market landscape and lowering their investment-return projections at a pace never seen before, said Keith Brainard, research director of the National Association of State Retirement Administrators.

Pension funds have been slowly rolling back those targets for years as a decadeslong drop in bond rates has driven down the amount they can earn on safe fixed-income investments. Several pension officials also said the pandemic-prompted federal funding and market intervention early last year accelerated stock-market gains that otherwise would have unfolded more slowly, reducing expectations for the coming decade.

“There are a lot of questions as to whether the returns are front-loaded and whether they can be sustained,” said Kevin Olineck, director of the Oregon Public Employees Retirement System, which lowered projections to 6.9% from 7.2% last month.

Such reductions aren’t popular with employers and workers, who end up having to pay more into their pension fund to make up the difference, so last year’s windfall makes now a good time to pull the trigger.

Oregon’s move will cost employees and employers about half as much as it otherwise would as a result of the recent gains, Mr. Olineck estimated, assuming no major losses through the end of the fiscal year.

Related

Retirees Spend A Lot Of Time And Money To Buy Their ‘Forever Home.’ Then They Sell It

Updated: 11-15-2021

Prepare To Live On $33,000 A Year If You Retire With A $1 Million Portfolio

The so-called safe withdrawal rate should shrink to 3.3% from 4%, according to a Morningstar report.

A rule of thumb for how much U.S. retirees can “safely” withdraw each year without fear of outliving their savings just got a haircut.

People retiring in the next few decades should only count on withdrawing 3.3% of their savings a year, down from the well-established number of 4%, when planning to live about 30 years past retirement, according to a Morningstar Inc. report published last week.

For someone with a $1 million portfolio, that’s a slide from $40,000 a year to $33,000. With pensions a perk of the past and Social Security benefits at risk of being cut, there’s not much of a safety net for people who run out of their own savings.

While people retiring in the past 15 years or so had a tailwind, today’s retirees face headwinds. “Current conditions demand greater forethought and planning than in the past, when lower valuations and loftier yields paved the way to higher future returns,” the report said.

Morningstar Investment Management’s 30-year inflation-adjusted return forecast for U.S. large-cap stocks is 2.74%. The forecast for investment-grade bonds is -0.11%.

The 4% rule came from a 1994 study that looked at every rolling 30-year period since 1926. It found that retirees with portfolios made up of 50% stocks and 50% bonds could tap an annual amount equal to 4% of their original pot of money, adjusted for inflation, without risk of outliving their money.

Now, 3.3% — which Morningstar said is conservative — is less of a suggestion than a starting point. Most financial planners recommend retirees take a flexible approach, maybe taking out more after the market had a good year and less when the market’s down.

That tends to lead to people spending down most of their money before they die. Sticking to a fixed-percentage withdrawal can leave more for heirs, the report found.

“The key to all of this is that for most retirees it’s a little bit of a mosaic,” said Christine Benz, Morningstar’s director of personal finance. To get a higher safe withdrawal rate, “maybe you delay claiming Social Security for two years, maybe you don’t take a full inflation adjustment every year,” she said.

As well, retirees will want to be strategic about which accounts they withdraw money from each year, since “if portfolio returns are lower, managing for taxes will be more meaningful,” said Benz.

Updated: 11-19-2021

Should You Join Your Spouse In Retirement?

The decision to retire when a spouse does is getting more complicated as couples face inflation headwinds and differing views on spending.

If you’re in your 60s, it may feel like everyone you know is retiring. The number of older workers who quit amid the pandemic shot up, reversing a decades-long trend of lower retirement rates among Americans 55 and older.

But what if your spouse is part of that everyone-you-know cohort? Before you decide whether to join the retirement ranks too, consider the following:

The financial equation is no longer as straightforward as “We’ve saved x” and “We expect to need y” for the next fill-in-the-blank number of years. Low interest rates and greater than expected inflation are moving the goalposts.

The old rule-of-thumb about withdrawing 4% a year in retirement is no longer applicable, and some say 3% is more appropriate. That means you and your spouse may need about 25% more than previously thought.

Inflation headwinds aside, just coming up with an answer to how much a couple expects to need in retirement can be difficult, even for those who have been married for years.

One spouse may have a costly one-off purchase in mind, an expensive hobby, or children or grandchildren from a previous marriage that he or she wants to help financially.

Discussions about that, along with things like anticipated travel and potential relocation, are imperative when calculating future spending.

Wives contemplating retirement should keep in mind that they often have lower lifetime earnings than their husbands because they’ve generally been paid less, do more unpaid caregiving and have accumulated fewer hours of paid work.

That translates into lower retirement wealth overall. Women generally have less money in employer-sponsored retirement plans or pension plans, and receive Social Security benefits that are just 80% of what men receive, on average. (Spouses can elect to receive benefits based on their own earnings or to split their spouse’s benefits.)

It’s also important to think about whether a spouse’s recent retirement was voluntary or involuntary. The answer could have emotional implications as well as financial ones for the couple to consider.

For instance, research shows a forced retirement can increase the risk of depression in women. If it wasn’t by choice, there may be the need to claim Social Security benefits earlier, ultimately decreasing overall total benefits.

Spouses who are much younger than typical retirement ages may want to continue working. One study shows that retiring before an age deemed acceptable by cultural norms can put someone at a higher risk for worse health outcomes. But working well past a traditional retirement age generally doesn’t provide any health benefits.

Working spouses whose retired partners have health issues face a conundrum. They can either quit to be a caregiver, or may feel more pressure to keep working to pay for health-care costs.

They should consider their own health, whether the couple has long-term care coverage and the amount of assistance a sick spouse needs.

Finally, think about the state of your relationship. If partners are close, share hobbies and want more time together, it may make sense to enjoy retirement simultaneously. Still, relationship expert and psychologist David Richo advises that partners in a happy relationship get no more than 25% of their needs from each other. Not working could disrupt that balance – making retirement a lot less enjoyable.

Updated: 11-22-2021

Pension Cash Dwindles, Risking Liquidity Crunch

Cash allocations have dropped to a seven-year low, with pensions seeking greater returns in private markets.

Bigger private-market bets, inflation fears and a surge of retirees are putting public retirement funds at risk of a cash crunch that would force them to sell assets at losses to pay pension checks.

Cash allocations have dropped to a seven-year low at the funds that manage more than $4.5 trillion in retirement savings for America’s teachers, police and firefighters.

Public pension funds, which have increasingly turned to illiquid private markets to drive up returns, are now aiming to keep about 0.8% of their holdings in cash, according to data from the Boston College Center for Retirement Research.

These funds are managing a juggling act faced by many institutional and household investors who want to put their money to work but also want easy access to it in a pinch.

“The first report I look at every day is our cash report,” said Jonathan Grabel, investment chief of the $75 billion Los Angeles County Employees Retirement Association, which aims to keep 1% of its assets in cash. “We have plenty of liquidity across the portfolio, but you never know when and if markets are going to seize up.”

Mr. Grabel’s fund in May reduced its target allocation to investment-grade bonds to 12% from 19% and increased the amount it wants to keep in private equity, infrastructure, and illiquid credit to a combined 29% from 16%. The fund’s long-term expected annual return of 7% is the average for state and local government retirement funds, according to the National Association of State Retirement Administrators.

The $496 billion California Public Employees’ Retirement System, despite aiming for a slightly more conservative 6.8%, still plans to invest more in private markets, borrow against up to 5% of the fund, and keep less cash on hand, to meet that target, under a plan the board approved this month.

Meanwhile, smaller pension funds serving school employees in Ohio, city workers in Illinois and other public employees across the country are putting more of their money into real estate, private equity or private debt.

Public pension funds have hundreds of billions of dollars less on hand than the amount they will need to cover promised benefits after two decades of underfunding, unrealistic demands from public-employee unions, and losses during the 2007-2009 financial crisis.

Over the same period, their cash-flow margins have thinned as retirees have multiplied relative to the number of current workers. In Connecticut, for example, more than a quarter of the state workforce are eligible to retire between June 2020 and June 2022, Boston Consulting Group found.

Public pension funds have historically been able to access cash when equity markets faltered by selling bonds. But over the past two decades, fixed income portfolios shrank to 24% of assets from 33%, according to the Boston College data, as falling rates turned bonds into a drag on returns. Now inflation threatens to further erode the value of fixed-income investments.

But assets that promise rapid growth—from common stocks to complex alternative investments—also carry the risk of losses when sold into rocky markets or before maturity.

After the Pennsylvania Public School Employees’ Retirement System last year decided to shrink its private equity allocation, in part to increase liquidity, consultants warned that selling assets early would mean accepting an average discount of 15% of net asset value.

Some growth strategies can also require sudden diversions of cash in the form of capital calls and margin calls, often at inconvenient times.

When markets cratered in 2008, some of the biggest U.S. pension funds sold stocks to raise cash and fund capital calls from private-equity firms. In the aftermath many, including Calpers and the California State Teachers’ Retirement System reviewed their allocations to alternatives.

A Calpers spokesman said the fund has improved liquidity management since the financial crisis and as a result was able to take advantage of low prices during the market dislocation in March 2020 at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Calpers staff said at a meeting earlier this month that the fund uses a dashboard to closely monitor liquidity, which is a measure of how easily holdings can be converted to cash without losses.

The retirement fund, which is the nation’s largest, eliminated its target of holding 1% of its assets in cash as part of the new asset allocation approved this month, which takes effect July 1, 2022.

Finding a strategy that can accomplish what bonds once did, providing yield in good times and accessible cash in bad, is “not a problem with an easy solution,” said Ash Williams, who recently retired as executive director and chief investment officer of the State Board of Administration, which manages investments for the Florida Retirement System.

“Everybody’s wrestling with this same thing,” he said.

Updated: 11-24-2021

Counting Calories Helps Your Retirement Account, Too

A healthy diet is one of the most effective ways to protect retirement savings.

Before those celebrating Thanksgiving reach for a second slice of pecan pie, they should consider this: A 55-year-old woman with Type 2 diabetes will pay an average of $3,470 more a year in medical-related expenses, or close to $160,000 in total, than if she didn’t have the disease.

A one-time indulgence on a holiday certainly won’t result in diabetes, but it’s a good reminder that making the right food choices over time can have just as much of an impact on retirement savings as market forces and investment decisions.

Minimizing the costs of aging is equally as, if not more than, important as maximizing retirement income.

Type 2 diabetes (along with its precursor, pre-diabetes) are prime examples since they’re largely preventable by eating right and staying active.

Those who suffer from them get hit financially because they don’t necessarily shorten life expectancy; they allow people to live but with expensive health-related conditions — often incurring out-of-pocket costs that may not be covered by Medicare or insurance companies.

One study of Medicare beneficiaries showed that prescription medicine is the biggest driver of additional out-of-pocket costs for heart disease, diabetes and high blood pressure. Those with diabetes are also more likely to require costly organ transplants or long-term care, which Medicare doesn’t cover.

Many people ask me for financial advice when it’s nearly too late. A 53-year-old colleague admitted she had no retirement savings and asked what she could do. Telling her to save 50% of her earnings to adequately supplement Social Security seemed cruel and unrealistic. So, I pivoted. I concentrated my tips on how she could reduce expenses as she gets older.

The most direct and cheapest is to avoid the preventable diseases that will drain your wallet. Let’s call it downsizing.

Another important and easy way to minimize health-related costs is to take your medicine. Only about 50% of U.S. adults who suffer from a chronic condition take their medications as prescribed.

While some may not take medicine because it’s too expensive, skipping it can often wind up being far more costly following emergency-room visits and other avoidable medical expenses.

Sadly, most retirement advisers don’t usually focus on how dietary and other lifestyle changes can help to avoid costly chronic conditions. And medical professionals don’t talk about financial issues enough. Daniel Levitin, a neuroscientist and aging expert, wrote a bestselling book last year called “Successful Aging,” but he hardly mentioned money. I realized that the books I write about money barely mention health. We’re both wrong.

More than half of baby boomers now say they’re worried they won’t be able to cover medical expenses in retirement. They should remember that rethinking their meal choices at Thanksgiving and beyond could go a long way toward making their retirement more comfortable.

Updated: 11-27-2021

How To Explain The Increased Percentage Of Retired People?

Fewer people are ‘unretiring,’ but that will likely change.

This stuff about older workers is driving me crazy. I thought we had a narrative, and then we got some new information.

Our basic story has been that older workers, like all workers, were hurt by the pandemic and ensuing recession. Their experience was a little worse than that of prime-age workers, but not as bad as that of younger workers.

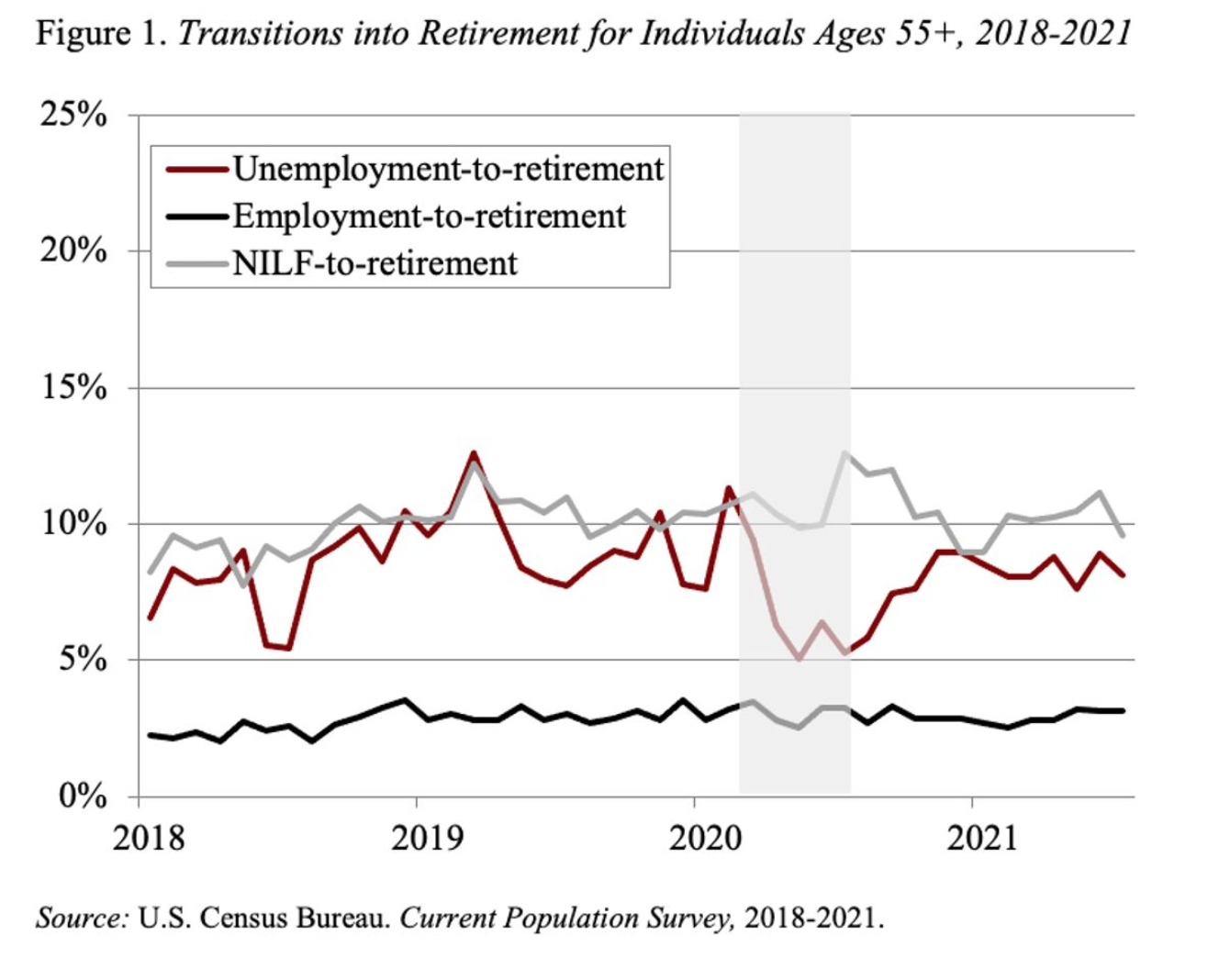

Some older workers returned to the labor force as the economy improved, but a large number remained “not in the labor force.”

Interestingly, we have not seen any uptick in self-reported retirement (see Figure 1). Month-to-month transitions from employment to retirement and from not-in-the-labor-force (NILF) to retirement have both been flat, and transitions from unemployment to retirement have, if anything, declined from pre-pandemic levels.

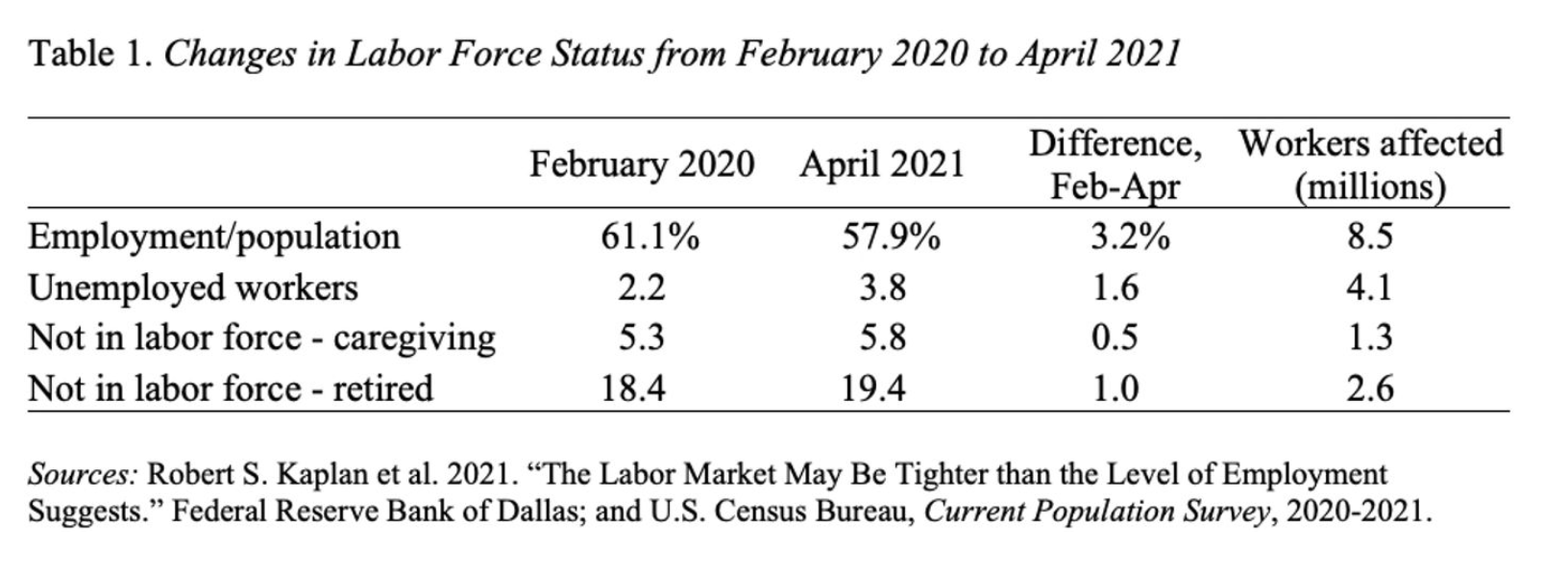

OK. Then along comes the Dallas Fed exploration of the decline in the ratio of employment to population, showing that 1.0 percentage points of the 3.2-percentage-point decline can be explained by higher retirements (see Table 1). They calculated that 0.4 percentage points can be attributed to the aging of the population and the additional retirements account for 0.6 percentage points or 1.5 million workers.

Suddenly, we have an uptick of 1.5 million retirees, as shown in Figure 2. It’s really a funny phenomenon, however, since the hot labor market of 2018 and 2019 caused many older workers to delay retirement, resulting in a ratio of retirees to population below what 2017 retirement rates would have predicted for the aging population.

Nevertheless, it’s still really annoying since we had not seen an increase in people moving into retirement.

If people are not moving into retirement, how can the ratio of retirees to population tick up? Fortunately, a piece by the Kansas City Fed provides an answer.

Similarly, the line covering retired workers who have started to look for work but are not yet employed also held steady. The really interesting pattern is that the red line — those moving from retirement to work — dropped sharply with the onset of the pandemic and has remained low.

That is, the COVID-19 uptick was driven not by an increase in the number of employed people transitioning into retirement, but by a decline in the number “unretiring” — that is rejoining the labor force.

Will the “unretiring rate” pick up? Two factors suggest it will. First, the retirement -to-employment rate did not plummet during the Great Recession, which suggests the drop in early 2020 reflected health concerns related to the pandemic.

As the health risk recedes, more people may come out of retirement to work. Second, the increase in the share retired included 1.2 million people under age 68, who are likely quite capable of work.

I wish that I had figured this out, but as an old Fed person I’m delighted our central bank is on the case.

Updated: 11-30-2021

Billions Of Lost Retirement Dollars Are Getting Harder To Find

The demise of a public database and struggles to obtain government information crimp efforts to unite plan participants with unclaimed benefits.

People hunting for old retirement plans are facing new obstacles.

Fraud concerns have prompted one federal agency, the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp., to take down a public database that previously helped retirement-plan participants track down their benefits, a PBGC spokesperson said in a statement to MarketWatch.

Many people searching for lost retirement money have also lately had trouble obtaining key information that the Social Security Administration typically provides about private retirement benefits, according to pension counselors who assist plan participants.

The new challenges come at a time when the pandemic is expected to exacerbate the longstanding problem of retirement plan sponsors losing track of their participants. COVID-related job loss, combined with failing businesses struggling to keep updated participant records, may lead to more “missing” participants—those whom plan sponsors can’t locate when it comes time to claim benefits, according to a May report from the Government Accountability Office.

The pandemic-related problems and diminished access to retirement-plan search tools mean that workers may struggle to locate their retirement money when they need it most, says Jennifer Anders-Gable, managing attorney at the Western States Pension Assistance Project, a pension counseling organization.

Regulators and lawmakers in recent years have increasingly focused on connecting workers with unclaimed retirement money. The Labor Department’s Employee Benefits Security Administration, which oversees private retirement plans, has pushed plan sponsors to maintain accurate participant records.

The government agency’s enforcement efforts in fiscal year 2021 helped defined-benefit pension plan participants collect more than $1.5 billion worth of benefits owed to them, up from about $327 million in fiscal 2017.

Several bills introduced in Congress this year call for the creation of a retirement savings “lost and found,” an online plan registry where pension and 401(k) participants could search for their plans.

‘We need an Ancestry.com for pension plans’

Job-hopping, corporate name changes, mergers, plan terminations and other factors contribute to workers and retirement plans losing track of each other, experts say.

There is more than $1.3 trillion in “forgotten” 401(k) accounts participants have left behind when leaving an employer, estimates Capitalize, a financial technology company focused on retirement-account rollovers.

“We need an Ancestry.com for pension plans” to help connect the dots, says Tom Reeder, former PBGC director and board member of the Pension Rights Center, a nonprofit consumer group.

Although plan administrators are obligated to keep up-to-date participant records, some pension plans have records with obvious data flaws—such as “John Doe” placeholder names—or simply delete names of unresponsive participants, according to the Labor Department.

The pandemic and diminished access to retirement-plan search tools mean that workers may struggle to locate their retirement money when they need it most.

The now-defunct PBGC public database was a critical part of the solution, pension counselors say. For people trying to locate lost plans, “a lot of times, the only way to track down the benefit is by going to the PBGC,” says Anna-Marie Tabor, director and managing attorney at the Pension Action Center at the University of Massachusetts Boston.

The database included benefits and accounts from terminated plans, and participants could do a quick search to find out whether retirement money was being held for them.

PBGC removed the database from its website in 2020 “to prevent bad actors from using the information to facilitate fraudulent activity,” the PBGC spokesperson said.

The agency “is not aware of specific instances of fraud” originating from the database, and there was no security breach involving the online tool, the spokesperson said. Plan participants looking for unclaimed benefits can still call the PBGC for help at 1-800-326-5678.

The demise of the search tool raises questions about legislative efforts to create a more comprehensive, searchable online plan registry.

The Retirement Savings Lost and Found Act introduced earlier this year by Massachusetts Democratic Senator Elizabeth Warren and Montana Republican Senator Steve Daines, for example, calls for the PBGC to manage an online searchable database that would help individuals find contact information for their retirement plan administrator.

Asked about the fraud concerns raised by the PBGC, a Daines aide said that the online registry envisioned by the Retirement Savings Lost and Found Act “probably needs to be moved from PBGC” to another agency—potentially the Treasury Department.

“Cybersecurity threats are on the rise, and not everyone is as prepared as Treasury,” the aide said.

The struggle to obtain critical plan information from the Social Security Administration

Pension counselors who assist plan participants in roughly a dozen states, meanwhile, say that many of their clients have lately struggled to obtain critical plan information that’s typically provided by the Social Security Administration.

The agency sends notices to people who may be entitled to retirement benefits from a private employer, listing the plan name, administrator’s address, value of the account and other details. The notice is generally sent automatically to those claiming Social Security benefits and upon request to others searching for their plan details.