Resistance To Noncompete Agreements Is A Win For Workers (#GotBitcoin?)

Several states try to limit contracts that make movement between jobs harder. Resistance To Noncompete Agreements Is A Win For Workers (#GotBitcoin?)

Noncompete Provisions Have Increasingly Crept Into Contracts For Lower-Wage Workers Like Hairdressers.

Quitting a job for a better offer is a time-tested method of securing a pay raise, improved working conditions or both.

Now a national backlash is building against employers that make such movement harder with noncompete agreements that bar departing employees from taking jobs with industry competitors for certain periods of time. That’s good news for workers, because eliminating barriers to job-hopping could help stir the kind of wage growth workers haven’t seen since before the last recession.

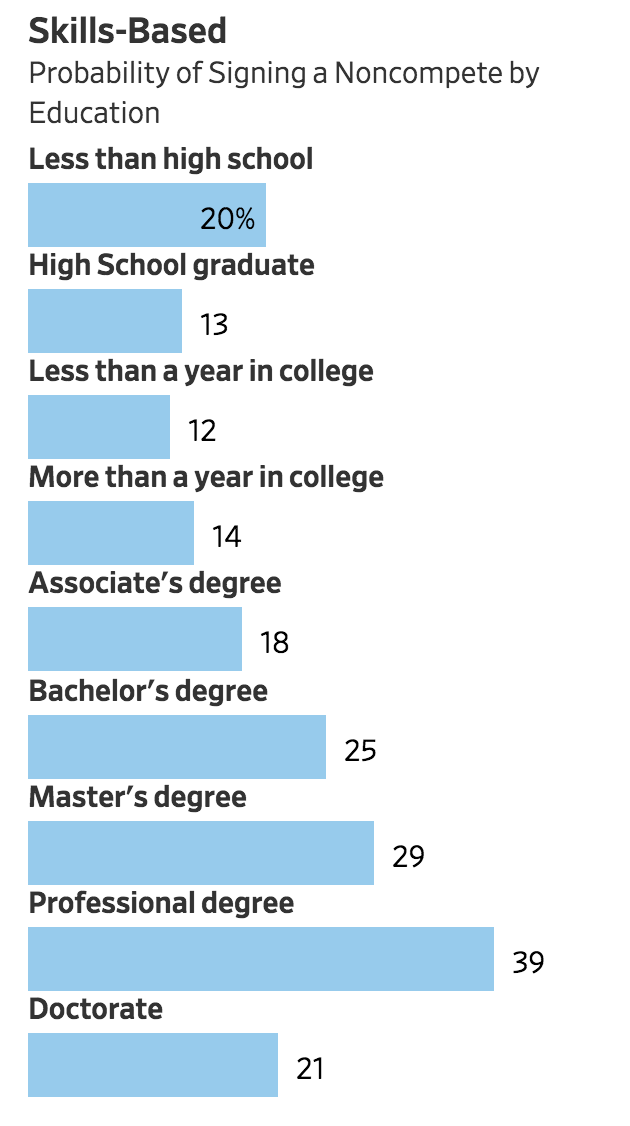

Employers have long used noncompetes to protect company secrets and intellectual property, applying them primarily to high-earning professionals such as business executives, scientists and lawyers. Noncompete provisions have also crept into contracts for lower-wage workers like janitors, hairdressers and dog walkers, with companies saying those workers have access to proprietary information and customer bases.

In Washington, state legislators last month passed a law making noncompetes unenforceable for certain workers, including employees earning less than $100,000 a year. Hawaii in 2015 banned noncompete agreements for technology jobs, arguing they imposed hardship on tech employees and discouraged entrepreneurship. A later study found that the Hawaii ban increased mobility by 11% and wages for new hires by 4%.

Earlier this year, New Hampshire’s Senate passed a bill banning noncompete agreements for low-wage workers, and lawmakers in Pennsylvania and Vermont have proposed to ban noncompetes with few exceptions.

Attorneys general also have successfully challenged some of these agreements. WeWork Cos., for example, last year agreed to sharply curtail its practice of requiring most employees to sign noncompete agreements, as part of a settlement with attorneys general in New York and Illinois.

After the settlement, WeWork released 1,400 rank-and-file employees, including cleaners and baristas, from noncompete agreements nationwide. The terms of another nearly 1,800 employees’ noncompetes were made less restrictive. The shared-office company declined to comment on the percentage of its employees that are still bound by noncompete agreements in the U.S.

New York and Illinois also reached settlements in 2016 with sandwich chain Jimmy John’s to stop it from including noncompete agreements in its hiring packets. The company said in a statement it no longer uses noncompete agreements; nor does it encourage franchises to use them.

Earlier this year, the Illinois attorney general reached a settlement with a unit of payday lender Check Into Cash Inc. for imposing noncompete agreements on low-wage customer-service employees. The company declined to comment.

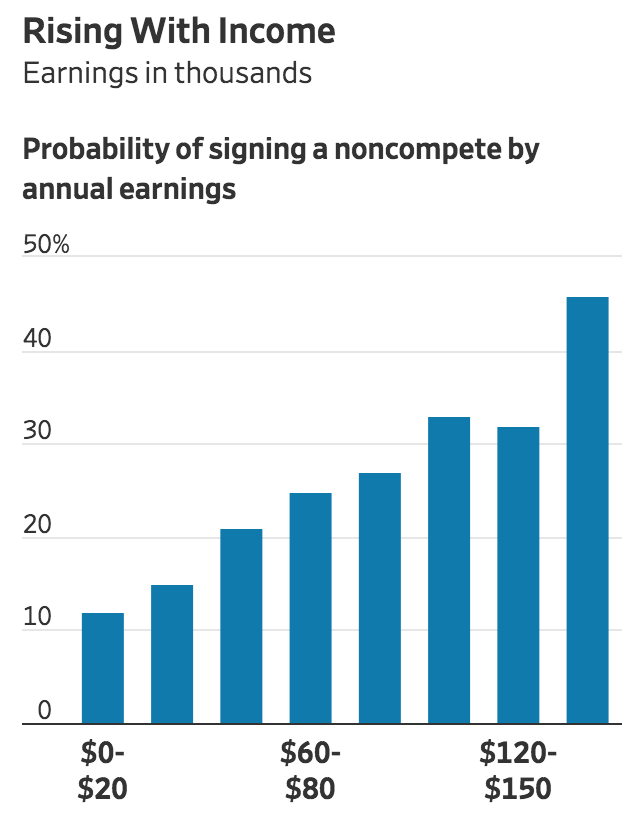

Evan Starr, an economist at the University of Maryland, estimates that roughly 1 in 7 workers making $40,000 or less sign noncompetes. His research found states that enforce the clauses see lower wages over the course of workers’ careers than states that don’t.

“It looks like states that choose to enforce noncompetes see declines in mobility, entrepreneurship and wages,” he told The Wall Street Journal.

Noncompete clauses “severely impact low-wage workers, who are working in those [low-wage] industries because they don’t have alternatives,” said Ronald Gilson, professor of law at Columbia and Stanford universities who has researched the topic. Among such workers, the agreements have “no other purpose than to restrict competition in the market for employees,” he said.

Defenders of noncompete clauses say they safeguard legitimate business interests like protecting proprietary information in an increasingly knowledge-based economy and make companies more inclined to invest in worker training.

In California, North Dakota and Oklahoma, noncompete agreements are generally void under state law. Other states, like Massachusetts, last year tightened the conditions under which the covenants can be enforced. Some states, including Florida, have provisions that let courts modify the agreements if they are overly broad.

Analysts say many low-paid workers don’t challenge the agreements because they don’t know they can or fear the costs and process of litigation. That “chilling effect” can prevent workers from moving to a higher-paying position, even if the clause is unenforceable in their state.

“Most of these employers that utilize restrictive covenants never see the light of day in courtrooms,” said Christopher R. O’Hara, an attorney at Todd & Weld LLP.

Some people are fighting back. Mr. O’Hara last year represented Sonia Mercado, a janitor earning $18 an hour, when she was sued by her former employer after going to work for a competitor. Real-estate-services firm Cushman & Wakefield argued she had access to confidential information.

After media reports on the lawsuit, filed in Massachusetts, the company dropped the suit and agreed to pay a portion of the janitor’s legal bill.

A spokesman for C&W Services, the subsidiary involved in the lawsuit, said that while the company has restrictions with some salaried managers, its policy was incorrectly applied in Ms. Mercado’s case.

“We took action to correct the situation, ended all legal proceedings, and sincerely apologized to Ms. Mercado,” spokesman Brad Kreiger said in a statement.

Ms. Mercado, who worked nights overseeing a team of janitors, said she remains “disgusted” by the suit. “I would understand if I was the CEO or vice president or something like that, but come on,” said Ms. Mercado, who lives in Seabrook, N.H.

Some economists argue that noncompetes are evidence of the market power of corporations that can dictate the terms of engagement with their employees. A low unemployment rate might help shift that balance of power back toward workers.

Internal-medicine physician Elizabeth Gilless faced a quandary a few years ago when she was offered a job at a hospital in Memphis, Tenn. A noncompete in the contract said she couldn’t treat patients either within 20 miles of the hospital or in Shelby County—which encompasses Memphis and its environs—for a year after leaving the position. “It would really limit my options in terms of employment after that job,” she said.

Her solution: She took a job with another hospital, one that didn’t require her to sign a noncompete. “This noncompete clause has gotten into physicians’ contracts and is now in so many of them and in situations where it made no sense,” she said.

Updated: 7-21-2020

The Noncompete Clause Gets A Closer Look

Biden’s executive order asks FTC to limit the use of agreements that keep workers from changing jobs; ‘I didn’t know any trade secrets,’ former security guard says.

The noncompete clause is under review.

This month, as part of a broad executive order aimed at bolstering competition in business and the labor market, President Biden called on the Federal Trade Commission to ban or limit clauses in employment contracts that restrict workers’ freedom to change jobs.

Firms impose noncompete clauses on employees to prevent them from sharing trade secrets or proprietary information with new employers. Over time, they have been applied to swaths of the U.S. workforce, ensnaring janitors, baristas, schoolteachers and entry-level workers along with more senior employees like software engineers, sales representatives and top executives.

Around 32% of U.S. companies include the clauses in all of their employment contracts regardless of position or pay, according to a survey conducted by compensation data firm PayScale Inc. in coordination with management professors. Use of noncompete clauses surged partly because templates can be found easily online and pasted into contracts, said Evan Starr, a professor at the Robert H. Smith School of Business at the University of Maryland and one of the authors of the survey.

The proliferation has drawn increased attention from regulators, lawyers and researchers. Though the clauses have until now been regulated at the state level, attorneys and scholars who study competition policy expect the FTC to propose a federal rule that would outlaw noncompetes for workers below a certain income level and may impose limits on the duration or scope of the clauses. An outright ban is unlikely, experts say.

An FTC spokeswoman said the agency has no guidance to share on its timeline or process.

Companies or trade groups may challenge any new rule. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce says courts have provided an adequate avenue for determining when noncompete clauses are abusive, and warned that the FTC would try to overreach with a one-size-fits-all approach.

In early 2017, Michael Kenny found work as a nighttime security guard at Critical Intervention Services Inc., a Florida housing development. A few weeks after accepting the job, which paid around $11 an hour, his overnight child care fell through. Mr. Kenny, a single father, resigned.

Months later, he took a job as a daytime security guard at a bank making almost $15 per hour. He said that soon after he started, his boss informed him that his previous employer had sent a letter stating Mr. Kenny had signed a two-year noncompete clause as part of his employment contract. His new employer let him go.

“I do not remember signing the paper,” Mr. Kenny said. “I didn’t read through a lot of the stuff because I needed a job, and I was so excited that I was actually getting a job.”

Mr. Kenny said he was unable to take other security positions because of the noncompete. He lost his car and eventually filed for bankruptcy. He applied for disability benefits as his diabetes and other medical conditions worsened, and hasn’t worked since.

“They’ve pretty much destroyed me,” he said of CIS. “I’m just trying to put food on the table for my kids. Trying to steal trade secrets? For the amount of time I worked there, I didn’t know any trade secrets.”

Stanford Solomon, a lawyer for CIS, said Mr. Kenny was exposed to proprietary materials during several weeks of training for the CIS job, including training methods and customer information. He said CIS’s noncompete was properly executed and has been previously upheld by courts.

Companies defend the use of noncompetes, saying they are necessary to protect confidential information like customer data and technical formulas.

Opponents of the clauses say noncompetes scare workers into staying where they are or dropping out of careers rather than investing in their skills, starting their own companies or finding better job matches and higher wages. Few workers, they say, have the information or resources to challenge them in court.

Jonathan Pollard, a Florida lawyer who represents Mr. Kenny and is an opponent of noncompete agreements in employment contracts, said his small firm gets about 70 inquiries a week from workers with noncompete clauses, but can only take on a small portion of the cases.

Most states limit noncompete clauses in some way or require that the agreements contain reasonable restrictions, which leaves them open to courts’ interpretations. A handful of states, including California, hold that the clauses are unenforceable in employment contracts.

Even in states where the clauses would be voided by courts, companies still add them because they expect few employees to challenge, Mr. Starr said. He added that he has seen a noncompete clause for a volunteer role at a nonprofit organization in California. “If you ban noncompetes for some or all workers, there needs to be some way to incentivize firms to comply,” he said.

Recent evidence comparing states or industries that tend to enforce noncompete clauses with those that don’t shows that the clauses suppress both innovation and wages, said Orly Lobel, a law professor at the University of San Diego and author of the book “Talent Wants to Be Free.” For example, a study found that Hawaii’s 2015 ban on noncompete agreements for high-tech workers led to an 11% increase in job moves and a 4% increase in new-hire salaries.

“In regions that enforce noncompetes, not only are wages lower, but entrepreneurship is also lower,” Ms. Lobel said. “There’s a disproportionate harm to startups because even when an employee does move when she signs a noncompete, she’s more likely to move to an incumbent competitor that can indemnify her.”

Mr. Starr sees places for compromise. “The uncontroversial parts are that low-wage workers should by and large not be bound by noncompete agreements, and that you shouldn’t be able to surprise a worker with a noncompete on day one of a new job,” he said.

The FTC could also look at limiting the duration of noncompete clauses, many of which require former employees to sit out of the labor market in their field for two years or more, or at limiting their geographic scope, he and other experts said.

A federal rule would resolve one of the current challenges governing noncompetes, which is that every state operates with a different law or legal precedents, said Carolyn Luedtke, a San Francisco-based partner with corporate law firm Munger, Tolles and Olson LLP. That patchwork makes it hard to determine which state’s rules apply when an employee goes to work for a company in another state, she said.

The increase in remote work complicates the question even further. “Setting a federal benchmark can go a long way toward mitigating some uncertainty for firms and workers,” Mr. Starr said.

Updated: Updated: 8-29-2021

Taking A Hammer To Noncompete Agreements Might Hurt Workers

Biden and several states want to rein in restrictive clauses for low-wage employees. They should proceed carefully to protect against unintended consequences.

This month, Illinois became the latest state to place severe limits on the enforceability of noncompete agreements. The new rules include a ban on the clauses for nearly all employees earning less than $75,000.

Other states are considering their own restrictions. President Joe Biden has asked the Federal Trade Commission to consider regulating or banning the agreements.

There are lots of reasons to be skeptical about what many courts still call “covenants not to compete,” nowadays often known as NCAs. To begin with, they restrict the fundamental right of all individuals to sell their labor to the highest bidder. Some theorists — the matter is contested — argue that they limit innovation.

Three states, including California, ban them entirely; several others are considering whether to follow suit. For opponents, the fact that the clauses show up so often in the contracts of low-wage workers is a particular concern. (Just the other day, NPR ran a story about the difficulties they pose for yoga instructors.)

But before we jump on the bandwagon, let’s consider the matter a bit more closely. In particular, let’s try to figure out whether there are any circumstances in which covenants not to compete might be valuable to low-wage employees.

Noncompete clauses have become ubiquitous. A February 2021 study in the Journal of Law and Economics found that 18% of U.S. employees are bound by noncompete agreements. One-third did not learn of the requirement until after they’d accepted the job.

It’s odious to add significant contract provisions during onboarding. The bargaining power of brand-new employees is relatively low because they have turned down other offers. (This concern applies well beyond noncompetes.)

The more important finding — consistent with other research — is that noncompetes are common across industries, and without regard to income and education. Some 13% of workers earning less than $40,000 a year and 14% of workers without a bachelor’s degree were bound by the agreements.

Most observers find it easy to understand why high-wage workers would be asked to sign noncompetes. That’s why many proposed laws — including the one just enacted in Illinois — extend protections mainly to those at the lower end of the wage scale. The underlying intuition is straightforward: In the absence of the restrictions imposed by a noncompete clause, the employer will be forced to pay a higher wage to induce the employee to stay.

But is the intuition correct? If a worker can leave at any time and sell her expertise on the market, the employer might be inclined to invest less in training. The result could easily be a less productive worker who earns a lower wage. Or if the employer does fully train the worker, a lower wage might compensate the company for the risk that the worker will take all that training across the street.

Still, this explanation doesn’t suffice to explain why noncompete agreements have become so common. No potential employee begins negotiations hoping to bargain for a noncompete clause. The inability to sell one’s skills for a higher wage is a cost, not a benefit.

In a perfectly competitive labor market, therefore, we would expect compensation for the clause; that is, the employer would purchase the employee’s freedom to leave by paying a higher wage. This expectation explains why, even in the many states where noncompetes are allowed, courts are less likely to enforce them when employers are unable to show that they gave their employees something of value in exchange.

When jobs are few, however, the employer might impose an NCA as a tool for extracting surplus from the employee without offering a higher wage. A 2020 study by the economists Matthew S. Johnson and Michael Lipsitz confirms this instinct. By measuring the increase in noncompetes among low-wage employees during the Great Recession, when jobs were relatively scarce, Johnson and Lipsitz find exactly this result. Thus there’s good reason for the brouhaha.

But the Great Recession turns out not to be the end of the story. As part of the same analysis, Johnson and Lipsitz hypothesize that when the minimum wage rises, employers of low-wage labor will recoup some of their losses by expanding the use of noncompete clauses. They confirm the hypothesis through a study of the beauty salon industry. The clauses are more common in states that mandate higher wages.

The authors also make another useful discovery. The biggest debate in the minimum-wage literature revolves around how an increase affects employment. Johnson and Lipsitz find that the effect varies, depending on the enforceability of covenants not to compete. In states that enforce the clauses, they report, a rising minimum wage has no measurable effect on employment among low-wage workers. In states that don’t enforce the clauses, the effect is negative — that is, low-wage employment falls.

If these findings are correct — always a big “if” for an unexpected effect — employers may be using noncompetes to recover some of the surplus they’ve transferred to employees in the form of the legally mandated higher wage. Prohibiting the clauses for low-wage workers, despite its allure, might drive employers to find other means to recoup their losses; they might even, as the study of the salon industry implies, just employ fewer people.

None of this is to say that minimum wage increases are bad, or that covenants not to compete are good. What the findings do suggest is that banning noncompetes can raise the cost to the employer of low-wage labor.

This suggests in turn, as the authors note, that any regulatory response to the conundrum of post-employment restrictions on labor ought to be nuanced. We don’t do nuance well these days — but, if regulators are cautious, Biden’s executive order might give them the chance to try.

Related Articles:

It’s Never Too Late To Start A Brilliant Career (#GotBitcoin?)

What Teenagers Learn When They Start A Business (#GotBitcoin?)

We Look At Who’s Hiring Vs Who’s Firing (#GotBitcoin?)

Where The Jobs Are (#GotBitcoin?)

New Job For Robots: Taking Stock For Retailers (#GotBitcoin?)

Even A Booming Job Market Can’t Fill Retirement Shortfall For Older Workers (#GotBitcoin?)

Robot Reality Check: They Create Wealth—And Jobs (#GotBitcoin?)

Your Next Job Interview Could Be With A Robot

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.