Ultimate Resource On Bees And Beekeepers

Nectar is scarce because ‘every hipster in the world wants to have a beehive’. Ultimate Resource On Bees And Beekeepers

In the tiny universe of New York City beekeeping, Tom Wilk is one of the queen bees. He founded the Queens Beekeepers Guild. His business, Wilk Apiary, manages 30 hives in eight New York locations.

His honey, sold in local stores and markets, commands $20 for an 8-ounce jar. He also helps organize NYC Honey Fest, an annual event in Rockaway Beach, Queens, where thousands gather to sample and buy honey on the boardwalk.

Mr. Wilk, however, isn’t planning to quit his day job as a salesman for a wine and spirits distributor.

Related:

Harvard Quietly Amasses California Vineyards—And The Water Underneath

“I haven’t broken even yet,” he said of his sideline enterprise.

The New York City bee business, it turns out, is no honeymoon.

Upstate, where flowers are plentiful, it’s possible to extract as much 200 pounds of honey a year from a single hive. Here, you’re lucky to get 50 pounds, Mr. Wilk said.

And production is only getting more challenging as urban beekeeping grows in popularity and more bees compete for a limited supply of nectar, he noted.

“Manhattan is maxed out unless you’re close to Central Park,” Mr. Wilk said. “Red Hook, maxed out. There’s very little foraging area, and every hipster in the world wants to have a beehive.”

Beekeepers are required to register their apiaries with the city’s health department; officials didn’t respond to inquiries about the number of beekeepers in the city.

Earlier this month, just after dawn, 182 beekeepers lined up in Manhattan’s Bryant Park for the square’s annual bee-distribution event, eager to pay $160 for a 3-pound box of bees—that’s roughly 12,000 insects—trucked in the night before from Georgia.

Many were strictly amateurs, including a New Jersey car dealer, a Brooklyn custodian and a television producer from Queens. But the crowd included a number of folks looking to make a little honey money.

Judi Counts, who manages an Episcopal retreat house on the Upper East Side, was buying a new colony for her rooftop hive. Last year’s colony died during the winter because of the temperature swings. “They were like, ‘Sorry. No. Done.’ ” she said.

Ms. Counts sells her honey at the annual House of the Redeemer garden party. She makes labels for the $20, 16-ounce jars that say “Sweet Redemption.” The $500 she earns just about covers the cost of keeping the bees, she said.

It’s possible, of course, to boost one’s margins with clever marketing. Queens beekeeper Ruth Harrigan, who worked on Wall Street for 20 years before establishing her first hive in 2010, commands $5 for 2-ounce portions of honey packaged in bear bottles bearing messages such as “Don’t Worry Bee Happy Honey.”

“There’s really no money to make in honey unless you are creative about it,” she said.

Her HoneyGramz line sells in 250 shops, including gourmet food stores and hospital gift shops.

It’s been so successful, Ms. Harrigan can’t meet the demand with her own production. She buys honey for the line from commercial suppliers and saves her local honey to sell in city markets.

Tourists snap up her Queens and Staten Island honey packaged in travel-size, 2.8-ounce jars for $10. “They are intrigued that there are bees in New York City,” she said.

Andrew Coté, the man who trucked bees up from Georgia to sell at the Bryant Park event, is likely the city’s biggest beekeeper.

President of the New York City Beekeepers Association, he produces several thousand pounds of honey a year from the 108 hives he maintains in 25 locations, including Bryant Park, cemeteries, community gardens, abandoned parking lots and a Buddhist monastery.

But even Mr. Coté refers to himself as a sideliner rather than a commercial beekeeper.

To supplement honey sales, he offers beekeeping classes, provides bees for film and commercial shoots and offers apiary maintenance to outfits like the Durst Organization, which keeps 10 hives on the roof of its 55-story Bank of America Tower in Midtown.

The real-estate developer includes honey collected by Mr. Coté in its holiday gift baskets for commercial tenants and in its conference rooms for meeting attendees.

“I’m like a pool boy for the bees,” Mr. Coté said.

Beekeeper, cardiologist and internist Patrick Fratellone gives pollen and raw local honey collected from his three hives to patients in his Manhattan practice. “It’s great for allergies,” he says.

His specialty is bee venom, which is said to be anti-inflammatory. He uses it to treat autoimmune disorders, including arthritis, stinging his patients with bees plucked from the portable hive he keeps in his office.

Dr. Fratellone also uses bee venom to treat his own tennis elbow condition, stinging himself eight times a day.

But like the city’s other beekeepers, he reports that his bee work is mainly a labor of love.

Insurance doesn’t cover bee venom, he says. Rather than charge for the sting, he asks patients to make a donation to the American Apitherapy Society, an association of health-care professionals who use bee products.

And while the venom treatments can attract new patients who have tried other things, it doesn’t ensure repeat business. “Once you sting the patient,” he said, “the patient can order their own bees and sting themselves.”

Updated: 5-22-2019

You’ll Need a Lot More Money to Buy That Jar of Honey

Beekeepers are in a sweet spot as consumer trends shift away from cane sugar and high-fructose corn syrup.

Honey prices are starting to sting.

Global honey prices are at their highest levels in years, due to a new wave of consumer demand for natural sweeteners and declining bee populations that are hampering mass production.

Honey has been used as a sweetener for centuries. But in recent years, it has become popular with people looking for healthier alternatives to cane sugar and high-fructose corn syrup. It is consumed in beverages, pastries, cereals and other foods.

In addition, it is being used more as an ingredient in shampoos, moisturizers and other personal-care products that companies market as naturally made.

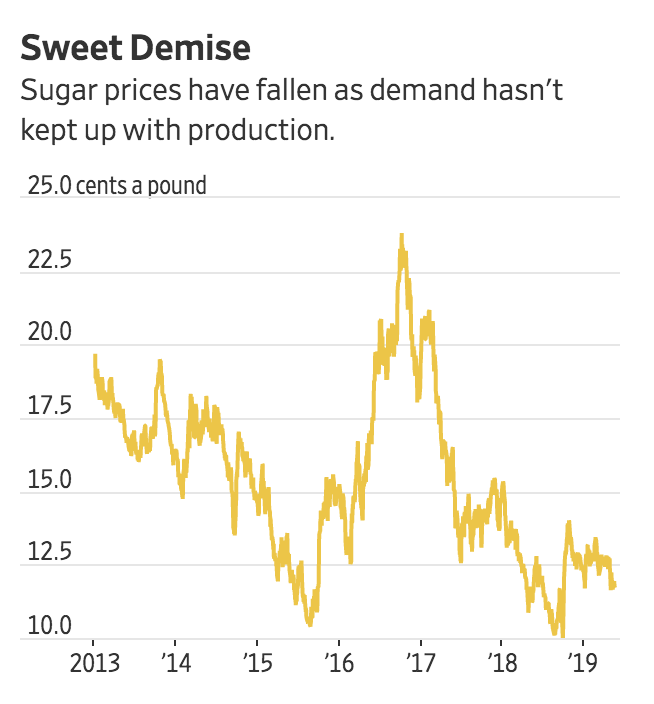

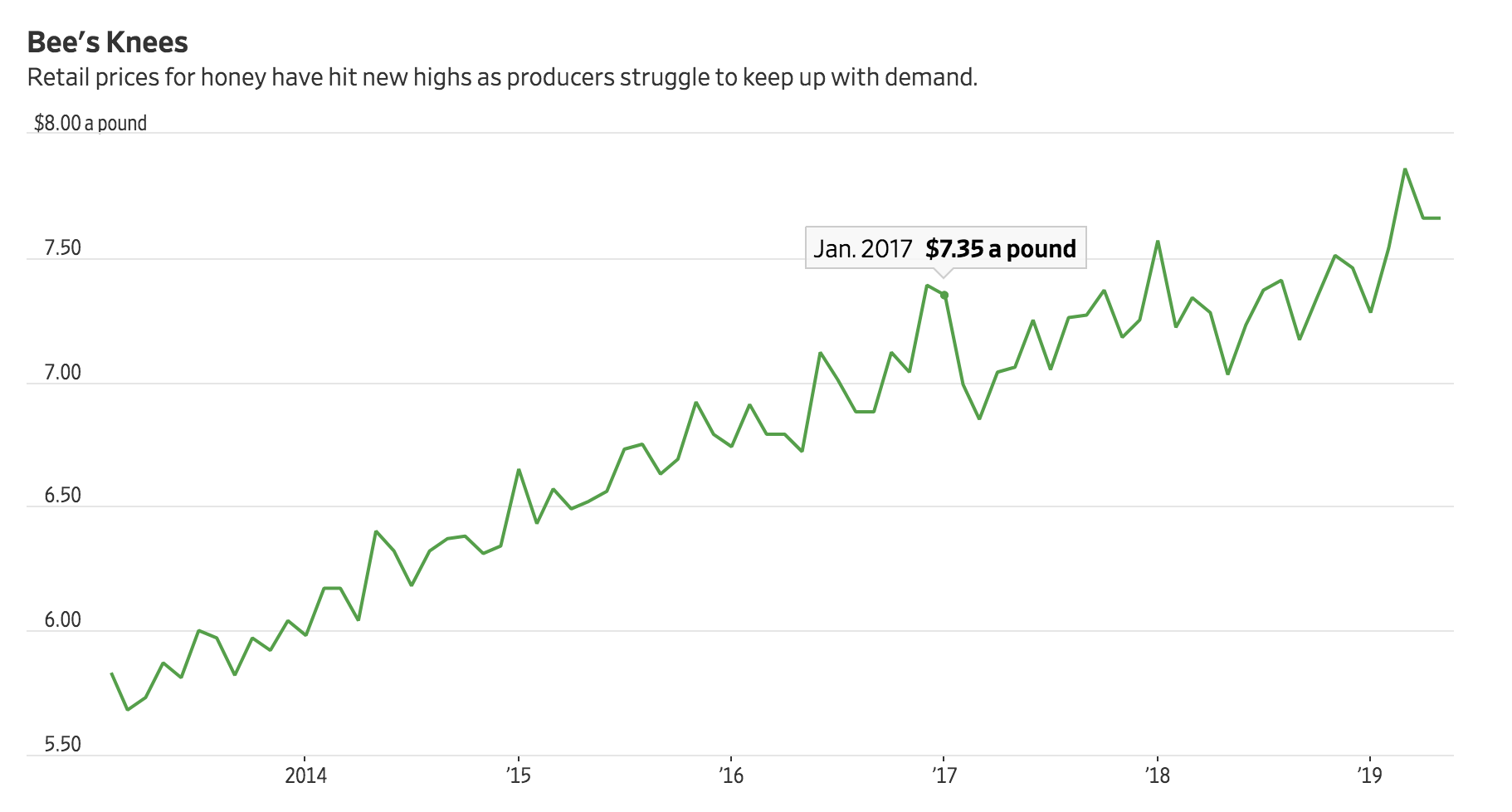

Retail honey prices world-wide recently averaged $4.69 a pound, according to market research firm Euromonitor International. Prices have climbed about 25% since 2013, while the cost of sugar has fallen around 30% over the same time frame.

And that is being reflected on American grocery receipts. U.S. retail prices averaged $7.66 a pound in May, up 9% from a year earlier, according to data cited by the National Honey Board, an industry group.

Those prices have risen by about two-thirds in the last decade, according to a survey of more than 150 retailers nationwide by Bee Culture magazine, a publication for American beekeepers.

Americans consumed 596 million pounds of honey in 2017, or an average of nearly two pounds per person—up 65% since 2009—according to a report from the University of California’s Agricultural Issues Center. About a quarter of the honey sold or used in the U.S. is produced domestically; the rest is imported.

At Kingsburg Honey, an organic farm in California’s Central Valley, about 100 hives produce roughly 1,500 pounds of honey a year. Its honey is sold at stores in the area for between $9 and $14 a pound.

“Honey really sells itself,” said Daren Hess, Kingsburg Honey’s owner. “It taps into the belief that it is healthy and wholesome and tastes good.”

Mr. Hess said there has been a notable increase in people searching for local honey and alternatives to other sweeteners.

One driver of rising honey prices is increasing demand for premium and raw honey, such as the Manuka variety that is produced in New Zealand and Australia.

It has been touted by celebrities—including tennis star Novak Djokovic—for its health benefits and numerous scientific studies have shown it can help heal wounds, ulcers and burns.

A 16-ounce jar of raw Manuka honey sells for $26.49 on American retailer Target Corp.’swebsite, versus $6.39 for a similar-sized container of Simply Balanced organic honey, one of the chain’s in-house brands.

The rising demand for honey comes as beekeepers are struggling to increase production. Global honey production has been relatively stable over the past five years, according to Norberto García, the Argentina-based president of Apimondia’s scientific commission on beekeeping economy. Apimondia is an international federation of beekeepers.

Beekeepers have been particularly afflicted by beehive colony collapses, a situation where a majority of worker bees disappear for unknown reasons.

Workers bees are females that gather nectar and pollen from flowers. They toil inside hives, making wax and feeding larvae, other bees and the queen. The nectar is stored inside a bee’s body and is passed around until it ends up as honey.

Some scientists believe bee populations have declined because of a disease caused by a parasite called the Varroa mite, in addition to pesticide usage.

The conversion of large swaths of land to industrial crop farms has also reduced the amount of food—pollen—that is available for bees.

In the U.S., honey production peaked in 2014 and has fallen 15% since then. Production totaled 152 million pounds last year, according to a report from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Beekeepers across the country have struggled with colony collapses as well as bee losses in winter ranging from 22% to 36% over the last eight years, the USDA said.

In Austin, Texas, Mark Bradley is a part-owner of a company that produces honey for farmers markets and small supermarkets in the area. He said that while he’d like to expand, it is hard to find areas suitable to house beehives.

“There is nothing but cotton or corn or soybeans for miles,” which means there isn’t much wild forage on which bees can hunt for pollen, Mr. Bradley said.

At The Humble Bee Honey Co. in Watertown, Conn., bees gather nectar from flower beds, vegetable gardens and fruit trees. The company produces honey, raw pollen and a skin care line that uses honey.

Mr. Hess And His Daughter, Anya, Walk Through The Orchard Where They Keep Some Of Their Bees And Process Honey.

Owner Catherine Wolko said she avoids mowing dandelions on her lawn to ensure her bees have enough food.

“My husband is a landscape designer and he hates it,” she said.

Updated: 1-24-2021

Bee Extinction Worries Grow As Species Numbers Drop

The number of reported bee species has dropped 25% from the 1990s.

Fewer bee species have been recorded since the 1990s, raising concerns that rare species might be extinct.

About 25% fewer species were found between 2006 and 2015, compared to records prior to the 1990s, according to a study published on Friday in the One Earth Journal. The authors are researchers at Argentina’s Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET).

“Something is happening to the bees,” said biologist Eduardo Zattara, the report’s first author. “It’s not a bee cataclysm yet, but what we can say is that wild bees are not exactly thriving.”

Wild and managed bees are essential pollinators that ensure the reproduction of thousands of wild plant species and 85% of all cultivated crops.

Mounting reports show that the decline in wild bee populations might follow, or even be more pronounced, than declines in insect populations. Many animal populations are decreasing drastically, scientists have recently warned.

Sightings of rarer types of bees have fallen more sharply than those of more common families, researchers found. Records of Melittidae, a bee family found in Africa, have gone down by as much as 41% since the 1990s, while Halictid bees, the second-most common family, have declined by 17% during the same period.

Most bee studies focus on declining populations focus on a specific area, or on a particular type of bee. Instead, CONICET researchers examined the number of species recorded around the world over more than a century.

To do that, they used the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, an international network of databases that contains over three centuries of records from museum specimens, universities and geotagged smartphone photos shared by amateur naturalists in recent weeks. The network accounts for over 20,000 known bee species all over the world.

The results are subject to some uncertainty mainly because of the variety of data sources, making it impossible to reach definitive conclusions on individual species, researchers said.

Technology has allowed for the recording of higher numbers of bees, but fewer species are being seen. Even accounting for possible distortions on the data, the trend is clear and matches that of previous, narrower reports.

“Given the current outlook of global biodiversity, it is more likely that these trends reflect existing scenarios of declining bee diversity,” the report said. “In the best scenario, this can indicate that thousands of bee species have become too rare; under the worst scenario, they may have already gone locally or globally extinct.”

Researchers conducted similar analysis on other insects to see if variations in bee species numbers were mirrored elsewhere, which would have been an indication that the changes had to do more with data collection and sources than with actual trends.

The populations of two wasp families also appear to be declining, but presented different patterns than bees’. Ant species, in contrast, have increased over the same period of time.

“We cannot wait until we have absolute certainty because we rarely get there in natural sciences,” Zattara said. “The next step is prodding policymakers into action while we still have time. The bees cannot wait.”

Updated: 1-14-2022

Urban Bees Face A Flower Deficit, Says Swiss Study

An examination of 14 cities in Switzerland adds heft to concerns that urban beehives can overtax city green spaces, potentially harming native pollinators.

A recent upsurge in urban beekeeping is outstripping some cities’ abilities to provide for their growing ranks of pollinators, a new study of cities across Switzerland indicates.

The number of registered beehives in 14 Swiss cities expanded from 3,139 in 2012 to 9,370 in 2018, says a new paper published in NPJ Urban Sustainability, part of the Nature portfolio of publications.

Yet none of those cities had adequate green space to support their bees, according to modeling by the paper’s authors, two ecologists from the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research.

“We’re adding thousands of beehives in a city without any knowledge of the available resources,” said Joan Casanelles Abella, a Ph.D. student who co-authored the paper with senior scientist Marco Moretti. “We just assume the city can provide because bees eat floral resources, and we perceive that there are unlimited flowers in the city.”

The researchers characterized their study as “a first attempt to quantify the sustainability of urban beekeeping.” Their results add statistical heft to skepticism that has emerged alongside a recent trend — the proliferation of honeybee hives on urban rooftops, often installed by beekeeping firms whose clients are companies looking to burnish their green credentials.

One concern with this arrangement, raised in an article earlier this week in CityLab, is whether the firms that install and maintain urban hives are taking adequate steps to make sure there’s enough forage for imported and native pollinators.

The honeybees can outcompete wild bee species, butterflies and other local insects that depend on city trees and plantings for food.

For their Nature study, the researchers compared beehive density in the Swiss cities with available green space — based on a model that one square kilometer of available green space could support 7.5 beehives.

Using that measure, the pair found that none of the 14 cities under inspection had enough forage to satisfy the appetite of all pollinators.

Previous studies had examined scenarios in Paris, London and Berlin, but none of these had compared data across more than one city, according to Casanelles Abella.

“There is not much apicultural research going on in cities because only a few collect sufficient data,” he said in an interview. “But the Swiss are super organized. Luckily, they force people to register their beehives, which allows for this kind of studies.”

Through his research, the Barcelona-born researcher hopes to coax authorities into implementing regulations around beekeeping, such as capping the number of beekeepers (or beehives) and ensuring a sufficient distance between apiaries.

Citizens can also play their part by adding more bee-friendly habitats with lots of nectar-rich flowers.

“Of course, you cannot recreate the natural habitat in the city,” said Casanelles Abella. “But you can at least do your best to promote as much biodiversity as possible.”

Updated: 12-18-2022

Saving The Bees Isn’t The Same As Saving The Planet

A high-tech beehive with a robot nanny shows humans’ capacity to adapt, but are we neglecting our most urgent responsibility?

When honeybees check into the Beewise “five-star hotel,” they don’t want to check out. A robotic arm attends to their every need. Hungry, sick or hot? Artificial intelligence software tells the robot to administer nutrients or antibiotics, to harvest honey or crank up the AC inside the high-tech hive.

The intensive care routine is designed to maximize the bees’ chance of survival and success against incredible odds, so they can continue to pollinate billions of acres of crops each year despite an overheating planet.

For decades, these crucial insects, which pollinate more than 75% of all fruits, vegetables and nuts cultivated worldwide, have been succumbing to severe human-caused stressors, including toxic pesticides, new diseases, and increasing heat.

Beewise, a 4-year-old startup based in Oakland, California, offers a particularly inspiring example of how robotics and AI might radically slow and even reverse the global honeybee die-off.

It’s a technological marvel of adaptation — so why did it leave me feeling disgruntled?

Beewise is a testament to our human capacity to solve even the most intractable problems. By now we know we must adapt to climate change: shifting how and where we live, modifying how we grow food and preserving the delicate balance of the ecosystems we depend on.

But all these coping measures raise another harrowing prospect: The more ingenious our adaptation tools, the more likely we are to avoid mitigating the core issues driving the crisis. We must do both.

Without a doubt, honeybees need our help now. The combined pressures of pesticides and disease along with crop monocultures that rob bees of essential nutrients and increasingly volatile weather have been driving Colony Collapse Disorder, a phenomenon that has been wiping out bee colonies at a rate of 25% to 30% a year for the past 15 years.

Now heat, drought and shifting seasons are making it worse. Last year, a major national study reported a whopping 45% annual die-off of commercial honeybee colonies.

While demand for bees in farming has grown exponentially in recent decades, the infrastructure for commercial pollination has evolved very little. Those iconic wooden boxes filled with screens of honeycomb have been in use since the 1850s, and they’re still the industry standard for commercial beekeeping.

Nearly all the new technologies that have emerged in the past decade to help bees adapt to modern stressors essentially just add sensors and cameras to these old wooden boxes.

That’s where Beewise saw an opportunity for disruption: Founder Saar Safra describes their new commercial hives as a kind of “five-star bee hotel.” The 10-foot-tall metal-clad, multilevel structures can hold up to 10 colonies.

On top of tending to basic needs, the units can sense when pesticides have been sprayed in a neighboring field and battens down the hatches, sealing off the insects from potential chemical drift.

So far, Beewise has raised $120 million and distributed 1,000 of its robotic hives to farms throughout California and Oregon. In four years, they have reduced the rate of collapse to less than 8% from 35% in the colonies they manage.

They hope to shrink that to a 2% loss as their AI systems come to better understand the needs of the bees. With demand for their product far outpacing supply, they aim to have 10,000 units in fields by the end of 2024.

Safra’s robotic bee hives are also amassing a vast storehouse of data on bee behaviors, stressors and solutions that could be a substantial asset down the line. Yet Safra, who grew up on a small Kibbutz in Israel, realizes that high-tech climate adaptation measures also have painful trade-offs.

“It’s a dilemma, that tension between mitigation and adaption,” Safra told me. “We realized early on that we don’t have a solution for solving climate change on our own, but we can help the bees survive. And it’s better to do something than nothing.”

That’s true. But it’s not the whole answer. Equal ingenuity and investment should be poured into reducing the environmental damage causing climate change.

For instance, while robotic beehives offer an immediate solution, longer term the industry should also be focused on alternatives to pesticide use, better mitigation of insect diseases, improvements in crop diversification to provide richer nutrients to beneficial insect populations — and of course, reducing emissions of methane and other potent greenhouse gasses while accelerating the phase-out of fossil fuels.

Mother Nature spent millions of years creating the most efficient pollinator on the planet. We owe it to the bees, if not to long-term human health and food security, to find ways to restore to them an environment where they can thrive, instead of simply treating climate change as inevitable.

Updated: 1-14-2023

A Biotech Startup Is Boosting Bee Endurance With Supplements

As environmental threats kill off honeybees, scientists are figuring out how to maximize the pollination potential of those that remain.

On a sunny afternoon in December, Angelita De la Luz placed a honeybee into a tube at a laboratory in Buenos Aires. Soon after, a pump released a small, scented puff of air and researchers watched for a very specific reaction: a scent that would make the bee stick out its tongue.

“This tells us that the bee recognizes the volatile we are testing as a meaningful signal from the plant; that there is good food to be found,” says De la Luz, who leads field testing at California-based biotech startup Beeflow.

A volatile is a floral characteristic that attracts honeybees, among other functions. Once Beeflow identifies the right one, De la Luz and her colleagues will develop it into bee feed used to “train” honey bees to pollinate targeted crops.

That training is part of Beeflow’s solution to a multibillion-dollar challenge facing farmers today. As extreme weather, habitat loss and pesticides continue to kill off honeybees, an insect critical for turning flowers into fruits, scientists are figuring out how to safeguard the remaining population and maximize its pollination potential.

For Beeflow, that means essentially crafting better diets for bees. Just like humans take supplements for their health, the company regularly feeds its honeybees a supplement designed to enhance their immune system.

Composed of amino acids collected from floral nectar as well as plant-based hormones, it allows honeybees to carry out as many as seven times more flights in cold weather, according to the company, and more than double their usual pollen load.

From there, Beeflow uses a different supplement to effectively set the bees’ “flight GPS” to specific crops.

So far, the company has deployed its solution across 10,000 acres of farmland in the US, Argentina, Mexico and Peru.

Beeflow says its pollination service has produced an average increase of 32% in crop yields compared to conventional farms, based on 50-plus field tests with blueberries, almonds and raspberries.

Since it was founded in 2016, the company has raised $13 million from investors that include Ospraie Ag Science, SOSV and Grid Exponential. It’s in the process of securing more funding to scale up operations.

Over the past two decades, the bee population has been declining all over the world. Habitat loss, toxic pesticides and, increasingly, a changing climate are impacting various species of wild bees, including bumblebees. But even honeybees under the care of commercial beekeepers are affected.

In the US alone, beekeepers lost an estimated 39% of their honeybee colonies over the 12 months ending in April 2022, according to an annual survey. Roughly two thirds of the world’s crops rely on honeybees and other pollinators, and one recent study found that insufficient pollination is causing about 500,000 early deaths a year.

Several companies are working to find a fix. Boston-based GreenLight Biosciences developed a vaccine to protect honeybees from a deadly parasite. In Ireland, ApisProtect installs in-hive sensors to alert beekeepers when unhealthy bees are identified.

Veon Ltd, Russia’s third largest mobile-phone company, offers a warning system for pesticide distribution, a main cause of death for Russian bees.

Beeflow, for its part, is tackling just one part of the challenge: getting honeybees to do more work in cold weather.

While honeybees naturally become less active as temperatures drop, more frequent cold snaps caused by climate change mean that beekeepers and growers will have to find ways to overcome that limitation.

Once Beeflow has made a bee stronger, it must then ensure the bee is applying its strength to the targeted crop, with no wildflower distractions along the way.

That’s accomplished by giving the bees a treat — specifically, sugar syrup — whenever they’re exposed to the scent associated with the crop they need to pollinate.

Matias Viel, founder of Beeflow, likens this conditioning to Ivan Pavlov’s classic experiment in getting dogs to salivate at the sound of a bell. Since honeybees have short memories, Beeflow resets their conditioning every two weeks during pollination season.

It took Beeflow more than three years and over 1,000 lab tests to identify and create a synthetic version of the exact floral volatile of blueberry that signals food for honeybees, De la Luz says. But the startup’s patience appears to be paying off.

Beeflow says its two supplements, combined with strategic placement of beehives in farmland, help increase blueberry yields by up to 60%. The company also offers commercial pollination services for almonds and cherries, and says it has seen increased yields for both.

“It’s the most promising technology that I’ve seen,” says Lisa Wasko DeVetter, an associate professor at Washington State University who specializes in small fruit cultivation and has been tracking Beeflow’s field work since 2021.

Last year, DeVetter found that Washington state blueberry farms deploying Beeflow technology produced fruits 30% larger in size than those without it.

DeVetter says more research is needed to assess the technology’s overall impact on bee health. Getting farmers on board could also be an uphill battle, she warns, as conventional pollination practices have dominated farmland for decades.

The price tag doesn’t help, either: Beeflow charges $750 per acre for blueberry pollination in states such as Washington, roughly three times higher than conventional pollination services there.

Beeflow’s Viel says the company’s growing body of field tests is helping convince growers, as is the constraint on fertilizer supply prompted by the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The company has yet to turn a profit, and won’t disclose its revenue, but Viel says it expanded its workforce to more than 40 people this year, up from 12 employees in 2020. Beeflow is eyeing further expansion in the US next year, and aims to enter the European market by 2025.

The company’s scientists are also working on its next wave of supplements. “The next one that is coming is avocado pollination,” Viel says. Popular among consumers, avocados stand to lose up to 41% of their ideal growing areas to climate change by mid-century.

Updated: 2-28-2023

Refrigerated ‘Queen Banks’ Could Help Save Honeybees

A new study finds that queen bees held in a refrigerated container have a higher chance of surviving a hot summer than those stored outdoors.

In the perennial search for a viable queen honeybee, many US beekeepers replenish their supplies each autumn. But meeting that demand is increasingly difficult: Honeybee populations are in decline, partly due to climate change.

Colony health largely depends on queens, and most US queen producers are located in California, where rising temperatures and wildfires are becoming the new norm.

A new peer-reviewed study in the Journal of Apicultural Research presents one possible solution in refrigerated “queen banking” — essentially keeping excess queen bees in temperature-controlled summer housing.

Scientists from Washington State University compared bee survival rates across 18 “queen banks,” roughly half of which were stored in a 20-foot temperature-controlled cargo container at 15°C (59°F); the other half were kept outdoors in northern California, where summer highs can reach 42°C (108°F).

The researchers found that about 78% of the queen honeybees survived six weeks of storage in the refrigerated container, compared with roughly 62% of those kept outdoors.

The temperature-controlled bees also required less human care, and the study identified no significant differences in the quality of the remaining bees in both groups.

“This is a neat approach to queen banking,” says Scott McArt, an assistant professor at Cornell University who is not involved with the study. “Poor queens are one of the biggest problems in beekeeping today, so novel tactics like this could greatly help improve the country’s beekeeping industry.”

Bee solutions like these matter for humans, too. Experts say traditional outdoor queen banking could become a challenge once temperatures reach 100F (37.8C), for example, and roughly two thirds of the world’s crops require the service of honeybees and other pollinators.

Scientists are scrambling to reverse the impacts of habitat loss, toxic pesticides and changing climate conditions on various species of wild bees, including bumblebees.

Even honeybees under the care of commercial beekeepers are affected: In the US alone, beekeepers lost an estimated 39% of their honeybee colonies over the 12 months ending in April 2022, according to an annual survey.

“A lot of honey bee losses are queen-quality issues,” says Brandon Hopkins, the study’s co-author and an assistant research professor at Washington State University, in a press release on Monday.

“If we have a method that increases the number of queens available or the stability of queens from year to year, then that helps with the number of colonies that survive winter in a healthy state.”

Updated: 3-29-2023

How’s Your City Doing? Ask the Honeybees

Our neighborhood bees possess valuable information about a city’s health that could benefit everything from pathogen surveillance to environmental justice.

For scientists studying the health of a city and its inhabitants, their most powerful tool may just be the honeybee.

That’s because when honeybees go foraging, they collect more than just pollen and nectar. As they navigate through their environment, microorganisms and other tiny particles can also cling to the bees’ fuzzy little bodies, which the pollinators then shed as they enter their hives.

And since pollinators tend to forage within a mile radius of their hives in urban areas, there’s valuable information about a city or even a neighborhood in the honey they produce, on their bodies and in the debris that lies at the bottom of hives.

“Honeybees will gather a vast number of microbes day to day, far beyond things they are seeking out. They’ve been optimized by evolution to do everything that the swabs do,” said Kevin Slavin, a professor at MIT Media Lab, during a press briefing on a new report in the journal Environmental Microbiome.

The new research aims to establish a feasible method for collaborating with beekeepers and their colonies of honeybees for the purpose of studying the microbiome of cities.

A microbiome is the unseen communities of microbes, fungi, viruses and bacteria that live inside and around us, playing key roles in the functioning and health of the urban environment and the human population, as well as plants and animals. Previous research has linked exposure to a diverse microbiome to better health outcomes.

In the near future, understanding microbial environments can become crucial to understanding the many ways in which health and environmental inequalities disproportionally affect marginalized communities, said Slavin.

“We tie that, currently, to things like pollution or even shade, [but] the idea is in part just to collect as much data as we can, far beyond straightforward pathogen screening, to better understand what produces healthier neighborhoods, and can it be measured.”

To test if bees can be used to “swab” the city, Slavin and a team worked with local beekeepers to collect and analyze microbes from samples of honey, honeybee parts, and debris from hives across five global cities — New York, Venice, Tokyo, Melbourne and Sydney — using the information to uncover insights about the unique and diverse microbial footprint of each place.

The study began in New York City, where researchers compared microbes from three different neighborhoods — two in Brooklyn and one in Queens — to show how microbes might differ from one neighborhood to another.

They were able to find a diversity of species, including bacteria associated with plants and the larger environment, as well as human-related pathogens. The material gathered from hive debris varied the most among the three locations.

Meanwhile, in Venice, where many buildings sit atop wooden piling submerged in water, sample data consisted of fungi related to wood rot, for example. And in Tokyo, the researchers found genetic traces of a fermenting yeast used in the production of soy sauce and miso paste.

“Cities have their own microbial signatures, which are also interestingly related to the cultural and geographical context in which those cities have emerged,” said co-author Elizabeth Hénaff, a computational biologist at the New York University Tandon School of Engineering.

“It didn’t feel like a disjointed metric from all of the other things that we know about these cities,” she added. “It actually kind of felt like a puzzle piece that we didn’t even know existed.”

More than that, the study also demonstrated how the materials gathered from beehives could potentially aid health officials in pathogen surveillance.

Using multiple samples collected from Tokyo, researchers were not only able to identify the pathogen Rickettsia felis — responsible for the bacterial disease known as “cat scratch fever” — but do further analysis to determine the genetic factors that enable it to infect its hosts.

There are currently multiple methods for studying the microbiome of a city, including testing wastewater, which has been used to detect the presence of drugs and more recently to understand the spread of Covid-19 in communities.

But the researchers say that method focuses on things that humans have processed.

“What about the city or a neighborhood as a whole?” said Slavin. “What about everything that isn’t processed by humans?”

Related Articles:

Carolyn’s Natural Organic Handmade Soap

We Now Live In A World With Customized Bar Soaps, Lotions And Shampoos (#GotBitcoin?)

Why Interior Designers And Home Stagers Prefer Bar Soap Over Liquid (#GotBitcoin?)

Fighting Cancer By Releasing The Brakes On The Immune System (#GotBitcoin?)

Over-Diagnosis And Over-Treatment Of Cancer In America Reaches Crisis Levels (#GotBitcoin?)

Cancer Super-Survivors Use Their Own Bodies To Fight The Disease (#GotBitcoin?)

Understanding The Gut Microbiome

Food, The Gut’s Microbiome And The FDA’s Regulatory Framework

Germ-Killing Brands Now Want To Sell You Germs (#GotBitcoin?)

Pocket-Sized Spectrometers Reveal What’s In Our Foods, Medicines, Beverages, etc..

Your Questions And Comments Are Greatly Appreciated.

Monty H. & Carolyn A.

Go back

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.