Blood Pressure, Baby’s Pulse, Sperm Potency: Home Health Devices Are Tracking More Than Ever (#GotBitcoin?)

Wearables and other inexpensive products and services can now extract detailed information about our bodies—so how will their makers handle all that data? Blood Pressure, Baby’s Pulse, Sperm Potency: Home Health Devices Are Tracking More Than Ever

Companies are planning to get personal—very personal—at the 2019 CES technology show this week in Las Vegas.

The annual event for showcasing the latest in consumer technology will feature self-driving shuttle buses, 5G wireless hubs, artificially intelligent ovens and more, but exhibitors will also be displaying their ability to intuit deeper health data directly from users, often with cheap, even wearable, devices.

On display will be a wristband that checks blood pressure, a forehead sleep sensor that detects if you stop breathing and a band for a woman’s stomach that tracks an unborn baby’s heart rate and in-utero kicks. There is a breath monitor to tell you more about your digestion and an at-home sperm test that produces a live video of your sample.

In 2019, 511 companies at the show registered as exhibitors in the digital health category, up from 472 last year, a spokeswoman from the Consumer Technology Association said.

“A lot of these companies are moving full steam ahead in terms of collecting data and using it to help the personalization of the customer,” said Anshel Sag, an analyst with Moor Insights & Strategy. “I just got an email about a bladder monitor.”

Helping to drive this shift in the market are both the improvement in sensor accuracy, which increases a company’s likelihood of getting a device cleared by regulators, and the advances in data processing.

“All these things have matured where they don’t feel like they’re proof of concept,” said Mr. Sag. “You’ll see more of these devices giving users more actionable things to do based on their data.”

Yet this proliferation of devices that collect potentially sensitive health data comes as last year’s tech news remains fresh in consumers’ minds: 2018 was the year of Facebook’s Cambridge Analytica scandal, Europe’s sweeping General Data Protection Regulation privacy rules, contentious congressional hearings for tech executives and the revelation of multiple major security breaches.

It is an interesting time for a tech company to be asking for a urine sample.

A Measuring Device Called Owlet Smart Sock, Which Checks Blood Pressure, Heart Rhythm And Blood Oxygen Levels, Is Attached To The Foot Of A Baby Doll At The Child & Youth Expo In Cologne, Germany, Sept. 14, 2017.

“I think it’s on everybody’s minds right now,” said Kurt Workman, co-founder and chief executive of Owlet. The startup previously launched a wearable device for babies, and this year it will unveil the stomach band for expectant mothers.

Owlet aims to create a device that could eventually be used as an at-home monitor for high-risk pregnancies.

Currently, purchasers of the company’s smart baby-sock device, which monitors oxygen and heart rate, grant permission to share their data anonymously, for research purposes, but Mr. Workman said there is no sharing personal data with third parties. When Owlet launches its new band in Europe later in 2019, it will be subject to GDPR rules, he notes.

“The customer owns the data. It’s theirs. It’s their child’s heart beat,” said Mr. Workman. “We’re not, like, selling to pharmaceutical companies.”

The consumerization of health care could lead to faster and lower-cost care in the long term but, according to Julie Ask, an analyst with market research firm Forrester, “Nobody’s really benefiting yet.”

As for the current limitations, she said, privacy is one of several.

“There isn’t an open ecosystem of data exchange,” Ms. Ask said. There may be one-off apps or services, but there is nothing broader reaching. “I have no way to share my data with my doctor, I have no way of giving it to him in a way that’s encrypted and that’s private.” And many doctors might not want it, she added, preferring their own measurements instead.

She also said healthy people will continue to represent the biggest adopters of these consumer health products, especially fitness wearables with ever-deeper health data capabilities.

“More often than not, the people wearing more advanced devices aren’t the ones that need them,” said Ms. Ask.

For Omron Healthcare, which this year is launching an FDA-cleared wrist wearable that can take your blood pressure, all the collected data is stored in a system that complies with federal standards for protecting health information and medical records, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, also known as HIPAA.

Ranndy Kellogg, Omron Healthcare’spresident and CEO, said the company doesn’t share data, anonymized or otherwise. Users do have the option of sharing collected medical information with their doctor or with Apple Health through the company’s app.

“You have to start the sharing,” said Mr. Kellogg. “We only enable it when we get the handoff from you.”

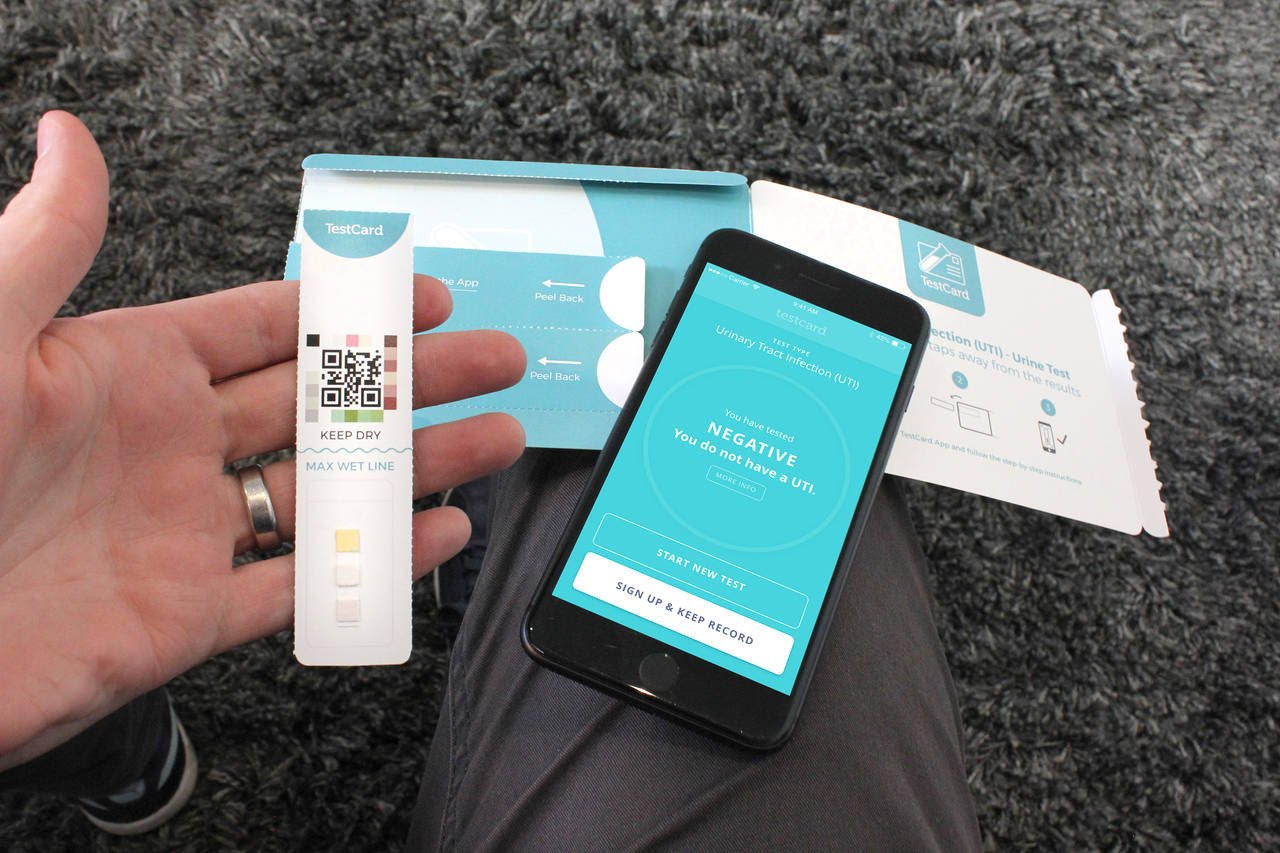

Urine-Test Kits Developed By U.K.-Based Company Testcard.Com Can Detect A Urinary Tract Infection, Pregnancy And Ovulation.

For TestCard.com, a UK-based company that is launching a series of at-home urine tests this year, users will be able to share their results with providers if they choose to.

“It’s an opt-in rather than an opt-out,” said Andrew Botham, the company’s co-founder. “We’ll be collecting results, not information. We won’t know the name or the contact details of an individual.”

The test kits, which Mr. Botham expects to arrive in the U.S. by summer, come with a row of test strips and an app that turns a smartphone camera into a scanner. They can detect a urinary tract infection, pregnancy and ovulation, Mr. Botham said.

“We need to go back into people’s homes,” he said, explaining how an at-home service like this could benefit people who might otherwise avoid the doctor.

The maker of the FDA-cleared YO home sperm test is launching an updated version at CES. It will include a quality score, comparing a user’s test results against data from the World Health Organization. The company’s promotional materials say it is less awkward and more private for men to collect a sample at home.

It isn’t a replacement for clinical infertility treatment, but it is a first step, said Eric Carver, a general manager with Medical Electronic Systems, the test’s developer. “It’s much more invasive to test the woman and it’s very easy to test the man and our app gives them an assessment.”

As for the data, Mr. Carver said the company doesn’t store it.

“After you download the app, you could be completely disconnected from the internet and still run our test,” he said. “We’re not building a databank of people’s sperm quality.”

Go back

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.