Fracking’s Secret Problem—Oil Wells Aren’t Producing As Much

Data analysis reveals thousands of locations are yielding less than their owners projected to investors; ‘illusory picture’ of prospects. Fracking’s Secret Problem—Oil Wells Aren’t Producing As Much As Forecast

Thousands of shale wells drilled in the last five years are pumping less oil and gas than their owners forecast to investors, raising questions about the strength and profitability of the fracking boom that turned the U.S. into an oil superpower.

Third-party investigators compared the well-productivity estimates that top shale-oil companies gave investors to projections from third parties about how much oil and gas the wells are now on track to pump over their lives, based on public data of how they have performed to date.

Two-thirds of projections made by the fracking companies between 2014 and 2017 in America’s four hottest drilling regions appear to have been overly optimistic, according to the analysis of some 16,000 wells operated by 29 of the biggest producers in oil basins in Texas and North Dakota.

Collectively, the companies that made projections are on track to pump nearly 10% less oil and gas than they forecast for those areas, according to the analysis of data from Rystad Energy AS, an energy consulting firm. That is the equivalent of almost one billion barrels of oil and gas over 30 years, worth more than $30 billion at current prices. Some companies are off track by more than 50% in certain regions.

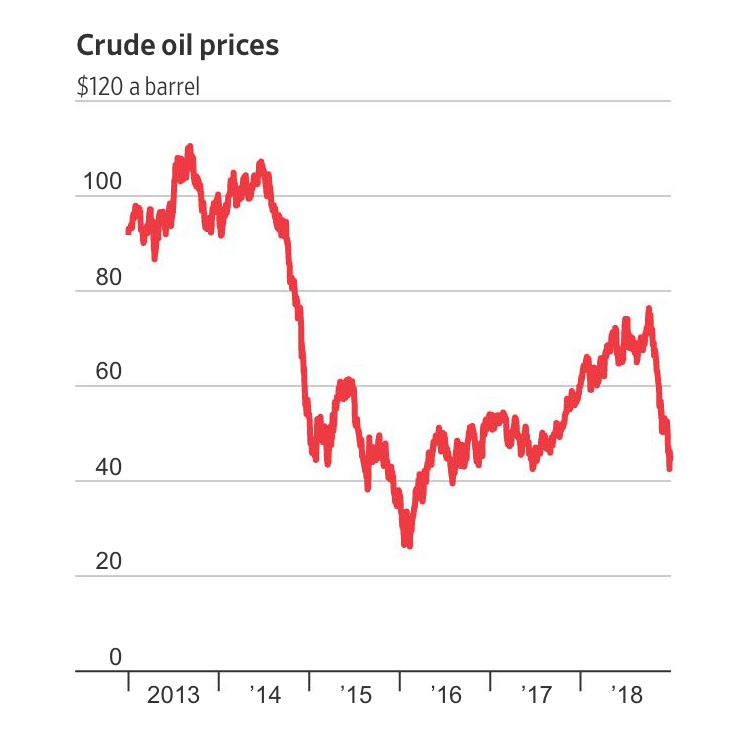

The shale boom has lifted U.S. output to an all-time high of 11.5 million barrels a day, shaking up the geopolitical balance by putting U.S. production on par with Saudi Arabia and Russia. The findings suggest current production levels may be hard to sustain without greater spending because operators will have to drill more wells to meet growth targets. Yet shale drillers, most of whom have yet to consistently make money, are under pressure to cut spending in the face of a 40% crude-oil price decline since October.

An Oil-Production Facility Near Midland, Texas, Owned By Parsley Energy, One Of The Biggest Producers In The Permian Basin.

Companies whose wells appear to lag behind forecasts, according to the analysis, include Pioneer Natural Resources Co. and Parsley Energy Inc., two of the biggest oil and gas producers in the Permian Basin of West Texas and New Mexico. The reviews didn’t include some leading producers, such as Exxon Mobil Corp. , because they didn’t make shale-well projections.

Pioneer, Parsley and several other companies disputed the findings, saying the third-party estimates used by the investigators differ from their forecasts on key points such as the likely lifespan of shale wells.

Some companies, including major North Dakota producer Whiting Petroleum Corp. , acknowledged the forecasts can be unreliable and said they were moving away from providing such estimates.

Another North Dakota driller, Oasis Petroleum Inc., said the projections it provided in investor presentations were estimates made as it tested drilling in vast tracts, including areas it has since abandoned. “It’s not a science,” said Richard Robuck, the company’s treasurer. “It’s more of an art.”

Few U.S. shale companies disclose exactly how they make their forecasts—the systems they use and the assumptions they make to estimate well-by-well production—or whether their projections from years ago hit the mark. The fact that many have missed is an open secret in the industry.

“I certainly expect many of today’s estimates will turn out to have been pretty optimistic,” said Francis O’Sullivan, director of research for the MIT Energy Initiative, which has examined shale forecasting. He said the complex geology of shale basins and assumptions based on a small number of wells could make forecasts unreliable. “There is profound variability in the performance of these wells,” he said.

Schlumberger Ltd. , the oil-field-services giant, reported in a research paper that secondary shale wells completed near older, initial wells in West Texas have been as much as 30% less productive than the initial ones. The problem threatens to upend growth projections for America’s hottest oil field, the company said in October.

Oil engineers and reserves specialists say existing data suggests there is a more accurate way to model well output. Operators, they say, must use more conservative assumptions about how quickly production will decline and how many wells can be drilled in a given area. Operators also should avoid making forecasts without a sufficient sample size of wells, they say.

Flawed forecasting doesn’t mean U.S. oil output is about to drop. Shale wells reach peak production quickly and rapidly decline, so companies are constantly drilling new wells. But if thousands of shale wells produce less over their lifetimes, companies will reap less of a long tail than anticipated, requiring them to spend more to sustain output and making it harder for them to reach profitability.

Shale companies have attracted huge amounts of capital from Wall Street over the past decade. So far, investors have largely lost money. Since 2008, an index of U.S. oil-and-gas companies has fallen 43%, while the S&P 500 index has more than doubled in that time, including dividends. The 29 companies mentioned in the analysis have spent $112 billion more in cash than they generated from operations in the last 10 years, according to data from FactSet, a financial-information firm.

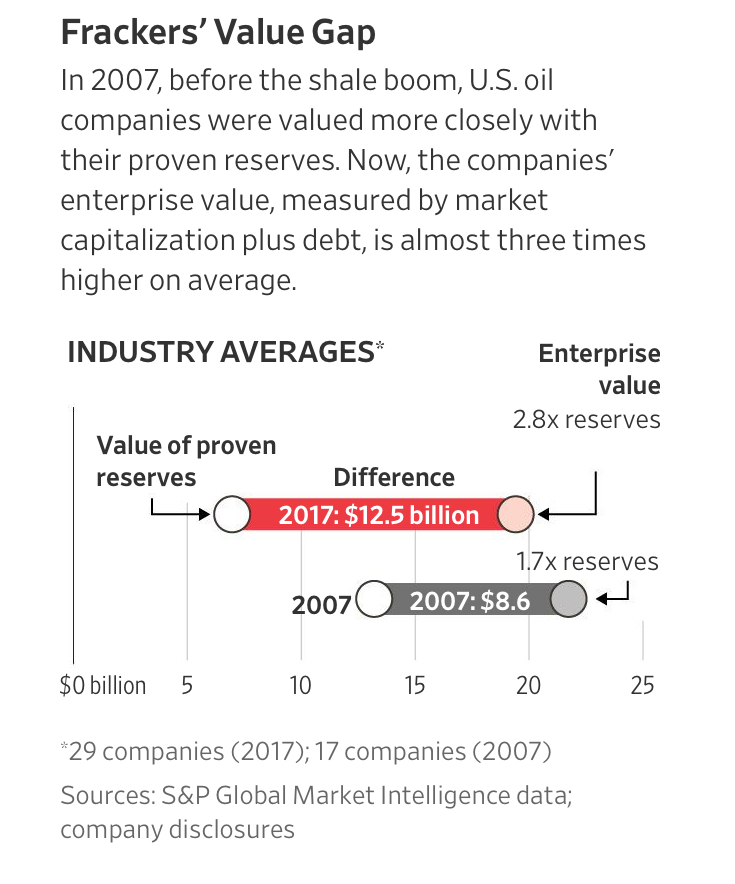

All oil companies are required to file estimates of total proven oil reserves with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Those estimates, governed by strict rules, generally only capture future reserves companies plan to tap in a five-year period. As the fracking boom intensified, many exploration and production companies looked for a way to persuade investors to value their prospects outside of that five-year window.

Shale companies began touting a metric known as estimated ultimate recovery, or EUR, in investor presentations. The estimates, often represented graphically by what is known as a type curve, project how much oil and gas wells are likely to produce over several decades, including the rate of decline.

The practice of promoting EURs became widespread after oil prices crashed in 2014 and producers, many in need of capital infusions from Wall Street, talked up their prospects. Wall Street’s valuation of many shale companies, which had been closely tied to the value of their proven oil and gas reserves, began diverging.

At the end of 2007, the companies in the investigators’s well analysis that existed at the time had an enterprise value, measured by market capitalization plus debt, of about 1.65 times the value of their proven reserves, according to company disclosures and S&P Global Market Intelligence data. Ten years later, that multiple had risen to more than 2.5 times, even though oil prices were much lower. Last year, the enterprise value of the 29 companies in the analysis was $360 billion higher than the value of their proven reserves.

EUR estimates from many companies were grounded on two assumptions: that they could pack wells closer together, squeezing more value from the land they leased, and that they could replicate their best early wells. The results to date suggest those assumptions were often wrong.

The independent analysis involves public data that at times gives an incomplete picture of well performance. North Dakota reports oil and gas production by well, but Texas does so only by land parcel. Third-party data providers must extrapolate to make up for that, meaning their data may not be as precise as well-level data maintained by companies.

Journalists relied primarily on figures from Rystad Energy, but consulted with several other third-party providers, including Oseberg Inc. and BLR Digital LLC, whose data pointed to similar conclusions. Those providers forecast well output over several decades based on early, publicly reported production data, taking into account typical decline rates.

Some Companies, Including Major North Dakota Producer Whiting Petroleum, Acknowledge Individual Well Forecasts Can Be Unreliable. A Whiting Facility Near Williston, N.D.

When oil prices plummeted around 75% between 2014 and 2016, to below $30 a barrel, many shale companies used EUR estimates to try to persuade investors that the sector remained a strong place to put their money.

The production forecasts made by many companies were “dangerous” because they were based on a small population of wells, and the performance of individual wells varies significantly, said Norman MacDonald, a natural-resource specialist at asset manager Invesco Ltd.

“Companies were able to high-grade the numbers, show those to Wall Street, and the stock price went up accordingly,” said Mr. MacDonald, a portfolio manager who has urged shale companies to prioritize profits over production growth. “Geology doesn’t line up with Excel spreadsheets too well, unfortunately.”

In September 2015, Pioneer Natural Resources, based in Irving, Texas, told investors that it expected wells in the Eagle Ford shale of South Texas to produce 1.3 million barrels of oil and gas apiece. Those wells now appear to be on a pace to produce about 482,000 barrels, 63% less than forecast, according to the Journal’s analysis.

An average of Pioneer’s 2015 forecasts for wells it had recently fracked in the Midland portion of the Permian Basin suggested they would produce about 960,000 barrels of oil and gas each. Those wells are now on track to produce about 720,000 barrels, according to the Journal’s review, 25% below Pioneer’s projections.

Pioneer disputed the conclusions, noting that it assumes its wells will produce for at least 50 years, while Rystad Energy uses 30 years in its forecasts. Pioneer also assumes its well productivity will fall off at a slower rate than the 7% final decline rate Rystad assumes.

“We find it is simply impossible to compare the numbers due to the methodological differences,” a Pioneer spokesman said.

Forecast Disparity

Adjusting for those factors doesn’t fully make up for the disparity in production forecasts. If Pioneer’s wells produce for 50 years and decline at 5% annually, its current production trajectory would still be nearly 12% below the company’s forecast of 849,000 barrels of oil and gas in the Permian, according to the Journal’s analysis. In the Eagle Ford, estimated production would increase only slightly to 498,000 barrels, or 62% less than the company projected.

A spokesman for Pioneer said problems in the Eagle Ford in 2015 were “widely known,” and the data shows the company’s well performance has improved.

While it is difficult to know how long shale wells will remain productive, assuming tens of thousands of them will pump for 50 years without costly interventions to keep them flowing is extremely optimistic, according to specialists on reserves.

The oldest case study to date is in the Barnett shale in and around Fort Worth, Texas, where modern fracking began about 20 years ago. Researchers at the University of Texas and Rice University predicted that many wells in the region, which primarily contains natural gas, won’t even produce for 25 years. About 73% or more of the total output of wells will come in the first decade, with little value coming after 20 years, the researchers said.

The decline rates of as low as 5% that some shale companies have adopted for their wells are optimistic, some academics and industry leaders say.

Recent studies by Rystad and analytics firm Wood Mackenzie Ltd. found that a range of 12% to 16% was the most common decline rate after about five years.

In 2014, Parsley Energy, an Austin, Texas-based producer, told investors its average well in the Midland section of the Permian Basin would produce 690,000 barrels, according to a review of Parsley’s quarterly earnings presentations. By 2015, its estimates averaged 1,050,000 barrels.

Parsley is on track to miss its Midland well forecasts for every year from 2014 to 2017 by an average of 25%, according to the Journal’s analysis.

“Responsible evaluation of the data shows that Parsley’s historical well production has been consistent with expectations set forth in our public materials,” said a Parsley spokeswoman.

When calculating its estimates, Parsley includes other valuable hydrocarbons that come out of wells, such as ethane. In its analysis, Rystad doesn’t include those hydrocarbons, known as natural gas liquids, because they aren’t accurately captured in available public data.

Parsley declined to comment on how much of a boost its estimates get from such liquids. In recent years, the average increase in barrels from including the byproducts amounts to 10% to 18% in the Midland basin, according to third-party estimates.

Mark Papa, Chief Executive Of Centennial Resource Development, Said His Company Avoids Well Forecasts Because They Create An ‘Illusory Picture’ Of A Company’s Prospects.

Mark Papa, a fracking pioneer and chief executive of Centennial Resource Development Inc. in Sugar Land, Texas, said his company avoids forecasts because they create an “illusory picture” of a company’s prospects. “A lot of type curves present a well’s potential under perfect conditions,” he said. “But in reality, the majority of the wells don’t turn out that way.”

Some companies said they were aware of flaws with the forecasting method and how it has been used, but that they provided the numbers to meet demands from analysts and short-term investors such as hedge funds. Some said that if they didn’t, their stock would underperform peers that made optimistic claims.

“You have to make projections,” said David Lancaster, chief financial officer of Matador Resources Co., a top Permian driller. He said companies should revise forecasts that appear to be off target, disclose production ranges rather than specific estimates and avoid screening out poorly performing wells.

Matador’s average well in the Permian’s Delaware Basin is on track to outperform forecasts in all three years the company provided them, according to the Journal’s analysis.

Whiting Petroleum Is De-Emphasizing Its Per-Well Production Estimates At The Direction Of Its Chief Executive, Bradley Holly.

Denver-based Whiting Petroleum is de-emphasizing its production estimates at the direction of its chief executive, Bradley Holly. Mr. Holly, who became CEO in November 2017, said the company is now more focused on generating cash, lowering debt and maximizing a well’s returns early in its life.

“Your return will really be made in the first two to three years,” he said.

One reason thousands of early shale wells aren’t meeting expectations is that many companies extrapolated how much they would produce from small clusters of prolific initial wells, according to reserves specialists. Some also excluded their worst-performing wells from the calculations, which is akin to eliminating strikeouts when projecting a baseball player’s batting average.

“There are a number of practices that are almost inevitably going to lead to overestimates,” said Texas A&M University professor John Lee, an expert on calculating oil and gas reserves.

Many reserves specialists have advised companies to provide a potential range of outcomes based on their internal analyses, a common practice in statistics that better accounts for uncertainty.

Academic research has suggested that data from at least 60 wells, producing for six months or more, would be needed for accurate forecasts. Yet some companies and analysts have made predictions based on fewer than 10 wells.

At a July presentation Mr. Lee gave in Houston about techniques that could produce more accurate shale forecasts, one participant stood up and challenged the engineers in attendance.

“Why aren’t we doing this?” the man asked several times, according to Mr. Lee and two other people who attended the meeting.

“Because we own stock,” replied another engineer, sparking laughter.

Updated: 6-10-2019

Frackers Scrounge for Cash as Wall Street Closes Doors

With traditional financing options dwindling, shale companies explore costlier alternatives.

Shale drillers are scrambling to raise cash as financing from Wall Street dries up.

The companies behind the U.S. fracking boom are turning to asset sales, drilling partnerships and other alternative financing to supplement their cash flow. These forms of funding often come with higher interest rates or carry other downsides, such as giving outside investors a hefty share of future oil and gas production, but are gaining traction as drillers face dwindling access to traditional sources of capital.

Fracking companies are feeling intense pressure from investors to live within their means after years of losing money. Most are still struggling to generate positive returns, a situation now compounded by weak oil prices. The U.S. crude benchmark is down nearly 19% since its April peak to about $54 a barrel Friday, raising the prospect that banks could pull back on companies’ lines of credit, many of which are tied to the value of their oil reserves.

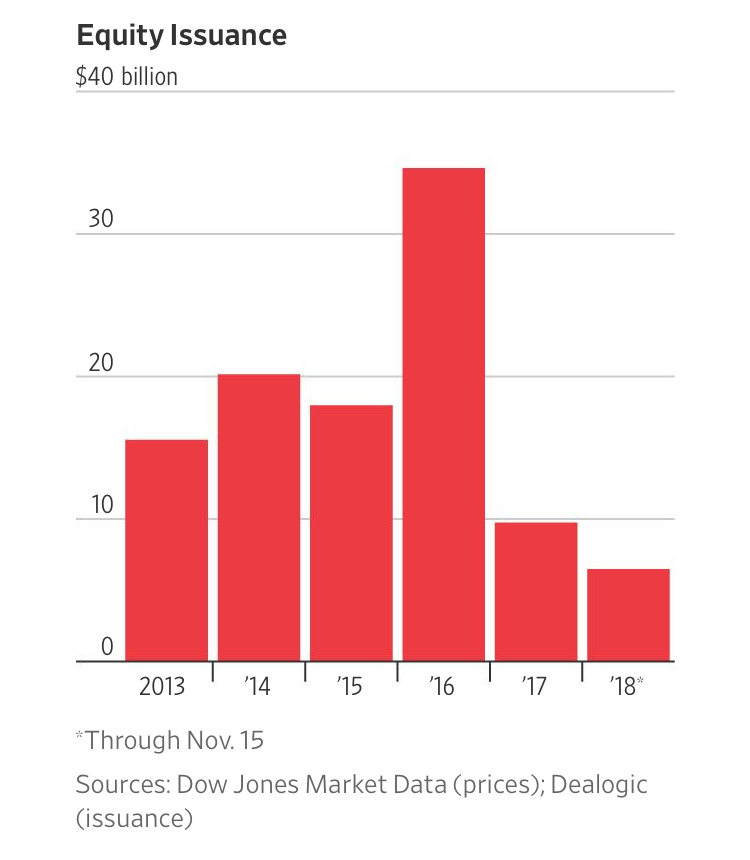

Producers have mostly avoided borrowing in 2019 as they aim to show investors they are sincere about austerity. There hasn’t been an issuance of public equity by a fracking company since late last year, the longest gap since 2014, consultant Rystad Energy said. Meanwhile, bond issuances by shale companies are on pace to reach their lowest levels in more than a decade, according to data analytics firm Drillinginfo.

Only a tenth of large shale companies reported positive cash flow in the first quarter of 2019, according to a Rystad Energy analysis of 40 drillers. To sustain or increase production, the companies need to drill new wells—and to drill, they need money, analysts say.

The financing crunch threatens shale companies’ ability to maintain the production boom that has made America the world’s top oil producer and ratchets up the pressure to consolidate. A wave of bankruptcies is also a possibility should oil prices remain low, say analysts.

Some shale companies are dipping their toes in the junk bond markets, where interest rates have begun to soar, lenders say. Others are exploring drilling joint ventures in which an investor pays for the cost of drilling a group of wells in exchange for most of what is pumped early on, often a well’s most productive time.

Pioneer Natural Resources Co., one of the top shale companies in the Permian Basin of Texas and New Mexico, is looking to pay for drilling some of its less promising acreage through such a partnership, known in the industry as a drillco. Scott Sheffield, Pioneer’s chief executive, said in an interview that the company is seeking the financing for wells it would otherwise not drill for 10 to 15 years.

“It’s a way to keep acreage and monetize it,” Mr. Sheffield said. Describing the current climate for shale companies, he said, “It’s been a 10-year run and the equity markets are closed, and the investors want return to themselves.”

Producers have been forced to get creative about financing because Wall Street began shutting off the cash spigot last year after frackers routinely failed to turn a profit over the last decade. In 2018, new bond and equity deals dwindled to their lowest level since 2007. Companies raised about $22 billion from equity and debt financing last year, less than half the total in 2016 and almost one-third of what they raised in 2012, analytics firm Dealogic said.

More than a dozen of the largest U.S. shale producers still have access to traditional bank financing, lenders say. But smaller companies, whose output makes up the vast majority of shale production, are finding it hard to secure inexpensive cash infusions.

Nearly 30% of respondents to a March 2019 survey of producers and financial institutions by law firm Haynes and Boone LLP said drillers are planning to raise debt outside capital markets this year. About 18% of respondents said drillers are planning to enter into joint ventures.

“To get investors back to the sector, they need cash flow now,” said Rob Thummel, a portfolio manager for Tortoise Capital Advisors, which manages about $21 billion in assets. “They’re going to give up a lot in order to do that.”

Because shale wells tend to produce prodigiously early on, but then rapidly decline, companies that can’t afford to add new wells will see their oil reserves fall fast, said Todd Dittmann, head of energy at Angelo Gordon & Co., which manages about $33 billion across a range of alternative-asset strategies, including oil and gas.

“By our math, very few oil-and-gas companies, 15% or less, can really achieve capital discipline,” Mr. Dittmann said. “This leaves most public companies with hope strategies and little more, hoping insufficient capital spending won’t lead to near-term production declines.”

Shale companies also are stepping up asset sales to generate cash. They sold about $18 billion in nondrilling related assets in 2018, including pipelines and water-disposal systems, the most since early 2015, Drillinginfo said. Proceeds from the transactions accounted for nearly half of the new capital the companies raised last year.

Investor appetite for buying shale companies’ corporate bonds has dwindled, lenders say, leading some companies to explore the junk bond market, where costs are rising. Some alternative lenders are offering interest rates as high as 13%, as much as 7% higher than lower yield bonds, according to people who lend to oil-and-gas companies.

Those soaring costs are among the reasons more shale companies are exploring drillco partnerships this year, analysts say.

Fracking companies have sometimes favored these arrangements because they can be a way of securing funding that doesn’t appear as debt on their balance sheet. The partnerships also can allow companies to meet obligations to drill land they have leased, or drill some holdings sooner. But the cost is considerable: Companies give up returns from a well’s early years, when it will produce the most, until the outside investor reaps a certain return, often 15% or more.

Tom Loughrey, president of oil-and-gas consulting firm Friezo Loughrey Oil Well Partners LLC, said drillcos make sense if oil prices are high. But if prices are lower, it takes more time for the outside investors to make their money, and producers are left with returns from the well’s later life, when production has declined significantly.

“That becomes a high cost of capital,” Mr. Loughrey said.

Updated: 1-10-2020

Oil Producers Are Setting Billions of Dollars on Fire

Massive amounts of natural gas are being burned to make way for oil production. Unless the incentives are changed, the harmful practice will become even more common in the U.S.

Relatively clean and flexible, natural gas has been described as “the champagne of hydrocarbons.” Lately, though, energy companies are treating it about as sparingly as a team that just won the World Series.

Tremendous quantities are intentionally burned off to make way for oil production. The problem is likely to get worse in the U.S., the number four flarer of gas behind Iran, Iraq and world-leader Russia. It is more than an issue of waste: Flaring may be responsible for 1% of global greenhouse gas emissions according to Raymond James.

Even as more and more gas gets supercooled and shipped around the world in expensive, liquefied form, an estimated 5.1 trillion cubic feet of gas was flared world-wide in 2018, according to The World Bank—equivalent to the combined consumption of France, Germany and Belgium.

Why waste so much valuable fuel? Because it is often an unwanted byproduct of an oil well, and it isn’t worth enough to sell.

Geography determines whether it is worth something or not. For example, the big oil fields of eastern Siberia or Algeria’s Sahara desert are so far from end markets that the investment to process, gather and transport the associated gas produced would exceed its market value. In other cases, though, poor planning and regulation are as much to blame. Riccardo Puliti, Global Director, Energy and Extractive Industries at The World Bank, notes that there is a “huge potential market” for gas in densely-populated Iraq, which is wracked by power shortages. The bank estimates that establishing a regulatory framework for selling the gas could bring $21 billion in investment to the country.

Unlike Iraq, the U.S. has a robust legal framework and enough natural gas pipelines to reach the moon. But America also has incredibly cheap gas, which encourages waste. Building more gas pipes to the Permian Basin, the center of America’s oil patch, is less of a priority than completing oil pipelines. Meanwhile, connecting them to outlying areas like the Bakken region in North Dakota is uneconomical at any price.

This results in some strange anomalies. Last year the price of gas at the Waha Hub in Texas reached negative four dollars per million British thermal units while gas in the other parts of the country was around $2.50/MMBtu. In other words, companies with natural gas on their hands in that region had to pay people to take it. Prices would still be negative if the local regulator, the Railroad Commission of Texas, hadn’t greatly expanded the amount of gas that could be burned off. Last year a subsidiary of pipeline company Williams claimed in a lawsuit that the commission allowed a firm that could have used its pipelines to flare gas instead.

Geography causes the problem, but geology is making it worse. Shale oil wells have much steeper decline rates than conventional ones. This means that the volume of crude they produce after the first year drops sharply, but their associated gas volumes fall more gradually. The furious pace of drilling needed to keep shale oil production stable or rising results in more and more unwanted gas.

Burning gas releases carbon dioxide, but simply releasing it into the air would be worse because flammable methane is a far more potent greenhouse gas. Flaring produces other types of pollution too, says Audrey Mascarenhas, chief executive officer of Questor Technology. Questor produces machines that safely process over 99% of methane and volatile organic compounds at oil wells. It has been used widely in Colorado, which has stringent anti-flaring rules.

Even in less environmentally aware places, a lot of gas might be harnessed. For example, microturbines could generate electricity using waste gas for energy-intensive oil field equipment. Most creative are projects that use such power to run energy-intensive computers that do tasks like mining bitcoin or other calculations and then beam the results elsewhere by satellite.

“It’s easier to move data than a remote commodity,” explains Chase Lochmiller, co-founder of Crusoe Energy Systems, which runs several such computers.

Data may be the new oil, but such initiatives remain small. Proper incentives could tip the balance. For example, even as so much gas is being flared in the Permian, German utility RWE just christened a large solar facility there to help meet booming local electricity demand. While Texas is sunny, solar farms are made possible by subsidies. So are even more expensive technologies like carbon sequestration—physically storing CO2. Ms. Mascarenhas laments the fact that the cheapest solutions to mitigate global warming such as finding alternatives to flaring are mostly being ignored.

“We pick the hardest things first because they sound shiny and sexy.”

Few things irritate oilmen as much as taxes and red tape but, with enough gas being wasted to supply most of Western Europe, there is money to be made in finding uses for it. Forcing them to pay up for flaring gas and helping them profit from capturing it could help them do well while doing the earth a lot of good.

Fracking’s Secret Problem—Oil, Fracking’s Secret Problem—Oil,Fracking’s Secret Problem—Oil,Fracking’s Secret Problem—Oil,Fracking’s Secret Problem—Oil,Fracking’s Secret Problem—Oil,Fracking’s Secret Problem—Oil,Fracking’s Secret Problem—Oil,Fracking’s Secret Problem—Oil, Fracking’s Secret Problem—Oil,Fracking’s Secret Problem—Oil,Fracking’s Secret Problem—Oil,Fracking’s Secret Problem—Oil, Fracking’s Secret Problem—Oil,

Related Article:

Frackers Fret As Trump Tweets For Lower Oil Prices (GotBitcoin?)

Your questions and comments are greatly appreciated.

Monty H. & Carolyn A.

Go back

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.