Recession Gives Rise To Hand-Me-Down Inc. And Sneakerheads (#GotBitcoin)

The garage sale is becoming big business as The RealReal and other upstarts feast on the emerging appeal of secondhand clothes, shoes and accessories. Recession Gives Rise To Hand-Me-Down Inc. And Sneakerheads (#GotBitcoin)

Thrift Shopping Is Going Mainstream

It used to be that shopping for secondhand goods meant sifting through piles of clothes and “Everything $1” bins at the local Goodwill or a neighbor’s garage sale. For many, it meant scrolling through postings on one of the first online marketplaces, eBay Inc.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=whzqN-hJvD8&list=PLU1KxUVqGmaMnf7wmTSbphX2B2Z93uGtd

“Following the recession, there was a mind-set shift when it came to acquiring used goods,” said Oliver Chen, an analyst tracking retail trends at Cowen & Co. “Now, it’s considered a smart bargain. Being fashionable is about getting value for your dollar.”

For many consumers, the opposite was true just over a decade ago. Jessie Char, 32 years old, said shopping at thrift stores wasn’t cool when she was growing up. “It was the Abercrombie & Fitch era,” said Ms. Char, an event planner in San Francisco. “Vintage clothes were frowned upon by the popular kids.”

Today, about half of Ms. Char’s wardrobe is second hand. She said she scours a new crop of websites that are making it easier than ever for people to buy and sell used merchandise such as The RealReal Inc., Poshmark Inc. and thredUP Inc. as well as thrift stores such as Crossroads Trading Co., with about 37 locations, for bargains.

She recently bought a Prada Cahier belt bag for $945 on The RealReal. A similar version of the bag is currently selling at Neiman Marcus for $1,790. Neiman Marcus Group Ltd. made its own foray into the market for what it calls “preloved” handbags and accessories this year when it took a minority stake in Fashionphile LLC.

The RealReal, which resells luxury apparel, shoes, handbags and jewelry, went public in June and now commands a market value of nearly $1.3 billion, larger than that of Abercrombie & Fitch Co. It expects to sell nearly $1 billion of goods this year, though its net loss widened in the most recent quarter.

ThredUP and Poshmark offer used goods from a wider array of brands, including J.Crew and Gucci. Poshmark is planning an initial public offering as soon as this fall, people familiar with the situation said. StockX is the place where sneakerheads go for their latest fix of vintage athletic shoes and streetwear.

These companies are borrowing a page from the car industry, which turned the process of buying secondhand automobiles from agonizing to relatively painless by offering leases on preowned vehicles. The dealers do all the vetting, taking out the uncertainty much the way The RealReal and other secondhand marketplaces authenticate products they sell.

As these sites soar in popularity, it remains to be seen whether they can make money from reselling fashionable clothes and other items. The cost of cleaning and vetting goods is considerable, as is sourcing, industry executives said. Rather than products flowing from overseas factories in large batches, they are coming from people’s closets, often one at a time.

And the secondary market isn’t immune to the pressures facing stores that sell new goods. Discounting by department stores depressed prices of secondhand goods sold by The RealReal in its most recent quarter, according to Julie Wainwright, The RealReal’s chief executive.

The sale of secondhand goods—or recommerce—accounts for a tiny fraction of the $3.8 trillion in U.S. retail sales, but it is growing fast. Sales of secondhand goods are expected to more than double to $51 billion by 2023, up from $24 billion last year, according to GlobalData PLC, which prepared the research for thredUP.

Fifty-six million U.S. women bought secondhand products in 2018, up from 44 million who did so in 2017, according to the report. Shoppers ages 18 to 37 are driving the shift. A third of Generation Z and more than a quarter of millennials will make secondhand purchases this year, the report predicts.

It isn’t just women who are getting into the act. Most of the resale sites also buy and sell used men’s clothing in addition to the plethora of men’s suit- and tuxedo-rental services that have popped up.

Rent The Runway and other rental business are benefiting from similar changes in consumer behavior, including a desire for newness on the part of young selfie-posing shoppers who don’t want to be seen in the same outfit twice. Consumers on average buy 60% more clothing today than they did 15 years ago, but keep the items only half as long, according to McKinsey & Co.

That has resulted in more waste. Nearly 60% of the more than 100 billion garments produced annually end up in incinerators or landfills within years of being made, McKinsey estimates. The production of one kilogram of fabric generates an average of 23 kilograms of greenhouse gases, the consulting firm says, making the fashion industry a big polluter.

“I used to buy the $15 fast-fashion shirt that fell apart after I washed it a few times, until I realized how wasteful that was,” said Jessica Fletcher, a 25-year-old project engineer, who lives in St. Louis, Mo. She started buying used clothes after she graduated from college. “It was a good way to get better quality at a quarter of the cost.”

Shoppers at the high end have become more bargain conscious, too, particularly as prices for luxury goods have soared over the past 15 years, placing many items out of reach, even for the affluent. McKinsey estimates that prices of fine watches and jewelry have nearly doubled since 2005, while the price of Louis Vuitton’s Speedy 30 handbag has increased 19% a year since 2016.

“I can afford to buy new clothes, but I like buying them used, because it lets me try different styles without spending a lot of money,” said Kuromi Hendrix, 28. Ms. Hendrix, who lives in Boston and works as an IT specialist, recently scored a Tadashi skirt for $12.99 on thredUP. The resale site estimates the original price was around $107.

As more shoppers buy used products, they are spending less at traditional chains, from fast-fashion retailers to department stores. Some established players are fighting back by launching or expanding their own resale programs, including Macy’s Inc. and Levi Strauss & Co.

GlobalData predicts that sales of secondhand merchandise will exceed those of fast fashion within a decade. And at the high end, used goods will account for 9% of the global luxury market by 2021, up from 7% last year, according to Boston Consulting Group.

The technology that created the boom in online shopping has turned the local thrift store into a mainstream phenomenon by providing consumers with more confidence that their purchases are authentic and making it easier for them to browse at times that better fit their schedules.

“You can shop for secondhand goods in a way that you never could before,” said James Reinhart, thredUP’s founder and chief executive.

When Hannah Stephenson, a 36-year-old writer, needed to update her wardrobe for a new job, she didn’t have time to sift through piles of clothes at her local Goodwill. Instead, she browsed thredUP’s website in the evening while she lounged on her couch.

“I’d rather buy second hand than go to a mall, because you can find more unique items,” said Ms. Stephenson, who lives in Columbus, Ohio.

Buying is only part of the equation. A growing number of shoppers also sell their clothes and accessories on secondhand websites and in thrift shops, creating a virtuous circle that clears out their closets so they can buy more.

According to a survey of 12,000 luxury consumers by Boston Consulting Group, one-third of respondents said they sold items to empty their wardrobe and finance new purchases. At The RealReal, 53% of consignors were also buyers as of March, according to securities filings.

“This is a trend that is not going away,” said Sarah Willersdorf, a Boston Consulting Group partner.

On Second Thought, Traditional Retailers Make Room for Used Clothes

Venerable names like Macy’s, J.C. Penney and Stage Stores embrace thrifting in push to jump-start sales and lure younger, environmentally conscious shoppers.

Some of the country’s biggest retail names are following online startups into the cult of thrifting, casting aside long-held fears that selling secondhand goods would cannibalize the market for new goods.

Macy’s Inc. and J.C. Penney Co. this past week unveiled partnerships with resale marketplace thredUp Inc. to sell used clothes and accessories in some of their stores. Outdoor brand Patagonia plans to open a temporary store in Boulder, Colo., this fall dedicated to selling pre-owned goods, its first such location.

Thrifting is gaining traction as shoppers have grown more bargain conscious and concerned about the environmental impact of fashion, particularly the throwaway clothing model popularized by fast-fashion chains.

“We looked deeply at Generation Z consumers, and recommerce came up over and over again,” Macy’s Chief Executive Jeff Gennette said in an interview, referring to the burgeoning resale market. “It’s not a downside that something has been preowned.”

Thorsten Weber, chief merchandising officer of Stage Stores Inc., which has thredUp shops in about 45 of its department stores, said traditional retailers are just beginning to wake up to the impact of resale. “Just like off price became a disrupter, resale will be a disrupter,” he said. “It will be a force in the industry.”

Other chains, including Bloomingdale’s, which is owned by Macy’s, Urban Outfitters Inc. and Ann Taylor, are taking a slightly different approach by launching services that let shoppers rent clothes instead of buying them. Customers can even rent home décor at West Elm, which has partnered with Rent The Runway Inc. for the program.

“Customers are looking at dead inventory in their closets,” Mr. Gennette said. “They may wear an item once or twice, but why do they have to own it?” And if they can save a garment from going into a landfill, so much the better, he added.

For traditional retailers, many of whom are struggling with sluggish sales as shoppers buy more online, resale and rental is a way to bring younger customers in the door.

Phil Graves, Patagonia’s director of corporate development, said shoppers who buy used clothes from the outdoor brand are typically a decade younger than those who purchase new gear from the chain.

Patagonia began selling used goods in 2017 under its Worn Wear label, although it has provided repairs of existing gear since the 1970s. Shoppers can send back used items by mail or drop them off at one of the retailer’s 34 U.S. stores. In return, they get a credit of up to $100 that they can use on future purchases.

This fall Patagonia will launch Recrafted, a line made from old clothing and other gear that couldn’t be resold in their current state. The items are refashioned into new garments, including jackets, bags and vests.

Resale is still a small business for most traditional retailers, but it is growing fast. At Eileen Fisher Inc., which pioneered resale a decade ago, it accounts for about 1% of sales. Sales of Levi Strauss & Co.’s authorized vintage garments have tripled since the line was introduced in 2017, but are still a tiny fraction of overall sales, said Jonathan Cheung, Levi’s senior vice president for design innovation.

Many traditional chains, particularly luxury brands, continue to sit on the sidelines, worried that a booming secondary market will depress demand for new goods.

“If you’ve sold new cars your whole life and all of a sudden you’re going to start selling used cars, the immediate fear is, what if all the customers just buy used cars?” said Andy Ruben, the CEO of Yerdle Recommerce, which operates resale programs for brands. “The reality is that people who want used items are going to find them anyway.”

That is what has been happening with Michael Kors handbags, said John Idol, chief executive of parent company Capri Holdings Ltd.

“There’s no question that resell in North America impacted the Michael Kors accessories business,” Mr. Idol recently told analysts. “There is a substantial amount of product that is resold on numerous websites. We don’t sell to those companies directly. But you can find our product on there.”

Nevertheless, Mr. Idol said Michael Kors isn’t rushing to launch a resale business of its own. “We’ll be very slow” in evaluating these new opportunities, he said.

One issue keeping traditional retailers at bay is sourcing. Old-school chains are set up to sell thousands of the same item, not thousands of one-of-a-kind pieces that need to be vetted and cleaned.

“It’s not that easy to find the goods,” Levi’s Mr. Cheung said.

Mr. Cheung said employees scour thrift shops, yard sales, websites and vintage dealers for jeans from the 1980s and 1990s that Levi resells in its eight flagship stores.

“There has been a change in the perception of vintage goods,” Mr. Cheung continued. “When I was growing up, they signified that you couldn’t afford new clothes. Now, it’s a status symbol. It says you’ve made an intelligent and sustainable choice.”

As a fast-fashion retailer and pioneer of the throwaway-clothing trend, H&M isn’t usually top of mind when it comes to sustainability. But the Swedish chain has been working to change that. In 2013, Hennes & Mauritz AB launched a program that lets shoppers drop off used clothes at H&M’s nearly 4,500 stores world-wide.

The items, which can be from any brand, are collected by a recycling company. Roughly 60% are resold through local thrift shops and markets; the rest are turned into other products or fibers for new garments.

Eileen Fisher was one of the first traditional brands to dive into resale in 2009 when it launched a program for employees. It eventually opened it to the public, and resale took off in 2013, when the company posted signs in its stores that read, “We’d like our clothes back, thanks very much,” said Cynthia Power, director of Renew, the brand’s resale and recycle program.

Today, the company sells used clothes in a handful of its 67 Eileen Fisher stores, as well as in two free-standing Renew stores and on its website. Used clothes typically cost about a quarter of the price of new items, Ms. Power said.

Ms. Power said selling used clothes hasn’t hurt sales of new clothes. “It gives customers another reason to come to the store,” she said. “It’s an add-on purchase.”

Updated: 2-28-2021

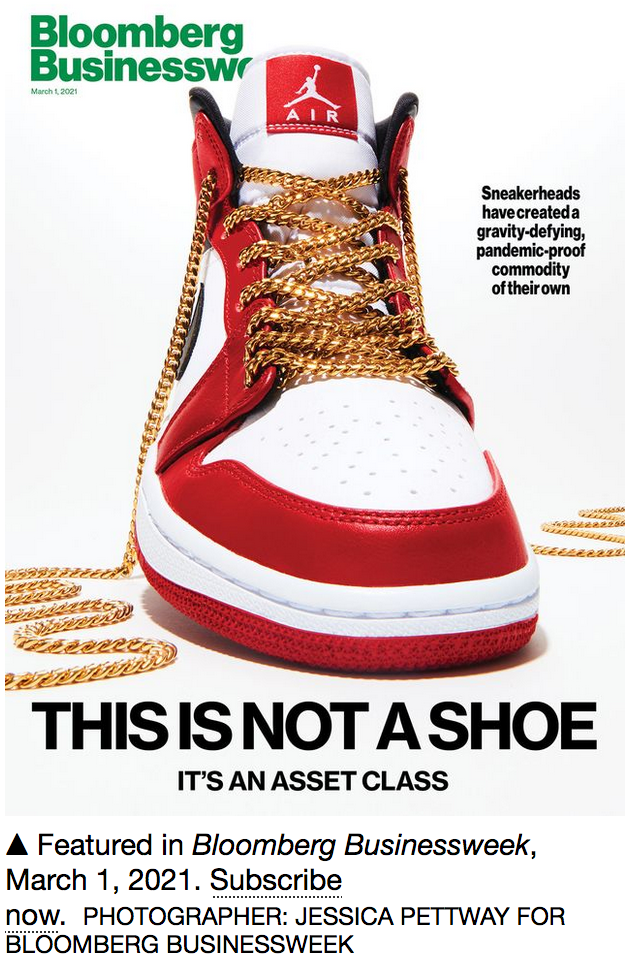

Sneakerheads Have Turned Jordans And Yeezys Into A Bona Fide Asset Class

When the pandemic presented a buy-low opportunity, one college dropout hit the road and filled his truck with $200,000 worth of kicks.

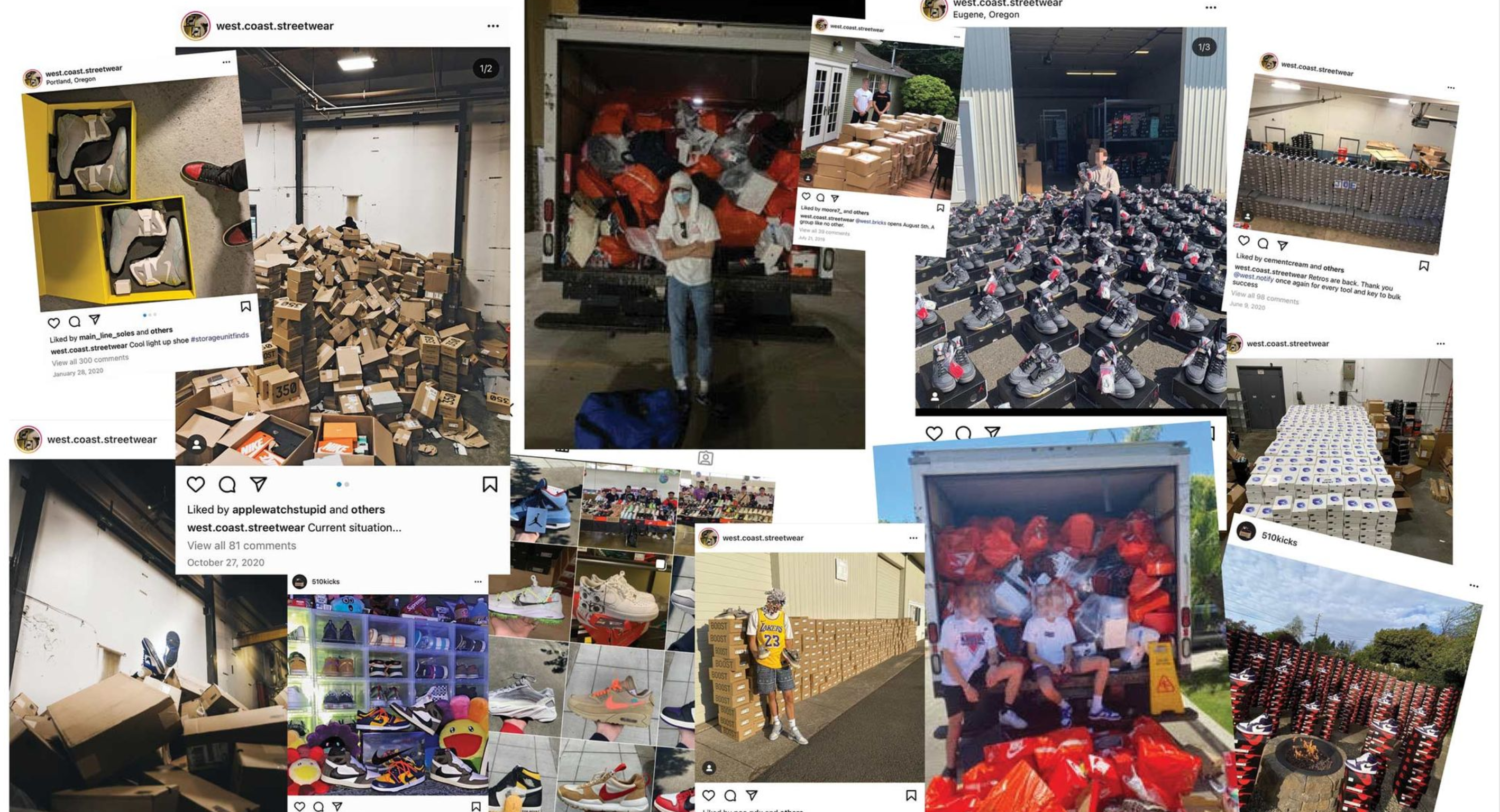

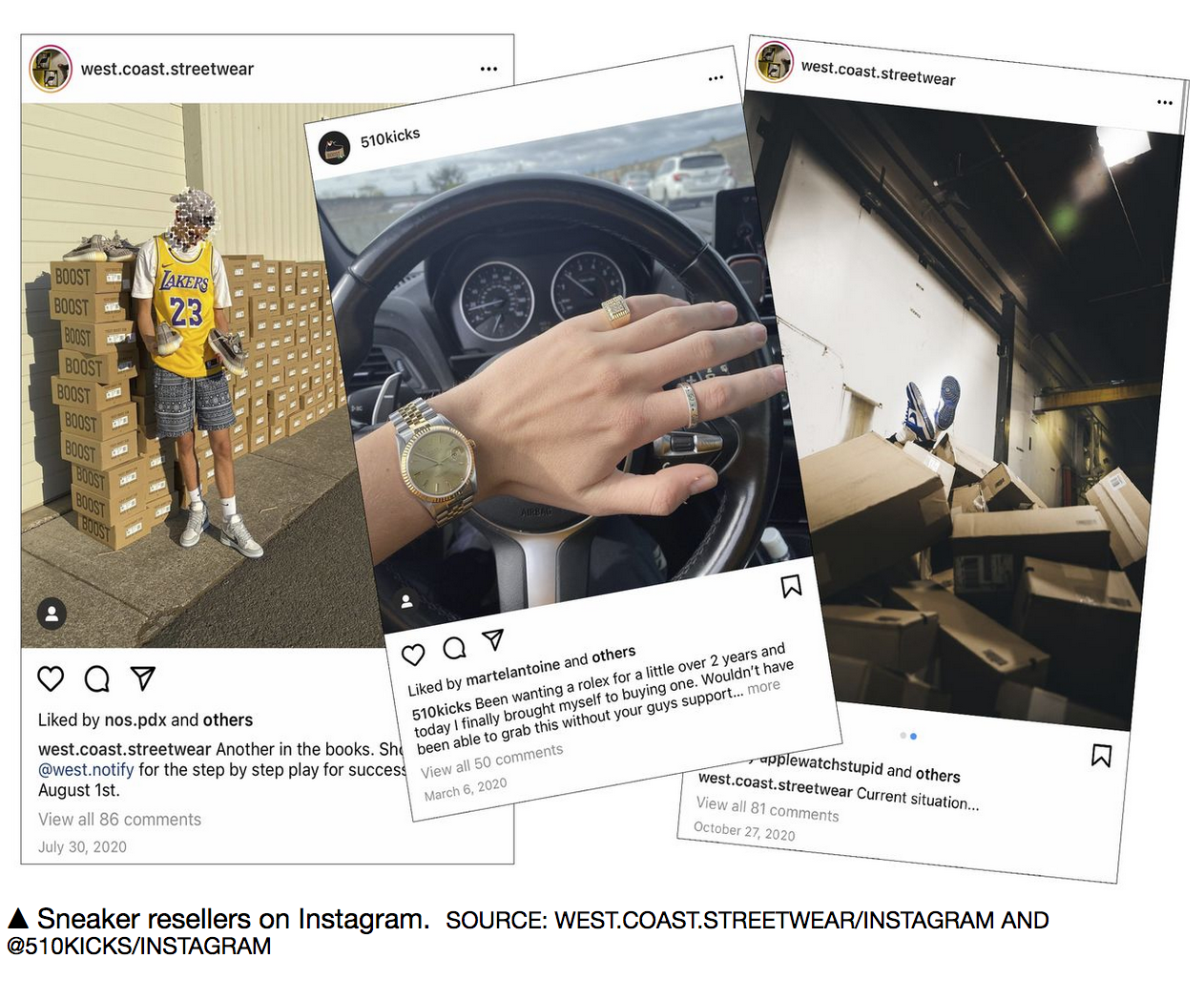

Last July 30, Joe Hebert woke up early and drove to a small warehouse he’d leased in Eugene, Ore., the track-obsessed college town where Nike Inc. was born. He was expecting an important delivery: 600 pairs of Yeezy Boost 350 Zyon sneakers.

Released by Adidas 12 days earlier, they’d sold out within hours and now commanded more than $100 above retail on the secondary market. Many sneakerheads would have felt lucky to snag a single pair of one of the world’s most sought-after styles.

Adidas AG produces just 40,000 pairs of each Yeezy release, which are priced at $220 retail and sold through its Yeezy Supply website using a digital lottery.

When his shoes arrived, the 19-year-old, who’s known to his customers as West Coast Joe, stacked the hundreds of boxes like poker chips on the sun-drenched pavement outside the warehouse. “It’s easy to get a lot of this style, and they pretty much always sell,” he said, in one of a series of conversations we had last year about his business.

What Hebert meant by “easy” was this: The day these Yeezys were released, he’d awoken at 3 a.m., signed on to the messaging platform Discord, and rousted 15 members of his “cook group,” a term sneaker resellers use to describe their allies in arbitrage.

When the shoes went on sale an hour later, Hebert’s team swarmed the Yeezy Supply website using specialized computer programs such as Cybersole, Kodai, and GaneshBot, each prepped with Hebert’s credit card information and capable of gaming a system meant to limit purchases to one pair per customer. By 6 a.m. the shoes were sold out, and Hebert’s bots had rung up $132,000 on his American Express.

His company, West Coast Streetwear, resold the shoes in almost as little time as it had taken to buy them, clearing $20,000 in profit. “Anything that’s releasing that I know I can make a guaranteed buck on, I’m gonna go full into,” Hebert said. “That’s just my style.”

Flipping sneakers has been a viable business proposition for decades. The demand side emerged as far back as 1985, when Nike dropped the Air Jordan 1, a culture-shifting sneaker that sold faster than the company could manufacture it. The supply side followed soon after, when some retailers began selling the few pairs they could get for more than Nike’s $64.95 suggested retail price.

A year later, the company doubled down, limiting the initial release of the Air Jordan 2 to just 30 stores in 19 cities and adding $40 to the price. The Air Jordan 3, which marked the debut of Tinker Hatfield’s iconic “Jumpman” logo, was so popular that Nike has reissued it countless times without ever really satisfying demand.

The advent of EBay in the mid-1990s brought nonretail sellers into the game, and the market only grew from there. EBay’s annual sneaker trade reached $388 million in 2014, and analysts pegged the broader resale market at $1 billion. Last July, Cowen Inc. estimated the latter figure had grown to $2 billion in North America alone.

The sneaker boom has created opportunities for a new generation of speculator. Hebert and other young resellers are the first to treat footwear as a bona fide asset class, products as worthy of informed valuation and investment as any other commodity. The sneaker market, for them, is a lot like playing the market.

In the hours after siphoning up stock from retailers, they essentially sell short-term futures based on street sentiment. By the time prices plateau, ultra-rare shoes such as the Air Jordan 1 OG Dior—a collaboration between Nike and the Parisian fashion house that was limited to 8,500 pairs—have become “grails” worth $10,000 or more, while more attainable stock has been bundled into tranches and sold on to other resellers at a bulk discount.

Like their new fellow travelers, the day traders of Reddit, sneaker resellers have used community and technology to exploit a system that wasn’t quite ready for them. But unlike the GameStop crowd, they aren’t really making a point along the way; they’re just making a profit.

For these traders, the pandemic offered yet another opportunity. Cowen’s report pointed out that some of the fastest growth in the secondary market came in the months after the Covid-19 crisis began, driven in part by steep discounts from shoe companies that faced double-digit sales declines. “Foot Locker was panicking, and a lot of smaller boutiques were panicking, doing like 50%-off sales,” Hebert said. “Just trying to dump all that stuff.”

Shoppers were avoiding stores and flocking instead to e-commerce platforms such as StockX, where young entrepreneurs like him were offering “deadstock.” The term, once used by retailers to describe unsold, discontinued items gathering dust on store shelves, has been adopted by resellers, who emphasize that the styles are no longer made and the items are still in their original packaging.

Jesse Einhorn, senior economist at StockX, says that May and June were the platform’s two biggest months since its February 2016 launch. It likely got a bump, too, he notes, from ESPN and Netflix’s airing, starting in mid-April, of The Last Dance, a 10-part chronicle of Michael Jordan’s final season with the Chicago Bulls, which drew many older buyers into the market for the first time.

That was also a breakout time for West Coast Streetwear. “I remember the night the stimulus checks hit. My sales tripled,” Hebert said. “In May we did $600,000.” This would have vaulted him into the upper echelons of sneaker resellers at StockX, according to a company spokesperson, who says those are the numbers of “a top-tier power seller.” An opportunity was clearly presenting itself.

The teenager had a problem, though: Supply chain issues were starting to translate into fewer shipments to wholesalers. The shoes he needed were still out there in stores, their prices slashed, but if he wanted to buy the dip, he’d have to get creative.

Hebert’s reselling career started in high school, when he noticed that some Supreme T-shirts he owned were going online for two or three times what he’d paid. The margin traced at least partly to the 2016 launch of StockX, where limited-edition releases from Supreme, Off-White, Palace, and other streetwear brands were finding new life.

The resale site was giving Hebert’s generation its own EBay—a “stock market of things” where transactions were public and items could be valued accordingly. “If you throw out everything else, StockX is a price guide,” says co-founder Josh Luber. “It’s a price guide that moves in real time, looking at supply and demand to understand the value of any particular shoe.”

When Hebert began selling shoes there in 2017, StockX had gone from processing hundreds of transactions per day to tens of thousands. Demand was surging for deadstock sneakers, in part due to the rising popularity of the streetwear brands, which supplemented a booming trade in T-shirts and hoodies with limited-edition shoe collaborations with traditional footwear makers. But it was also thanks to an industry-shifting move by Nike.

The shoe giant’s “Consumer Direct Offense,” announced that year, was focused on driving sales away from brick-and-mortar partners such as Foot Locker Inc. and toward its own stores, mobile apps, and websites.

By the end of the fiscal year ended May 31, 2019, it was clear the move was paying off: Digital sales were up more than a third, and direct-to-consumer sales had climbed to $11.8 billion, almost double what they’d been four years before. (This shift has lately helped insulate Nike from the effects of pandemic-related store closures, according to spokesperson Sandra Carreon-John. “The pandemic has been sort of a stress test that proves our strategy is working,” she says.)

The move toward online sales was a boon for resellers like Hebert, who could use bots to target the most sought-after sneakers and acquire them in far greater quantities than customers could in the days of lining up outside stores. He and his peers operated instead in digital spaces such as Nike’s SNKRS app, which the company made the first place—and sometimes the only place—people could get certain limited-edition shoes.

The app effectively gamified Nike’s engineered-scarcity model, making the experience of buying shoes like spinning a digital roulette wheel. It also turned its most avid customers into digital advertisers for the brand: After a big drop, winners and losers of the app lottery for the latest Jordan or Nike SB Dunk reissue would celebrate or complain on social media, fueling the hype cycle.

The potential to get rich quickly, in an informal setting with little oversight, drew a new breed of extremely online Gen Z trader.

Most were White men, according to Adena Jones, chief executive officer and one of two Black co-founders of Another Lane, which launched its own digital marketplace for kicks last April. Jones and her husband, Chad, raised $160,000 to start their business by selling off shoes from their own collection.

“Part of the reason,” she says, “was to have a voice in this culture that we started.” She’d seen sneaker reselling become highly transactional—“like buying wheat or oil,” in contrast with the approach of her husband, “who has been to the weddings of people he’s sold sneakers to.”

Chad marvels at how quickly things changed: “For 30 years I was boots on the ground, camping out in front of shoe stores. Then all of the sudden this middleman emerged.”

The ultimate middleman was StockX, which came about in part as a stabilizing force. In 2014, when Luber was still an IBM consultant with a sneaker blog, he told the Financial Times that the secondary market for sneakers was “more similar to the illegal drug trade” than a stock exchange. Two years later he launched StockX with an eye to changing that.

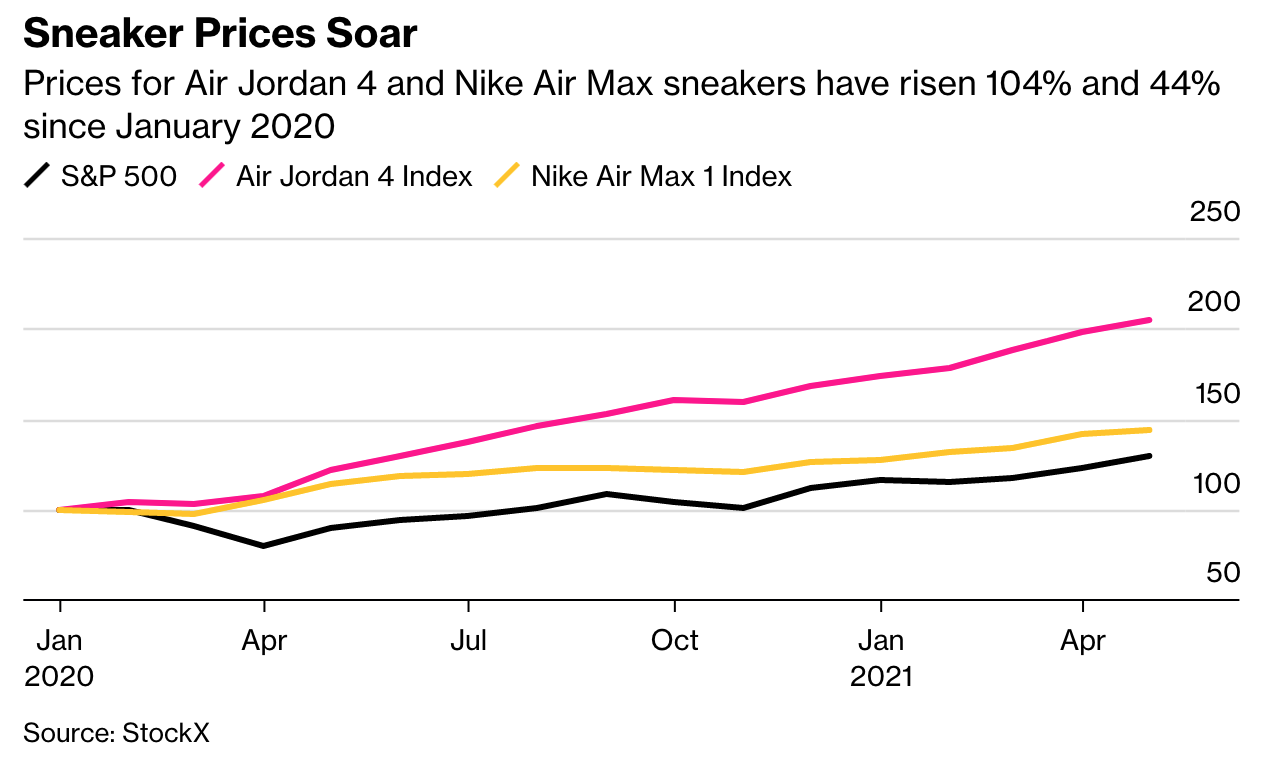

He’s succeeded well enough that Einhorn, the senior economist, created a hypothetical index fund of 500 sneakers that he found outperformed the S&P 500 by a few percentage points. “The index of the top 500 increased about 30% since 2018, and about 75% of the sneakers in that portfolio gained resale value,” he says.

As with most assets, some vetting is required. Sellers ship items to a StockX processing center, where they’re authenticated before being shipped on to the buyer. Items are returned to the seller if they’re damaged or used or have missing or substandard packaging. A rigorous inspection helps weed out counterfeits. Other potential provenance issues aren’t accounted for—StockX doesn’t track how sneakers end up on its platform, for example.

Hebert’s biggest score as a young shoe speculator came in January 2020. He’d just dropped out of the University of Oregon midway through his second term and moved back to Portland.

There, he said, he tracked down a man he’d heard about who’d stumbled across an exceptional find in an abandoned storage unit: four pairs of Nike Mags, the futuristic self-lacing shoes worn by Michael J. Fox in 1989’s Back to the Future Part II. Hebert described finding the man and paying $22,000 for the collection, then flipping it for $42,000.

The proceeds went toward a play for a bigger and potentially more lucrative slice of the market: bricks. These shoes, whose nickname evokes both a badly missed shot in basketball and the way they cling, as if weighed down, to store shelves, tend to be less loved than Mags, but they’re much easier to get hold of.

In today’s $60 billion global sneaker market, some releases inevitably fail to sell as projected. Whether the cause is overmanufacturing, underpromotion, or a failure to anticipate trends, the result tends to be the same: a markdown. When that happens, resellers have their bots snap them up in bulk, often before ordinary consumers notice they’re on sale.

In many cases, they’ll use discount codes bought via social media, earning an additional 10% to 40% off orders worth tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars. On the secondary market, the shoes can reliably earn from 10% to 30% more than the sale price—leading some bricks, paradoxically, to end up reselling for their full retail price or more.

“I’ll give you an example,” Hebert told me. “The Nike VaporMax is considered a brick shoe, because it’s not a hyped Jordan that resells for 50 or a hundred bucks over retail. It usually gets discounted.”

But someone, somewhere always seems to want a pair, he said. And since resellers don’t need to worry about clearing out seasonal stock or meeting quarterly sales targets, they can sell the shoe whenever it’s profitable to do so.

“I’m not dealing with 100%, double-my-money margins usually,” Hebert said. “It’s just a pretty calm 10 to 20 and then moving product as fast as I can”

Before the pandemic-era sneaker surge, Hebert was selling enough bricks to clear $200,000 in revenue most months. They’re a volume business, though, so he’d had to start renting the warehouse in Eugene, which is big enough to accommodate two fire engines. The space became both a hangout spot and the setting for an endless well of Instagram posts designed to make sneakerheads drool.

Eventually, Hebert realized that his growing Instagram following included hundreds of entrepreneurial teens hoping to emulate his success, which led him to a new revenue stream. For $250 per month, they could subscribe to a Discord group, West Bricks, where he shared information on upcoming online releases, such as what sneakers would be discounted, when and where the sale would begin, and how many the retailer would have.

As of late 2020, Hebert counted about 450 subscribers. One of the first to sign up was a 17-year-old Californian, who told me West Bricks had made him more than six figures. He described his primary market as middlemen who would resell the shoes in China—where customers offered top dollar to avoid buying counterfeits—and who would sometimes pay him in rubber-banded stacks of cash that he’d later flaunt on Instagram.

Hebert’s competitors have access to the same bot software and StockX-borne real-time market research as he does. What they don’t have, according to some of his subscribers, is consistent, sound analysis of what shoes to buy, how to get them, and, crucially, how long resellers might expect demand to persist. Hebert declined to talk about his sources of information, but he did say he was lucky to have grown up in Portland, where both Nike and Adidas base their U.S. operations.

“If you know the right people here, this is the city to sell shoes,” he said. The right people “can give you access to stuff that, like, a normal person would not have access to.”

When the Covid boom got under way last year, Hebert found himself confronting the unexpected problem of having more customers than ever but no way of getting his hands on more kicks. For inspiration, he looked to Nike co-founder Phil Knight, who got his start selling another company’s shoes out of the trunk of his car. Like Knight, Hebert would hit the road.

The stock he needed was out there, he knew, languishing in backrooms at the retail outlets fearful American shoppers were avoiding. So he grabbed a pal, bought a 17-foot Ford E-350 box truck at auction, and embarked on a 25-day, 10,000-mile brick hunt. Hebert’s traveling companion was Justin Taliaferro, a friend from high school. The trip “seemed like exactly what we needed to get out of the house during quarantine,” Taliaferro said when I spoke with him months later.

With a map of Nike outlets to guide them, the 19-year-olds headed east from Portland, traveling through Idaho, Utah, and Colorado, focusing on hot spots such as Salt Lake City and Denver, where Nike factory stores are more densely packed than in other metropolitan areas.

“We know that Nikes have the most variety in styles and the best discounts on their more select shoes,” Taliaferro said. Along the way, they dropped in on every Foot Locker, DTLR Villa, and Champs Sports outlet they came across, stopping occasionally at Adidas outlets as well.

Some of the best scores, according to Hebert, came from mom and pop stores, which didn’t have the kinds of restrictive purchase limits that outlet stores for larger brands sometimes place on certain shoes. “There’s kind of a stigma against resellers,” he said. “They even went at us harder now, because these Nike outlets weren’t getting any new inventory.” The mom and pops were more than happy to make dozens of sales at a time.

For the first two weeks, the pair saved money by stopping overnight at truck stops and Walmart parking lots, crashing in their vehicle’s cargo box on two thin sleeping pads and some pillows and blankets. When they reached Louisiana, the bugs and the heat forced them to seek out cheap motel rooms. By the time they escaped the U.S. humidity belt, they barely had enough room in the truck for shoes, let alone sleeping pads.

Back home in Portland, they lifted the steel door and a wall of orange Nike boxes spilled onto the pavement. Hebert had spent more than $200,000 on about 2,000 pairs of shoes, which he hoped would return a profit of around $50,000. “I’m not dealing with 100%, double-my-money margins usually,” he told me. “It’s just a pretty calm 10 to 20 and then moving product as fast as I can.”

After the trip, as supply chains grew less strained, Hebert started diversifying his approach, wholesaling some of his summer brick stock, along with some Jordans and Yeezys, to smaller retailers. He said he thought the West Coast Streetwear brand might be getting big enough to launch its own direct-to-consumer offensive, starting with its own web store. Bypassing StockX would mean fewer fees and fewer returns.

“If I ship them a shoe and the box has a damaged corner or something, they’ll go ahead and charge me 15% of the sale, and then they’ll charge me $14 to ship it back, which is like a double whammy,” Hebert said. “When I’m not working on a high margin it really hurts me, but they don’t do it for every sale, which is kinda weird. I still don’t know the formula, and I’ve been asking for it for a while.”

(A spokesperson for StockX says that if the company receives a damaged or defective product, it charges only the shipping fee. “In certain cases—typically when a product is determined to be inauthentic,” she adds, “we do then charge the seller a minimum of $15 or up to 15% of the transaction amount.”)

He was also taking steps to go beyond selling shoes—which I’d learned, quite by accident, ran in his blood. At one point in late June, after his trip, he’d phoned me, and the number was identified as belonging to Ann Hebert. I looked the name up and discovered there was an Ann Hebert who’d worked at Nike for 25 years and had recently been made its vice president and general manager for North America.

The press release announcing her promotion noted that she would be “instrumental in accelerating our Consumer Direct Offense”—the Nike initiative that had helped fuel the sneaker-resale boom. Hebert later sent me a statement for an American Express corporate card for WCS LLC, to demonstrate West Coast Streetwear’s revenue, and it was in Ann’s name.

When I asked Hebert about the connection later that year, he acknowledged that Ann was his mother and said that, while she’d inspired him as a businessperson, she was so high up at Nike as to be removed from what he does, and that he’d never received inside information such as discount codes from her.

He insisted, though, that she not be mentioned in the article and cut off contact not long after our conversation. (Ann Hebert didn’t reply to emailed questions; Carreon-John, the Nike spokesperson, says Ann disclosed relevant information about WCS LLC to Nike in 2018. “There was no violation of company policy, privileged information or conflicts of interest, nor is there any commercial affiliation between WCS LLC and Nike, including the direct buying or selling of Nike products,” she writes.)

Nike’s marketing and corporate culture are strong enough in Portland that most anyone there can steep in it; the children of company executives, no doubt even more so. But whatever the advantages to growing up with a silver swoosh in one’s mouth, Hebert’s hustle couldn’t be denied. Not to mention, as he pointed out during our last phone call, that he’d started out selling Supreme T-shirts. He also moved plenty of Adidas stock.

In the fall, he’d struck out for even less familiar terrain. When Sony launched its PlayStation 5 console in November, Hebert sensed a looming shortage of stock. “We botted Walmart and Target pretty hard,” he told me. “I ended up with 24 of them and made between $300 and $500 on each one.”

There’d been growing pains outside the family business, though. His bots had initially gobbled up hundreds of PS5 systems, but because he was working in unfamiliar territory he’d made mistakes that resulted in most of his orders getting canceled, leaving him with just the two dozen consoles. “Wish I had prepared more,” he said.

Updated: 3-21-2022

Nike Heads for Biggest Quarterly Drop Since 2008

* Stock Slumps 22% This Year With Inflation And Supply Concerns

* Company To Report Quarterly Earnings After Market Close Monday

In an industry pressured by soaring inflation, Nike Inc. is suffering more than most as its exposure to the fallout from the war in Ukraine and supply-chain issues put its shares on track for their worst quarter since 2008.

The stock is down 22% this year, double the pace of the 11% decline in the S&P 500 consumer discretionary index, as decades-high inflation hurts shoppers’ sentiment and wallets. The company will report fiscal third-quarter earnings after markets close on Monday.

Production shortfalls and transport delays in particular make for a “tough-to-predict” report, according to Morgan Stanley analyst Kimberly Greenberger. Even if the company delivers a beat and raise quarter, uncertainty around the drivers of underperformance in China, potential impacts from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and inventory levels could keep the stock range bound.

“It’s unlikely 3Q results resolve these lingering debates, delaying any material valuation re-rating to the 4Q earnings report (in June) or beyond,” Greenberger wrote in a note last week. Nike shares fell 0.8% on Monday.

BofA Securities analyst Lorraine Hutchinson recently lowered her earnings per share estimates for fiscal 2022 and 2023, citing exposure to Russia and eastern Europe as well as Covid-related volatility in China.

Still, analysts remain largely positive on Nike, which has 28 buy ratings, 7 holds and 1 sell, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Even though several analysts have trimmed their price targets ahead of earnings, the average analyst target still implies return potential of 29% for the next 12 months.

“We see a compelling buying opportunity for one of our favorite long-term growth stories,” Truist Securities analyst Beth Reed wrote in a note last week.

Updated: 4-2-2021

One Couple’s Fight To Stop The ‘Gentrification’ Of Sneaker Collecting

Another Lane’s membership-only platform emphasizes community over the relentless drive for profit.

Chad Jones first learned that sneakers are an asset class when his mother lost her job and they had bills to pay. It was 2001, and the college sophomore put his personal collection of shoes in his trunk to sell them to classmates or anyone else who wanted them. He made enough money to keep his car so he could stay in school. “Now, the rest of the world’s realizing that it’s a major resource as well,” says Jones.

His sneaker habit grew into a full-blown obsession that’s turned into a business with his chief executive officer and wife Adena. Working from their home in Fort Lee, N.J., the couple started resale site Another Lane in early 2020, right at the start of the coronavirus pandemic, and added a membership-only platform in December.

The business is starting to gain prominence among collectors by bringing a semblance of the personal touch back into a booming sector that’s lost its sense of community as kicks become commodities.

“You can sometimes no longer recognize the culture that you grew to know and love,” says Adena. “Sneakers are being treated like wheat and oil.”

Back when Chad was hawking from his trunk, sneaker flipping was already a proven way to make money, but it was mostly done through specialized shops, word-of-mouth, and EBay Inc. These days, the sneaker resale economy has gone fully corporate, and investors have injected millions in funding.

StockX LLC, a streetwear exchange that mimics a stock market, has plans to one day go public. Online reseller GOAT Group has raised nearly $300 million in venture capital funding to supercharge its growth, including an investment from Groupe Artemis, the controlling shareholder of Gucci owner Kering SA. Analysts at Cowen & Co. last year estimated that the sneaker and streetwear resale market has reached more than $2 billion in North America and is growing by 20% each year.

The proliferation of speculators in the industry has bred a cutthroat climate for sneakerheads to navigate. Specialized computer programs used by resellers make it hard for regular shoppers to buy shoes when they’re released online, and those with connections at stores use them to acquire product on the sly.

Lucrative operations to sell “deadstock”—a term to describe unworn styles still in their original packaging—and movement by the sneaker brands toward a model of limited-stock drops have made it difficult for regular shoppers to get their hands on, say, the latest Air Jordan 1s in Carolina blue, which instantly sold out at $170 retail, only to reappear on marketplaces for more than $300.

The Joneses aim to bring fairness back. They speak of the flipping game with exasperation, citing the lengths people go to hustle each other and make a buck. At the big marketplaces, sellers are anonymous—nothing more than an online listing.

“They want to do all the shady business behind the scenes,” says Chad. “We’re here. We want to shine a light on all of that.”

Another Lane prioritizes relationships between buyers and sellers in an effort to make sneaker purchases less transactional and more fun. It’s a membership-based community whose newbie sellers are vetted through an application and must provide references before they’re granted access.

Buyers need only to sign up and users are up 137% since the platform launched four months ago. The site is meant to connect both sides, offering one-on-one chats in which shoppers can ask if a shoe runs small in size, or if they might get a few dollars shaved off the price tag.

Frustration about the resale ecosystem erupted among sneakerheads in March when it was revealed that Joe Hebert, the 19-year-old son of a top Nike Inc executive, was operating a major resale enterprise, using his mother’s credit card. Ann Hebert, the head of Nike’s North America division, subsequently quit her job.

The backlash was serious enough to prompt Nike Chief Executive Officer John Donahoe to address concerns about the integrity of product releases at an all-hands meeting. He told his employees that consumers are questioning whether Nike can be trusted, according to Complex.

Those trust issues go back long before the Hebert saga, with counterfeits and scams rampant on the secondary market—the same problems that come with vintage watches, handbags, and used cars. To the Joneses, there’s a deeper issue at play. It’s the newer, profit-driven influx of sellers over the past 10 years, powered by e-commerce sites that allow transactions with anyone, anywhere, unlike the mom-and-pop stores of old.

It’s like gentrification, says Adena, who grew up in Fort Greene in Brooklyn, N.Y. Long before she became a journalist with ESPN and met Chad, also a Brooklyn native from Crown Heights, at Knicks legend Clyde Frazier’s Manhattan restaurant, she saw her neighborhood becoming harder and harder to recognize. Sneaker culture has followed a similar pattern in going mainstream, she says.

The audience for sneakers has grown immensely from its origins in Black culture to include trend-chasing White kids from the suburbs, says Chad. The problem, he continues, is when the sneaker business shuns those within the community, allowing space only for high-profile athletes or hip-hop artists while ignoring Black kids who want to be a part of it.

White kids influenced by Black culture can find success on YouTube or Instagram, but Black youths find the road a lot tougher. “That’s what we see,” he says. “And we see a problem with that.”

In contemplating the sneaker industry, the Joneses saw few senior executives of footwear companies or celebrated collectors who looked like them. “Our voices were what created this space,” says Adena. “To have our voices and our faces missing from certain spaces is just too much.”

Updated: 6-24-2021

Goat Group, Parent of Sneaker Marketplace, Valued At $3.7 Billion In Latest Funding Round

Company says sales of sneakers during the period doubled on its platform, compared with the previous year.

Goat Group, parent company of an online marketplace for sneakerheads, said it has raised $195 million through private investors to continue its push into international markets.

The latest funding round values the company at $3.7 billion, more than double its valuation when the company raised $100 million in September.

The company also provided detail about its financial performance, saying $2 billion of merchandise was sold on its Goat platform over the past year. Sales of sneakers during the period doubled compared with the previous year.

Goat remains best known as a platform to buy popular or hard-to-find sneakers, and much of its success can be traced to the continued ascendancy of sneaker and streetwear culture. Wealthy shoppers have proved willing to shell out far more than the retail price of popular styles and colorways, fueling a competitive and controversial market for buying and flipping shoes.

The sneaker and streetwear resale market in North America hit more than $2 billion last year, according to Cowen, which estimates that the global market could reach $30 billion by 2030.

Unlike competitors such as StockX LLC and eBay Inc., which are exclusively resell platforms, Goat also sells directly from its more than 350 brand partners, including Gucci, Balenciaga and Alexander McQueen.

In 2019, the company began expanding beyond sneakers into luxury apparel and accessories. Eddy Lu, Goat Group’s chief executive, said in an interview that the retailer has been careful about adding new categories to ensure the marketplace remains in line with the desires of its young customer base.

“We care about authenticity, and that’s why we don’t create all of these verticals,” Mr. Lu said. “We have a point of view on fashion, culture and style.”

The Goat customer base is young, fashionable and comfortable wearing expensive items alongside their secondhand purchases, Mr. Lu said. Of Goat’s 30 million customers, 80% are millennials and Gen Zers.

‘We have a point of view on fashion, culture and style.’

— Eddy Lu, Goat Group CEO

For fashion labels concerned about preserving brand integrity, the Goat marketplace offers access to those shoppers on a more curated platform, he said. “We’re not selling their products next to Nvidia graphics cards and batteries and things like that,” Mr. Lu said.

International markets remain a primary target for growth, Mr. Lu said. Part of the proceeds from the latest funding round will be used to open four additional fulfillment centers this year. Three of those centers will be located in Asia, adding to three existing international facilities. The new facilities will help cut costs associated with international shipping and make shipping speeds more competitive, he said.

The retailer has 13 fulfillment centers across the U.S., Europe and Asia, where it checks the authenticity and quality of resale merchandise before shipping it to customers.

Goat Group, which was founded in 2015, previously raised about $300 million over multiple fundraising rounds, with past investors including D1 Capital Partners LP, Accel, Upfront Ventures and retailer Foot Locker Inc. The latest funding round was led by Park West Asset Management LLC.

Updated: 5-12-2020

Nike Accuses StockX Of Selling Fake Shoes After Reps Bought Counterfeit Sneakers On The Site

Nike sued StockX in February for selling NFTs with Nike’s logo, and has amended the suit to question the online marketplace’s authentication process.

The next battle in the ongoing war between Nike NKE, -0.02% and online marketplace company Stockx is ramping up.

Nike has amended its suit against StockX to include accusations of selling counterfeit merch labeled as “authentic” on its platform. This comes after Nike says it purchased four pairs of fake shoes from StockX over the last few months, including a pair of Air Jordan 1 High OG “Patent Bred” sneakers. A size 11 pair of these shoes sell for around $340 on the secondary market after taxes and fees are applied.

“Those four pairs of counterfeit shoes were all purchased within a short two-month period on StockX’s platform, all had affixed to them StockX’s ‘Verified Authentic’ hangtag, and all came with a paper receipt from StockX in the shoe box stating that the condition of the shoes is ‘100% Authentic,’” Nike claims in the court filing with the Southern District of New York.

StockX sells shoes, apparel and other items from various brands, including but not limited to Nike, Adidas ADS, -0.76% and Under Armour UAA, +6.61%. The merchandise is not owned by StockX at the time of sale; instead the sale is conducted between two individuals who agree on a price, and StockX acts as a middle man to authenticate the product, for a fee.

“We take customer protection extremely seriously, and we’ve invested millions to fight the proliferation of counterfeit products that virtually every global marketplace faces today,” a StockX spokesperson told MarketWatch.

“Nike’s latest filing is not only baseless but also is curious given that their own brand protection team has communicated confidence in our authentication program, and that hundreds of Nike employees – including current senior executives – use StockX to buy and sell products.

This latest tactic amounts to nothing more than a panicked and desperate attempt to resuscitate its losing legal case against our innovative Vault NFT program that revolutionizes the way that consumers can buy, store, and sell collectibles safely, efficiently, and sustainably. Nike’s challenge has no merit and clearly demonstrates their lack of understanding of the modern marketplace.”

Representatives from Nike were not immediately available for comment on the new counterfeit allegations.

Nike initially hit StockX with a trademark-infringement lawsuit in February, accusing the company of violating trademark law by selling non-fungible tokens, aka NFTs, with Nike’s logo. in fact, the “Patent Bred” Air Jordan 1 High OG that Nike claims to have to have bought counterfeits of on StockX’s site, is also one of the eight Vault NFTs that StockX is selling — and its best-selling NFT — which Nike claims infringes on its copyright.

When discussing the trademark portion of the lawsuit, StockX claimed Nike had shown a “fundamental misunderstanding” of NFTs by suing them.

After receiving a $3.8 billion valuation, the Detroit-based sneaker resale platform recently tapped Morgan Stanley MS, -0.38% and Goldman Sachs GS, -0.71% as it prepares to go public at some point in 2022, according to Bloomberg.

Updated: 5-16-2022

Even Thrift Stores Aren’t Immune From Rising Prices

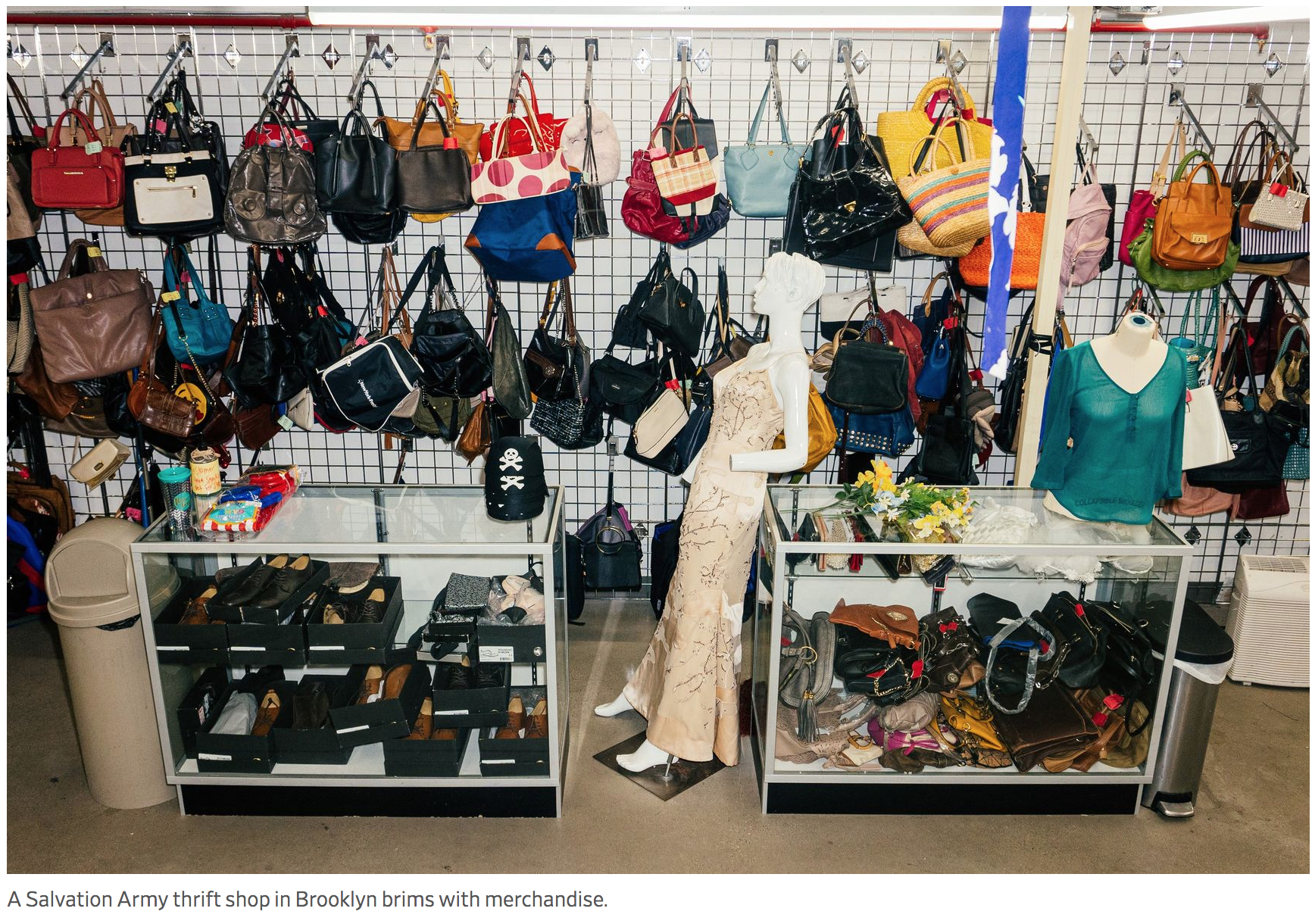

Remember the dollar T-shirt bin? Try $56, for some wares. At Goodwill, the Salvation Army and others, you may have to dig deeper for bargains.

The thrift store is becoming a bit less thrifty.

Shoppers are reporting that prices are inching up at their local thrift stores, which have long been a trusty stopover for a one-dollar T-shirt or five-dollar jacket. Billy Seidel, 33, of South Portland, Maine, a full-time clothing reseller, is baffled by some of the prices at his region’s Goodwill store lately, like a used Carhartt jacket for $50, when a new version retails for about $80.

“Let’s say five, six years ago, everything was a flat line price of 99 cents or $1.99.” Those days, to him, are long gone.

The rise of canny used-clothing resellers has driven some prices up at thrift stores. And with inflation climbing to over 8% since May 2020, even thrift stores are feeling the impact. Nichole Webster-Smith, 30, a clothing reseller in the Seattle area has seen some “substantially overpriced” items in her nearby thrift stores.

She caught the thrifting bug from her mother and began reselling clothes (particularly vintage Patagonia) in recent years. She visits several thrift stores a week in search of gems to flip online. Rising prices have, at times, left her confused as they seem beyond what anyone—even a prospect-hungry reseller—would pay.

Recently, she encountered North Face jackets for as much as $70 (many of the brand’s new jackets sell for a bit over $100) and a vintage Filson duffle bag for $200, “which felt a bit absurd.”

Bill Parrish, senior consultant in donated goods retail for Goodwill Industries International, said that while there has not been a set price increase across the board at the non-profit’s retail locations, each Goodwill organization adjusts its pricing periodically “to ensure that they are in line with the value of the category of items provided.”

Greg Tuck, the assistant national community relations and development secretary at The Salvation Army USA, likewise acknowledged that prices at the charity’s thrift stores were set by each store, and have crept up in some cases.

While thrift stores do not purchase their inventory (it largely comes by way of tax-deductible donations) they still have to pay for operational costs such as staffing, utilities and rent. “We are always trying to make sure that people are earning a livable wage,” said Mr. Tuck.

Still, he stressed that prices at Salvation Army stores are not reaching an untenable level for its core, budget-conscious customers. “We’ve got to make sure that there’s stuff for them that is affordable,” he said. To be clear: those dollar T-shirts and five-dollar jackets will always be there.

Beyond inflationary aftershocks, thrift stores have gotten wise to the fact that there are covetable, profitable gems lurking in their trove of textiles. “Our staff are trained, as much as we can, to identify the high-value things and then we’ll sell them for high value,” said Mr. Tuck.

Salvation Army’s 987 thrift stores fund its 96 nationwide rehab centers. Goodwill uses its proceeds to support child care, financial education and other social services.

In the past few years, thrift stores have honed their ecommerce chops, flipping higher-value goods through sites like eBay and Instagram. The Salvation Army of Atlanta, for example, recently sold a vintage Larry Bird T-shirt for $56 and a Billy Reid cardigan for $46 via its eBay page.

“Many of the stores that I personally go to are setting up their own eBay shops and they’re selling stuff online themselves,” said Suzanne Butler, 35, a longtime thrifter and part-time reseller in the Nashville suburbs.

It’s easy to see why a thrift store might want to get in on the resale action. According to a report from the resale start-up ThredUp the second-hand clothing market was at $36 billion in 2021 and is on track to hit $77 billion by 2025.

Used clothes can now fetch gobsmacking prices on the secondary market. In 2020, a 1992 shirt showing the Genie from the movie “Aladdin” sold for $6,000 over social media. A year later, a Grateful Dead T-shirt from 1967 sold at Sotheby’s for $17,640.

These big numbers have helped fuel a secondhand gold rush, with resellers flocking to their local thrift stores in search of a single gem that could pay off that month’s rent.

“There’s more people looking for [vintage]. And so that’s probably taking away some inventory,” said Turner Isenberg, 24, a reseller in Little Rock, Ark, who hunts for vintage varsity jackets, aged T-shirts and military fatigue pants.

As in any market, scarcity drives prices up, so resellers seeking a culprit for elevated prices may want to look in the mirror. But the idiosyncratic thrifting market has many variables. “Not all resellers are created equal,” said Ms. Webster-Smith of the Seattle area.

She may be willing to pay for a pair of Arc’teryx pants, while the young shopper next to her is more interested in a vintage Mariners jersey he can boast about on TikTok. In the thrift store aisles, a deal is really in the eye of the beholder.

A price also hinges on how savvy a store worker is. One employee could know that a pair of Lululemon leggings is worth $40 or so on eBay, while their shiftmate might have never Googled the brand.

This surge of flip-happy prospectors has ignited fears (particularly on Gen-Z favorite social media platforms like TikTok) that thrift stores may get cleaned out of their inventory, leaving frugal shoppers with nowhere to shop. Companies that operate thrift stores dismissed these concerns.

“I don’t think we’ll ever be in a place where we don’t have stuff,” said Mr. Tuck, noting that the Salvation Army received $68 million worth of donations during last year’s Christmas season alone. “Part of our culture in America is that we are consumers and we are replacers, and we just hope that the public always see us as a viable place to make those kinds of donations.”

At Goodwill, clothing makes up about 48% of its sales, a figure that has hardly fluctuated over the years. In other words, resellers aren’t making much of a difference.

The glut of clothing on-hand at thrift stores is often visible. “I was just at Goodwill yesterday and they were rolling out racks and racks,” said Ms. Butler of the Nashville area. “You drive by the donation site, and it’s literally overflowing.”

Updated: 6-6-2022

StockX Denies Nike’s Accusations That It Sells Counterfeit Shoes

Sneaker marketplace StockX LLC denied Nike Inc.’s accusation that it is selling counterfeit shoes, saying the platform has one of the strongest authentication processes in the industry and has devoted millions of dollars to battle the spread of fake products.

The world’s largest sneaker maker claimed in a February lawsuit that StockX is infringing trademarks through a service called Vault NFTS. Nike escalated the battle last month, saying it has purchased counterfeit shoes on the site despite promises that everything sold on the platform is authentic.

StockX fired back on Monday. In a court filing, the company said its authenticators use their own knowledge along with the company’s own artificial intelligence-based technology to ensure all products sold on the site are real.

Nike’s suit is “nothing more than a baseless and misleading attempt to interfere with an innovative and efficient method to trade in current culture,” StockX said. The shoemaker’s allegations “show a fundamental misunderstanding of the various functions NFTs can serve,” StockX said.

“StockX is no different than major e-commerce retailers and marketplaces who use images and descriptions of products to sell physical sneakers and other goods online, and which consumers see (and are not confused by) every single day,” StockX said. “Nike’s suit threatens the legitimate use of NFTs as claim tickets not just by StockX, but by other innovators that also use NFTs to track title to physical goods held in a vault, such as fine art, whiskey, and wine.”

Updated: 8-3-2022

Sneakerhead Accused of Running Huge Air Jordan Ponzi Scheme

Zadeh Kicks promised the hottest sneakers at discount prices. Buyers say they never got their shoes and are out millions of dollars.

For years, he seemed like a wizard of Niketown – a Lamborghini-loving sneakerhead who made millions peddling rare Air Jordans at crazy low prices.

Now, this consummate shoe salesman has been accused by federal authorities of masterminding a Ponzi scheme custom-fit to these strange financial times.

After all the get-rich dramas and market mischief of the pandemic economy – from cryptocurrency to SPACs, to “stonks” and more – it’s come to this: a Bernie Madoff of sneakers.

That, in a nutshell, is how authorities characterize Michael Malekzadeh, of Eugene, Oregon. Prosecutors say Malekzadeh, 39, and his Zadeh Kicks LLC swindled thousands of people across the nation in a multimillion-dollar scam involving nubuck and leather, rather than stocks and bonds.

As portrayed by the feds, the fraud ran for years — and unraveled in months. In the end, Malekzadeh appears to have been undone by the spike in demand during the pandemic, as well as one specific sneaker: the Air Jordan 11 Retro Cool Grey.

After nearly a decade in business, Malekzadeh was charged by federal authorities last week. On Wednesday, he plans to plead not guilty to charges of wire fraud, conspiracy to commit bank fraud and money laundering. He faces as much as 30 years if convicted on the most serious count, conspiracy to commit bank fraud.

“Mr. Malekzadeh is not hiding from his conduct,” his attorney, Joanna Perini-Abbott, said. “He has consistently taken full responsibility for his actions and will continue to do so.”

Whatever the outcome, a Ponzi scheme involving Jordans and Yeezys, of all things, seems made for this moment in more ways than one.

Over the past five years, a confluence of forces – from high fashion to sports culture to online everything — turned collecting sneakers into a multibillion-dollar business. But as with so many things, the pandemic changed the market in new and surprising ways.

Suddenly, home-bound collectors and day-traders were flipping Nikes and Adidas. Many used dozens of different credit cards to finance their purchases and prices soared.

Malekzadeh rode this resale market to improbable heights. From his warehouse in Oregon, birthplace of Nike Inc., he offered sought-after kicks at below-market prices even before manufacturers released them.

In truth, prosecutors now say, Malekzadeh was taking orders – and collecting money — for thousands of sneakers he didn’t have and couldn’t get, at least for prices that made any sort of economic sense.

When customers’ orders didn’t arrive, he bullied and blustered and offered store credit and gift cards that would more than make up the difference, prosecutors say. The ruse kept the scheme afloat even as it enriched certain customers who got in and out before other people.

Zadeh Kicks appeared to be running its operation smoothly in the years leading up to the pandemic-induced demand. That’s when Malekzadeh got in way over his head.

In some ways, it’s remarkable Malekzadeh got as far as he did. His business lacked sophisticated systems to process orders, track inventory and ship the product.

Other than his fiancee, who’s also being charged for her part as chief financial officer of Zadeh Kicks, Malekzadeh ran alone. Prosecutors say he falsified over 15 loan applications for more than $15 million in bank financing.

The latest limited-edition Air Jordans, the 11 Cool Grey, appears to have been a step too far.

As Nike prepared to drop the new high-tops last December, Malekzadeh made a move, prosecutors say. Nike was pricing the 11 Cool Grey – nubuck upper, grey patent-leather mudguard – at $225.

But Malekzadeh’s company offered to sell them for as little as $115, before the December release date, with the understanding that buyers agreed to take delivery a few weeks after the official drop.

Zadeh Kicks sold 600,000 pairs. It only had 6,000.

Most customers never got the shoes they paid for. Zadeh Kicks, however, pocketed $70 million, prosecutors say.

According to court documents, Malekzadeh spent much of his profits on Bentleys, Ferraris and Lamborghinis. Some $3 million went to Louis Vuitton bags, jewelry, furs and watches as expensive as $600,000 a piece.

So far, the FBI has seized $6.1 million in cash from Malekzadeh, plus watches, as well as about 1,100 pairs of sneakers from his personal collection.

Unable to fulfill orders or refund customers’ money, Zadeh Kicks has since gone under, but according to the court-appointed receiver, its Oregon warehouse still holds 60,000 pairs of sneakers.

Thousands of customers, meantime, are tallying their losses.

Jeremy Rogers, 30, a clinical researcher in Fort Worth, Texas, rattles off his purchase history: 100 pairs of the Air Jordan 11 Cool Grey, 300 pairs Air Jordan 4 Retro Lightning, 225 pairs of the Jordan 4 Retro Military Black, 100 pairs of Jordan 4 Retro Shimmer, 20 pairs of Travis Scott Jordan 1 High Fragment.

In all, he figures he spent $143,000 in sneakers he didn’t receive, spread over 15 credit cards.

But the ones that he did get, Rogers says he resold for far more than he bought them. The 100 pairs of Jordan Shimmer sneakers he bought for $160 from Malekzadeh, ended up selling for $315 a piece. He made about $15,500 on that one sale.

There were also other ways to make money from Malekzadeh, even if orders never arrived. Instead of refunding customers for undelivered sneakers, Zadeh would offer to buy back the same pair for cash and gift cards in excess of the amounts paid by his customers for the sneakers

“I think within three cycles, I turned $6,000 into $20,000 just cycling through and letting him buy them back for me or giving me a gift card,” said Rogers, who calculates he’s ordered about one thousands pairs of sneakers from Malekzadeh over the past two years.

Despite his ultimate failure, customers and industry watchers still wonder how Malekzadeh sourced so many rare sneakers. The shoes appear to have been legit, not knockoffs. Even so, a review of counterfeit sneakers was among the first things to take place as soon as Malekzadeh dissolved his company.

Rumors floated about him securing shoes from online retailer StockX. Others suspect he’d formed relationships with retailers over the years that helped him get hold of hard-to-get sneakers.

“Is this on the books and legitimate with brands? Hell no,’’ said Matt Halfhill, founder of Nice Kicks, a sneaker blog.

Nonetheless, Halfhill suspects the industry often turns a blind eye to such practices, referred to as “backdoor” agreements.

Even some customers suspected something might be amiss.

“There’s no way this guy can sell sneakers for 150 bucks, for something that costs the consumer $250, but guess what?,” said Johnny Liu, who says he bought 400 pairs of sneakers from Malekzadeh’s company. “The order actually came, and they were authentic.”

Still, Liu, who works for an IT company in California, says he’s now out about $70,000.

It’s hard to know how many people have been caught up in the supposed shoe scam. The court-appointed receiver has gotten 3,500 emails from customers who say they’re still waiting for their sneakers.

Those who paid via wire transfers have probably lost their money but customers who used credit cards are trying to recover some of their money by filing chargeback claims through banks or PayPal.

A bankruptcy lawyer for Malekzadeh’s company says various options are on the table, including an obvious one: Selling all those sneakers in the warehouse.

Some aren’t waiting. Right after Malekzadeh filed to dissolve his company, angry customers showed up at the Zadeh Kicks warehouse, local media reported.

Malekzadeh called the police for help four different times, and one officer asked for backup after reports of a shot fired. According to court documents, Malekzadeh had security cameras installed to safeguard what’s left of his sneaker stash.

Updated: 8-4-2022

Cheapskates Rejoice: Free Samples Are Back

Tidbits return, putting grocery-store grazers on the hunt; ‘I stalk the sample person’.

Jessi Levine, a creative director at a Kansas City, Mo., technology company, could feel strangers’ eyes on her. She felt uncomfortable and awkward, she said, but energized, too.

She took a breath. She popped the small cube of cheese into her mouth, and chewed.

Ms. Levine is one of legions of U.S. consumers who are reacquainting themselves with free samples––a time-honored perk of supermarket shopping that all but vanished after the pandemic began spreading in early 2020.

“It was so exciting to me,” Ms. Levine said, referring to the free cheese she ate at a Whole Foods Market, something she said she hadn’t encountered in about two years. “I think it was a part of American society that we lost along with everything.”

Shoppers who have yearned for nibble-sized freebies to return to supermarket aisles say the experience now has a new cache—minute thrills, served on crackers.

Consumers are again lining up for slivers of salami or teeny paper cups of guava juice and again relishing the pleasure of snacking their way through grocery stores and not needing lunch after.

Some though say they are noticing fewer samples, and new rules or social cues about consuming them. Some samples have been given out in little bags by workers behind plastic barriers.

Other businesses have bid free samples good riddance.

“It was a running joke in our staff meeting that people would taste five or six samples and buy something totally different,” said Suzanne Varecka, who owns Honey & Mackie’s ice cream shop in Plymouth, Minn., that sells flavors ranging from carrot cake to Guinness brownie.

She began charging $10 for a flight of several ice cream flavors when the state prohibited samples. Ms. Varecka said she is continuing to offer flights and doesn’t plan on bringing free samples back.

Hanna Palo, who lives in Dayton, Ore., said that when her local Costco Wholesale Corp. stopped offering samples at the start of the pandemic, she started shopping online. “What’s the point of going?” she said.

A few months ago, Ms. Palo said, Costco started bringing back its samples. She returned, too. At first she encountered unusual free samples of items such as tissues––which she said she still grabbed.

More recently she found freebies ranging from chocolate milk to barbecued meat in almost every aisle. Life feels normal again, she said. “You can slow down and communicate with people.”

At a warehouse store in Long Island, N.Y., Yvonne Sing said a mob quickly formed around a station set up with a slow cooker, where a worker handed out frankfurter samples. “There was a wall of people getting hot dogs,” she said. “I think everybody missed that process of sampling things.”

For some shoppers, the glory days of grocery store grazing haven’t fully returned, because samples are smaller, more limited, or they aren’t food at all, like tin foil.

Jeff Levy, a lawyer in Providence, R.I., said samples he sees at Whole Foods lately are disappointingly limited compared with pre-Covid. Mr. Levy, who described himself as willing to try anything that’s free, said tiny cheese cubes with toothpicks he sees now don’t compete with the grilled meat and other tidbits staff there used to offer.

“Samples are definitely harder to come by,” he said, but “I’m happy that they are back. It breaks up the shopping a little bit.”

Whole Foods said samples vary by location and range from ones offered in containers with tongs for self-serve to those in single-use cups given by staff.

The company said stores decide on products and serving styles. It has also introduced a sampling program on Amazon orders, placing freebies in some delivery and pickup orders to surprise customers.

In San Francisco, the Ferry Plaza Farmers Market and Mission Community Market said there are tighter rules around samples, and not all sellers have resumed offering them. Other farmers markets have new limitations, like designated eating zones where shoppers are instructed to take their samples before consuming them.

Many companies count on sampling to boost sales.

The return of free samples is helping revive business at Pike Place Market in Seattle, officials there said. Travel guides in the past have outlined how tourists can sample enough of the farmers market’s yogurt, cheese and other items to make for a free meal.

Jenny Yang, president of tofu maker Phoenix Bean LLC, said that when the company had been able to hand out samples at Chicago farmers markets, eight out of 10 people who tried Phoenix’s products wound up buying them. “We call it ‘conversion tofu,’ ” she said.

Phoenix Bean’s sales fell 40% in 2021, she said, compared with before the pandemic, with sampling prohibited and foot traffic down at farmers markets. Since farmers markets in Chicago reopened with sampling allowed this summer, Ms. Yang said it has made an immediate difference. “We have had a new product, tofu dip, that we tested out a few Saturdays ago…OMG, it is gone in one hour.”

Ryan Sciara said his Kansas City-based Underdog Wine used to host free tastings every Thursday for an hour-and-a-half. Afterward, the shop was often saddled with leftovers.

After putting free tastings on hold over the past two years, Mr. Sciara said he is considering bringing them back––but with reservations required and a charge for private group tastings.

“There are a lot of people asking when free tastings are going to come back,” Mr. Sciara said. “They want a free drink.”

In Kenosha, Wis., Nicole Poulsen said her twice-weekly shopping trips to Costco have now turned into a smorgasbord of samples, including cooked foods, prepackaged snacks such as chips and drinks. Her recent favorites include Key lime pie, bacon and chicken chunks. It’s enough to feel like a small meal, she said, if she’s persistent.

“I stalk the sample person,” she said.

Updated: 8-25-2022

Nearly 60,000 Sneakers In $85 Million Ponzi Scheme To Go On Sale

Court-appointed receiver looks to unload shoes from Zadeh Kicks, whose owner is charged with fraud and money laundering.

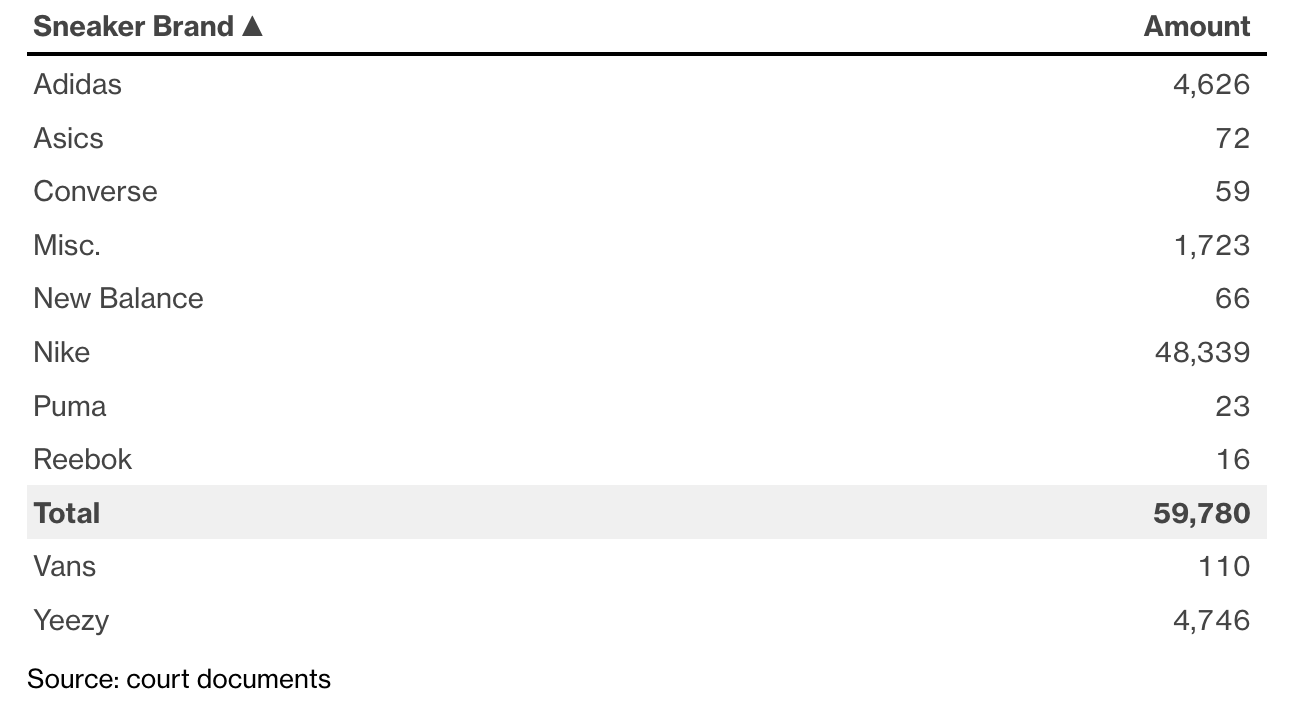

On Clearance: 48,339 pairs of Nikes. And 4,746 Yeezys. And 4,626 Adidas.

In all, a neatly boxed 59,780 pairs of shoes — nearly enough to shod all of Palo Alto or Pensacola — from a man authorities have portrayed as the Bernie Madoff of sneakers.

Almost one month after federal prosecutors accused Michael Malekzadeh of orchestrating a multimillion-dollar Ponzi scheme involving coveted sneakers, a court-appointed receiver is looking to unload a trove of status-y shoes squirreled away in his warehouse.

Among the first to go: 1,100 or so pairs from Malekzadeh’s personal collection, both new and used, according to court documents.

The goal is to sell as many of the sneakers as possible, as soon as possible, to reimburse thousands of customers who authorities say ordered shoes but never got them.

Experts caution that even if all the sneakers sell, the amount raised wouldn’t go anywhere near covering what the victims are owed. Customers might not get their money back for months, if ever.

“It’s going to take them a lot of work,” said Yu-Ming Wu, founder of Sneaker News.

Sneaker Sale

Inventory In The Zadeh Kicks’ Warehouse Adds Up To Almost 60,000 Sneakers:

Federal prosecutors charged Malekzadeh, 39, of bilking customers out of more than $70 million and falsifying loan applications for more than $15 million in bank financing.

Earlier this month, Malekzadeh pleaded not guilty to charges of wire fraud, conspiracy to commit bank fraud, and money laundering. In May, he dissolved Zadeh Kicks, which he had been running since 2013.

Representatives for his company didn’t respond to requests for comment about the sale. Almost all the inventory inside the warehouse has been accounted for, court documents show, and preliminary discussions with potential buyers or consumer resale platforms have already begun. The date of the sale is yet to be determined.

The receiver, David Stapleton, is trying to figure out how to unload the inventory. One possibility is to sell the sneakers in bulk. Another is to unload them through various resale platforms, according to court documents. Selling Malekzadeh’s personal collection first is meant to “test the market.”

The alleged sneaker caper seems custom-made for these days of meme-stock zaniness. From his warehouse in Eugene, Oregon, Malekzadeh offered to sell limited-edition Air Jordans and other brands at below-market prices before manufacturers released them.

Prosecutors say he took orders — and collected money — for thousands of sneakers he didn’t have and couldn’t get, at least for prices that made any sort of economic sense.

Zadeh Kicks pocketed $70 million from the pre-sale of one model of Air Jordans alone, the 11 Cool Grey, prosecutors say. The total amount of money owed from all pre-sales has yet to be determined.

His warehouse is now being guarded by a security officer. Experts say the cache, still boxed and tagged, could be worth anywhere between $12 million and $20 million — at best.

Jared Goldstein, author of Sneakerlaw, a book about the sneaker industry, said some of the shoes might be worth thousands on the resale market but calculated that the majority will average $200 to $300.

The real test for the receiver will be how well he can price these sneakers on the market if sold in bulk, Goldstein said, arguing that even $20 off 60,000 pairs can add up to millions of dollars.

“These people that are handling it I’m sure are not so savvy when it comes to sneakers,” Goldstein said.

Court documents list more than 15,000 creditors over 197 pages, ranging from individuals to financial firms including PayPal Holdings Inc., American Express Co. and Chase Bank. It remains unclear whether the financial institutions involved will receive their money back first.

One challenge is ensuring all of the shoes are authentic. Another is the vagaries of the sneaker resale market, which exploded during the pandemic along with cryptocurrencies and “stonks.” Like the stock market, sneaker prices have taken a tumble this year.

“The market is on a downward trend across the board,” said Matt Halfhill, founder of Nice Kicks, a sneaker blog. “There’s no way it’s going to come even close to covering the victims.”

Updated: 9-8-2022

Swiss Running-Shoe Brand On Launches Resale Site In Sustainability Push

On will resell used shoes on the new site, called Onward, and plans to add clothing by the end of the year.

The Swiss athletic brand On is launching a resale site Thursday, making it the latest company to enter the fast-growing apparel resale market.

On Holding AG, which is backed by tennis star Roger Federer, went public last year and expects to see net sales of 1.1 billion Swiss francs ($1.1 billion) in 2022.

The company has made sustainability a focus of its business. It set science-based climate targets, per its 2021 environmental impact report, aiming to cut emissions it directly generates 46% by 2030 and to reduce indirect emissions arising from the company’s supply chain and product use.

On also strives to be fully circular, meaning it would someday only use recycled materials to make its products and would generate little waste in their manufacture, distribution and use.

“It will obviously take us years to be fully circular,” said Samuel Wenger, On’s global direct-to-consumer head. The new resale site, Onward, “is a perfect in-between step,” Wenger said.

The fashion industry has a gigantic climate and waste problem. Between 2% and 8% of global carbon emissions come from big fashion, according to the United Nations, and it’s also a major source of plastic pollution.