The World’s Rivers, Canals And Reservoirs Are Turning To Dust

Harvard Quietly Amasses California Vineyards—And The Water Underneath. Making a bet on climate change, university’s $39 billion endowment has been snapping up farmland and the related water rights. The World’s Rivers, Canals And Reservoirs Are Turning To Dust

Steve Sinton, a rancher, was baffled when a company he’d never heard of began buying large tracts of agricultural land near his pastures at above-market prices. The firm, Brodiaea Inc., over a few months in 2012 acquired more than three square miles of a flat-bottomed valley.

“It was surprising, the prices they were willing to pay,” says Mr. Sinton, a partner in a family-owned ranch that raises cattle and grows grapes. A conventional agricultural business’s returns couldn’t have justified those prices. “It didn’t make sense to me.”

Brodiaea’s drilling permits and property purchases were signed by Matt Turrentine, a local who had recently left his family’s grape-brokerage business. He wouldn’t say who was behind the investment, Mr. Sinton and other locals say. The firm bought more acreage, drilled deep-water wells and began planting vineyards capable of producing billions of grapes annually.

One thing was clear. Brodiaea was willing to pay a premium for land that had good access to groundwater, an increasingly valuable resource given that aquifer levels elsewhere in San Luis Obispo County had fallen steeply. “We didn’t know who Brodiaea was,” says Sue Luft, a retired environmental engineer who lived nearby, “but we knew it was big money.”

They got the answer in 2014, in a real-estate newsletter article about the buyer. It was Harvard.

The university’s endowment manager, Harvard Management Co., was stealthily building a sizable grape-growing business on the Central Coast through entities including Brodiaea. With the land, it was acquiring rights to vast sources of water in a region where the earth’s warming is making the resource an ever-more-valuable asset.

Drought has plagued California in recent years, hitting farmers particularly hard. The Central Coast experienced drought conditions for 30% of the past two decades, compared with 14% of the prior 100 years, a 2015 study found. Droughts have led to spikes in withdrawals from aquifers, many of which aren’t recharging as much during rainy season, says study co-author Noah Diffenbaugh, a Stanford University professor.

Harvard’s bet has proven prescient. The $39 billion fund, among America’s biggest endowments, now values its vineyards at $305 million, up nearly threefold from in 2013, while its overall natural-resources investments have done poorly.

The wager has also earned backlash from some farmers and other locals who fear Harvard eventually will use up groundwater and unduly influence water-use regulations. “Should they be controlling our groundwater plans?” says Debbie Arnold, a San Luis Obispo County supervisor. “I don’t think so.”

Others, like Mr. Sinton, are less concerned, pointing out that some earlier crops were thirstier than grapes. “When I was a kid,” Mr. Sinton says, “they were growing alfalfa and sugar beets there.”

A Harvard Management spokesman says it is the endowment’s policy not to discuss individual investments. In its financial report issued in 2012, the year Brodiaea began buying, Harvard said it liked the natural-resources asset class “because we believe its physical products are going to be in increasing demand in the global economy over the coming decades.”

In a warming planet, few resources will be more affected than water, as more-frequent droughts, storms and changes in evaporation alter a flow critical for drinking, farming and industry.

Even though there aren’t many ways to make financial investments in water, investors are starting to place bets. Buying arable land with access to it is one way. In California’s Central Coast, “the best property with the best water will sell for record-breaking prices,” says JoAnn Wall, a real-estate appraiser who specializes in vineyards, “and properties without adequate water will suffer in value.”

Investors who see agriculture as a proxy for betting on water include Michael Burry, a hedge-fund investor whose wager against the U.S. housing market was chronicled in the book and movie “The Big Short.” In a 2015 New York Magazine interview, Mr. Burry was quoted as saying: “What became clear to me is that food is the way to invest in water. That is, grow food in water-rich areas and transport it for sale in water-poor areas.” Mr. Burry declined to comment.

David Gladstone, chief executive of Gladstone Land Corp. , a publicly traded farmland-investment trust, says the recent California drought was profitable for his company and tenant farmers because they had access to water while others didn’t. The changing climate has made control of water more valuable, he says. “That is certainly true in most of the U.S., but very true in California.”

In California vineyards, the water-proxy math is compelling. When grapes are harvested, about 75% of their weight is water. California’s wine is a globally coveted product, so owning vineyards effectively turns water into revenue.

“You can’t farm without water. Period,” says Madeleine Fairbairn, an assistant professor at University of California Santa Cruz who studies the phenomenon of investors buying farmland. “California land values are therefore very linked to water rights.”

Water has long been contentious in California. Los Angeles used subterfuge to acquire water rights from the Owens Valley, a deal that helped inspire the movie “Chinatown.” More recently, farm irrigation has raised concern among some environmentalists who argue that crops such as almonds use excessive water.

Climate change is making the situation worse, scientists and state officials say. The Sierra Nevada snowmelt that satiates much of the state has become harder to count on, sometimes coming earlier in the season and overwhelming the capacity of reservoirs to contain it before it goes to sea—or barely coming at all.

A year before Harvard began acquiring property, local officials began worrying about declines in the region’s groundwater basin. It was once celebrated as one of the largest freshwater aquifers west of the Mississippi River, but the level in certain wells had fallen significantly.

In early 2011, San Luis Obispo County issued a report with a map showing in deep red—a “red zone” or “red spot,” locals call it—where groundwater had fallen more than 70 feet. “We’re having more heat and more drought,” says Willy Cunha, a vineyard manager in the county. That has put a premium on land with good water, he says. “It is like California beachfront property. God isn’t making any more of it.”

There are no tourist markers or plush tasting rooms at Harvard’s vineyards, just “no trespassing” signs, rutted roads and farming equipment. Harvard Management’s agricultural operation sells grapes to winemakers.

Harvard’s foray harks back to 2012, when Mr. Turrentine and James Ontiveros, a local vineyard manager, founded an agricultural investment advisory firm named Grapevine Capital Partners LLC and pitched the idea to Harvard. Harvard signed on.

Grapevine Capital “identified an area where the groundwater is very good, and it’s outside the red zone,” says Tony Correia, an agricultural-land appraiser specializing in vineyards. Wine-industry writer Rusty Gaffney wrote in 2015 that Mr. Ontiveros had spoken to him of the land Grapevine steered Harvard toward, telling him “the region had sufficient underground water aquifers to be successfully farmed despite recent climate changes and drought conditions.”

Mr. Turrentine says he doesn’t have permission from Harvard to discuss the investments. Mr. Ontiveros didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The land Grapevine identified for Harvard was in a flat-bottomed valley south of Shandon, 190 miles northwest of Los Angeles, county records show. The groundwater in this area was much easier to tap than in other grape-growing operations that form the heart of the Paso Robles wine region, according to reports from the local groundwater agency. It was relatively close to the surface and had fallen less than 30 feet.

In addition, a giant aqueduct passed through the valley on its way to Santa Barbara. Local officials had negotiated rights to tap into it.

In June 2012, Mr. Turrentine filed paperwork to create Brodiaea—the scientific name for a type of lily—which was wholly owned by Harvard, although those filings didn’t show that. In July, Brodiaea bought its first property in the county. It generally bought unlisted properties, many of them carrot farms, local brokers say.

By autumn, Brodiaea had pieced together about 3,000 acres, county records show, and started to plant vineyards. The firm eventually became one of San Luis Obispo County’s 10 largest property owners by taxable value.

In the summer of 2013, several residential wells ran dry between Paso Robles and Shandon, roughly 10 miles west of Harvard’s vineyards. The general consensus was that the drought led vineyards to pump more well water. Residents began attending county meetings demanding action in the groundwater basin, which included Harvard’s land.

Local resident Lindsay Pera told elected officials at a county meeting in July 2013 that her home was surrounded by green vineyards and “that green is the water we are trucking, from our ground, out of the county in the form of wine.” She says she still worries about the large-scale extraction of water from the Paso Robles basin.

The county supervisors issued an emergency moratorium on new agricultural wells starting Aug. 27, 2013—not just wells in the affected areas but also in areas such as Harvard’s holdings where groundwater hadn’t fallen as much.

The day before the moratorium took effect, Harvard’s Brodiaea filed for permits to drill seven wells deeper than anything else in that part of the county—enough to fill an Olympic-size swimming pool in 90 minutes. One well hit water at 112 feet, but the driller completed the well to 1,200 feet deep, county records show.

This would allow it to keep drawing water, even if droughts dropped the groundwater level further.

About four months later, Harvard filed paperwork to create a new entity, SLO San Juan Road LLC. Messrs. Turrentine and Ontiveros’s firm, Grapevine, acted as the agent for the new entity. Through SLO, Harvard continued buying property south of Shandon. In early 2014, Brodiaea bought an 8,700-acre cattle ranch in the nearby Cuyama Valley.

Harvard’s firms continued to plant rootstock on its Shandon-area properties. Its new vines would soon carpet most of the valley.

In March 2014, the Farmland Investor Letter revealed that Harvard was backing Brodiaea. Some local residents were vocally upset, saying that Harvard and Mr. Turrentine were positioning themselves to have an outsize influence on the future of groundwater use, leaving smaller rural residents without a voice.

In early 2016, rigs hired by Brodiaea began to drill 12 water wells on its Cuyama Valley property. When they were done, workers began to plant vines there as well, pumping up aquifer water to nourish the new plants.

Cindy Steinbeck is a vineyard owner whose family had grown grapes in the area for five decades. She wrote to Harvard Management’s president in March 2016 saying its use of limited-liability companies “seems designed to obfuscate Harvard’s activities in the area.”

“Such an investment does not make economic sense,” she wrote, noting above-market prices Harvard was paying, “if your intent is simply to grow and sell grapes. It would, however, make perfect sense if the investment wasn’t for farming but rather for the brokering of water.”

A Harvard official responded that its investment was “purely agricultural in nature” and that the vineyards prioritized water conservation. She says she remains concerned.

Kat Taylor, an environmentalist and wife of hedge-fund billionaire and liberal activist Tom Steyer, resigned earlier this year from Harvard’s board of overseers in protest of the endowment’s investments in things such as fossil fuels and water holdings she says threaten the human right to water. The board helps run the university but doesn’t have direct responsibility for the management company.

“It may, in the short run, be about developing vineyard property,” she says of Harvard’s California investments. “In the long run, it was a claim on water.”

Harvard’s investing guidelines say respecting local resource rights are of increasing importance “in the coming decades as competition for scarce resources, such as arable land and water, intensifies due to increasing global population, climate change, and food consumption.” All plans Harvard has filed indicate it intends to use its water to grow grapes.

In 2014, California experienced its warmest year on record. Gov. Jerry Brown, seeking to preserve groundwater, signed sweeping legislation to prevent depletion. The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act identified 20 “critical” basins, including those under Harvard’s vineyards, that needed to develop plans by 2020 to limit groundwater drawdowns.

To help write those water plans, large landowners in Shandon voted in 2017 to create their own water district governed by a five-member committee. Mr. Turrentine was elected to the committee, giving Harvard a voice in the planning.

The groundwater basin in nearby Cuyama Valley was also on the “critical” list. Mr. Turrentine’s Grapevine hired hydrologists to argue to the state that there was a geologic fault separating Harvard’s Cuyama vineyards from the rest of the basin.

So far, the state has disagreed with Harvard’s request to designate a new basin—a designation that would mean it wouldn’t have to compete with some big farms for limited water allotments.

“If they start to pull on what I got,” says Jon Jones, a farmer near the Harvard vineyard, “there’s going to be an issue.”

Roberta Jaffe, who with her husband, Steve Gliessman, runs a small family vineyard and olive orchard nearby, is concerned warming weather is already making water more scarce and valuable. She worries Harvard could seek to send water toward cities in Southern California. As a precedent, she points to Cadiz Inc., a California water-supply company that has obtained county and federal permission to build a pipeline from under the Mojave Desert to sell 16.3 billion gallons a year to Southern California water utilities.

“The most unimaginable things can happen,” she says.

Harvard has applied to build three large lined reservoirs on its Cuyama Valley vineyard and is waiting to hear from county officials. Each could hold 16 million gallons. Ms. Jaffe and others have argued against it.

At a meeting this autumn of the local planning commission, Brodiaea consultant David Swenk said the company was within its rights to develop the water resources. “A farmer has a right to farm,” he said, “and can utilize the water under their property.”

Updated: 12-2-2019

The Water Wars That Defined The American West Are Heading East

Urban growth and surge in irrigation fuel fight between Georgia and Florida; soybeans or oysters?

Water stress, a hallmark of the American West, is spreading east.

The shift is evident on Casey Cox’s family farm in Georgia’s agricultural heartland, where she turned on five giant rotating sprinklers to see her sweet corn through weeks of hot, dry weather last spring.

“If we hadn’t had irrigation, our crop would have burned up completely,” said Ms. Cox, who with her father also produces soybeans, peanuts and timber on 2,400 acres.

More water to save Ms. Cox’s crops, though, often means less for neighbors to the south such as Rickey Banks. He gave up his life as a Florida oysterman when his fishery, which depends on water from the same river basin as Ms. Cox’s farm, collapsed during a drought.

Increasing competition for water is playing out across the eastern U.S., a region more commonly associated with floods and hurricanes and one that was mostly a stranger, until recently, to the type of bitter interstate water dispute long seen in the West.

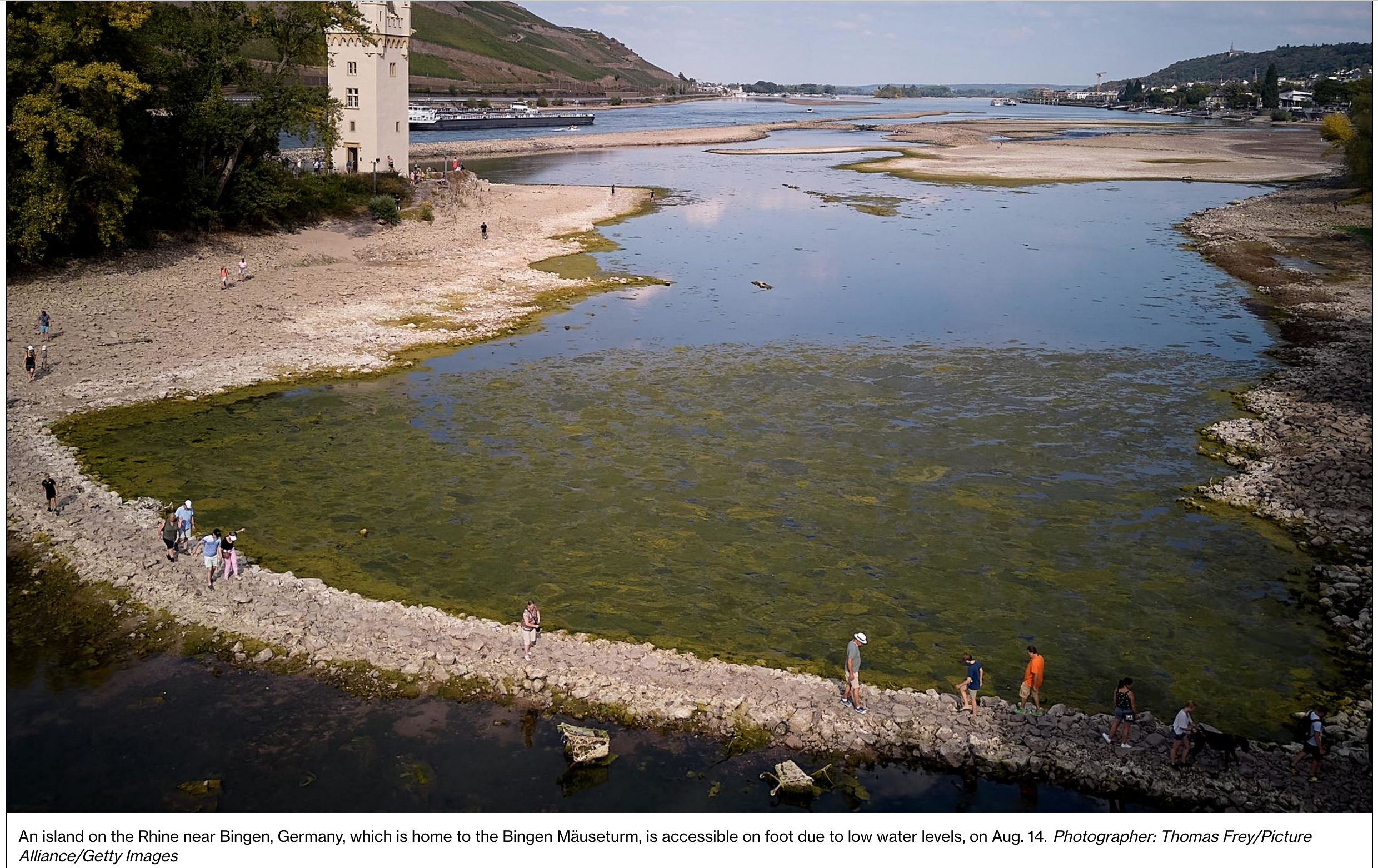

Eastern farmers’ rising thirst for water, together with urban growth and climate change, now is taxing water supplies and fueling legal fights that pit states against each other. The shift has exposed the region to changes in water supply occurring globally as swelling populations, surging industrial demand and warmer temperatures turn a resource seen as a natural right into a contested one.

In the U.S., burgeoning coastal populations have lowered water tables and dried up streams in Long Island, N.Y. Near Tampa, Fla., groundwater pumping has drawn saltwater into aquifers, drained lakes and triggered sinkholes. Decades of pumping by farmers and others have led to sharp declines in critical aquifers that flank the lower Mississippi River.

“What keeps me awake at night is not western water issues—it’s the East,” said Lara Fowler, an attorney and professor of water law and policy at Pennsylvania State University.

In 2013, Florida and Georgia’s long-running conflict over the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint River basin landed before the U.S. Supreme Court, the sole arbiter of interstate water disputes.

The legal battle inched forward in early November when a “special master” appointed by the high court, the second one the dispute has had, heard arguments from the states’ attorneys in a courtroom in Albuquerque, N.M. Special masters are servants of the Supreme Court, conducting hearings, building a record and issuing a report for justices to consider in cases that don’t move through lower courts. Ultimately, the special master will likely say which party should prevail and why.

One striking marker of expanding stress is the 100th meridian, a divide between water-rich and water-poor areas drawn nearly a century and a half ago by geologist and explorer John Wesley Powell. According to a team of scientists including those at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, the boundary—severing states from North Dakota to Texas—has shifted about 140 miles eastward since 1979 because of warmer temperatures or reduced rainfall. The scientists predict the West’s drier climate will continue to push eastward and pressure water supplies for farms and cities alike.

Eastward March

Irrigated agriculture has proliferated across the Eastern U.S. in the past half-century, as farmers sought to protect against dry spells and boost the predictability and profitability of harvests.

The threat is a familiar one for Mr. Banks in Florida, who in 2012 watched the oyster fishery that had sustained his family for decades fade amid a withering drought.

Florida blames Georgia farmers such as the Coxes, along with metropolitan Atlanta’s thirst, for the loss of such livelihoods. It says the explosion of irrigated agriculture in southern Georgia and Atlanta’s dramatic growth have drained too much water from the states’ shared river system, shrinking flows to Florida’s Apalachicola Bay.

The reduction, Florida argues, caused salinity to spike in the bay, fueling an invasion of oyster-eating predators such as conchs and sponges. Only a handful of oystermen ply the bay’s waters today, down from hundreds a decade ago. Local restaurants that once boasted their “seafood slept in the bay last night” now import oysters from Texas or Louisiana.

Mr. Banks left Florida in search of carpentry work, eventually returning to launch a charter service that takes guests fishing and hunting for wild boars and alligators.

“Oystering was a heritage, not only a job,” said Mr. Banks, 49, who began working on his father’s oyster boat at the age of five.

The Oyster Business Has Faded in Florida’s Apalachicola Bay

Hundreds of oystermen plied waters of the Apalachicola Bay in Florida until a rise in salinity brought in more oyster-eating predators. In a suit against Georgia, Florida says more irrigated farming means too much fresh water is drained from a river system the states share.

Irrigated acreage in Georgia increased 15-fold from 1960 to 2015, according to U.S. Geological Survey data, as farmers sought to boost the predictability of their harvests. Much of the increase is along lower portion of the Flint River, which rises near Atlanta and runs south through some of Georgia’s most productive farmland.

Crop yields in the state have soared. President Jimmy Carter, who ran his family peanut farm before he ran the country, once honored Georgia farmers who harvested a ton of peanuts per acre. Their descendants can raise triple that. So critical is irrigation, farmers say, that most bankers won’t finance their operations without a system installed.

At peak times in the growing season, farmers in the lower Flint River basin pull hundreds of millions of gallons of water a day from an aquifer called the Floridan that helps feed the river through fissures in the limestone below ground. Gordon Rogers, executive director of an advocacy group called the Flint Riverkeeper, says that during brief periods, the farmers’ water draw equals that of metropolitan Tokyo.

Growing Thirst

Burgeoning populations, particularly in the Southeast, are taxing water supplies.

The area around the Cox farm, in the southwest corner of the state, bordered by Alabama and Florida, is blessed with rain, an average of 52 inches a year. Winter and early spring are particularly wet in this area.

For a farmer, however, timing is everything. Two or three weeks without rain during critical phases of crop development can sharply reduce the yield as well as the quality of a crop such as sweet corn.

In a wet year, rainfall quickly replenishes the Floridan aquifer. But as irrigation wells have multiplied, far less water has flowed from Georgia into Florida during droughts. In 2012, water in the Flint dropped dramatically. Creeks that flow into it, with names from the region’s Native American heritage—Ichawaynochaway, Kinchafoonee and Muckalee—almost or entirely dried up.

Beyond Georgia, farmers across the eastern U.S. have steadily embraced irrigation, outfitting fields with rotating sprinklers to precisely control when their crops get water and how much. Irrigated acreage quadrupled in Tennessee and more than doubled in Indiana, Delaware and South Carolina between 1997 and 2017, according to government data.

Irrigation’s eastern push lies at the heart of Florida v. Georgia, one of three interstate water disputes pending before the Supreme Court. Western states have sent such disputes to the high court for more than a century. Now eastern states are the combatants in two of the three water cases before the court.

Florida seeks to limit Georgia’s water use. In 2015, Florida’s attorneys subpoenaed the Cox farm, arriving during the fall harvest to collect a decade’s worth of irrigation records and more. The two states have submitted more than seven million pages of documents, said a person familiar with the case.

The special master appointed by the court recommended the Supreme Court deny Florida’s request for a cap on Georgia’s water use, saying he wasn’t certain that a cap would result in enough additional water at the right times to benefit Florida.

That is because of the central role of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which manages dams and reservoirs in the region and controls when and how much water is released. Since it isn’t a party to the case, the Corps wouldn’t be bound by any court order, the special master said. The recommendation echoed Georgia’s argument, which also calls Florida’s problems largely self-inflicted.

After a hearing before the Supreme Court last year, the Justices decided 5-4 to reject the special master’s proposal. They named a second special master.

Overdrawn

Pumping too much water from the aquifers that feed rivers and streams depletes them.

At her farm near Camilla, Ms. Cox, 28, called irrigation the single most effective risk-management tool a farmer can have and said irrigation technology has grown more efficient over time. “If you took it away from us, we would not be able to farm,” she said, as she checked one of her family’s nine center-pivot sprinklers, stretched like a winged bird over a field of sweet corn.

Every few minutes, her phone dinged with a message from the center-pivot, telling her when it had turned on or off or had changed direction. “My pivot will not stop texting me,” she said.

En route to another field, Ms. Cox wound past pine-tree plantations and live oaks draped in Spanish moss, ticking off achievements irrigation made possible. Georgia produces more peanuts than any other state. A predictable water source means its farmers are reliable suppliers to candy companies such as Hershey Co. and to peanut-butter makers like J.M. Smucker Co.

Irrigation has also enabled farmers to plant higher-value but thirsty vegetable crops that can boost profits, and helps produce robust grain crops to supply chicken producers such as Tyson Foods Inc. Along with related businesses, agriculture contributed $16.7 billion to southwest Georgia’s economy in a recent year, according to the University of Georgia.

“Irrigation is the linchpin of our economy,” said Glenn Cox, Casey’s father, who is 64.

Throughout the East, newer industrial activities such as oil-field hydraulic fracturing also are demanding more water. “Out West, those states were water-stressed before any Europeans showed up,” said Matthew Draper, an attorney who specializes in transboundary water disputes. “Out East, we’re just now starting to bump up against that limit where someone using water means someone else is going to go without.”

The Coxes said the multiyear drought in California prompted vegetable growers there to invest in farmland in southern Georgia and northern Florida. Bo Abrams, a professor of water law at Florida A&M University College of Law in Orlando, predicts that over time, water shortages will drive ranching and field-crop production eastward from Arizona and the Great Plains.

At the same time, in Georgia, “What we’re seeing is periods of drier dries and wetter wets,” said Murray Campbell, a farmer who grows cotton and peanuts 20 miles east of the Coxes.

That trend is likely to continue, according to the latest U.S. National Climate Assessment, a legally mandated report spearheaded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. More frequent and severe droughts in places such as the Southeast could increase conflicts over water, experts say, even as periods of heavy precipitation like those that brought flooding to the Midwest last spring occur more often. Flooding drowns fields in too much water, and drought conditions still can develop between fewer, larger storms.

More states in the East are placing first-ever restrictions on permits for water use, said Barton “Buzz” Thompson, a professor of natural-resources law at Stanford University, who served as special master in a decadelong fight between Montana and Wyoming over Yellowstone River water.

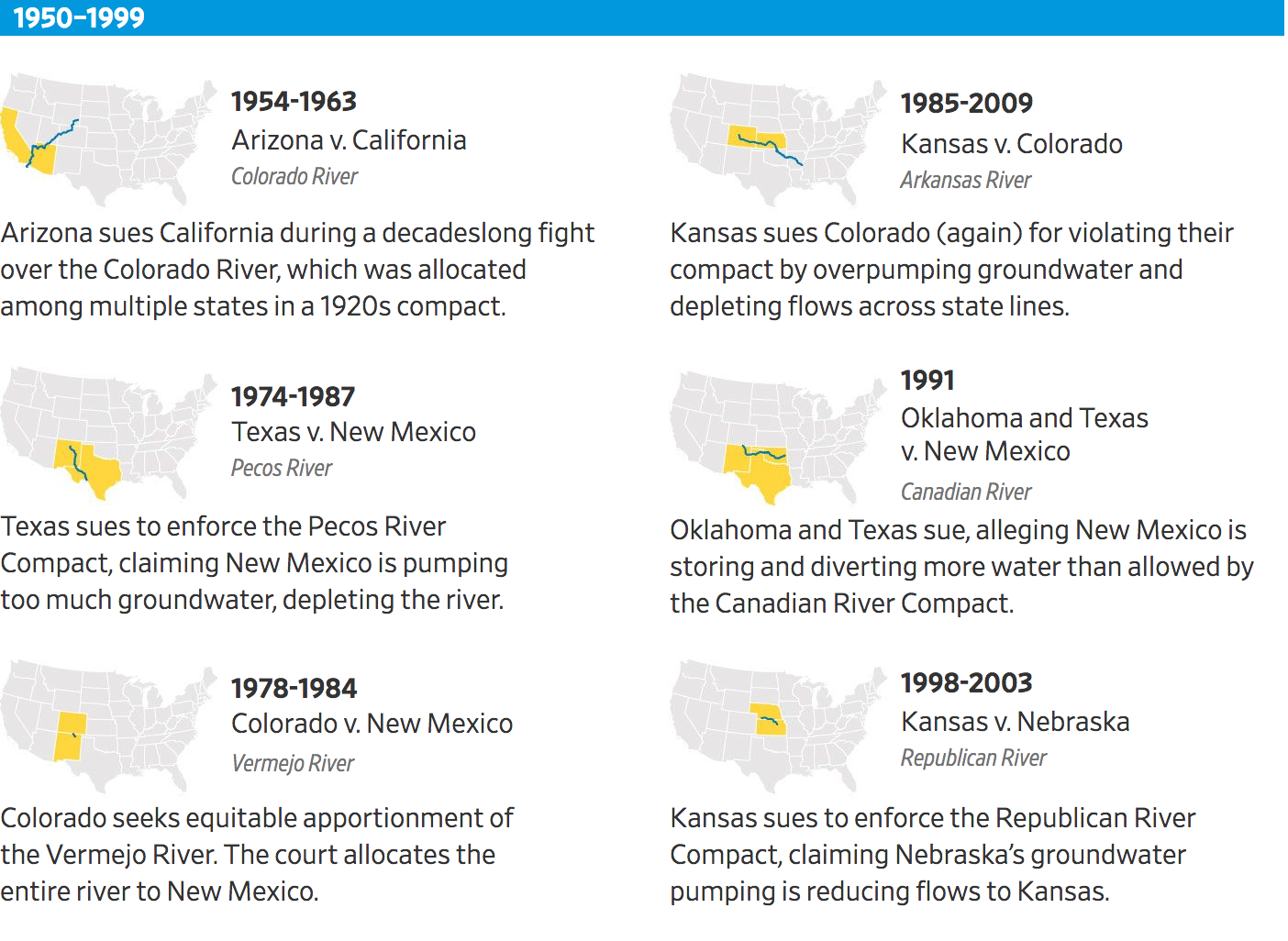

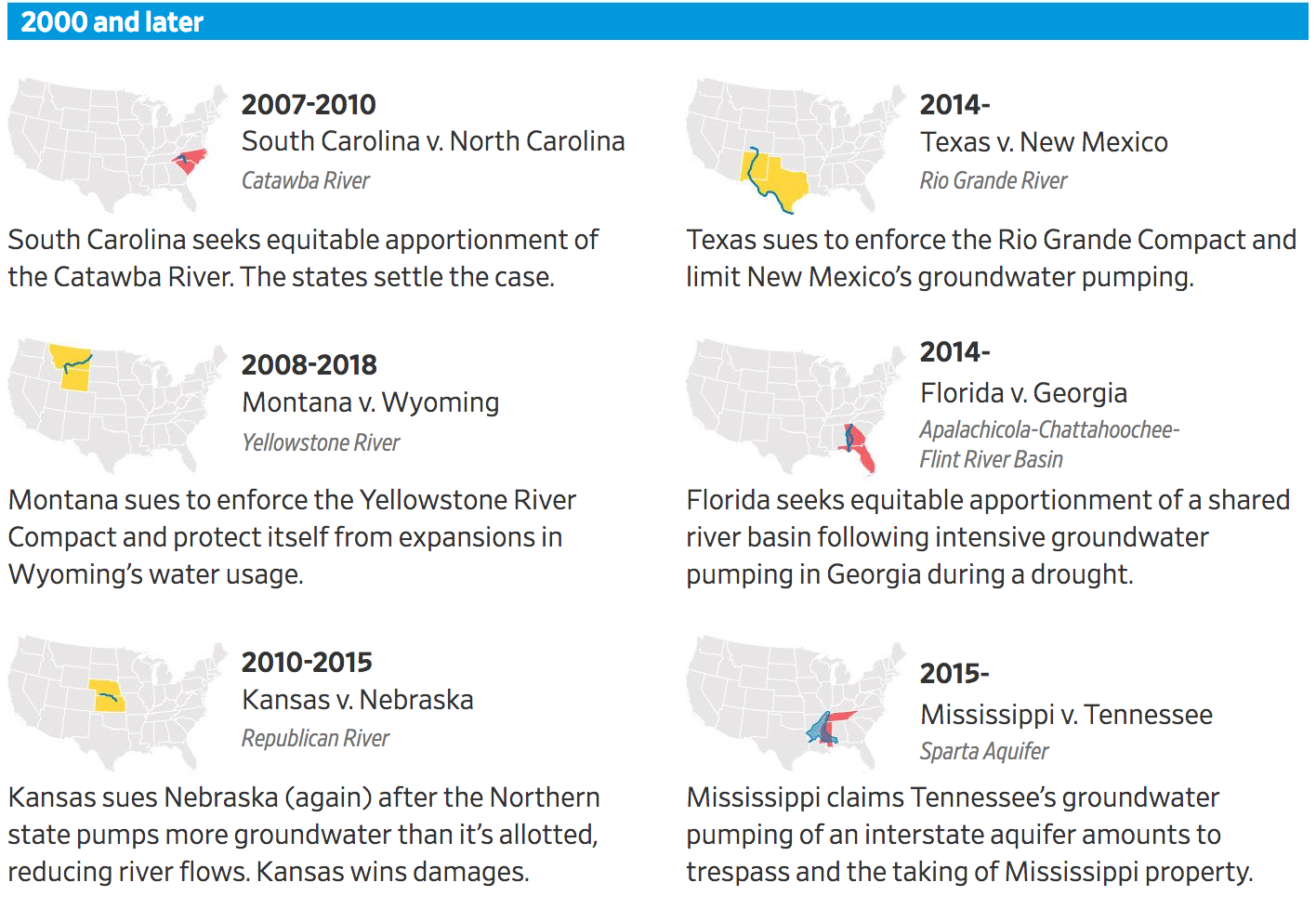

Water Wars

Interstate battles over water supplies, long a part of life in the American West, are spreading east.

Some water experts say eastern states are still unprepared for scarcity, armed with a patchwork of regulations and laws that assume water will remain plentiful. Unlike in the West, where most major river basins are governed by interstate compacts, only a few such agreements exist in the East.

In Georgia, a moratorium on new drilling into parts of the Floridan aquifer has slowed expansion of irrigated farmland in the Flint River basin for now. Farmers are allowed to drill into deeper aquifers, although that is more costly.

Uncertainty about the Supreme Court case has introduced new risks. Restrictions on agricultural water use could make a land purchase seem foolish, said Mr. Campbell, the cotton and peanut farmer. “That’s the kind of thing guys lay awake at night thinking about—what if I can’t irrigate that land?” he said.

“We see the conflicts and realize you’ve got to do something,” Mr. Campbell said. “But it would be difficult for us to turn the water off.”

Updated: 12-6-2020

California Water Futures Begin Trading Amid Fear of Scarcity

Water joined gold, oil and other commodities traded on Wall Street, highlighting worries that the life-sustaining natural resource may become scarce across more of the world.

Farmers, hedge funds and municipalities alike are now able to hedge against — or bet on — future water availability in California, the biggest U.S. agriculture market and world’s fifth-largest economy. CME Group Inc.’s January 2021 contract, linked to California’s $1.1 billion spot water market, last traded Monday at 496 index points, equal to $496 per acre-foot.

The contracts, a first of their kind in the U.S., were announced in September as heat and wildfires ravaged the U.S. West Coast and as California was emerging from an eight-year drought. They are meant to serve both as a hedge for big water consumers, such as almond farmers and electric utilities, against water prices fluctuations as well a scarcity gauge for investors worldwide.

“Climate change, droughts, population growth, and pollution are likely to make water scarcity issues and pricing a hot topic for years to come,” said RBC Capital Markets managing director and analyst Deane Dray. “We are definitely going to watch how this new water futures contract develops.”

The United Nations has long warned that human-driven climate change is leading to severe droughts and more flooding, making water availability increasingly less predictable. In California, the most recent acute dry spell stretched from December 2011 until March of last year, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. The most dire effects took hold in July 2014, with 58% of the state’s land suffering “exceptional drought,” leading to crop and pasture losses and other water emergencies.

The futures are tied to the Nasdaq Veles California Water Index, which was started two years ago and measures the volume-weighted average price of water. The January 2021 water contract that went live Monday had two trades.

“I’m delighted we’ve had trades,” said Clay Landry, managing director at consulting firm WestWater Research, which provides the data used to calculate the water index. “In the physical market, it’s so hard to get a deal done. This feels like lightning fast to me.”

The index sets a weekly benchmark spot price of water rights in California, underpinned by the volume-weighted average of the transaction prices in the state’s five largest and most actively traded markets.

The futures are financially settled, as opposed to requiring the actual physical delivery. Contracts include quarterly ones through 2022, with each representing 10 acre-feet of water, equal to roughly 3.26 million gallons.

According to Chicago-based CME, the futures will help water users manage risk and better align supply and demand.

Water Shortages

Two billion people now live in nations plagued by water problems, and almost two-thirds of the world could face water shortages in just four years, Tim McCourt, global head of equity index and alternative investment products at CME, said in an interview. “The idea of managing risks associated to water is certainly increased in importance.”

Currently, if a farmer wants to know what water will cost in California six months from now, it’s kind of a “best guess,” Patrick Wolf, senior manager and head of product development at Nasdaq, said in an interview.

The futures will allow market participants to see “what is everybody’s best guess,” he said.

Barton “Buzz” Thompson, a professor of natural-resources law at Stanford University, said while he has “no idea” if the futures will be successful, he doesn’t see it as a transformation of the water market.

“I don’t think the futures contract itself is really changing the water markets,” Thompson said. “Nor is it changing the risk that exists out there that water in the future at some point will be in shorter supply, it’s simply responding to those things.”

CME declined to identify potential market participants, except to note that the exchange has heard from California agriculture producers, public water agencies, utilities as well as institutional investors like asset managers and hedge funds.

Landry of WestWater Research said in addition to the likelihood of a “great deal of interest” from Wall Street, he expects the early water futures adopters to be large and small agriculture businesses.

“Without this tool people have no way of managing water supply risk,” Boise, Idaho-based Landry said in an interview. “This may not solve that problem entirely, but it will help soften the financial blow that people will take if their water supply is cut off.”

Updated: 6-12-2021

CME, Nasdaq To Launch Water Futures Contract

Market will be first of its kind for world’s most crucial commodity, organizers say.

Farmers are known to pray for rain. Now they can hedge against unanswered invocations.

Exchange operators CME Group Inc. and Nasdaq Inc. are planning to launch a futures contract later this year that will allow farmers, speculators and others to wager on the price of water.

The market will be the first of its kind, its creators say, putting water on the board for investors alongside other raw materials like crude oil, soybeans and copper.

“You have the most important commodity in the world and everything else is listed except the water price,” said Lance Coogan, chief executive of Veles Water Ltd., which created a water-price index to which the futures will be tied.

Besides allowing farmers, manufacturers and other big water users to protect against price swings, water futures can serve as a risk-management tool for other investors, Mr. Coogan said. They could be used to hedge against inflation or climate change or simply serve as an asset that is uncorrelated to others, he said.

The futures will reflect transactions in the market for water in California, which a huge population and vast agricultural lands make America’s thirstiest state. Water futures contracts will be priced in dollars an acre-foot, which is the volume required to cover an acre a foot deep, about 325,851 gallons.

Last week, an acre-foot of water cost $526.40, according to the Nasdaq Veles California Water Index. That is a 25% decline since the start of summer. Prices tripled in spring due to a historically dry February in California.

The prices are derived from prior-week purchases in markets for California surface water and in four groundwater basins in the state. Nasdaq and London-based Veles launched the index in October 2018.

Nasdaq, best known for listing tech stocks, had been pitched water pricing before, but Veles was the first to produce a data set of actual transactions with volume and history sufficient for a pricing index, said Patrick Wolf, senior manager for Nasdaq Global Indexes. The aim was to present a reference point for buyers and sellers in an otherwise opaque market.

“They might know a few other deals in their local part of the market,” Mr. Wolf said. “They don’t have access to the full market of buyers.”

Layering futures trading on top of the index was the next step. Trading will be hosted by CME, which makes options and derivatives markets in assets ranging from stocks to livestock, lumber and cheese.

Water futures will be available for trading up to two years out over 10 monthly contracts: one every three months along with the two most immediate nonquarterly months. Each contract will stand for 10 acre-feet of water.

Unlike in markets for many commodities, buyers won’t have to find somewhere to put 3.3 million gallons of water if they hold an expiring water futures contract. Whereas a buyer of a West Texas Intermediate crude future in the same situation must take delivery of 1,000 barrels of crude at a pipeline junction in Cushing, Okla., water wagers are purely financial and squared up with cash.

“There’s no big water fountain like there would be for oil in Cushing,” Mr. Wolf said.

Had there been water futures, a farmer who bought summer-dated futures at the prevailing price months earlier could have pocketed big profits when drought hit and prices soared. Those gains could then be used to offset the higher cost of buying actual water.

“You’re just moving dollars so it will be relatively straightforward to trade and to settle,” said Tim McCourt, CME’s head of equity index and alternative investment products.

Updated: 6-28-2021

New Water Wars Are Coming To The American West

The region’s most severe drought yet signals a grim future of expanding battles over who gets the rights to the last drops.

Water has been generating conflicts and controversies in the U.S. for centuries, but the American West could be heading toward the most severe water shortages and skirmishes in the nation’s history.

The latest clash broke out this month along California’s border with Oregon in the Klamath River basin, where drought is decimating wild salmon populations. To minimize the kill, federal officials cut off water to nearby fields growing potatoes and alfalfa, leading to grave concern from farmers and protests from anti-government activists.

Meanwhile, all the other Klamath River stakeholders — indigenous tribes with ancient claims, utility managers for growing cities in Southern Oregon and Northern California, dams running hydroelectric plants, golf courses and homeowners — are clamoring for their piece of the river.

The Klamath rebellion is the worst case for now — most Western water resources are peacefully managed during drought years, and many become more efficient and innovative. But it represents the kind of resource wars that could ripple throughout the West in the coming decades — perhaps even the coming months — if the Biden administration and Congress don’t chart a path forward on U.S. water security that helps ensure cooperation, conservation and ingenuity among state and regional water managers. Without swift national leadership, America faces rising water conflicts between regional haves and have-nots.

“Whiskey is for drinking, water is for fighting .”

— Western maxim

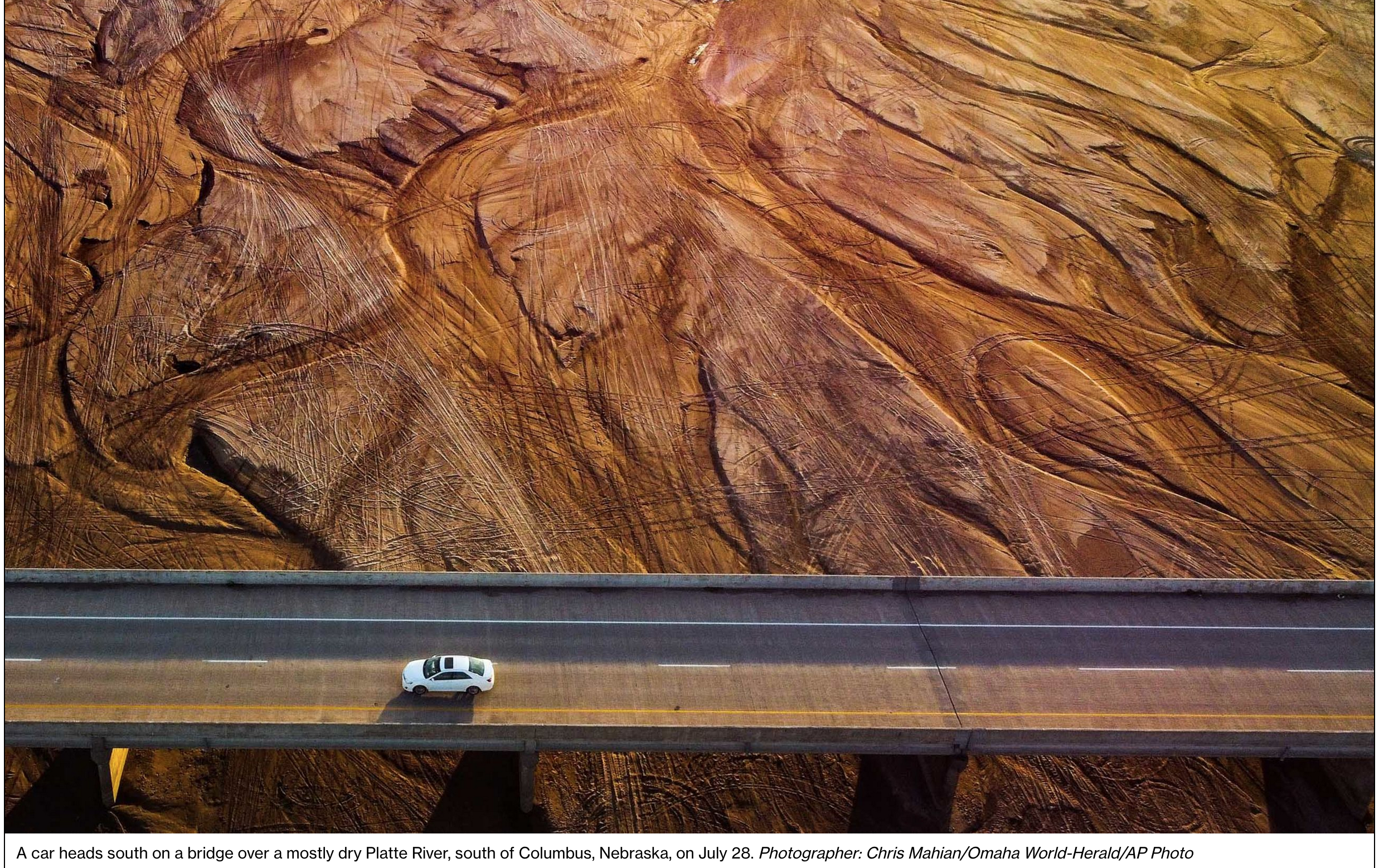

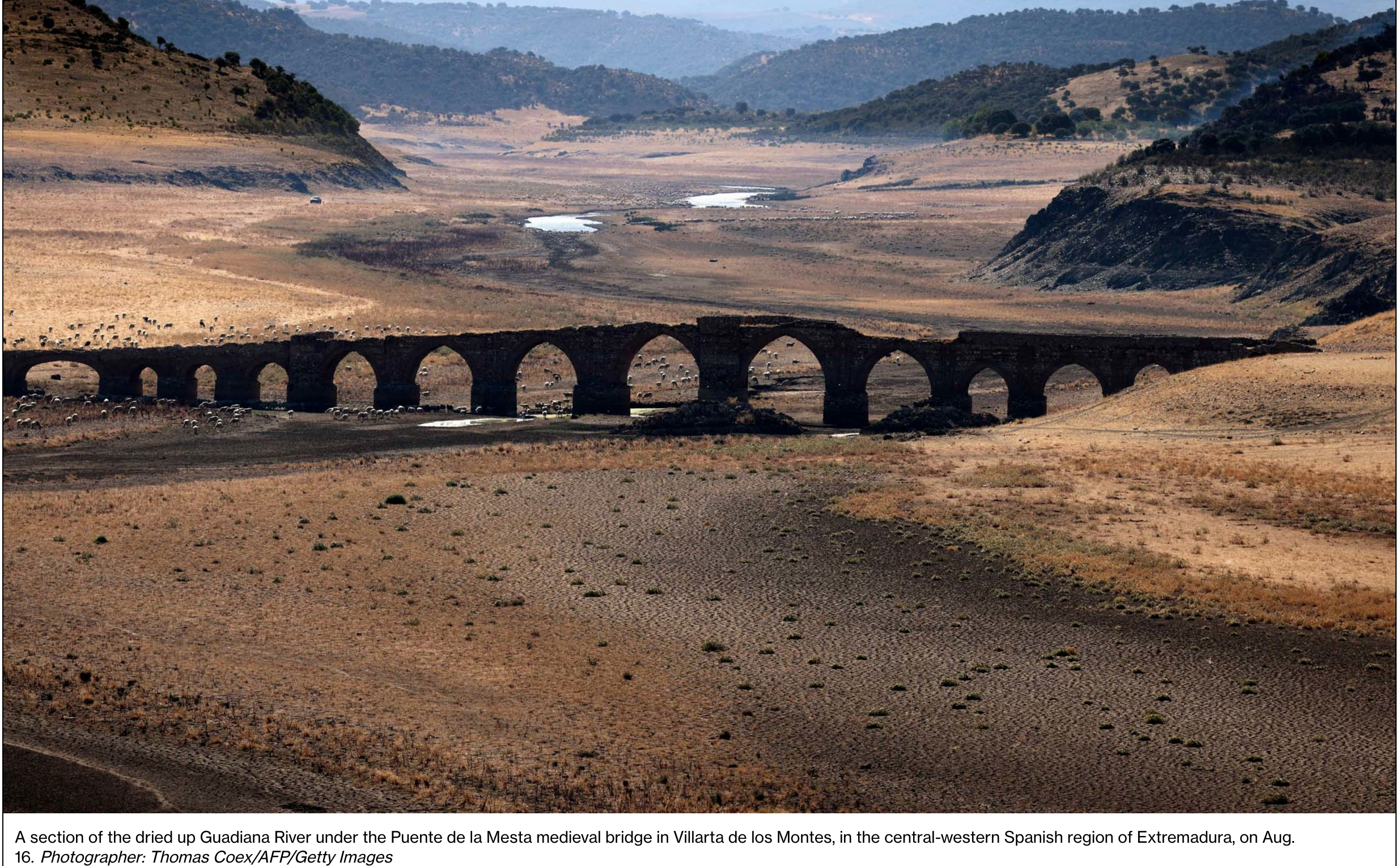

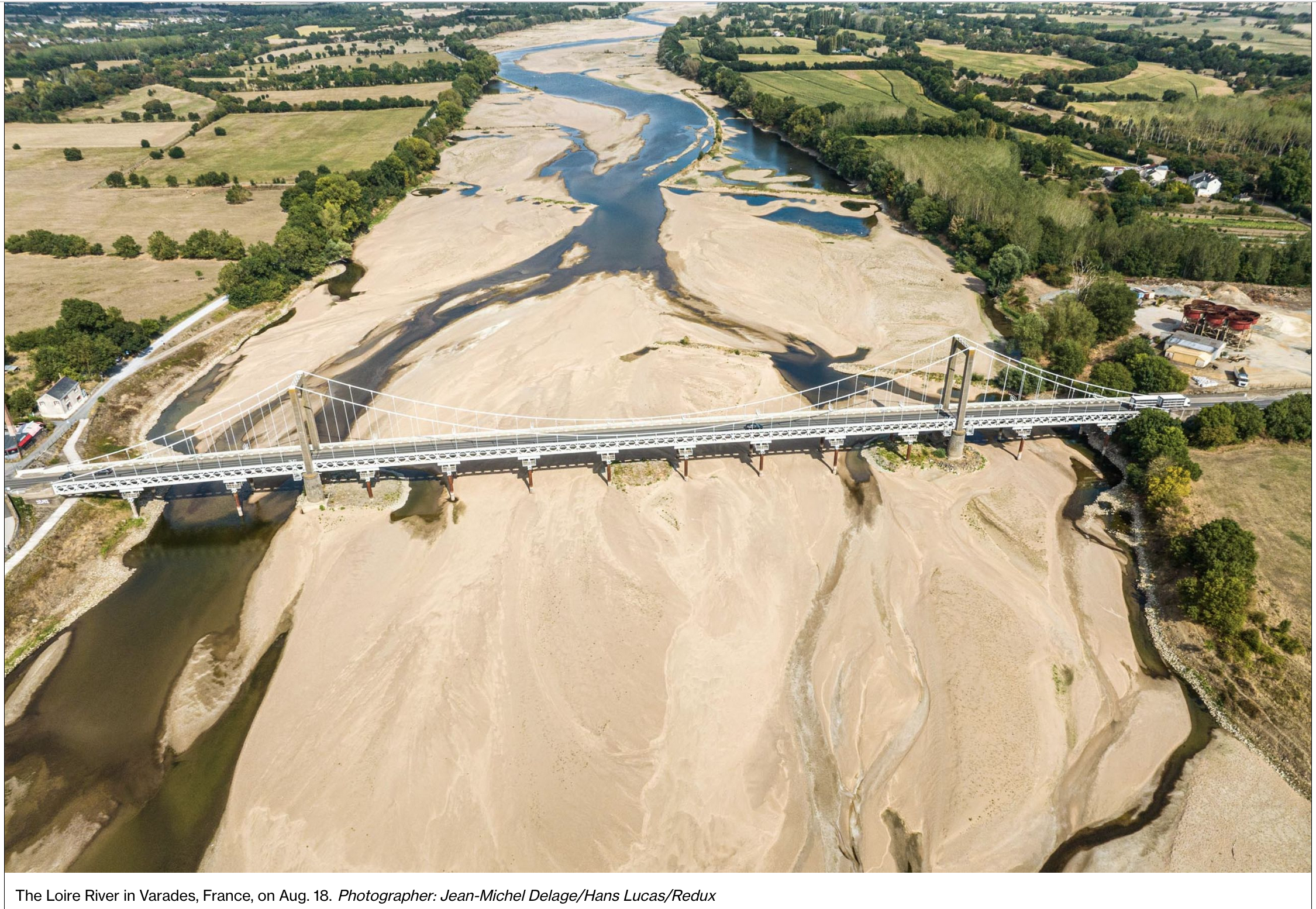

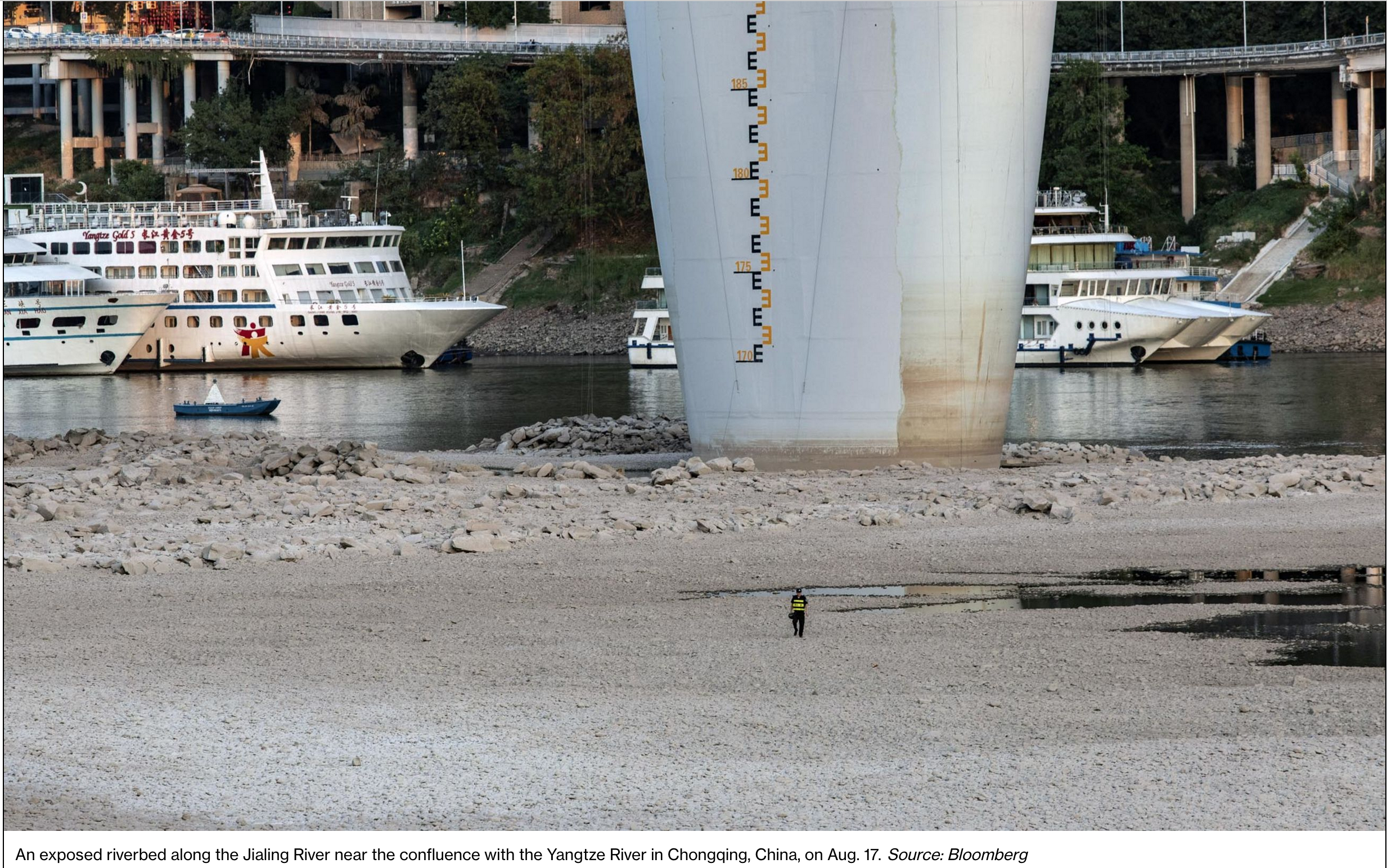

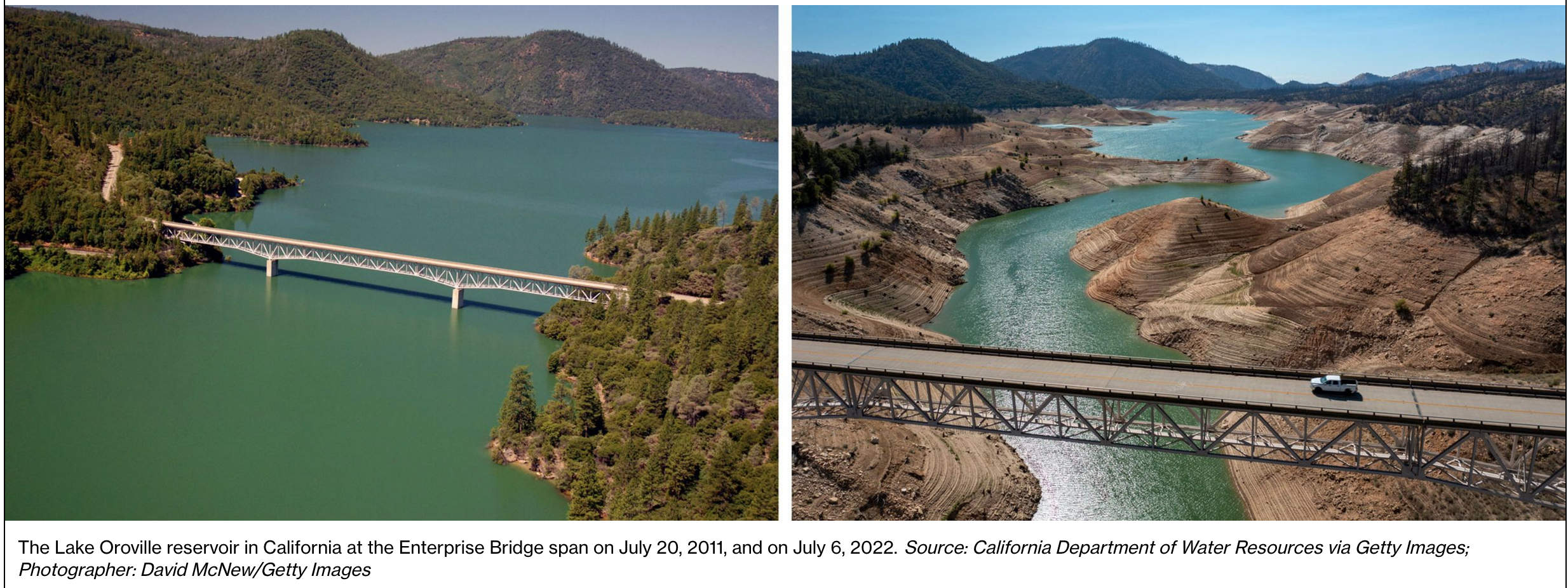

In the weeks since the Klamath dispute erupted, 88% of the American West has fallen into moderate to severe drought, with more than a quarter of the region in “exceptional drought,” according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. Lake Oroville in Northern California has hit literal rock bottom — it’s so low that its hydropower plant powering 800,000 homes is expected to go offline this summer for the first time ever.

Lake Mead, the largest reservoir in the U.S., supplying California, Nevada and Arizona, is at its lowest-ever levels. The snowpack runoff from the Sierra Nevada mountains is 74% below normal because evaporation and heat-parched land is absorbing the water before it can hit the reservoirs.

Former director of the Association of California Water Agencies and Stanford University Fellow Tim Quinn told me that even the most optimistic Western water managers are shaken: “It’s the first time we’ve ever seen hydrological scarcity matched with such severe high temperatures.”

The crisis is already reaching deeper into the country: Much of the upper Midwest is in moderate or severe drought. The Mississippi River is entering a low-flow state. The Ogallala Aquifer, which underlies eight Midwestern states from Texas to South Dakota, is expected to be 70% depleted within 50 years. In the next 30 years, the severity of widespread summer drought in the U.S. is projected to almost triple.

President Joe Biden and congressional leaders should be sounding a national alarm. Biden is supporting a $973 billion Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework that allocates $55 billion for clean drinking water infrastructure to eliminate lead in the nation’s service lines and pipes — an essential investment. Yet the framework allocates only $5 billion for Western water storage — an inadequate sum for upgrading aging dams, canals and pipelines to improve flows and reduce losses.

A coalition of hundreds of water and agriculture groups has identified a need of $14 billion over 10 years to shore up Western water reserves. The country needs not just one infrastructure bill in the near-term, but a sequence of bills over years to safeguard water supplies and reduce conflicts.

Biden should also issue an executive order to permanently establish the inter-agency group formed during the Trump Administration known as the “Water Subcabinet.” The group can help state water managers incentivize conservation, invest in new technologies and convene stakeholders within and between states to quell the brewing battles.

In Western states, water resources are generally governed by the “prior appropriation” doctrine, which holds that whomever settled in a region first has senior water rights; Eastern states support a “riparian rights” doctrine stipulating that if you have access to the river you can use it; Midwestern states have a blend of both doctrines, along with laws for drilling wells that tap aquifers.

In all cases, water rights function much like private property rights — they can be bought and sold. In the West, this has led to a buying frenzy over many decades — mostly cities and corporations buying farmers’ water rights. The practice became known as “buy and dry” as farms were drained of their water resources to supply growing cities. When mandatory restrictions come into play it inflames these tensions, as we’re seeing in the Klamath Basin.

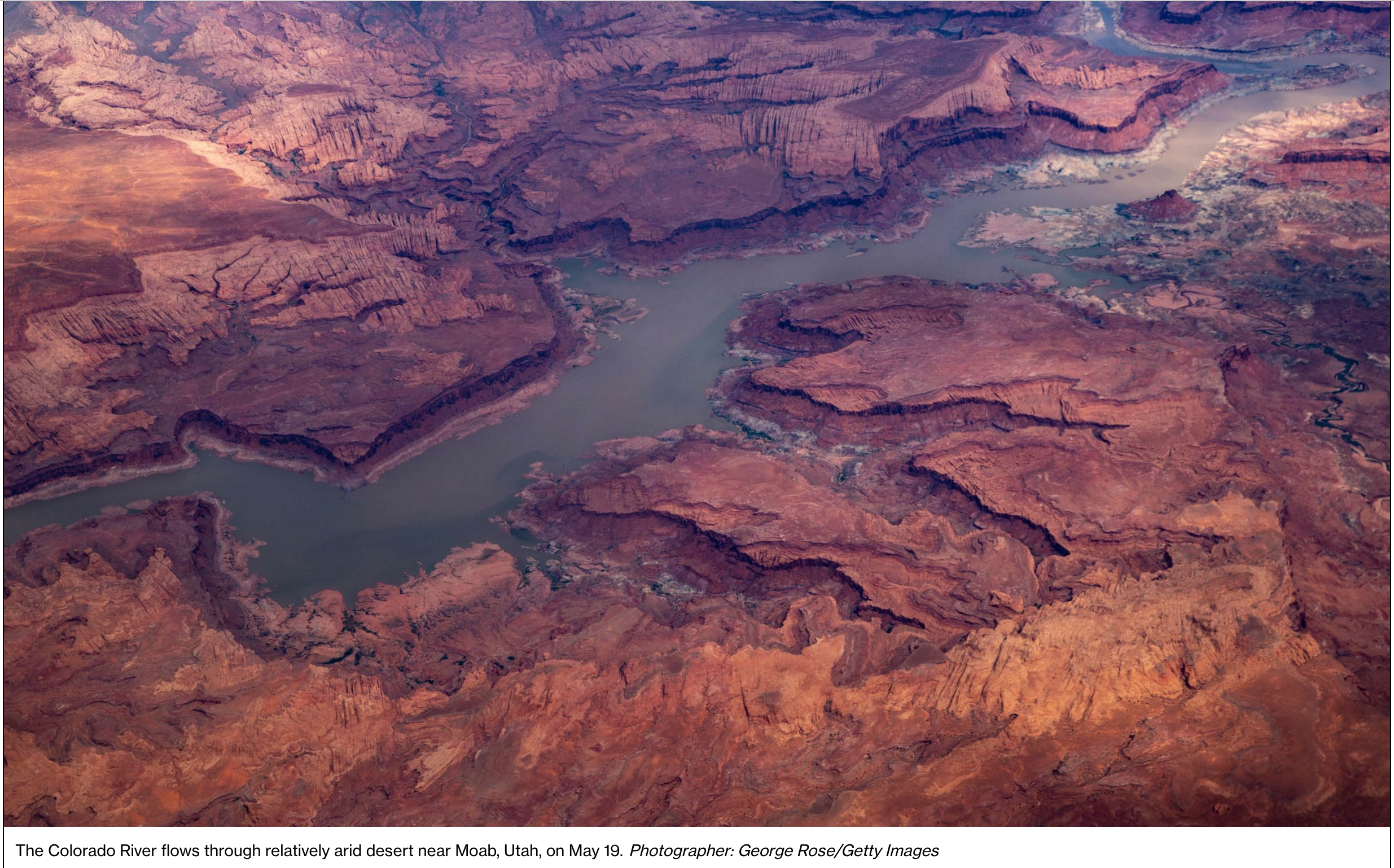

The local clashes could become much larger regional battles. The Colorado River Basin, for example, is divided between the Lower Basin, which spans wealthy, politically powerful and largely urban portions of California, Nevada and Arizona, and the agricultural Upper Basin, reaching across Utah, Wyoming, western Colorado and northern New Mexico.

The law technically allocates the same amount of water to both basins, but also grants the Lower Basin priority access. As the Colorado River dwindles (streamflow is 20% less than a century ago) mandatory restrictions could come into play, leading to protracted litigation among seven powerful states and economic devastation on both sides.

The good news is that scarcity can also lead to innovative partnerships and compromises. Recent agreements between Colorado farms and cities, for example, have creative alternative approaches to “buy and dry” transactions. Water managers are applying new technologies and legal strategies that allow a portion of the water supply to be diverted so both farm and city can thrive.

Across the nation, better forest and farm management can improve soil health, lock in moisture, and go a long way to protecting our future water supply. Emerging technologies can also play a role in drought resilience: recycled wastewater and desalination facilities can transform ocean water and sewage into hyper-pure drinking water; lining for canals and ducts and faster detection of pipeline leaks and bursts can avoid massive waste.

Investors should fund these innovations, as well as efficient agriculture technologies from dripline irrigation to the development of drought-tolerant crops.

Some of the world’s most intractable conflicts, spanning millennia — between India and Pakistan, for example, and Israel and Palestine — have been fueled by disputes over increasingly limited water resources. Water is the lifeblood of any economy — without it, there can be no agriculture (which accounts for more than 70% of global freshwater demand), no food sovereignty, no renewable hydropower and no economic growth. If we don’t plan ahead, many American states in and beyond the West will be embroiled in resource wars.

Updated: 7-12-2021

Drought Pushes U.S. Oat Crop To Lowest In Records Back To 1866

As drought conditions bake the upper reaches of the U.S. Plains, American farmers are now expected to harvest their smallest oats crop in records that go back to 1866.

Heat and dry weather are sapping yield potential in key growing states. This year’s U.S. harvest is estimated at 41.3 million bushels, the smallest ever, Department of Agriculture data showed Monday. The outlook is down from the agency’s June estimate of about 53 million bushels.

The USDA’s downgrade to the oats harvest is the latest example of abnormally hot and dry weather taking a toll on food production. Wheat futures have been surging and canola prices notched all-time highs amid a lack of rain in growing regions running along the U.S.-Canada border.

The dry conditions come after years of falling oats acreage as U.S. grain growers swapped it out for more profitable crops such as corn. This year’s low harvest compares with a peak of 1.15 billion bushels back in the 1960-61 season.

“There will be very few supplies left after this year,” Lorne Boundy, an oat farmer and merchandiser at Paterson Grain in Winnipeg, Manitoba, said by phone.

With the U.S. growing fewer oats, buyers are heavily dependent on imports, mostly from Canada. But that country is also suffering from dryness. Canada’s oat harvest this year could total about 268.7 million bushels, down nearly 15% from a year ago.

One saving grace might be more consumers going back to restaurants for breakfast, instead of preparing oats at home, as restrictions ease from the coronavirus pandemic.

“Hopefully there’s a little less demand as people return to a more take-out-restaurant diet,” Boundy said.

Updated: 8-13-2021

California’s Dry Season Is Turning Into A Permanent State of Being

Three forces linked by climate change are driving the region into a drought era.

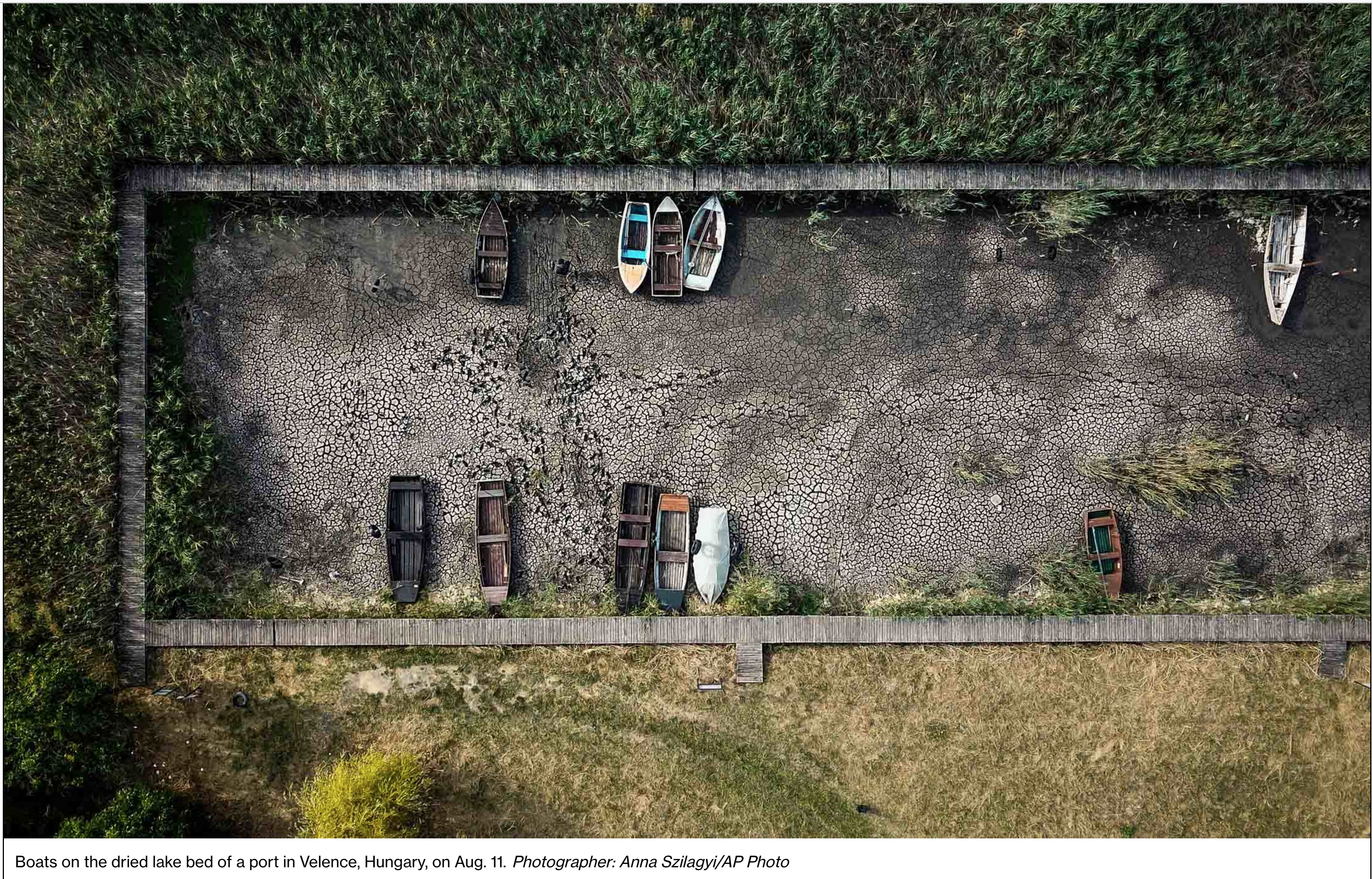

Drought across the Western U.S. has forced California to ration water to farms. Hydroelectric dams barely work. The smallest spark — from a lawnmower or even a flat tire — can explode into a wildfire.

While this region has always had dry summers, they’re supposed to follow a pattern that leads to relief with the arrival of the annual rainy season in November. But a break is no longer guaranteed.

In fact, there are now both short- and long-term factors drying out the Western U.S. Under the influence of fast-warming temperatures, as documented in detail by this week’s report from the UN-backed Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the region may be entering a drier state. Drought season might be giving way to a drought era.

Here are three forces desiccating the region.

A Second Consecutive La Nina Looms

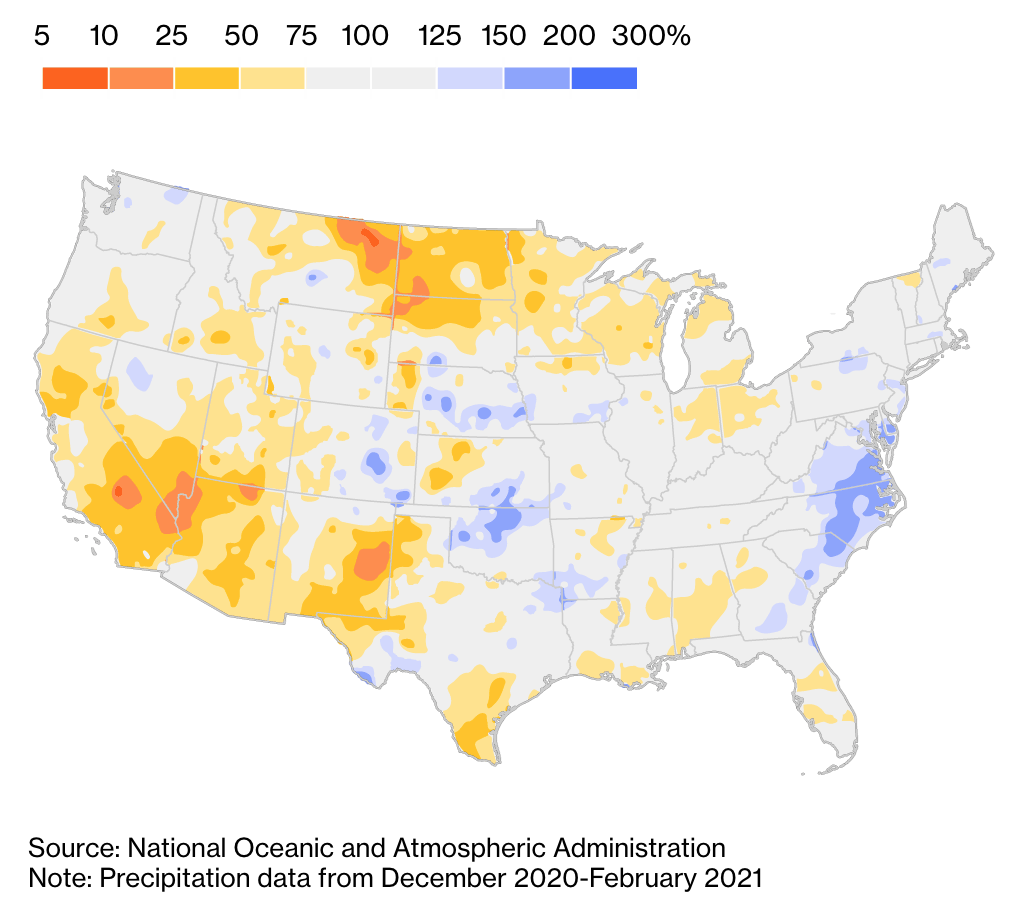

Parched Western Winter

Last Winter’s Precipitation, As A Percent Of The 20Th Century Average

The Climate Prediction Center just issued a forecast water managers in the Western U.S. didn’t want to hear. The latest report, released Thursday, puts the odds in favor of a second straight year of La Nina conditions in the Pacific Ocean.

La Nina tends to steer the storm track north of California, leaving most of the state and the Southwest parched. Last year’s La Nina is one of the reasons for the current drought. If the forecast had instead called for El Nino, the odds would have favored a wetter than average winter for California and the Southwest—something the region badly needs.

“If we want to see improvement of the drought across the West, the last thing you want to see is a back-to-back La Nina,’’ said Tom Di Liberto, a meteorologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. While it doesn’t always lead to a dry winter, it stacks the deck in favor of one.

La Nina is driven by a vast pool of unusually cool water near the equator in the eastern Pacific, just as El Nino is driven by warmer water in the same place. The consequences of La Nina aren’t all bad, since additional storms sent into the Pacific Northwest and Western Canada will help subdue devastating wildfires there.

The effects in Northern California are harder to predict. “California has the highest variability in precipitation anywhere in the U.S.’’ said Jeanine Jones, interstate resources manager for the California Department of Water Resources. “We cannot say what next year is going to be like.”

If the coming winter brings little rain and snow, the results will be troubling. California has already suffered through two dry years, leaving the soil so parched that what little snow fell in the Sierra Nevada Mountains last winter either evaporated into the air this spring or sunk straight into the dirt, leaving little runoff for rivers and reservoirs. Even with average winter rain and snowfall, runoff would remain low just because the land is so dry.

“If you have a string of dry years, that sets you up for low runoff efficiency in the next year,” Jones said. “It is going to take above average precipitation to get average runoff.”

Warmer Air Creates Parched Ground

A Hotter California

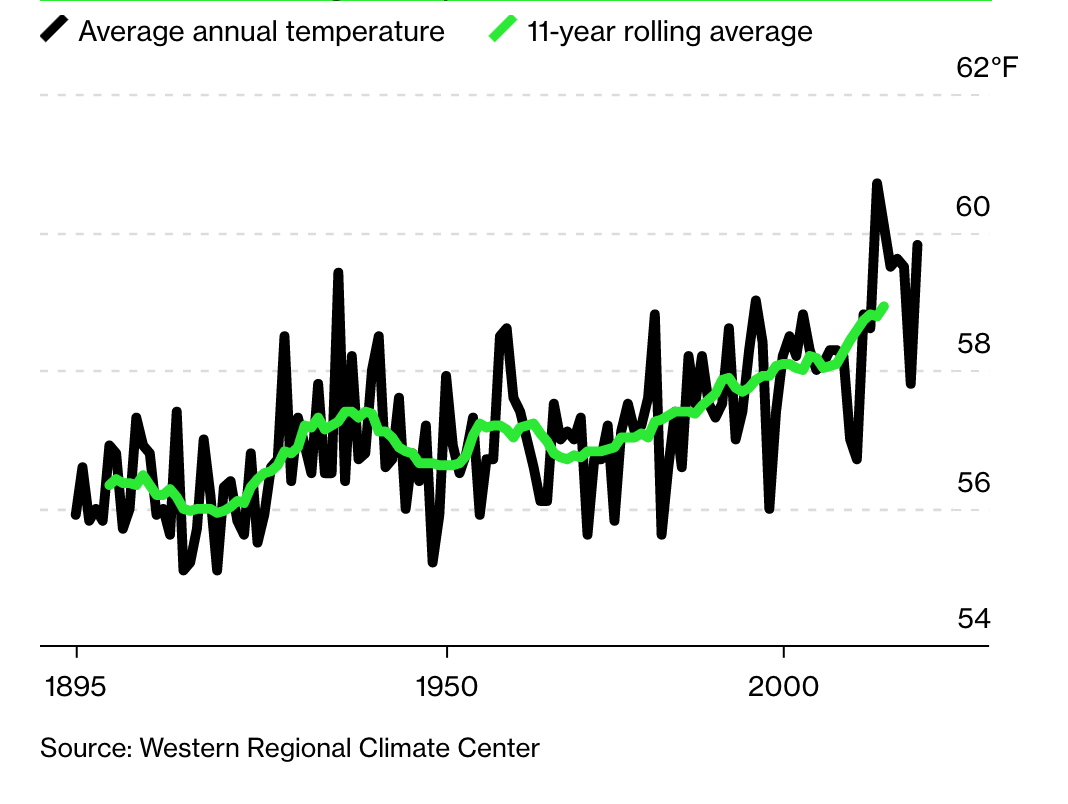

California’s Average Temperatures Have Risen For Decades

While La Nina can influence rainfall patterns over the course of a year, longer-range effects are also in play. One is hard to avoid because of climate change: hotter air.

Hot air holds more moisture, so the warming atmosphere is sucking up more water from plants and soil day after day, said Park Williams, a climate scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles. Williams studied tree-ring data stretching back 1,200 years and found four periods when the Western U.S. was gripped by “megadrought,” a dry period of unusual severity lasting decades.

Only the most recent one, at the end of the 1500s, had soil moisture levels as low as California has experienced in the first two decades of the current century.

That means the impact from warmer air might already be registering in the soil. “The normal really is changing to a drier state, and that trend is becoming clear,” Williams said.

If annual precipitation increased substantially, this could compensate for the daily drying. But Williams said most climate models don’t predict more rain. To make matters worse, his tree-ring study showed that the 20th century was actually an unusually wet period.

Our expectations of “normal” rainfall, in other words, have always been a little skewed. “Modern society really developed in the Western U.S. in the 1900s — that’s when all the infrastructure was built — and we’re experiencing conditions it wasn’t built to handle,” Williams said. “In the 1900s, society was able to really evolve in a period of ignorant bliss.”

In the short-run, meanwhile, the drier earth can amplify heat waves like the recent record-breakers in the U.S. and Canada. “Droughts lead to drier grounds, which lead to higher temperatures. It’s a vicious cycle,” Di Liberto said.

Hadley Cell Brings Dry Air

Dry Air From Above

An Air Current Called The Hadley Cell Is Expanding, Aiming Dry Air At The West

Think of the Hadley Cell as two constantly spinning wheels in the atmosphere, moving in opposite directions. Moist, hot air rises near the equator, then drops most of its moisture as rain before flowing towards the two poles. One current runs north, the other runs south. These currents descend back towards the surface drier than at the start of the cycle.

In the Northern Hemisphere, the current ends up close to the southern border of California, Arizona and New Mexico.

Scientists have speculated for years that climate change would expand the Hadley Cell, pushing its drier edge in each hemisphere closer to the poles. This week’s IPCC report found that’s happening, although only in the Southern Hemisphere could they blame the effect on global warming with confidence. (In the Northern Hemisphere, the change so far lies within a range that could be explained by natural variability.)

As it expands, California and much of the Western U.S. will fall more clearly in the bulls-eye of the cell’s drier air. Richard Seager, senior research scientist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, wrote about the effect in 2007, citing it as one of several factors that would lead to a drier climate in the West. Seager said there will be years when natural cycles like El Nino — with its wetter winters in California — will counteract some of the longer-term forces like the expansion of the Hadley Cell. But the overall trend is toward a more arid future.

“There are better cases and worse cases, but there aren’t any models saying that water availability in the Southwest will get better with climate change,” he said. “It’s a case of less bad or more bad.”

Updated: 8-14-2021

Severe Drought Could Threaten Power Supply In West For Years To Come

Water elevation at the Hoover Dam is at its lowest since Lake Mead was first filled.

As drought persists across more than 95% of the American West, water elevation at the Hoover Dam has sunk to record-low levels, endangering a source of hydroelectric power for an estimated 1.3 million people across California, Nevada and Arizona.

The water level at Lake Mead, the Colorado River reservoir serving the Hoover Dam, fell to 1,068 ft. above sea level in July, the lowest level since the lake was first filled following the dam’s construction in the 1930s. This month, the federal government is expected to declare a water shortage on the Colorado River for the first time, triggering cutbacks in water allocations to surrounding states from the river.

Widespread drought conditions throughout the Southwest over the past 20 years have led to a more than 130-foot drop in the water level at Lake Mead since 2000.

The Bureau of Reclamation’s latest projections, from July, show the lake’s water level falling another 31 ft., to 1,037 ft., by June 2023.

For dams to produce power, they rely on the immense pressure created by the body of water they are blocking. As water levels go down, less pressure is exerted and the dams in turn produce less hydroelectric energy, which means the dam can produce less power.

Every foot of water lost equates to about six megawatts less power generated, according to Patti Aaron, public affairs officer at the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, which operates and maintains the power plant. Six megawatts roughly translates to the power consumed by 800 homes.

If the water level drops 118 ft. from July’s level, to 950 ft., it would fall below the turbines and the dam must shut down, Ms. Aaron said.

The power declines are significant. At 1,200 ft. water elevation—where it was in the year 2000, when water levels were among the dam’s highest levels—the dam can power up to 450,000 homes. At the current elevation, that figure falls to 350,000.

The Hoover Dam is one of the nation’s largest hydroelectric facilities. About 23% of its power output serves Nevada, 19% serves Arizona, and most of the remainder serves Southern California.

The California Independent System Operator, or Caiso, which oversees the state’s power grid, last summer resorted to rolling blackouts during a West-wide heat wave that constrained the state’s ability to import electricity. The supply crunch was most acute in the evening, after solar production declined.

Maybe California Actually Does Have Enough Water

When a state has successfully defied nature and geography for so long, it seems unwise to presume the end is near.

It’s hard to know how much to panic over California’s dwindling water supplies. The state has never really had enough water, after all, yet lawns in Beverly Hills somehow remain perpetually green. Earlier this month, however, came a sign that life might soon be getting more uncomfortable for more Californians.

On Aug. 3, the State Water Resources Control Board voted 5 to 0 to issue an “emergency curtailment” order for the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta watershed. Last week the order was submitted to the state’s Office of Administrative Law, which is likely to approve it.

The watershed covers about 40% of the state, stretching roughly from Fresno to Oregon, and is California’s largest source of surface water. About 5,700 holders of water rights, largely in agriculture and business, will be affected by the reduction in water access. Although many farms have already drawn most of the water they need for the season, the board’s move was a sign that ancestral water rights won’t be a guarantee of actual water if drought persists.

America’s most populous state, home to many of the nation’s richest home-grown industries as well as its most lucrative agriculture, needs a lot of water to keep the miracles fresh. Movie and television productions, like the technology industry and the powerhouse universities that fuel it, don’t technically run on water. But they won’t run without it, either. And many of California’s high-value crops, including almonds and, increasingly, cannabis, are water hogs.

On the other hand: When a state has successfully defied nature and geography for so long, it seems unwise to presume the end is near.

Three quarters of California’s rain and snow falls north of Sacramento — though in recent years not much has fallen there, either — yet about 80% of water demand originates in the southern two-thirds of the state.

Water may flow downhill elsewhere. In California it arrives where nature never intended it after working its way through a series of dams, reservoirs, power plants, pumping stations and aqueducts managed by various federal, state and local authorities. At one point on a journey south, water is pumped 1,926 feet upward over the mountains, a vertical lift unequaled anywhere in the world.

Yet to pump water, there must be water to pump, and supplies are unquestionably running low. Most of the state is currently under a drought emergency declaration, and Governor Gavin Newsom has asked consumers to reduce usage by 15%.

Over the past two decades, there have been three dry years for each wet one. The past decade has produced a combination of grinding “mega-drought” accompanied by terrifying “mega-fire.” Snowpack in the Sierra Nevada has been alarmingly thin, with this year’s reduced runoff producing a deficit of almost 800,000 acre-feet of water, an annual supply for more than one million households. Reservoirs are low, rivers are depleted and aquifers have been drained and not replenished as Californians try to extract from below ground what they cannot obtain above.

Wells have run dry. Lake Oroville’s record-low water forced the shutdown of its hydroelectric plant. When it does rain, a baked landscape and record-breaking high temperatures cause much of the water to disappear before it can do any good. (For a detailed look at water despair, read my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Tim O’Brien on the parched Southwest.)

In one of the damned-if-you-do constructs that drought imposes, even saving water can be a hazard. Using drip-line irrigation, for example, or lined irrigation canals, reduces agricultural water loss.

But limiting loss reduces the amount of water flowing back into the ground, increasing the pressure on collapsing groundwater reserves. Likewise, if too little water escapes via river to the sea, saltwater can push against the reduced flow, into the delta, threatening ecosystems.

Some businesses have reached the existential-crisis phase of drought. Dry pastureland is already causing farmers to cull cows that they can’t afford to feed, and some wonder if it’s time to pack up the farm.

A vintner in Sonoma County, where this month the state curtailed access to water from the diminished Russian River, emailed to say that some local wineries probably won’t make it if wine country combusts in another devastating fire season. Given how dry the region is, and how voracious northern California’s Dixie wildfire has proved to be, no one is confident that Napa and Sonoma will make it to the winter without a full-scale emergency.

Fire isn’t just a byproduct of the water problem — it’s a contributor to it. According to a Sierra Club report, “after a fire, ash changes the land’s ability to self-regulate, burned forests tend to landslide, and scorched soil doesn’t hold moisture, which causes runoff and erosion.

Contaminants, carcinogens, and burned material run off downstream instead of being filtered out through the soil. Nutrients’ balance in the soil gets out of whack. Downstream debris chokes up riverbeds, reservoirs, and water treatment plants.”

It’s a measure of how tops-turvy the water situation is that Greater Los Angeles — a place that, water-wise, has no business even existing — is sitting relatively pretty. In the past three decades, the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California has increased its water storage capacity many times over.

During the wet seasons of 2017 and 2019, the district stashed liquid supplies across the region, and it’s drawing on them now. In addition, Los Angeles has made significant gains in reducing per-capita water consumption, and plans are underway to do more.

It may seem perverse that Los Angeles has water while Mendocino, in the north of the state, is running dry. But Jay Lund, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of California at Davis, has a different perspective. Lund is nowhere close to pushing the panic button on California. On the contrary, he argues — paradoxically and pretty convincingly — that things aren’t going so badly.

“How much water does most of the economy in the West need?” Lund asks. “Most of the economy in the West is urban. Half of the water use in most of the urban areas, at least in California, is for irrigating landscapes. Our per-capita water use in California is maybe 150 gallons per capita per day.

If you go to other prosperous, dry parts of the world, such as Spain or Israel, their per-capita water use in urban areas is on the order of a hundred liters per capita per day. So we have a tremendous amount of water conservation potential in the urban sector, which is more than 95% of the economy — it employs more than 95% of the people — before we really start to take a big hit. It’ll be inconvenient. It’ll not be what we’re used to. But it doesn’t fundamentally threaten prosperity.”

There are poor towns in the Central Valley where the wells are dry or toxic or both, and water is trucked in. But as Lund points out, California on the whole is both very affluent and technologically sophisticated. With enough money and science, even under chronic drought conditions, a lot of water problems can be mitigated. Some might even be solved.

Costly, high-profile, projects such as recycling waste water into potable water, as Orange County successfully does, are one route to water salvation. Others are more mundane. In 2014, then Governor Jerry Brown signed a far-reaching groundwater law, which is intended to manage supplies, and quality, in most places by about 2040.

Given that the majority of the state’s water goes to agriculture, perhaps the most obvious path is simply paying farmers not to grow crops, and then commandeering their water allotment. California’s water system is, in many ways, already a vast liquid souk where deal-making and trades determine who has water and how much.

Water rights acquired prior to 1914 are the coin of the realm — but other currencies, and hedges, are accepted. On the website of the California Resources Control Board, the Frequently Asked Questions page on water rights runs to almost four dozen questions and more than 8,600 words. (For less common queries, consult a water-rights lawyer. There are plenty of them.)

But this heavily regulated market mostly works. The Metropolitan Water District, for example, pays farmers in the Bard Water District, in California’s southeastern corner, not to grow crops. Under a seven-year deal, Metropolitan captures as much as 6,000 acre-feet of Bard’s water from the Colorado River.

It’s a modest amount of Southern California’s needs. But it’s easy to see how the template can be applied to agricultural districts throughout the state.

The tradeoffs between high-value and low-value crops, and the relative amounts of water they consume, are getting increased attention. Most California agriculture ends up in the national or global marketplace. Californians aren’t going to starve if a percentage of their farms exchange water for cash and leave the fields fallow.

California’s urban districts, Lund says, are increasingly striking water purchase agreements like the one Metropolitan has with Bard. “During dry years, you move some water out of lower-value agriculture for cities and, for that matter, from lower-value agriculture into higher-value agriculture,” he says.

That has ramifications for employment, but not necessarily straightforward ones. “The farmers will make money because they’re going to get paid not to grow,” Lund points out. Farm laborers are likely to suffer, but overall employment is fortified by channeling water from agricultural regions to urban areas.

“It turns out that the water that you find from agriculture goes largely into urban landscape,” Lund says. “And the number of people employed in urban landscaping is actually higher than the number of people employed in most of the crops that you’re fallowing.”

Conflict over water is a staple of California politics. The state has reduced the supply of water to the city of Napa, for example, which, in turn, is limiting supplies to residents outside city limits.

The cost, and stress, that those residents shoulder produces resentment. If drought continues, there will be more angry people, and more to be resentful about, in more places. Even Lund acknowledges that, in some California locales, water scarcity constitutes a genuine crisis.

Lund doesn’t want to minimize the suffering caused by drought, he says, but water risks are inherently part of life in this long, coastal sliver of a warming planet. Like supplies of other resources — oil, water’s dirty cousin, comes to mind — water in the West is finite, at least year to year. And there is no law that it must be cheap or readily accessible. But California has the capacity, and wealth, to manage geographic- and climate-induced scarcity.

Current conditions, he says, are a crucible — a “test of our understanding of what we actually want, and what we can actually sustain, in this environment.” By forcing the state to adapt, in other words, drought is also forcing it to build the resilience it needs for the future.

It’s a technocratic proposition as much as a philosophical one, at a moment when technocrats are under concerted assault. Ultimately, the success of hydrology in California depends on public policy as much as on snowpack and aquifer levels, which will likely continue to fall short of the state’s goals. And public policy is muddling forward in the right direction.

“Because we don’t just panic about these problems, because we are mostly organized about them, we make reasonable progress,” Lund says. In a land where the ground is cracked and the sky is on fire, that counts as optimism.

Updated: 8-19-2021

How Johannesburg’s Dirty Little River Could Help Ease Water Woes And What U.S. Could Learn

The Jukskei River starts as a trickle near an auto shop and a liquor store. Then it picks up trash and E. coli. Cleaning it is a tall but necessary task if South Africa’s largest city wants to shore up its water security.

New York has the Hudson River, Paris the Seine, Cairo the Nile. Johannesburg has the Jukskei River — a meter-wide trickle that emerges from underground in the city’s business district near an auto-repair shop and a liquor store.

The Jukskei is strewn with trash and laden with coliform bacteria. It could also provide an unlikely boost to the water security of South Africa’s largest city.

Municipal water supplies across South Africa have been threatened by waves of drought, with Cape Town coming close to a total outage in recent years. Johannesburg has also flirted with shortages, which are complicated by the city’s unusual water-security challenges.

Unlike many major global cities that grew up astride rivers and other freshwater systems, Johannesburg boomed at the end of the 19th century because of its proximity to gold mines, not water. The city’s water comes from the Vaal Dam, which is about 75 kilometers (46 miles) from Johannesburg and 300 meters (about 1,000 feet) in altitude lower than the city.

That means the city depends not only on whether there’s water in the dam, but also whether it can be reliably pumped to the city’s approximately 5.8 million residents. That’s far from a given: At various times in the past year, the dam’s water level has fallen, pumps have broken down and electrical outages have disabled the pumps .

That has left city officials with little choice but to grapple with whether, and how, to pad supplies by cleaning up the Jukskei.

“If we need to mitigate the future, we need to be able to harvest our own waters from the rivers,” said Stanley Itshegetseng, deputy director of the City of Johannesburg’s office for Environment and Infrastructure Services.

That’s easier said than done. Although the Jukskei has posed health hazards for decades, the city had little interest in a clean-up because officials, like those in many other municipalities, “believe there are more important matters to deal with,” said Stuart Dunsmore, a consultant who advises cities on water management and river health.

“People within the municipality are interested in looking at it for the first time in a long time,” said Dunsmore, whose Fourth Element Consulting provides advice on surface water management, recovery and rehabilitation.

The Jukskei empties into larger rivers that ultimately reach the Indian Ocean in Mozambique. For the city of Johannesburg, the intense clean-up challenges lie along the first several miles.

The Jukskei emerges from underground at the corner of Queen Street and Sports Avenue, a few blocks from South Africa’s historic Ellis Park rugby stadium. It rolls through concrete culverts between dense urban blocks and abandoned inner-city buildings, occasionally widening to greener wasteland areas with invasive plant species and refuse.

A few miles after leaving the city center, it passes through the township of Alexandra in Northeast Johannesburg. Alexandra was founded in 1912 as one of few urban areas where Black people could own land under a freehold title, and its population has since grown to nearly 400,000, more than five times what the city has estimated the area’s infrastructure can bear.

People build shacks and other informal housing along the banks, contributing just some of the sewage that makes its way into the river. Storms and flooding here have resulted in lost homes and lives.

Those conditions helps explain the tally of items that one non-governmental organization, Water for the Future, has documented in the river: TVs, mattresses, guns, dead dogs. Levels of E.-coli are dangerously high.

At the City of Johannesburg’s water quality test site, which is within a few blocks of the source, E.-coli levels of more than 2 million plaque-forming units (PFU) have been documented per 100ml of water, exceeding by thousands of times or more international norms for fresh or drinking water.

Johannesburg’s water vulnerability was driven home by events in Cape Town in 2018. Severe drought brought the city close to a so-called Day Zero, when it would be forced to switch off the taps and haul water to residents by truck.

Traveling to fill up tanks or buckets isn’t unheard of in Africa, but on that scale it would have been unprecedented. The city was able to avoid Day Zero through tight restrictions on people and farms and the use of desalinated seawater, halving water use until the rains came back.

Johannesburg weathered a smaller scare in September 2020, when water levels in the Vaal Dam fell to less than 40% capacity before rebounding. There are other vulnerabilities in the system that transports that water to Johannesburg.

Power shortages are common across the country, and a power failure at a treatment plant near the dam caused half of Johannesburg to lose water at the end of May. Additional power outages at a pumping station and vandalism to a supply line caused further delays in restoring water supplies, according to city provider Johannesburg Water.

Johannesburg Water said shortages this year have led it to restrict water coming from its reservoirs to city users by 20% to 45%.

Asked for comment on recent power outages, Eskom, the nation’s energy provider, referred to a press statement that attributed losses to infrastructure failure caused by people stealing electricity.

The confluence of challenges may be unique to Johannesburg, but facing potential water shortages isn’t. Population growth, unsustainable water management and deteriorating infrastructure can all contribute to water shortages, according to UNICEF, which notes that one in four cities across the globe are water stressed. It identifies Tokyo, New Delhi, Mexico City and Shangahi as the most affected.

The Jukskei River won’t fulfill Johannesburg’s water needs by itself, even in the best scenario. According to Itshegetseng of the city’s environment and infrastructure office, if the river can be cleaned up, its catchments could service about one-quarter of the households in Gauteng Province, which encompasses Johannesburg as well as Pretoria.

That water would require further treatment to be drinkable, according to Dunsmore, the water consultant. Though the practicality of harvesting water from the Jukskei may be questioned, the volume of it is significant and should be managed, even if the main beneficiaries are downstream from Johannesburg, he added.

Education will play a key role, particularly among residents of informal shacks in Alexandra, Itshegetseng said. Previous efforts to move people from the riverside were unsuccessful and have been abandoned. Now, the city is working to communicate the importance of water health and hygiene, and it carried out a door-by-door education campaign in the area earlier this year.

Individuals have taken it upon themselves set up community bins to discourage dumping, Itshegetseng said, adding that the city wants to formalize relations with these individuals. The city is also spending R90 million ($6.3 million) to upgrade the area’s water infrastructure to mitigate current problems with sewage seeping problem. Completion of the new sewer line is expected by the end of the year.

Non-governmental groups, too, are looking for ways to support a clean-up, including Victoria Yards, an inner city development consisting of urban famers, artists and makers of artisanal wares. Groups in wealthier suburbs have sponsored clean-up days with local officials and volunteers.

The NGO Water for the Future — which drew seed capital from a restaurant chain, Nando’s— is working primarily to clean the river at its source.

That includes ongoing efforts to clear invasive plant species, bolster the river’s green corridor and gather scientific data on the river, including its flow rate. The group also aims to improve conditions for communities living next to the Jukskei in the inner city.

Johannesburg’s government has been “really supportive” of those projects, according to Water for the Future co-founder Romy Stander. However, funding for any fixing the city’s whole water situation has been tight. Johannesburg Water said that it lacks the funding for a backlog of infrastructure renewal projects that it places at R20.4 billion ($1.4 billion), and it says upgrade and renewal projects for the coming years are also underfunded.

Given that financial picture, the city might be better placed, for now, to mount strategic interventions to clean up pollution on urban riverbanks, according to Dunsmore. Such efforts have been mounted to the east of Johannesburg.

The neighboring Ekurhuleni authority has effectively created wetlands in the lower reaches of the Kaalspruit, another polluted and degraded stream by building a constructed wetland system — an engineered sequence of water bodies with vegetation designed to break down waste materials and remove pollutants, metals and bacteria, as a natural wetland would.

That sort of intervention wouldn’t clean the river totally, but could make the water suitable for a level of aquatic habitat, irrigation and potentially even low-contact recreation, Dunsmore said — provided space could be found for such a project along the banks of the Jukskei, which is crowded at many points.

It would be a further step, through purification and treatment, for any water to be usable by Johannesburg’s residents. Even so, Itshegetseng of the city’s infrastructure office insists that having a functioning river that can assist the city’s water needs is “not a pipe dream.”

Updated: 8-22-2021

As The Colorado River Dries Up, Phoenix Will Have To Survive On Less Water

The first drop in supply to the Central Arizona Project was announced last week. It won’t be the last.

The state of Arizona has been in drought since 1994. In that time, its population has almost doubled to 7.2 million people as of 2020, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. The majority of that growth has been in Maricopa, Pima, and Pinal counties, which cover the area around and between Arizona’s two largest cities Phoenix and Tucson.

Both cities — along with native tribes, farmers, and municipal and industrial users — draw a substantial portion of their water from the Central Arizona Project, a system of canals and aqueducts that carries water from the Colorado River, more than 300 miles to the northwest. The canal cuts through areas like suburban Scottsdale and winds through Arizonan countryside. In all, roughly 40 million people from California to Wyoming to Mexico depend on the water for their lives and livelihoods.

And it’s starting to run dry.

Last week, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation made official the crisis at Lake Mead, a reservoir formed by the Hoover Dam and one of the most visible signs of the Colorado River’s decline. The water level in the lake now sits about 1,068 feet above sea level, close to 200 feet below its typical level. With the announcement came cuts to CAP’s water supply. Early next year, supply will drop 30%.