Home Flippers Pulled Out of U.S. Housing Market As Prices Surged (#GotBitcoin)

Real-estate firms recruit drivers to help them find derelict properties to buy and sell fast. Home Flippers Pulled Out of U.S. Housing Market As Prices Surged (#GotBitcoin)

Brandon Taylor delivers food for UberEats and Amazon, but he has recently taken on another job: scouting potential targets for a house flipper.

He is working for CORI, which hires drivers to identify homes on their routes that the real-estate firm can buy and quickly sell for a profit. Mr. Taylor has learned to spot telltale signs of a house ripe for a flip: piled-up mail, warning notices plastered on the doors, tall grass and abandoned cars in the backyard.

Companies buying up homes in gentrifying neighborhoods in places such as Atlanta, Chicago, and Charlotte, N.C., are enlisting fleets of drivers working for ride-share apps like Uber and Lyft.

They pay drivers to take pictures of dilapidated properties during their down time, betting that some owners of these homes will be eager to sell. Eric Richner, the 31-year-old co-founder of CORI, said he has about 100 drivers working for him but aims to have 1,000 by the end of the year.

Participants in the increasingly competitive house-flipping market say using drivers as their eyes and ears cuts down on time and money wasted cold-calling whole neighborhoods.

“It’s a great way to be able to reach areas that I can’t drive around town all day,” said Scott Sekulow, who runs a HomeVestors franchise in Atlanta that has hired several drivers. “You don’t need a lot to know the house needs repairs.”

House purchases are classified as “flips” when a property is bought and resold within one or two years of purchase. Buyers typically invest in upgrading homes to make them more valuable, before putting them back on the market.

Flipping has been a controversial practice, and some housing analysts believe it contributed to the housing bubble more than a decade ago. Back then, hoards of amateur investors lined up to purchase lots in new subdivisions in hot markets such as Las Vegas and Phoenix.

In recent years, however, the business has become more sophisticated: 40% of flips are now made by companies rather than by individuals, giving companies three times the market share they had during the last housing boom, according to research from property-data firm CoreLogic .

The recruitment of ride-hailing drivers to cover target-rich locations is the latest sign that house flippers are becoming more institutionalized and technology-driven.

This new union between temporary workers like ride-hailing drivers and property speculation isn’t as improbable as it might seem. As the institutionalization of house flipping has grown, so has the industry’s demand for cheap labor to help it expand further.

Companies are recruiting drivers through apps including DealMachine, which more than 400 house-flipping outfits use to gather leads, according to its chief executive, David Lecko. He got the idea after chatting with drivers in Indianapolis, where the company is based.

Drivers’ compensation varies by firm, from a sales commission to a fee for each productive lead. Atlanta-based CORI pays drivers up to $1,500 per referral that leads to a purchase and in some cases it pays for leads as well, Mr. Richner said. Mr. Taylor, who learned of the opportunity and began scouting in December, said he hasn’t made any referral money yet.

Krystal Polite, co-founder of the house flipper Be Polite Properties in Alamance County, N.C., hires drivers to find her deals in 20 states. She offers one or two dollars per approved lead, and 10% of net profit if a lead becomes a flip, she said.

“You kind of have to make it worth their while, because it can be a long time between when that deal comes in and when you actually close,” Ms. Polite said.

One of Mr. Sekulow’s top recruits is Jiri Emanovsky, who lives in midtown Atlanta. Mr. Emanovsky helps Mr. Sekulow recruit other Uber and Lyft drivers for the company, which is focused on properties valued at $200,000 or lower, he said. Mr. Emanovsky estimated about every 200 leads sent in should equal one deal, so if a driver sent in 600 a month, he or she eventually could earn an additional $3,000 or so in added income.

Still, it isn’t clear if anyone is getting rich as a house-flipping scout. Tyra Johnson-Morris, 35, who drives for Uber and Lyft in Chicago, said she has sent in more than 400 photos to CORI since January. She often asks ride-share customers about their neighborhoods and inquires about specific houses.

Even though none of her leads have become sales yet, she intends to keep doing it. “I understand real estate is a numbers game,” she said. “What do I have to lose? I’m driving around anyway.”

Updated: 5-26-2021

Fast-Cash House Flippers Flood Poor Neighborhoods In The U.S.

States and cities in the U.S. are cracking down on a niche in house-flipping known as wholesaling conducted by a flood of largely unlicensed middlemen lured in by YouTube tutorials and a torrid market.

Bearing fast cash, wholesalers can help distressed homeowners sell quickly, but have been accused of strong-arm tactics and misinformation. Unlike fix-and-flip investors, who take title to homes, renovate them and put them back on the market, wholesalers typically negotiate with homeowners just to put homes under contract and sell those contracts to flippers.

“I don’t buy houses. I solve problems,” said Scott Sekulow, who leads an Atlanta-area congregation of messianic Jews and bills himself as the Flipping Rabbi. He said clients come his way when they’re going through a divorce, can’t afford massive home repairs or run into other trouble. Sekulow said he can get them cash while also beautifying a neighborhood.

Hedge funds are paying top dollar for the contracts, he told a conference of prospective moguls: “When you can get in with them, they’re there paying stupid money.”

While the practice is legal when transparent, advocates for the poor say aggressive wholesalers dupe sellers with lowball offers.

Illinois, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Kansas and the city of Philadelphia proposed or passed regulations recently after complaints. The latter city acted in the fall after neighborhoods were overrun with “We Buy Houses” signs, and reports that hard-charging wholesalers wouldn’t leave houses without a signed contract.

“In my neighborhood in West Philly, I probably get three postcards a month from one of these guys,” said Michael Froehlich, an attorney with Community Legal Services of Philadelphia. “If you can get leads, you can dupe somebody into signing a contract for far less than fair-market value, and you can make $30,000, $40,000, $50,000 on a house.”

The wholesalers, typically entry-level investors who find off-market homes through cold calls or driving through neighborhoods, have been enabled by pandemic-era low interest rates and tight housing supply that have created record price appreciation.

The U.S. had only a 2.4-month supply of unsold houses in April, near a historic low. Prices make many unprofitable for investors, driving some wholesalers to scour working-class and poor neighborhoods to scare up deals. Fees for gathering contracts often run 10% or 15% of the sale price and can generate the wholesaler a $15,000 payday in weeks — although costs for Internet advertising and customer lists eat into those gross gains.

On a recent Monday night in Roswell, Georgia, around 50 wholesalers, flippers and investing neophytes turned out at a DoubleTree hotel for a meeting of the Atlanta Real Estate Investors Alliance. Sekulow, whose brother Jay was one of Donald Trump’s impeachment lawyers, was one panelist.

A second, Mike Cherwenka, calls himself the “Godfather of Wholesaling” and shares testimony on his website of performing in a male revue dance team. He left the life after embracing Jesus and beginning a real-estate career.

“Cash is king, and when you can just offer people cash and close within a week, you’ve got leverage, right?” said Cherwenka, still a muscular figure in a violet-hued sport coat. “People perk up and listen when you make an offer and you’ve got proof of funds right there.”

As discussion turned to the benefits of having a spouse involved in one’s real-estate business, Cherwenka’s wife, Tolla, used a game-show flourish to show off the couple’s book, “The Art of Becoming a Multimillionaire Real Estate Investor.”

“If you’d like one, it’s $20,” he says. “Hold one up there, babycakes.”

Wholesaling has been around for years, but hit the radar of real-estate data provider PropStream in a bigger way four years ago, said Rob Zahr, chief executive of parent company EquiMine in Orange County, California. PropStream’s database can help find homes that are abandoned, at risk of foreclosure or loaded with liens.

A single enthusiastically titled Facebook group — Wholesaling Houses with PropStream! — counts more than 41,000 members.

The “low-hanging fruit” of houses that just need a little upgrading are all gone, said Brian Dally, whose Atlanta-based finance company, Groundfloor, expects to fund up to $350 million in real-estate investments this year. What remain aren’t on listing services and need major overhauls.

“You need more scouts out there,” he said. About 40% of the company’s deals involve wholesalers.

Complaints, though, started mounting at legal aid societies for the poor as people flooded into the industry. Because wholesalers often don’t hold real-estate licenses, regulators have had little power. Wholesalers argue they don’t need a license, because they’re buying directly from homeowners, and laws generally permit “for-sale-by-owner” transactions.

In Philadelphia, Froehlich said he heard complaints of wholesalers using a bad news-good news approach on homeowners. The bad news is that a house needs tens of thousands in repairs. The good news is the wholesaler will take it off their hands for $30,000, though it’s really worth $100,000.

Philadelphia last fall created a license for wholesalers and requires them to tell owners how they can obtain fair-market value.

The Oklahoma Real Estate Commission heard about deals that collapsed, clouding the owner’s title, said Executive Director Grant Cody. In other cases, homeowners felt duped upon learning the wholesaler quickly sold the contract.

“It’s kind of like telling your girlfriend, ‘Hey, I want to marry you,’ and then she learns that you just got paid to hand her off to some other guy,” Cody said.

Oklahoma this spring required wholesalers to get a license and allowed the commission to set rules, Cody said. Arkansas and Illinois passed laws in 2017 and 2019, respectively, increasing their power to regulate wholesaling. A bill in Kansas died, but may be reintroduced.

Wholesalers acknowledge they have some bad actors, but say most are genuinely interested in revitalizing housing.

In Atlanta, Duane Alexander, a 37-year-old who jumped into wholesaling during last year’s Covid-19 quarantines, wakes each morning to cold call homeowners. By 10 a.m., he switches to his day job as a software engineer.

So far, Alexander has done four deals, in one case offering $120,000 for a home owned by a friend’s relative and assigning the contract to another investor for $130,000. Alexander made $10,000 for around 10 hours of work.

He said he sees his role as ensuring homeowners get a fair deal and that something nicer rises in a dilapidated home’s place.

“If I know that gentrification is going to happen regardless, as a person who comes from these kinds of neighborhoods, I would rather it be someone like me making money than some hedge fund,” said Alexander.

Updated: 6-19-2021

Home Flippers Pulled Out of U.S. Housing Market As Prices Surged

Home-flippers watched regular buyers parade through open houses and headed for the sidelines, as scarce inventory and rising prices pushed investors out of the housing market.

Flips accounted for 2.7% of U.S. home sales in the first quarter. That was the lowest rate since at least 2000, according to data from Attom. It typically takes about six months to buy, fix and sell a home, so the low rate indicates that flippers accounted for fewer purchases than usual in the second half of 2020.

The low flip rates could mean investors were worried that home price appreciation was due to fall off, said Todd Teta, chief product officer at Attom. If that was the case, flippers bet wrong: Home prices surged 16.2% in the first quarter, the largest year-over-year increase on record.

Another possibility is that flippers couldn’t find inventory to bid on, or that rising costs of lumber and other materials changed the economics of renovating homes. Still, traffic to Attom’s websites indicates Americans haven’t given up on the idea of investing in fixer-uppers.

“There’s still a lot of interest in the thought of being a flipper,” Teta said.

Updated: 10-13-2021

NYC Real Estate Agents Take On Zillow With Their Own Website

New York’s residential brokers are about to get their own listings website to compete with real estate giant Zillow Group Inc.

The city’s major brokerages — and the trade group that represents them — are working with Homesnap, owned by CoStar Group Inc., to develop the new platform. Citysnap, set to debut next year, will offer home shoppers an alternative to Zillow’s StreetEasy and other sites that the agents say use their hard-won listings as a springboard to generate revenue.

The effort comes after several years of acrimony between New York’s residential-property industry and the websites it’s come to rely on to reach the wider public. Agents have protested StreetEasy’s practice of charging a daily fee for rental listings.

And Zillow has faced legal challenges over its “Premier Agent” program, which sales brokers say allows any agent, anywhere, to muscle in on a deal by paying Zillow a fee.

“That’s definitely something that’s been a sore spot for the brokerage community,” said Gary Malin, chief operating officer of Corcoran Group, who advised on the initiative.

Citysnap will take the listings site managed by the Real Estate Board of New York — for now, open only to professional agents — and make it accessible to the public, with features they’ve come to expect, such as a property’s sales history and notification of price changes. REBNY’s service has more than 40,000 active listings from nearly 600 brokerage firms and property owners.

The new site will compete for eyeballs with Zillow’s StreetEasy — a staple in New York for brokers, consumers and urban real estate voyeurs alike, and known for its exhaustive database. Users can see, for instance, all the apartments for sale in a given building, the discounts their owners had to offer, or if the neighbors have a tax lien filed against their unit.

Being indispensable to brokers has been a financial boon for Zillow. In the second quarter, companywide revenue from the Premier Agent business surged 82% from a year earlier. Under the program, agents pay Zillow a fee to connect with would-be buyers who express interest in a given listing.

“We do this because we know how important it is for all consumers to have someone in their corner directly representing their interests when shopping for a home,” Viet Shelton, a spokesperson for Zillow, said in a statement.

Citysnap will guarantee that buyers interested in a particular home will be reaching out to the broker who listed it, not a random agent, according to Andy Florance, founder and chief executive officer of CoStar.

“It’s a better customer experience,” he said. “With this person I’m calling, am I initiating a nightmare of telemarketing, or am I reaching the agent who knows about this listing?”

Updated: 10-18-2021

Zillow Gets Outplayed At Its Own Game

Investors shouldn’t necessarily flip for Zillow’s flop, but they may want to start asking some broader questions.

Zillow, it seems, has over-flipped.

The company that has prided itself on its technology to outsource a lot of human work is suddenly referring the work right back to humans. Zillow Group’s automated home-flipping business has stopped pursuing new home acquisitions temporarily, Bloomberg reported on Sunday.

In a statement for this article, a Zillow spokesperson said in an email it is “beyond operational capacity in [its] Zillow Offers business.” Zillow said it is now connecting homeowners looking to sell their home to its local Premier Agent partners.

The pause seems to be a case of poor planning—a surprising lapse for a company that has been in the online real-estate business for nearly 17 years. Rather than a cash issue, Zillow is saying it experienced supply constraints having to do with on-the-ground workers and vendors. Leave it to a technology company to develop an algorithm to predict home values, but mismanage the human aspect of its business.

To add insult to injury, Zillow’s biggest competitor seems to be handling high volumes just fine. Opendoor Technologies said it is “open for business and continues to scale and grow,” noting it has worked hard over the past seven years to ensure it can continue to deliver as it expands. While Zillow long predates Opendoor as a company, it mainly offered an online marketing platform for agents before adding iBuying in 2018.

Zillow said it purchased a record number of homes in the second quarter at 3,805, but that still paled in comparison to the 8,494 homes Opendoor purchased in the same period. It doesn’t seem as though the near-term business has completely flopped: The company says it is continuing to process the purchases of homes from sellers who are already under contract as quickly as possible.

That means home purchases could still continue to grow sequentially in the fourth quarter, even with the pause. Zillow hasn’t publicly commented on its fourth-quarter buying forecast, but has said its third-quarter outlook implies a “step up” in purchase activity.

Rather than flip out, iBuying investors may want to look at Zillow’s news as an opportunity for its competitors. Opendoor is now active in 44 markets, including all but two of Zillow’s 25 markets.

Zillow’s pause therefore spells a golden opportunity for Opendoor. Zillow hasn’t yet said when it will resume new home purchases, but an email from a Zillow Offers Advisor to an agent seen by the Journal suggests the pause will last through the end of 2021 at the least.

Zillow’s mismanagement also highlights a key strength for smaller competitor Offerpad Solutions. OPAD 5.66% Led by a former real-estate agent, that company has long touted its ground game.

Offerpad, which is now a publicly traded company after closing its merger with a special-purpose acquisition company in September, seems to have been ahead of the curve in terms of understanding how many workers to employ and where, which repairs need to get done and how to execute them efficiently.

An analysis by BTIG Research shows Offerpad’s contribution profit per home sold was over 4.7 times that of Zillow’s last year.

But the news is also a signal that investors may want to start to tread more lightly around what has thus far been a banner year for the sector.

The reality is that iBuyers have incredible amounts of market data, can plan acquisitions and inventory months in advance and have a number of levers to pull to slow or accelerate the business, according to Mike DelPrete, a real estate tech strategist and scholar-in-residence at the University of Colorado Boulder. Given that, it is unusual that Zillow’s pause happened so suddenly and across all its markets.

The U.S. real-estate market has finally started to cool a bit. On Friday, Redfin reported the median home sale price rose 14% year-over-year in September—the lowest growth rate since December 2020. Meanwhile, closed home sales and new listings of homes for sale both fell from a year earlier, by 5% and 9% respectively.

Thus far, no other major iBuyer has said it was pausing new acquisitions this year. As Mr. DelPrete notes, it is possible Opendoor and Offerpad began to slow their own buying commitments as the market started to change, while Zillow missed the signs. More likely, Zillow, which has consistently prophesied what it calls the “Great Reshuffling” amid a permanence in remote work, just neglected to do its own reshuffling on the ground.

Updated: 11-1-2021

Zillow Seeks To Sell 7,000 Homes For $2.8 Billion After Flipping Halt

Zillow Group Inc. is looking to sell about 7,000 homes as it seeks to recover from a fumble in its high-tech home-flipping business.

The company is seeking roughly $2.8 billion for the houses, which are being pitched to institutional investors, according to people familiar with the matter. Zillow will likely sell the properties to a multitude of buyers rather than packaging them in a single transaction, said the people, who asked not to be named because the matter is private.

A representative for Zillow didn’t immediately comment.

The move to offload homes comes as Zillow seeks to recover from an operational stumble that saw it buy too many houses, with many now being listed for less than it paid. The company typically offers smaller numbers of homes to single-family landlords, but the current sales effort is much larger than normal.

If successful, the sale would make a dramatic dent in Zillow’s inventory. The company acquired roughly 8,000 homes in the third quarter, according to an estimate by real estate tech strategist Mike DelPrete.

Zillow shares dropped 8.6% to $96.61 on Monday. The stock had slipped 22% this year through Friday after nearly tripling in 2020. The company is scheduled to report earnings on Tuesday.

Zillow recently said it would stop making new offers in its home-flipping operation for the remainder of the year, though it continues to close on properties that were already under contract. The decision came after the company tweaked the algorithms that power the business to make higher offers, leaving it with a bevy of winning bids just as home-price appreciation cooled off a bit.

An analysis of 650 homes owned by Zillow showed that two-thirds were priced for less than the company bought them for, according to an Oct. 31 note from KeyBanc Capital Markets.

“I think they leaned into home-price appreciation at exactly the wrong moment,” said Ed Yruma, an analyst at KeyBanc.

Zillow put a record number of homes on the market in September, listing properties at the lowest markups since November 2018, according to research from YipitData. It also cut prices on nearly half of its U.S. listings in the third quarter, according to Yipit, signaling that its inventory was commanding prices lower than it expected.

Led by Chief Executive Officer Rich Barton, Zillow is best known for publishing real estate listings online and calculating estimated home values – called Zestimates – that let users keep track of how much their property is worth. The popularity of the company’s apps and websites fuels profits in Zillow’s online marketing business.

But more recently it has been buying and selling thousands of U.S. homes, practicing a new spin on home-flipping called iBuying that seeks to offer sellers a better way of selling a home.

Zillow invites owners to request an offer on their house and uses algorithms to generate a price. If an owner accepts, Zillow buys the property, makes light repairs and puts it back on the market.

The company bought more than 3,800 houses in the second quarter, making progress toward its stated goal of acquiring 5,000 homes a month by 2024. The increase in purchases left the company struggling to find workers to renovate the properties.

Zillow and its chief iBuying competitors, Opendoor Technologies Inc. and Offerpad Solutions Inc., often sell homes to single-family landlords in the normal course of business. Investors bought roughly 9% of all homes Zillow sold in the first quarter of 2021, Bloomberg previously reported.

Investors have been buying single-family rental homes during the pandemic, chasing the inventory-starved housing market for properties they can buy and rent. That should help Zillow find buyers, said Rick Palacios, director of research at John Burns Real Estate Consulting.

“I bet Zillow can sell to single-family landlords at a profit given how hungry those groups are for inventory,” he said.

Mobile-Home Communities In U.S. Draw Record Investment

Investors are pouring record levels of money into manufactured housing, seeking stability and yield as the need for affordable living options increases across the U.S.

Jones Lang LaSalle Inc. projects investment volume of $4.5 billion in mobile-home communities in the third quarter — an all-time high on a trailing four-quarter basis.

Valuations for the communities reached a record in the second quarter of $46,970 per pad, the real estate services firm said in a report. Occupancies also climbed to a new high, at 95.4%. And rents rose throughout the pandemic, to a record $800 a month on average.

Manufactured housing is becoming an increasingly popular option as costs for more-traditional properties soar. Strong demand is expected to continue over the long term as the share of Americans over age 65 grows, JLL said. Mobile homes also are gaining favor as communities add more amenities, such as pools and gyms.

While private capital represented 72% of mobile-home investment this year, institutional investors are getting more involved. They accounted for 22% of total volume, the highest percentage on record, according to JLL.

Updated: 11-5-2021

Zillow’s House-Flipping Rivals Defend Tech-Powered Homebuying

Zillow Group Inc.’s pullback from its home-flipping operation is reverberating across the real estate industry, leaving its competitors to defend using technology-powered algorithms to buy houses.

The issue is not with the business model, they say, but the execution.

“Buying homes is the easiest part of being an iBuyer,” Offerpad Solutions Inc. Chief Executive Officer Brian Bair said in an interview. “Buying, renovating and selling in 100 days is the key to doing this successfully.”

Zillow holds a lot of sway in the U.S. real estate industry, serving as a fixation for consumers and competitors. So when the company announced plans to abandon its home-flipping business and fire 25% of its workforce, it brought new scrutiny to the so-called iBuying industry.

IBuyers such as Offerpad and Opendoor Technologies Inc. use tech to buy and sell homes, pitching consumers on speed and convenience to ease headaches in the U.S. housing market. Shares of both companies slid this week as Zillow’s troubles rattled investors, though they rallied Thursday to erase much of those losses.

“When Zillow jumped in the market, I got pounded with questions,” Bair said. “What are you going to do now that Zillow is an iBuyer? Now I’m getting pounded with, Zillow is getting out, what are you going to do?”

For Opendoor, Zillow’s departure represents an opportunity, CEO Eric Wu said in an interview. He expects his company, which pioneered the iBuying model, to be the market leader now that the best-known brand is out.

“We’re going to lead the charge in this transition from offline to online,” he said in an interview.

Wu said Opendoor has invested heavily to build expertise in home pricing and getting renovations done in a timely, cost-efficient manner. Those challenges contributed to Zillow’s iBuying demise.

On Oct. 17, Bloomberg reported that the Seattle-based company would stop pursuing new acquisitions for its iBuying business, citing shortages of workers and supplies it needed to fix up homes. But Zillow also struggled to get pricing right. The company bought many homes for more than it could sell them for, forcing it to take writedowns of more than $500 million on property inventory.

Those results convinced Zillow CEO Rich Barton that the iBuying model was too risky for his company.

“Fundamentally, we have been unable to predict future pricing of homes to a level of accuracy that makes this a safe business to be in,” Barton said on the company’s earnings call this week.

Redfin Corp. CEO Glenn Kelman is also more circumspect on the prospects of the business. Unlike other iBuyers, Kelman’s company operates primarily as a real estate brokerage, using algorithmic home purchases as a complimentary offering.

That’s an important distinction, he said on a conference call with investors Thursday. It lets the company buy homes in markets where it thinks prices are favorable, while avoiding risk by funneling some customers to a more traditional process.

“This is a business that could scale to any size you want if you’re willing to overpay for houses,” said Kelman. “If you have to buy houses every day of the week in every type of market condition, you are just force-feeding yourself potentially toxic assets.”

The basic premise of the iBuying business remains unchanged, Opendoor’s Wu said. Industries from retail, food delivery and even auto purchases have moved online. The same shift is coming for real estate, and in Wu’s view, Zillow’s decision to stop flipping houses won’t stop that.

“In 10 years, I’m not sure it matters,” Wu said. “If we’re able to deliver on what we’re aiming to deliver, which is the ability to buy and sell a home together, at the same time, in a digital way, consumers won’t remember.”

Updated: 11-7-2021

‘You Are Just Force-Feeding Yourself Potentially Toxic Assets’: Redfin’s CEO Remains Cautious About iBuying’s Future

The number of homes Redfin sold through its home-flipping division rose more than 900% from a year ago, but the company continues to approach the business pragmatically.

Don’t expect Redfin to become a full-fledged iBuyer — even with Zillow exiting the market.

That was the message from the company’s CEO, Glenn Kelman, during Redfin’s third-quarter earnings call with analysts and investors. While the company’s division that focuses on buying, renovating and then selling homes has continued to see its revenue grow, Redfin’s leadership remains cautious when it comes to the home-flipping business.

‘We’re committed to the business — but as part of a complete real estate solution not as a standalone business. If you have to buy houses every day of the week, in every type of market condition, you are just force-feeding yourself potentially toxic assets.’

— Redfin CEO Glenn Kelman during the company’s third-quarter earnings call.

Kelman then argued that Redfin has a “fiduciary” responsibility to its customers. So if it doesn’t make sense for Redfin to buy a home, the company can aim to shift them over to the brokerage side of the business to help them offload the property in a more traditional way.

“That’s what we’re committed to — not the idea that we have to scale iBuying to make all of Redfin successful,” he said.

During the third quarter, Redfin sold 388 homes through its iBuying division, RedfinNow. That’s up from 37 homes a year ago — though the year-over-year comparison is skewed because last year’s low number reflected Redfin’s decision to halt its iBuying activities at the start of the pandemic. Still the most recent quarter’s sales volume is the highest over the past two years, as was the revenue RedfinNow earned per home.

And Redfin has continued to expand the number of markets where it makes direct offers to purchase homes itself. During the third quarter, the company brought RedfinNow to Chicago, Atlanta, Nashville, Charlotte and Raleigh.

Overall, Redfin recorded a net loss of nearly $19 million in the most recent quarter. The loss reflected higher marketing costs from prolonged advertising efforts and ongoing expenses related to the company’s acquisition of RentPath, which owns rental listing websites Rent.com and Apartment Guide.

Perhaps unlike Redfin’s competitors, Kelman doesn’t see companies that engage in this form of home flipping ultimately buying up a lion’s share of the real-estate market in the future. He suggested that iBuying would not come to represent 20% of the market, but instead somewhere between 1% and 10%.

“iBuying isn’t going away,” he added. “We think that many people before listing their house are going to wonder what they could get in a cash offer. I think the challenge with iBuying is just not to overreact. It isn’t the end all and be all the future of real estate.”

And unlike his colleagues at Offerpad, Kelman expects that the shifting conditions in the real-estate market will create more challenges for iBuyers rather than fewer, largely due to rising interest rates. Lower rates allows iBuyers to “borrow capital at a low cost,” Kelman argued, so if a company has trouble offloading a property backed by debt then it won’t put a damper on its balance sheet.

However, rising interest rates will not only make debt-leveraged purchases more risky, but also reduce home buyer demand. While he believes the housing market is simply balancing, he views that as more favorable to Redfin’s brokerage business than its home-flipping division.

Updated: 11-9-2021

Building And Renting Single-Family Homes Is Top-Performing Investment

Average risk-adjusted annual return for built-to-rent investments is now about 8%.

Single-family homes built to rent are emerging as the hottest corner of the U.S. property market, as investors respond to booming demand from home-seekers priced out of housing for sale.

Rents on homes are rising faster than ever. New household formation is also increasing the demand for rentals, as more young people get their own places.

Meanwhile, historically high housing prices and steep down payment requirements for homes are driving more people to keep renting, even as rents rise, said Green Street analyst John Pawlowski.

“The cost of housing alternatives for single-family renters has exploded,” he said.

The expected risk-adjusted annual return for built-to-rent investments in the private market is now about 8% on average, according to securities advisory Green Street, the highest of 18 property sectors tracked by the firm. The weighted average return for all property sectors was 6.1%, Green Street said.

The growing investor interest in building homes for rent is driving a land grab, especially in the Sunbelt where proponents expect the housing demand sparked in part by the pandemic to continue for years.

Close to 100,000 built-to-rent homes will have started construction this year, according to estimates from Brad Hunter, founder of the Hunter Housing Economics consulting firm. Investors have poured about $30 billion in debt and equity into the sector in 2021, with many billions more in future commitments, Mr. Hunter said.

Traditional home builders like Lennar Corp. and D.R. Horton Inc. have made building rental houses a major component of their business. Giant investment firms like KKR & Co. and Blackstone Group are also piling up cash to add already-built rental houses to their portfolios.

Crow Holdings, a company with a background in apartment construction, is considering testing the sector, starting with two proposed Texas projects near Dallas and Austin.

Home builder Bruce McNeilage’s company Kinloch Partners has built and currently owns more than 100 homes near Nashville, Tenn. But he said he could no longer compete for land in that fast-growing region because he was losing out to more deep-pocketed investors

That has made him look for less crowded opportunities. His firm is among those racing to buy land in Texas towns like Royse City, Waxahachie, and Melissa, which are more than 30 miles from downtown Dallas. He plans to build 500 hundred homes, all for rent, across the Texas exurbs during the next 18 months. But now bigger investors are circling some of the same plots.

“You almost have to find the land before it gets put on the market,” Mr. McNeilage said. “Because the day it gets put on the market, there’s a feeding frenzy.”

Some analysts and builders are starting to believe the breakneck pace of growth in the sector is unsustainable. Investors are stepping over each other in the Sunbelt markets like Phoenix, analysts and builders say, risking a supply glut. Land sellers are raising their asking prices.

“What we’re seeing across the board is that land values are rising,” said Pratik Sharma, managing director of Bridge Tower Group, a single-family rental builder and manager.

Higher land prices could mean that investor returns compress, making built-to-rent less attractive for some investors. The relatively low inventory of available land that is desirable to builders could also mean fewer deals get signed than expected.

But the biggest players in this market are showing no signs of slowing. American Homes 4 Rent, which owns more than 55,000 houses, built 1,600 new ones last year and expects to deliver more than 2,000 in 2021. Tricon Residential, a Sunbelt-focused single-family rental owner, made its debut on the New York Stock Exchange last month and has plans to buy up to 5,000 new construction rental homes directly from home builders.

‘It’s Really A Toy’: How Reliable Is Zestimate, Zillow’s Extremely Popular Home-Valuation Tool?

Zillow used Zestimate to help guide the prices it paid for homes through its now-shuttered home-flipping business.

Zillow’s experiment in home-flipping has blown up in its face — and the company is blaming the “unpredictability” of home prices.

Now, some are asking about the reliability of the company’s so-called Zestimates, which provide an estimate of a home’s value based on a proprietary formula. Zillow says a Zestimate is published for around 100 million homes nationwide.

In announcing its latest quarterly earnings on Tuesday, Zillow confirmed that it will “wind down” its Zillow Offers division that focused on buying homes, refurbishing them and then selling them, hopefully for the profit. But the profit piece was missing.

‘They had a vision where every Zestimate you would see on the website would be like a live bid.’

— D.A. Davidson analyst Tom White

During the most recent quarter, Zillow’s Homes segment, which includes Zillow Offers, recorded a nearly $422 million loss before taxes. That’s up from a roughly $76 million loss a year earlier. Reports have suggested that the company has already begun offloading some 7,000 homes, with a majority fetching a price below what Zillow paid for the properties.

“We’ve determined the unpredictability in forecasting home prices far exceeds what we anticipated and continuing to scale Zillow Offers would result in too much earnings and balance-sheet volatility,” Zillow Group co-founder and CEO Rich Barton said in the earnings release.

The company said closing its iBuying business segment will “take several quarters” and involve a 25% reduction in the company’s workforce.

In light of the challenges Zillow faced with its home-buying efforts, some people took to social media to call into question the accuracy of the Zestimate tool. “It’s really a toy,” said Mike DelPrete, a real estate analyst who tracks the iBuying sector. “It’s meant to drive people’s interest in property.”

The Zestimate, which first debuted in 2006, played a role in Zillow’s home-buying operations. “We leveraged the Zestimate in our Zillow Offers operations the same way we encourage the public to use it: as a starting point,” Zillow spokesperson Viet Shelton told MarketWatch in an email.

However, Zillow had more ambitious plans in mind for merging its Zestimate model with its iBuying division. In February, Zillow announced that the Zestimate would represent “an initial cash offer” for certain eligible homes across 20 cities, including Phoenix, Miami, Denver, Nashville, Houston and Los Angeles.

“Presenting the Zestimate as a cash offer to qualifying homes up front will save time, reduce friction and provide greater transparency — getting us closer to our vision of helping customers transact with the click of a button,” Zillow chief operating officer Jeremy Wacksman said in the announcement.

Consequently, to some, the recent turn of events suggest Zillow’s experiment failed.

“Zillow used to talk about how they had a vision where every Zestimate you would see on the website would be like a live bid, and you could just hit the bid and sell your home for that amount,” said D.A. Davidson analyst Tom White. “This move out of iBuying suggests that’s not going to happen.”

How Accurate Is The Zestimate?

Complaints about the Zestimate are nothing new. An unsuccessful 2017 class-action lawsuit against Zillow claimed that the company was misleading home buyers by publishing figures that were below what sellers were seeking for their homes. The judge ultimately dismissed the case, noting that the tool’s name “itself indicates that Zestimates are merely an estimate of the market value of a property.”

Zillow says that the Zestimate has a median error rate of 1.9% for homes that are on the market and 6.9% for homes that are off the market.

The accuracy varies significantly across markets. In Cincinnati, for instance, roughly 35% of Zestimates for off-market homes were within 5% of the eventual sales prices, and 82% were within 20% of the price. Comparatively, in Denver, 51% of Zestimates were within 5% of the sales price, and 94% were within 20% of the sales figure.

According to Zillow, the Zestimate has a median error rate of 1.9% for homes that are on the market and 6.9% for homes that are off the market.

In that sense, Zillow has likely succeeded with the Zestimate. Scrolling through the site’s listings has become something of a hobby for many, with Saturday Night Live even lampooning the habit. Finding out the value of homes in your area is likely part of the behavior’s allure.

There are certain circumstance where the valuation may be more trustworthy than others, though. For instance, with the “cookie-cutter type of homes,” Columbia University real-estate professor Tomasz Piskorski said, the model may be more effective since it can rely on “a lot of comparable transactions in the area.”

Zillow, itself, has recognized the need to improve the accuracy of its valuation model. In 2017, the company launched a contest in which participants sought to better the algorithm underpinning the Zestimate, with the winning prize going to a group of data scientists and engineers from three different countries.

At the time, Zillow said the Zestimate was on average around $10,000 off of the actual sales price of a median-priced home, and that the information provided by the winning team would reduce that margin by around $1,300.

Challenges in the COVID-era housing market

The red-hot housing market in America since the summer of 2020 likely confounded Zillow’s efforts to appropriately price the homes it was purchasing.

The company’s spokesperson argued that the Zestimate was not at the crux of the pricing issues it faced, instead pointing to difficulties the company had in accurately forecasting “the future price of inventory three to six months out, in a market where there were larger and more rapid changes in home values than ever before.”

As some analysts argued, any real-time valuation will be limited in what it can tell you about the direction of prices in the future. “Valuation is inherently ephemeral,” said Michael Greene, co-founder and CEO of ResiShares, a residential real-estate investment company.

Greene used an analogy of a fast-moving train to describe the difficulty inherent to nailing down the price of a home in a competitive market like the one that’s been in place for over a year now.

“If a train is moving faster, knowing where the train is at any given point in time tells you much less about where it will be when you have to catch it,” he said.

‘Valuation is inherently ephemeral.’

— Michael Greene, co-founder and CEO of ResiShares

Another factor were the structural changes that have occurred in the market — such as the sudden demand for larger homes in the suburbs — that made past data less reliable in predicting future prices, Piskorski said.

Zillow also had the disadvantage of being newer and perhaps having less reach in the markets it was operating in as a home flipper. Brokerages have better access to real-time transaction data, Jason S. Helfstein, head of internet research and managing director at Oppenheimer & Co., argued.

“Zillow wasn’t necessarily privy to that because they would see the value of a home that sold once it updated” in the multiple listing service operated by local Realtors associations, Helfstein said. There’s typically a lag in that MLS data becoming available.

Helfstein contrasted that with one of Zillow’s main iBuying competitors, Opendoor OPEN, +15.57%, which he said was “actually in a market doing transactions just like a brokerage firm.”

However, Helfstein contends that Zillow’s problems in iBuying had more to do with holding onto homes for too long and at a higher cost than expected, rather than because of deficiencies with the Zestimate.

Ultimately, Zillow’s troubles reflect how difficult it is to succeed at buying and selling homes as an investor. “IBuying is a difficult business model, and it was never expected to not be,” said Ygal Arounian, managing director of internet equity research, Wedbush Securities.

Zillow’s Home-Flipping Demise Puts Other iBuyers On The Spot

Some analysts say exit demonstrates the challenges of turning a profit in capital-intensive business, especially if the market continues to cool.

Investors are stepping up their scrutiny of Opendoor Technologies Inc. and Offerpad Solutions Inc., the two biggest players left in the iBuying industry after Zillow Group Inc. pulled the plug on this business.

IBuyers purchase homes from consumers who are looking to sell quickly and conveniently, using algorithms to help determine what price to pay. After renovations, they place the homes back on the market.

Zillow stunned the market last week when it said that it is no longer buying homes and will lay off a quarter of its roughly 8,000-person workforce. The company reported a $304 million write-down on the value of homes it owns and said it expects to take another write-down of up to $265 million in the fourth quarter.

Opendoor said its business model enables it to respond to changes in a housing market’s price appreciation, seasonal buying patterns and other factors that signal how much the firm should be buying and what it should be paying.

But some analysts say Zillow’s exit demonstrates the challenges of turning a profit in such a capital-intensive business, especially if the currently hot market continues to cool.

“The fact that the losses [for Zillow] could be so dramatic on a relatively small number of homes, I think, just highlights the potential risk of just slight misses in forecasting,” said Tom White, senior research analyst at D.A. Davidson Cos.

Zillow’s stock price plunged last week, with its Class A shares ending the week down 37%. Shares of Opendoor, Offerpad and real-estate brokerage Redfin Corp. , which operates a smaller iBuying business, all fell after the Zillow news. But they recouped some of the losses by the end of the week.

Investors will get a more detailed picture of the financial health of Opendoor and Offerpad, which both went public in the past year, when they report earnings Wednesday.

The iBuying industry has expanded rapidly since Opendoor’s launch in 2014. IBuyers can make money by charging fees to home sellers, offering additional products like mortgages and selling homes for more than they paid to purchase and renovate them.

Homeowners sold about 15,000 homes to iBuyers in the second quarter, Zillow said in a September report. That accounted for only about 1% of all home sales in the U.S. during that period, but in some metro areas their participation is greater. In Phoenix, Charlotte, N.C., and Atlanta, iBuyers had a market share of between 5% and 6% in the quarter.

As home prices started soaring last year, iBuyers were easily able to sell homes for more than they’d paid. But home-price growth has started to slow, as sky-high prices deter some buyers and mortgage rates tick higher. That has made it harder for home-flippers to profit from price appreciation.

“What this is going to do is create a wake-up call for the other iBuying platforms to say, ‘If we’re going to remain in the flip business, what do the margins look like?’ ” said Nick Bailey, president of Re/Max Holdings Inc., a real-estate brokerage franchiser, and a former vice president at Zillow.

As price growth slowed, Opendoor and Offerpad tapped the brakes in one major market where Zillow zoomed ahead. In Phoenix, Opendoor and Offerpad bought fewer houses in September compared with August and paid less for them, while Zillow bought more houses at higher prices, according to an analysis of sales records by real-estate tech researcher Mike DelPrete, scholar-in-residence at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

Zillow’s gross margins in its iBuying business have trailed Opendoor’s and Offerpad’s for years, Mr. DelPrete said. “This sounds like a Zillow issue and not an iBuying issue,” he added.

Redfin started offering lower prices for homes in March and kept reducing prices into September, Chief Executive Glenn Kelman said. He expects iBuying to remain a small segment of the market, as most sellers won’t want to accept a lower price for their homes in exchange for convenience.

Mr. Kelman also said it would be more difficult for iBuyers if their borrowing costs go up, or if housing demand falls and they can’t count on reselling homes as quickly. On the other hand, iBuying bulls argue that lower demand could make sellers more eager for the convenience of a quick purchase.

For now, Zillow’s exit from the market means the other iBuyers have less competition. “It’s more of an opportunity for us than ever before,” said Brian Bair, Offerpad’s chief executive.

Updated: 11-10-2021

Zillow Sells 2,000 Homes In Dismantling Its House-Flipping Business

Pretium Partners is buying the houses in 20 markets with plans to rent them to families.

Zillow Group Inc. reached a deal to sell about 2,000 homes from its ill-fated house-flipping program, the company’s biggest bulk sale as it starts unloading thousands of homes and terminates the business.

Pretium Partners, a New York-based investment firm, has agreed to buy Zillow homes across 20 U.S. markets and plans to rent them out, according to people familiar with the matter.

The digital real-estate company said it intends to sell roughly 9,800 homes it owns, plus an additional 8,200 it had been in the process of buying. The company expects to lose between 5% and 7% on these sales. In the transaction with Pretium, Zillow received market price for the properties, these people said.

Zillow’s home-flipping practice involved buying homes, lightly renovating them and then selling them quickly, making money on transaction fees and home-price appreciation. The company and other iBuyers used an algorithm to make home-price estimates and determine what to pay home sellers.

Zillow said last week that it was shutting down the business because it couldn’t accurately predict future home prices and was losing too much money. The company expects to record losses of more than $500 million from home-flipping by the end of this year and is laying off a quarter of its staff.

The sale to Pretium kick-started Zillow’s unwinding of the iBuying business.

Pretium, which owns around 70,000 single-family homes, plans to hold on to the homes and operate them as rentals. The business has been a success for the firm and others that focus on leasing homes near hot metro areas where families often feel priced out of the for-sale market. A burst in new household formation, which had been delayed earlier in the pandemic, also boosted demand for rental housing.

“We continue to invest in communities and improve access to housing throughout the U.S.,” a spokesman for Pretium said.

As of July, single-family rents were up 8.5% compared with the year prior, according to housing data provider CoreLogic, the highest such increase in at least 16 years.

Other large rental-home investors, like Invitation Homes Inc. and American Homes 4 Rent are also considering bids on some of Zillow’s remaining housing stock, say people briefed on the matter.

In addition to the homes Zillow had left at the end of the third quarter, the company said it has an additional 8,200 in contract to buy and will also need to sell. Zillow has said the full winding down of its home-flipping business is likely to take multiple quarters.

Three Democratic Senators, including Banking Committee Chairman Sherrod Brown of Ohio, have raised concerns about real-estate investors limiting the number of homes available to ordinary home buyers.

In a letter on Monday to Zillow Chief Executive Rich Barton, the senators asked about the company’s plans to sell homes to investors, including to Pretium, which the Senators said had “a troubling track record,” citing reports of poor home conditions and tenant complaints about billing practices.

A Pretium spokesman said: “For households across the country that choose to rent, Pretium provides a high-quality housing experience through consistent, dependable and attentive service at our well-maintained and affordable homes.”

Pure-Play iBuyers Go Big As Zillow Goes Home

While Opendoor and Offerpad proved they can hang tough, investors shouldn’t be so quick to double down.

In the iBuying Hunger Games, Opendoor Technologies is winning just by virtue of survival. But when the risks are this high, investors should want the rewards to look a lot more appealing.

Following the home-flipping flop of Zillow Group, one can choose to look at the iBuying industry as a runaway victory for Opendoor, which now owns a disproportionately large chunk of the Monopoly board, or a spectacular failure waiting to happen.

Investors seem more disposed to the former view, sending shares of Opendoor up 15% after hours following its third-quarter financial results.

The pure-play iBuyer said it nearly doubled its revenue on a sequential basis in the period and, unlike Zillow, it even turned a profit—on the basis of adjusted earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization, that is.

If Zillow went big last quarter, Opendoor characteristically went much bigger, buying 15,181 homes—79% more than it purchased in the second quarter and 57% more than Zillow.

Furthermore, while Zillow forecast that further write-downs would lead to steeper losses for its iBuying business in the fourth quarter, Opendoor forecast that its own adjusted Ebitda losses would be minimal, if it lost any money on that basis at all.

The safe conclusion here is that Opendoor is simply better at iBuying than the seasoned real-estate giant was. And it isn’t alone. A smaller iBuyer, Offerpad, said Wednesday that it too managed to make money on an adjusted Ebitda basis last quarter, albeit off a much smaller base.

That conclusion alone doesn’t necessarily make iBuying a compelling investment with a reward that exceeds the significant risk. Opendoor now says it had 17,164 homes on its balance sheet as of Sept. 30, representing nearly $6.3 billion in value. That would be an eye-popping risk in a still booming market, let alone one that has already started to turn.

IBuyers seem to be approaching the market opportunity from different angles. Offerpad, for example, seems focused on growing more slowly, doing fewer flips better.

Compared with Opendoor, it tends to do more-intensive remodeling, but, with far fewer properties, it often seems able to relist its inventory in even fewer days. Opendoor, meanwhile, is focused on rapid expansion in an attempt to diversify its markets in hopes of strategic advantage. It is now in 44 markets compared with Offerpad’s 21.

IBuyers will tell you that the best margin opportunity isn’t in the home-flipping transaction itself, but in add-on services such as mortgage origination and title and escrow, which will grow over time. Opendoor, for example, believes it can manage contribution margins of 4% to 6% on a sustained annual basis, but that longer-term those margins can grow to 7% to 9% as the penetration of higher-margin services increases.

On a per-city basis, iBuyers will inevitably get better the longer they operate in various locations, honing their algorithms and on-the-ground contacts based on each market’s idiosyncrasies. But with new markets come new risks, layered on top of the overall risk of the housing market writ large.

As Zillow’s chief executive, Rich Barton, put it last week, “We have been willing to take a really big swing on this, but not a bet-the-company swing.”

Pure-play iBuyers have no choice. In its earnings release Wednesday, Offerpad’s chief executive, Brian Bair, said he was proud that his company has achieved a less than 1% variance between its aggregate estimated and actual sales prices since its 2015 launch through the first half of this year. Glaringly absent from that statistic is how Offerpad fared in terms of variance in the third quarter.

To an analyst’s question on Wednesday’s earnings call of how Opendoor will deal with home price fluctuations in the future, apropos of Zillow’s failure to do so successfully, Chief Financial Officer Carrie Wheeler said Opendoor’s model works in up, flat and down markets, concluding, “We’re very good at this.”

Consider, though, that even with Opendoor’s skill in the midst of a record-setting real-estate market, the company managed just $35 million in adjusted Ebitda, despite generating nearly $2.3 billion in revenue for the third quarter.

Opendoor’s public-offering filing shows that at least dating back to 2017, the company has yet to post a full year of profits on that basis. Wall Street is forecasting that even in 2025, its adjusted Ebitda margin will reach just 1%.

The big-picture opportunity for iBuyers is capturing what Opendoor calls a generational shift from offline to online in real estate, with 99% of U.S. home transactions still occurring offline. It is the very opportunity that made Mr. Barton’s eyes grow bigger than his stomach.

Just because Opendoor has the appetite doesn’t mean that iBuying will ever taste all that sweet.

Updated: 4-7-2022

For Home Flippers In California, A Proposed Tax Could Make A Quick Sale Costly

If adopted, a new legislation would add 25% tax on the capital gains homeowners make if they sell a property within three years.

Q. What are the details of the new California legislation that would tax house flippers?

A. House flippers in California may soon be hit with an extra tax if they sell their renovated house within a few years, according to proposed legislation.

State Assemblymember Chris Ward, a Democrat representing-San Diego, introduced the California Housing Speculation Act, or AB 1771, in February. The legislation, if adopted, would tack on a 25% tax on the capital gains homeowners make if they sell a property within three years of its purchase.

If a home is sold after that three-year mark, the rate drops by 20% each subsequent year. By year seven of the original purchase, the surcharge goes away.

California has long been facing a housing crisis. But investors already pay heftier-than-usual short-term capital gains taxes if they sell a home within a year, said Sacramento-based tax attorney Betty Williams. The short-term capital gains tax goes up to 37% for 2021.

“My initial reaction is that it may not succeed in meeting the target,” Ms. Williams said. “The idea that it’s going to stop housing prices from going up—I think in a lot of times flippers might increase their sales price to cover that cost.”

Many flippers who refurbish and resell homes as a business are successful because they often buy undesirable homes with cash.

“Sometimes those houses—you couldn’t even get a loan on them because of the problems with them, so they can only be sold to a cash buyer,” Ms. Williams said. “That would then hurt the market of houses that can’t be sold through the traditional process of a loan.”

The tax has some exemptions. For instance, it would not apply to first-time home buyers, those who use a property as their primary residence, those who own affordable housing units, those who are active in the military, or to those selling properties after an owner’s death.

The surcharge would go to a fund with the Franchise Tax Board that would be distributed to counties to create affordable housing; school districts; and to support community infrastructure.

In a video announcing the tax in early March, Mr. Ward said the goal of the legislation was to prevent investors from driving up prices by buying properties in cash, renovating them and then selling them at much higher prices, which contributes to California’s housing crisis.

The median price of a single-family home in California was $797,470, in the fourth quarter of last year, and just 25% of Californians could afford that, according to the California Association of Realtors.

A hearing on the bill has been set with the Assembly Revenue and Taxation Committee for April 25. If adopted, the tax would go into effect on Jan. 1, 2023.

Updated: 11-29-2022

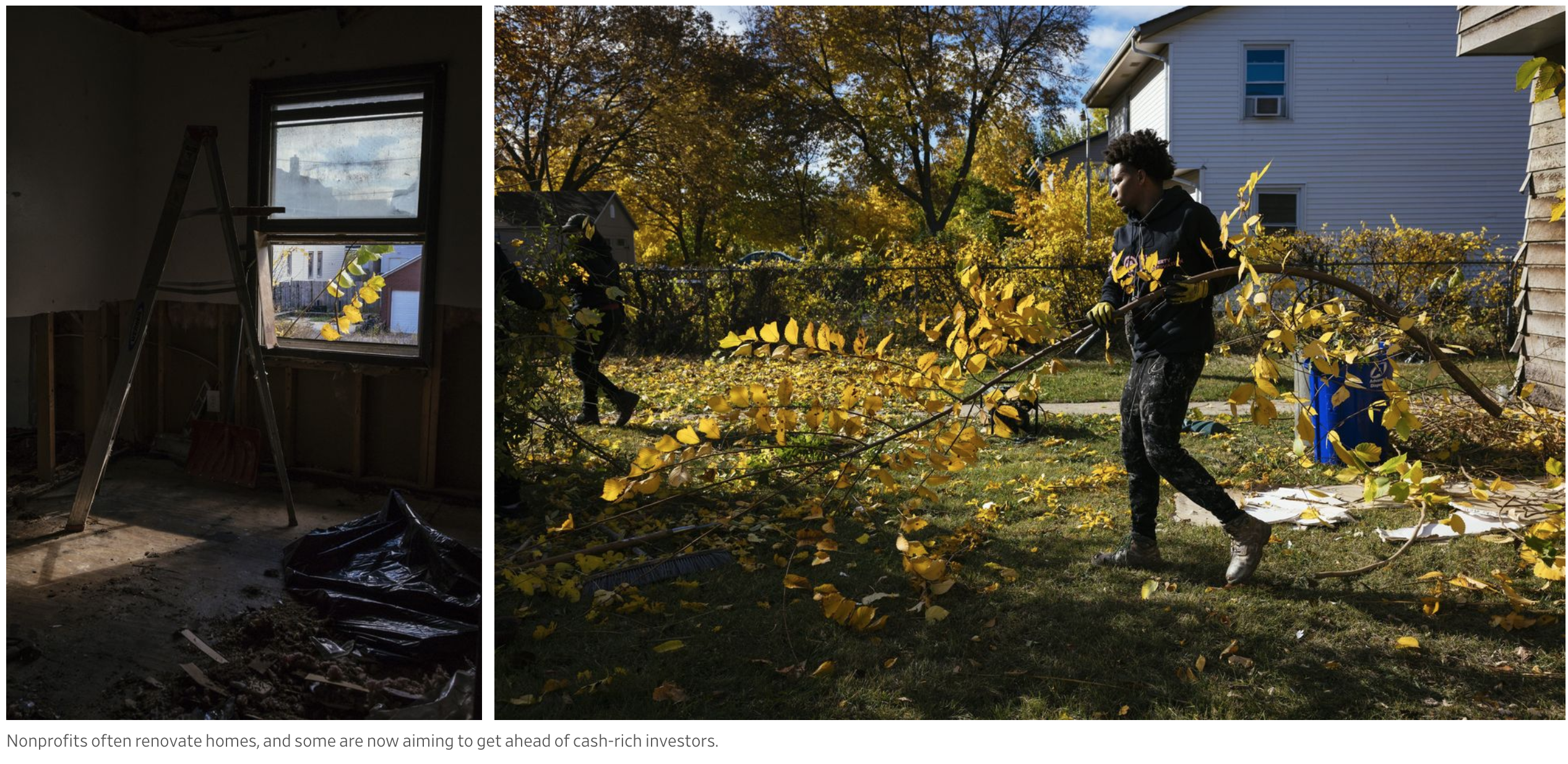

Activist House Flippers Take On Wall Street To Keep Homes From Investors

Housing groups try to counter rental conversions and help lower-income residents achieve homeownership.

Acts Housing, a Milwaukee nonprofit, has helped local low-income families buy their first home for more than two decades.

More recently, these families have been losing out to investors whose all-cash bids are more attractive to sellers.

“If a family is willing to pay the same amount for a property as an investor, how do we make sure that family actually gets that opportunity?” asked the group’s president and chief executive, Michael Gosman.

The answer, he decided, was to act more like an investor. Mr. Gosman said he is raising money for a fund that would purchase homes in cash, then flip them back to families for close to cost.

The Milwaukee fund is part of an emerging strategy among housing groups aiming to keep investors from buying lower-cost homes by beating them to the deal.

Call them activist house flippers.

Investment firms and other investors bought a record number of homes during the Covid-19 pandemic. In the first quarter of 2022, investors accounted for more than one in five home purchases nationally. Many of those investors converted homes into rentals.

Investors say that through rental conversions they are making more homes available to people who cannot afford to buy or who would prefer to rent.

Housing groups say the growth of this business has come at the expense of lower-income residents because rental conversions reduce opportunities for residents to build wealth through homeownership.

While there are many nonprofits nationwide that renovate homes or offer homeownership programs, the emphasis on getting ahead of investors is a budding trend.

In Jackson, Miss., one neighborhood leader is flipping houses to first-time buyers. A Memphis nonprofit aims to restore the status of a once-middle-class neighborhood by selling investor-targeted homes back to longtime residents.

Activist flippers say they are leveling the playing field. Many home sellers prefer cash buyers because they are viewed as the fastest and most reliable purchaser.

Nonprofits want to offer an alternative all-cash option. “We’re going to make you a competitive offer,” Mr. Gosman said.

The Milwaukee fund’s goal is to raise $10 million by next year, drawing contributions from government and private philanthropic sources. The group typically targets homes such as a small bungalow on Milwaukee’s north side that costs $75,000 and needs $25,000 in repairs.

Acts said about 80% of the families it works with are people of color, and the group has a registry of more than 100 qualified families that it hopes to begin serving with the new fund.

“I’d find something and the investors would come in and outbid me,” said Niya Preston, a Milwaukee resident who started working with Acts to buy a home in 2020.

The nonprofit helped her improve her credit, connected her with down-payment assistance and provided her with a real-estate agent.

Then Ms. Preston qualified for a mortgage, but still lost out to cash buyers on homes priced under $100,000. One of those homes is now a $1,420-a-month rental, about twice as much as Ms. Preston’s expected mortgage payment.

In Memphis, Tenn., Seth Harkins, who leads the nonprofit Alcy Ball Development Corp., said he sees similar trends.

The homeownership rate across Memphis has declined over the past two decades, he said, and recently homes in the Alcy Ball neighborhood have been selling to out-of-town rental landlords paying in cash.

“What that means to me is that no one in Memphis will ever be able to build equity in that house ever again,” Mr. Harkins said.

He is now raising money from charity and government sources so he can purchase homes to sell back to neighborhood residents who qualify.

California also set aside $500 million last year to subsidize nonprofits that purchase homes and rental properties, with the intent of helping these groups compete with Wall Street firms.

Related:

Housing groups buying homes face market challenges that their new interventions are unlikely to solve. Most families still need mortgages, and mortgage rates are twice as high as they were a year ago, putting homeownership further out of reach for many.

And while investors are buying fewer homes lately, they are still active and have lots of capital, meaning they might be able to pay higher prices than nonprofit buyers.

These limitations are why some housing analysts say publicly controlled buyers might prove more effective, in terms of accountability, impact and the size of resources at their disposal.

The biggest buyer with public backing is the Port of Greater Cincinnati Development Authority, which bought nearly 200 rental homes also targeted by large investment firms.

The authority hopes to sell as many of the homes as possible to the renters. Low-interest bonds are financing the endeavor.

The authority is also looking into issuing its own mortgages, so buyers can borrow at rates below prevailing norms.

Converting the tenants into homeowners has been slow going. When the authority acquired the homes, many of the tenants lived in deteriorating conditions and were behind on rental payments, said Laura Brunner, the authority’s chief executive.

Ms. Brunner said she hopes half the tenants will have started the authority’s homeownership counseling program by the end of next year, but only one tenant is ready to buy so far. Pitching the program’s benefits and getting the tenants financially prepared to buy is a long process.

“These are people who have been abused by the system for a long time—and just knocking on the door saying, ‘We’re here to help, do you want to buy a house?’ is met with a great deal of skepticism,” she said.

In Milwaukee, Ms. Preston, who was outbid at least twice by investors, eventually succeeded. She found a home for sale late last year that was owned by the local housing authority and sold through a program for low- to moderate-income buyers.

But many families working with Acts haven’t had the same good fortune and will look to buy homes through the nonprofit’s new acquisition fund.

To promote the fund, Mr. Gosman is working on outreach to potential home sellers. He said he is thinking of taking cues from the professional flippers, who often put up fliers or send mailers.

“I think in a lot of cases we’ll copy them,” he said.

Related Articles:

What’s Rent To Own & How Does It Work? A Guide To Renting Vs Buying

San Francisco’s Housing Market Braces For An IPO Millionaire Wave (#GotBitcoin?)

Affordable Housing Crisis Spreads Throughout World (#GotBitcoin?) (#GotBitcoin?)

Home Prices Continue To Lose Momentum (#GotBitcoin?)

Freddie Mac Joins Rental-Home Boom (#GotBitcoin?)

Retreat of Smaller Lenders Adds to Pressure on Housing (#GotBitcoin?)

OK, Computer: How Much Is My House Worth? (#GotBitcoin?)

Borrowers Are Tapping Their Homes for Cash, Even As Rates Rise (#GotBitcoin?)

‘I Can Be the Bank’: Individual Investors Buy Busted Mortgages (#GotBitcoin?)

Why The Home May Be The Assisted-Living Facility of The Future (#GotBitcoin?)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.