How Aging Japan Defied Demographics And Revived Its Economy (#GotBitcoin?)

It encouraged the elderly and women to work and broke a longstanding taboo against immigration. How Aging Japan Defied Demographics and Revived Its Economy

Because demographics are supposed to be destiny, Japan was long ago consigned to stagnation with its aging population and rock-bottom birthrate.

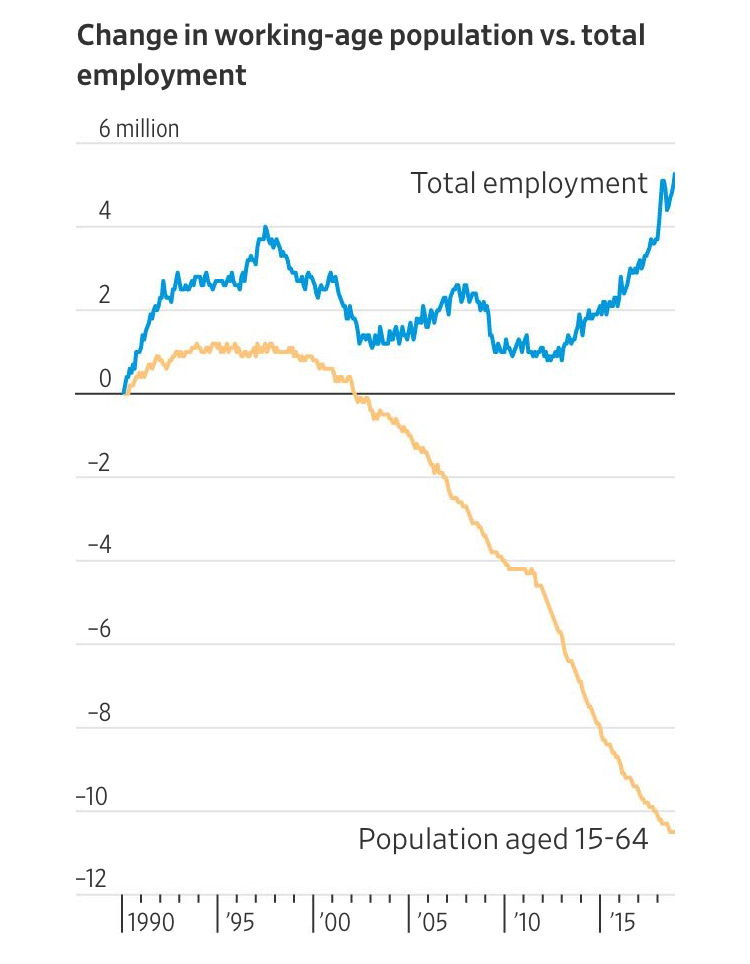

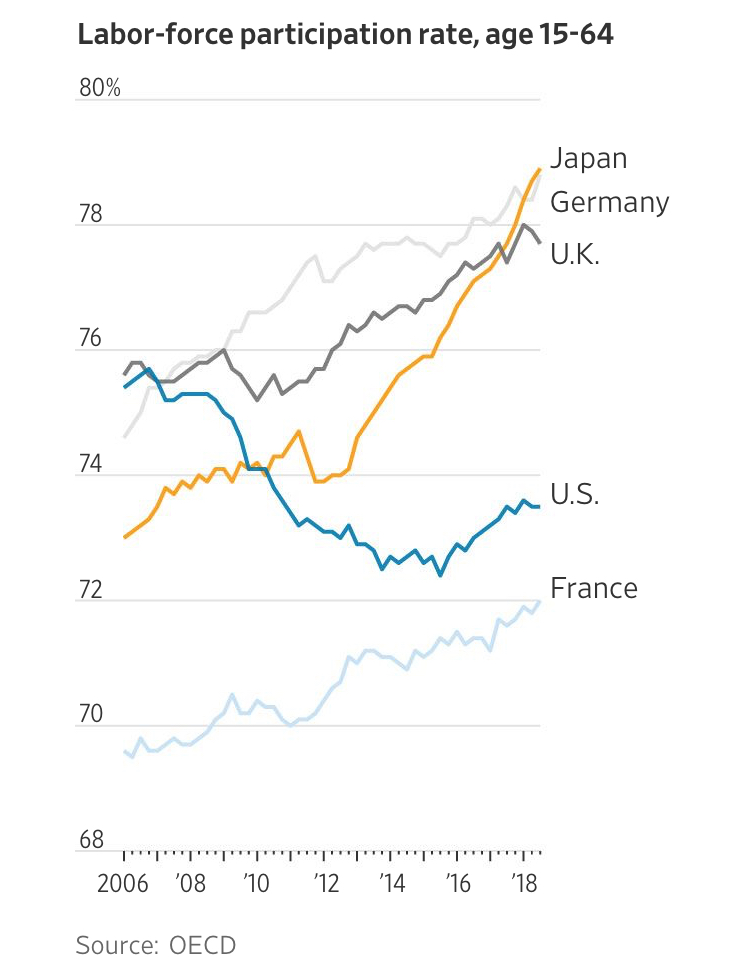

But in recent years Japan has defied destiny. Since 2012, its working-age population has shrunk by 4.7 million, yet the number of people working has surged by 4.4. million, the critical ingredient in what is now Japan’s second-longest economic expansion since World War II. The proportion of the population in the labor force has risen sharply since 2012, by more than in any other major advanced economy.

Japan is refreshing its labor force from three often-neglected pools: the elderly, women and foreigners. This offers important lessons for the many other countries that now, or will soon, face similar demographic pressures. A population’s size can still impose limits on long-term growth, but they may be further away than long assumed by economists and policy makers.

Aging Population

Employment has soared in Japan since 2012 even though the working-age population is plunging.

Unemployment near a 25-year low of 2.5% has forced employers to be less picky about whom they hire. Policies enacted by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, meanwhile, are reshaping cultural norms about when to retire, whether women with children should work and whether Japan should admit overseas workers.

“The fabric of the country has changed quite a bit in the last 10 and especially the past five years,” says Izumi Devalier, head of Japan economics for Bank of America Merrill Lynch in Tokyo.

The Japanese government has long sought to lengthen working lives; in 2004 it began raising the social security retirement age from 60 to 65 and required companies to either raise or abolish the retirement age or introduce a system for re-employing workers who do retire. This has kept Japanese men on the job well into their 60s and 70s.

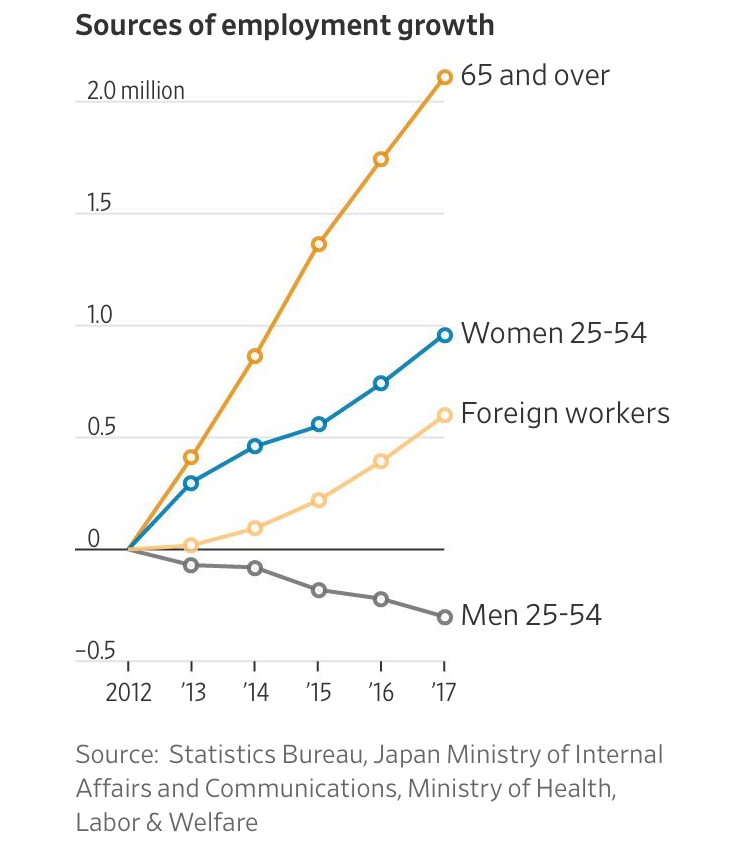

Diversifying The Labor Pool

Women, foreigners and the elderly have contributed the bulk of Japan’s employment growth.

Ishikawa Prefecture on Japan’s west coast is going a step further to cope with its unusually severe demographic pinch. Completion of a bullet train line from Tokyo to the prefecture capital, Kanazawa, four years ago fueled an influx of tourists, while manufacturing, especially of food products, is booming. But its population has been declining since 2005, a product of both declining birthrates and out-migration, in particular to Tokyo and Osaka. It boasts one of the tightest labor markets in the country with two vacancies for every unemployed person.

Wataru Seki, an official in the local career and life-support department, says the worker shortage can handicap business growth and degrade the quality of life.

“If population declines, service industries like supermarkets will withdraw and then people will have trouble with shopping. We have more households of just one person, and they may be isolated. The scale of the economy shrinks so tax revenue is going to be smaller and that’s going to affect regional finances.”

The prefectural government has tackled the problem with programs to draw retirees and mothers into the workforce and reverse the out-migration of young people.

Government officials were inspired in part by Ohara, a family-owned company that makes desserts and puddings from the region’s prized fruits and vegetables, such as sweet potatoes. Five years ago the owner, Shigeru Ohara, needed to staff a new shift and went the usual route, posting in local newspapers and at the government jobs center. He hired workers from a temporary staffing agency; many never showed up for their first day of work. “Even if young people came, they wouldn’t last. And they didn’t come,” he says.

Then, on the suggestion of a friend, he inserted a flier in newspapers delivered to nearby apartment blocks filled with elderly retirees asking for workers, with one notable condition: Applicants had to be 60 or over.

He got 20 applicants and hired nine, double his original plan. Today, elderly workers, averaging 70 years old, comprise a quarter of his 80 employees. He raves about them.

“Because of their long working experience, they know how the organization works, what is expected of them, they never come late, and they take orders from younger people,” he says. They are content with tasks that younger workers find repetitive and tedious such as removing and baking the fruit of a pumpkin for paste. Not only do they work the 5 a.m. shift, they show up early.

Satoshi Kataoka, now 70, is one of them. He retired from a medical manufacturer at age 65 but still wanted to work; his pension was enough to live on but not pay for much leisure. Several jobs didn’t work out because they were too physically demanding. Then he saw an ad for a job at Ohara. He enjoys the company of his co-workers and his wife likes that he’s not hanging around the house. Though the salary is barely a third of what he earned before he first retired, he says, “It’s good enough, because now I have pocket money.”

In 2017, with financial support from the central government, Ishikawa launched a special program to bring retirees back into the workforce. It trains employers on how to recruit elderly workers and design the job to meet their abilities. It should be physically undemanding, such as checking inventory, working the cash register at a convenience store, or working on an assembly line, and in shorter shifts of a few hours. It then matches those employers to available workers. In its first six months it placed about 200 elderly workers, seven times the original target.

The prefectural government has made similar efforts to recruit more women into the workforce. Women prefer predictable hours to pick up children from day care, and shorter workweeks. Factories, the biggest source of unfilled jobs, offer the first but not the second. Small companies don’t know how to adapt, says Mr. Seki. “We have specialists who we can dispatch to the company and advise them on how to make the change,” he says.

Female labor participation has long been one of Japan’s handicaps. No longer. In 2012, female participation was 63%, marginally above the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development average of 62%. By 2017, it had shot up to 69%, five points above the OECD average.

Part of this is due to more older women working. Since 2012, the participation rate of women aged 55 to 65 has shot from 54% to 63%. Corporations, desperate for employees, are hiring employees they never have before, including women who only want to work 10 hours a week.

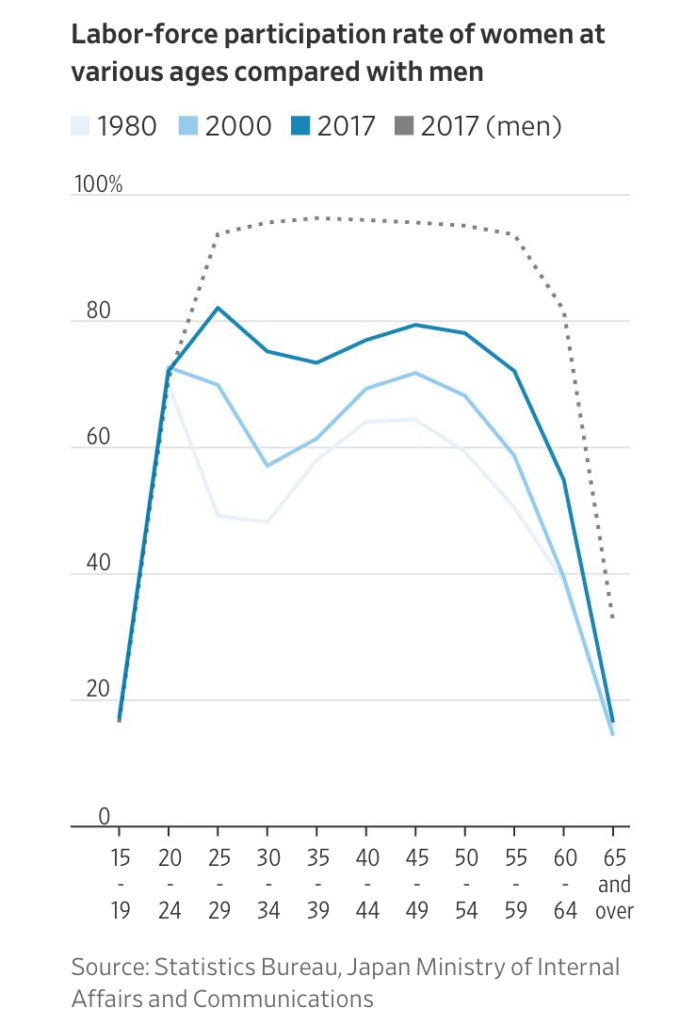

The Disappearing ‘M-Curve’

Fewer Japanese women now leave the labor force to have children.

This is part of Japan’s efforts to address the “M-curve,” a peculiar feature of its labor market. Japanese women’s participation peaks in their 20s, then drops sharply into their 30s when they have children, then rises again in their 50s. By contrast, participation by women in the U.S. shows no such dip.

As far back as the 1990s, Japanese governments have sought to flatten the M-curve through extended parental leave, increased child care, and rewards for firms that promote work-life balance. They had virtually no impact until around 2009 when employers were required to offer six-hour days if the worker asked for it, a huge boon for new mothers, according to Nobuko Nagase, an economist at Ochanomizu University.

The efforts went into overdrive under Prime Minister Abe’s “womenomics” policies, which included significantly expanding the supply of child care. By 2015, Tokyo had 38 spots for every 100 two-year-olds, up from 28 in 2008.

Ms. Nagase’s research found these efforts raised participation by women with small children from 40% in 2009 to 50% in 2015. The proportion with permanent, regular jobs rather than temporary contracts, also rose sharply while it fell for most other demographic groups.

Advocates for women have urged employers to rethink what constitutes useful work. The traditional Japanese company equated output with hours, and thus employees worked long overtime even if those extra hours weren’t especially productive, says Yoko Ishikura, Professor Emeritus at Hitotsubashi University. Experience was equated with seniority and thus employees were promoted based on tenure rather than performance. Since promotion often meant moving, that made it impossible for wives to establish careers.

There is “a very strong notion that 9-to-5, or 9-to-7 at an established company is the ideal,” says Ms. Ishikura. “That’s why rush hour trains are so crowded. As long as you stick to that, it limits potential opportunity for those who may not be able to work part-time to join the labor market.”

Companies, with encouragement from the Abe government, are slowly reworking those assumptions. The government has begun pressuring companies to reduce overtime, and add women to the board of directors. Mr. Abe boosted the parental leave allowance, and lengthened allowable leave for fathers. The share of new fathers taking advantage rose, albeit only to 5.2% in 2017. This meant fathers were sharing a bit more of the burden of caring for newborns, Ms. Nagase found.

The final source of labor Japan has tapped is foreigners. Immigration has long been Japan’s third rail and it is still difficult for a foreigner to acquire Japanese citizenship. But the Abe government has considerably loosened the rules for working in Japan. In 2015 it began admitting foreign construction workers to alleviate shortages as the country rebuilt from its 2011 earthquake and prepared for the Tokyo Olympics in 2020, and for housekeepers in special zones. In 2017 it did the same for nursing-care workers.

It now allows foreign “technical interns” to stay for three to five years, and issues “green cards”—permanent residence—to highly skilled professionals after a one-year stay.

Last month, the Abe government created two new visa categories that it expects to draw 340,000 additional mostly blue-collar workers from abroad, over the next five years.

There has been a surge of foreign students who are permitted to work as long as they attend school in Japan. Bank of America Merrill Lynch’s Ms. Devalier says many are recruited by Japanese employers in Vietnam to attend Japanese language schools then fill low-paid service jobs such as in hotels and stores.

From Laggard To Leader

Japan’s labor-force participation rate now tops that of other major industrialized countries.

“Abe did not one day give a speech saying, ‘We have changed our immigration policy,’ ” says Ms. Devalier. “This is all happening quietly behind the scenes.” The number of foreign-born workers nearly doubled between 2012 and 2017 to 1.3 million.

The combined effect of the elderly, women and foreigners on labor force has been to sustain Japan’s underlying growth rate in the past few years as well as hold off the wage and inflationary pressures that would ordinary emerge when unemployment is so low.

Can it last? None of the new sources of labor force growth is a substitute for increased population. Temporary foreign workers can be fired and sent home as soon as the economy weakens. Participation by the native-born can’t rise forever. Robert Feldman, economist and adviser at Morgan Stanley in Japan, says the rise in participation of women with small children has peaked, noting: “There’s not much of an M curve left.”

He also doubts labor-force participation for the elderly can rise much more since it is now back to where it was in the 1970s when many Japanese farmers worked into their 70s.

Finally, many of these newly employed elderly, female and foreign workers work in low-productivity, low-wage jobs, limiting the boost to Japanese GDP. The elderly workers at Mr. Ohara’s factory earn only marginally more than the local minimum wage of 806 yen, roughly $7.40 per hour.

Asked if Ishikawa’s efforts can overcome a shrinking population, the government’s Mr. Seki pauses, then says: “I know it is tough. But we have to put in the effort.”

Related Articles:

A Retirement Wealth Gap Adds A New Indignity To Old Age (#GotBitcoin?)

The New Retirement Plan: Save Almost Everything, Spend Virtually Nothing (#GotBitcoin?)

401(k) or ATM? Automated Retirement Savings Prove Easy to Pluck Prematurely

Even A Booming Job Market Can’t Fill Retirement Shortfall For Older Workers (#GotBitcoin?)

Your questions and comments are greatly appreciated.

Monty H. & Carolyn A.

Go back

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.