U.S. Cities Look To Shed Ratings While Taking On More Debt

U.S. cities and counties are using fewer ratings to assess the risks of the bonds they sell, providing investors with just one opinion on an increasing amount of new debt. U.S. Cities Look To Shed Ratings While Taking On More Debt (#GotBitcoin?)

One-fourth of municipal borrowing is given a single grade, leaving smaller investors with less information.

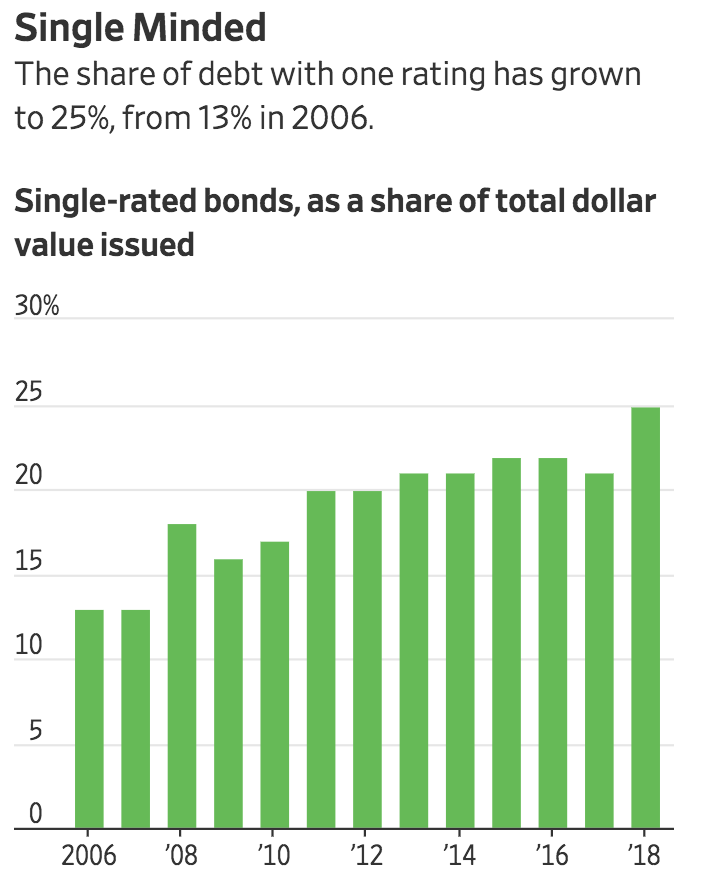

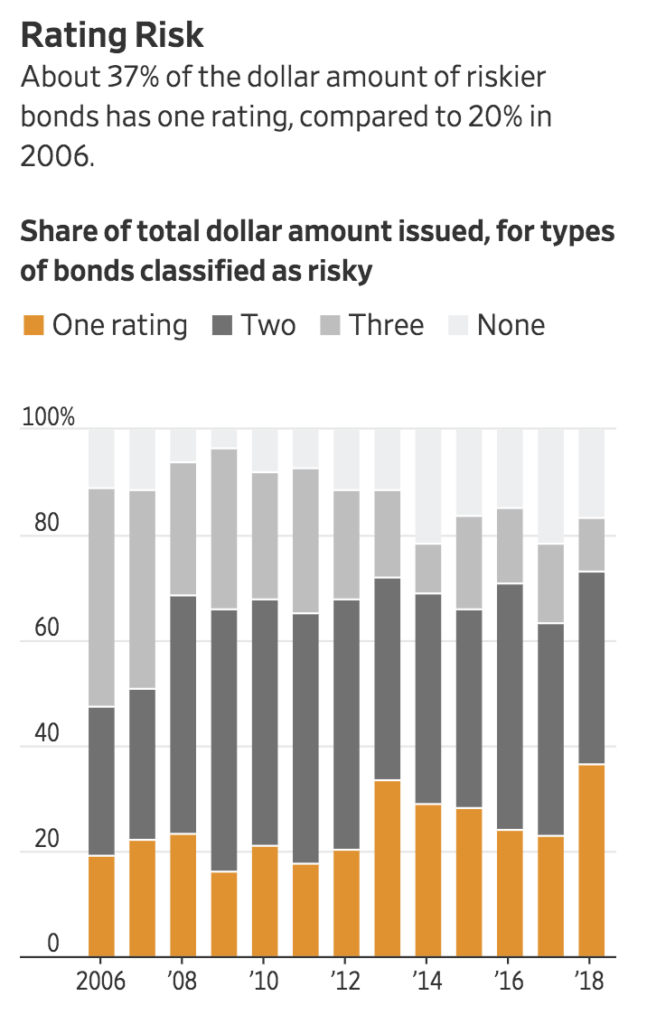

Roughly 25% of the dollar value of all municipal debt issued this year carried a single grade from one of the major ratings firms, according to Municipal Market Analytics data as of Oct. 3. If that percentage holds through the end of the year, it would be the highest since the research firm began tracking the data in 2006. For the riskiest debt, the single-grade ratio by dollar volume was 37%.

Municipal officials and advisers said fewer ratings help cities trim expenses and save time when they borrow money for everything from school construction to sewer repairs. Bond issuers typically pay rating firms to issue a report. But some analysts said opting for one grade from a single firm puts smaller investors at a disadvantage as less information circulates through the $3.8 trillion municipal market.

“Mom-and-pop investors and small asset managers without their own research staff are at a disadvantage,” said Matt Fabian, a partner with Municipal Market Analytics.

Scores attached to municipal debt are important in the public finance world because investors rely on these opinions to help make decisions about buying or selling bonds that governments use largely to pay for new construction projects. The grades range from gold-plated triple-A to several levels of “junk.”

The largest graders are S&P Global Inc., Moody’s Corp. and Fitch Ratings, which together are responsible for 96% of all global bond ratings among firms registered with U.S. regulators. Some municipalities are required by statute to get grades of a certain quality from at least one ratings firm before borrowing.

The cities and counties that did rely on one rating this year gravitated to a particular grader more than others: S&P Global. Nearly 65% of the deals with one rating were evaluated by S&P, compared with 34% for Moody’s and 1% for Fitch, according to the Municipal Market Analytics data.

One of these borrowers that turned to S&P was Hoboken, N.J., which issued bonds in February to make park and road improvements. Hoboken finance director Linda Landolfi decided after conferring with the city’s financial adviser that Hoboken needed only an S&P rating for roughly $70 million in debt.

The reason: She was pleased with S&P’s double-A-plus grade and saw little need to get a second opinion.

“We don’t see that we’ll get a better rating from anybody else,” Ms. Landolfi said, adding that another ratings firm wouldn’t have “given us a worse rating,” either.

It is common for the major ratings firms to disagree about the fiscal health of cities they are asked to grade. One particular point of difference: pension liabilities.

Cities and counties across the U.S. don’t have enough assets on hand to pay for all future obligations to their workers, but how deep this deficit looks depends on what those cities expect to earn on their investments. Moody’s and Fitch impose their own calculations of pension liabilities while S&P relies more on government-provided projections.

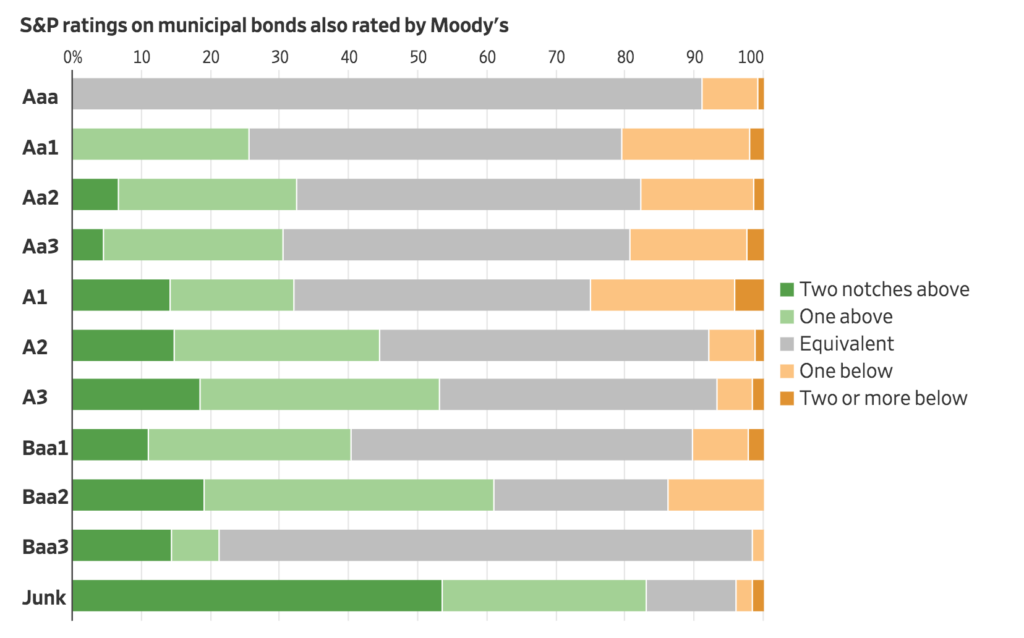

The most noticeable divergence between the firms in 2018 occurred on the riskiest borrowings. Debt that Moody’s considers junk got an S&P rating at least one notch higher than the Moody’s grade 83% of the time, according to Municipal Market Analytics data of deals where both firms offered grades. There was more agreement between those two firms on safer issuances, according to the data.

A spokesman for S&P said the firm looks at many factors when evaluating how pension problems affect the riskiness of government debt. Cities can be penalized for making insufficient annual pension contributions, using unrealistic mortality rates or using investment-return projections S&P considers overly optimistic, the spokesman said.

“We don’t simply take these numbers at face value,” the firm said in a statement.

One place affected by these varying grading approaches is Calhoun County, in southern Michigan.

Moody’s in March said its calculation of the county’s pension liabilities was $86 million, more than twice the figure released by the government. But when the county asked S&P to grade a new offering of $8 million last month, S&P relied on the government’s numbers to estimate how much the county has on hand to cover pension promises.

S&P awarded the bonds a double-A grade, one notch higher than the grade Moody’s provided in its unsolicited review earlier in the year.

One financial adviser to the county said S&P was hired partly because that firm’s ratings were historically more positive for municipalities across the state. The proceeds will be used to shore up the county’s pension plan.

“S&P is more favorable to Michigan credits than Moody’s has been in the past,” said Bobby Bendzinski, president of Bendzinski & Co., the county’s financial adviser.

A spokesman for S&P said that “the U.S. municipal bond market benefits from a diversity of opinions on credit risks.”

Calhoun County Controller Kelli Scott said going with only S&P allowed the county to save costs associated with paying another rater. S&P, she said, could also rely on its past conversations with the county.

“We don’t have to start from scratch and tell the story every single time,” she said.

Updated: 12-6-2019

Muni-Bond Ratings Are All Over the Place. Here’s Why

Amid fight for market share, ratings companies struggle to judge creditworthiness of financially troubled cities.

Chicago is in bad financial shape, with an unsustainable pension burden and a towering debt load. Yet the city will shortly issue bonds that are likely to be rated as supersafe, even though similar investments have lost money.

Bond-ratings firms are struggling to judge the creditworthiness of cities and local governments with deep financial problems. There have been widely disparate ratings, errors in analysis and a fight for market share that may have produced optimistic outlooks.

Chicago has the most pension debt of any major U.S. city, according to Merritt Research Services, and a shrinking population. To help cover an $838 million budget shortfall, the city is planning to sell up to $1.5 billion in bonds beginning as soon as this month.

One goal of the bond sale is to lower the city’s interest costs. To do that, Chicago is pledging its sales-tax revenue to fund the bonds, which is supposed to make them safer than the city’s conventional bonds. The strategy worked in 2017, when Chicago issued a similar sales-tax bond and credit-ratings firms deemed it nearly riskless.

That may be an overly optimistic assessment. Puerto Rico issued similar bonds, but when it went bust, the bonds lost money. Chicago’s chief financial officer and some raters said the bonds are safer than Puerto Rico’s because of additional protections granted to investors. But investors don’t agree and have treated Chicago’s existing sales-tax bonds as if they were rated junk, according to recent data from Refinitiv’s Municipal Market Data.

“We’re making that mistake again right now,” said Nicholos Venditti, a portfolio manager at Thornburg Investment Management, which oversees $10 billion in munis. He added, “There is a risk here that is not being accounted for by the ratings agencies.”

Chicago’s coming sales-tax bonds have already been rated AA-minus by S&P Global Inc., the same high rating it gave to the earlier bonds. Smaller ratings companies Fitch Ratings and Kroll Bond Rating Agency Inc. haven’t rated the new issue yet, but have maintained their triple-A ratings on the earlier bonds.

“We don’t think they’re triple-A,” said Bill Delahunty, director of municipal research at money manager Eaton Vance, which oversees $52 billion in munis, including some Chicago debt. “If the city of Chicago goes down and these are tied to the city of Chicago, we think those bonds will experience volatility.”

Karen Daly, a senior managing director at Kroll, said Illinois state law ensures additional protections for bondholders compared with the Puerto Rico securities. “It is bulletproof, in our opinion,” she said. S&P said in a Nov. 26 report that separating sales-tax revenues gives bondholders extra security. Amy Laskey, a managing director at Fitch, said she considers Chicago’s sales-tax bonds to be safer than Puerto Rico’s because of how they are legally structured.

Chicago’s chief financial officer, Jennie Huang Bennett, also disagreed with the comparison. “There are true legal protections that are provided to investors,” she said.

Moody’s Corp. , another major ratings firm, is unlikely to rate Chicago’s new bonds. The firm downgraded $9 billion of the city’s bonds to junk in 2015. It hasn’t been hired to rate a bond issue there since.

Ms. Bennett said she hasn’t focused on Moody’s ratings. “We really haven’t spent a lot of time on it,” Ms. Bennett said. “We have currently just taken the conversations with Fitch, S&P and Kroll.”

Municipal bonds are popular among individual investors for their safety and tax-advantaged status. Investors have poured a record amount of cash into municipal bonds this year as they seek out steady income and adapt to new tax rules.

But the market has grown more risky since the financial crisis as pension obligations soared and cash-strapped borrowers like Detroit and Puerto Rico declared bankruptcy. A recent court ruling related to Puerto Rico’s restructuring undercut assumptions about how muni bonds would fare in bankruptcy. “Our confidence in that is a little bit shaken,” said Fitch’s Ms. Laskey.

Fitch has said it is re-evaluating ratings on a handful of bonds, including its triple-A rating on Chicago’s sales-tax debt.

“The rating agencies have come out more frequently over the past couple of years with the headline: ‘We’re changing our methodology,’ ” said Robert Amodeo, head of municipals at Western Asset Management, which oversees $20 billion in munis. “To their defense, there’s little—if any—precedent set for them to rate those situations.”

In the past, it was easier to judge the creditworthiness of bonds because state and local governments were financially healthier and more than half were insured, removing the risk of individual issuers running into trouble. Last year, only about 7% of muni bonds were insured, according to insurers’ financial disclosures and issuance data.

Bond ratings are supposed to judge the likelihood of default. For munis, default rates have remained low, especially compared with corporate bonds. But some muni deals have soured more quickly than in the past.

The firms are adjusting their ratings. S&P, for example, overhauled a rating methodology it had used since 2007, causing it to change ratings on more than 950 bonds through October. These changes led to downgrades of as much as seven rungs in the ratings scale, pushing safe investment-grade bonds into risky junk-bond territory. There have also been upgrades of as much as three notches.

S&P also admitted to errors in rating municipal debt. Last year, S&P withdrew or changed dozens of ratings in New York, Virginia and Indiana after the firm said it had misapplied one of its ratings methodologies for about eight years. Months later, the Securities and Exchange Commission cited similar bonds when it anonymously singled out a “larger” credit-rating firm in a report that said the firm needed to “enhance its internal control structure to ensure adherence to its rating methodologies.” Spokespeople for the SEC and S&P declined to comment.

Bond-ratings firms are also in a fight for market share in the municipal market. The entities that sell bonds pick the firms that will rate them, a longstanding conflict in the industry that creates an incentive for the firms to issue rosy ratings.

S&P tends to issue higher ratings on riskier bonds than its biggest competitor, Moody’s. When both firms rate a bond and Moody’s calls it junk, S&P’s rating is higher 80% of the time, according to data from research firm Municipal Market Analytics as of June. For debt considered investment-grade by Moody’s, far outnumbering junk bonds, the two firms’ ratings are closer. S&P is the top choice for municipalities hiring just one rating firm, according to MMA.

Spokesmen for S&P and Moody’s said their ratings have been strong indicators of default risk.

The ratings business has also been roiled by newcomers such as Kroll, which often rates debt higher than its competitors and has almost a 10% market share of municipal debt outstanding, according to MMA data.

Kroll rates bonds also rated by Moody’s, S&P or Fitch higher roughly 60% to 80% of the time, according to a Journal analysis of data on thousands of bonds issued over the past decade from Fitch, Kroll and data provider IMTC.

“They’re kind of being used when they can give a higher rating than Moody’s and S&P. That’s typically the expectation,” said Dan Solender, a portfolio manager at Lord Abbett, which oversees $26 billion in munis.

A spokeswoman for Kroll said the firm stands by its ratings. She said the data doesn’t reflect ratings that Kroll produces that aren’t chosen to be published by the municipalities. As a result, the “analysis fails to capture the reality of the market.” Kroll’s Ms. Daly added that her firm doesn’t rely on a formula for ratings. “It’s pure intellectual sweat and research,” she said. U.S. Cities Look To,U.S. Cities Look To,U.S. Cities Look To,U.S. Cities Look To,U.S. Cities Look To,U.S. Cities Look To,U.S. Cities Look To,U.S. Cities Look To

Related Articles:

The Pension Hole for U.S. Cities and States Is the Size of Japan’s Economy (#GotBitcoin?)

Would Someone Please Buy US Treasury Bonds? (#GotBitcoin?)

Prosecuting Bankers Proves Exercise In Frustration (#GotBitcoin?)

Probes Reveal Central, US-Based, International Banks All Have Sticky Fingers (#GotBitcoin?)

Major Banks Suspected Of Collusion In Bond-Rigging Probe (#GotBitcoin?)

Some Merrill Brokers Say Pay Plan Urges More Customer Debt (#GotBitcoin?)

Deutsche Bank Handled $150 Billion of Potentially Suspicious Flows Tied To Danske (#GotBitcoin?)

Wall Street Fines Rose in 2018, Boosted By Foreign Bribery Cases (#GotBitcoin?)

U.S. Market-Manipulation Cases Reach Record (#GotBitcoin?)

Poll: We Should Get Rid of The Federal Reserve And Central Banks Because:

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.