I Downloaded My DNA This Week (#GotBitcoin)

I Downloaded My DNA This Week

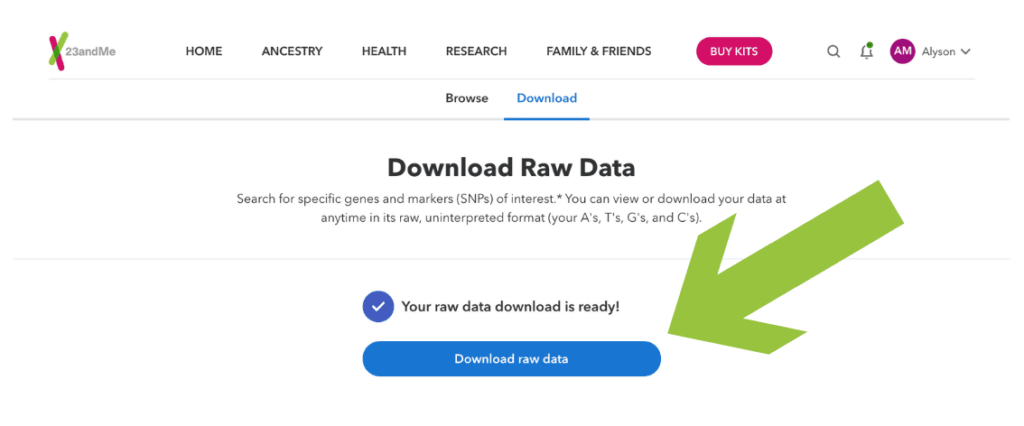

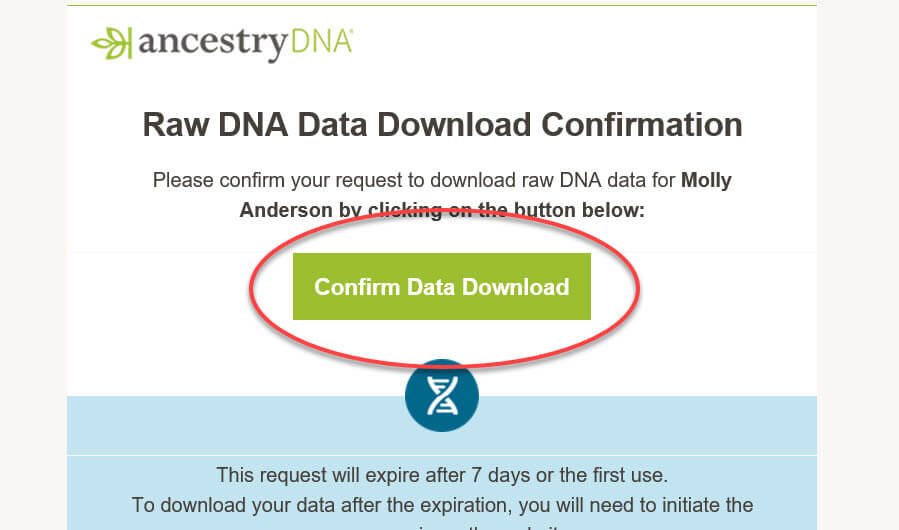

I took a test a couple years ago as part of a sales pitch for the company I was working at, and recently learned that I could download all the raw data. So I did. I Downloaded My DNA This Week

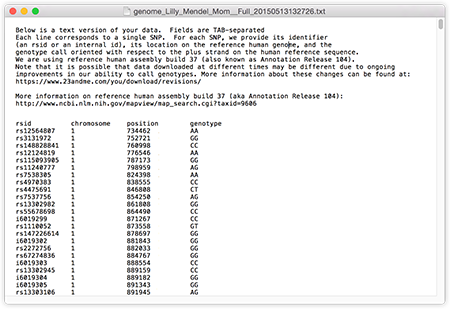

There’s something surreal about looking at your genetic code itself. When you see even just a part of your genome written out, inside your text editor on your computer, it looks… like software. If you’ve ever seen or worked with code like assembly language, it looks just like that.

And that’s when you realize… we are code. We are programs.. Our bodies, our hardware, are remarkable computers that run incredibly complex code to build and maintain themselves. Our minds, our software, are equally complex, more complex than any computer we’ve invented yet (though quantum computing may change that in the years to come).

Which also means… we can improve. Just as any hardware can be upgraded and any software can be patched, so can we adapt and improve. Today, it’s easiest to improve our minds, but with technologies like CRISPR gene editing, patching and upgrading our hardware programs is no longer science fiction.

What does this all mean for us? It means that we are limitless in our potential, and it equally means that we have no excuses for not improving ourselves. Our very corporeal existence is defined by code, written into every cell in our bodies, and code is meant to be patched, upgraded, and improved.

Take heart, then, when faced with a new subject, topic, or idea to learn. Instead of lamenting it or wishing it were easier, revel in the fact that you are meant to be constantly improving and upgrading yourself. Take joy that you can, that the opportunity exists for you to advance yourself, and seize that advantage with all your might. You are a learning machine at every level.

Updated: 5-20-2022

It’s Too Late To Protect Your Genetic Privacy. The Math Explaining Why.

‘CentiMorgans’ measure how much DNA we share with others, often unlocking long-unsolved mysteries.

Earlier this year, the police in Eugene, Ore., said they had identified a serial killer who committed three murders from 1986 to 1988. The man, John Charles Bolsinger, had escaped attention so thoroughly for three decades because he had killed himself in 1988.

Investigators had stored DNA from the crimes, and recently plugged it into a genealogy database, zeroing in on Bolsinger by first finding his distant cousins. It is the latest in a growing string of cold cases solved by law enforcement using techniques developed by genealogy hobbyists.

Take a DNA sample, identify a second cousin here, a third cousin there, and then use public records to reconstruct a killer’s family tree.

If you’re concerned about the privacy implications of this, you might think, “Well, I would never submit my DNA to one of those sites.”

Sounds reasonable? In fact, it is far too late to completely protect your genetic privacy via personal abstention. A brief exploration into the mathematics of genetics explains why it has become possible to track down killers—but also anyone—through distant relatives.

“If somebody wanted to use the skills of forensic genealogists to try to track you down through a third cousin, they could,” said Jennifer King, a privacy scholar at Stanford University.

To understand how exposed your genes potentially are, consider an obscure unit of measurement—the centiMorgan, or cM. (It is named for Thomas Hunt Morgan, whose experiments on fruit flies led to the Nobel Prize in 1933 for showing how chromosomes are inherited.)

It lies at the heart of all the stories you read nowadays of people discovering unknown links through their DNA and genealogical research.

It gauges genetic distance, specifically the length of identical segments of DNA that two people share due to descent from a common ancestor.

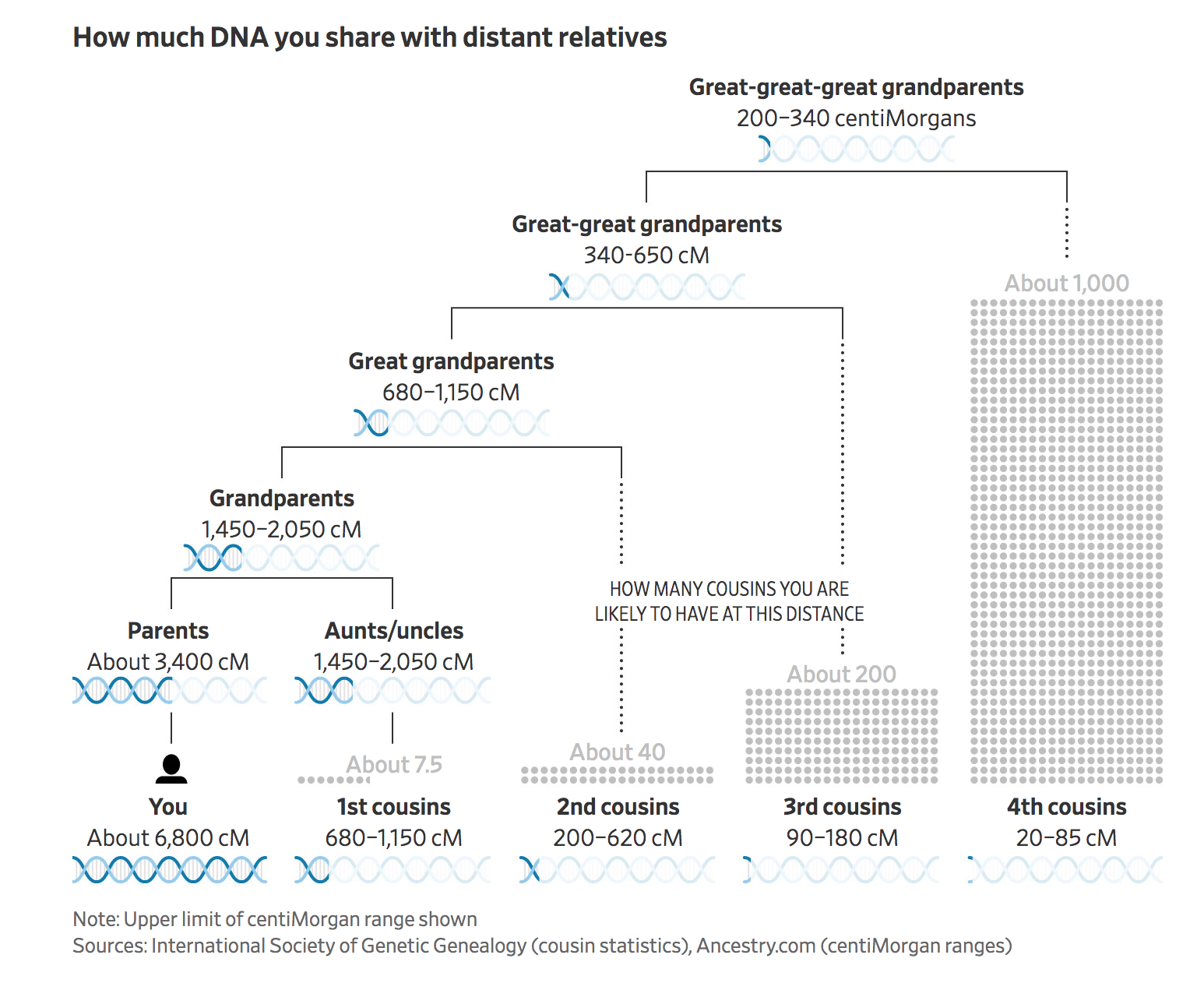

In general, people have about 6,800 cMs. A child inherits half their DNA—one set of chromosomes—from each biological parent. So child and parent will have around 3,400 cMs of DNA that match.

(Because of slightly different methodologies, the major testing companies report slightly different numbers.)

For every “degree of relatedness,” the length of shared cMs halves. An uncle or grandparent, one degree removed from parents, shares half as much DNA on average.

That is 25%, or about 1,700 cMs. One more degree removed: A first cousin or great-grandparent shares half again, or around 850 cMs. And so on.

Even with all these halvings, very distant relatives out to fifth cousins share so much identical DNA that a common ancestor is the only possible source.

“I think most Americans don’t realize this,” said Libby Copeland, author of “The Lost Family: How DNA Testing Is Upending Who We Are.” “It’s a profound shift.”

It is easy to find distant relatives, because a typical individual has so many: according to various methods, around 200 third cousins, upward of 1,000 fourth cousins and anywhere from 5,000 to 15,000 fifth cousins.

This isn’t just relevant for crime scenes. There is no such thing anymore as truly anonymous sperm or egg donors, unknown fathers, or closed adoptions. They are all examples of scenarios where secrets involving parentage are easily solved by the centiMorgans. No court ruling or confidentiality agreement can erase this science.

An adopted child who doesn’t know his biological parent still shares 3,400 cMs with that person, and hundreds of centiMorgans with numerous cousins from that parent’s family.

The child, or generations from now that child’s descendants, could upload their DNA to a database and by looking for matches with others who have uploaded theirs, discover some of those distant cousins.

That would be enough to reconstruct his family tree and identify the parent, even though the parent never uploaded their DNA—the exact same process used to identify DNA in cold cases.

‘If somebody wanted to use the skills of forensic genealogists to try to track you down through a third cousin, they could.’

— Jennifer King, a privacy scholar at Stanford University

Katie Hasson, associate director of the Center for Genetics and Society, which advocates for protections against genetic information being abused, says that only collective action—not individual precaution—can address the privacy concerns this creates.

“Right now, forensic genealogy is very labor intensive and new, and being used for very serious crimes and cold cases,” said Ms. Hasson. “The likelihood it will be confined to that, without actual enforceable restrictions and regulations, is slim.”

The scale of testing is enormous: around 21 million samples on AncestryDNA, 12 million at 23andMe, 5.6 million at MyHeritage and 1.7 million at FamilyTreeDNA, according to data from the International Society of Genetic Genealogy.

Legal protection is limited. The 2008 Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act, bars genetic information being used for decisions about health insurance and employment.

But it never anticipated the extent of today’s testing, the types of cutting-edge medical research under way, or what happens, say, if a company with a giant genetic database collapsed. What happens if the data of millions of people (with cMs matching thousands of distant cousins each) is sold at bankruptcy auction?

In my own extended family, I corresponded with a distant cousin who discovered one great-great-grandfather in her family tree wasn’t biologically related.

By identifying distant cousins with whom she shared DNA, she found that she and these new cousins were all descended from a different man: a soldier who spent a month in the same county as her great-great-grandmother in 1862 during the Civil War, about nine months before a child was born. (She asked I not share names. Even 160 years later, some secrets are awkward.)

There is really only one thing that this Civil War soldier, the woman he briefly met in 1862, and Eugene, Ore.’s serial killer from the 1980s all have in common: They never submitted their DNA to a testing site. It didn’t matter. Their centiMorgans are everywhere.

Related Article:

Crispr, Eugenics And “Three Generations Of Imbeciles Is Enough.” (#GotBitcoin?)

Why It’s So Hard To Find Dumbbells In The US

History of Alchemy From Ancient Egypt To Modern Times

Gyms Reopening May Not Facilitate Coronavirus Infections, Study Finds

These Are Your Rights When A Barber, Gym Owner Or President Trump Asks You To Sign A COVID-19 Waiver

As Coronavirus Lockdowns Lift, How Ready Are Gyms To Reopen?

Leery of Joining A Health Club? Today’s Gyms Are Good For Physical, And Fiscal, Fitness

Does Getting Stoned Help You Get Toned? Gym Rats Embrace Marijuana

Spy Gadgets For Grow Facilities / Weed Dispensaries (#GotBitcoin?)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.