$5 Billion A Year Market For DisInformation (#GotBitcoin?)

Aglaya’s latest product, dubbed SpiderMonkey, a device that detects “Stingrays” or IMSI-catchers, the surveillance gizmos used by police and intelligence around the world to track and intercept cellphone data. $5 Billion A Year Market For DisInformation (#GotBitcoin?)

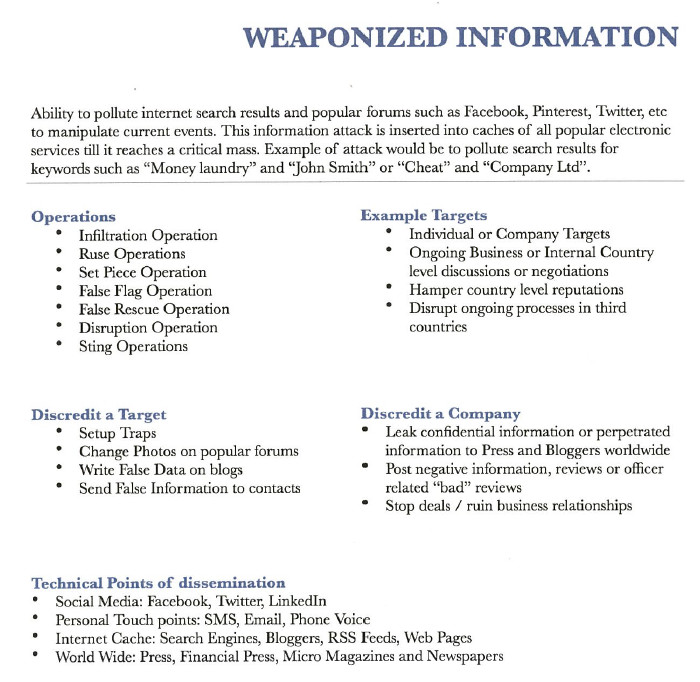

But Aglaya had much more to offer, according to its brochure. For eight to 12 weeks campaigns costing €2,500 per day, the company promised to “pollute” internet search results and social networks like Facebook and Twitter “to manipulate current events.” For this service, which it labelled “Weaponized Information,” Aglaya offered “infiltration,” “ruse,” and “sting” operations to “discredit a target” such as an “individual or company.”

In the summer of 2014, a little known boutique contractor from New Delhi, India, was trying to crack into the lucrative $5 billion a year market of outsourced government surveillance and hacking services.

To impress potential customers, the company, called Aglaya, outlined an impressive—and shady—series of offerings in a detailed 20-page brochure. The brochure offers detailed insight into purveyors of surveillance and hacking tools who advertise their wares at industry and government-only conferences across the world.

The leaked brochure, which had never been published before, not only exposes Aglaya’s questionable services, but offers a unique glimpse into the shadowy backroom dealings between hacking contractors, infosecurity middlemen, and governments around the world which are rushing to boost their surveillance and hacking capabilities as their targets go online.

The sales document also outlines how commonplace commercial spy tools have become. For €3,000 per license, the company offered Android and iOS spyware, much like the malware offered in the past by the likes of Hacking Team, FinFisher, and, more recently, the NSO Group, whose iPhone-hacking tool was just caught in the wild last week. For €250,000, the company claimed it could track any cell phone in the world.

These were standard services offered by a plethora of companies who often peddle their wares at ISS World, an annual series of conferences that are informally known as the “Wiretappers’ Ball.”

“[We] will continue to barrage information till it gains ‘traction’ & top 10 search results yield a desired results on ANY Search engine,” the company boasted as an extra “benefit” of this service.

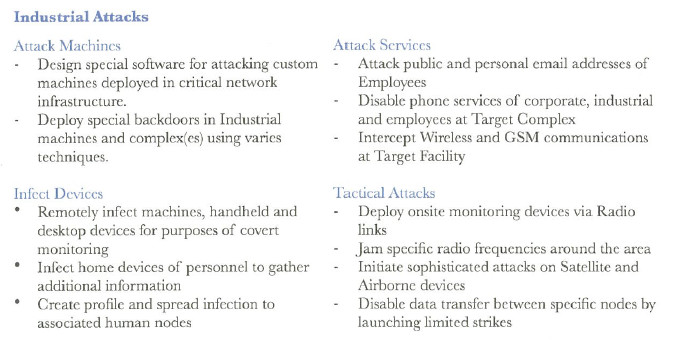

Aglaya also offered censorship-as-a-service, or Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks, for only €600 a day, using botnets to “send dummy traffic” to targets, taking them offline, according to the brochure. As part of this service, customers could buy an add-on to “create false criminal charges against Targets in their respective countries” for a more costly €1 million.

Also starting at €1 million, customers could purchase a “Cyber Warfare Service” to attack “manufacturing” plants, the “power grid,” “critical network infrastructure,” and even satellites and airplanes. Aglaya even claimed to sell unknown flaws, or zero-days, in Siemens industrial control systems for €2 million.

Some of Aglaya’s offerings, according to experts who reviewed the document are likely to be exaggerated or completely made-up. But the document shows that there are governments interested in these services, which means there will be companies willing to fill the gaps in the market and offer them.

“Some of this stuff is really, really, sketchy,” Christopher Soghoian, the principal technologist at the American Civil Liberties Union, who has followed the booming market of surveillance tech vendors for years. “When you’re offering the ability to attack satellites and airplanes, this is not lawful intercept. This is basically ‘whatever you want we’ll try to do it.’ These guys are clearly mercenaries, what’s not clear is if they can deliver on their promises. This is not a company pretending that it’s solely focusing on the lawful intercept market, this is outsourcing cyber operations.”

Ankur Srivastava, the CEO and founder of Aglaya, did not deny that the brochure is legitimate, only saying this particular product sheet was passed on only to “one particular customer.”

“These products are not on our web site, with our customers and nor do they represent the vision of our product portfolio,” Srivastava said in an email. “This was a custom proposal for one customer only and was not pursued since the relationship did not come to fruition.”

Srivastava added that he regretted attending ISS because Aglaya was never able to close a deal and sell its services. He also claimed that the company doesn’t offer those kind of services anymore. (One of the organizers of ISS World did not respond to a request for comment, asking whether the conference vetted or condoned companies offering such services.)

“I would go the distance to aim to convince you that we are not a part of this market and unintentionally underwent a marketing event at the wrong trade-show,” he added.

When asked a series of more detailed questions, however, Srivastava refused to elaborate, instead reiterating that Aglaya never did any business as a government hacking contractor and that attending ISS was “an exercise of time and money, albeit, in futility.” He complained that his company’s failure was likely due to the fact that it is not based “in the West,” hypothesizing that most customers want “western” suppliers.

Asked for the identity of the potential customer who showed interest for these services, Srivastava said he did not know, claiming he only dealt with a reseller, an “agent” from South America who “claimed to have global connections” and “was interested in anything and everything.”

The document itself doesn’t offer any clues as to the country interested. But Latin American governments such as the ones in Mexico and Ecuador are known to have used Twitter bots and other tactics to launch disinformation campaigns online, much like the ones Aglaya was offering. Mexico, moreover, is a well-known big-spender when it comes to buying off-the-shelf spyware made by the likes of Hacking Team and FinFisher.

Srivastava also dodged questions about his company’s spyware products. But a source who used to work in the surveillance tech industry, who asked to remain anonymous to discuss sensitive issues, claimed to have seen a sample of Aglaya’s malware in the wild.

“It was crap,” the source said. “The code was full of references to Aglaya.”

One of his customers was targeted with it at the end of last year, when he received a new phone via mail, under the pretense that he had won a contest that turned out to be made up, according to the source. As ridiculous as this might be, this is actually how Aglaya targeted victims, given that they couldn’t admittedly get around Apple’s security measures and jailbreak the device to infect it with malware.

This sloppy workaround was described in an article in the spyware trade publication Insider Surveillance.

“For installation, Aglaya iOS Backdoor requires an unattended phone and a passcode,” the article read. “By ‘unattended’ we’re hoping they mean ‘idle,’ not ‘impounded.’ Or that they’re not expecting agents to sneak into the target’s bedroom to plant the malware…or wait for him to divulge the password while talking in his sleep.”

The anonymous source, in any case, said that there is certainly a market for the services offered by Aglaya, including the sketchier ones.

“I think it’s credible that there is interest for these type of services at least in certain countries in the Middle East,” the source said.

Another source, who also requested anonymity to speak freely, said that an Aglaya representative once claimed that his company had customers in the Middle East. The source also said that Aglaya’s claims of having abandoned the surveillance tech business are “a lie,” adding that he has seen an updated version of that brochure last year.

Aglaya might have some customers, but it’s likely a small fish in the surveillance and hacking business. There are certainly many more companies, likely with better services and more customers, that we don’t know about. We also might never know about them, unless they get caught because customers abuse their tools—as in the cases of NSO Group and Hacking Team—or their marketing materials leak online.

Often, these companies peddle both defensive and offensive services. Srivastava, after dodging most of our questions, offered to let us take a look at Aglaya’s latest product, dubbed SpiderMonkey, a device that detects “Stingrays” or IMSI-catchers, the surveillance gizmos used by police and intelligence around the world to track and intercept cellphone data.

“Please do keep us in mind,” he said, likely repeating a line that he told his unknown “one” customer two years ago.

Updated: 1-7-2020

Facebook Bans Deepfakes but Permits Some Altered Content

The social-media giant seeks to combat misleading content altered with artificial-intelligence tools.

Facebook Inc. FB 0.22% is banning videos that have been manipulated using advanced tools, though it won’t remove most doctored content, as the social-media giant tries to combat disinformation without stifling speech.

But as with many efforts by social-media companies to address content on their sites that is widely seen as problematic, Facebook’s move swiftly drew criticism for not going far enough and having too many loopholes.

The policy unveiled Monday by Monika Bickert, Facebook’s vice president for global policy management, is the company’s most concrete step to fight the spread of so-called deepfakes on its platform.

Deepfakes are images or videos that have been manipulated through the use of sophisticated machine-learning algorithms, making it nearly impossible to differentiate between what is real and what isn’t.

“While these videos are still rare on the internet, they present a significant challenge for our industry and society as their use increases,” Ms. Bickert said in a blog post.

Facebook said it would remove or label misleading videos that had been edited or manipulated in ways that would not be apparent to the average person. That would include removing videos in which artificial intelligence tools are used to change statements made by the subject of the video or replacing or superimposing content.

Social-media companies have come under increased pressure to stamp out false or misleading content on their sites ahead of this year’s American presidential election.

Late last year, Alphabet Inc. ’s Google updated its political advertisement policy and said it would prohibit the use of deepfakes in political and other ads. In November, Twitter said it was considering identifying manipulated photos, videos and audio shared on its platform.

Facebook’s move could also expose it to new controversy. It said its policy banning deepfakes “does not extend to content that is parody or satire, or video that has been edited solely to omit or change the order of words.” That could put the company in the position of having to decide which videos are satirical, which aren’t and where to draw the line on what doctored content will be taken down.

Henry Ajder, head of research analysis at cybersecurity startup Deeptrace, said deepfakes aren’t expected to be a big problem ahead of the election because the technology to make them hasn’t advanced enough. “That’s why some people think Facebook is focused on the long-term problem while neglecting to tackle the problem that’s right here right now.”

Facebook has already been trying to walk a thin line on other content moderation issues ahead of this year’s presidential election. The company, unlike some rivals, has said it wouldn’t block political advertisements even if they contain inaccurate information. That policy drew criticism from some politicians, including Sen. Elizabeth Warren, a Democratic contender for the White House. Facebook later said it would ban ads if they encouraged violence.

A Facebook spokeswoman said the company’s ban of deepfake videos will apply to political ads and they will be removed.

The new policy also marks the latest front in Facebook’s battle against those who use artificial intelligence to spread messages on its site. Last month, the company took down hundreds of fake accounts that used AI-generated photos to pass them off as real.

In addition to Facebook’s latest policy on deepfakes, which generally rely on AI tools to mask that the content is fake, the company also will continue to screen for other misleading content. It will also review videos that have been altered using less sophisticated methods and place limits on such posts.

The Facebook ban wouldn’t have applied to an altered video of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi. That video of a speech by Mrs. Pelosi—widely shared on social media last year—was slowed down and altered in tone, making her appear to slur her words. Facebook said the video didn’t qualify as a deepfake because it used regular editing, though the company still limited its distribution because of the manipulation.

Hany Farid, a computer science professor at the University of California, Berkeley called Facebook’s announcement “a positive step,” though one, he said, that was also too narrow. “Why focus only on deepfakes and not the broader issue of intentionally misleading videos?” he said, pointing to Facebook’s decision not to remove the altered video involving Ms. Pelosi and a similar one about former Vice President Joe Biden. “These misleading videos were created using low-tech methods and did not rely on AI-based techniques, but were at least as misleading as a deepfake video of a leader purporting to say something that they didn’t.”

Facebook’s Ms. Bickert, in the blog post, said, “If we simply removed all manipulated videos flagged by fact-checkers as false, the videos would still be available elsewhere on the internet or social-media ecosystem. By leaving them up and labeling them as false, we’re providing people with important information and context.”

Updated: 10-10-2020

Want To Fight Online Voting Misinformation? A New Study Makes A Case For Targeting Trump Tweets

Research suggests disinformation starts at the top.

As the 2020 presidential election approaches, social networks have promised to minimize false rumors about voter fraud or “rigged” mail-in ballots, a mostly imaginary threat that discourages voting and casts doubt on the democratic process. But new research has suggested that these rumors aren’t born in the dark corners of Facebook or Twitter — and that fighting them effectively might involve going after one of social media’s most powerful users.

Last week, Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center put forward an illuminating analysis of voting misinformation. A working paper posits that social media isn’t driving most disinformation around mail-in voting. Instead, Twitter and Facebook amplify content from “political and media elites.” That includes traditional news outlets, particularly wire services like the Associated Press, but also Trump’s tweets — which the paper cites as a key disinformation source.

The center published the methodology and explanation on its site, and co-author Yochai Benkler also wrote a clear, more succinct breakdown of it at Columbia Journalism Review. The authors measured the volume of tweets, Facebook posts, and “open web” stories mentioning mail-in voting or absentee ballots alongside terms like fraud and election rigging. Then, they looked at the top-performing posts and their sources.

The authors overwhelmingly found that spikes in social media activity echoed politicians or news outlets discussing voter fraud. Some spikes involved actual (rare) cases of suspected or attempted fraud. But “the most common by far,” Benkler writes, “was a statement Donald Trump made in one of his three main channels: Twitter, press briefings, and television interviews.”

In other words, during periods where lots of people were tweeting or posting on Facebook about the unfounded threat of mass mail-in voting fraud, they were most often repeating or recirculating claims from the president himself. The authors themselves aren’t directly calling to pull Trump’s content from Twitter, and as noted above, that’s not the only way he communicates. But they offer lots of evidence that his tweets — and the resulting press coverage — provide major fuel for misinformation.

One of the highest peaks on all three platforms came in late May — just after Trump tweeted that there is “zero” chance mail-in ballots will be “anything less than substantially fraudulent.”

Another appeared at the end of August, when Trump warned that 2020 would be “the most inaccurate and fraudulent election in history.” (It should go without saying that there’s no evidence for either claim.) The biggest Twitter-specific spike arrived amid a flurry of Trump tweets, press briefings, and Fox News segments in April.

“We have been unable to identify a single episode” of major election fraud posting that was “meaningfully driven by an online disinformation campaign” without an “obvious elite-driven triggering event,” the authors write. And often, those triggering events were clear disinformation — baseless claims that mail-in voting was dangerous.

As the authors note, voter fraud story patterns don’t necessarily generalize across other topics. QAnon-specific conspiracies, for instance, were clearly generated online and only later condoned by politicians like Trump. Some coronavirus misinformation has come from non-mainstream conspiracy videos like Plandemic, although Trump played a key role in promoting experimental hydroxychloroquine treatments as a “miracle” cure, as well as purveying more general COVID-19 misinformation.

The study is a working paper, not a peer-reviewed publication — although Stanford Internet Observatory researcher Alex Stamos tweeted that it “looks consistent” with other work on election disinformation. It also doesn’t necessarily exonerate social media as a concept. Twitter’s design, for instance, encourages the kind of blunt, off-the-cuff statements that Trump has turned into misinformation super-spreader events.

He could still use press conferences and interviews to set the tone of debate, but without Twitter, he wouldn’t have access to a powerful amplification system that encourages his worst impulses.

Similarly, the authors acknowledge that hyperbolic, misleading online news can spread widely across social networks. “Looking at the stories that were linked to by the largest number of Facebook groups over the course of April 2020 certainly supports the proposition that social media clickbait is alive and well on the platform,” the study says.

But they argue that these “clickbait” outlets are echoing stories set by more powerful politicians and news outlets — not driving American politics with “crazy stories invented by alt-right trolls, Macedonian teenagers, or any other nethercyberworld dwellers.” Far from being filled with specific “fake news” stories, Trump’s tweets (and the equivalent messages he posts on Facebook) often don’t even mention specific incidents of fraud, real or imagined.

Even with its caveats, the work indicates that it’s valuable to look beyond the threats of social media trolling campaigns and recommendation algorithms — if only because that offers more concrete solutions than demanding nebulous and potentially impossible crackdowns on all false information.

Facebook and Twitter periodically tout the removal of foreign “coordinated inauthentic behavior” networks, and in the lead-up to the presidential election, Facebook announced that it would temporarily stop accepting political ads on its network. But while these broad-reaching efforts may end up being helpful, the Harvard study implies that pulling a few specific levers might be more immediately effective.

If this research is accurate, a primary lever would be limiting the president’s ability to spread misinformation. “Donald Trump occupies a unique position in driving the media agenda,” the authors contend, and his appearances on new and old media alike have “fundamentally shaped the debate over mail-in voting.”

Twitter has taken steps toward fighting this, restricting the ability to like or retweet some of Trump’s misleading claims. Facebook’s response has been much weaker, simply adding a generic link to its Voting Information Center. But this research makes an indirect case for treating Trump as a deliberate serial purveyor of disinformation — an offense that would get many lower-profile accounts banned.

Other solutions are outside the scope of social media. The authors write, for instance, that smaller newspapers and TV stations rely on syndicated newswire services, and that Americans tend to trust these sources more than national news outlets. The AP and similar publications are centralized institutions controlled by traditional journalists. And the authors were less than impressed by the way they framed mail-in voting stories, criticizing syndicated outlets for creating a sense of false balance or a “political horse race” instead of pointing out false claims.

This isn’t a new criticism, nor one that’s restricted to voting. This spring, some TV networks stopped airing Trump’s rambling and misinformation-filled briefings on the coronavirus pandemic. But Harvard’s research methodically examines just how influential the president’s messaging is online.

Even if Trump loses the election in November, there’s a valuable lesson here for news outlets and social media sites. If a public figure establishes a clear pattern of bad behavior, refusing to let them spread false statements might be just as effective as looking for underhanded disinformation campaigns. On social media, the worst trolls aren’t legions of conspiracy theorists or Russian operatives hiding in the dark corners of the web — they’re politicians standing in plain sight.

Moderation at scale is incredibly technologically difficult. But this study suggests platforms could also just straightforwardly ban (or otherwise limit) powerful super-spreaders, especially if traditional media outlets also reevaluate what they’re amplifying. If more research backs up this idea, then the most immediate disinformation fix isn’t urging platforms to develop sophisticated moderation structures. It’s pushing them to apply simple rules to powerful people.

Updated: 10-13-2020

Online Disinformation Campaigns Undermine African Elections

Some governments use social media to dominate the narrative around campaigns.

In the runup to Guinea’s elections on Oct. 18, voters are grappling with a familiar-sounding problem: disinformation and a lack of transparency over who’s providing the news they’re getting.

In the U.S., similar complaints led to a crackdown on campaigns such as those staged by Russia during the 2016 presidential vote, won by Donald Trump. This election cycle, Facebook has banned new political ads in the week before Election Day on Nov. 3 and—following Google’s example—indefinitely after, while Twitter has also pledged to better police misleading information.

But in Guinea, a West African nation of 13 million that was under authoritarian rule until democratic elections in 2010, social media platforms are a powerful tool for the government—not some foreign entity—to dominate the narrative around the campaign.

The internet has become a welcome space for Africans to gain access to information and join political debates. A recent survey across 14 African countries found that 54% of young people read news on social media, and a third spend more than four hours a day online, mainly on their smartphones, according to the South Africa-based Ichikowitz Family Foundation, which commissioned the study.

But there’s growing unease about the darker side of social media in electioneering on the continent. Critics such as Stanford University’s Internet Observatory and Cyber Policy Center worry that online platforms have become yet another instrument for governments to tighten their grip—joining such traditional methods as controlling the content on state-run broadcasters and limiting the freedom of expression with draconian laws.

While laws are in place in most African countries to restrict political advertising on traditional media, there isn’t enough accountability for platforms such as Facebook, Kenyan activist Nanjala Nyabola argues in her book Digital Democracy, Analogue Politics.

“This assumption that developing countries are blank slates onto which technological fantasies can be projected is really dangerous,” Nyabola told the Centre for International Governance Innovation last year. “What we’re seeing is the consequences are usually far more grave than they are in countries that have robust legal and political frameworks.”

A survey in Ghana last year found the use of social media was increasing the cost of already hugely expensive campaigns and strengthening the position of wealthy politicians, whose social media machines drown out the voices of smaller parties, according to researchers of the University of Exeter in the U.K.

In Guinea, dozens of patriotic-sounding Facebook pages say President Alpha Conde is a savior and his main opponent wants to destabilize the country. (That’s a frightening thought for citizens who recall the most recent military coup, in 2008.) Paid workers regularly post on pages promoting Conde’s ruling party, including Alpha Conde TV, and one called “Guineans Open Your Eyes,” which targets Conde’s rival and carries a picture of a bloody clown on its banner.

But an analysis of the pages by Stanford shows the people controlling them rarely divulge that they’re paid, and most don’t use their real identities so viewers can know where the information is coming from.

Tech companies’ higher standards for the U.S. vote aren’t a panacea across the ocean. “Because Facebook is an American company, largely run by Americans, it is able to rely on institutional knowledge of American politics and its dynamics” to figure where misinformation enters the process in the U.S., says Arthur Goldstuck, managing director at African technology research company World Wide Worx. “It does not have the same depth of knowledge or understanding of most other countries.”

In the case of Guinea, most Facebook pages promoting Conde, the 82-year-old president, who’s seeking a third term, appear to lack transparency, according to Stanford. In a report last month, researchers said they found 94 pages that are “clearly” tied to the ruling party but fail to disclose that their operators are being paid to post text and images.

Many of the administrators hide their identities, using names such as “Continuity, Continuity” or “Alpha the Democrat.” The pages have a combined following of some 800,000 people, equal to about a third of the country’s 2.4 million internet users.

The Guinean network of pro-government pages pushes up against the boundaries of acceptable behavior on Facebook, says Shelby Grossman, a research scholar at the Stanford Internet Observatory. “If you are being paid by political candidates to post media that supports those candidates, you should be transparent of who you are and who you are affiliated with,” she says.

According to one of its spokesmen, Alhousseiny Makanera Kake, Guinea’s ruling party has established a dedicated social media team that’s active on various platforms, not just Facebook. The spokesman for that team, however, has not responded to phone calls. Messages to six pro-government Facebook pages have also been met with no response.

Facebook says the pro-government pages do not violate its standards. A company investigation showed that the pages are operated by real people with real identities, a company spokeswoman said by email. The company is working on tools that enable people to better understand the pages they follow and who’s behind them. In the U.S., the platform has introduced a tab called “Organizations That Manage This Page” to help avoid a “misleading experience,” and the company may bring the tab to more countries, she said.

That isn’t enough to help users in a country such as Guinea, where web literacy is in its infancy. Political propaganda has become completely “normalized” as parties across Africa have grown more sophisticated in their use of social media, says Thomas Molony, co-author of the book Social Media and Politics in Africa. “It’s when the pernicious content gets in, and the line between verified news and fake news is crossed, that we should be concerned,” Molony says.

Like Guinea, social media campaigning in other African countries comes with huge problems of accountability. The ruling party in Ghana, which will hold elections on Dec. 7, already had a social media army of some 700 workers by mid-2019, prompting the main opposition party to catch up and recruit its own “communicators,” as the University of Exeter study called them. All the main parties in Ivory Coast have deployed teams to campaign on social media for a contentious Oct. 31 vote.

The East African nation of Tanzania, which will hold a presidential vote on Oct. 28, has taken the opposite course, having pushed through legislation in 2018 and 2020 that criminalizes some social media posts by journalists and suppresses the growth of online media, including radio and TV.

Internet-powered politics is overwhelming underfunded grassroots political activists. “For us, this is completely unorthodox and hasn’t happened before,” says Sekou Koundouno, head of the Guinea branch of Balai Citoyen—or Citizen’s Broom—a civil society group active in several countries. “It’s not regulated at all, and you see people taking money from the state to try and keep the ruling party in power.”

Updated: 8-2-2021

In Defense of ‘Misinformation’

America has tried before to police the public debate, and the results were ugly.

I’m no fan of the current war on “misinformation” — if anything, I’m a conscientious objector — and one of the reasons is the term’s pedigree. Although the Grammar Curmudgeon in me freely admits that the word is a perfectly fine one, the effort by public and private sector alike to hunt down misinformers to keep them from misinforming the public represents a return to the bad old days that once upon a time liberalism sensibly opposed.

First, as to the word itself.

The Oxford English Dictionary traces “misinformation” in its current sense to the late 16th century. In 1786, while serving as ambassador to France, Thomas Jefferson used the word to deride the claim that the U.S. Congress had at one point sat in Hartford, Conn.

In 1817, as every first-year law student knows, the U.S. Supreme Court used the word as part of a shaky effort to define fraud. In the runup to the Civil War, supporters of the newly formed Republican Party denounced as misinformation the notion that they harbored “hostile aims against the South.”

Depending on context, the word can even take on a haughty drawing-room quality. Sir Hugo Latymer, the protagonist of Noel Coward’s tragic farce “A Song at Twilight,” discovers that his ex-lover Carlotta believes that she has the legal right to publish his letters to Hugo’s ex-lover Perry. Says the haughty Hugo: “I fear you have been misinformed.” (Writers have been imitating the line ever since.)

True, according to the always excellent Quote Investigator, a popular Mark Twainism about how reading the news makes you misinformed is apocryphal. QI does remind us, however, that there’s a long history of writers and politicians using the term as one of denunciation.

Which leads us to the pedigree problem.

Chances are you’ve never heard of the old Federated Press. 1 It was founded in the 1918 as a left-leaning competitor to the Associated Press, and died 30 years later, deserted by hundreds of clients after being declared by the U.S. Congress a source of “misinformation.”

Translation: The Congress didn’t like its point of view.

But the Federated Press was hardly alone. For the Red-hunters of the McCarthy Era, “misinformation” became a common term of derision. As early as 1945, the right-leaning syndicated columnist Paul Mallon complained that “the left wing” was “glibly” spreading “misinformation about American foreign policy” — and, worse, that others “were being gradually influenced by their thinking.”

In a 1953 U.S. Senate hearing on “Communist Infiltration of the Army” — yes, that’s what the hearing was called — Soviet defector Igor Bogolepov (popular among the McCarthyites) assured the eager committee members that a pamphlet about Siberia distributed by the Army contained “a lot of deliberate misinformation which serves the interest of the Communist cause.”

A report issued by the Senate Judiciary Committee three years later begins: “The average American is unaware of the amount of misinformation about the Communist Party, USA, which appears in the public press, in books and in the utterances of public speakers.”

Later on, the report provides a list of groups that exist “for the purpose of promulgating Communist ideas and misinformation into the bloodstream of public opinion.” Second on the list is the (by then dying) Federated Press.

In 1957, the chief counsel of a Senate subcommittee assured the members that “misinformation” distributed by “some of our State Department officials” had “proved to be helpful to the Communist cause and detrimental to the cause of the United States.”

The habit lingered into the 1960s, when — lest we forget — President John F. Kennedy and his New Frontiersman were adamant about the need to combat the Communist threat. “International communism is expending great efforts to spread misinformation about the United States among ill-informed peoples around the world,” warned the Los Angeles Times in a 1961 editorial. The following year, Attorney General Robert Kennedy gave a major address in which he argued that America’s ideological setbacks abroad were the result of — you guessed it — Communist “misinformation.”

I’m not suggesting that “misinformation” is always an unhelpful word. My point is that for anyone who takes history seriously, the sight of powerful politicians and business leaders joining in a campaign to chase misinformation from public debate conjures vicious images of ideological overreaching that devastated lives and livelihoods.

I’ve written in this space before about the federal government’s deliberate destruction of the career of my great-uncle Alphaeus Hunton, based largely on his role as a trustee for the Civil Rights Congress, a group labeled by the Senate as — you guessed it — a purveyor of “misinformation.”

So forgive me if, in this burgeoning war on misinformation, I remain a resister. America has been down this road before, and the results were ugly. I’m old-fashioned enough to believe that your freedom to shout what I consider false is the best protection for my freedom to shout what I consider true.

I won’t deny a certain pleasurable frisson as the right cowers before what was once its own weapon of choice. And I quite recognize that falsehoods, if widely believed, can lead to bad outcomes. Nevertheless, I’m terrified at the notion that the left would want to return to an era when those in power are applauded for deciding which views constitute misinformation.

So if the alternatives are a boisterous, unruly public debate, where people sometimes believe falsehoods, and a well-ordered public debate where the ability to make one’s point is effectively subject to the whims of officially assigned truth-sayers, the choice is easy: I’ll take the unruly boister every time.

The old Federated Press has no relation to the current organization using the same name.

Updated: 8-30-2021

Misinformation Is Bigger Than Facebook, But Let’s Start There

Social networks’ addictive algorithms continue to provide safe harbor for anti-vaxxers. They need to change.

As the pandemic wears on, social media isn’t getting much healthier. A succession of dodgy cures, unsubstantiated theories, and direct anti-vaccination lies continues to spread in Facebook groups, YouTube videos, Instagram comments, TikTok hashtags, and tweets. Multiple members of Congress were suspended from Twitter or YouTube for peddling misinformation around the time President Joe Biden spoke out against social media platforms’ penchant for spreading false information.

“They’re killing people,” Biden said last month, answering a reporter’s question about the role of “platforms like Facebook” in the spread of Covid-related misinformation. In response, Facebook cited a study it conducted with researchers at Carnegie Mellon University that found increases in “vaccine acceptance” among its users over the course of 2021.

(The company has also criticized the president for focusing on what it’s called a relative few bad actors, such as the prominent anti-vaxxer influencers the White House has dubbed the Disinformation Dozen.) Biden took a less directly confrontational tack a few days later.

Yet despite a new level of candor, the debate around anti-vaccine misinformation hasn’t advanced much since the first pandemic lockdowns. Often the issue is framed as one of moderation—that if social networks just enforced their own rules, they’d ban the biggest purveyors of falsehoods and things would be fine.

“Those community standards are there for a reason,” says Imran Ahmed, chief executive officer of the nonprofit Center for Countering Digital Hate.

The volume of moderation is also the chief metric cited by the internet companies themselves. In its response to Biden’s “killing people” comment in July, Facebook said it had removed more than 18 million examples of Covid-19 misinformation, and labeled and buried more than 167 million pieces of pandemic-related content. In an Aug. 25 blog post, YouTube said it had removed at least 1 million videos related to “dangerous coronavirus information.”

Of course, that’s not a lot for a service with billions of users. “I think anytime we’re talking about at the moderation level, we’re failing,” says Angelo Carusone, president and CEO of Media Matters for America. “Too marginal to matter.” Media Matters recently documented how Facebook users engaged more than 90 million times with a single video taken at an Indiana school board meeting questioning the effectiveness of vaccines and masks.

At the time this article was published, several copies of the video Carusone’s team tracked were accessible on both Facebook and YouTube. And yes, they’re far from the only such videos on each service.

While reducing the overall supply of misinformation on social networks has value, it’s more important that the sites stop artificially stoking demand. That means drastically overhauling their highly effective recommendation engines to punish purveyors of misinformation for lying, instead of rewarding them for their skill at getting and holding viewers’ attention.

Too late, this is becoming received wisdom among governments as well as watchdogs. “The rapid spread of misinformation online is potentially fuelled by the algorithms that underpin social media platforms,” the U.K.’s Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology said in a post on its website. The European Union is weighing proposals that would require social media companies to disclose more about how these algorithms work.

The big platforms again say they embrace algorithmically limiting the reach of bad information, but the learning curve has been steep. Anti-vaxxers are just one of several fringe communities on the internet that have become more than adept at playing whack-a-mole. NBC News recently reported how a selection of anti-vaxxer groups on Facebook had avoided the ax by renaming themselves “Dance Parties.”

To catch up, let alone keep up, social platforms would need to invest significantly in applying lessons from smart, ground-level moderators, information theorists, cryptographers, and former employees who’ve spoken up about the companies’ failures in this area.

U.S. Senators Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) and Ben Ray Luján (D-N.M.) have introduced a bill that would suspend Section 230—the long-standing legal shield for websites that host other people’s conversations—for social networks found to be boosting anti-vaxxer conspiracies. “For far too long, online platforms have not done enough to protect the health of Americans,” Klobuchar said in a statement. “This legislation will hold online platforms accountable for the spread of health-related misinformation.”

Advocates of these reforms tend to get less comfortable when it comes to conservative outlets that more closely resemble the traditional free press, such as Fox News and talk radio. Clips from these sources questioning or denying the utility of Covid vaccines continue to find wide audiences on social networks.

Still, it’s always wise to avoid giving governments broad power to censor the press, says Philip Mai, co-director of the Social Media Lab at Ryerson University in Toronto. “If you look at any misinformation laws that have been passed in the last four years, eventually they are used by the party in power to keep themselves in power and to lock up dissidents,” he says.

Reducing incentives to promote vaccine skepticism, Mai says, means following the money beyond social networks. “For many of these people, it’s a grift,” he says. “They don’t care what they’re selling as long as the paycheck is rolling in.” E-commerce sites could be a good place to start.

Bloomberg Businessweek easily found anti-vaxxer products such as books, shirts, and even masks on Amazon.com, Etsy, and a handful of crowdfunding sites. Apple Inc. removed Unjected, a dating app for anti-vaxxers, from its App Store last month, but the app remains on the Android equivalent, Google Play, where its banner image promotes unsubstantiated claims about Covid vaccines.

No one of these strategies is a panacea, especially at this point. They all need to be tried in combination, in good faith, and in earnest. Before the holiday season and winter return, likely bringing another surge of both Covid cases and the inevitable wave of misinformation that now comes alongside them, we still have a chance to change the story—to make our social networks healthier, and ourselves along with them.

Related Articles:

Online Ad Fraud Costs Advertisers $5.8 Billion Annually (#GotBitcoin?)

Ad Agency CEO Calls On Marketers To Take Collective Stand Against Facebook (#GotBitcoin?)

Advertisers Allege Facebook Failed to Disclose Key Metric Error For More Than A Year (#GotBitcoin?)

Fake Comments Are Plaguing Government Agency Websites And Nobody Much Seems To Care (#GotBitcoin?)

New York Attorney General’s Probe Into Fake FCC Comments Deepens (#GotBitcoin?)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.