Satellites Put The World’s Biggest Methane Emitters On The Map For Public Scrutiny #BitcoinFixesThis

Now the companies and countries responsible for a powerful greenhouse gas won’t be able to hide from view. Satellites Put The World’s Biggest Methane Emitters On The Map For Public Scrutiny #BitcoinFixesThis

Orange and yellow pixels flash over American drilling heartlands around the Gulf Coast, New Mexico, and Pennsylvania. Dark red stretches across Middle East and China, while disturbing dots of color pop up around Greenland’s coast.

This is the dangerous world of atmospheric methane emissions, one of the most powerful drivers of global warning—and it’s visible to the public for the first time.

Related:

Why Bitcoin Mining Is Being Touted As A Solution To Gas Flaring

Mining Bitcoin With Flared (Wasted) Gas

GHGSat Inc. released a new methane map on Wednesday that uses data from the company’s two satellites, which were launched earlier this year and can detect methane emitted by oil and gas wells, coal mines, power plants, farms and factories.

“We’ve got a situation where for more than the last decade there’s been a significant and unexplained upward tick in global methane atmospheric concentrations,” said Jonathan Elkind, a senior research scholar at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy.

In a paper published last week, Elkind outlined the way satellite-driven transparency will better allow investors to identify which companies aren’t backing their goals with action.

The time-lapse map published by GHGSat covers a six-month stretch through October 10—less than two weeks ago—based on weekly images captured from space. Average methane emissions are represented in green, at about 1,800 parts per billion, with yellow above average and dark red at the high end of the scale.

The early readings cover the lockdowns that aimed to slow the Covid-19 pandemic, which devastated demand for oil and sent methane emissions lower. Intensification on the map shows how quickly methane can build during the hot summer months in the Northern Hemisphere, with orange and red pixels along the Arctic coast and around Beijing.

The map identifies concentration of methane across the troposhere, where naturally occurring emissions such as from wetlands mingle with those caused by human activity. Mountains can be seen trapping methane, such as in Southern California near the Sierra Nevada range or in South Asia below the Himalayas.

Methane is more than 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide over a 20-year period, although its greenhouse impact fades much faster.

GHGSat claims its satellite offers the highest-resolution methane data publicly available, and the it sells access to companies ranging from Royal Dutch Shell Plc to landfill operators. In the next year, GHGSat plans to release additional data that will also quantify emissions, said Stephane Germain, president of the Montreal-based firm.

That will make it clear how much methane is released by drilling in the U.S. Permian Basin every week, for example. The company is also developing a carbon dioxide-monitoring satellite that may be launched into orbit in 2022.

Satellite data will ultimately transform the way nations are held accountable for voluntary commitments under the Paris Agreement, which calls for limiting global average temperatures from rising more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

Granular data that can pinpoint emissions down to specific facilities will also help track corporate emissions. “Very soon nobody is going to be able to hide from methane leakage,” former BP Plc Chief Executive Officer Bob Dudley predicted in 2018.

Other organizations are also working to root out unknown emissions leaks. The Environmental Defense Fund, Harvard University and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory are developing MethaneSat, a project to measure human-made emissions by satellite and supply that data to the public.

About MethaneSAT

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, with more than 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide over the first 20 years after it is released. At least a quarter of today’s global temperature increases are caused by methane from human sources. And one of the largest sources of these emissions today is the oil and gas industry.

Cutting oil and gas methane emissions is the single fastest, most impactful thing we can do to slow the rate of warming today, even as we work to decarbonize our energy system. Reducing oil and gas methane emissions 45% by 2025 would have the same 20-year climate benefit as closing 1,300 coal-fired power plants.

MethaneSAT will provide regular monitoring of regions accounting for more than 80% of global oil and gas production, identifying not only the location but also quantifying the emissions rate with unprecedented precision — giving MethaneSAT the ability to monitor changes in total emissions over time. MethaneSAT will also be able to measure methane from industrial agriculture and other sources.

Unique Capabilities

MethaneSAT will locate and measure methane emissions from oil and gas operations almost anywhere on Earth, producing quantitative data that will enable both companies and countries to identify, manage, and reduce their methane emissions, slowing the rate at which our planet is warming.

Other satellites can either identify emissions across large geographic areas or measure them at predetermined locations. MethaneSAT will do both. It will cover a 200-kilometer (124-mile) view path, passing over target regions every few days. Along with a wide field of view, the instrument will provide highly sensitive, high-resolution methane measurements.

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, with more than 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide over the first 20 years after it is released. At least a quarter of today’s global temperature increases are caused by methane from human sources. And one of the largest sources of these emissions today is the oil and gas industry.

Cutting oil and gas methane emissions is the single fastest, most impactful thing we can do to slow the rate of warming today, even as we work to decarbonize our energy system. Reducing oil and gas methane emissions 45% by 2025 would have the same 20-year climate benefit as closing 1,300 coal-fired power plants.

MethaneSAT will provide regular monitoring of regions accounting for more than 80% of global oil and gas production, identifying not only the location but also quantifying the emissions rate with unprecedented precision — giving MethaneSAT the ability to monitor changes in total emissions over time. MethaneSAT will also be able to measure methane from industrial agriculture and other sources.

An imaging spectrometer will separate the narrow band within the shortwave infrared spectrum where methane absorbs light, enabling MethaneSAT to detect methane concentrations as low as two parts per billion, and focus in on areas as small as 100 meters.

Once the raw information is transmitted back to Earth, an innovative data platform will automate complex analytics, transforming a process that now takes scientists weeks or months into one that provides users with a continuous stream of actionable data in a matter of days.

The platform algorithms will calculate the rate that methane is escaping into the atmosphere based on winds and other atmospheric conditions, determining the location and volume of methane coming from individual point sources as well as cumulative emissions across larger areas.

Unique purpose

MethaneSAT LLC is a wholly-owned subsidiary of the non-profit Environmental Defense Fund, which has a long record of working successfully with both businesses and policymakers to create innovative, science-based solutions to critical environmental challenges. EDF has also been a leader in methane research, policy and management practices.

Beginning in 2012, EDF organized an unprecedented series of 16 independent studies that produced more than 50 peer-reviewed scientific papers involving more than 150 academic and industry experts to assess methane emissions at every stage in the U.S. oil and gas supply chain. A 2018 synthesis of the work published in Science found that the U.S. oil and gas industry was emitting at least 13 million metric tons of methane a year—nearly 60% more than government estimates at the time.

MethaneSAT is intended to both enable and motivate faster action to reduce these emissions. With many oil and gas companies starting to set methane reduction goals and a growing number of states and countries looking to strengthen methane policies, the need for accurate, high-resolution quantification of total emissions that can be tracked over time has never been greater.

But the data won’t be just a tool for industry and governments. The mission was also founded on the principle of transparency: making data available at no cost so stakeholders and citizens can see and compare the progress across both companies and countries.

The idea for MethaneSAT was first unveiled by EDF President Fred Krupp in an April 2018 TED Talk, as one of the inaugural group of world-changing ideas selected for seed funding by the Audacious Project, successor to the TED Prize.

NASA is designing a stationary satellite called GeoCarb to collect 10 million daily observations of the concentrations of carbon gases across the Americas.

New insights into methane emitters have already prompted regulatory action. Earlier this year, the Environmental Protection Agency launched an investigation into Florida Gas Transmission Pipeline for a possible Clean Air Act violation after Bluefield Technologies Inc. discovered a mystery leak using satellite imagery, and Bloomberg News identified the likely source.

Last year, GHGSat found a giant methane plume in Central Asia oilfield; getting it stopped was the equivalent of taking 1 million cars off the road.

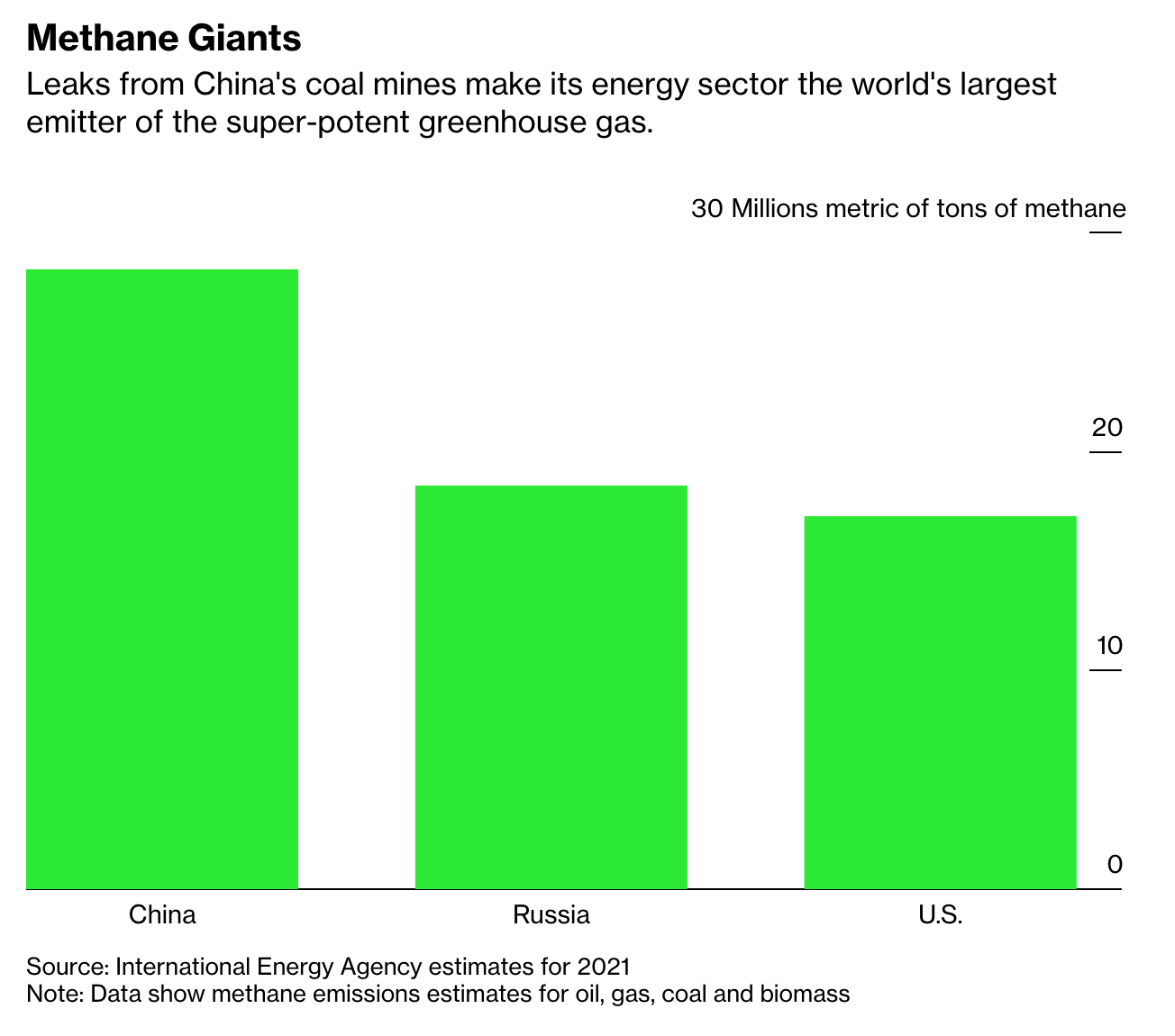

Some trends are already visible in the new GHGSat map. China appears to have above-average background readings for natural reasons, Germain said, but methane emissions from rice paddies and coal mines may also contribute to the red zones. Germain noted that China is home to 10,000 of the world’s 12,000 coal mines.

As expected, areas with high levels of oil and gas drilling activity—from West Texas and New Mexico to the Caspian Sea and parts of the Persian Gulf—show higher levels of methane, likely caused by leaks and flaring. But there are also high methane levels in parts of northern Canada and Siberia with little to no industrial activity.

It’s also unclear what’s causing red zones to emerge across the Sahara desert, Germain said, and it’s possible that increasing concentrations in Saudi Arabia may partly be the result of winds carrying methane from other regions, not just the local production of fossil fuel.

“If you are a company and you see more red in the areas that you operate in, you should care,” said Germain. “A very small number of sites are responsible for the vast majority of man-made emissions globally. If you can find those industrial emissions, you can have a significant impact.”

Investors Gauge Future Climate Risks With Satellite Imaging

Asset managers are analyzing pictures and data taken from outer space to predict the physical impacts of global warming.

The world was watching end-of-days scenes: Firefighters in yellow jackets, blurry against a copper sky, battled to push back walls of flames. Veterinarians tended to badly burned koalas and kangaroos. Dazed survivors picked through the ruins of their torched houses.

Chris Kaminker was one of the many remote onlookers unnerved by the images of Australia’s most recent bushfires. In London, where he leads sustainable investment research and strategy at $65 billion Lombard Odier Investment Managers, Kaminker couldn’t escape the thought that he’d seen this apocalyptic vision before.

Indeed he had—a 2008 report commissioned by the Australian government had predicted that by 2020 climate change would cause the country’s fire seasons to start earlier, end later, and be more intense.

“The physical reality leaping off of the pages of scientists’ reports that warned us decades ago was simply shocking to behold,” says Kaminker, a 37-year-old dual U.S.-French citizen. “What struck home was the realization that the scientists really did get this right, sadly.”

So why hadn’t financiers like Kaminker been better prepared for the extent of the damage to life and assets? Something must have been missing in the data. This is where Kaminker believed he could add some value.

An alum of Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and Société Générale SA, Kaminker ran sustainable finance research at SEB, the Swedish bank that structured the first green bond, before joining the asset management arm of Swiss private bank Lombard Odier last year.

In a newly created role, he was responsible for developing ways to analyze how the warming planet—and increasing pressure to cut carbon emissions—will affect companies. The idea was, of course, to give the firm’s funds a unique investment advantage.

Kaminker made two big moves. First, he dedicated himself to building expertise in a field known as physical risk, which involves understanding and predicting the potential damage to assets and infrastructure from a changing climate and extreme events.

The Central Banks and Supervisors Network for Greening the Financial System, an international group of institutions aiming to address global warming, said in June that as much as 25% of the world’s gross domestic product could be wiped out by losses from physical damage alone by 2100 if no further action is taken on climate change.

Second, he recruited Laura García Vélez from the World Wildlife Fund conservation group as a geospatial analyst, tasked with studying satellite images, geographic information system data, and historical cartographic records.

Vélez, 31, first learned about geospatial techniques while working for a utility in her hometown of Medellín, Colombia, where she assessed how suitable locations were for hydropower plants. Growing up in a country that’s both lush in rainforests and full of minerals and energy resources made Vélez see climate change as more than a scientific phenomenon or an investment strategy.

“What tends to happen is that the places that have more biodiversity and are more important in terms of their ecosystems are also places which are very rich in natural resources. So it’s really difficult to just put in place those trade-offs if a country is developing and its economy depends substantially on commodities,” she says.

At WWF, Vélez was a key contributor to a joint report with Investec Asset Management (now called Ninety One) that explained how geospatial data and satellite imagery could detect warning signs for a sovereign debt portfolio by spotting potential environmental hazards and countries’ progress in managing them. In July, Ninety One, which manages £118 billion ($153 billion) in assets, launched a country risk index with WWF that builds on that research.

Vélez joined Kaminker in January, and they began studying the Australian fires. They were frustrated with the widely used climate models produced by the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project, or CMIP, which receives contributions from at least a thousand researchers and is cited in United Nations reports.

They found the CMIP models failed to show that huge fires would ravage New South Wales, the southeastern state that’s home to Sydney, with such ferocity. They became convinced that geospatial analysis could do more than help calculate the damage from extreme events—it could help forecast where these calamities might occur.

New Space Race

It’s been almost 75 years since the first photo of Earth was taken from space. Insurers have used satellite data since the 1990s to model flood and hurricane risks; commodity traders and some hedge funds have used the images to track traffic at shopping malls and monitor usage of oil storage facilities.

The cost of launching a payload into space has fallen significantly—by a factor of 20 since the 2000s, according to one estimate—and now many more satellites are in orbit, pinging back an ever-larger volume of images. Virtually every building and tree on the planet is under daily surveillance. Computing breakthroughs, most notably developments in artificial intelligence, have made the tools to interpret and analyze the data much more readily available.

And we’re just at the start of this new space race for financial data, says Rowan Douglas, head of Willis Towers Watson’s Climate and Resilience Hub. Douglas predicts that within five years spatial techniques will be deeply embedded in financial and risk analysis across the industry.

But there are limitations. The cost of purchasing data from satellite providers remains high, according to Kaminker. And, while satellite imagery of any point on the planet is available, there isn’t yet any corresponding or interlinked database showing who owns each piece of property. Investors may struggle to gain a full picture of a company’s impact on the environment or vice versa.

There are projects under way to remove some of these roadblocks. For instance, the U.K.-based Spatial Finance Initiative is working to make geospatial capabilities widely available for financial decision-making. It plans to introduce a database of the location and ownership of global cement and steel facilities by the end of 2020, says Ben Caldecott, a founder of the initiative and founding director of Oxford’s sustainable finance program.

Kaminker and Vélez developed an alternative to the CMIP models by compiling data on local temperature, rainfall, wind speeds, and humidity from meteorological agencies, adding their own analysis of images from satellites.

After doing backtest trials, Kaminker and Vélez determined that the images could have predicted, with some degree of certainty, the location and severity of the Australian fires a month before they occurred.

So Lombard Odier Investment Managers began making greater use of satellite data and Earth observation, and physical risk analysis has become one of its key inputs in investment decisions.

Kaminker declined to provide details on the specifics of its current portfolio, but he said physical risk and geospatial data were material factors in decisions related to California utility PG&E, U.S. timberland company Weyerhaeuser, Brazilian iron ore giant Vale, and Brazil’s JBS, the world’s biggest meat company.

Seeking An Edge

Once seen as a peripheral topic for money managers, climate change has become a material element in investment decisions. BlackRock Inc.’s Chief Executive Officer Larry Fink said in his annual letter to CEOs in January that “climate change has become a defining factor in companies’ long-term prospects” and would bring about a “fundamental reshaping of finance.”

For most fund managers this manifests as a focus on incorporating environmental, social, and governance factors in their investment decisions—buying and selling stocks based on how well they score on factors such as carbon emissions.

Now firms such as Lombard Odier are seeking an edge with a view from space. Instead of waiting for a company’s annual sustainability report, they’re using satellite images to get a real-time picture of its emissions. In this way they’re measuring and managing risks, but also arming themselves with more accurate data to push companies and governments for change.

In March, Lombard Odier created a climate transition fund. The strategy, with more than $500 million under management, invests in companies that will profit from the move to a lower-carbon world—either by creating solutions to curb greenhouse gases or making aggressive efforts to cut their own emissions.

The fund also includes companies building infrastructure for a warmer planet or those that monitor physical and financial risks related to climate damage. Its biggest holdings include engine maker Cummins, grocer Kroger, sports apparel manufacturer Nike, and carmaker Volkswagen, according to a Lombard Odier spokesman. The fund returned 13% in the three months to mid-October.

Meanwhile, Kaminker and his 10-person team are working on a host of additional tools to analyze the exposure and resilience of companies to climate change, including one that assesses the extent to which more than 23,000 companies are aligned with the temperature goals of the Paris climate agreement.

Kaminker says 10 years ago he’d have never imagined he’d be doing the work he’s doing today. “I’m a finance guy, I am not a climate scientist,” he says.

“This is about risks and returns. We’re not doing this for many other reasons. It’s primarily because we’re an investment institution, and these issues could be material to financial considerations.”

Updated: 4-19-2021

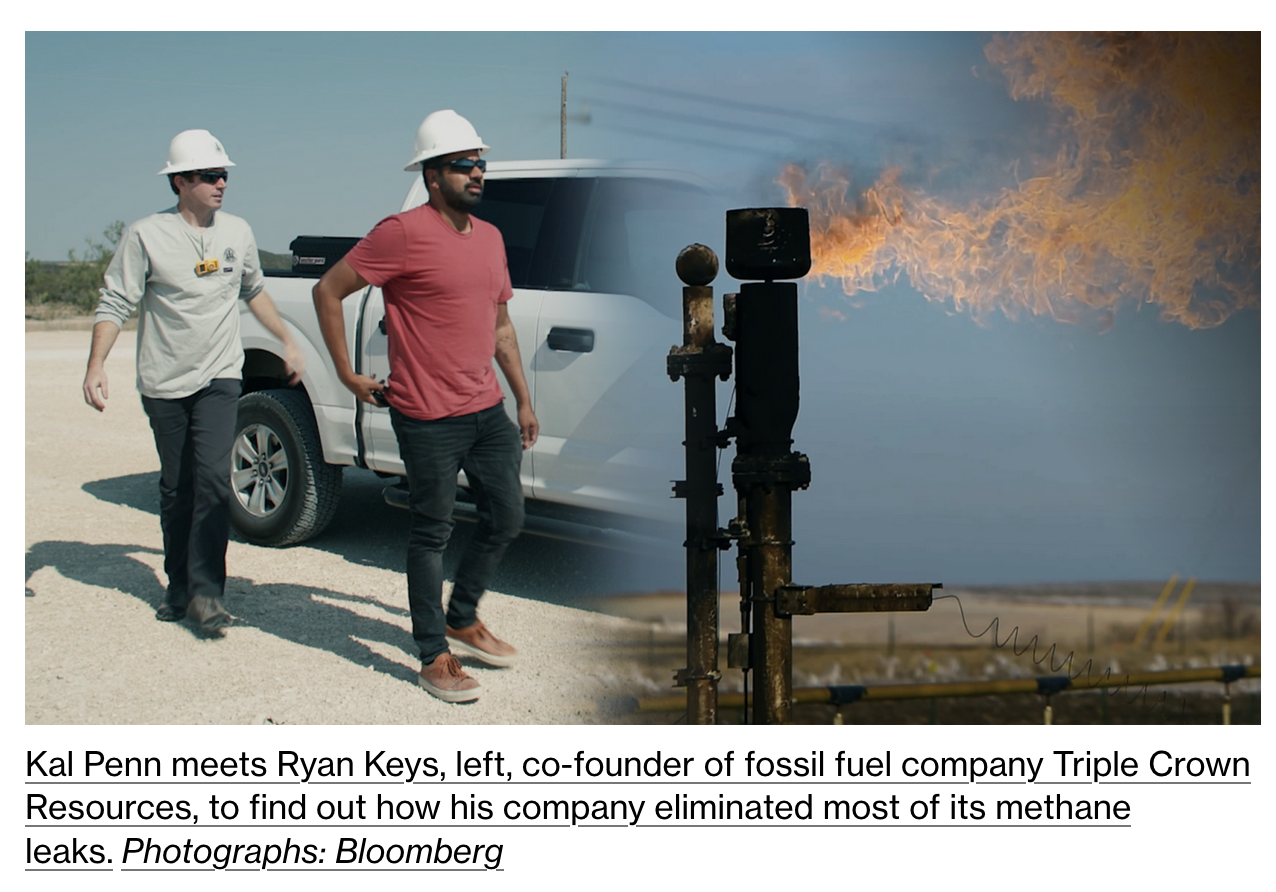

The Tech Tracking Down Methane Leaks

From satellites to drones to cameras, here’s the gear helping scientists, activists, and regulators crack down on harmful methane leaks around the world.

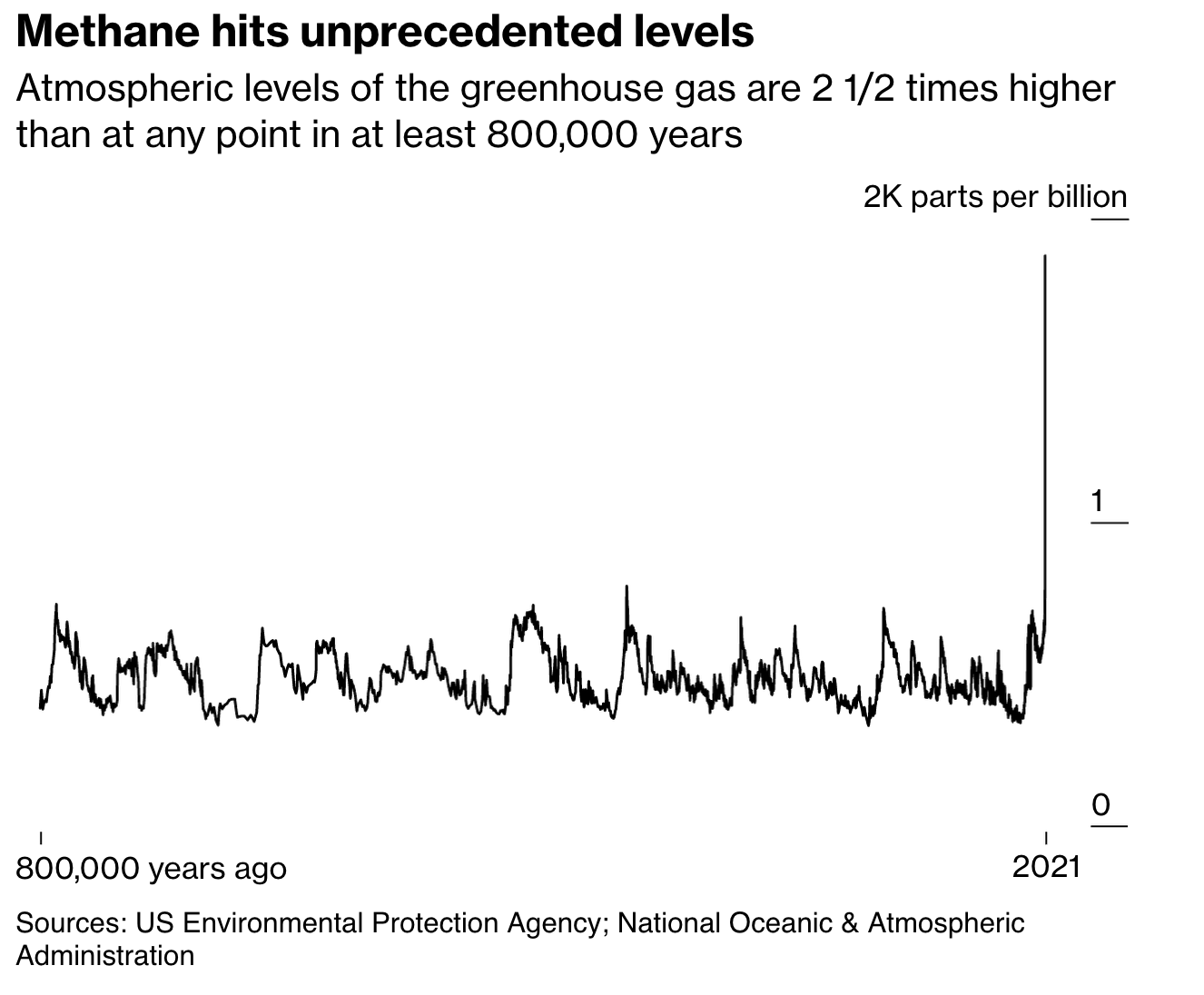

In the fight against global warming, methane has flown under the radar for years as activists and scientists focused on curbing carbon dioxide emissions. But this odourless and colorless gas is about 80 times more potent than CO2 in the first two decades after getting released into the atmosphere, and in recent years it has jumped to the top of everyone’s climate to-do list.

President Joe Biden is considering singling out methane for significant reductions as he prepares to unveil an ambitious pledge to cut all greenhouse gasses. China’s five-year plan announced in March included its first-ever pledge to contain the gas.

The United Nations and European Commission expect to publicly launch their International Methane Emissions Observatory later this year to speed efforts to tackle this problem around the world.

The need for action became evident earlier this month, when the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said the increase in global atmospheric methane concentrations last year was the biggest on record – a sharp contrast to the pandemic-fuelled drop in carbon emissions.

One of the most effective ways to restrict methane is to stop energy companies from releasing it. It’s the primary component of natural gas, and producers have a lot of incentive to do their part – leaks from faulty equipment are both wasted product and a potential source of reputational damage.

For some oil companies, when emissions are a byproduct of the production process, there can be less urgency to contain them.

The big challenge in stopping these emissions, though, starts with identifying them in the first place.

Fortunately, detection devices have come a long way since the days when operators sprayed soap onto pipes or threw a tarp over equipment to check for leaks. Microwave-sized satellites and sensor-equipped cars are among the many innovations that promise a new era of climate transparency.

SPACE

Satellites have been detecting large methane plumes for years, but until recently the images were no more than a blob spread over a wide area. A breakthrough came in October 2017, when the European Space Agency launched the Sentinel-5 Precursor.

This effort enables more-refined images that can help identify the biggest leaks. The ESA also distributes its data for free, fostering a constellation of startups that analyze the output.

There are gaps in current satellite capabilities, such as when clouds are present or when facilities are offshore. Nevertheless, more advances are on the way, with the promise of ever-greater granularity.

Updated: 4-22-2021

Appalachia Spews More Methane Than Permian, Satellite Data Show

The Appalachian Basin spanning Alabama to Maine spewed more methane last year than the oil- and gas-heavy Permian Basin of Texas and New Mexico — making the region the biggest emitter of the greenhouse gas in the nation.

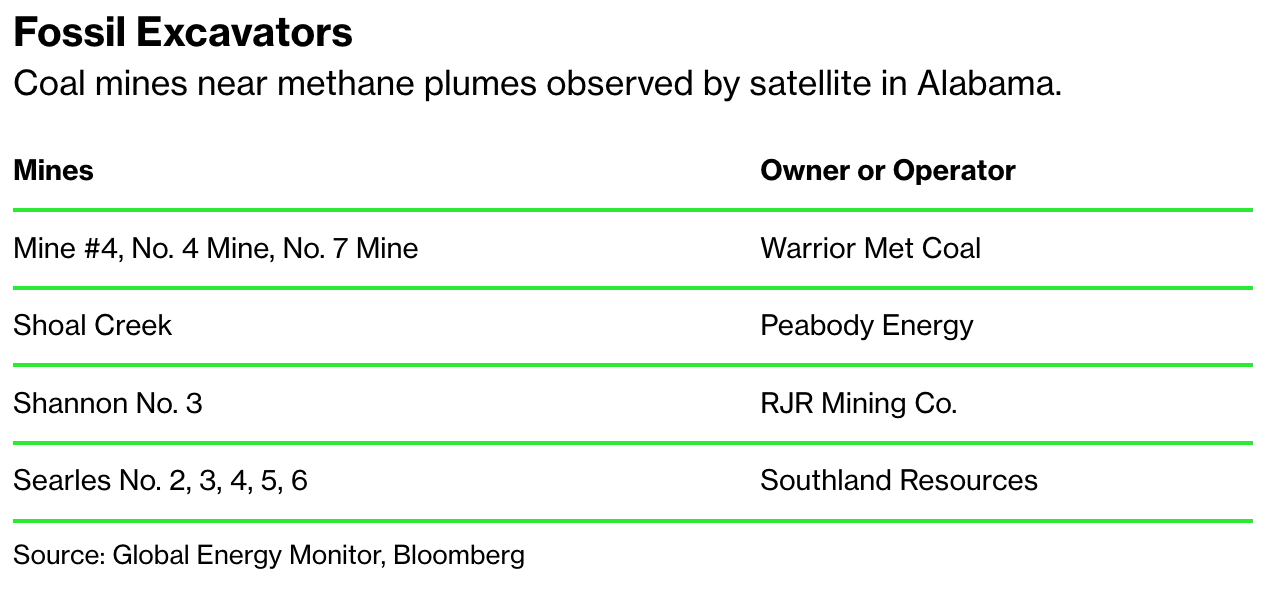

Satellites recorded 2.4 million tons of methane emissions in the Appalachian basin in 2020, compared with 2 million tons in the Permian, according to data from Kayrros. Nearly 42% of the Appalachian pollution came from coal mines, while the Permian emissions were tied to oil and natural gas production, the satellite-data company said in a statement.

With methane 84 times more potent than carbon dioxide, the Appalachian emissions are equal to the annual pollution of around 30 million cars. Emissions fell by 20% in Appalachia and by 26% in the Permian in 2020, due to the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on energy demand, Kayrros said.

Updated: 4-25-2021

Leaking Landfill Contributes To World’s Mystery Methane Hotspot

A landfill in Bangladesh is leaking huge quantities of the potent greenhouse gas methane into the atmosphere, according to the emissions-tracking company GHGSat Inc.

An April 17 observation from the company’s Hugo satellite shows a methane release originating from the Matuail Sanitary Landfill, said GHGSat President Stephane Germain. The company estimated the emissions rate at about 4,000 kilograms an hour, the planet-warming equivalent of running 190,000 traditional cars. The country’s environment ministry said it’s investigating.

Bangladesh has been a hotspot this year for emissions of methane, a colorless, odorless gas that’s about 84 times more potent than carbon dioxide in the first two decades in the atmosphere. Scientists and government officials are seeking the fastest and most cost-effective ways to curb heat-trapping gases.

“We have for the first time been able to attribute emissions in Bangladesh to a specific source,” Germain said. “This is a large source but is still not sufficient to explain the large, sustained and diffuse emissions detected over the city. The situation remains a mystery and we will continue to monitor the area.”

The Matuail waste site is one of several sources that are probably producing methane plumes over Bangladesh this year, according to Montreal-based GHGSat. The 12 highest methane-emission rates detected this year in satellite data occurred over Bangladesh, according to analytics company Kayrros SAS.

Bangladesh’s Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change is aware of the situation and has formed a technical committee to assess the extent of the problem, it said in an emailed response to Bloomberg questions.

“The committee is assigned to assess methane emission from Matuail sanitary landfill site” and also to suggest mitigation measures, the ministry said. Its report is due in a month.

The Matuail landfill spreads over 181 acres and accepts about 2,500 tons of waste a day, according to Sufiullah Siddik Bhuiyan, executive engineer of the Waste Management Department of Dhaka South City Corp.

While the site has received funding from the Japan International Cooperation Agency to help manage liquid waste and greenhouse gases, the landfill doesn’t have data on how much methane gas it generates, Bhuiyan said.

Scientists are just beginning to pinpoint the biggest sources of methane globally. Domesticated livestock, rice cultivation, leaks from the oil and gas industry and landfills are just some of the sources of the emissions, according to the Global Methane Initiative.

Measures included in a 2018 short-lived climate pollutants-reduction plan would cut Bangladesh’s methane emissions up to 17-24% by 2030 and up to 25-36% by 2040, according to the statement from the environment ministry. Bangladesh has also worked with Danish assistance to reduce leaks from gas-pipeline distribution networks, it said.

Observations of methane from space can be seasonal due to cloud cover, precipitation and varying light intensity, according to Kayrros, which analyzes data from European Space Agency satellites. Offshore emissions and releases in higher latitudes such as the Arctic, where Russia has extensive oil and gas operations, can also be hard to track from space.

Bangladesh, which chairs the Climate Vulnerable Forum, whose 48 members represent 1.2 billion people most threatened by climate change, is vulnerable to extreme weather events and rising oceans due to its low elevation and high population density.

Updated: 4-28-2021

Senate Votes To Reverse Trump-Era Loosening of Methane Emission Rules

Lawmakers backed restoring regulations for emissions that leak into the air from oil and gas production.

The Senate voted to restore regulations on methane gas that leaks into the air from U.S. oil and gas production, reversing a Trump-era policy and giving a boost to the Biden administration’s goal of reducing emissions.

In a 52-42 vote Wednesday, the Senate invoked its power under the Congressional Review Act to overturn rules adopted by the Environmental Protection Agency last year on methane-gas emissions, including those easing some monitoring requirements and lowering standards for pollution-control systems to detect methane leaks by facilities that transmit and store natural gas.

Three Republican senators—Susan Collins of Maine, Lindsey Graham of South Carolina and Rob Portman of Ohio—voted with Democrats in favor of the legislation.

Methane is a component of natural gas, which has grown in popularity as a fuel. It is transported via pipelines, which can leak the gas. Scientists have determined that methane, while emitted in smaller amounts into the atmosphere than carbon dioxide, is more potent in trapping the earth’s heat.

The oil-and-gas lobby initially fought methane regulations but has recently eased up on that effort. Top producers— Royal Dutch Shell PLC, Exxon Mobil Corp. , BP PLC—have said they support methane regulations as they face pressure from investors on climate issues.

The American Petroleum Institute, the oil industry’s top lobbying group and a powerful Washington voice, announced on the first full day of the Biden administration that it supported direct regulation of methane.

Even so, the regulations are likely to frustrate smaller energy companies who have said they have a harder time paying for the cost to comply with tougher monitoring and detection requirements, said Anne Austin, a former EPA official in the Trump administration who is now an energy attorney in private practice.

“Substantial methane regulation is going to be hard-hitting to [smaller energy companies] especially,” Ms. Austin said.

At a congressional committee hearing before the Senate vote, U.S. EPA administrator Michael Regan said his office has been focused on figuring out how to cut methane emissions to meet Mr. Biden’s goal of cutting emissions of planet-warming gases in half by 2030.

At a news conference held before the vote, Sen. Chuck Schumer (D., N.Y.) called the move the first “of many important steps to achieve the ambitious goal that Joe Biden has set.”

Other lawmakers characterized the regulation as a quick and easy way to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions when big questions still loom over how exactly Mr. Biden’s targets will be met.

“This is not something where we need some fancy technology from 20 years from now,” said Sen. Martin Heinrich (D., N.M.) at a news conference held before the vote. “The solution is here now. We know how to plug these leaks.”

The Congressional Review Act invoked by the Senate on Wednesday was used by Republicans during the Trump administration to unwind more than a dozen Obama administration policies. The 1996 law allows Congress to eliminate regulations that have been enacted within 60 legislative days of their completion.

The law’s power lies in its speed, said Richard Revesz, director of New York University School of Law’s Institute for Policy Integrity, who said that restoring methane regulations through the usual rule-making process could take two years and remain suspended for another year if challenged in court.

“You can imagine the whole process of getting this done through the comment-and-rule process could take the majority of Biden’s first term,” Mr. Revesz. “To get it done through the [Congressional Review Act], it can be done this week.”

The Democratic-controlled House hasn’t yet voted to restore the earlier methane regulations, which were introduced by President Barack Obama in 2016. That vote would end the regulatory pause on methane emissions and reinstate controls on transmission of storage segments of the oil-and-gas industry after less than a year.

Updated: 5-20-2021

Large Methane Cloud Detected Over Prolific Canadian Gas Basin

Satellite data is being mined to hunt down hidden sources of pollution. Spotting methane plumes, a potent greenhouse gas, is at the top of the list for many countries.

A cloud of methane was detected by satellite over a natural gas field in Canada, identifying a hidden source of pollution from one of North America’s most prolific production basins.

The emissions rate was estimated at 79 metric tons an hour on April 20, according to geospatial analytics company Kayrros SAS, which found the plume by analyzing European Space Agency data.

If the release lasted an hour it would trap roughly the same amount of heat as more than 300,000 cars driving at 60 miles an hour, according to the Environmental Defense Fund. The satellite data didn’t show the duration of the leak.

It’s the most severe methane cloud detected in Canada via the satellite data dating back to 2019, and the third-highest rate of emissions identified in North America this year, according to Kayrros.

It said the gas was spotted at the south end of the Duvernay shale play, which is part of the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin. Public and private satellite data has also helped spot methane plumes in countries such as Bangladesh and Turkmenistan.

Halting methane emissions from oil and gas fields has jumped to the top of climate to-do lists globally as nations and companies prioritize the most cost-effective ways to cut emissions.

Methane is about 84 times more dangerous to the environment than carbon dioxide in the first 20 years in the atmosphere. It’s also the primary component of natural gas, which means preventing leaks gives companies more fuel to sell.

The gas sometimes leaks accidentally from poorly maintained pipelines, but can also be released on purpose to maintain safety and during testing. Some U.S. drillers intentionally vent methane during oil production if they don’t have the resources to bring the gas to market.

The Canada Energy Regulator said companies it regulates don’t have to inform it when they intentionally flare or vent gas because those releases are part of regular operations and maintenance activity. Accidental releases must be disclosed, but the agency said none were reported between April 15 and April 20 within a 50-kilometer radius of the plume.

Facilities that meet the requirements of Environment and Climate Change Canada’s Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program must report annual emissions from all on-site activities that released methane, the ECCC said in an e-mail.

Nova Gas Transmission Ltd., a unit of TC Energy Corp., did notify the Alberta Energy Regulator of five potential dates for planned releases—also known as a blowdowns—in April, May and June, the agency said. TC Energy said it executed a scheduled release on April 20 at its Beiseker compressor station, roughly 33 kilometers south of where Kayrros identified the methane cloud.

In a statement, TC Energy said it reports data on emissions to regulators and in public forums. The company declined to provide an estimate for how much methane may have been released during the blowdown on April 20, though it said it took measures to reduce pollution.

“We cannot confirm if the satellite images you’ve shared are related to this planned event, which was done in accordance within all Canadian regulations,” the company said.

Scientists are just beginning to pinpoint the biggest sources of methane and existing data isn’t yet globally comprehensive. Observations from space can be seasonal due to cloud cover, precipitation and varying light intensity. Satellites can also have difficulty tracking offshore emissions and releases in higher latitudes.

Updated: 5-31-2021

Cargill Backs Cow Masks To Trap Methane Burps

Food giant Cargill will start selling experimental wearable technology for cows as the cattle and dairy industries pivot to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

Tackling methane emissions from livestock is one of the most critical—and most difficult—climate issues for meat and dairy companies that are under increasing pressure to clean up their supply chains. Having access to Cargill’s vast customer network could help Zelp secure demand as it prepares to roll out a product that’s still under development.

“Cargill has an impressive reach across dairy farms in Europe,” said Zelp Chief Executive Officer Francisco Norris. “They are uniquely positioned to distribute our technology to a large number of clients, both farmers and dairy companies, maximizing the roll-out from the very first year we hit the market.”

Some 95% of methane released by cows comes out as burps and through the nose. The gas traps 80 times more heat than carbon dioxide in its first 25 years in the atmosphere. Zelp’s wearables, placed above cows’ mouths, act a bit like the catalytic converter on a car.

A set of fans powered by solar-charged batteries sucks up the burps and traps them in a chamber with a methane-absorbing filter. Once the filter is saturated, a chemical reaction turns the methane into CO₂, which is then released.

Zelp is working on miniaturizing the technology and optimizing the energy inside the device, Norris said. It’s in talks with a number of potential manufacturing partners and aims to be ready for mass production at the end of the year. It aims to produce 50,000 units in the first year and as many as 200,000 units the next. The company is close to completing its next financing round, according to Norris.

Cargill was attracted to the masks because they can be used in combination with other solutions, said Sander van Zijderveld, the company’s ruminant strategic marketing and technology lead for West Europe. Several food suppliers are testing or have begun using feed additives which inhibit microbes in cows’ stomachs to help them produce less methane.

“The nice thing about Zelp is that it could complement a cow that is already receiving feed additives to reduce methane emissions,” he said. “It could still capture the methane that is coming out. We could reduce it even more.”

Cargill expects the wearables to come on sale in the second half of next year after more testing, which will focus on animal behavior and the impact on methane reduction, and could expand the scheme outside Europe if demand is high.

Zelp is yet to prove to independent experts that the technology works. Norris said peer-reviewed studies will take place in the fourth quarter after the product has been fully optimized.

Getting cash-strapped farmers to pay for new technologies has been the key challenge, but that’s changing, said van Zijderveld. He thinks incentives will increase, including more dairy processing companies that are willing to pay a premium for milk produced at farms that meet environmental and animal welfare standards. Farmers could also potentially recoup their costs by selling carbon offsets, which other companies can buy to count against their own pollution.

Cargill, based in Minneapolis, aims to cut emissions from its global supply chains by 30% by 2030. In North America, it targets a 30% greenhouse gas reduction in its regional beef supply chain by the end of the decade.

Updated: 6-3-2021

Permian Study Finds Overproduction Leading To More Methane Leaks

Wells in the energy-rich region release three times as much of the potent greenhouse gas as wells in California, according to NASA-led research.

The energy-rich region of the southwestern U.S. known to geologists and fossil fuel enthusiasts as the Permian Basin has expanded its production more quickly than any other oil and gas region in recent years, reaching 38% of U.S. oil and 17% of gas production in 2020. With this scale has come a gush of greenhouse gas emissions, although just how much has until recently been impossible to say.

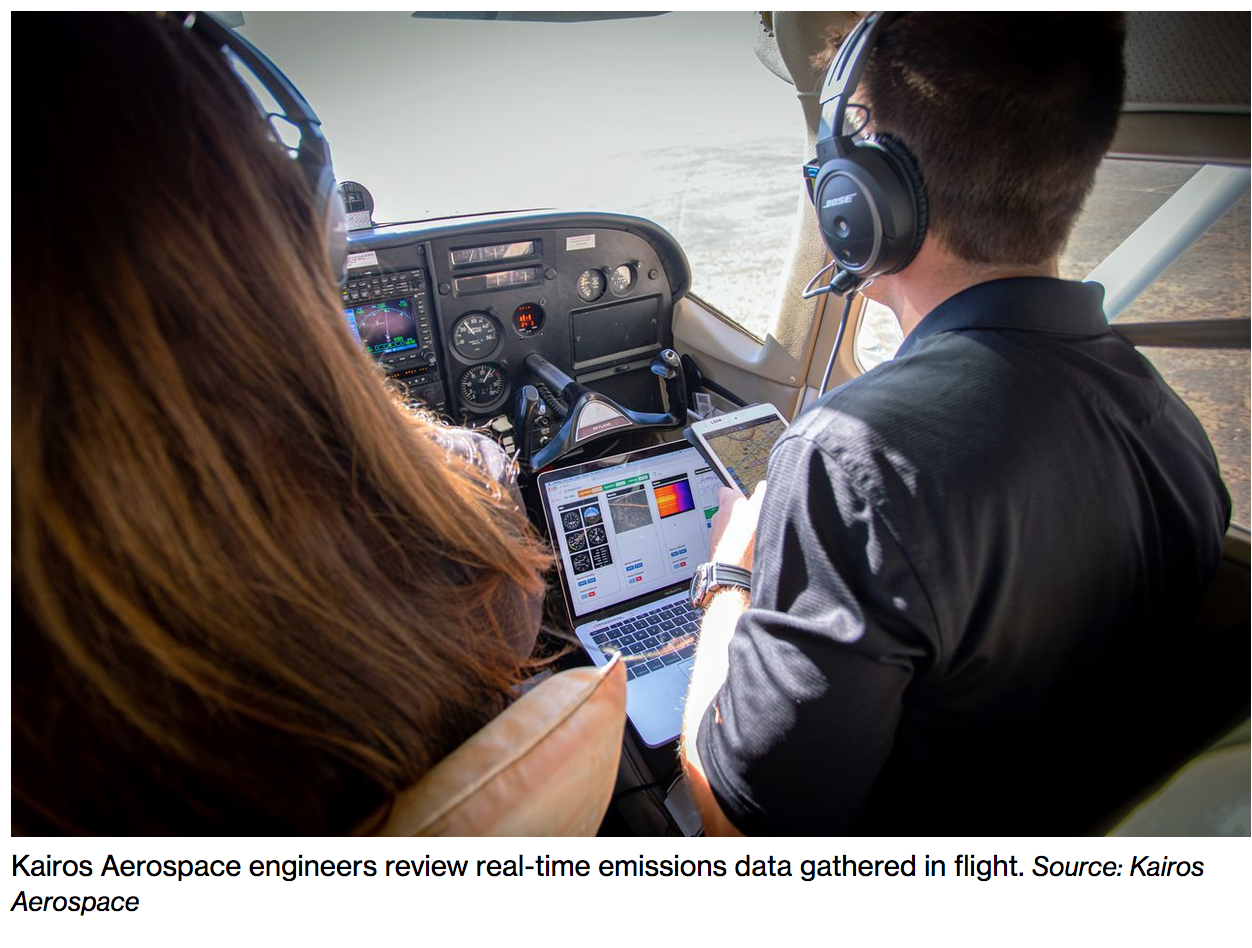

Between September and November 2019, a team of scientists from the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the University of Arizona, and Arizona State University flew multiple times over the 21,000 square miles of the Permian Basin with airplanes bearing sensors that allowed them to pinpoint “super-emitters” of methane.

About 29% of the total lost gas quantified in flyovers between September and November 2019 came from “routinely persistent” sources, indicating that these leaks could be largely eliminated with repairs and diligent monitoring. The releases represented just 11% of emissions sites from a total of 1,100 unique sources studied.

While carbon dioxide is a bigger driver of global warming and lasts longer in the atmosphere, methane—the main component of natural gas—traps more than 80 times as much heat over a 20-year period. Halting methane emissions from the oil and gas industry has jumped to the top of climate to-do lists in part because policy analysts have identified it as one of the cheapest and easiest ways to hold down global temperatures.

Leak detection—which for decades relied on techniques like spraying soap onto pipes or throwing a tarp over equipment to check for fugitive gas flows—is finally entering the digital age, with satellites, drones, and other aircraft promising a new era of climate transparency. By conducting multiple flights at altitudes of 2 miles and 5 miles, NASA scientists were able to document whether the methane emitted from each site was continuous or episodic.

Knowing how long each event went on helped them estimate which part of the oil-and-gas production process the methane escaped from. Half the emissions came from production facilities, including the wells sites themselves and tanks associated with them. Another 38% came from pipelines and gas compression infrastructure, and 12% from processing plants.

The 1,100 sites where the scientists detected emissions make up about 1.4% of the area’s production facilities. By contrast, only about 0.2% of facilities in California were found to be the source of methane plumes. Emissions persist for about the same amount of time in each area, the authors write, but they found more of them in the Permian basin, emitting three times more methane than those in California.

Midstream operations in the Permian, according to the new data, make up about 20% more of the basin’s overall methane total than was expected from previous studies. That result is consistent with the researchers’ hypothesis that high production rates were causing bottlenecks farther down the supply chain, leading to more venting and incomplete flaring.

Flaring—the practice of burning off gas so that it enters the atmosphere as CO₂ not CH₄—can occur at several points in production and may not reduce emissions from the Permian as much as previously thought. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates that flaring typically cuts methane by 98%, a number that’s not supported by this study, nor by studies of other regions.

The nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund has incorporated the NASA and University of Arizona data into its Permian Methane Analysis Project, tagging each oil-and-gas site by company.

Meanwhile Ceres, a nonprofit that promotes capital markets as critical to cleaning up energy, and Clean Air Task Force, a policy research nonprofit, also this week published a report and data explorer documenting and comparing the emissions of nearly 300 of the top U.S. oil-and-gas producers who report data to the Environmental Protection Agency.

They found that small companies who make up 9% of production are responsible for 22% of the sector’s emissions. At the other end of the scale, the biggest seven producers make up a quarter of all emissions.

The airplane survey research was funded by NASA, the University of Arizona, the High Tide Foundation, and Carbon Mapper Inc., a nonprofit that has received funding from Bloomberg Philanthropies, the charitable organization founded by Michael Bloomberg, founder and majority owner of Bloomberg News parent company Bloomberg LP.

Updated: 6-18-2021

Huge Methane Leak Spotted By Satellite Came From Gazprom Pipeline

The Russian energy giant was also responsible for four other recent releases of the superpotent greenhouse gas.

A massive methane plume detected earlier this month over Russia stemmed from emergency repairs that forced the partial shutdown of a Gazprom PJSC pipeline, the company said, taking responsibility for one of the energy sector’s most intense recent leaks of the superpotent greenhouse gas.

Gazprom’s enormous methane leak, first identified in satellite data by geoanalytics firm Kayrros SAS, points to what’s a worldwide problem preventing the release of a greenhouse gas with 80 times the impact of carbon dioxide in the short term.

The Russian gas giant said its pipeline repairs on June 4 released 2.7 million cubic meters (1,830 metric tons) of methane. That has roughly the same short term planet-warming impact of 40,000 internal-combustion cars in the U.S. driving for a year, according to the Environmental Defense Fund.

Kayrros estimated an emissions rate of 395 metric tons an hour, which would make Gazprom responsible for the most severe release it has attributed to the oil and gas sector since September 2019.

Gazprom said the gas was released after it detected a problem with its Urengoy-Center 1 pipeline in Russia’s Tatarstan region. The company said that “given the urgency” it wasn’t able to use a mobile compressor station to reduce the methane released by the repairs, though it claimed to still have cut 22% of potential emissions.

The June plume was equal to just 0.1% of the company’s total pollution in 2019, according to analysts at Moscow-based VTB Capital. “The situation might be quite negative for sentiment on Gazprom’s shares,” they said in a note on Friday, even though the leak was unlikely to impact its finances or operations.

Russia’s largest gas company is under pressure to do more to lower the methane emissions caused by its operations as countries in Europe — its biggest market — more closely scrutinize the climate impact of the fuel used to heat their homes and power their grids. The large amounts of methane caused by Russian gas come as the European Union seeks to meet a target of net-zero emissions by mid-century.

The leak this month from Gazprom’s pipeline in Tatarstan isn’t the only major methane release traced to the Russian company. Kayrros detected another giant methane plume on May 24 with an estimated emissions rate of 214 metric tons an hour.

Gazprom said this leak resulted from two days of planned maintenance on the Urengoy-Petrovsk pipeline in Russia’s Bashkortostan region. The emissions amounted to about 900,000 cubic meters, it said, which the company described as “in line with the industrial safety regulations.”

Until the June 4 release, that earlier May 24 leak had ranked as the most severe this year detected by Kayrros in public satellite data and that it attributed to the oil and gas sector.

Gazprom also confirmed it was responsible for three more methane releases that have been spotted in Russia this month. The company said that in all cases it sought to use some of the gas, emissions didn’t exceed government-regulated standards and the events would be included in its environmental reports.

Multiple studies have found methane emissions from the oil and gas industry are often higher than what operators and governments report. Releases of the odorless, colorless gas from the U.S. oil and gas supply chain in 2015 were about 60% higher than U.S. Environmental Protection Agency inventory estimate, a 2018 study published in Science found.

Kayrros is one of several companies that monitor satellite data for methane clouds. The ESA data it uses are obtained by the agency’s Sentinel-5 Precursor satellite, which orbits the globe about 14 times a day to produce a rough snapshot of the world’s methane hot spots. Since wind and other atmospheric conditions can affect plumes, Kayrros uses atmospheric dispersion modeling to estimate the emissions rate and each plume’s source location.

Scientists are just beginning to pinpoint the biggest sources of methane and existing data isn’t yet globally comprehensive. Public and private satellite data have helped spot methane plumes in countries including Canada, Bangladesh and Turkmenistan.

Still, observations from space can be seasonal due to cloud cover, precipitation and varying light intensity. Satellites can also have difficulty tracking offshore emissions and releases in higher latitudes.

Russian President Vladimir Putin cited methane’s contribution to global warming in an April speech and said it’s “extremely important to develop broad and effective international cooperation in the calculation and monitoring of all polluting emissions into the atmosphere.”

Asked about the May 24 incident, the regional ministry of environmental management and ecology said it didn’t register any man-made damage in the area during that period.

Updated: 7-4-2021

Huge Methane Leak Spotted In Heart Of China’s Top Coal Hub

The plume is one of the largest so far attributed to global coal industry. Leaks detected by satellite have also been spotted in Canada, Russia and South Africa.

A massive plume of methane, the potent greenhouse gas that’s a key contributor to global warming, has been identified in China’s biggest coal production region.

The release in northeast Shanxi province is one of the largest that geoanalytics company Kayrros SAS has so far attributed to the global coal sector and likely emanated from multiple mining operations.

Details captured in European Space Agency satellite data show the plume about 90 kilometers (56 miles) east of Shanxi’s capital Taiyuan, in Yangquan City. The area has 34 coals mines, according to the Shanxi Energy Bureau.

Shanxi’s Department of Ecology and Environmental, the province’s Energy Bureau and China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment didn’t respond to requests for comment. The National Development and Reform Commission didn’t respond to a fax.

The emissions rate needed to produce the plume observed in the June 18 satellite image would be several hundred metric tons an hour, according to Kayrros. For comparison, a 200-ton per hour release would have roughly an equivalent climate warming in the first two decades as 800,000 cars driving at 60 miles an hour, according to the Environmental Defense Fund.

China is both the world’s largest producer and consumer of coal. The industry presents the nation’s biggest opportunity to mitigate methane emissions, according to a United Nations assessment. In March, China’s latest five-year plan included, for the first time, a pledge to contain the gas that traps roughly 80 times more heat than carbon dioxide in the initial 20 years after it is released.

President Xi Jinping has outlined an ambition for the country to start reducing coal use from 2026 on its way to a broader goal to peak greenhouse gas emissions by the end of the decade and reach carbon neutrality by 2060.

China’s foreign ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin told reporters during a regular press briefing on Monday he wasn’t aware of the release and said the country is committed to low-carbon development.

Efforts to curtail coal use to have largely focused on the large amount of CO₂ generated when it’s burned. But mining the fuel is also problematic, because producers frequently release methane trapped in underground operations to lower the risk of explosion.

“Many existing coal mines are under poor management” in China, said Li Shuo, a climate analyst at Greenpeace East Asia. “There is much catching up to do to better monitor the sources and scale of methane emissions.”

Methane can continue leaking long after mines have been closed or abandoned, and the industry is expected to account for about 10% of man-made emissions of the gas by the end of the decade, according to the Global Methane Initiative.

To achieve its 2060 carbon neutral goals, China should create an investment and financing system that tackles methane reductions, the Environmental Defense Fund said in a report. It can also make sense for miners themselves to take extra steps to capture methane emissions, as the gas can be used for power generation, coal drying or as supplemental fuel, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The analysis of the Shanxi plume follows earlier work to identify methane releases in countries including Russia and South Africa, as scientists begin to pinpoint the biggest sources of the emissions. Existing data isn’t yet globally comprehensive, and satellite observations can be impacted by cloud cover, precipitation and varying light intensity. Satellites can also have difficulty tracking offshore emissions and releases in higher latitudes.

Updated: 7-22-2021

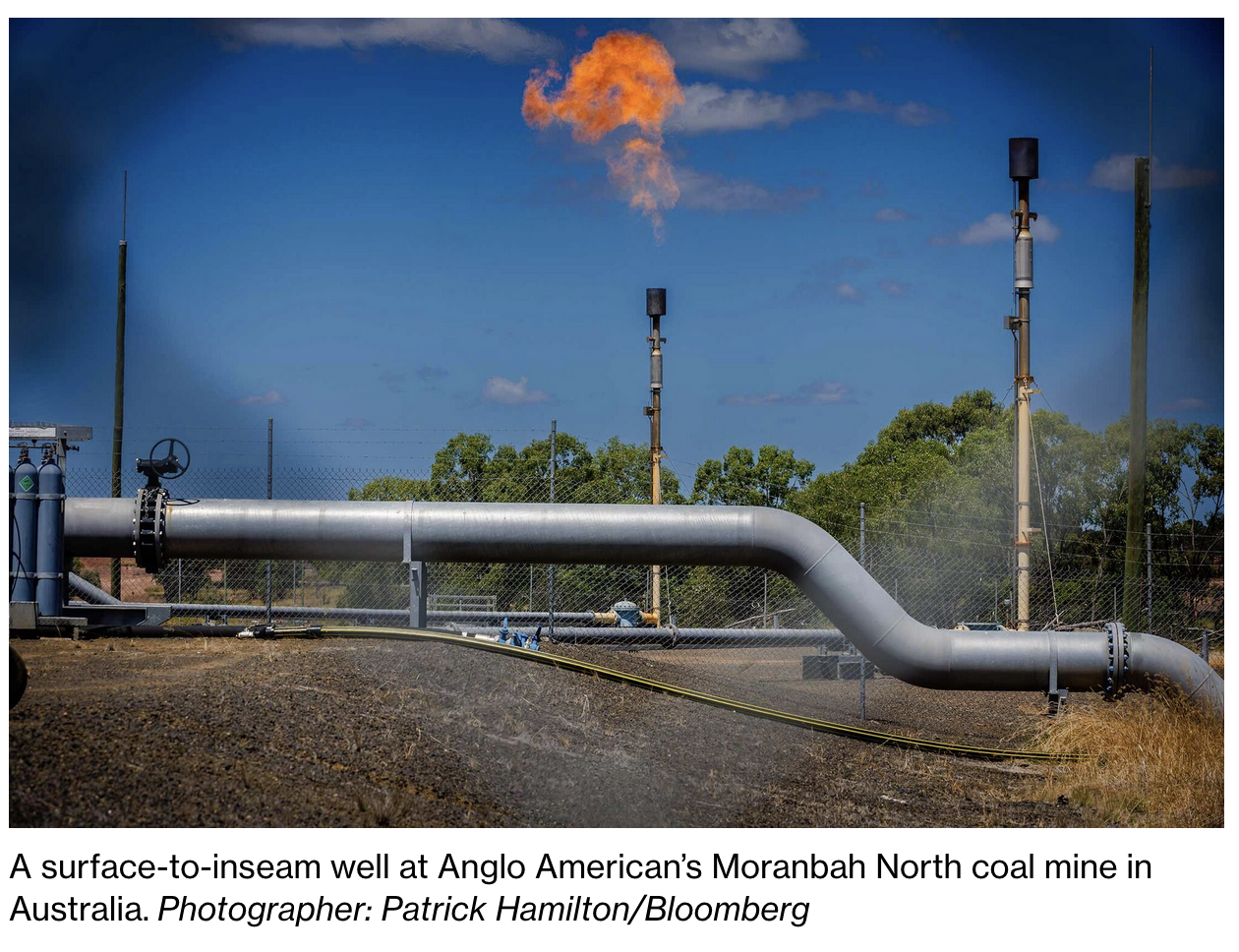

Plumes of Potent Methane Gas Spotted Near Australia Coal Mines

The country is one of the world’s biggest exporters of the dirtiest fossil fuel.

Potent methane plumes have been detected in a key coal mining district in Australia, one of the world’s biggest exporters of the commodity, underscoring the fossil fuel’s role in exacerbating climate change.

Clouds of the invisible greenhouse gas, which is over 80 times more powerful than carbon dioxide at warming the Earth in its first couple decades in the atmosphere, were spotted near multiple mines last month, an analysis of European Space Agency satellite data by geoanalytics firm Kayrros SAS showed.

Two large clouds of methane were spotted over the Bowen Basin on June 21, and were visible across more than 30 kilometers each. While Kayrros attributes the clouds to the coal sector, the plumes were diffused and could have come from multiple sources.

The leaking of methane into the atmosphere has come under increasing scrutiny as awareness grows over their harmful global warming effects. Scientists view reducing emissions from the fossil fuel industry as one of the cheapest and easiest ways to hold down temperatures in the near term, especially as improving technology makes it easier to identify polluters.

Efforts to curtail coal use have largely focused on the large amount of CO₂ generated when it’s burned, but mining the fuel is also problematic because producers can release methane trapped in underground operations to lower the risk of explosion.

The coal sector is forecast to account for about 10% of man-made emissions of the gas by the end of the decade, according to the Global Methane Initiative.

The Bowen Basin is a key producing region for Australia, the world’s top exporter of metallurgical coal used in steel-making. For every ton of coal produced in the region, an average 7.5 kilograms of methane is released, according to Kayrros. That’s 47% higher than the global average in 2018, the geoanalytics company said, citing International Energy Agency data.

When contacted about the larger of the two plumes, Queensland’s Department of Environment and Science said it didn’t receive notice of methane releases in the two days through June 21.

Coal mining companies have reporting obligations under the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Scheme that is regulated by the federal government, the department said.

Updated: 8-3-2021

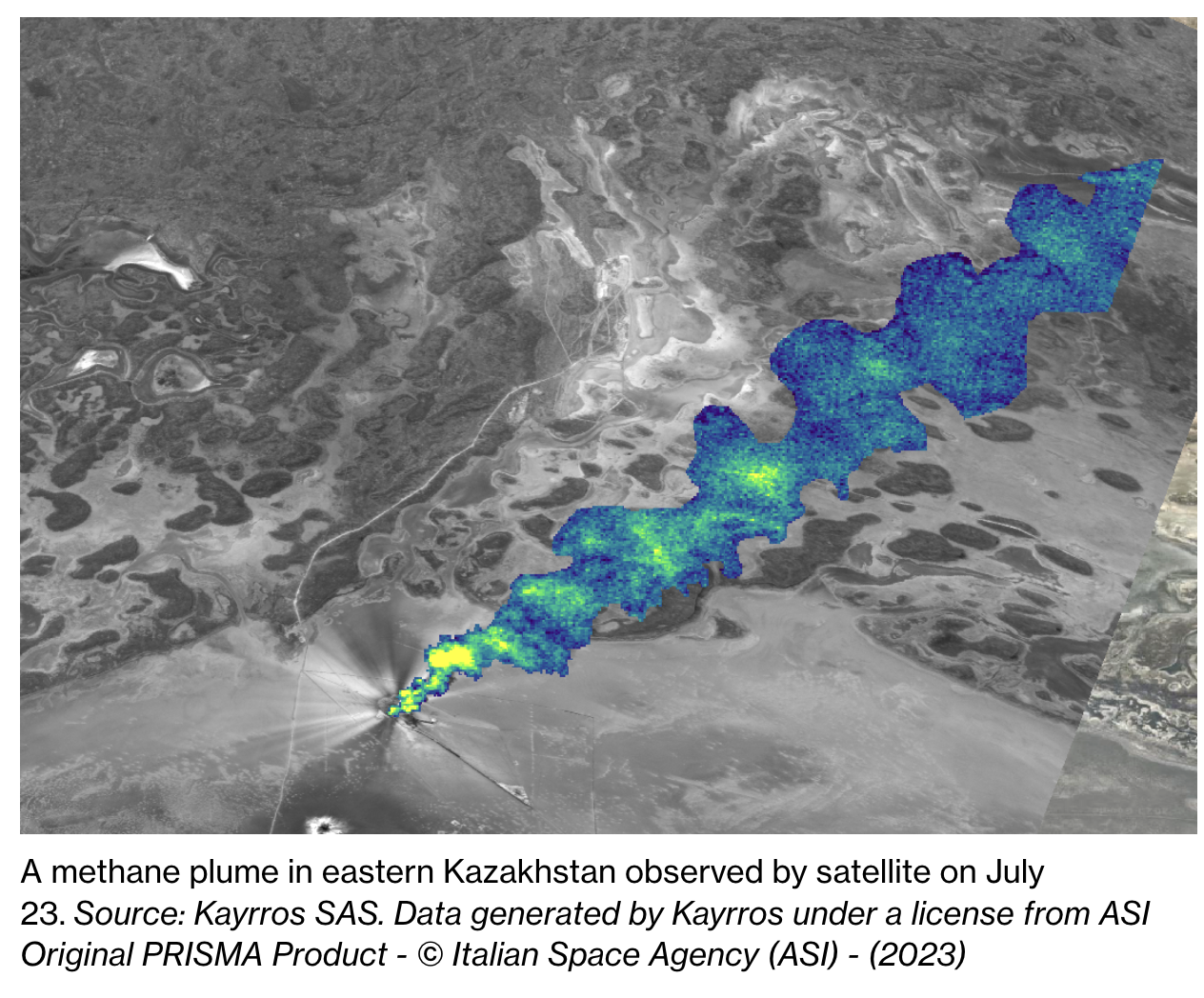

Huge Methane Cloud Spotted Near Gas Pipeline That Supplies China

The emissions match the planet-warming impact of 10,000 cars driving in the U.K. for a year.

A massive methane plume detected last month over Kazakhstan occurred near a major pipeline that supplies natural gas to China.

The cloud was observed roughly 100 kilometers (62 miles) west of the largest Kazakh city of Almaty on July 24, and had an emissions rate of more than 200 tons of methane an hour, according to an estimate from geoanalytics firm Kayrros SAS. That amount of the super-warming greenhouse gas would have roughly the same short-term climate warming impact as the annual emissions of 10,000 cars in the UK.

“This large emission event matches the pattern of methane release observed from gas infrastructure,” said a spokesperson for Kayrros. “A pipeline and compressors are in close proximity, and based on information Kayrros has access to there are no other candidates for the observed release.”

KazTransGas JSC, which operates the Kazakh portion of the Central Asia-China pipeline, said it didn’t have any leaks and the country’s energy ministry didn’t immediately provide a response to queries about the plume. The 1,833-kilometer pipeline helps transport gas mostly from Turkmenistan through Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan to China.

Satellite detection of methane plumes from natural gas have revealed a greater climate impact from the fossil fuel long promoted by producers as a bridge to renewables as the world decarbonizes. Beijing plans to boost imports of gas from Turkmenistan, the South China Morning Post reported in May.

Methane is the largest component of natural gas, and it is the second-largest contributor to warming the planet after carbon dioxide. Levels of the greenhouse gas in the atmosphere are rising fast, partly because of increase in oil and gas activity globally. A steep reduction in methane emissions is considered one of the cheapest and easiest ways to slow the increase in global temperatures.

Kayrros couldn’t say how long the release lasted because the analysis was based off a single satellite observation captured by the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-5P satellite as it passed over Kazakhstan that day in July.

Multiple studies show that methane emissions from oil and gas infrastructure are often higher than what operators and governments report. Public and private satellite data are helping spot methane plumes in countries including Russia, Canada and Australia.

Updated: 8-12-2021

Frackers, Shippers Eye Natural-Gas Leaks As Climate Change Concerns Mount

Cheniere Energy, EQT among those dispatching drones, planes and specialized cameras to collect data amid international pressure from buyers.

Drones darted in patterns above natural-gas wells in the hills of southwest Pennsylvania, as workers atop water tanks pointed specialized cameras, and a helicopter outfitted with a laser-light detection system swooped in low. All searched for an invisible enemy: methane.

The American gas industry faces growing pressure from investors and customers to prove that its fuel has a lower-carbon provenance to sell it around the world. That has led the top U.S. gas producer, EQT Corp., and the top exporter, Cheniere Energy Inc., to team up and track the emissions from wells that feed major shipping terminals.

The companies are trying to collect reliable data on releases of methane—a potent greenhouse gas increasingly attracting scrutiny for its contributions to climate change—and demonstrate they can reduce these emissions over time.

“What we’re trying to really do is build the trust up to the end user that our measurements are correct,” said David Khani, EQT’s chief financial officer. “Let’s put our money where our mouth is.”

Natural gas has boomed world-wide over the past few decades as countries moved to supplant dirtier fossil fuels such as coal and oil. It has long been touted as a bridge to a lower-carbon future. But while gas burns cleaner than coal, gas operations leak methane, which has a more potent effect on atmospheric warming than carbon dioxide, though it makes up a smaller percentage of total greenhouse gas emissions.

Investors, policy makers and buyers of liquefied natural gas, known as LNG, are rethinking the fuel’s role in their energy mix because of concerns about methane emissions, which were highlighted this week as a significant contributor to climate change by a scientific panel working under the auspices of the United Nations.

Those concerns, pronounced in Europe and increasingly in Asia, are a problem for LNG shippers, as some of their customers signal plans to ease gas consumption over time. In a policy draft last month, Japanese regulators said the country would have LNG make up 20% of its projected power generation by 2030, down from a prior target of 27%.

The European Union has been weighing how to pressure LNG shippers to cut emissions. It could, for example, include LNG among the imports subject to a recently proposed carbon border tax.

Nearly every industry now faces some pressure to reduce its carbon footprint, as investors focus more on ESG—or environmental, social and governance—issues and push companies for trustworthy emissions data.

But the pressure has become particularly acute for oil-and-gas companies, whose main products contribute directly to climate change.

Producing, transporting and ultimately burning one metric ton of LNG releases the greenhouse gas equivalent of about 3.4 metric tons of carbon dioxide, according to a U.K. government estimate, about a quarter of which are emitted before the fuel reaches a power plant.

Though the world is now devouring natural gas as economies emerge from the coronavirus pandemic, shale executives said keeping U.S. supplies competitive longer-term will require companies to corral leaks from wells, processing facilities, pipelines and the export plants before tankers carry it around the world. The tricky part, they said, is proving to skeptics they are actually doing so.

Cheniere, the largest U.S. LNG exporter, this summer began leading a joint effort with EQT, the largest gas producer, and four other domestic producers including Pioneer Natural Resources Co. , to figure out the most effective way to monitor and quantify methane emissions.

Over six months, the companies and researchers plan to test drones, specialized cameras that can see methane gas, and other technologies across about 100 wells in the Marcellus Shale in the northeast U.S., the Haynesville Shale of East Texas and Louisiana, and the Permian Basin of West Texas and New Mexico.

The goal is to collect methane emissions data and see how it stacks up against current estimates from U.S. environmental regulators, which critics consider overly conservative as their underlying data isn’t based on continuous measurements. The companies will then decide which technology is the most effective when deployed on a larger scale for continuous monitoring of methane leaks, and which ways to best cut emissions.

EQT has said it would spend $20 million over the next few years to replace leaky pneumatic devices, which help move fluids from wells to production facilities and water tanks, with electric-drive valves, executives said. They expect that will cut about 80% of the company’s methane emissions. The company also began exclusively using electric-powered hydraulic fracturing equipment last year.

Cheniere delivered what it called its first carbon-neutral cargo to Royal Dutch Shell PLC in Europe in April, by purchasing carbon offsets from Shell. It also plans to provide customers next year with data on emissions tied to each shipment it sends from its two Gulf Coast export facilities. That data, contained in Cheniere’s so-called cargo emissions tags, will be based on its analysis of emissions from its supply chain.

The LNG shipper expects its analysis will show a range of emissions from gas producers, pipelines and exporters, but that emissions from the gas it gathers will be comparatively low, said Anatol Feygin, Cheniere’s chief commercial officer.

Mr. Feygin said the U.S. gas industry hasn’t “done a good job of getting the transparent, auditable information” it needs to back up its claim that it has been curbing emissions, and that collecting that data will be critical for the industry’s social license to operate going forward. Cheniere hasn’t yet announced any partnerships with pipeline companies that transport gas, another area where it said its efforts will need more work.

“It’s going to take a very long time to migrate the entire supply chain,” Mr. Feygin said, describing the ultimate goal as “high-quality, real-time information.”

Updated: 8-16-2021

Large Methane Cloud In Iraq Coincided With Gas Pipeline Leak

The country is a top oil producer and was one of the biggest emitters of methane last year, according to the IEA.

A pipeline run by Oil Pipelines Co. in Iraq leaked liquefied petroleum gas on July 20, close to where a large plume of the super-potent greenhouse gas methane was detected.

The accident lasted less than a few hours and didn’t release any methane, according to an official with the state-run company who confirmed the leak. Liquefied petroleum gas is largely made up of propane and butane, but often also contains small amounts of methane and ethane. It is shipped as a liquid in pipelines and turns into gas at normal atmospheric temperature and pressure.

The cloud of methane was detected by Kayrros SAS, a Paris-based geoanalytics firm that parses European Space Agency satellite data to track down emissions. It occurred roughly 140 kilometers (87 miles) west of Basrah. Kayrros estimated the release happened at a rate of 73 tons of methane an hour; it can’t determine the duration of a release based on a single satellite observation.

Iraq is one of the world’s top oil producers and was the fifth-biggest emitter of methane last year among a selected group of its peers, according to the International Energy Agency.

The greenhouse gas is more than 80 times more powerful than carbon dioxide at warming the Earth in its first couple decades if released directly into the atmosphere. Stopping leaks is one of the most significant things that can be done right now to slow global warming that’s already reached dangerous levels.

Oil Pipelines Co.’s protocol when a leak occurs is to shut the pipeline down and immediately fix it, the official said. The July plume followed two other methane observations in Iraq on June 23 and June 24, located about halfway between Basrah and Baghdad, with estimated emissions rates of 181 and 197 tons of methane an hour, respectively.

That two plumes were found at the same spot over consecutive days suggests they were part of a single event that lasted 24 hours or longer, according to Kayrros.

If the release lasted 24 hours at 180 tons of methane an hour, it would have the same planet-warming impact as the average annual emissions of more than 200,000 cars in the U.K. Other than Oil Pipelines Co., Thiqar Oil Co. is the only other major company that owns Iraq’s fossil-fuel infrastructure in that area.

It said the releases weren’t from its operations. An official for Iraq’s oil ministry said releases can occur from pipelines because of corrosion, as well as illegal tapping by unauthorized parties.

Satellite detection of methane plumes from natural gas supply chains has revealed a greater climate impact than previously thought from the fossil fuel long promoted by producers as a bridge to renewables. A steep reduction in methane emissions is considered one of the cheapest and easiest ways to slow the increase in global temperatures, according the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report published earlier this month.

Multiple studies show that methane emissions from oil and gas infrastructure are often higher than what operators and governments report. Previous Bloomberg Green reporting on methane plumes based on Kayrros data has led to public acknowledgement of releases from Kazakhstan and Russia. Public and private satellite data are helping spot methane plumes in countries including Canada and Australia.

Updated: 8-20-2021

The Methane Hunters

Frackers in America’s largest oil field are letting massive amounts of natural gas spill into the atmosphere. Scientists and activists are trying to find the leaks and get them plugged before they cook the planet further.

Five hundred miles above the Earth’s surface, the Copernicus Sentinel-5 Precursor, a satellite about the size of a pickup truck, has been circling the planet for four years, taking pictures of the atmosphere below. The satellite’s infrared sensor can see things humans can’t, and in 2019, Yuzhong Zhang, a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard, got a look at some of its first readings.

Zhang was interested in methane, an invisible, odorless gas. Although carbon dioxide from burning fossil fuels is the principal cause of global warming, methane has many times carbon’s warming power and is thought to be responsible for about a quarter of the increase in global temperatures caused by humans.

When Zhang laid the satellite readings over a map of the U.S., the biggest concentration of the gas showed up as a red splotch over a 150-mile-wide swath of Texas and New Mexico.

The postdoc loaded the readings into a supercomputer to calculate what it would take to form that pattern.

A few days later he had an answer. Beneath the splotch, Zhang discovered, 2.9 million metric tons of methane were pouring into the sky each year. By one measure, that cloud of gas is contributing as much to global warming as Florida—every power plant, motorboat, and minivan in the state.

Zhang, now at Westlake University in Hangzhou, China, calls it the “Permian methane anomaly.” The anomaly lies directly atop the Permian Basin, one of the most bountiful oil-producing regions in the world. Wells there churn out less-profitable natural gas alongside petroleum, and natural gas is mostly methane.

Zhang’s research demonstrated that a surprising amount of that gas, more than twice what the U.S. government has estimated, is just spilling into the air unburned. Imagine that someone turned all the knobs on a stove without lighting a flame. Now imagine 400,000 stoves scattered across the Southwest, hissing day and night, cooking nothing but the planet itself.

Identifying and plugging these leaks could do more to slow climate change than almost any other single measure. Unlike carbon, methane breaks down relatively quickly in the atmosphere. That means efforts to curtail it can pay off within a generation.

According to one recent estimate, almost one-third of the warming expected in the next few decades could be avoided by reducing human-caused methane emissions, without having to invent new technology or cut consumption.

Some of that would come from cleaning up other sources, such as landfills and cattle feedlots. (Cow burps are full of methane.) But oil and gas fields are the most obvious places to start, because they offer the biggest potential reductions at the cheapest cost.

Only in the past few years has the urgency of the methane problem come into focus, partly because of new technology and scientific research that’s uncovering leaks from pipelines in Russia to old wells in West Virginia.

The latest assessment, published on Aug. 9 by United Nations-backed scientists, says “strong, rapid, and sustained reductions” in these emissions are key to meeting climate goals. In the U.S., regulation hasn’t kept up. In many cases, energy producers and pipeline operators are free to spew methane into the air without running afoul of any law.

In lieu of regulation, nonprofit groups and activists are acting as self-appointed private eyes, running their own Permian monitoring programs and pressuring companies directly. Gas markets are responding, too.

Last year a $7 billion contract to send Permian liquefied natural gas to France collapsed over concerns about the greenhouse gas footprint. Lenders and investors are also pushing for action. Now oil companies are launching their own drones, airplanes, and satellites in the service of mostly voluntary efforts to find the spills and stop them.

It’s unclear how far private and voluntary actions will go. One obstacle is the sheer size of the Permian, a sparsely populated scrubland where spills from open hatches, equipment malfunctions, and the like can continue for days before anyone notices. Another is the jumble of companies and wells.

Even the Sentinel-5P’s powerful sensor has trouble identifying individual leaks. Spills are so large and numerous that, seen from space, they merge into one indistinguishable mass.

Up close, the Permian is flat and dry. Cows wander across lonely plains of mesquite, and rusting pump jacks dot the horizon. Wildcatters have been chasing oil here for a century, but nothing in the past compares to the frenzy that gripped the region about six years ago.

Advances in extraction techniques, including horizontal drilling and fracking, had opened up reserves in previously inaccessible shale rock, helping to drive down global energy prices. That set off a hunt for prospects that could be profitable even if oil stayed cheap, and the Permian’s unusual geology stood out.

Meanwhile, Congress ended a longtime ban on oil exports, benefiting basins that produce light sweet crude, which foreign refineries are better-equipped to handle. Money poured in from oil majors and private equity funds. More than half the nation’s drill rigs were mobilized. Drilling rights neared $100,000 an acre, and hotels in Midland, Texas, the commercial hub of the oil patch, started charging Manhattan prices.

The landscape was transformed. Clusters of cylindrical oil tanks appeared everywhere, along with rectangular ponds as big as football fields holding the water needed for fracking. Camps for thousands of itinerant workers were laid out with military precision.

A few days after the ban was lifted, on Christmas Eve 2015, drillers broke ground on a new well whose story is a microcosm of the Permian. State Pacific 55-T2-8X17, as the site is known, sits on a stretch of rangeland near the Pecos River in Texas’ Loving County (population 169). Two months later, it was complete: a wellhead and six storage tanks squatting on a rectangle of bare earth.

The money behind State Pacific came from BHP Group, an Australian mining colossus that spent big to drill faster than rivals. State Pacific alone brought forth 166,000 barrels of oil and other hydrocarbon liquids in its first year, as well as 620 million cubic feet of gas.

As companies such as BHP started chasing Permian crude, there wasn’t much of a plan for the gas that came up with it. Gas is difficult to store, and getting it to market requires a complex system of pipelines, compressors, and cryogenic processing plants. In the most lucrative parts of the field, including Loving County, that infrastructure was inadequate or nonexistent.

With gas fetching so little that the price sometimes went negative, companies could save money by just burning it off rather than waiting for pipelines to be built. Across the region, hundreds of flares began to light up the sky each night. From space, the desert looked as bright as Albuquerque.

Even when producers could hook up to a pipeline, these lines were often congested and prone to interruptions. At BHP wells such as State Pacific, the problems were compounded by frequent breakdowns of the diesel compressors required to push gas into pipelines at about 1,000 pounds per square inch.

The machines tended to fail if the temperature or system pressure rose too high. Since the sites were unmanned, outages would stretch for days. According to readings from a U.S. satellite that can spot individual flares at night, BHP burned gas frequently at State Pacific during its first three years in operation, torching off at least one-fourth of the gas produced.

Theoretically, flaring shouldn’t contribute much to the methane problem, because burning methane converts it to carbon dioxide—still a greenhouse gas, but a far less potent one. Of course, that’s only true if the flare works as intended.

Long before Zhang tallied the scale of the damage in the Permian, Sharon Wilson, an activist from Dallas, was driving across Texas with a $100,000 camera, hunting for leaks. Wilson works for the environmental advocacy group Earthworks, and her hardware makes methane show up inky black in photos.

If a satellite offers a godlike view of the region, Wilson can track individual plumes right to the source. In May, during one of her regular trips to West Texas, she was in the back of a rented GMC Yukon as an Earthworks colleague steered down a highway past freshly plowed cotton fields. In her lap, the camera, a FLIR GF320, was whirring softly, the sound of a cooling mechanism that keeps its guts colder than dry ice.

“Your faucet drips, that’s a leak,” Wilson said, her graying blond hair tucked under a baseball cap. “I hardly ever see a leak out here. I see a garden hose. A fire hose. A volcano.”

After each trip, Wilson uploads the most dramatic pictures to YouTube and emails them to state regulators—methane clouds pouring from broken valves, malfunctioning engines, and open hatches—hoping to pressure companies and government officials to clean things up.

Wilson, 68, didn’t think much about the environment when she worked for an oil marketing company. That changed, she says, when she lived in the prairie country north of Fort Worth and saw fracking ruin the place. Now she calls company executives “gasholes” on Twitter and enjoys recounting stories of her run-ins with hostile oilfield workers, whom she always nicknames Jethro.

Some of the most common culprits Wilson has found are flare stacks. These are tall pipes crowned with burners designed to torch off unwanted gas. Wilson says they frequently malfunction—the flames go out, allowing a stream of invisible gas to jet into the air. To the naked eye, it’s impossible to tell anything’s amiss.

David Lyon had seen Wilson’s videos of misbehaving flare stacks, but he wasn’t sure what to make of them. Lyon, an Arkansas native, is the lead scientist for a massive Environmental Defense Fund research project in the Permian charting the pollution in unprecedented detail. Do flares really get snuffed out all that often, he wondered? He dispatched a contractor to fly over hundreds of randomly selected flare stacks in a helicopter to find out.