A $4 Trillion Problem For Investors: The Fed’s Shrinking Portfolio (#GotBitcoin?)

“It’s changing the psychology of investors,” said Scott Minerd, chief investment officer at money manager Guggenheim Partners LLC. A $4 Trillion Problem For Investors: The Fed’s Shrinking Portfolio

He noted that the Fed is reducing its bond portfolio at the same time the Treasury is issuing more bonds to fund large federal budget deficits.

The combined effect—more than $1 trillion of Treasury and mortgage-debt securities hitting the market—is crowding out capital for other types of investments, he said.

Some investors blame the stock market’s volatility on the Federal Reserve shrinking its bond portfolio. But the critique puzzles Fed officials and some economists because there is little evidence of turmoil in the two markets where the central bank actively intervened: Treasurys and mortgage debt.

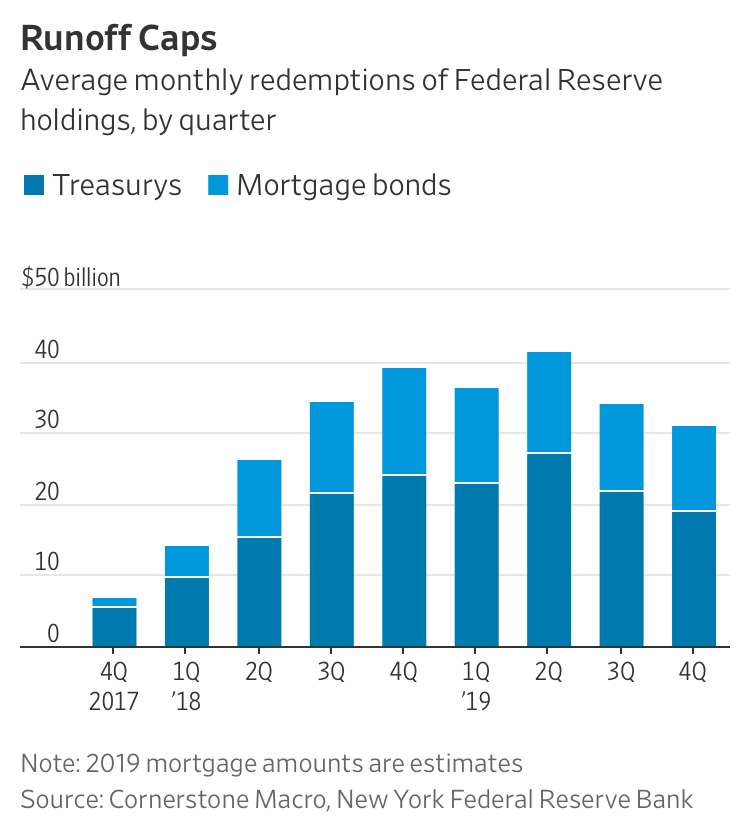

The Fed is shrinking its $4 trillion portfolio by allowing Treasury and mortgage securities to mature without replacing them. Up to $50 billion worth is allowed to expire every month under the plan, though the actual amounts have been closer to $40 billion in recent months.

Markets barely blinked when the Fed announced its move in 2017. But in the last few months, a number of prominent investors, including Stanley Druckenmiller, have said the portfolio runoff is a big factor behind the return of market volatility. With stocks gyrating, President Trump said he wanted the Fed to slow or stop the moves.

However, many economists and Fed officials, in public comments and interviews, said they don’t think the central bank’s portfolio runoff is a major culprit in the market volatility. Their evidence: Long-term interest rates have gone down of late, not up, reflecting plentiful demand for new Treasury debt. And the Fed’s bond redemptions are much smaller than the amount of new Treasury debt needed to finance rising deficits.

Yields on 10-year Treasury notes are down to near 2.75% from near 3.25% in November, when market volatility picked up.

The Fed’s bond-buying program, launched in response to the financial crisis a decade ago, aimed to stimulate the economy by holding down long-term interest rates. Lower rates can push investors to buy riskier investments such as stocks, corporate bonds and other financial assets, and thus boost their prices.

Those who are worried now about the runoff believe that as Fed bond purchases successfully encouraged investors to buy riskier assets, so too should the reverse of the program discourage risk-taking. Investors didn’t respond right away to the runoff, they argue, because markets’ moves are often nonlinear.

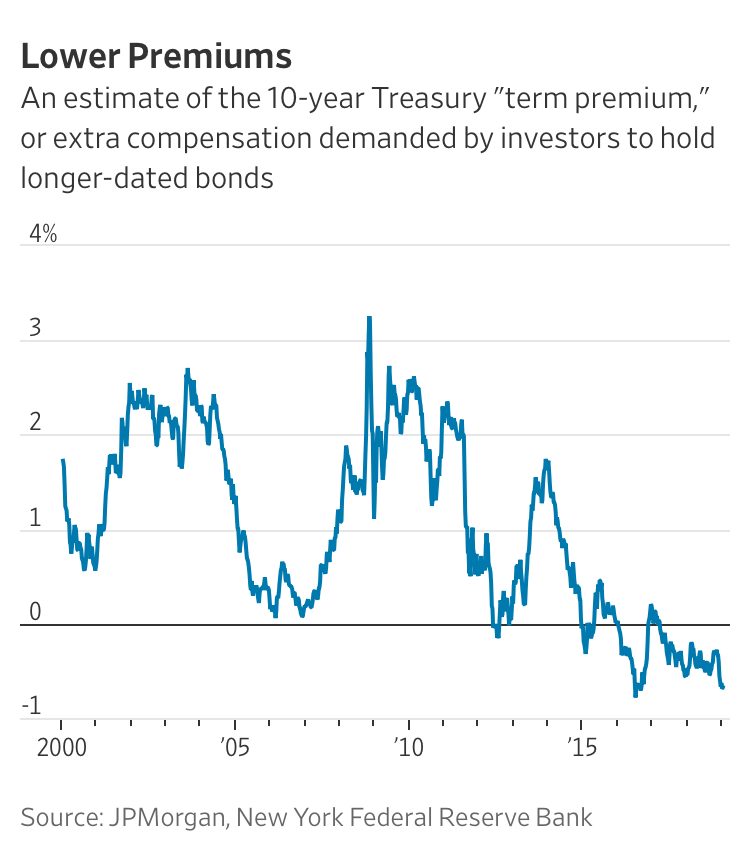

Analysts at JP Morgan estimate each $1 trillion in Fed bond buying during and after the financial crisis reduced the term premium—the extra yield investors get for holding a long-term bond—by 0.15 to 0.2 percentage point.

Shrinking the Fed’s holdings should in theory boost the term premium because it increases the supply of bonds that private investors must purchase. Greater supply can send bond prices lower, and rates move in inverse relationship to prices.

But various measures of the term premium show it is no higher today than when the runoff began.

“It’s hard to fathom the [Fed] balance sheet is having some dramatic effect,” Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari said in a Jan. 17 interview.

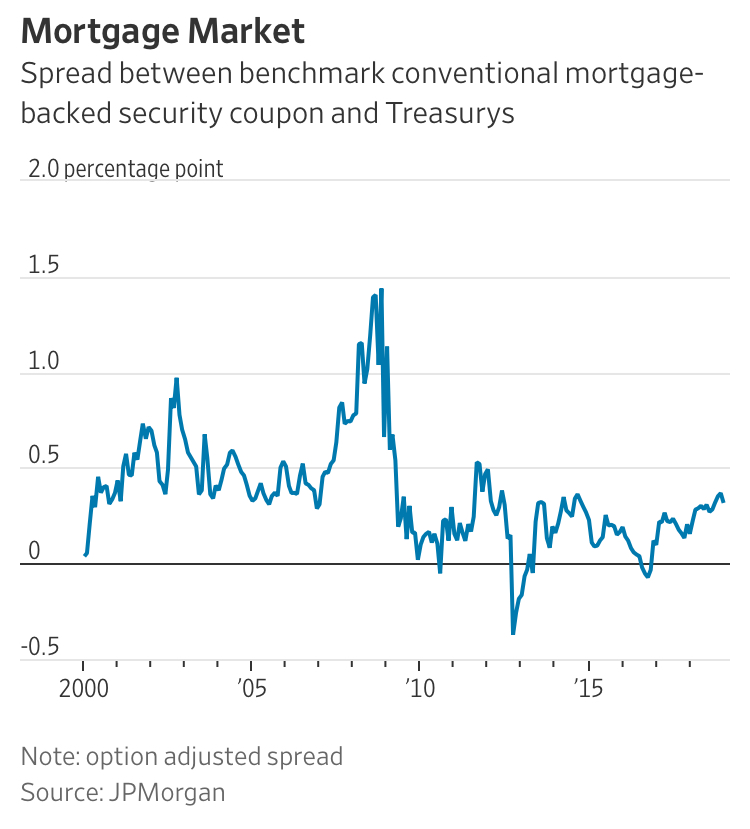

Likewise, the mortgage market hasn’t witnessed a notable widening of interest-rate spreads, which is the premium investors demand for holding riskier mortgage securities instead of Treasury securities.

The Fed has reduced its mortgage bondholdings by around $140 billion. Some increase in mortgage bond yields relative to Treasurys occurred shortly after the Fed began reducing its holdings in October 2017, but spreads remain well within their historical average. Rates on 30-year mortgages, at around 4.5%, are down from near 5% in November.

“The mortgage market was the first market to react to the runoff,” said Matthew Jozoff, JPMorgan’s mortgage-debt strategist, with bond spreads widening against Treasurys in early 2018. While markets turned volatile in the fourth quarter of last year, “mortgages have actually done fine,” he said.

It is hard to separate how much the balance sheet runoff is affecting financial conditions versus that of the Fed’s rate increases. The central bank lifted its benchmark rate four times last year in quarter-percentage-point increments, that last one in December, to a range of between 2.25% and 2.5%. The Fed is expected to keep rates steady at its two-day meeting ending Wednesday, where officials also are likely to discuss how long they will need to continue the runoff.

Joseph Lavorgna, chief economist at French corporate and investment bank Natixis , estimated the runoff could be equivalent so far to a 0.5 percentage point increase in the Fed’s short-term rate, using a model developed by the Atlanta Fed to estimate the stimulative effect of the Fed’s bond buying.

Mr. Kashkari said it is possible that some investors have grown uneasy about the bond portfolio because of the signal it sends about the central bank’s broader mind-set about interest rates and the economy. A strong commitment to running down the portfolio could be seen as a hawkish signal that the Fed has a tolerance for higher rates and a slower economy.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell sought to ease such fears earlier this month. He said the Fed didn’t believe the runoff “is an important part of the story of the market turbulence that began in the fourth quarter.” He added, “If we reached a different conclusion, we wouldn’t hesitate to make a change.”

The majority of private economists surveyed by The Wall Street Journal earlier this month agreed with his assessment. Nearly 52% said the policy was “of marginal importance or having no effect” on financial conditions, compared with less than 44% who said it was somewhat important. Just 5% said it was very important.

Another way, in theory, that the runoff might result in lower asset values and tighter financial conditions would come from removing reserves in the banking system that the Fed created when it bought the bonds in the first place. Reserves are the deposits of money that banks keep with the Fed and are emblematic of how flush the financial system is with funds.

But this channel also doesn’t look like it is having a big effect. Reserves have been declining since 2014, yet the stock market rose over much of the last five years. Reserves stood at $1.6 trillion last week, down from a high of $2.8 trillion in 2014.

There is also little evidence that fewer reserves in the banking system has hurt lending growth, which reached a multiyear high in the fourth quarter.

“The notion that somehow there is less Fed ‘liquidity’ spilling into markets is evocative language, but also utterly meaningless,” said Michael Feroli, chief U.S. economist at JPMorgan. “As was the case many years ago when concerns were rife that the Fed was ‘flooding the world with dollars,’ such hydraulic analogies are ultimately hogwash.”

Related Articles:

Treasury Expects To Issue Over $1 Trillion In Debt In 2018 (#GotBitcoin?)

Foreign Buying of U.S. Treasurys Softens, Unsettling Financial Markets (#GotBitcoin?)

U.S. Treasury Plans Increased Auctions to Fund Looming Trillion-Dollar Deficits (#GotBitcoin?

Debt-Market Slowdown Troubles Investors (#GotBitcoin?)

Your questions and comments are greatly appreciated.

Monty H. & Carolyn A.

Go back

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.